Magic (paranormal) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Magic, sometimes spelled magick, is an ancient

Magic, sometimes spelled magick, is an ancient

The English words ''magic'', ''mage'' and ''magician'' come from the

The English words ''magic'', ''mage'' and ''magician'' come from the

Magic was invoked in many kinds of rituals and medical formulae, and to counteract evil omens. Defensive or legitimate magic in Mesopotamia (''asiputu'' or ''masmassutu'' in the Akkadian language) were incantations and ritual practices intended to alter specific realities. The ancient

Magic was invoked in many kinds of rituals and medical formulae, and to counteract evil omens. Defensive or legitimate magic in Mesopotamia (''asiputu'' or ''masmassutu'' in the Akkadian language) were incantations and ritual practices intended to alter specific realities. The ancient

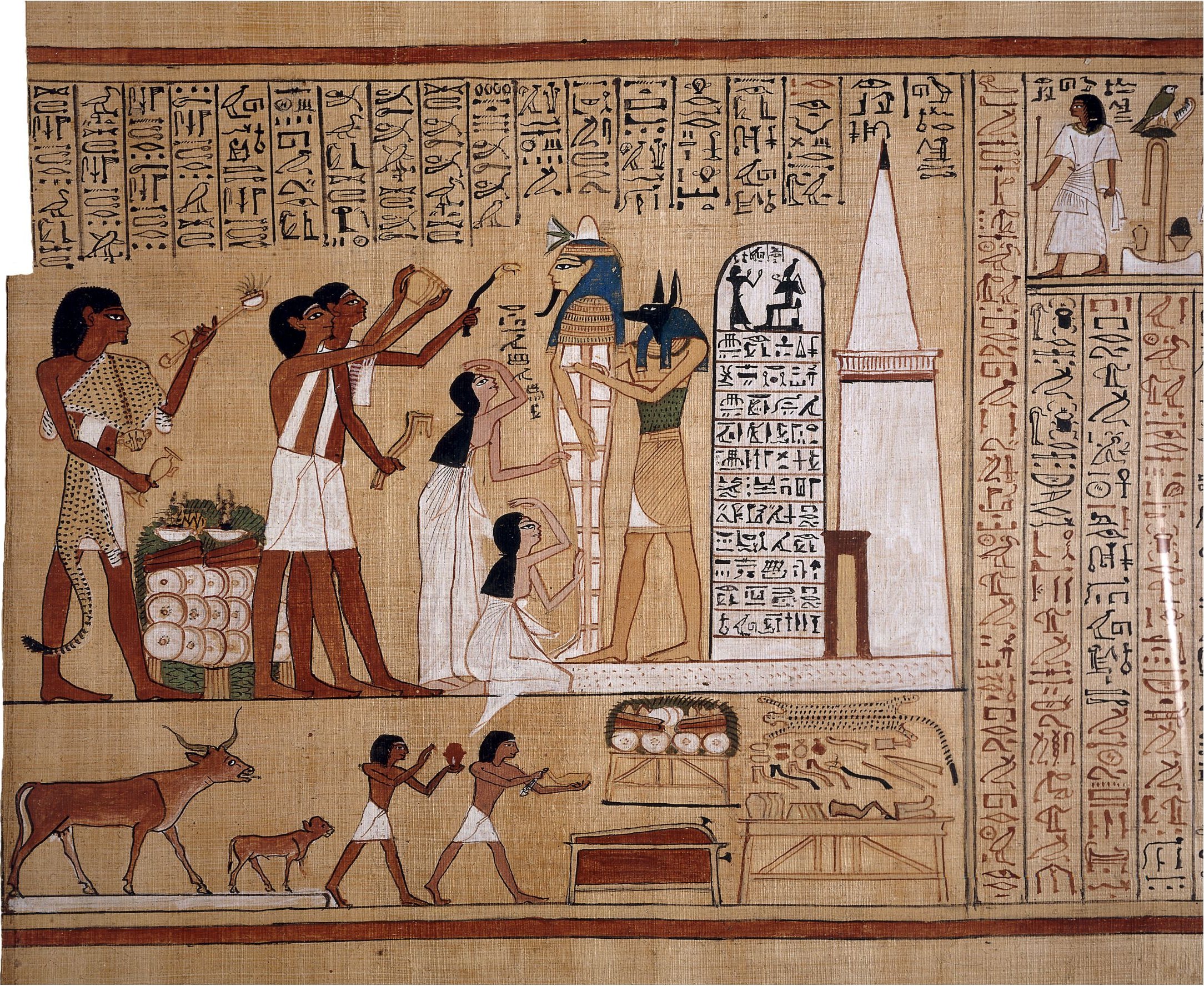

In ancient Egypt (''Kemet'' in the Egyptian language), Magic (personified as the god ''heka'') was an integral part of religion and culture which is known to us through a substantial corpus of texts which are products of the Egyptian tradition.

While the category magic has been contentious for modern Egyptology, there is clear support for its applicability from ancient terminology.Ritner, R.K., Magic: An Overview in Redford, D.B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2001, p 321 The Coptic term ''hik'' is the descendant of the pharaonic term ''heka'', which, unlike its Coptic counterpart, had no connotation of impiety or illegality, and is attested from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman era. ''heka'' was considered morally neutral and was applied to the practices and beliefs of both foreigners and Egyptians alike. The Instructions for Merikare informs us that ''heka'' was a beneficence gifted by the creator to humanity "... in order to be weapons to ward off the blow of events".

Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of ''heka'' underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

The main principle of ''heka'' is centered on the power of words to bring things into being. Karenga explains the pivotal power of words and their vital ontological role as the primary tool used by the creator to bring the manifest world into being. Because humans were understood to share a divine nature with the gods, ''snnw ntr'' (images of the god), the same power to use words creatively that the gods have is shared by humans.

In ancient Egypt (''Kemet'' in the Egyptian language), Magic (personified as the god ''heka'') was an integral part of religion and culture which is known to us through a substantial corpus of texts which are products of the Egyptian tradition.

While the category magic has been contentious for modern Egyptology, there is clear support for its applicability from ancient terminology.Ritner, R.K., Magic: An Overview in Redford, D.B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2001, p 321 The Coptic term ''hik'' is the descendant of the pharaonic term ''heka'', which, unlike its Coptic counterpart, had no connotation of impiety or illegality, and is attested from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman era. ''heka'' was considered morally neutral and was applied to the practices and beliefs of both foreigners and Egyptians alike. The Instructions for Merikare informs us that ''heka'' was a beneficence gifted by the creator to humanity "... in order to be weapons to ward off the blow of events".

Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of ''heka'' underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

The main principle of ''heka'' is centered on the power of words to bring things into being. Karenga explains the pivotal power of words and their vital ontological role as the primary tool used by the creator to bring the manifest world into being. Because humans were understood to share a divine nature with the gods, ''snnw ntr'' (images of the god), the same power to use words creatively that the gods have is shared by humans.

The English word magic has its origins in

The English word magic has its origins in

For early Christian writers like

For early Christian writers like  In the Medieval Jewish view, the separation of the

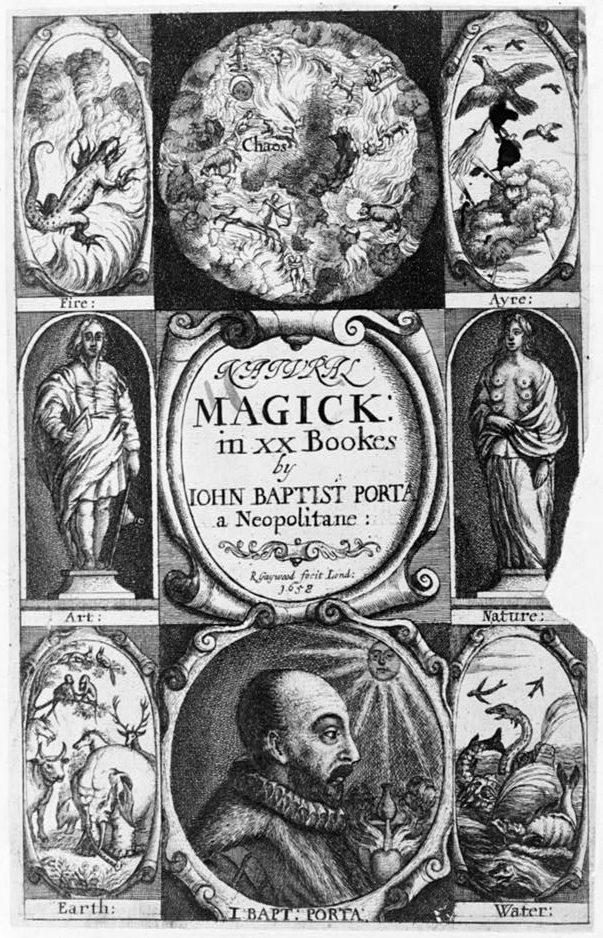

In the Medieval Jewish view, the separation of the  During the early modern period, the concept of magic underwent a more positive reassessment through the development of the concept of '' magia naturalis'' (natural magic). This was a term introduced and developed by two Italian humanists,

During the early modern period, the concept of magic underwent a more positive reassessment through the development of the concept of '' magia naturalis'' (natural magic). This was a term introduced and developed by two Italian humanists,

In the sixteenth century, European societies began to conquer and colonise other continents around the world, and as they did so they applied European concepts of magic and witchcraft to practices found among the peoples whom they encountered. Usually, these European colonialists regarded the natives as primitives and savages whose belief systems were diabolical and needed to be eradicated and replaced by Christianity. Because Europeans typically viewed these non-European peoples as being morally and intellectually inferior to themselves, it was expected that such societies would be more prone to practicing magic. Women who practiced traditional rites were labelled as witches by the Europeans.

