Maritime history is the study of human interaction with and activity at sea. It covers a broad thematic element of

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

that often uses a global approach, although national and regional histories remain predominant. As an academic subject, it often crosses the boundaries of standard

discipline

Discipline is the self-control that is gained by requiring that rules or orders be obeyed, and the ability to keep working at something that is difficult. Disciplinarians believe that such self-control is of the utmost importance and enforce a ...

s, focusing on understanding humankind's various relationships to the oceans,

sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

s, and major

waterway

A waterway is any Navigability, navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other ways. A first distinction is ...

s of the globe.

Nautical history records and interprets past events involving ships, shipping, navigation, and seafarers.

Maritime history is the broad overarching subject that includes

fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment (Freshwater ecosystem, freshwater or Marine ecosystem, marine), but may also be caught from Fish stocking, stocked Body of water, ...

,

whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales for their products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that was important in the Industrial Revolution. Whaling was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16t ...

, international

maritime law

Maritime law or admiralty law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between pri ...

,

naval history

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river.

The Military, armed forces branch designated for naval warfare is a navy. Naval operations can be ...

, the history of

ship

A ship is a large watercraft, vessel that travels the world's oceans and other Waterway, navigable waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research and fishing. Ships are generally disti ...

s, ship design,

shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other Watercraft, floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation th ...

, the history of

navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

, the history of the various maritime-related sciences (

oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of to ...

,

cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

,

hydrography

Hydrography is the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers, as well as with the prediction of their change over time, for the primary ...

, etc.), sea exploration, maritime economics and trade,

shipping

Freight transport, also referred to as freight forwarding, is the physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo. The term shipping originally referred to transport by sea but in American English, it has been ...

,

yachting

Yachting is recreational boating activities using medium/large-sized boats or small ships collectively called yachts. Yachting is distinguished from other forms of boating mainly by the priority focus on comfort and luxury, the dependence on ma ...

,

seaside resort

A seaside resort is a city, resort town, town, village, or hotel that serves as a Resort, vacation resort and is located on a coast. Sometimes the concept includes an aspect of an official accreditation based on the satisfaction of certain requi ...

s, the history of

lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lens (optics), lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Ligh ...

s and aids to navigation, maritime themes in literature, maritime themes in art, the social history of

sailor

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship. While the term ''sailor'' ...

s and passengers and sea-related communities. There are a number of approaches to the field, sometimes divided into two broad categories: Traditionalists, who seek to engage a small audience of other academics, and Utilitarians, who seek to influence policy makers and a wider audience.

Historiography

Historians from many lands have published monographs, popular and scholarly articles, and collections of archival resources. A leading journal is ''International Journal of Maritime History'', a fully refereed scholarly journal published twice a year by the International Maritime Economic History Association. Based in Canada with an international editorial board, it explores the maritime dimensions of economic, social, cultural, and environmental history. For a broad overview, see the four-volume encyclopedia edited by

John B. Hattendorf, ''

Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History'' (Oxford, 2007). It contains over 900 articles by 400 scholars and runs 2900 pages. Other major reference resources are Spencer Tucker, ed., ''Naval Warfare: An International Encyclopedia'' (3 vol. ABC-CLIO, 2002) with 1500 articles in 1231, pages, and I. C. B. Dear and Peter Kemp, eds., ''Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea'' (2nd ed. 2005) with 2600 articles in 688 pages.

Typically, studies of merchant shipping and of defensive navies are seen as separate fields.

Inland waterway

A waterway is any navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other ways. A first distinction is necessary bet ...

s are included within 'maritime history,' especially inland seas such as the

Great Lakes of North America, and major navigable rivers and canals worldwide.

One approach to maritime history writing has been nicknamed 'rivet counting' because of a focus on the minutiae of the vessel. However, revisionist scholars are creating new turns in the study of maritime history. This includes a post-1980s turn towards the study of human users of ships (which involves sociology, cultural geography, gender studies and narrative studies); and post-2000 turn towards seeing sea travel as part of the wider history of transport and mobilities. This move is sometimes associated with

Marcus Rediker and

Black Atlantic studies, but most recently has emerged from the International Association for the History of Transport, Traffic and Mobilities (T2M).

:''See also'':

Historiography related articles below

Prehistoric times

Watercraft

A watercraft or waterborne vessel is any vehicle designed for travel across or through water bodies, such as a boat, ship, hovercraft, submersible or submarine.

Types

Historically, watercraft have been divided into two main categories.

*Raf ...

such as

raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is usually of basic design, characterized by the absence of a hull. Rafts are usually kept afloat by using any combination of buoyant materials such as wood, sealed barre ...

s and

boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size or capacity, its shape, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically used on inland waterways s ...

s have been used far into pre-historic times and possibly even by ''

Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' ( ) is an extinction, extinct species of Homo, archaic human from the Pleistocene, spanning nearly 2 million years. It is the first human species to evolve a humanlike body plan and human gait, gait, to early expansions of h ...

'' more than a million years ago crossing

strait

A strait is a water body connecting two seas or water basins. The surface water is, for the most part, at the same elevation on both sides and flows through the strait in both directions, even though the topography generally constricts the ...

s between landmasses.

Little evidence remains that would pinpoint when the first seafarer made their journey. We know, for instance, that a sea voyage had to have been made to reach Greater Australia (

Sahul) or more years ago. Functional maritime technology was required to progress between the many islands of

Wallacea

Wallacea is a biogeography, biogeographical designation for a group of mainly list of islands of Indonesia, Indonesian islands separated by deep-water straits from the Asian and Australia (continent), Australian continental shelf, continental ...

before making this crossing. We do not know what seafaring predated the milestone of the first settling of Australia.

One of the oldest known boats to be found is the

Pesse canoe, and carbon dating has estimated its construction from 8040 to 7510 BCE. The Pesse canoe is the oldest physical object that can date the use of watercraft, but the oldest depiction of a watercraft is from Norway. The rock art at

Valle, Norway depicts a carving of a more than 4 meter long boat and it is dated to be 10,000 to 11,000 years old.

Ancient times

Throughout history sailing has been instrumental in the development of civilization, affording humanity greater mobility than travel over land, whether for trade, transport or warfare, and the capacity for fishing. The earliest depiction of a maritime sailing vessel is from the

Ubaid period of

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

in the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, from around 3500 to 3000 BCE. These vessels were depicted in clay models and painted disks. They were made from bundled reeds encased in a lattice of ropes. Remains of

barnacle

Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass (taxonomy), subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacean, Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar Nauplius (larva), nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebra ...

-encrusted

bituminous

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American English, the m ...

amalgams have also been recovered, which are interpreted to have been part of the water-proof coating applied on these vessels. The depictions lack details, but an image of a vessel on a shard of pottery shows evidence of what could be bipod masts and a sail, which would make it the earliest known evidence of the use of such technology. The location of the sites indicate that the Ubaid culture was engaging in maritime trade with Neolithic Arabian cultures along the coasts of the Persian Gulf for high-value goods. Pictorial representation of sails are also known from

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, dated to circa 3100 BCE.

The earliest seaborne trading route, however, is known from the 7th millennium BCE in the

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. It involved the seaborne movement of

obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

by an unknown

Neolithic Europe

The European Neolithic is the period from the arrival of Neolithic (New Stone Age) technology and the associated population of Early European Farmers in Europe, (the approximate time of the first farming societies in Greece) until –1700 BC (t ...

seafaring people. The obsidian was mined from the volcanic island of

Milos and then transported to various parts of the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

,

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, and

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, where they were refined into obsidian blades. However, the nature of the seafaring technologies involved have not been preserved.

