marine biogeochemical cycles on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marine biogeochemical cycles are

''OpenStax'', 9 May 2019. Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

The six aforementioned elements are used by organisms in a variety of ways. Hydrogen and oxygen are found in water and organic molecules, both of which are essential to life. Carbon is found in all organic molecules, whereas nitrogen is an important component of nucleic acids and proteins. Phosphorus is used to make nucleic acids and the phospholipids that comprise biological membranes. Sulfur is critical to the three-dimensional shape of proteins. The cycling of these elements is interconnected. For example, the movement of water is critical for leaching sulfur and phosphorus into rivers which can then flow into oceans. Minerals cycle through the biosphere between the biotic and abiotic components and from one organism to another.Fisher M. R. (Ed.) (2019) ''Environmental Biology''

3.2 Biogeochemical Cycles

OpenStax. Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Water is the medium of the oceans, the medium which carries all the substances and elements involved in the marine biogeochemical cycles.

Water as found in nature almost always includes dissolved substances, so water has been described as the "universal solvent" for its ability to dissolve so many substances. This ability allows it to be the "

Water is the medium of the oceans, the medium which carries all the substances and elements involved in the marine biogeochemical cycles.

Water as found in nature almost always includes dissolved substances, so water has been described as the "universal solvent" for its ability to dissolve so many substances. This ability allows it to be the "

''NOAA''. Last updated: 26 February 2021. Evaporation of ocean water and formation of sea ice further increase the salinity of the ocean. However these processes which increase salinity are continually counterbalanced by processes that decrease salinity, such as the continuous input of fresh water from rivers, precipitation of rain and snow, and the melting of ice.Salinity

''NASA''. Last updated: 7 April 2021. The two most prevalent ions in seawater are chloride and sodium. Together, they make up around 85 percent of all dissolved ions in the ocean. Magnesium and sulfate ions make up most of the rest. Salinity varies with temperature, evaporation, and precipitation. It is generally low at the equator and poles, and high at mid-latitudes.

File:Vertical differences in ocean salinity (0 to 300m).png, Vertical differences in sea salinity between the surface and a depth of 300 metres. Salinity increases with depth in red regions and decreases in blue regions.Sundby, S. and Kristiansen, T. (2015) "The principles of buoyancy in marine fish eggs and their vertical distributions across the world oceans". ''PLOS ONE'', 10(10): e0138821. .  Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

File:SeaSurfaceSalinity.jpg, Annual mean sea surface salinity, measured in 2009 in practical salinity units

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in

Solar radiation affects the oceans: warm water from the Equator tends to circulate toward the poles, while cold polar water heads towards the Equator. The surface currents are initially dictated by surface wind conditions. The

Solar radiation affects the oceans: warm water from the Equator tends to circulate toward the poles, while cold polar water heads towards the Equator. The surface currents are initially dictated by surface wind conditions. The

Box models are widely used to model biogeochemical systems. Box models are simplified versions of complex systems, reducing them to boxes (or storage

Box models are widely used to model biogeochemical systems. Box models are simplified versions of complex systems, reducing them to boxes (or storage

The diagram above shows a simplified budget of ocean carbon flows. It is composed of three simple interconnected box models, one for the

The diagram above shows a simplified budget of ocean carbon flows. It is composed of three simple interconnected box models, one for the

The nitrogen cycle is as important in the ocean as it is on land. While the overall cycle is similar in both cases, there are different players and modes of transfer for nitrogen in the ocean. Nitrogen enters the ocean through precipitation, runoff, or as N2 from the atmosphere. Nitrogen cannot be utilized by

The nitrogen cycle is as important in the ocean as it is on land. While the overall cycle is similar in both cases, there are different players and modes of transfer for nitrogen in the ocean. Nitrogen enters the ocean through precipitation, runoff, or as N2 from the atmosphere. Nitrogen cannot be utilized by

A

A

''Earth in the Future'', PenState/NASSA. Retrieved 18 June 2020. The process of cycling nutrients in the sea starts with biological pumping, when nutrients are extracted from surface waters by phytoplankton to become part of their organic makeup. Phytoplankton are either eaten by other organisms, or eventually die and drift down as

File:Nutrient-cycle hg.png, Ocean

"Another critical element for the health of the oceans is the dissolved oxygen content. Oxygen in the surface ocean is continuously added across the air-sea interface as well as by photosynthesis; it is used up in respiration by marine organisms and during the decay or oxidation of organic material that rains down in the ocean and is deposited on the ocean bottom. Most organisms require oxygen, thus its depletion has adverse effects for marine populations. Temperature also affects oxygen levels as warm waters can hold less dissolved oxygen than cold waters. This relationship will have major implications for future oceans, as we will see... The final seawater property we will consider is the content of dissolved . is nearly opposite to oxygen in many chemical and biological processes; it is used up by plankton during photosynthesis and replenished during respiration as well as during the oxidation of organic matter. As we will see later, content has importance for the study of deep-water aging."

*

*

The

The  Iron is an essential micronutrient for almost every life form. It is a key component of hemoglobin, important to nitrogen fixation as part of the

Iron is an essential micronutrient for almost every life form. It is a key component of hemoglobin, important to nitrogen fixation as part of the

With its close relation to the

With its close relation to the

"Biological activity is a dominant force shaping the chemical structure and evolution of the earth surface environment. The presence of an oxygenated atmosphere-hydrosphere surrounding an otherwise highly reducing solid earth is the most striking consequence of the rise of life on earth. Biological evolution and the functioning of ecosystems, in turn, are to a large degree conditioned by geophysical and geological processes. Understanding the interactions between organisms and their abiotic environment, and the resulting coupled evolution of the biosphere and geosphere is a central theme of research in biogeology. Biogeochemists contribute to this understanding by studying the transformations and transport of chemical substrates and products of biological activity in the environment."Van Cappellen, P. (2003) "Biomineralization and global biogeochemical cycles". ''Reviews in mineralogy and geochemistry'', 54(1): 357–381. .

"Since the Cambrian explosion, mineralized body parts have been secreted in large quantities by biota. Because calcium carbonate, silica and calcium phosphate are the main mineral phases constituting these hard parts, biomineralization plays an important role in the global biogeochemical cycles of carbon, calcium, silicon and phosphorus"

"Biological activity is a dominant force shaping the chemical structure and evolution of the earth surface environment. The presence of an oxygenated atmosphere-hydrosphere surrounding an otherwise highly reducing solid earth is the most striking consequence of the rise of life on earth. Biological evolution and the functioning of ecosystems, in turn, are to a large degree conditioned by geophysical and geological processes. Understanding the interactions between organisms and their abiotic environment, and the resulting coupled evolution of the biosphere and geosphere is a central theme of research in biogeology. Biogeochemists contribute to this understanding by studying the transformations and transport of chemical substrates and products of biological activity in the environment."Van Cappellen, P. (2003) "Biomineralization and global biogeochemical cycles". ''Reviews in mineralogy and geochemistry'', 54(1): 357–381. .

