Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten Of Burma on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of

While still an acting- sub-lieutenant, Mountbatten was appointed

While still an acting- sub-lieutenant, Mountbatten was appointed  Mountbatten was posted to the battlecruiser in March 1920 and accompanied Edward, Prince of Wales, on a royal tour of Australia in her. He was promoted

Mountbatten was posted to the battlecruiser in March 1920 and accompanied Edward, Prince of Wales, on a royal tour of Australia in her. He was promoted

When war broke out in September 1939, Mountbatten became Captain (D) (commander) of the

When war broke out in September 1939, Mountbatten became Captain (D) (commander) of the  In August 1941, Mountbatten was appointed captain of the aircraft carrier which lay in Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs following action at Malta in January. During this period of relative inactivity, he paid a flying visit to

In August 1941, Mountbatten was appointed captain of the aircraft carrier which lay in Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs following action at Malta in January. During this period of relative inactivity, he paid a flying visit to  Mountbatten was a favourite of

Mountbatten was a favourite of  As commander of Combined Operations, Mountbatten and his staff planned the highly successful

As commander of Combined Operations, Mountbatten and his staff planned the highly successful  Mountbatten claimed that the lessons learned from the Dieppe Raid were necessary for planning the Normandy invasion on D-Day nearly two years later. However, military historians such as

Mountbatten claimed that the lessons learned from the Dieppe Raid were necessary for planning the Normandy invasion on D-Day nearly two years later. However, military historians such as  British interpreter Hugh Lunghi recounted an embarrassing episode during the

British interpreter Hugh Lunghi recounted an embarrassing episode during the

Mountbatten was fond of

Mountbatten was fond of  Given the British government's recommendations to grant independence quickly, Mountbatten concluded that a united India was an unachievable goal and resigned himself to a plan for partition, creating the independent nations of India and Pakistan. Mountbatten set a date for the transfer of power from the British to the Indians, arguing that a fixed timeline would convince Indians of his and the British government's sincerity in working towards a swift and efficient independence, excluding all possibilities of stalling the process..

Among the Indian leaders,

Given the British government's recommendations to grant independence quickly, Mountbatten concluded that a united India was an unachievable goal and resigned himself to a plan for partition, creating the independent nations of India and Pakistan. Mountbatten set a date for the transfer of power from the British to the Indians, arguing that a fixed timeline would convince Indians of his and the British government's sincerity in working towards a swift and efficient independence, excluding all possibilities of stalling the process..

Among the Indian leaders,  When India and Pakistan attained independence at midnight of 14–15 August 1947, Mountbatten was alone in his study at the Viceroy's house saying to himself just before the clock struck midnight that for still a few minutes, he was the most powerful man on Earth. At 11:58 PM, as a last act of showmanship, he created Joan Falkiner, the Australian wife of the Nawab of

When India and Pakistan attained independence at midnight of 14–15 August 1947, Mountbatten was alone in his study at the Viceroy's house saying to himself just before the clock struck midnight that for still a few minutes, he was the most powerful man on Earth. At 11:58 PM, as a last act of showmanship, he created Joan Falkiner, the Australian wife of the Nawab of  Notwithstanding the self-promotion of his own part in Indian independence – notably in the television series ''The Life and Times of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma'', produced by his son-in-law

Notwithstanding the self-promotion of his own part in Indian independence – notably in the television series ''The Life and Times of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma'', produced by his son-in-law

After India, Mountbatten served as commander of the

After India, Mountbatten served as commander of the  Mountbatten served his final posting at the Admiralty as

Mountbatten served his final posting at the Admiralty as

Mountbatten was elected a

Mountbatten was elected a

Mountbatten was married on 18 July 1922 to Edwina Cynthia Annette Ashley, daughter of Wilfred William Ashley, later 1st Baron Mount Temple, himself a grandson of the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. She was the favourite granddaughter of the Edwardian magnate Sir Ernest Cassel and the principal heir to his fortune. The couple spent heavily on households, luxuries, and entertainment. There followed a honeymoon tour of European royal courts and America which included a visit to

Mountbatten was married on 18 July 1922 to Edwina Cynthia Annette Ashley, daughter of Wilfred William Ashley, later 1st Baron Mount Temple, himself a grandson of the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. She was the favourite granddaughter of the Edwardian magnate Sir Ernest Cassel and the principal heir to his fortune. The couple spent heavily on households, luxuries, and entertainment. There followed a honeymoon tour of European royal courts and America which included a visit to

Mountbatten usually holidayed at his summer home, Classiebawn Castle, on the

Mountbatten usually holidayed at his summer home, Classiebawn Castle, on the

On 5 September 1979, Mountbatten received a ceremonial funeral at

On 5 September 1979, Mountbatten received a ceremonial funeral at

Tribute & Memorial Website to Louis, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma

70th Anniversary of Indian Independence – Mountbatten: The Last Viceroy – UK Parliament Living Heritage

*

Papers of Louis, Earl Mountbatten of Burma

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mountbatten Of Burma, Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl 1900 births 1979 deaths 1940s in British India 1979 murders in the Republic of Ireland Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Assassinated British politicians Assassinated military personnel Assassinated royalty Louis Francis British Empire in World War II British people murdered abroad British terrorism victims Burma in World War II Chief Commanders of the Legion of Merit Chiefs of the Defence Staff (United Kingdom) Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Deaths by improvised explosive device in the Republic of Ireland Earls Mountbatten of Burma English people of German descent Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) First Sea Lords and Chiefs of the Naval Staff Foreign recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States) German princes Governors-General of India Graduates of the Royal Naval College, Greenwich Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Grand Crosses of the Order of Aviz Grand Crosses of the Order of George I Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown (Romania) Grand Crosses of the Order of the Dannebrog Grand Crosses of the Order of the Star of Romania Improvised explosive device bombings in the Republic of Ireland Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Knights of Justice of the Order of St John Knights of the Garter Legion of Frontiersmen members Lord Lieutenants of the Isle of Wight Male murder victims Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Military of Singapore under British rule

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

descent, was born in the United Kingdom to the prominent Battenberg family

The Battenberg family is a non-dynastic cadet branch of the House of Hesse-Darmstadt, which ruled the Grand Duchy of Hesse until 1918. The first member was Julia Hauke, whose brother-in-law Grand Duke Louis III of Hesse created her Countess of ...

and was a maternal uncle of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from E ...

, and a second cousin of King George VI. He joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and was appointed Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir A ...

, in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. He later served as the last Viceroy of British India and briefly as the first Governor-General of the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

.

