Mortimer Wheeler on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British

When Wheeler was four, his father was appointed chief

When Wheeler was four, his father was appointed chief

Upon the retirement of the Keeper of the London Museum, Harmon Oates, Wheeler was invited to fill the vacancy. He had been considering a return to London for some time and eagerly agreed, taking on the post, which was based at

Upon the retirement of the Keeper of the London Museum, Harmon Oates, Wheeler was invited to fill the vacancy. He had been considering a return to London for some time and eagerly agreed, taking on the post, which was based at  Wheeler was keen to continue archaeological fieldwork outside London, undertaking excavations every year from 1926 to 1939. After completing his excavation of the Carlaeon amphitheatre in 1928, he began fieldwork at the Roman settlement and temple in Lydney Park,

Wheeler was keen to continue archaeological fieldwork outside London, undertaking excavations every year from 1926 to 1939. After completing his excavation of the Carlaeon amphitheatre in 1928, he began fieldwork at the Roman settlement and temple in Lydney Park,

Serving with the Eighth Army, Wheeler was present in North Africa when the Axis armies pushed the Allies back to El Alamein. He was also part of the Allied counter-push, taking part in the

Serving with the Eighth Army, Wheeler was present in North Africa when the Axis armies pushed the Allies back to El Alamein. He was also part of the Allied counter-push, taking part in the

Wheeler arrived in Bombay in the spring of 1944. There, he was welcomed by the city's governor, John Colville, before heading by train to

Wheeler arrived in Bombay in the spring of 1944. There, he was welcomed by the city's governor, John Colville, before heading by train to  Wheeler established a new archaeological journal, ''

Wheeler established a new archaeological journal, ''

From 1954 onward, Wheeler began to devote an increasing amount of his time to encouraging greater public interest in archaeology, and it was in that year that he obtained an agent. Oxford University Press also published two of his books in 1954. The first was a book on archaeological methodologies, ''Archaeology from the Earth'', which was translated into various languages. The second was ''Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontier'', discussing evidence for Roman activity at sites such as Arikamedu and Segontium. In 1955 Wheeler released his episodic autobiography, ''Still Digging'', which had sold over 70,000 copies by the end of the year. In 1959, Wheeler wrote ''Early India and Pakistan'', which was published as part as Daniel's "Ancient Peoples and Places" series for Thames and Hudson; as with many earlier books, he was criticised for rushing to conclusions.

He wrote the section entitled "Ancient India" for Piggott's edited volume ''The Dawn of Civilisation'', which was published by Thames and Hudson in 1961, before writing an introduction for Roger Wood's photography book ''Roman Africa in Colour'', which was also published by Thames and Hudson. He then agreed to edit a series for the publisher, known as "New Aspects of Antiquity", through which they released a variety of archaeological works. The rival publisher

From 1954 onward, Wheeler began to devote an increasing amount of his time to encouraging greater public interest in archaeology, and it was in that year that he obtained an agent. Oxford University Press also published two of his books in 1954. The first was a book on archaeological methodologies, ''Archaeology from the Earth'', which was translated into various languages. The second was ''Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontier'', discussing evidence for Roman activity at sites such as Arikamedu and Segontium. In 1955 Wheeler released his episodic autobiography, ''Still Digging'', which had sold over 70,000 copies by the end of the year. In 1959, Wheeler wrote ''Early India and Pakistan'', which was published as part as Daniel's "Ancient Peoples and Places" series for Thames and Hudson; as with many earlier books, he was criticised for rushing to conclusions.

He wrote the section entitled "Ancient India" for Piggott's edited volume ''The Dawn of Civilisation'', which was published by Thames and Hudson in 1961, before writing an introduction for Roger Wood's photography book ''Roman Africa in Colour'', which was also published by Thames and Hudson. He then agreed to edit a series for the publisher, known as "New Aspects of Antiquity", through which they released a variety of archaeological works. The rival publisher