"Since the Cambrian explosion, mineralized body parts have been secreted in large quantities by biota. Because calcium carbonate, silica and calcium phosphate are the main mineral phases constituting these hard parts, biomineralization plays an important role in the global biogeochemical cycles of carbon, calcium, silicon and phosphorus"

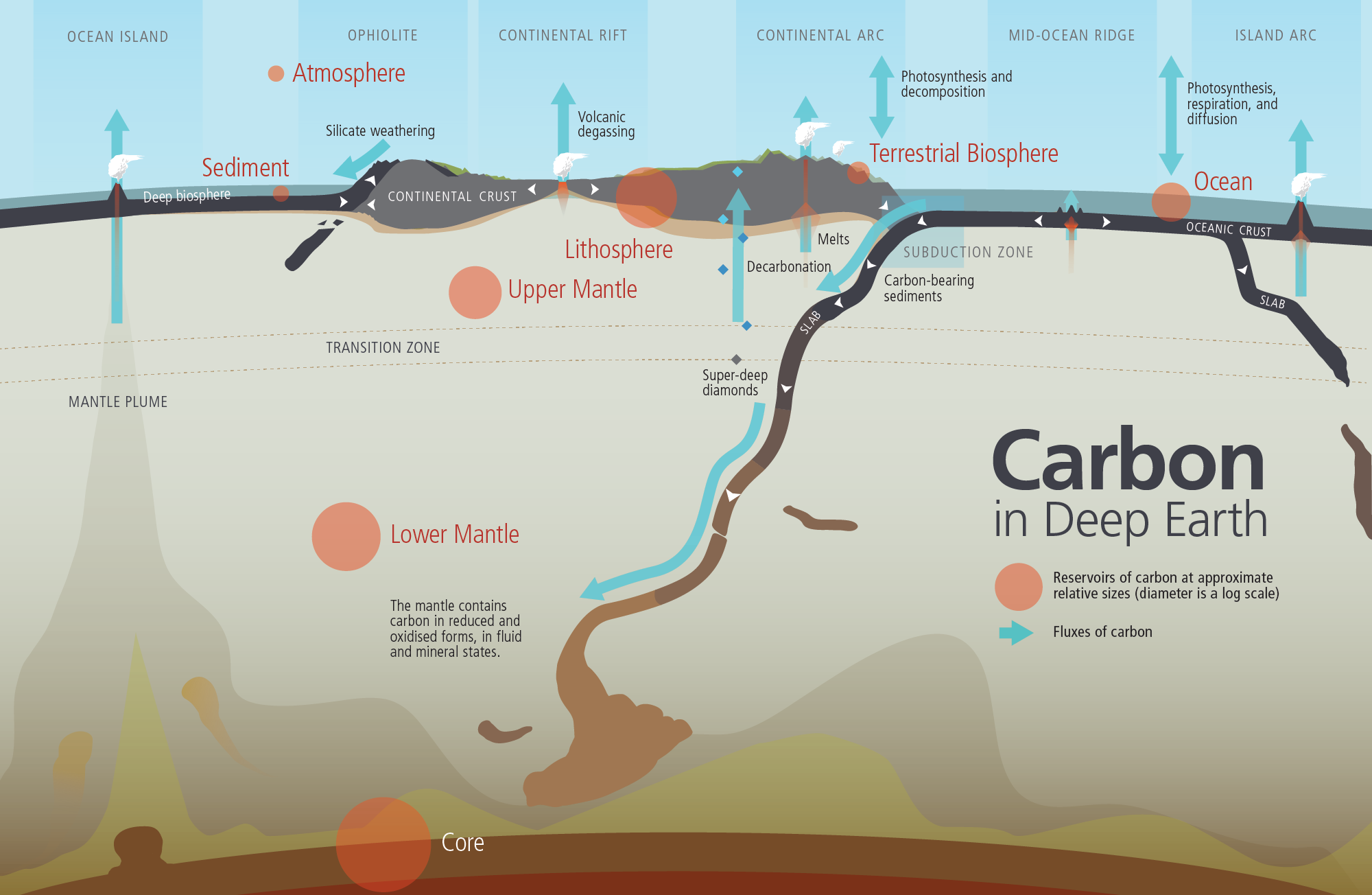

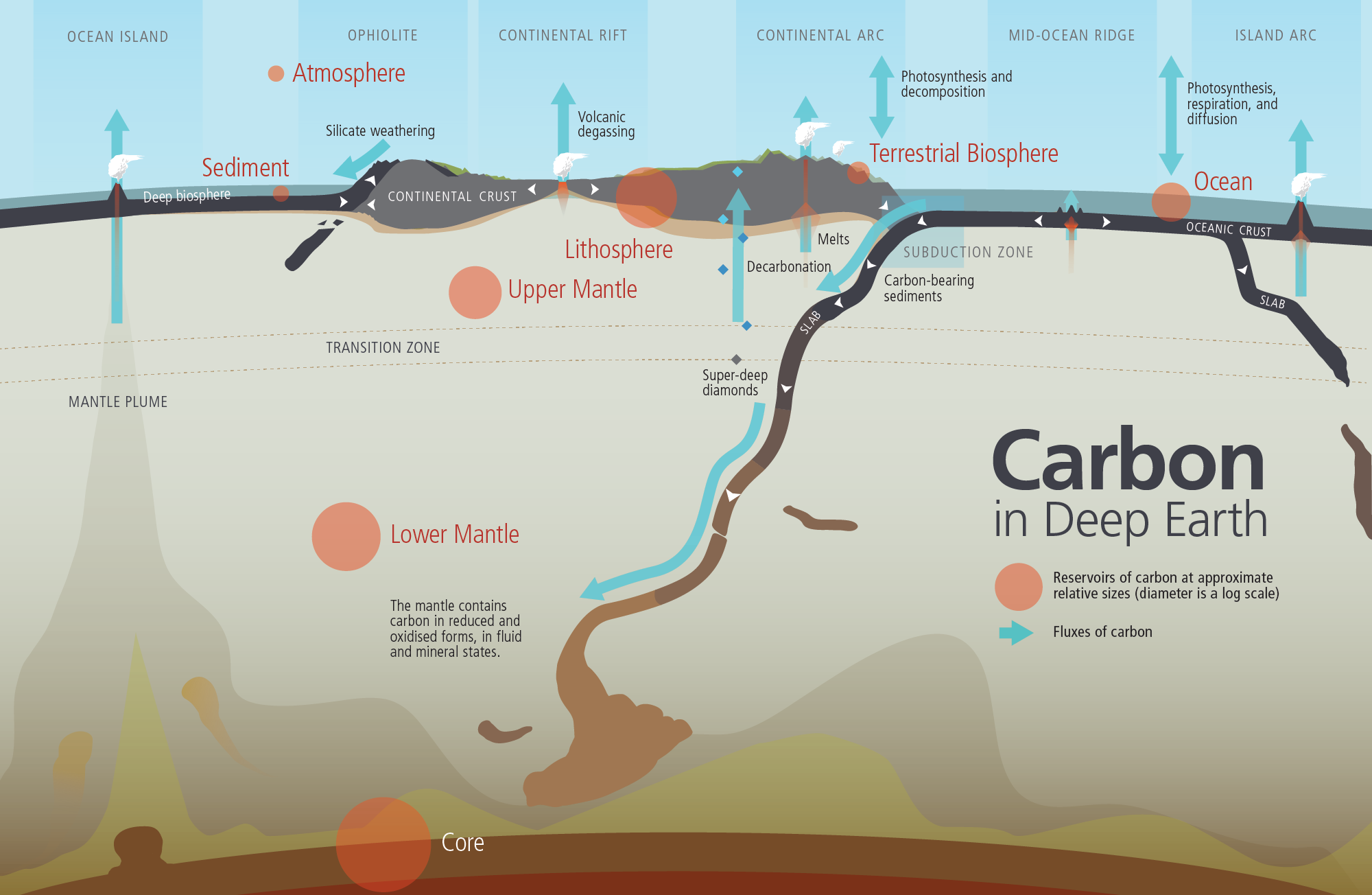

Deep cycling involves the exchange of materials with the

Deep cycling involves the exchange of materials with the  The conventional view of the ocean's origin is that it was filled by outgassing from the mantle in the early

The conventional view of the ocean's origin is that it was filled by outgassing from the mantle in the early

''Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade, 1990–1999''

Tulsa, Okla.:

File:Lead Cycle.jpg,

File:MercuryFoodChain.svg,

Such as trace minerals, micronutrients, human-induced cycles for synthetic compounds such as

''Marine Biogeochemical Cycles''

Butterworth-Heinemann. . {{biogeochemical cycle, state=expanded Biogeochemical cycle Geochemistry Biogeography Marine organisms Oceanography

biogeochemical cycle

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and th ...

s that occur within marine environments

Marine habitats are habitats that support marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or environmental a ...

, that is, in the saltwater

Saline water (more commonly known as salt water) is water that contains a high concentration of dissolved salts (mainly sodium chloride). On the United States Geological Survey (USGS) salinity scale, saline water is saltier than brackish water, ...

of seas or oceans or the brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estua ...

water of coastal estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environme ...

