Matthew Fontaine Maury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

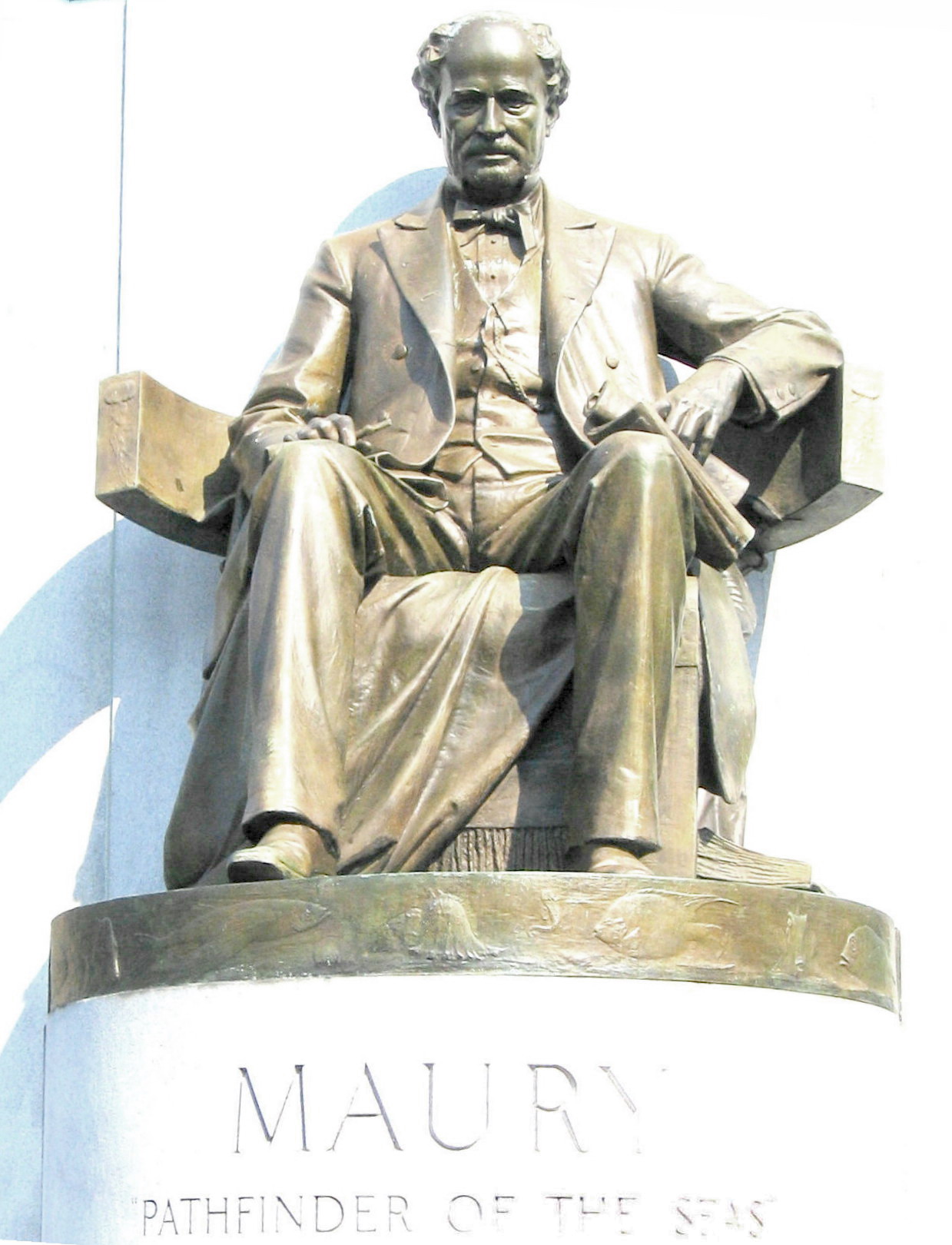

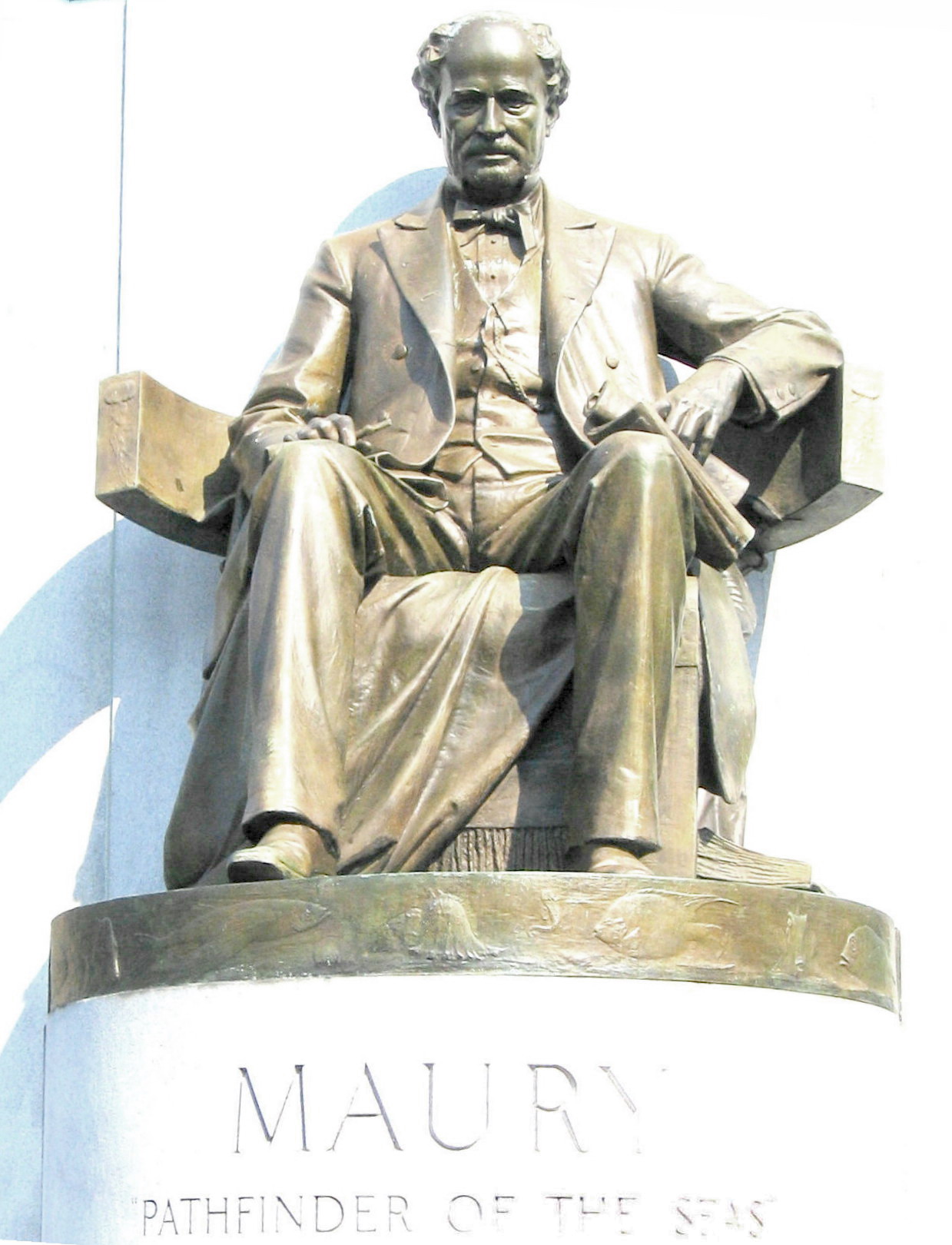

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806February 1, 1873) was an American oceanographer and naval officer, serving the United States and then joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and is considered a founder of modern oceanography. He wrote extensively on the subject, and his book, ''The Physical Geography of the Sea'' (1855), was the first comprehensive work on oceanography to be published.

In 1825, at 19, Maury obtained, through U.S. Representative

Maury's Naval Observatory team included midshipmen assigned to him: James Melville Gilliss, Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke, William Lewis Herndon, Lardner Gibbon, Isaac Strain, John "Jack" Minor Maury II of the USN 1854 Darien Exploration Expedition, and others. Their duty at the observatory was always temporary, and new men had to be trained repeatedly. Thus Lt. Maury was simultaneously employed with astronomical and nautical work, as well as constantly training new temporary men to assist in these works. As his reputation grew, the competition among young midshipmen to be assigned to work with him intensified. Thus, he always had able assistants.

Maury advocated for naval reform, including a school for the Navy that would rival the Army's

Maury's Naval Observatory team included midshipmen assigned to him: James Melville Gilliss, Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke, William Lewis Herndon, Lardner Gibbon, Isaac Strain, John "Jack" Minor Maury II of the USN 1854 Darien Exploration Expedition, and others. Their duty at the observatory was always temporary, and new men had to be trained repeatedly. Thus Lt. Maury was simultaneously employed with astronomical and nautical work, as well as constantly training new temporary men to assist in these works. As his reputation grew, the competition among young midshipmen to be assigned to work with him intensified. Thus, he always had able assistants.

