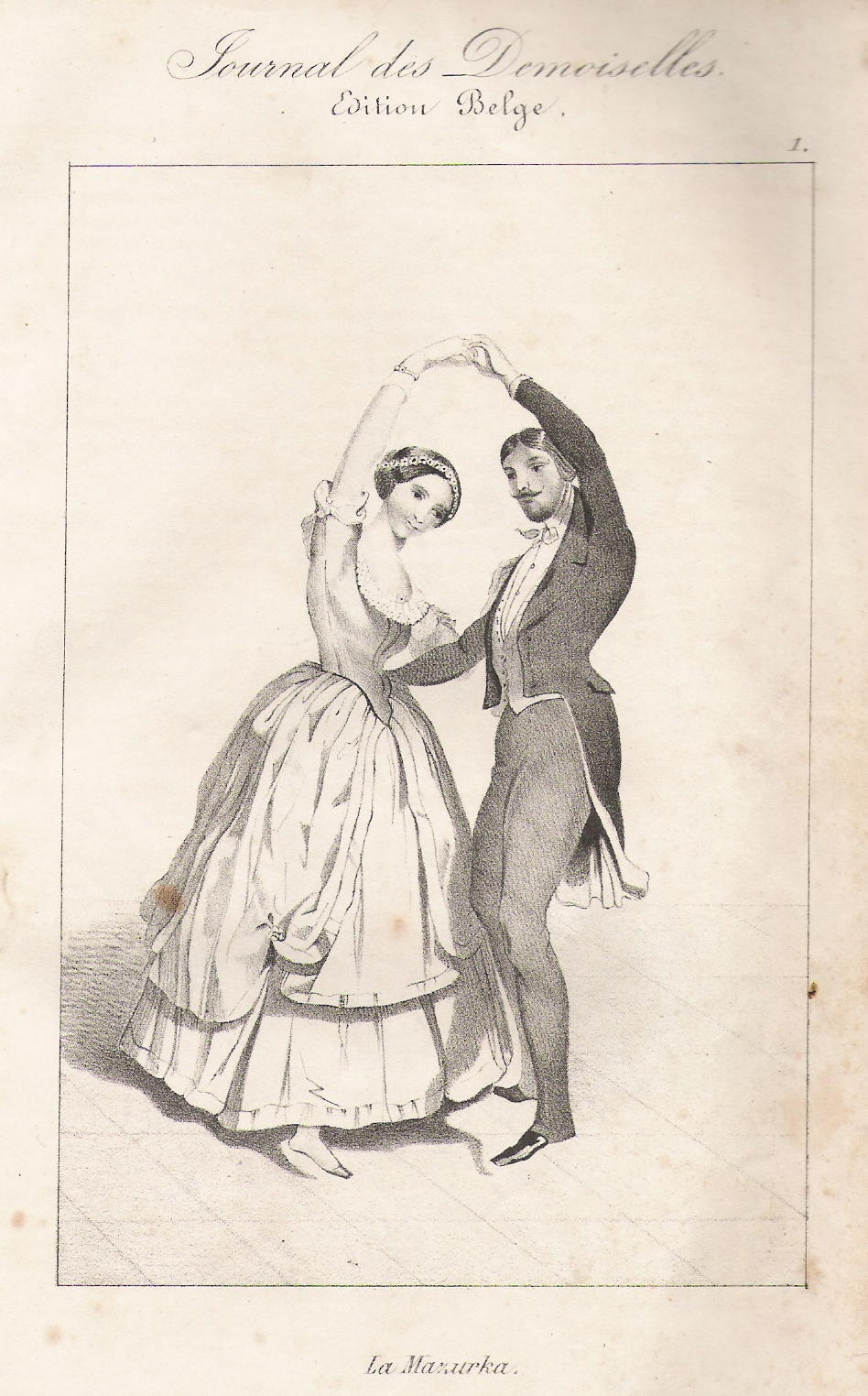

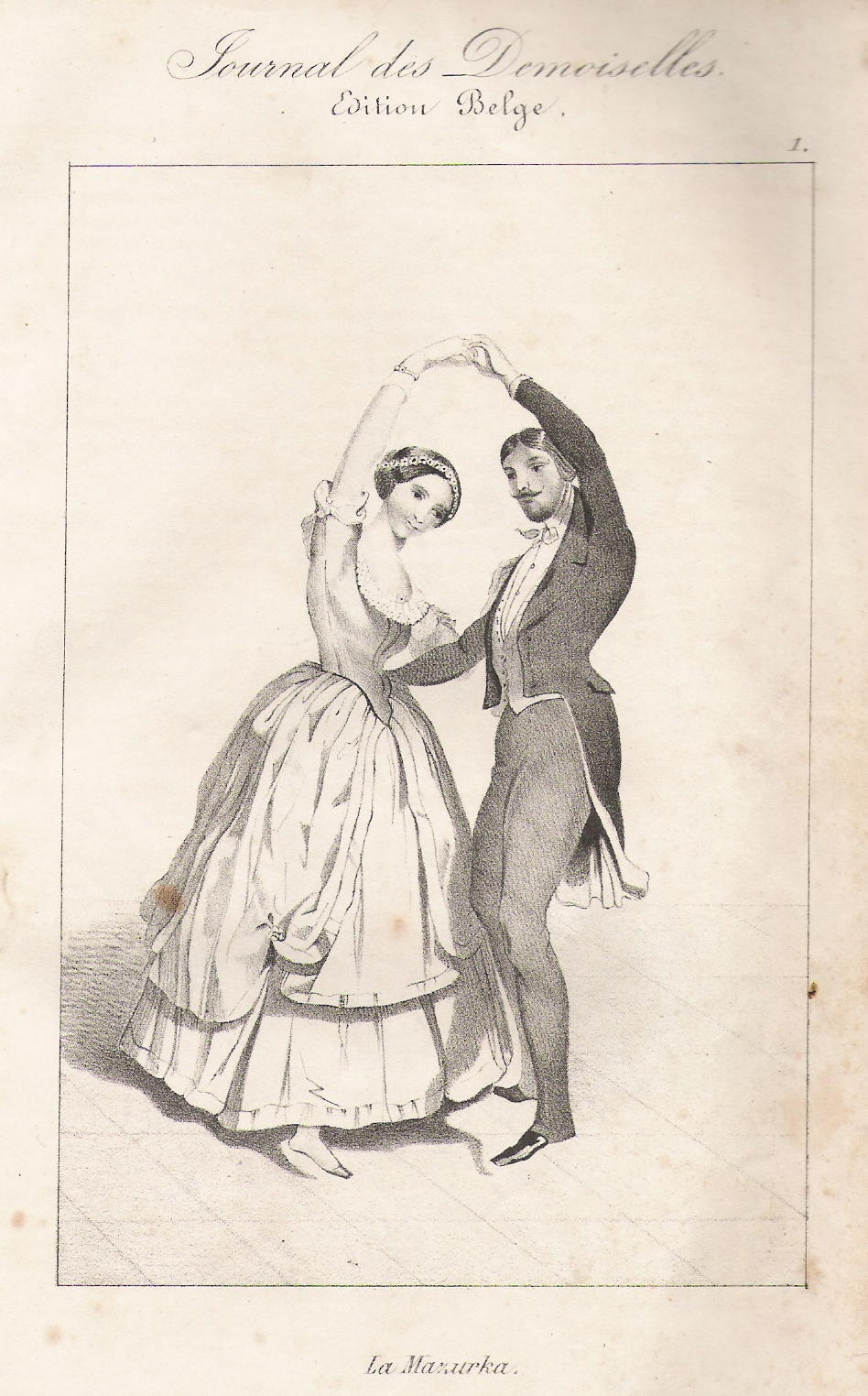

Mazurka Project on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mazurka (

Several classical composers have written mazurkas, with the best known being the 59 composed by

Several classical composers have written mazurkas, with the best known being the 59 composed by

Mazurka

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 17 November 2009. * Kallberg, Jeffrey. "The problem of repetition and return in Chopin's mazurkas." Chopin Styles, ed. Jim Samson. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1988. * Kallberg, Jeffrey. "Chopin's Last Style." Journal of the American Musicological Society 38.2 (1985): 264–315. * Michałowski, Kornel, and Jim Samson.

Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 17 November 2009. (esp. section 6, "Formative Influences") * Milewski, Barbara. "Chopin's Mazurkas and the Myth of the Folk." 19th-Century Music 23.2 (1999): 113–35. * Rosen, Charles. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995. * Winokur, Roselyn M. "Chopin and the Mazurka". Diss. Sarah Lawrence College, 1974.

history, description, costumes, music, sources

Mazurka within traditional dances of the County of Nice (France)

The Mazurka Project

*

'Vincent Campbell's Mazurka' as played by Vincent Campbell in Co. Donegal

{{Authority control Mazurka, Dance forms in classical music Irish dances Music of Ireland Polish dances Triple time dances Culture of Masovian Voivodeship

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

: ''mazurek'') is a Polish musical form based on stylised folk dance

A folk dance is a dance that reflects the life of the people of a certain country or region. Not all ethnic dances are folk dances. For example, Ritual, ritual dances or dances of ritual origin are not considered to be folk dances. Ritual dances ...

s in triple meter

Triple is used in several contexts to mean "threefold" or a " treble":

Sports

* Triple (baseball), a three-base hit

* A basketball three-point field goal

* A figure skating jump with three rotations

* In bowling terms, three strikes in a row

...