Austronesians

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesi ...

started a dispersal from Taiwan across

Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the Southeast Asian countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor.

The terms Island Southeast Asia and Insular Southeast Asia are sometimes given the same meaning as ...

around 3000 BCE. This started to spread into the islands of the Pacific , steadily advanced across the Pacific and culminated with the settlement of Hawaii , and New Zealand . Distinctive maritime technology was used for this, including the

lashed-lug boatbuilding technique, the

catamaran

A catamaran () (informally, a "cat") is a watercraft with two parallel hull (watercraft), hulls of equal size. The wide distance between a catamaran's hulls imparts stability through resistance to rolling and overturning; no ballast is requi ...

, and the

crab claw sail, together with extensive navigation techniques. This allowed them to colonize a large part of the

Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth. In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

region during the

Austronesian expansion

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesi ...

.

Prior to the 16th century

Colonial Era, Austronesians were the most widespread ethnolinguistic group, spanning half the planet from

Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

in the eastern Pacific Ocean to

Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

in the western

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

.

The

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ians had knowledge of

sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

construction. The

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

historian

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

states that

Necho II

Necho II (sometimes Nekau, Neku, Nechoh, or Nikuu; Greek: Νεκώς Β'; ) of Egypt was a king of the 26th Dynasty (610–595 BC), which ruled from Sais. Necho undertook a number of construction projects across his kingdom. In his reign, accor ...

sent out an expedition of

Phoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

, which in two and a half years sailed from the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

around Africa to the mouth of the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

. As they sailed south and then west, they observed that the mid-day sun was to the north. Their contemporaries did not believe them, but modern historians take this as evidence that they were south of the equator

as crossing the equator changes the angle of the sun resulting in the change of season.

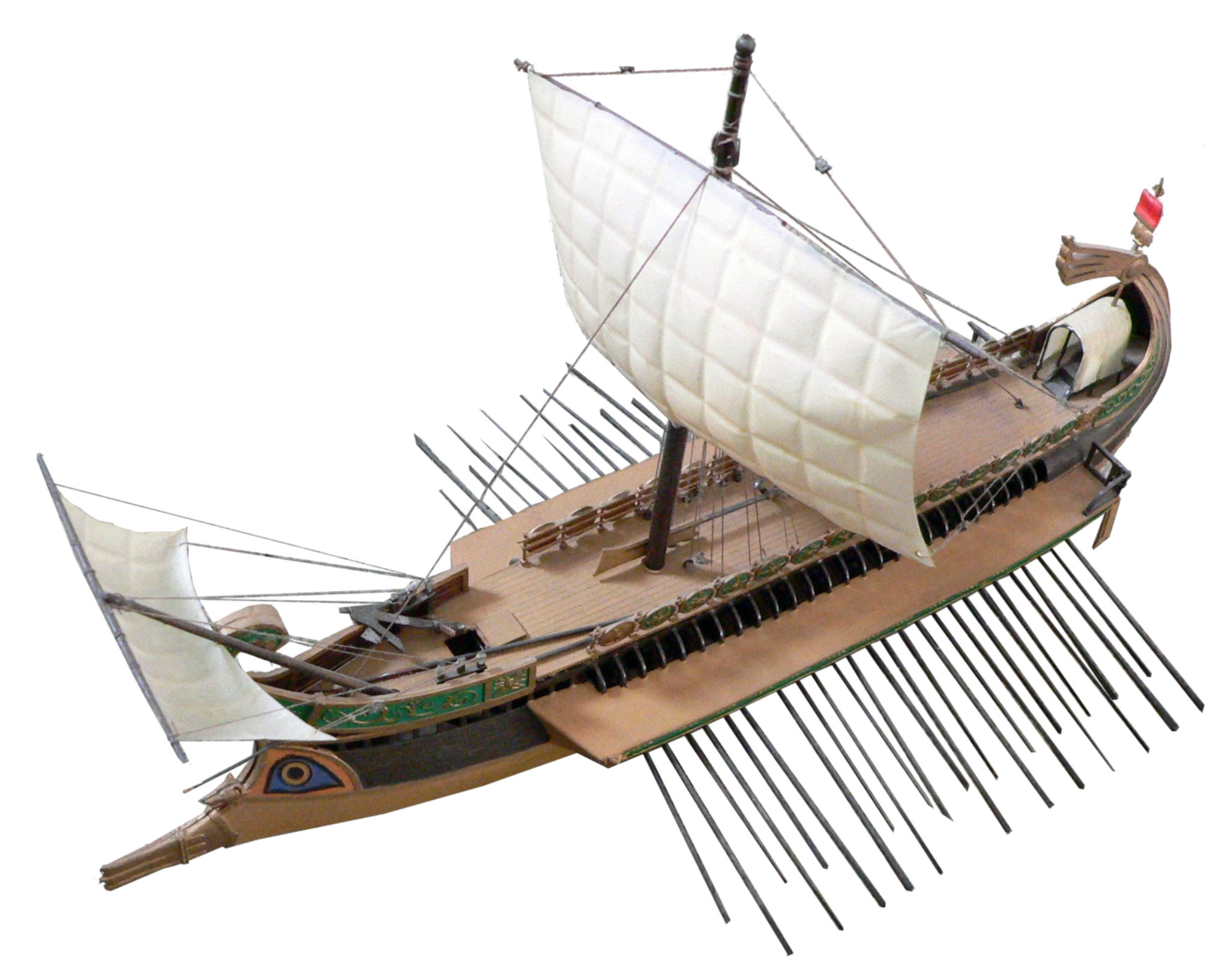

Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

had a variety of ships that played crucial roles in its

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

,

trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

, and transportation activities. Rome was preceded in the use of the sea by other ancient, seafaring