Maury advocated for naval reform, including a school for the Navy that would rival the Army's

After decades of national and international work, Maury received fame and honors, including being knighted by several nations and given medals with precious gems as well as a collection of all medals struck by

After decades of national and international work, Maury received fame and honors, including being knighted by several nations and given medals with precious gems as well as a collection of all medals struck by  Buildings on several college campuses are named in his honor. Maury Hall was the home of the Naval Science Department at the

Buildings on several college campuses are named in his honor. Maury Hall was the home of the Naval Science Department at the  The Mariners' Lake, in

The Mariners' Lake, in

Naomi L. Brooks Elementary School

in 2021 based on Maury's association with the Confedera

with the school's student moniker changed from "Mariners" to "Bees". Nearby Arlington, Va., renamed its 1910 Clarendon Elementary to honor Maury in 1944; Since 1976, the building has been home to the Arlington Arts Center (rebranded in 2022 as the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington). There is a county historical marker outside the former school. Matthew Fontaine Maury School in Fredericksburg was built in 1919-1920 and closed in 1980. The building was converted into condominiums and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Adjoining it is Maury Stadium, built in 1935 and still used for local high school sports events. Numerous historical markers commemorate Maury throughout the South, including those in Richmond, Virginia, Fletcher, North Carolina,

*''On the Navigation of Cape Horn''

*Whaling Charts

*Wind and Current Charts

*

*Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts, 1851, 1854, 1855

*Lieut. Maury's Investigations of the Winds and Currents of the Sea, 1851

*On the Probable Relation between Magnetism and the Circulation of the Atmosphere, 1851

*''Maury's Wind and Current Charts: Gales in the Atlantic'', 1857

*

*Observations to Determine the Solar Parallax, 1856

*''Amazon, and the Atlantic Slopes of South America'', 1853

*Commander M. F. Maury on American Affairs, 1861

*''The Physical Geography of the Sea and Its Meteorology'', 1861

*''Maury's New Elements of Geography for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "First Lessons"

*''Elementary Geography: Designed for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "The World We Live In"

*Published Address of Com. M. F. Maury, before the Fair of the Agricultural & Mechanical Society

*Geology: A Physical Survey of

*''On the Navigation of Cape Horn''

*Whaling Charts

*Wind and Current Charts

*

*Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts, 1851, 1854, 1855

*Lieut. Maury's Investigations of the Winds and Currents of the Sea, 1851

*On the Probable Relation between Magnetism and the Circulation of the Atmosphere, 1851

*''Maury's Wind and Current Charts: Gales in the Atlantic'', 1857

*

*Observations to Determine the Solar Parallax, 1856

*''Amazon, and the Atlantic Slopes of South America'', 1853

*Commander M. F. Maury on American Affairs, 1861

*''The Physical Geography of the Sea and Its Meteorology'', 1861

*''Maury's New Elements of Geography for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "First Lessons"

*''Elementary Geography: Designed for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "The World We Live In"

*Published Address of Com. M. F. Maury, before the Fair of the Agricultural & Mechanical Society

*Geology: A Physical Survey of

CBNnews VIDEO on Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury "''The Father of Modern Oceanography''"

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20070930130602/http://www.mfmnscc.com/ United States Naval Sea Cadet Corps — Matthew Fontaine Maury — Pathfinders Division].

The Maury Project; A comprehensive national program of teacher enhancement based on studies of the physical foundations of oceanography

The Mariner's Museum: Matthew Fontaine Maury Society

Letter to President John Quincy Adams from Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury (1847)

on the "National"

The National (Naval) Observatory and The Virginia Historical Society

(May 1849)

at Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy Historical Center.

The Diary of Betty Herndon Maury

daughter of Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1861–1863.

Matthew Fontaine Maury School in Richmond, Virginia, USA, 1950s

Photographer: Nina Leen. Approximately 200 TIME-LIFE photographs

Astronomical Observations from the Naval Observatory 1845

*Obituary in:

Sample charts by Maury held the American Geographical Society Library, UW Milwaukee

in the digital map collection. {{DEFAULTSORT:Maury, Matthew Fontaine Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1806 births 1873 deaths 19th-century American astronomers American earth scientists 19th-century American educators 19th-century American geographers American oceanographers American people of Dutch descent American people of French descent American Protestants American science writers Burials at Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia) Microscopists People from Spotsylvania County, Virginia People of Virginia in the American Civil War Science and technology in the United States United States Navy officers Writers from Virginia Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Maury family (Virginia) People from Franklin, Tennessee Members of the American Philosophical Society

Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two indi ...

, a midshipman's warrant in the United States Navy. As a midshipman on board the frigate , he almost immediately began to study the seas and record methods of navigation. When a leg injury left him unfit for sea duty, Maury devoted his time to studying navigation, meteorology, winds, and currents.

He became Superintendent of the Depot of Charts and Instruments, later renamed the United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

, in 1844. There, Maury studied thousands of ships' logs and charts. He published the ''Wind and Current Chart of the North Atlantic'', which showed sailors how to use the ocean's currents and winds to their advantage, drastically reducing the length of ocean voyages. Maury's uniform system of recording oceanographic data was adopted by navies and merchant marines worldwide and was used to develop charts for all the major trade routes.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Maury, a Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

n, resigned his commission as a U.S. Navy commander and joined the Confederacy. He spent the war in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

, and Great Britain and France as a Confederate envoy. He helped the Confederacy acquire a ship, , while trying to convince several European powers to help stop the war. Following the war, Maury was eventually pardoned; he accepted a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an Independent city (United States)#Virginia, independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 7,320. It is the county seat of Rockbridge County, Virg ...

