The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider

East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the

City of London and north of the

River Thames. It does not have universally accepted boundaries to the north and east, though the

River Lea is sometimes seen as the eastern boundary. Parts of it may be regarded as lying within

Central London

Central London is the innermost part of London, in England, spanning several boroughs. Over time, a number of definitions have been used to define the scope of Central London for statistics, urban planning and local government. Its character ...

(though that term too has no precise definition). The term "East of

Aldgate Pump" is sometimes used as a synonym for the area.

The East End began to emerge in the Middle Ages with initially slow urban growth outside the eastern walls, which later accelerated, especially in the 19th century, to absorb pre-existing settlements. The first known written record of the East End as a distinct entity, as opposed to its component parts, comes from

John Strype

John Strype (1 November 1643 – 11 December 1737) was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and l ...

's 1720 ''Survey of London'', which describes London as consisting of four parts: the City of London,

Westminster,

Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, and "That Part beyond the Tower". The relevance of Strype's reference to the

Tower was more than geographical. The East End was the urbanised part of an administrative area called the

Tower Division, which had owed military service to the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

since time immemorial. Later, as London grew further, the fully urbanised Tower Division became a byword for wider East London, before East London grew further still, east of the

River Lea and into

Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Gr ...

.

The area was notorious for its deep poverty, overcrowding and associated social problems. This led to the East End's history of intense political activism and association with some of the country's most influential social reformers. Another major theme of East End history has been migration, both inward and outward. The area had a strong pull on the rural poor from other parts of England, and attracted waves of migration from further afield, notably

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

refugees,

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

weavers,

Ashkenazi Jews and in the 20th century,

Bengalis

Bengalis (singular Bengali bn, বাঙ্গালী/বাঙালি ), also rendered as Bangalee or the Bengali people, are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the Bengal region of S ...

.

The closure of the last of the

Port of London's East End docks in 1980 created further challenges and led to attempts at regeneration, with

Canary Wharf

Canary Wharf is an area of London, England, located near the Isle of Dogs in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Canary Wharf is defined by the Greater London Authority as being part of London's central business district, alongside Central Lon ...

and the

Olympic Park

An Olympic Park is a sports campus for hosting the Olympic Games. Typically it contains the Olympic Stadium and the International Broadcast Centre. It may also contain the Olympic Village or some of the other sports venues, such as the aquatics c ...

[''Olympic Park: Legacy'']

(London 2012) accessed 20 September 2007 among the most successful examples. While some parts of the East End are undergoing rapid change, the area continues to contain some of the worst poverty in Britain.

[Chris Hammett ''Unequal City: London in the Global Arena'' (2003) Routledge ]

Uncertain boundaries

The East End lies east of the

Roman and medieval walls of the

City of London and north of the

River Thames.

Aldgate Pump on the edge of the

City is regarded as the symbolic start of the East End. On the river, the

Tower Dock inlet, just west of the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

and

Tower Bridge marks the beginning of the

London Borough of Tower Hamlets and its older predecessors.

Beyond these reference points, the East End has no official or generally accepted boundaries; views vary as to how much of wider

East London lies within it.

In extending from the line of the former walls, the area is taken to include the small ancient extramural

City wards

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

of

Bishopsgate Without and the

Portsoken

Portsoken, traditionally referred to with the definite article as the Portsoken, is one of the City of London's 25 ancient wards, which are still used for local elections. Historically an extra-mural Ward, lying east of Aldgate and the City wall ...

(as established until 21st century boundary reviews). The various channels of the

River Lea are sometimes viewed as the eastern boundary.

The New Oxford Dictionary of English

The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' (''ODE'') is a single-volume English dictionary published by Oxford University Press, first published in 1998 as ''The New Oxford Dictionary of English'' (''NODE''). The word "new" was dropped from the titl ...

(1998) – p.582 "East End the part of London east of the City as far as the River Lea, including the Docklands".

Beyond the small eastern extramural wards, the narrowest definition restricts the East End to the modern

London Borough of Tower Hamlets. A more common preference is to add to Tower Hamlets the former parish and borough of

Shoreditch (including

Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. As a part of Shoreditch, it is often considered to be part of the East End – the historic core of wider East London. It was historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. It l ...

and

Haggerston

Haggerston is a locale in East London, England, centred approximately on Great Cambridge Street (now renamed Queensbridge Road). It is within the London Borough of Hackney and is considered to be a part of London's East End. It is about 3.1 miles ...

), which is now the southern part of the modern

London Borough of Hackney

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a maj ...

.

[ Other commentators prefer a definition broader still, encompassing districts such as West Ham,]["Londoners Over the Border", in ''Household Words'' Charles Dickens 390](_blank)

12 September 1857 (Newham archives) accessed 18 September 2007

East Ham,

Development and economy

Origins

The East End developed along the Thames, and beyond Bishopsgate

Bishopsgate was one of the eastern gates in London's former defensive wall. The gate gave its name to the Bishopsgate Ward of the City of London. The ward is traditionally divided into ''Bishopsgate Within'', inside the line wall, and ''Bisho ...

and Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London. It gives its name to Aldgate High Street, the first stretch of the A11 road, which included the site of the former gate.

The area of Aldgate, the most common use of ...

, the gates in the city wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

that lay east of the little Walbrook

Walbrook is a City ward and a minor street in its vicinity. The ward is named after a river of the same name.

The ward of Walbrook contains two of the City's most notable landmarks: the Bank of England and the Mansion House. The street runs ...

river. These gates, first built with the wall in the late second or early third centuries, secured the entrance of pre-existing roads (the modern A10 and A11/A12) into the walled area. The walls were such a constraint to growth, that the position of the gates has been fundamental to the shaping of the capital, especially in the then suburbs outside the wall.

The walled City was built on two hills separated by the Walbrook

Walbrook is a City ward and a minor street in its vicinity. The ward is named after a river of the same name.

The ward of Walbrook contains two of the City's most notable landmarks: the Bank of England and the Mansion House. The street runs ...

, Ludgate Hill to the west and Cornhill (of which Tower Hill is a shoulder), to the east.Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London. It gives its name to Aldgate High Street, the first stretch of the A11 road, which included the site of the former gate.

The area of Aldgate, the most common use of ...

was held by the Cnichtengild

The ''Knighten Guilde'' or ''Cnichtengild'', which loosely translates into modern English as the Knight's Guild, was an obscure Medieval guild of the City of London, according to '' A Survey of London'' by John Stow (1603) in origin an order of chi ...

, a fighting organisation responsible for the defence of Aldgate and the nearby walls. The land inside and outside Bishopsgate seems to have been the responsibility of the Bishop of London (the Bishop of the East Saxons

la, Regnum Orientalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the East Saxons

, common_name = Essex

, era = Heptarchy

, status =

, status_text =

, government_type = Monarc ...

), who was promoting building in the underdeveloped eastern side of the walled area, and who may also have had a role in defending Bishopsgate itself. Apart from parts of Shoreditch, the rest of the area was part of the Bishop of London's Manor of Stepney. The Manor's lands were the basis of a later unit called the Tower Division, or Tower Hamlets which extended as far north as Stamford Hill

Stamford Hill is an area in Inner London, England, about 5.5 miles north-east of Charing Cross. The neighbourhood is a sub-district of Hackney, the major component of the London Borough of Hackney, and is known for its Hasidic community, the l ...

. It is thought that the manor was held by the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, in compensation for his duties in maintaining and garrisoning the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. The oldest recorded reference to this obligation is from 1554, but it is thought to pre-date that by centuries.

