Mary Wollstonecraft on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

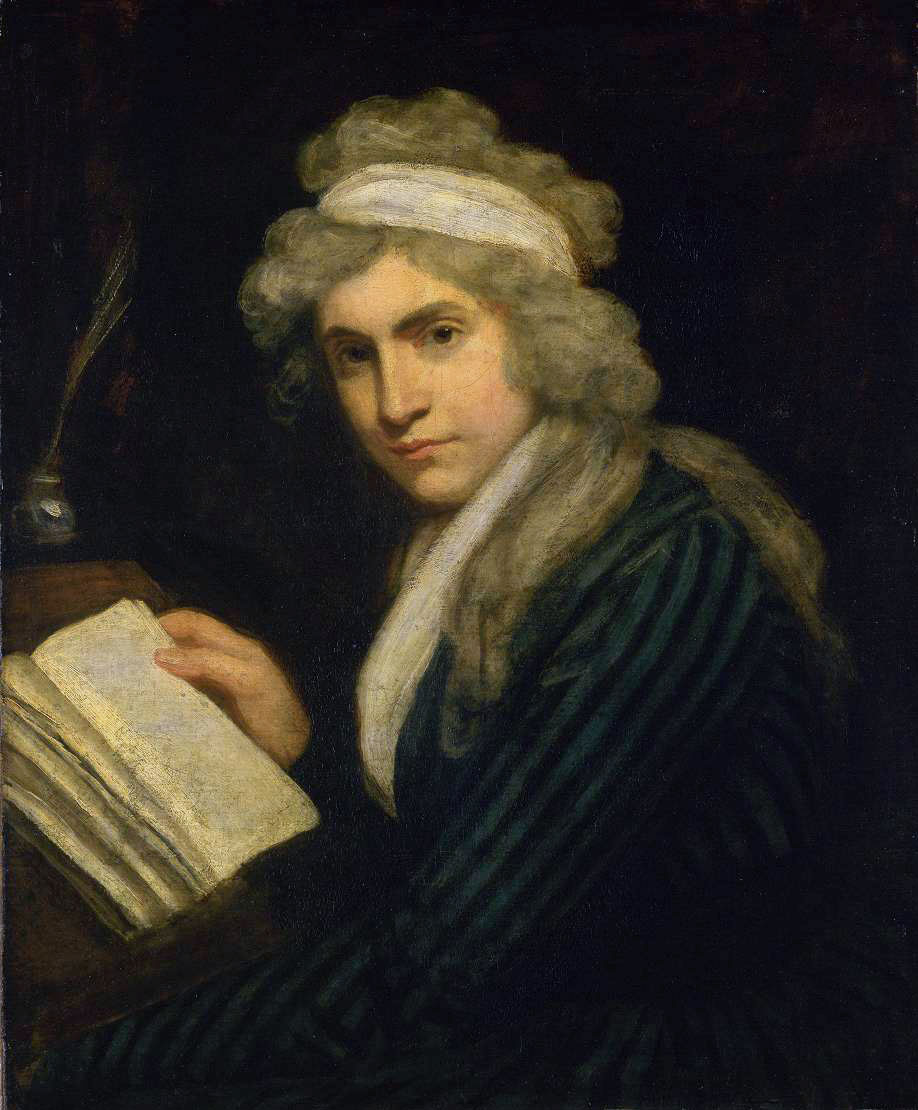

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of

After Blood's death in 1785, Wollstonecraft's friends helped her obtain a position as governess to the daughters of the Anglo-Irish Kingsborough family in Ireland. Although she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough, the children found her an inspiring instructor; one of the daughters,

After Blood's death in 1785, Wollstonecraft's friends helped her obtain a position as governess to the daughters of the Anglo-Irish Kingsborough family in Ireland. Although she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough, the children found her an inspiring instructor; one of the daughters,

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December 1792 and arrived about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined. Britain and France were on the brink of war when she left for Paris, and many advised her not to go. France was in turmoil. She sought out other British visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the circle of expatriates then in the city. During her time in Paris, Wollstonecraft associated mostly with the moderate Girondins rather than the more radical

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December 1792 and arrived about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined. Britain and France were on the brink of war when she left for Paris, and many advised her not to go. France was in turmoil. She sought out other British visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the circle of expatriates then in the city. During her time in Paris, Wollstonecraft associated mostly with the moderate Girondins rather than the more radical

She then went out on a rainy night and "to make her clothes heavy with water, she walked up and down about half an hour" before jumping into the

She then went out on a rainy night and "to make her clothes heavy with water, she walked up and down about half an hour" before jumping into the

On 30 August 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter,

On 30 August 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter,

:Hard was thy fate in all the scenes of life

:As daughter, sister, mother, friend, and wife;

:But harder still, thy fate in death we own,

:Thus mourn'd by Godwin with a heart of stone.

In 1851, Wollstonecraft's remains were moved by her grandson Percy Florence Shelley to his family tomb in St Peter's Church, Bournemouth.

Wollstonecraft has what scholar Cora Kaplan labelled in 2002 a 'curious' legacy that has evolved over time: 'for an author-activist adept in many genres ... up until the last quarter-century Wollstonecraft's life has been read much more closely than her writing'. After the devastating effect of Godwin's ''Memoirs'', Wollstonecraft's reputation lay in tatters for nearly a century; she was pilloried by such writers as

Wollstonecraft has what scholar Cora Kaplan labelled in 2002 a 'curious' legacy that has evolved over time: 'for an author-activist adept in many genres ... up until the last quarter-century Wollstonecraft's life has been read much more closely than her writing'. After the devastating effect of Godwin's ''Memoirs'', Wollstonecraft's reputation lay in tatters for nearly a century; she was pilloried by such writers as

Full text.

/ref> In contrast, there was one writer of the generation after Wollstonecraft who apparently did not share the judgmental views of her contemporaries. Jane Austen never mentioned the earlier woman by name, but several of her novels contain positive allusions to Wollstonecraft's work.Mellor 156. The American literary scholar Anne K. Mellor notes several examples. In '' Pride and Prejudice'', Mr Wickham seems to be based upon the sort of man Wollstonecraft claimed that standing armies produce, while the sarcastic remarks of protagonist With the emergence of

With the emergence of

The majority of Wollstonecraft's early productions are about education; she assembled an anthology of literary extracts "for the improvement of young women" entitled ''The Female Reader'' and she translated two children's works, Maria Geertruida van de Werken de Cambon's ''Young Grandison'' and Christian Gotthilf Salzmann's ''Elements of Morality''. Her own writings also addressed the topic. In both her conduct book ''Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'' (1787) and her children's book ''Original Stories from Real Life'' (1788), Wollstonecraft advocates educating children into the emerging middle-class ethos: self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and social contentment. Both books also emphasise the importance of teaching children to reason, revealing Wollstonecraft's intellectual debt to the educational views of seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke. However, the prominence she affords religious faith and innate feeling distinguishes her work from his and links it to the discourse of sensibility popular at the end of the eighteenth century. Both texts also advocate the education of women, a controversial topic at the time and one which she would return to throughout her career, most notably in ''

