Metre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The metre ( British spelling) or meter ( American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the

As a result of the Lumières and during the

As a result of the Lumières and during the

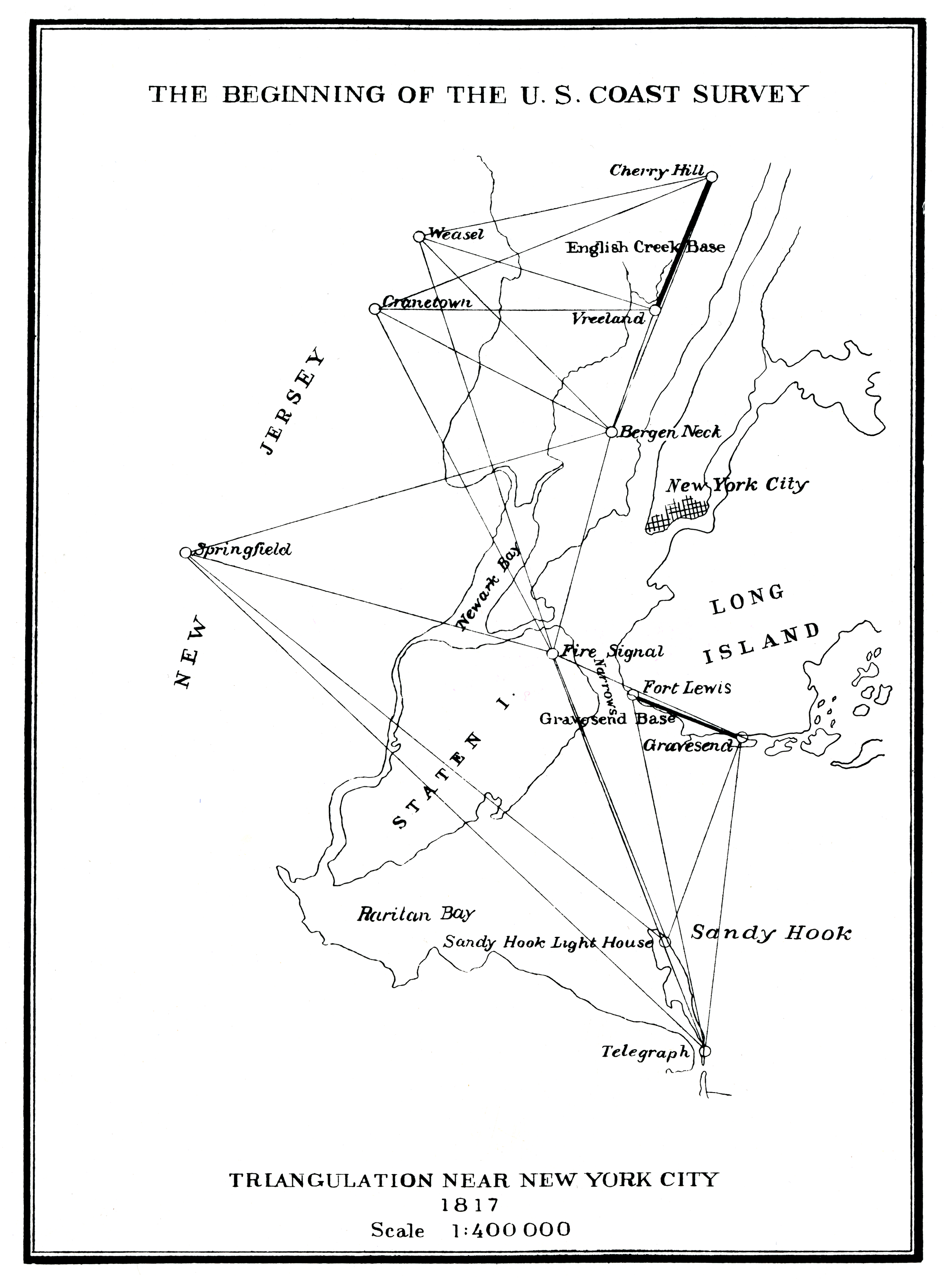

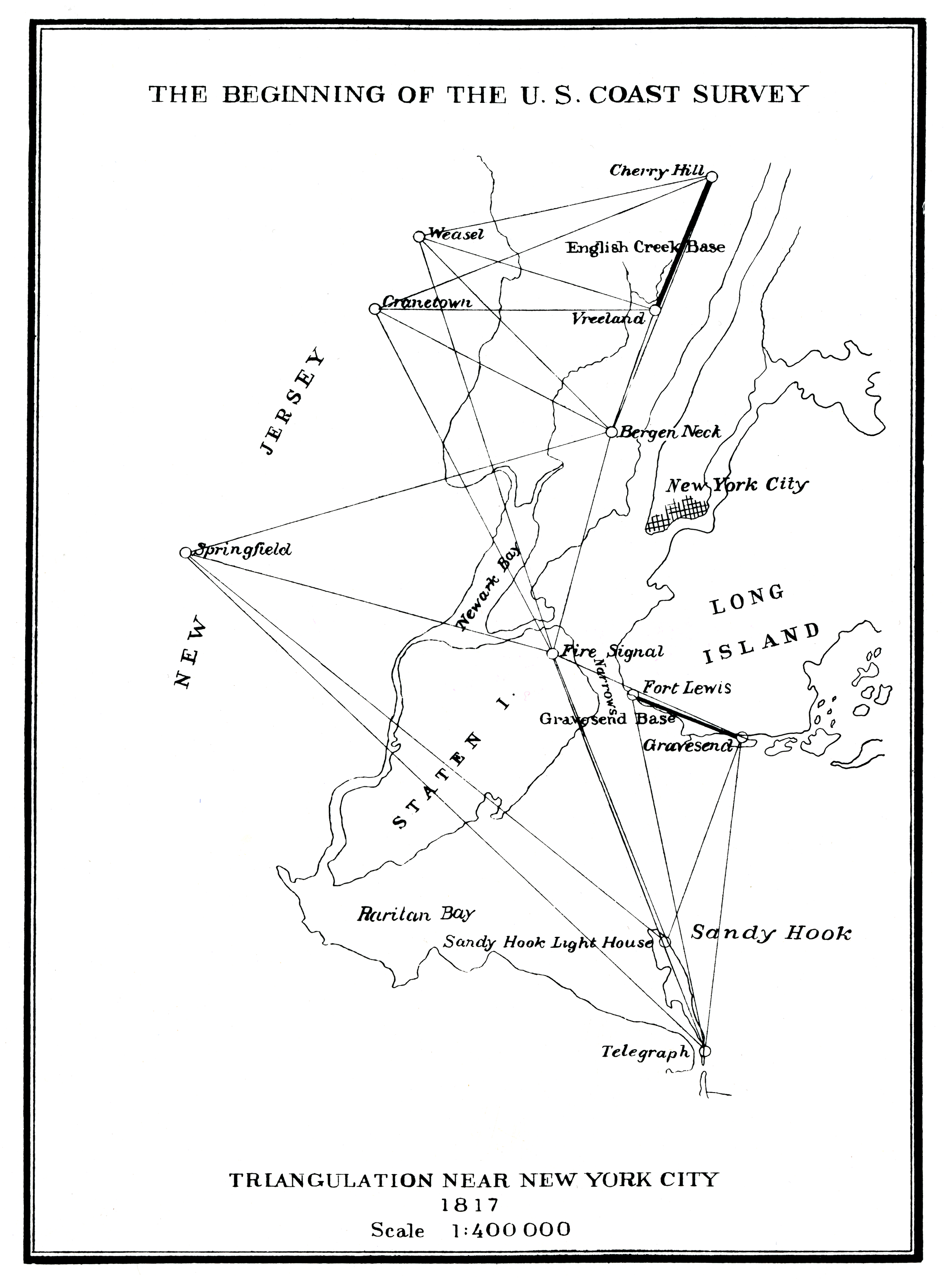

In 1816, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was appointed first Superintendent of the

In 1816, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was appointed first Superintendent of the  In 1866, at the meeting of the Permanent Commission of the association in Neuchâtel, Antoine Yvon Villarceau announced that he had checked eight points of the French arc. He confirmed that the metre was too short. It then became urgent to undertake a complete revision of the meridian arc. Moreover, while the extension of the French meridian arc to the Balearic Islands (1803–1807) had seemed to confirm the length of the metre, this survey had not been secured by any baseline in Spain. For that reason, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero's announcement, at this conference, of his 1858 measurement of a baseline in Madridejos was of particular importance. Indeed surveyors determined the size of

In 1866, at the meeting of the Permanent Commission of the association in Neuchâtel, Antoine Yvon Villarceau announced that he had checked eight points of the French arc. He confirmed that the metre was too short. It then became urgent to undertake a complete revision of the meridian arc. Moreover, while the extension of the French meridian arc to the Balearic Islands (1803–1807) had seemed to confirm the length of the metre, this survey had not been secured by any baseline in Spain. For that reason, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero's announcement, at this conference, of his 1858 measurement of a baseline in Madridejos was of particular importance. Indeed surveyors determined the size of  In the 1870s and in light of modern precision, a series of international conferences was held to devise new metric standards. When a conflict broke out regarding the presence of impurities in the metre-alloy of 1874, a member of the Preparatory Committee since 1870 and Spanish representative at the Paris Conference in 1875, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero intervened with the