.

He died at the institute in 1873 after he had completed an exhausting state-to-state lecture tour on national and international weather forecasting on land. He had also completed his book, ''Geological Survey of Virginia'', and a new series on geography for young people.

Early life and career

Maury was a descendant of the Maury family, a prominent Virginia family ofHuguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

ancestry that can be traced back to 15th-century France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. His grandfather ( the Reverend James Maury) was an inspiring teacher to a future U.S. president, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

. Maury also had Dutch-American ancestry from the Minor family of early Virginia.

He was born in 1806 in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near Fredericksburg; his parents were Richard Maury and Diane Minor Maury. The family moved to Franklin, Tennessee

Franklin is a city in and the county seat of Williamson County, Tennessee, United States. About south of Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville, it is one of the principal cities of the Nashville metropolitan area and Middle Tennessee. As of 2020 Uni ...

when he was five. He wanted to emulate the naval career of his older brother, Flag Lieutenant John Minor Maury, an officer in the U.S. Navy, who caught yellow fever after fighting pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

s. As a result of John's painful death, Matthew's father, Richard, forbade him from joining the Navy. Maury strongly considered attending West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

to get a better education than the Navy could offer. Instead, he obtained a naval appointment through the influence of Tennessee Representative Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two indi ...

, a family friend, in 1825, at the age of 19.

Maury joined the Navy as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

on board the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

, which was carrying the elderly Marquis de Lafayette home to France following his famous 1824 visit to the United States. Almost immediately, Maury began to study the seas and to record methods of navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

. One of the experiences that piqued this interest was circumnavigating the globe on the , his assigned ship and the first U.S. warship to travel around the world.

Scientific career

Maury's seagoing days ended abruptly at the age of 33 after he broke his right leg in astagecoach

A stagecoach (also: stage coach, stage, road coach, ) is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by ...

accident. After that he studied naval meteorology, navigation, and charting the winds and currents. He told his family that his work was inspired by Psalm 8, "Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands... and whatsoever passeth through the paths of the seas."

As officer-in-charge of the United States Navy office in Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, called the "Depot of Charts and Instruments," the young lieutenant became a librarian of the many unorganized log books and records in 1842. On his initiative, he sought to improve seamanship by organizing the information in his office and instituting a reporting system among the nation's shipmasters to gather further information on sea conditions and observations. The product of his work was international recognition and the publication in 1847 of ''Wind and Current Chart of the North Atlantic'', causing the change of purpose and renaming of the depot to the United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

and Hydrographical Office in 1854. He held that position until his resignation in April 1861. Maury was one of the principal advocates for founding a national observatory and he appealed to a science enthusiast and former U.S. president, Representative John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, for the creation of what would eventually become the Naval Observatory. Maury occasionally hosted Adams, who enjoyed astronomy as an avocation, at the Naval Observatory. Concerned that Maury always had a long trek to and from his home on upper Pennsylvania Avenue, Adams introduced an appropriations bill that funded a Superintendent's House on the Observatory grounds. Adams thus felt no constraint in regularly stopping by for a look through the facility's telescope.

As a sailor, Maury noted numerous lessons that ship masters had learned about the effects of adverse winds and drift currents on the path of a ship. The captains recorded the lessons faithfully in their logbooks, which were then forgotten. At the Observatory, Maury uncovered an enormous collection of thousands of old ships' logs and charts in storage in trunks dating back to the start of the U.S. Navy. He pored over the documents, collecting information on winds, calms, and currents for all seas in all seasons. His dream was to put that information in the hands of all captains.

Maury's work on ocean currents

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours ...

and investigations of the whaling industry led him to suspect that a warm-water, ice-free northern passage existed between the Atlantic and Pacific. He thought he detected a warm surface current pushing into the Arctic, and logs of old whaling ships indicated that whales killed in the Atlantic bore harpoons from ships in the Pacific (and vice versa). The frequency of these occurrences seemed unlikely if the whales had traveled around Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

.

Lieutenant Maury published his ''Wind and Current Chart of the North Atlantic'', which showed sailors how to use the ocean's currents and winds to their advantage, drastically reducing the length of voyages. His ''Sailing Directions'' and ''Physical Geography of the Seas and Its Meteorology'' remain standard. Maury's uniform system of recording synoptic oceanographic data was adopted by navies and merchant marines around the world and was used to develop charts for all the major trade routes.

