Marcus Oliphant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian

Rutherford's Cavendish Laboratory was carrying out some of the most advanced research into

Rutherford's Cavendish Laboratory was carrying out some of the most advanced research into

In 1938, Oliphant became involved with the development of

In 1938, Oliphant became involved with the development of

Great Britain was at war and authorities there thought that the development of an atomic bomb was urgent, but there was much less urgency in the United States. Oliphant was one of the people who pushed the American program into motion. On 5 August 1941, Oliphant flew to the United States in a

Great Britain was at war and authorities there thought that the development of an atomic bomb was urgent, but there was much less urgency in the United States. Oliphant was one of the people who pushed the American program into motion. On 5 August 1941, Oliphant flew to the United States in a  On 26 October 1942, Oliphant embarked from Melbourne, taking Rosa and the children back with him. The wartime sea voyage on the French ''Desirade'' was again a slow one, and they did not reach Glasgow until 28 February 1943. He had to leave them behind once more in November 1943 after the British

On 26 October 1942, Oliphant embarked from Melbourne, taking Rosa and the children back with him. The wartime sea voyage on the French ''Desirade'' was again a slow one, and they did not reach Glasgow until 28 February 1943. He had to leave them behind once more in November 1943 after the British

Oliphant was an advocate of nuclear weapons research. He served on the post-war Technical Committee that advised the British government on nuclear weapons, and publicly declared that Britain needed to develop its own nuclear weapons independent of the United States to "avoid the danger of becoming a lesser power". The establishment of a world-class nuclear physics research capability in Australia was intimately linked with the government's plans to develop nuclear power and weapons. Locating the new research institute in Canberra would place it close to the

Oliphant was an advocate of nuclear weapons research. He served on the post-war Technical Committee that advised the British government on nuclear weapons, and publicly declared that Britain needed to develop its own nuclear weapons independent of the United States to "avoid the danger of becoming a lesser power". The establishment of a world-class nuclear physics research capability in Australia was intimately linked with the government's plans to develop nuclear power and weapons. Locating the new research institute in Canberra would place it close to the  Oliphant founded the

Oliphant founded the

Places and things named in honour of Oliphant include the Oliphant Building at the Australian National University, the Mark Oliphant Conservation Park, a South Australian high schools science competition, the Oliphant Wing of the Physics Building at the University of Adelaide, a school in the Adelaide suburb of Munno Para West, and a bridge on Parkes Way in Canberra near his old laboratory at the ANU. His papers are in the Adolph Basser Library at the Australian Academy of Science, and the Barr Smith Library at the University of Adelaide. Oliphant's nephew,

Places and things named in honour of Oliphant include the Oliphant Building at the Australian National University, the Mark Oliphant Conservation Park, a South Australian high schools science competition, the Oliphant Wing of the Physics Building at the University of Adelaide, a school in the Adelaide suburb of Munno Para West, and a bridge on Parkes Way in Canberra near his old laboratory at the ANU. His papers are in the Adolph Basser Library at the Australian Academy of Science, and the Barr Smith Library at the University of Adelaide. Oliphant's nephew,

File:J150W-statue-Oliphant.jpg, Statue on

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate ca ...

and humanitarian

Humanitarianism is an active belief in the value of human life, whereby humans practice benevolent treatment and provide assistance to other humans to reduce suffering and improve the conditions of humanity for moral, altruistic, and emotiona ...

who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifest ...

and in the development of nuclear weapons.

Born and raised in Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater A ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, Oliphant graduated from the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on ...

in 1922. He was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship

The 1851 Research Fellowship is a scheme conducted by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 to annually award a three-year research scholarship to approximately eight "young scientists or engineers of exceptional promise". The fellowshi ...

in 1927 on the strength of the research he had done on mercury, and went to England, where he studied under Sir Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

's Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is name ...

. There, he used a particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams.

Large accelerators are used for fun ...

to fire heavy hydrogen nuclei (deuteron

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

s) at various targets. He discovered the respective nuclei of helium-3

Helium-3 (3He see also helion) is a light, stable isotope of helium with two protons and one neutron (the most common isotope, helium-4, having two protons and two neutrons in contrast). Other than protium (ordinary hydrogen), helium-3 is th ...

(helions) and of tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus ...

(tritons). He also discovered that when they reacted with each other, the particles that were released had far more energy than they started with. Energy had been liberated from inside the nucleus, and he realised that this was a result of nuclear fusion.

Oliphant left the Cavendish Laboratory in 1937 to become the Poynting Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university located in Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingha ...

. He attempted to build a cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: J ...

at the university, but its completion was postponed by the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe in 1939. He became involved with the development of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

, heading a group at the University of Birmingham that included John Randall and Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biography

...