In various cases, these imported European concepts and terms underwent new transformations as they merged with indigenous concepts. In West Africa, for instance, Portuguese travellers introduced their term and concept of the ''feitiçaria'' (often translated as sorcery) and the ''feitiço'' (spell) to the native population, where it was transformed into the concept of the fetish. When later Europeans encountered these West African societies, they wrongly believed that the ''fetiche'' was an indigenous African term rather than the result of earlier inter-continental encounters. Sometimes, colonised populations themselves adopted these European concepts for their own purposes. In the early nineteenth century, the newly independent Haitian government of

In the sixteenth century, European societies began to conquer and colonise other continents around the world, and as they did so they applied European concepts of magic and witchcraft to practices found among the peoples whom they encountered. Usually, these European colonialists regarded the natives as primitives and savages whose belief systems were diabolical and needed to be eradicated and replaced by Christianity. Because Europeans typically viewed these non-European peoples as being morally and intellectually inferior to themselves, it was expected that such societies would be more prone to practicing magic. Women who practiced traditional rites were labelled as witches by the Europeans.

In various cases, these imported European concepts and terms underwent new transformations as they merged with indigenous concepts. In West Africa, for instance, Portuguese travellers introduced their term and concept of the ''feitiçaria'' (often translated as sorcery) and the ''feitiço'' (spell) to the native population, where it was transformed into the concept of the fetish. When later Europeans encountered these West African societies, they wrongly believed that the ''fetiche'' was an indigenous African term rather than the result of earlier inter-continental encounters. Sometimes, colonised populations themselves adopted these European concepts for their own purposes. In the early nineteenth century, the newly independent Haitian government of

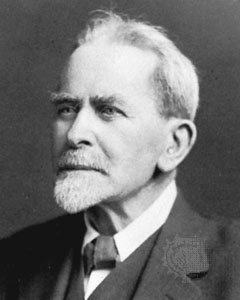

The intellectualist approach to defining magic is associated with two prominent British

The intellectualist approach to defining magic is associated with two prominent British  Tylor's ideas were adopted and simplified by James Frazer. He used the term magic to mean sympathetic magic, describing it as a practice relying on the magician's belief "that things act on each other at a distance through a secret sympathy", something which he described as "an invisible ether". He further divided this magic into two forms, the "homeopathic (imitative, mimetic)" and the "contagious". The former was the idea that "like produces like", or that the similarity between two objects could result in one influencing the other. The latter was based on the idea that contact between two objects allowed the two to continue to influence one another at a distance. Like Taylor, Frazer viewed magic negatively, describing it as "the bastard sister of science", arising from "one great disastrous fallacy".

Where Frazer differed from Tylor was in characterizing a belief in magic as a major stage in humanity's cultural development, describing it as part of a tripartite division in which magic came first, religion came second, and eventually science came third. For Frazer, all early societies started as believers in magic, with some of them moving away from this and into religion. He believed that both magic and religion involved a belief in spirits but that they differed in the way that they responded to these spirits. For Frazer, magic "constrains or coerces" these spirits while religion focuses on "conciliating or propitiating them". He acknowledged that their common ground resulted in a cross-over of magical and religious elements in various instances; for instance he claimed that the

Tylor's ideas were adopted and simplified by James Frazer. He used the term magic to mean sympathetic magic, describing it as a practice relying on the magician's belief "that things act on each other at a distance through a secret sympathy", something which he described as "an invisible ether". He further divided this magic into two forms, the "homeopathic (imitative, mimetic)" and the "contagious". The former was the idea that "like produces like", or that the similarity between two objects could result in one influencing the other. The latter was based on the idea that contact between two objects allowed the two to continue to influence one another at a distance. Like Taylor, Frazer viewed magic negatively, describing it as "the bastard sister of science", arising from "one great disastrous fallacy".

Where Frazer differed from Tylor was in characterizing a belief in magic as a major stage in humanity's cultural development, describing it as part of a tripartite division in which magic came first, religion came second, and eventually science came third. For Frazer, all early societies started as believers in magic, with some of them moving away from this and into religion. He believed that both magic and religion involved a belief in spirits but that they differed in the way that they responded to these spirits. For Frazer, magic "constrains or coerces" these spirits while religion focuses on "conciliating or propitiating them". He acknowledged that their common ground resulted in a cross-over of magical and religious elements in various instances; for instance he claimed that the

The term magic was used liberally by Freud. He also saw magic as emerging from human emotion but interpreted it very differently to Marett.

Freud explains that "the associated theory of magic merely explains the paths along which magic proceeds; it does not explain its true essence, namely the misunderstanding which leads it to replace the laws of nature by psychological ones". Freud emphasizes that what led primitive men to come up with magic is the power of wishes: "His wishes are accompanied by a motor impulse, the will, which is later destined to alter the whole face of the earth to satisfy his wishes. This motor impulse is at first employed to give a representation of the satisfying situation in such a way that it becomes possible to experience the satisfaction by means of what might be described as motor

The term magic was used liberally by Freud. He also saw magic as emerging from human emotion but interpreted it very differently to Marett.

Freud explains that "the associated theory of magic merely explains the paths along which magic proceeds; it does not explain its true essence, namely the misunderstanding which leads it to replace the laws of nature by psychological ones". Freud emphasizes that what led primitive men to come up with magic is the power of wishes: "His wishes are accompanied by a motor impulse, the will, which is later destined to alter the whole face of the earth to satisfy his wishes. This motor impulse is at first employed to give a representation of the satisfying situation in such a way that it becomes possible to experience the satisfaction by means of what might be described as motor

Many of the practices which have been labelled magic can be performed by anyone. For instance, some charms can be recited by individuals with no specialist knowledge nor any claim to having a specific power. Others require specialised training in order to perform them. Some of the individuals who performed magical acts on a more than occasional basis came to be identified as magicians, or with related concepts like sorcerers/sorceresses,

Many of the practices which have been labelled magic can be performed by anyone. For instance, some charms can be recited by individuals with no specialist knowledge nor any claim to having a specific power. Others require specialised training in order to perform them. Some of the individuals who performed magical acts on a more than occasional basis came to be identified as magicians, or with related concepts like sorcerers/sorceresses,

''Catholic Encyclopedia'' "Occult Art, Occultism"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Magic (supernatural)

Magic, sometimes spelled magick, is an ancient

Magic, sometimes spelled magick, is an ancient praxis

Praxis may refer to:

Philosophy and religion

* Praxis (process), the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, practised, embodied, or realised

* Praxis model, a way of doing theology

* Praxis (Byzantine Rite), the practice of fai ...

rooted in sacred rituals, spiritual divinations, and/or cultural lineage

Lineage may refer to:

Science

* Lineage (anthropology), a group that can demonstrate its common descent from an apical ancestor or a direct line of descent from an ancestor

* Lineage (evolution), a temporal sequence of individuals, populat ...

—with an intention to invoke, manipulate, or otherwise manifest supernatural forces, beings, or entities in the natural

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans ar ...

, incarnate world. It is a categorical yet often ambiguous term which has been used to refer to a wide variety of beliefs and practices, frequently considered separate from both religion and science.

Although connotations have varied from positive to negative at times throughout history, magic continues to have an important religious and medicinal role in many cultures today.

Within Western culture, magic has been linked to ideas of the Other, foreignness, and primitivism; indicating that it is "a powerful marker of cultural difference" and likewise, a non-modern phenomenon. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Western intellectuals perceived the practice of magic to be a sign of a primitive mentality and also commonly attributed it to marginalised groups of people.

In modern occultism and neopagan religions, many self-described magicians and witches regularly practice ritual magic; defining magic as a technique for bringing about change in the physical world through the force of one's will. This definition was popularised by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an influential British occultist, and since that time other religions (e.g. Wicca and LaVeyan Satanism) and magical systems (e.g. chaos magic

Chaos magic, also spelled chaos magick, is a modern tradition of magic. It initially emerged in England in the 1970s as part of the wider neo-pagan and magical subculture.

Drawing heavily from the occult beliefs of artist Austin Osman Spare, ...

k) have adopted it.

Etymology

The English words ''magic'', ''mage'' and ''magician'' come from the

The English words ''magic'', ''mage'' and ''magician'' come from the Latin term

__NOTOC__

This is a list of Wikipedia articles of Latin phrases and their translation into English.

''To view all phrases on a single, lengthy document, see: List of Latin phrases (full)''

The list also is divided alphabetically into twenty page ...

''magus'', through the Greek μάγος, which is from the Old Persian ''maguš''. (𐎶𐎦𐎢𐏁, 𐎶𐎦𐎢𐏁, magician). The Old Persian ''magu-'' is derived from the Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo ...

megʰ-''*magh'' (be able). The Persian term may have led to the Old Sinitic ''*Mγag'' (mage or shaman). The Old Persian form seems to have permeated ancient Semitic languages as the Talmudic Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

''magosh'', the Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

''amgusha'' (magician), and the Chaldean ''maghdim'' (wisdom and philosophy); from the first century BCE onwards, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

n ''magusai'' gained notoriety as magicians and soothsayers.

