Michael A. Healy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Michael Augustine Healy (September 22, 1839 – August 30, 1904) was an American career officer with the

“I No Longer Call You Slaves”: The Healy Brothers, 1830-1910

''

Healy returned to Alaskan waters aboard the newly built in 1875. In 1880, by request of the captain of ''Corwin,'' he was transferred to serve as executive officer, but the assignment did not last long. In August 1881 he assumed his first command on ''Rush''. Renowned

Healy returned to Alaskan waters aboard the newly built in 1875. In 1880, by request of the captain of ''Corwin,'' he was transferred to serve as executive officer, but the assignment did not last long. In August 1881 he assumed his first command on ''Rush''. Renowned

Frederick E. Hoxie, pages 307-8Alleged Shelling of Alaska Villages: Letter of the Secretary of the Treasury

December 6, 1882 He attained the rank of captain on March 3, 1883. At this point in his career, Healy had earned a reputation as a person thoroughly familiar with Alaskan waters and as a commander who expected the most from his vessel and crew. He was at the same time known to be a hard drinker, and most of his junior officers found him difficult.Strobridge and Noble, pp 46-48 He was respected for his efforts to rescue vessels and crews in peril. Healy was often recognized for his humanitarian efforts, including being recognized by Congress for his life-saving work in the Arctic in 1885.Strobridge and Noble, p 49 He took command of ''Bear'' in 1887. His reputation with the whalers was so well established that when the

Healy, Michael A.; John C. Cantwell; Samuel B. McLenegan; Herbert W. Yemans (1889). ''Report of the Cruise of the Revenue Marine Steamer Corwin in the Arctic Ocean in the Year 1884''

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

Healy, M. A. (1887). ''Report of the Cruise of the Revenue Marine Steamer Corwin in the Arctic Ocean, 1885''

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office * Mentioned in “Alaska” by James Michener

United States Revenue Cutter Service

The United States Revenue Cutter Service was established by an Act of Congress () on 4 August 1790 as the Revenue-Marine at the recommendation of the nation's first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

The federal government bod ...

(predecessor of the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and Admiralty law, law enforcement military branch, service branch of the armed forces of the United States. It is one of the country's eight Uniformed services ...

), reaching the rank of captain. He has been recognized since the late 20th century as the first man of African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

descent to command a ship of the United States government.

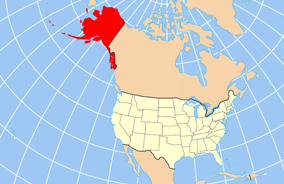

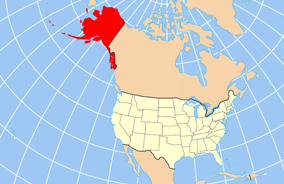

He commanded several vessels within the territory of the Alaskan coastline.

Following U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (; May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opp ...

's Alaska purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the purchase of Russian colonization of North America, Alaska from the Russian Empire by the United States for a sum of $7.2 million in 1867 (equivalent to $ million in ). On May 15 of that year, the United St ...

of the vast region in 1867, Healy patrolled the of Alaskan coastline for more than 20 years, earning great respect from the natives and seafarers alike. After commercial fishing had depleted the whale and seal populations, his assistance with the introduction of Siberian reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

helped prevent starvation among the Alaskan Natives

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tlingi ...

. The author Jack London

John Griffith London (; January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors t ...

was inspired by Healy's command of the renowned USRC ''Bear''. It had a thick wooden hull, and was powered by steam-and-sail for use as a proto-icebreaker; it was put into service as a cutter

Cutter may refer to:

Tools

* Bolt cutter

* Box cutter

* Cigar cutter

* Cookie cutter

* Cutter (hydraulic rescue tool)

* Glass cutter

* Meat cutter

* Milling cutter

* Paper cutter

* Pizza cutter

* Side cutter

People

* Cutter (surname)

* Cutt ...

in 1884.

Nicknamed "Hell Roaring Mike", Healy was the fifth of 10 children of the Healy family of Georgia, known for their achievements in the North after being born into slavery. Their parents were an Irish-born planter and his African-American mixed-race

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mul ...

slave, with whom he had a common-law marriage

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, de facto marriage, more uxorio or marriage by habit and repute, is a marriage that results from the parties' agreement to consider themselves married, follo ...