Maury's Naval Observatory team included midshipmen assigned to him: James Melville Gilliss, Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke, William Lewis Herndon, Lardner Gibbon, Isaac Strain, John "Jack" Minor Maury II of the USN 1854 Darien Exploration Expedition, and others. Their duty at the observatory was always temporary, and new men had to be trained repeatedly. Thus Lt. Maury was simultaneously employed with astronomical and nautical work, as well as constantly training new temporary men to assist in these works. As his reputation grew, the competition among young midshipmen to be assigned to work with him intensified. Thus, he always had able assistants.

Maury advocated for naval reform, including a school for the Navy that would rival the Army's

Maury's Naval Observatory team included midshipmen assigned to him: James Melville Gilliss, Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke, William Lewis Herndon, Lardner Gibbon, Isaac Strain, John "Jack" Minor Maury II of the USN 1854 Darien Exploration Expedition, and others. Their duty at the observatory was always temporary, and new men had to be trained repeatedly. Thus Lt. Maury was simultaneously employed with astronomical and nautical work, as well as constantly training new temporary men to assist in these works. As his reputation grew, the competition among young midshipmen to be assigned to work with him intensified. Thus, he always had able assistants.

Maury advocated for naval reform, including a school for the Navy that would rival the Army's United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. That reform was heavily pushed by Maury's "Scraps from the Lucky Bag" and other articles printed in the newspapers, bringing about many changes in the Navy, including his finally fulfilled dream of the creation of the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

.

During its first 1848 meeting, he helped launch the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

(AAAS).

In 1849, Maury spoke out on the need for a transcontinental railroad to join the Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, often abbreviated as simply the East, is a macroregion of the United States located to the east of the Mississippi River. It includes 17–26 states and Washington, D.C., the national capital.

As of 2011, the Eastern ...

to California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. He recommended a southerly route with Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, as the eastern terminus, as it is equidistant from Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and depth () after Lake Superior and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the ...

and the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

. He argued that a southerly route running through Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

would avoid winter snows and could open up commerce with the northern states of Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. Maury also advocated construction of a railroad across the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

.

For his scientific endeavors, Maury was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

in 1852.

International meteorological conference

Maury also called for an international sea and land weather service. Having charted the seas and currents, he worked on charting land weather forecasting. Congress refused to appropriate funds for a land system of weather observations. Maury became convinced that adequate scientific knowledge of the sea could be obtained only through international cooperation. He proposed that the United States invite the maritime nations of the world to a conference to establish a "universal system" of meteorology, and he was the leading spirit of a pioneer scientific conference when it met inBrussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

in 1853. Within a few years, nations owning three-fourths of the shipping of the world were sending their oceanographic observations to Maury at the Naval Observatory, where the information was evaluated and the results were given worldwide distribution.

As its representative at the conference, the United States sent Maury. As a result of the Brussels Conference, many nations, including many traditional enemies, agreed to cooperate in sharing land and sea weather data using uniform standards. It was soon after the Brussels conference that Prussia, Spain, Sardinia, the Free City of Hamburg, the Republic of Bremen, Chile, Austria, Brazil, and others agreed to join the enterprise.

The Pope established honorary flags of distinction for the ships of the Papal States, which could be awarded only to the vessels that filled out and sent to Maury in Washington, DC, the Maury abstract logs.

Proposed deportation of slaves to Brazil

Maury's stance on the institution of slavery has been termed "proslavery international". Maury, along with other politicians, newspaper editors, merchants, and United States government officials, envisioned a future for slavery that linked the United States, the Caribbean Sea, and the Amazon basin in Brazil. He believed the future of United States commerce lay in South America, colonized by white southerners and their enslaved people. There, Maury claimed, was "work to be done by Africans with the American axe in his hand." In the 1850s, he studied a way to send Virginia's slaves to Brazil as a way to phase out slavery in the state gradually. Maury was aware of an 1853 survey of the Amazon region conducted by the Navy Lt. William Lewis Herndon. The 1853 expedition aimed to map the area for trade so that American traders could go "with their goods and chattels ncluding enslaved peopleto settle and to trade goods from South American countries along the river highways of the Amazon valley". Brazil maintained legal enslavement but had prohibited the importation of newly enslaved people from Africa in 1850 under the pressure of the British. Maury proposed that moving people enslaved in the United States to Brazil would reduce or eliminate slavery over time in as many areas of the southern United States as possible and would end new enslavement for Brazil. Maury's primary concern, however, was neither the freedom of enslaved people nor the amelioration of slavery in Brazil, but rather an absolution for slaveholders of Virginia and other southern states. Maury wrote to his cousin, "Therefore I see in the slave territory of the Amazon the SAFETY VALVE of the Southern States." Maury wanted to open up the Amazon to free navigation in his plan. However, Emperor Pedro II's government firmly rejected the proposals, and Maury's proposal received little or no support in the United States, especially in the South, which sought to perpetuate the institution and the riches made off the yoke of slavery. By 1855, the proposal had failed. Brazil authorized free navigation to all nations in the Amazon in 1866, only when it was at war against Paraguay, when free navigation in the area had become necessary. Maury was not an enslaver, but he did not actively oppose the institution of slavery. An article tying his legacy in oceanography to the slave trade suggested that Maury was ambivalent about slavery, seeing it as wrong but not intent on forcing others to free enslaved people. However, a recent article explaining the removal of his monument from Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, illustrated a proslavery stance through deep ties to the slave trade that accompanied his scientific achievements.American Civil War

Maury staunchly opposed secession, but in 1860, he wrote letters to the governors of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland urging them to stop the momentum toward war. When Virginia declared secession in April 1861, Maury nonetheless resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy, choosing to fight against the North. With the outbreak of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Maury joined the Confederacy.