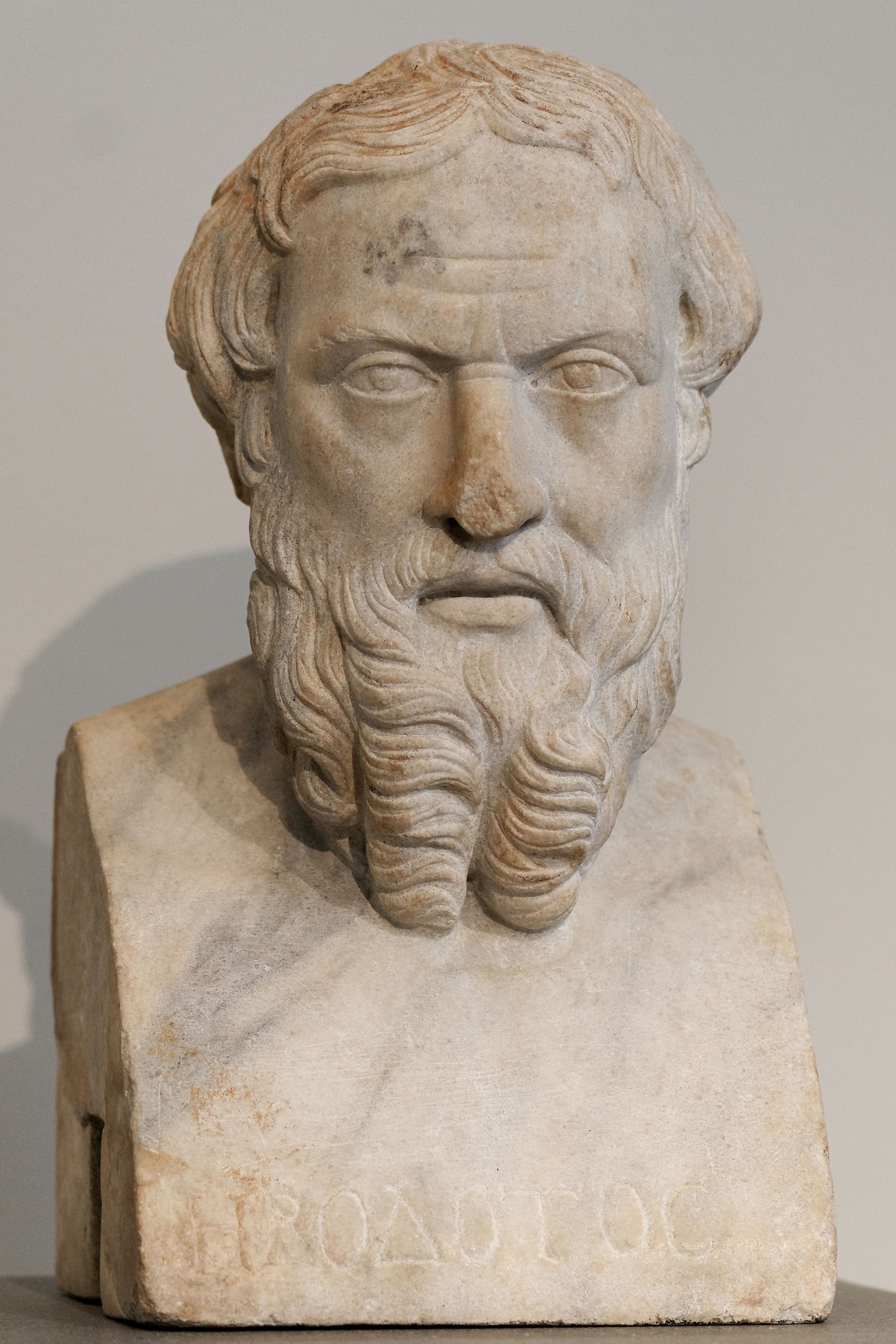

During the late-sixth and early-fifth centuries BCE, this term found its way into ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

, where it was used with negative connotations to apply to rites that were regarded as fraudulent, unconventional, and dangerous. The Latin language adopted this meaning of the term in the first century BCE. Via Latin, the concept became incorporated into Christian theology during the first century CE. Early Christians associated magic with demons, and thus regarded it as against Christian religion. This concept remained pervasive throughout the Middle Ages, when Christian authors categorised a diverse range of practices—such as enchantment, witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

, incantations, divination, necromancy, and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

—under the label "magic". In early modern Europe, Protestants often claimed that Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was magic rather than religion, and as Christian Europeans began colonizing other parts of the world in the sixteenth century, they labelled the non-Christian beliefs they encountered as magical. In that same period, Italian humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

reinterpreted the term in a positive sense to express the idea of natural magic. Both negative and positive understandings of the term recurred in Western culture over the following centuries.

Since the nineteenth century, academics in various disciplines have employed the term magic but have defined it in different ways and used it in reference to different things. One approach, associated with the anthropologists Edward Tylor

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (2 October 18322 January 1917) was an English anthropologist, and professor of anthropology.

Tylor's ideas typify 19th-century cultural evolutionism. In his works ''Primitive Culture'' (1871) and ''Anthropology'' ( ...

(1832–1917) and James G. Frazer (1854–1941), uses the term to describe beliefs in hidden sympathies between objects that allow one to influence the other. Defined in this way, magic is portrayed as the opposite to science. An alternative approach, associated with the sociologist Marcel Mauss (1872–1950) and his uncle Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), employs the term to describe private rites and ceremonies and contrasts it with religion, which it defines as a communal and organised activity. By the 1990s many scholars were rejecting the term's utility for scholarship. They argued that the label drew arbitrary lines between similar beliefs and practices that were alternatively considered religious, and that it constituted ethnocentric to apply the connotations of magic—rooted in Western and Christian history—to other cultures.

White, gray and black

White magic has traditionally been understood as the use of magic for selfless or helpful purposes, while black magic was used for selfish, harmful or evil purposes. With respect to the left-hand path and right-hand path dichotomy, black magic is the malicious, left hand counterpart of the benevolent white magic. There is no consensus as to what constitutes white, gray or black magic, asPhil Hine

Philip M. Hine is a British occultist and writer. He became known internationally through his written works ''Condensed Chaos'', ''Prime Chaos'', and ''Pseudonomicon'', as well as several essays on the topics of chaos magic and Cthulhu Mythos mag ...

says, "like many other aspects of occultism, what is termed to be 'black magic' depends very much on who is doing the defining." Gray magic, also called "neutral magic", is magic that is not performed for specifically benevolent reasons, but is also not focused towards completely hostile practices. Cicero, Chic & Cicero, Sandra Tabatha The Essential Golden Dawn: An Introduction to High Magic. Llewellyn Books. p. 87.

High and low

Historians and anthropologists have distinguished between practitioners who engage in high magic, and those who engage in low magic. High magic, also known as ceremonial magic or ritual magic, is more complex, involving lengthy and detailed rituals as well as sophisticated, sometimes expensive, paraphernalia. Low magic, also called natural magic, is associated with peasants and folklore and with simpler rituals such as brief, spoken spells. Low magic is also closely associated withwitchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

. Anthropologist Susan Greenwood writes that "Since the Renaissance, high magic has been concerned with drawing down forces and energies from heaven" and achieving unity with divinity. High magic is usually performed indoors while witchcraft is often performed outdoors.

History

Mesopotamia

Magic was invoked in many kinds of rituals and medical formulae, and to counteract evil omens. Defensive or legitimate magic in Mesopotamia (''asiputu'' or ''masmassutu'' in the Akkadian language) were incantations and ritual practices intended to alter specific realities. The ancient

Magic was invoked in many kinds of rituals and medical formulae, and to counteract evil omens. Defensive or legitimate magic in Mesopotamia (''asiputu'' or ''masmassutu'' in the Akkadian language) were incantations and ritual practices intended to alter specific realities. The ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

ns believed that magic was the only viable defense against demons, ghosts, and evil sorcerers. To defend themselves against the spirits of those they had wronged, they would leave offerings known as ''kispu'' in the person's tomb in hope of appeasing them. If that failed, they also sometimes took a figurine of the deceased and buried it in the ground, demanding for the gods to eradicate the spirit, or force it to leave the person alone.

The ancient Mesopotamians also used magic intending to protect themselves from evil sorcerers who might place curses on them. Black magic as a category didn't exist in ancient Mesopotamia, and a person legitimately using magic to defend themselves against illegitimate magic would use exactly the same techniques. The only major difference was the fact that curses were enacted in secret; whereas a defense against sorcery was conducted in the open, in front of an audience if possible. One ritual to punish a sorcerer was known as Maqlû, or "The Burning". The person viewed as being afflicted by witchcraft would create an effigy of the sorcerer and put it on trial at night. Then, once the nature of the sorcerer's crimes had been determined, the person would burn the effigy and thereby break the sorcerer's power over them.

The ancient Mesopotamians also performed magical rituals to purify themselves of sins committed unknowingly. One such ritual was known as the Šurpu The ancient Mesopotamian incantation series Šurpu begins ''enūma nēpešē ša šur-pu t'' 'eppušu'', “when you perform the rituals for (the series) ‘Burning,’” and was probably compiled in the middle Babylonian period, ca. 1350–105 ...

, or "Burning", in which the caster of the spell would transfer the guilt for all their misdeeds onto various objects such as a strip of dates, an onion, and a tuft of wool. The person would then burn the objects and thereby purify themself of all sins that they might have unknowingly committed. A whole genre of love spells existed. Such spells were believed to cause a person to fall in love with another person, restore love which had faded, or cause a male sexual partner to be able to sustain an erection when he had previously been unable. Other spells were used to reconcile a man with his patron deity or to reconcile a wife with a husband who had been neglecting her.

The ancient Mesopotamians made no distinction between rational science and magic. When a person became ill, doctors would prescribe both magical formulas to be recited as well as medicinal treatments. Most magical rituals were intended to be performed by an '' āšipu'', an expert in the magical arts. The profession was generally passed down from generation to generation and was held in extremely high regard and often served as advisors to kings and great leaders. An āšipu probably served not only as a magician, but also as a physician, a priest, a scribe, and a scholar.