. His father arranged for the children to be formally educated at boarding schools in the North. Predominately European in ancestry, they identified as Irish Catholics.

USCGC ''Healy'', commissioned in 1999, was named in his honor.

Early life and education

Healy was born into slavery nearMacon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States. Situated near the Atlantic Seaboard fall line, fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is southeast of Atlanta and near the ...

, in 1839, as the fifth of ten children of Michael Morris Healy, an Irish immigrant planter, and Mary Eliza Smith, his common-law wife

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, de facto marriage, more uxorio or marriage by habit and repute, is a marriage that results from the parties' agreement to consider themselves married, follo ...

, a mixed-race

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mul ...

African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

slave."Captain Michael A. Healy, USRCS", Personnel Biographies, U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

The senior Healy was born in 1795 in Roscommon, Ireland, and immigrated to the U.S. in 1818 as a young man. He eventually acquired of land in Georgia near Macon. He eventually owned 49 slaves as workers for his plantation;O'Toole, James M.; "Passing Free", ''Boston College Magazine,'' Summer 2003, Boston College website among them was 16-year-old Mary Eliza Smith (or Clark), described as an octoroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron (in the United Kingdom, the term quarter-caste is used) was a person with one-quarter African/ Aboriginal and three-quarters European ancestry. Similar classifica ...

or a mulatto

( , ) is a Race (human categorization), racial classification that refers to people of mixed Sub-Saharan African, African and Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry only. When speaking or writing about a singular woman in English, the ...

, whom he took as his wife in 1829. Under the '' partus'' principle in slave law, the Healy children were legally slaves because their mother was enslaved. As such they were prohibited formal education in Georgia, and their father sent them north to be schooled, a common practice of wealthy white planters who had mixed-race children.

Though not unusual, the Healys' common-law marriage violated laws against inter-racial marriage. Healy's wealth and ambition provided for his children's education. Most of the children, all but one surviving infancy, achieved noteworthy success as adults. In the North, the Healy siblings were educated as and identified as Irish Catholics. They were part of a growing ethnic group in the mid-19th century United States. During the late 20th century, their individual professional achievements were claimed as notable firsts for African Americans.

The oldest son, James Augustine Healy

James Augustine Healy (April 6, 1830 – August 5, 1900) was an American prelate of the Catholic Church. He was the first known African American to serve as a Catholic priest or bishop. With his predominantly European ancestry, Healy passed ...

, born in 1830, first went to a Quaker school in New York and New Jersey. His father transferred him at age 14 to preparatory classes for the College of Holy Cross

The College of the Holy Cross is a Private college, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States. It was founded by educators Benedict Joseph Fenwi ...

in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Massachusetts, second-most populous city in the U.S. state of Massachusetts and the list of United States cities by population, 113th most populous city in the United States. Named after Worcester ...

. His three younger brothers soon joined him: Hugh, 12, Patrick Francis Healy

Patrick Francis Healy (February 27, 1834January 10, 1910) was an American Catholic priest and Jesuit who was an influential president of Georgetown University, becoming known as its "second founder". The university's flagship building, Healy ...

, 10, and Alexander Sherwood Healy (known as Sherwood), 8. Michael, then only 6, was not enrolled at Holy Cross until 1849."Healy, Bishop James Augustine (1830-1900)", Online Encyclopedia, BlackPast.org website

All four of the older brothers graduated from Holy Cross. The three eldest entered the priesthood. After attending seminaries in Montreal and Paris, James was ordained a priest at the Cathedral of Notre Dame

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a Medieval architecture, medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissemen ...

in 1854. In the 20th century he was claimed as the first African-American priest in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. In 1875, he became the second bishop of the Diocese of Portland

The Diocese of Portland () is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory, or diocese, of the Catholic Church for the entire state of Maine in the United States. It is a suffragan diocese of the metropolitan Archdiocese of Boston.

The mother church ...

, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, and is known as the first U.S. Catholic African-American bishop."James Augustine Healy, the Children's Priest", The Registry, African-American Registry website

Patrick Healy became a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

and was the first African American to earn a PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

; he completed it at Saint-Sulpice Seminary in Paris. At the age of 39, in 1874, he assumed the presidency of Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian liberal arts college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Chartered in 1829, Georgetown was the first Baptist college west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The college offers over 40 undergraduate degrees and a Mas ...

