Matthew Flinders on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1799 Flinders' request to explore the coast north of Port Jackson was granted and once more the sloop ''Norfolk'' was assigned to him. Bass had by this stage returned to Britain and in his place Flinders recruited his brother Samuel Flinders and a Kuringgai man named Bungaree for the voyage. They departed on 8 July 1799 and arrived in Moreton Bay six days later. He rowed ashore at Woody Point () and named a point west of that () as 'Redcliffe' (on account of its red cliffs). That point is now known as Clontarf Point, while the name 'Redcliffe' is used by the town of Redcliffe to the north. He landed on

In 1799 Flinders' request to explore the coast north of Port Jackson was granted and once more the sloop ''Norfolk'' was assigned to him. Bass had by this stage returned to Britain and in his place Flinders recruited his brother Samuel Flinders and a Kuringgai man named Bungaree for the voyage. They departed on 8 July 1799 and arrived in Moreton Bay six days later. He rowed ashore at Woody Point () and named a point west of that () as 'Redcliffe' (on account of its red cliffs). That point is now known as Clontarf Point, while the name 'Redcliffe' is used by the town of Redcliffe to the north. He landed on

In March 1800, Flinders rejoined ''Reliance'' and returned to Britain. During the voyage, the Antipodes Islands were discovered and charted.

Flinders' work had come to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his ''Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc.''. Banks used his influence with Earl Spencer to convince the

In March 1800, Flinders rejoined ''Reliance'' and returned to Britain. During the voyage, the Antipodes Islands were discovered and charted.

Flinders' work had come to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his ''Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc.''. Banks used his influence with Earl Spencer to convince the

Aboard ''Investigator'', Flinders reached and named

Aboard ''Investigator'', Flinders reached and named

Skeleton of renowned explorer Matthew Flinders is lying in the path of London rail link — and could be exhumed

News Limited Network, 28 February 2014. Accessed 13 April 2014. The Gardens were closed to the public in 2017 for work on the High Speed 2 (HS2) rail project which requires the expansion of Euston station. The grave was located in January 2019 by archaeologists. His coffin was identified by its well-preserved lead coffin plate. Film of the discovery and the exhumation was shown in a documentary on British television in September 2020. It was proposed to re-bury his remains, at a site to be decided, after they had been examined by osteo-archaeologists. Following the discovery of his grave the parish church of Donington, Lincolnshire, Flinders' birthplace, saw a surge of visitors. The 'Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home Group' and the Britain-Australia Society, as well as Flinders' direct descendants, campaigned to have his remains interred at the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood in Donington. On 17 October 2019 HS2 Ltd announced that Flinders remains could be reinterred in the church in Donington, where he was baptised. Permission has been given by the Diocese of Lincoln for reburial in the north aisle.

Following the discovery of his grave the parish church of Donington, Lincolnshire, Flinders' birthplace, saw a surge of visitors. The 'Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home Group' and the Britain-Australia Society, as well as Flinders' direct descendants, campaigned to have his remains interred at the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood in Donington. On 17 October 2019 HS2 Ltd announced that Flinders remains could be reinterred in the church in Donington, where he was baptised. Permission has been given by the Diocese of Lincoln for reburial in the north aisle.

Flinders' map Y46/1 was never "lost". It had been stored and recorded by the

Flinders' map Y46/1 was never "lost". It had been stored and recorded by the  Banks wrote a draft of an introduction to Flinders' ''Voyage'', referring to the map published by Melchisédech Thévenot in ''Relations des Divers Voyages'' (1663), and made well known to English readers by Emanuel Bowen's adaptation of it, ''A Complete Map of the Southern Continent'', published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris's ''Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels'' (1744–48, and 1764). Banks said in the draft:

Although Thévenot said that he had taken his chart from the one inlaid into the floor of the Amsterdam Town Hall, in fact it appears to be an almost exact copy of that of

Banks wrote a draft of an introduction to Flinders' ''Voyage'', referring to the map published by Melchisédech Thévenot in ''Relations des Divers Voyages'' (1663), and made well known to English readers by Emanuel Bowen's adaptation of it, ''A Complete Map of the Southern Continent'', published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris's ''Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels'' (1744–48, and 1764). Banks said in the draft:

Although Thévenot said that he had taken his chart from the one inlaid into the floor of the Amsterdam Town Hall, in fact it appears to be an almost exact copy of that of

Although he never used his own name for any feature in all his discoveries, Flinders' name is now associated with over 100 geographical features and places in Australia,The intrepid spirit of Matthew Flinders lives on in more than 100 Australian sites

Although he never used his own name for any feature in all his discoveries, Flinders' name is now associated with over 100 geographical features and places in Australia,The intrepid spirit of Matthew Flinders lives on in more than 100 Australian sites

''ABC News'', 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019. including Flinders Island in Bass Strait, but not Flinders Island in South Australia, which he named for his younger brother, Samuel Flinders. Flinders is seen as being particularly important in South Australia, where he is considered the main explorer of the state. Landmarks named after him in South Australia include the Flinders Ranges and

* ''Trim: Being the True Story of a Brave Seafaring Cat''. * ''Private Journal 1803–1814''. Edited with an introduction by Anthony J. Brown and Gillian Dooley. Friends of the State Library of South Australia, 2005. * *

Flinders, Matthew (1774–1814)

National Library of Australia, ''Trove, People and Organisation'' record for Matthew Flinders

at the State Library of New South Wales.

The Flinders Papers

an

Charts by Matthew Flinders

at the UK National Maritime Museum *

Works by Matthew Flinders

at Project Gutenberg Australia *

Flinders Providence Logbook

Naming of Australia

Matthew Flinders' map of Australia

High resolution image of the complete map.