These landholdings would become the basis of the Ancient Parishes

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

and City Wards which, by occasional fission and mergers, developed into the administrative units of today.

Five monastic institutions, centres of learning and charity, were established just outside the walls:

Five monastic institutions, centres of learning and charity, were established just outside the walls: Bedlam

Bedlam, a word for an environment of insanity, is a term that may refer to:

Places

* Bedlam, North Yorkshire, a village in England

* Bedlam, Shropshire, a small hamlet in England

* Bethlem Royal Hospital, a London psychiatric institution and the ...

, Holywell Priory

Holywell Priory or Haliwell, Halliwell, or Halywell (various spellings), was a religious house in Shoreditch, formerly in the historical county of Middlesex and now in the London Borough of Hackney. Its formal name was the Priory of St John the B ...

, The New Hospital of St Mary without Bishopsgate, the Abbey of the Minoresses of St. Clare without Aldgate, Eastminster near the Tower, and St Katherine's on the Thames.

Bromley

Bromley is a large town in Greater London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley. It is south-east of Charing Cross, and had an estimated population of 87,889 as of 2011.

Originally part of Kent, Bromley became a market town, cha ...

was home to St Leonards Priory and Barking Abbey

Barking Abbey is a former royal monastery located in Barking, in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. It has been described as having been "one of the most important nunneries in the country".

Originally established in the 7th century, f ...

, important as a religious centre since Norman times was where William the Conqueror had first established his English court. Further east the Cistercian Stratford Langthorne Abbey

Stratford Langthorne Abbey, or the Abbey of St Mary's, Stratford Langthorne was a Cistercian monastery founded in 1135 at Stratford Langthorne — then Essex but now Stratford in the London Borough of Newham. The Abbey, also known as West Ha ...

became the court of Henry III in 1267 for the visitation of the Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholi ...

s, and it was here that he made peace with the barons under the terms of the Dictum of Kenilworth. It became the fifth largest Abbey in the country, visited by monarchs and providing a retreat (and a final resting place) for the nobility. Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal ...

held his parliament at Stepney in 1299.

The lands east of the City have sometimes been used as hunting grounds for bishops and royalty. The Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

had a palace at Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in the East End of London northeast of Charing Cross. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the Green, much of which survives today as Bethnal Green Gardens, beside Cambridge Heath Road. By t ...

, King John is ''reputed'' to have established a palace at Bow and Henry VIII established a hunting lodge at Bromley Hall

Bromley Hall is an early Tudor period manor house in Bromley-by-Bow, Tower Hamlets, London. Located on the Blackwall Tunnel northern approach road, it is now owned and restored by Leaside Regeneration. Built around 1485, it is thought to be the ol ...

.

The rural population of the area grew considerably in the Medieval period, despite reductions caused by the Norman Conquest and the Black Death. The pattern of agricultural settlement in south-east England was typically of dispersed farmhouses, rather than nucleated villages. However the presence of the city and maritime trades as a market for goods and services led to a thriving mixed economy in the countryside of the Manor of Stepney. This led to large settlements, inhabited mostly by tradesmen (rather than farmers) to develop along the major roads forming hamlets such as Mile End and Bow. These settlements would expand and merge with the development radiating out from London itself.

Emergence and character

Geography was a major factor influencing the character of the developing East End; prevailing winds flow, like the river, west to east. The flow of the river led to the maritime trades concentrating in the east and the prevailing wind encouraged the most polluting industries to concentrate eastwards.

Metal working industries are recorded between Aldgate and Bishopsgate in the 1300s and ship building for the navy is recorded at Ratcliff

Ratcliff or Ratcliffe is a locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames between Limehouse (to the east), and Shadwell (to the west). The place name is no longer commonly used.

History

Etymolog ...

in 1354, with shipfitting and repair carried out in Blackwall by 1485 and a major fishing port developed downstream at Barking to provide fish for the City. These and other factors meant that industries relating to construction, repair, and victualling of naval and merchant ships flourished in the area but the City of London retained its right to land the goods, until 1799.

Growth was much slower in the east, than in the large western suburb, with the modest eastern suburb separated from the much smaller northern extension by Moorfields adjacent to the wall on the north side. Moorfields was an open area with a marshy chararacter due to London's Wall acting as a dam, impeding the flow of the Walbrook and restricting development in that direction. Moorfields remained open until 1817, and the longstanding presence of that open space separating the emerging East End from the western and small northern suburb must have helped shape the different economic character of the areas and perceptions of their distinct identity (see map below). Shoreditch's boundary with the parish of St Luke's (which, like its predecessor St Giles-without-Cripplegate served the Finsbury area) ran through the Moorfields countryside. These boundaries remained consistent after urbanisation and so might be said to delineate east and north London. The boundary line, with very slight modifications, has also become the boundary between the modern London Boroughs of Hackney and Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the a ...

.

Building accelerated in the late 16th century, and the area that would later become known as the East End began to take shape. Writing in 1603, John Stow described the squalid riverside development, extending nearly as far as Ratcliff

Ratcliff or Ratcliffe is a locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames between Limehouse (to the east), and Shadwell (to the west). The place name is no longer commonly used.

History

Etymolog ...

, which had developed mostly within in his lifetime.

The polluted nature of the area was noted by

The polluted nature of the area was noted by Sir William Petty

Sir William Petty FRS (26 May 1623 – 16 December 1687) was an English economist, physician, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to sur ...

in 1676, at a time when unpleasant smells were considered a vector of disease. He called for London's centre of gravity to move further west from the City towards Westminster, upwind what he called ''“the fumes steams and stinks of the whole easterly pyle"''.

In 1703 Joel Gascoyne

Joel Gascoyne (bap. 1650—c. 1704) was an English nautical chartmaker, land cartographer and surveyor who set new standards of accuracy and pioneered large scale county maps. After achieving repute in the Thames school of chartmakers, he switc ...