. These biogeochemical cycles are the pathways chemical substance

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wit ...

s and elements move through within the marine environment. In addition, substances and elements can be imported into or exported from the marine environment. These imports and exports can occur as exchanges with the atmosphere above, the ocean floor below, or as runoff from the land.

There are biogeochemical cycles for the elements calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar ...

, carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

, hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

, mercury, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

, selenium

Selenium is a chemical element with the symbol Se and atomic number 34. It is a nonmetal (more rarely considered a metalloid) with properties that are intermediate between the elements above and below in the periodic table, sulfur and tellurium, ...

, and sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

; molecular cycles for water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

and silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is ...

; macroscopic cycles such as the rock cycle

The rock cycle is a basic concept in geology that describes transitions through geologic time among the three main rock types: sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. Each rock type is altered when it is forced out of its equilibrium conditi ...

; as well as human-induced cycles for synthetic compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyl

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are highly carcinogenic chemical compounds, formerly used in industrial and consumer products, whose production was banned in the United States by the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976, Toxic Substances Contro ...

(PCB). In some cycles there are reservoirs where a substance can be stored for a long time. The cycling of these elements is interconnected.

Marine organisms

Marine life, sea life, or ocean life is the plants, animals and other organisms that live in the salt water of seas or oceans, or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. At a fundamental level, marine life affects the nature of the planet. ...

, and particularly marine microorganisms

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism (or microbe) is any microscopic livin ...

are crucial for the functioning of many of these cycles. The forces driving biogeochemical cycles include metabolic processes within organisms, geological processes involving the earth's mantle, as well as chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking ...

s among the substances themselves, which is why these are called biogeochemical cycles. While chemical substances can be broken down and recombined, the chemical elements themselves can be neither created nor destroyed by these forces, so apart from some losses to and gains from outer space, elements are recycled or stored (sequestered) somewhere on or within the planet.

Overview

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for chemoautotrophs) and leaving as heat during the many transfers between trophic levels. However, the matter that makes up living organisms is conserved and recycled. The six most common elements associated with organic molecules—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in the atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath the Earth's surface. Geologic processes, such as weathering, erosion, water drainage, and the subduction of the continental plates, all play a role in this recycling of materials. Because geology and chemistry have major roles in the study of this process, the recycling of inorganic matter between living organisms and their environment is called a biogeochemical cycle.Biogeochemical Cycles''OpenStax'', 9 May 2019.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

The six aforementioned elements are used by organisms in a variety of ways. Hydrogen and oxygen are found in water and organic molecules, both of which are essential to life. Carbon is found in all organic molecules, whereas nitrogen is an important component of nucleic acids and proteins. Phosphorus is used to make nucleic acids and the phospholipids that comprise biological membranes. Sulfur is critical to the three-dimensional shape of proteins. The cycling of these elements is interconnected. For example, the movement of water is critical for leaching sulfur and phosphorus into rivers which can then flow into oceans. Minerals cycle through the biosphere between the biotic and abiotic components and from one organism to another.Fisher M. R. (Ed.) (2019) ''Environmental Biology''

3.2 Biogeochemical Cycles

OpenStax.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

The water cycle

Water is the medium of the oceans, the medium which carries all the substances and elements involved in the marine biogeochemical cycles.

Water as found in nature almost always includes dissolved substances, so water has been described as the "universal solvent" for its ability to dissolve so many substances. This ability allows it to be the "

Water is the medium of the oceans, the medium which carries all the substances and elements involved in the marine biogeochemical cycles.

Water as found in nature almost always includes dissolved substances, so water has been described as the "universal solvent" for its ability to dissolve so many substances. This ability allows it to be the "solvent

A solvent (s) (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for ...

of life" Water is also the only common substance that exists as solid

Solid is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being liquid, gas, and plasma). The molecules in a solid are closely packed together and contain the least amount of kinetic energy. A solid is characterized by structur ...

, liquid, and gas in normal terrestrial conditions. Since liquid water flows, ocean waters cycle and flow in currents around the world. Since water easily changes phase, it can be carried into the atmosphere as water vapour or frozen as an iceberg. It can then precipitate or melt to become liquid water again. All marine life is immersed in water, the matrix and womb of life itself. Water can be broken down into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen by metabolic or abiotic processes, and later recombined to become water again.

While the water cycle is itself a biogeochemical cycle

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and th ...

, flow of water over and beneath the Earth is a key component of the cycling of other biogeochemicals. Runoff is responsible for almost all of the transport of eroded sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand ...

and phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

from land to waterbodies

A body of water or waterbody (often spelled water body) is any significant accumulation of water on the surface of Earth or another planet. The term most often refers to oceans, seas, and lakes, but it includes smaller pools of water such as ...

. Cultural eutrophication

Eutrophication is the process by which an entire body of water, or parts of it, becomes progressively enriched with minerals and nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. It has also been defined as "nutrient-induced increase in phyt ...

of lakes is primarily due to phosphorus, applied in excess to agricultural fields in fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

s, and then transported overland and down rivers. Both runoff and groundwater flow play significant roles in transporting nitrogen from the land to waterbodies. The dead zone at the outlet of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

is a consequence of nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insolu ...

s from fertilizer being carried off agricultural fields and funnelled down the river system to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

. Runoff also plays a part in the carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as a major compon ...

, again through the transport of eroded rock and soil.

Ocean salinity

Ocean salinity is derived mainly from the weathering of rocks and the transport of dissolved salts from the land, with lesser contributions fromhydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspo ...

s in the seafloor.Why is the ocean salty?''NOAA''. Last updated: 26 February 2021. Evaporation of ocean water and formation of sea ice further increase the salinity of the ocean. However these processes which increase salinity are continually counterbalanced by processes that decrease salinity, such as the continuous input of fresh water from rivers, precipitation of rain and snow, and the melting of ice.Salinity

''NASA''. Last updated: 7 April 2021. The two most prevalent ions in seawater are chloride and sodium. Together, they make up around 85 percent of all dissolved ions in the ocean. Magnesium and sulfate ions make up most of the rest. Salinity varies with temperature, evaporation, and precipitation. It is generally low at the equator and poles, and high at mid-latitudes.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Sea spray

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray

Sea spray are aerosol particles formed from the ocean, mostly by ejection into Earth's atmosphere by bursting bubbles at the air-sea interface. Sea spray contains both organic matter and inorganic salts that form sea salt aerosol (SSA). SSA ha ...

. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet. This is another example of water facilitating the transport of organic material over great distances, in this case in the form of live microorganisms.

Dissolved salt does not evaporate back into the atmosphere like water, but it does form sea salt aerosols in sea spray

Sea spray are aerosol particles formed from the ocean, mostly by ejection into Earth's atmosphere by bursting bubbles at the air-sea interface. Sea spray contains both organic matter and inorganic salts that form sea salt aerosol (SSA). SSA ha ...

. Many physical process

Physical changes are changes affecting the form of a chemical substance, but not its chemical composition. Physical changes are used to separate mixtures into their component compounds, but can not usually be used to separate compounds into chem ...

es over ocean surface generate sea salt aerosols. One common cause is the bursting of air bubbles, which are entrained by the wind stress during the whitecap formation. Another is tearing of drops from wave tops. The total sea salt flux from the ocean to the atmosphere is about 3300 Tg (3.3 billion tonnes) per year.