Upon his resignation from the U.S. Navy, the Virginia governor appointed Maury commander of the Virginia Navy. When this was consolidated into the Confederate Navy, Maury was made a Commander in the Confederate States Navy and appointed as chief of the Naval Bureau of Coast, Harbor, and River Defense. In this role, Maury helped develop the first electrically controlled naval mine, which caused havoc for U.S. shipping. He'd had experience with transatlantic cable and electricity flowing through wires underwater when working with Cyrus West Field and Samuel Finley Breese Morse. The naval mines, called torpedoes at that time, were similar to present-day contact mines and were said by the Secretary of the Navy in 1865 "to have cost the Union more vessels than all other causes combined."

In September 1862, Maury, partly because of his international reputation, and partly due to jealousy of superior officers who wanted him placed at some distance, was ordered on special service to England. There, he sought to purchase and fit ships for the Confederacy and persuade European powers to recognize and support the Confederacy. Maury traveled to England, Ireland, and France, acquiring and fitting out ships for the Confederacy and soliciting supplies. Through speeches and newspaper publications, Maury unsuccessfully called for European nations to intercede on behalf of the Confederacy and help end the American Civil War. Maury established relations for the Confederacy with Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

of France and Archduke Maximilian of Austria, who, on April 10, 1864, was proclaimed Emperor of Mexico.

At an early stage in the war, the Confederate States Congress assigned Maury and Francis H. Smith, a mathematics professor at the University of Virginia, to develop a system of weights and measures.

Later life

Maury was in the West Indies on his way back to the Confederacy when he learned of its collapse. The war had brought ruin to many in Fredericksburg, where Maury's immediate family lived. On the advice of Robert E. Lee and other friends, he decided not to return to Virginia but sent a letter of surrender to U.S. naval forces in the Gulf of Mexico and headed for Mexico. There Maximilian, whom he had met in Europe, appointed him "Imperial Commissioner of Colonization". Maury and Maximilian planned to entice former Confederates to emigrate to Mexico, building Carlotta and New Virginia Colony for displaced Confederates and immigrants from other lands. Upon learning of the plan, Lee wrote Maury saying, "The thought of abandoning the country, and all that must be left in it, is abhorrent to my feelings, and I prefer to struggle for its restoration, and share its fate, rather than to give up all as lost." In the end, the plan did not attract the intended immigrants and Maximilian, facing increasing opposition in Mexico, ended it. Maury then returned to England in 1866 and found work there. In 1868 he was pardoned by the federal government and returned to the US, accepting a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, holding the chair of physics. While in Lexington, he completed a physical survey of Virginia, which he documented in the book ''ThePhysical Geography

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, h ...

of Virginia''. He had once been a gold mining superintendent outside Fredericksburg and had studied geology intensely during that time, so he was well-equipped to write such a book. He aimed to assist war-torn Virginia in rebuilding by discovering and extracting minerals, improving farming, etc. He lectured extensively in the United States and abroad. He advocated for creating a state agricultural college as an adjunct to Virginia Military Institute. This led to the establishment at Blacksburg of the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College, later renamed Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, in 1872. Maury was offered the position as its first president but turned it down because of his age.

He had previously been suggested as president of the College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public university, public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III of England, William III and Queen ...

in Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an Independent city (United States), independent city in Virginia, United States. It had a population of 15,425 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern par ...

, in 1848 by Benjamin Blake Minor in his publication the '' Southern Literary Messenger''. He considered becoming president of St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland, the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, the Capstone, or Bama) is a Public university, public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of ...

, and the University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville (or The University of Tennessee; UT; UT Knoxville; or colloquially UTK or Tennessee) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Knoxville, Tennessee, United St ...

. From statements that he made in letters, it appears that he preferred being close to General Robert E. Lee in Lexington, where Lee was president of Washington College. Maury served as a pallbearer for Lee. He also gave talks in Europe about cooperation on a weather bureau for land, just as he had charted the winds and predicted storms at sea many years before. He gave speeches until his last days when he collapsed while giving one. He went home after he recovered and told his wife Ann Hull Herndon-Maury, "I have come home to die."