, usually at a lively tempo, with character defined mostly by the prominent mazur's "strong accents unsystematically placed on the second or third beat

Beat, beats, or beating may refer to:

Common uses

* Assault, inflicting physical harm or unwanted physical contact

* Battery (crime), a criminal offense involving unlawful physical contact

* Battery (tort), a civil wrong in common law of inte ...

". The Mazurka, alongside the polka

Polka is a dance style and genre of dance music in originating in nineteenth-century Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. Though generally associated with Czech and Central European culture, polka is popular throughout Europe and the ...

dance, became popular at the ballroom

A ballroom or ballhall is a large room inside a building, the primary purpose of which is holding large formal parties called ''balls''. Traditionally, most balls were held in private residences; many mansions and palaces, especially histori ...

s and salons of Europe in the 19th century, particularly through the notable works by Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period who wrote primarily for Piano solo, solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown ...

. The mazurka (in Polish ''mazur'', the same word as the mazur) and mazurek (rural dance based on the mazur) are often confused in Western literature as the same musical form.

History

The folk origins of the ''Mazurk'' are three Polish folk dances which are: * '' mazur'', most characteristic due to its inconsistent rhythmic accents, * slow and melancholic ''kujawiak

The kujawiak is a Polish folk dance from the region of Kuyavia (Kujawy) in central Poland.Don Michael Randel. ''The Harvard Dictionary of Music''. Harvard University Press. 2003. p. 449. It is one of the five national dances of Poland, the other ...

'',

* fast ''oberek

The oberek, also known as obertas or ober, is a lively Polish dance in triple metre. Its name is derived from the Polish ''obracać się'', meaning "to spin". It consists of many dance lifts and jumps. It is performed at a much quicker pace than t ...

''.

The ''mazurka'' is always found to have either a triplet, trill, dotted eighth note (quaver) pair, or an ordinary eighth note pair before two quarter note

A quarter note ( AmE) or crotchet ( BrE) () is a musical note played for one quarter of the duration of a whole note (or semibreve). Quarter notes are notated with a filled-in oval note head and a straight, flagless stem. The stem usually ...

s (crotchets). In the 19th century, the form became popular in many ballroom

A ballroom or ballhall is a large room inside a building, the primary purpose of which is holding large formal parties called ''balls''. Traditionally, most balls were held in private residences; many mansions and palaces, especially histori ...

s in different parts of Europe.

"Mazurka" is a Polish word, it means a Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( ) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the largest city and Płock being the capital of the region . Throughout the ...

n woman or girl. It is a feminine

Femininity (also called womanliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and Gender roles, roles generally associated with women and girls. Femininity can be understood as Social construction of gender, socially constructed, and there is also s ...

form of the word "Mazur", which — until the nineteenth century — denoted an inhabitant of Poland's Mazovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( ) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the largest city and Płock being the capital of the region . Throughout the ...

region (Masovians

Masovians, also spelled as Mazovians, and historically known as Masurians, is an ethnographic group of Polish people that originates from the region of Masovia, located mostly within borders of the Masovian Voivodeship, Poland. They speak the ...

, formerly plural: ''Mazurzy''). The similar word "Mazurek" is a diminutive

A diminutive is a word obtained by modifying a root word to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment, and sometimes to belittle s ...

and masculine

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some beh ...

form of "Mazur". In relation to dance, all these words (''mazur, mazurek, mazurka'') mean "a Mazovian dance". Apart from the ethnic name, the word ''mazurek'' refers to various terms in Polish, e.g. a cake

Cake is a flour confection usually made from flour, sugar, and other ingredients and is usually baked. In their oldest forms, cakes were modifications of bread, but cakes now cover a wide range of preparations that can be simple or elabor ...

, a bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

and a popular surname.

''Mazurek'' is also a rural dance identified by some as the ''oberek''. It is said ''oberek'' is a danced variation of the sung ''mazurek'', the latter also having more prominent accents on second and third beats and less fluent of a rhythmical flow, which is so characteristical of ''oberek.''