Ocean circulation

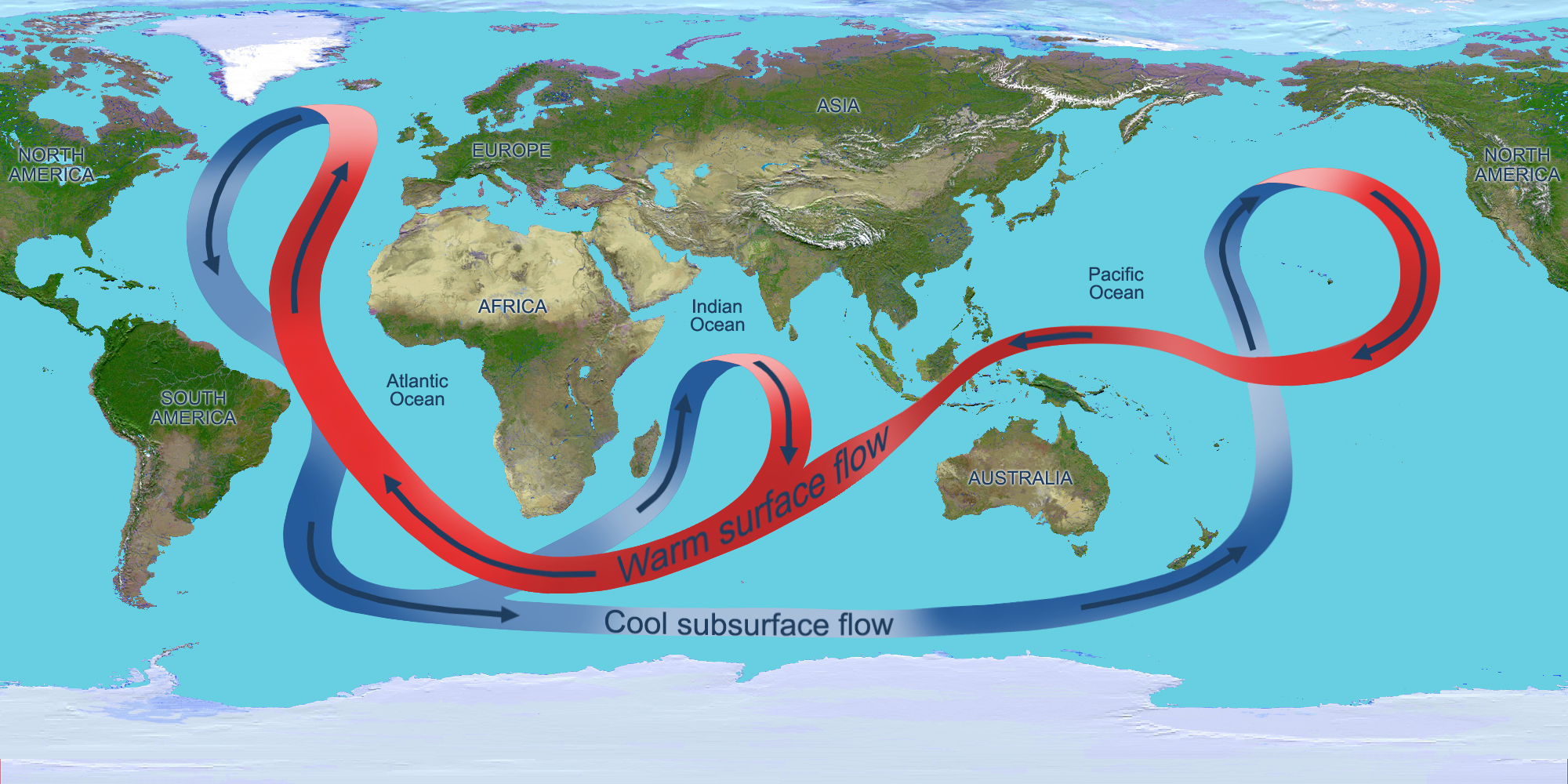

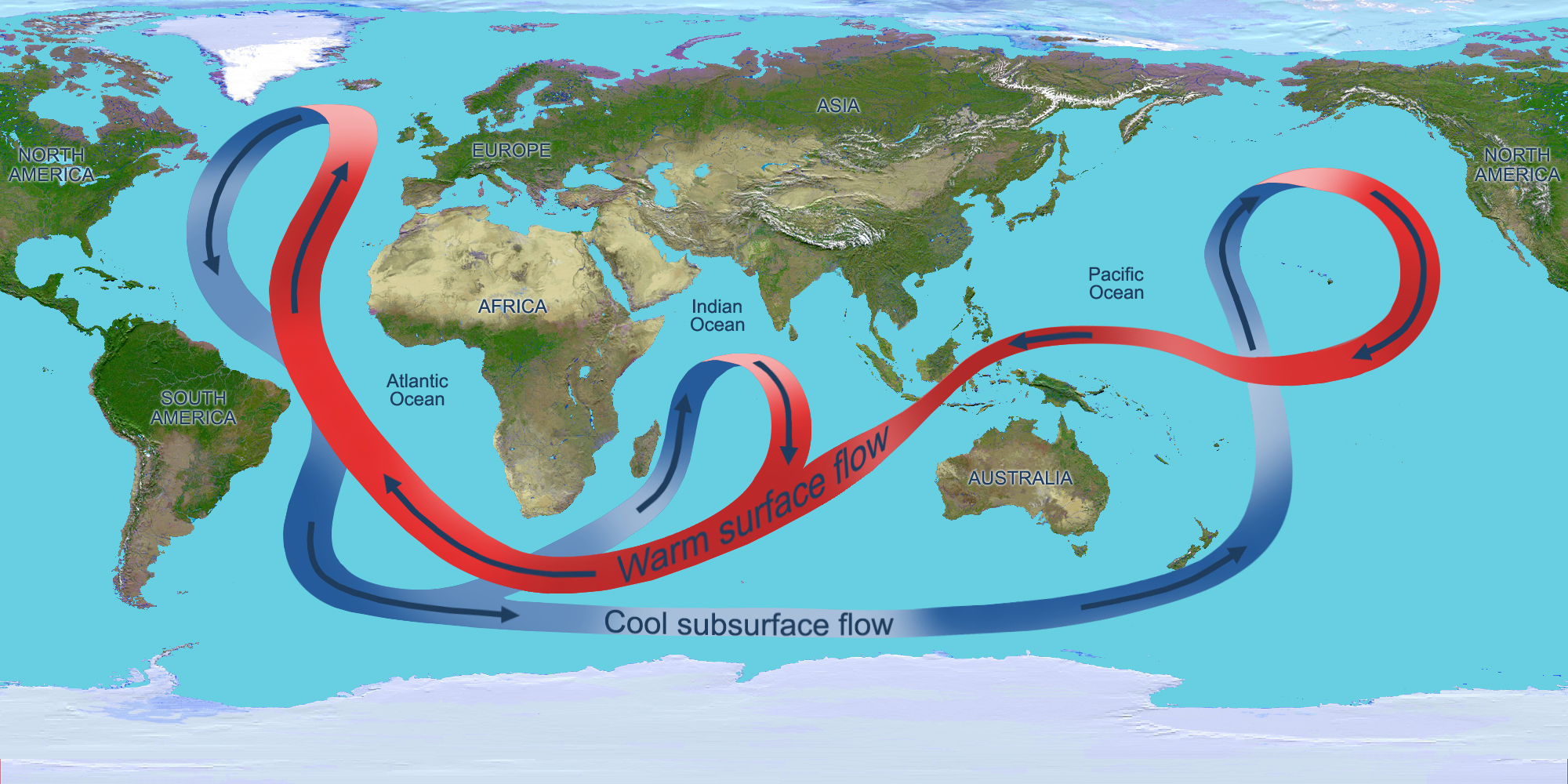

Solar radiation affects the oceans: warm water from the Equator tends to circulate toward the poles, while cold polar water heads towards the Equator. The surface currents are initially dictated by surface wind conditions. The

Solar radiation affects the oceans: warm water from the Equator tends to circulate toward the poles, while cold polar water heads towards the Equator. The surface currents are initially dictated by surface wind conditions. The trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisp ...

blow westward in the tropics, and the westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes and tren ...

blow eastward at mid-latitudes. This wind pattern applies a stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

to the subtropical ocean surface with negative curl

cURL (pronounced like "curl", UK: , US: ) is a computer software project providing a library (libcurl) and command-line tool (curl) for transferring data using various network protocols. The name stands for "Client URL".

History

cURL was ...

across the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

, and the reverse across the Southern Hemisphere. The resulting Sverdrup transport is equatorward. Because of conservation of potential vorticity

In fluid mechanics, potential vorticity (PV) is a quantity which is proportional to the dot product of vorticity and stratification. This quantity, following a parcel of air or water, can only be changed by diabatic or frictional processes. I ...

caused by the poleward-moving winds on the subtropical ridge

The horse latitudes are the latitudes about 30 degrees north and south of the Equator. They are characterized by sunny skies, calm winds, and very little precipitation. They are also known as subtropical ridges, or highs. It is a high-press ...