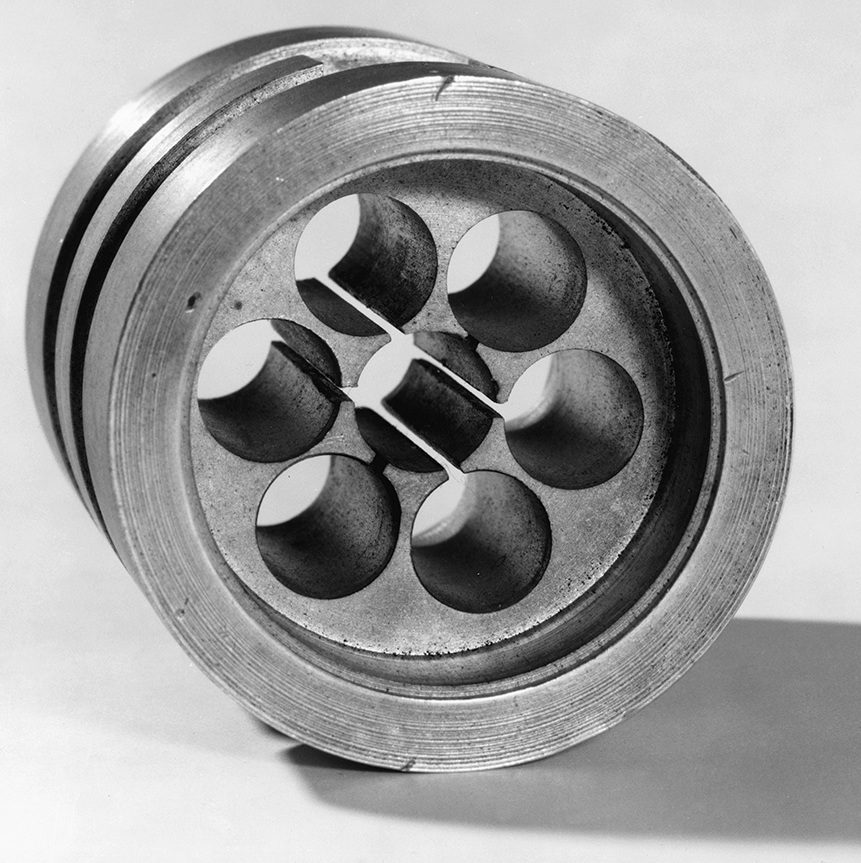

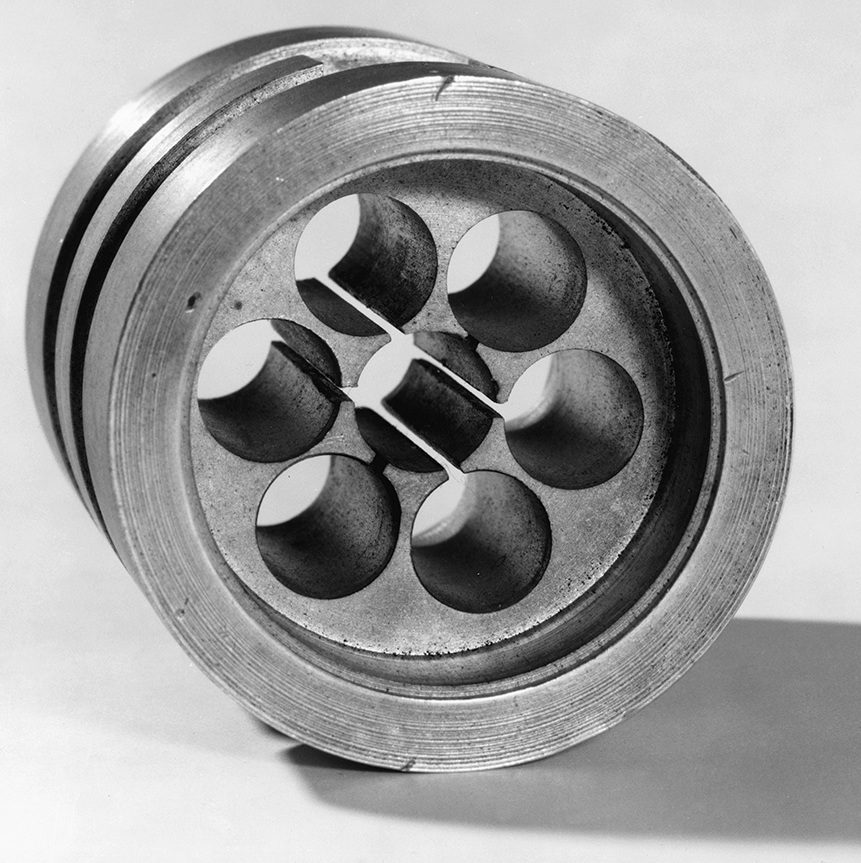

. They created a radical new design, the cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field ...

, that made microwave radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, ...

possible. Oliphant also formed part of the MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram fro ...

, which reported in July 1941, that an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

was not only feasible, but might be produced as early as 1943. Oliphant was instrumental in spreading the word of this finding in the United States, thereby starting what became the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Later in the war, he worked on it with his friend Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

at the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emer ...

, developing electromagnetic isotope separation

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derived ...

, which provided the fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be typ ...

component of the Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress '' Enola Gay ...

atomic bomb used in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

in August 1945.

After the war, Oliphant returned to Australia as the first director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering

The Research School of Physics (RSPhys) was established with the creation of the Australian National University (ANU) in 1947. Located at the ANU's main campus in Canberra, the school is one of the four founding research schools in the ANU's In ...

at the new Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

(ANU), where he initiated the design and construction of the world's largest (500 megajoule) homopolar generator

A homopolar generator is a DC electrical generator comprising an electrically conductive disc or cylinder rotating in a plane perpendicular to a uniform static magnetic field. A potential difference is created between the center of the disc and th ...

. He retired in 1967, but was appointed Governor of South Australia

The governor of South Australia is the representative in South Australia of the Monarch of Australia, currently King Charles III. The governor performs the same constitutional and ceremonial functions at the state level as does the governor-gen ...

on the advice of Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of govern ...

Don Dunstan

Donald Allan Dunstan (21 September 1926 – 6 February 1999) was an Australian politician who served as the 35th premier of South Australia from 1967 to 1968, and again from 1970 to 1979. He was a member of the Parliament of South Australia, ...