Several classical composers have written mazurkas, with the best known being the 59 composed by

Several classical composers have written mazurkas, with the best known being the 59 composed by Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period who wrote primarily for Piano solo, solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown ...

for solo piano. In 1825, Maria Szymanowska

Maria Szymanowska (Polish pronunciation: ; born Marianna Agata Wołowska; Warsaw, 14 December 1789 – 25 July 1831, St. Petersburg, Russia) was a Polish composer and one of the first professional virtuoso pianists of the 19th century. She tour ...

wrote the largest collection of piano mazurkas published before Chopin. Henryk Wieniawski

Henryk Wieniawski (; 10 July 183531 March 1880) was a Polish virtuoso violinist, composer, and pedagogue, who is regarded amongst the most distinguished violinists in history. His younger brother Józef Wieniawski and nephew :pl:Adam Tadeusz Wien ...

also wrote two for violin with piano (the popular "Obertas", Op. 19), Julian Cochran

200px, Julian Cochran in 1998

Julian Cochran (born 1974) is an English-born Australian composer.

Cochran's earlier works show stylistic influences from Impressionist music and his later works are more noticeably influenced by Classical music a ...

composed a collection of five mazurkas for solo piano and orchestra, and in the 1920s, Karol Szymanowski

Karol Maciej Szymanowski (; 3 October 188229 March 1937) was a Polish composer and pianist. He was a member of the modernism (music), modernist Young Poland movement that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Szymanowski's early w ...

wrote a set of twenty for piano and finished his composing career with a final pair in 1934. Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, scientific transliteration: ''Aleksandr Nikolaevič Skrjabin''; also transliterated variously as Skriabin, Skryabin, and (in French) Scriabine. The composer himselused the French spelling "Scriabine" which was a ...

, who was at first conscious of being Chopin's follower, wrote 24 mazurkas.

Chopin first started composing mazurkas in 1824, reaching full maturity by 1830, the year of the November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31) (), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in Russian Partition, the heartland of Partitions of Poland, partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. ...

, a rebellion in Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

against Russia. Chopin continued composing them until 1849, the year of his death. The stylistic and musical characteristics of his mazurkas differ from the traditional variety because Chopin in effect created a more complex type of mazurka, using classical techniques, including counterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

and fugue

In classical music, a fugue (, from Latin ''fuga'', meaning "flight" or "escape""Fugue, ''n''." ''The Concise Oxford English Dictionary'', eleventh edition, revised, ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford and New York: Oxford Universit ...

. By including more chromaticism and harmony in the mazurkas, he made them more technically interesting than the traditional dances. Chopin also tried to compose his mazurkas in such a way that they could not be used for dancing, so as to distance them from the original form.

However, while Chopin changed some aspects of the original mazurka, he maintained others. His mazurkas, like the traditional dances, contain a great deal of repetition: repetition of certain measures or groups of measures; of entire sections; and of an initial theme. The rhythm of his mazurkas also remains very similar to that of earlier mazurkas. However, Chopin also incorporated the rhythmic elements of the two other Polish forms mentioned above, the ''kujawiak'' and ''oberek''; his mazurkas usually feature rhythms from more than one of these three forms (''mazurek'', ''kujawiak'', and ''oberek''). This use of rhythm suggests that Chopin tried to create a genre that had ties to the original form, but was still something new and different.

The mazurka began as a dance for either four or eight couples. Eventually, Michel Fokine

Michael Fokine ( – 22 August 1942) was a Russian choreographer and dancer.

Career Early years

Fokine was born in Saint Petersburg to a prosperous merchant and at the age of 9 was accepted into the Saint Petersburg Imperial Ballet Sch ...

created a female solo mazurka dance dominated by flying '' grandes jetés'', alternating second and third arabesque positions, and split-leg climactic postures.

Outside Poland

The form was common as a popular dance in Europe and the United States in the mid to late nineteenth century.Cape Verde Islands

InCape Verde

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

the mazurka is also revered as an important cultural phenomenon played with acoustic bands led by a violinist and accompanied by guitarists.

It also takes a variation of the mazurka dance form and is found mostly in the north of the archipelago, mainly in São Nicolau, Santo Antão. In the south it finds popularity in the island of Brava.

Czechia

Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

composers Bedřich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana ( ; ; 2 March 1824 – 12 May 1884) was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style that became closely identified with his people's aspirations to a cultural and political "revival". He has been regarded ...

, Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák ( ; ; 8September 18411May 1904) was a Czech composer. He frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia, following the Romantic-era nationalist example of his predec ...

, and Bohuslav Martinů

Bohuslav Jan Martinů (; December 8, 1890 – August 28, 1959) was a Czech composer of modern classical music. He wrote 6 symphony, symphonies, 15 operas, 14 ballet scores and a large body of orchestral, chamber music, chamber, vocal and ins ...

all wrote mazurkas to at least some extent. For Smetana and Martinů, these are single pieces (respectively, a Mazurka-Cappricio for piano and a Mazurka-Nocturne for a mixed string/wind quartet), whereas Dvořák composed a set of six mazurkas for piano, and a mazurka for violin and orchestra.