civilizations of the Mediterranean. The

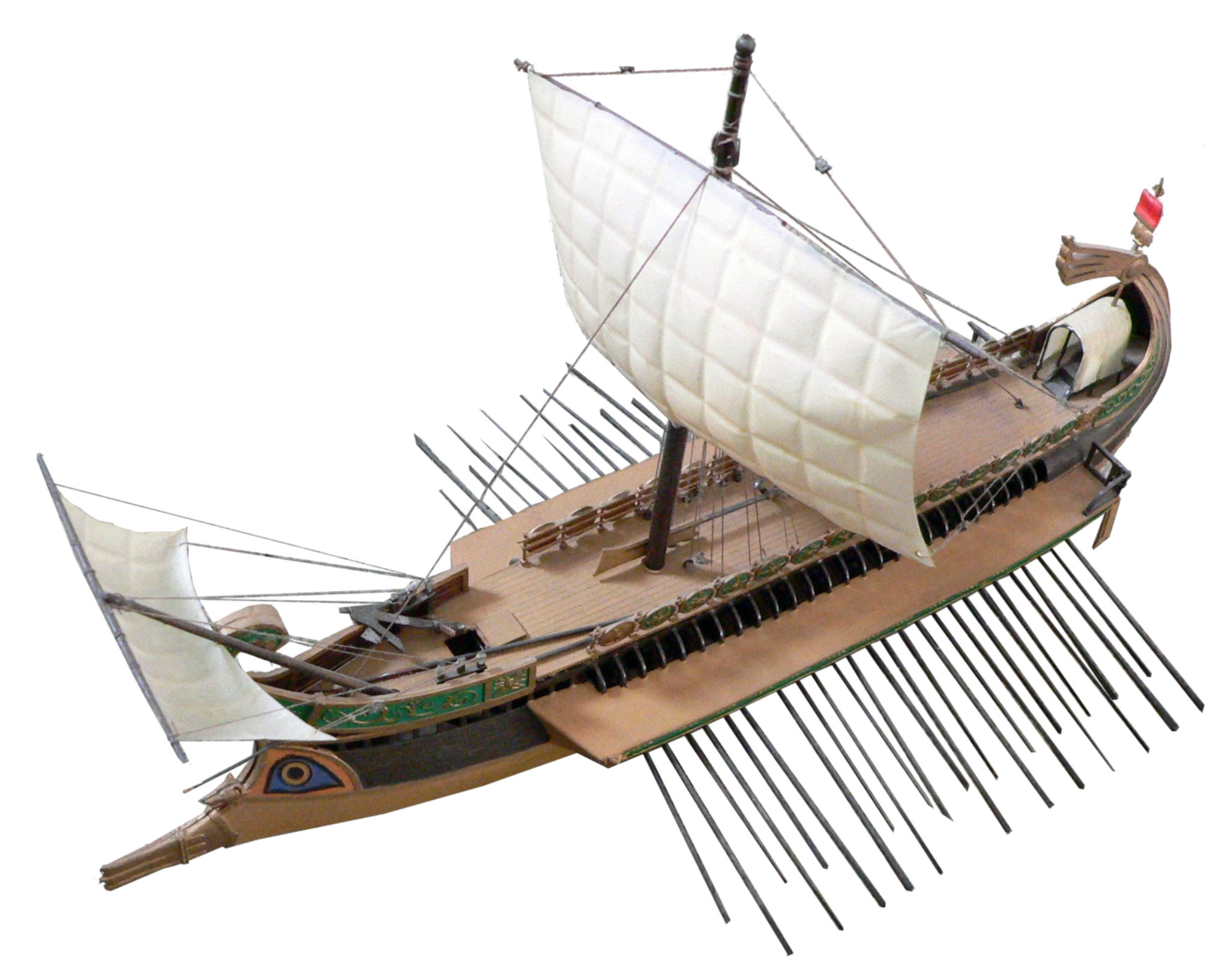

galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

was a long, narrow, highly maneuverable ship powered by oarsmen, sometimes stacked in multiple levels such as

biremes or

trireme

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and ancient R ...

s, and many of which also had sails. Initial efforts of the Romans to construct a war fleet were based on copies of Carthaginian warships. In the

Punic wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

in the mid-third century BCE, the Romans were at first outclassed by Carthage at sea, but by 256 BCE had drawn even and fought the wars to a stalemate. In 55 BCE

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

used warships and transport ships to

invade Britain. Numerous types of transport ships were used to carry foodstuffs or other trade goods around the Mediterranean, many of which did double duty and were pressed into service as warships or troop transports in time of war. Roman ships are named in different ways, often in compound expressions with the word . These are found in many ancient Roman texts, and named in different ways, such as by the appearance of the ship: for example, (covered ship); or by its function, for example: (commerce ship), or (plunder ship). Others, like (grain), (stones), and (live fish), are about the cargo. The

Althiburos mosaic in Tunisia lists many types of ships. The expression (lit. "long ships") is the plural of the noun phrase ("long ship"), following the rules for pluralization of feminine,

third declension

The third declension is a category of nouns in Latin and Greek with broadly similar case formation — diverse stems, but similar endings. Sanskrit also has a corresponding class (although not commonly termed as ''third''), in which the so-ca ...

nouns in Latin, and inflectional agreement of the adjective ''

longus

Longus, sometimes Longos (), was the author of an ancient Greek novel or romance, '' Daphnis and Chloe''. Nothing is known of his life; it is assumed that he lived on the isle of Lesbos (setting for ''Daphnis and Chloe'') during the 2nd centu ...

'' to match.

Age of navigation

By 1000 BCE, Austronesians in Island Southeast Asia were already engaging in regular maritime trade with China,

South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

, and the Middle East, introducing sailing technologies to these regions. They also facilitated an exchange of cultivated crop plants, introducing Pacific coconuts, bananas, and sugarcane to the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

, some of which eventually reached Europe via overland Persian and Arab traders.

A Chinese record in 200 AD describes one of the Austronesian ships, called

''kunlun bo'' or ''k'unlun po'' (崑崙舶, lit. "ship of the

Kunlun

The Kunlun Mountains constitute one of the longest mountain chains in Asia, extending for more than . In the broadest sense, the chain forms the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau south of the Tarim Basin. Located in Western China, the Kunlu ...

people"). It may also have been the "kolandiaphonta" known by the Greeks.

It has 4–7 masts and is able to sail against the wind due to the usage of

tanja sails. These ships reached as far as Madagascar by ca. 50–500 AD and

Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

in the eighth century AD.

Northern European

Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

also developed oceangoing vessels and depended heavily upon them for travel and population movements prior to 1000 AD, with the oldest known examples being

longship

Longships, a type of specialised Viking ship, Scandinavian warships, have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by th ...

s dated to around 190 AD from the

Nydam Boat site. In early modern India and

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

the

lateen

A lateen (from French ''latine'', meaning "Latin") or latin-rig is a triangular sail set on a long Yard (sailing) , yard mounted at an angle on the mast (sailing) , mast, and running in a fore-and-aft direction. The Settee (sail), settee can be ...

-sail ship known as the

dhow

Dhow (; ) is the generic name of a number of traditional sailing vessels with one or more masts with settee or sometimes lateen sails, used in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean region. Typically sporting long thin hulls, dhows are trading vessels ...

was used on the waters of the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Persian Gulf.

China started building sea-going ships in the 10th century during the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

. Chinese seagoing ship is based on

Austronesian ship designs which have been trading with the

Eastern Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

since the second century AD.

They purportedly reached massive sizes by the

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

in the 14th century, and by the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

, they were used by

Zheng He

Zheng He (also romanized Cheng Ho; 1371–1433/1435) was a Chinese eunuch, admiral and diplomat from the early Ming dynasty, who is often regarded as the greatest admiral in History of China, Chinese history. Born into a Muslims, Muslim famil ...

to send

expeditions to the Indian Ocean.

Water was the cheapest and usually the only way to transport goods in bulk over long distances. In addition, it was the safest way to transport commodities.

The long trade routes created popular trading ports called

Entrepôt

An entrepôt ( ; ) or transshipment port is a port, city, or trading post where merchandise may be imported, stored, or traded, usually to be exported again. Such cities often sprang up and such ports and trading posts often developed into comm ...

s.

There were three popular Entrepôts in Southeast Asia: the

Malaka in southwestern Malaya,

Hoi An in Vietnam, and

Ayuthaya in

Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

.

These super centers for trade were ethnically diverse, because ports served as a midpoint of voyages and trade rather than a destination.

The Entrepôts helped link the coastal cities to the "hempispheric trade nexus".

The increase in sea trade initiated a cultural exchange among traders.

From 1400 to 1600 the Chinese population doubled from 75 million to 150 million as a result of imported goods, this was known as the "age of commerce".