In the 1870s and in light of modern precision, a series of international conferences was held to devise new metric standards. When a conflict broke out regarding the presence of impurities in the metre-alloy of 1874, a member of the Preparatory Committee since 1870 and Spanish representative at the Paris Conference in 1875, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero intervened with the  The comparison of the new prototypes of the metre with each other and with the Committee metre (French: '' Mètre des Archives'') involved the development of special measuring equipment and the definition of a reproducible temperature scale. The BIPM's thermometry work led to the discovery of special alloys of iron-nickel, in particular invar, for which its director, the Swiss physicist Charles-Edouard Guillaume, was granted the Nobel Prize for physics in 1920.

The comparison of the new prototypes of the metre with each other and with the Committee metre (French: '' Mètre des Archives'') involved the development of special measuring equipment and the definition of a reproducible temperature scale. The BIPM's thermometry work led to the discovery of special alloys of iron-nickel, in particular invar, for which its director, the Swiss physicist Charles-Edouard Guillaume, was granted the Nobel Prize for physics in 1920.

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated, the progress of metrology combined with those of gravimetry through improvement of Kater's pendulum led to a new era of

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated, the progress of metrology combined with those of gravimetry through improvement of Kater's pendulum led to a new era of  Efforts to supplement the various national surveying systems, which began in the 19th century with the foundation of the '' Mitteleuropäische Gradmessung'', resulted in a series of global ellipsoids of the Earth (e.g., Helmert 1906, Hayford 1910 and 1924) which would later lead to develop the

