Macquarie Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Macquarie Island is a

. Antarctica.gov.au. Retrieved on 16 July 2013. In the same year, Captain Smith described in more detail what is presumably the same wreck and incorrectly speculated that it belonged to French explorer

. Parks.tas.gov.au (24 June 2013). Retrieved 16 July 2013. On 25 May 1948, the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) established its expedition headquarters on Macquarie Island. In March 1949, they were visited by the Fifth French Antarctic Expedition on their return trip from

Macquarie Island is about long and wide, with an area of . The island consists of plateaus at north and south ends, each of elevation, joined by a low, narrow isthmus. The high points include Mount Elder on the northeast coastal ridge at , and Mounts Hamilton and Fletcher in the south at . The island is almost equidistant between the island of Tasmania and the Antarctic continent's Anderson Peninsula, about from either point. In addition, Macquarie Island is about southwest of Auckland Island, and north of the Balleny Islands.

Near Macquarie Island are two small groups of minor islands: the Judge and Clerk Islets (), to the north, in area, and the Bishop and Clerk Islets (), to the south, in area. Like Macquarie Island, both groups are part of the state of

Macquarie Island is about long and wide, with an area of . The island consists of plateaus at north and south ends, each of elevation, joined by a low, narrow isthmus. The high points include Mount Elder on the northeast coastal ridge at , and Mounts Hamilton and Fletcher in the south at . The island is almost equidistant between the island of Tasmania and the Antarctic continent's Anderson Peninsula, about from either point. In addition, Macquarie Island is about southwest of Auckland Island, and north of the Balleny Islands.

Near Macquarie Island are two small groups of minor islands: the Judge and Clerk Islets (), to the north, in area, and the Bishop and Clerk Islets (), to the south, in area. Like Macquarie Island, both groups are part of the state of

The flora has taxonomic affinities with other subantarctic islands, especially those south of New Zealand. Plants rarely grow over in height, though the tussock-forming grass '' Poa foliosa'' can grow up to tall in sheltered areas. There are over 45

The flora has taxonomic affinities with other subantarctic islands, especially those south of New Zealand. Plants rarely grow over in height, though the tussock-forming grass '' Poa foliosa'' can grow up to tall in sheltered areas. There are over 45

File:MacquarieIsland7.JPG, A Macquarie Island beach

File:MacquarieIsland4.JPG, Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island, an 1882 paper in the ''Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand''

Macquarie Island station

(Australian Antarctic Division)

Macquarie Island station webcamMacquarie Island Conservation FoundationA picture of Macquarie Island (historical heritage - Remnants of seal hunting)

{{Authority control

subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a physiographic region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46th parallel south, 46° and 60th parallel south, 60° south of t ...

island in the south-western Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

, about halfway between New Zealand and Antarctica. It has been governed as a part of Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, Australia, since 1880. It became a Tasmanian State Reserve in 1978 and was inscribed as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

in 1997.

Macquarie Island is an exposed portion of the Macquarie Ridge and is located where the Australian Plate meets the Pacific Plate.

The island is home to the entire royal penguin population during their annual nesting season. Ecologically, the island is part of the Antipodes Subantarctic Islands tundra ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) is an ecological and geographic area that exists on multiple different levels, defined by type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of land or water, and c ...

.

History

19th century

Frederick Hasselborough, an Australian, discovered the uninhabited island on 11 July 1810, while looking for new sealing grounds. He claimed Macquarie Island for Britain and annexed it to the colony ofNew South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

in 1810. The island was named for Colonel Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; ; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie served as the fifth Gove ...

, Governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the representative of the monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia, Governor-General of Australia at the national level, the governor ...

from 1810 to 1821. Hasselborough reported a wreck "of ancient design", which has given rise to speculation that the island may have been visited before by Polynesians or others.Macquarie Island: a brief history — Australian Antarctic Division. Antarctica.gov.au. Retrieved on 16 July 2013. In the same year, Captain Smith described in more detail what is presumably the same wreck and incorrectly speculated that it belonged to French explorer

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse

Commodore (rank), Commodore Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse (; 23 August 1741 – ) was a French Navy officer and explorer. Having enlisted in the Navy at the age of 15, he had a successful career and in 1785 was appointed to lea ...

: "several pieces of wreck of a large vessel on this Island, apparently very old and high up in the grass, probably the remains of the ship of the unfortunate De la Perouse".

Between 1810 and 1919, seals and then penguins were hunted for their oil almost to the point of extinction. Sealers' relics include iron try pots, casks, hut ruins, graves and inscriptions. During that time, 144 vessel visits are recorded, 12 of which ended in shipwreck. The conditions on the island and the surrounding seas were considered so harsh that a plan to use it as a penal settlement was rejected.

