Matthew Hale (jurist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

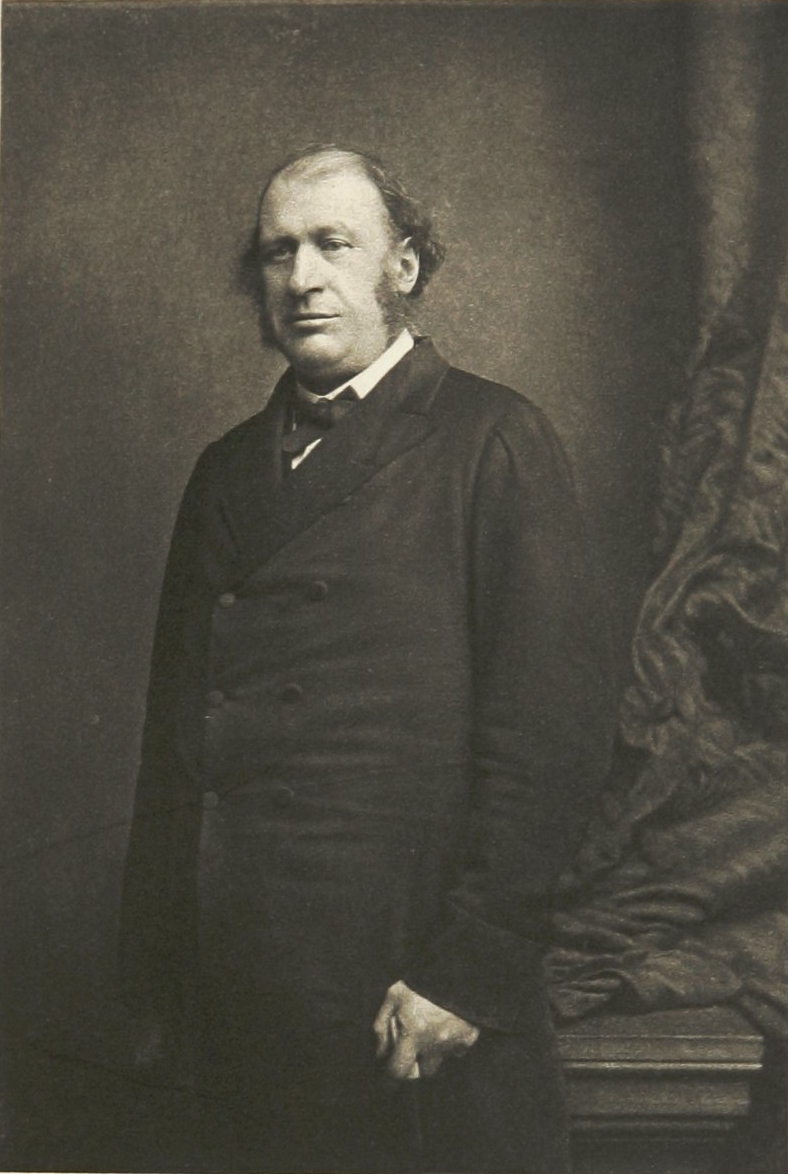

Sir Matthew Hale (1 November 1609 – 25 December 1676) was an influential English

On 17 May 1636, Hale was

On 17 May 1636, Hale was

Accessed 1 December 2022. Hale was an active MP, persuading the Commons to reject a motion to destroy the

Hale's first task in the new regime was as part of the Special Commission of 37 judges who tried the 29 regicides not included in the Declaration of Breda, between 9 and 19 October 1660. All were found guilty of treason, and 10 of them were

Hale's first task in the new regime was as part of the Special Commission of 37 judges who tried the 29 regicides not included in the Declaration of Breda, between 9 and 19 October 1660. All were found guilty of treason, and 10 of them were

Hale's posthumous legacy is his written work. He wrote a variety of texts, treatises and manuscripts, the most major of which are ''The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England'' (published 1713), and the ''

Hale's posthumous legacy is his written work. He wrote a variety of texts, treatises and manuscripts, the most major of which are ''The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England'' (published 1713), and the ''

barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, judge

A judge is a person who wiktionary:preside, presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a judicial panel. In an adversarial system, the judge hears all the witnesses and any other Evidence (law), evidence presented by the barris ...

and jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a Lawyer, legal prac ...

most noted for his treatise ''Historia Placitorum Coronæ

''Historia Placitorum Coronæ'' or ''The History of the Pleas of the Crown'' is an influential treatise on the criminal law of England, written by Matthew Hale (jurist), Sir Matthew Hale and published posthumously with notes by Sollom Emlyn by ...

'', or ''The History of the Pleas of the Crown''.

Born to a barrister and his wife, who had both died by the time he was 5, Hale was raised by his father's relative, a strict Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, and inherited his faith. In 1626 he matriculated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford (now Hertford College), intending to become a priest, but after a series of distractions was persuaded to become a barrister like his father, thanks to an encounter with a Serjeant-at-Law in a dispute over his estate. On 8 November 1628, he joined Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

, where he was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

on 17 May 1636. As a barrister, Hale represented a variety of Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

figures during the prelude and duration of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, including Thomas Wentworth and William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

; it has been hypothesised that Hale was to represent Charles I at his state trial, and conceived the defence Charles used.

