Lou Harrison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lou Silver Harrison (May 14, 1917 – February 2, 2003) was an American

Harrison was born on May 14, 1917, in

Harrison was born on May 14, 1917, in

"Lou Harrison, The 'Maverick' Composer With Asia In His Ears"

''

"New York Celebrates a Composer Who Left Town"

''

After graduating high school in 1934, Harrison enrolled in San Francisco State College (now

After graduating high school in 1934, Harrison enrolled in San Francisco State College (now

"Lou Harrison's generosity endures when we most need it"

''

"Lou Harrison – In Retrospect"

''New World Records''. Retrieved June 25, 2022. He would later say, "... it was no jump at all to learn to write twelve-tone music; Henry's the one who taught me." The pieces he was writing at this time, however, were largely percussive works using unconventional materials, such as discarded car brake drums and

Although much influenced by Asian music, Harrison did not visit the continent until a 1961 trip to Japan and Korea, and a 1962 trip to Taiwan (where he studied with the zheng master

Although much influenced by Asian music, Harrison did not visit the continent until a 1961 trip to Japan and Korea, and a 1962 trip to Taiwan (where he studied with the zheng master

1917–2017, part 2 of 5. for these instruments and chorus, as well as Suite for Violin and American Gamelan. In addition, Harrison played and composed for the Chinese

An often used technique is "interval control", in which only small number of melodic intervals, either ascending or descending, are used, without inversion.Leta E. Miller and Fredric Lieberman (Summer 1999). "Lou Harrison and the American Gamelan", '' American Music'', vol. 17, no. 2, p. 168. For example, for the opening of the Fourth Symphony, the permitted intervals are minor third, minor sixth, and major second.

Another component of Harrison's aesthetic is what Harry Partch would call corporeality, an emphasis on the physical and the sensual including live, human, performance and improvisation, timbre, rhythm, and the sense of space in his melodic lines, whether solo or in counterpoint, and most notably in his frequent dance collaborations. The American dancer and choreographer Mark Morris used Harrison's Serenade for Guitar ith optional percussion(1978) as the "basis of a new kind of dance. Or, at least, one I've orrisnever seen or done before."

Harrison and Colvig built two full Javanese-style gamelan, modeled on the instrumentation of Kyai Udan Mas at U.C. Berkeley. One was named Si Betty for the art patron Betty Freeman; the other, built at Mills College, was named Si Darius/Si Madeliene. Harrison held the Darius Milhaud Chair of Musical Composition at Mills College from 1980 until his retirement in 1985. One of his students at Mills was Jin Hi Kim. He also taught at San Jose State University and Cabrillo College.

He was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal in 2000.

Among Harrison's better known works are the ''Concerto in Slendro'', Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra, Organ Concerto with Percussion (1973), which was given at the

An often used technique is "interval control", in which only small number of melodic intervals, either ascending or descending, are used, without inversion.Leta E. Miller and Fredric Lieberman (Summer 1999). "Lou Harrison and the American Gamelan", '' American Music'', vol. 17, no. 2, p. 168. For example, for the opening of the Fourth Symphony, the permitted intervals are minor third, minor sixth, and major second.

Another component of Harrison's aesthetic is what Harry Partch would call corporeality, an emphasis on the physical and the sensual including live, human, performance and improvisation, timbre, rhythm, and the sense of space in his melodic lines, whether solo or in counterpoint, and most notably in his frequent dance collaborations. The American dancer and choreographer Mark Morris used Harrison's Serenade for Guitar ith optional percussion(1978) as the "basis of a new kind of dance. Or, at least, one I've orrisnever seen or done before."

Harrison and Colvig built two full Javanese-style gamelan, modeled on the instrumentation of Kyai Udan Mas at U.C. Berkeley. One was named Si Betty for the art patron Betty Freeman; the other, built at Mills College, was named Si Darius/Si Madeliene. Harrison held the Darius Milhaud Chair of Musical Composition at Mills College from 1980 until his retirement in 1985. One of his students at Mills was Jin Hi Kim. He also taught at San Jose State University and Cabrillo College.

He was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal in 2000.

Among Harrison's better known works are the ''Concerto in Slendro'', Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra, Organ Concerto with Percussion (1973), which was given at the American Made – Books – Baltimore City Paper

and a Concerto for Piano and Javanese Gamelan; as well as four numbered orchestral symphonies. He also wrote a large number of works in non-traditional forms. Harrison was fluent in several languages including

Lou Harrison Archive

at the

San Jose State University School of Music & Dance

Lou Harrison music manuscripts, sketches, poetry, and drawings, 1945-1991

a

Isham Memorial Library, Harvard University

" April 1987. * Golden, Barbara

'' eContact!'' 12.2 – Interviews (2) (April 2010). Montréal: CEC.

New Albion Artists: Lou Harrison

Peermusic Classical: Lou Harrison

Composer's Publisher and Bio

from Frog Peak Music site

Other Minds: Lou Harrison

Lou Harrison Documentary Project

* ttps://sites.google.com/a/umich.edu/musa/publications/musa-8-lou-harrison Lou Harrisonat Music of the United States of America (MUSA)

Art of the States: Lou Harrison

seven works

Lou Harrison tribute

from Other Minds Festival 9, 2003

including tracks from ''Rhymes With Silver'' and ''La Koro Sutro''

with Harrison's ''Song of Palestine from String Quartet Set'' by

composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Def ...