The majority of Wollstonecraft's early productions are about education; she assembled an anthology of literary extracts "for the improvement of young women" entitled ''The Female Reader'' and she translated two children's works, Maria Geertruida van de Werken de Cambon's ''Young Grandison'' and Christian Gotthilf Salzmann's ''Elements of Morality''. Her own writings also addressed the topic. In both her conduct book ''Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'' (1787) and her children's book ''Original Stories from Real Life'' (1788), Wollstonecraft advocates educating children into the emerging middle-class ethos: self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and social contentment. Both books also emphasise the importance of teaching children to reason, revealing Wollstonecraft's intellectual debt to the educational views of seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke. However, the prominence she affords religious faith and innate feeling distinguishes her work from his and links it to the discourse of sensibility popular at the end of the eighteenth century. Both texts also advocate the education of women, a controversial topic at the time and one which she would return to throughout her career, most notably in ''

Marie_Antoinette.html" ;"title="/nowiki> Marie Antoinette">/nowiki> Marie Antoinette/nowiki> with insult.—But the age of chivalry is gone." Most of Burke's detractors deplored what they viewed as theatrical pity for the French queen—a pity they felt was at the expense of the people. Wollstonecraft was unique in her attack on Burke's gendered language. By redefining the sublime and the beautiful, terms first established by Burke himself in ''

Wollstonecraft states that currently many women are silly and superficial (she refers to them, for example, as "spaniels" and "toys"), but argues that this is not because of an innate deficiency of mind but rather because men have denied them access to education. Wollstonecraft is intent on illustrating the limitations that women's deficient educations have placed on them; she writes: "Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison." She implies that, without the encouragement young women receive from an early age to focus their attention on beauty and outward accomplishments, women could achieve much more.

While Wollstonecraft does call for equality between the sexes in particular areas of life, such as morality, she does not explicitly state that men and women are equal. What she does claim is that men and women are equal in the eyes of God. However, such claims of equality stand in contrast to her statements respecting the superiority of masculine strength and valour. Wollstonecraft famously and ambiguously writes: "Let it not be concluded that I wish to invert the order of things; I have already granted, that, from the constitution of their bodies, men seem to be designed by Providence to attain a greater degree of virtue. I speak collectively of the whole sex; but I see not the shadow of a reason to conclude that their virtues should differ in respect to their nature. In fact, how can they, if virtue has only one eternal standard? I must therefore, if I reason consequently, as strenuously maintain that they have the same simple direction, as that there is a God." Her ambiguous statements regarding the equality of the sexes have since made it difficult to classify Wollstonecraft as a modern feminist, particularly since the word did not come into existence until the 1890s.

One of Wollstonecraft's most scathing critiques in the ''Rights of Woman'' is of false and excessive sensibility, particularly in women. She argues that women who succumb to sensibility are "blown about by every momentary gust of feeling" and because they are "the prey of their senses" they cannot think rationally. In fact, she claims, they do harm not only to themselves but to the entire civilisation: these are not women who can help refine a civilisation—a popular eighteenth-century idea—but women who will destroy it. Wollstonecraft does not argue that reason and feeling should act independently of each other; rather, she believes that they should inform each other.

In addition to her larger philosophical arguments, Wollstonecraft also lays out a specific educational plan. In the twelfth chapter of the ''Rights of Woman'', "On National Education", she argues that all children should be sent to a "country day school" as well as given some education at home "to inspire a love of home and domestic pleasures." She also maintains that schooling should be

Wollstonecraft states that currently many women are silly and superficial (she refers to them, for example, as "spaniels" and "toys"), but argues that this is not because of an innate deficiency of mind but rather because men have denied them access to education. Wollstonecraft is intent on illustrating the limitations that women's deficient educations have placed on them; she writes: "Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison." She implies that, without the encouragement young women receive from an early age to focus their attention on beauty and outward accomplishments, women could achieve much more.

While Wollstonecraft does call for equality between the sexes in particular areas of life, such as morality, she does not explicitly state that men and women are equal. What she does claim is that men and women are equal in the eyes of God. However, such claims of equality stand in contrast to her statements respecting the superiority of masculine strength and valour. Wollstonecraft famously and ambiguously writes: "Let it not be concluded that I wish to invert the order of things; I have already granted, that, from the constitution of their bodies, men seem to be designed by Providence to attain a greater degree of virtue. I speak collectively of the whole sex; but I see not the shadow of a reason to conclude that their virtues should differ in respect to their nature. In fact, how can they, if virtue has only one eternal standard? I must therefore, if I reason consequently, as strenuously maintain that they have the same simple direction, as that there is a God." Her ambiguous statements regarding the equality of the sexes have since made it difficult to classify Wollstonecraft as a modern feminist, particularly since the word did not come into existence until the 1890s.

One of Wollstonecraft's most scathing critiques in the ''Rights of Woman'' is of false and excessive sensibility, particularly in women. She argues that women who succumb to sensibility are "blown about by every momentary gust of feeling" and because they are "the prey of their senses" they cannot think rationally. In fact, she claims, they do harm not only to themselves but to the entire civilisation: these are not women who can help refine a civilisation—a popular eighteenth-century idea—but women who will destroy it. Wollstonecraft does not argue that reason and feeling should act independently of each other; rather, she believes that they should inform each other.

In addition to her larger philosophical arguments, Wollstonecraft also lays out a specific educational plan. In the twelfth chapter of the ''Rights of Woman'', "On National Education", she argues that all children should be sent to a "country day school" as well as given some education at home "to inspire a love of home and domestic pleasures." She also maintains that schooling should be

Both of Wollstonecraft's novels criticise what she viewed as the patriarchal institution of marriage and its deleterious effects on women. In her first novel, ''Mary: A Fiction'' (1788), the eponymous heroine is forced into a loveless marriage for economic reasons; she fulfils her desire for love and affection outside marriage with two passionate

Both of Wollstonecraft's novels criticise what she viewed as the patriarchal institution of marriage and its deleterious effects on women. In her first novel, ''Mary: A Fiction'' (1788), the eponymous heroine is forced into a loveless marriage for economic reasons; she fulfils her desire for love and affection outside marriage with two passionate

Wollstonecraft promotes subjective experience, particularly in relation to nature, exploring the connections between the sublime and sensibility. Many of the letters describe the breathtaking scenery of Scandinavia and Wollstonecraft's desire to create an emotional connection to that natural world. In so doing, she gives greater value to the imagination than she had in previous works. As in her previous writings, she champions the liberation and education of women. In a change from her earlier works, however, she illustrates the detrimental effects of commerce on society, contrasting the imaginative connection to the world with a commercial and mercenary one, an attitude she associates with Imlay.

''Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark'' was Wollstonecraft's most popular book in the 1790s. It sold well and was reviewed positively by most critics. Godwin wrote "if ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book."Godwin, 95. It influenced Romantic poets such as

Wollstonecraft promotes subjective experience, particularly in relation to nature, exploring the connections between the sublime and sensibility. Many of the letters describe the breathtaking scenery of Scandinavia and Wollstonecraft's desire to create an emotional connection to that natural world. In so doing, she gives greater value to the imagination than she had in previous works. As in her previous writings, she champions the liberation and education of women. In a change from her earlier works, however, she illustrates the detrimental effects of commerce on society, contrasting the imaginative connection to the world with a commercial and mercenary one, an attitude she associates with Imlay.

''Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark'' was Wollstonecraft's most popular book in the 1790s. It sold well and was reviewed positively by most critics. Godwin wrote "if ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book."Godwin, 95. It influenced Romantic poets such as

''Mary Wollstonecraft: A Literary Life''

Springer, 2004. * Eleanor Flexner, Flexner, Eleanor. ''Mary Wollstonecraft: A Biography''. New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1972. . * William Godwin, Godwin, William.

Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman

'. 1798. Eds. Pamela Clemit and Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd., 2001. . * Charlotte Gordon, Gordon, Charlotte. ''Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley''. Great Britain: Random House, 2015.

The book's website.

* Lyndall Gordon, Gordon, Lyndall. ''Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft''. Great Britain: Virago, 2005. . * Mary Hays, Hays, Mary. "Memoirs of Mary Wollstonecraft". ''Annual Necrology'' (1797–98): 411–460. * Jacobs, Diane. ''Her Own Woman: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft''. US: Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Charles Kegan Paul, Paul, Charles Kegan. ''Letters to Imlay, with prefatory memoir by C. Kegan Paul''. London: C. Kegan Paul, 1879

Full text

* Pennell, Elizabeth Robins. ''Life of Mary Wollstonecraft'' (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1884)

Full text

* William St Clair, St Clair, William. ''The Godwins and the Shelleys: The biography of a family''. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1989. . * Emily W. Sunstein, Sunstein, Emily. ''A Different Face: the Life of Mary Wollstonecraft''. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1975. . * Janet Todd, Todd, Janet. ''Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life.'' London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000. . * Claire Tomalin, Tomalin, Claire. ''The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft''. Rev. ed. 1974. New York: Penguin, 1992. . * Wardle, Ralph M. ''Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1951.

Works

a

Open Library

Mary Wollstonecraft: A 'Speculative and Dissenting Spirit'

by Janet Todd at BBC History *

Mary Wollstonecraft manuscript material, 1773–1797

held by the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, New York Public Library * *

Exhibits relating to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wollstonecraft, Mary 1759 births 1797 deaths People from Spitalfields People from Somers Town, London 18th-century English novelists 18th-century British philosophers 18th-century British women writers 18th-century essayists Burials at St Pancras Old Church Deaths in childbirth Deaths from sepsis English governesses Schoolteachers from London Education writers 18th-century English historians English women novelists English travel writers English Unitarians English feminists English essayists English philosophers English women philosophers English feminist writers Enlightenment philosophers Feminist philosophers Feminist theorists French–English translators German–English translators Godwin family Historians of the French Revolution British women essayists British women travel writers British women historians British political activists Writers of Gothic fiction Founders of English schools and colleges English educational theorists English republicans Philosophers of education

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationships at the time, received more attention than her writing. Today Wollstonecraft is regarded as one of the founding feminist philosophers

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, and feminists often cite both her life and her works as important influences.

During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern period ...

, a history of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, a conduct book, and a children's book. Wollstonecraft is best known for ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

'' (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men, but appear to be only because they lack education. She suggests that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagines a social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order ...

founded on reason.

After Wollstonecraft's death, her widower published a ''Memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

'' (1798) of her life, revealing her unorthodox lifestyle, which inadvertently destroyed her reputation for almost a century. However, with the emergence of the feminist movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such ...

at the turn of the twentieth century, Wollstonecraft's advocacy of women's equality and critiques of conventional femininity became increasingly important.

After two ill-fated affairs, with Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli ( ; German: Johann Heinrich Füssli ; 7 February 1741 – 17 April 1825) was a Swiss painter, draughtsman and writer on art who spent much of his life in Britain. Many of his works, such as '' The Nightmare'', deal with supernatu ...

and Gilbert Imlay (by whom she had a daughter, Fanny Imlay

Frances Imlay (14 May 1794 – 9 October 1816), also known as Fanny Godwin and Frances Wollstonecraft, was the illegitimate daughter of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and the American commercial speculator and diplomat Gilbert Iml ...

), Wollstonecraft married the philosopher William Godwin, one of the forefathers of the anarchist movement. Wollstonecraft died at the age of 38 leaving behind several unfinished manuscripts. She died 11 days after giving birth to her second daughter, Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic novel '' Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' (1818), which is considered an early example of science fiction. She also ...

, who would become an accomplished writer and the author of ''Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific ...

''.

Biography

Early life

Wollstonecraft was born on 27 April 1759 in Spitalfields, London. She was the second of the seven children of Elizabeth Dixon and Edward John Wollstonecraft. Although her family had a comfortable income when she was a child, her father gradually squandered it on speculative projects. Consequently, the family became financially unstable and they were frequently forced to move during Wollstonecraft's youth. The family's financial situation eventually became so dire that Wollstonecraft's father compelled her to turn over money that she would have inherited at her maturity. Moreover, he was apparently a violent man who would beat his wife in drunken rages. As a teenager, Wollstonecraft used to lie outside the door of her mother's bedroom to protect her. Wollstonecraft played a similar maternal role for her sisters, Everina and Eliza, throughout her life. In a defining moment in 1784, she persuaded Eliza, who was suffering from what was probablypostpartum depression

Postpartum depression (PPD), also called postnatal depression, is a type of mood disorder associated with childbirth, which can affect both sexes. Symptoms may include extreme sadness, low energy, anxiety, crying episodes, irritability, and cha ...

, to leave her husband and infant; Wollstonecraft made all of the arrangements for Eliza to flee, demonstrating her willingness to challenge social norms. The human costs, however, were severe: her sister suffered social condemnation and, because she could not remarry, was doomed to a life of poverty and hard work.

Two friendships shaped Wollstonecraft's early life. The first was with Jane Arden in Beverley

Beverley is a market and minster town and a civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, of which it is the county town. The town centre is located south-east of York's centre and north-west of City of Hull.

The town is known fo ...

. The two frequently read books together and attended lectures presented by Arden's father, a self-styled philosopher and scientist. Wollstonecraft revelled in the intellectual atmosphere of the Arden household and valued her friendship with Arden greatly, sometimes to the point of being emotionally possessive. Wollstonecraft wrote to her: "I have formed romantic notions of friendship ... I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have the first place or none." In some of Wollstonecraft's letters to Arden, she reveals the volatile and depressive emotions that would haunt her throughout her life. The second and more important friendship was with Fanny (Frances) Blood, introduced to Wollstonecraft by the Clares, a couple in Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. As a part of Shoreditch, it is often considered to be part of the East End – the historic core of wider East London. It was historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. It li ...

who became parental figures to her; Wollstonecraft credited Blood with opening her mind.