The

mariner's astrolabe

The mariner's astrolabe, also called sea astrolabe, was an inclinometer used to determine the latitude of a ship at sea by measuring the sun's noon altitude (declination) or the meridian altitude of a star of known declination. Not an astrolabe ...

was the chief tool of

Celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space or on the surface ...

in early modern maritime history. This scaled down version of the

instrument used by astronomers served as a navigational aid to measure latitude at sea, and was employed by

Portuguese sailors no later than 1481.

The precise date of the discovery of the magnetic needle compass is undetermined, but the earliest attestation of the device for

navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

was in the ''

Dream Pool Essays'' by

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and Art name#China, pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymath, scientist, and statesman of the Song dynasty (960� ...

(1088). Kuo was also the first to document the concept of

true north

True north is the direction along Earth's surface towards the place where the imaginary rotational axis of the Earth intersects the surface of the Earth on its Northern Hemisphere, northern half, the True North Pole. True south is the direction ...

to discern a compass'

magnetic declination

Magnetic declination (also called magnetic variation) is the angle between magnetic north and true north at a particular location on the Earth's surface. The angle can change over time due to polar wandering.

Magnetic north is the direction th ...

from the physical

North Magnetic Pole

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the Earth's magnetic field, planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic comp ...

. The earliest iterations of the compass consisted of a floating, magnetized lodestone needle that spun around in a water-filled bowl until it reached alignment with Earth's magnetic poles. Chinese sailors were using the "wet" compass to determine the southern cardinal direction no later than 1117. The first use of a magnetized needle for seafaring navigation in Europe was written of by

Alexander Neckham, circa 1190 AD. Around 1300 AD, the pivot-needle dry-box compass was invented in Europe; it pointed north, similar to the modern-day mariner's compass. In Europe the device also included a compass-card, which was later adopted by the Chinese through contact with

Japanese pirates in the 16th century.

The oldest known map is dated back to 12,000 BC; it was discovered in a Spanish cave by Pilar Utrilla.

The early maps were oriented with east at the top. This is believed to have begun in the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

.

Religion played a role in the drawing of maps. Countries that were predominantly Christian during the Middle Ages placed east at the top of the maps, in part due to Genesis, "the Lord God planted a garden toward the east in Eden".

This led to maps containing the image of Jesus Christ, and the garden of Eden at the top of maps.

The latitude and longitude coordinate tables were made with the sole purpose of praying towards

Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

.

The next progression of maps came with the

portolan chart

Portolan charts are nautical charts, first made in the 13th century in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean basin and later expanded to include other regions. The word ''portolan'' comes from the Italian language, Italian ''portolano'', meaning " ...

. This was the first type of map that labeled North at the top and was drawn proportionate to size. Landmarks were drawn in great detail.

Ships and vessels

Various ships were in use during the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

.

Jong, a type of large sailing ship from

Nusantara, was built using wooden dowels without iron nails and multiple planks to endure heavy seas.

The ''chuan'' (Chinese

Junk ship) design was both innovative and adaptable. Junk vessels employed

mat and batten style sails that could be raised and lowered in segments, as well varying angles.

The

longship

Longships, a type of specialised Viking ship, Scandinavian warships, have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by th ...

was a type of ship developed over a period of centuries and perfected by its most famous users, the

Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

, around the 9th century. The ships were

clinker-built

Clinker-built, also known as lapstrake-built, is a method of boat building in which the edges of longitudinal (lengthwise-running) hull (watercraft), hull planks overlap each other.

The technique originated in Northern Europe, with the first know ...

, using overlapping wooden strakes. The

knaar, a relative of the longship, was a type of cargo vessel. It differed from the longship in that it was larger and relied solely on its

square rigged sail for propulsion. The

cog was a design which is believed to have evolved from (or at least been influenced by) the longship, and was in wide use by the 12th century. It too used the clinker method of construction. The

caravel was a ship invented in

Islamic Iberia and used in the Mediterranean from the 13th century.

[John M. Hobson (2004), ''The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation'', p. 141, ]Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, . Unlike the longship and

cog, it used a

carvel method of construction. It could be either

square rigged (''Caravela Redonda'') or

lateen rigged (''Caravela Latina''). The

carrack was another type of ship invented in the Mediterranean in the 15th century. It was a larger vessel than the caravel. Columbus's ship, the , was a famous example of a carrack.

Arab age of discovery

The

Arab Empire maintained and expanded a wide trade network across parts of Asia, Africa and Europe. This helped establish the Arab Empire (including the

Rashidun

The Rashidun () are the first four caliphs () who led the Muslim community following the death of Muhammad: Abu Bakr (), Umar (), Uthman (), and Ali ().

The reign of these caliphs, called the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661), is considered i ...

,

Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

,

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 C ...

and

Fatimid caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

s) as the world's leading extensive economic power throughout the 8th–13th centuries according to the political scientist

John M. Hobson.

[John M. Hobson (2004), ''The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation'', pp. 29–30, ]Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, . The Belitung is the oldest discovered Arabic ship to reach the Asian sea, dating back over 1000 years.

Apart from the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

,

Tigris

The Tigris ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the eastern of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian Desert, Syrian and Arabia ...

and

Euphrates

The Euphrates ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of West Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia (). Originati ...

, navigable rivers in the Islamic regions were uncommon, so transport by sea was very important.

Islamic geography

Medieval Islamic geography and cartography refer to the study of geography and cartography in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age (variously dated between the 8th century and 16th century). Muslim scholars made advances to the map-mak ...

and navigational sciences were highly developed, making use of a magnetic

compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

and a rudimentary instrument known as a

kamal, used for

celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space or on the surface ...

and for measuring the

altitude

Altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum (geodesy), datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context (e.g., aviation, geometr ...

s and

latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

s of the

star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s. When combined with detailed maps of the period, sailors were able to sail across oceans rather than skirt along the coast. According to the political scientist John M. Hobson, the origins of the caravel ship, used for long-distance travel by the Spanish and Portuguese since the 15th century, date back to the ''qarib'' used by

Andalusian explorers by the 13th century.

Control of sea routes dictated the political and military power of the Islamic nation. The Islamic border spread from Spain to China. Maritime trade was used to link the vast territories that spanned the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

to the Indian Ocean (see also:

Indo-Mediterranean). The Arabs were among the first to sail the Indian Ocean. Long-distance trade allowed the movement of "armies, craftsmen, scholars, and pilgrims". Sea trade was an important factor not just for the coastal ports and cities like

Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

, but also for

Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

and

Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, which are further inland. Sea trade enabled the distribution of food and supplies to feed entire populations in the middle east. Long distance sea trade imported raw materials for building, luxury goods for the wealthy, and new inventions.

Hanseatic League

The

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

was an alliance of trading guilds that established and maintained a trade monopoly over the Baltic Sea, to a certain extent the North Sea, and most of Northern Europe for a time in the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period, between the 13th and 17th centuries. Historians generally trace the origins of the League to the foundation of the Northern German town of

Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

, established in 1158/1159 after the capture of the area from the Count of Schauenburg and Holstein by

Henry the Lion, the

Duke of Saxony. Exploratory trading adventures,

raid

RAID (; redundant array of inexpensive disks or redundant array of independent disks) is a data storage virtualization technology that combines multiple physical Computer data storage, data storage components into one or more logical units for th ...

s and

piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

had occurred earlier throughout the Baltic (see

Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

s)—the

sailor

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship. While the term ''sailor'' ...

s of

Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

sailed up rivers as far away as

Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( ; , ; ), also known simply as Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the oldest cities in Russia, being first mentioned in the 9th century. The city lies along the V ...