, music critic

'' The Oxford Companion to Music'' defines music criticism as "the intellectual activity of formulating judgments on the value and degree of excellence of individual works of music, or whole groups or genres". In this sense, it is a branch of mu ...

, music theorist

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the " rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation ( ...

, painter

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ...

, and creator of unique musical instruments. Harrison initially wrote in a dissonant, ultramodernist style similar to his former teacher and contemporary, Henry Cowell

Henry Dixon Cowell (; March 11, 1897 – December 10, 1965) was an American composer, writer, pianist, publisher and teacher. Marchioni, Tonimarie (2012)"Henry Cowell: A Life Stranger Than Fiction" ''The Juilliard Journal''. Retrieved 19 June 202 ...

, but later moved toward incorporating elements of non-Western cultures into his work. Notable examples include a number of pieces written for Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

nese style gamelan

Gamelan () ( jv, ꦒꦩꦼꦭꦤ꧀, su, ᮌᮙᮨᮜᮔ᮪, ban, ᬕᬫᭂᬮᬦ᭄) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. T ...

instruments, inspired after studying with noted gamelan musician Kanjeng Notoprojo in Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

. Harrison would create his own musical ensembles and instruments with his partner, William Colvig

William (Bill) Colvig (March 13, 1917 – March 1, 2000) was an electrician and amateur musician who was the partner for 33 years of composer Lou Harrison, whom he met in San Francisco in 1967. Colvig helped construct the American gamelan used in ...

, who are now both considered founders of the American gamelan movement and world music; along with composers Harry Partch

Harry Partch (June 24, 1901 – September 3, 1974) was an American composer, music theorist, and creator of unique musical instruments. He composed using scales of unequal intervals in just intonation, and was one of the first 20th-century com ...

and Claude Vivier

Claude Vivier ( ; baptised as Claude Roger; 14 April 19487 March 1983) was a Canadian contemporary composer, pianist, poet and ethnomusicologist of Québécois origin. After studying with Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne, Vivier became an in ...

, and ethnomusicologist

Ethnomusicology is the study of music from the cultural and social aspects of the people who make it. It encompasses distinct theoretical and methodical approaches that emphasize cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dim ...

Colin McPhee.

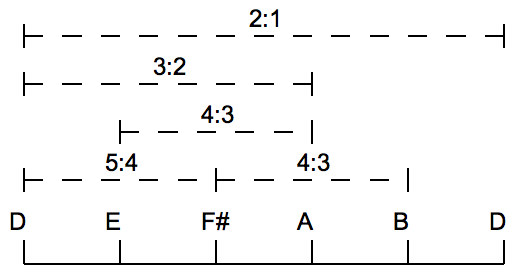

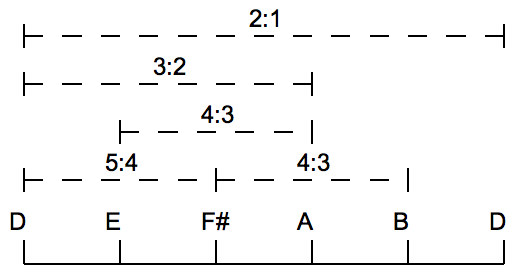

The majority of Harrison's works and custom instruments are written for just intonation

In music, just intonation or pure intonation is the tuning of musical intervals as whole number ratios (such as 3:2 or 4:3) of frequencies. An interval tuned in this way is said to be pure, and is called a just interval. Just intervals (and ...

rather than the more widespread equal temperament

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system, which approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into equal steps. This means the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same, ...

, making him one of the most prominent composers to have experimented with microtones. He was also one of the first composers to have written in the international language Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communic ...

, and among the first to incorporate strong themes of homosexuality

Homosexuality is Romance (love), romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romant ...

in his music.

Early life and career

Childhood

Harrison was born on May 14, 1917, in

Harrison was born on May 14, 1917, in Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...

, to parents Clarence "Pop" Harrison and former Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

resident Calline Lillian "Cal" Harrison (née Silver).Huizenga, Tom (2017)"Lou Harrison, The 'Maverick' Composer With Asia In His Ears"

''

NPR

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other ...

''. Retrieved June 29, 2022. The family was initially well-off financially from past inheritances, but fell on hard times leading up to the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Harrison lived in the Portland area for only nine years before moving with his parents and younger brother, Bill, to a number of locations in Northern California

Northern California (colloquially known as NorCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Spanning the state's northernmost 48 counties, its main population centers incl ...

, including Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

, Stockton, and finally, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

. With the city having a large population of Asian Americans

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous peopl ...

at the time, Harrison was often surrounded by the influence of the East. His mother decorated their home with Japanese lanterns, ornate Persian rugs

A Persian carpet ( fa, فرش ایرانی, translit=farš-e irâni ) or Persian rug ( fa, قالی ایرانی, translit=qâli-ye irâni ),Savory, R., ''Carpets'',(Encyclopaedia Iranica); accessed January 30, 2007. also known as Iranian ...