Despite the Royalist loss, Hale's reputation for integrity and his political neutrality saved him from any repercussions, and under the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

he was made Chairman of the Hale Commission, which investigated law reform. Following the Commission's dissolution, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

made him a Justice of the Common Pleas.

Hale sat in Parliament, either in the Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

or the Upper House

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

, in every Parliament from the First Protectorate Parliament to the Convention Parliament, and following the Declaration of Breda was the Member of Parliament who moved to consider Charles II's reinstatement as monarch, sparking the English Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

. Under Charles, Hale was made first Chief Baron of the Exchequer

The Chief Baron of the Exchequer was the first "baron" (meaning judge) of the English Exchequer of Pleas. "In the absence of both the Treasurer of the Exchequer or First Lord of the Treasury, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, it was he who pres ...

and then Chief Justice of the King's Bench. In both positions, he was again noted for his integrity, although not as a particularly innovative judge. Following a bout of illness he retired on 20 February 1676, dying ten months later on 25 December 1676.

Hale's published works were particularly influential in the development of English common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures. The judiciary is independent, and legal principles like fairness, equality bef ...

. His ''Historia Placitorum Coronæ'', dealing with capital offences against the Crown, is considered "of the highest authority", while his ''Analysis of the Common Law'' is noted as the first published history of English law and a strong influence on William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, Justice (title), justice, and Tory (British political party), Tory politician most noted for his ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'', which became the best-k ...

's '' Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Hale's jurisprudence struck a middle-ground between Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke ( , formerly ; 1 February 1552 – 3 September 1634) was an English barrister, judge, and politician. He is often considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan and Jacobean era, Jacobean eras.

Born into a ...

's "appeal to reason" and John Selden

John Selden (16 December 1584 – 30 November 1654) was an English jurist, a scholar of England's ancient laws and constitution and scholar of Jewish law. He was known as a polymath; John Milton hailed Selden in 1644 as "the chief of learned m ...

's "appeal to contract", while refuting elements of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

's theory of natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

. Hale wrote that a man could not be charged with marital rape

Marital rape or spousal rape is the act of sexual intercourse with one's spouse without the spouse's consent. The lack of consent is the essential element and doesn't always involve physical violence. Marital rape is considered a form of dome ...

, and that view was widely held until the 1990s. However, he eliminated the previous rape defence that existed in English law for an unmarried man cohabiting with a woman.

Modern scholars also offer criticism of Hale for his execution of at least two women for witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

in the Bury St Edmunds witch trials and his belief that capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

should extend to those as young as fourteen.

Life

Early life and education

Hale was born on 1 November 1609 in West End House (now known as ''The Grange'' or ''Alderley Grange'') in Alderley, Gloucestershire to Robert Hale, a barrister ofLincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

, and Joanna Poyntz. His father gave up his practice as a barrister several years before Hale's birth "because he could not understand the reason of giving colour in pleadings".Burnet (1820), p. 2 This refers to a process through which the defendant would refer a case over the validity of his title to land to a judge instead of a jury, through claiming a (false) allegation about this right. Such an allegation would be a question of law rather than a question of fact, and as such decided by the judge with no reference to the jurors.Hostettler (2002) p. 2

Although in common use, Robert Hale apparently saw this as deceptive and "contrary to the exactness of truth and justice which became a Christian; so that he withdrew himself from the inns of court to live on his estate in the country". John Hostettler, in his biography of Matthew Hale, points out that his father's concerns about giving colour in pleadings could not have been very strong "since he not only retired to his estate at Alderley where he managed to live on his wife's inherited income, but also directed in his will that Matthew should make a career in the law".

Both of Hale's parents died before he was five; Joanna in 1612, and Robert in 1614. It was then revealed that Robert had been so generous in giving money to the poor that at his death his estate provided only £100 of income a year, of which £20 was to be paid to the local poor. Hale thus passed into the care of Anthony Kingscot, one of his father's relatives. A strong Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, Kingscot had Hale taught by a Mr. Stanton, the vicar of Wotton known as the "scandalous vicar" due to his extremist puritan views.Hostettler (2002) p. 4 On 20 October 1626, at the age of 16, Hale matriculated at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

as a member of Magdalen Hall, with the goal of becoming a priest.

Both Kingscot and Stanton had intended this to be his career, and his education had been conducted with that in mind. He was taught by Obadiah Sedgwick, another Puritan, and excelled in both his studies and fencing. Hale also regularly attended church, private prayer-meetings, and was described as "simple in his attire, and rather aesthetic". After a company of actors came to Oxford, Hale attended so many plays and other social activities that his studies began to suffer, and he began to turn away from Puritanism. In light of this, he abandoned his desire to become a priest and instead decided to become a soldier. His relatives were unable to persuade him to become a priest, or even a lawyer, with Hale describing lawyers as "a barbarous set of people unfit for anything but their own trade".