Efforts to supplement the various national surveying systems, which began in the 19th century with the foundation of the '' Mitteleuropäische Gradmessung'', resulted in a series of global ellipsoids of the Earth (e.g., Helmert 1906, Hayford 1910 and 1924) which would later lead to develop the

modified Edlén equation

or th

Ciddor equation

The documentation provide

a discussion of how to choose

between the two possibilities. As described by NIST, in air, the uncertainties in characterising the medium are dominated by errors in measuring temperature and pressure. Errors in the theoretical formulas used are secondary. By implementing a refractive index correction such as this, an approximate realisation of the metre can be implemented in air, for example, using the formulation of the metre as wavelengths of helium–neon laser light in a vacuum, and converting the wavelengths in a vacuum to wavelengths in air. Air is only one possible medium to use in a realisation of the metre, and any partial vacuum can be used, or some inert atmosphere like helium gas, provided the appropriate corrections for refractive index are implemented. The metre is ''defined'' as the path length travelled by light in a given time, and practical laboratory length measurements in metres are determined by counting the number of wavelengths of laser light of one of the standard types that fit into the length, and converting the selected unit of wavelength to metres. Three major factors limit the accuracy attainable with laser interferometers for a length measurement: A more detailed listing of errors can be found in Zagar, 1999, pp. 6–65''ff''. * uncertainty in vacuum wavelength of the source, * uncertainty in the refractive index of the medium, * least count resolution of the interferometer. Of these, the last is peculiar to the interferometer itself. The conversion of a length in wavelengths to a length in metres is based upon the relation : which converts the unit of wavelength ''λ'' to metres using ''c'', the speed of light in vacuum in m/s. Here ''n'' is the refractive index of the medium in which the measurement is made, and ''f'' is the measured frequency of the source. Although conversion from wavelengths to metres introduces an additional error in the overall length due to measurement error in determining the refractive index and the frequency, the measurement of frequency is one of the most accurate measurements available. The CIPM issued a clarification in 2002:

''Refinement of values for the yard and the pound''

Washington DC: National Bureau of Standards, republished on National Geodetic Survey web site and the Federal Register (Doc. 59-5442, Filed, 30 June 1959) * * * * * *

Retrieved 26 May 2010. * National Institute of Standards and Technology. (27 June 2011).

NIST-F1 Cesium Fountain Atomic Clock

'. Author. * National Physical Laboratory. (25 March 2010).

Iodine-Stabilised Lasers

'. Author. * * Republic of the Philippines. (2 December 1978).

'. Author. * Republic of the Philippines. (10 October 1991). '' ttps://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/1991/10oct/19911010-RA-7160-CCA.pdf Republic Act No. 7160: The Local Government Code of the Philippines'. Author. * Supreme Court of the Philippines (Second Division). (20 January 2010).

G.R. No. 185240

'. Author. * Taylor, B.N. and Thompson, A. (Eds.). (2008a)

''The International System of Units (SI)''

United States version of the English text of the eighth edition (2006) of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures publication ''Le Système International d’ Unités (SI)'' (Special Publication 330). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 18 August 2008. * Taylor, B.N. and Thompson, A. (2008b)

''Guide for the Use of the International System of Units''

(Special Publication 811). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 23 August 2008. * Turner, J. (Deputy Director of the National Institute of Standards and Technology). (16 May 2008

"Interpretation of the International System of Units (the Metric System of Measurement) for the United States"

''Federal Register'' Vol. 73, No. 96, p.28432-3. * Zagar, B.G. (1999)

Laser interferometer displacement sensors

in J.G. Webster (ed.). ''The Measurement, Instrumentation, and Sensors Handbook.'' CRC Press. . {{Authority control SI base units

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its prefixed forms are also used relatively frequently.

The metre was originally defined in 1793 as one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can al ...

to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

along a great circle, so the Earth's circumference is approximately km. In 1799, the metre was redefined in terms of a prototype metre bar (the actual bar used was changed in 1889). In 1960, the metre was redefined in terms of a certain number of wavelengths of a certain emission line of krypton-86. The current definition was adopted in 1983 and modified slightly in 2002 to clarify that the metre is a measure of proper length. From 1983 until 2019, the metre was formally defined as the length of the path travelled by light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 te ...

in a vacuum in of a second. After the 2019 redefinition of the SI base units, this definition was rephrased to include the definition of a second in terms of the caesium frequency .

Spelling

''Metre'' is the standard spelling of the metric unit for length in nearly all English-speaking nations except the United States and the Philippines, which use ''meter.'' OtherWest Germanic languages

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages). The West Germanic branch is classically subdivided into ...

, such as German and Dutch, and North Germanic languages

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also ...

, such as Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, likewise spell the word ''Meter'' or ''meter''.

Measuring devices (such as ammeter, speedometer) are spelled "-meter" in all variants of English. The suffix "-meter" has the same Greek origin as the unit of length.

Etymology

The etymological roots of ''metre'' can be traced to the Greek verb () (to measure, count or compare) and noun () (a measure), which were used for physical measurement, for poetic metre and by extension for moderation or avoiding extremism (as in "be measured in your response"). This range of uses is also found in Latin (), French (), English and other languages. The Greek word is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root '' *meh₁-'' 'to measure'. The motto () in the seal of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), which was a saying of the Greek statesman and philosopher Pittacus of Mytilene and may be translated as "Use measure!", thus calls for both measurement and moderation. The use of the word ''metre'' (for the French unit ) in English began at least as early as 1797.Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

, Clarendon Press 2nd ed.1989, vol.IX p.697 col.3.

History of definition

Pendulum or meridian

In 1671, Jean Picard measured the length of a " seconds pendulum" and proposed a unit of measurement twice that length to be called the universal toise (French: ''Toise universelle''). In 1675,Tito Livio Burattini

Tito Livio Burattini ( pl, Tytus Liwiusz Burattini, 8 March 1617 – 17 November 1681) was an inventor, architect, Egyptologist, scientist, instrument-maker, traveller, engineer, and nobleman, who spent his working life in Poland and Lithu ...

suggested the term metre for a unit of length based on a pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a wikt:pivot, pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, Mechanical equilibrium, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that ...

length, but then it was discovered that the length of a seconds pendulum varies from place to place.