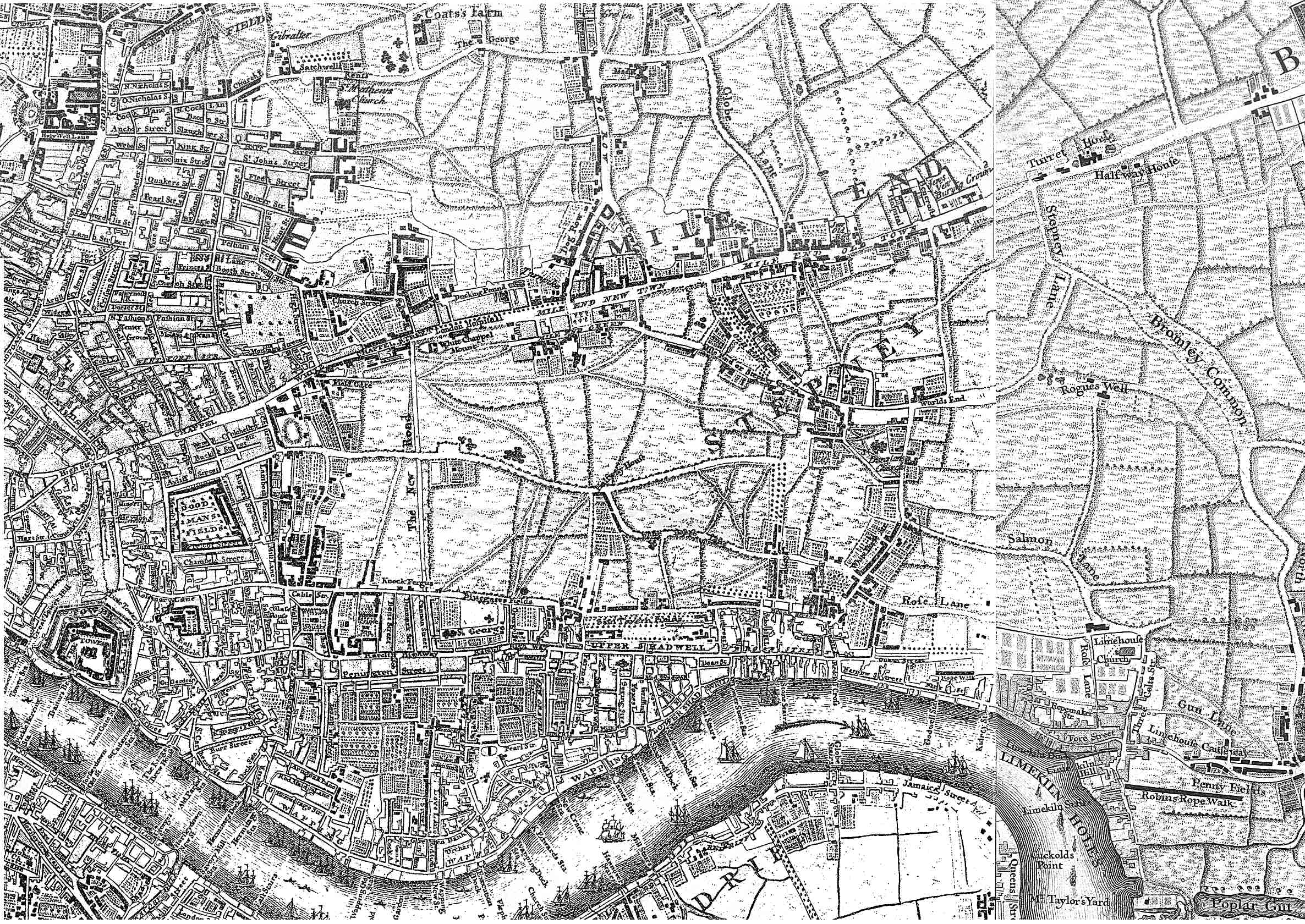

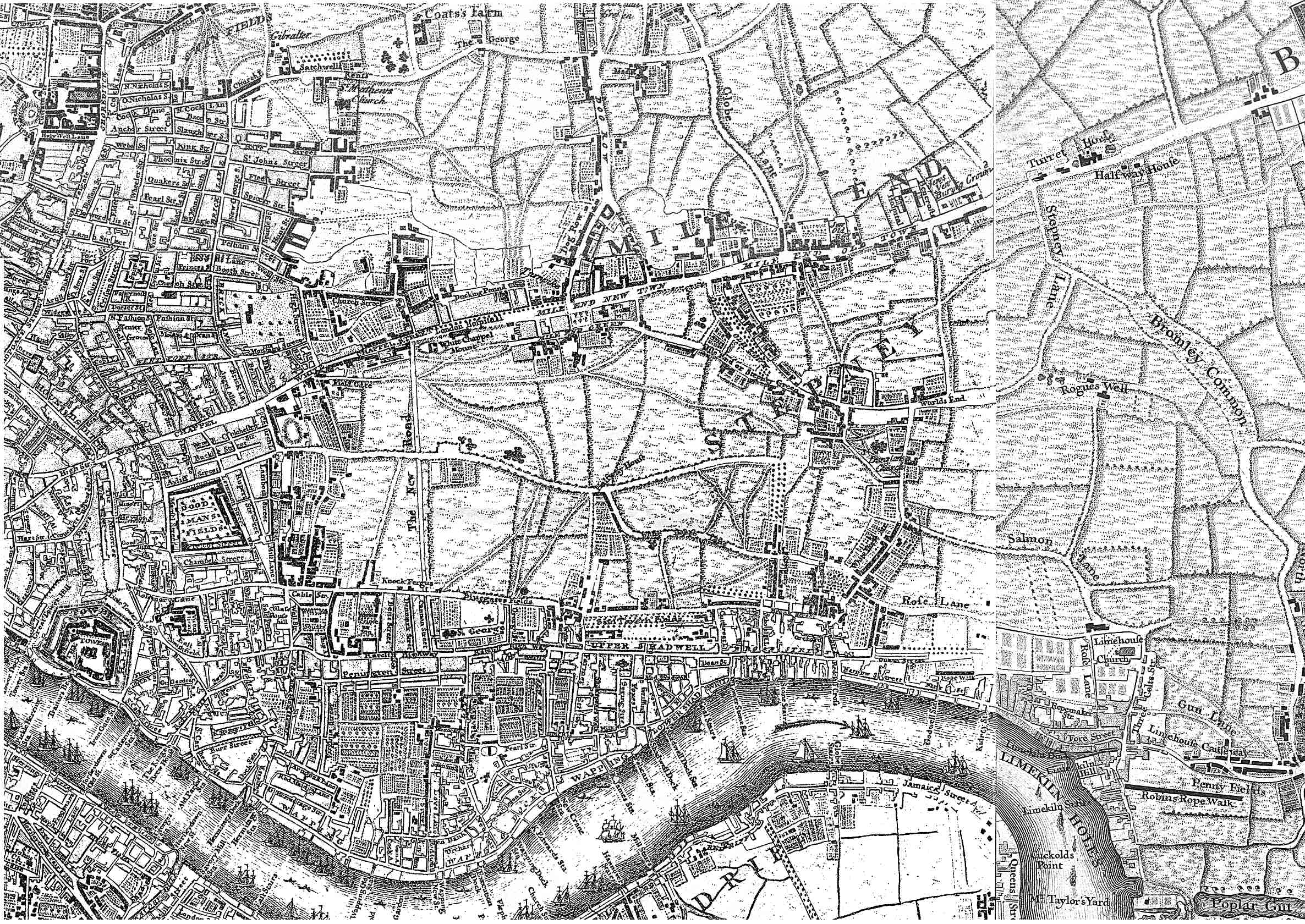

published his map of the parish of St Dunstan Stepney, which occupied much of the East End area. He was commissioned to do so by the Vestry (local government) of the parish, who needed such a map for administrative purposes. The map shows Stepney divided into ''Hamlets'', these were territorial sub-divisions, rather than small villages, and later became independent daughter parishes in their own right.[Young's guide describes Hamlets as devolved areas of Parishes - but does not describe this area specifically ]

In 1720 John Strype

John Strype (1 November 1643 – 11 December 1737) was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and l ...

gives us our first record of the East End as a distinct entity, rather than a collection of parishes, when he describes London as consisting of four parts: the City of London, Westminster, Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, and ''"That Part beyond the Tower"''.

The relevance of Strype's reference to the Tower was more than geographical. The East End (including the Tower and its Liberties) was the urbanised part of an administrative area called the Tower Division, which had owed military service to the Constable of the Tower

The Constable of the Tower is the most senior appointment at the Tower of London. In the Middle Ages a constable was the person in charge of a castle when the owner—the king or a nobleman—was not in residence. The Constable of the Tower had a ...

(in his ex-officio role as Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets

This is a list of people who have served as Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets.

The Lord Lieutenancy was created in 1660 at the Restoration. It was generally held by the Constable of the Tower of London. Lieutenants were appointed until 1889, ...