. He became the first South Australian-born governor of South Australia. He assisted in the founding of the Australian Democrats

The Australian Democrats is a centrist political party in Australia. Founded in 1977 from a merger of the Australia Party and the New Liberal Movement, both of which were descended from Liberal Party dissenting splinter groups, it was Australi ...

political party, and he was the chairman of the meeting in Melbourne in 1977, at which the party was launched. Late in life he witnessed his wife, Rosa, suffer before her death in 1987, and he became an advocate for voluntary euthanasia

Euthanasia (from el, εὐθανασία 'good death': εὖ, ''eu'' 'well, good' + θάνατος, ''thanatos'' 'death') is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different eut ...

. He died in Canberra in 2000.

Early life

Marcus "Mark" Laurence Elwin Oliphant was born on 8 October 1901 inKent Town

Kent Town is an inner suburb of Adelaide, South Australia. It is located in the City of Norwood Payneham St Peters, City of Norwood Payneham & St Peters.

History

Kent Town was named for Dr. Benjamin Archer Kent (1808 – 25 November 1864), a m ...

, a suburb of Adelaide. His father was Harold George "Baron" Olifent, a civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

with the South Australian Engineering and Water Supply Department and part-time lecturer in economics with the Workers' Educational Association

The Workers' Educational Association (WEA), founded in 1903, is the UK's largest voluntary sector provider of adult education and one of Britain's biggest charities. The WEA is a democratic and voluntary adult education movement. It delivers lea ...

. His mother was Beatrice Edith Fanny Oliphant, née Tucker, an artist. He was named after Marcus Clarke

Marcus Andrew Hislop Clarke (24 April 1846 – 2 August 1881) was an English-born Australian novelist, journalist, poet, editor, librarian, and playwright. He is best known for his 1874 novel ''For the Term of His Natural Life'', about the con ...

, the Australian author, and Laurence Oliphant, the British traveller and mystic. Most people called him Mark; this became official when he was knighted in 1959. He had four younger brothers: Roland, Keith, Nigel and Donald; all were registered at birth with the surname Olifent. His grandfather, Harry Smith Olifent (7 November 1848 – 30 January 1916) was a clerk at the Adelaide GPO, and his great-grandfather James Smith Olifent (c. 1818 – 21 January 1890) and his wife Eliza (c. 1821 – 18 October 1881) left their native Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

for South Australia aboard the barque ''Ruby'', arriving in March 1854. He would later be appointed Superintendent of the Adelaide Destitute Asylum, and Eliza Olifent was appointed Matron of the establishment in 1865. Mark's parents were Theosophist

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

s, and as such may have refrained from eating meat. Marcus became a lifelong vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat ( red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetaria ...

while a boy, after witnessing the slaughter of pigs on a farm. He was found to be completely deaf in one ear and he needed glasses for severe astigmatism

Astigmatism is a type of refractive error due to rotational asymmetry in the eye's refractive power. This results in distorted or blurred vision at any distance. Other symptoms can include eyestrain, headaches, and trouble driving at ni ...

and short-sightedness.

Oliphant was first educated at primary schools in Goodwood and Mylor, after the family moved there in 1910. He attended Unley High School

Unley High School, located in Netherby, South Australia.

History

Unley High School was founded in 1910 as one of the first public high schools to be established after Adelaide High School in 1908. Initially it was under the control of the H ...

in Adelaide, and, for his final year in 1918, Adelaide High School

Adelaide High School is a coeducational state high school situated on the corner of West Terrace and Glover Avenue in the Adelaide Parklands. Following the Advanced School for Girls, it was the second government high school in South Australia ...

. After graduation he failed to obtain a bursary

A bursary is a monetary award made by any educational institution or funding authority to individuals or groups. It is usually awarded to enable a student to attend school, university or college when they might not be able to, otherwise. Some aw ...

to attend university, so he took a job with S. Schlank & Co., an Adelaide manufacturing jeweller noted for medallions. He then secured a cadetship with the State Library of South Australia

The State Library of South Australia, or SLSA, formerly known as the Public Library of South Australia, located on North Terrace, Adelaide, is the official library of the Australian state of South Australia. It is the largest public research ...

, which allowed him to take courses at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on ...

at night.

In 1919, Oliphant began studying at the University of Adelaide. At first he was interested in a career in medicine, but later in the year Kerr Grant, the physics professor, offered him a cadetship in the Physics Department. It paid 10 shillings a week (), the same amount that Oliphant received for working at the State Library, but it allowed him to take any university course that did not conflict with his work for the department. He received his Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

(BSc) degree in 1921 and then did honours

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

the following year, supervised by Grant. Roy Burdon, who acted as head of the department when Grant went on sabbatical in 1925, worked with Oliphant to produce two papers in 1927 on the properties of mercury, "The Problem of the Surface Tension of Mercury and the Action of Aqueous Solutions on a Mercury Surface" and "Adsorption of Gases on the Surface of Mercury". Oliphant later recalled that Burdon taught him "the extraordinary exhilaration there was in even minor discoveries in the field of physics".

Oliphant married Rosa Louise Wilbraham, who was also from Adelaide, on 23 May 1925. The two had known each other since they were teenagers. He made Rosa's wedding ring in the laboratory from a gold nugget (from the Coolgardie Goldfields) that his father had given him.