Since Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

, geographers had used meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is to ...

s to assess the size of the Earth, which in 1669, Jean Picard determined to have a radius of toises, treated as a simple sphere. In the 18th century, geodesy

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), Earth rotation, orientation in space, and Earth's gravity, gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properti ...

grew in importance as a means of empirically demonstrating the theory of gravity, which Émilie du Châtelet

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet (; 17 December 1706 – 10 September 1749) was a French natural philosophy, natural philosopher and mathematician from the early 1730s until her maternal death, death due to compli ...

promoted in France in combination with Leibniz mathematical work, and because the radius of the Earth was the unit to which all celestial distances were to be referred.

Meridional definition

As a result of the Lumières and during the

As a result of the Lumières and during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

charged a commission with determining a single scale for all measures. On 7 October 1790 that commission advised the adoption of a decimal system, and on 19 March 1791 advised the adoption of the term ''mètre'' ("measure"), a basic unit of length, which they defined as equal to one ten-millionth of the quarter meridian, the distance between the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

and the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can al ...

along the meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

through Paris. On 26 March 1791, the French National Constituent Assembly adopted the proposal.

The French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

commissioned an expedition led by Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

, lasting from 1792 to 1799, which attempted to accurately measure the distance between a belfry in Dunkerque and Montjuïc castle in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ...

at the longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

of the Paris Panthéon (see meridian arc of Delambre and Méchain

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

). The expedition was fictionalised in Denis Guedj, ''Le Mètre du Monde''. Ken Alder wrote factually about the expedition in ''The Measure of All Things: the seven year odyssey and hidden error that transformed the world''. This portion of the Paris meridian was to serve as the basis for the length of the half meridian connecting the North Pole with the Equator. From 1801 to 1812 France adopted this definition of the metre as its official unit of length based on results from this expedition combined with those of the Geodesic Mission to Peru. The latter was related by Larrie D. Ferreiro in ''Measure of the Earth: The Enlightenment Expedition that Reshaped Our World''.

In the 19th century, geodesy underwent a revolution through advances in mathematics as well as improvements in the instruments and methods of observation, for instance accounting for individual bias in terms of the personal equation. The application of the least squares method to meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is to ...

measurements demonstrated the importance of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

in geodesy. On the other hand, the invention of the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

made it possible to measure parallel arcs, and the improvement of the reversible pendulum

A Kater's pendulum is a reversible free swinging pendulum invented by British physicist and army captain Henry Kater in 1817 for use as a gravimeter instrument to measure the local acceleration of gravity. Its advantage is that, unlike previo ...

gave rise to the study of the Earth's gravitational field. A more accurate determination of the Figure of the Earth

Figure of the Earth is a term of art in geodesy that refers to the size and shape used to model Earth. The size and shape it refers to depend on context, including the precision needed for the model. A sphere is a well-known historical approxima ...

would soon result from the measurement of the Struve Geodetic Arc (1816–1855) and would have given another value for the definition of this standard of length. This did not invalidate the metre but highlighted that progress in science would allow better measurement of Earth's size and shape.

In 1832, Carl Friedrich Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gauß ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refe ...

studied the Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magneti ...

and proposed adding the second to the basic units of the metre and the kilogram in the form of the CGS system ( centimetre, gram

The gram (originally gramme; SI unit symbol g) is a unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI) equal to one one thousandth of a kilogram.

Originally defined as of 1795 as "the absolute weight of a volume of pure water equal to ...

, second). In 1836, he founded the ''Magnetischer Verein'', the first international scientific association, in collaboration with Alexander von Humboldt and Wilhelm Edouard Weber. The coordination of the observation of geophysical phenomena such as the Earth's magnetic field, lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

and gravity in different points of the globe stimulated the creation of the first international scientific associations. The foundation of the ''Magnetischer Verein'' would be followed by that of the Central European Arc Measurement (German: ''Mitteleuropaïsche Gradmessung'') on the initiative of Johann Jacob Baeyer

Johann Jacob Baeyer (born 5 November 1794 in Berlin, died 10 September 1885 in Berlin) was a German geodesist and a lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many ...

in 1863, and by that of the International Meteorological Organisation whose second president, the Swiss meteorologist and physicist, Heinrich von Wild would represent Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

at the International Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (GCWM; french: Conférence générale des poids et mesures, CGPM) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established ...

(CIPM).

International prototype metre bar

In 1816, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was appointed first Superintendent of the

In 1816, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was appointed first Superintendent of the Survey of the Coast

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey (abbreviated USC&GS), known from 1807 to 1836 as the Survey of the Coast and from 1836 until 1878 as the United States Coast Survey, was the first scientific agency of the United States Government. It ...

. Trained in geodesy in Switzerland, France and Germany, Hassler had brought a standard metre made in Paris to the United States in 1805. He designed a baseline apparatus which instead of bringing different bars in actual contact during measurements, used only one bar calibrated on the metre and optical contact. Thus the metre became the unit of length for geodesy

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), Earth rotation, orientation in space, and Earth's gravity, gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properti ...

in the United States.

Since 1830, Hassler was also head of the Bureau of Weights and Measures which became a part of the Coast Survey. He compared various units of length used in the United States at that time and measured coefficients of expansion

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to change its shape, area, volume, and density in response to a change in temperature, usually not including phase transitions.

Temperature is a monotonic function of the average molecular kinetic ...

to assess temperature effects on the measurements.

In 1841, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, taking into account errors which had been recognized by Louis Puissant in the French meridian arc comprising the arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain which had been extended southward by François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of ...

and Jean-Baptiste Biot, recalculated the flattening

Flattening is a measure of the compression of a circle or sphere

A sphere () is a Geometry, geometrical object that is a solid geometry, three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the Locus (mathematics), set o ...

of the Earth ellipsoid making use of nine more arc measurements, namely Peruan, Prussian, first East-Indian, second East-Indian, English, Hannover, Danish, Russian and Swedish covering almost 50 degrees of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

, and stated that the Earth quadrant used for determining the length of the metre was nothing more than a rather imprecise conversion factor

Conversion of units is the conversion between different units of measurement for the same quantity, typically through multiplicative conversion factors which change the measured quantity value without changing its effects.