, and replicas of ancient Chinese artifacts. The diverse array of music he was exposed to there, including Cantonese opera

Cantonese opera is one of the major categories in Chinese opera, originating in southern China's Guangdong Province. It is popular in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau and among Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Like all versions of Ch ...

, Hawai'ian kīkākila, jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

, norteño and classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" al ...

, deeply fascinated and interested him. He would later say he had heard far more traditional Chinese music than European music by the time he was an adult.

Harrison's early interest in music was supported by his parents, with Cal paying for occasional piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

lessons and Pop driving the young Harrison to study traditional Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe dur ...

at the Mission San Francisco de Asís

Mission San Francisco de Asís ( es, Misión San Francisco de Asís), commonly known as Mission Dolores (as it was founded near the Dolores creek), is a Spanish Californian mission and the oldest surviving structure in San Francisco. Located i ...

for a short period. The family's frequent moves in search of work, however, provided the adolescent Harrison little opportunity to develop any long-term friendships. Often feeling like an outsider, he relied on his own judgment to guide his aesthetic decisions and decidedly drifted further and further away from the artistic style of the West. He instead retreated into furthering his own personal education, often spending time at the local library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

to read books on everything ranging from zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

to Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a Religious Confucianism, religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, ...

. He recalled being able to read two books a day, and the extremely wide diaspora of interests prompted him to connect disparate influences throughout his life, including in his future compositions. It's believed the loneliness of his youth contributed to his strong dislike of urban metropolises and so-called "city life".

Harrison discovered he was gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

while attending Burlingame High School and realizing his attraction toward a male classmate. By the time he graduated in December 1934 at the age of 17, he had come out to his family, and decided thereafter to make no attempt at hiding his sexual preference and personality; nearly unheard of for gay men

Gay men are male homosexuals. Some bisexual and homoromantic men may also dually identify as gay, and a number of young gay men also identify as queer. Historically, gay men have been referred to by a number of different terms, includin ...

of the time. Ross, Alex (2017)"New York Celebrates a Composer Who Left Town"

''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

''. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

First musical education

After graduating high school in 1934, Harrison enrolled in San Francisco State College (now

After graduating high school in 1934, Harrison enrolled in San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University (commonly referred to as San Francisco State, SF State and SFSU) is a public research university in San Francisco. As part of the 23-campus California State University system, the university offers 118 different ...

). It was there where he took Henry Cowell

Henry Dixon Cowell (; March 11, 1897 – December 10, 1965) was an American composer, writer, pianist, publisher and teacher. Marchioni, Tonimarie (2012)"Henry Cowell: A Life Stranger Than Fiction" ''The Juilliard Journal''. Retrieved 19 June 202 ...

's "Music of the Peoples of the World" course being offered by the UC Berkeley Extension

The University of California, Berkeley, Extension (UC Berkeley Extension) is the continuing education division of the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) campus. Founded in 1891, UC Berkeley Extension provides continuing education th ...

. Harrison quickly became one of Cowell's most enthusiastic students, and he subsequently appointed him as class assistant. After attending a Palo Alto

Palo Alto (; Spanish for "tall stick") is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city was es ...

performance of one of Cowell's pieces for piano and improvised percussion in June 1935, Harrison would proclaim it to be one of the most extraordinary works he had ever heard. He would later incorporate similar elements of found percussion and aleatoric

Aleatoricism or aleatorism, the noun associated with the adjectival aleatory and aleatoric, is a term popularised by the musical composer Pierre Boulez, but also Witold Lutosławski and Franco Evangelisti, for compositions resulting from "action ...

performance in his music. In fall of the same year, Harrison approached Cowell for private composition lessons, initiating a personal and professional friendship that continued until Cowell's death from cancer in 1965. He was the first to publish Harrison's music, through the publishing house he founded, New Music Edition. During Cowell's four year stay in San Quentin Prison on a morals charge involving homosexual acts, Harrison publicly appealed for his release, and regularly visited him for composition lessons through the prison's bars.

While still studying at age 19, he became an interim professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professo ...

of music at Mills College

Mills College at Northeastern University is a private college in Oakland, California and part of Northeastern University's global university system. Mills College was founded as the Young Ladies Seminary in 1852 in Benicia, California; it w ...

in Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay ...

from 1936 to 1939. In 1941, he transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the Californ ...

to work in the dance department; teaching students Laban movement analysis and playing piano accompaniment

Accompaniment is the musical part which provides the rhythmic and/or harmonic support for the melody or main themes of a song or instrumental piece. There are many different styles and types of accompaniment in different genres and styles o ...

. While there, he took theory lessons from Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, leading him to further his interest in the infamous twelve-tone technique

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law o ...

. Swed, Mark (2020)"Lou Harrison's generosity endures when we most need it"

''

Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

''. Retrieved June 27, 2022.Miller, Leta (2007)"Lou Harrison – In Retrospect"

''New World Records''. Retrieved June 25, 2022. He would later say, "... it was no jump at all to learn to write twelve-tone music; Henry's the one who taught me." The pieces he was writing at this time, however, were largely percussive works using unconventional materials, such as discarded car brake drums and

garbage cans

A waste container, also known as a dustbin, garbage can, and trash can is a type of container that is usually made out of metal or plastic. The words "rubbish", "basket" and "bin" are more common in British English usage; "trash" and "can" ...

