The military history of Pakistan ( ur, ) encompasses an immense panorama of conflicts and struggles extending for more than 2,000 years across areas constituting modern

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

and greater

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

. The history of the modern-day

military of Pakistan

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

began in

1947, when Pakistan achieved its independence as a modern nation.

The military holds a significant place in the

history of Pakistan, as the Pakistani Armed Forces have played, and continue to play, a significant role in the

Pakistani establishment and shaping of the country. Although Pakistan was founded

as a democracy after its independence from the

British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

, the military has remained one of the country's most powerful institutions and has on occasion

overthrown democratically elected civilian governments on the basis of self-assessed mismanagement and corruption. Successive governments have made sure that the military was consulted before they took key decisions, especially when those decisions related to the

Kashmir conflict

The Kashmir conflict is a territorial conflict over the Kashmir region, primarily between India and Pakistan, with China playing a third-party role. The conflict started after the partition of India in 1947 as both India and Pakistan claimed ...

and

foreign policy. Political leaders of Pakistan are aware that the military has stepped into the political arena through coup d'état to establish military dictatorships, and could do so again.

The Pakistani Armed Forces were created in 1947 by division of the

British Indian Army. Pakistan was given units such as the

Khyber Rifles

The Khyber Rifles are a paramilitary regiment, forming part of the Pakistani Frontier Corps Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (North). The Rifles are tasked with defending the border with Afghanistan and assisting with law enforcement in the districts adjac ...

, which had seen intensive service in

World Wars I and

II. Many of the early leaders of the military had fought in both world wars. Military history and culture is used to inspire and embolden modern-day troops, using historic names for medals, combat divisions, and domestically produced weapons.

Since the time of

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, the military has fought three major wars with

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

It has also fought a limited conflict at

Kargil

Kargil ( lbj, ) is a city and a joint capital of the union territory of Ladakh, India. It is also the headquarters of the Kargil district. It is the second-largest city in Ladakh after Leh. Kargil is located to the east of Srinagar in Jam ...

with India after acquiring nuclear capabilities. In addition, there have been several minor border skirmishes with neighbouring

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

. After the

September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commer ...

, the military is engaged in a protracted low intensity conflict along Pakistan's western border with Afghanistan, with the

Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

and

Al-Qaeda militants, as well as those who support or provide shelter to them.

In addition, Pakistani troops have also participated in various foreign conflicts, usually acting as

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

peacekeepers. At present, Pakistan has the largest number of its personnel acting under the United Nations with the number standing at 10,173 as of 31 March 2007.

550 BCE–1857

Ancient empires

The region of modern-day Pakistan (part of British

Raj before 1947) formed the most-populous, easternmost and richest

satrapy

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

of the Persian

Achaemenid Empire for almost two centuries, starting from the reign of

Darius the Great (522–485 BC).

The first major conflict erupted when

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

overthrew the Achaemenid Empire in 334 BCE and marched eastwards. After defeating

King Porus

Porus or Poros ( grc, Πῶρος ; 326–321 BC) was an ancient Indian king whose territory spanned the region between the Jhelum River (Hydaspes) and Chenab River (Acesines), in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. He is only men ...

in the fierce

Battle of the Hydaspes

The Battle of the Hydaspes was fought between Alexander the Great and king Porus in 326 BC. It took place on the banks of the Jhelum River (known to the ancient Greeks as Hydaspes) in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent (modern-day ...

(near modern

Jhelum), he conquered much of the

Punjab region

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

. But his battle weary troops refused to advance further into India

to engage the formidable army of the

Nanda Dynasty

The Nanda dynasty ruled in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent during the fourth century BCE, and possibly during the fifth century BCE. The Nandas overthrew the Shaishunaga dynasty in the Magadha region of eastern India, and expanded ...

and its vanguard of elephants, new monstrosities to the invaders. Therefore, Alexander proceeded southwest along the Indus valley.

Along the way, he engaged in several battles with smaller kingdoms before marching his army westward across the Makran desert towards modern Iran. Alexander founded several new Macedonian/Greek settlements in

Gandhara and

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

.

As

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

's Greek and Persian armies withdrew westwards, the

satraps left behind by Alexander were defeated and conquered by

Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the

Maurya Empire, which ruled the region from 321 to 185 BC. The Mauryas Empire was itself conquered by the

Shunga Empire, which ruled the region from 185 to 73 BC. Other regions such as the

Khyber Pass were left unguarded, and a wave of foreign invasion followed. The

Greco-Bactrian

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the India ...

king,

Demetrius

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Dumi ...

, capitalised and conquered southern Afghanistan and Pakistan around 180 BC, forming the

Indo-Greek Kingdom

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent (p ...

. The Indo-Greek Kingdom ultimately disappeared as a political entity around 10 AD following the invasions of the Central Asian

Indo-Scythian

Indo-Scythians (also called Indo-Sakas) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples of Scythian origin who migrated from Central Asia southward into modern day Pakistan and Northwestern India from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th centur ...

s. Their empire morphed into the

Kushan Empire who ruled until 375 AD. The region was then conquered by the Persian

Indo-Sassanid

Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom (also called Kushanshahs, KΟÞANΟ ÞAΟ ''or Koshano Shao'' in Bactrian, or Indo-Sasanians) is a historiographic term used by modern scholars to refer to a branch of the Sasanian Persians who established their rule in ...

Empire which ruled large parts of it until 565 AD.

Muslim conquests

In 712 CE, a Syrian Muslim chieftain called

Muhammad bin Qasim conquered most of the

Indus region (stretching from

Sindh to

Multan

Multan (; ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan, on the bank of the Chenab River. Multan is Pakistan's seventh largest city as per the 2017 census, and the major cultural, religious and economic centre of southern Punjab.

Multan is one of the old ...