's western periphery and the increased relative vorticity of poleward moving water, transport is balanced by a narrow, accelerating poleward current, which flows along the western boundary of the ocean basin, outweighing the effects of friction with the cold western boundary current which originates from high latitudes. The overall process, known as western intensification, causes currents on the western boundary of an ocean basin to be stronger than those on the eastern boundary.

As it travels poleward, warm water transported by strong warm water current undergoes evaporative cooling. The cooling is wind driven: wind moving over water cools the water and also causes evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when h ...

, leaving a saltier brine. In this process, the water becomes saltier and denser. and decreases in temperature. Once sea ice forms, salts are left out of the ice, a process known as brine exclusion. These two processes produce water that is denser and colder. The water across the northern Atlantic ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

becomes so dense that it begins to sink down through less salty and less dense water. This downdraft of heavy, cold and dense water becomes a part of the North Atlantic Deep Water

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is a deep water mass formed in the North Atlantic Ocean. Thermohaline circulation (properly described as meridional overturning circulation) of the world's oceans involves the flow of warm surface waters from the ...

, a southgoing stream.

Winds drive ocean currents in the upper 100 meters of the ocean's surface. However, ocean currents also flow thousands of meters below the surface. These deep-ocean currents are driven by differences in the water's density, which is controlled by temperature (thermo) and salinity (haline). This process is known as thermohaline circulation. In the Earth's polar regions ocean water gets very cold, forming sea ice. As a consequence the surrounding seawater gets saltier, because when sea ice forms, the salt is left behind. As the seawater gets saltier, its density increases, and it starts to sink. Surface water is pulled in to replace the sinking water, which in turn eventually becomes cold and salty enough to sink. This initiates the deep-ocean currents driving the global conveyor belt.

Thermohaline circulation drives a global-scale system of currents called the “global conveyor belt.” The conveyor belt begins on the surface of the ocean near the pole in the North Atlantic. Here, the water is chilled by Arctic temperatures. It also gets saltier because when sea ice forms, the salt does not freeze and is left behind in the surrounding water. The cold water is now more dense, due to the added salts, and sinks toward the ocean bottom. Surface water moves in to replace the sinking water, thus creating a current. This deep water moves south, between the continents, past the equator, and down to the ends of Africa and South America. The current travels around the edge of Antarctica, where the water cools and sinks again, as it does in the North Atlantic. Thus, the conveyor belt gets "recharged." As it moves around Antarctica, two sections split off the conveyor and turn northward. One section moves into the Indian Ocean, the other into the Pacific Ocean. These two sections that split off warm up and become less dense as they travel northward toward the equator, so that they rise to the surface (upwelling). They then loop back southward and westward to the South Atlantic, eventually returning to the North Atlantic, where the cycle begins again. The conveyor belt moves at much slower speeds (a few centimeters per second) than wind-driven or tidal currents (tens to hundreds of centimeters per second). It is estimated that any given cubic meter of water takes about 1,000 years to complete the journey along the global conveyor belt. In addition, the conveyor moves an immense volume of water—more than 100 times the flow of the Amazon River (Ross, 1995). The conveyor belt is also a vital component of the global ocean nutrient and carbon dioxide cycles. Warm surface waters are depleted of nutrients and carbon dioxide, but they are enriched again as they travel through the conveyor belt as deep or bottom layers. The base of the world's food chain depends on the cool, nutrient-rich waters that support the growth of algae and seaweed.

The global average residence time of a water molecule in the ocean is about 3,200 years. By comparison the average residence time in the atmosphere is about 9 days. If it is frozen in the Antarctic or drawn into deep groundwater it can be sequestered for ten thousand years.

Cycling of key elements

Box models

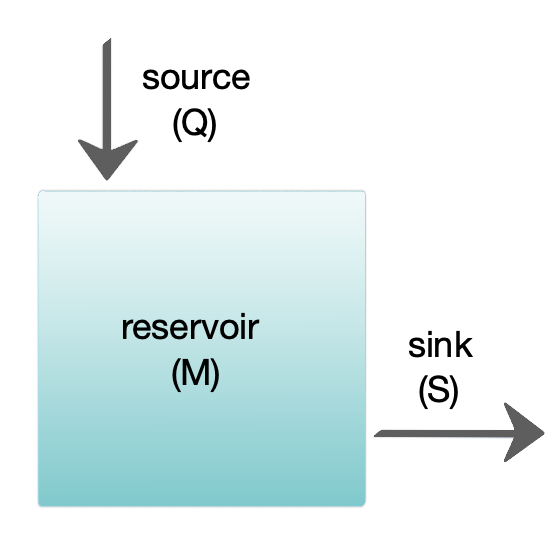

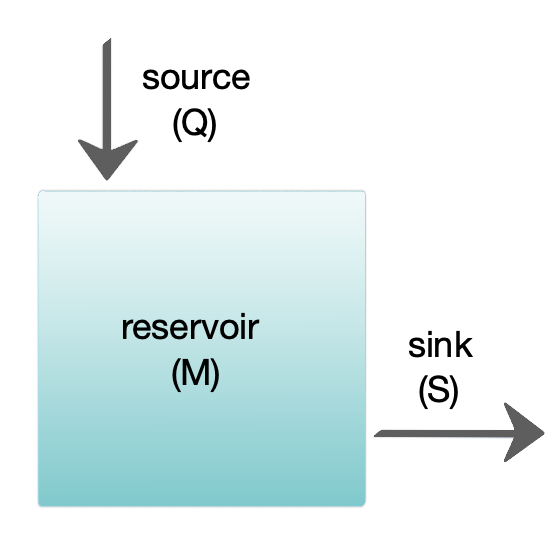

Box models are widely used to model biogeochemical systems. Box models are simplified versions of complex systems, reducing them to boxes (or storage

Box models are widely used to model biogeochemical systems. Box models are simplified versions of complex systems, reducing them to boxes (or storage reservoir

A reservoir (; from French ''réservoir'' ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam. Such a dam may be either artificial, built to store fresh water or it may be a natural formation.

Reservoirs can be created in a number of ways, including contr ...

s) for chemical materials, linked by material flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ...

es (flows). Simple box models have a small number of boxes with properties, such as volume, that do not change with time. The boxes are assumed to behave as if they were mixed homogeneously. These models are often used to derive analytical formulas describing the dynamics and steady-state abundance of the chemical species involved.

The diagram at the right shows a basic one-box model. The reservoir contains the amount of material ''M'' under consideration, as defined by chemical, physical or biological properties. The source ''Q'' is the flux of material into the reservoir, and the sink ''S'' is the flux of material out of the reservoir. The budget is the check and balance of the sources and sinks affecting material turnover in a reservoir. The reservoir is in a steady state

In systems theory, a system or a process is in a steady state if the variables (called state variables) which define the behavior of the system or the process are unchanging in time. In continuous time, this means that for those properties ''p' ...

if ''Q'' = ''S'', that is, if the sources balance the sinks and there is no change over time.

The turnover time

The residence time of a fluid parcel is the total time that the parcel has spent inside a control volume (e.g.: a chemical reactor, a lake, a human body). The residence time of a set of parcels is quantified in terms of the frequency distribution ...

(also called the renewal time or exit age) is the average time material spends resident in the reservoir. If the reservoir is in a steady state, this is the same as the time it takes to fill or drain the reservoir. Thus, if τ is the turnover time, then τ = M/S. The equation describing the rate of change of content in a reservoir is

::

When two or more reservoirs are connected, the material can be regarded as cycling between the reservoirs, and there can be predictable patterns to the cyclic flow. More complex multibox models are usually solved using numerical techniques.