, as musical instruments. Few of his surviving pieces – including one of the earliest known examples, Prelude for Grandpiano (1937) – follow the serialist twelve-tone idiom. He began using tone clusters in his piano works, à la Cowell, but differed from his technique by calling for an "octave bar" – a flat wooden bar approximately an octave long, with a slightly concave rubber bottom. This allowed the clusters to be much louder than they otherwise would be, and gave the piano more of an unpitched, gong

A gongFrom Indonesian and ms, gong; jv, ꦒꦺꦴꦁ ; zh, c=鑼, p=luó; ja, , dora; km, គង ; th, ฆ้อง ; vi, cồng chiêng; as, কাঁহ is a percussion instrument originating in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Gongs ...

-like sound. His experimental and free-wheeling style flourished during this period, with pieces like the Concerto for Violin and Percussion Orchestra (1940) and ''Labyrinth'' (1941). This ultramodern and avant-garde music captured the attention of John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading f ...

, another one of Cowell's students. Harrison and Cage would collaborate in the years following, and engage in several romantic liaisons.

New York years

Harrison was recommended several times to study musical composition in Paris – or Europe more broadly – but resolved several times against it, due to his staunch position of promoting and elevating the status of his fellow American composers. In 1943, Harrison moved to New York City and worked as a music critic for the ''Herald Tribune

''Herald'' or ''The Herald'' is the name of various newspapers.

''Herald'' or ''The Herald'' Australia

* ''The Herald'' (Adelaide) and several similar names (1894–1924), a South Australian Labor weekly, then daily

* '' Barossa and Light Heral ...

'' at the behest of fellow composer and tutor Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclass ...

. While there, he met and befriended many modernist composers of the East Coast, including Carl Ruggles

Carl Ruggles (born Charles Sprague Ruggles; March 11, 1876 – October 24, 1971) was an American composer, painter and teacher. His pieces employed "dissonant counterpoint", a term coined by fellow composer and musicologist Charles Seeger ...

, Alan Hovhaness

Alan Hovhaness (; March 8, 1911 – June 21, 2000) was an American- Armenian composer. He was one of the most prolific 20th-century composers, with his official catalog comprising 67 numbered symphonies (surviving manuscripts indicate over 70) a ...

, and most consequentially, Charles Ives

Charles Edward Ives (; October 20, 1874May 19, 1954) was an American modernist composer, one of the first American composers of international renown. His music was largely ignored during his early career, and many of his works went unperformed ...

. Harrison would later dedicate himself to bringing Ives to the attention of the musical world – whose works had largely been scoffed at or ignored up to that point. With the assistance of his mentor Cowell, he engraved

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an i ...

and conducted the premiere of Ives's Symphony No. 3 (1910); receiving financial help from Ives in return. When Ives won the Pulitzer Prize for Music

The Pulitzer Prize for Music is one of seven Pulitzer Prizes awarded annually in Letters, Drama, and Music. It was first given in 1943. Joseph Pulitzer arranged for a music scholarship to be awarded each year, and this was eventually converted ...

for that piece, he gave half of the money rewarded to Harrison. Harrison also edited a large number of Ives's works, receiving compensation often in excess of what he billed.

As fruitful as his creative endeavors were becoming, Harrison was fraught with loneliness and anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil and includes feelings of dread over anticipated events. Anxiety is different than fear in that the former is defined as the anticipation of a future threat wh ...

while in the city. A romantic relationship with a dancer in Los Angeles had to be terminated due to the move, a move which he had already begun to regret as he missed the West Coast more and more. By 1945, he had developed several painful ulcer

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughing o ...

s, which he could not seem to cure as his nervous condition worsened. Despite attempting to complete new music for publishing, many of them (including one from the commission of Ives) were violently torn up and blackened out by Harrison from an extreme lack of confidence as he began to internalize the negative opinions of his compositions and public image.

In May 1947, extreme stress from homesickness

Homesickness is the distress caused by being away from home.Kerns, Brumariu, Abraham. Kathryn A., Laura E., Michelle M.(2009/04/13). Homesickness at summer camp. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54. Its cognitive hallmark is preoccupying thoughts of home ...

, a vigorous work schedule and homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred or antipathy, m ...

colleagues culminated in a severe nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

. Cage came to Harrison's aid, assisting him and bringing him to a psychiatric clinic

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociative ...

in nearby Ossining. Harrison remained in the clinic for several weeks before transferring to the New York Presbyterian Hospital. He wrote frequently to Cowell and his wife Sidney in the first few months, expressing his deep regret and depression for what he felt to be a wasted career and adulthood. His recovery entailed nine months of extensive treatment and several more years of regular checkups, at the request of Harrison. Many of his colleagues predicted the breakdown would herald the end his career, but Harrison continued to compose in spite of the stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

plaguing him. While staying in the hospital, he composed several works, including much of his Symphony on G (1952), and regularly painted.

He decided, however, to return to California as soon as possible. In a 1948 letter addressed to his mother, Harrison wrote from the hospital, "I long to live simply and well and that just isn't possible here."