Overview

The process ...

between the toise and the metre.

Regarding the precision of the conversion from the toise to the metre, both units of measurement

A unit of measurement is a definite magnitude of a quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law, that is used as a standard for measurement of the same kind of quantity. Any other quantity of that kind can be expressed as a mul ...

were then defined by primary standards, and unique artifacts made of different alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductilit ...

s with distinct coefficients of expansion were the legal basis of units of length. A wrought iron ruler, the Toise of Peru, also called ''Toise de l'Académie'', was the French primary standard of the toise, and the metre was officially defined by the ''Mètre des Archives'' made of platinum. Besides the latter, another platinum and twelve iron standards of the metre were made in 1799. One of them became known as the ''Committee Meter'' in the United States and served as standard of length in the Coast Survey until 1890. According to geodesists, these standards were secondary standards deduced from the Toise of Peru. In Europe, surveyors continued to use measuring instruments calibrated on the Toise of Peru. Among these, the toise of Bessel and the apparatus of Borda were respectively the main references for geodesy in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

and in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

. A French scientific instrument maker, Jean Nicolas Fortin Jean Nicolas Fortin (1750–1831) was a French maker of scientific instruments, born on 9 August 1750 in Mouchy-la-Ville in Picardy. Among his customers were such noted scientists as Lavoisier, for whom he made a precision balance, Gay-Lussac, Fra ...

, had made two direct copies of the Toise of Peru, the first for Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve in 1821 and a second for Friedrich Bessel in 1823.

On the subject of the theoretical definition of the metre, it had been inaccessible and misleading at the time of Delambre and Mechain arc measurement, as the geoid is a ball, which on the whole can be assimilated to an oblate spheroid, but which in detail differs from it so as to prohibit any generalization and any extrapolation. As early as 1861, after Friedrich von Schubert showed that the different meridians were not of equal length, Elie Ritter, a mathematician from Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situ ...

, deduced from a computation based on eleven meridian arcs covering 86 degrees that the meridian equation differed from that of the ellipse: the meridian was swelled about the 45th degree of latitude by a layer whose thickness was difficult to estimate because of the uncertainty of the latitude of some stations, in particular that of Montjuïc in the French meridian arc. By measuring the latitude of two stations in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ...

, Méchain had found that the difference between these latitudes was greater than predicted by direct measurement of distance by triangulation. We know now that, in addition to other errors in the survey of Delambre and Méchain, an unfavourable vertical deflection gave an inaccurate determination of Barcelona's latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

, a metre "too short" compared to a more general definition taken from the average of a large number of arcs.

Nevertheless Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler's use of the metre in coastal survey contributed to the introduction of the Metric Act of 1866 allowing the use of the metre in the United States, and also played an important role in the choice of the metre as international scientific unit of length and the proposal by the European Arc Measurement (German: ''Europäische Gradmessung'') to “establish a European international bureau for weights and measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (french: Bureau international des poids et mesures, BIPM) is an intergovernmental organisation, through which its 59 member-states act together on measurement standards in four areas: chemistry ...

”. However, in 1866, the most important concern was that the Toise of Peru, the standard of the toise constructed in 1735 for the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator, might be so much damaged that comparison with it would be worthless, while Bessel had questioned the accuracy of copies of this standard belonging to Altona and Koenigsberg Observatories, which he had compared to each other about 1840. Indeed when the primary Imperial yard standard was partially destroyed in 1834, a new standard of reference had been constructed using copies of the "Standard Yard, 1760" instead of the pendulum's length as provided for in the Weights and Measures Act of 1824.

In 1864, Urbain Le Verrier refused to join the first general conference of the Central European Arc Measurement because the French geodetic works had to be verified.

In 1866, at the meeting of the Permanent Commission of the association in Neuchâtel, Antoine Yvon Villarceau announced that he had checked eight points of the French arc. He confirmed that the metre was too short. It then became urgent to undertake a complete revision of the meridian arc. Moreover, while the extension of the French meridian arc to the Balearic Islands (1803–1807) had seemed to confirm the length of the metre, this survey had not been secured by any baseline in Spain. For that reason, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero's announcement, at this conference, of his 1858 measurement of a baseline in Madridejos was of particular importance. Indeed surveyors determined the size of

In 1866, at the meeting of the Permanent Commission of the association in Neuchâtel, Antoine Yvon Villarceau announced that he had checked eight points of the French arc. He confirmed that the metre was too short. It then became urgent to undertake a complete revision of the meridian arc. Moreover, while the extension of the French meridian arc to the Balearic Islands (1803–1807) had seemed to confirm the length of the metre, this survey had not been secured by any baseline in Spain. For that reason, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero's announcement, at this conference, of his 1858 measurement of a baseline in Madridejos was of particular importance. Indeed surveyors determined the size of triangulation

In trigonometry and geometry, triangulation is the process of determining the location of a point by forming triangles to the point from known points.

Applications

In surveying

Specifically in surveying, triangulation involves only angle ...

networks by measuring baselines which concordance granted the accuracy of the whole survey.

In 1867 at the second general conference of the International Association of Geodesy held in Berlin, the question of an international standard unit of length was discussed in order to combine the measurements made in different countries to determine the size and shape of the Earth. The conference recommended the adoption of the metre in replacement of the toise and the creation of an international metre commission, according to the proposal of Johann Jacob Baeyer

Johann Jacob Baeyer (born 5 November 1794 in Berlin, died 10 September 1885 in Berlin) was a German geodesist and a lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many ...

, Adolphe Hirsch

Adolphe Hirsch (21 May 1830 - 16 April 1901) was a German born, Swiss astronomer and geodesist.