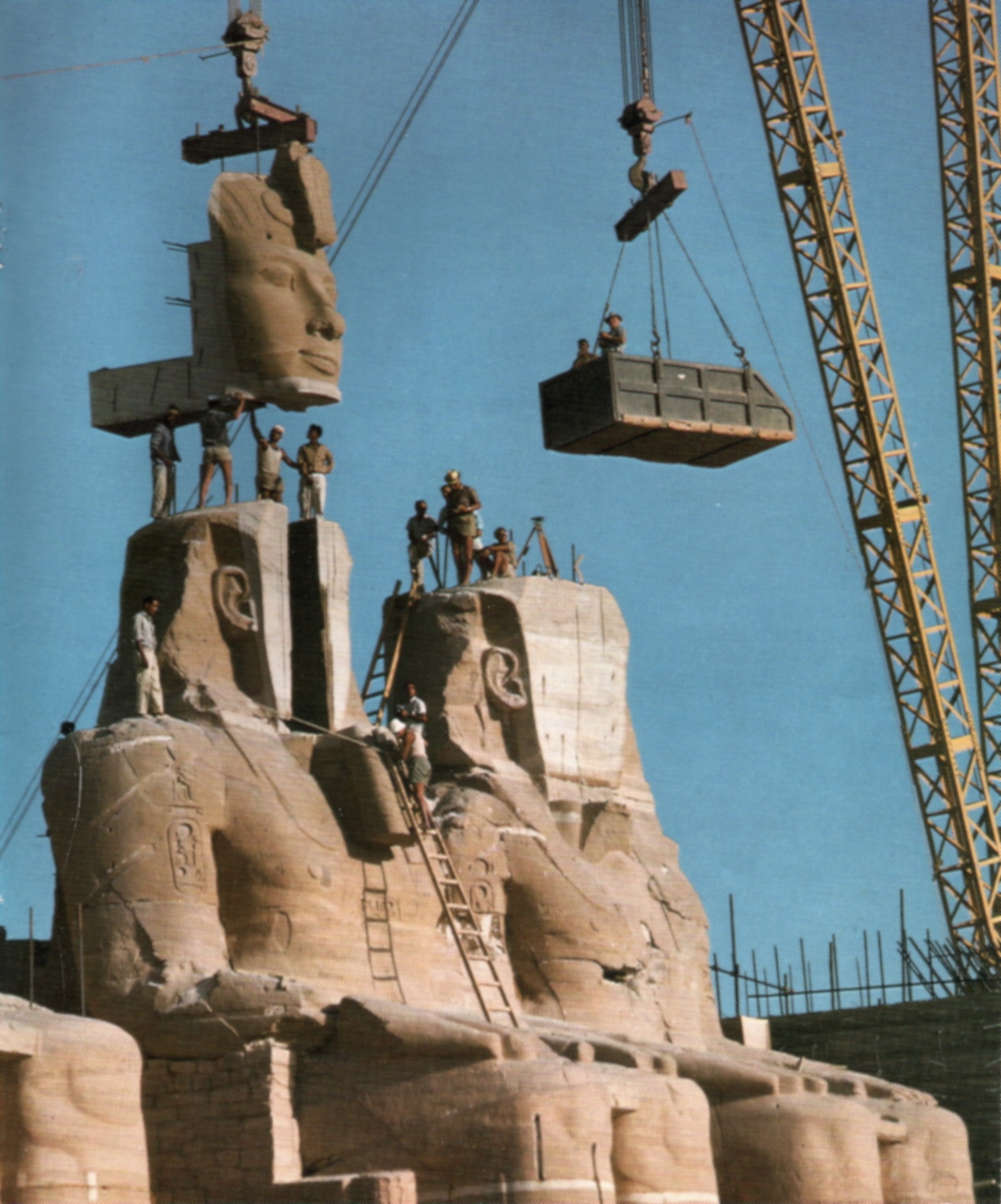

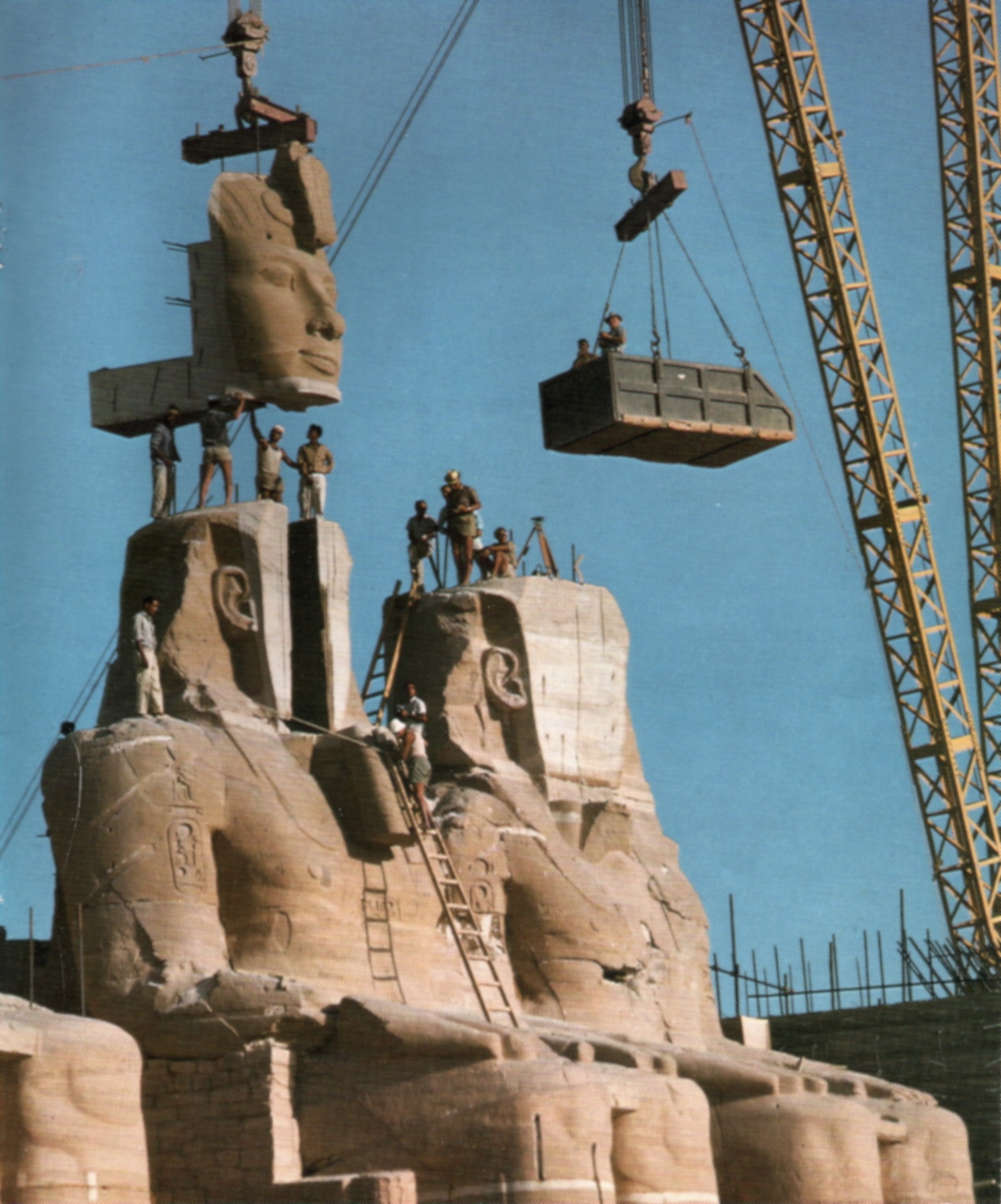

As Honorary Secretary of the British Academy, Wheeler focused on increasing the organisation's revenues, thus enabling it to expand its remit. He developed personal relationships with various employees at the British Treasury, and offered the academy's services as an intermediary in dealing with the Egypt Exploration Society, the

As Honorary Secretary of the British Academy, Wheeler focused on increasing the organisation's revenues, thus enabling it to expand its remit. He developed personal relationships with various employees at the British Treasury, and offered the academy's services as an intermediary in dealing with the Egypt Exploration Society, the

Wheeler was known as "Rik" among friends. He divided opinion among those who knew him, with some loving and others despising him, and during his lifetime, he was often criticised on both scholarly and moral grounds.

Archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan asserted that he "was a delightful, light-hearted and amusing companion, but those close to him knew that he could be a dangerous opponent if threatened with frustration".

His

Wheeler was known as "Rik" among friends. He divided opinion among those who knew him, with some loving and others despising him, and during his lifetime, he was often criticised on both scholarly and moral grounds.

Archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan asserted that he "was a delightful, light-hearted and amusing companion, but those close to him knew that he could be a dangerous opponent if threatened with frustration".

His

accessed 11 March 2013

"Sir Mortimer and Magnus" interview

on BBC iPlayer

Dictionary of Art Historians

Mortimer Wheeler

– National Portrait Gallery {{DEFAULTSORT:Wheeler, Mortimer 1890 births 1976 deaths Archaeologists from Glasgow 20th-century Scottish antiquarians Royal Artillery officers Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Companions of the Order of the Indian Empire Recipients of the Military Cross British Army personnel of World War I British Army brigadiers of World War II Military personnel from Glasgow Knights Bachelor Academics of the UCL Institute of Archaeology Archaeologists of the Indus Valley civilisation Fellows of the British Academy Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of London Presidents of the Society of Antiquaries of London Members of the Cambrian Archaeological Association British television presenters People educated at Bradford Grammar School Alumni of the University of London Directors general of the Archaeological Survey of India People associated with Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales British expatriates in Pakistan Archaeologists of South Asia Indian institute directors BAFTA winners (people) 20th-century British archaeologists Presidents of the Royal Archaeological Institute Mohenjo-daro Harappa

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

and officer in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

and London Museum, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexander ...

, and the founder and Honorary Director of the Institute of Archaeology in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, in addition to writing twenty-four books on archaeological subjects.

Born in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

to a middle-class family, Wheeler was raised largely in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

before moving to London in his teenage years. After studying classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

(UCL), he began working professionally in archaeology, specialising in the Romano-British

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, ...

period. During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

he volunteered for service in the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

, being stationed on the Western Front, where he rose to the rank of major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

and was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

. Returning to Britain, he obtained his doctorate from UCL before taking on a position at the National Museum of Wales, first as Keeper of Archaeology and then as Director, during which time he oversaw excavation at the Roman forts of Segontium, Y Gaer, and Isca Augusta

Isca, variously specified as Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum, was the site of a Roman legionary fortress and settlement or ''vicus'', the remains of which lie beneath parts of the present-day suburban town of Caerleon in the north of the city of ...

with the aid of his first wife, Tessa Wheeler. Influenced by the archaeologist Augustus Pitt Rivers, Wheeler argued that excavation and the recording of stratigraphic context required an increasingly scientific and methodical approach, developing the " Wheeler method". In 1926, he was appointed Keeper of the London Museum; there, he oversaw a reorganisation of the collection, successfully lobbied for increased funding, and began lecturing at UCL.