Flinders' Journeys – State Library of NSW

Biography at BBC Radio Lincolnshire

Voyages of Captain Matthew Flinders in Australia

Google Earth Virtual Tour

at the

British Atmospheric Data Centre

A Voyage to Terra Australis, Volume 1

– National Museum of Australia * Matthew Flinders: Placing Australia on the map

at the State Library of New South Wales {{DEFAULTSORT:Flinders, Matthew Royal Navy officers English explorers English sailors English cartographers English hydrographers Explorers of Australia Explorers of Western Australia Explorers of Queensland Explorers of South Australia Hydrographers People from Donington, Lincolnshire 1774 births 1814 deaths Maritime exploration of Australia Maritime writers Articles containing video clips Pre-Separation Queensland Sea captains 2019 archaeological discoveries English navigators Royal Navy sailors

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was a British navigator and cartographer who led the first inshore

A shore or a shoreline is the fringe of land at the edge of a large body of water, such as an ocean, sea, or lake. In physical oceanography, a shore is the wider fringe that is geologically modified by the action of the body of water pas ...

circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the ...

of mainland Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, then called New Holland. He is also credited as being the first person to utilise the name ''Australia'' to describe the entirety of that continent including Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

), a title he regarded as being "more agreeable to the ear" than previous names such as ''Terra Australis''.

Flinders was involved in several voyages of discovery between 1791 and 1803, the most famous of which are the circumnavigation of Australia and an earlier expedition when he and George Bass confirmed that Van Diemen's Land was an island.

While returning to Britain in 1803, Flinders was arrested by the French governor at Isle de France (Mauritius)

Isle de France () was the name of the Indian Ocean island which is known as Mauritius and its dependent territories between 1715 and 1810, when the area was under the French East India Company and a part of the French colonial empire. Und ...

. Although Britain and France were at war, Flinders thought the scientific nature of his work would ensure safe passage, but he remained under arrest for more than six years. In captivity, he recorded details of his voyages for future publication, and put forward his rationale for naming the new continent 'Australia', as an umbrella term for New Holland and New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

– a suggestion taken up later by Governor Macquarie.

Flinders' health had suffered, however, and although he returned to Britain in 1810, he did not live to see the success of his widely praised book and atlas, ''A Voyage to Terra Australis

''A Voyage to Terra Australis: Undertaken for the Purpose of Completing the Discovery of that Vast Country, and Prosecuted in the Years 1801, 1802, and 1803, in His Majesty's Ship the Investigator'' was a sea voyage journal written by English mari ...

''. The location of his grave was lost by the mid-19th century but archaeologists, excavating a former burial ground near London's Euston railway station for the High Speed 2 (HS2) project, announced in January 2019 that his remains had been identified.

Early life

Matthew Flinders was born in Donington, Lincolnshire, the son of Matthew Flinders, a surgeon, and his wife Susannah ( Ward). He was educated at Cowley's Charity School, Donington, from 1780 and then at the Reverend John Shinglar's Grammar School atHorbling

__NOTOC__

Horbling is a village and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. It lies on the B1177, south-east of Sleaford, north-east of Grantham and north of Billingborough.

Village population recorded in the ...

in Lincolnshire.

In his own words, he was "induced to go to sea against the wishes of my friends from reading '' Robinson Crusoe''", and in 1789, at the age of fifteen, he joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Under the patronage of Captain Thomas Pasley, Flinders was initially assigned to as a servant, but was soon transferred as an able-seaman to , and then in July 1790 was made midshipman on .

Early career

Midshipman to Captain Bligh

In May 1791, on Pasley's recommendation, Flinders joined Captain William Bligh's expedition on transportingbreadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of '' Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Phil ...

from Tahiti to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

. This was Bligh's second "Breadfruit Voyage" following on from the ill-fated voyage of HMS ''Bounty''. The expedition sailed via the Cape of Good Hope and in February 1792, they arrived at Adventure Bay in the south of what is now called Tasmania. The officers and crew spent over a week in the region obtaining water and lumber, and interacting with local Aboriginal people. This was Flinders' first direct association with the Australian continent. After the expedition arrived in Tahiti in April 1792, obtaining the many breadfruit plants to take to Jamaica, they sailed back west. Instead of travelling via Adventure Bay, Bligh navigated to the north of the Australian continent, sailing through the Torres Strait. Here, off Zagai Island, they were involved in a naval skirmish with armed local men in a flotilla of sailing canoes, which resulted in the death of several Islanders and one crewman. The expedition arrived in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

in February 1793, offloading the breadfruit plants, and then returned to England with Flinders disembarking in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in August 1793 after more than two years at sea.

HMS ''Bellerophon''

In September 1793, Flinders re-joined under the command of Captain Pasley. In 1794, Flinders served on this vessel during the battle known as the Glorious First of June, the first and largest fleet action of the naval conflict between theKingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

and the First French Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

. Flinders wrote a detailed journal of this intense battle including how Captain Pasley "lost his leg by an 18-pound shot, which came through the barricading of the quarter-deck." Both Pasley and Flinders survived, with Flinders deciding to pursue a preference for exploratory rather than military naval commissions.

Exploration around New South Wales

Flinders' desire for adventure led him to enlist as a midshipman aboard in 1795. This vessel was headed toNew South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

carrying the recently appointed governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of that British colony, Captain John Hunter. On this voyage Flinders, became friends with the ship's surgeon George Bass who was three years his senior and had been born at Aswarby

Aswarby () is a village in the North Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England.

It is south of Sleaford and east of the A15 road, between Sleaford and the point near Threekingham where it crosses the A52 road.

With the village of Swarby, ...

from Donington.

Expeditions in ''Tom Thumb'' and ''Tom Thumb II''

HMS ''Reliance'' arrived inPort Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman S ...

in September 1795, and Bass and Flinders soon organised an expedition in a small open boat named ''Tom Thumb'' in which they sailed with a boy William Martin to Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

and up the Georges River. In March 1796, the two explorers again with William Martin, set out on another voyage in a larger boat dubbed ''Tom Thumb II''. They sailed south from Port Jackson but were soon forced to beach at Red Point (Port Kembla)

Red Point () is a coastal headland at Port Kembla in New South Wales, Australia. Martin Islet lies just off the point.

The point was named by Captain Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728Old Style and New Style dates, Old Style date: 27 Oct ...

. At this place they accepted the help of two Aboriginal men who piloted the boat to the entrance of Lake Illawarra

Lake Illawarra ( Aboriginal Tharawal language: various adaptions of ''Elouera'', ''Eloura'', or ''Allowrie''; ''Illa'', ''Wurra'', or ''Warra'' meaning pleasant place near the sea, or, high place near the sea, or, white clay mountain), is an op ...