His plans to become a soldier died after a legal battle concerning his estate, in which he consulted John Glanville. Glanville successfully persuaded Hale to become a lawyer, and, after leaving Oxford at the age of 20 before obtaining a degree, he joined Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

on 8 November 1628. Fearing that the theatre might dissuade him from his legal studies as it had at Oxford, he swore "never to see a stage-play again". At around this time he was drinking with a group of friends when one of them became so drunk he fainted; Hale prayed to God to forgive and save his friend, and forgive him for his previous excesses. His friend recovered, and Hale was restored to his Puritan faith, never drinking to someone's health again (not even drinking to the King) and going to church every Sunday for 36 years. He instead settled into his studies, working for up to 16 hours a day during his first two years at Lincoln's Inn before reducing it to eight hours due to health concerns. As well as reading the law reports and statutes, Hale also studied the Roman civil law and jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

. Outside of the law, Hale studied anatomy, history, philosophy and mathematics. He refused to read the news or attend social events, and occupied himself entirely with his studies and visits to church.Flanders (1908), p. 387

Civil War, Commonwealth and Protectorate

Barrister

On 17 May 1636, Hale was

On 17 May 1636, Hale was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

by Lincoln's Inn, and immediately became the pupil of William Noy. Hale and Noy became close friends, to the point where he was referred to as "the young Noy", and more crucially he also met and befriended John Selden

John Selden (16 December 1584 – 30 November 1654) was an English jurist, a scholar of England's ancient laws and constitution and scholar of Jewish law. He was known as a polymath; John Milton hailed Selden in 1644 as "the chief of learned m ...

, a "man of almost universal learning, whose theories were to dominate much of ale'slater thought".Cromartie (1995), p. 3 Selden persuaded him to continue with his studies outside the law, and much of Hale's written work is concerned with theology and science as well as legal theory.

Hale gained a good legal practice, although he allowed his Christian faith to govern his work. He sought to help the court reach a just verdict, whatever his client's concerns, and normally returned half his fee or charged a standard fee of 10 shillings rather than allow costs to inflate. He refused to accept unjust cases, and always tried to be on the "right" side of any case; John Campbell wrote that "If he saw that a cause was unjust, he for a great while would not meddle further in it but to give his advice that it was so; if the parties after that would go on, they were to seek another counsellor, for he would assist none in acts of injustice".

Despite this, he was wealthy enough to purchase land worth £4,200 in 1648 (). He was in great demand; law reporters began recording his cases and in 1641 he advised Thomas Wentworth, the first Earl of Strafford, over his attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

for high treason. Although unsuccessful, Hale was then called to represent William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, during his impeachment by the House of Lords in October 1644.

Hale, along with John Herne, argued that none of Laud's alleged offences constituted treason, and that the Treason Act 1351 had abolished all common law treasons. John Wilde, arguing for the prosecution, admitted that none of Laud's actions amounted to treason, but argued that all of them together did. Herne, in his arguments written by Hale, retorted that "I crave your mercy, ilde I never understood before this time that two hundred couple of black rabbits would make a black horse!" The case against Laud began to fail, but Parliament issued an Act of Attainder which declared him guilty, and sentenced him to death. After the capture of Charles I, Hale was expected to defend him, and indeed offered to do so; the King refused to submit to the court, claiming he did not recognise its jurisdiction. Edward Foss writes, based on the statement of Charles Runnington, that it was Hale who actually provided the King with this defence, and that it was only because the defence prevented any counsel being called for the King that Hale did not appear in court.Foss (2000), p. 320

When it became clear that the King was losing the Civil War, and only Oxford held out, Hale decided to act as a commissioner to negotiate its surrender, fearing that the city might otherwise be destroyed. Thanks to his intercession, honourable terms were reached, and the libraries preserved. Despite practising in the politically charged environment of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

and primarily defending opponents of the resulting Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

, Hale's reputation did not suffer. First, he largely kept out of the war, even ignoring news of its progress, and instead translating ''The Life and Death of Pomponious Atticus'' into English.

Second, he was acknowledged as universally able and of high integrity during his cases, retorting to those who complained of his defence of the Royalists that he was "pleading in defence of the laws which they professed they would maintain and preserve; and that he was doing his duty to his client and was not to be daunted by such threatenings".

Hale Commission

During the rule of both the Commonwealth andthe Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotl ...

, there was considerable desire for law reform. Many judges and lawyers were corrupt, and the criminal law followed no real reason or philosophy. Any felony was punishable by death, proceedings were in a form of Norman French

Norman or Norman French (, , Guernésiais: , Jèrriais: ) is a '' langue d'oïl'' spoken in the historical and cultural region of Normandy.

The name "Norman French" is sometimes also used to describe the administrative languages of '' Angl ...

, and judges regularly imprisoned juries for reaching a verdict they disagreed with.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

and the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament describes the members of the Long Parliament who remained in session after Colonel Thomas Pride, on 6 December 1648, commanded his soldiers to Pride's Purge, purge the House of Commons of those Members of Parliament, members ...

aimed to establish a "new society", which included reforming the law. To that end, on 30 January 1652 Hale was appointed chairman of a commission to investigate law reform, which soon became known as the Hale Commission. The Commission's official remit was defined by the Commons; "taking into consideration what inconveniences there are in the law; and how the mischiefs which grow from delays, the chargeableness and irregularities in the proceedings in the law may be prevented, and the speediest way to reform the same, and to present their opinions to such committee as the Parliament shall appoint". The Commission consisted of eight lawyers and 13 laymen, which sat from 23 January approximately three times a week.

The Commission recommended various changes, such as reducing the use of the death penalty, allowing defendants access to legal counsel, legal aid and the abolition of '' peine forte et dure'' as a torture mechanism. Dissolved on 23 July 1652 after producing 16 bills, none of the Commission's recommendations immediately made it into law, although two (to abolish fines for original writs and to develop procedures for civil marriages) were brought into force through statutes by the Barebone's Parliament. Almost all of the recommendations eventually became part of English law, with John Hostettler, in his biography of Hale, writing that if the measures had been put into law immediately, "we would have been honouring such pioneers for their farsightedness in enhancing our legal system and the concept of justice".Hostettler (2002), p. 50

Justice of the Common Pleas

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, noting Hale's abilities, asked him to become a Justice of the Common Pleas. Although Hale considered that taking this commission would make others think he supported the Commonwealth, he was persuaded to do so, replacing John Puleston. Only Serjeants-at-Law could become judges, and as such Hale was made a Serjeant on 25 January 1653. He was formally appointed a Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, one of the three principal Westminster courts, on 31 January 1653,Sainty (1993) p. 76 on the condition that he "would not be required to acknowledge the usurper's authority". He also refused to put people to death for offences against the government; he believed that because the government authorising him to do so was an illegal one, "putting men to death on that account was murder". William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, Justice (title), justice, and Tory (British political party), Tory politician most noted for his ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'', which became the best-k ...

later wrote that "if judgment of death be given by a judge not authorized by lawful commission, and execution is done accordingly, the judge is guilty of murder; and upon this argument Sir Matthew Hale himself, though he accepted the place of a judge of the Common Pleas under Cromwell's government, yet declined to sit on the crown side at the assizes, and try prisoners, having very strong objections to the legality of the usurper's commission". Hale also made decisions which negatively impacted on the Commonwealth, executing a soldier for murdering a civilian in 1655, and actively refusing to attend a court hearing outside term time. On another occasion, Cromwell personally selected a jury in a trial he was concerned with, something contrary to law; as a result, Hale dismissed the jury and refused to hear the case. On 15 May 1659, Hale chose to retire, and was replaced by John Archer.

Member of Parliament

On 3 September 1654, the First Protectorate Parliament was called; of the 400 English members, only two were lawyers – Hooke, a Baron of the Exchequer, and Hale, who was elected Member of Parliament for his home county ofGloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

.History of Parliament Online – Hale, MatthewAccessed 1 December 2022. Hale was an active MP, persuading the Commons to reject a motion to destroy the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

's archives, and introducing several motions to preserve the authority of Parliament.

The first was that the government should be "in a Parliament and a single person limited and restrained as the Parliament should think fit", and he later proposed that the English Council of State

The English Council of State, later also known as the Protector's Privy Council, was first appointed by the Rump Parliament on 14 February 1649 after the execution of King Charles I.

Charles's execution on 30 January was delayed for several ho ...

be subject to re-election every three years by the House of Commons, that the militia should be controlled by Parliament, and that supplies should only be granted to the army for limited periods. While these proposals got support, Cromwell refused to allow any MPs into the Commons until they signed an oath recognising his authority, which Hale refused to do. As such, none of them were passed. Dissatisfied with the First Protectorate Parliament, Cromwell dissolved it on 22 January 1655.

A Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker of the House of Commons. In its first sess ...

was called on 17 September 1656, which wrote a constitution titled ''Humble Petition and Advice'' that called for the creation of an Upper House

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

to perform the job of the former House of Lords. Cromwell accepted this constitution, and in December 1657 nominated the Upper House's members. Hale, as a judge, was called to it. This new House's extensive jurisdiction and authority was immediately questioned by the Commons, and Cromwell responded by dissolving the Parliament on 4 February 1658. On 3 September 1658, Oliver Cromwell died and was replaced by his son, Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1658 to 1659. He was the son of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Following his father ...

. Richard Cromwell summoned a new Parliament on 27 January 1659, and Hale was returned as MP for Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

. Richard Cromwell was a weak leader, however, and ruled for only 8 months before resigning. On 16 March 1660 General Monck forced the Parliament to vote for its own dissolution and call new elections.

At the same time, Charles II made the Declaration of Breda, and when the Convention Parliament met on 25 April 1660 (with Hale a member from Gloucestershire again) it immediately began negotiations with the King. Hale moved in the Commons that "a committee might be appointed to look into the overtures that had been made, and the concessions that had been offered, by harles I and "from thence to digest such propositions, as they should think fit to be sent over to harles II who was still in Breda. On 1 May Parliament restored the King, and Charles II landed in Dover three weeks later, prompting the English Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

.

English Restoration

Chief Baron and Chief Justice

Hale's first task in the new regime was as part of the Special Commission of 37 judges who tried the 29 regicides not included in the Declaration of Breda, between 9 and 19 October 1660. All were found guilty of treason, and 10 of them were

Hale's first task in the new regime was as part of the Special Commission of 37 judges who tried the 29 regicides not included in the Declaration of Breda, between 9 and 19 October 1660. All were found guilty of treason, and 10 of them were hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was a method of torture, torturous capital punishment used principally to execute men convicted of High treason in the United Kingdom, high treason in medieval and early modern Britain and Ireland. The convi ...

. Sitting as a judge in this trial led to some viewing Hale as hypocritical, with F. A. Inderwick later writing "I confess to a feeling of pain at finding alein October 1660, sitting as a judge at the Old Bailey, trying and condemning to death batches of the regicides, men under whose orders he had himself acted, who had been his colleagues in Parliament, with whom he had sat on committees to alter the law". Perhaps as reward for this, he became Chief Baron of the Exchequer

The Chief Baron of the Exchequer was the first "baron" (meaning judge) of the English Exchequer of Pleas. "In the absence of both the Treasurer of the Exchequer or First Lord of the Treasury, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, it was he who pres ...

on 7 November 1660, replacing Sir Orlando Bridgeman. Hale had no wish to receive the knighthood that accompanied this appointment and so tried to avoid being near the King; in response, the Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

Lord Clarendon invited him to his house, where the King was present. Hale was knighted on the spot.

There were many instances of parties to a case attempting to bribe Hale. When a Duke approached him before a case "to help the judge understand a case that was to come before him", Hale said that he would only hear about cases in court. In another case, he was sent venison by a party. After noticing the man's name and verifying that he had indeed sent Hale some venison, Hale refused to let the case proceed until he had paid the man for the food. When Sir John Croke, suspected in engaging in a conspiracy, sent him some sugar loaves to excuse his absence from a case, Hale remarked that "I cannot think that Sir John believes that the King's Justices come into the country to take bribes. Some other person, having a design to put a trick upon him, sent them in his name". Hale returned the loaves, and refused to continue until Croke appeared before him. Hale was noted during this period for giving latitude to those accused of religious impropriety, and through doing so "secured the confidence and affection of all classes of his countrymen". His knowledge of equity was considered as great as his knowledge of the law, and Lord Nottingham, considered the "father of equity", "worshipped Hale as a great master".

On 2 September 1666, the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Wednesday 5 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old London Wall, Roman city wall, while also extendi ...

broke out. Over 100,000 people were made homeless, and by the time the fire ended over 13,000 houses and 400 streets had been destroyed. An Act of Parliament enacted on 8 February 1667 constituted a Court of Fire, tasked with dealing with property disputes over ownership, liability and the rebuilding of the city. Hale was tasked with sitting in this court, which met in Clifford's Inn

Clifford's Inn is the name of both a former Inn of Chancery in London and a present mansion block on the same site. It is located between Fetter Lane and Clifford's Inn Passage (which runs between Fleet Street and Chancery Lane) in the City of ...

, and heard 140 of the 374 cases the court dealt with during its first year in operation.

On 18 May 1671, Hale was made Chief Justice of the King's Bench after the death of John Kelynge. Edward Turnour replaced him as Chief Baron of the Exchequer. Hale was not noted as a particularly innovative judge, but took pains to ensure that his decisions were easy to understand and informative. Roger North wrote that "I have known the Court of King's Bench sitting every day from eight to 12, and the Lord Chief Justice Hale's managing matters of law to all imaginable advantage to the students, and in that he took a pleasure or rather pride; he encouraged arguing when it was to the purpose, and used to debate with counsel, so that the court might have been taken for an academy of sciences as well as the seat of justice". He was noted for allowing counsel to fix any problems with pleadings, and for letting them correct him if he made an error in his summing up. He disliked eloquence, writing that "If the judge or jury has a right understanding it signifies nothing but a waste of time and loss of words, and if they are weak, and easily wrought upon, it is a more decent way of corrupting them by bribing their fancies and biassing their affections." As a judge, however, he was noted by Lord Nottingham as the greatest orator on the bench.

Retirement and death

By 1675, Hale had begun to suffer from ill-health; his arms became swollen, and although a course ofbloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) was the deliberate withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and othe ...

relieved the pain temporarily, by the next February his legs were so stiff he could not walk. His initial attempts to resign as Chief Justice were declined by the King, but when Hale applied for a writ of ease the King reluctantly allowed him to retire on 20 February 1676, granting him a pension of £1,000 a year. He was replaced as Chief Justice by Richard Raynsford. After suffering for ten more months, Hale died on 25 December 1676 at his country home, The Lower House (now the site of the present day Alderley House). He was buried next to his first wife's tomb in the churchyard of St Kenelm's, the church which adjoined his home at Alderley, with a monument erected that reads:

His estate was largely left for his widow, with his legal texts given to his grandson Gabriel if Gabriel chose to study the law, and his more valuable manuscripts and books given to Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

. The male line of his family died out in 1784 with the death of Matthew Hale, his great grandson; also a barrister.

Personal life

In 1642 Hale married Anne Moore, the daughter of Sir Henry Moore, a Royalist soldier, and the granddaughter of Sir Francis Moore, a Serjeant-at-Law under James I. Moore and Hale had 10 children, but she was evidently a highly extravagant woman, with Hale warning his children that "an idle or expensive wife is most times an ill bargain, though she bring a great portion". Moore died in 1658, and in 1667 Hale married Anne Bishop, his housekeeper. Descriptions of Bishop differ; Roger North wrote that " alewas unfortunate in his family; for he married his own servant made, and then, for an excuse, said there was no wisdom below the girdle".Hostettler (2002), p. 117Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter (12 November 1615 – 8 December 1691) was an English Nonconformist (Protestantism), Nonconformist church leader and theologian from Rowton, Shropshire, who has been described as "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". He ma ...

, on the other hand, described Anne as "one of ale'sown judgment and temper, prudent and loving, and fit to please him; and that would not draw on him the trouble of much acquaintance and relations". Hale himself described her as a "most dutiful, faithful, and loving wife" who was appointed an executrix on his death.

Legacy

Hale's views on rape, marriage and abortion have had a long legacy not only in Britain's legal system, but also in those of the British Colonies. According to Edward Foss in 1870 Hale was widely considered an excellent judge and jurist, particularly through his writings: he was an "eminent judge, whom all look up to as one of the brightest luminaries of the law, as well for the soundness of his learning as for the excellence of his life". Similarly, John Campbell in his ''Lives of the Chief Justices of England'', wrote that Hale was "one of the most pure, the most pious, the most independent, and the most learned" of judges. In 1908 Henry Flanders, described Hale in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, during his lifetime as "the most learned, the most able, the most honorable man to be found in the profession of the law". Hale's writings have been cited by theUS Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

on numerous occasions. Justice Harry Blackmun cited Hale in ''"Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protected the right to have an ...

"''. Justices Elena Kagan

Elena Kagan ( ; born April 28, 1960) is an American lawyer who serves as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was Elena Kagan Supreme Court nomination ...

and Stephen Breyer

Stephen Gerald Breyer ( ; born August 15, 1938) is an American lawyer and retired jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1994 until his retirement in 2022. He was nominated by President Bill Clinton, and r ...

in ''" Kahler v. Kansas"''. In 2022, Hale's opinion on abortion was cited by Samuel Alito

Samuel Anthony Alito Jr. ( ; born April 1, 1950) is an American jurist who serves as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was Samuel Alito Supreme Court ...

in his opinion of ''Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization

''Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization'', 597 U.S. 215 (2022), is a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court in which the court held ...

'', generating political controversy.

In 1993, in the case of ''R v Kingston'', the Court of Appeal relied on his statement that "drunkenness is not a defence" to uphold a conviction. William Holdsworth argued in 1923 that it was his learning in Roman law and jurisprudence which allowed him to work so effectively; because he had seen other legal systems at work, he "could both criticise the defects of English law and state its rules in a more orderly form than they had ever been stated before". Hale's political neutrality and personal integrity has been attributed by Berman in 1994 to his Puritanism, and his support of the common law; "Regimes come and go, the common law abides...For Hale...legal continuity was vital for civic identity".

Hale has frequently been compared with Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke ( , formerly ; 1 February 1552 – 3 September 1634) was an English barrister, judge, and politician. He is often considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan and Jacobean era, Jacobean eras.

Born into a ...

. Campbell considered Hale to be the superior lawyer, because while he failed to engage in public life he treated law as a science, and maintained judicial independence and neutrality. In 2002, Hostettler said, while considering Hale a better lawyer than Coke and more influential, that Coke was better overall. While Hale was in possession of judicial impartiality, and his written works are considered highly important, his lack of venture into public affairs limited his progressive influence. Coke's active intervention allowed him to "breath new life into medieval law and use it to oppose conciliar justice", encouraging judges to be more independent and "unfettered except by the common law whose supremacy it was their duty to uphold".

J. H. Corbett wrote in the ''Alberta Law Quarterly'' in 1942, that with Hale's popularity at the time (Parliamentary constituencies "fought over the privilege of returning him") he could have been just as successful as Coke if he had chosen to take an active role in public affairs.

Writings

Hale's posthumous legacy is his written work. He wrote a variety of texts, treatises and manuscripts, the most major of which are ''The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England'' (published 1713), and the ''

Hale's posthumous legacy is his written work. He wrote a variety of texts, treatises and manuscripts, the most major of which are ''The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England'' (published 1713), and the ''Historia Placitorum Coronæ

''Historia Placitorum Coronæ'' or ''The History of the Pleas of the Crown'' is an influential treatise on the criminal law of England, written by Matthew Hale (jurist), Sir Matthew Hale and published posthumously with notes by Sollom Emlyn by ...

'', or ''The History of the Pleas of the Crown'' (published 1736).

The ''Analysis'' was based on lectures he gave to students, and was most likely not intended to be published; it is considered the first history of English law ever written.Berman (1994), p. 1705 Divided into 13 chapters, the book dealt with the history of English law and some suggestions for reform. William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, Justice (title), justice, and Tory (British political party), Tory politician most noted for his ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'', which became the best-k ...

, when writing his '' Commentaries on the Laws of England'', noted in his preface that "of all the earlier schemes for digesting the Laws of England the most natural and scientific, as well as the most comprehensive, appeared to be that of Sir Matthew Hale in his posthumous Analysis of the Law". Hale proposed the creation of county courts, and also drew a strong distinction between written laws, such as statutes, and customary, unwritten laws. He also argued that the common law was subject to Parliament, far before the confirmation of Parliamentary supremacy, and that the law should protect the rights and civil liberties of the King's subjects. He also argued for the confirmation of trial by jury, which he described as "the best mode of trial in the world", while the 13th chapter divided the law into the laws of persons and of property, and dealt with the rights, wrongs and remedies recognised by the law at the time. William Holdsworth, himself considered one of the greatest common law historians, described it as "the ablest introductory sketch of a history of English law that appeared till the publication of Pollock and Maitland's volumes in 1895".