Richard Siddins and his crew were shipwrecked in Hasselborough Bay on 11 June 1812. Joseph Underwood sent the ship ''Elizabeth and Mary'' to the island to rescue the remaining crew. The Russian explorer Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen explored the area for Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (, ; – ), nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He ruled Russian Empire, Russia during the chaotic perio ...

in 1820, and produced the first map of Macquarie Island. Bellingshausen landed on the island on 28 November 1820, defined its geographical position and traded his rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is often aged in barrels of oak. Rum originated in the Caribbean in the 17th century, but today it is produced i ...

and food for the island's fauna

Fauna (: faunae or faunas) is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding terms for plants and fungi are ''flora'' and '' funga'', respectively. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively ...

with the sealers.

In 1877, the crew of the schooner ''Bencleugh'' was shipwrecked on the island for four months; folklore says they came to believe there was hidden treasure on the island. The ship's owner, John Sen Inches Thomson, wrote a book on his sea travels, including his time on the island. The book, written in 1912, was entitled ''Voyages and Wanderings In Far-off Seas and Lands''.

Tasmania–New Zealand seal skin dispute

Macquarie Island was made a constituent part ofTasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

on 17 June 1880 through Letters Patent for the Governor of Tasmania.

In 1890, the Colony of New Zealand wrote to Lord Onslow (the Governor of New Zealand

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the type of political region or polity, a ''governor'' ma ...

), Philip Fysh (the Premier of Tasmania), and the Lord Knutsford (the Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

) regarding the island, initially requesting permission to annex the island, then requesting its transfer from the Colony of Tasmania, as this would close a loophole in New Zealand's closed sealing season when vessels were poaching on sub-Antarctic islands under the Colony's jurisdiction but claiming they got the seal skins from Macquarie Island. On the recommendation of Fysh, the Tasmanian Legislative Council

The Tasmanian Legislative Council is the upper house of the Parliament of Tasmania in Australia. It is one of the two Chambers of parliament, chambers of the Parliament, the other being the Tasmanian House of Assembly, House of Assembly. Both ho ...

passed a motion on 24 July 1890 requesting the "necessary steps be taken" for Macquarie Island to be transferred to New Zealand. Fysh was in no hurry to complete this process, and the request was only officially transmitted to the Tasmanian Legislative Assembly on 28 August 1890.

When the Legislative Assembly considered the matter on 2 September 1890, the virtue of transferring a dependent island was questioned, and (after several points of order and jokes from members) the assembly deferred consideration until the following day (effectively denying the transfer). By October 1890, it was certain that Tasmania would not condone the transfer of the island to New Zealand. Sir Harry Atkinson ( Premier of New Zealand) expressed his regrets that Tasmania had decided against the transfer, with Fysh noting that all of New Zealand's stated objectives could be achieved under existing Tasmanian legislation and through inter-colonial agreements. In mid October 1890, '' The Southland Times'' was reporting that an explanation was forthcoming from Wellington. On 23 October 1890, Fysh formally advised New Zealand of the colonial legislature's refusal to transfer the island, and on 20 November 1890 Knutsford formally advised Onslow that the British government had not consented to any transfer.

On 20 April 1891, regulations issued by the Tasmanian Commissioner of Fisheries for the protection of seals on Macquarie Island came into effect. This was possible under existing Tasmanian legislation, namely the Fisheries Act 1889. By 26 October 1891, these regulations were amended to expire on 20 July 1894, and to no longer include the forfeiture of a vessel as penalty for the offence.

20th century

Between 1902 and 1920, the Tasmanian Government leased the island to Joseph Hatch (1837–1928) for his oil industry based on harvesting penguins. Between 1911 and 1914, the island became a base for the Australasian Antarctic Expedition under SirDouglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) was a British-born Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Sir Ernest Shackleton, he was a key expedition leader during ...

. George Ainsworth operated a meteorological

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agriculture ...

station between 1911 and 1913, followed by Harold Power from 1913 to 1914, and by Arthur Tulloch from 1914 until the station was shut down in 1915.

In 1933, the authorities declared the island a wildlife sanctuary under the Tasmanian ''Animals and Birds Protection Act 1928'' and, in 1972, it was made a State Reserve under the Tasmanian ''National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970''.Parks & Wildlife Service - History of the Reserve. Parks.tas.gov.au (24 June 2013). Retrieved 16 July 2013. On 25 May 1948, the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) established its expedition headquarters on Macquarie Island. In March 1949, they were visited by the Fifth French Antarctic Expedition on their return trip from

Adélie Land

Adélie Land ( ) or Adélie Coast is a Territorial claims in Antarctica, claimed territory of France located on the continent of Antarctica. It stretches from a portion of the Southern Ocean coastline all the way inland to the South Pole. Franc ...

where any landing was made impossible due to extensive pack ice that year.