The Sumerian god Enki, who was later syncretized with the East Semitic god Ea, was closely associated with magic and incantations; he was the patron god of the ''bārȗ'' and the ''ašipū'' and was widely regarded as the ultimate source of all arcane knowledge. The ancient Mesopotamians also believed in omens, which could come when solicited or unsolicited. Regardless of how they came, omens were always taken with the utmost seriousness.

Incantation bowls

A common set of shared assumptions about the causes of evil and how to avert it are found in a form of early protective magic called incantation bowl or magic bowls. The bowls were produced in the Middle East, particularly in Upper Mesopotamia andSyria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, what is now Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and fairly popular during the sixth to eighth centuries. The bowls were buried face down and were meant to capture demons. They were commonly placed under the threshold, courtyards, in the corner of the homes of the recently deceased and in cemeteries. A subcategory of incantation bowls are those used in Jewish magical practice. Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

incantation bowls are an important source of knowledge about Jewish magical practices.

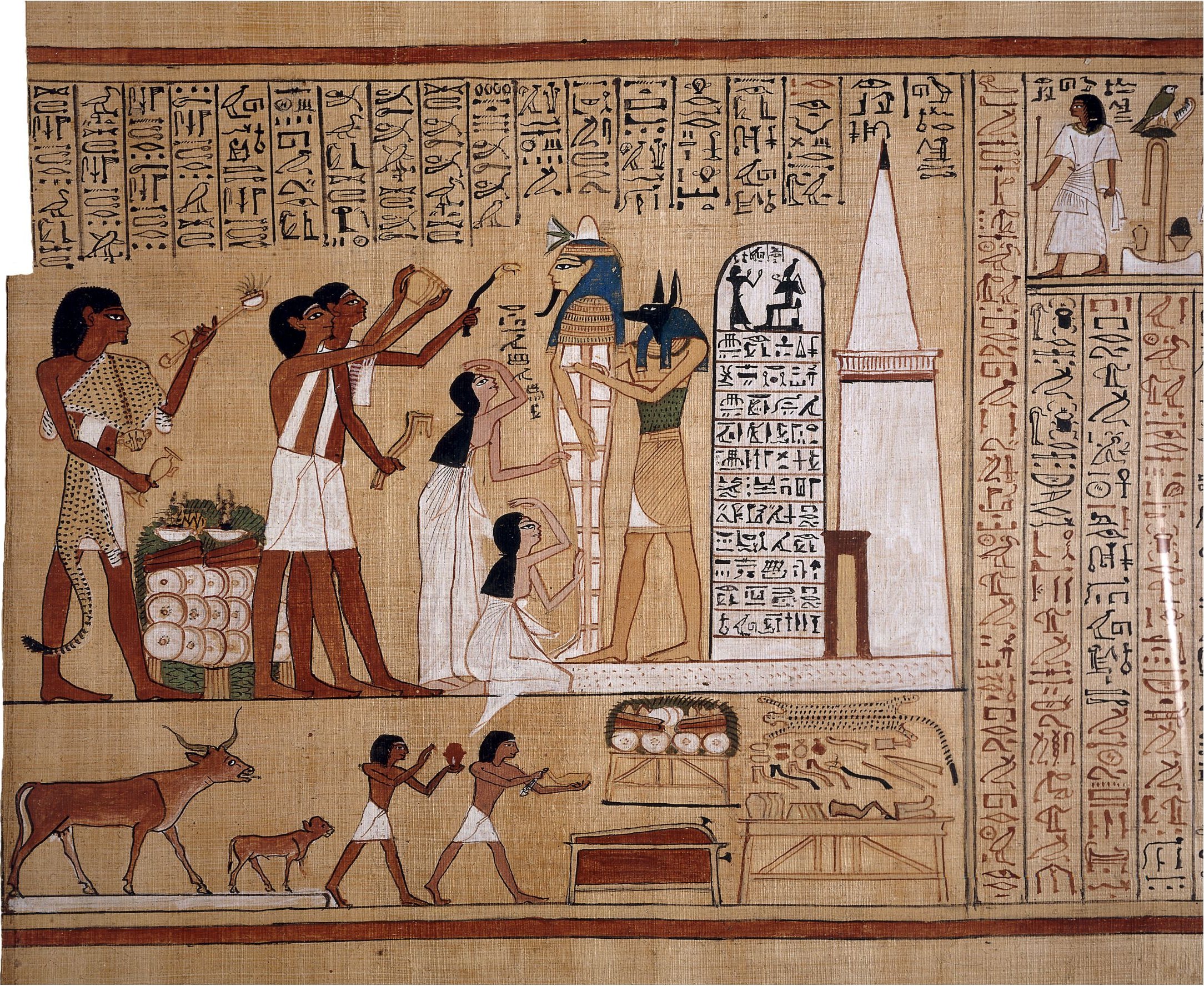

Egypt

In ancient Egypt (''Kemet'' in the Egyptian language), Magic (personified as the god ''heka'') was an integral part of religion and culture which is known to us through a substantial corpus of texts which are products of the Egyptian tradition.

While the category magic has been contentious for modern Egyptology, there is clear support for its applicability from ancient terminology.Ritner, R.K., Magic: An Overview in Redford, D.B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2001, p 321 The Coptic term ''hik'' is the descendant of the pharaonic term ''heka'', which, unlike its Coptic counterpart, had no connotation of impiety or illegality, and is attested from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman era. ''heka'' was considered morally neutral and was applied to the practices and beliefs of both foreigners and Egyptians alike. The Instructions for Merikare informs us that ''heka'' was a beneficence gifted by the creator to humanity "... in order to be weapons to ward off the blow of events".

Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of ''heka'' underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

The main principle of ''heka'' is centered on the power of words to bring things into being. Karenga explains the pivotal power of words and their vital ontological role as the primary tool used by the creator to bring the manifest world into being. Because humans were understood to share a divine nature with the gods, ''snnw ntr'' (images of the god), the same power to use words creatively that the gods have is shared by humans.

In ancient Egypt (''Kemet'' in the Egyptian language), Magic (personified as the god ''heka'') was an integral part of religion and culture which is known to us through a substantial corpus of texts which are products of the Egyptian tradition.

While the category magic has been contentious for modern Egyptology, there is clear support for its applicability from ancient terminology.Ritner, R.K., Magic: An Overview in Redford, D.B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2001, p 321 The Coptic term ''hik'' is the descendant of the pharaonic term ''heka'', which, unlike its Coptic counterpart, had no connotation of impiety or illegality, and is attested from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman era. ''heka'' was considered morally neutral and was applied to the practices and beliefs of both foreigners and Egyptians alike. The Instructions for Merikare informs us that ''heka'' was a beneficence gifted by the creator to humanity "... in order to be weapons to ward off the blow of events".

Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of ''heka'' underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

The main principle of ''heka'' is centered on the power of words to bring things into being. Karenga explains the pivotal power of words and their vital ontological role as the primary tool used by the creator to bring the manifest world into being. Because humans were understood to share a divine nature with the gods, ''snnw ntr'' (images of the god), the same power to use words creatively that the gods have is shared by humans.

''Book of the Dead''

The interior walls of the pyramid of Unas, the final pharaoh of the Egyptian Fifth Dynasty, are covered in hundreds of magical spells and inscriptions, running from floor to ceiling in vertical columns. These inscriptions are known as thePyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterran ...

and they contain spells needed by the pharaoh in order to survive in the Afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving es ...

. The Pyramid Texts were strictly for royalty only; the spells were kept secret from commoners and were written only inside royal tombs. During the chaos and unrest of the First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history, spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom. It comprises the Seventh (although this is mostly considered spuriou ...

, however, tomb robbers broke into the pyramids and saw the magical inscriptions. Commoners began learning the spells and, by the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, commoners began inscribing similar writings on the sides of their own coffins, hoping that doing so would ensure their own survival in the afterlife. These writings are known as the Coffin Texts

The Coffin Texts are a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary spells written on coffins beginning in the First Intermediate Period. They are partially derived from the earlier Pyramid Texts, reserved for royal use only, but contain substantial ...

.

After a person died, his or her corpse would be mummified and wrapped in linen bandages to ensure that the deceased's body would survive for as long as possible because the Egyptians believed that a person's soul could only survive in the afterlife for as long as his or her physical body survived here on earth. The last ceremony before a person's body was sealed away inside the tomb was known as the Opening of the Mouth. In this ritual, the priests would touch various magical instruments to various parts of the deceased's body, thereby giving the deceased the ability to see, hear, taste, and smell in the afterlife.