) for the

Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

Empire. In 997 CE,

Mahmud of Ghazni conquered the bulk of

Khorasan, marched on Peshawar in 1005, and followed it by the conquests of Punjab (1007), Balochistan (1011), Kashmir (1015) and Qanoch (1017). By the end of his reign in 1030, Mahmud's empire extended from

Kurdistan

Kurdistan ( ku, کوردستان ,Kurdistan ; lit. "land of the Kurds") or Greater Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural territory in Western Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languages ...

in the west to the

Yamuna

The Yamuna ( Hindustani: ), also spelt Jumna, is the second-largest tributary river of the Ganges by discharge and the longest tributary in India. Originating from the Yamunotri Glacier at a height of about on the southwestern slopes of B ...

river in the east, and the Ghaznavid dynasty lasted until 1187. In 1160, Muhammad Ghori conquered Ghazni from the Ghaznavids and became its governor in 1173. He marched eastwards into the remaining Ghaznavid territory and Gujarat in the 1180s, but was rebuffed by Gujarat's

Solanki Solanki may refer to:

*Solanki (name), surname and given name

*Solanki (clan), Indian clan associated with the Rajputs

*Solanki dynasty, alternate name for the Chaulukya dynasty

The Chaulukya dynasty (), also Solanki dynasty, was a dynasty tha ...

rulers. In 1186–87, he conquered Lahore, bringing the last of Ghaznevid territory under his control and ending the Ghaznavid Empire. Muhammad Ghori returned to Lahore after 1200 to deal with a revolt of the Rajput Ghakkar tribe in the Punjab. He suppressed the revolt, but was killed during a Ghakkar raid on his camp on the Jhelum River in 1206. Muhammad Ghori's successors established the first Indo-Islamic dynasty, the

Delhi Sultanate. The

Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

Dynasty, (''mamluk'' means "

slave" and referred to the Turkic slave soldiers who became rulers throughout the Islamic world), seized the throne of the Sultanate in 1211. Several Turko-Afghan dynasties ruled their empires from Delhi: the Mamluk (1211–1290), the

Khalji

The Khalji or Khilji (Pashto: ; Persian: ) dynasty was a Turco-Afghan dynasty which ruled the Delhi sultanate, covering large parts of the Indian subcontinent for nearly three decades between 1290 and 1320.[Tughlaq

The Tughlaq dynasty ( fa, ), also referred to as Tughluq or Tughluk dynasty, was a Muslim dynasty of Indo- Turkic origin which ruled over the Delhi sultanate in medieval India. Its reign started in 1320 in Delhi when Ghazi Malik assumed the ...]

(1320–1413), the

Sayyid

''Sayyid'' (, ; ar, سيد ; ; meaning 'sir', 'Lord', 'Master'; Arabic plural: ; feminine: ; ) is a surname of people descending from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his grandsons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali, sons of Muhamma ...

(1414–1451) and the

Lodhi (1451–1526). Although some kingdoms remained independent of Delhi – in Gujarat,

Malwa

Malwa is a historical region of west-central India occupying a plateau of volcanic origin. Geologically, the Malwa Plateau generally refers to the volcanic upland north of the Vindhya Range. Politically and administratively, it is also syn ...

(central India), Bengal and

Deccan

The large Deccan Plateau in southern India is located between the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, and is loosely defined as the peninsular region between these ranges that is south of the Narmada river. To the north, it is bounded by the ...

– almost all of the Indus plain came under the rule of these large Indo-Islamic sultanates. Perhaps the greatest contribution of the sultanate was its temporary success in insulating South Asia from the

Mongol invasion from Central Asia in the 13th century; nonetheless the sultans eventually lost

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

and western Pakistan to the

Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

(see the

Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm ...

Dynasty).

Mughal Empire

From the 16th to the 19th century, the formidable

Mughal empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

covered much of India. In 1739, the Persian emperor

Nader Shah invaded India, defeated the Mughal Emperor

Muhammad Shah

Mirza Nasir-ud-Din Muḥammad Shah (born Roshan Akhtar; 7 August 1702 – 26 April 1748) was the 13th Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1719 to 1748. He was son of Khujista Akhtar, the fourth son of Bahadur Shah I. After being chosen by the ...

, and occupied most of Balochistan and the Indus plain. After Nadir Shah's death, the kingdom of Afghanistan was established in 1747 by one of his generals,

Ahmad Shah Abdali

Ahmad Shāh Durrānī ( ps, احمد شاه دراني; prs, احمد شاه درانی), also known as Ahmad Shāh Abdālī (), was the founder of the Durrani Empire and is regarded as the founder of the modern Afghanistan. In July 1747, Ahm ...

, and included Kashmir, Peshawar, Daman, Multan, Sindh and Punjab. In the south, a succession of autonomous dynasties (the

Daudpotas,

Kalhoras and

Talpurs) had asserted the independence of Sind, from the end of Aurangzeb's reign. Most of Balochistan came under the influence of the Khan of

Kalat, apart from some coastal areas such as

Gwadar

Gwadar ( Balochi/ ur, ) is a port city with located on the southwestern coast of Balochistan, Pakistan. The city is located on the shores of the Arabian Sea opposite Oman. Gwadar is the 100th largest city of Pakistan, according to the 2017 ...

, which were ruled by the Sultan of

Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

. The

Sikh Confederacy

The Misls (derived from an Arabic word مِثْل meaning 'equal') were the twelve sovereign states of the Sikh Confederacy, which rose during the 18th century in the Punjab region in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent and is cit ...

(1748–1799) was a group of small states in the Punjab that emerged in a political vacuum created by rivalry between the Mughals, Afghans and Persians.

The Confederacy drove out the Mughals, repelled several Afghan invasions and in 1764 captured Lahore. However, after the retreat of Ahmed Shah Abdali, the Confederacy suffered instability as disputes and rivalries emerged.

The Sikh empire (1799–1849) was formed on the foundations of the Confederacy by

Ranjit Singh who proclaimed himself "''Sarkar-i-Wala''", and was referred to as the Maharaja of Lahore.