Death and burial

He died at home in Lexington at 12:40 pm on Saturday, February 1, 1873. He was exhausted from traveling throughout the nation giving speeches promoting land meteorology. His eldest son, Major Richard Launcelot Maury, and son-in-law, Major Spottswood Wellford Corbin, attended him at the time. Maury asked his daughters and wife to leave the room. His last words, recorded verbatim, were "all's well," a nautical expression meaning calm conditions at sea. His body was placed on display in the Virginia Military Institute library. Maury was initially buried in the Gilham family vault in Lexington's cemetery, across fromStonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general and military officer who served during the American Civil War. He played a prominent role in nearly all military engagements in the eastern the ...

, until, after some delay, his remains were taken through Goshen Pass to Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

the following year He was reburied between Presidents James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

and John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Legacy

Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any pope in hist ...

during his pontificate, a book dedication and more from Father Angelo Secchi, who was a student of Maury from 1848 to 1849 in the United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

. The two remained lifelong friends. Other religious friends of Maury included James Hervey Otey, his former teacher who, before 1857, worked with Bishop Leonidas Polk on the construction of the University of the South in Tennessee. While visiting there, Maury was convinced by his old teacher to give the "cornerstone speech."

As a U.S. Navy officer, he was required to decline awards from foreign nations. Some were offered to Maury's wife, Ann Hull Herndon-Maury, who accepted them for her husband. Some have been placed at Virginia Military Institute or lent to the Smithsonian. He became a commodore (often a title of courtesy) in the Virginia Provisional Navy and a Commander in the Confederacy.

Buildings on several college campuses are named in his honor. Maury Hall was the home of the Naval Science Department at the

Buildings on several college campuses are named in his honor. Maury Hall was the home of the Naval Science Department at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

and headquarters of the university's Navy ROTC battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

until being renamed in 2022. The original building of the College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public university, public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III of England, William III and Queen ...

Virginia Institute of Marine Science was named Maury Hall as well, but renamed York River Hall in 2020. Another Maury Hall housed the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department and the Robotics and Control Engineering Department at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

. On February 17, 2023, the academy announced that it had renamed this building in honor of Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

, the only Naval Academy graduate to become President of the United States. The change had been recommended by a naming commission created by federal law to reexamine Confederate-related names and symbols on military installations. James Madison University

James Madison University (JMU, Madison, or James Madison) is a public university, public research university in Harrisonburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1908, the institution was renamed in 1938 in honor of the fourth president of the ...

also has a Maury Hall, the university's first academic and administrative building. In the wake of the 2020 George Floyd protests

The George Floyd protests were a series of protests, riots, and demonstrations against police brutality that began in Minneapolis in the United States on May 26, 2020. The protests and civil unrest began in Minneapolis as Reactions to the mu ...

, JMU student organizations called for renaming the building. On Monday, June 22, 2020, hearing the calls of students and alums, the university president announced it would recommend to the JMU board of visitors to rename Maury Hall, along with Ashby Hall and Jackson Hall.

Ships have been named in his honor, including various vessels named ; USS ''Commodore Maury'' (SP-656), a patrol vessel and minesweeper of World War I; and a World War II Liberty Ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Although British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost cons ...

. Additionally, Tidewater Community College, based in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. It had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Virginia, third-most populous city ...

, owns the R/V ''Matthew F. Maury''. The ship is used for oceanography research and student cruises. In March 2013, the U.S. Navy launched the oceanographic survey ship USNS ''Maury'' (T-AGS-66), in 2023 the ship was renamed USNS ''Marie Tharp''.

The Mariners' Lake, in

The Mariners' Lake, in Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an Independent city (United States), independent city in southeastern Virginia, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the List of c ...

, had been named after Maury but had its name changed during the George Floyd protests. The lake is located on the Mariners' Museum property and is encircled by a walking trail.

The Maury River, entirely in Rockbridge County, Virginia

Rockbridge County is a County (United States), county in the Shenandoah Valley on the western edge of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 22,650. Its count ...

, near Virginia Military Institute (where Maury taught), also honors the scientist, as does Maury crater, on the Moon.

Matthew Fontaine Maury High School in Norfolk, Virginia, is named after him. Matthew Maury Elementary School in Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

, was built in 1929. The school was renameNaomi L. Brooks Elementary School

in 2021 based on Maury's association with the Confedera

with the school's student moniker changed from "Mariners" to "Bees". Nearby Arlington, Va., renamed its 1910 Clarendon Elementary to honor Maury in 1944; Since 1976, the building has been home to the Arlington Arts Center (rebranded in 2022 as the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington). There is a county historical marker outside the former school. Matthew Fontaine Maury School in Fredericksburg was built in 1919-1920 and closed in 1980. The building was converted into condominiums and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Adjoining it is Maury Stadium, built in 1935 and still used for local high school sports events. Numerous historical markers commemorate Maury throughout the South, including those in Richmond, Virginia, Fletcher, North Carolina,

Franklin, Tennessee

Franklin is a city in and the county seat of Williamson County, Tennessee, United States. About south of Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville, it is one of the principal cities of the Nashville metropolitan area and Middle Tennessee. As of 2020 Uni ...