In 1934, he established the Institute of Archaeology as part of the federal University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

, adopting the position of Honorary Director. In this period, he oversaw excavations of the Roman sites at Lydney Park and Verulamium and the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

hill fort

A hillfort is a type of fortification, fortified refuge or defended settlement located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typical of the late Bronze Age Europe, European Bronze Age and Iron Age Europe, Iron Age. So ...

of Maiden Castle. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he re-joined the Armed Forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a ...

and rose to the rank of brigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

, serving in the North African Campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

and then the Allied invasion of Italy

The Allied invasion of Italy was the Allies of World War II, Allied Amphibious warfare, amphibious landing on mainland Italy that took place from 3 September 1943, during the Italian campaign (World War II), Italian campaign of World War II. T ...

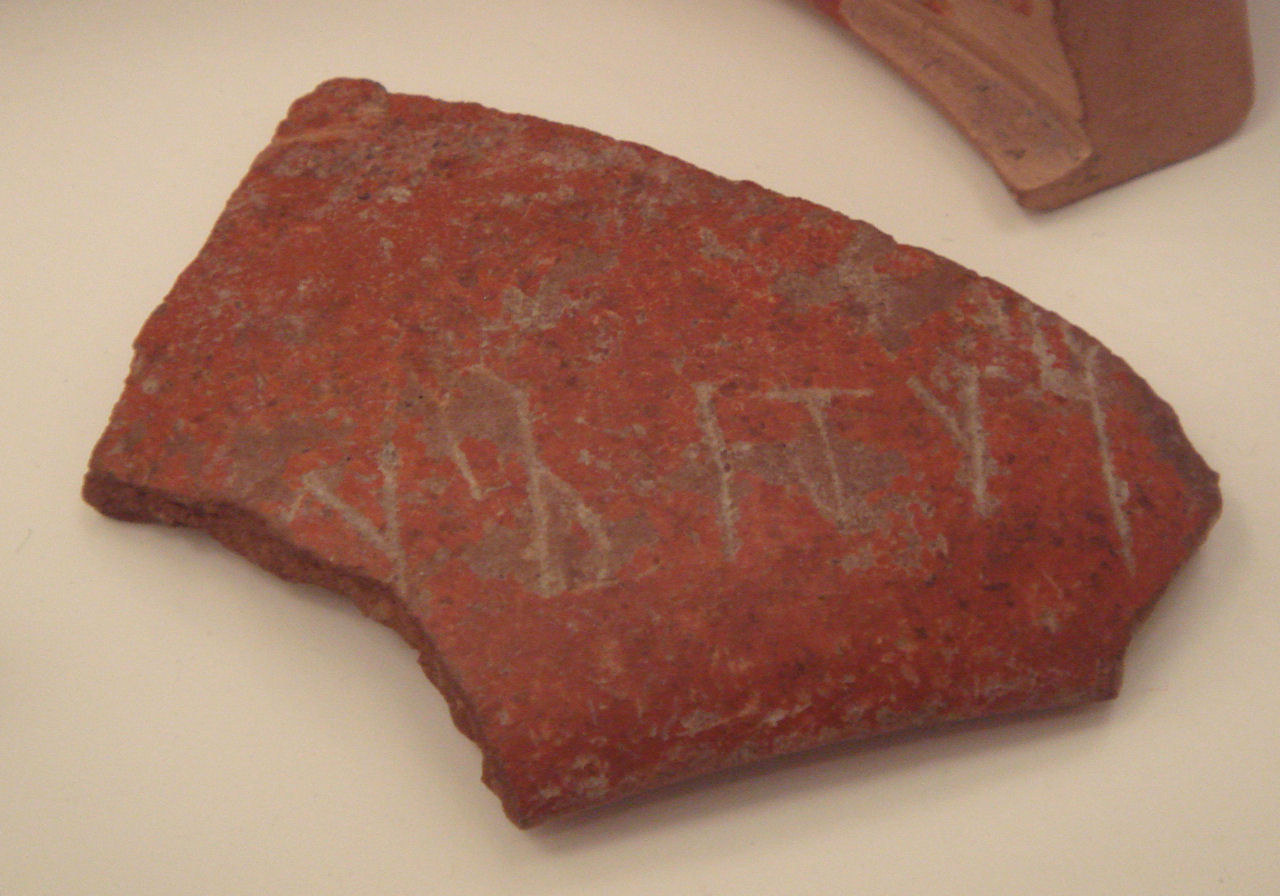

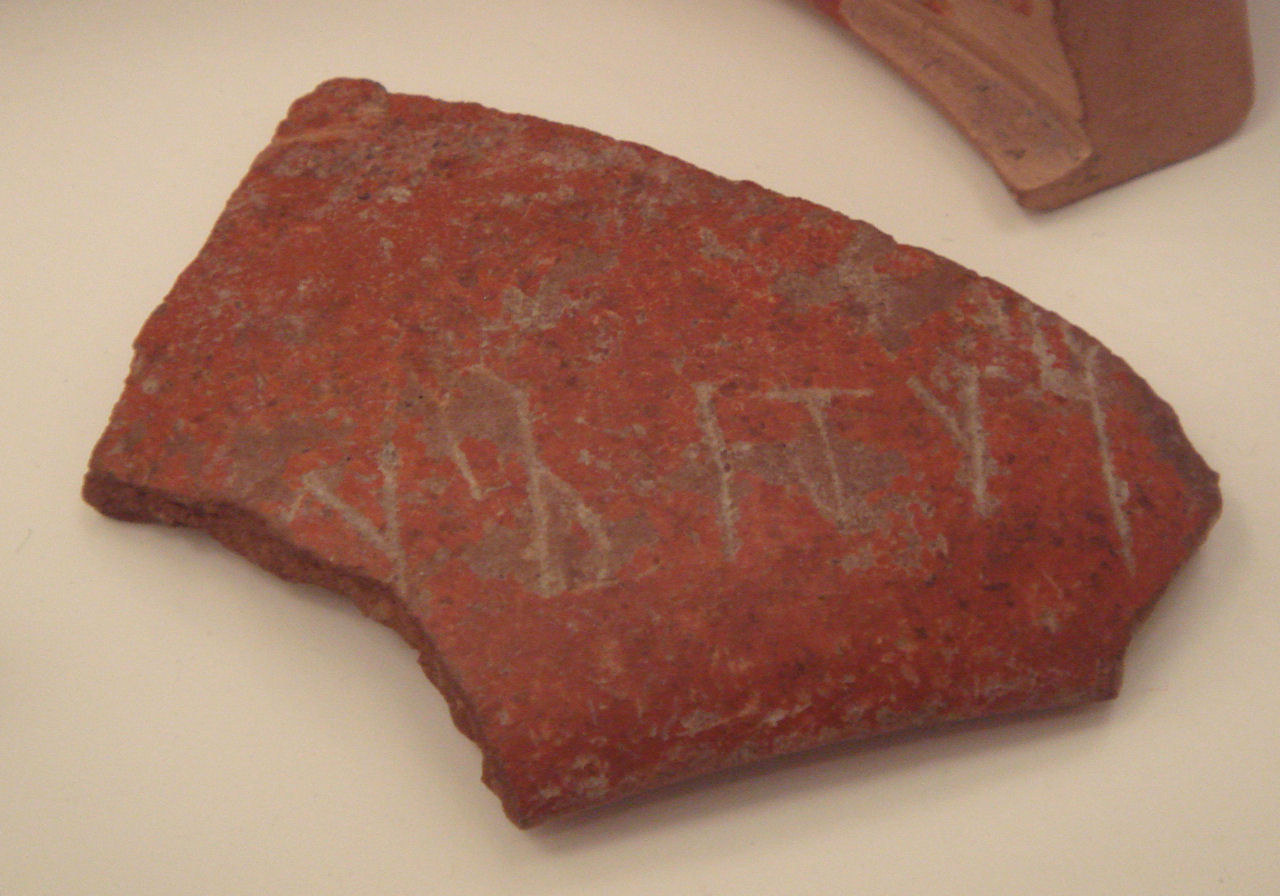

. In 1944 he was appointed Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, through which he oversaw excavations of sites at Harappa

Harappa () is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal, that takes its name from a modern village near the former course of the Ravi River, which now runs to the north. Harappa is the type site of the Bronze Age Indus ...

, Arikamedu, and Brahmagiri, and implemented reforms to the subcontinent's archaeological establishment. Returning to Britain in 1948, he divided his time between lecturing for the Institute of Archaeology and acting as archaeological adviser to Pakistan's government. In later life, his popular books, cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports of call, where passengers may go on Tourism, tours k ...

lectures, and appearances on radio and television, particularly the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

series '' Animal, Vegetable, Mineral?'', helped to bring archaeology to a mass audience. Appointed Honorary Secretary of the British Academy

The British Academy for the Promotion of Historical, Philosophical and Philological Studies is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the sa ...

, he raised large sums of money for archaeological projects, and was appointed British representative for several UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

projects.

Wheeler is recognised as one of the most important British archaeologists of the 20th century, responsible for successfully encouraging British public interest in the discipline and advancing methodologies of excavation and recording. Furthermore, he is widely acclaimed as a major figure in the establishment of South Asian archaeology. However, many of his specific interpretations of archaeological sites have been discredited or reinterpreted.

Early life

Childhood: 1890–1907

Mortimer Wheeler was born on 10 September 1890 in the city ofGlasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, Scotland. He was the first child of the journalist Robert Mortimer Wheeler and his second wife Emily Wheeler ( Baynes).

The son of a tea merchant based in Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, in youth Robert had considered becoming a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister, but instead became a staunch freethinker while studying at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

. Initially working as a lecturer in English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

, Robert turned to journalism after his first wife died in childbirth. His second wife, Emily, shared her husband's interest in English literature, and was the niece of Thomas Spencer Baynes, a Shakespearean scholar at St. Andrews University. Their marriage was emotionally strained, a situation exacerbated by their financial insecurity. Within two years of their son's birth, the family moved to Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, where a daughter named Amy was born.

When Wheeler was four, his father was appointed chief

When Wheeler was four, his father was appointed chief leader

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

writer for the '' Bradford Observer''. The family relocated to Saltaire

Saltaire is a Victorian model village near Shipley, West Yorkshire, England, situated between the River Aire, the railway, and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Salts Mill and the houses were built by Titus Salt between 1851 and 1871 to allo ...

, a village northwest of Bradford