Mountbatten attended the Royal Naval College, Osborne

The Royal Naval College, Osborne, was a training college for Royal Navy officer cadets on the Osborne House estate, Isle of Wight, established in 1903 and closed in 1921.

Boys were admitted at about the age of thirteen to follow a course lasting ...

, before entering the Royal Navy in 1916. He saw action during the closing phase of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and after the war briefly attended Christ's College, Cambridge. During the interwar period, Mountbatten continued to pursue his naval career, specialising in naval communications.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Mountbatten commanded the destroyer and the 5th Destroyer Flotilla

The British 5th Destroyer Flotilla, or Fifth Destroyer Flotilla, was a naval formation of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the ...

. He saw considerable action in Norway, in the English Channel, and in the Mediterranean. In August 1941, he received command of the aircraft carrier . He was appointed chief of Combined Operations and a member of the Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the C ...

in early 1942, and organised the raids on St Nazaire and Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to N ...

. In August 1943, Mountbatten became Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia Command and oversaw the recapture of Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

from the Japanese by the end of 1945. For his service during the war, Mountbatten was created viscount in 1946 and earl the following year.

In March 1947, Mountbatten was appointed Viceroy of India and oversaw the Partition of India into India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

. He then served as the first Governor-General of India until June 1948. In 1952, Mountbatten was appointed commander-in-chief of the British Mediterranean Fleet and NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

Commander Allied Forces Mediterranean

Allied Forces Mediterranean was a NATO command covering all military operations in the Mediterranean Sea from 1952 to 1967. The command was based at Malta.

History

The British post of Commander in Chief Mediterranean Fleet was given a dual-hatte ...

. From 1955 to 1959, he was First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

, a position that had been held by his father, Prince Louis of Battenberg

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Alexander Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven, (24 May 185411 September 1921), formerly Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg, was a British naval officer and German prince related by marriage to the British ...

, some forty years earlier. Thereafter he served as chief of the Defence Staff until 1965, making him the longest-serving professional head of the British Armed Forces to date. During this period Mountbatten also served as chairman of the NATO Military Committee

The Chair of the NATO Military Committee (CMC) is the head of the NATO Military Committee, which advises the North Atlantic Council (NAC) on military policy and strategy. The CMC is the senior military spokesperson of the 30-nation alliance and p ...

for a year.

In August 1979, Mountbatten was assassinated by a bomb planted aboard his fishing boat in Mullaghmore, County Sligo

Mullaghmore () is a village on the Mullaghmore Peninsula in County Sligo, Ireland. It is a holiday destination with a skyline dominated by Benbulben mountain. It is in the barony of Carbury and parish of Ahamlish.

History

From the 17th to ...

, Ireland, by members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reu ...

. He received a ceremonial funeral at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

and was buried in Romsey Abbey

Romsey Abbey is the name currently given to a parish church of the Church of England in Romsey, a market town in Hampshire, England. Until the Dissolution of the Monasteries it was the church of a Benedictine nunnery. The surviving Norman-era c ...

in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

.

Early life

Mountbatten, then named Prince Louis of Battenberg, was born on 25 June 1900 atFrogmore House

Frogmore House is a 17th-century English country house owned by the Crown Estate. It is a historic Grade I listed building. The house is located on the Frogmore estate, which is situated within the grounds of the Home Park in Windsor, Berkshi ...

in the Home Park

Home Park is a football stadium in Plymouth, England. The ground has been the home of Football League One club Plymouth Argyle since 1901.Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

, Berkshire. He was the youngest child and the second son of Prince Louis of Battenberg

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Alexander Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven, (24 May 185411 September 1921), formerly Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg, was a British naval officer and German prince related by marriage to the British ...

and his wife Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine

Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine (Victoria Alberta Elizabeth Mathilde Marie; 5 April 1863 – 24 September 1950), later Victoria Mountbatten, Marchioness of Milford Haven, was the eldest daughter of Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rh ...

. Mountbatten's maternal grandparents were Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse

English: Frederick William Louis Charles

, house = Hesse-Darmstadt

, father = Prince Charles of Hesse and by Rhine

, mother = Princess Elisabeth of Prussia

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Prinz-Carl-Palais, Darmstadt, Gra ...

, and Princess Alice of the United Kingdom

Princess Alice (Alice Maud Mary; 25 April 1843 – 14 December 1878) was Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine from 13 June 1877 until her death in 1878 as the wife of Grand Duke Louis IV. She was the third child and second daughter of Queen ...

, who was a daughter of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel; 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the consort of Queen Victoria from their marriage on 10 February 1840 until his death in 1861.

Albert was born in the Saxon duch ...

. His paternal grandparents were Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine

Prince Alexander Ludwig Georg Friedrich Emil of Hesse and by Rhine, (15 July 1823 – 15 December 1888), was the third son and fourth child of Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse, and Wilhelmine of Baden. He was a brother of Tsarina Maria Alexandr ...

and Julia, Princess of Battenberg

Julia, Princess of Battenberg (previously Countess Julia Therese Salomea von Hauke; – 19 September 1895) was the wife of Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine, the third son of Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse. The daughter of a Polish general o ...

. Mountbatten's paternal grandparents' marriage was morganatic

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spous ...

because his grandmother was not of royal lineage; as a result, he and his father were styled "Serene Highness" rather than "Grand Ducal Highness", were not eligible to be titled Princes of Hesse, and were given the less exalted Battenberg title. Mountbatten's elder siblings were Princess Alice of Battenberg

Princess Alice of Battenberg (Victoria Alice Elizabeth Julia Marie; 25 February 1885 – 5 December 1969) was the mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, mother-in-law of Queen Elizabeth II, and the paternal grandmother of King Charles III ...

(later Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from E ...

), Princess Louise of Battenberg (later Queen Louise of Sweden), and Prince George of Battenberg (later George Mountbatten, 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven

Captain George Louis Victor Henry Serge Mountbatten, 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven, (6 November 1892Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: ''901''; Laufende Nummer: ''150'' – 8 April 1938), born Prince George of Batten ...

).

Mountbatten was baptised in the large drawing room of Frogmore House on 17 July 1900 by the Dean of Windsor

The Dean of Windsor is the spiritual head of the canons of St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, England. The dean chairs meetings of the Chapter of Canons as ''primus inter pares''. The post of Dean of Wolverhampton was assimilated to the dea ...