Cavendish Laboratory

In 1925, Oliphant heard a speech given by the New Zealand physicist SirErnest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

, and he decided he wanted to work for him – an ambition that he fulfilled by earning a position at the Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is name ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in 1927. He applied for an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship

The 1851 Research Fellowship is a scheme conducted by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 to annually award a three-year research scholarship to approximately eight "young scientists or engineers of exceptional promise". The fellowshi ...

on the strength of the research he had done on mercury with Burdon. It came with a living allowance of £250 per annum (). When word came through that he had been awarded a fellowship, he wired

''Wired'' (stylized as ''WIRED'') is a monthly American magazine, published in print and online editions, that focuses on how emerging technologies affect culture, the economy, and politics. Owned by Condé Nast, it is headquartered in San Fran ...

Rutherford and Trinity College, Cambridge. Both accepted him.

Rutherford's Cavendish Laboratory was carrying out some of the most advanced research into

Rutherford's Cavendish Laboratory was carrying out some of the most advanced research into nuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

in the world at the time. Oliphant was invited to afternoon tea by Rutherford and Lady Rutherford. He soon met other researchers at the Cavendish Laboratory, including Patrick Blackett

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett (18 November 1897 – 13 July 1974) was a British experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism, winning the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1948. ...

, Edward Bullard

Sir Edward Crisp Bullard FRS (21 September 1907 – 3 April 1980) was a British geophysicist who is considered, along with Maurice Ewing, to have founded the discipline of marine geophysics. He developed the theory of the geodynamo, pioneere ...

, James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which insp ...

, John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

, Charles Ellis, Peter Kapitza

Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa or Peter Kapitza ( Russian: Пётр Леонидович Капица, Romanian: Petre Capița ( – 8 April 1984) was a leading Soviet physicist and Nobel laureate, best known for his work in low-temperature physics ...

, Philip Moon

Philip Burton Moon FRS (17 May 1907 – 9 October 1994) was a British nuclear physicist. He is most remembered for his research work in atomic physics and nuclear physics. He is one of the British scientists who participated in the United S ...

and Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (6 October 1903 – 25 June 1995) was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate. He is best known for his work with John Cockcroft to construct one of the earliest types of particle accelerator, the Cockcroft–Walto ...

. There were two fellow Australians: Harrie Massey

Sir Harrie Stewart Wilson Massey (16 May 1908 – 27 November 1983) was an Australian mathematical physicist who worked primarily in the fields of atomic and atmospheric physics.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne and Cambridge Unive ...

and John Keith Roberts

John Keith Roberts (16 April 1897 – 126 April 1944) was an Australian physicist who was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship, and went to England, where he studied under Sir Ernest Rutherford at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Labo ...

. Oliphant would become especially close friends with Cockcroft. The laboratory had considerable talent but little money to spare, and tended to use a "string and sealing wax" approach to experimental equipment. Oliphant had to buy his own equipment, at one point spending £24 () of his allowance on a vacuum pump

A vacuum pump is a device that draws gas molecules from a sealed volume in order to leave behind a partial vacuum. The job of a vacuum pump is to generate a relative vacuum within a capacity. The first vacuum pump was invented in 1650 by Otto ...

.

Oliphant submitted his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper

''Piled Higher and Deeper'' (also known as ''PhD Comics''), is a newsp ...

thesis on ''The Neutralization of Positive Ions at Metal Surfaces, and the Emission of Secondary Electrons'' in December 1929. For his ''viva

Viva may refer to:

Companies and organisations

* Viva (network operator), a Dominican mobile network operator

* Viva Air, a Spanish airline taken over by flag carrier Iberia

* Viva Air Dominicana

* VIVA Bahrain, a telecommunication company

* Vi ...

'', he was examined by Rutherford and Ellis. Receiving his degree was the attainment of a major life goal, but it also meant the end of his 1851 Exhibition Scholarship. Oliphant secured an 1851 Senior Studentship, of which there were five awarded each year. It came with a living allowance of £450 per annum () for two years, with the possibility of a one-year extension in exceptional circumstances, which Oliphant was also awarded.

A son, Geoffrey Bruce Oliphant, was born 6 October 1930, but he died of meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion ...

on 5 September 1933, and was interred in an unmarked grave in the Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge alongside Timothy Cockcroft, the infant son of Sir John and Lady Elizabeth Cockcroft, who had died the year before. Unable to have more children, the Oliphants adopted a four-month-old boy, Michael John, in 1936, and a daughter, Vivian, in 1938.

In 1932 and 1933, the scientists at the Cavendish Laboratory made a series of ground-breaking discoveries. Cockcroft and Walton bombarded lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense solid ...

with high energy protons and succeeded in transmuting it into energetic nuclei of helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

. This was one of the earliest experiments to change the atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden experiments, Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After th ...

of one element to another by artificial means. Chadwick then devised an experiment that discovered a new, uncharged particle with roughly the same mass as the proton: the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons behav ...

. In 1933, Blackett discovered tracks in his cloud chamber

A cloud chamber, also known as a Wilson cloud chamber, is a particle detector used for visualizing the passage of ionizing radiation.

A cloud chamber consists of a sealed environment containing a supersaturated vapour of water or alcohol. A ...

that confirmed the existence of the positron

The positron or antielectron is the antiparticle or the antimatter counterpart of the electron. It has an electric charge of +1 '' e'', a spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same mass as an electron. When a positron collide ...

and revealed the opposing spiral traces of positron–electron pair production

Pair production is the creation of a subatomic particle and its antiparticle from a neutral boson. Examples include creating an electron and a positron, a muon and an antimuon, or a proton and an antiproton. Pair production often refers ...

.

Oliphant followed up the work by constructing a particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams.