Bradford is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in West Yorkshire, England. It became a municipal borough in 1847, received a city charter in 1897 and, since the Local Government Act 1972, 1974 reform, the city status in the United Kingdo ...

, a cosmopolitan city in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

, northeast England, then in the midst of the wool trade boom. Wheeler was inspired by the moors surrounding Saltaire and fascinated by the area's archaeology. He later wrote about discovering a late prehistoric cup-marked stone, searching for lithics

Lithic may refer to:

*Relating to stone tools

** Lithic analysis, the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts

** Lithic core, the part of a stone which has had flakes removed from it

** Lithic flake, the portion of a rock removed ...

on Ilkley Moor

Ilkley Moor is part of Rombalds Moor, the moorland between Ilkley and Keighley in West Yorkshire, England. The moor, which rises to 402 m (1,319 ft) above sea level, is the inspiration for the Yorkshire "county anthem" ''On Ilkla Mo ...

, and digging into a barrow on Baildon Moor. Although in ill health, Emily Wheeler taught her two children with the help of a maid

A maid, housemaid, or maidservant is a female domestic worker. In the Victorian era, domestic service was the second-largest category of employment in England and Wales, after agricultural work. In developed Western nations, full-time maids a ...

up to the age of seven or eight. Mortimer remained emotionally distant from his mother, instead being far closer to his father, whose company he favoured over that of other children.

His father had a keen interest in natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

and a love of fishing and shooting, rural pursuits in which he encouraged Mortimer to take part. Robert acquired many books for his son, particularly on the subject of art history

Art history is the study of Work of art, artistic works made throughout human history. Among other topics, it studies art’s formal qualities, its impact on societies and cultures, and how artistic styles have changed throughout history.

Tradit ...

, with Wheeler loving to both read and paint.

In 1899, Wheeler joined Bradford Grammar School shortly before his ninth birthday, where he proceeded straight to the second form. In 1902, Robert and Emily had a second daughter, whom they named Betty; Mortimer showed little interest in this younger sister. In 1905, Robert agreed to take over as head of the London office of his newspaper, by then renamed the ''Yorkshire Daily Observer'', so the family relocated to the southeast of the city in December 1905, settling into a house named Carlton Lodge on South Croydon Road, West Dulwich

West Dulwich ( ) is a neighbourhood in South London on the southern boundary of Brockwell Park, which straddles the London Borough of Lambeth and the London Borough of Southwark. Croxted Road and South Croxted Road mark the boundary between Sou ...

. In 1908, they moved to 14 Rollescourt Avenue in nearby Herne Hill

Herne Hill () is a district in South London, approximately four miles from Charing Cross and bordered by Brixton, Camberwell, Dulwich, and Tulse Hill. It sits to the north and east of Brockwell Park and straddles the boundary between the London ...

. Rather than being sent for a conventional education, when he was 15 Wheeler was instructed to educate himself by spending time in London, where he frequented the National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of more than 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current di ...

and the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

.

University and early career: 1907–14

After passing the entrance exam on his second attempt, in 1907 Wheeler was awarded a scholarship to readclassical studies

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and their original languages ...

at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

(UCL), commuting daily from his parental home to the university campus in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

, central London. At UCL, he was taught by the prominent classicist A. E. Housman. During his undergraduate studies, he became editor of the ''Union Magazine'', for which he produced a number of illustrated cartoons. Increasingly interested in art, he decided to switch from classical studies to a course at UCL's art school

An art school is an educational institution with a primary focus on practice and related theory in the visual arts and design. This includes fine art – especially illustration, painting, contemporary art, sculpture, and graphic design. T ...

, the Slade School of Fine Art

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

; he returned to his previous subject after coming to the opinion that – in his words – he never became more than "a conventionally accomplished picture maker". This interlude had adversely affected his classical studies, and he received a second class BA on graduating.