The island had status as a biosphere reserve under the Man and the Biosphere Programme

Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) is an intergovernmental scientific program, launched in 1971 by UNESCO, that aims to establish a scientific basis for the 'improvement of relationships' between people and their environments.

MAB engages w ...

from 1977 until its withdrawal from the program in 2011. On 5 December 1997, Macquarie Island was inscribed on the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage List

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural heritag ...

as a site of major geoconservation significance, being the only mid-ocean ridge on Earth where rocks from the Earth's mantle are being actively exposed above sea-level.

21st century

On 23 December 2004, an earthquake measuring 8.1 on themoment magnitude scale

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mwg, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. was defined in a 1979 paper ...

rocked the island but caused no significant damage. Geoscience Australia

Geoscience Australia is a statutory agency of the Government of Australia that carries out geoscientific research. The agency is the government's technical adviser on aspects of geoscience, and serves as the repository of geographic and geolo ...

issued a Tsunami Inundation Advice for Macquarie Island Station. The paper indicated that a tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

caused by a local earthquake could occur with no warning, and could inundate the isthmus and its existing station. Such a tsunami would likely affect other parts of the coastline and field huts located close to the shore. According to several papers, an earthquake capable of causing a tsunami of that significance is a high risk.

Geography

Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

. The Bishop and Clerk Islets mark the southernmost point of Australia (excluding the Australian Antarctic Territory).

In the 19th century a phantom island named " Emerald Island" was believed to lie south of Macquarie Island.