Unhappy with her home life, Wollstonecraft struck out on her own in 1778 and accepted a job as a lady's companion

A lady's companion was a woman of genteel birth who lived with a woman of rank or wealth as retainer. The term was in use in the United Kingdom from at least the 18th century to the mid-20th century but it is now archaic. The profession is known ...

to Sarah Dawson, a widow living in Bath. However, Wollstonecraft had trouble getting along with the irascible woman (an experience she drew on when describing the drawbacks of such a position in '' Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'', 1787). In 1780 she returned home upon being called back to care for her dying mother. Rather than return to Dawson's employ after the death of her mother, Wollstonecraft moved in with the Bloods. She realised during the two years she spent with the family that she had idealised Blood, who was more invested in traditional feminine values than was Wollstonecraft. But Wollstonecraft remained dedicated to Fanny and her family throughout her life, frequently giving pecuniary assistance to Blood's brother.

Wollstonecraft had envisioned living in a female utopia with Blood; they made plans to rent rooms together and support each other emotionally and financially, but this dream collapsed under economic realities. In order to make a living, Wollstonecraft, her sisters and Blood set up a school together in Newington Green

Newington Green is an open space in North London that straddles the border between Islington and Hackney. It gives its name to the surrounding area, roughly bounded by Ball's Pond Road to the south, Petherton Road to the west, Green Lanes and ...

, a Dissenting

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

community. Blood soon became engaged and, after her marriage, moved to Lisbon Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

with her husband, Hugh Skeys, in hopes that it would improve her health which had always been precarious. Despite the change of surroundings Blood's health further deteriorated when she became pregnant, and in 1785 Wollstonecraft left the school and followed Blood to nurse her, but to no avail. Moreover, her abandonment of the school led to its failure. Blood's death devastated Wollstonecraft and was part of the inspiration for her first novel, '' Mary: A Fiction'' (1788).

'The first of a new genus'

After Blood's death in 1785, Wollstonecraft's friends helped her obtain a position as governess to the daughters of the Anglo-Irish Kingsborough family in Ireland. Although she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough, the children found her an inspiring instructor; one of the daughters,

After Blood's death in 1785, Wollstonecraft's friends helped her obtain a position as governess to the daughters of the Anglo-Irish Kingsborough family in Ireland. Although she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough, the children found her an inspiring instructor; one of the daughters, Margaret King

Margaret King (1773–1835), also known as Margaret King Moore, Lady Mount Cashell and Mrs Mason, was an Anglo-Irish hostess, and a writer of female-emancipatory fiction and health advice. Despite her wealthy aristocratic background, she had re ...

, would later say she 'had freed her mind from all superstitions'. Some of Wollstonecraft's experiences during this year would make their way into her only children's book, ''Original Stories from Real Life

''Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness'' is the only complete work of children's literature by the 18th-century English feminist author Mary Wollstone ...

'' (1788).

Frustrated by the limited career options open to respectable yet poor women—an impediment which Wollstonecraft eloquently describes in the chapter of '' Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'' entitled 'Unfortunate Situation of Females, Fashionably Educated, and Left Without a Fortune'—she decided, after only a year as a governess, to embark upon a career as an author. This was a radical choice, since, at the time, few women could support themselves by writing. As she wrote to her sister Everina in 1787, she was trying to become 'the first of a new genus'. She moved to London and, assisted by the liberal publisher Joseph Johnson, found a place to live and work to support herself. She learned French and German and translated texts, most notably ''Of the Importance of Religious Opinions'' by Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker (; 30 September 1732 – 9 April 1804) was a Genevan banker and statesman who served as finance minister for Louis XVI. He was a reformer, but his innovations sometimes caused great discontent. Necker was a constitutional monarchi ...

and ''Elements of Morality, for the Use of Children'' by Christian Gotthilf Salzmann. She also wrote reviews, primarily of novels, for Johnson's periodical, the '' Analytical Review''. Wollstonecraft's intellectual universe expanded during this time, not only from the reading that she did for her reviews but also from the company she kept: she attended Johnson's famous dinners and met the radical pamphleteer Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

and the philosopher William Godwin. The first time Godwin and Wollstonecraft met, they were disappointed in each other. Godwin had come to hear Paine, but Wollstonecraft assailed him all night long, disagreeing with him on nearly every subject. Johnson himself, however, became much more than a friend; she described him in her letters as a father and a brother.

In London, Wollstonecraft lived on Dolben Street, in Southwark; an up-and-coming area following the opening of the first Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple Ch ...

in 1769. While in London, Wollstonecraft pursued a relationship with the artist Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli ( ; German: Johann Heinrich Füssli ; 7 February 1741 – 17 April 1825) was a Swiss painter, draughtsman and writer on art who spent much of his life in Britain. Many of his works, such as '' The Nightmare'', deal with supernatu ...

, even though he was already married. She was, she wrote, enraptured by his genius, 'the grandeur of his soul, that quickness of comprehension, and lovely sympathy'. She proposed a platonic living arrangement with Fuseli and his wife, but Fuseli's wife was appalled, and he broke off the relationship with Wollstonecraft. After Fuseli's rejection, Wollstonecraft decided to travel to France to escape the humiliation of the incident, and to participate in the revolutionary events that she had just celebrated in her recent '' Vindication of the Rights of Men'' (1790). She had written the ''Rights of Men'' in response to the Whig MP Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

's politically conservative critique of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

in ''Reflections on the Revolution in France

''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' is a political pamphlet written by the Irish statesman Edmund Burke and published in November 1790. It is fundamentally a contrast of the French Revolution to that time with the unwritten British Const ...

'' (1790) and it made her famous overnight. ''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' was published on 1 November 1790, and so angered Wollstonecraft that she spent the rest of the month writing her rebuttal. ''A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke'' was published on 29 November 1790, initially anonymously;Furniss 60. the second edition of ''A Vindication of the Rights of Men'' was published on 18 December, and this time the publisher revealed Wollstonecraft as the author.

Wollstonecraft called the French Revolution a 'glorious ''chance'' to obtain more virtue and happiness than hitherto blessed our globe'.Furniss 61. Against Burke's dismissal of the Third Estate as men of no account, Wollstonecraft wrote, 'Time may show, that this obscure throng knew more of the human heart and of legislation than the profligates of rank, emasculated by hereditary effeminacy'. About the events of 5–6 October 1789, when the royal family was marched from Versailles to Paris by a group of angry housewives, Burke praised Queen Marie Antoinette as a symbol of the refined elegance of the ''ancien régime'', who was surrounded by "furies from hell, in the abused shape of the vilest of women". Wollstonecraft by contrast wrote of the same event: "Probably you urkemean women who gained a livelihood by selling vegetables or fish, who never had any advantages of education".