Wheeler began studying for a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

degree in classical studies, which he attained in 1912. During this period, he also gained employment as the personal secretary of the UCL Provost Gregory Foster, although he later criticised Foster for transforming the university from "a college in the truly academic sense ntoa hypertrophied monstrosity as little like a college as a plesiosaurus is like a man". It was also at this time of life that he met and began a relationship with Tessa Verney, a student then studying history at UCL, when they were both serving on the committee of the University College Literary Society.

During his studies, Wheeler had developed his love of archaeology, having joined an excavation of Viroconium Cornoviorum, a Romano-British

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, ...

settlement in Wroxeter, in 1913. Considering a profession in the discipline, he won a studentship that had been established jointly by the University of London and the Society of Antiquaries in memory of Augustus Wollaston Franks. The prominent archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans doubled the amount of money that went with the studentship. Wheeler's proposed project had been to analyse Romano-Rhenish pottery, and with the grant he funded a trip to the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

in Germany, there studying the Roman pottery housed in local museums; his research into this subject was never published.

At this period, there were very few jobs available within British archaeology; as the later archaeologist Stuart Piggott

Stuart Ernest Piggott, (28 May 1910 – 23 September 1996) was a British archaeologist, best known for his work on prehistoric Wessex.

Early life

Piggott was born in Petersfield, Hampshire, the son of G. H. O. Piggott, and was educated ...

related, "the young Wheeler was looking for a professional job where the profession had yet to be created." In 1913 Wheeler secured a position as junior investigator for the English Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, who were embarking on a project to assess the state of all structures in the nation that pre-dated 1714. As part of this, he was first sent to Stebbing in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

to assess Late Medieval buildings, although once that was accomplished he focused on studying the Romano-British remains of that county. In summer 1914, he married Tessa in a low-key, secular wedding ceremony, before they moved into Wheeler's parental home in Herne Hill.

First World War: 1914–18

After the United Kingdom's entry intoWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914, Wheeler volunteered for the armed forces. Although preferring solitary to group activities, Wheeler found that he greatly enjoyed soldiering, and on 9 November 1914 was commissioned a temporary second lieutenant in the University of London Officer Training Corps, serving with its artillery unit as an instructor. It was during this period, in January 1915, that a son was born to the Wheelers, and named Michael. Michael Wheeler was their only child, something that was a social anomaly at the time, although it is unknown whether or not this was by choice. In May 1915, Wheeler transferred to the 1st Lowland Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery

The Royal Field Artillery (RFA) of the British Army provided close artillery support for the infantry. It was created as a distinct arm of the Royal Regiment of Artillery on 1 July 1899, serving alongside the other two arms of the regiment, the ...

(Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry in ...

), and was confirmed in his rank on 1 July, with a promotion to temporary lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

from the same date. Shortly thereafter, on 16 July, Wheeler was promoted to temporary captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. In this position he was stationed at various bases across Britain, often bringing his wife and child with him; his responsibility was as a battery commander, initially of field guns and later of howitzer

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

s.

In October 1917 Wheeler was posted to the 76th Army Field Artillery Brigade, one of the Royal Field Artillery

The Royal Field Artillery (RFA) of the British Army provided close artillery support for the infantry. It was created as a distinct arm of the Royal Regiment of Artillery on 1 July 1899, serving alongside the other two arms of the regiment, the ...

brigades under the direct control of the General Officer Commanding

General officer commanding (GOC) is the usual title given in the armies of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth (and some other nations, such as Ireland) to a general officer who holds a command appointment.

Thus, a general might be the GOC ...

, Third Army. The brigade was then stationed in Belgium, where it had been engaged in the Battle of Passchendaele against German troops along the Western Front. By now a substantive lieutenant (temporary captain), on 7 October he was appointed second-in-command of an artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to f ...

with the acting rank of captain, but on 21 October became commander of a battery with the acting rank of major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

, replacing a major who had been poisoned by mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard are names commonly used for the organosulfur compound, organosulfur chemical compound bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, which has the chemical structure S(CH2CH2Cl)2, as well as other Chemical species, species. In the wi ...

. He was part of the Left Group of artillery covering the advancing Allied infantry in the battle. Throughout, he maintained correspondences with his wife, his sister Amy, and his parents. After the Allied victory in the battle, the brigade was transferred to Italy.

Wheeler and the brigade arrived in Italy on 20 November, and proceeded through the Italian Riviera

The Italian Riviera or Ligurian Riviera ( ; ) is the narrow coastal strip in Italy which lies between the Ligurian Sea and the mountain chain formed by the Maritime Alps and the Apennines. Longitudinally it extends from the border with F ...

to reach Caporetto, where it had been sent to bolster the Italian troops against a German and Austro-Hungarian advance. As the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federative Republic in the 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territory of the former Russian Empire after its proclamation by the Rus ...

removed itself from the war, the German Army refocused its efforts on the Western Front, so in March 1918 Wheeler's brigade was ordered to leave Italy, getting a train from Castelfranco to Vieux Rouen in France. Back on the Western Front, the brigade was assigned to the 2nd Division, again part of Julian Byng's Third Army, reaching a stable area of the front in April. Here, Wheeler was engaged in artillery fire for several months, before the British went on the offensive in August. On 24 August, between the ruined villages of Achiet and Sapignies, he led an expedition that captured two German field guns while under heavy fire from a castle mound; he was later awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

for this action:

Wheeler continued as part of the British forces pushing westward until the German surrender in November 1918, receiving a mention in dispatches on 8 November. He was not demobilised for several months, instead being stationed at Pulheim in Germany until March; during this time he wrote up his earlier research on Romano-Rhenish pottery, making use of access to local museums, before returning to London in July 1919. Reverting to his permanent rank of lieutenant on 16 September, Wheeler was finally discharged from service on 30 September 1921, retaining the rank of major.

Career

National Museum of Wales: 1919–26

On returning to London, Wheeler moved into a top-floor flat nearGordon Square

Gordon Square is a public park square in Bloomsbury, London, England. It is part of the Bedford Estate and was designed as one of a pair with the nearby Tavistock Square. It is owned by the University of London.

History and buildings

The sq ...

with his wife and child. He returned to working for the Royal Commission, examining and cataloguing the historic structures of Essex. In doing so, he produced his first publication, an academic paper

Academic publishing is the subfield of publishing which distributes Research, academic research and scholarship. Most academic work is published in academic journal articles, books or Thesis, theses. The part of academic written output that is n ...

on Colchester's Roman Balkerne Gate which was published in the ''Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society'' in 1920. He soon followed this with two papers in the ''Journal of Roman Studies

The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies (The Roman Society) was founded in 1910 as the sister society to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies.

The Society is the leading organisation in the United Kingdom for those interest ...

''; the first offered a wider analysis of Roman Colchester, while the latter outlined his discovery of the vaulting for the city's Temple of Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; ; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54), or Claudius, was a Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusus and Ant ...

which was destroyed by Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (, from Brittonic languages, Brythonic * 'victory, win' + * 'having' suffix, i.e. 'Victorious Woman', known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh language, Welsh as , ) was a queen of the Iceni, ancient ...

's revolt. In doing so, he developed a reputation as a Roman archaeologist in Britain. He then submitted his research on Romano-Rhenish pots to the University of London, on the basis of which he was awarded his Doctorate of Letters; thenceforth until his knighthood he styled himself as Dr Wheeler. He was unsatisfied with his job in the commission, unhappy that he was receiving less pay and a lower status than he had had in the army, so began to seek alternative employment.