) for time immemorial, having its roots in the Bishop of London's historic Manor of Stepney. This made the Constable an influential figure in the civil and military affairs of the early East End. Later, as London grew further, the fully urbanised Tower Division became a byword for wider East London, before East London grew further still, east of the River Lea and into Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Gr ...

.

The contrast between the east and west ends was stark, in 1797 the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

n writer and historian Archenholz wrote:

Writing of the period around 1800, Rev. Richardson commented on the estrangements between the east and west:

The East End has always contained some of London's poorest areas. The main reasons for this include:

*The medieval system of copyhold

Copyhold was a form of customary land ownership common from the Late Middle Ages into modern times in England. The name for this type of land tenure is derived from the act of giving a copy of the relevant title deed that is recorded in the ...

, which prevailed throughout the Manor of Stepney into the 19th century. There was little point in developing land that was held on short leases.[

*The siting of noxious industries, such as tanning and fulling downwind outside the boundaries of the City, and therefore beyond complaints and official controls. The foul-smelling industries partially preferred the East End because the prevailing winds in London traveled from west to east (i.e. it was downwind from the rest of the city), so that most odours from their businesses would not go into the city.

*The low paid employment in the docks and related industries, made worse by the trade practices of outwork, ]piecework

Piece work (or piecework) is any type of employment in which a worker is paid a fixed piece rate for each unit produced or action performed, regardless of time.

Context

When paying a worker, employers can use various methods and combinations of ...

and casual labour.

*The concentration of the ruling court and national political centre in Westminster, on the opposite, western side of the City of London.

In medieval times trades were carried out in workshops in and around the owners' premises in the City. By the time of the Great Fire of London in 1666 these were becoming industries, and some were particularly noisome, such as the processing of urine for the tanning industry, or required large amounts of space, such as drying clothes after process and dying in fields known as tentergrounds. Some were dangerous, such as the manufacture of gunpowder or the proving of guns. These activities came to be performed outside the City walls in the near suburbs of the East End. Later, when lead-making and bone-processing for soap and china came to be established, they too located in the East End rather than in the crowded streets of the City.[

In 1817 the Lower Moorfields was built on and the gap with Finsbury was fully closed, and in the late 19th century development across the Lea in West Ham began in earnest.

As time went on, large estates began to be split up, ending the constraining effect of short-term copyhold.][''Stepney, Old and New London: Volume 2'' (1878), pp. 137-142]

accessed: 17 November 2007 Estates of fine houses for captains, merchants and owners of manufacturers began to be built. Samuel Pepys moved his family and goods to Bethnal Green during the Great Fire of London, and Captain Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

moved from Shadwell to Stepney Green

Stepney Green Park is a park in Stepney, Tower Hamlets, London. It is a remnant of a larger area of common land. It was formerly known as Mile End Green. A Crossrail construction site occupies part of the green, with Stepney Green cavern belo ...

, where a school and assembly rooms had been established (commemorated by ''Assembly Passage'', and a plaque on the site of Cook's house on the Mile End Road). Mile End Old Town also acquired some fine buildings, and the New Town began to be built.

By 1882, Walter Besant was able to describe East London as a city in its own right, on account of its large size and social disengagement from the rest of the capital.

Accelerated 19th-century development

As the area became built up and more crowded, the wealthy sold their plots for subdivision and moved further afield. Into the 18th and 19th centuries, there were still attempts to build fine houses, for example Tredegar Square

Tredegar Square pronounced is a well-preserved Georgian square in Mile End, and is in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The square has gardens in the centre with lawns and large trees.

Location

Tredegar Square is 90 metres north of m ...

(1830), and the open fields around Mile End New Town were used for the construction of estates of workers' cottages in 1820. This was designed in 1817 in Birmingham by Anthony Hughes and finally constructed in 1820.[''What lies beneath ... East End of London'']

East London History Society accessed 5 October 2007

Globe Town was established from 1800 to provide for the expanding population of weavers around Bethnal Green, attracted by improving prospects in silk weaving. Bethnal Green's population trebled between 1801 and 1831, with 20,000 looms being operated in people's own homes. By 1824, with restrictions on importation of French silks relaxed, up to half these looms had become idle, and prices were driven down. With many importing warehouses already established in the district, the abundance of cheap labour was turned to boot, furniture and clothing manufacture.[ Globe Town continued its expansion into the 1860s, long after the silk industry's decline.

]

During the 19th century, building on an ''ad hoc'' basis could not keep up with the expanding population's needs. Henry Mayhew visited Bethnal Green in 1850 and wrote for the '' Morning Chronicle'', as a part of a series forming the basis for ''

During the 19th century, building on an ''ad hoc'' basis could not keep up with the expanding population's needs. Henry Mayhew visited Bethnal Green in 1850 and wrote for the '' Morning Chronicle'', as a part of a series forming the basis for ''London Labour and the London Poor

''London Labour and the London Poor'' is a work of Victorian journalism by Henry Mayhew. In the 1840s, he observed, documented and described the state of working people in London for a series of articles in a newspaper, the ''Morning Chronicle'', ...

'' (1851), that the trades in the area included tailors, costermonger

A costermonger, coster, or costard is a street seller of fruit and vegetables in British towns. The term is derived from the words '' costard'' (a medieval variety of apple) and ''monger'' (seller), and later came to be used to describe hawkers i ...

s, shoemakers, dustmen, sawyers, carpenters, cabinet makers and silkweavers. He noted that in the area:

A movement began to clear the slums. Burdett-Coutts built Columbia Market in 1869 and the " Artisans' and Labourers' Dwelling Act" passed in 1876 to provide powers to seize slums from landlords and to provide access to public funds to build new housing. Philanthropic housing associations such as the Peabody Trust were formed to provide homes for the poor and to clear the slums generally. Expansion by the railway companies, such as the London and Blackwall Railway

Originally called the Commercial Railway, the London and Blackwall Railway (L&BR) in east London, England, ran from Minories to Blackwall via Stepney, with a branch line to the Isle of Dogs, connecting central London to many of London's dock ...

and Great Eastern Railway, caused large areas of slum housing to be demolished. The Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890

The Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890 ( 53 & 54 Vict. c. 70) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Background

The Housing of the Working Classes Act 1885 was a public health act, not a housing act. It empowered local authoriti ...

, gave local authorities, notably London County Council, new powers and responsibilities and led to the building of new philanthropic housing such as Blackwall Buildings and Great Eastern Buildings.

By 1890, official slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

programmes had begun. These included the creation of the world's first council housing, the LCC Boundary Estate

The Boundary Estate is a housing development in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London.

It is positioned just inside Bethnal Green's historic parish and borough boundary with Shoreditch, which ran along ''Boundary Stre ...

, which replaced the neglected and crowded streets of Friars Mount, better known as The Old Nichol Street Rookery. Between 1918 and 1939 the LCC continued replacing East End housing with five- or six-storey flats, despite residents preferring houses with gardens and opposition from shopkeepers who were forced to relocate to new, more expensive premises. The Second World War brought an end to further slum clearance.[''Bethnal Green: Building and Social Conditions from 1915 to 1945'', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 132-135]

accessed: 10 October 2007

Industry and innovation

Industries associated with the sea developed throughout the East End, including rope making and shipbuilding. The former location of roperies can still be identified from their long straight, narrow profile in the modern streets, for instance Ropery Street near Mile End. Shipbuilding for the navy is recorded at Ratcliff in 1354, with shipfitting and repair carried out in Blackwall by 1485. On 31 January 1858, the largest ship of that time, the SS Great Eastern, designed by

Industries associated with the sea developed throughout the East End, including rope making and shipbuilding. The former location of roperies can still be identified from their long straight, narrow profile in the modern streets, for instance Ropery Street near Mile End. Shipbuilding for the navy is recorded at Ratcliff in 1354, with shipfitting and repair carried out in Blackwall by 1485. On 31 January 1858, the largest ship of that time, the SS Great Eastern, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

, was launched from the yard of Messrs Scott Russell & Co, of Millwall

Millwall is a district on the western and southern side of the Isle of Dogs, in east London, England, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It lies to the immediate south of Canary Wharf and Limehouse, north of Greenwich and Deptford, east ...