Wollstonecraft was compared with such leading lights as the theologian and controversialist Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

and Paine, whose ''Rights of Man

''Rights of Man'' (1791), a book by Thomas Paine, including 31 articles, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Using these points as a base it defends the ...

'' (1791) would prove to be the most popular of the responses to Burke. She pursued the ideas she had outlined in ''Rights of Men'' in ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

'' (1792), her most famous and influential work. Wollstonecraft's fame extended across the English channel, for when the French statesmen Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (, ; 2 February 1754 – 17 May 1838), 1st Prince of Benevento, then Prince of Talleyrand, was a French clergyman, politician and leading diplomat. After studying theology, he became Agent-General of the ...

visited London in 1792, he visited her, during which she asked that French girls be given the same right to an education that French boys were being offered by the new regime in France.

France

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December 1792 and arrived about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined. Britain and France were on the brink of war when she left for Paris, and many advised her not to go. France was in turmoil. She sought out other British visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the circle of expatriates then in the city. During her time in Paris, Wollstonecraft associated mostly with the moderate Girondins rather than the more radical

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December 1792 and arrived about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined. Britain and France were on the brink of war when she left for Paris, and many advised her not to go. France was in turmoil. She sought out other British visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the circle of expatriates then in the city. During her time in Paris, Wollstonecraft associated mostly with the moderate Girondins rather than the more radical Jacobins

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

. It was indicative that when Archibald Hamilton Rowan

Archibald Hamilton Rowan (1 May 1751 – 1 November 1834), christened Archibald Hamilton (sometimes referred to as Archibald Rowan Hamilton), was a founding member of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen, a political exile in France and the Unit ...

, the United Irishman

''The United Irishman'' was an Irish nationalist newspaper co-founded by Arthur Griffith and William Rooney.Arthur Griffith ...

, encountered her in the city in 1794 it was at a post-Terror festival in honour of the moderate revolutionary leader Mirabeau, who had been a great hero for Irish and English radicals before his death (from natural causes) in April 1791.

On 26 December 1792, Wollstonecraft saw the former king, Louis XVI, being taken to be tried before the National Assembly, and much to her own surprise, found 'the tears flow nginsensibly from my eyes, when I saw Louis sitting, with more dignity than I expected from his character, in a hackney coach going to meet death, where so many of his race have triumphed'.Furniss 65.

France declared war on Britain in February 1793. Wollstonecraft tried to leave France for Switzerland but was denied permission.Furniss 68. In March, the Jacobin-dominated Committee of Public Safety came to power, instituting a totalitarian regime meant to mobilise France for the first 'total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

'.

Life became very difficult for foreigners in France.Furniss 66. At first, they were put under police surveillance and, to get a residency permit, had to produce six written statements from Frenchmen testifying to their loyalty to the republic. Then, on 12 April 1793, all foreigners were forbidden to leave France.Furniss 67. Despite her sympathy for the revolution, life for Wollstonecraft become very uncomfortable, all the more so as the Girondins had lost out to the Jacobins. Some of Wollstonecraft's French friends lost their heads to the guillotine as the Jacobins set out to annihilate their enemies.

Gilbert Imlay, the Reign of Terror, and her first child

Having just written the ''Rights of Woman'', Wollstonecraft was determined to put her ideas to the test, and in the stimulating intellectual atmosphere of theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, she attempted her most experimental romantic attachment yet: she met and fell passionately in love with Gilbert Imlay, an American adventurer. Wollstonecraft put her own principles in practice by sleeping with Imlay even though they were not married, which was unacceptable behaviour from a 'respectable' British woman. Whether or not she was interested in marriage, he was not, and she appears to have fallen in love with an idealisation of the man. Despite her rejection of the sexual component of relationships in the ''Rights of Woman'', Wollstonecraft discovered that Imlay awakened her interest in sex.

Wollstonecraft was to a certain extent disillusioned by what she saw in France, writing that the people under the republic still behaved slavishly to those who held power while the government remained 'venal' and 'brutal'. Despite her disenchantment, Wollstonecraft wrote:

I cannot yet give up the hope, that a fairer day is dawning on Europe, though I must hesitatingly observe, that little is to be expected from the narrow principle of commerce, which seems everywhere to be shoving aside ''the point of honour'' of the ''noblesse'' obility For the same pride of office, the same desire of power are still visible; with this aggravation, that, fearing to return to obscurity, after having but just acquired a relish for distinction, each hero, or philosopher, for all are dubbed with these new titles, endeavors to make hay while the sun shines.Wollstonecraft was offended by the Jacobins' treatment of women. They refused to grant women equal rights, denounced ' Amazons', and made it clear that women were supposed to conform to

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

's ideal of helpers to men.Gordon 215. On 16 October 1793, Marie Antoinette was guillotined; among her charges and convictions, she was found guilty of committing incest with her son.Gordon 214–215. Though Wollstonecraft disliked the former queen, she was troubled that the Jacobins would make Marie Antoinette's alleged perverse sexual acts one of the central reasons for the French people to hate her.

As the daily arrests and executions of the Reign of Terror began, Wollstonecraft came under suspicion. She was, after all, a British citizen known to be a friend of leading Girondins. On 31 October 1793, most of the Girondin leaders were guillotined; when Imlay broke the news to Wollstonecraft, she fainted. By this time, Imlay was taking advantage of the British blockade of France, which had caused shortages and worsened ever-growing inflation, by chartering ships to bring food and soap from America and dodge the British Royal Navy, goods that he could sell at a premium to Frenchmen who still had money. Imlay's blockade-running gained the respect and support of some Jacobins, ensuring, as he had hoped, his freedom during the Terror. To protect Wollstonecraft from arrest, Imlay made a false statement to the U.S. embassy in Paris that he had married her, automatically making her an American citizen. Some of her friends were not so lucky; many, like Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

, were arrested, and some were even guillotined. Her sisters believed she had been imprisoned.

Wollstonecraft called life under the Jacobins 'nightmarish'. There were gigantic daytime parades requiring everyone to show themselves and lustily cheer lest they be suspected of inadequate commitment to the republic, as well as nighttime police raids to arrest 'enemies of the republic'. In a March 1794 letter to her sister Everina, Wollstonecraft wrote:

It is impossible for you to have any idea of the impression the sad scenes I have been a witness to have left on my mind ... death and misery, in every shape of terrour, haunts this devoted country—I certainly am glad that I came to France, because I never could have had else a just opinion of the most extraordinary event that has ever been recorded.Wollstonecraft soon became pregnant by Imlay, and on 14 May 1794 she gave birth to her first child, Fanny, naming her after perhaps her closest friend. Wollstonecraft was overjoyed; she wrote to a friend, 'My little Girl begins to suck so MANFULLY that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the R ghs of Woman' (emphasis hers). She continued to write avidly, despite not only her pregnancy and the burdens of being a new mother alone in a foreign country, but also the growing tumult of the French Revolution. While at

Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

in northern France, she wrote a history of the early revolution, ''An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution'', which was published in London in December 1794. Imlay, unhappy with the domestic-minded and maternal Wollstonecraft, eventually left her. He promised that he would return to her and Fanny at Le Havre, but his delays in writing to her and his long absences convinced Wollstonecraft that he had found another woman. Her letters to him are full of needy expostulations, which most critics explain as the expressions of a deeply depressed woman, while others say they resulted from her circumstances—a foreign woman alone with an infant in the middle of a revolution that had seen good friends imprisoned or executed.