He obtained a post as the Keeper of Archaeology at the National Museum of Wales

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

, a job that also entailed becoming a lecturer in archaeology at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire. Taking up this position, he moved to Cardiff

Cardiff (; ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. Cardiff had a population of in and forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area officially known as the City and County of Ca ...

with his family in August 1920, although he initially disliked the city. The museum was in disarray; before the war, construction had begun on a new purpose-built building to house the collections. This had ceased during the conflict and the edifice was left abandoned during Cardiff's post-war economic slump. Wheeler recognised that Wales was very divided regionally, with many Welsh people having little loyalty to Cardiff; thus, he made a point of touring the country, lecturing to local societies about archaeology. According to the later archaeologist Lydia C. Carr, the Wheelers' work for the cause of the museum was part of a wider "cultural-nationalist movement" linked to growing Welsh nationalism during this period; for instance, the Welsh nationalist party Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; , ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, and often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left, Welsh nationalist list of political parties in Wales, political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from th ...

was founded in 1925.

Wheeler was impatient to start excavations, and in July 1921 started a six-week project to excavate at the Roman fort of Segontium; accompanied by his wife, he used up his holiday to oversee the project. A second season of excavation at the site followed in 1922. Greatly influenced by the writings of the archaeologist Augustus Pitt-Rivers, Wheeler emphasised the need for a strong, developed methodology when undertaking an archaeological excavation, believing in the need for strategic planning, or what he termed "controlled discovery", with clear objectives in mind for a project. Further emphasising the importance of prompt publication of research results, he wrote full seasonal reports for ''Archaeologia Cambrensis

''Archaeologia Cambrensis'' is a Welsh archaeological and historical scholarly journal published annually by the Cambrian Archaeological Association. It contains historical essays, excavation reports, and book reviews, as well as society notes ...

'' before publishing a full report, ''Segontium and the Roman Occupation of Wales''. Wheeler was keen on training new generations of archaeologists, and two of the most prominent students to excavate with him at Segontium were Victor Nash-Williams and Ian Richmond.

Over the field seasons of 1924 and 1925, Wheeler ran excavations of the Roman fort of Y Gaer near Brecon

Brecon (; ; ), archaically known as Brecknock, is a market town in Powys, mid Wales. In 1841, it had a population of 5,701. The population in 2001 was 7,901, increasing to 8,250 at the 2011 census. Historically it was the county town of Breck ...

, a project aided by his wife and two archaeological students, Nowell Myres and Christopher Hawkes. During this project, he was visited by the prominent Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie and his wife Hilda Petrie; Wheeler greatly admired Petrie's emphasis on strong archaeological methodologies. Wheeler published the results of his excavation in ''The Roman Fort Near Brecon''. He then began excavations at Isca Augusta

Isca, variously specified as Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum, was the site of a Roman legionary fortress and settlement or ''vicus'', the remains of which lie beneath parts of the present-day suburban town of Caerleon in the north of the city of ...

, a Roman site in Caerleon

Caerleon ( ; ) is a town and Community (Wales), community in Newport, Wales. Situated on the River Usk, it lies northeast of Newport city centre, and southeast of Cwmbran. Caerleon is of archaeological importance, being the site of a notable ...

, where he focused on revealing the Roman amphitheatre. Intent on attracting press attention to both raise public awareness of archaeology and attract new sources of funding, he contacted the press and organised a sponsorship of the excavation by the middle-market newspaper the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

''. In doing so, he emphasised the folkloric and legendary associations that the site had with King Arthur

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Great Britain, Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Wales, Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a le ...

. In 1925, Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

published Wheeler's first book for a general audience, ''Prehistoric and Roman Wales''; he later expressed the opinion that it was not a good book.

In 1924, the Director of the National Museum of Wales, William Evans Hoyle, resigned amid ill health. Wheeler applied to take on the role of his replacement, providing supportive testimonials from Charles Reed Peers, Robert Bosanquet, and H. J. Fleure. Although he had no prior museum experience, he was successful in his application and was appointed director. He then employed a close friend, Cyril Fox

Sir Cyril Fred Fox (16 December 1882 – 15 January 1967) was an English archaeologist and museum director.

Fox became keeper of archaeology at the National Museum of Wales, and subsequently served as director from 1926 to 1948. Many of his m ...

, to take on the vacated position of Keeper of Archaeology. Wheeler's proposed reforms included extending the institution's reach and influence throughout Wales by building affiliations with regional museums, and focusing on fundraising to finance the completion of the new museum premises. He obtained a £21,367 donation from the wealthy shipowner William Reardon Smith and appointed Smith to be the museum's treasurer, and also travelled to Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

, London, where he successfully urged the British Treasury to provide further funding for the museum. As a result, construction on the museum's new building was able to continue, and it was officially opened by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

in 1927.

London Museum: 1926–33

Upon the retirement of the Keeper of the London Museum, Harmon Oates, Wheeler was invited to fill the vacancy. He had been considering a return to London for some time and eagerly agreed, taking on the post, which was based at

Upon the retirement of the Keeper of the London Museum, Harmon Oates, Wheeler was invited to fill the vacancy. He had been considering a return to London for some time and eagerly agreed, taking on the post, which was based at Lancaster House

Lancaster House (originally known as York House and then Stafford House) is a mansion on The Mall, London, The Mall in the St James's district in the West End of London. Adjacent to The Green Park, it is next to Clarence House and St James ...

in the St James's

St James's is a district of Westminster, and a central district in the City of Westminster, London, forming part of the West End of London, West End. The area was once part of the northwestern gardens and parks of St. James's Palace and much of ...

area, in July 1926. In Wales, many felt that Wheeler had simply taken the directorship of the National Museum to advance his own career prospects, and that he had abandoned them when a better offer came along. Wheeler himself disagreed, believing that he had left Fox at the Museum as his obvious successor, and that the reforms he had implemented would therefore continue. The position initially provided Wheeler with an annual salary of £600, which resulted in a decline in living standards for his family, who moved into a flat near Victoria Station.

Tessa's biographer L. C. Carr later commented that together, the Wheelers "professionalized the London Museum". Wheeler expressed his opinion that the museum "had to be cleaned, expurgated, and catalogued; in general, turned from a junk shop into a tolerably rational institution". Focusing on reorganising the exhibits and developing a more efficient method of cataloguing the artefacts, he also wrote ''A Short Guide to the Collections'', before using the items in the museum to write three books: ''London and the Vikings'', ''London and the Saxons'', and ''London and the Romans''. Upon his arrival, the Treasury allocated the museum an annual budget of £5,000, which Wheeler deemed insufficient for its needs. In 1930, Wheeler persuaded them to increase that budget, as he highlighted increasing visitor numbers, publications, and acquisitions, as well as a rise in the number of educational projects. With this additional funding, he was able to employ more staff and increase his own annual salary to £900.

Soon after joining the museum, Wheeler was elected to the council of the Society of Antiquaries. Through the Society, he became involved in the debate as to who should finance archaeological supervision of building projects in Greater London

Greater London is an administrative area in England, coterminous with the London region, containing most of the continuous urban area of London. It contains 33 local government districts: the 32 London boroughs, which form a Ceremonial count ...