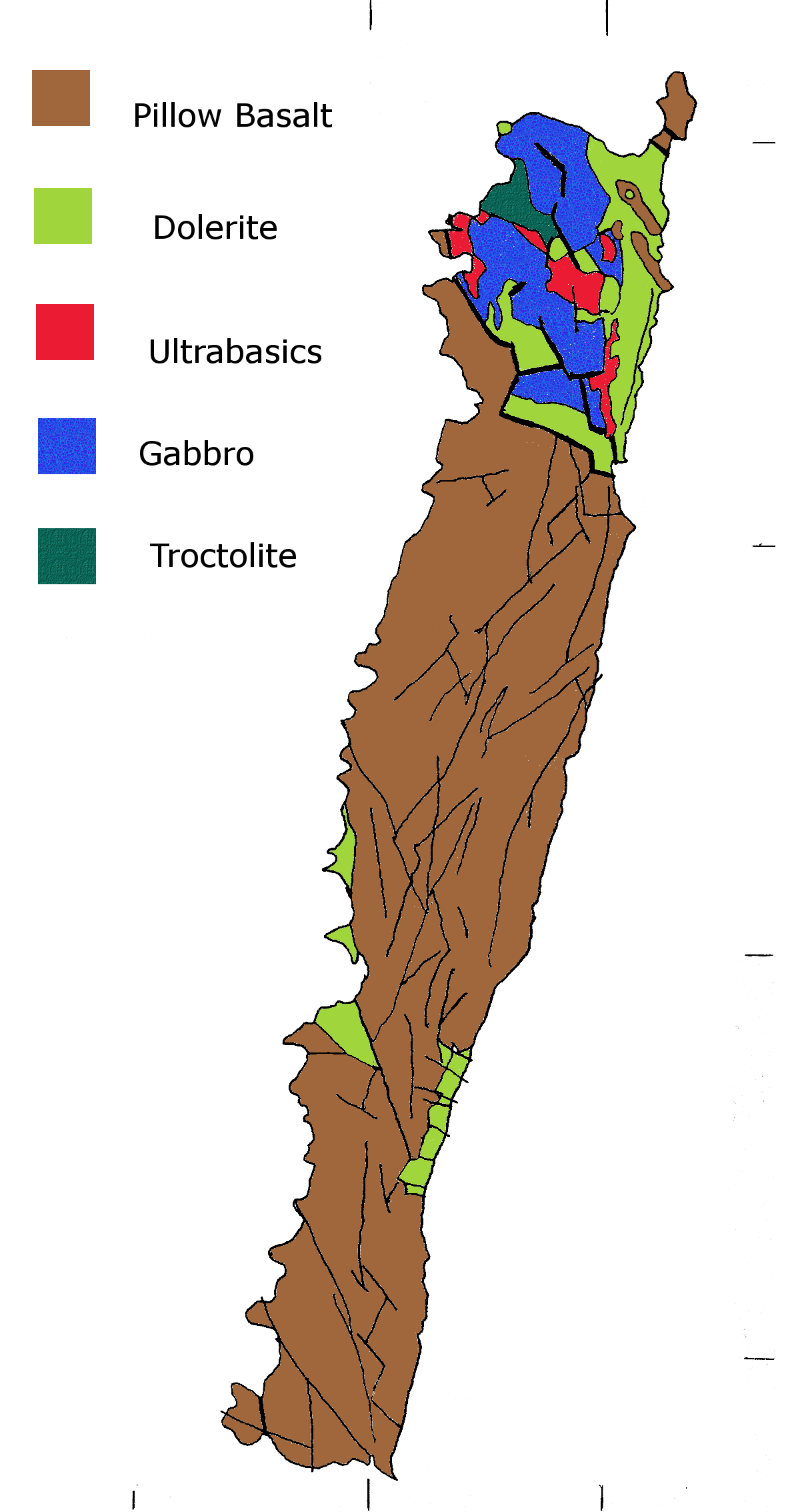

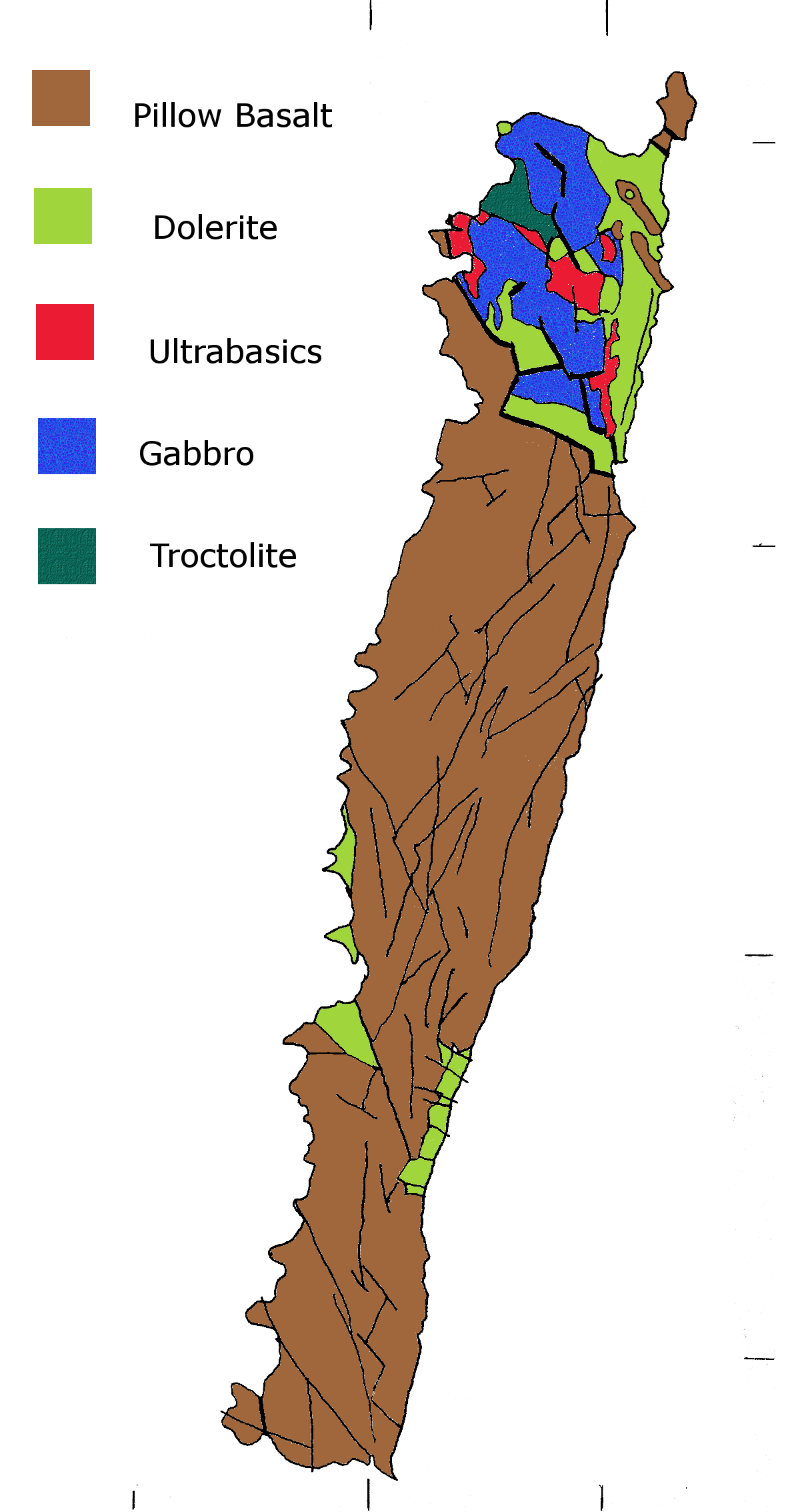

Geology

The island is located on thetectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