. Here they were able to dry their gunpowder and obtain supplies of water from another group of Aboriginal people. During the return to Sydney they had to seek shelter at Wattamolla

Wattamolla, also known as Wattamolla Beach, is a cove, lagoon, and beach on the New South Wales coast south of Sydney, within the Royal National Park.

History

Wattamolla is the local Aboriginal name of the area, meaning "place near running ...

and also explored some of Port Hacking (Deeban).

Circumnavigation of Van Diemen's Land

In 1798, Matthew Flinders, now alieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

, was given command of the sloop with orders "to sail beyond Furneaux's Islands, and, should a strait be found, pass through it, and return by the south end of Van Diemen's Land". Flinders and Bass had in the months previously both made separate journeys exploring the region but neither were conclusive toward the existence of a strait. Flinders, with Bass and several crewmen, sailed the ''Norfolk'' along the uncharted northern and western coasts of Van Diemen's Land, rounded Cape Pillar

Cape Pillar is a rural locality in the local government area (LGA) of Tasman in the South-east LGA region of Tasmania. The locality is about south-east of the town of Nubeena. The 2016 census recorded a population of 4 for the state suburb o ...

and returned to Furneaux's Islands. By doing so, Flinders had completed the circumnavigation of Van Diemen's Land and confirmed the presence of a strait between it and the mainland. The passage was named Bass Strait

Bass Strait () is a strait separating the island states and territories of Australia, state of Tasmania from the Australian mainland (more specifically the coast of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, with the exception of the land border across Bo ...

after his close friend, and the largest island in the strait would later be named Flinders Island in his honour. During the voyage, Flinders and Bass rowed the ship's dinghy for some miles up the River Derwent where they had their only encounter with Aboriginal Tasmanians.

Expedition to Hervey Bay

In 1799 Flinders' request to explore the coast north of Port Jackson was granted and once more the sloop ''Norfolk'' was assigned to him. Bass had by this stage returned to Britain and in his place Flinders recruited his brother Samuel Flinders and a Kuringgai man named Bungaree for the voyage. They departed on 8 July 1799 and arrived in Moreton Bay six days later. He rowed ashore at Woody Point () and named a point west of that () as 'Redcliffe' (on account of its red cliffs). That point is now known as Clontarf Point, while the name 'Redcliffe' is used by the town of Redcliffe to the north. He landed on

In 1799 Flinders' request to explore the coast north of Port Jackson was granted and once more the sloop ''Norfolk'' was assigned to him. Bass had by this stage returned to Britain and in his place Flinders recruited his brother Samuel Flinders and a Kuringgai man named Bungaree for the voyage. They departed on 8 July 1799 and arrived in Moreton Bay six days later. He rowed ashore at Woody Point () and named a point west of that () as 'Redcliffe' (on account of its red cliffs). That point is now known as Clontarf Point, while the name 'Redcliffe' is used by the town of Redcliffe to the north. He landed on Coochiemudlo Island

Coochiemudlo Island is a small island in the southern part of Moreton Bay, near Brisbane, in South East Queensland, Australia. It is also the name of the locality upon the island, which is within the local government area of Redland City.

In th ...

() on 19 July while he was searching for a river in the southern part of Moreton Bay.

In the northern part of Moreton Bay, Flinders explored a narrow waterway () which he named the Pumice Stone River (presumably unaware it separated Bribie Island

Bribie Island is the smallest and most northerly of three major sand islands forming the coastline sheltering the northern part of Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia. The others are Moreton Island and North Stradbroke Island. Bribie Island i ...

and the mainland); it is now called the Pumicestone Passage. Most of the meetings between the Aboriginal people of Moreton Bay and Flinders were of a friendly nature, but on 15 July at the southern tip of Bribie Island, a spear was thrown which resulted in a local man being wounded by gunfire. Flinders named the place where this occurred Point Skirmish. While anchored in Pumicestone, Flinders ventured several kilometres overland with three crew including Bungaree and climbed the mountain Beerburrum

Beerburrum is a small town and coastal locality in the Sunshine Coast Region, Queensland, Australia. In the , Beerburrum had a population of 763 people.

Geography

The locality is north of the state capital, Brisbane. The Bruce Highway passes ...

. They turned back after meeting the steep cliffs of Mount Tibrogargan

Mount Tibrogargan is a small mountain in the Glass House Mountains National Park, north-northwest of Brisbane, Australia. It is a magma intrusion of hard alkali rhyolite that squeezed up into the vents of an ancient volcano 27 million years ago ...

on about 26 July.

Exiting Moreton Bay, Flinders continued north exploring as far as Hervey Bay before returning south. They arrived back in Sydney on 20 August 1799.

Command of ''Investigator''

In March 1800, Flinders rejoined ''Reliance'' and returned to Britain. During the voyage, the Antipodes Islands were discovered and charted.

Flinders' work had come to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his ''Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc.''. Banks used his influence with Earl Spencer to convince the

In March 1800, Flinders rejoined ''Reliance'' and returned to Britain. During the voyage, the Antipodes Islands were discovered and charted.

Flinders' work had come to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his ''Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc.''. Banks used his influence with Earl Spencer to convince the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

of the importance of an expedition to chart the coastline of New Holland. As a result, in January 1801, Flinders was given command of , a 334-ton sloop, and promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

the following month.

