Martin Farquhar Tupper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Martin Farquhar Tupper (17 July 1810 – 29 November 1889) was an English poet and novelist. He was one of the most widely-read English-language authors of his day with the poetry collection ''Proverbial Philosophy'', which was a bestseller in the United Kingdom and North America for several decades.

Tupper found great success in Victorian Britain at a relatively early age, with a second series of the poetry collection ''Proverbial Philosophy'' in 1842. The work's fame later spread to the US and Canada, and it continued to be popular for several decades. The author capitalised on this success with scores of editions in various formats and tours in his homeland and in North America, and as one of

Tupper's most successful work had its genesis in 1828, shortly before his Oxford matriculation. At this time he was engaged to Isabella, and he decided to write his "notions on the holy estate of matrimony" for her, "in the manner of

Tupper's most successful work had its genesis in 1828, shortly before his Oxford matriculation. At this time he was engaged to Isabella, and he decided to write his "notions on the holy estate of matrimony" for her, "in the manner of

Despite making almost no money from his written works in North America, Tupper recognised the potential of his enormous popularity on the other side of the Atlantic. Having overcome his stammer at the age of 35, he embarked on a "wildly successful" reading tour of the Eastern USA and Canada, setting off from

Despite making almost no money from his written works in North America, Tupper recognised the potential of his enormous popularity on the other side of the Atlantic. Having overcome his stammer at the age of 35, he embarked on a "wildly successful" reading tour of the Eastern USA and Canada, setting off from

By 1851 Tupper had fathered eight children, and had moved his large family into the spacious Albury House in Albury, Surrey approximately ten years previously. However, his financial position became precarious by the mid-1850s. His wife Isabella had fallen ill, and he wrote to Gladstone (then

By 1851 Tupper had fathered eight children, and had moved his large family into the spacious Albury House in Albury, Surrey approximately ten years previously. However, his financial position became precarious by the mid-1850s. His wife Isabella had fallen ill, and he wrote to Gladstone (then

Given that ''Proverbial Philosophy'' was published by the author when he was a young man, who went on to live a long life and write prolifically, he was an easy target for satire from new generations and changing tastes – "Tupper's visage was everywhere ... His very generosity and omnipresence worked against him. By the 1870s, each week began to bring fresh pummelings by clever young men in humor magazines like '' Punch'', '' Figaro'' and ''The Comic''." Hudson (1949) quotes examples dating from 1864:

Once the satire was played out, Tupper's work was forgotten. , none of his works have been in print since the final edition of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' in 1881, although digital transcriptions and facsimiles can now be found.

Given that ''Proverbial Philosophy'' was published by the author when he was a young man, who went on to live a long life and write prolifically, he was an easy target for satire from new generations and changing tastes – "Tupper's visage was everywhere ... His very generosity and omnipresence worked against him. By the 1870s, each week began to bring fresh pummelings by clever young men in humor magazines like '' Punch'', '' Figaro'' and ''The Comic''." Hudson (1949) quotes examples dating from 1864:

Once the satire was played out, Tupper's work was forgotten. , none of his works have been in print since the final edition of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' in 1881, although digital transcriptions and facsimiles can now be found.

Albury History Society

contains some details about Tupper's connection to Albury, Surrey {{DEFAULTSORT:Tupper, Martin Farquhar 1810 births 1889 deaths Fellows of the Royal Society Poets from London English male poets 19th-century English poets 19th-century English male writers Victorian poets People educated at Eagle House School People educated at Charterhouse School Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford 19th-century English novelists English male novelists Victorian novelists 19th-century English short story writers English male short story writers Victorian short story writers Novelists from London English historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in the Middle Ages English barristers 19th-century English essayists English male essayists 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights English male dramatists and playwrights English nonconformist hymnwriters English Protestants English archaeologists

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

's favourite poets he was once a serious contender for the position of Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom

The British poet laureate is an honorary position appointed by the monarch of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister. The role does not entail any specific duties, but there is an expectation ...

. However, ''Proverbial Philosophy'' eventually fell out of fashion, and its previous eminence made the poetry and its author popular targets for satire and parody.