His empire eventually extended as far west as the

Khyber Pass and as far south as Multan. Amongst his conquests were Kashmir in 1819 and Peshawar in 1834, although the Afghans made two attempts to recover Peshawar. After the Maharaja's death the empire was weakened by internal divisions and political mismanagement. The British annexed the Sikh Empire in 1849 after the

Second Anglo-Sikh War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War was a military conflict between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company that took place in 1848 and 1849. It resulted in the fall of the Sikh Empire, and the annexation of the Punjab and what subsequently ...

.

1857–1947

British Raj

The

British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

ruled from 1858 to 1947, the period when India was part of the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Following the famous

Sepoy Mutiny

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

, the British took steps to avoid further rebellions taking place including changing the structure of the Army. They banned Indians from the officer corp and artillery corp to ensure that future rebellions would not be as organised and disciplined and that the ratio of British soldiers to Indians would be drastically increased. Recruiting percentages changed with an emphasis on Sikhs and Gurkhas whose loyalties and fighting prowess had been proven in the conflict and new caste- and religious-based regiments were formed.

The World Wars

During World War I the British Indian Army fought in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

,

Palestine,

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

,

Gallipoli, and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and suffered very heavy casualties.

The British Indian Army's strength was about 189,000 in 1939. There were about 3,000 British officers and 1,115 Indian officers. The army was expanded greatly to fight in World War II. By 1945, the strength of the Army had risen to about two-and-a-half million. There were about 34,500 British officers and 15,740 Indian officers. The Army took part in campaigns in

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

,

East Africa,

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

,

Syria,

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

,

Malaya,

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

,

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

,

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. It suffered 179,935 casualties in the war (including 24,338 killed, 64,354 wounded, 11,762 missing and 79,481 soldiers). Many future military officers and leaders of Pakistan fought in these wars.

Birth of the modern military

On June 3, 1947, the British Government announced its plan to divide

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

between

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

and the subsequent transfer of power to the two countries resulted in

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

of

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

. The division of the British Indian Army occurred on June 30, 1947, in which Pakistan received six armoured, eight

artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

and eight

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

regiments compared to the forty armoured, forty artillery and twenty-one infantry regiments that went to India.

At the Division Council, which was chaired by

Rear Admiral Lord Mountbatten of Burma

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of Germa ...

, the

Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, and was composed of the leaders of the

Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

and the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

, they had agreed that the British Indian Army of 11,800 officers and 500,000 enlisted personnel was to be divided to the ratio of 64% for India and 36% for Pakistan.

Pakistan was forced to accept a smaller share of the armed forces as most of the military assets, such as weapons depots, military bases, etc., were located inside the new

Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

, while those that were in the new

Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of ...

were mostly obsolete. Pakistan also had a dangerously low ammunition reserve of only one week.

By August 15, 1947, both India and Pakistan had operational control over their armed forces.

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir Frank Messervy was appointed as the first

Army Commander-in-Chief of the new

Pakistan Army. General Messervy was succeeded in this post in February 1948, by

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir Douglas Gracey, who served until January 1951.

The Pakistani Armed Forces initially numbered around 150,000 men, many scattered around various bases in India and needing to be transferred to Pakistan by train. The independence created large-scale communal violence in India. In total, around 7 million Muslims migrated to Pakistan and 5 million Sikhs and Hindus to India with over a million people dying in the process.

Of the estimated requirement of 4,000 officers for

Pakistani Armed Forces

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

, only 2,300 were actually available. The neutral British officers were asked to fill in the gap and nearly 500 volunteered along with many Polish and Hungarian officers to run the medical corps.

[Nigel Kelly, ''The History and Culture of Pakistan'', pg. 98, ]

By October 1947, Pakistan had raised four divisions in

West Pakistan

West Pakistan ( ur, , translit=Mag̱ẖribī Pākistān, ; bn, পশ্চিম পাকিস্তান, translit=Pôścim Pakistan) was one of the two Provincial exclaves created during the One Unit Scheme in 1955 in Pakistan. It was ...

and one division in

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wi ...

with an overall strength of ten infantry brigades and one armoured brigade with thirteen tanks. Many brigades and battalions within these divisions were below half strength, but Pakistani personnel continued to arrive from all over India, the Middle East and North Africa and from South East Asia. Mountbatten and

Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Army commander during the Second World War. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, where he rose to become Commander ...

, the last

Commander-in-Chief, India, had made it clear to Pakistan that in case of war with India, no other member of the

Commonwealth would come to Pakistan's aid.

1947–1965

The war of 1947

Pakistan experienced combat almost immediately in the

First Kashmir War

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

when it sent its forces into Kashmir. Kashmir had a Muslim majority population, but the choice of which country to join was given to Maharaja Hari Singh who was unable to decide whether to join India or Pakistan. By late October, the overthrow of the maharaja seemed imminent. He sought military assistance from India, for which he signed an instrument of accession with India.

The Pakistan army was pushed back by the Indians but not before taking control of the northwestern part of

Kashmir (roughly 40% of Kashmir), which Pakistan still controls, the rest remaining under Indian control except for the portion ceded by Pakistan to China.

US aid

With the failure of the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

to persuade India to join an anti-communist pact, it turned towards Pakistan, which in contrast with India was prepared to join such an alliance in return of military and economic aid and also to find a potential ally against

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. By 1954, the US had decided that

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

along with

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

and Iran would be ideal countries to counter

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

influence. Therefore, Pakistan and the US signed the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement and American aid began to flow into Pakistan. This was followed by two more agreements. In 1955, Pakistan joined the South East Asian Treaty Organization (

SEATO

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

) and the

Baghdad Pact

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Tur ...

, later renamed the Central Asian Treaty Organization (

CENTO

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Tur ...

) when Iraq withdrew in 1959.

[Nigel Kelly, ''The History and culture of Pakistan'', pg. 143–144, ]

Pakistan received over a billion dollars in US military aid between 1954 and 1965. This aid greatly enhanced Pakistan's defence capability as new equipment and weapons were brought into the armed forces, new military bases were created, existing ones were expanded and upgraded, and two new Corps commands were formed. Shahid M Amin, who had served in the Pakistani foreign service, wrote, "It is also a fact, that these pacts did undoubtedly secure very substantial US military and economic assistance for Pakistan in its nascent years and significantly strengthened it in facing India, as seen in the 1965 war."