, for example—but the scale of international

economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

in the Baltic area remained insignificant before the growth of the Hanseatic League. German cities achieved domination of trade in the Baltic with striking speed over the next century, and Lübeck became a central node in all the seaborne trade that linked the areas around the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

and the Baltic Sea.

The 15th century saw the climax of Lübeck's hegemony. (

Visby

Visby () is an urban areas in Sweden, urban area in Sweden and the seat of Gotland Municipality in Gotland County on the island of Gotland with 24,330 inhabitants . Visby is also the episcopal see for the Diocese of Visby. The Hanseatic League, ...

, one of the midwives of the Hanseatic league in 1358, declined to become a member. Visby dominated trade in the Baltic before the Hanseatic league, and with its monopolistic ideology, suppressed the

Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

ic free-trade competition.) By the late 16th century, the League imploded and could no longer deal with its own internal struggles, the social and political changes that accompanied the

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, the rise of Dutch and English merchants, and the incursion of the

Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

upon its trade routes and upon the Holy Roman Empire itself. Only nine members attended the last formal meeting in 1669 and only three (Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen) remained as members until its final demise in 1862.

Italian maritime republics

The

maritime republics

The maritime republics (), also called merchant republics (), were Italian Thalassocracy , thalassocratic Port city, port cities which, starting from the Middle Ages, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity brought about by their mar ...

, also called merchant republics, were Italian

thalassocratic port cities which, starting from the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity brought about by their maritime activities. The term, coined during the 19th century, generally refers to four Italian cities, whose coats of arms have been shown since 1947 on the flags of the

Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

and the Italian Merchant Navy:

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

,

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

,

Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, and

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. In addition to the four best known cities,

Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

,

[Peris Persi, in ''Conoscere l'Italia'', vol. Marche, Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara 1982 (p. 74); AA.VV. ''Meravigliosa Italia, Enciclopedia delle regioni'', edited by Valerio Lugoni, Aristea, Milano; Guido Piovene, in ''Tuttitalia'', Casa Editrice Sansoni, Firenze & Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara (p. 31); Pietro Zampetti, in ''Itinerari dell'Espresso'', vol. Marche, edited by Neri Pozza, Editrice L'Espresso, Rome, 1980] Gaeta

Gaeta (; ; Southern Latian dialect, Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a seaside resort in the province of Latina in Lazio, Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The city has played ...

,

Noli, and, in

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

,

Ragusa, are also considered maritime republics; in certain historical periods, they had no secondary importance compared to some of the better known cities.

Uniformly scattered across the Italian peninsula, the maritime republics were important not only for the history of navigation and commerce: in addition to precious goods otherwise unobtainable in Europe, new artistic ideas and news concerning distant countries also spread. From the 10th century, they built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, giving them an essential role in reestablishing contacts between

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

,

Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, and

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, which had been interrupted during the early Middle Ages. They also had an essential role in the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

and produced renowned explorers and navigators such as

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

and

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

.

Over the centuries, the maritime republics—both the best known and the lesser known but not always less important—experienced fluctuating fortunes. In the 9th and 10th centuries, this phenomenon began with Amalfi and Gaeta, which soon reached their heyday. Meanwhile, Venice began its gradual ascent, while the other cities were still experiencing the long gestation that would lead them to their autonomy and to follow up on their seafaring vocation. After the 11th century, Amalfi and Gaeta declined rapidly, while Genoa and Venice became the most powerful republics. Pisa followed and experienced its most flourishing period in the 13th century, and Ancona and Ragusa allied to resist Venetian power. Following the 14th century, while Pisa declined to the point of losing its autonomy, Venice and Genoa continued to dominate navigation, followed by Ragusa and Ancona, which experienced their golden age in the 15th century. In the 16th century, with Ancona's loss of autonomy, only the republics of Venice, Genoa, and Ragusa remained, which still experienced great moments of splendor until the mid-17th century, followed by over a century of slow decline that ended with the

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

ic invasion.

The maritime republics reestablished contacts between Europe, Asia and Africa, which were almost interrupted after the

fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

; their history is intertwined both with the launch of European expansion towards the East and with the origins of modern

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

as a mercantile and financial system. In these cities,

gold coin

A gold coin is a coin that is made mostly or entirely of gold. Most gold coins minted since 1800 are 90–92% gold (22fineness#Karat, karat), while most of today's gold bullion coins are pure gold, such as the Britannia (coin), Britannia, Canad ...

s, which had not been used for centuries, were minted, new exchange and accounting practices were developed, and thus international finance and

commercial law

Commercial law (or business law), which is also known by other names such as mercantile law or trade law depending on jurisdiction; is the body of law that applies to the rights, relations, and conduct of Legal person, persons and organizations ...

were born.

Technological advances in

navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

were also encouraged; important in this regard was the improvement and diffusion of the

compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

by the Amalfi people and the Venetian invention of the

great galley. Navigation owes much to the maritime republics as regards

nautical cartography: the maps of the 14th and 15th centuries that are still in use today all belong to the schools of Genoa, Venice, and Ancona.

From the East, the maritime republics imported a vast range of goods unobtainable in Europe, which they then resold in other cities of Italy and central and northern Europe, creating a commercial triangle between the Arab East, the Byzantine Empire, and Italy. Until the

discovery of America they were therefore essential nodes of trade between Europe and the other continents.