Despite his prodigious output and ongoing efforts at self-promotion, Tupper's other work did not achieve anywhere close to the bestseller status of ''Proverbial Philosophy'', and even towards the end of the poet's own lifetime he had become obscure. Nevertheless, the style of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' (which Tupper referred to as "rhythmics" rather than poetry) had an influence on admirer Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

, who was also experimenting with free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry which does not use a prescribed or regular meter or rhyme and tends to follow the rhythm of natural or irregular speech. Free verse encompasses a large range of poetic form, and the distinction between free ...

. Considered by later generations to be artefacts of their time, Tupper's works have largely been forgotten, and had been out of print for over a century.

Early life

Martin Farquhar Tupper was born on 17 July 1810 at 20 Devonshire Place,London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. He was the eldest child of Dr. Martin Tupper, an esteemed doctor from an old Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

family, and his wife Ellin Devis Marris, the daughter of landscape painter Robert Marris (1749–1827) and granddaughter of Arthur Devis.

Martin F. Tupper received his early education at Eagle House School and Charterhouse, going on to attend Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

where he received a BA in 1832. At university he was the classmate of many distinguished men, including future politicians James Broun-Ramsay, James Bruce

James Bruce of Kinnaird (14 December 1730 – 27 April 1794) was a Scottish traveller and travel writer who physically confirmed the source of the Blue Nile. He spent more than a dozen years in North and East Africa and in 1770 became the fir ...

, Henry Pelham-Clinton, Charles Canning, George Cornewall Lewis and William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, as well as literary figures Francis Hastings Doyle

Sir Francis Hastings Charles Doyle, 2nd Baronet (21 August 1810 – 8 June 1888) was a British poet.

Biography

Doyle was born near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, to a military family which produced several distinguished officers, including his father, Ma ...

, Henry Liddell

Henry George Liddell (; 6 February 1811– 18 January 1898) was Dean (college), dean (1855–1891) of Christ Church, Oxford, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University (1870–1874), headmaster (1846–1855) of Westminster School (where a house is n ...

and Robert Scott. He maintained a close friendship with Gladstone until the final years of his life.

From a young age Tupper suffered from a severe stammer, which precluded him from going into the church or politics. Having taken the further degree of MA, Tupper became a student at Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

and was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1835, but did not ever practise as a barrister.

On 26 November of the same year Tupper married his first cousin Isabella Devis, daughter of Arthur William Devis, in St Pancras Church, having proposed to her before leaving for university seven years previously. He acquired a house on Park Village East, near Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, Borough of Camden (and historical ...

, and the couple was financially supported by his father. While living here, Tupper attended St James' Chapel on Hampstead Road (now demolished), where he became acquainted with its minister Henry Stebbing. An author and former editor of the literary magazine the Athenaeum, Stebbing's encouragement of Tupper's writings eventually led to the publication of ''Proverbial Philosophy''.

Career

Early works

While at Oxford, Tupper's literary career commenced; his first important publication was a collection of 75 short poems entitled ''Sacra Poesis'' (1832). In the same year he wrote a long poem partially inblank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metre (poetry), metrical but rhyme, unrhymed lines, usually in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th cen ...

, "A Voice from the Cloister", but this was only published, anonymously, in 1835.

In the summer of 1838 Tupper penned a continuation of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

's ''Christabel'', naming it ''Geraldine'' and publishing it alongside various other pieces in the latter half of that year in the collection ''Geraldine, a sequel to Coleridge's Christabel: with other poems''. The poem ''Geraldine'' itself met with some critical reprobation, although in his contemporary notes Tupper attributes this largely to it being a continuation of an early version of Coleridge's poem: "When Coleridge first published Christabel ... it was positively hooted by the critics ... Coleridge left behind him a very much improved and enlarged version of the poem, which I did not see till years after I had written the sequel to it: my Geraldine was composed for an addition to Christabel, as originally issued." The other poems in the collection were more warmly received.

''Proverbial Philosophy''

Tupper's most successful work had its genesis in 1828, shortly before his Oxford matriculation. At this time he was engaged to Isabella, and he decided to write his "notions on the holy estate of matrimony" for her, "in the manner of

Tupper's most successful work had its genesis in 1828, shortly before his Oxford matriculation. At this time he was engaged to Isabella, and he decided to write his "notions on the holy estate of matrimony" for her, "in the manner of Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

's proverbs". Isabella showed them to Hugh M'Neile

Hugh Boyd M‘Neile (18 July 1795 – 28 January 1879) was a well-connected and controversial Irish-born Calvinist Anglicanism, Anglican of Scottish descent.