Bibliography

Adolph Hirsch was born in Halberstadt. He studied astronomy at the universities of Heidelberg and Vienna. He founded and directed the ...

and Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero who had devised two geodetic standards calibrated on the metre for the map of Spain.

Ibáñez adopted the system which Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler used for the United States Survey of the Coast, consisting of a single standard with lines marked on the bar and microscopic measurements. Regarding the two methods by which the effect of temperature was taken into account, Ibáñez used both the bimetallic rulers, in platinum and brass, which he first employed for the central baseline of Spain, and the simple iron ruler with inlaid mercury thermometers which was utilized in Switzerland. These devices, the first of which is referred to as either Brunner apparatus or Spanish Standard, were constructed in France by Jean Brunner, then his sons. Measurement traceability between the toise and the metre was ensured by comparison of the Spanish Standard with the standard devised by Borda and Lavoisier for the survey of the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is to ...

connecting Dunkirk with Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ...

.

Hassler's metrological and geodetic work also had a favourable response in Russia. In 1869, the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences sent to the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

a report drafted by Otto Wilhelm von Struve, Heinrich von Wild and Moritz von Jacobi inviting his French counterpart to undertake joint action to ensure the universal use of the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the definition of the Intern ...

in all scientific work.

In the 1870s and in light of modern precision, a series of international conferences was held to devise new metric standards. When a conflict broke out regarding the presence of impurities in the metre-alloy of 1874, a member of the Preparatory Committee since 1870 and Spanish representative at the Paris Conference in 1875, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero intervened with the

In the 1870s and in light of modern precision, a series of international conferences was held to devise new metric standards. When a conflict broke out regarding the presence of impurities in the metre-alloy of 1874, a member of the Preparatory Committee since 1870 and Spanish representative at the Paris Conference in 1875, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero intervened with the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

to rally France to the project to create an International Bureau of Weights and Measures equipped with the scientific means necessary to redefine the units of the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the definition of the Intern ...

according to the progress of sciences.

The Metre Convention (''Convention du Mètre'') of 1875 mandated the establishment of a permanent International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM: ') to be located in Sèvres, France. This new organisation was to construct and preserve a prototype metre bar, distribute national metric prototypes, and maintain comparisons between them and non-metric measurement standards. The organisation distributed such bars in 1889 at the first General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM: '), establishing the '' International Prototype Metre'' as the distance between two lines on a standard bar composed of an alloy of 90% platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

and 10% iridium, measured at the melting point of ice. National Institute of Standards and Technology 2003; Historical context of the SI: Unit of length (meter)

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated, the progress of metrology combined with those of gravimetry through improvement of Kater's pendulum led to a new era of

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated, the progress of metrology combined with those of gravimetry through improvement of Kater's pendulum led to a new era of geodesy

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), Earth rotation, orientation in space, and Earth's gravity, gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properti ...

. If precision metrology had needed the help of geodesy, the latter could not continue to prosper without the help of metrology. It was then necessary to define a single unit to express all the measurements of terrestrial arcs and all determinations of the force of gravity by the mean of pendulum. Metrology had to create a common unit, adopted and respected by all civilized nations.

Moreover, at that time, statistician

A statistician is a person who works with theoretical or applied statistics. The profession exists in both the private and public sectors.

It is common to combine statistical knowledge with expertise in other subjects, and statisticians may wor ...

s knew that scientific observations are marred by two distinct types of errors, constant errors on the one hand, and fortuitous errors, on the other hand. The effects of the latters can be mitigated by the least-squares method. Constant or regular errors on the contrary must be carefully avoided, because they arise from one or more causes that constantly act in the same way and have the effect of always altering the result of the experiment in the same direction. They therefore deprive of any value the observations that they impinge. However, the distinction between systematic and random errors is far from being as sharp as one might think at first assessment. In reality, there are no or very few random errors. As science progresses, the causes of certain errors are sought out, studied, their laws discovered. These errors pass from the class of random errors into that of systematic errors. The ability of the observer consists in discovering the greatest possible number of systematic errors in order to be able, once he has become acquainted with their laws, to free his results from them using a method or appropriate corrections.

For metrology the matter of expansibility was fundamental; as a matter of fact the temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied on ...

measuring error related to the length measurement in proportion to the expansibility of the standard and the constantly renewed efforts of metrologists to protect their measuring instruments against the interfering influence of temperature revealed clearly the importance they attached to the expansion-induced errors. It was thus crucial to compare at controlled temperatures with great precision and to the same unit all the standards for measuring geodetic baselines and all the pendulum rods. Only when this series of metrological comparisons would be finished with a probable error of a thousandth of a millimetre would geodesy be able to link the works of the different nations with one another, and then proclaim the result of the measurement of the Globe.

As the figure of the Earth

Figure of the Earth is a term of art in geodesy that refers to the size and shape used to model Earth. The size and shape it refers to depend on context, including the precision needed for the model. A sphere is a well-known historical approxima ...

could be inferred from variations of the seconds pendulum length with latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

, the United States Coast Survey instructed Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for ...

in the spring of 1875 to proceed to Europe for the purpose of making pendulum experiments to chief initial stations for operations of this sort, in order to bring the determinations of the forces of gravity in America into communication with those of other parts of the world; and also for the purpose of making a careful study of the methods of pursuing these researches in the different countries of Europe. In 1886 the association of geodesy changed name for the International Geodetic Association, which Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero presided up to his death in 1891. During this period the International Geodetic Association (German: ''Internationale Erdmessung'') gained worldwide importance with the joining of United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

, Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

and Japan.