France

In France,Impressionistic

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

composers Claude Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

and Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism in music, Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composer ...

both wrote mazurkas; Debussy's is a stand-alone piece, and Ravel's is part of a suite of an early work, ''La Parade''. Jacques Offenbach

Jacques Offenbach (; 20 June 18195 October 1880) was a German-born French composer, cellist and impresario. He is remembered for his nearly 100 operettas of the 1850s to the 1870s, and his uncompleted opera ''The Tales of Hoffmann''. He was a p ...

included a mazurka in his ballet ''Gaîté Parisienne

''Gaîté Parisienne'' () is a 1938 ballet choreographed by Léonide Massine (1896–1979) to music by Jacques Offenbach (1819–1880) arranged and orchestrated many decades later by Manuel Rosenthal (1904–2003) in collaboration with Jacques B ...

''; Léo Delibes

Clément Philibert Léo Delibes (; 21 February 1836 – 16 January 1891) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer, best known for his ballets and French opera, operas. His works include the ballets ''Coppélia'' (1870) and ''Sylvia (b ...

composed one which appears several times in the first act of his ballet ''Coppélia

''Coppélia'' (sometimes subtitled: ''La Fille aux Yeux d'Émail'' (The Girl with the Enamel Eyes)) is a comic ballet from 1870 originally choreographed by Arthur Saint-Léon to the music of Léo Delibes, with libretto by Charles-Louis-Éti ...

''. The mazurka appears frequently in French traditional folk music. In the French Antilles

The French West Indies or French Antilles (, ; ) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two Overseas department and region of France, overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, including the islands of Bass ...

, the mazurka has become an important style of dance and music.

A creolised version of the mazurka is ''mazouk'' which—beginning around 1979 in Paris—morphed into the globally popular dance style “zouk

Zouk is a musical movement and dance pioneered by the French Antillean band Kassav' in the early 1980s. It was originally characterized by a fast tempo (120–145 bpm), a percussion-driven rhythm, and a loud horn section. Musicians from Mart ...

” developed in France and popularised by Paris's Island-creole supergroup Kassav'

Kassav', also alternatively spelled Kassav, is a French Caribbean band that originated from Guadeloupe in 1979. The band's musical style is rooted in the Guadeloupean gwoka rhythm, as well as the Martinican tibwa and Mendé rhythms. Regarded ...

; ''mazouk'' had been introduced to the French Caribbean in the late 1800s. In the 21st century in Brazil and the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, ''zouk'' (and its progenitor band Kassav') remains very popular. In popular 20th century folk dancing in France, the Polish/classical-piano (see Chopin) ''mazurka'' evolved into ''mazouk'', a dance at a more gentle pace (without the traditional 'hop' step on the 3rd beat), fostering more-intimate dancing and associating mazouk with a "seduction" dance (see also tango

Tango is a partner dance and social dance that originated in the 1880s along the Río de la Plata, the natural border between Argentina and Uruguay. The tango was born in the impoverished port areas of these countries from a combination of Arge ...

from Argentina). This "sexy" style of mazurka has also been imported to “balfolk

Balfolk (from French: , meaning a folk ball) is a dance event for folk dance and folk music in a number of European countries, mainly in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy and Poland. It is also known as ''folk bal' ...

" dancing in Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

and the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, hence the name "Belgian Mazurka" or "Flemish Mazurka". Perhaps the most enduring style of intimate dancing music of this origin moved ''zouk'' from the 1980s–2000s into its wildly popular (especially in Brazil and Africa) slow-dancing variant called ''zouk love'', which remains a staple of French-Caribbean dance venues in Paris and elsewhere.

Ireland

Mazurkas constitute a distinctive part of the traditional dance music ofCounty Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

, Ireland. As a couple's dance, it is no longer popular. The Polish dance entered Ireland in the 1840s, but is not widely played outside of Donegal. Unlike the Polish mazurek, which may have an accent on the second or third beat of a bar, the Irish mazurka (''masúrca'' in the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

) is consistently accented on the second beat, giving it a unique feel. Musician Caoimhín Mac Aoidh has written a book on the subject, ''From Mazovia to Meenbanad: The Donegal Mazurkas'', in which the history of the musical and dance form is related. Mac Aoidh tracked down 32 different mazurkas as played in Ireland.

Italy

Mazurkas are part of Italian popular music including theLiscio

Liscio or ballo liscio ("smooth" or "smooth dance" respectively in Italian) is a genre of music originating in the 19th century in the northern Italian region of Romagna under the influence of Viennese ballroom dances including the mazurka, waltz ...

style. Typical of Italian mazurkas are groups of triplets, strong dotted rhythms, and phrase endings of two accented quarter notes and a rest, unlike a waltz.