, Philip Eliot. His godparents were Queen Victoria, Nicholas II of Russia (represented by the child's father) and Prince Francis Joseph of Battenberg (represented by Lord Edward Clinton

Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Edward William Pelham-Clinton (11 August 1836 – 9 July 1907), known as Lord Edward Clinton, was a British Liberal Party politician.

Life

Clinton was the second son of Henry Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle an ...

). He wore the original 1841 royal christening gown

A royal christening gown is an item of baptismal clothing used by a royal family at family christenings. Among those presently using such a gown are the royal families of the United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Sweden. ...

at the ceremony.

Mountbatten's nickname among family and friends was "Dickie"; however "Richard" was not among his given names. This was because his great-grandmother, Queen Victoria, had suggested the nickname of "Nicky", but to avoid confusion with the many Nickys of the Russian Imperial Family ("Nicky" was particularly used to refer to Nicholas II, the last Tsar), "Nicky" was changed to "Dickie".

Mountbatten was educated at home for the first 10 years of his life; he was then sent to Lockers Park School

Lockers Park School is a day and boarding preparatory and pre-preparatory school for boys, situated in 23 acres of countryside in Boxmoor, Hertfordshire. Its headmaster is Gavin Taylor.

History

Lockers Park was founded in 1874 by Henry Montagu ...

in Hertfordshire. and on to the Royal Naval College, Osborne

The Royal Naval College, Osborne, was a training college for Royal Navy officer cadets on the Osborne House estate, Isle of Wight, established in 1903 and closed in 1921.

Boys were admitted at about the age of thirteen to follow a course lasting ...

, in May 1913..

Mountbatten's mother's younger sister was Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. In childhood he visited the Imperial Court of Russia at St Petersburg and became intimate with the Russian Imperial Family

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to t ...

, harbouring romantic feelings towards his maternal first cousin Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna of Russia (Maria Nikolaevna Romanova; Russian: Великая Княжна Мария Николаевна, 17 July 1918) was the third daughter of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna. He ...

, whose photograph he kept at his bedside for the rest of his life..

From 1914 to 1918, Britain and its allies were at war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, led by the German Empire. To appease British nationalist sentiment, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

issued a royal proclamation changing the name of the British royal house from the German House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

The House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (; german: Haus Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha) is a European royal house. It takes its name from its oldest domain, the Ernestine duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, its members later sat on the thrones of Belgium, Bu ...

to the House of Windsor

The House of Windsor is the reigning royal house of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms. In 1901, a line of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (itself a cadet branch of the House of Wettin) succeeded the House of Hanover to th ...

. The king's British relatives followed suit with Mountbatten's father dropping his German titles and name and adopting the surname Mountbatten, an anglicization of Battenberg. His father was subsequently created Marquess of Milford Haven

Marquess of Milford Haven is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The marquessate of Milford Haven was created in 1917 for Prince Louis of Battenberg, the former First Sea Lord, and a relation by marriage to the British Royal ...

.

Career

Early career

Mountbatten was posted as midshipman to the battlecruiser in July 1916 and, after seeing action in August 1916, transferred to the battleship during the closing phases of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. In June 1917, when the royal family stopped using their German names and titles and adopted the more British-sounding "Windsor", Mountbatten acquired the courtesy title appropriate to a younger son of a marquess, becoming known as ''Lord Louis Mountbatten'' (''Lord Louis'' for short) until he was created a peer in his own right in 1946.. He paid a visit of ten days to the Western Front, in July 1918.

While still an acting- sub-lieutenant, Mountbatten was appointed

While still an acting- sub-lieutenant, Mountbatten was appointed first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

(second-in-command) of the P-class sloop

The P class, nominally described as "patrol boats", was in effect a class of British coastal sloops. Twenty-four ships to this design were ordered in May 1915 (numbered ''P.11'' to ''P.34'') and another thirty between February and June 1916 (num ...

HMS ''P. 31'' on 13 October 1918 and was confirmed as a substantive sub-lieutenant on 15 January 1919. HMS ''P. 31'' took part in the Peace River Pageant on 4 April 1919. Mountbatten attended Christ's College, Cambridge, for two terms, starting in October 1919, where he studied English literature (including John Milton and Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

) in a programme designed to augment the education of junior officers which had been curtailed by the war. He was elected for a term to the Standing Committee of the Cambridge Union Society

The Cambridge Union Society, also known as the Cambridge Union, is a debating and free speech society in Cambridge, England, and the largest society in the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1815, it is the oldest continuously running debati ...

and was suspected of sympathy for the Labour Party, then emerging as a potential party of government for the first time.

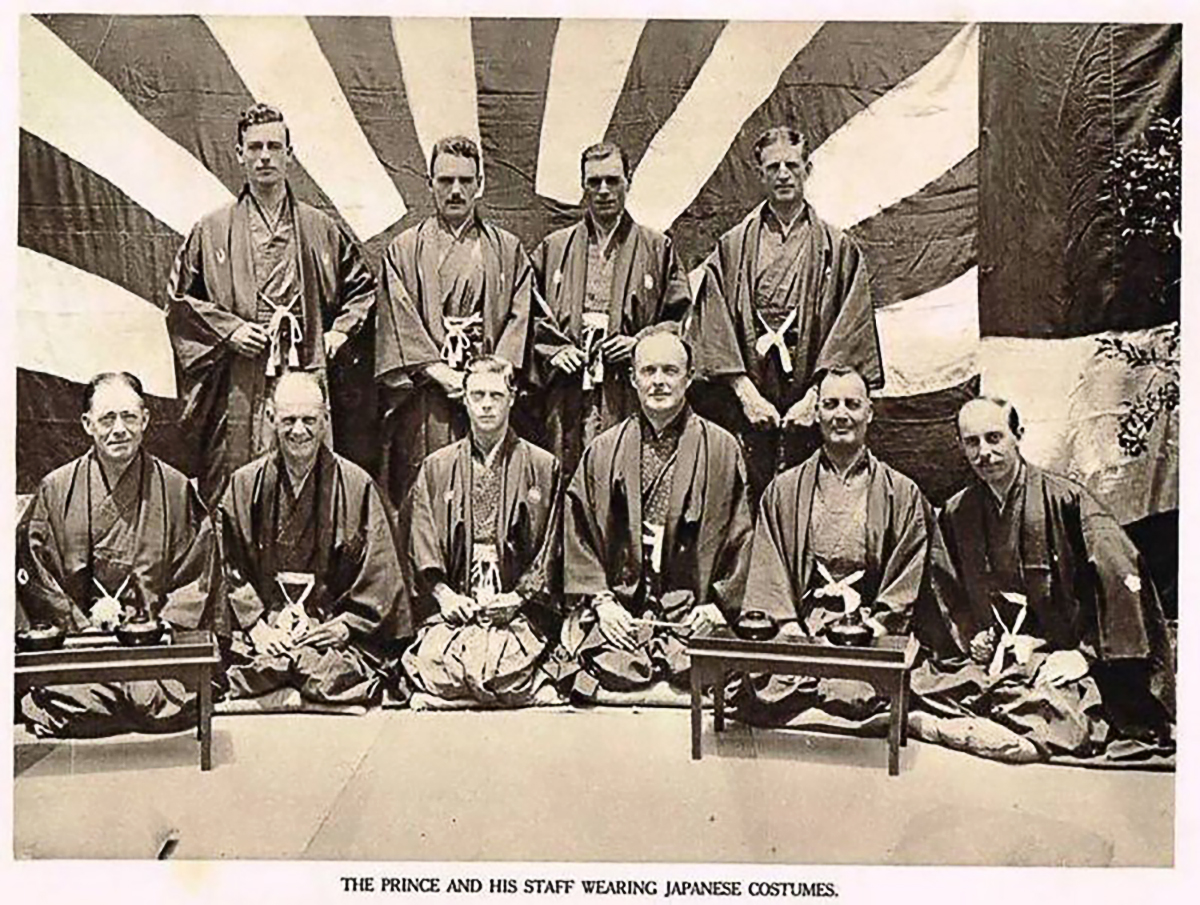

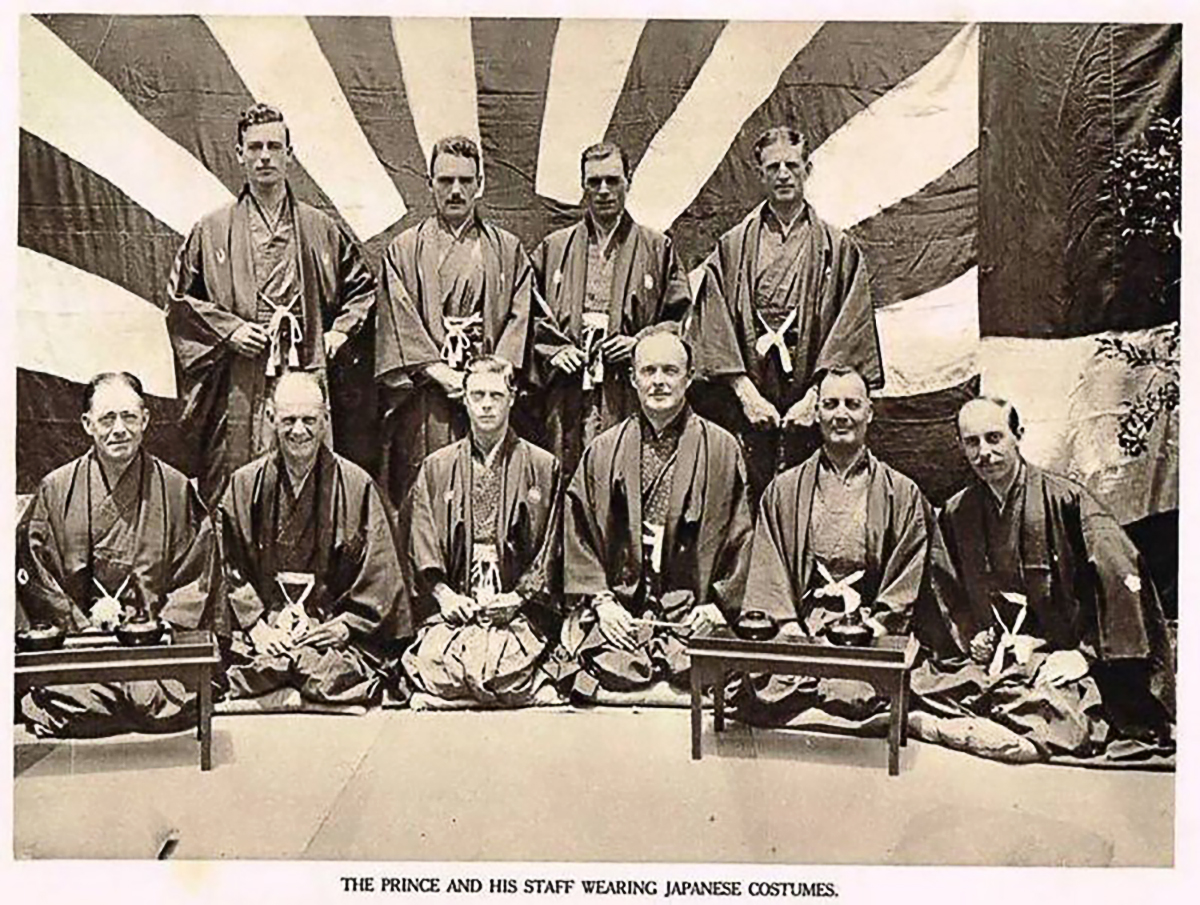

Mountbatten was posted to the battlecruiser in March 1920 and accompanied Edward, Prince of Wales, on a royal tour of Australia in her. He was promoted

Mountbatten was posted to the battlecruiser in March 1920 and accompanied Edward, Prince of Wales, on a royal tour of Australia in her. He was promoted lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

on 15 April 1920. HMS ''Renown'' returned to Portsmouth on 11 October 1920. Early in 1921 Royal Navy personnel were used for civil defence duties as serious industrial unrest seemed imminent. Mountbatten had to command a platoon of stokers, many of whom had never handled a rifle before, in northern England. He transferred to the battlecruiser in March 1921 and accompanied the Prince of Wales on a Royal tour of India and Japan. Edward and Mountbatten formed a close friendship during the trip. Mountbatten survived the deep defence cuts known as the Geddes Axe

The Geddes Axe was the drive for public economy and retrenchment in UK government expenditure recommended in the 1920s by a Committee on National Expenditure chaired by Sir Eric Geddes and with Lord Inchcape, Lord Faringdon, Sir Joseph Maclay an ...

. Fifty-two percent of the officers of his year had had to leave the Royal Navy by the end of 1923; although he was highly regarded by his superiors, it was rumoured that wealthy and well-connected officers were more likely to be retained. Mountbatten was posted to the battleship in the Mediterranean Fleet in January 1923.

Pursuing his interests in technological development and gadgetry, Mountbatten joined the Portsmouth Signals School in August 1924 and then went on briefly to study electronics at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich

The Royal Naval College, Greenwich, was a Royal Navy training establishment between 1873 and 1998, providing courses for naval officers. It was the home of the Royal Navy's staff college, which provided advanced training for officers. The equi ...

. Mountbatten became a Member of the Institution of Electrical Engineers ( IEE), now the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET __NOTOC__

IET can refer to:

Organizations

* Institute of Educational Technology, part of the Open University

* Institution of Engineering and Technology, a UK-based professional engineering institution

** Institute of Engineers and Technicians, wh ...

). He was posted to the battleship in the Reserve Fleet in 1926 and became Assistant Fleet Wireless and Signals Officer of the Mediterranean Fleet under the command of Admiral Sir Roger Keyes in January 1927. Promoted lieutenant-commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

on 15 April 1928, Mountbatten returned to the Signals School in July 1929 as Senior Wireless Instructor. He was appointed Fleet Wireless Officer to the Mediterranean Fleet in August 1931 and, having been promoted commander on 31 December 1932, was posted to the battleship .

In 1934, Mountbatten was appointed to his first command – the destroyer . His ship was a new destroyer, which he was to sail to Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

and exchange for an older ship, . He successfully brought ''Wishart'' back to port in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and then attended the funeral of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

in January 1936. Mountbatten was appointed a personal naval aide-de-camp to King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

on 23 June 1936 and, having joined the Naval Air Division of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

in July 1936, he attended the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in May 1937. Mountbatten was promoted captain on 30 June 1937 and was then given command of the destroyer in June 1939..

Within the Admiralty, Mountbatten was called "The Master of Disaster" for his penchant of getting into messes.

Second World War

When war broke out in September 1939, Mountbatten became Captain (D) (commander) of the

When war broke out in September 1939, Mountbatten became Captain (D) (commander) of the 5th Destroyer Flotilla

The British 5th Destroyer Flotilla, or Fifth Destroyer Flotilla, was a naval formation of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the ...

aboard HMS ''Kelly'', which became famous for its exploits. In late 1939 he brought the Duke of Windsor

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 1 ...

back from exile in France and in early May 1940 Mountbatten led a British convoy in through the fog to evacuate the Allied forces participating in the Namsos Campaign during the Norwegian Campaign.

On the night of 9–10 May 1940, ''Kelly'' was torpedoed amidships by a German E-boat

E-boat was the Western Allies' designation for the fast attack craft (German: ''Schnellboot'', or ''S-Boot'', meaning "fast boat") of the Kriegsmarine during World War II; ''E-boat'' could refer to a patrol craft from an armed motorboat to a lar ...

''S 31'' off the Dutch coast, and Mountbatten thereafter commanded the 5th Destroyer Flotilla from the destroyer . On 29 November 1940 the 5th Flotilla engaged three German destroyers off Lizard Point, Cornwall

Lizard Point () in Cornwall is at the southern tip of the Lizard Peninsula. It is situated half-a-mile (800 m) south of Lizard village in the civil parish of Landewednack and about 11 miles (18 km) southeast of Helston.

Lizard Poi ...

. Mountbatten turned to port to match a German course change. This was "a rather disastrous move as the directors

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

swung off and lost target" and it resulted in ''Javelin'' being struck by two torpedoes. He rejoined ''Kelly'' in December 1940, by which time the torpedo damage had been repaired.

''Kelly'' was sunk by German dive bombers on 23 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major Axis airborne and amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island ...

; the incident serving as the basis for Noël Coward's film '' In Which We Serve''. Coward was a personal friend of Mountbatten and copied some of his speeches into the film. Mountbatten was mentioned in despatches on 9 August 1940 and 21 March 1941 and awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, ty ...

in January 1941.

In August 1941, Mountbatten was appointed captain of the aircraft carrier which lay in Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs following action at Malta in January. During this period of relative inactivity, he paid a flying visit to

In August 1941, Mountbatten was appointed captain of the aircraft carrier which lay in Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs following action at Malta in January. During this period of relative inactivity, he paid a flying visit to Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

, three months before the Japanese attack on it. Mountbatten, appalled at the US naval base's lack of preparedness, drawing on Japan's history of launching wars with surprise attacks as well as the successful British surprise attack at the Battle of Taranto

The Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during the Second World War between British naval forces, under Admiral Andrew Cunningham, and Italian naval forces, under Admiral Inigo Campioni. The Royal Navy launched ...

which had effectively knocked Italy's fleet out of the war, and the sheer effectiveness of aircraft against warships, accurately predicted that the US would enter the war after a Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Mountbatten was a favourite of

Mountbatten was a favourite of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

. On 27 October 1941, Mountbatten replaced Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes as Chief of Combined Operations Headquarters

Combined Operations Headquarters was a department of the British War Office set up during Second World War to harass the Germans on the European continent by means of raids carried out by use of combined naval and army forces.

History

The comm ...

and was promoted to commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

.

His duties in this role included inventing new technical aids to assist with opposed landings. Noteworthy technical achievements of Mountbatten and his staff include the construction of "PLUTO", an underwater oil pipeline to Normandy, an artificial Mulberry harbour constructed of concrete caissons and sunken ships, and the development of tank-landing ships. Another project Mountbatten proposed to Churchill was Project Habakkuk

Project Habakkuk or Habbakuk (spelling varies) was a plan by the British during the Second World War to construct an aircraft carrier out of pykrete (a mixture of wood pulp and ice) for use against German U-boats in the mid-Atlantic, which wer ...

. It was to be an unsinkable 600-metre aircraft carrier made from reinforced ice ("Pykrete

Pykrete is a frozen ice composite, originally made of approximately 14% sawdust or some other form of wood pulp (such as paper) and 86% ice by weight (6 to 1 by weight). During World War II, Geoffrey Pyke proposed it as a candidate material fo ...

"): Habakkuk was never carried out due to its enormous cost.

As commander of Combined Operations, Mountbatten and his staff planned the highly successful

As commander of Combined Operations, Mountbatten and his staff planned the highly successful Bruneval raid

Operation Biting, also known as the Bruneval Raid, was a British Combined Operations raid on a German coastal radar installation at Bruneval in northern France, during the Second World War, on the night .

Several of these installations were id ...

, which gained important information and captured part of a German Würzburg radar

The low-UHF band Würzburg radar was the primary ground-based tracking radar for the Wehrmacht's Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine (German Navy) during World War II. Initial development took place before the war and the apparatus entered service in 1940 ...

installation and one of the machine's technicians on 27 February 1942. It was Mountbatten who recognised that surprise and speed were essential to capture the radar, and saw that an airborne assault was the only viable method.

On 18 March 1942, he was promoted to the acting rank

An acting rank is a designation that allows a soldier to assume a military rank—usually higher and usually temporary. They may assume that rank either with or without the pay and allowances appropriate to that grade, depending on the nature of t ...

of vice admiral and given the honorary rank

Military ranks are a system of hierarchical relationships, within armed forces, police, intelligence agencies or other institutions organized along military lines. The military rank system defines dominance, authority, and responsibility in a m ...

s of lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

and air marshal to have the authority to carry out his duties in Combined Operations; and, despite the misgivings of General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

, Mountbatten was placed in the Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the C ...

. He was in large part responsible for the planning and organisation of the St Nazaire Raid on 28 March, which put out of action one of the most heavily defended docks in Nazi-occupied France until well after the war's end, the ramifications of which contributed to allied supremacy in the Battle of the Atlantic. After these two successes came the Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942. He was central in the planning and promotion of the raid on the port of Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to N ...

. The raid was a marked failure, with casualties of almost 60%, the great majority of them Canadians. Following the Dieppe Raid, Mountbatten became a controversial figure in Canada, with the Royal Canadian Legion distancing itself from him during his visits there during his later career.. His relations with Canadian veterans, who blamed him for the losses, "remained frosty" after the war.

Mountbatten claimed that the lessons learned from the Dieppe Raid were necessary for planning the Normandy invasion on D-Day nearly two years later. However, military historians such as

Mountbatten claimed that the lessons learned from the Dieppe Raid were necessary for planning the Normandy invasion on D-Day nearly two years later. However, military historians such as Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Julian Thompson, a former member of the Royal Marines, have written that these lessons should not have needed a debacle such as Dieppe to be recognised.. Nevertheless, as a direct result of the failings of the Dieppe Raid, the British made several innovations, most notably Hobart's Funnies

Hobart's Funnies is the nickname given to a number of specialist armoured fighting vehicles derived from tanks operated during the Second World War by units of the 79th Armoured Division of the British Army or by specialists from the Royal En ...

– specialised armoured vehicles which, in the course of the Normandy Landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

, undoubtedly saved many lives on those three beachheads upon which Commonwealth soldiers were landing ( Gold Beach, Juno Beach and Sword Beach

Sword, commonly known as Sword Beach, was the code name given to one of the five main landing areas along the Normandy coast during the initial assault phase, Operation Neptune, of Operation Overlord. The Allied invasion of German-occupied Fr ...

).

In August 1943, Churchill appointed Mountbatten the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir A ...

(SEAC) with promotion to acting full admiral. His less practical ideas were sidelined by an experienced planning staff led by Lieutenant-Colonel James Allason, though some, such as a proposal to launch an amphibious assault near Rangoon, got as far as Churchill before being quashed.

British interpreter Hugh Lunghi recounted an embarrassing episode during the

British interpreter Hugh Lunghi recounted an embarrassing episode during the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

when Mountbatten, desiring to receive an invitation to visit the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, repeatedly attempted to impress Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

with his former connections to the Russian imperial family

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to t ...

. The attempt fell predictably flat, with Stalin dryly inquiring whether "it was some time ago that he had been there". Says Lunghi, "The meeting was embarrassing because Stalin was so unimpressed. He offered no invitation. Mountbatten left with his tail between his legs."

During his time as Supreme Allied Commander of the Southeast Asia Theatre, his command oversaw the recapture of Burma from the Japanese by General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir William Slim. A personal high point was the receipt of the Japanese surrender in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

when British troops returned to the island to receive the formal surrender of Japanese forces in the region led by General Itagaki Seishiro is a Japanese surname.

People with the name

*, Japanese ski jumper

*, Japanese manga artist

*, one of the Twenty-four Generals of Takeda Shingen during the Sengoku period

*, Japanese manga artist

*, World War II Imperial Japanese army general

*, ...

on 12 September 1945, codenamed Operation Tiderace. South East Asia Command was disbanded in May 1946 and Mountbatten returned home with the substantive rank of rear-admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

.. That year, he was made a Knight of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George ...

and created Viscount Mountbatten of Burma, of Romsey in the County of Southampton

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire is ...

, as a victory title

A victory title is an honorific title adopted by a successful military commander to commemorate his defeat of an enemy nation. The practice is first known in Ancient Rome and is still most commonly associated with the Romans, but it was also adop ...

for war service. He was then in 1947 further created Earl Mountbatten of Burma and Baron Romsey, of Romsey in the County of Southampton.

Following the war, Mountbatten was known to have largely shunned the Japanese for the rest of his life out of respect for his men killed during the war and, as per his will, Japan was not invited to send diplomatic representatives to his funeral in 1979, though he did meet Emperor Hirohito during his state visit to Britain in 1971, reportedly at the urging of the Queen.

Last Viceroy of India

Mountbatten's experience in the region and in particular his perceived Labour sympathies at that time led to Clement Attlee advising King George VI to appoint himViceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

on 20 February 1947 charged with overseeing the transition of British India to independence no later than 30 June 1948. Mountbatten's instructions were to avoid partition and preserve a united India as a result of the transfer of power but authorised him to adapt to a changing situation in order to get Britain out promptly with minimal reputational damage.. Mountbatten arrived in India on 22 March 1947 by air, from London. In the evening, he was taken to his residence and, two days later, he took the Viceregal Oath. His arrival saw large-scale communal riots in Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders ...

, Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

and Rawalpindi. Mountbatten concluded that the situation was too volatile to wait even a year before granting independence to India. Although his advisers favoured a gradual transfer of independence, Mountbatten decided the only way forward was a quick and orderly transfer of power before 1947 was out. In his view, any longer would mean civil war.. Mountbatten also hurried so he could return to his senior technical Navy courses..

Mountbatten was fond of

Mountbatten was fond of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

leader Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and his liberal outlook for the country. He felt differently about the Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah, but was aware of his power, stating "If it could be said that any single man held the future of India in the palm of his hand in 1947, that man was Mohammad Ali Jinnah." During his meeting with Jinnah on 5 April 1947, Mountbatten tried to persuade him of a united India, citing the difficult task of dividing the mixed states of Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

and Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, but the Muslim leader was unyielding in his goal of establishing a separate Muslim state called Pakistan.

Given the British government's recommendations to grant independence quickly, Mountbatten concluded that a united India was an unachievable goal and resigned himself to a plan for partition, creating the independent nations of India and Pakistan. Mountbatten set a date for the transfer of power from the British to the Indians, arguing that a fixed timeline would convince Indians of his and the British government's sincerity in working towards a swift and efficient independence, excluding all possibilities of stalling the process..

Among the Indian leaders,

Given the British government's recommendations to grant independence quickly, Mountbatten concluded that a united India was an unachievable goal and resigned himself to a plan for partition, creating the independent nations of India and Pakistan. Mountbatten set a date for the transfer of power from the British to the Indians, arguing that a fixed timeline would convince Indians of his and the British government's sincerity in working towards a swift and efficient independence, excluding all possibilities of stalling the process..

Among the Indian leaders, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

emphatically insisted on maintaining a united India and for a while successfully rallied people to this goal. During his meeting with Mountbatten, Gandhi asked Mountbatten to invite Jinnah to form a new central government, but Mountbatten never uttered a word of Gandhi's ideas to Jinnah. When Mountbatten's timeline offered the prospect of attaining independence soon, sentiments took a different turn. Given Mountbatten's determination, Nehru and Patel's inability to deal with the Muslim League and, lastly, Jinnah's obstinacy, all Indian party leaders (except Gandhi) acquiesced to Jinnah's plan to divide India,. which in turn eased Mountbatten's task. Mountbatten also developed a strong relationship with the Indian princes, who ruled those portions of India not directly under British rule. His intervention was decisive in persuading the vast majority of them to see advantages in opting to join the Indian Union. On one hand, the integration of the princely states can be viewed as one of the positive aspects of his legacy. But on the other, the refusal of Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India ...

, Jammu and Kashmir, and Junagadh

Junagadh () is the headquarters of Junagadh district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Located at the foot of the Girnar hills, southwest of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar (the state capital), it is the seventh largest city in the state.

Literally ...

to join one of the dominions led to future wars

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

between Pakistan and India.

Mountbatten brought forward the date of the partition from June 1948 to 15 August 1947. The uncertainty of the borders caused Muslims and Hindus to move into the direction where they felt they would get the majority. Hindus and Muslims were thoroughly terrified, and the Muslim movement from the East was balanced by the similar movement of Hindus from the West. A boundary committee chaired by Sir Cyril Radcliffe was charged with drawing boundaries for the new nations. With a mandate to leave as many Hindus and Sikhs in India and as many Muslims in Pakistan as possible, Radcliffe came up with a map that split the two countries along the Punjab and Bengal borders. This left 14 million people on the "wrong" side of the border, and very many of them fled to "safety" on the other side when the new lines were announced.

When India and Pakistan attained independence at midnight of 14–15 August 1947, Mountbatten was alone in his study at the Viceroy's house saying to himself just before the clock struck midnight that for still a few minutes, he was the most powerful man on Earth. At 11:58 PM, as a last act of showmanship, he created Joan Falkiner, the Australian wife of the Nawab of

When India and Pakistan attained independence at midnight of 14–15 August 1947, Mountbatten was alone in his study at the Viceroy's house saying to himself just before the clock struck midnight that for still a few minutes, he was the most powerful man on Earth. At 11:58 PM, as a last act of showmanship, he created Joan Falkiner, the Australian wife of the Nawab of Palanpur

Palanpur is a city and a municipality of Banaskantha district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Palanpur is the administrative headquarters of Banaskantha district. Palanpur is the ancestral home to an industry of Indian diamond merchants.

Ety ...

, a highness, an act that was apparently one of his favourite duties that was annulled at the stroke of midnight.

Mountbatten remained in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament Ho ...

for 10 months, serving as the first governor-general of an independent India until June 1948.. On Mountbatten's advice, India took the issue of Kashmir to the newly formed United Nations in January 1948. This issue would become a lasting thorn in his legacy and one that is not resolved to this day. Accounts differ on the future which Mountbatten desired for Kashmir. Pakistani accounts suggest that Mountbatten favoured the accession of Kashmir to India, citing his close relationship to Nehru. Mountbatten's own account says that he simply wanted the maharaja, Hari Singh

Maharaja Sir Hari Singh (September 1895 – 26 April 1961) was the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Hari Singh was the son of Amar Singh and Bhotiali Chib. In 1923, following his uncle's death, Singh became ...

, to make up his mind. The viceroy made several attempts to mediate between the Congress leaders, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Hari Singh on issues relating to the accession of Kashmir, though he was largely unsuccessful in resolving the conflict. After the tribal invasion of Kashmir, it was on his suggestion that India moved to secure the accession of Kashmir from Hari Singh before sending in military forces for his defence.

Notwithstanding the self-promotion of his own part in Indian independence – notably in the television series ''The Life and Times of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma'', produced by his son-in-law

Notwithstanding the self-promotion of his own part in Indian independence – notably in the television series ''The Life and Times of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma'', produced by his son-in-law Lord Brabourne

Baron Brabourne, of Brabourne in the County of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1880 for the Liberal politician Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen, the second son of Sir Edward Knatchbull, 9th Baronet, of Mers ...

, and '' Freedom at Midnight'' by Dominique Lapierre

Dominique Lapierre (30 July 1931 – 2 December 2022) was a French author.

Life

Dominique Lapierre was born in Châtelaillon-Plage, Charente-Maritime, France. At the age of thirteen, he travelled to the U.S. with his father who was a diploma ...

and Larry Collins (of which he was the main quoted source) – his record is seen as very mixed. One common view is that he hastened the process of independence unduly and recklessly, foreseeing vast disruption and loss of life and not wanting this to occur on his watch, but thereby actually helping it to occur (albeit in an indirect manner), especially in Punjab and Bengal. John Kenneth Galbraith

John Kenneth Galbraith (October 15, 1908 – April 29, 2006), also known as Ken Galbraith, was a Canadian-American economist, diplomat, public official, and intellectual. His books on economic topics were bestsellers from the 1950s through t ...

, the Canadian-American Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

economist, who advised governments of India during the 1950s and was an intimate of Nehru who served as the American ambassador from 1961 to 1963, was a particularly harsh critic of Mountbatten in this regard. However, another view is that the British were forced to expedite the partition process to avoid involvement in a potential civil war with law and order having already broken down and Britain with limited resources after the Second World War.Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, ''Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World'', p. 72 According to historian Lawrence James, Mountbatten was left with no other option but to cut and run, with the alternative being involvement in a potential civil war that would be difficult to get out of.