, at the time the largest Catholic college in the U.S."Healy, Patrick (1834-1910)", ''Online Encyclopedia,'' BlackPast.org website

Sherwood Healy was also ordained as a priest, and earned a PhD at Saint-Sulpice. An expert in canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, he served as director of the seminary in Troy, New York

Troy is a city in and the county seat of Rensselaer County, New York, United States. It is located on the western edge of the county, on the eastern bank of the Hudson River just northeast of the capital city of Albany, New York, Albany. At the ...

. Later he became rector of the cathedral in Boston. Sherwood was musical and formed the Boston Choral Union, which helped raise funds for a new cathedral. He died at age 39.''

Patheos

Patheos is a non-denominational, non-partisan online media company providing information and commentary from various, mostly religious, perspectives.

Upon its launch in May 2009, the website was primarily geared toward learning about religions ...

'', Pat McNamara, February 2, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

The three Healy sisters attended parochial schools in Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

, Quebec, Canada, ultimately entering Catholic orders. Martha, the oldest, left her convent after several years and moved to Boston, where two brothers were living and working. She married an Irish immigrant and had a son with him. Josephine lived with her family in Boston before joining the Religious Hospitallers of Saint Joseph

Religion is a range of social-cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural, transcen ...

. Eliza

ELIZA is an early natural language processing computer program developed from 1964 to 1967 at MIT by Joseph Weizenbaum. Created to explore communication between humans and machines, ELIZA simulated conversation by using a pattern matching and ...

joined the Congregation of Notre Dame of Montreal

The Congrégation de Notre Dame (CND) is a religious community for women founded in 1658 in Ville Marie (Montreal), in the colony of New France, now part of Canada. It was established by Marguerite Bourgeoys, who was recruited in France to creat ...

, where she was known as Sister Mary Magdalen. After teaching in Quebec and Ontario, in 1903 Eliza was appointed abbess or mother superior of the convent and school of Villa Barlow in St. Albans, Vermont. She has become recognized as the first African American to reach this position.Healy, Eliza ister Mary Magdalen(1846–1918)", Black Past Online Encyclopedia, BlackPast.org website

In May 1850, the Healys' mother Mary Eliza died, followed four months later by her husband, Michael Morris Healy.Strobridge and Noble, p 44 leaving James as the head of the family. He was unable to convince young Michael to follow him into the priesthood. Unhappy and rebellious at Holy Cross, Michael was sent in 1854 to a French seminary. In 1855, he left that school for England, where he signed on as a cabin boy with the ''Jumna'', an American East Indian clipper, eventually serving as an officer on merchant vessels.Strobridge and Noble, p 45

Career

U.S. Revenue Cutter Service

In 1864 during the American Civil War, Healy returned to his family in Boston, where he applied for a commission in the Revenue Cutter Service. He was accepted as a third lieutenant on March 7, 1865, and his commission was signed by PresidentAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

.Noble, p. 32 He was promoted to second lieutenant on June 6, 1866. Under U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (; May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opp ...

, during the administration of President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

, the Alaska purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the purchase of Russian colonization of North America, Alaska from the Russian Empire by the United States for a sum of $7.2 million in 1867 (equivalent to $ million in ). On May 15 of that year, the United St ...

was made on March 29, 1867. The huge territory, with of coastline, was initially referred to by many skeptics as "Seward's Folly" or "Seward's Ice Box."

The Revenue Cutter Service became the principal government agency for transporting government officials, scientists, and doctors, as well as serving as the principal US law enforcement agency in the Alaska Territory.King, p 22 Healy was assigned to the newly commissioned when it sailed around Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

and arrived at Sitka, Alaska

Sitka (; ) is a municipal home rule, unified Consolidated city-county, city-borough in the southeast portion of the U.S. state of Alaska. It was under Russian America, Russian rule from 1799 to 1867. The city is situated on the west side of Ba ...

, on November 24, 1868.Strobridge and Noble, p 46 The following year he was transferred to in San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. While serving on ''Lincoln,'' he was promoted to first lieutenant on July 21, 1870. On January 8, 1872, he received orders to report aboard home-ported in New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. At the 2020 census, New Bedford had a population of 101,079, making it the state's ninth-l ...