plate boundary between the Australian plate to the northwest and the Pacific plate to the southeast. It is part of the Macquarie Ridge, a long fault zone in the oceanic crust, running southwestwards from New Zealand along the plate boundary. The Macquarie Ridge has formed along the plate boundary by movement of the two plates towards each other, leading to uplift along the boundary. However, in earlier geologic time the two plates had been moving apart, allowing lava from the earth's mantle to rise to the seafloor, forming basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

. The subsequent reversal of the movement of the plates has uplifted the basaltic material from the seafloor along the line of the Macquarie Ridge.

The Macquarie ridge lies entirely on the seafloor except for where it rises above sea level at Macquarie Island. The island emerged above sea level in recent geologic time - the highest points on the island may have emerged above the sea as recently as 300,000 years ago or less. The estimates vary based on the assumed rate of uplift and the changes in sea level over time. The island is an example of an ophiolite

An ophiolite is a section of Earth's oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle that has been uplifted and exposed, and often emplaced onto continental crustal rocks.

The Greek word ὄφις, ''ophis'' (''snake'') is ...

- a section of Earth's oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

and the underlying upper mantle

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (geology), crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle (Earth), lower man ...

that has been uplifted and exposed. The process has been described as "the island itself seems to have been simply squeezed toward the surface like toothpaste from a tube". The unique exposures include excellent examples of pillow basalts without any hint of continental crust contamination and other extrusive rock

Extrusive rock refers to the mode of igneous volcanic rock formation in which hot magma from inside the Earth flows out (extrudes) onto the surface as lava or explodes violently into the atmosphere to fall back as pyroclastics or tuff. In cont ...

s. The geology of the island has been described as revealing "the best exposed and most isolated pieces of the ocean floor in the world". The unique geological exposures were one of the two criteria cited when the island was listed as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

in 1997.

The island lies close to the edge of the submerged continent of Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (Māori language, Māori) or Tasmantis (from Tasman Sea), is an almost entirely submerged continent, submerged mass of continental crust in Oceania that subsided after breaking away from Gondwana 83� ...

, but is not regarded as a part of it, because the Macquarie Ridge is oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

rather than continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as '' continental shelves''. This layer is sometimes called '' si ...

.

Climate

Macquarie Island's climate is moderated by the sea, and all months have an average temperature above freezing; although snow is common between June and October, and may even occur in summer. Due to its cold summers, the island has a tundra climate (''ET'') under theKöppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

.

Average daily maximum temperatures range from in July to in January. Precipitation occurs fairly evenly throughout the year and averages annually. Macquarie Island is one of the cloudiest places on Earth with an annual average of only 862 hours of sunshine (similar to Tórshavn

Tórshavn (; ; Danish language, Danish: ''Thorshavn''), usually locally referred to as simply Havn, is the capital and largest city of the Faroe Islands. It is located in the southern part on the east coast of Streymoy. To the northwest of th ...

in the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

). Annually, there are an average of 289.4 cloudy days and just 3.5 clear days.

There are 316.7 precipitation days annually, including 55.7 snowy days (being equal to Charlotte Pass on this metric). This is a considerably lower figure than at Heard Island due to its longitude, which receives 96.8 snowy days at only 53 degrees south.

Flora and fauna

vascular plant

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes (, ) or collectively tracheophyta (; ), are plants that have lignin, lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They also have a specialized non-lignified Ti ...

species and more than 90 moss species, as well as many liverworts

Liverworts are a group of non-vascular plant, non-vascular embryophyte, land plants forming the division Marchantiophyta (). They may also be referred to as hepatics. Like mosses and hornworts, they have a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, in wh ...

and lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

s. Woody plants are absent.

The island has five principal vegetation formations: grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominance (ecology), dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes such as clover, and other Herbaceo ...

, herbfield, fen, bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

and feldmark. Bog communities include 'featherbed', a deep and spongy peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

vegetated by grasses and low herbs, with patches of free water. Endemic flora include the cushion plant '' Azorella macquariensis'', the grass '' Puccinellia macquariensis'', and two orchids – '' Nematoceras dienemum'' and '' Nematoceras sulcatum''.