[Shahid M. Amin, ''Pakistan's Foreign Policy: A Reappraisal'', pg. 44, ]

American and British advisers trained Pakistani personnel and the US was allowed to create bases within Pakistan's borders to spy on the Soviet Union. In this period, many future Pakistani presidents and generals went to American and British military academies, which led to the Pakistan army developing along Western models, especially following the British.

After Dominion status ended in 1956 with the formation of a Constitution and a declaration of Pakistan as an Islamic Republic, the military took control in 1958 and held power for more than 10 years. During this time, Pakistan had developed close military relations with many Middle Eastern countries to which Pakistan sent military advisers, a practice which continues into the 21st century.

First military rule

In 1958, retired

Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

and President

Iskander Mirza

Sahibzada Iskander Ali Mirza ( bn, ইস্কান্দার আলী মির্জা; ur, ; 13 November 1899 – 13 November 1969), , was a Pakistani Bengali general officer and civil servant who was the first President of Pakista ...

took over the country, deposed the government of Prime Minister

Feroz Khan Noon

Sir Malik Feroz Khan Noon, ( ur, ملک فیروز خان نون; 7 May 18939 December 1970), best known as Feroze Khan, was a Pakistani politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Pakistan from 1957 until being removed wh ...

, and declared martial law on October 7, 1958. President Mirza personally appointed his close associate General

Ayub Khan as the Commander-in-Chief of Pakistan's army. However, Khan ousted Mirza when he became highly dissatisfied by Mirza's policies. As president and commander-in-chief, Ayub Khan appointed himself a 5-star Field Marshal and built relationships with the United States and the West. A formal alliance including

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

,

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, and

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

was formed and was called the

Baghdad Pact

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Tur ...

(later known as CENTO), which was to defend the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

and

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

from Soviet communists designs.