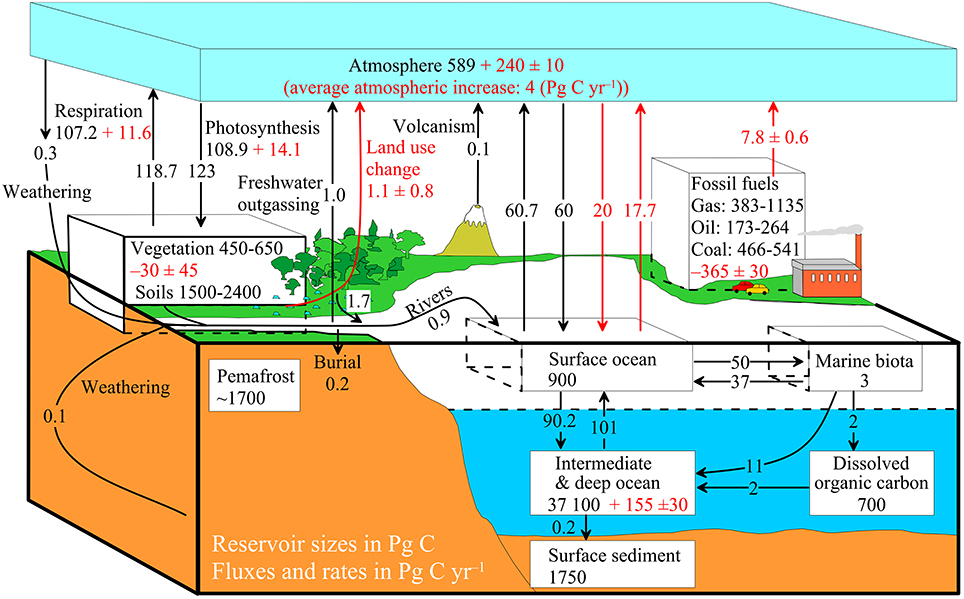

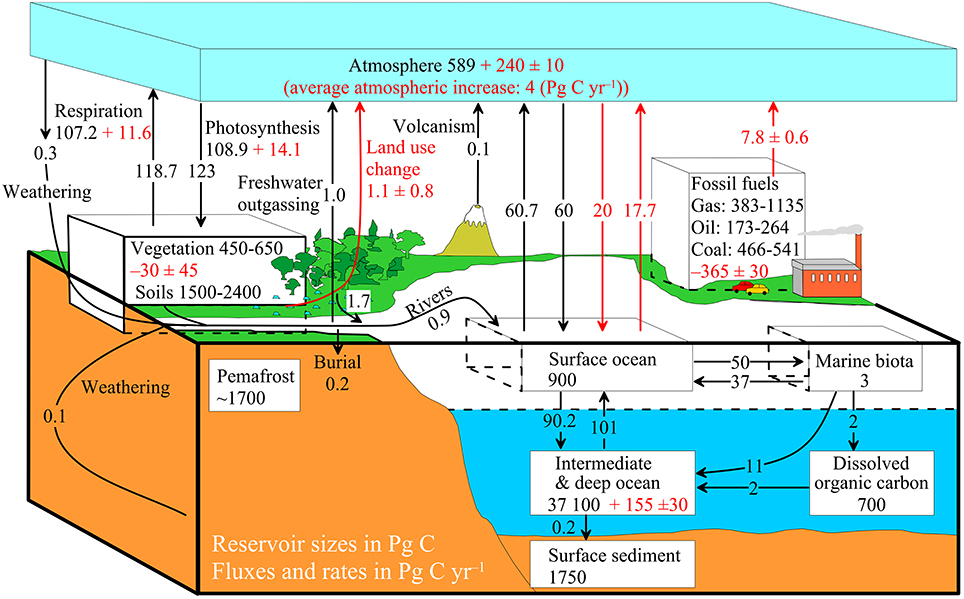

The diagram above shows a simplified budget of ocean carbon flows. It is composed of three simple interconnected box models, one for the

The diagram above shows a simplified budget of ocean carbon flows. It is composed of three simple interconnected box models, one for the euphotic zone

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological proc ...

, one for the ocean interior or dark ocean, and one for ocean sediment

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mai ...

s. In the euphotic zone, net phytoplankton production is about 50 Pg C each year. About 10 Pg is exported to the ocean interior while the other 40 Pg is respired. Organic carbon degradation occurs as particles

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscule in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

(marine snow

In the deep ocean, marine snow (also known as "ocean dandruff") is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to ...

) settle through the ocean interior. Only 2 Pg eventually arrives at the seafloor, while the other 8 Pg is respired in the dark ocean. In sediments, the time scale available for degradation increases by orders of magnitude with the result that 90% of the organic carbon delivered is degraded and only 0.2 Pg C yr−1 is eventually buried and transferred from the biosphere to the geosphere.

Dissolved and particulate matter

Biological pumps

Thebiological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments.Sigman DM & GH ...

, in its simplest form, is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

from the atmosphere to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments.Sigman DM & GH Haug. 2006. The biological pump in the past. In: Treatise on Geochemistry; vol. 6, (ed.). Pergamon Press, pp. 491-528 It is the part of the oceanic carbon cycle

The oceanic carbon cycle (or marine carbon cycle) is composed of processes that exchange carbon between various pools within the ocean as well as between the atmosphere, Earth interior, and the seafloor. The carbon cycle is a result of many inte ...

responsible for the cycling of organic matter

Organic matter, organic material, or natural organic matter refers to the large source of carbon-based compounds found within natural and engineered, terrestrial, and aquatic environments. It is matter composed of organic compounds that have c ...

formed mainly by phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

...

during photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

(soft-tissue pump), as well as the cycling of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) formed into shells by certain organisms such as plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cruc ...

and mollusks

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

(carbonate pump).

The biological pump can be divided into three distinct phases,De La Rocha CL. 2006. The Biological Pump. In: Treatise on Geochemistry; vol. 6, (ed.). Pergamon Press, pp. 83-111 the first of which is the production of fixed carbon by planktonic phototrophs in the euphotic

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological pro ...

(sunlit) surface region of the ocean. In these surface waters, phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

...

use carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

(CO2), nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

(N), phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

(P), and other trace elements (barium

Barium is a chemical element with the symbol Ba and atomic number 56. It is the fifth element in group 2 and is a soft, silvery alkaline earth metal. Because of its high chemical reactivity, barium is never found in nature as a free element.

Th ...

, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

, etc.) during photosynthesis to make carbohydrates

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or m ...

, lipids

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

, and proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

. Some plankton, (e.g. coccolithophores

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingd ...

and foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

) combine calcium (Ca) and dissolved carbonates ( carbonic acid and bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial biochemi ...

) to form a calcium carbonate (CaCO3) protective coating.

Once this carbon is fixed into soft or hard tissue, the organisms either stay in the euphotic zone to be recycled as part of the regenerative nutrient cycle

A nutrient cycle (or ecological recycling) is the movement and exchange of inorganic and organic matter back into the production of matter. Energy flow is a unidirectional and noncyclic pathway, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cyc ...

or once they die, continue to the second phase of the biological pump and begin to sink to the ocean floor. The sinking particles will often form aggregates as they sink, greatly increasing the sinking rate. It is this aggregation that gives particles a better chance of escaping predation and decomposition in the water column and eventually make it to the sea floor.

The fixed carbon that is either decomposed by bacteria on the way down or once on the sea floor then enters the final phase of the pump and is remineralized to be used again in primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

. The particles that escape these processes entirely are sequestered in the sediment and may remain there for millions of years. It is this sequestered carbon that is responsible for ultimately lowering atmospheric CO2.

* Brum JR, Morris JJ, Décima M and Stukel MR (2014) "Mortality in the oceans: Causes and consequences". ''Eco-DAS IX Symposium Proceedings'', Chapter 2, pages 16–48. Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography. .

* Mateus, M.D. (2017) "Bridging the gap between knowing and modeling viruses in marine systems—An upcoming frontier". ''Frontiers in Marine Science'', 3: 284.

* Beckett, S.J. and Weitz, J.S. (2017) "Disentangling niche competition from grazing mortality in phytoplankton dilution experiments". ''PLOS ONE'', 12(5): e0177517. .