; his argument was that the City of London Corporation

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the local authority of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Kingdom's f ...

should provide the funding, although in 1926 it was agreed that the Society itself would employ a director of excavation based in Lancaster House to take on the position. Also involved in the largely moribund Royal Archaeological Institute, Wheeler organised its relocation to Lancaster House. In 1927, Wheeler took on an unpaid lectureship at University College London, where he established a graduate diploma course on archaeology; one of the first to enroll was Stuart Piggott. In 1928, Wheeler curated an exhibit at UCL on "Recent Work in British Archaeology", for which he attracted much press attention.

Wheeler was keen to continue archaeological fieldwork outside London, undertaking excavations every year from 1926 to 1939. After completing his excavation of the Carlaeon amphitheatre in 1928, he began fieldwork at the Roman settlement and temple in Lydney Park,

Wheeler was keen to continue archaeological fieldwork outside London, undertaking excavations every year from 1926 to 1939. After completing his excavation of the Carlaeon amphitheatre in 1928, he began fieldwork at the Roman settlement and temple in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

, having been invited to do so by the aristocratic landowner, Charles Bathurst. It was during these investigations that Wheeler personally discovered the Lydney Hoard of coinage. Wheeler and his wife jointly published their excavation report in 1932 as ''Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire'', which Piggott noted had "set the pattern" for all Wheeler's future excavation reports.

From there, Wheeler was invited to direct a Society of Antiquaries excavation at the Roman settlement of Verulamium, which existed on land recently acquired by the Corporation of St Albans. He took on this role for four seasons from 1930 to 1933, before leaving a fifth season of excavation under the control of the archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon and the architect A. W. G. Lowther. Wheeler enjoyed the opportunity to excavate at a civilian as opposed to military site, and also liked its proximity to his home in London. He was particularly interested in searching for a pre-Roman Iron Age oppidum

An ''oppidum'' (: ''oppida'') is a large fortified Iron Age Europe, Iron Age settlement or town. ''Oppida'' are primarily associated with the Celts, Celtic late La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread acros ...

at the site, noting that the existence of a nearby Catuvellauni

The Catuvellauni (Common Brittonic: *''Catu-wellaunī'', "war-chiefs") were a Celtic tribe or state of southeastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century.

The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and thei ...

settlement was attested to in both classical texts and numismatic evidence. With Wheeler focusing his attention on potential Iron Age evidence, Tessa concentrated on excavating the inside of the city walls; Wheeler had affairs with at least three assistants during the project. After Tessa wrote two interim reports, the final excavation report was finally published in 1936 as ''Verulamium: A Belgic and Two Roman Cities'', jointly written by Wheeler and his wife. The report resulted in the first major published criticism of Wheeler, produced by the young archaeologist Nowell Myres in a review for '' Antiquity''; although stating that there was much to praise about the work, he critiqued Wheeler's selective excavation, dubious dating, and guesswork. Wheeler responded with a piece in which he defended his work and launched a personal attack on both Myres and Myres's employer, Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

.

Institute of Archaeology: 1934–39

Wheeler had long desired to establish an academic institution devoted to archaeology that could be based in London. He hoped that it could become a centre in which to establish the professionalisation of archaeology as a discipline, with systematic training of students in methodological techniques of excavation and conservation and recognised professional standards; in his words, he hoped "to convert archaeology into a discipline worthy of that name in all senses". He further described his intention that the Institute should become "a laboratory: a laboratory of archaeological science". Many archaeologists shared his hopes, and to this end Petrie had donated much of his collection of Near Eastern artefacts to Wheeler, in the hope that it would be included in such an institution. Wheeler was later able to persuade the University of London, a federation of institutions across the capital, to support the venture, and both he and Tessa began raising funds from wealthy backers. In 1934, the Institute of Archaeology was officially opened, albeit at this point without premises or academic staff; the first students to enroll were Rachel Clay and Barbara Parker, who went on to have careers in the discipline. While Wheeler – who was still Keeper of the London Museum – took on the role of Honorary Director of the institute, he installed the archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon as secretary of the Management Committee, describing her as "a level-headed person, with useful experience". That June, he was appointed an Officer of the Order of Saint John (OStJ). After ending his work at Verulamium, Wheeler turned his attention to the late Iron Age hill-fort of Maiden Castle nearDorchester, Dorset

Dorchester ( ) is the county town of Dorset, England. It is situated between Poole and Bridport on the A35 trunk route. A historic market town, Dorchester is on the banks of the River Frome, Dorset, River Frome to the south of the Dorset Dow ...

, where he excavated for four seasons from 1934 to 1937. Co-directed by Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler, and the Curator of Dorset County Museum (Charles Drew), the project was carried out under the joint auspices of the Society of Antiquaries and the Dorset Field Club. With around 100 assistants each season, the dig constituted the largest excavation that had been conducted in Britain up to that point, with Wheeler organising weekly meetings with the press to inform them about any discoveries. He was keen to emphasise that his workforce consisted of many young people as well as both men and women, thus presenting the image of archaeology as a modern and advanced discipline. According to later historian Adam Stout, the Maiden Castle excavation was "one of the most famous British archaeological investigations of the twentieth century. It was the classic 'Wheeler dig', both in terms of scale of operations and the publicity which it generated."

Wheeler's excavation report was published in 1943 as ''Maiden Castle, Dorset''. The report's publication allowed further criticism to be voiced of Wheeler's approach and interpretations; in his review of the book, the archaeologist W. F. Grimes criticised the highly selective nature of the excavation, noting that Wheeler had not asked questions regarding the socio-economic issues of the community at Maiden Castle, aspects of past societies that had come to be of increasing interest to British archaeology. Over coming decades, as further excavations were carried out at the site and archaeologists developed a greater knowledge of Iron Age Britain, much of Wheeler's interpretation of the site and its development was shown to be wrong, in particular by the work of the archaeologist Niall Sharples.

In 1936, Wheeler embarked on a visit to the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, sailing from Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

to Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

, where he visited the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning –2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynast ...

tombs of Sakkara. From there he went via Sinai to Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. During this trip, he visited various archaeological projects, but was dismayed by the quality of their excavations; in particular, he noted that the American-run excavation at Tel Megiddo

Tel Megiddo (from ) is the site of the ancient city of Megiddo (; ), the remains of which form a tell or archaeological mound, situated in northern Israel at the western edge of the Jezreel Valley about southeast of Haifa near the depopulate ...

was adopting standards that had been rejected in Britain twenty-five years previously. He was away for six weeks, and upon his return to Europe discovered that his wife Tessa had died of a pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage of an pulmonary artery, artery in the lungs by a substance that has moved from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream (embolism). Symptoms of a PE may include dyspnea, shortness of breath, chest pain ...

after a minor operation on her toe. According to Tessa's biographer, for Wheeler this discovery was "the peak of mental misery, and marked the end of his ability to feel a certain kind of love". That winter, his father also died. By the summer of 1937, he had embarked on a new romance, with a young woman named Mavis de Vere Cole, widow of Horace de Vere Cole, who had first met Wheeler when visiting the Maiden Castle excavations with her then-lover, the painter Augustus John

Augustus Edwin John (4 January 1878 – 31 October 1961) was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a time he was considered the most important artist at work in Britain: Virginia Woolf remarked that by 1908 the era of John Singer Sarg ...

. After she eventually agreed to his repeated proposals, the two were married early in 1939 in a ceremony held at Caxton Hall, with a reception at Shelley House. They proceeded on a honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds after their wedding to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase in a couple ...

to the Middle East.