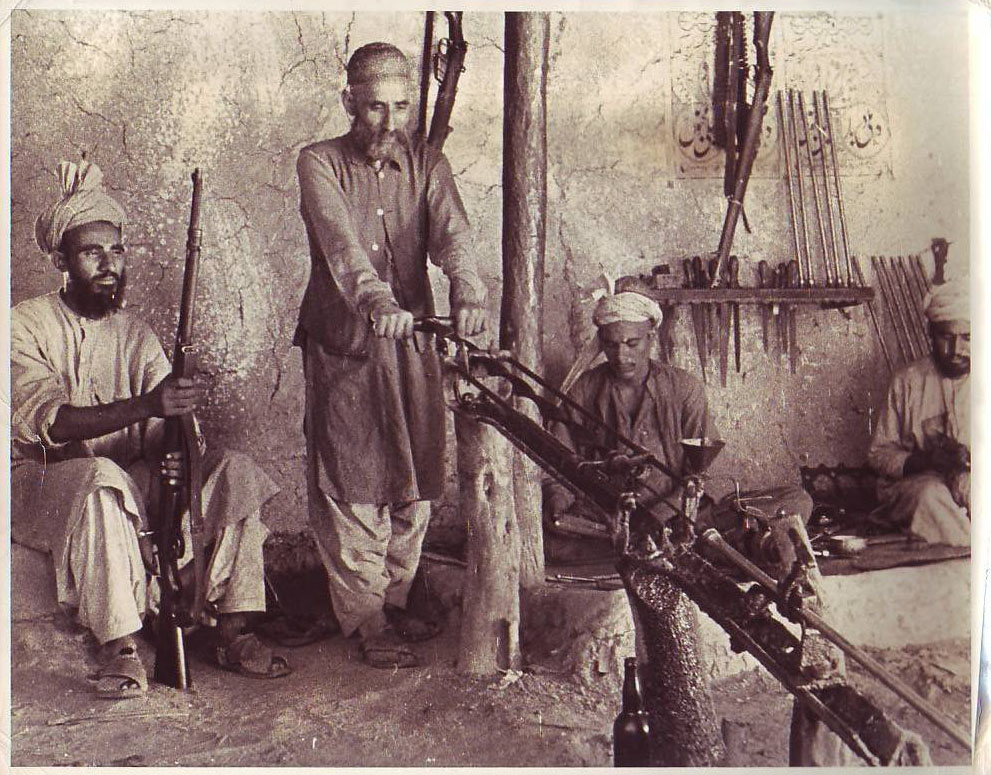

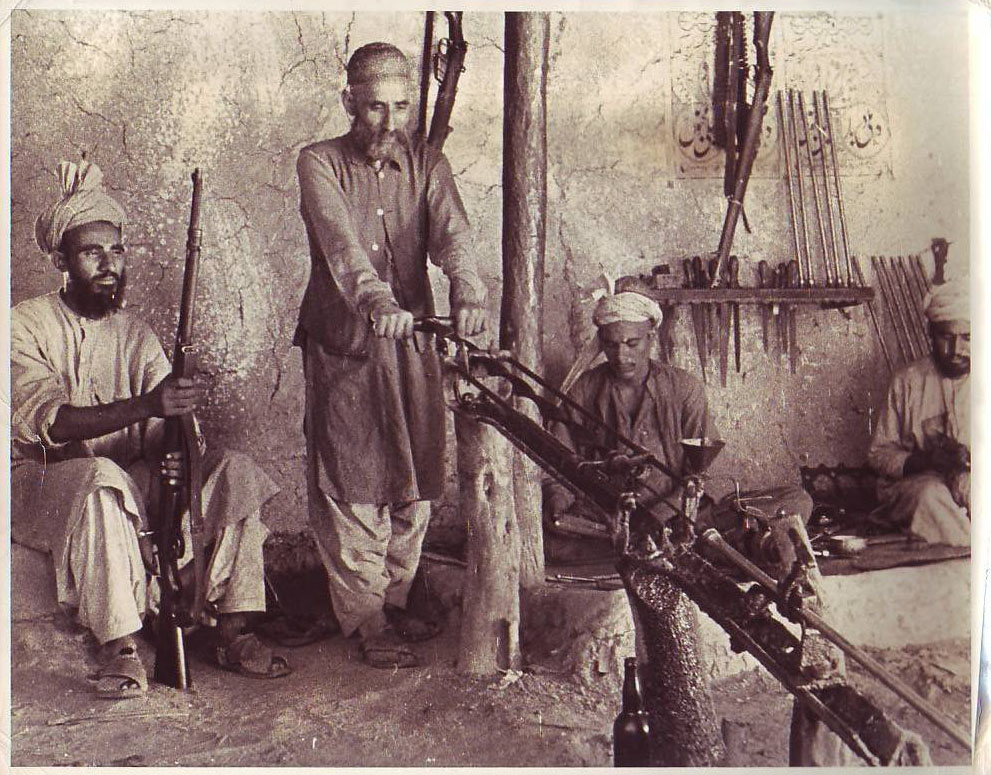

Border clashes with Afghanistan

Armed tribal incursions from

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

into Pakistan's border areas began with the transfer of power in 1947 and became a continual irritant. Many Pashtun Afghans regarded the 19th century Anglo-Afghan border treaties (historically called the

Durand Line

The Durand Line ( ps, د ډیورنډ کرښه; ur, ), forms the Pakistan–Afghanistan border, a international land border between Pakistan and Afghanistan in South Asia. The western end runs to the border with Iran and the eastern end to th ...

) as void and were trying to re-draw the borders with Pakistan or to create an independent state (

Pashtunistan

Pashtunistan ( ps, پښتونستان, lit=land of the Pashtuns) is a historical region in Central Asia and South Asia, inhabited by the indigenous Pashtun people of Afghanistan and western Pakistan. Wherein Pashtun culture, the Pashto language, ...

) for the ethnic

Pashtun people

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically r ...

. The Pakistan Army had to be continually sent to secure the country's western borders. Afghan–Pakistan relations were to reach their lowest points in 1955 when diplomatic relations were severed with the ransacking of Pakistan's embassy in

Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

and again in 1961 when the Pakistan Army had to repel a major Afghan incursion in Bajaur region.

Pakistan used American weaponry to fight the Afghan incursions but the weaponry had been sold under the pretext of fighting

Communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and the US was not pleased with this development, as the Soviets at that time became the chief benefactor to Afghanistan. Some sections of the American press blamed Pakistan for driving Afghanistan into the Soviet camp.

Alliance with China

After India's defeat in the

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibet ...

of 1962,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

began a rapid program of reforming and expanding its military. A series of conferences on Kashmir was held from December 1962 to February 1963 between India and Pakistan. Both nations offered important concessions and a solution to the long-standing dispute seemed imminent. However, after the Sino-Indian war, Pakistan had gained an important new ally in China and Pakistan then signed a bilateral border agreement with China that involved the boundaries of the disputed state, and relations with India again became strained.

Fearing a communist expansion into India, the US for the first time gave large quantities of weapons to India. The expansion of the Indian armed forces was viewed by most Pakistanis as being directed towards Pakistan rather than

China. The US also pumped in large sums of money and military supplies to Pakistan as it saw Pakistan as being a check against Soviet expansionist plans.

1965–1979

The War of 1965

Pakistan viewed the

military of India

The Indian Armed Forces are the military forces of the Republic of India. It consists of three professional uniformed services: the Indian Army, Indian Navy, and Indian Air Force.—— Additionally, the Indian Armed Forces are supported by th ...

as being weakened following the

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibet ...

in 1962. A small border skirmish between India and Pakistan in the

Rann of Kutch

The Rann of Kutch (alternately spelled as Kuchchh) is a large area of salt marshes that span the border between India and Pakistan. It is located in Gujarat (primarily the Kutch district), India, and in Sindh, Pakistan. It is divided into ...

in April 1965 caught the

Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

unprepared. The skirmish occurred between the border police of both countries due to poorly defined borders and later the armies of both countries responded. The result was decisive for the Pakistan army which was commended at home. Emboldened by this success,

Operation Gibraltar

Operation Gibraltar was the codename of a military operation planned and executed by the Pakistan Army in the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir in August 1965. The operation's strategy was to covertly cross the Line of Control (LoC) an ...

, an infiltration attempt in

Kashmir, was launched later that year. Rebellion was fostered among local Kashmiris to attack the Indian Army. Pakistan Army had a qualitative superiority over their neighbours. This caused a full-fledged war across the international border (the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965) broke out between India and Pakistan. The air forces of both countries engaged in

massive air warfare. While on the offensive both armies occupied some of the other country's territory, resulting in a stalemate, but both sides claim victory.

The US had imposed an arms embargo on both India and Pakistan during the war and Pakistan was affected more as it lacked spare parts for its

Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

,

tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engi ...

s, and other equipment, while India's quantitative edge making up for theirs. The war ended in a ceasefire.

Rebuilding the Armed Forces

The US was disillusioned by a war in which both countries fought each other with equipment which had been sold for defensive purposes and to stop the spread of communism. Pakistan claimed that it was compelled to act by the Indian attempt to fully integrate Indian-controlled Kashmir into the union of India, but this had little impact to the

Johnson Administration and by July 1967, the US withdrew its military assistance advisory group. In response to these events, Pakistan declined to renew the lease on the

Peshawar

Peshawar (; ps, پېښور ; hnd, ; ; ur, ) is the sixth most populous city in Pakistan, with a population of over 2.3 million. It is situated in the north-west of the country, close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is ...

military facility, which ended in 1969. Eventually, US–Pakistan relations grew measurably weaker as the US became more deeply involved in

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

and as its broader interest in the security of South Asia waned.