. The vessel was too long to fit across the river, and so the ship had to be launched sideways. Due to the technical difficulties of the launch, after this, shipbuilding on the Thames went into a long decline. Ships continued to be built at the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company at Blackwall and Canning Town

Canning Town is a district in the London Borough of Newham, East London. The district is located to the north of the Royal Victoria Dock, and has been described as the "Child of the Victoria Docks" as the timing and nature of its urbanisation w ...

until the yard closed in 1913, shortly after the launch of the Dreadnought Battleship HMS Thunderer (1911)

HMS ''Thunderer'' was the fourth and last dreadnought battleship built for the Royal Navy in the early 1910s. She spent the bulk of her career assigned to the Home and Grand Fleets. Aside from participating in the Battle of Jutland in May 191 ...

.

Heading eastward from the Tower of London lie six and a half mile of former docklands; the most central of the docks - just east of the Tower, is St Katharine Docks, built in 1828 to accommodate luxury goods. This was built by clearing the slums that lay in the area of the former Hospital of St Katharine. They were not successful commercially, as they were unable to accommodate the largest ships, and in 1864, management of the docks was amalgamated with that of the London Docks.

The

Heading eastward from the Tower of London lie six and a half mile of former docklands; the most central of the docks - just east of the Tower, is St Katharine Docks, built in 1828 to accommodate luxury goods. This was built by clearing the slums that lay in the area of the former Hospital of St Katharine. They were not successful commercially, as they were unable to accommodate the largest ships, and in 1864, management of the docks was amalgamated with that of the London Docks.

The London Docks

London Docklands is the riverfront and former docks in London. It is located in inner east and southeast London, in the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Lewisham, Newham, and Greenwich. The docks were formerly part of the Port of Lo ...

were built in 1805, and the waste soil and rubble from the construction was carried by barge to west London, to build up the marshy area of Pimlico. These docks imported tobacco, wine, wool and other goods into guarded warehouses within high walls (some of which still remain). They were able to berth over 300 sailing vessels simultaneously, but by 1971 they closed, no longer able to accommodate modern shipping.

The West India Docks were established in 1803, providing berths for larger ships and a model for future London dock building. Imported produce from the West Indies was unloaded directly into quayside warehouses. Ships were limited to 6000 tons. The old Brunswick Dock, a shipyard at Blackwall became the basis for the East India Company's East India Docks established there in 1806. The Millwall Docks were created in 1868, predominantly for the import of grain and timber. These docks housed the first purpose built granary for the Baltic grain market

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, barley, maize, and rice. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other ...

, a local landmark that remained until it was demolished to improve access for the London City Airport.

The first railway (the " Commercial Railway") to be built, in 1840, was a passenger service based on cable haulage by stationary steam engines that ran the from Minories to Blackwall on a pair of tracks. It required of hemp rope, and "dropped" carriages as it arrived at stations, which were reattached to the cable for the return journey, the train "reassembling" itself at the terminus. The line was converted to standard gauge in 1859, and steam locomotives adopted. The building of London termini at Fenchurch Street (1841), and Bishopsgate

Bishopsgate was one of the eastern gates in London's former defensive wall. The gate gave its name to the Bishopsgate Ward of the City of London. The ward is traditionally divided into ''Bishopsgate Within'', inside the line wall, and ''Bisho ...

(1840) provided access to new suburbs across the River Lea, again resulting in the destruction of housing and increased overcrowding in the slums. After the opening of Liverpool Street station

Liverpool Street station, also known as London Liverpool Street, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in the north-eastern corner of the City of London, in the ward of Bishopsgate Without. It is the t ...

(1874), Bishopsgate railway station became a goods yard, in 1881, to bring imports from Eastern ports. With the introduction of containerisation, the station declined, suffered a fire in 1964 that destroyed the station buildings, and it was finally demolished in 2004 for the extension of the East London Line. In the 19th century, the area north of Bow Road became a major railway centre for the North London Railway, with marshalling yards and a maintenance depot serving both the City and the West India docks. Nearby Bow railway station

Bow was a railway station in Bow, east London, that was opened in 1850 by the East & West India Docks and Birmingham Junction Railway, which was later renamed the North London Railway (NLR). The station was situated between Old Ford and Sout ...

opened in 1850 and was rebuilt in 1870 in a grand style, featuring a concert hall. The line and yards closed in 1944, after severe bomb damage, and never reopened, as goods became less significant, and cheaper facilities were concentrated in Essex.

The River Lea was a constraint to eastward expansion, but the Metropolitan Building Act

The Metropolitan Buildings Office was formed in 1845 to regulate the construction and use of buildings in the metropolitan area of London, England. Surveyors were empowered to enforce building regulations which sought to improve the standard of h ...

of 1844 led to growth over that river into West Ham. The Act restricted the operation of dangerous and noxious industries from in the metropolitan area, the eastern boundary of which was the Lea. Consequently, many of these activities were relocated to the banks of the river. The building of the Royal Docks consisting of the Royal Victoria Dock (1855), able to berth vessels of up to 8000 tons; Royal Albert Dock (1880), up to 12,000 tons; and King George V Dock (1921), up to 30,000 tons, on the estuary marshes helped extend the continuous development of London across the Lea into Essex.[''Royal Docks – a short History'']

Royal Docks Trust (2006) accessed 18 September 2007. The railways gave access to a passenger terminal at Gallions Reach and new suburbs created in West Ham, which quickly became a major manufacturing town, with 30,000 houses built between 1871 and 1901.[

The years 1885-1909 saw a series of transportation milestones achieved in Walthamstow. In 1885, ]John Kemp Starley

John Kemp Starley (24 December 1855 – 29 October 1901) was an English inventor and industrialist who is widely considered the inventor of the modern bicycle, and also originator of the name Rover.

Early life

Born on 24 December 1855 Star ...

designeded the first modern bicycle, while in 1892 Frederick Bremer built the first British motorcar in a workshop in his garden. The London General Omnibus Company

The London General Omnibus Company or LGOC, was the principal bus operator in London between 1855 and 1933. It was also, for a short period between 1909 and 1912, a motor bus manufacturer.

Overview

The London General Omnibus Company was fo ...

built the first mass-produced buses there, the B-type from 1908 onwards and in 1909, A V Roe successfully tested the first all-British aeroplane on Walthamstow Marshes

Walthamstow Marshes, is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Walthamstow in the London Borough of Waltham Forest. It was once an area of lammas land – common land used for growing crops and grazing cattle.

In aviation histor ...

.

Decline and regeneration

The East End has historically suffered from poor housing stock and infrastructure. From the 1950s, the area was a microcosm of the structural and social changes affecting the UK economy.

The closure of docks, cutbacks in railways and loss of industry contributed to a long-term decline, removing many of the traditional sources of low- and semi-skilled jobs.