The fall of the Jacobins and ''An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution''

In July 1794, Wollstonecraft welcomed the fall of the Jacobins, predicting it would be followed with a restoration of freedom of the press in France, which led her to return to Paris. In August 1794, Imlay departed for London and promised to return soon. In 1793, the British government had begun a crackdown on radicals, suspending civil liberties, imposing drastic censorship, and trying for treason anyone suspected of sympathy with the revolution, which led Wollstonecraft to fear she would be imprisoned if she returned. The winter of 1794–95 was the coldest winter in Europe for over a century, which reduced Wollstonecraft and her daughter Fanny to desperate circumstances. The river Seine froze that winter, which made it impossible for ships to bring food and coal to Paris, leading to widespread starvation and deaths from the cold in the city. Wollstonecraft continued to write to Imlay, asking him to return to France at once, declaring she still had faith in the revolution and did not wish to return to Britain. After she left France on 7 April 1795, she continued to refer to herself as 'Mrs Imlay', even to her sisters, in order to bestow legitimacy upon her child. The British historian Tom Furniss called ''An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution'' the most neglected of Wollstonecraft's books. It was first published in London in 1794, but a second edition did not appear until 1989. Later generations were more interested in her feminist writings than in her account of the French Revolution, which Furniss has called her 'best work'. Wollstonecraft was not trained as a historian, but she used all sorts of journals, letters and documents recounting how ordinary people in France reacted to the revolution. She was trying to counteract what Furniss called the 'hysterical' anti-revolutionary mood in Britain, which depicted the revolution as due to the entire French nation's going mad. Wollstonecraft argued instead that the revolution arose from a set of social, economic and political conditions that left no other way out of the crisis that gripped France in 1789. ''An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution'' was a difficult balancing act for Wollstonecraft. She condemned the Jacobin regime and the Reign of Terror, but at same time she argued that the revolution was a great achievement, which led her to stop her history in late 1789 rather than write about the Terror of 1793–94. Edmund Burke had ended his ''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' with reference to the events of 5–6 October 1789, when a group of women from Paris forced the French royal family from the Palace of Versailles to Paris. Burke called the women 'furies from hell', while Wollstonecraft defended them as ordinary housewives angry about the lack of bread to feed their families. Against Burke's idealised portrait of Marie Antoinette as a noble victim of a mob, Wollstonecraft portrayed the queen as a ''femme fatale'', a seductive, scheming and dangerous woman.Callender 384. Wollstonecraft argued that the values of the aristocracy corrupted women in a monarchy because women's main purpose in such a society was to bear sons to continue a dynasty, which essentially reduced a woman's value to only her womb. Moreover, Wollstonecraft pointed out that unless a queen was aqueen regnant

A queen regnant (plural: queens regnant) is a female monarch, equivalent in rank and title to a king, who reigns '' suo jure'' (in her own right) over a realm known as a "kingdom"; as opposed to a queen consort, who is the wife of a reigni ...

, most queens were queen consorts, which meant a woman had to exercise influence via her husband or son, encouraging her to become more and more manipulative. Wollstonecraft argued that aristocratic values, by emphasising a woman's body and her ability to be charming over her mind and character, had encouraged women like Marie Antoinette to be manipulative and ruthless, making the queen into a corrupted and corrupting product of the ''ancien régime''.

In ''Biographical Memoirs of the French Revolution'' (1799) the historian John Adolphus, F.S.A., condemned Wollstonecraft's work as a 'rhapsody of libellous declamations' and took particular offense at her depiction of King Louis XVI.

England and William Godwin

Seeking Imlay, Wollstonecraft returned to London in April 1795, but he rejected her. In May 1795 she attempted to commit suicide, probably with laudanum, but Imlay saved her life (although it is unclear how). In a last attempt to win back Imlay, she embarked upon some business negotiations for him in Scandinavia, trying to locate a Norwegian captain who had absconded with silver that Imlay was trying to get past the British blockade of France. Wollstonecraft undertook this hazardous trip with only her young daughter and Marguerite, her maid. She recounted her travels and thoughts in letters to Imlay, many of which were eventually published as '' Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark'' in 1796. When she returned to England and came to the full realisation that her relationship with Imlay was over, she attempted suicide for the second time, leaving a note for Imlay: She then went out on a rainy night and "to make her clothes heavy with water, she walked up and down about half an hour" before jumping into the

She then went out on a rainy night and "to make her clothes heavy with water, she walked up and down about half an hour" before jumping into the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, but a stranger saw her jump and rescued her. Wollstonecraft considered her suicide attempt deeply rational, writing after her rescue, I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured.Gradually, Wollstonecraft returned to her literary life, becoming involved with Joseph Johnson's circle again, in particular with Mary Hays,

Elizabeth Inchbald

Elizabeth Inchbald (née Simpson, 15 October 1753 – 1 August 1821) was an English novelist, actress, dramatist, and translator. Her two novels, '' A Simple Story'' and '' Nature and Art'', have received particular critical attention.

Life

Bo ...

, and Sarah Siddons

Sarah Siddons (''née'' Kemble; 5 July 1755 – 8 June 1831) was a Welsh actress, the best-known tragedienne of the 18th century. Contemporaneous critic William Hazlitt dubbed Siddons as "tragedy personified".

She was the elder sister of Joh ...

through William Godwin. Godwin and Wollstonecraft's unique courtship began slowly, but it eventually became a passionate love affair. Godwin had read her ''Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark'' and later wrote that "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration." Once Wollstonecraft became pregnant, they decided to marry so that their child would be legitimate. Their marriage revealed the fact that Wollstonecraft had never been married to Imlay, and as a result she and Godwin lost many friends. Godwin was further criticised because he had advocated the abolition of marriage in his philosophical treatise ''Political Justice

''Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness'' is a 1793 book by the philosopher William Godwin, in which the author outlines his political philosophy. It is the first modern work to expound anarchism.

Backg ...

''. After their marriage on 29 March 1797, Godwin and Wollstonecraft moved to 29 The Polygon, Somers Town. Godwin rented an apartment 20 doors away at 17 Evesham Buildings in Chalton Street as a study, so that they could both still retain their independence; they often communicated by letter. By all accounts, theirs was a happy and stable, though brief, relationship.

Birth of Mary, death

On 30 August 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter,

On 30 August 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter, Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

. Although the delivery seemed to go well initially, the placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste exchange between the physically separate mate ...

broke apart during the birth and became infected; childbed fever (post-partum infection) was a common and often fatal occurrence in the eighteenth century. After several days of agony, Wollstonecraft died of septicaemia

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

on 10 September. Godwin was devastated: he wrote to his friend Thomas Holcroft

Thomas Holcroft (10 December 174523 March 1809) was an English dramatist, miscellanist, poet and translator. He was sympathetic to the early ideas of the French Revolution and helped Thomas Paine to publish the first part of ''The Rights of Ma ...