Fiercely anti-Oxford Movement, Tractarian and anti-Roman Catholic (and, even more so, ...

, who suggested seeking publication, but Tupper chose not to do so at the time.

In 1837, on the encouragement of Henry Stebbing, Tupper began to revise these writings and expand them into a book, working on them at home and in his workplace, Lincoln's Inn, over the subsequent 10 weeks. The work takes the form of free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry which does not use a prescribed or regular meter or rhyme and tends to follow the rhythm of natural or irregular speech. Free verse encompasses a large range of poetic form, and the distinction between free ...

meditations on morality ("OfHumility", "OfPride"), religion ("OfPrayer", "TheTrain of Religion"), and other aspects of the human condition

The human condition can be defined as the characteristics and key events of human life, including birth, learning, emotion, aspiration, reason, morality, conflict, and death. This is a very broad topic that has been and continues to be pondered ...

("OfLove", "OfJoy"). Tupper did not refer to the pieces as poetry, preferring his own description of "rhythmics".

Stebbing referred Tupper to the publisher Joseph Rickerby, who agreed to publish the work on a profit-sharing basis, and this first official version appeared on 24 January 1838 entitled ''Proverbial Philosophy: A Book of Thoughts and Arguments, originally treated, by Martin Farquhar Tupper, Esq., M.A.'' at a price of 7 s. It met with moderate success in Britain; a second edition was commissioned, to which Tupper added more material, and sold for 6s. A third edition emerged, but this failed to sell well; the unsold copies were sent to America, where it was received poorly. "Americans scarcely knew what to make of it at all; one of the few stateside reviewers to read ''Proverbial Philosophy'', the powerful editor N.P. Willis, was so perplexed by the form of the book that he guessed it to have been written ... in the seventeenth century."

Despite the lack of interest in the third edition, in 1841 Tupper was spurred to write a second series of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' at the suggestion of John Hughes, who he had met in a chance encounter in Windsor two years previously. This series was to be serialised in the new publication Ainsworth's Magazine, William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 18053 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in ...

being a friend of Hughes. Tupper and his family temporarily moved to Brighton

Brighton ( ) is a seaside resort in the city status in the United Kingdom, city of Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England, south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze Age Britain, Bronze Age, R ...

where he produced some initial pieces for the magazine, as well as some essays. However, being "too quick and too impatient to wait for piecemeal publication month by month", Tupper collated his new "rhythmics" and had the second series of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' published as a whole, on 5 October 1842 by John Hatchard.

The second series was sold alongside the fifth edition of the first series, and proved to be immediately popular. The two were soon combined into one collection, still entitled ''Proverbial Philosophy'', and this iteration became an enormous success over the subsequent decades:

In the 1850s the work was translated into several languages, including German, Swedish, Danish, Armenian, and a French version by George Métivier. By 1866 it had sold over 200,000 copies in the United Kingdom, through forty editions.

Tupper did go on to write a third and fourth series in 1867 and 1869 respectively, published by Edward Moxon in his ''Moxon's Popular Poets'' series (which had previously included luminaries such as Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

, Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ...

, Coleridge, Keats and Milton). However, by this time Tupper had fallen out of fashion, and these latter series did not sell well. Moxon had already been in bad financial straits, and Tupper's new works did not change his fortunes; the publisher was shortly taken over.

Over the course of the author's lifetime it is estimated that between one quarter and half a million copies were sold in England, and over 1.5 million in the United States, across 50 editions. Due to the lack of international copyright laws, the US market was dominated by pirated copies; consequently, Tupper made almost no money from the work's enormous American sales. However, he did manage to capitalise on his fame in North America by undertaking two tours of the US and Canada, in 1851 and 1876-1877.

Candidate for Poet Laureate

Upon the death ofWilliam Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

in 1850, Tupper began to suggest his willingness to fill the now-vacant position of Poet Laureate to influential friends and acquaintances such as William Gladstone and James Garbett, who further gathered support. He continued to write poems for public events in order to demonstrate his capability, marking occasions such as the deaths of Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

and the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge is a hereditary title of nobility in the British royal family, one of several royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom. The title is named after the city of Cambridge in England. It is heritable by agnatic, male descendants by pr ...