Large accelerators are used for fun ...

that could fire protons with up to 600,000 electronvolts

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. ...

of energy. He soon confirmed the results of Cockcroft and Walton on the artificial disintegration of the nucleus and positive ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

s. He produced a series of six papers over the following two years. In 1933, the Cavendish Laboratory received a gift from the American physical chemist

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

Gilbert N. Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a Dean of the College of Chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bond ...

of a few drops of heavy water. The accelerator was used to fire heavy hydrogen nuclei (''deuteron

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

s'', which Rutherford called ''diplons'') at various targets. Working with Rutherford and others, Oliphant thereby discovered the nuclei of helium-3

Helium-3 (3He see also helion) is a light, stable isotope of helium with two protons and one neutron (the most common isotope, helium-4, having two protons and two neutrons in contrast). Other than protium (ordinary hydrogen), helium-3 is th ...

(''helions'') and tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus ...

(''tritons'').

Oliphant used electromagnetic separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" ...

to separate the isotopes of lithium. He was the first to experimentally demonstrate nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifest ...

. He found that when deuterons reacted with nuclei of helium-3, tritium or with other deuterons, the particles that were released had far more energy than they started with. Binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly us ...

had been liberated from inside the nucleus. Following Arthur Eddington

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He was also a philosopher of science and a populariser of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the lum ...

's 1920 prediction that energy released by fusing small nuclei together could provide the energy source that powers the stars, Oliphant speculated that nuclear fusion reactions might be what powered the sun. With its higher cross section, the deuterium–tritium nuclear fusion reaction became the basis of a hydrogen bomb. Oliphant had not foreseen this development:

In 1934, Cockcroft arranged for Oliphant to become a fellow of St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corporation established by a charter dated 9 April 1511. Th ...

, which paid about £600 a year. When Chadwick left the Cavendish Laboratory for the University of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

in 1935, Oliphant and Ellis both replaced him as Rutherford's assistant director for research. The job came with a salary of £600 (). With the money from St John's, this gave him a comfortable income. Oliphant soon fitted out a new accelerator laboratory with a 1.23 MeV

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. ...

generator at a cost of £6,000 () while he designed an even larger 2 MeV generator. He was the first to conceive of the proton synchrotron

A synchrotron is a particular type of cyclic particle accelerator, descended from the cyclotron, in which the accelerating particle beam travels around a fixed closed-loop path. The magnetic field which bends the particle beam into its closed p ...

, a new type of cyclic particle accelerator. In 1937, he was elected to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

. When he died he was its longest-serving fellow.

University of Birmingham

Samuel Walter Johnson Smith Samuel Walter Johnson Smith FRS (26 January 1871 - 20 August 1948) was an English physicist.

He studied Natural Sciences at Trinity College, Cambridge and became Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham in 1919, where he succeeded J ...

's imminent mandatory retirement at age 65 prompted a search for a new Poynting Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university located in Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingha ...

. The university wanted not just a replacement, but a well-known name, and was willing to spend lavishly in order to build up nuclear physics expertise at Birmingham. Neville Moss, its Professor of Mining Engineering

Mining in the engineering discipline is the extraction of minerals from underneath, open pit, above or on the ground. Mining engineering is associated with many other disciplines, such as mineral processing, exploration, excavation, geology, and ...

and the Dean of its Faculty of Science approached Oliphant, who presented his terms. In addition to his salary of £1,300 (), he wanted the university to spend £2,000 () to upgrade the laboratory, and another £1,000 per annum () on it. And he did not wish to start until October 1937, to enable him to wrap up his work at the Cavendish Laboratory. Moss agreed to Oliphant's terms.

To obtain funding for the cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: J ...

that he wanted, Oliphant wrote to the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasem ...

, who was from Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

. Chamberlain took up the matter with his friend Lord Nuffield

William Richard Morris, 1st Viscount Nuffield, (10 October 1877 – 22 August 1963) was an English motor manufacturer and philanthropist. He was the founder of Morris Motors Limited and is remembered as the founder of the Nuffield Foundation, ...

, who provided £60,000 () for the project, enough for the cyclotron, a new building to house it, and a trip to Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emer ...

, so Oliphant could confer with Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

, the inventor of the cyclotron. Lawrence supported the project, sending Oliphant the plans of the cyclotron that he was constructing at Berkeley, and inviting Oliphant to visit him at the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

. Oliphant sailed for New York on 10 December 1938, and met Lawrence in Berkeley. The two men got along very well, dining at ''Trader Vic's

Trader Vic's is a restaurant and tiki bar chain headquartered in Emeryville, California, United States. Victor Jules Bergeron, Jr. (December 10, 1902 in San Francisco – October 11, 1984 in Hillsborough, California) founded a chain of Poly ...

'' in Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

. Oliphant was aware of the problems in building cyclotrons encountered by Chadwick at the University of Liverpool and Cockcroft at the Cavendish Laboratory, and intended to avoid these and get his cyclotron built on time and on budget by following Lawrence's specifications as closely as possible. He hoped that it would be running by Christmas 1939, but the outbreak of the Second World War quashed his hopes. The Nuffield Cyclotron would not be completed until after the war.

Radar

In 1938, Oliphant became involved with the development of

In 1938, Oliphant became involved with the development of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

, then still a secret. While visiting prototype radar stations, he realised that shorter-wavelength radio waves

Radio waves are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies of 300 gigahertz ( GHz) and below. At 300 GHz, the corresponding wavelength is 1 mm (s ...

were needed urgently, especially if there was to be any chance of building a radar set small enough to fit into an aircraft. In August 1939, he took a small group to Ventnor

Ventnor () is a seaside resort and civil parish established in the Victorian era on the southeast coast of the Isle of Wight, England, from Newport. It is situated south of St Boniface Down, and built on steep slopes leading down to the sea. ...