Brazil

InBrazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, the composer Ernesto Nazareth

Ernesto Júlio de Nazareth (March 20, 1863 – February 1, 1934) was a Brazilian composer and pianist, especially noted for his creative maxixe and choro compositions. Influenced by a diverse set of dance rhythms including the polka, the habanera ...

wrote a Chopinesque mazurka called "Mercedes" in 1917. Heitor Villa-Lobos

Heitor Villa-Lobos (March 5, 1887November 17, 1959) was a Brazilian composer, conductor, cellist, and classical guitarist described as "the single most significant creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music". Villa-Lobos has globally bec ...

wrote a mazurka for classical guitar in a similar musical style to Polish mazurkas.

Cuba

InCuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, composer Ernesto Lecuona

Ernesto Lecuona y Casado (; August 7, 1895 – November 29, 1963) was a Cuban composer and pianist, many of whose works have become standards of the Latin, jazz and classical repertoires. His over 600 compositions include songs and zarzuelas as ...

wrote a piece titled ''Mazurka en Glisado'' for the piano, one of various commissions throughout his life.

Nicaragua

InNicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

, Carlos Mejía Godoy y los de Palacaguina

Carlos may refer to:

Places

;Canada

* Carlos, Alberta, a locality

;United States

* Carlos, Indiana, an unincorporated community

* Carlos, Maryland, a place in Allegany County

* Carlos, Minnesota, a small city

* Carlos, West Virginia

;Elsewhere ...

and Los Soñadores de Saraguasca made a compilation of mazurkas from popular folk music, which are performed with a violin de talalate, an indigenous instrument from Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

.

Curaçao

InCuraçao

Curaçao, officially the Country of Curaçao, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located in the southern Caribbean Sea (specifically the Dutch Caribbean region), about north of Venezuela.

Curaçao includ ...

the mazurka was popular as dance music in the nineteenth century, as well as in the first half of the twentieth century. Several Curaçao-born composers, such as Jan Gerard Palm

Jan Gerard Palm (June 2, 1831 – December 13, 1906) was a composer from Curaçao.

Biography

Palm was born in Curaçao and directed several music ensembles at a young age. In 1859, he was appointed as music director of the Citizen's Guard Orchest ...

, Joseph Sickman Corsen, Jacobo Palm

Jacobo Palm (28 November 1887 – 1 July 1982) was a Curaçao-born composer.

Biography

Jacobo José Maria Palm was the grandson of Jan Gerard Palm (1831-1906) who is often referred to as the "father of Curaçao classical music". At the age of sev ...

, Rudolph Palm

Rudolf Palm (11 January 1880 in Curaçao – 11 September 1950 in Curaçao) was a Curaçao born composer.

Biography

Rudolf Theodorus Palm was the grandson of Jan Gerard Palm (1831–1906) who is often referred to as the "father of Curaçao clas ...

and Wim Statius Muller

Wim Statius Muller (Curaçao, 26 January 1930 – Curaçao, 1 September 2019) was a Curaçaoan composer and pianist, nicknamed "Curaçao's Chopin" for his romantic piano style of composition.Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, composers Ricardo Castro

Ricardo Castro Herrera (Rafael de la Santísima Trinidad Castro Herrera) (7 February 1864 – 27 November 1907) was a Mexican concert pianist and composer, considered the last romantic of the time of Porfirio Díaz.

Life

Castro was bor ...

and Manuel M Ponce wrote mazurkas for the piano in a Chopin fashion, eventually mixing elements of Mexican folk dances.

Philippines

In thePhilippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, the mazurka is a popular form of traditional dance

A folk dance is a dance that reflects the life of the people of a certain country or region. Not all ethnic dances are folk dances. For example, ritual dances or dances of ritual origin are not considered to be folk dances. Ritual dances are us ...

. The Mazurka Boholana is one well-known Filipino mazurka.

Portugal

In Portugal the mazurka became one of the most popular traditional European dances through the first years of the annual Andanças, a traditional dances festival held nearbyCastelo de Vide

Castelo de Vide () is a municipality in Portugal, with a population of 3,407 inhabitants in 2011, in an area of .

History

It is unclear when humans settled Castelo de Vide, although archaeologists suggest the decision came from the morphology of ...

.

Russia

In Russia, many composers wrote mazurkas for solo piano:Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, scientific transliteration: ''Aleksandr Nikolaevič Skrjabin''; also transliterated variously as Skriabin, Skryabin, and (in French) Scriabine. The composer himselused the French spelling "Scriabine" which was a ...