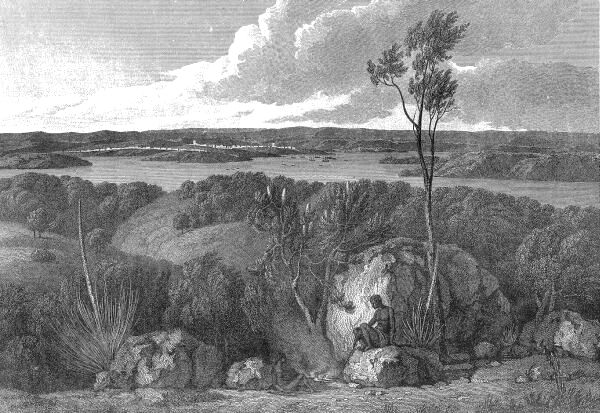

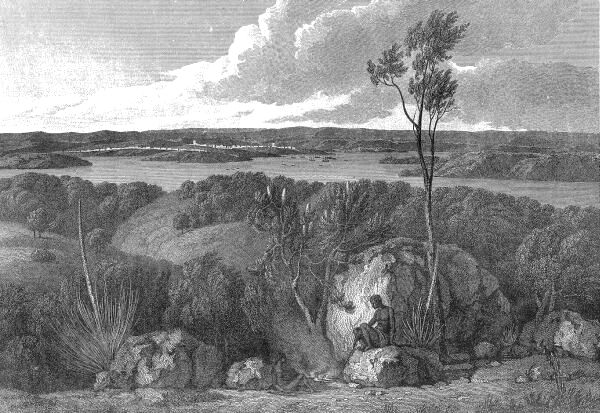

''Investigator'' set sail for New Holland on 18 July 1801. Attached to the expedition were the botanist Robert Brown, botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer, landscape artist William Westall

William Westall (12 October 1781 – 22 January 1850) was a British landscape artist best known as one of the first artists to work in Australia.

Early life

Westall was born in Hertford and grew up in London, mostly Sydenham and Hampstead. ...

, gardener Peter Good Peter Good (date of birth unknown, died 12 June 1803) was the gardener assistant to botanist Robert Brown on the voyage of HMS ''Investigator'' under Matthew Flinders, during which the coast of Australia was charted, and various plants collected.

...

, geological assistant John Allen, and John Crosley as astronomer.Vallance, T.G., Moore, D.T. & Groves, E.W. 2001. ''Nature's Investigator The Diary of Robert Brown in Australia'', 1801-1805, Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra, (p.7) Vallance ''et al.'' comment that compared to the Baudin expedition this was a 'modest contingent of scientific gentlemen', which reflects 'British parsimony' in scientific endeavour.

Exploration of the Australian coastline

Surveying the southern coast

Aboard ''Investigator'', Flinders reached and named

Aboard ''Investigator'', Flinders reached and named Cape Leeuwin

Cape Leeuwin is the most south-westerly (but not most southerly) mainland point of the Australian continent, in the state of Western Australia.

Description

A few small islands and rocks, the St Alouarn Islands, extend further in Flinders B ...

on 6 December 1801, and proceeded to make a survey along the southern coast of the Australian mainland. The expedition soon anchored in King George Sound and stayed there for a month exploring the area. The local Aboriginal people initially indicated that Flinders' group should "return from whence they came", but relations improved to the point where one resident participated in musket-drill with the ship's marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

. In nearby Oyster Harbour

Oyster Harbour is a permanently open estuary, north of King George Sound, which covers an area of near Albany, Western Australia. The harbour is used to shelter a fishing fleet carrying out commercial fishing and the farming of oysters and muss ...

, Flinders found a copper plate that Captain Christopher Dixson, on , had left the year before.

While approaching Port Lincoln, which Flinders named after his home county of Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

, eight of his crew were lost when the small boat they were attempting to get to land with, capsized. Flinders named nearby Memory Cove in their honour. On 21 March 1802, the expedition reached a large island where many kangaroos were sighted. Flinders and some crew went ashore and found the animals so tame they could walk right up to them. They killed 31 kangaroos with Flinders writing that "in gratitude for so seasonable a supply f meat I named this southern land Kangaroo Island." The seals on the island proved less docile with a crew member receiving a severe bite from one.

On 8 April 1802, while sailing east, Flinders sighted , a French corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

commanded by the explorer Nicolas Baudin

Nicolas Thomas Baudin (; 17 February 1754 – 16 September 1803) was a French explorer, cartographer, naturalist and hydrographer, most notable for his explorations in Australia and the southern Pacific.

Biography

Early career

Born a comm ...

, who was on a similar expedition for his government. Both men of science, Flinders and Baudin exchanged details of their discoveries, despite believing that their countries were at war. Flinders named the bay in which they met Encounter Bay.

Proceeding along the coast, Flinders explored Port Phillip (the site of the future city of Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

), which, unknown to him, had been explored only ten weeks earlier by John Murray aboard . Flinders scaled Arthur's Seat, the highest point near the shores of the southernmost parts of the bay, and wrote that the land had "a pleasing and, in many parts, a fertile appearance". After scaling the You Yangs to the northwest of Port Phillip on 1 May, he left a scroll of paper with the ship's name on it and deposited it in a small pile of stones at the top of the peak.

With stores running low, Flinders proceeded to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

, arriving on 9 May 1802.

Circumnavigation of Australia

Flinders spent 12 weeks in Sydney resupplying and enlisting further crew for the continuation of the expedition to the northern coast of Australia. Bungaree, an Aboriginal man who had accompanied him on his earlier coastal survey in 1799, joined the expedition as did another local Aboriginal man named Nanbaree. It was arranged that Captain John Murray and his vessel the ''Lady Nelson'' would accompany the ''Investigator'' as a supply ship on this voyage. Flinders set sail again on 22 July 1802, heading north and surveying the coast of what would later be calledQueensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

. They soon anchored at Sandy Cape

Sandy Cape (also known by the Indigenous name of Woakoh) is the most northern point on Fraser Island (also known as K'gari and Gari) off the coast of Queensland, Australia. The place was named ''Sandy Cape'' for its appearance by James Cook dur ...

where, with Bungaree acting as a mediator, they feasted on porpoise blubber with a group of Batjala

The Butchulla, also written Butchella, Badjala, Badjula, Badjela, Bajellah, Badtjala and Budjilla are an Aboriginal Australian people of K'gari, Queensland, and a small area of the nearby mainland of southern Queensland.

Language

The Butchulla ...

people. In early August, Flinders sailed into a bay he named Port Curtis

Port Curtis is a suburb of Rockhampton in the Rockhampton Region, Queensland, Australia. In the , Port Curtis had a population of 281 people.

Geography

The Fitzroy River bounds the suburb to the north-east. Gavial Creek, a tributary of th ...