, on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

, to examine the Chain Home

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal Early Warning radar stations built by the Royal Air Force (RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given th ...

system first hand. He obtained a grant from the Admiralty to develop radar systems with wavelengths less than ; the best available at the time was .

Oliphant's group at Birmingham worked on developing two promising devices, the klystron

A klystron is a specialized linear-beam vacuum tube, invented in 1937 by American electrical engineers Russell and Sigurd Varian,Pond, Norman H. "The Tube Guys". Russ Cochran, 2008 p.31-40 which is used as an amplifier for high radio frequen ...

and the magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field whil ...

. Working with James Sayers

James Sayers (or Sayer) (1748 – April 20, 1823) was an English caricaturist . Many of his works are described in the Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum which h ...

, Oliphant managed to produce an improved version of the klystron capable of generating 400W. Meanwhile, two more members of his Birmingham team, John Randall and Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biography

...

, worked on a radical new design, a cavity magnetron. By February 1940, they had an output of 400W with a wavelength of , just the kind of short wavelengths needed for good airborne radars. The magnetron's power was soon increased a hundred-fold, and Birmingham concentrated on magnetron development. The first operational magnetrons were delivered in August 1941. This invention was one of the key scientific breakthroughs during the war and played a major part in defeating the German U-boats

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

, intercepting enemy bombers, and in directing Allied bombers.

In 1940, the Fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wo ...

, and the possibility that Britain might be invaded, prompted Oliphant to send his wife and children to Australia. The Fall of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire of ...

in February 1942 led him to offer his services to John Madsen, the Professor of Electrical Engineering at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public university, public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one o ...

, and the head of the Radiophysics Laboratory at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) is South Africa's central and premier scientific research and development organisation. It was established by an act of parliament in 1945 and is situated on its own campus in the cit ...

, which was responsible for developing radar. He embarked from Glasgow for Australia on on 20 March. The voyage, part of a 46-ship convoy, was a slow one, with the convoy frequently zigzagging to avoid U-boats, and the ship did not reach Fremantle until 27 May.

The Australians were already preparing to produce radar sets locally. Oliphant persuaded Professor Thomas Laby

Thomas Howell Laby FRS (3 May 1880 – 21 June 1946), was an Australian physicist and chemist, Professor of Natural Philosophy, University of Melbourne 1915–1942. Along with George Kaye, he was one of the founding editors of the reference bo ...

to release Eric Burhop

Eric Henry Stoneley Burhop, (31 January 191122 January 1980) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne, Burhop was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship to study at the Cavendish Laboratory under ...

and Leslie Martin

Sir John Leslie Martin (17 August 1908, in Manchester – 28 July 2000) was an English architect, and a leading advocate of the International Style. Martin's most famous building is the Royal Festival Hall. His work was especially influenced b ...

from their work on optical munitions to work on radar, and they succeeded in building a cavity magnetron in their laboratory at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb n ...

in May 1942. Oliphant worked with Martin on the process of moving the magnetrons for the laboratory to the production line. Over 2,000 radar sets were produced in Australia during the war.

Manhattan Project

At the University of Birmingham in March 1940,Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

and Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied ...

examined the theoretical issues involved in developing, producing and using atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s in a paper that became known as the Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant at ...

. They considered what would happen to a sphere of pure uranium-235, and found that not only could a chain reaction

A chain reaction is a sequence of reactions where a reactive product or by-product causes additional reactions to take place. In a chain reaction, positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events.

Chain reactions are one way that sy ...

occur, but it might require as little as of uranium-235 to unleash the energy of hundreds of tons of TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reage ...

. The first person they showed their paper to was Oliphant, and he immediately took it to Sir Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the ...

, the chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Warfare (CSSAW). As a result, a special subcommittee of the CSSAW known as the MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram fro ...

was created to investigate the matter further. It was chaired by Sir George Thomson, and its original membership included Oliphant, Chadwick, Cockcroft and Moon. In its final report in July 1941, the MAUD Committee concluded that an atomic bomb was not only feasible, but might be produced as early as 1943.

Great Britain was at war and authorities there thought that the development of an atomic bomb was urgent, but there was much less urgency in the United States. Oliphant was one of the people who pushed the American program into motion. On 5 August 1941, Oliphant flew to the United States in a

Great Britain was at war and authorities there thought that the development of an atomic bomb was urgent, but there was much less urgency in the United States. Oliphant was one of the people who pushed the American program into motion. On 5 August 1941, Oliphant flew to the United States in a B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models d ...

bomber, ostensibly to discuss the radar-development program, but was assigned to find out why the United States was ignoring the findings of the MAUD Committee. He later recalled: "the minutes and reports had been sent to Lyman Briggs

Lyman James Briggs (May 7, 1874 – March 25, 1963) was an American engineer, physicist and administrator. He was a director of the National Bureau of Standards during the Great Depression and chairman of the Uranium Committee before America en ...

, who was the Director of the Uranium Committee, and we were puzzled to receive virtually no comment. I called on Briggs in Washington C only to find out that this inarticulate and unimpressive man had put the reports in his safe and had not shown them to members of his committee. I was amazed and distressed."