(26), Balakirev (7), Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer during the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular ...

(6). Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (12 November 183327 February 1887) was a Russian Romantic composer and chemist of Georgian–Russian parentage. He was one of the prominent 19th-century composers known as " The Five", a group dedicated to prod ...

wrote two in his '' Petite Suite'' for piano; Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, links=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka, mʲɪxɐˈil ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognit ...

also wrote two, although one is a simplified version of Chopin's Mazurka No. 13. Tchaikovsky also included mazurkas in his scores for ''Swan Lake

''Swan Lake'' ( rus, Лебеди́ное о́зеро, r=Lebedínoje ózero, p=lʲɪbʲɪˈdʲinəjə ˈozʲɪrə, links=no ), Op. 20, is a ballet composed by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1875–76. Despite its initial failu ...

'', ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

'', and ''Sleeping Beauty

"Sleeping Beauty" (, or ''The Beauty Sleeping in the Wood''; , or ''Little Briar Rose''), also titled in English as ''The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods'', is a fairy tale about a princess curse, cursed by an evil fairy to suspended animation in fi ...

''. Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

's Morceaux de salon Op. 10 includes a Mazurka in D-flat major as its 7th piece. Prokofiev wrote a Mazurka for orchestra in his ballet Cinderella, which is also included in his Cinderella Suite No. 1.

The mazurka was a common dance at the balls of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

and it is depicted in many Russian novels and films. In addition to its mention in Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

's ''Anna Karenina

''Anna Karenina'' ( rus, Анна Каренина, p=ˈanːə kɐˈrʲenʲɪnə) is a novel by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy, first published in book form in 1878. Tolstoy called it his first true novel. It was initially released in serial in ...

'' as well as in a protracted episode in ''War and Peace

''War and Peace'' (; pre-reform Russian: ; ) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy. Set during the Napoleonic Wars, the work comprises both a fictional narrative and chapters in which Tolstoy discusses history and philosophy. An ...

'', the dance is prominently featured in Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

's novel '' Fathers and Sons''. Arkady reserves the mazurka for Madame Odintsov with whom he is falling in love. During Russian balls, it was danced elegantly and famously by the Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, the second-to-last tsarina of the Russian empire before its collapse in 1918.

Sweden

InSwedish folk music

Swedish folk music is a genre of music based largely on folkloric collection work that began in the early 19th century in Sweden. The primary instrument of Swedish folk music is the fiddle. Another common instrument, unique to Swedish traditio ...

, the quaver or eight-note polska

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

has a similar rhythm to the mazurka, and the two dances have a common origin. The international version of the mazurka was also introduced under that name during the nineteenth century.

United States

The mazurka survives in some old-time fiddle tunes, and also in earlyCajun music

Cajun music (), an emblematic music of Louisiana played by the Cajuns, is rooted in the ballads of the French-speaking Acadians of Canada. Although they are two separate genres, Cajun music is often mentioned in tandem with the Creole-based ...

, though it has largely fallen out of Cajun music now. In the Southern United States it was sometimes known as a "mazuka". Polish Mazurka was danced in upstate New York in the 1950s and 1960s (similarly to the krakowiak, millennium of Christianity) in Polish community centers or social clubs, which can be found throughout the US. The polka remains the best known Polish dance and is regularly seen at weddings, dance halls and public events (e.g., summers outdoors, barn dances) in the US.

California

In addition to being part of the repertoire ofIrish traditional music session

Irish commonly refers to:

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the island and the sovereign state

*** Erse (disambiguati ...

s, the mazurka has been played by a wide variety of cultural groups in California. The mazurka first came to Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

during the Spanish period and danced among Californios

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

. Later, the renowned guitarist Manuel Y. Ferrer, who was born in Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...

to Spanish parents and learned guitar from a Franciscan friar in Santa Barbara but made his career in the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, commonly known as the Bay Area, is a List of regions of California, region of California surrounding and including San Francisco Bay, and anchored by the cities of Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose, California, S ...

, arranged mazurkas for the guitar. During the early 20th century, the mazurka became part of the repertoire of Italian American

Italian Americans () are Americans who have full or partial Italians, Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeastern United States, Northeast and industrial Midwestern United States, Midwestern ...

musicians in San Francisco playing in the '' ballo liscio'' style. Pianist Sid LeProtti, an important Oakland

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major West Coast port, Oakland is ...