, and several in Chancellorsville, Virginia

Chancellorsville is a historic site and unincorporated community in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, United States, about ten miles west of Fredericksburg. The name of the locale derives from the mid-19th century inn operated by the family of Geo ...

.

The Matthew Fontaine Maury Papers collection at the Library of Congress contains over 14,000 items. It documents Maury's extensive career and scientific endeavors, including correspondence, notebooks, lectures, and written speeches.

On July 2, 2020, the mayor of Richmond, Levar Stoney ordered the removal of a statue of Maury erected in 1929 on Richmond's Monument Avenue. The mayor used his emergency powers to bypass a state-mandated review process, calling the statue a "severe, immediate and growing threat to public safety."

Publications

*''On the Navigation of Cape Horn''

*Whaling Charts

*Wind and Current Charts

*

*Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts, 1851, 1854, 1855

*Lieut. Maury's Investigations of the Winds and Currents of the Sea, 1851

*On the Probable Relation between Magnetism and the Circulation of the Atmosphere, 1851

*''Maury's Wind and Current Charts: Gales in the Atlantic'', 1857

*

*Observations to Determine the Solar Parallax, 1856

*''Amazon, and the Atlantic Slopes of South America'', 1853

*Commander M. F. Maury on American Affairs, 1861

*''The Physical Geography of the Sea and Its Meteorology'', 1861

*''Maury's New Elements of Geography for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "First Lessons"

*''Elementary Geography: Designed for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "The World We Live In"

*Published Address of Com. M. F. Maury, before the Fair of the Agricultural & Mechanical Society

*Geology: A Physical Survey of

*''On the Navigation of Cape Horn''

*Whaling Charts

*Wind and Current Charts

*

*Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts, 1851, 1854, 1855

*Lieut. Maury's Investigations of the Winds and Currents of the Sea, 1851

*On the Probable Relation between Magnetism and the Circulation of the Atmosphere, 1851

*''Maury's Wind and Current Charts: Gales in the Atlantic'', 1857

*

*Observations to Determine the Solar Parallax, 1856

*''Amazon, and the Atlantic Slopes of South America'', 1853

*Commander M. F. Maury on American Affairs, 1861

*''The Physical Geography of the Sea and Its Meteorology'', 1861

*''Maury's New Elements of Geography for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "First Lessons"

*''Elementary Geography: Designed for Primary and Intermediate Classes''

*Geography: "The World We Live In"

*Published Address of Com. M. F. Maury, before the Fair of the Agricultural & Mechanical Society

*Geology: A Physical Survey of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

; Her Geographical Position, Its Commercial Advantages and National Importance, Virginia Military Institute, 1869

See also

* Bathymetric chart * Flying Cloud *National Institute for the Promotion of Science

The National Institution for the Promotion of Science organization was established in Washington, D.C., in May 1840, and was heir to the mantle of the earlier ''Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences''. The National Institutio ...

*Oceanography#Notable oceanographers, Notable global oceanographers

*Prophet Without Honor

References

Further reading

* * * * * *External links

* *. 1996 website retrieved via the Wayback Machine, Wayback Search EngineCBNnews VIDEO on Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury "''The Father of Modern Oceanography''"

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20070930130602/http://www.mfmnscc.com/ United States Naval Sea Cadet Corps — Matthew Fontaine Maury — Pathfinders Division].

The Maury Project; A comprehensive national program of teacher enhancement based on studies of the physical foundations of oceanography

The Mariner's Museum: Matthew Fontaine Maury Society

Letter to President John Quincy Adams from Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury (1847)

on the "National"

United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

regarding a written description of the observatory, in detail, with other information relating thereto, including an explanation of the objects and uses of the various instruments.The National (Naval) Observatory and The Virginia Historical Society

(May 1849)

at Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy Historical Center.

The Diary of Betty Herndon Maury

daughter of Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1861–1863.

Matthew Fontaine Maury School in Richmond, Virginia, USA, 1950s

Photographer: Nina Leen. Approximately 200 TIME-LIFE photographs

Astronomical Observations from the Naval Observatory 1845

*Obituary in:

Sample charts by Maury held the American Geographical Society Library, UW Milwaukee

in the digital map collection. {{DEFAULTSORT:Maury, Matthew Fontaine Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1806 births 1873 deaths 19th-century American astronomers American earth scientists 19th-century American educators 19th-century American geographers American oceanographers American people of Dutch descent American people of French descent American Protestants American science writers Burials at Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia) Microscopists People from Spotsylvania County, Virginia People of Virginia in the American Civil War Science and technology in the United States United States Navy officers Writers from Virginia Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Maury family (Virginia) People from Franklin, Tennessee Members of the American Philosophical Society