, as well as the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

, for which he published ''Hymn to the Exhibition'' in over sixty languages (set to music by Samuel Sebastian Wesley

Samuel Sebastian Wesley (14 August 1810 – 19 April 1876) was an English organ (music), organist and composer. Wesley married Mary Anne Merewether and had 6 children. He is often referred to as S.S. Wesley to avoid confusion with his father Sa ...

). It appears that his candidacy had popular support, from both sides of the Atlantic. However, the eventual selection was Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of ...

, partly due to Prince Albert's admiration of the poem In Memoriam A.H.H.

First tour of America

Despite making almost no money from his written works in North America, Tupper recognised the potential of his enormous popularity on the other side of the Atlantic. Having overcome his stammer at the age of 35, he embarked on a "wildly successful" reading tour of the Eastern USA and Canada, setting off from

Despite making almost no money from his written works in North America, Tupper recognised the potential of his enormous popularity on the other side of the Atlantic. Having overcome his stammer at the age of 35, he embarked on a "wildly successful" reading tour of the Eastern USA and Canada, setting off from Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

on 2 March 1851 and landing in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

two weeks later. His arrival was announced in American newspapers, and while based in the city he met a variety of literary figures including William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the '' New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poe ...

, Nathaniel Parker Willis

Nathaniel Parker Willis (January 20, 1806 – January 20, 1867), also known as N. P. Willis,Baker, 3 was an American writer, poet and editor who worked with several notable American writers including Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfello ...

, James Gordon Bennett Sr., James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonial and indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

, and Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He wrote the short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legend of Sleepy ...

. He was generally warmly received by the people he met, although his tendency to quote his own poetry was "deemed unseemly at the time" and criticised in the press, as was his perceived "patronising attitude and sentimentalism" towards Americans.

An indication of Tupper's popularity in the US is given by his dealings with one of his publishers in Philadelphia:

The highlight of the American tour was a dinner at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

on 8 May with President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

and members of his cabinet, Fillmore himself being an admirer of the poet. In his autobiography Tupper quotes his contemporaneous notes:

After stops in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

and Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Tupper returned to New York, where he was noticed in a concert crowd by its promoter P. T. Barnum

Phineas Taylor Barnum (July 5, 1810 – April 7, 1891) was an American showman, businessman, and politician remembered for promoting celebrated hoaxes and founding with James Anthony Bailey the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. He was ...

and brought backstage to meet Jenny Lind

Johanna Maria Lind (Madame Goldschmidt) (6 October 18202 November 1887) was a Swedish opera singer, often called the "Swedish Nightingale". One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed in soprano roles in opera in ...

. The Swedish Nightingale was an admirer - "she sat holding Tupper's hand and crying with emotion while the management of the theatre frantically tried to get her on stage for a bow." He set off on his return trip to Liverpool on 24 May 1851, seen off by a group of admirers and "regretful paragraphs" in the New York newspapers.

Middle years

By 1851 Tupper had fathered eight children, and had moved his large family into the spacious Albury House in Albury, Surrey approximately ten years previously. However, his financial position became precarious by the mid-1850s. His wife Isabella had fallen ill, and he wrote to Gladstone (then

By 1851 Tupper had fathered eight children, and had moved his large family into the spacious Albury House in Albury, Surrey approximately ten years previously. However, his financial position became precarious by the mid-1850s. His wife Isabella had fallen ill, and he wrote to Gladstone (then Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

) to request an office or public pension, to no avail. His eldest son, Martin Charles Selwyn (born 1841), was made the youngest Captain in the British Army by purchase in 1864, but it fell upon his father to settle his many drinking and gambling debts, and fund a spell in an asylum in St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the London Borough of Camden, London Boroughs of Camden and the City of Westminster, London, England, about 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Historically the northern part of the Civil Parish#An ...

, until he was relocated to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

in 1868. These financial strains were compounded by a series of poor investments. Tupper managed to stay afloat by continuing to publish poetry, and bringing out new editions of ''Proverbial Philosophy'', including an illustrated version, but he was compelled to let out Albury House from 1867 to generate additional income.

Tupper was already a favourite poet of Queen Victoria, and in June 1857, having written sonnets for each of the engaged couple Victoria, Princess Royal

Victoria, Princess Royal (Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa; 21 November 1840 – 5 August 1901) was German Empress and Queen of Prussia as the wife of Frederick III, German Emperor. She was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom ...

and Prince Frederick, was granted the honour of being "summoned to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

, to be received by the Queen herself and Prince Albert

Prince Albert most commonly refers to:

*Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819–1861), consort of Queen Victoria

*Albert II, Prince of Monaco (born 1958), present head of state of Monaco

Prince Albert may also refer to:

Royalty

* Alb ...

, and to present special copies of 'Proverbial Philosophy' with his own hands to the young betrothed." The circumstances of this audience were highly unusual, as Tupper was instructed to meet the Royal Family on a Sunday after church – "the Royal Family had never entertained a private individual in this way since George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

had summoned Dr Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary criticism, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicograp ...

." Tupper's work was already well known to the family, having been appreciated by the children's governess and their drawing master Edward Henry Corbould (who also happened to be Tupper's friend), and he had written pieces for the children to perform for their parents previously.

Tupper continued to write poetry for periodicals and publications of his own work, but none of these came close to the popularity of ''Proverbial Philosophy''. By the mid-1860s he and his work were being persistently satirised by a new generation of Victorians, the victims of changing tastes (see ).

British and second American tours

Deciding to focus on readings of his works instead of continuing to pen new material to be satirised or ignored, Tupper began touring south-west England in April 1873. These events were somewhat popular, although apart from the "fair-sized audiences, largely composed of ladies" there were also "many who only came to satisfy themselves that such a fabulous being as Martin Tupper really existed". The most popular of his works were "Love" and "Marriage" from ''Proverbial Philosophy'', as well as the poems "Never Give Up" and "All's for the Best". Later in the year he also toured Scotland, to a warmer reception. After his Scottish success, Tupper decided to undertake a second American tour; delayed by illness, he arrived in October 1876 and stayed in New York as the guest of Thomas De Witt Talmage, an admirer of ''Proverbial Philosophy''. Much like in Britain, this tour was filled with public readings of his works; while his American popularity had also declined, it was not to the extent that it had in his home country, and he delivered a reading of "Immortality" to his largest-ever audience, between five and six thousand – the congregation of Talmage's church. However, Tupper often failed to attract large crowds on the merit of his readings alone; he performed to several thousand at one event in Philadelphia, but only a few hundred at various events in New York State and Canada. After the huge success of his first American tour, this one "proved a pale shadow". Nevertheless, it was profitable, and his stature was such that he was invited to the inauguration and White House reception of President Hayes.Later life and death

By the time of his return from his second American tour on 16 April 1877, Tupper had fallen into obscurity in his home country. His attempts to publish a complete collection of his works failed; each of the 26 publishers he approached had declined. Continually short of money, in 1880 was obliged to mortgage his longtime home of Albury House to theDuke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke of N ...

. He and his family moved to a small rental property in Upper Norwood

Upper Norwood is an area of south London, England, within the London Boroughs of London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, London Borough of Croydon, Croydon, London Borough of Lambeth, Lambeth and London Borough of Southwark, Southwark. It is north ...

.

Tupper made a final attempt at a new printing of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' in 1881, a large illustrated quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

, but this failed to sell. He continued to write articles and plays, managing to publish ''Dramatic Pieces'' in 1882, and he also delivered occasional lectures and readings. Around this time he and Gladstone, friends since childhood, fell out over Gladstone's views on the circumstances that led to the Oaths Act 1888, and his refusal to continue to support the author financially.

In late 1885 Tupper started to write an autobiography, which was published in May 1886 under the title ''My Life as an Author''. His wife Isabella had died during its composition, in December 1885, from apoplexy

Apoplexy () refers to the rupture of an internal organ and the associated symptoms. Informally or metaphorically, the term ''apoplexy'' is associated with being furious, especially as "apoplectic". Historically, it described what is now known as a ...

, and he included a tribute to her in the work. It received fairly warm reviews, but never ran to a second edition, despite the author working on improvements and corrections after publication.

Tupper's last published work was the booklet "Jubilate!", which contained new poems for the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria

The Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria was celebrated on 20 and 21 June 1887 to mark the Golden jubilee, 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession on 20 June 1837. It was celebrated with a National service of thanksgiving, Thanksgiving Serv ...

as well as the work he had written in honour of her coronation fifty years earlier.