Amulets

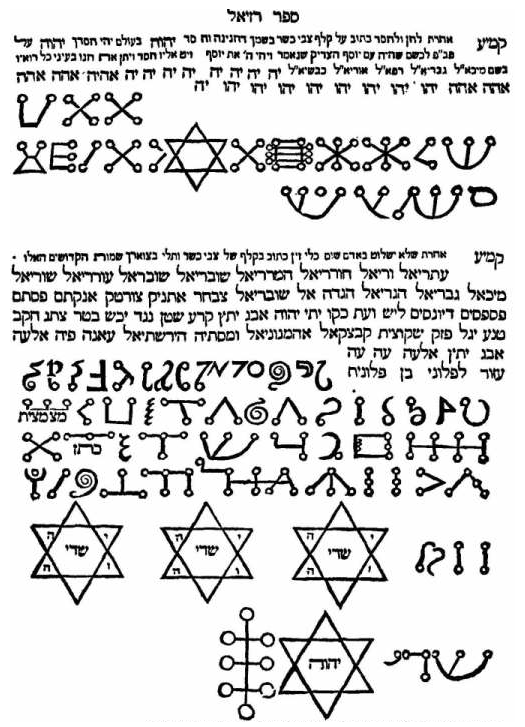

The use of amulets, (''meket'') was widespread among both living and dead ancient Egyptians.Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, p. 170 They were used for protection and as a means of "...reaffirming the fundamental fairness of the universe". The oldest amulets found are from the predynastic Badarian Period, and they persisted through to Roman times.Judea

''Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'' (Jewish religious law) forbids divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history ...

and other forms of soothsaying, and the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

lists many persistent yet condemned divining practices. Practical Kabbalah in historical Judaism, is a branch of the Jewish mystical tradition that concerns the use of magic. It was considered permitted white magic

White magic has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for selfless purposes. Practitioners of white magic have been given titles such as wise men or women, healers

Alternative medicine is any practice that aims t ...

by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiritual source from Qliphoth

In the Zohar, Lurianic Kabbalah and Hermetic Qabalah, the ''qliphoth/qlippoth/qlifot'' or ''kelipot'' ( ''qəlīpōṯ'', originally Aramaic: ''qəlīpīn'', plural of ''qəlīpā''; literally "peels", "shells", or "husks"), are the represe ...

realms of evil if performed under circumstances that were holy

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

(Q-D-Š

''Q-D-Š'' is a triconsonantal Semitic root meaning " sacred, holy", derived from a concept central to ancient Semitic religion. From a basic verbal meaning "to consecrate, to purify", it could be used as an adjective meaning "holy", or as a ...

) and pure (טומאה וטהרה, ''tvmh vthrh''). The concern of overstepping Judaism's strong prohibitions of impure magic ensured it remained a minor tradition in Jewish history. Its teachings include the use of Divine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine< ...

and angelic names for amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protect ...

s and incantations.Elber, Mark. ''The Everything Kabbalah Book: Explore This Mystical Tradition--From Ancient Rituals to Modern Day Practices'', p. 137. Adams Media, 2006. These magical practices of Judaic folk religion which became part of practical Kabbalah date from Talmudic times. The Talmud mentions the use of charms for healing, and a wide range of magical cures were sanctioned by rabbis. It was ruled that any practice actually producing a cure was not to be regarded superstitiously and there has been the widespread practice of medicinal amulets, and folk remedies ''(segullot)'' in Jewish societies across time and geography.

Although magic was forbidden by Levitical law in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Second Temple period The Second Temple period in Jewish history lasted approximately 600 years (516 BCE - 70 CE), during which the Second Temple existed. It started with the return to Zion and the construction of the Second Temple, while it ended with the First Je ...

, and particularly well documented in the period following the destruction of the temple into the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries CE.

'' Second Temple period The Second Temple period in Jewish history lasted approximately 600 years (516 BCE - 70 CE), during which the Second Temple existed. It started with the return to Zion and the construction of the Second Temple, while it ended with the First Je ...

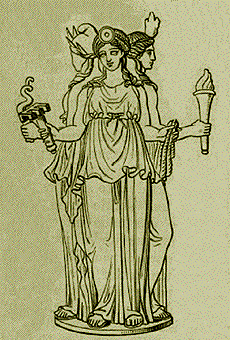

Greco-Roman world

The English word magic has its origins in

The English word magic has its origins in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

.

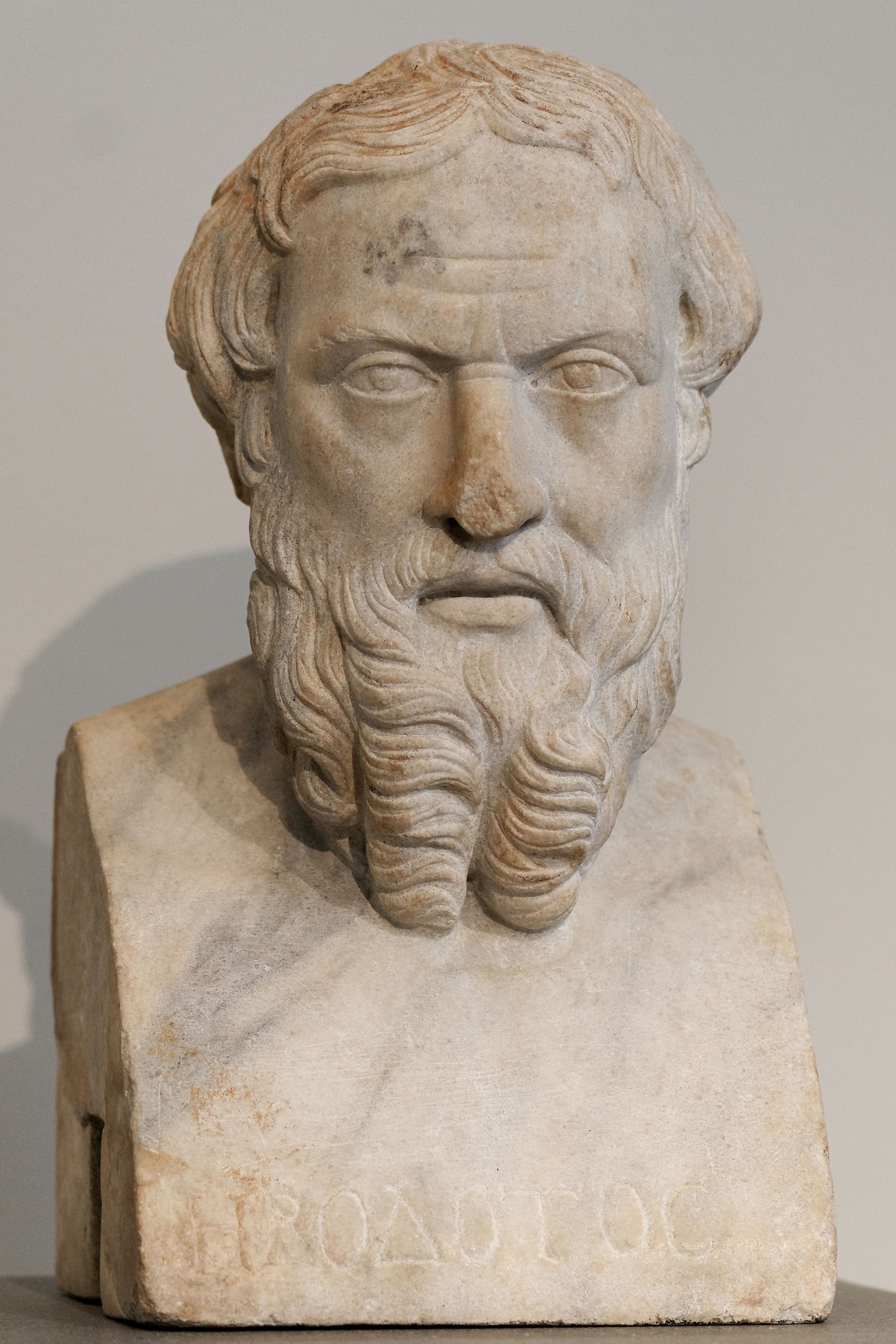

During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, the Persian ''maguš'' was Graecicized and introduced into the ancient Greek language as ''μάγος'' and ''μαγεία''. In doing so it transformed meaning, gaining negative connotations, with the ''magos'' being regarded as a charlatan whose ritual practices were fraudulent, strange, unconventional, and dangerous. As noted by Davies, for the ancient Greeks—and subsequently for the ancient Romans—"magic was not distinct from religion but rather an unwelcome, improper expression of it—the religion of the other". The historian Richard Gordon suggested that for the ancient Greeks, being accused of practicing magic was "a form of insult".

This change in meaning was influenced by the military conflicts that the Greek city-states were then engaged in against the Persian Empire. In this context, the term makes appearances in such surviving text as Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

' ''Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'', Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

' ''De morbo sacro'', and Gorgias

Gorgias (; grc-gre, Γοργίας; 483–375 BC) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Along with Protagoras, he forms the first generation of Sophists. Several ...

' ''Encomium of Helen

Gorgias (; grc-gre, Γοργίας; 483–375 BC) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Along with Protagoras, he forms the first generation of Sophists. Several ...

''. In Sophocles' play, for example, the character Oedipus

Oedipus (, ; grc-gre, Οἰδίπους "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby ...

derogatorily refers to the seer Tiresius

In Greek mythology, Tiresias (; grc, Τειρεσίας, Teiresías) was a blind prophet of Apollo in Thebes, famous for clairvoyance and for being transformed into a woman for seven years. He was the son of the shepherd Everes and the nym ...

as a ''magos''—in this context meaning something akin to quack or charlatan—reflecting how this epithet was no longer reserved only for Persians.

In the first century BCE, the Greek concept of the ''magos'' was adopted into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and used by a number of ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–50 ...

writers as ''magus'' and ''magia''. The earliest known Latin use of the term was in Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's ''Eclogue

An eclogue is a poem in a classical style on a pastoral subject. Poems in the genre are sometimes also called bucolics.

Overview

The form of the word ''eclogue'' in contemporary English developed from Middle English , which came from Latin , wh ...

'', written around 40 BCE, which makes reference to ''magicis... sacris'' (magic rites). The Romans already had other terms for the negative use of supernatural powers, such as ''veneficus'' and ''saga''. The Roman use of the term was similar to that of the Greeks, but placed greater emphasis on the judicial application of it. Within the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, laws would be introduced criminalising things regarded as magic.

In ancient Roman society, magic was associated with societies to the east of the empire; the first century CE writer Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

for instance claimed that magic had been created by the Iranian philosopher Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label= Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism. He is ...

, and that it had then been brought west into Greece by the magician Osthanes

Ostanes (from Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic period onwards. Together with Pseudo-Zo ...

, who accompanied the military campaigns of the Persian King Xerxes.