Mammals found on the island include subantarctic fur seals, Antarctic fur seals, New Zealand fur seals and southern elephant seals – over 80,000 individuals of this species. Diversities and distributions of cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s are less known; southern right whales and orcas are more common followed by other migratory baleen and toothed whales, especially sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

and beaked whales, which prefer deep waters. So-called "upland seals" once found on Antipodes Islands

The Antipodes Islands (, ) are inhospitable and uninhabited volcanic islands in subantarctic waters to the south of – and territorially part of – New Zealand. The archipelago lies to the southeast of Stewart Island / Rakiura, and to the ...

and Macquarie Island have been claimed by some researchers as a distinct subspecies of fur seals with thicker furs, although it is unclear whether these seals were genetically distinct.

Royal penguins and Macquarie shags are endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

breeders, while king penguins, southern rockhopper penguin

The western rockhopper penguin (''Eudyptes chrysocome''), traditionally known as the southern rockhopper penguin, is a species of rockhopper penguin that is sometimes considered distinct from the northern rockhopper penguin. It occurs in subanta ...

s and gentoo penguins also breed here in large numbers. The island has been identified by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

as an Important Bird Area because it supports about 3.5 million breeding seabirds of 13 species.

Human interaction

Protected area

The Tasmanian Government declared Macquarie Island as a wildlife sanctuary in 1933. The status was changed to a conservation area in 1971, and then in 1972 it was re-designated as a state reserve known as the Macquarie Island Wildlife Reserve. In 1977 the island was declared a Biosphere Reserve under theUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

Man and the Biosphere Programme

Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) is an intergovernmental scientific program, launched in 1971 by UNESCO, that aims to establish a scientific basis for the 'improvement of relationships' between people and their environments.

MAB engages w ...

, and it was also listed on the Australia Register of the National Estate

The Register of the National Estate was a heritage register that listed natural and cultural heritage places in Australia that was closed in 2007. Phasing out began in 2003, when the Australian National Heritage List and the Commonwealth Heri ...

. In 1978, the area of the state reserve was extended to the mean low-water mark including the offshore islets, and it was formally named as the Macquarie Island Nature Reserve. Access to the reserve was restricted from 1979 onwards, requiring a permit for all those seeking access to the reserve.

In December 1997, Macquarie Island was listed as UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

, including the reserve and the surrounding waters out to 12 nautical miles. The Macquarie Island Marine Park was established in 1999, and in 2000, the Macquarie Island Nature Reserve was extended in 2000 to include the area out to 3 nautical miles from the island and outlying islets.

Ecotourism

Ecotourism is a form of nature-oriented tourism intended to contribute to the Ecological conservation, conservation of the natural environment, generally defined as being minimally impactful, and including providing both contributions to conserv ...

cruise vessels visit the island, but the number of visitors has been limited to 2,000 per annum.

Impact of introduced animals

The island ecology was affected by the onset of European visits in 1810. The island'sfur seal

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family Otariidae. They are much more closely related to sea lions than Earless seal, true seals, and share with them external ears (Pinna (anatomy ...

s, elephant seals and penguin

Penguins are a group of aquatic flightless birds from the family Spheniscidae () of the order Sphenisciformes (). They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. Only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is equatorial, with a sm ...

s were killed for fur and blubber. Rats and mice that were inadvertently introduced from the ships prospered due to lack of predators. Cats were subsequently introduced deliberately to keep them from eating human food stores. In about 1870, rabbits and a species of New Zealand rail ( wekas) were left on the island by sealers to breed for food. This caused huge damage to the local wildlife, including the extinction of the Macquarie Island rail (''Gallirallus macquariensis''), the Macquarie parakeet (''Cyanoramphus erythrotis''), and an as-yet-undescribed species of teal. By the 1970s, 130,000 rabbits were causing tremendous damage to vegetation.

Feral cats

Theferal cat

A feral cat or a stray cat is an unowned domestic cat (''Felis catus'') that lives outdoors and avoids human contact; it does not allow itself to be handled or touched, and usually remains hidden from humans. Feral cats may breed over dozens ...

s introduced to the island had a devastating effect on the native seabird population, with an estimated annual loss of 60,000 seabirds. From 1985, efforts were undertaken to remove the cats. In June 2000, the last of the nearly 2,500 cats were culled in an effort to save the seabirds. Seabird populations responded rapidly, but rats and rabbit

Rabbits are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also includes the hares), which is in the order Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). They are familiar throughout the world as a small herbivore, a prey animal, a domesticated ...

s population increased after the cats were culled, and continued to cause widespread environmental damage.