, "I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again." She was buried in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church, where her tombstone reads "Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Author of ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman'': Born 27 April 1759: Died 10 September 1797."

Posthumous, Godwin's ''Memoirs''

In January 1798 Godwin published his '' Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman''. Although Godwin felt that he was portraying his wife with love, compassion, and sincerity, many readers were shocked that he would reveal Wollstonecraft's illegitimate children, love affairs, and suicide attempts. The Romantic poetRobert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

accused him of "the want of all feeling in stripping his dead wife naked" and vicious satires such as '' The Unsex'd Females'' were published. Godwin's ''Memoirs'' portrays Wollstonecraft as a woman deeply invested in feeling who was balanced by his reason and as more of a religious sceptic than her own writings suggest. Godwin's views of Wollstonecraft were perpetuated throughout the nineteenth century and resulted in poems such as "Wollstonecraft and Fuseli" by British poet Robert Browning and that by William Roscoe

William Roscoe (8 March 175330 June 1831) was an English banker, lawyer, and briefly a Member of Parliament. He is best known as one of England's first abolitionists, and as the author of the poem for children ''The Butterfly's Ball, and the G ...

which includes the lines:

Legacy

Maria Edgeworth

Maria Edgeworth (1 January 1768 – 22 May 1849) was a prolific Anglo-Irish novelist of adults' and children's literature. She was one of the first realist writers in children's literature and was a significant figure in the evolution of the n ...

, who patterned the 'freakish' Harriet Freke in ''Belinda

Belinda is a feminine given name of unknown origin, apparently coined from Italian ''bella'', meaning "beautiful". Alternatively it may be derived from the Old High German name ''Betlinde'', which possibly meant "bright serpent" or "bright linde ...

'' (1801) after her. Other novelists such as Mary Hays, Charlotte Smith, Fanny Burney, and Jane West created similar figures, all to teach a 'moral lesson' to their readers. (Hays had been a close friend, and helped nurse her in her dying days.) Pennell, Elizabeth Robins. ''Life of Mary Wollstonecraft'' (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1884), 351Full text.

/ref> In contrast, there was one writer of the generation after Wollstonecraft who apparently did not share the judgmental views of her contemporaries. Jane Austen never mentioned the earlier woman by name, but several of her novels contain positive allusions to Wollstonecraft's work.Mellor 156. The American literary scholar Anne K. Mellor notes several examples. In '' Pride and Prejudice'', Mr Wickham seems to be based upon the sort of man Wollstonecraft claimed that standing armies produce, while the sarcastic remarks of protagonist

Elizabeth Bennet

Elizabeth Bennet is the protagonist in the 1813 novel ''Pride and Prejudice'' by Jane Austen. She is often referred to as Eliza or Lizzy by her friends and family. Elizabeth is the second child in a family of five daughters. Though the circu ...

about 'female accomplishments' closely echo Wollstonecraft's condemnation of these activities. The balance a woman must strike between feelings and reason in ''Sense and Sensibility

''Sense and Sensibility'' is a novel by Jane Austen, published in 1811. It was published anonymously; ''By A Lady'' appears on the title page where the author's name might have been. It tells the story of the Dashwood sisters, Elinor (age 19) a ...

'' follows what Wollstonecraft recommended in her novel ''Mary'', while the moral equivalence Austen drew in '' Mansfield Park'' between slavery and the treatment of women in society back home tracks one of Wollstonecraft's favourite arguments. In '' Persuasion'', Austen's characterisation of Anne Eliot (as well as her late mother before her) as better qualified than her father to manage the family estate also echoes a Wollstonecraft thesis.

Scholar Virginia Sapiro states that few read Wollstonecraft's works during the nineteenth century as 'her attackers implied or stated that no self-respecting woman would read her work'. (Still, as Craciun points out, new editions of ''Rights of Woman'' appeared in the UK in the 1840s and in the US in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s.''A Routledge literary sourcebook on Mary Wollstonecraft's A vindication of the rights of woman''. Adriana Craciun, 2002, p. 36.) If readers were few, then ''many'' were inspired; one such reader was Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who read ''Rights of Woman'' at age 12 and whose poem ''Aurora Leigh

''Aurora Leigh'' (1856) is an epic poem/novel by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The poem is written in blank verse and encompasses nine books (the woman's number, the number of the Sibylline Books). It is a first-person narration, from the point o ...

'' reflected Wollstonecraft's unwavering focus on education. Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

, a Quaker minister, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Americans who met in 1840 at the World Anti-Slavery Convention

The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. It was organised by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The ex ...

in London, discovered they both had read Wollstonecraft, and they agreed upon the need for (what became) the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the tow ...

, an influential women's rights meeting held in 1848. Another woman who read Wollstonecraft was George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

, a prolific writer of reviews, articles, novels, and translations. In 1855, she devoted an essay to the roles and rights of women, comparing Wollstonecraft and Margaret Fuller. Fuller was an American journalist, critic, and women's rights activist who, like Wollstonecraft, had travelled to the Continent and had been involved in the struggle for reform (in this case the 1849 Roman Republic)—and she had a child by a man without marrying him. Wollstonecraft's children's tales were adapted by Charlotte Mary Yonge

Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823–1901) was an English novelist, who wrote in the service of the church. Her abundant books helped to spread the influence of the Oxford Movement and show her keen interest in matters of public health and sanitation.

...

in 1870.

Wollstonecraft's work was exhumed with the rise of the movement to give women a political voice. First was an attempt at rehabilitation in 1879 with the publication of Wollstonecraft's ''Letters to Imlay, with prefatory memoir'' by Charles Kegan Paul

Charles Kegan Paul (8 March 1828 – 19 July 1902) was an English clergyman, publisher and author. He began his adult life as a clergyman of the Church of England, and served the Church for more than 20 years. His religious orientation moved f ...

. Then followed the first full-length biography, which was by Elizabeth Robins Pennell

Elizabeth Robins Pennell (February 21, 1855 – February 7, 1936) was an American writer who, for most of her adult life, made her home in London. A recent researcher summed her up as "an adventurous, accomplished, self-assured, well-known colum ...

; it appeared in 1884 as part of a series by the Roberts Brothers on famous women. Millicent Garrett Fawcett, a suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and later president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies

The National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), also known as the ''suffragists'' (not to be confused with the suffragettes) was an organisation founded in 1897 of women's suffrage societies around the United Kingdom. In 1919 it was ren ...

, wrote the introduction to the centenary edition (i.e. 1892) of the ''Rights of Woman''; it cleansed the memory of Wollstonecraft and claimed her as the foremother of the struggle for the vote. By 1898, Wollstonecraft was the subject of a first doctoral thesis and its resulting book.