. Here the local people threw stones at them as they attempted to land. Flinders ordered muskets be fired above their heads to disperse them. The expedition continued north but navigation became increasingly difficult as they entered the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, A ...

. The ''Lady Nelson'' was deemed too unseaworthy to continue, and Captain Murray sailed her back to Sydney with his crew and Nanbaree, who wanted to return home. Flinders exited the reefs near to the Whitsunday Islands and sailed ''Investigator'' north to the Torres Strait. On 29 October, they arrived at Murray Island in the east of this strait, where they traded iron for shell necklaces with the local people.

The expedition entered the Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria (, ) is a large, shallow sea enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea (the body of water that lies between Australia and New Guinea). The northern boundary i ...

on 4 November and charted the coast to Arnhem Land. At Blue Mud Bay the crew, while collecting timber, had a skirmish with local Aboriginal men. One of the crew received four spear wounds while two of the Aboriginal men were shot dead. At nearby Caledon Bay, Flinders took a 14-year-old boy named Woga captive in order to coerce the local people to return a stolen axe. Although the axe was not returned, Flinders released the boy who had spent a day tied to a tree. On 17 February 1803, near Cape Wilberforce, the expedition encountered a Makassan

Makassar (, mak, ᨆᨀᨔᨑ, Mangkasara’, ) is the capital of the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, Surabaya, Medan ...

trepanging fleet captained by a man called Pobasso, from whom Flinders obtained information about the region.

During this part of the voyage, much of the ''Investigator'' was discovered to be rotten, and Flinders made the decision to complete the circumnavigation of the continent without any further close surveying of the coast. He sailed to Sydney via Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western part. The Indonesian part, ...

and the western and southern coasts of Australia. On the way, Flinders jettisoned two wrought-iron anchors which were found by divers in 1973 at Middle Island, Recherche Archipelago, Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

. The anchors are on display at the South Australian Maritime Museum

The South Australian Maritime Museum is a state government museum, part of the History Trust of South Australia. The Museum opened in 1986 in a collection of historic buildings in the heart of Port Adelaide, South Australia's first heritage pre ...

and at the National Museum of Australia.

Arriving in Sydney on 9 June 1803, ''Investigator'' was judged to be unseaworthy and condemned.

Attempted return to England and imprisonment

Unable to find another vessel suitable to continue his exploration, Flinders set sail for Britain as a passenger aboard . However, the ship was wrecked onWreck Reefs

The Wreck Reefs are located in the southern part of the Coral Sea Islands approximately east-north-east of Gladstone, Queensland, Australia.

Approximately east of the Swain Reefs complex they form a narrow chain of reefs with small cays that ...

, part of the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, A ...

, approximately north of Sydney. Flinders navigated the ship's cutter across open sea back to Sydney, and arranged for the rescue of the remaining marooned crew. Flinders then took command of the 29-ton schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

in order to return to England, but the poor condition of the vessel forced him to put in at French-controlled Isle de France (now known as Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

) for repairs on 17 December 1803, just three months after Baudin had died there.

War with France had broken out again the previous May, but Flinders hoped his French passport (despite its being issued for ''Investigator'' and not ''Cumberland'') and the scientific nature of his mission would allow him to continue on his way.

Despite this, and the knowledge of Baudin's earlier encounter with Flinders, the French governor, Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen

Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen (, 13 April 1769 – 9 September 1832) was a French general who served during the French Revolutionary Wars, as Governor General of Pondicherry and the Isle de France (now Mauritius) and as commander of the Army ...

, detained Flinders. The relationship between the men soured: Flinders was affronted at his treatment, and Decaen insulted by Flinders' refusal of an invitation to dine with him and his wife. Decaen was suspicious of the alleged scientific mission as the Cumberland carried no scientists and Decaen's search of Flinders' vessel uncovered a trunk full of papers (including despatches from the New South Wales Governor Philip Gidley King

Captain Philip Gidley King (23 April 1758 – 3 September 1808) was a British politician who was the third Governor of New South Wales.

When the First Fleet arrived in January 1788, King was detailed to colonise Norfolk Island for defence ...

) that were not permitted under his scientific passport. Furthermore, one of King's despatches was specifically to the British Admiralty requesting more troops in case Decaen were to attack Port Jackson. Among the papers seized were the three logs of of which only Volume one and Volume two were returned to Flinders; these are now both held by the State Library of New South Wales. The third volume was later deposited in the Admiralty Library and is now held in The National Archives (United Kingdom)

, type = Non-ministerial department

, seal =

, nativename =

, logo = Logo_of_The_National_Archives_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg

, logo_width = 150px

, logo_caption =

, formed =

, preceding1 =

, dissolved =

, superseding =

, juri ...

.

Decaen referred the matter to the French government; this was delayed not only by the long voyage but also by the general confusion of war. Eventually, on 11 March 1806, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

gave his approval, but Decaen still refused to allow Flinders' release. By this stage Decaen believed Flinders' knowledge of the island's defences would have encouraged Britain to attempt to capture it. Nevertheless, in June 1809 the Royal Navy began a blockade of the island, and in June 1810 Flinders was paroled

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

. Travelling via the Cape of Good Hope on , which was taking despatches back to Britain, he received a promotion to post-captain, before continuing to England.

Flinders had been confined for the first few months of his captivity, but he was later afforded greater freedom to move around the island and access his papers. In November 1804 he sent the first map of the landmass he had charted (Y46/1) back to England. This was the only map made by Flinders where he used the name "Australia or Terra Australis" for the title instead of New Holland the name of the continent that James Cook had used in 1770 and Abel Tasman had coined a Dutch version of in 1644, and the first known time he used the word Australia. He used the name New Holland on his map only for the western part of the continent. Due to the delay caused by his lengthy confinement, the first published map of the Australian continent was the Freycinet Map of 1811, a product of the Baudin expedition, issued in 1811.

Flinders finally returned to England in October 1810. He was in poor health but immediately resumed work preparing ''A Voyage to Terra Australis

''A Voyage to Terra Australis: Undertaken for the Purpose of Completing the Discovery of that Vast Country, and Prosecuted in the Years 1801, 1802, and 1803, in His Majesty's Ship the Investigator'' was a sea voyage journal written by English mari ...

'' and his atlas of maps for publication. The full title of this book, which was first published in London in July 1814, was given, as was common at the time, a synoptic description: ''A Voyage to Terra Australis: undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802, and 1803 in His Majesty's ship the'' Investigator, ''and subsequently in the armed vessel'' Porpoise ''and'' Cumberland Schooner. ''With an account of the shipwreck of the ''Porpoise'', arrival of the ''Cumberland'' at Mauritius, and imprisonment of the commander during six years and a half in that island'' . Original copies of the ''Atlas to Flinders' Voyage to Terra Australis'' are held at the Mitchell Library in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

as a portfolio that accompanied the book and included engravings of 16 maps, four plates of views and ten plates of Australian flora. The book was republished in three volumes in 1964, accompanied by a reproduction of the portfolio. Flinders' map of ''Terra Australis or Australia'' (so the two parts of the double name of his 1804 manuscript reversed) was first published in January 1814 and the remaining maps were published before his atlas and book.

Death and reburial

Flinders died, aged 40, on 19 July 1814 fromkidney disease

Kidney disease, or renal disease, technically referred to as nephropathy, is damage to or disease of a kidney. Nephritis is an inflammatory kidney disease and has several types according to the location of the inflammation. Inflammation can ...

, at his London home at 14 London Street, later renamed Maple Street and now the site of the BT Tower. This was on the day after the book and atlas was published; Flinders never saw the completed work as he was unconscious by that time, but his wife arranged the volumes on his bed covers so that he could touch them. On 23 July he was interred in the burial ground of St James's Church, Piccadilly, which was located some distance from the church, beside Hampstead Road, Camden, London. The burial ground was in use from 1790 until 1853. By 1852 the location of the grave had been forgotten due to alterations to the burial ground.

In 1878 the cemetery became St James's Gardens, Camden, with only a few gravestones lining the edges of the park. Part of the gardens, located between Hampstead Road and Euston railway station, was built over when Euston station was expanded, and Flinders' grave was thought to possibly lie under a station platform.Miranda, C.Skeleton of renowned explorer Matthew Flinders is lying in the path of London rail link — and could be exhumed

News Limited Network, 28 February 2014. Accessed 13 April 2014. The Gardens were closed to the public in 2017 for work on the High Speed 2 (HS2) rail project which requires the expansion of Euston station. The grave was located in January 2019 by archaeologists. His coffin was identified by its well-preserved lead coffin plate. Film of the discovery and the exhumation was shown in a documentary on British television in September 2020. It was proposed to re-bury his remains, at a site to be decided, after they had been examined by osteo-archaeologists.

Following the discovery of his grave the parish church of Donington, Lincolnshire, Flinders' birthplace, saw a surge of visitors. The 'Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home Group' and the Britain-Australia Society, as well as Flinders' direct descendants, campaigned to have his remains interred at the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood in Donington. On 17 October 2019 HS2 Ltd announced that Flinders remains could be reinterred in the church in Donington, where he was baptised. Permission has been given by the Diocese of Lincoln for reburial in the north aisle.

Following the discovery of his grave the parish church of Donington, Lincolnshire, Flinders' birthplace, saw a surge of visitors. The 'Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home Group' and the Britain-Australia Society, as well as Flinders' direct descendants, campaigned to have his remains interred at the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood in Donington. On 17 October 2019 HS2 Ltd announced that Flinders remains could be reinterred in the church in Donington, where he was baptised. Permission has been given by the Diocese of Lincoln for reburial in the north aisle.

Family

On 17 April 1801, Flinders married his longstanding friend Ann Chappelle (1772–1852) and had hoped to take her with him to Port Jackson. However, the Admiralty had strict rules against wives accompanying captains. Flinders brought Ann on board ship and planned to ignore the rules, but the Admiralty learned of his plans and reprimanded him for his bad judgement, and ordered him to remove her from the ship. This is well documented in correspondence between Flinders and his chief benefactor, Sir Joseph Banks, in May 1801: As a result, Ann was obliged to stay in England and would not see her husband for nine years, following his imprisonment on the Isle de France (Mauritius, at the time a French possession) on his return journey. When they finally reunited, Matthew and Ann had one daughter, Anne, (1 April 1812 – 1892), who later marriedWilliam Petrie

William Petrie (1747 – 27 October 1816) was a British officer of the East India Company in Chennai (formerly Madras) during the 1780s, and was Governor of Prince of Wales Island (Penang Island) from 1812 to 1816. An amateur astronomer, Petrie he ...

(1821–1908). In 1853, the governments of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

and Victoria bequeathed a belated pension to her (deceased) mother of £100 per year, to go to surviving issue of the union. This she accepted on behalf of her young son, William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who would go on to become an accomplished archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

and Egyptologist.

Naming of Australia and discovery of Flinders' 1804 map Y46/1

Flinders' map Y46/1 was never "lost". It had been stored and recorded by the

Flinders' map Y46/1 was never "lost". It had been stored and recorded by the UK Hydrographic Office

The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) is the UK's agency for providing hydrographic and marine geospatial data to mariners and maritime organisations across the world. The UKHO is a trading fund of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and is l ...

before 1828. Geoffrey C. Ingleton mentioned Y46/1 in his book ''Matthew Flinders Navigator and Chartmaker'' on page 438. By 1987 every library in Australia had access to a microfiche copy of Flinders Y46/1. In 2001–2002 the Mitchell Library Sydney displayed Y46/1 at their "Matthew Flinders – The Ultimate Voyage" exhibition. Paul Brunton called Y46/1 "the memorial of the great naval explorer Matthew Flinders". The first hard-copy of Y46/1 and its cartouche was retrieved from the UK Hydrographic Office ( Taunton, Somerset) by historian Bill Fairbanks in 2004. On 2 April 2004, copies of the chart were presented by three of Matthew Flinders's descendants to the Governor of New South Wales, in London, to be presented in turn to the people of Australia through their parliaments by 14 November, the 200th anniversary of the chart leaving Mauritius. This celebration marked the first time the naming of Australia was formally recognised.

Flinders was not the first to use the word "Australia", nor was he the first to apply the name specifically to the continent. He owned a copy of Alexander Dalrymple's 1771 book ''An Historical Collection of Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean'', and it seems likely he borrowed it from there, but he applied it specifically to the continent, not the whole South Pacific region. In 1804 he wrote to his brother: "I call the whole island Australia, or Terra Australis". Later that year, he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks and mentioned "my general chart of Australia", a map that Flinders had constructed from all the information he had accumulated while he was in Australian waters and finished while he was detained by the French in Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

. Flinders explained in his letter to Banks:

Flinders continued to promote the use of the word until his arrival in London in 1810. Here he found that Banks did not approve of the name and had not unpacked the chart he had sent him, and that "New Holland" and "Terra Australis" were still in general use. As a result, a book by Flinders was published under the title ''A Voyage to Terra Australis

''A Voyage to Terra Australis: Undertaken for the Purpose of Completing the Discovery of that Vast Country, and Prosecuted in the Years 1801, 1802, and 1803, in His Majesty's Ship the Investigator'' was a sea voyage journal written by English mari ...

'' and his published map of 1814 also shows 'Terra Australis' as the first of the two name options, despite his objections. The final proofs were brought to him on his deathbed, but he was unconscious. The book was published on 18 July 1814, but Flinders did not regain consciousness and died the next day, never knowing that his name for the continent would be accepted.''The Weekend Australian'', 30 – 31 December 2000, p. 16

Banks wrote a draft of an introduction to Flinders' ''Voyage'', referring to the map published by Melchisédech Thévenot in ''Relations des Divers Voyages'' (1663), and made well known to English readers by Emanuel Bowen's adaptation of it, ''A Complete Map of the Southern Continent'', published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris's ''Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels'' (1744–48, and 1764). Banks said in the draft:

Although Thévenot said that he had taken his chart from the one inlaid into the floor of the Amsterdam Town Hall, in fact it appears to be an almost exact copy of that of

Banks wrote a draft of an introduction to Flinders' ''Voyage'', referring to the map published by Melchisédech Thévenot in ''Relations des Divers Voyages'' (1663), and made well known to English readers by Emanuel Bowen's adaptation of it, ''A Complete Map of the Southern Continent'', published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris's ''Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels'' (1744–48, and 1764). Banks said in the draft:

Although Thévenot said that he had taken his chart from the one inlaid into the floor of the Amsterdam Town Hall, in fact it appears to be an almost exact copy of that of Joan Blaeu

Joan Blaeu (; 23 September 1596 – 21 December 1673) was a Dutch cartographer born in Alkmaar, the son of cartographer Willem Blaeu.

Life

In 1620, Blaeu became a doctor of law but he joined the work of his father. In 1635, they published ...

in his ''Archipelagus Orientalis sive Asiaticus'' published in 1659. It seems to have been Thévenot who introduced a differentiation between ''Nova Hollandia'' to the west and ''Terre Australe'' to the east of the meridian corresponding to 135° East of Greenwich, emphasised by the latitude staff running down that meridian, as there is no such division on Blaeu's map.

In his ''Voyage'', Flinders wrote:

...with the accompanying note at the bottom of the page:

So Flinders had concluded that the Terra Australis, as hypothesised by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(which would be discovered as Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

less than six years later) did not exist; therefore he wanted the name applied to the continent of Australia, and it stuck.

Flinders' book was widely read and gave the term "Australia" general currency. Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, became aware of Flinders' preference for the name Australia and used it in his dispatches to England. On 12 December 1817, he recommended to the Colonial Office that it be officially adopted. In 1824 the British Admiralty agreed that the continent should be known officially as Australia.

Legacy of Flinders

Although he never used his own name for any feature in all his discoveries, Flinders' name is now associated with over 100 geographical features and places in Australia,The intrepid spirit of Matthew Flinders lives on in more than 100 Australian sites

Although he never used his own name for any feature in all his discoveries, Flinders' name is now associated with over 100 geographical features and places in Australia,The intrepid spirit of Matthew Flinders lives on in more than 100 Australian sites''ABC News'', 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019. including Flinders Island in Bass Strait, but not Flinders Island in South Australia, which he named for his younger brother, Samuel Flinders. Flinders is seen as being particularly important in South Australia, where he is considered the main explorer of the state. Landmarks named after him in South Australia include the Flinders Ranges and

Flinders Ranges National Park

Flinders may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Flinders Peak, near the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula

Australia New South Wales

* Flinders County, New South Wales

* Shellharbour Junction railway station, Shellharbour

* Flinders, New South ...

, Flinders Column at Mount Lofty, Flinders Chase National Park on Kangaroo Island, Flinders University, Flinders Medical Centre, the suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a larger city/urban area or as a separ ...

Flinders Park and Flinders Street in Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. In Victoria, eponymous places include Flinders Peak

Flinders Peak () is a conspicuous triangular peak, high, on the west end of the Bristly Peaks. The peak overlooks Forster Ice Piedmont near the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was photographed from the air by the British Graham Land E ...

, Flinders Street in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

, the suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a larger city/urban area or as a separ ...

of Flinders, the federal electorate of Flinders, and the Matthew Flinders Girls Secondary College

Matthew Flinders Girls' Secondary College is an all-girls State secondary school located in Geelong, Victoria, Australia. It provides education for students years 7-12.

History

The school opened as Flinders National Grammar School in January 1 ...

in Geelong.

Flinders Bay

Flinders Bay is a bay and locality that is immediately south of the townsite of Augusta, and close to the mouth of the Blackwood River.

The locality and bay lies to the north east of Cape Leeuwin which is the most south-westerly mainland poi ...

in Western Australia and Flinders Way in Canberra also commemorate him. Educational institutions named after him include Flinders Park Primary School in South Australia, and Matthew Flinders Anglican College on the Sunshine Coast Sunshine Coast may refer to:

* Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia

**Sunshine Coast Region, a local government area of Queensland named after the region

**Sunshine Coast Stadium

* Sunshine Coast (British Columbia), geographic subregion of the Br ...

in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

. A former electoral district of the Queensland Parliament was named Flinders. There are also Flinders Highways in both Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

.