, where he became familiar with the masters of whaling ships. His experience in this period played an important part of his later career in Alaska.

"Hell Roaring Mike"

Healy returned to Alaskan waters aboard the newly built in 1875. In 1880, by request of the captain of ''Corwin,'' he was transferred to serve as executive officer, but the assignment did not last long. In August 1881 he assumed his first command on ''Rush''. Renowned

Healy returned to Alaskan waters aboard the newly built in 1875. In 1880, by request of the captain of ''Corwin,'' he was transferred to serve as executive officer, but the assignment did not last long. In August 1881 he assumed his first command on ''Rush''. Renowned naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the national park, National Parks", was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologi ...

made one voyage with Healy as part of an ambitious government scientific program. Healy was serving as First Officer of during the summer of 1881.Strobridge and Noble, p 39Strobridge and Noble, p 78

By 1882 Healy was given command of ''Corwin'' and was already thoroughly familiar with the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

and Alaska. In this command, he enforced liquor laws, protected seal and whale populations under treaty; delivered supplies, mail and medicines to remote villages; returned deserters to merchant ships, collected weather data, rendered medical assistance, conducted search and rescue, enforced federal laws, and accomplished exploration work.King, p 42 In October 1882 he took part in the Angoon Bombardment, in which the village of Angoon, Alaska

Angoon (sometimes formerly spelled Angun, ) is a city on Admiralty Island, Alaska, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 572; by the 2010 census the population had declined to 459. For statistical purposes, it is in the Hoonah ...

was destroyed following hostage taking by the Tlingit

The Tlingit or Lingít ( ) are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. , they constitute two of the 231 federally recognized List of Alaska Native tribal entities, Tribes of Alaska. Most Tlingit are Alaska Natives; ...

.The Oxford Handbook of American Indian HistoryFrederick E. Hoxie, pages 307-8Alleged Shelling of Alaska Villages: Letter of the Secretary of the Treasury

December 6, 1882 He attained the rank of captain on March 3, 1883. At this point in his career, Healy had earned a reputation as a person thoroughly familiar with Alaskan waters and as a commander who expected the most from his vessel and crew. He was at the same time known to be a hard drinker, and most of his junior officers found him difficult.Strobridge and Noble, pp 46-48 He was respected for his efforts to rescue vessels and crews in peril. Healy was often recognized for his humanitarian efforts, including being recognized by Congress for his life-saving work in the Arctic in 1885.Strobridge and Noble, p 49 He took command of ''Bear'' in 1887. His reputation with the whalers was so well established that when the

Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program that "linked the religious and the secular through concerted and far ...

and the Seaman's Union requested a board of inquiry to consider charges of drunkenness and cruelty against him, the whaler skippers quickly got the drunkenness charges dismissed. The cruelty charges stemmed from an incident aboard the whaler ''Estrella'' in 1889: Healy had a seaman "triced up" to restore order. Healy defended his actions as an effort to quell a mutiny, and the charge was eventually dismissed.

In July 1889, Healy paid a courtesy call to the skipper of USRC ''Rush'', Captain Leonard G. Shepard

Leonard G. Shepard (November 10, 1846March 1, 1895), was a captain in the United States Revenue Cutter Service and was appointed in 1889 by Secretary of the Treasury William Windom as the first military head of the service since 1869. His formal ...

, in an intoxicated state, a serious breach of naval etiquette. Shortly thereafter, Shepard became the Chief of the Revenue Cutter Bureau and he wrote Healy warning him that if he could not control his drinking, he could face loss of command.Strobridge and Noble, p 50 Healy replied stating that he "pledge to you by all I hold most sacred that while I live never to touch intoxicants of any kind or description....One thing I will hate and that is to give up my command of the ''Bear''. I love the ship, tho t is

T, or t, is the twentieth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''.

It is d ...

hard work."

During the last two decades of the 19th century, Healy was essentially the federal government's law enforcement presence in the vast territory. In his twenty years of service between San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

and Point Barrow

Point Barrow or Nuvuk is a headland on the Arctic coast in the U.S. state of Alaska, northeast of Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow). It is the northernmost point of all the territory of the United States, at , south of the North Pole. (The northe ...