Ancient Greek scholarship of the 20th century, almost certainly influenced by Christianising preconceptions of the meanings of magic and religion

Magical thinking in various forms is a cultural universal and an important aspect of religion. Magic is prevalent in all societies, regardless of whether they have organized religion or more general systems of animism or shamanism. Religion and ...

, and the wish to establish Greek culture as the foundation of Western rationality, developed a theory of ancient Greek magic as primitive and insignificant, and thereby essentially separate from Homeric

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

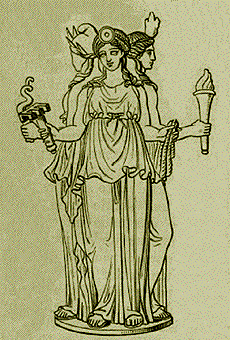

, communal (''polis'') religion. Since the last decade of the century, however, recognising the ubiquity and respectability of acts such as ''katadesmoi'' ( binding spells), described as magic by modern and ancient observers alike, scholars have been compelled to abandon this viewpoint. The Greek word ''mageuo'' (practice magic) itself derives from the word '' Magos'', originally simply the Greek name for a Persian tribe known for practicing religion. Non-civic mystery cults have been similarly re-evaluated:

'' Katadesmoi'' (Latin: '' defixiones)'', curses inscribed on wax or lead tablets and buried underground, were frequently executed by all strata of Greek society, sometimes to protect the entire ''polis''. Communal curses carried out in public declined after the Greek classical period, but private curses remained common throughout antiquity. They were distinguished as magical by their individualistic, instrumental and sinister qualities. These qualities, and their perceived deviation from inherently mutable cultural constructs of normality, most clearly delineate ancient magic from the religious rituals of which they form a part.

A large number of magical papyri, in Greek, Coptic, and Demotic, have been recovered and translated. They contain early instances of:

* the use of magic words said to have the power to command spirits;

* the use of mysterious symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

s or sigils which are thought to be useful when invoking or evoking spirits.

The practice of magic was banned in the late Roman world, and the ''Codex Theodosianus

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' (Eng. Theodosian Code) was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 42 ...

'' (438 AD) states: If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician...should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank.

Middle Ages

In the first century CE, early Christian authors absorbed theGreco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

concept of magic and incorporated it into their developing Christian theology. These Christians retained the already implied Greco-Roman negative stereotypes of the term and extented them by incorporating conceptual patterns borrowed from Jewish thought, in particular the opposition of magic and miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

. Some early Christian authors followed the Greek-Roman thinking by ascribing the origin of magic to the human realm, mainly to Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label= Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism. He is ...

and Osthanes

Ostanes (from Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic period onwards. Together with Pseudo-Zo ...

. The Christian view was that magic was a product of the Babylonians, Persians, or Egyptians. The Christians shared with earlier classical culture the idea that magic was something distinct from proper religion, although drew their distinction between the two in different ways.

For early Christian writers like

For early Christian writers like Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

, magic did not merely constitute fraudulent and unsanctioned ritual practices, but was the very opposite of religion because it relied upon cooperation from demons, the henchmen of Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an entity in the Abrahamic religions that seduces humans into sin or falsehoo ...

. In this, Christian ideas of magic were closely linked to the Christian category of paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

, and both magic and paganism were regarded as belonging under the broader category of ''superstitio'' (superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs ...

), another term borrowed from pre-Christian Roman culture. This Christian emphasis on the inherent immorality and wrongness of magic as something conflicting with good religion was far starker than the approach in the other large monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfor ...

religions of the period, Judaism and Islam. For instance, while Christians regarded demons as inherently evil, the jinn

Jinn ( ar, , ') – also romanized as djinn or anglicized as genies (with the broader meaning of spirit or demon, depending on sources)

– are invisible creatures in early pre-Islamic Arabian religious systems and later in Islamic ...

—comparable entities in Islamic mythology—were perceived as more ambivalent figures by Muslims.

The model of the magician in Christian thought was provided by Simon Magus

Simon Magus (Greek Σίμων ὁ μάγος, Latin: Simon Magus), also known as Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, was a religious figure whose confrontation with Peter is recorded in Acts . The act of simony, or paying for position, is ...

, (Simon the Magician), a figure who opposed Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

in both the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its messag ...

and the apocryphal yet influential Acts of Peter

The Acts of Peter is one of the earliest of the apocryphal Acts of the Apostles in Christianity, dating to the late 2nd century AD. The majority of the text has survived only in the Latin translation of the Codex Vercellensis, under the title ...

. The historian Michael D. Bailey stated that in medieval Europe, magic was a "relatively broad and encompassing category". Christian theologians believed that there were multiple different forms of magic, the majority of which were types of divination, for instance, Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville ( la, Isidorus Hispalensis; c. 560 – 4 April 636) was a Spanish scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of ...

produced a catalogue of things he regarded as magic in which he listed divination by the four elements i.e. geomancy

Geomancy ( Greek: γεωμαντεία, "earth divination") is a method of divination that interprets markings on the ground or the patterns formed by tossed handfuls of soil, rocks, or sand. The most prevalent form of divinatory geomancy in ...

, hydromancy, aeromancy

Aeromancy (from Greek ἀήρ ''aḗr'', "air", and ''manteia'', "divination") is divination conducted by interpreting atmospheric conditions. Alternate spellings include arologie, aeriology and aërology.

Practice

Aeromancy uses cloud formati ...

, and pyromancy

Pyromancy (from Greek ''pyr,'' “fire,” and ''manteia,'' “divination”) is the art of divination by means of fire. ...

, as well as by observation of natural phenomena e.g. the flight of birds and astrology. He also mentioned enchantment and ligatures (the medical use of magical objects bound to the patient) as being magical. Medieval Europe also saw magic come to be associated with the Old Testament figure of Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

; various grimoire

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and ...

s, or books outlining magical practices, were written that claimed to have been written by Solomon, most notably the Key of Solomon

The ''Key of Solomon'' ( la, Clavicula Salomonis; he, מפתח שלמה []) (Also known as "The Greater Key of Solomon") is a pseudepigraphical grimoire (also known as a book of spells) attributed to Solomon, King Solomon. It probably dates b ...

.

In early medieval Europe, ''magia'' was a term of condemnation. In medieval Europe, Christians often suspected Muslims and Jews of engaging in magical practices; in certain cases, these perceived magical rites—including the alleged Jewish sacrifice of Christian children—resulted in Christians massacring these religious minorities. Christian groups often also accused other, rival Christian groups—which they regarded as heretical—of engaging in magical activities. Medieval Europe also saw the term ''maleficium'' applied to forms of magic that were conducted with the intention of causing harm. The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: ''sorcière'' in French, ''Hexe'' in German, ''strega'' in Italian, and ''bruja'' in Spanish. The English term for malevolent practitioners of magic, witch, derived from the earlier Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

term ''wicce''.

Ars Magica or magic is a major component and supporting contribution to the belief and practice of spiritual, and in many cases, physical healing throughout the Middle Ages. Emanating from many modern interpretations lies a trail of misconceptions about magic, one of the largest revolving around wickedness or the existence of nefarious beings who practice it. These misinterpretations stem from numerous acts or rituals that have been performed throughout antiquity, and due to their exoticism from the commoner's perspective, the rituals invoked uneasiness and an even stronger sense of dismissal.

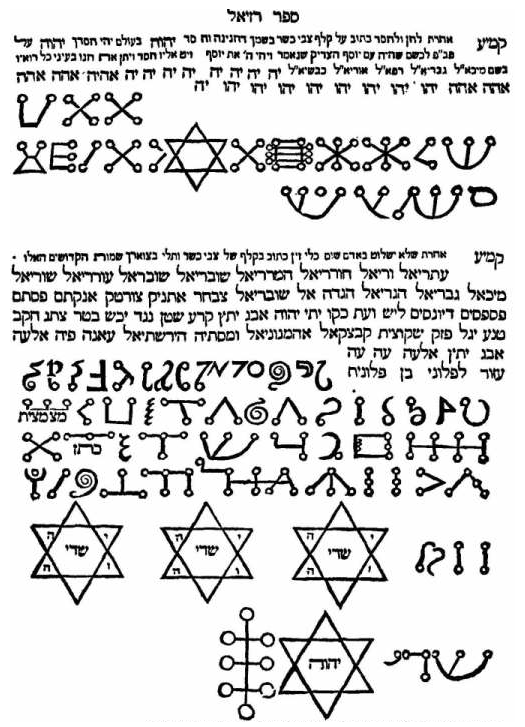

In the Medieval Jewish view, the separation of the

In the Medieval Jewish view, the separation of the mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

and magical elements of Kabbalah, dividing it into speculative theological Kabbalah (''Kabbalah Iyyunit'') with its meditative traditions, and theurgic practical Kabbalah (''Kabbalah Ma'asit''), had occurred by the beginning of the 14th century.

One societal force in the Middle Ages more powerful than the singular commoner, the Christian Church, rejected magic as a whole because it was viewed as a means of tampering with the natural world in a supernatural manner associated with the biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of ...

verses of Deuteronomy 18:9–12. Despite the many negative connotations which surround the term magic, there exist many elements that are seen in a divine or holy light.

Diversified instruments or rituals used in medieval magic include, but are not limited to: various amulets, talismans, potions, as well as specific chants, dances, and prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deifie ...

s. Along with these rituals are the adversely imbued notions of demonic participation which influence of them. The idea that magic was devised, taught, and worked by demons would have seemed reasonable to anyone who read the Greek magical papyri or the Sefer-ha-Razim and found that healing magic appeared alongside rituals for killing people, gaining wealth, or personal advantage, and coercing women into sexual submission. Archaeology is contributing to a fuller understanding of ritual practices performed in the home, on the body and in monastic and church settings.