Bass & Flinders Point in the southernmost part of Cronulla in New South Wales features a monument to George Bass and Matthew Flinders, who explored the Port Hacking estuary.

Australia holds a large collection of statues erected in Flinders' honour. In his native England, the first statue of Flinders was erected on 16 March 2006 (his birthday) in his hometown of Donington. The statue also depicts his beloved cat Trim

Trim or TRIM may refer to:

Cutting

* Cutting or trimming small pieces off something to remove them

** Book trimming, a stage of the publishing process

** Pruning, trimming as a form of pruning often used on trees

Decoration

* Trim (sewing), ...

, who accompanied him on his voyages. In July 2014, on the 200-year anniversary of his death, a large bronze statue of Flinders by the sculptor Mark Richards was unveiled at Australia House, London by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and later installed at Euston station near the presumed location of his grave.

Flinders' proposal for the use of iron bars to be used to compensate for the magnetic deviations caused by iron on board a ship resulted in their being known as Flinders bars.

Flinders coined the term " dodge tide" in reference to his observations that the tides in the very shallow Spencer and St Vincent's Gulfs seemed to be completely inert for several days, at select locations. Such phenomena have now also been found in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

and in the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the C ...

.''Once Again – Tidal Friction'', W. Munk, Qtly J. Ryl Astron Soc, Vol. 9, p. 352, 1968.

Flinders, who was Sir John Franklin's cousin by marriage, John's mother Hannah being the sister of Matthew's step mother Elizabeth, instilled in him a love for navigating and took him with him on his voyage aboard ''Investigator''.

In 1964 he was honoured on a postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the f ...

issued by Postmaster-General's Department, again in 1980, and in 1998 with George Bass.

'' Flindersia'' is a genus of fourteen species of tree in the citrus family; it was named by ''Investigator''s botanist, Robert Brown in honour of Flinders. The eastern school whiting, ''Sillago flindersi'' is named after him.

Flinders landed on Coochiemudlo Island

Coochiemudlo Island is a small island in the southern part of Moreton Bay, near Brisbane, in South East Queensland, Australia. It is also the name of the locality upon the island, which is within the local government area of Redland City.

In th ...

on 19 July 1799, while he was searching for a river in the southern part of Moreton Bay, Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, Australia. The island's residents celebrate Flinders Day annually, commemorating the landing. The celebrations are usually held on a weekend near 19 July, the actual date of the landing.

Flinder's explorations of the Hervey Bay area are commemorated by a monument called Matthew Flinders Lookout at the top of an escarpment facing the bay in Dayman Park, Urangan ().

Flinder's Memorial in Maconde, Mauritius - The Captain Flinders Memorial is a stone memorial located close to Macondé, Mauritius on the ocean's edge. The memorial is located close to where Captain Flinders landed on the 17th December 1803, whilst commanding HMS Cumberland. The memorial has a brass plaque with the title "Captain Matthew Flinders RN 1774 - 1814, Explorer, Navigator and Hydrographer. The details show Captain Flinders, sitting at his desk with a map showing the Indian Ocean and Australia.

At the bottom of the monument, the plaque describes the unveiling on 6 November 2003. "This monument was unveiled by HRH The Earl of Wessex KCVO in the presence of the president of the republic of Mauritius, Sir Anerood Jugnauth PC, KCMG, QC on November 6th 2003 to commemorate the bicentennary of the arrival in Mauritius of Captain Matthew Flinders on 15 December 1803"

Works

* ''A Voyage to Terra Australis, with an accompanying Atlas''. 2 vol. – London : G & W Nicol, 18 July 1814 * ''Australia Circumnavigated: The Journal of HMS Investigator, 1801–1803''. Edited by Kenneth Morgan, 2 vols, The Hakluyt Society, London, 201* ''Trim: Being the True Story of a Brave Seafaring Cat''. * ''Private Journal 1803–1814''. Edited with an introduction by Anthony J. Brown and Gillian Dooley. Friends of the State Library of South Australia, 2005. * *

See also

* European and American voyages of scientific exploration * Flinders bar * List of explorers *Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture The Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture of the Australian Academy of Science is awarded biennially to recognise exceptional research by Australian scientists in the physical sciences. Nominations can only be made by Academy Fellows.

Recipients

Sourc ...

* '' Matthew Flinders' Cat'', a novel by Bryce Courtenay

Arthur Bryce Courtenay, (14 August 1933 – 22 November 2012) was a South African-Australian advertising director and novelist. He is one of Australia's best-selling authors, notable for his book '' The Power of One''.

Background and early ye ...

(2002)

* Trim (cat)

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Tugdual de Langlais, ''Marie-Etienne Peltier, Capitaine corsaire de la République'', Éd. Coiffard, 2017, 240 p. (). * * *External links

Flinders, Matthew (1774–1814)

National Library of Australia, ''Trove, People and Organisation'' record for Matthew Flinders

at the State Library of New South Wales.

The Flinders Papers

an

Charts by Matthew Flinders

at the UK National Maritime Museum *

Works by Matthew Flinders

at Project Gutenberg Australia *

Flinders Providence Logbook

Naming of Australia

Matthew Flinders' map of Australia

High resolution image of the complete map.

Flinders' Journeys – State Library of NSW

Biography at BBC Radio Lincolnshire

Voyages of Captain Matthew Flinders in Australia

Google Earth Virtual Tour

at the

British Atmospheric Data Centre

A Voyage to Terra Australis, Volume 1

– National Museum of Australia * Matthew Flinders: Placing Australia on the map

at the State Library of New South Wales {{DEFAULTSORT:Flinders, Matthew Royal Navy officers English explorers English sailors English cartographers English hydrographers Explorers of Australia Explorers of Western Australia Explorers of Queensland Explorers of South Australia Hydrographers People from Donington, Lincolnshire 1774 births 1814 deaths Maritime exploration of Australia Maritime writers Articles containing video clips Pre-Separation Queensland Sea captains 2019 archaeological discoveries English navigators Royal Navy sailors