Efforts to supplement the various national surveying systems, which began in the 19th century with the foundation of the '' Mitteleuropäische Gradmessung'', resulted in a series of global ellipsoids of the Earth (e.g., Helmert 1906, Hayford 1910 and 1924) which would later lead to develop the

Efforts to supplement the various national surveying systems, which began in the 19th century with the foundation of the '' Mitteleuropäische Gradmessung'', resulted in a series of global ellipsoids of the Earth (e.g., Helmert 1906, Hayford 1910 and 1924) which would later lead to develop the World Geodetic System

The World Geodetic System (WGS) is a standard used in cartography, geodesy, and satellite navigation including GPS. The current version, WGS 84, defines an Earth-centered, Earth-fixed coordinate system and a geodetic datum, and also describ ...

. Nowadays the practical realisation of the metre is possible everywhere thanks to the atomic clock

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions betw ...

s embedded in GPS satellites.

Wavelength definition

In 1873,James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

suggested that light emitted by an element be used as the standard both for the metre and for the second. These two quantities could then be used to define the unit of mass.

In 1893, the standard metre was first measured with an interferometer by Albert A. Michelson, the inventor of the device and an advocate of using some particular wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

of light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 te ...

as a standard of length. By 1925, interferometry was in regular use at the BIPM. However, the International Prototype Metre remained the standard until 1960, when the eleventh CGPM defined the metre in the new International System of Units (SI) as equal to wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

s of the orange- red emission line in the electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging from ...

of the krypton-86 atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas ...

in a vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often di ...

.

Speed of light definition

To further reduce uncertainty, the 17th CGPM in 1983 replaced the definition of the metre with its current definition, thus fixing the length of the metre in terms of the second and the speed of light: ::The metre is the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of of a second. This definition fixed the speed of light invacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often di ...

at exactly metres per second (≈ or ≈1.079 billion km/hour). An intended by-product of the 17th CGPM's definition was that it enabled scientists to compare lasers accurately using frequency, resulting in wavelengths with one-fifth the uncertainty involved in the direct comparison of wavelengths, because interferometer errors were eliminated. To further facilitate reproducibility from lab to lab, the 17th CGPM also made the iodine-stabilised helium–neon laser "a recommended radiation" for realising the metre. For the purpose of delineating the metre, the BIPM currently considers the HeNe laser wavelength, , to be with an estimated relative standard uncertainty (''U'') of .The term "relative standard uncertainty" is explained by NIST on their web site: This uncertainty is currently one limiting factor in laboratory realisations of the metre, and it is several orders of magnitude poorer than that of the second, based upon the caesium fountain atomic clock

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions betw ...

(). Consequently, a realisation of the metre is usually delineated (not defined) today in labs as wavelengths of helium-neon laser light in a vacuum, the error stated being only that of frequency determination. This bracket notation expressing the error is explained in the article on measurement uncertainty.

Practical realisation of the metre is subject to uncertainties in characterising the medium, to various uncertainties of interferometry, and to uncertainties in measuring the frequency of the source. A commonly used medium is air, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into Outline of p ...

(NIST) has set up an online calculator to convert wavelengths in vacuum to wavelengths in air.The formulas used in the calculator and the documentation behind them are found at The choice is offered to use either thmodified Edlén equation

or th

Ciddor equation

The documentation provide

a discussion of how to choose

between the two possibilities. As described by NIST, in air, the uncertainties in characterising the medium are dominated by errors in measuring temperature and pressure. Errors in the theoretical formulas used are secondary. By implementing a refractive index correction such as this, an approximate realisation of the metre can be implemented in air, for example, using the formulation of the metre as wavelengths of helium–neon laser light in a vacuum, and converting the wavelengths in a vacuum to wavelengths in air. Air is only one possible medium to use in a realisation of the metre, and any partial vacuum can be used, or some inert atmosphere like helium gas, provided the appropriate corrections for refractive index are implemented. The metre is ''defined'' as the path length travelled by light in a given time, and practical laboratory length measurements in metres are determined by counting the number of wavelengths of laser light of one of the standard types that fit into the length, and converting the selected unit of wavelength to metres. Three major factors limit the accuracy attainable with laser interferometers for a length measurement: A more detailed listing of errors can be found in Zagar, 1999, pp. 6–65''ff''. * uncertainty in vacuum wavelength of the source, * uncertainty in the refractive index of the medium, * least count resolution of the interferometer. Of these, the last is peculiar to the interferometer itself. The conversion of a length in wavelengths to a length in metres is based upon the relation : which converts the unit of wavelength ''λ'' to metres using ''c'', the speed of light in vacuum in m/s. Here ''n'' is the refractive index of the medium in which the measurement is made, and ''f'' is the measured frequency of the source. Although conversion from wavelengths to metres introduces an additional error in the overall length due to measurement error in determining the refractive index and the frequency, the measurement of frequency is one of the most accurate measurements available. The CIPM issued a clarification in 2002:

Timeline

Early adoptions of the metre internationally

In France, the metre was adopted as an exclusive measure in 1801 under the Consulate. This continued under theFirst French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental ...

until 1812, when Napoleon decreed the introduction of the non-decimal '' mesures usuelles'', which remained in use in France up to 1840 in the reign of Louis Philippe

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary Wa ...

. Meanwhile, the metre was adopted by the Republic of Geneva. After the joining of the canton of Geneva

The Canton of Geneva, officially the Republic and Canton of Geneva (french: link=no, République et canton de Genève; frp, Rèpublica et canton de Geneva; german: Republik und Kanton Genf; it, Repubblica e Cantone di Ginevra; rm, Republica e ...

to Switzerland in 1815, Guillaume Henri Dufour published the first official Swiss map, for which the metre was adopted as the unit of length. Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, a Swiss–French binational officer, was present when a baseline was measured near Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich () i ...

for the Dufour map, which would win the gold medal for a national map at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Among the scientific instruments calibrated on the metre that were displayed at the Exposition Universelle, was Brunner's apparatus, a geodetic instrument devised for measuring the central baseline of Spain, whose designer, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero would represent Spain at the International Statistical Institute. In 1885, in addition to the Exposition Universelle and the second Statistical Congress held in Paris, an International Association for Obtaining a Uniform Decimal System of Measures, Weights, and Coins was created there. Copies of the Spanish standard were made for Egypt, France and Germany. These standards were compared to each other and with the Borda apparatus, which was the main reference for measuring all geodetic bases in France. In 1869, Napoleon III convened the International Metre Commission, which was to meet in Paris in 1870. The Franco-Prussian War broke out, the Second French Empire collapsed, but the metre survived.