In November 1886 Tupper suffered an illness of several days which robbed him of the ability to read and write. He remained in a fragile state for his remaining three years, being cared for by his children, never learning that during that period Albury House had been foreclosed by the Duke of Northumberland. Eventually he died, on 29 November 1889, and was buried in Albury churchyard in the same grave as his wife and son Martin Charles Selwyn, with an epitaph reading "He being dead yet speaketh".

Personal beliefs

Religion

Tupper was a passionate lifelongProtestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

:

The contrast between his beliefs and those of his close friend William Gladstone, who was raised Evangelical but sympathised with the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

later in life, became a frequent source of friction between the two. Tupper at one point challenged him with the question "are you a hearty friend of the Protestant Reformation?", and the difference of views was a contributing factor to their eventual falling out.

Tupper's religion played a large role in his works, both in terms of the genesis and reception of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' ("There was room for a work of moral principle, and of Evangelical temper, that would have a wide appeal"), as well as later in life, when he wrote "extreme Protestant ballads" for the Church of England paper ''The Rock''. Additionally, he was an early supporter of the Student Volunteer Movement, which was founded to encourage missionary work abroad.

Colonialism

During a time of increasing concern about the state of the British Empire's military forces, Tupper was a key voice in creating theVolunteer Force

The Volunteer Force was a citizen army of part-time rifle, artillery and engineer corps, created as a Social movement, popular movement throughout the British Empire in 1859. Originally highly autonomous, the units of volunteers became increa ...

, a movement which bolstered the army and helped lead to its professionalisation; he himself became the secretary of the "Blackheath Rifles" in 1859. He wrote jingoistic poems in support of the allied troops in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

and, controversially, urging severe punishment of those responsible for the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

. His ballads in the ''Globe

A globe is a spherical Earth, spherical Model#Physical model, model of Earth, of some other astronomical object, celestial body, or of the celestial sphere. Globes serve purposes similar to maps, but, unlike maps, they do not distort the surface ...

'' captured a popular mood of outrage at the delay in relief for General Gordon at the Siege of Khartoum

The siege of Khartoum (also known as the battle of Khartoum or fall of Khartoum) took place from 13 March 1884 to 26 January 1885. Mahdist State, Sudanese Mahdist forces captured the city of Khartoum, Sudan, from its Khedivate of Egypt, Egypti ...

, and earned the appreciation of Gordon's family.

Race and abolitionism

Tupper had an interest in the legacy of theAnglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

; he arranged an event to mark the thousandth anniversary of the birth of Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

in the king's birthplace of Wantage

Wantage () is a historic market town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Vale of White Horse, Oxfordshire, England. Although within the boundaries of the Historic counties of England, historic county of Berkshire, it has been a ...

, and was an erstwhile contributor to the short-lived magazine ''Anglo-Saxon'' (1849-1851), which was "devoted to the cause of friendship between the English-speaking peoples". However, this interest has overtones of racial superiority, as evinced by his 1850 ballad "The Anglo-Saxon Race": "Break forth and spread over every place / The world is a world for the Anglo Saxon race!". Critic Kwame Anthony Appiah

Kwame Akroma-Ampim Kusi Anthony Appiah ( ; born 8 May 1954) is an English-American philosopher and writer who has written about political philosophy, ethics, the philosophy of language and mind, and African intellectual history. Appiah is Prof ...

argues that Tupper's views on race were informed and limited by their time, quoting this poem as an example of the predominant colonialist understanding of "race" in the nineteenth century. Appia calls Tupper a "racialist": "He believed, as did most educated Victorians by the mid-century, that we could divide human beings into a small number of groups, called "races," in such a way that all members of these races shared certain fundamental ... characteristics with each other that they did not share with members of any other race."

Tupper was a proponent of abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

. While studying at Oxford he refused to eat sugar "by way of somehow discouraging the slave trade", and in 1848 he wrote a national anthem for Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

and advocated for the republic in communications with Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

and President Fillmore. He received presidents Roberts and Benson in his home as they came to thank him for his support. In addition he created a specific prize in order to encourage African literature

African literature is literature from Africa, either Oral literature, oral ("orature") or written in African languages, African and Afro-Asiatic languages, Afro-Asiatic languages. Examples of Precolonialism, pre-colonial African literature can be ...

, "biennially to be competed for by emancipated slaves".