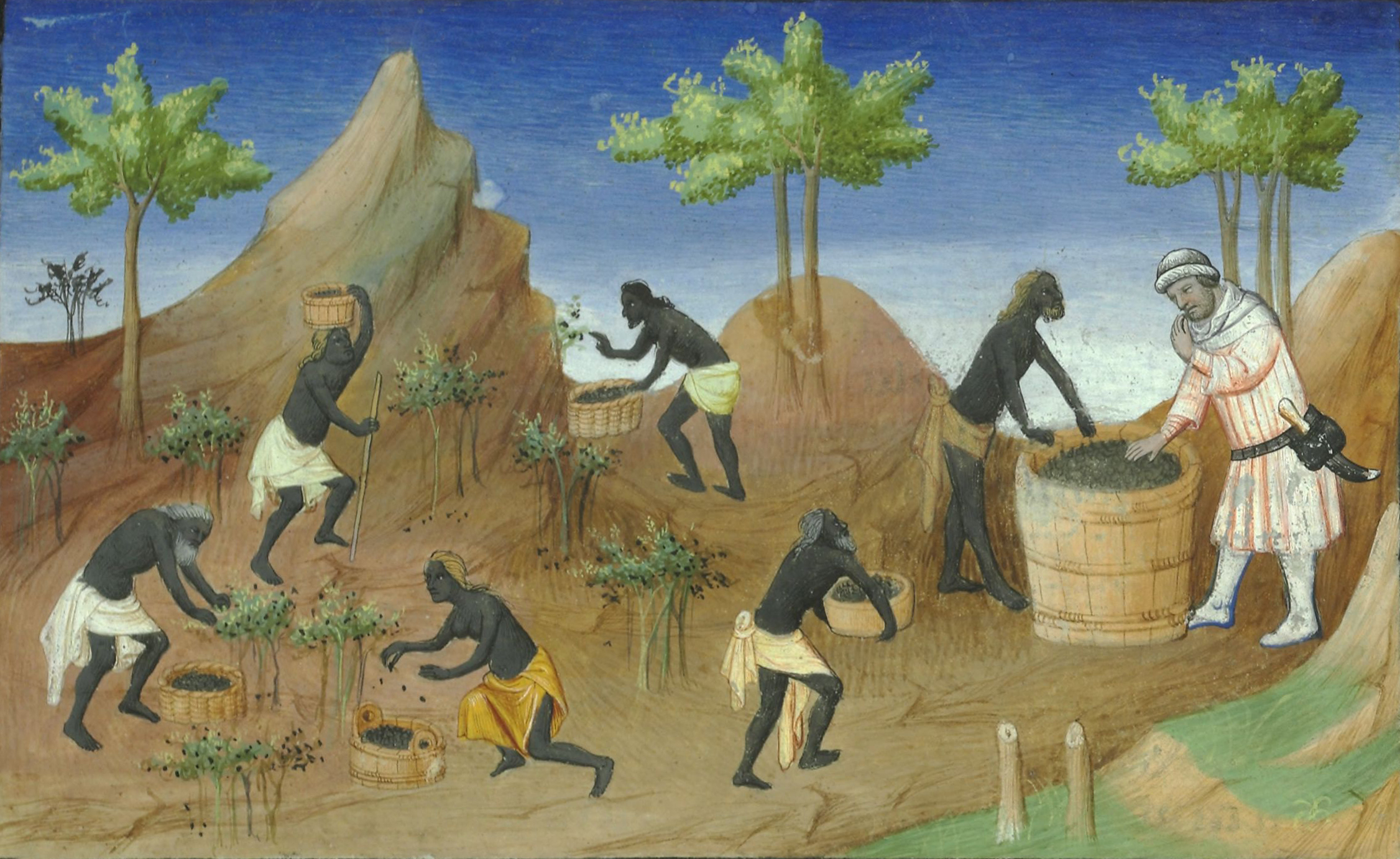

Among the most important products were:

*Medicines:

aloe vera

''Aloe vera'' () is a succulent plant species of the genus ''Aloe''. It is widely distributed, and is considered an invasive species in many world regions.

An evergreen perennial plant, perennial, it originates from the Arabian Peninsula, but ...

,

balsam,

ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is an herbaceous perennial that grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of l ...

,

camphor

Camphor () is a waxy, colorless solid with a strong aroma. It is classified as a terpenoid and a cyclic ketone. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel (''Cinnamomum camphora''), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the kapu ...

,

laudanum,

cardamom

Cardamom (), sometimes cardamon or cardamum, is a spice made from the seeds of several plants in the genus (biology), genera ''Elettaria'' and ''Amomum'' in the family Zingiberaceae. Both genera are native to the Indian subcontinent and Indon ...

,

rhubarb,

astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

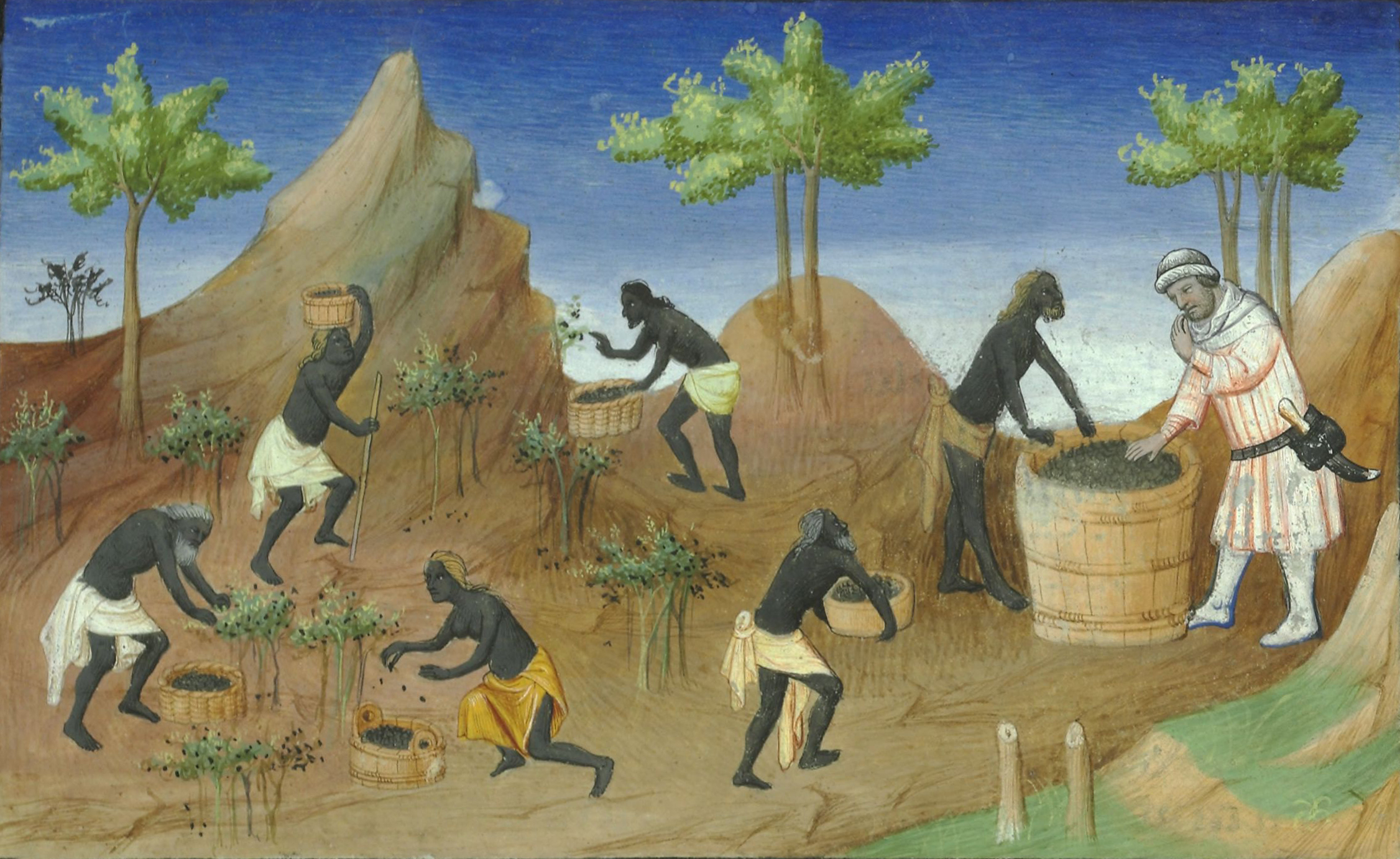

*

Spice

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

s:

black pepper

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diameter ...

,

clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands, or Moluccas, in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring, or Aroma compound, fragrance in fin ...

s,

nutmeg

Nutmeg is the seed, or the ground spice derived from the seed, of several tree species of the genus '' Myristica''; fragrant nutmeg or true nutmeg ('' M. fragrans'') is a dark-leaved evergreen tree cultivated for two spices derived from its fru ...

,

cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus ''Cinnamomum''. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, biscuits, b ...

,

white sugar

White sugar, also called table sugar, granulated sugar, or regular sugar, is a commonly used type of sugar, made either of beet sugar or cane sugar, which has undergone a refining process. It is nearly pure sucrose.

Description

The refini ...

*Perfumes and odorous substances to burn:

musk,

mastic,

sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus ''Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods. Sanda ...

,

incense

Incense is an aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremonial reasons. It ...