The docks declined from the mid-20th century, with the last, the Royal Docks, closing in 1980. Various wharves along the river continue to be used but on a much smaller scale. London's main port facilities are now at Tilbury and

The East End has historically suffered from poor housing stock and infrastructure. From the 1950s, the area was a microcosm of the structural and social changes affecting the UK economy.

The closure of docks, cutbacks in railways and loss of industry contributed to a long-term decline, removing many of the traditional sources of low- and semi-skilled jobs.

The docks declined from the mid-20th century, with the last, the Royal Docks, closing in 1980. Various wharves along the river continue to be used but on a much smaller scale. London's main port facilities are now at Tilbury and London Gateway

DP World London Gateway is a port within the wider Port of London, United Kingdom. Opened in November 2013, the site is a fully integrated logistics facility, comprising a semi-automated deep-sea container terminal on the same site as the U ...

(opened in 1886 and 2013 respectively), further downstream, beyond the Greater London boundary in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Gr ...

. These larger modern facilities can accommodate larger vessels and are suitable for the needs of modern container ships

A container ship (also called boxship or spelled containership) is a cargo ship that carries all of its load in truck-size intermodal containers, in a technique called containerization. Container ships are a common means of commercial intermodal f ...

.

There has been extensive regeneration, and the East End has become a desirable place for business,[ partly due to the availability of ]brownfield land

In urban planning, brownfield land is any previously developed land that is not currently in use. It may be potentially contaminated, but this is not required for the area to be considered brownfield. The term is also used to describe land prev ...

. Much of this development has been of little benefit to local communities and has caused a damaging rise in property prices, meaning that much of the area remains among the poorest in Britain.

Housing

The area had one of the highest concentrations of council housing

Public housing in the United Kingdom, also known as council estates, council housing, or social housing, provided the majority of rented accommodation until 2011 when the number of households in private rental housing surpassed the number in so ...

, the legacy of slum clearance and wartime destruction. Many of the 1960s tower blocks have been demolished or renovated, replaced by low-rise housing, often in private ownership, or owned by housing associations.

Transport improvements

By the mid-1980s, the District line (extended to the East End in 1884 and 1902) and Central line (1946) were beyond capacity, and the Docklands Light Railway

The Docklands Light Railway (DLR) is an automated light metro system serving the redeveloped Docklands area of London, England and provides a direct connection between London's two major financial districts, Canary Wharf and the City of Londo ...

(1987) and Jubilee line

The Jubilee line is a London Underground line that runs between in east London and in the suburban north-west, via the Docklands, South Bank and West End. Opened in 1979, it is the newest line on the Underground network, although some secti ...

(1999) were subsequently constructed to improve rail transport in the area.

There was a long-standing plan to provide London with an inner motorway box, the East Cross Route

East Cross Route (ECR) is a dual-carriageway road constructed in east London as part of the uncompleted Ringway 1 as part of the London Ringways plan drawn up the 1960s to create a series of high speed roads circling and radiating out from cen ...

, but only a short section was built. Road links were improved by the completion of the Limehouse Link tunnel

The Limehouse Link tunnel is a long tunnel under Limehouse in East London on the A1203 road. The tunnel links the eastern end of The Highway to Canary Wharf in London Docklands. Built between 1989 and 1993 at a cost of £293,000,000 it ha ...

under Limehouse Basin

Limehouse Basin is a body of water 2 miles east of London Bridge that is also a navigable link between the River Thames and two of London's canals. First dug in 1820 as the eastern terminus of the new Regent's Canal, its wet area was less than ...

in 1993 and the extension of the A12 to connect to the Blackwall Tunnel

The Blackwall Tunnel is a pair of road tunnels underneath the River Thames in east London, England, linking the London Borough of Tower Hamlets with the Royal Borough of Greenwich, and part of the A102 road. The northern portal lies just south o ...

in the 1990s. The extension of the East London line provided further improvements in 2010. From 2021, the Elizabeth Line will create an east–west service across London, with a major interchange at Whitechapel. New river crossings are planned at Beckton, (the Thames Gateway Bridge) and at the proposed Silvertown Link road tunnel, intended to supplement the existing Blackwall Tunnel

The Blackwall Tunnel is a pair of road tunnels underneath the River Thames in east London, England, linking the London Borough of Tower Hamlets with the Royal Borough of Greenwich, and part of the A102 road. The northern portal lies just south o ...

.

City fringe regeneration

The continued strength of the City's financial services sector has seen many large office buildings erected around the City fringe, with indirect benefits accruing to local business. The area around Old Spitalfields Market

Old Spitalfields Market is a covered market in Spitalfields, London. There has been a market on the site for over 350 years. In 1991 it gave its name to New Spitalfields Market in Leyton, where fruit and vegetables are now traded. In 2005, a re ...

has been redeveloped and Brick Lane

Brick Lane ( Bengali: ব্রিক লেন) is a street in the East End of London, in the borough of Tower Hamlets. It runs from Swanfield Street in Bethnal Green in the north, crosses the Bethnal Green Road before reaching the busiest ...

, dubbed ''London's curry capital'', or ''Bangla Town'', has benefited from the City's success.

Art galleries have flourished, including the expanded Whitechapel Gallery and the workshop of artists Gilbert and George

Gilbert Prousch, sometimes referred to as Gilbert Proesch (born 17 September 1943 in San Martin de Tor, Italy), and George Passmore (born 8 January 1942 in Plymouth, United Kingdom), are two artists who work together as the collaborative art d ...

in Spitalfields. The neighbourhood around Hoxton Square

Hoxton Square is a public garden square in the Hoxton area of Shoreditch in the London Borough of Hackney. Laid out in 1683, it is thought to be one of the oldest in London. Since the 1990s it has been at the heart of the Hoxton national (digita ...

has become a centre for modern British art, including the White Cube gallery, with many artists from the Young British Artists movement living and working in the area. This has made the area around Hoxton and Shoreditch fashionable, a busy nightlife has developed, but many former residents now driven out by higher property prices and gentrification.

East London Tech City

East London Tech City (also known as Tech City and Silicon Roundabout) is a technology cluster of high-tech companies located in East London, United Kingdom. Its main area lies broadly between St Luke's and Hackney Road, with an accelerator s ...

, a cluster of technology companies has developed in and around Shoreditch, and the Queen Mary University of London

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL, or informally QM, and previously Queen Mary and Westfield College) is a public university, public research university in Mile End, East London, England. It is a member institution of the federal University of ...

has expanded its existing site at Mile End, and opened specialist medical campuses at the Royal London Hospital and Whitechapel.

Regeneration at Canary Wharf and docklands

The devastating closure of the docks and the loss of the associated industries led to the establishment of the London Docklands Development Corporation

The London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) was a quango agency set up by the UK Government in 1981 to regenerate the depressed Docklands area of east London. During its seventeen-year existence it was responsible for regenerating an ...

, which operated from 1981 to 1998; the body was charged with using deregulation and other levers to stimulate economic regeneration.

As a consequence of this, and of investment in the area's transport infrastructure, there have been many urban renewal projects, most notably Canary Wharf

Canary Wharf is an area of London, England, located near the Isle of Dogs in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Canary Wharf is defined by the Greater London Authority as being part of London's central business district, alongside Central Lon ...

, a huge commercial and housing development on the Isle of Dogs. Another major development is London City Airport, built in 1986, in the former King George V Dock to provide short-haul services to domestic and European destinations. There has been extensive building of luxury apartments, mainly around the former dock areas and alongside the Thames.