Oliphant then met with the Uranium Committee at its meeting in New York on 26 August 1941. Samuel K. Allison, a new member of the committee, was an experimental physicist and a protégé of Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

. He recalled that Oliphant "came to a meeting and said 'bomb' in no uncertain terms. He told us we must concentrate every effort on the bomb, and said we had no right to work on power plants or anything but the bomb. The bomb would cost 25 million dollars, he said, and Britain did not have the money or the manpower, so it was up to us." Allison was surprised that Briggs had kept the committee in the dark. Oliphant then travelled to Berkeley, where he met his friend Lawrence on 23 September, giving him a copy of the Frisch–Peierls memorandum. Lawrence had Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

check the figures, bringing him into the project for the first time. Oliphant found another ally in Oppenheimer, and he not only managed to convince Lawrence and Oppenheimer that an atomic bomb was feasible, but inspired Lawrence to convert his cyclotron into a giant mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is u ...

for electromagnetic isotope separation

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derived ...

, a technique Oliphant had pioneered in 1934. Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

later wrote, "if Congress knew the true history of the atomic energy project, I have no doubt but that it would create a special medal to be given to meddling foreigners for distinguished services, and that Dr Oliphant would be the first to receive one."

On 26 October 1942, Oliphant embarked from Melbourne, taking Rosa and the children back with him. The wartime sea voyage on the French ''Desirade'' was again a slow one, and they did not reach Glasgow until 28 February 1943. He had to leave them behind once more in November 1943 after the British

On 26 October 1942, Oliphant embarked from Melbourne, taking Rosa and the children back with him. The wartime sea voyage on the French ''Desirade'' was again a slow one, and they did not reach Glasgow until 28 February 1943. He had to leave them behind once more in November 1943 after the British Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

effort was merged with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

by the Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

, and he left for the United States as part of the British Mission. Oliphant was one of the scientists whose services the Americans were most eager to secure. Oppenheimer, who was now the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Rob ...

attempted to persuade him to join the team there, but Oliphant preferred to head a team assisting his friend Lawrence at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley to develop the electromagnetic uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

—a vital but less overtly military part of the project.

Oliphant secured the services of fellow Australian physicist Harrie Massey

Sir Harrie Stewart Wilson Massey (16 May 1908 – 27 November 1983) was an Australian mathematical physicist who worked primarily in the fields of atomic and atmospheric physics.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne and Cambridge Unive ...

, who had been working for the Admiralty on magnetic mines

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any v ...

, along with James Stayers and Stanley Duke, who had worked with him on the cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field ...

. This initial group set out for Berkeley in a B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models d ...

bomber in November 1943. Oliphant became Lawrence's ''de facto'' deputy, and was in charge of the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory when Lawrence was absent. Although based in Berkeley, he often visited Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. O ...

, where the separation plant was, and was an occasional visitor to Los Alamos. He made efforts to involve Australian scientists in the project, and had Sir David Rivett

Sir Albert Cherbury David Rivett, KCMG (4 December 1885 – 1 April 1961) was an Australian chemist and science administrator.

Background and education

Rivett was born at Port Esperance, Tasmania, Australia, a son of the Rev. Albert Rivett ( ...

, the head of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, release Eric Burhop to work on the Manhattan Project. He briefed Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929, as leader of the Nationalist Party.

Bor ...

, the Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, on the project, and urged the Australian government to secure Australian uranium deposits.

A meeting with Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

, the director of the Manhattan Project, at Berkeley in September 1944, convinced Oliphant that the Americans intended to monopolise nuclear weapons after the war, restricting British research and production to Canada, and not permitting nuclear weapons technology to be shared with Australia. Characteristically, Oliphant bypassed Chadwick, the head of the British Mission, and sent a report direct to Wallace Akers

Sir Wallace Alan Akers (9 September 1888 – 1 November 1954) was a British chemist and industrialist. Beginning his academic career at Oxford he specialized in physical chemistry. During the Second World War, he was the director of the Tube Al ...

, the head of the Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

Directorate in London. Akers summoned Oliphant back to London for consultation. En route, Oliphant met with Chadwick and other members of the British Mission in Washington, where the prospect of resuming an independent British project was discussed. Chadwick was adamant that the cooperation with the Americans should continue, and that Oliphant and his team should remain until the task of building an atomic bomb was finished. Akers sent Chadwick a telegram directing that Oliphant should return to the UK by April 1945.

Oliphant returned to England in March 1945, and resumed his post as a professor of physics at the University of Birmingham. He was on holiday in Wales with his family when he first heard of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

. He was later to remark that he felt "sort of proud that the bomb had worked, and absolutely appalled at what it had done to human beings". Oliphant became a harsh critic of nuclear weapons and a member of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs is an international organization that brings together scholars and public figures to work toward reducing the danger of armed conflict and to seek solutions to global security threats. It was ...

, saying, "I, right from the beginning, have been terribly worried by the existence of nuclear weapons and very much against their use." His wartime work would have earned him a Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

with Gold Palm, but the Australian government vetoed this honour, as government policy at the time was not to confer honours on civilians.

Later years in Australia

In April 1946, thePrime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follo ...

, asked Oliphant if he would be a technical advisor to the Australian delegation to the newly formed United Nations Atomic Energy Commission The United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) was founded on 24 January 1946 by the very first resolution of the United Nations General Assembly "to deal with the problems raised by the discovery of atomic energy."

The General Assembly asked ...

(UNAEC), which was debating international control of nuclear weapons. Oliphant agreed, and joined the Minister for External Affairs, H. V. Evatt

Herbert Vere Evatt, (30 April 1894 – 2 November 1965) was an Australian politician and judge. He served as a judge of the High Court of Australia from 1930 to 1940, Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs from 1941 to 1949, and le ...

and the Australian Representative at the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

, Paul Hasluck

Sir Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck, (1 April 1905 – 9 January 1993) was an Australian statesman who served as the 17th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1969 to 1974. Prior to that, he was a Liberal Party politician, holding min ...

, to hear the Baruch Plan. The attempt at international control was unsuccessful, and no agreement was reached.

Chifley and the Secretary for Post-War Reconstruction, Dr H. C. "Nugget" Coombs, also discussed with Oliphant a plan to create a new research institute that would attract the world's best scholars to Australia and lift the standard of university education nationwide. They hoped to start by attracting three of Australia's most distinguished expatriates: Oliphant, Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (24 September 189821 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role ...

and Keith Hancock. It was academic suicide; Australia was far from the centres where the latest research was being carried out, and communications were much poorer at that time. But Oliphant accepted, and in 1950 returned to Australia as the first Director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering

The Research School of Physics (RSPhys) was established with the creation of the Australian National University (ANU) in 1947. Located at the ANU's main campus in Canberra, the school is one of the four founding research schools in the ANU's In ...

at the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

. Within the school he created a Department of Particle Physics, which he headed himself, a Department of Nuclear Physics under Ernest Titterton

Sir Ernest William Titterton (4 March 1916 – 8 February 1990) was a British nuclear physicist.

A graduate of the University of Birmingham, Titterton worked in a research position under Mark Oliphant, who recruited him to work on radar ...

, a Department of Geophysics under John Jaeger, a Department of Astronomy under Bart Bok

Bartholomeus Jan "Bart" Bok (April 28, 1906 – August 5, 1983) was a Dutch-American astronomer, teacher, and lecturer. He is best known for his work on the structure and evolution of the Milky Way galaxy, and for the discovery of Bok globules, ...

, a Department of Theoretical Physics under Kenneth Le Couteur and a Department of Mathematics under Bernhard Neumann

Bernhard Hermann Neumann (15 October 1909 – 21 October 2002) was a German-born British-Australian mathematician, who was a leader in the study of group theory.

Early life and education

After gaining a D.Phil. from Friedrich-Wilhelms Universi ...

.

Oliphant was an advocate of nuclear weapons research. He served on the post-war Technical Committee that advised the British government on nuclear weapons, and publicly declared that Britain needed to develop its own nuclear weapons independent of the United States to "avoid the danger of becoming a lesser power". The establishment of a world-class nuclear physics research capability in Australia was intimately linked with the government's plans to develop nuclear power and weapons. Locating the new research institute in Canberra would place it close to the

Oliphant was an advocate of nuclear weapons research. He served on the post-war Technical Committee that advised the British government on nuclear weapons, and publicly declared that Britain needed to develop its own nuclear weapons independent of the United States to "avoid the danger of becoming a lesser power". The establishment of a world-class nuclear physics research capability in Australia was intimately linked with the government's plans to develop nuclear power and weapons. Locating the new research institute in Canberra would place it close to the Snowy Mountains Scheme

The Snowy Mountains Scheme or Snowy scheme is a hydroelectricity and irrigation complex in south-east Australia. The Scheme consists of sixteen major dams; nine power stations; two pumping stations; and of tunnels, pipelines and aqueducts that ...

, which was planned to be the centrepiece of a new nuclear power industry. Oliphant hoped that Britain would assist with the Australian program, and the British were interested in cooperation because Australia had uranium ore and weapons testing sites, and there were concerns that Australia was becoming too closely aligned with the United States. Arrangements were made for Australian scientists to be seconded to the British Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned and funded by the British Governm ...

at Harwell, but the close cooperation he sought was stymied by security concerns arising from Britain's commitments to the United States.

Oliphant envisaged Canberra one day becoming a university town

A college town or university town is a community (often a separate town or city, but in some cases a town/city neighborhood or a district) that is dominated by its university population. The university may be large, or there may be several sma ...

like Oxford or Cambridge. A threat to the future of the university arose in the wake of the 1949 election, when the Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Aus ...

led by Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

won. Many Liberals were opposed to the university, which they saw as an extravagance. Menzies defended it, but in 1954 he announced that it had entered a period of consolidation, with a funding ceiling, ending the possibility of successful competition with universities in Europe and North America. A further blow came in 1959, when the Menzies government

Menzies is a Scottish surname, with Gaelic forms being Méinnearach and Méinn, and other variant forms being Menigees, Mennes, Mengzes, Menzeys, Mengies, and Minges.

Derivation and history

The name and its Gaelic form are probably derived f ...

amalgamated it with the Canberra University College

Canberra University College was a tertiary education institution established in Canberra by the Australian government and the University of Melbourne in 1930. At first it operated in the Telopea Park School premises after hours. Most of the init ...

. Henceforth, it would no longer be a research university, but a regular one, with responsibility for teaching undergraduates. Nonetheless, parts of the university stayed committed to the old mission, and the ANU remained a university where research is central to its activities. Despite the setbacks, by 2014 the vision of Canberra as a university town would be well on its way to becoming a reality.

In September 1951, Oliphant applied for a visa to travel to the United States for a nuclear physics conference in Chicago. The visa was not refused, nor was Oliphant accused of subversive activities, but neither was it issued. This was the height of the Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which a ...

. The American McCarran Act

The Internal Security Act of 1950, (Public Law 81-831), also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, the McCarran Act after its principal sponsor Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nevada), or the Concentration Camp Law, is a United States fede ...