,

ambergris

*Dyes:

indigo

InterGlobe Aviation Limited (d/b/a IndiGo), is an India, Indian airline headquartered in Gurgaon, Haryana, India. It is the largest List of airlines of India, airline in India by passengers carried and fleet size, with a 64.1% domestic market ...

,

alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double salt, double sulfate salt (chemistry), salt of aluminium with the general chemical formula, formula , such that is a valence (chemistry), monovalent cation such as potassium ...

,

carmine

Carmine ()also called cochineal (when it is extracted from the Cochineal, cochineal insect), cochineal extract, crimson Lake pigment, lake, or carmine lake is a pigment of a bright-red color obtained from the aluminium coordination complex, compl ...

,

varnish

Varnish is a clear Transparency (optics), transparent hard protective coating or film. It is not to be confused with wood stain. It usually has a yellowish shade due to the manufacturing process and materials used, but it may also be pigmente ...

*Textiles:

silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

, Egyptian

linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong and absorbent, and it dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. Lin ...

,

sambe,

brocade

Brocade () is a class of richly decorative shuttle (weaving), shuttle-woven fabrics, often made in coloured silks and sometimes with gold and silver threads. The name, related to the same root as the word "broccoli", comes from Italian langua ...

,

velvet

Velvet is a type of woven fabric with a dense, even pile (textile), pile that gives it a distinctive soft feel. Historically, velvet was typically made from silk. Modern velvet can be made from silk, linen, cotton, wool, synthetic fibers, silk ...

,

damask

Damask (; ) is a woven, Reversible garment, reversible patterned Textile, fabric. Damasks are woven by periodically reversing the action of the warp and weft threads. The pattern is most commonly created with a warp-faced satin weave and the gro ...

,

carpet

A carpet is a textile floor covering typically consisting of an upper layer of Pile (textile), pile attached to a backing. The pile was traditionally made from wool, but since the 20th century synthetic fiber, synthetic fibres such as polyprop ...

s

*Luxury products:

gemstone

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, semiprecious stone, or simply gem) is a piece of mineral crystal which, when cut or polished, is used to make jewellery, jewelry or other adornments. Certain Rock (geology), rocks (such ...

s,

precious coral,

pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s,

ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

,

porcelain

Porcelain (), also called china, is a ceramic material made by heating Industrial mineral, raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to oth ...

,

gold and silver threads

The maritime republics' great prosperity deriving from trade had a significant impact on the history of art, to the point that five of them (Amalfi, Genoa, Venice, Pisa and Ragusa) are today included in

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

's list of

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

s. Although an artistic current common to all of them and exclusive to them cannot be described, a characterizing trait was the mixture of elements of the various Mediterranean artistic traditions, mainly

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

,

Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

and

Romanesque elements.

The modern

Italian communities living in Greece, Turkey,

Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

,

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, and

Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

descend, at least in part, from the colonies of the maritime republics, as well as the

language island of the

Tabarchino dialect in

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and the extinct

Italian community of Odesa.

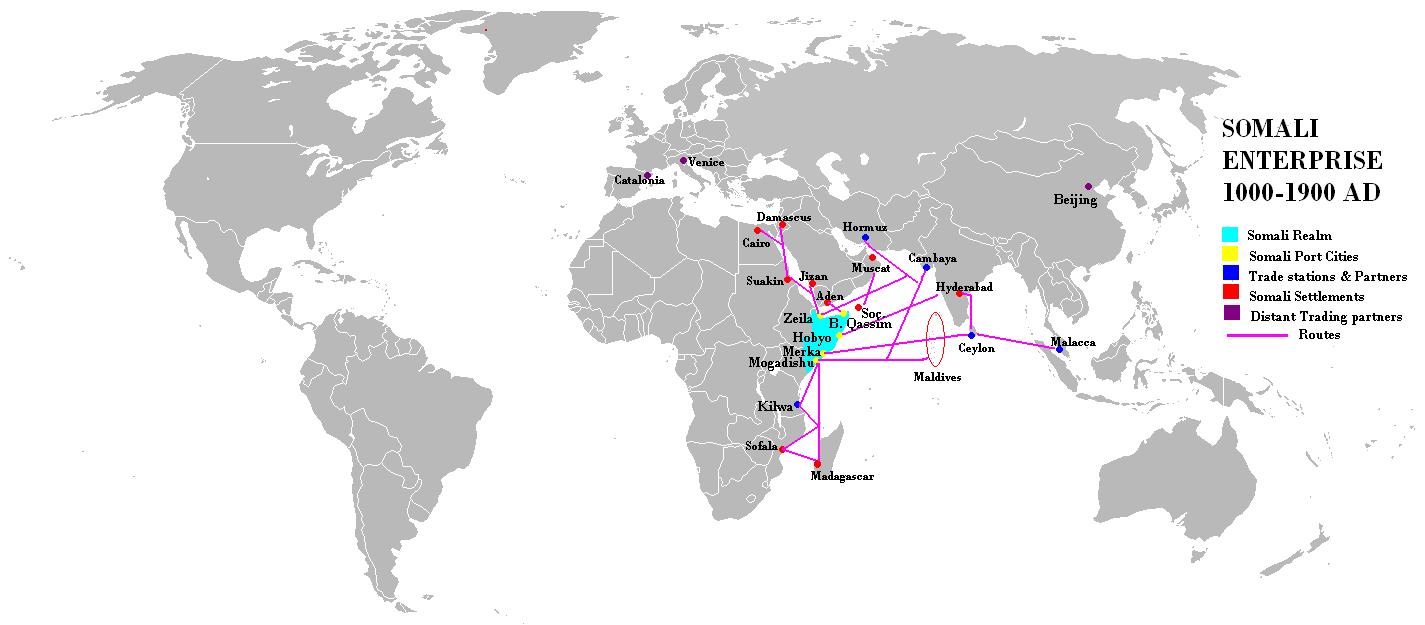

Somali maritime enterprise

During the

Age of the Ajuran, the Somali

sultanates and

republics

A republic, based on the Latin phrase '' res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a state in which political power rests with the public (people), typically through their representatives—in contrast to a monarchy. Although ...

of

Merca,

Mogadishu

Mogadishu, locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Ocean for millennia and has ...

,

Barawa,

Hobyo and their respective ports flourished. They had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India,

Venetia,

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China. In the 16th century,

Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the

Kingdom of Cambaya in what is modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with

cloths and

spice

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

s, for which they in return received gold,

wax and

ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat,

wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

,

barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.

In the

early modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

period, successor states of the

Adal and

Ajuran empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

s began to flourish in Somalia who continued the seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires. The rise of the 19th century

Gobroon dynasty in particular saw a rebirth in Somali maritime enterprise. During this period, the Somali agricultural output to

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

n markets was so great that the coast of Somalia came to be known as the ''Grain Coast'' of

Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

and

Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

.