Regarding the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, however, he was not entirely supportive of the anti-slavery Union. While he wrote to President Lincoln in May 1861 with the sentiment "May this Revolution bear the good fruit of total abolition of slavery all over the American continent ...!" and to Gladstone that "The South are responsible for this civil war", his later works demonstrate a sympathy for the Southern cause. During his second American tour, Tupper published a sympathetic "Ode to the South", beginning

Tupper's autobiography, written towards the very end of his life, recounts visiting a formerly slave-owning friend during the same tour:

Legacy

Tupper had no doubts as to his place in the pantheon of English literature. As Murphy (1937) notes, the closing lines of his autobiography are a confident indication of this, quoting from the epilogue ofOvid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

's Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' (, , ) is a Latin Narrative poetry, narrative poem from 8 Common Era, CE by the Ancient Rome, Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''Masterpiece, magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the world from its Cre ...

:

''Proverbial Philosophy'' in later years

Having enjoyed huge success for almost two decades, by the end of the 1850s ''Proverbial Philosophy'' started to fall out of favour in Britain as tastes and social attitudes changed. The first sign of this was an article by the influential ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

'' in its 1858 article "Charlatan Poetry: Martin Farquhar Tupper". Acknowledging that the poet's popularity was "one of the most unquestionable facts of the day ... We are quite aware that it would be utterly beyond our strength to displace him from his stronghold in public favour", the article proceeds with a lengthy criticism of his poetry: " ebelong to that small but respectable minority who regard Mr. Tupper's versicular philosophy as superficial and conceited twaddle".

Although it remained popular for many years, the ultimate challenge to the work's further longevity was that ''Proverbial Philosophy'' presents a style and viewpoint that are inextricably linked and of interest only to those who lived during the early-to-mid Victorian period. In his biography of Tupper, Hudson (1949) contends that "the success of 'Proverbial Philosophy' ... sprang primarily from the moral and religious movement of early Victorian days which gradually lost its impetus as the reign proceeded. It was the belief that art must be linked with morality that furthered the astonishing advance of Tupper's book". Dingley (2004) agrees: "He presented as vatic wisdom the established convictions of his readership, which responded by venerating him as a sage. But as those convictions themselves began to crumble in the 1860s, under the pressure of scientific advance and social change, so Tupper’s status declined and he came to seem an embarrassing survival from a superseded past, a victim of the progress he had so earnestly celebrated." Collins (2002) adds that the work was a victim of its own success: "The children who had once received gift book editions of Tupper for their birthdays were heartily sick of the man." As a piece of art that spoke only to people of its own time, the work has never experienced a revival of interest: "It put the weight of tradition and common sense behind social values and interpretations which were in reality peculiar to Victorianism."

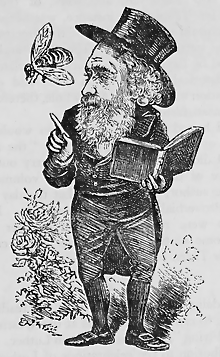

Given that ''Proverbial Philosophy'' was published by the author when he was a young man, who went on to live a long life and write prolifically, he was an easy target for satire from new generations and changing tastes – "Tupper's visage was everywhere ... His very generosity and omnipresence worked against him. By the 1870s, each week began to bring fresh pummelings by clever young men in humor magazines like '' Punch'', '' Figaro'' and ''The Comic''." Hudson (1949) quotes examples dating from 1864:

Once the satire was played out, Tupper's work was forgotten. , none of his works have been in print since the final edition of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' in 1881, although digital transcriptions and facsimiles can now be found.

Given that ''Proverbial Philosophy'' was published by the author when he was a young man, who went on to live a long life and write prolifically, he was an easy target for satire from new generations and changing tastes – "Tupper's visage was everywhere ... His very generosity and omnipresence worked against him. By the 1870s, each week began to bring fresh pummelings by clever young men in humor magazines like '' Punch'', '' Figaro'' and ''The Comic''." Hudson (1949) quotes examples dating from 1864:

Once the satire was played out, Tupper's work was forgotten. , none of his works have been in print since the final edition of ''Proverbial Philosophy'' in 1881, although digital transcriptions and facsimiles can now be found.

Influence on Walt Whitman

Renowned American poetWalt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

was an enthusiastic supporter of Tupper while acting as editor for the Brooklyn Eagle

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''Kings County Democrat'', later ''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle'' before shortening title further to ''Brooklyn Eagle'') was an afternoon daily newspaper published in the city ...

(1846–1848) – for example, in his 1847 review of ''Probabilities: An Aid to Faith'' he commends the work's "lofty ... august scope of intention! ... The author ... is one of the rare men of the time. He turns up thoughts as with a plough ... we should like well to go into this book ... but justice to it would require many pages." Contemporary readers noted similarities between ''Proverbial Philosophy'' and Whitman's writings (not always intending this to be a flattering comparison), and it seems likely that the work influenced the style of Whitman's ''Leaves of Grass

''Leaves of Grass'' is a poetry collection by American poet Walt Whitman. After self-publishing it in 1855, he spent most of his professional life writing, revising, and expanding the collection until his death in 1892. Either six or nine separa ...

'', although the two had many ideological differences. Coulombe (1996) suggests that Whitman also

In later years, however, Whitman distanced himself from Tupper; Tupper had by then become highly unfashionable, and Whitman was seeking to create a separate style of art for the New World: "His disagreement with Tupper, who considered the States as a literary adjunct to England, underscores his desire to create a distinctly American poetry." The influence from Britain continued, however, as Snodgrass (2008) notes that Whitman's style in later works such as Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking

"Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" by American poet Walt Whitman is one of his most complex and successfully integrated poems. Whitman used several new techniques in the poem. One is the use of images like bird, boy, sea. The influence of music ...

"was less influenced by homiletic writers such as Martin Tupper in favor of the more musical efforts of such poets as Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's ...

."

In other literature

W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most fam ...

alludes to Tupper in '' Bab Ballads''. In the poem ''Ferdinando and Elvira, or, The Gentle Pieman'' ( 1866), Gilbert describes how two lovers are trying to find out who has been putting mottoes into "paper crackers" (a sort of 19th Century fortune cookie

A fortune cookie is a crisp and sugary cookie wafer made from flour, sugar, vanilla, and sesame seed oil with a piece of paper inside, a "fortune", an aphorism, or a vague prophecy. The message inside may also include a Chinese language, Chines ...

). Gilbert builds up to the following lines, eventually coming up with a spoof of Tupper's own style from ''Proverbial Philosophy'':

Such was Tupper's fame that the 1933 ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which published its first editio ...

'' contains an entry ''Tupperian'': "Of, belonging to, or in the style of Martin F. Tupper's Proverbial Philosophy", or "An admirer of Tupper. So Tupperish ''a.'', Tupperism, Tupperize ''v.''". The entry attests references dating from 1858.

Awards and recognition

On 10 April 1845 Tupper was elected aFellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

on merit of being "the author of 'Proverbial Philosophy' and several other works", and "eminent as a literary Man, and for his Archaeological attainments". A key contribution to archaeology was his excavation of Farley Heath on Farley Green, Surrey, done piecemeal at periods between 1839 and 1847, and as an organised project in 1848, which uncovered a Romano-Celtic temple

A Romano-Celtic temple or is a sub-class of Roman temples which is found in the north-western Celtic provinces of the Roman Empire. It was the centre of worship in the Gallo-Roman religion. The architecture of Romano-Celtic temples differs from ...

as well as a number of "coins, brooches and other metal objects". Tupper's interpretation of what he found, however, was of questionable accuracy.

He received the 1844 Gold Medal for Science and Literature from the King of Prussia

The monarchs of Prussia were members of the House of Hohenzollern who were the hereditary rulers of the former German state of Prussia from its founding in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia. The Duchy had evolved out of the Teutonic Order, a Roman C ...

as a mark of the King's admiration for ''Proverbial Philosophy''.

Selected works

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * *Albury History Society

contains some details about Tupper's connection to Albury, Surrey {{DEFAULTSORT:Tupper, Martin Farquhar 1810 births 1889 deaths Fellows of the Royal Society Poets from London English male poets 19th-century English poets 19th-century English male writers Victorian poets People educated at Eagle House School People educated at Charterhouse School Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford 19th-century English novelists English male novelists Victorian novelists 19th-century English short story writers English male short story writers Victorian short story writers Novelists from London English historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in the Middle Ages English barristers 19th-century English essayists English male essayists 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights English male dramatists and playwrights English nonconformist hymnwriters English Protestants English archaeologists