The Docklands regeneration has been a success, but being based on service industries, the work does not closely match the skills and needs of the dockland communities.

Regeneration around Stratford

The

The 2012 Summer Olympics

The 2012 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXX Olympiad and also known as London 2012) was an international multi-sport event held from 27 July to 12 August 2012 in London, England, United Kingdom. The first event, the ...

and Paralympics

The Paralympic Games or Paralympics, also known as the ''Games of the Paralympiad'', is a periodic series of international multisport events involving athletes with a range of physical disabilities, including impaired muscle power and impaired ...

were held in the Olympic Park

An Olympic Park is a sports campus for hosting the Olympic Games. Typically it contains the Olympic Stadium and the International Broadcast Centre. It may also contain the Olympic Village or some of the other sports venues, such as the aquatics c ...

, created on former industrial land around the River Lea. The park includes a legacy of new sports facilities, housing, industrial and technical infrastructure intended to further regenerate the area.[ Other developments at Stratford include ]Stratford International station

Stratford International is a National Rail station in Stratford and a separate Docklands Light Railway (DLR) station nearby, located in East Village in London. Despite its name, no international services stop at the station; plans for it to ...

and the Stratford City development. Nearby, the University of East London developed a new campus and many more cultural and educational facilities are being developed in the Olympic Park.

People

Historically, the high death rates experienced in cities has meant they needed inward migration to maintain their level of population. Inward migration has maintained and increased the area's large population, which has in turn become a source of people moving to settle in other areas.

Historically, the high death rates experienced in cities has meant they needed inward migration to maintain their level of population. Inward migration has maintained and increased the area's large population, which has in turn become a source of people moving to settle in other areas.

Inward migration

The influence of the traditional Essex dialect on Cockney

Cockney is an accent and dialect of English, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by working-class and lower middle-class Londoners. The term "Cockney" has traditionally been used to describe a person from the East End, or b ...

speech[Ellis, Alexander J. (1890). English dialects: Their Sounds and Homes. pp. 35, 57, 58.] suggests that a high proportion of early Londoners came from Essex and areas speaking related eastern dialects. Migrants from all over the British Isles have made the East End their home, and migration from overseas has also always been a significant source of new East Enders. As early as 1483, the Portsoken

Portsoken, traditionally referred to with the definite article as the Portsoken, is one of the City of London's 25 ancient wards, which are still used for local elections. Historically an extra-mural Ward, lying east of Aldgate and the City wall ...

is recorded as having more ''aliens'' in its population than any ward in the City of London.

Immigrant communities developed primarily along the river. From the Tudor era until the 20th century, ships' crews were employed on a casual basis. New and replacement crew would be found wherever they were available, local sailors being particularly prized for their knowledge of currents and hazards in foreign ports. Crews were paid at the end of their voyages. Inevitably, permanent communities became established, including small numbers of lascars from the Indian subcontinent and

Immigrant communities developed primarily along the river. From the Tudor era until the 20th century, ships' crews were employed on a casual basis. New and replacement crew would be found wherever they were available, local sailors being particularly prized for their knowledge of currents and hazards in foreign ports. Crews were paid at the end of their voyages. Inevitably, permanent communities became established, including small numbers of lascars from the Indian subcontinent and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

ns from the Guinea Coast. Chinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Austr ...

s in both Shadwell and Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through ...

sprang up in response to Chinese emigration to London, where they opened and operated opium dens, brothels and laundries

Laundry refers to the washing of clothing and other textiles, and, more broadly, their drying and ironing as well. Laundry has been part of history since humans began to wear clothes, so the methods by which different cultures have dealt with t ...

. It was only after the devastation of the Second World War that this predominantly Han Chinese community relocated to Soho.

Weaving was a major industry in areas close to the City but remote from the Thames; the arrival of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

(French Protestant)[Bethnal Green: Settlement and Building to 1836]

, ''A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green'' (1998), pp. 91–5. Date accessed: 17 April 2007 refugees, many of them weavers, alongside large numbers of their English and Irish[''Irish in Britain'' John A. Jackson, pp. 137–9, 150 (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1964)] counterparts contributed to rapid development in Spitalfields and western Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in the East End of London northeast of Charing Cross. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the Green, much of which survives today as Bethnal Green Gardens, beside Cambridge Heath Road. By t ...

in the 17th century.

In 1786, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

was formed by British citizens concerned for the welfare of London's "black poor", many of whom had been evacuated from the thirteen American colonies and were former slaves who had escaped their American masters and fought on the side of the British in the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Others were discharged sailors and freed slaves who had been brought over from British colonies in the West Indies. The committee distributed food, clothing, and medical aid and found work for men, from various locations including the White Raven tavern in Mile End. They also helped the men to go abroad, some to Canada. In October 1786, the Committee funded an expedition of 280 black men, 40 black women and 70 white women (mainly wives and girlfriends) to settle in the Province of Freedom

Cline Town is an area in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The area is named for Emmanuel Kline, a Hausa Liberated African who bought substantial property in the area. The neighborhood is in the vicinity of Granville Town, a settlement established in 1787 ...

in west Africa. The settlers suffered tremendous hardships and many died, but the ''Province of Freedom'' proved to be a major milestone in the establishment of Sierra Leone. From the late 19th century, a large African mariner community was established in Canning Town

Canning Town is a district in the London Borough of Newham, East London. The district is located to the north of the Royal Victoria Dock, and has been described as the "Child of the Victoria Docks" as the timing and nature of its urbanisation w ...

as a result of new shipping links to the Caribbean and West Africa.

In 1655 Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

agreed to allow the resettlement of Jews in England, previously banished by Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal ...

in the 13th century, and the East London became the major centre of Jews in England.[The Jews]

''A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 1: Physique, Archaeology, Domesday, Ecclesiastical Organization, The Jews, Religious Houses, Education of Working Classes to 1870, Private Education from Sixteenth Century'' (1969), pp. 149–51. Date accessed: 17 April 2007 In 1860, the Jews of the East End formed the East Metropolitan Rifle Volunteers (11th Tower Hamlets), a short-lived reserve unit of the British Army.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the massive increase in the number of Jewish émigrés arriving led to over 150 synagogues being built. Today four active synagogues remain in Tower Hamlets: the Congregation of Jacob Synagogue (1903 – Kehillas Ya'akov), the East London Central Synagogue (1922), the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue, established in 1899, was located at 41 Fieldgate Street in the East End of London. This synagogue's official Hebrew name was Sha’ar Ya’akov (Gate of Jacob, שער יעקב), but it became known as the ''Fieldg ...

(1899) and Sandys Row Synagogue (1766).[''Exploring the vanishing Jewish East End'']

London Borough of Tower Hamlets accessed 9 June 2016 Jewish immigration to the East End peaked in the 1890s, leading to agitation which resulted in the Aliens Act 1905

The Aliens Act 1905 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.Moving Here The Act introduced immigration controls and registration for the first time, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for ma ...

, which slowed immigration to the area. In the mid and late 20th century many of the area's Jews migrated to more prosperous areas in the eastern suburbs and north London.

From the late 1950s the local Muslim population began to increase due to further immigration from the Indian subcontinent, particularly from Sylhet in East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

, which became a part of Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

in 1971.[ The migrants settled in areas already established by the Bengali expatriate community, working in the local docks and Jewish tailoring shops set up to use cotton produced in ]British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. During the 1970s, this immigration increased significantly. Today, Bangladeshis form the largest minority population in Tower Hamlets, constituting 32% of the borough's population at the 2011 census; the largest such community in Britain.Pola Uddin, Baroness Uddin

Manzila Pola Khan Uddin, Baroness Uddin, ( bn, মানযিলা পলা উদ্দিন খান; Romanized: ''Manzila Pôla Uddin''; born 17 July 1959) is a British non-affiliated life peer and community activist of Bangladeshi desc ...

of Bethnal Green became the first Bangladeshi-born Briton to enter the House of Lords and the first Muslim peer to swear her oath of allegiance in the name of her own faith.