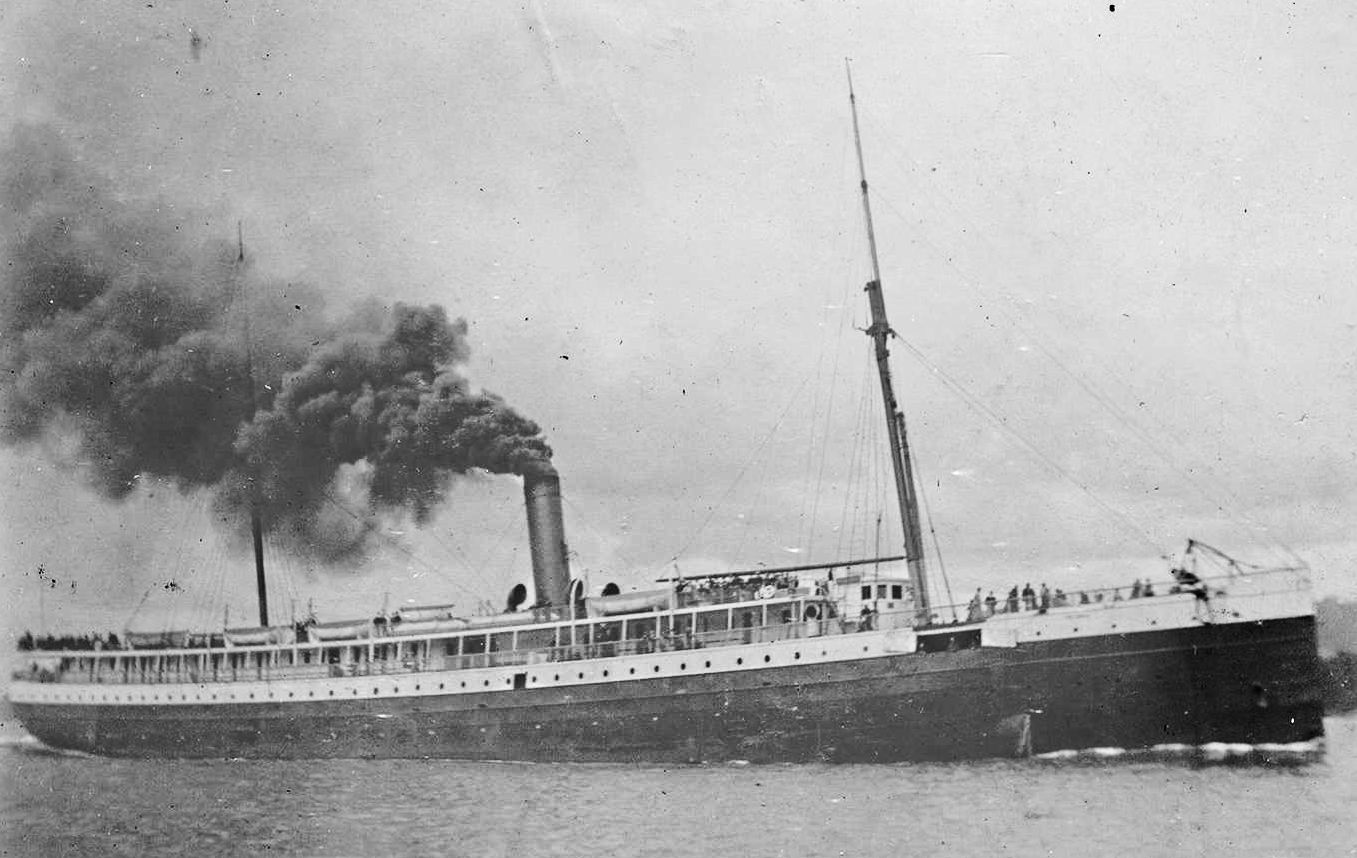

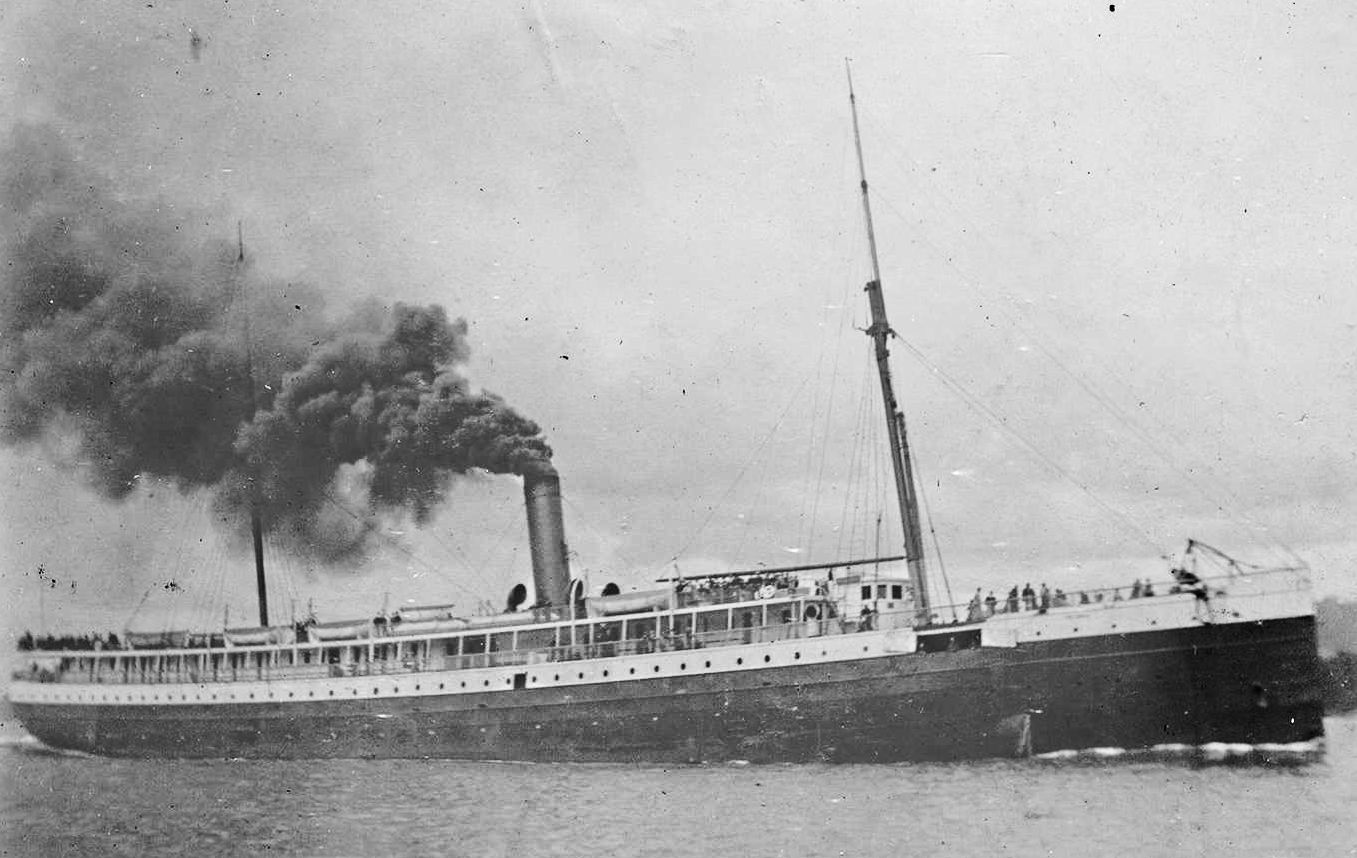

Age of Discovery

The ''

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

'' was a period from the early 15th century and continuing into the early 17th century, during which European ships traveled around the world to search for new trading routes after the

Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

. Historians often refer to the 'Age of Discovery' as the pioneer Portuguese and later Spanish long-distance maritime travels in search of alternative

trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over land or water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a singl ...

s to "

the East Indies", moved by the trade of gold,

silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

and

spice