The ''Historia'' is perhaps Hale's most famous work. Pleas of the Crown were capital offences committed "against the peace of our Lord the King, his Crown and dignity"; as such, the book dealt with capital crimes and the associated procedure. The 710-page work followed the pattern of Coke's ''Institutes of the Lawes of England

The ''Institutes of the Lawes of England'' are a series of legal treatises written by Sir Edward Coke. They were first published, in stages, between 1628 and 1644. Widely recognized as a foundational document of the common law, they have been cit ...

'', but was far more methodical; James Fitzjames Stephen

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, 1st Baronet, Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India, KCSI (3 March 1829 – 11 March 1894) was an English lawyer, judge, writer, and philosopher. One of the most famous critics of John Stuart Mill, S ...

said that Hale's work "was not only of the highest authority but shows a depth of thought which puts it in quite a different category from Coke's ''Institute''... tis far more of a treatise and far less of an index or mere work of practice".Hostettler (2002), p. 151 The book dealt with the criminal capacity of infants, insanity and idiocy, the defence of drunkenness, capital offences, treason, homicide and theft. Hale endorses the application of capital punishments to children in ''Historia'', writing that "it is clear that an infant above fourteen years is equally subject to capital punishments as others of full age; for it is ''presumptio juris'', that after fourteen years they are ''doli capaces'', and can discern between good and evil".

In the 19th century, Andrew Amos wrote a critique of the ''Historia'' titled ''Ruins of Time exemplified in Sir Matthew Hale's History of the Pleas of the Crown'', which both criticised and praised Hale's work while directing the main criticism at the judges and lawyers who cited the ''Historia'' without considering that it was dated.

Hale also reorganised the first of Coke's ''Institutes'', which dealt with Thomas de Littleton

Sir Thomas de Littleton or de Lyttleton Order of the Bath, KB Serjeant-at-law, SL(c. 1407–23 August 1481) was an English judge, undersheriff, Lord of Tixall Gatehouse, Tixall Manor, and legal writer from the Lyttelton family. He was also ma ...

's ''Treatise on Tenures''; Hale's edition was the most commonly used, and the first to extract Coke's broader philosophical points. His written works, however, were fragmentary, and did not individually lay out his jurisprudence. Harold J. Berman, writing in the ''Yale Law Journal

''The Yale Law Journal'' (YLJ) is a student-run law review affiliated with the Yale Law School. Published continuously since 1891, it is the most widely known of the eight law reviews published by students at Yale Law School. The journal is one ...

'', notes that it is only "possible by a study of the entire corpus of Hale's writings to reconstruct the coherent legal philosophy that underlies them".

Hale's writings on witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

and marital rape

Marital rape or spousal rape is the act of sexual intercourse with one's spouse without the spouse's consent. The lack of consent is the essential element and doesn't always involve physical violence. Marital rape is considered a form of dome ...

were extremely influential. In 1662, he was involved in " one of the most notorious of the seventeenth century English witchcraft trials", where he sentenced two women (Amy Duny and Rose Cullender) to death for witchcraft. The judgment of Hale in this case was extremely influential in future cases, and was used in the Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Not everyone wh ...

to justify the forfeiture of the accused's lands. As late as 1664, Hale used the argument that the existence of laws against witches is proof that witches exist.

Hale believed that a marriage was a contract, which merged the legal entities of husband and wife into one body. As such, "The husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract". This exception to the law of rape existed in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

until 1991, primarily due to his influence, until it was repealed by the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

in '' R v R''. At the same time as he said a husband cannot be guilty of rape, Hale eliminated the previous rape defence that existed in English law for a man cohabiting with a woman (as opposed to being married to the woman), on the ground that cohabitation does not involve any contract.

According to a 1978 article by G. Geis in the '' British Journal of Law and Society'', Hale's opinions on witchcraft are closely tied to his writings on marital rape, which are found in the ''Historia''. Geis argues that both arose from misogynistic bias.

Although Hale wrote voluminously, he published little in his lifetime: his writings were discovered and published by others after his death. There are still dozens of volumes of his manuscripts that remain unpublished, including numerous theological treatises. The majority of these manuscripts are found in the Fairhurst Papers at Lambeth Palace Library. His largest work in manuscript, "De Deo" (ca. 1662–1667), consists of ten books filling five volumes and is estimated to contain nearly a million words. There are also three copies of a treatise on natural law at the British Library. A critical edition of this treatise on natural law has been published as ''Of the Law of Nature'' (2015), which contains chapters on law in general and the law of nature. In the same work, Hale criticizes the reduction of natural law to self-preservation as "the only Cardinall Law" (the view normally associated with Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

), cites John Selden

John Selden (16 December 1584 – 30 November 1654) was an English jurist, a scholar of England's ancient laws and constitution and scholar of Jewish law. He was known as a polymath; John Milton hailed Selden in 1644 as "the chief of learned m ...

's ''De jure naturali et gentium juxta disciplinam Ebraeorum'' repeatedly, and appears to share conceptual continuities with both Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

's '' De jure belli ac pacis'' and Francisco Suárez's ''Tractatus de legibus ac deo legislatore''.

Jurisprudence

During Hale's period as a barrister and judge, the general conclusion in England was that the repository of the law and conventional wisdom was not politics, as in Renaissance Europe, but the common law. This had been brought about thanks to SirEdward Coke

Sir Edward Coke ( , formerly ; 1 February 1552 – 3 September 1634) was an English barrister, judge, and politician. He is often considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan and Jacobean era, Jacobean eras.