Rabbits

The rabbits rapidly multiplied before numbers were reduced to about 10,000 in the early 1980s when myxomatosis was introduced. Rabbit numbers then grew again to over 100,000 by 2006. Rats and mice feeding on young chicks, and rabbits nibbling on the grass layer, has led to soil erosion and cliff collapses, destroying seabird nests. Large portions of the Macquarie Island bluffs are eroding as a result. In September 2006 a large landslip at Lusitania Bay, on the eastern side of the island, partially destroyed an important penguin breeding colony. Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service attributed the landslip to a combination of heavy spring rains and severe erosion caused by rabbits. Research by Australian Antarctic Division scientists, published in the 13 January 2009 issue of theBritish Ecological Society

The British Ecological Society is a learned society in the field of ecology that was founded in 1913. It is the oldest ecological society in the world. The Society's original objective was "to promote and foster the study of Ecology in its widest ...

's '' Journal of Applied Ecology'', suggested that the success of the feral cat eradication program has allowed the rabbit population to increase, damaging the Macquarie Island ecosystem by altering significant areas of island vegetation. However, in a comment published in the same journal other scientists argued that a number of factors (primarily a reduction in the use of the Myxoma virus) were almost certainly involved and the absence of cats may have been relatively minor among them. The original authors examined the issue in a later reply and concluded that the effect of the Myxoma virus use was small and reaffirmed their original position. The original authors did not, however, explain how rabbit numbers were greater in previous periods such as the 1970s before the myxoma virus was introduced and when cats were not being controlled, nor how rabbits had built up to such high numbers when cats were present for some 60 years prior to the introduction of rabbits; suggesting that cats were not controlling rabbit populations before the introduction of the myxoma virus.

Eradication of rabbits, rats and mice

On 4 June 2007, a media release by Malcolm Turnbull, Federal Minister for Australia's Environment and Water Resources Board, announced that the Australian and Tasmanian Governments had reached an agreement to jointly fund the eradication of rodent pests, including rabbits, to protect Macquarie Island's World Heritage values. The plan, estimated to cost $24 millionAustralian dollar

The Australian dollar (currency sign, sign: $; ISO 4217, code: AUD; also abbreviated A$ or sometimes AU$ to distinguish it from other dollar, dollar-denominated currencies; and also referred to as the dollar or Aussie dollar) is the official ...

s, was based on mass baiting the island similar to an eradication program on Campbell Island, New Zealand, to be followed with teams of dogs trained by Steve Austin over a maximum seven-year period. The baiting was expected to inadvertently affect kelp gulls, but greater-than-expected bird deaths caused the program to be suspended. Other species killed by the baits include giant petrels, black ducks and skuas.

In February 2012, ''The Australian

''The Australian'', with its Saturday edition ''The Weekend Australian'', is a broadsheet daily newspaper published by News Corp Australia since 14 July 1964. As the only Australian daily newspaper distributed nationally, its readership of b ...

'' newspaper reported that rabbits, rats and mice had been nearly eradicated from the island. In April 2012 the hunting teams reported the extermination of 13 rabbits that had survived the 2011 baiting; the last five were found in November 2011, including a lactating doe and four kittens. No fresh rabbit signs were found up to July 2013.

On 8 April 2014, Macquarie Island was officially declared pest-free, after seven years of conservation efforts. This achievement was the largest successful island pest-eradication program attempted to that date. In May 2024, it was reported that the island had remained free of pests for 10 years, with vegetation flourishing.

Populations of multiple bird species have begun to recover. The white-headed petrel (''Pterodroma lessonii'') that was close to extinction by 2001 has shown a large increase in breeding success, and the population is now slowly increasing. Two other species of petrel, the grey petrel (''Procellaria cinerea'') and blue petrel (''Halobaena caerulea'') that were extinct on the main island from the 1900s, have now returned. Their populations are increasing at around 10% per annum. However, ongoing monitoring, along with measures such as the use of biosecurity

Biosecurity refers to measures aimed at preventing the introduction or spread of harmful organisms (e.g. viruses, bacteria, plants, animals etc.) intentionally or unintentionally outside their native range or within new environments. In agricult ...

dogs to check cargo with the island as its destination are necessary, as there are new threats such as climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

and avian influenza. Ongoing monitoring programs are funded by the federal government.

Introduced birds

Despite being declared pest-free, Macquarie Island is still inhabited by several invasive bird species, such as the domestic mallard and European starling. The self-introduction of domestic mallards from New Zealand has become a threat to thePacific black duck

The Pacific black duck (''Anas superciliosa''), commonly known as the PBD, is a dabbling duck found in much of Indonesia, New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, and many islands in the southwestern Pacific, reaching to the Caroline Islands in the no ...

population on Macquarie Island through introgressive hybridisation.