New life in California

New compositional style

The crisis during his New York years prompted Harrison to heavily reevaluate his compositional language and style. He ultimately rejected the dissonant idiom he had previously cultivated, and turned toward a more sophisticated melodic lyricism indiatonic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a ...

and pentatonic scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

. This put him sharply at odds with the then-current academic styles, and set him apart from the ultramodernist composers he had studied and associated with. The two years following his leave from the hospital in 1949 became one of the most productive of Harrison's entire career, yielding impressionistic

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passag ...

works such as the Suite for Cello and Harp, and ''The Perilous Chapel and Solstice''. Following in the path of Canadian-American composer and friend Colin McPhee, who had done extensive research in Indonesian music in the 1930s and wrote a number of compositions incorporating Balinese and Javanese elements, Harrison's style began emulating the influence of gamelan music more clearly, if only in timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voices and musica ...

: "It was the sound itself that attracted me. In New York, when I changed gears out of twelve tonalism, I explored this timbre. The gamelan movements in my Suite for Violin, Piano, and Small Orchestra 951are aural imitations of the generalized sounds of gamelan".

In the early 1950s, Harrison was given a first edition copy of Harry Partch

Harry Partch (June 24, 1901 – September 3, 1974) was an American composer, music theorist, and creator of unique musical instruments. He composed using scales of unequal intervals in just intonation, and was one of the first 20th-century com ...

's book on musical tuning

In music, there are two common meanings for tuning:

* Tuning practice, the act of tuning an instrument or voice.

* Tuning systems, the various systems of pitches used to tune an instrument, and their theoretical bases.

Tuning practice

Tun ...

, '' Genesis of a Music'' (1949) from Thomson. This prompted him to abandon equal temperament and begin writing music in just intonation

In music, just intonation or pure intonation is the tuning of musical intervals as whole number ratios (such as 3:2 or 4:3) of frequencies. An interval tuned in this way is said to be pure, and is called a just interval. Just intervals (and ...

. He strived to achieve powerful music using simple ratios, and would later consider music itself to be "emotional mathematics". In an oft-quoted comment referring to the frequency ratios used in just intonation, he said, "I'd long thought that I would love a time when musicians were numerate as well as literate. I'd love to be a conductor and say, 'Now, cellos, you gave me 10:9 there, please give me a 9:8 instead,' I'd love to get that!"

Teaching and time abroad

Harrison taught music at various colleges and universities, includingMills College

Mills College at Northeastern University is a private college in Oakland, California and part of Northeastern University's global university system. Mills College was founded as the Young Ladies Seminary in 1852 in Benicia, California; it w ...

from 1936 to 1939 and again from 1980 to 1985, San Jose State University

San José State University (San Jose State or SJSU) is a public university in San Jose, California. Established in 1857, SJSU is the oldest public university on the West Coast and the founding campus of the California State University (CSU) ...

, Cabrillo College

Cabrillo College is a public community college in Aptos, California. It is named after the conquistador Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo and opened in 1959. Cabrillo College has an enrollment of about 12,000 students per term.

Facilities

Classes are of ...

, Reed College

Reed College is a private liberal arts college in Portland, Oregon. Founded in 1908, Reed is a residential college with a campus in the Eastmoreland neighborhood, with Tudor-Gothic style architecture, and a forested canyon nature preserve at ...

, and Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College was a private liberal arts college in Black Mountain, North Carolina. It was founded in 1933 by John Andrew Rice, Theodore Dreier, and several others. The college was ideologically organized around John Dewey's educational ...

. In 1953 he moved back to California, settling in Aptos

Aptos (Ohlone languages, Ohlone for "The People") is an unincorporated area, unincorporated town in Santa Cruz County, California. The town is made up of several small villages, which together form Aptos: Aptos Hills-Larkin Valley, Aptos Village, ...

near Santa Cruz, where he lived the rest of his life. He and Colvig purchased land in Joshua Tree, California

Joshua Tree is a census-designated place (CDP) in San Bernardino County, California, United States. The population was 7,414 at the 2010 census. At approximately above sea level, Joshua Tree and its surrounding communities are located in the Hig ...

, where they designed and built the "Harrison House Retreat", a straw bale house. He continued working on his experimental musical instruments. Although much influenced by Asian music, Harrison did not visit the continent until a 1961 trip to Japan and Korea, and a 1962 trip to Taiwan (where he studied with the zheng master

Although much influenced by Asian music, Harrison did not visit the continent until a 1961 trip to Japan and Korea, and a 1962 trip to Taiwan (where he studied with the zheng master Liang Tsai-Ping Liang Tsai-Ping (, born Gaoyang County (), Hebei, China, February 23, 1910 or 1911; died Taipei, Taiwan, June 28, 2000) was a master of the '' guzheng'', a Chinese traditional zither. He is considered one of the 20th century's most important p ...

). He and his partner William Colvig later constructed a tuned percussion ensemble, using resonated aluminum keys and tubes, as well as oxygen tanks and other found percussion instruments. They called this "an American gamelan", in order to distinguish it from those in Indonesia. They also constructed gamelan-type instruments tuned to just pentatonic scales from unusual materials such as tin cans and aluminum furniture tubing. He wrote "La Koro Sutro" (in Esperanto)Lou Harrison Centennial Birthday Celebration1917–2017, part 2 of 5. for these instruments and chorus, as well as Suite for Violin and American Gamelan. In addition, Harrison played and composed for the Chinese

guzheng

The zheng () or gu zheng (), is a Chinese plucked zither. The modern guzheng commonly has 21, 25, or 26 strings, is long, and is tuned in a major pentatonic scale. It has a large, resonant soundboard made from '' Paulownia'' wood. Other ...

zither, and presented (with Colvig, his student Richard Dee, and the singer Lily Chin) over 300 concerts of traditional Chinese music in the 1960s.

He was a composer-in-residence at San Jose State University

San José State University (San Jose State or SJSU) is a public university in San Jose, California. Established in 1857, SJSU is the oldest public university on the West Coast and the founding campus of the California State University (CSU) ...

in San Jose, California

San Jose, officially San José (; ; ), is a major city in the U.S. state of California that is the cultural, financial, and political center of Silicon Valley and largest city in Northern California by both population and area. With a 2020 popu ...

, during the 1960s. The university honored him with an all-Harrison concert in Morris Daley Auditorium in 1969, featuring dancers, singers, and musicians. The highlight of the concert was the world premiere of Harrison's depiction of the story of Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

, which utilized soloists, the San Jose State University a cappella choir, as well as a unique group of percussionists.

Activism and other endeavors

Harrison was outspoken about his political views, such as his pacifism (he was an active supporter of the international languageEsperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communic ...

), and the fact that he was gay. He was also politically active and informed, including knowledge of gay history. He wrote many pieces with political texts or titles, writing, for instance, ''Homage to Pacifica'' for the opening of the Berkeley Headquarters of the Pacifica Foundation

Pacifica Foundation is an American non-profit organization that owns five independently operated, non-commercial, listener-supported radio stations known for their progressive/ liberal political orientation. Its national headquarters adjoins s ...

, and accepting commissions from the Portland Gay Men's Chorus (1988 and 1985) and by the Seattle Men's Chorus

Seattle Men's Chorus (SMC) is an LGBTQ community chorus based in Seattle, Washington. The group was founded in 1979, and today is, along with Seattle Women's Chorus, the largest community choral organization in North America. SMC is a member of ...

to arrange (1987) his ''Strict Songs'', originally for eight baritones, for "a chorus of 120 male singing enthusiasts. Some of them good; some not so good. But the number is so fabulous". Lawrence Mass describes:With Lou Harrison...being gay is something affirmative. He's proud to be a gay composer and interested in talking about what that might mean. He doesn't feel threatened that this means he won't be thought of as an American composer who is also great and timeless and universal.Janice Giteck describes Harrison as:

unabashedly androgynous in his way of approaching creativity. He has a vital connection to the feminine as well as to the masculine. The female part is apparent in the sense of beingness. But at the same time, Lou is very male, too, ferociously active and assertive, rhythmic, pulsing, and aggressive.Like many other 20th-century composers, Harrison found it hard to support himself with his music, and took a number of other jobs to earn a living, including record salesman, florist, animal nurse, and forestry firefighter.

Later life

On November 2, 1990, theBrooklyn Philharmonic

There have been several organisations referred to as the Brooklyn Philharmonic. The most recent one was the now-defunct Brooklyn Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, an American orchestra based in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, in existence ...

premiered Harrison's fourth symphony, which he titled "Last Symphony". He combined Native American music, ancient music, and Asian music, tying it all together with lush orchestral writing. A special inclusion was a series of Navajo "Coyote Stories". He made a number of revisions to the symphonies before completing a final version in 1995, which was recorded by Barry Jekowsky and the California Symphony for Argo Records

Argo Records was a record label in Chicago that was established in 1955 as a division of Chess Records.

Originally the label was called Marterry, but bandleader Ralph Marterie objected, and within a couple of months the imprint was renamed Arg ...

at Skywalker Ranch

Skywalker Ranch is a movie ranch and workplace of film director, writer and producer George Lucas located in a secluded area near Nicasio, California, in Marin County. The ranch is located on Lucas Valley Road, named for an early-20th-century l ...

in Nicasio, California, in March 1997. The CD also included Harrison's ''Elegy, to the Memory of Calvin Simmons'' (a tribute to the former conductor of the Oakland Symphony, who drowned in a boating accident in 1982), excerpts from ''Solstice'', ''Concerto in Slendro'', and ''Double Music'' (his collaboration with John Cage).

From the late 1980s onward, William Colvig's health began to dramatically deteriorate. He first lost his hearing, and Harrison's solution was for them to learn American Sign Language

American Sign Language (ASL) is a natural language that serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United States of America and most of Anglophone Canada. ASL is a complete and organized visual language that is expre ...

. Though Colvig decided not to communicate in ALS, Harrison continued to learn, as he was captivated by the dance-esque beauty of signing. A series of surgeries in the 1990's to replace Colvig's weak knee joints triggered a series of allergic reactions that led to significant degeneration of his physical and mental health. Harrison carefully nursed his partner, sitting with him for months, even after Colvig could no longer recognize Harrison due to his dementia

Dementia is a disorder which manifests as a set of related symptoms, which usually surfaces when the brain is damaged by injury or disease. The symptoms involve progressive impairments in memory, thinking, and behavior, which negatively affe ...

. Harrison was by Colvig's side when he died on March 1, 2000.

Death

Harrison and his recent partner Todd Burlingame were driving fromChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

en route to Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best pub ...

in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, an ...

, where a six-day festival showcasing his music – Beyond the Rockies: A Tribute to Lou Harrison at 85'– was scheduled for the week of January 30, 2003. On Sunday, February 2, they decided to stop off the highway at a Denny's

Denny's (also known as Denny's Diner on some of the locations' signage) is an American table service diner-style restaurant chain. It operates over 1,700 restaurants in many countries.

Description

Originally opened as a coffee shop under t ...

in Lafayette, Indiana

Lafayette ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, located northwest of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette, on the other side of the Wabash River, is home to Purdue University, whi ...

for lunch. While inside, Harrison began experiencing unexpected chest pains and collapsed on the scene. He was pronounced dead by the paramedics within minutes, the cause likely being from a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

, but no autopsy was performed. He was cremated as per his wishes.

Harrison's music

Overview

Many of Harrison's early works are for percussion instruments, often made out of what would usually be regarded as junk or found objects such as garbage cans and steel brake drums. He also wrote a number of pieces using Schoenberg's twelve tone technique, including the opera ''Rapunzel'' and his Symphony on G (Symphony No. 1) (1952). Several works feature thetack piano

A tack piano (also known as a harpsipiano, jangle piano, and junk piano) is an altered version of an ordinary piano, in which objects such as thumbtacks or nails are placed on the felt-padded hammers of the instrument at the point where the ha ...

, a kind of prepared piano

A prepared piano is a piano that has had its sounds temporarily altered by placing bolts, screws, mutes, rubber erasers, and/or other objects on or between the strings. Its invention is usually traced to John Cage's dance music for ''Works for p ...

with small nails inserted into the hammers to give the instrument a more percussive sound. Harrison's mature musical style is based on "melodicles", short motifs which are turned backwards and upside down to create a musical mode

In music theory, the term mode or ''modus'' is used in a number of distinct senses, depending on context.

Its most common use may be described as a type of musical scale coupled with a set of characteristic melodic and harmonic behaviors. It ...

the piece is based on. His music is typically spartan in texture but lyrical, and harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howeve ...

usually simple or sometimes lacking altogether, with the focus instead being on rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular re ...

and melody

A melody (from Greek μελῳδία, ''melōidía'', "singing, chanting"), also tune, voice or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combina ...

. Ned Rorem

Ned Rorem (October 23, 1923 – November 18, 2022) was an American composer of contemporary classical music and writer. Best known for his art songs, which number over 500, Rorem was the leading American of his time writing in the genre. Althoug ...

describes, "Lou Harrison's compositions demonstrate a variety of means and techniques. In general he is a melodist. Rhythm has a significant place in his work, too. Harmony is unimportant, although tonality is. He is one of the first American composers to successfully create a workable marriage between Eastern and Western forms."

An often used technique is "interval control", in which only small number of melodic intervals, either ascending or descending, are used, without inversion.Leta E. Miller and Fredric Lieberman (Summer 1999). "Lou Harrison and the American Gamelan", '' American Music'', vol. 17, no. 2, p. 168. For example, for the opening of the Fourth Symphony, the permitted intervals are minor third, minor sixth, and major second.

Another component of Harrison's aesthetic is what Harry Partch would call corporeality, an emphasis on the physical and the sensual including live, human, performance and improvisation, timbre, rhythm, and the sense of space in his melodic lines, whether solo or in counterpoint, and most notably in his frequent dance collaborations. The American dancer and choreographer Mark Morris used Harrison's Serenade for Guitar ith optional percussion(1978) as the "basis of a new kind of dance. Or, at least, one I've orrisnever seen or done before."

Harrison and Colvig built two full Javanese-style gamelan, modeled on the instrumentation of Kyai Udan Mas at U.C. Berkeley. One was named Si Betty for the art patron Betty Freeman; the other, built at Mills College, was named Si Darius/Si Madeliene. Harrison held the Darius Milhaud Chair of Musical Composition at Mills College from 1980 until his retirement in 1985. One of his students at Mills was Jin Hi Kim. He also taught at San Jose State University and Cabrillo College.

He was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal in 2000.

Among Harrison's better known works are the ''Concerto in Slendro'', Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra, Organ Concerto with Percussion (1973), which was given at the

An often used technique is "interval control", in which only small number of melodic intervals, either ascending or descending, are used, without inversion.Leta E. Miller and Fredric Lieberman (Summer 1999). "Lou Harrison and the American Gamelan", '' American Music'', vol. 17, no. 2, p. 168. For example, for the opening of the Fourth Symphony, the permitted intervals are minor third, minor sixth, and major second.

Another component of Harrison's aesthetic is what Harry Partch would call corporeality, an emphasis on the physical and the sensual including live, human, performance and improvisation, timbre, rhythm, and the sense of space in his melodic lines, whether solo or in counterpoint, and most notably in his frequent dance collaborations. The American dancer and choreographer Mark Morris used Harrison's Serenade for Guitar ith optional percussion(1978) as the "basis of a new kind of dance. Or, at least, one I've orrisnever seen or done before."