Born into a ...

, who in his ''Institutes'' and practice as a judge advocated judge-made law. Coke asserted that judge-made law had the answer to any question asked of it, and as a result, "a learned judge... was the natural arbiter of politics".Cromartie (1995) p. 17 This principle was known as the "appeal to reason", with "reason" referring not to rationality but the method and logic used by judges in upholding and striking down laws. Coke's theory meant that certainty of the law and "intellectual beauty" was the way to see if a law was just and correct, and that the system of law could eventually become sophisticated enough to be predictable. John Selden held similar beliefs, in that he thought that the common law was the proper law of England. However, he argued that this did not necessarily create judicial discretion to play with it, and that proper did not necessarily equal perfect. The law was nothing more than a contract made by the English people; this is known as the "appeal to contract". Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

argued against Coke's theory. Along with Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

, he argued for natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

, created by the King's authority, not by any individual judge. Hobbes felt that there was no skill unique to lawyers, and that the law could be understood not through Coke's "reason" (the method used by lawyers) but through understanding the King's instructions. While the judges did make law, this was only valid because it was "tacitly confirmed (because not disapproved) by the ing

Ing, ING or ing may refer to:

Art and media

* '' ...ing'', a 2003 Korean film

* i.n.g, a Taiwanese girl group

* The Ing, a race of dark creatures in the 2004 video game '' Metroid Prime 2: Echoes''

* "Ing", the first song on The Roches' 199 ...

.

Hale's legal theory was highly influenced by both Coke and Selden. He argued that the making of the law was a contract, but that it was subject to a test of "reasonable" character, something that only the judges could rule on. In this way, he sat in a middle ground between Selden and Coke. This was in conflict with the argument of Hobbes. In 1835, Hale's "Reflections on Hobbes' ''Dialogue''" was discovered; Frederick Pollock posits that since Hobbes' ''Dialogue'' was first published in 1681, six years after Hale's death, Hale must have seen an early copy or draft. D.E.C. Yale, writing in the ''Cambridge Law Journal

''The Cambridge Law Journal'' is a peer-reviewed academic law journal, and the principal academic publication of the Faculty of Law, University of Cambridge. It is published by Cambridge University Press, and is the longest established university ...

'', suggests that Chief Justice Vaughan had access to the ''Dialogue'', and may have passed a copy on to Hale before his death. In his ''Reflections'', Hale agreed with Coke that the judge's task was to bring the reason of the common law (the coherence of the legal system) in line with the reason of the law in question (to justify that law). He disagreed with Hobbes that a layman could understand the law, saying that "he that hath been educated in the study of the law hath a great advantage over those that have been otherwise exercised". The distinction between Coke and Hale is that Hale agreed with Selden that law was created through agreement, and disagreed that reason had an inherent binding power. Hale agreed with Hobbes that the interpretation of the law could not be left to individual reason, and that the law is not an exact science; the best that can be produced is a set of laws which give a reasonable outcome in the majority of cases.

List of works

Hale's full works include: *''Contemplations, Moral and Divine'' (1676). *''The Primitive Origination of Mankind, Considered and Examined According to the Light of Nature'' (1677). *''The Life and Death of Pomponius Atticus written by his contemporary and acquaintance Cornelius Nepos. Translated out of his fragments, together with observations political and moral thereon'' (1677). *''Pleas of the Crown. A Methodical Summary'' (1678). *''A Discourse of the Knowledge of God and of Ourselves'' (1688). *''On Pomponious Atticus'' (1689). *''Origin of Mankind by Natural Propagation''. *''The Original Institution, Power and Jurisdiction of Parliament'' (1707). *''The History of the Common Law of England'' (1713). *''Government in General, its Origin, Alteration and Trials''. *''The History of the Pleas of the Crown'' (1736). *''The Analysis of the Law. Being a Scheme, or Abstract, of the several Titles and Partitions of the Law of England, Digested into Method'' (1739). *''Considerations Touching the Amendment or Alterations of Laws'' (1787). *''The Jurisdiction of the Lord's House, or, Parliament Considered According to Ancient Records'' (1796). *''Reflections on Hobbes' Dialogue of the Law'' (1835). *''The Prerogatives of the King'' (Selden Society, 1976) *''A Disquisition Touching the Jurisdiction of the... Courts of Admiralty'' (Selden Society, 1993) *''Of the Law of Nature'' (2015). He also wrote the preface to '' Rolle's Abridgment''. Marvin, J. G., ''Legal Bibliography, or a thesaurus of American, English, Irish and Scotch law books:together with some continental treatises.'' T & J W Johnson. 1847. p. 617.References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hale, Matthew 1609 births 1676 deaths Alumni of Magdalen Hall, Oxford Chief Barons of the Exchequer English MPs 1654–1655 English MPs 1656–1658 English MPs 1659 English MPs 1660 English subscribers to the Solemn League and Covenant 1643 Politicians from Gloucestershire Justices of the common pleas Knights Bachelor Lay members of the Westminster Assembly Lord chief justices of England and Wales Members of Lincoln's Inn Members of the pre-1707 Parliament of England for the University of Oxford People from Alderley, Gloucestershire Serjeants-at-law (England) Witch hunters Witch trials in England