Role of microorganisms

Carbon, oxygen and hydrogen cycles

Themarine carbon cycle

The oceanic carbon cycle (or marine carbon cycle) is composed of processes that exchange carbon between various pools within the ocean as well as between the atmosphere, Earth interior, and the Seabed, seafloor. The carbon cycle is a result of ma ...

is composed of processes that exchange carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

between various pools within the ocean as well as between the atmosphere, Earth interior, and the seafloor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth an ...

. The carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as a major compon ...

is a result of many interacting forces across multiple time and space scales that circulates carbon around the planet, ensuring that carbon is available globally. The Oceanic carbon cycle is a central process to the global carbon cycle and contains both inorganic

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemist ...

carbon (carbon not associated with a living thing, such as carbon dioxide) and organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

carbon (carbon that is, or has been, incorporated into a living thing). Part of the marine carbon cycle transforms carbon between non-living and living matter.

Three main processes (or pumps) that make up the marine carbon cycle bring atmospheric carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

(CO2) into the ocean interior and distribute it through the oceans. These three pumps are: (1) the solubility pump, (2) the carbonate pump, and (3) the biological pump. The total active pool of carbon at the Earth's surface for durations of less than 10,000 years is roughly 40,000 gigatons C (Gt C, a gigaton is one billion tons, or the weight of approximately 6 million blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

s), and about 95% (~38,000 Gt C) is stored in the ocean, mostly as dissolved inorganic carbon. The speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution withi ...

of dissolved inorganic carbon in the marine carbon cycle is a primary controller of acid-base chemistry in the oceans.

Nitrogen and phosphorus cycles

The nitrogen cycle is as important in the ocean as it is on land. While the overall cycle is similar in both cases, there are different players and modes of transfer for nitrogen in the ocean. Nitrogen enters the ocean through precipitation, runoff, or as N2 from the atmosphere. Nitrogen cannot be utilized by

The nitrogen cycle is as important in the ocean as it is on land. While the overall cycle is similar in both cases, there are different players and modes of transfer for nitrogen in the ocean. Nitrogen enters the ocean through precipitation, runoff, or as N2 from the atmosphere. Nitrogen cannot be utilized by phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

...

as N2 so it must undergo nitrogen fixation

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular nitrogen (), with a strong triple covalent bond, in the air is converted into ammonia () or related nitrogenous compounds, typically in soil or aquatic systems but also in industry. Atmo ...

which is performed predominantly by cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, bl ...

. Without supplies of fixed nitrogen entering the marine cycle, the fixed nitrogen would be used up in about 2000 years. Phytoplankton need nitrogen in biologically available forms for the initial synthesis of organic matter. Ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous ...

and urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

are released into the water by excretion from plankton. Nitrogen sources are removed from the euphotic zone

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological proc ...

by the downward movement of the organic matter. This can occur from sinking of phytoplankton, vertical mixing, or sinking of waste of vertical migrators. The sinking results in ammonia being introduced at lower depths below the euphotic zone. Bacteria are able to convert ammonia to nitrite

The nitrite ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name nitrite also ...

and nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insolu ...

but they are inhibited by light so this must occur below the euphotic zone. Ammonification or mineralization

Mineralization may refer to:

* Mineralization (biology), when an inorganic substance precipitates in an organic matrix

** Biomineralization, a form of mineralization

** Mineralization of bone, an example of mineralization

** Mineralized tissues ar ...

is performed by bacteria to convert organic nitrogen to ammonia. Nitrification

''Nitrification'' is the biological oxidation of ammonia to nitrite followed by the oxidation of the nitrite to nitrate occurring through separate organisms or direct ammonia oxidation to nitrate in comammox bacteria. The transformation of ...

can then occur to convert the ammonium to nitrite and nitrate. Nitrate can be returned to the euphotic zone by vertical mixing and upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted ...

where it can be taken up by phytoplankton to continue the cycle. N2 can be returned to the atmosphere through denitrification

Denitrification is a microbially facilitated process where nitrate (NO3−) is reduced and ultimately produces molecular nitrogen (N2) through a series of intermediate gaseous nitrogen oxide products. Facultative anaerobic bacteria perform denit ...

.

Ammonium is thought to be the preferred source of fixed nitrogen for phytoplankton because its assimilation does not involve a redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

reaction and therefore requires little energy. Nitrate requires a redox reaction for assimilation but is more abundant so most phytoplankton have adapted to have the enzymes necessary to undertake this reduction (nitrate reductase

Nitrate reductases are molybdoenzymes that reduce nitrate (NO) to nitrite (NO). This reaction is critical for the production of protein in most crop plants, as nitrate is the predominant source of nitrogen in fertilized soils.

Types

Euk ...

). There are a few notable and well-known exceptions that include most ''Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosynth ...

'' and some ''Synechococcus

''Synechococcus'' (from the Greek ''synechos'', in succession, and the Greek ''kokkos'', granule) is a unicellular cyanobacterium that is very widespread in the marine environment. Its size varies from 0.8 to 1.5 µm. The photosynthetic c ...

'' that can only take up nitrogen as ammonium.

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for plants and animals. Phosphorus is a limiting nutrient

A limiting factor is a variable of a system that causes a noticeable change in output or another measure of a type of system. The limiting factor is in a pyramid shape of organisms going up from the producers to consumers and so on. A factor not l ...

for aquatic organisms. Phosphorus forms parts of important life-sustaining molecules that are very common in the biosphere. Phosphorus does enter the atmosphere in very small amounts when the dust is dissolved in rainwater and seaspray but remains mostly on land and in rock and soil minerals. Eighty percent of the mined phosphorus is used to make fertilizers. Phosphates from fertilizers, sewage and detergents can cause pollution in lakes and streams. Over-enrichment of phosphate in both fresh and inshore marine waters can lead to massive algae bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in freshwater or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompasse ...

s which, when they die and decay leads to eutrophication

Eutrophication is the process by which an entire body of water, or parts of it, becomes progressively enriched with minerals and nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. It has also been defined as "nutrient-induced increase in phyt ...

of freshwaters only. Recent research suggests that the predominant pollutant responsible for algal blooms in saltwater estuaries and coastal marine habitats is nitrogen.

Phosphorus occurs most abundantly in nature as part of the orthophosphate

A phosphoric acid, in the general sense, is a phosphorus oxoacid in which each phosphorus (P) atom is in the oxidation state +5, and is bonded to four oxygen (O) atoms, one of them through a double bond, arranged as the corners of a tetrahedron. ...

ion (PO4)3−, consisting of a P atom and 4 oxygen atoms. On land most phosphorus is found in rocks and minerals. Phosphorus-rich deposits have generally formed in the ocean or from guano, and over time, geologic processes bring ocean sediments to land. Weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs '' in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement ...

of rocks and minerals release phosphorus in a soluble form where it is taken up by plants, and it is transformed into organic compounds. The plants may then be consumed by herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

s and the phosphorus is either incorporated into their tissues or excreted. After death, the animal or plant decays, and phosphorus is returned to the soil where a large part of the phosphorus is transformed into insoluble compounds. Runoff

Runoff, run-off or RUNOFF may refer to:

* RUNOFF, the first computer text-formatting program

* Runoff or run-off, another name for bleed, printing that lies beyond the edges to which a printed sheet is trimmed

* Runoff or run-off, a stock marke ...

may carry a small part of the phosphorus back to the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wor ...

.

Nutrient cycle

A

A nutrient cycle

A nutrient cycle (or ecological recycling) is the movement and exchange of inorganic and organic matter back into the production of matter. Energy flow is a unidirectional and noncyclic pathway, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cyc ...

is the movement and exchange of organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

and inorganic

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemist ...

matter back into the production of matter. The process is regulated by the pathways available in marine food webs

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have biomass pyramids which are inverted at the base. In particular, the biomass of consumers (copepods, krill, shrimp, forage fish) is larger than the biomass of primary producers. Thi ...

, which ultimately decompose organic matter back into inorganic nutrients. Nutrient cycles occur within ecosystems. Energy flow always follows a unidirectional and noncyclic path, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cyclic. Mineral cycles include the carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as a major compon ...

, oxygen cycle, nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into multiple chemical forms as it circulates among atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems. The conversion of nitrogen can be carried out through both biolo ...