The creation of Pakistan was never emotionally accepted by many British leaders, among them Mountbatten. Mountbatten clearly expressed his lack of support and faith in the Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

's idea of Pakistan. Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

refused Mountbatten's offer to serve as Governor-General of Pakistan. When Mountbatten was asked by Collins and Lapierre if he would have sabotaged the creation of Pakistan had he known that Jinnah was dying of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

, he replied, "Most probably". After his tenure as Governor-General concluded, Mountbatten continued to enjoy close relations with Nehru and the post-Independence Indian leadership, and was welcomed as a former governor-general of India on subsequent visits to the country, including during an official trip in March 1956. The Pakistani government, by contrast, never forgave Mountbatten for his perceived hostile attitude towards Pakistan and deemed him ''persona non grata'', barring him from transiting their airspace during the same visit.

Career after India

After India, Mountbatten served as commander of the

After India, Mountbatten served as commander of the 1st Cruiser Squadron

The First Cruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of cruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the World War I then later as part of the Mediterranean during the Interwar period and World War II it first established in 190 ...

in the Mediterranean Fleet and, having been granted the substantive rank of vice-admiral on 22 June 1949, he became Second-in-Command of the Mediterranean Fleet in April 1950. He became Fourth Sea Lord

The Fourth Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Supplies originally known as the Fourth Naval Lord was formerly one of the Naval Lords and members of the Board of Admiralty which controlled the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom the post is currently known ...

at the Admiralty in June 1950. He then returned to the Mediterranean to serve as Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet and NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

Commander Allied Forces Mediterranean

Allied Forces Mediterranean was a NATO command covering all military operations in the Mediterranean Sea from 1952 to 1967. The command was based at Malta.

History

The British post of Commander in Chief Mediterranean Fleet was given a dual-hatte ...

from June 1952. He was promoted to the substantive rank of full admiral on 27 February 1953. In March 1953, he was appointed Personal Aide-de-Camp to the Queen.

Mountbatten served his final posting at the Admiralty as

Mountbatten served his final posting at the Admiralty as First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

and Chief of the Naval Staff from April 1955 to July 1959, the position which his father had held some forty years before. This was the first time in Royal Naval history that a father and son had both attained such high office. He was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 22 October 1956.

In the Suez Crisis of 1956, Mountbatten strongly advised his old friend Prime Minister Anthony Eden against the Conservative government's plans to seize the Suez canal in conjunction with France and Israel. He argued that such a move would destabilize the Middle East, undermine the authority of the United Nations, divide the Commonwealth and diminish Britain's global standing. His advice was not taken. Eden insisted that Mountbatten not resign. Instead, he worked hard to prepare the Royal Navy for war with characteristic professionalism and thoroughness.

Despite his military rank, Mountbatten was ignorant as to the physics involved in a nuclear explosion and had to be reassured that the fission reactions from the Bikini Atoll tests

Nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll consisted of the detonation of 23 nuclear weapons by the United States between 1946 and 1958 on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tests occurred at 7 test sites on the reef itself, on the sea, in the air ...

would not spread through the oceans and blow up the planet. As Mountbatten became more familiar with this new form of weaponry, he increasingly grew opposed to its use in combat yet at the same time he realised the potential for nuclear energy, especially with regard to submarines. Mountbatten expressed his feelings towards the use of nuclear weapons in combat in his article "A Military Commander Surveys The Nuclear Arms Race", which was published shortly after his death in ''International Security'' in the Winter of 1979–1980.

After leaving the Admiralty, Mountbatten took the position of Chief of the Defence Staff. He served in this post for six years during which he was able to consolidate the three service departments of the military branch into a single Ministry of Defence.. Ian Jacob

Lieutenant General Sir Edward Ian Claud Jacob (27 September 1899 – 24 April 1993), known as Ian Jacob, was a British Army officer, who served as the Military Assistant Secretary to Winston Churchill's war cabinet and was later a distinguished ...

, co-author of the 1963 ''Report on the Central Organisation of Defence'' that served as the basis of these reforms, described Mountbatten as "universally mistrusted in spite of his great qualities".. On their election in October 1964, the Wilson ministry had to decide whether to renew his appointment the following July. The Defence Secretary

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

, Denis Healey, interviewed the forty most senior officials in the Ministry of Defence; only one, Sir Kenneth Strong, a personal friend of Mountbatten, recommended his reappointment. "When I told Dickie of my decision not to reappoint him," recalls Healey, "he slapped his thigh and roared with delight; but his eyes told a different story."

Mountbatten was appointed colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

of the Life Guards and Gold Stick in Waiting on 29 January 1965 and Life Colonel Commandant of the Royal Marines the same year. He was Governor of the Isle of Wight

Below is a list of those who have held the office of Governor of the Isle of Wight in England. Lord Mottistone was the last lord lieutenant to hold the title governor, from 1992 to 1995; since then there has been no governor appointed.

Governor ...

from 20 July 1965 and then the first Lord Lieutenant of the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

from 1 April 1974.

Mountbatten was elected a

Mountbatten was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

and had received an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

from Heriot-Watt University in 1968.

In 1969, Mountbatten tried unsuccessfully to persuade his cousin, the Spanish pretender Infante Juan, Count of Barcelona

Infante Juan, Count of Barcelona (Juan Carlos Teresa Silverio Alfonso de Borbón y Battenberg; 20 June 1913 – 1 April 1993), also known as Don Juan, was a claimant to the Spanish throne as Juan III. He was the third son and designated heir o ...

, to ease the eventual accession of his son, Juan Carlos

Juan Carlos I (;,

* ca, Joan Carles I,

* gl, Xoán Carlos I, Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 Novem ...

, to the Spanish throne by signing a declaration of abdication while in exile.. The next year Mountbatten attended an official White House dinner during which he took the opportunity to have a 20-minute conversation with Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

and Secretary of State William P. Rogers, about which he later wrote, "I was able to talk to the President a bit about both Tino onstantine II of Greeceand Juanito uan Carlos of Spain

UAN is a solution of urea and ammonium nitrate in water used as a fertilizer.

Uan or UAN may also refer to:

* Adapa, an alternate name for the first of the Mesopotamian seven sages

* Autonomous University of Nayarit ((in Spanish: ), a Mexican publ ...

to try and put over their respective points of view about Greece and Spain, and how I felt the US could help them." In January 1971, Nixon hosted Juan Carlos and his wife Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

(sister of the exiled King Constantine) during a visit to Washington and later that year ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' published an article alleging that Nixon's administration was seeking to persuade Franco to retire in favour of the young Bourbon prince.