, he acted as judge, doctor, and policeman to Alaskan natives, merchant seamen and whaling crews. The Native Americans

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

and Alaskan Natives

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tlingi ...

throughout the vast regions of the north came to know and respect him and called his ship "Healy's Fire Canoe.""Captain Michael A. Healy", ''Icebreaker Science Operations,'' U.S. Coast Guard During visits to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, across the Bering Sea from the Alaskan coast, Healy observed that the Chukchi people

The Chukchi, or Chukchee (, ''ḷygʺoravètḷʹèt, o'ravètḷʹèt''), are a Siberian ethnic group native to the Chukchi Peninsula, the shores of the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea region of the Arctic Ocean all within modern Russia. They s ...

had domesticated caribou (reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

), and used them for food, travel, and clothing. He had noted the reduction in the seal and whale populations in Alaska from commercial fishing activities. To compensate for this and aid in transportation, working with Reverend Sheldon Jackson

Sheldon Jackson (May 18, 1834 – May 2, 1909) was a Presbyterian minister, missionary, and political leader. During this career he travelled about one million miles (1.6 million km) and established more than one hundred missions and churches ...

, a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

and political leader in the territory, Healy helped introduce reindeer from Siberia to Alaska as a source of food, clothing and other necessities for the Native peoples. This work was noted in the ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American conservative news website and former newspaper based in Manhattan, New York. From 2009 to 2021, it operated as an (occasional and erratic) online-only publisher of political and economic opinion pieces, as we ...

'' newspaper in 1894. Healy's compassion for the native population was expressed in many deeds and in his standing order: "Never make a promise to a native you do not intend to keep to the letter."

Later life and death

Healy retired in 1903 at the mandatory retirement age of 64. He died on August 30, 1904, in San Francisco, of aheart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

. He was buried in Colma, California

Colma (Ohlone for "Springs") is a small incorporated List of municipalities in California, town in San Mateo County, California, United States, on the San Francisco Peninsula in the San Francisco Bay Area. The population was 1,507 at the 2020 U ...

. At the time, his African-American ancestry was not generally known; he was of majority-white ancestry and had identified with white Catholic and maritime communities.Strobridge and Noble, p 175

Personal life

In 1865, Healy married Mary Jane Roach, the daughter of Irish immigrants. She was a supportive wife who traveled with her husband. Despite 18 pregnancies, she had only one child who survived, a son named Frederick who was born in 1870. He established his life in northern California, married and had a family.Legacy

Over a century later, Healy's Coast Guard successors conduct missions reminiscent of his groundbreaking work: protecting the natural resources of the region, suppressing illegal trade, resupply of remote outposts, enforcement of the law, and search and rescue. Even in the early days of Arctic operations, science was an important part of the mission. Healy is now known as the first African-American to command a ship of the United States government. Commissioned in 1999, the research icebreaker USCGC ''Healy'' was named in his honor. To commemorate the entire family's achievements, the former site inJones County, Georgia

Jones County is a county in the central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 28,347. The county seat is Gray. The county was created on December 10, 1807, and named after U.S. Representative Jame ...

of the Healy plantation is called Healy Point. The area is the location of the Healy Point Country Club.

Notes

;Footnotes ;Citations ;References cited * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*James M. O'Toole, ''Passing for White: Race, Religion, and the Healy Family, 1820–1920'',University of Massachusetts Press

The University of Massachusetts Press is a university press that is part of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The press was founded in 1963, publishing scholarly books and non-fiction. The press imprint is overseen by an interdisciplinar ...

, 2003,

*Dennis L. Noble and Truman R. Strobridge, ''Captain "Hell Roaring" Mike Healy: From American Slave to Arctic Hero'', University Press of Florida, c2009,

Healy, Michael A.; John C. Cantwell; Samuel B. McLenegan; Herbert W. Yemans (1889). ''Report of the Cruise of the Revenue Marine Steamer Corwin in the Arctic Ocean in the Year 1884''

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

Healy, M. A. (1887). ''Report of the Cruise of the Revenue Marine Steamer Corwin in the Arctic Ocean, 1885''

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office * Mentioned in “Alaska” by James Michener

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Healy, Michael A. 1839 births 1904 deaths American people of Irish descent People from Jones County, Georgia United States Revenue Cutter Service officers College of the Holy Cross alumni Healy family (United States) Catholics from Georgia (U.S. state) African-American Catholics