Governance and administration

Macquarie Island has been a part of Tasmania, Australia since 1880. It was a part of Esperance Municipality until 1993, when the municipality was merged with other municipalities to form Huon Valley Council. Since 1948, the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) has maintained a permanent base, the Macquarie Island Station, on the isthmus at the northern end of the island at the foot of Wireless Hill. The population of the base, constituting the island's only human inhabitants, usually varies from 20 to 40 people over the year. A heliport is located nearby. In September 2016, the Australian Antarctic Division said it would close its research station on the island in 2017. However, shortly afterwards, theAustralian government

The Australian Government, also known as the Commonwealth Government or simply as the federal government, is the national executive government of Australia, a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The executive consists of the pr ...

responded to widespread backlash by announcing funding to upgrade ageing infrastructure and continue existing operations.

In 2018, the Australian Antarctic Division published a map showing the island's buildings with confirmed or suspected asbestos

Asbestos ( ) is a group of naturally occurring, Toxicity, toxic, carcinogenic and fibrous silicate minerals. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous Crystal habit, crystals, each fibre (particulate with length su ...

contamination, which included at least half the structures there.

In April 2024, Permanent Daylight-Saving Time on Macquarie Island was abolished by the Huon Valley Council and was changed to Summer DST. Previously, Macquarie Island was the only place on earth to observe permanent Daylight-Saving Time. Permanent Daylight-Saving on Macquarie Island was intended for stationed personnel on Macquarie Island Station, but then consent for a permanent human population was granted.

Through "Operation Southern Discovery", elements of the Australian Defence Force

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is the Armed forces, military organisation responsible for the defence of Australia and its national interests. It consists of three branches: the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Australian Army and the Royal Aus ...

also provide annual support for the Australian Antarctic Division and the Australian Antarctic Program (AAP) in regional scientific, environmental and economic activities. As part of "Operation Resolute", the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

and Australian Border Force

The Australian Border Force (ABF) is a federal law enforcement agency, part of the Department of Home Affairs (Australia), Department of Home Affairs, responsible for offshore and onshore border control, border enforcement, investigations, comp ...

are tasked with deploying or patrol boats to carry out civil maritime security operations in the region as may be required. In part to carry out this mission, as of 2023, the Navy's ''Armidale''-class boats are in the process of being replaced by larger s.

Gallery

flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

, '' Epilobium pedunculare''

File:MacquarieIsland5.JPG, Macquarie Island flora, '' Stilbocarpa polaris''

File:Royal penguins arguing.jpg, Royal penguins

File:MacquarieIslandElephantSeal.JPG, Bull elephant seals fighting

File:MacquarieIslandCormorant.JPG, Macquarie shag

File:MacquarieIslandGentoo.JPG, Gentoo penguin with chick

File:MacquarieIslandLusiBAY.JPG, King penguins at Lusitania Bay

File:MacquarieIslandRockhoppers.JPG, Eastern rockhopper penguins

File:MacquarieIslandSooties.JPG, Sooty albatross

File:MacquarieIslandIsthmus.JPG, Macquarie Island Station

File:MacquarieIslandWanderer.JPG, Wandering albatross

File:MacquarieIslandGreenGORGE.JPG, Green Gorge hut and king penguins

File:Pleurophyllum hookeri Macquarie Island.jpg, Highland herbfield dominated by '' Pleurophyllum hookeri''

Wildlife sounds

''Problems listening to the files? See Wikipedia media help.''See also

* ''Campbell Macquarie'' (1812 shipwreck) *Island restoration

The ecological restoration of islands, or island restoration, is the application of the principles of ecological restoration to islands and island groups. Islands, due to their isolation, are home to many of the world's endemic (ecology), endemic ...

* List of administrative heads of Macquarie Island

*List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

This is a list of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands.

* Antarctic islands are, in the strict sense, the islands around mainland Antarctica, situated on the Antarctic Plate, and south of the Antarctic Convergence. According to the terms of the A ...

* List of islands of Tasmania

* Macquarie Fault Zone

* Macquarie Island Marine Park

References

Sources

* * *Further reading

Macquarie Island, an 1882 paper in the ''Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand''

External links

Macquarie Island station

(Australian Antarctic Division)

Macquarie Island station webcam

{{Authority control

Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island is a subantarctic island in the south-western Pacific Ocean, about halfway between New Zealand and Antarctica. It has been governed as a part of Tasmania, Australia, since 1880. It became a Protected areas of Tasmania, Tasmania ...

Australian National Heritage List

Important Bird Areas of Tasmania

Island restoration

Islands of Tasmania

Protected areas of Tasmania

World Heritage Sites in Australia

IBRA subregions

Islands of the Pacific Ocean

Former biosphere reserves

Seal hunting

Important Bird Areas of subantarctic islands