The Islamic reaction towards magic did not condemn magic in general and distinguished between magic which can heal sickness and possession, and sorcery. The former is therefore a special gift from God, while the latter is achieved through help of Jinn

Jinn ( ar, , ') – also romanized as djinn or anglicized as genies (with the broader meaning of spirit or demon, depending on sources)

– are invisible creatures in early pre-Islamic Arabian religious systems and later in Islamic ...

and devils

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in many and various cultures and religious traditions.

Devil or Devils may also refer to:

* Satan

* Devil in Christianity

* Demon

* Folk devil

Art, entertainment, and media

Film and ...

. Ibn al-Nadim

Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Nadīm ( ar, ابو الفرج محمد بن إسحاق النديم), also ibn Abī Ya'qūb Isḥāq ibn Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Warrāq, and commonly known by the ''nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadīm ...

held that exorcists gain their power by their obedience to God, while sorcerers please the devils by acts of disobedience and sacrifices and they in return do him a favor. According to Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

, Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yusuf al-Shubarbuli was able to walk on water due to his piety. According to the Quran 2:102, magic was also taught to humans by devils and the fallen angels Harut and Marut

Harut and Marut ( ar, هَارُوْت وَمَارُوْت, Hārūt wa-Mārūt) are two angels mentioned in Quran 2:102, who are said to have been located in Babylon. According to some narratives, those two angels were in the time of Idris. Th ...

.

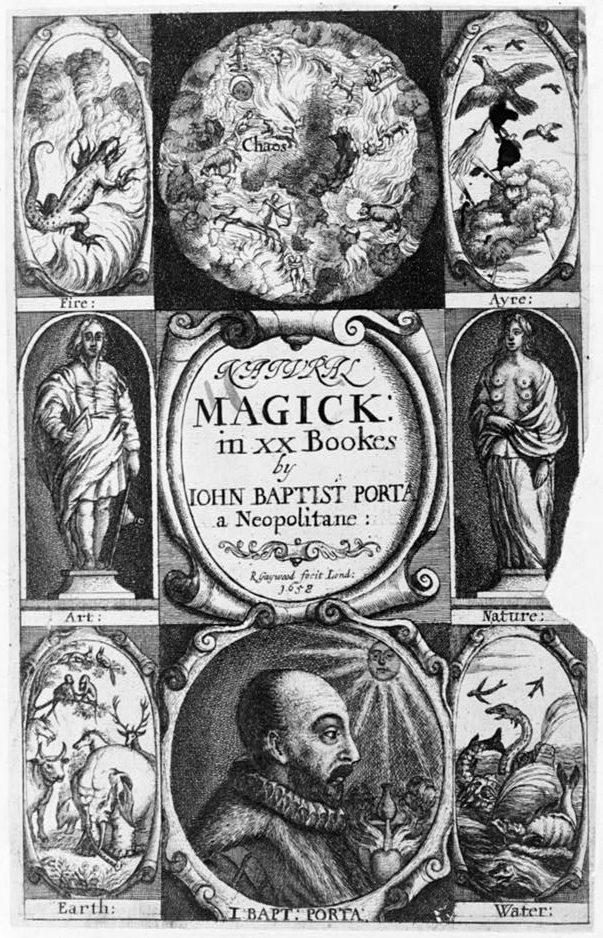

During the early modern period, the concept of magic underwent a more positive reassessment through the development of the concept of '' magia naturalis'' (natural magic). This was a term introduced and developed by two Italian humanists,

During the early modern period, the concept of magic underwent a more positive reassessment through the development of the concept of '' magia naturalis'' (natural magic). This was a term introduced and developed by two Italian humanists, Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a revive ...

and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (24 February 1463 – 17 November 1494) was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, philosophy, ...

. For them, ''magia'' was viewed as an elemental force pervading many natural processes, and thus was fundamentally distinct from the mainstream Christian idea of demonic magic. Their ideas influenced an array of later philosophers and writers, among them Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

He ...

, Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno (; ; la, Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmolog ...

, Johannes Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin (; sometimes called Johannes; 29 January 1455 – 30 June 1522) was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew, whose work also took him to modern-day Austria, Switzerland, and Italy and France. Most of Reuchlin ...

, and Johannes Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius (; 1 February 1462 – 13 December 1516), born Johann Heidenberg, was a German Benedictine abbot and a polymath who was active in the German Renaissance as a lexicographer, chronicler, cryptographer, and occultist. He is co ...

. According to the historian Richard Kieckhefer, the concept of ''magia naturalis'' took "firm hold in European culture" during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, attracting the interest of natural philosophers of various theoretical orientations, including Aristotelians, Neoplatonists

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

, and Hermeticists.

Adherents of this position argued that ''magia'' could appear in both good and bad forms; in 1625, the French librarian Gabriel Naudé

Gabriel Naudé (2 February 1600 – 10 July 1653) was a French librarian and scholar. He was a prolific writer who produced works on many subjects including politics, religion, history and the supernatural. An influential work on library science ...

wrote his ''Apology for all the Wise Men Falsely Suspected of Magic'', in which he distinguished "Mosoaicall Magick"—which he claimed came from God and included prophecies, miracles, and speaking in tongues

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is a practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid vocalizing of sp ...

—from "geotick" magic caused by demons. While the proponents of ''magia naturalis'' insisted that this did not rely on the actions of demons, critics disagreed, arguing that the demons had simply deceived these magicians. By the seventeenth century the concept of ''magia naturalis'' had moved in increasingly 'naturalistic' directions, with the distinctions between it and science becoming blurred. The validity of ''magia naturalis'' as a concept for understanding the universe then came under increasing criticism during the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

in the eighteenth century.

Despite the attempt to reclaim the term ''magia'' for use in a positive sense, it did not supplant traditional attitudes toward magic in the West, which remained largely negative. At the same time as ''magia naturalis'' was attracting interest and was largely tolerated, Europe saw an active persecution of accused witches believed to be guilty of ''maleficia''. Reflecting the term's continued negative associations, Protestants often sought to denigrate Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

sacramental and devotional practices as being magical rather than religious. Many Roman Catholics were concerned by this allegation and for several centuries various Roman Catholic writers devoted attention to arguing that their practices were religious rather than magical. At the same time, Protestants often used the accusation of magic against other Protestant groups which they were in contest with. In this way, the concept of magic was used to prescribe what was appropriate as religious belief and practice.

Similar claims were also being made in the Islamic world during this period. The Arabian cleric Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab—founder of Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, and ...

—for instance condemned a range of customs and practices such as divination and the veneration of spirits as ''sihr'', which he in turn claimed was a form of ''shirk

Shirk may refer to:

* Shirk (surname)

* Shirk (Islam), in Islam, the sin of idolatry or associating beings or things with Allah

* Shirk, Iran, a village in South Khorasan Province, Iran

* Shirk-e Sorjeh, a village in South Khorasan Province, Iran ...

'', the sin of idolatry.

The Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

saw a resurgence in hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

and Neo-Platonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

varieties of ceremonial magic. The Renaissance, on the other hand, saw the rise of science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

, in such forms as the dethronement of the Ptolemaic theory of the universe, the distinction of astronomy from astrology, and of chemistry from alchemy.

There was great uncertainty in distinguishing practices of superstition, occultism, and perfectly sound scholarly knowledge or pious ritual. The intellectual and spiritual tensions erupted in the Early Modern witch craze, further reinforced by the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

, especially in Germany, England, and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

.

In Hasidism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism ( Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of cont ...

, the displacement of practical Kabbalah using directly magical means, by conceptual and meditative trends gained much further emphasis, while simultaneously instituting meditative theurgy

Theurgy (; ) describes the practice of rituals, sometimes seen as magical in nature, performed with the intention of invoking the action or evoking the presence of one or more deities, especially with the goal of achieving henosis (uniting w ...

for material blessings at the heart of its social mysticism. Hasidism internalised Kabbalah through the psychology of deveikut (cleaving to God), and cleaving to the Tzadik

Tzadik ( he, צַדִּיק , "righteous ne, also ''zadik'', ''ṣaddîq'' or ''sadiq''; pl. ''tzadikim'' ''ṣadiqim'') is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. Th ...

(Hasidic Rebbe). In Hasidic doctrine, the tzaddik channels Divine spiritual and physical bounty to his followers by altering the Will of God (uncovering a deeper concealed Will) through his own deveikut and self-nullification. Dov Ber of Mezeritch

Dov Ber ben Avraham of Mezeritch ( yi, דֹּב בֶּער מִמֶּזְרִיטְשְׁ; died December 1772 OS), also known as the '' Maggid of Mezeritch'', was a disciple of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (the Baal Shem Tov), the founder of Hasidi ...

is concerned to distinguish this theory of the Tzadik's will altering and deciding the Divine Will, from directly magical process.

In the sixteenth century, European societies began to conquer and colonise other continents around the world, and as they did so they applied European concepts of magic and witchcraft to practices found among the peoples whom they encountered. Usually, these European colonialists regarded the natives as primitives and savages whose belief systems were diabolical and needed to be eradicated and replaced by Christianity. Because Europeans typically viewed these non-European peoples as being morally and intellectually inferior to themselves, it was expected that such societies would be more prone to practicing magic. Women who practiced traditional rites were labelled as witches by the Europeans.