-born early jazz musician on the west coast, stated that before jazz took off, he and other musicians in Barbary Coast

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

clubs played mazurkas in addition to waltz

The waltz ( , meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom dance, ballroom and folk dance, in triple (3/4 time, time), performed primarily in closed position. Along with the ländler and allemande, the waltz was sometimes referred to by the ...

es, two-steps, marches

In medieval Europe, a march or mark was, in broad terms, any kind of borderland, as opposed to a state's "heartland". More specifically, a march was a border between realms or a neutral buffer zone under joint control of two states in which diffe ...

, polka

Polka is a dance style and genre of dance music in originating in nineteenth-century Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. Though generally associated with Czech and Central European culture, polka is popular throughout Europe and the ...

s, and schottische

The schottische is a partnered country dance that apparently originated in Bohemia. It was popular in Victorian-era ballrooms as a part of the Bohemian folk-dance craze and left its traces in folk music of countries such as Argentina (Spanish ...

s. One mazurka, played on harmonica, was collected by Sidney Robertson Cowell

Sidney Robertson Cowell (born Sidney William Hawkins; June 2, 1903 – February 23, 1995) was an American ethnomusicologist, collector of folk songs, and the wife of the composer Henry Cowell.

Life and career

She was born on June 2, 1903, i ...

for the WPA California Folk Music Project in 1939 in Tuolumne County

Tuolumne County (), officially the County of Tuolumne, is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 55,620. The county seat and only incorporated city is Sonora.

Tuolumne County comprises the ...

.

See also

*Mazur (dance)

The Mazur is a Polish folk and ballroom dance with origins in the region of Mazovia. It is one of the five Polish national dances.

History

The Mazur was known in Poland already in the 15th century and by the 17th century it became a popular cour ...

*Bourrée

The bourrée (; ; also in England, borry or bore) is a dance of French origin and the words and music that accompany it. The bourrée resembles the gavotte in that it is in Duple and quadruple meter, double time and often has a dactyl (poetry), ...

* Fandango

Fandango is a lively partner dance originating in Portugal and Spain, usually in triple metre, triple meter, traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, tambourine or hand-clapping. Fandango can both be sung and danced. Sung fandango is u ...

* Ländler

The Ländler () is a European folk dance in time. Along with the waltz and allemande, the ländler was sometimes referred to by the generic term German Dance in publications during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Despite its associa ...

* Mazurkas (Chopin)

Over the years 1825–1849, Frédéric Chopin wrote at least 59 compositions for piano called Mazurkas. Mazurka refers to one of the mazurka, traditional Polish dances.

* 58 have been published

** 45 during Chopin's lifetime, of which 41 have opus ...

* Polish music

The music of Poland covers diverse aspects of music and musical traditions which have originated, and are practiced in Poland. Artists from Poland include world-famous classical composers like Frédéric Chopin, Karol Szymanowski, Witold Lutos ...

* Polonaise (dance)

The polonaise (, ; , ) is a dance originating in Poland, and one of the five Polish national dances in time. The original Polish-language name of the dance is ''chodzony'' (), denoting a walking dance. The polonaise dance influenced Europea ...

* Polska (dance)

The polska ( Swedish plural ''polskor'') is a family of music and dance forms shared by the Nordic countries: called ''polsk'' in Denmark, polka or polska in Estonia, ''polska'' in Sweden and Finland, and by several different names in Norway. Norw ...

* Waltz

The waltz ( , meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom dance, ballroom and folk dance, in triple (3/4 time, time), performed primarily in closed position. Along with the ländler and allemande, the waltz was sometimes referred to by the ...

* Pols

The pols and springar are Norwegian folk dances in 3/4. They are essentially fast versions of the Nordic polska

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to t ...

Notes

Bibliography

* Downes, Stephen.Mazurka

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 17 November 2009. * Kallberg, Jeffrey. "The problem of repetition and return in Chopin's mazurkas." Chopin Styles, ed. Jim Samson. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1988. * Kallberg, Jeffrey. "Chopin's Last Style." Journal of the American Musicological Society 38.2 (1985): 264–315. * Michałowski, Kornel, and Jim Samson.

Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 17 November 2009. (esp. section 6, "Formative Influences") * Milewski, Barbara. "Chopin's Mazurkas and the Myth of the Folk." 19th-Century Music 23.2 (1999): 113–35. * Rosen, Charles. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995. * Winokur, Roselyn M. "Chopin and the Mazurka". Diss. Sarah Lawrence College, 1974.

External links

history, description, costumes, music, sources

Mazurka within traditional dances of the County of Nice (France)

The Mazurka Project

*

'Vincent Campbell's Mazurka' as played by Vincent Campbell in Co. Donegal

{{Authority control Mazurka, Dance forms in classical music Irish dances Music of Ireland Polish dances Triple time dances Culture of Masovian Voivodeship