After a search that had taken several years, Wheeler was able to secure premises for the Institute of Archaeology: St. John's Lodge in Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, Borough of Camden (and historical ...

, central London. Left empty since its use as a hospital during the First World War, the building was owned by the Crown and was controlled by the First Commissioner of Works, William Ormsby-Gore; he was very sympathetic to archaeology, and leased the building to the Institute at a low rent. The St. John's Lodge premises were officially opened on 29 April 1937. During his speech at the ceremony, the University of London's Vice-Chancellor Charles Reed Peers made it clear that the building was only intended as a temporary home for the institute, which it was hoped would be able to move to Bloomsbury, the city's academic hub. In his speech, the university's Chancellor, Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone

Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone (Alexander Augustus Frederick William Alfred George; born Prince Alexander of Teck; 14 April 1874 – 16 January 1957), was a member of the extended British royal family, as a great-grandson of King Georg ...

, compared the new institution to both the Institute of Historical Research

The Institute of Historical Research (IHR) is a British educational organisation providing resources and training for historical researchers. It is part of the School of Advanced Study in the University of London and is located at Senate Hou ...

and the Courtauld Institute of Art

The Courtauld Institute of Art (), commonly referred to as The Courtauld, is a self-governing college of the University of London specialising in the study of the history of art and conservation.

The art collection is known particularly for ...

.

Wheeler had also become President of the Museums Association

The Museums Association (MA) is a professional membership organisation based in London for museum, gallery and heritage professionals and organisations of the United Kingdom. It also offers international membership.

History

The association w ...

, and in a presidential address given in Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

talked on the topic of preserving museum collections in wartime, believing that Britain's involvement in a second European conflict was imminent. In anticipation of this event, in August 1939 he arranged for the London Museum to place many of its most important collections into safe keeping. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

from Bristol University

The University of Bristol is a public research university in Bristol, England. It received its royal charter in 1909, although it can trace its roots to a Merchant Venturers' school founded in 1595 and University College, Bristol, which had ...

, and at the award ceremony met the Conservative Party politician Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, who was then engaged in writing his multi-volume '' A History of the English-Speaking Peoples''; Churchill asked Wheeler to help him in writing about late prehistoric and early medieval Britain, to which Wheeler agreed.

After Maiden Castle, Wheeler turned his attention to France, where the archaeological investigation of Iron Age sites had lagged behind developments in Britain. There, he oversaw a series of surveys and excavations with the aid of Leslie Scott, beginning with a survey tour of Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

in the winter of 1936–37. After this, Wheeler decided to excavate the oppidum at Camp d'Artus, near Huelgoat, Finistère

Finistère (, ; ) is a Departments of France, department of France in the extreme west of Brittany. Its prefecture is Quimper and its largest city is Brest, France, Brest. In 2019, it had a population of 915,090.Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

. Meanwhile, Scott had been placed in charge of an excavation at the smaller nearby hill fort of Kercaradec, near Quimper

Quimper (, ; ; or ) is a Communes of France, commune and Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Finistère Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in northwestern France.

Administration

Quimper is the ...

. In July 1939, the project focused its attention on Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, with excavations beginning at the Iron Age hill forts of Camp de Canada and Duclair. They were brought to an abrupt halt in September 1939 as the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

broke out in Europe, and the team evacuated back to Britain. Wheeler's excavation report, co-written with Katherine Richardson, was eventually published as ''Hill-forts of Northern France'' in 1957.

Second World War: 1939–45

Wheeler had been expecting and openly hoping for war withNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

for a year before the outbreak of hostilities; he believed that the United Kingdom's involvement in the conflict would remedy the shame that he thought had been brought upon the country by its signing of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

in September 1938. Volunteering for the armed services, on 18 July 1939 he returned to active service as a major (Special List). He was assigned to assemble the 48th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery at Enfield, where he set about recruiting volunteers, including his son Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* he He ..., a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name

* Michael (bishop elect)">Michael (surname)">he He ..., a given nam ...

. As the 48th swelled in size, it was converted into the 42nd Mobile Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

, which consisted of four batteries and was led by Wheeler – now promoted to the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel (effective 27 January 1940) – as Commanding Officer. Given the nickname of "Flash Alf" by those serving under him, he was recognised by colleagues as a ruthless disciplinarian and was blamed by many for the death of one of his soldiers from influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

during training. Having been appointed secretary of the Society of Antiquaries in 1939 and then director in 1940, he travelled to London to deal with society affairs on various occasions. In 1941 Wheeler was awarded a Fellowship of the British Academy. Mavis de Vere Cole - Wheeler’s wife, had meanwhile entered into an affair with a man named Clive Entwistle, who lambasted Wheeler as "that whiskered baboon". When Wheeler discovered Entwistle in bed with her, he initiated divorce proceedings that were finalised in March 1942.

In the summer of 1941, Wheeler and three of his batteries were assigned to fight against German and Italian forces in the North African Campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

. In September, they set sail from Glasgow aboard the RMS ''Empress of Russia''; because the Mediterranean was controlled largely by enemy naval forces, they were forced to travel via the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

, before taking shore leave in Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

. There, Wheeler visited the local kraal

Kraal (also spelled ''craal'' or ''kraul'') is an Afrikaans and Dutch language, Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an pen (enclosure), enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African Human settlement ...

s to compare them with the settlements of Iron Age Britain. The ship docked in Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

, where Wheeler and his men again took shore leave. They soon reached the British-controlled Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

, where they disembarked and were stationed on the shores of the Great Bitter Lake. There, Wheeler took a brief leave of absence to travel to Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, where he visited Petrie on his hospital deathbed. Back in Egypt, he gained permission to fly as a front gunner in a Wellington bomber on a bombing raid against Axis forces, to better understand what it was like for aircrew to be fired on by an anti-aircraft battery.

Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

and the advance on Axis-held Tripoli. On the way he became concerned that the archaeological sites of North Africa were being threatened both by the fighting and the occupying forces. After the British secured control of Libya, Wheeler visited Tripoli and Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by #Names, other names in classical antiquity, antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Established as a Punic people, Puni ...

, where he found that Roman remains had been damaged and vandalised by British troops; he brought about reforms to prevent this, lecturing to the troops on the importance of preserving archaeology, making many monuments out-of-bounds, and ensuring that the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

changed its plans to construct a radar station in the midst of a Roman settlement. Aware that the British were planning to invade and occupy the Italian island of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, he insisted that measures be introduced to preserve the historic and archaeological monuments on the island.

Promoted to the acting rank of brigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

on 1 May 1943, after the German surrender in North Africa, Wheeler was sent to Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

where he was part of the staff committee planning the invasion of Italy. There, he learned that the India Office

The India Office was a British government department in London established in 1858 to oversee the administration of the Provinces of India, through the British viceroy and other officials. The administered territories comprised most of the mo ...

had requested that the army relieve him of his duties to permit him to be appointed Director General of Archaeology in India. Although he had never been to the country, he agreed that he would take the job on the condition that he be permitted to take part in the invasion of Italy first. As intended, Wheeler and his 12th Anti-Aircraft Brigade then took part in the invasion of Sicily and then mainland Italy, where they were ordered to use their anti-aircraft guns to protect the British 10th Corps. As the Allies advanced north through Italy, Wheeler spent time in Naples