The

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

continued the massive build-up of the Indian military and a US arms embargo forced Pakistan to look at other options. It turned to

China,

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

for military aid. China in particular gave Pakistan over 900 tanks,

Mig-19

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-19 (russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-19; NATO reporting name: Farmer) is a Soviet second generation, single-seat, twinjet fighter aircraft, the world's first mass-produced supersonic aircraft. It was the ...

fighters and enough equipment for three infantry divisions. France supplied some Mirage aircraft, submarines. The Soviet Union gave Pakistan around 100

T-55

The T-54 and T-55 tanks are a series of Soviet main battle tanks introduced in the years following the Second World War. The first T-54 prototype was completed at Nizhny Tagil by the end of 1945.Steven Zaloga, T-54 and T-55 Main Battle Tank ...

tanks and

Mi-8

The Mil Mi-8 (russian: Ми-8, NATO reporting name: Hip) is a medium twin-turbine helicopter, originally designed by the Soviet Union in the 1960s and introduced into the Soviet Air Force in 1968.

It is now produced by Russia.

In addition t ...

helicopters but that aid was abruptly stopped under intense Indian pressure. Pakistan in this period was partially able to enhance its military capability.

Involvement in Arab conflicts

Pakistan had sent numerous military advisers to

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and

Syria to help in their training and military preparations for any potential war with

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. When the Six-Day War started, Pakistan assisted by sending a contingent of its pilots and

airmen to

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, Jordan and Syria. PAF pilots downed about 10 Israeli planes including Mirages, Mysteres and Vautours without losing a single plane of their own.

Jordan and Iraq decorated East Pakistani Flight Lieutenant Saif-ul-Azam. Israelis also praised the performance of PAF pilots. Eizer Weizman, then Chief Of Israeli Air Force wrote in his autobiography about Air Marshal Noor Khan (Commander PAF at that time): "...He is a formidable person and I am glad that he is Pakistani and not Egyptian." No Pakistani ground forces participated in the war.

After the end of the Six-Day War, Pakistani advisors remained to train the Jordanian forces. In 1970, King Hussein of Jordan decided to remove the PLO from Jordan by force after a series of terrorist acts attributed to the PLO, which undermined Jordanian sovereignty. On September 16, King Hussein declared martial law. The next day, Jordanian tanks attacked the headquarters of Palestinian organisations in Amman. The head of Pakistan's training mission to Jordan, Brigadier-General

Zia-ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, ( Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial ...

(later

President of Pakistan), took command of the Jordanian Army's 2nd division and helped Jordan during this crisis.

Pakistan again assisted during the Yom Kippur War, sixteen PAF pilots volunteered for service in the Air Forces of Egypt and Syria. The PAF contingent deployed to Inchas Air Base (Egypt) led by Wing Commander Masood Hatif and five other pilots plus two air defence controllers. During this war, the Syrian government decorated Flight Lieutenant Sattar Alvi when he shot down an Israeli Mirage over the Golan Heights.

The PAF pilots then became instructors in the Syrian Air Force at Dumayr Air Base and after the war Pakistan continued to send military advisers to Syria and Jordan. Apart from military advisers, no Pakistani ground forces participated in this war.

In 1969, South Yemen, which was under a communist regime and a strong ally of the USSR, attacked and captured Mount Vadiya inside the province of Sharoora in Saudi Arabia. Many PAF officers as well Army personnel who were serving in Khamis Mushayt training the Saudi Air Force (the closest airbase to the battlefield), took active part in this battle in which the enemy was ultimately driven back.

[

]

The War of 1971

The

first democratic elections in Pakistan were held in 1970 with the

Awami League (AL) winning a substantial majority in

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wi ...

while the

Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) won a majority in

West Pakistan

West Pakistan ( ur, , translit=Mag̱ẖribī Pākistān, ; bn, পশ্চিম পাকিস্তান, translit=Pôścim Pakistan) was one of the two Provincial exclaves created during the One Unit Scheme in 1955 in Pakistan. It was ...

. However talks on sharing power failed

and President

Yahya Khan

General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan , (Urdu: ; 4 February 1917 – 10 August 1980); commonly known as Yahya Khan, was a Pakistani military general who served as the third President of Pakistan and Chief Martial Law Administrator following his p ...

declared martial law.

PPP leader

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar (or Zulfiqar) Ali Bhutto ( ur, , sd, ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو; 5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979), also known as Quaid-e-Awam ("the People's Leader"), was a Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the fourt ...

had refused to accept an AL government and declared he would "break the legs" of any of his party members who attended the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

. Capitalizing on West Pakistani fears of East Pakistani separatism, Bhutto demanded to form a coalition with AL leader

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman ( bn, শেখ মুজিবুর রহমান; 17 March 1920 – 15 August 1975), often shortened as Sheikh Mujib or Mujib and widely known as Bangabandhu (meaning ''Friend of Bengal''), was a Bengali politi ...

. They agreed upon a coalition government, with Bhutto as president and Mujibur as prime minister, and put political pressure on Khan's military government. Pressured by the military, Khan postponed the inaugural session, and ordered the arrests of Mujibur and Bhutto.

Faced with popular unrest and revolt in

East-Pakistan, the army and navy attempted to impose order. Khan's military government ordered

Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Mohammad Shariff

Admiral Mohammad Shariff ( ur, ; 1 July 1920 – 27 April 2020), was a Pakistan Navy senior admiral, who served as the 2nd Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee and a memoirist who was at the center of all the major decisions made ...

, Commander of Eastern Naval Command of the Pakistan Navy, and

Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi

Lieutenant General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi (1915 – 1 February 2004) was a Pakistan Army general. During the Bangladesh Liberation War and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, he commanded the Pakistani Eastern Command in East Pakistan (now Bang ...

, Commander of the

Eastern Military Command of Pakistan Army, to curb and liberate East Pakistan from the resistance. The navy and army crackdown and brutalities during

Operation Searchlight

Operation Searchlight was the codename for a planned military operation carried out by the Pakistan Army in an effort to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in former East Pakistan in March 1971. Pakistan retrospectively justified the opera ...

and

Operation Barisal

Operation Barisal was a code-name of naval operation conducted by Pakistan Navy intended to take control of the city of Barisal, East Pakistan from the Mukti Bahini and the dissidents of the Pakistan Defence Forces. It was the part of Operation ...

and the

continued killings throughout the later months resulted in further resentment among the

East Pakistanis. With India assisting and funding the

Mukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini ( bn, মুক্তিবাহিনী, translates as 'freedom fighters', or liberation army), also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was the guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military, paramilitary ...