With the advent of the modern feminist movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such ...

, women as politically dissimilar from each other as Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

and Emma Goldman embraced Wollstonecraft's life story. By 1929 Woolf described Wollstonecraft—her writing, arguments, and 'experiments in living'—as immortal: 'she is alive and active, she argues and experiments, we hear her voice and trace her influence even now among the living'. Others, however, continued to decry Wollstonecraft's lifestyle. A biography published in 1932 refers to recent reprints of her works, incorporating new research, and to a "study" in 1911, a play in 1922, and another biography in 1924. Interest in her never completely died, with full-length biographies in 1937 and 1951.

With the emergence of

With the emergence of feminist criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or more broadly, by the politics of feminism. It uses the principles and ideology of feminism to critique the language of literature. This school of thought seeks to an ...

in academia in the 1960s and 1970s, Wollstonecraft's works returned to prominence. Their fortunes reflected that of the second wave of the North American feminist movement itself; for example, in the early 1970s, six major biographies of Wollstonecraft were published that presented her 'passionate life in apposition

Apposition is a grammatical construction in which two elements, normally noun phrases, are placed side by side so one element identifies the other in a different way. The two elements are said to be ''in apposition'', and one of the elements is ...

to erradical and rationalist agenda'. The feminist artwork ''The Dinner Party

''The Dinner Party'' is an installation artwork by feminist artist Judy Chicago. Widely regarded as the first epic feminist artwork, it functions as a symbolic history of women in civilization. There are 39 elaborate place settings on a triang ...

'', first exhibited in 1979, features a place setting for Wollstonecraft.

Wollstonecraft's work has also had an effect on feminism outside academia. Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Ayaan Hirsi Ali (; ; Somali: ''Ayaan Xirsi Cali'':'' Ayān Ḥirsī 'Alī;'' born Ayaan Hirsi Magan, ar, أيان حرسي علي / ALA-LC: ''Ayān Ḥirsī 'Alī'' 13 November 1969) is a Somali-born Dutch-American activist and former politicia ...

, a political writer and former Muslim who is critical of Islam in general and its dictates regarding women in particular, cited the ''Rights of Woman'' in her autobiography '' Infidel'' and wrote that she was 'inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft, the pioneering feminist thinker who told women they had the same ability to reason as men did and deserved the same rights'. British writer Caitlin Moran, author of the best-selling ''How to Be a Woman'', described herself as 'half Wollstonecraft' to the ''New Yorker''. She has also inspired more widely. Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen

Amartya Kumar Sen (; born 3 November 1933) is an Indian economist and philosopher, who since 1972 has taught and worked in the United Kingdom and the United States. Sen has made contributions to welfare economics, social choice theory, econom ...

, the Indian economist and philosopher who first identified the missing women of Asia

The term "missing women" indicates a shortfall in the number of women relative to the expected number of women in a region or country. It is most often measured through male-to-female sex ratios, and is theorized to be caused by sex-selective abort ...

, draws repeatedly on Wollstonecraft as a political philosopher in '' The Idea of Justice''.

In 2009, Wollstonecraft was selected by the Royal Mail for their "Eminent Britons" commemorative postage stamp issue. Several plaques have been erected to honour Wollstonecraft. A commemorative sculpture, '' A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft'' by Maggi Hambling

Margaret ("Maggi") J. Hambling (born 23 October 1945) is a British artist. Though principally a painter her best-known public works are the sculptures '' A Conversation with Oscar Wilde'' and '' A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft'' in London, ...

, was unveiled on 10 November 2020; it was criticised for its symbolic depiction rather than a lifelike representation of Wollstonecraft, which commentators felt represented stereotypical notions of beauty and the diminishing of women. In November 2020, it was announced that Trinity College Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

, whose library had previously held forty busts, all of them of men, was commissioning four new busts of women, one of whom would be Wollstonecraft.

Major works

Educational works

The majority of Wollstonecraft's early productions are about education; she assembled an anthology of literary extracts "for the improvement of young women" entitled ''The Female Reader'' and she translated two children's works, Maria Geertruida van de Werken de Cambon's ''Young Grandison'' and Christian Gotthilf Salzmann's ''Elements of Morality''. Her own writings also addressed the topic. In both her conduct book ''Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'' (1787) and her children's book ''Original Stories from Real Life'' (1788), Wollstonecraft advocates educating children into the emerging middle-class ethos: self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and social contentment. Both books also emphasise the importance of teaching children to reason, revealing Wollstonecraft's intellectual debt to the educational views of seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke. However, the prominence she affords religious faith and innate feeling distinguishes her work from his and links it to the discourse of sensibility popular at the end of the eighteenth century. Both texts also advocate the education of women, a controversial topic at the time and one which she would return to throughout her career, most notably in ''

The majority of Wollstonecraft's early productions are about education; she assembled an anthology of literary extracts "for the improvement of young women" entitled ''The Female Reader'' and she translated two children's works, Maria Geertruida van de Werken de Cambon's ''Young Grandison'' and Christian Gotthilf Salzmann's ''Elements of Morality''. Her own writings also addressed the topic. In both her conduct book ''Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'' (1787) and her children's book ''Original Stories from Real Life'' (1788), Wollstonecraft advocates educating children into the emerging middle-class ethos: self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and social contentment. Both books also emphasise the importance of teaching children to reason, revealing Wollstonecraft's intellectual debt to the educational views of seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke. However, the prominence she affords religious faith and innate feeling distinguishes her work from his and links it to the discourse of sensibility popular at the end of the eighteenth century. Both texts also advocate the education of women, a controversial topic at the time and one which she would return to throughout her career, most notably in ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

''. Wollstonecraft argues that well-educated women will be good wives and mothers and ultimately contribute positively to the nation.

''Vindications''

''Vindication of the Rights of Men'' (1790)

Published in response toEdmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

's ''Reflections on the Revolution in France

''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' is a political pamphlet written by the Irish statesman Edmund Burke and published in November 1790. It is fundamentally a contrast of the French Revolution to that time with the unwritten British Const ...

'' (1790), which was a defence of constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, aristocracy, and the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, and an attack on Wollstonecraft's friend, the Rev. Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

at the Newington Green Unitarian Church

Newington Green Unitarian Church (NGUC) in north London is one of England's oldest Unitarian churches. It has had strong ties to political radicalism for over 300 years, and is London's oldest Nonconformist place of worship still in use. It wa ...

, Wollstonecraft's ''A Vindication of the Rights of Men'' (1790) attacks aristocracy and advocates republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

. Hers was the first response in a pamphlet war that subsequently became known as the '' Revolution Controversy'', in which Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

's ''Rights of Man

''Rights of Man'' (1791), a book by Thomas Paine, including 31 articles, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Using these points as a base it defends the ...

'' (1792) became the rallying cry for reformers and radicals.

Wollstonecraft attacked not only monarchy and hereditary privilege but also the language that Burke used to defend and elevate it. In a famous passage in the ''Reflections'', Burke had lamented: "I had thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful