Luigi Sturzo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

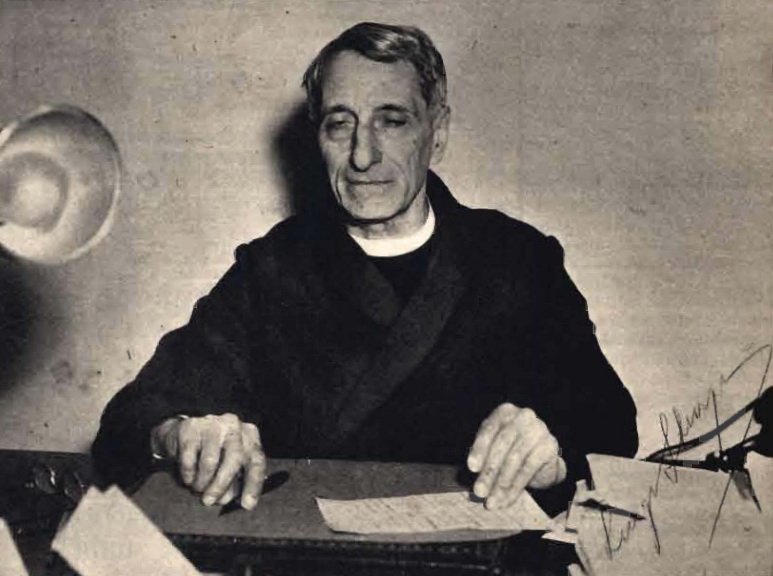

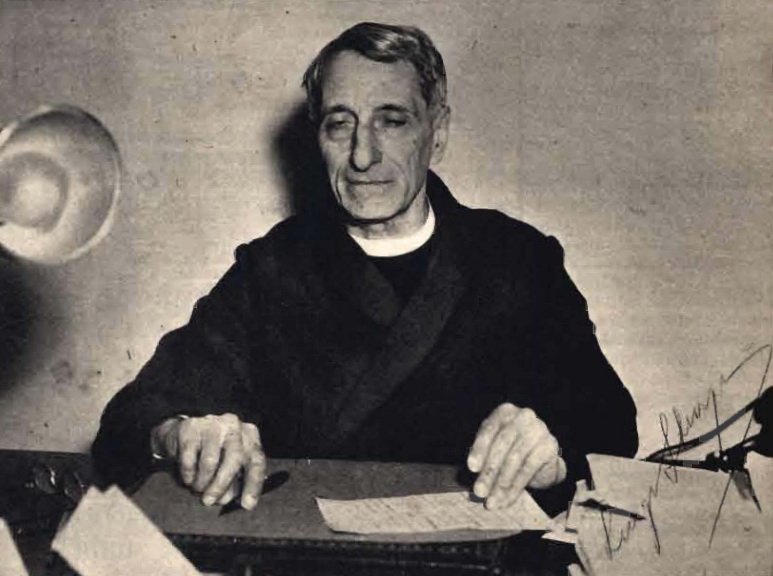

Luigi Sturzo (; 26 November 1871 – 8 August 1959) was an Italian

Sturzo was among the founders of the Partito Popolare Italiano on 19 January 1919. The formation of the PPI - with the permission of

Sturzo was among the founders of the Partito Popolare Italiano on 19 January 1919. The formation of the PPI - with the permission of

Sturzo set off to return to his homeland on the ''Vulcania'' on 27 August 1946 (after the June Referendum had abolished the need for a monarch) but did not have a dominant role in Italian politics after his arrival on 6 September in

Sturzo set off to return to his homeland on the ''Vulcania'' on 27 August 1946 (after the June Referendum had abolished the need for a monarch) but did not have a dominant role in Italian politics after his arrival on 6 September in

online

*Farrell-Vinay, Giovanna. 2004. "The London Exile of Don Luigi Sturzo (1924-1940)." ''HeyJ''. XLV, pp. 158–177. * Molony, John N. ''The emergence of political catholicism in Italy: Partito popolare 1919-1926'' (1977) *Moos, Malcolm. 1945. "Don Luigi Sturzo--Christian Democrat." ''The American Political Science Review'', 39#2 269-292. * Murphy, Francis J. "Don Sturzo and the Triumph of Christian Democracy." ''Italian Americana'' 7.1 (1981): 89-98

online

*Pugliese, Stanislao G. 2001. ''Italian Fascism and Anti-Fascism: A Critical Anthology''. Manchester University Press. *Riccards, Michael P. ''Vicars of Christ: Popes, Power, and Politics in the Modern World''. New York: Herder & Herder. * Schäfer, Michael. "Luigi Sturzo as a theorist of totalitarianism." ''Totalitarianism and Political Religions,'' Volume 1. Routledge, 2004. 39-57.

Catholic Culture

(1938) {{DEFAULTSORT:Sturzo, Luigi 1871 births 1959 deaths 20th-century Italian politicians 20th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests 20th-century venerated Christians Italian anti-communists Italian anti-fascists Italian life senators Italian newspaper founders Italian People's Party (1919) politicians Italian Servants of God People from Caltagirone Italian political party founders Politicians of Catholic political parties Politicians from the Province of Catania Pontifical Gregorian University alumni Exiled Italian politicians Religious leaders from the Province of Catania Italian Christian socialists

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

and prominent politician. He was known in his lifetime as a "clerical

Clerical may refer to:

* Pertaining to the clergy

* Pertaining to a clerical worker

* Clerical script, a style of Chinese calligraphy

* Clerical People's Party

See also

* Cleric (disambiguation)

Cleric is a member of the clergy.

Cleric may al ...

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

" and is considered one of the fathers of the Christian democratic platform. He was also the founder of the Luigi Sturzo Institute Luigi Sturzo Institute was founded in 1951 by Luigi Sturzo

of the Partito Popolare (Italian Popular Party). The mission of The Luigi Sturzo Institute is to endorse research in the historical sciences, sociology, political and economical fields by ...

in 1951. Sturzo was one of the founders of the Italian People's Party in 1919, but was forced into exile in 1924 with the rise of Italian fascism, and later the post-war Christian Democrats. In exile in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

(and later New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

) he published over 400 articles (published after his death under the title ''Miscellanea Londinese'') critical of fascism.

Sturzo's cause for canonization opened on 23 March 2002 and he is titled as a Servant of God

"Servant of God" is a title used in the Catholic Church to indicate that an individual is on the first step toward possible canonization as a saint.

Terminology

The expression "servant of God" appears nine times in the Bible, the first five in ...

.

Life

Priesthood

Luigi Sturzo was born on 26 November 1871 inCaltagirone

Caltagirone (; scn, Caltaggiruni ; Latin: ''Calata Hieronis'') is an inland city and '' comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Catania, on the island (and region) of Sicily, southern Italy, about southwest of Catania. It is the fifth most popul ...

to Felice Sturzo and Caterina Boscarelli. His twin sister was Emanuela (also known as Nelina). One ancestor - Giuseppe Sturzo - served as the Mayor of Caltagirone in 1864 until an unspecified time and another ancestor was Croce Sturzo who wrote about the Roman Question. His two brothers Luigi and Franco Sturzo were well-known Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

. His elder brother Mario (1 November 1861 – 11 November 1941) was a noted theologian and Bishop of Piazza Armerina

The Italian Catholic diocese of Piazza Armerina ( la, Dioecesis Platiensis) is in Sicily. It is a suffragan of the archdiocese of Agrigento.

History

The diocese of Piazza Armerina was taken from the diocese of Catania, and was created in 18 ...

. His two other sisters were Margherita and the nun Remigia (or Sister Giuseppina).

From 1883 until 1886 he studied at Acireale and then in Noto. He commenced his studies for the ecclesial life in 1888.

Sturzo received his ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

to the priesthood on 19 May 1894 from the Bishop of Caltagirone Saverio Gerbino (at the Chiesa del Santissimo Salvatore) and following his graduation served as a teacher of philosophical and theological studies in Caltagirone; he served as his town's Vice-Mayor from 1905 to 1920. In 1898 he received a doctorate in his philosophical studies from the Pontifical Gregorian in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in 1898 and he taught that subject in his hometown from 1898 to 1903. It was around this time that he knew Giacomo Radini-Tedeschi

Giacomo Maria Radini-Tedeschi (12 July 1857 - 22 August 1914) was the Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Bergamo. Today he is famous for his strong involvement in social issues at the beginning of 20th century.

Biography

Radini-Tedeschi w ...

.

In his spare time he liked to collect antique ceramic art and while serving as the Vice-Mayor opened a ceramicists' school in 1918. He also founded the newspaper ''La Croce di Constantino'' in Caltagirone in 1897. In 1900 - at the same time as the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

- Sturzo asked his bishop to serve in the missions in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

despite the persecutions the Church was enduring there. But he was denied this request on the account of his precarious state of health. Sturzo also was involved since 1915 with Azione Cattolica. He was also close with Romolo Murri.

Sturzo's political activism and collaboration with his colleagues prevented Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A p ...

assuming power once again in 1922 which allowed for Luigi Facta

Luigi Facta (16 November 1861 – 5 November 1930) was an Italian politician, lawyer and journalist and the last Prime Minister of Italy before the leadership of Benito Mussolini.

Background and earlier career

Facta was born in Pinerolo, Piedm ...

to assume the prime ministership.

Italian Popular Party

Sturzo was among the founders of the Partito Popolare Italiano on 19 January 1919. The formation of the PPI - with the permission of

Sturzo was among the founders of the Partito Popolare Italiano on 19 January 1919. The formation of the PPI - with the permission of Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (Ecclesiastical Latin, Latin: ''Benedictus XV''; it, Benedetto XV), born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, name=, group= (; 21 November 185422 January 1922), was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his deat ...

- represented a tacit and reluctant reversal of the Vatican's ''Non Expedit

(Latin for "It is not expedient") were the words with which the Holy See enjoined upon Italian Catholics the policy of boycott from the polls in parliamentary elections.

History

The phrase, "it is not expedient," has long been used by the Roman ...

'' of non-participation in Italian politics which was abolished before the November 1919 elections in which the PPI won 20.6% of the vote and 100 seats in the legislature. The PPI was a colossal political force in the nation: between 1919 and 1922 no government could be formed and maintained without the support of the PPI. But a coalition between the Socialists and the PPI was deemed unacceptable within the Vatican despite the Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A p ...

in 1914 proposing it and something his progressive and powerless successors— Bonomi (1921-1922) and Facta (1922)—reimaged as the single possible coalition that excluded the Fascists.

Sturzo was a committed anti-fascist who discussed the ways in which Catholicism and Fascism were incompatible in such works as ''Coscienza cristiana'' and criticized what he perceived to be " filo-fascist" elements within the Vatican. Sturzo also wrote about the thought of Saint Augustine of Hippo and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz as well as Giambattista Vico and Maurice Blondel. He did this in order to elaborate on what he called the "dialectic of the concrete" and opposed this dialectic as a veer towards absolute idealism

Absolute idealism is an ontologically monistic philosophy chiefly associated with G. W. F. Hegel and Friedrich Schelling, both of whom were German idealist philosophers in the 19th century. The label has also been attached to others such as Jos ...

and scholastic realism.

Sturzo was not among the 14 PPI members who defected—under pressure from Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City f ...

—to approve the Acerbo Law in July 1923. Sturzo was forced to resign as the General Secretary of the PPI on 10 July 1923 (he had served as such since 1919) after being unable to obtain the support of the Vatican to continue to oppose Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

and his regime. He further resigned from the board on 19 May 1924. After Sturzo's departure the Vatican endorsed the formation of the '' Unione Nazionale'' which was pro-fascist and Catholic which hastened the rupture of the PPI and provided political cover for its former members to join Mussolini’s inaugural government. Following the Matteotti affair

Giacomo Matteotti (; 22 May 1885 – 10 June 1924) was an Italian Socialism, socialist politician. On 30 May 1924, he openly spoke in the Parliament of Italy, Italian Parliament alleging the National Fascist Party, Fascists committed fraud in ...

(after which Sturzo thought the Aventine Secession should return to Parliament) Cardinal Pietro Gasparri

Pietro Gasparri, GCTE (5 May 1852 – 18 November 1934) was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV a ...

acceded to the wishes of Mussolini and forced Sturzo to leave the Italian nation before the re-opening of Parliament commemorating the March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 192 ...

.

Exile

Sturzo was exiled from 1924 to 1946 first inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

(1924–40) and then in the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

(1940–46). Sturzo left Rome for London on 25 October 1924. Sturzo was consigned to a 3-month educational trip in London; but the choice of London was perhaps intended to isolate Sturzo because he did not speak the language and it did not contain a large population of like-minded Catholics. He moved to the residence of the Oblates of Saint Charles in Bayswater

Bayswater is an area within the City of Westminster in West London. It is a built-up district with a population density of 17,500 per square kilometre, and is located between Kensington Gardens to the south, Paddington to the north-east, an ...

and then in January 1925 to the Servites at their priory of Saint Mary in Fulham Road

Fulham Road is a street in London, England, which comprises the A304 and part of the A308.

Overview

Fulham Road ( the A219) runs from Putney Bridge as "Fulham High Street" and then eastward to Fulham Broadway, in the London Borough of Hamme ...

where he was asked to leave in 1926 because the Servites' motherhouse in Rome was being denied funds as long as Sturzo was their guest.

In 1926 he refused an offer from the Vatican - communicated through Cardinal Francis Bourne - to serve as a chaplain in a convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Angl ...

in Chiswick

Chiswick ( ) is a district of west London, England. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth; Chiswick House, a neo-Palladian villa regarded as one of the finest in England; and F ...

and lodging for his twin sister Nelina in exchange for ending his journalistic activism and issuing a "spontaneous declaration" that he was retired from politics in full. Instead in November 1926 he moved into a flat at 213b Gloucester Terrace in Bayswater with his sister where the pair lived as lodgers until 1933. After the signing of the Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty ( it, Patti Lateranensi; la, Pacta Lateranensia) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settl ...

in 1929 he was offered an appointment as a Canon of Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal ...

in Rome again in exchange for his permanent renunciation of politics.

On 22 September 1940 he boarded the ''Samaria'' in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

bound for New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

hoping for an academic appointment and arrived there on 3 October. But he was instead sent to Saint Vincent's Hospital in Jacksonville

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

which was filled with priests who were ill and about to die. Beginning in 1941 he cooperated with agents from the British Security Co-Ordination as well as the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

and the Office of War Information

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a United States government agency created during World War II. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and othe ...

providing them with his assessments of the political forces with the Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Socia ...

and radio broadcasts to the Italian peninsula. Sturzo returned to Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

in April 1944 but his return to his homeland received a Vatican- Alcide De Gasperi veto in October 1945 and May 1946. De Gasperi with Sturzo on the scope of a referendum to abolish the monarch as the head of state.

Return and death

Sturzo set off to return to his homeland on the ''Vulcania'' on 27 August 1946 (after the June Referendum had abolished the need for a monarch) but did not have a dominant role in Italian politics after his arrival on 6 September in

Sturzo set off to return to his homeland on the ''Vulcania'' on 27 August 1946 (after the June Referendum had abolished the need for a monarch) but did not have a dominant role in Italian politics after his arrival on 6 September in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

. He instead retired to the outskirts of Rome after landing in Naples. In 1951 he founded the Luigi Sturzo Institute Luigi Sturzo Institute was founded in 1951 by Luigi Sturzo

of the Partito Popolare (Italian Popular Party). The mission of The Luigi Sturzo Institute is to endorse research in the historical sciences, sociology, political and economical fields by ...

which was designed to endorse research in historical science as well as in economics and politics. He was made a Senator on 17 December 1952 and Senator for life

A senator for life is a member of the senate or equivalent upper chamber of a legislature who has life tenure. , six Italian senators out of 206, two out of the 41 Burundian senators, one Congolese senator out of 109, and all members of the B ...

in 1953 at the behest of President Luigi Einaudi and he obtained a dispensation from Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

in order to accept the title.

On 23 July 1959 he celebrated Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

and when he came to the consecration of the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

he looked down and slumped. He was carried to his bed still in his vestments and his health took a sharp decline until his death. Sturzo died in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in the afternoon of 8 August 1959 at the general house of the Canossians

The Canossians are a family of two Catholic religious institutes and three affiliated lay associations that trace their origin to Magdalen of Canossa, a religious sister canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1988.

Canossian family Canossian Daughte ...

; his remains were interred in the church of San Lorenzo al Verano but were transferred in 1962 to the church of Santissimo Salvatore in Caltagirone.

Beatification cause

The beatification process for Sturzo opened underPope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

on 23 March 2002 after the Congregation for the Causes of Saints issued the official " nihil obstat" decree and titled the priest as a Servant of God

"Servant of God" is a title used in the Catholic Church to indicate that an individual is on the first step toward possible canonization as a saint.

Terminology

The expression "servant of God" appears nine times in the Bible, the first five in ...

. Cardinal Camillo Ruini inaugurated the diocesan process of investigation on 3 May 2002. The diocesan process concluded on 24 November 2017 in the Lateran Palace

The Lateran Palace ( la, Palatium Lateranense), formally the Apostolic Palace of the Lateran ( la, Palatium Apostolicum Lateranense), is an ancient palace of the Roman Empire and later the main papal residence in southeast Rome.

Located on St. ...

.

Recent reports indicate - as of August 2017 - that the beatification cause is gaining greater momentum and is close to a conclusion that would see Sturzo named as Venerable

The Venerable (''venerabilis'' in Latin) is a style, a title, or an epithet which is used in some Western Christian churches, or it is a translation of similar terms for clerics in Eastern Orthodoxy and monastics in Buddhism.

Christianity

Cat ...

.

The current postulator

A postulator is the person who guides a cause for beatification or canonization through the judicial processes required by the Roman Catholic Church. The qualifications, role and function of the postulator are spelled out in the ''Norms to be Obse ...

for this cause is Avv. Carlo Fusco.

See also

*Luigi Sturzo Institute Luigi Sturzo Institute was founded in 1951 by Luigi Sturzo

of the Partito Popolare (Italian Popular Party). The mission of The Luigi Sturzo Institute is to endorse research in the historical sciences, sociology, political and economical fields by ...

Authorship

Sturzo was the author of several works in relation to philosophical and political thought. This included: * ''Church and State'' (1939) * ''The True Life'' (1943) * ''The Inner Laws of Society'' (1944) *'' Spiritual Problems of Our Times'' (1945) * ''Italy and the Coming World'' (1945)Notes and references

Bibliography

*De Grand, Alexander. 1982. ''Italian Fascism: Its Origins & Development''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. * Delzell, Charles F. "The Emergence of Political Catholicism in Italy: Partio Popolare, 1919-1926." ''Journal of Church and State'' (1980) 22#3: 543-546.online

*Farrell-Vinay, Giovanna. 2004. "The London Exile of Don Luigi Sturzo (1924-1940)." ''HeyJ''. XLV, pp. 158–177. * Molony, John N. ''The emergence of political catholicism in Italy: Partito popolare 1919-1926'' (1977) *Moos, Malcolm. 1945. "Don Luigi Sturzo--Christian Democrat." ''The American Political Science Review'', 39#2 269-292. * Murphy, Francis J. "Don Sturzo and the Triumph of Christian Democracy." ''Italian Americana'' 7.1 (1981): 89-98

online

*Pugliese, Stanislao G. 2001. ''Italian Fascism and Anti-Fascism: A Critical Anthology''. Manchester University Press. *Riccards, Michael P. ''Vicars of Christ: Popes, Power, and Politics in the Modern World''. New York: Herder & Herder. * Schäfer, Michael. "Luigi Sturzo as a theorist of totalitarianism." ''Totalitarianism and Political Religions,'' Volume 1. Routledge, 2004. 39-57.

External links

Catholic Culture

(1938) {{DEFAULTSORT:Sturzo, Luigi 1871 births 1959 deaths 20th-century Italian politicians 20th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests 20th-century venerated Christians Italian anti-communists Italian anti-fascists Italian life senators Italian newspaper founders Italian People's Party (1919) politicians Italian Servants of God People from Caltagirone Italian political party founders Politicians of Catholic political parties Politicians from the Province of Catania Pontifical Gregorian University alumni Exiled Italian politicians Religious leaders from the Province of Catania Italian Christian socialists