, war broke out between the separatist supporters in Bangladesh and Pakistan (

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a military confrontation between India and Pakistan that occurred during the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan from 3 December 1971 until the

Pakistani capitulation in Dhaka on 16 Decem ...

). During the conflict, the co-ordination between the armed forces of Pakistan were ineffective and unsupported. The army, navy, marines and air force were not consulted in major decisions, and each force led their own independent operations without notifying the higher command. To release the pressure from East Pakistan the Pakistan Army opened new front on the western sector when a 2,000-strong Pakistani force attacked the Indian outpost at Longewala held by 120 Indian soldiers of 23 Punjab regiment. The attack was backed by a tank regiment but without air support. The battle was decisively won by the Indian army with the help of the Indian Air Force, and was an example of poor co-ordination by Pakistan.

The result was the

Pakistan Armed Forces

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

's

surrender

Surrender may refer to:

* Surrender (law), the early relinquishment of a tenancy

* Surrender (military), the relinquishment of territory, combatants, facilities, or armaments to another power

Film and television

* ''Surrender'' (1927 film), an ...

to the allied forces upon which 93,000 soldiers, officers and civilians became

POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

. The official war between India and Pakistan ended after a fortnight on December 16, 1971, with Pakistan losing

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wi ...

, which became

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

.

Recovery from the 1971 War

The military government collapsed as a result of the war, and control of the country was handed over to the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Bhutto became the country's first

Chief Martial Law Administrator

The office of the Chief Martial Law Administrator was a senior and authoritative post with Zonal Martial Law Administrators as deputies created in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia that gave considerable executive authority and p ...

and first Commander-in-Chief of Pakistan Armed Forces. Taking authority in January 1972, Bhutto started a nuclear deterrence programme under Munir Ahmad Khan and his adviser Abdus Salam. In July 1972, Bhutto reached the ''

Shimla Agreement'' with Indira Gandhi of India, and brought back 93,000 POWs and recognised East-Pakistan as Bangladesh.

As part of re-organizing the country, Bhutto disbanded the "Commander-in-Chief" title in the Pakistan Armed Forces. He also decommissioned the

Pakistan Marines

ur, اور اللہ کی رسی مضبوط تھام لو سب مل کر اور آپس میں پھٹ نہ جانا (فرقوں میں نہ بٹ جانا) "And hold fast to the rope of Allah, all of you together, and do not be divided;" (''Qur'an ...

as a unit of Pakistan Navy. Instead, Chiefs of Staff were appointed in the three branches and Bhutto appointed all 4 star officers as the Chief of Staff in the Pakistan Armed Forces. General

Tikka Khan

General Tikka Khan ( ur, ٹکا خان; 10 February 1915 – 28 March 2002) was a Pakistan Army general who was the first chief of army staff from 3 March 1972 until retiring on 1 March 1976. Along with Yahya Khan, he is considered a chief a ...

, infamous for his role in Bangladesh Liberation War, become the first

Chief of Army Staff; Admiral Mohammad Shariff, as first 4-star admiral in the navy and as the first

Chief of Naval Staff; and,

Air Chief Marshal (General)

Zulfiqar Ali Khan, as first 4-star air force general, and the first

Chief of Air Staff. Because the co-ordination between the armed forces were unsupported and ineffective, in 1976, Bhutto also created the office of

Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (JCSC), ( ur, ); is an administrative body of senior high-ranking uniformed military leaders of the unified Pakistan Armed Forces who advises the civilian Government of Pakistan, National Security Council, ...

for maintaining the co-ordination between the armed forces. General

Muhammad Shariff, a 4-star general, was made the first

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.

Pakistan's defence spending rose by 200% during the

Bhutto's democratic era but the India–Pakistan military balance, which was near parity during the 1960s, was growing decisively in India's favour. Under Bhutto, the

education system

The educational system generally refers to the structure of all institutions and the opportunities for obtaining education within a country. It includes all pre-school institutions, starting from family education, and/or early childhood education ...

, foreign policy, and science policy was rapidly changed. The funding of science was exponentially increased, with classified projects at Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission and Kahuta Research Laboratories. Bhutto also funded the classified military science and engineering projects entrusted and led by Lieutenant-General

Zahid Ali Akbar of the

.

The US lifted its arms embargo in 1975 and once again became a major source for military hardware, but by then Pakistan had become heavily dependent on China as an arms supplier. Heavy spending on defence re-energized the Army, which had sunk to its lowest morale following the debacle of the 1971 war. The high defence expenditure took money from other development projects such as education, health care and housing.

Baloch nationalist uprisings

The Baloch rebellion of the 1970s was the most-threatening

civil disorder to Pakistan since

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

's

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

. The

Pakistan Armed Forces

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

wanted to establish military garrisons in

Balochistan Province

Balochistan (; bal, بلۏچستان; ) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southwestern region of the country, Balochistan is the largest province of Pakistan by land area but is the least populated one. It shares land ...

, which at that time was quite lawless and run by tribal justice. The ethnic Balochis saw this as a violation of their territorial rights. Emboldened by the stand taken by

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman ( bn, শেখ মুজিবুর রহমান; 17 March 1920 – 15 August 1975), often shortened as Sheikh Mujib or Mujib and widely known as Bangabandhu (meaning ''Friend of Bengal''), was a Bengali politi ...

in 1971, the Baloch and Pashtun nationalists had also demanded their "provincial rights" from then-Prime Minister

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar (or Zulfiqar) Ali Bhutto ( ur, , sd, ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو; 5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979), also known as Quaid-e-Awam ("the People's Leader"), was a Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the fourt ...

in exchange for a consensual approval of the

Pakistan Constitution of 1973

The Constitution of Pakistan ( ur, ), also known as the 1973 Constitution, is the supreme law of Pakistan. Drafted by the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, with additional assistance from the country's opposition parties, it was approved by ...