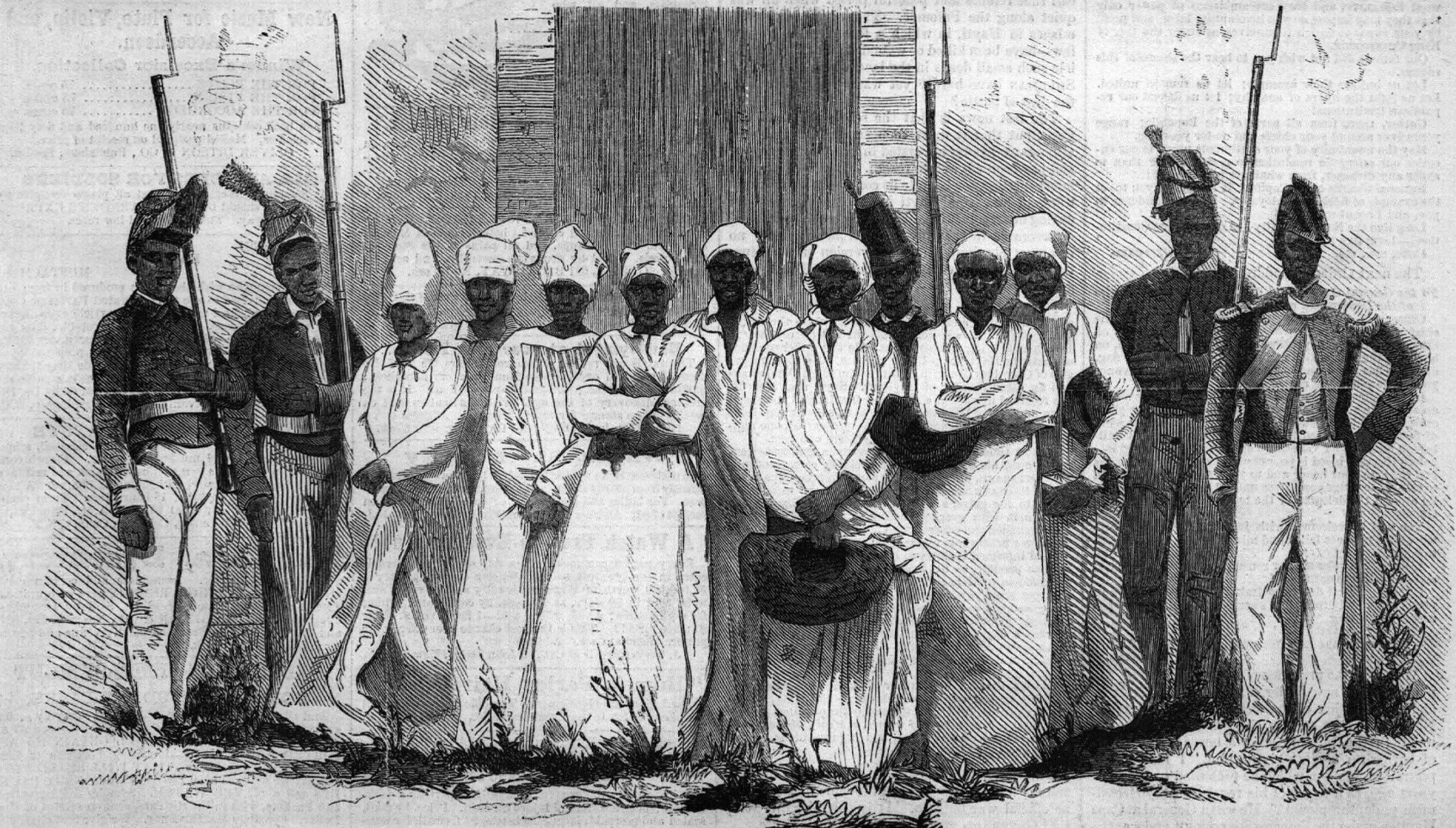

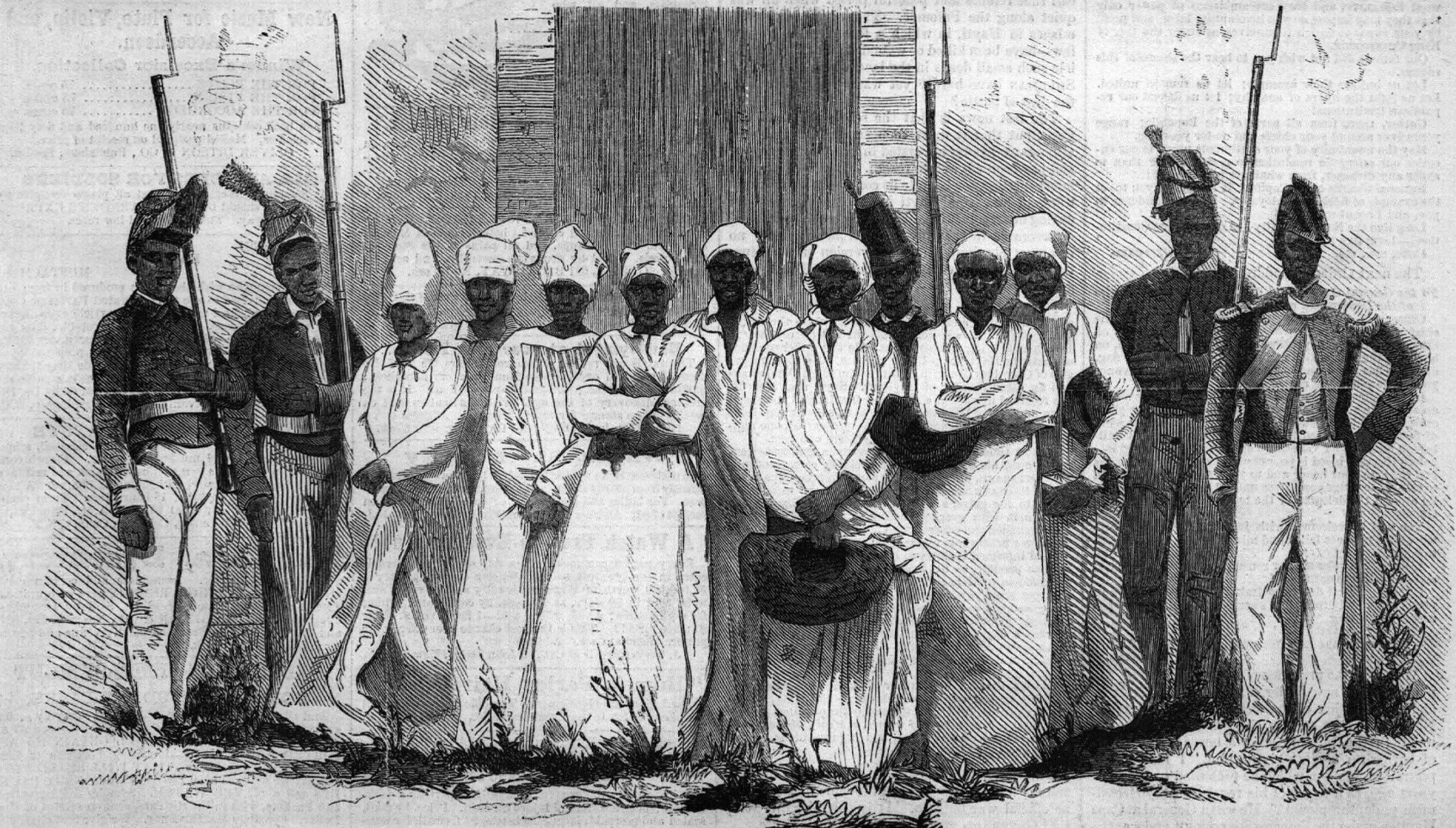

In various cases, these imported European concepts and terms underwent new transformations as they merged with indigenous concepts. In West Africa, for instance, Portuguese travellers introduced their term and concept of the ''feitiçaria'' (often translated as sorcery) and the ''feitiço'' (spell) to the native population, where it was transformed into the concept of the fetish. When later Europeans encountered these West African societies, they wrongly believed that the ''fetiche'' was an indigenous African term rather than the result of earlier inter-continental encounters. Sometimes, colonised populations themselves adopted these European concepts for their own purposes. In the early nineteenth century, the newly independent Haitian government of

In the sixteenth century, European societies began to conquer and colonise other continents around the world, and as they did so they applied European concepts of magic and witchcraft to practices found among the peoples whom they encountered. Usually, these European colonialists regarded the natives as primitives and savages whose belief systems were diabolical and needed to be eradicated and replaced by Christianity. Because Europeans typically viewed these non-European peoples as being morally and intellectually inferior to themselves, it was expected that such societies would be more prone to practicing magic. Women who practiced traditional rites were labelled as witches by the Europeans.

In various cases, these imported European concepts and terms underwent new transformations as they merged with indigenous concepts. In West Africa, for instance, Portuguese travellers introduced their term and concept of the ''feitiçaria'' (often translated as sorcery) and the ''feitiço'' (spell) to the native population, where it was transformed into the concept of the fetish. When later Europeans encountered these West African societies, they wrongly believed that the ''fetiche'' was an indigenous African term rather than the result of earlier inter-continental encounters. Sometimes, colonised populations themselves adopted these European concepts for their own purposes. In the early nineteenth century, the newly independent Haitian government of Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines ( Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1805 constitution. Under Dessalines, Haiti be ...

began to suppress the practice of Vodou, and in 1835 Haitian law-codes categorised all Vodou practices as ''sortilège'' (sorcery/witchcraft), suggesting that it was all conducted with harmful intent, whereas among Vodou practitioners the performance of harmful rites was already given a separate and distinct category, known as ''maji''.

Baroque period

Writers on occult or magical topics during this period includeMichael Sendivogius

Michael Sendivogius (; pl, Michał Sędziwój; 2 February 1566 – 1636) was a Polish alchemist, philosopher, and medical doctor. A pioneer of chemistry, he developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other chemi ...