Metre adoption dates by country

*France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

: 1801 - 1812, then 1840,

* Republic of Geneva, Switzerland: 1813,

* Kingdom of the Netherlands

, national_anthem = )

, image_map = Kingdom of the Netherlands (orthographic projection).svg

, map_width = 250px

, image_map2 = File:KonDerNed-10-10-10.png

, map_caption2 = Map of the four constituent countries shown to scale

, capital = ...

: 1820,

* Kingdom of Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

: 1830,

* Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

: 1848,

* Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

, Italy: 1850,

* Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

: 1852,

* Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

: 1852,

* Colombia: 1853,

* Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar language, Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechuan ...

: 1856,

* Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

: 1857,

* Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

: 1862,

* Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

: 1863,

* Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

: 1863,

* German Empire, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

: 1872,

* Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, 1875,

* Switzerland: 1877.

SI prefixed forms of metre

SI prefixes can be used to denote decimal multiples and submultiples of the metre, as shown in the table below. Long distances are usually expressed in km,astronomical unit

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbi ...

s (149.6 Gm), light-years (10 Pm), or parsecs (31 Pm), rather than in Mm, Gm, Tm, Pm, Em, Zm or Ym; "30 cm", "30 m", and "300 m" are more common than "3 dm", "3 dam", and "3 hm", respectively.

The terms ''micron'' and ''millimicron'' can be used instead of ''micrometre'' (μm) and ''nanometre'' (nm), but this practice may be discouraged.

Equivalents in other units

Within this table, "inch" and "yard" mean "international inch" and "international yard" respectively, though approximate conversions in the left column hold for both international and survey units. : "≈" means "is approximately equal to"; : "=" means "is exactly equal to". One metre is exactly equivalent to inches and to yards. A simplemnemonic

A mnemonic ( ) device, or memory device, is any learning technique that aids information retention or retrieval (remembering) in the human memory for better understanding.

Mnemonics make use of elaborative encoding, retrieval cues, and image ...

aid exists to assist with conversion, as three "3"s:

: 1 metre is nearly equivalent to 3 feet inches. This gives an overestimate of 0.125mm; however, the practice of memorising such conversion formulas has been discouraged in favour of practice and visualisation of metric units.

The ancient Egyptian cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding ...

was about 0.5m (surviving rods are 523–529mm). Scottish and English definitions of the ell

An ell (from Proto-Germanic *''alinō'', cognate with Latin ''ulna'') is a northwestern European unit of measurement, originally understood as a cubit (the combined length of the forearm and extended hand). The word literally means "arm", and ...

(two cubits) were 941mm (0.941m) and 1143mm (1.143m) respectively. The ancient Parisian ''toise'' (fathom) was slightly shorter than 2m and was standardised at exactly 2m in the mesures usuelles system, such that 1m was exactly toise. The Russian verst was 1.0668km. The Swedish mil was 10.688km, but was changed to 10km when Sweden converted to metric units.

See also

* Conversion of units for comparisons with other units * International System of Units *ISO 1

ISO 1 is an international standard set by the International Organization for Standardization that specifies the standard reference temperature for geometrical product specification and verification. The temperature is fixed at 20 °C, which is ...

standard reference temperature for length measurements

* Length measurement

* Metre Convention

* Metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the definition of the Intern ...

* Metric prefix

A metric prefix is a unit prefix that precedes a basic unit of measure to indicate a multiple or submultiple of the unit. All metric prefixes used today are decadic. Each prefix has a unique symbol that is prepended to any unit symbol. The pr ...

* Metrication

* Orders of magnitude (length)

* SI prefix

* Speed of light

* Vertical metre

Notes

References

* * Astin, A. V. & Karo, H. Arnold, (1959)''Refinement of values for the yard and the pound''

Washington DC: National Bureau of Standards, republished on National Geodetic Survey web site and the Federal Register (Doc. 59-5442, Filed, 30 June 1959) * * * * * *

Retrieved 26 May 2010. * National Institute of Standards and Technology. (27 June 2011).

NIST-F1 Cesium Fountain Atomic Clock

'. Author. * National Physical Laboratory. (25 March 2010).

Iodine-Stabilised Lasers

'. Author. * * Republic of the Philippines. (2 December 1978).

'. Author. * Republic of the Philippines. (10 October 1991). '' ttps://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/1991/10oct/19911010-RA-7160-CCA.pdf Republic Act No. 7160: The Local Government Code of the Philippines'. Author. * Supreme Court of the Philippines (Second Division). (20 January 2010).

G.R. No. 185240

'. Author. * Taylor, B.N. and Thompson, A. (Eds.). (2008a)

''The International System of Units (SI)''

United States version of the English text of the eighth edition (2006) of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures publication ''Le Système International d’ Unités (SI)'' (Special Publication 330). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 18 August 2008. * Taylor, B.N. and Thompson, A. (2008b)

''Guide for the Use of the International System of Units''

(Special Publication 811). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 23 August 2008. * Turner, J. (Deputy Director of the National Institute of Standards and Technology). (16 May 2008

"Interpretation of the International System of Units (the Metric System of Measurement) for the United States"

''Federal Register'' Vol. 73, No. 96, p.28432-3. * Zagar, B.G. (1999)

Laser interferometer displacement sensors

in J.G. Webster (ed.). ''The Measurement, Instrumentation, and Sensors Handbook.'' CRC Press. . {{Authority control SI base units