. But while Bhutto admitted the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and Balochistan to a

NAP-

JUI coalition, he refused to negotiate with the provincial governments led by chief minister

Ataullah Mengal

Ataullah Mengal (; 24 March 1929 – 2 September 2021) was a Pakistani politician and feudal figure. He was the head of the Mengal tribe until he nominated one of his grandsons, Sardar Asad Ullah Mengal, as his tribal successor. He was also the ...

in

Quetta

Quetta (; ur, ; ; ps, کوټه) is the tenth most populous city in Pakistan with a population of over 1.1 million. It is situated in south-west of the country close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is the capital of ...

and Mufti Mahmud in

Peshawar

Peshawar (; ps, پېښور ; hnd, ; ; ur, ) is the sixth most populous city in Pakistan, with a population of over 2.3 million. It is situated in the north-west of the country, close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is ...

. Tensions erupted and an armed resistance began to take place.

Surveying the political instability, Bhutto's central government sacked two provincial governments within six months, arrested the two chief ministers, two governors and forty-four MNAs and MPAs, obtained an order from the

Supreme Court banning the NAP and charged them all with

high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, to be tried by a specially constituted

Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India ...

Tribunal of handpicked judges.

In time, the Baloch nationalist insurgency erupted and sucked the armed forces into the province, pitting the Baloch tribal middle classes against

Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital ...

. The sporadic fighting between the

insurgency

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

and the army started in 1973 with the largest confrontation taking place in September 1974 when around 15,000 Balochs fought the Pakistan Army, Navy and the Air Force. Following the successful recovery of

ammunition in the Iraqi embassy, shipped by both Iraq and Soviet Union for the Baluchistan resistance,

Naval Intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

launched an investigation and cited that arms were smuggled from the coastal areas of Balochistan. The Navy acted immediately, and entered the conflict. Vice-Admiral Patrick Simpson, commander of Southern Naval Command, began to launch a series of operations under a naval blockade.

The

Iranian military

The Islamic Republic of Iran Armed Forces, are the combined military forces of Iran, comprising the Islamic Republic of Iran Army (''Arteš''), the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (''Sepâh'') and the Law Enforcement Force (Police).

Iran ...

, which feared a spread of the greater Baloch resistance in Iran, aided Pakistan's military in putting down the insurrection. After three days of fighting the Baloch tribals were running out of ammunition and withdrew by 1976. The army had suffered 25 fatalities and around 300 casualties in the fight while the rebels lost 5,000 people as of 1977.

Although major fighting had broken down, ideological

schisms caused

splinter

A splinter (also known as a sliver) is a fragment of a larger object, or a foreign body that penetrates or is purposely injected into a body. The foreign body must be lodged inside tissue to be considered a splinter. Splinters may cause initia ...

groups to form and steadily gain momentum. Despite the overthrow of the Bhutto government in 1977 by General

Zia-ul-Haque, Chief of Army Staff, calls for

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

and widespread

civil disobedience remained. The

military government then appointed General

Rahimuddin Khan as

Martial Law Administrator over the Balochistan Province. The provincial military government under the famously

authoritarian General Rahimuddin began to act as a separate

entity

An entity is something that exists as itself, as a subject or as an object, actually or potentially, concretely or abstractly, physically or not. It need not be of material existence. In particular, abstractions and legal fictions are usually ...

and

military regime

A military dictatorship is a dictatorship in which the military exerts complete or substantial control over political authority, and the dictator is often a high-ranked military officer.

The reverse situation is to have civilian control of the m ...

independent of the central government.

This allowed Rahimuddin Khan to act as an absolute martial law administrator, unanswerable to the central government. Both Zia-ul-Haq and Rahimuddin Khan supported the declaration of a general amnesty in Balochistan to those willing to give up arms. Rahimuddin then purposefully isolated

feudal leaders such as

Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti

Nawab Akbar Shahbaz Khan Bugti ( Balochi, Urdu: ; 12 July 1927 – 26 August 2006) was a Pakistani politician and the Tumandar (head) of the Bugti tribe of Baloch people who served as the Minister of State for Interior and Governor of Baloc ...

and

Ataullah Mengal

Ataullah Mengal (; 24 March 1929 – 2 September 2021) was a Pakistani politician and feudal figure. He was the head of the Mengal tribe until he nominated one of his grandsons, Sardar Asad Ullah Mengal, as his tribal successor. He was also the ...

from provincial policy. He also put down all civil disobedience movements, effectively leading to unprecedented

social stability

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

within the province. Due to martial law, his reign (1977–1984) was the longest in the

history of Balochistan

The history of Balochistan began in 650 BCE with vague allusions to the region in Greek historical records. Balochistan is divided between the Pakistani province of Balochistan, the Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchestan and the Afgha ...

.

Tensions later resurfaced in the province with the Pakistan Army being involved in attacks against an insurgency known as the

Balochistan Liberation Army

The Balochistan Liberation Army ( bal, بلۏچستان آجوییء لشکر; abbreviated BLA), also known as the Baloch Liberation Army, is a Baloch ethnonationalist militant organization based in Afghanistan. The BLA's first recorded acti ...

. Attempted uprisings have taken place as recently as 2005.

Second military rule

During the 1977 elections, rumours of widespread voter fraud led to the civilian government under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto being overthrown in a

bloodless coup

A nonviolent revolution is a revolution conducted primarily by unarmed civilians using tactics of civil resistance, including various forms of nonviolent protest, to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and authoritari ...

of July 1977 (See

Operation Fair Play

Operation Fair Play was the code name for the 5 July 1977 coup by Pakistan Chief of Army Staff General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, overthrowing the government of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. The coup itself was bloodless, and was preceded by ...

). The new ruler was Chief of Army Staff General

Zia-ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, ( Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial ...

who became Chief Martial Law Administrator in 1978. Zia-ul-Haq was appointed by Bhutto after Bhutto forced seventeen senior general officers to retire. Zia appointed