, phosphorus cycle and sulfur cycle

The sulfur cycle is a biogeochemical cycle in which the sulfur moves between rocks, waterways and living systems. It is important in geology as it affects many minerals and in life because sulfur is an essential element (CHNOPS), being a con ...

among others that continually recycle along with other mineral nutrients into productive

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proces ...

ecological nutrition.

There is considerable overlap between the terms for the biogeochemical cycle

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and th ...

and nutrient cycle. Some textbooks integrate the two and seem to treat them as synonymous terms. However, the terms often appear independently. Nutrient cycle is more often used in direct reference to the idea of an intra-system cycle, where an ecosystem functions as a unit. From a practical point, it does not make sense to assess a terrestrial ecosystem by considering the full column of air above it as well as the great depths of Earth below it. While an ecosystem often has no clear boundary, as a working model it is practical to consider the functional community where the bulk of matter and energy transfer occurs. Nutrient cycling occurs in ecosystems that participate in the "larger biogeochemical cycles of the earth through a system of inputs and outputs."

Dissolved nutrients

Nutrients dissolved in seawater are essential for the survival of marine life. Nitrogen and phosphorus are particularly important. They are regarded aslimiting nutrient

A limiting factor is a variable of a system that causes a noticeable change in output or another measure of a type of system. The limiting factor is in a pyramid shape of organisms going up from the producers to consumers and so on. A factor not l ...

s in many marine environments, because primary producers, like algae and marine plants, cannot grow without them. They are critical for stimulating primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

by phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

...

. Other important nutrients are silicon, iron, and zinc.Dissolved Nutrients''Earth in the Future'', PenState/NASSA. Retrieved 18 June 2020. The process of cycling nutrients in the sea starts with biological pumping, when nutrients are extracted from surface waters by phytoplankton to become part of their organic makeup. Phytoplankton are either eaten by other organisms, or eventually die and drift down as

marine snow

In the deep ocean, marine snow (also known as "ocean dandruff") is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to ...

. There they decay and return to the dissolved state, but at greater ocean depths. The fertility of the oceans depends on the abundance of the nutrients, and is measured by the primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

, which is the rate of fixation of carbon per unit of water per unit time. "Primary production is often mapped by satellites using the distribution of chlorophyll, which is a pigment produced by plants that absorbs energy during photosynthesis. The distribution of chlorophyll is shown in the figure above. You can see the highest abundance close to the coastlines where nutrients from the land are fed in by rivers. The other location where chlorophyll levels are high is in upwelling zones where nutrients are brought to the surface ocean from depth by the upwelling process..."

nutrient cycle

A nutrient cycle (or ecological recycling) is the movement and exchange of inorganic and organic matter back into the production of matter. Energy flow is a unidirectional and noncyclic pathway, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cyc ...

File:Nutrient flux.png, Ocean nutrient flux

Marine sulfur cycle

Sulfate reduction in the seabed is strongly focused toward near-surface sediments with high depositional rates along the ocean margins. The benthic marine sulfur cycle is therefore sensitive to anthropogenic influence, such as ocean warming and increased nutrient loading of coastal seas. This stimulates photosynthetic productivity and results in enhanced export of organic matter to the seafloor, often combined with low oxygen concentration in the bottom water (Rabalais et al., 2014; Breitburg et al., 2018). The biogeochemical zonation is thereby compressed toward the sediment surface, and the balance of organic matter mineralization is shifted from oxic and suboxic processes toward sulfate reduction and methanogenesis (Middelburg and Levin, 2009). *

* cable bacteria

Cable bacteria are filamentous bacteria that conduct electricity across distances over 1 cm in sediment and groundwater aquifers. Cable bacteria allow for long-distance electron transport, which connects electron donors to electron accepto ...

The sulfur cycle in marine environments has been well-studied via the tool of sulfur isotope systematics expressed as δ34S. The modern global oceans have sulfur storage of 1.3 × 1021 g, mainly occurring as sulfate with the δ34S value of +21‰. The overall input flux is 1.0 × 1014 g/year with the sulfur isotope composition of ~3‰. Riverine sulfate derived from the terrestrial weathering of sulfide minerals (δ34S = +6‰) is the primary input of sulfur to the oceans. Other sources are metamorphic and volcanic degassing and hydrothermal activity (δ34S = 0‰), which release reduced sulfur species (e.g., H2S and S0). There are two major outputs of sulfur from the oceans. The first sink is the burial of sulfate either as marine evaporites (e.g., gypsum) or carbonate-associated sulfate (CAS), which accounts for 6 × 1013 g/year (δ34S = +21‰). The second sulfur sink is pyrite burial in shelf sediments or deep seafloor sediments (4 × 1013 g/year; δ34S = -20‰). The total marine sulfur output flux is 1.0 × 1014 g/year which matches the input fluxes, implying the modern marine sulfur budget is at steady state. The residence time of sulfur in modern global oceans is 13,000,000 years.

In modern oceans, ''Hydrogenovibrio crunogenus

''Hydrogenovibrio crunogenus'' (basonym ''Thiomicrospira crunogena'')

is a colorless, sulfur-oxidizing bacterium first isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. It is an obligate chemolithoautotrophic sulfur oxidizer and differs from other ...

'', ''Halothiobacillus

''Halothiobacillus'' is a genus in the ''Gammaproteobacteria''. Both species are obligate aerobic bacteria; they require oxygen to grow. They are also halotolerant; they live in environments with high concentrations of salt or other solutes, bu ...

'', and ''Beggiatoa

''Beggiatoa'' is a genus of '' Gammaproteobacteria'' belonging the order ''Thiotrichales,'' in the '' Pseudomonadota'' phylum. This genus was one of the first bacteria discovered by Ukrainian botanist Sergei Winogradsky. During his research in ...

'' are primary sulfur oxidizing bacteria, and form chemosynthetic symbioses with animal hosts. The host provides metabolic substrates (e.g., CO2, O2, H2O) to the symbiont while the symbiont generates organic carbon for sustaining the metabolic activities of the host. The produced sulfate usually combines with the leached calcium ions to form gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and drywa ...

, which can form widespread deposits on near mid-ocean spreading centers.

Hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspo ...

s emit hydrogen sulfide that support the carbon fixation of chemolithotrophic bacteria that oxidize hydrogen sulfide with oxygen to produce elemental sulfur or sulfate.

Iron cycle and dust

The

The iron cycle

The iron cycle (Fe) is the biogeochemical cycle of iron through the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and lithosphere. While Fe is highly abundant in the Earth's crust, it is less common in oxygenated surface waters. Iron is a key micronutrient i ...

(Fe) is the biogeochemical cycle of iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

through the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

, hydrosphere

The hydrosphere () is the combined mass of water found on, under, and above the surface of a planet, minor planet, or natural satellite. Although Earth's hydrosphere has been around for about 4 billion years, it continues to change in shape. This ...

, biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also ...

and lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

. While Fe is highly abundant in the Earth's crust, it is less common in oxygenated surface waters. Iron is a key micronutrient in primary productivity

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through c ...

, and a limiting nutrient

A limiting factor is a variable of a system that causes a noticeable change in output or another measure of a type of system. The limiting factor is in a pyramid shape of organisms going up from the producers to consumers and so on. A factor not l ...

in the Southern ocean, eastern equatorial Pacific, and the subarctic Pacific referred to as High-Nutrient, Low-Chlorophyll (HNLC) regions of the ocean.

Iron in the ocean cycles between plankton, aggregated particulates (non-bioavailable iron), and dissolved (bioavailable iron), and becomes sediments through burial. Hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspo ...

s release ferrous iron to the ocean in addition to oceanic iron inputs from land sources. Iron reaches the atmosphere through volcanism, aeolian wind, and some via combustion by humans. In the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene ( ) is a proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems, including, but not limited to, anthropogenic climate change.

, neither the International Commissio ...

, iron is removed from mines in the crust and a portion re-deposited in waste repositories.

Iron is an essential micronutrient for almost every life form. It is a key component of hemoglobin, important to nitrogen fixation as part of the

Iron is an essential micronutrient for almost every life form. It is a key component of hemoglobin, important to nitrogen fixation as part of the Nitrogenase