Harrison and Colvig built two full Javanese-style gamelan, modeled on the instrumentation of Kyai Udan Mas at U.C. Berkeley. One was named Si Betty for the art patron Betty Freeman; the other, built at Mills College, was named Si Darius/Si Madeliene. Harrison held the Darius Milhaud Chair of Musical Composition at Mills College from 1980 until his retirement in 1985. One of his students at Mills was Jin Hi Kim. He also taught at San Jose State University and Cabrillo College.

He was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal in 2000.

Among Harrison's better known works are the ''Concerto in Slendro'', Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra, Organ Concerto with Percussion (1973), which was given at the Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

in London in 1997; the Double Concert' (1981–82) for violin, cello, and Javanese gamelan; the Piano Concerto (1983–85) for piano tuned in Kirnberger #2 (a form of well temperament) and orchestra, which was written for Keith Jarrett

Keith Jarrett (born May 8, 1945) is an American jazz and classical music pianist and composer. Jarrett started his career with Art Blakey and later moved on to play with Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis. Since the early 1970s, he has also been a ...

;American Sign Language

American Sign Language (ASL) is a natural language that serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United States of America and most of Anglophone Canada. ASL is a complete and organized visual language that is expre ...

, Mandarin and Esperanto, and several of his pieces have Esperanto titles and texts, most notably ''La Koro Sutro'' (1973).

Like Charles Ives, Harrison completed four symphonies. He typically combined a variety of the musical forms and languages that he preferred. This is quite apparent in the fourth symphony, recorded by the California Symphony for Argo Records, as well as his third symphony, which was performed and broadcast by Dennis Russell Davies

Dennis Russell Davies (born April 16, 1944 in Toledo, Ohio) is an American conductor and pianist, He is currently the music director and chief conductor of the Brno Philharmonic.

Biography

Davies studied piano and conducting at the Juilliard Sch ...

and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. Russell Davies also recorded the third symphony with the Cabrillo Music Festival orchestra.

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Archives

Lou Harrison Archive

at the

University of California, Santa Cruz

The University of California, Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz or UCSC) is a public land-grant research university in Santa Cruz, California. It is one of the ten campuses in the University of California system. Located on Monterey Bay, on the ed ...

San Jose State University School of Music & Dance

Lou Harrison music manuscripts, sketches, poetry, and drawings, 1945-1991

a

Isham Memorial Library, Harvard University

Interviews

* Duffie, Bruce." April 1987. * Golden, Barbara

'' eContact!'' 12.2 – Interviews (2) (April 2010). Montréal: CEC.

Other links

New Albion Artists: Lou Harrison

Peermusic Classical: Lou Harrison

Composer's Publisher and Bio

from Frog Peak Music site

Other Minds: Lou Harrison

Lou Harrison Documentary Project

* ttps://sites.google.com/a/umich.edu/musa/publications/musa-8-lou-harrison Lou Harrisonat Music of the United States of America (MUSA)

Listening

Art of the States: Lou Harrison

seven works

Lou Harrison tribute

from Other Minds Festival 9, 2003

including tracks from ''Rhymes With Silver'' and ''La Koro Sutro''

with Harrison's ''Song of Palestine from String Quartet Set'' by

Del Sol Quartet

The Del Sol Quartet is a string quartet based in San Francisco, California that was founded in 1992 by violist Charlton Lee.

Del Sol has commissioned and premiered thousands of works from a diverse range of international composers, including Terr ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Harrison, Lou

1917 births

2003 deaths

20th-century American composers

20th-century American conductors (music)

20th-century American educators

20th-century American inventors

20th-century American male musicians

20th-century American musicians

20th-century American painters

20th-century American pianists

20th-century classical composers

20th-century classical pianists

20th-century LGBT people

20th-century American musicologists

21st-century LGBT people

Activists from California

American civil rights activists

American avant-garde musicians

American classical composers

American contemporary classical composers

American Esperantists

American experimental musicians

American gay musicians

American male classical composers

American male conductors (music)

American male painters

American multi-instrumentalists

American music critics

American music theorists

American opera composers

American people of English descent

American people of Scottish descent

American poets

Black Mountain College faculty

Classical musicians from California

Classical musicians from Oregon

Composers for piano

Contemporary classical music performers

Esperanto music

Experimental composers

Guzheng players

Gamelan musicians

Just intonation composers

Lecturers

LGBT artists from the United States

LGBT classical composers

LGBT classical musicians

American LGBT musicians

LGBT people from California

LGBT people from Oregon

LGBT rights activists from the United States

LGBT songwriters

Male opera composers

Mills College faculty

Modernist composers

Music & Arts artists

Music theorists

Musicians from Los Angeles

Musicians from Portland, Oregon

Musicians from San Francisco

People from Aptos, California

People from San Francisco

Philosophers of music

Poets from California

Pupils of Arnold Schoenberg

Pupils of Henry Cowell

Pupils of Virgil Thomson

Pupils of K. P. H. Notoprojo

Radical Faeries members

Twelve-tone and serial composers