At the beginning of the 20th century, London was the capital of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, which contained tens of millions of Muslims, but London had no mosque. From 1910 to 1940 various rooms had been hired for Jumu'ah prayers on Fridays and in 1940, three houses were purchased on Commercial Road

Commercial Road is a street in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London. It is long, running from Gardiner's Corner (previously the site of Gardiners department store, and now Aldgate East Underground station), through ...

, becoming the East London Mosque and Islamic Culture Centre the following year. In 1985 the mosque was moved to a new purpose-built building on Whitechapel Road

Whitechapel Road is a major arterial road in Whitechapel, Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London. It is named after a small chapel of ease dedicated to St Mary and connects Whitechapel High Street to the west with Mile End Road to the eas ...

. Currently, the mosque has a capacity of 7,000, with prayer areas for men and women and classroom space for supplementary education.

Immigrants and minorities have occasionally been faced with hostility. In 1517 the Evil May Day

Evil May Day or Ill May Day is the name of a xenophobic riot which took place in 1517 as a protest against foreigners (called "strangers") living in London. Apprentices attacked foreign residents ranging from "Flemish cobblers" to "French royal co ...

riots, in which foreign-owned property was attacked, resulted in the deaths of 135 Flemings in Stepney. The anti-Catholic Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against British ...

of 1780 began with burnings of the houses of Catholics and their chapels in Poplar and Spitalfields.[''London from the Air'']

East London History Society accessed 5 July 2007.

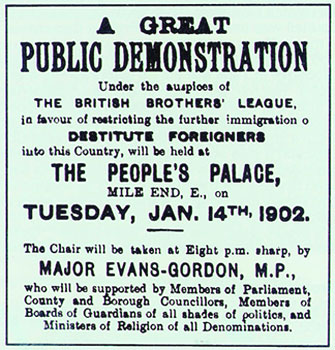

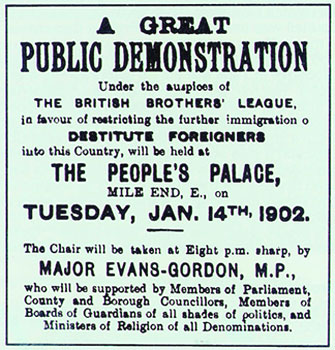

In the 1900 General Election Major Evans-Gordon became the

In the 1900 General Election Major Evans-Gordon became the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization ...

MP for Stepney on a platform of limiting immigration, winning the seat from the Liberal party. In 1901, Captain William Stanley Shaw and he formed the British Brothers' League

The British Brothers' League (BBL) was a British anti-immigration, extraparliamentary, pressure group, the "largest and best organised" of its time. Described as proto-fascist, the group attempted to organise along paramilitary lines.

History

...

which conducted xenophobic agitation against immigrants in the East End, with Jews eventually becoming the main focus. In Parliament in 1902, Evans-Gordon claimed that "not a day passes but English families are ruthlessly turned out to make room for foreign invaders. The rates are burdened with the education of thousands of foreign children." The campaign led to the Aliens Act 1905

The Aliens Act 1905 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.Moving Here The Act introduced immigration controls and registration for the first time, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for ma ...

, which gave the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

powers to regulate and control immigration.

On 4 October 1936, around 3–5,000 uniformed blackshirts from the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

, led by Oswald Mosley and inspired by German and Italian fascism, assembled to begin an anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

march through the East End. Up to 100,000 East Londoners turned out to oppose them, resulting in three-way clashes between the fascists, their anti-fascist opponents and the police. There were clashes at Tower Hill, the Minories, Gardiners Corner (the junction of Whitechapel High Street and Commercial Street) and most famously at Cable Street

Cable Street is a road in the East End of London, England, with several historic landmarks nearby. It was made famous by the Battle of Cable Street in 1936.

Location

Cable Street starts near the edge of London's financial district, the City ...

. These engagements, together known as the Battle of Cable Street

The Battle of Cable Street was a series of clashes that took place at several locations in the inner East End, most notably Cable Street, on Sunday 4 October 1936. It was a clash between the Metropolitan Police, sent to protect a march by me ...

, forced the fascists to abandon their march, and conduct a parade in the West End instead.

In the mid-1970s, so-called "Paki-bashing

Paki is a term typically directed towards people of Pakistani descent mainly in British slang, and as an offensive slur is often used indiscriminately towards people of perceived South Asian descent in general. The slur is used primarily in the ...

" culminated in the murder of 25-year-old clothing worker Altab Ali by three white teenagers in a racially motivated attack. British Bangladeshi groups mobilised for self-defence, 7,000 people marched to Hyde Park in protest, and the community became more politically involved. In 1998, the former churchyard of St Mary's Whitechapel, near where the attack took place, was renamed "Altab Ali Park

Altab Ali Park is a small park on Adler Street, White Church Lane and Whitechapel Road, London E1. Formerly known as St Mary's Park, it is the site of the old 14th-century white church, St Mary Matfelon, from which the area of Whitechapel g ...

" in commemoration. Racially-motivated violence has continued to occasionally occur, and in 1993 the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

won a council seat (which they have since lost). A 1999 bombing in Brick Lane

Brick Lane ( Bengali: ব্রিক লেন) is a street in the East End of London, in the borough of Tower Hamlets. It runs from Swanfield Street in Bethnal Green in the north, crosses the Bethnal Green Road before reaching the busiest ...

was part of a series that targeted ethnic minorities, gays and "multiculturalists".

Outward migration: the Cockney diaspora

As London extended east, East Enders often moved to opportunities in the new suburbs. The late 19th century saw a major movement of people to West Ham[''West Ham: Introduction'', A History of the County of Essex: Volume 6 (1973), pp. 43-50](_blank)

accessed: 23 February 2008 and East Ham[''Becontree hundred: East Ham'', A History of the County of Essex: Volume 6 (1973), pp. 1-8]

18 September 2007 to service the new docks and industries established there.

There was significant work to alleviate overcrowded housing from the start of the 20th century under the London County Council. Between the wars, people moved to new estates built for this purpose, in particular at Becontree and Harold Hill

Harold Hill is a suburban area in the London Borough of Havering, East London. northeast of Charing Cross. It is a district centre in the London Plan. The name refers to King Harold II, who held the manor of Havering-atte-Bower, and who was k ...

, or out of London entirely.

The Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

devastated much of the East End, with its docks, railways and industry forming a continual target for bombing, especially during the Blitz, leading to dispersal of the population to new suburbs and new housing being built in the 1950s.[ Many East Enders went further than the eastern suburbs, leaving London altogether, notably to the ]Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Gr ...

new towns of Basildon

Basildon ( ) is the largest town in the borough of Basildon, within the county of Essex, England. It has a population of 107,123. In 1931 the parish had a population of 1159.

It lies east of Central London, south of the city of Chelmsford and ...

and Harlow

Harlow is a large town and local government district located in the west of Essex, England. Founded as a new town, it is situated on the border with Hertfordshire and London, Harlow occupies a large area of land on the south bank of the upper ...

, the Hertfordshire town of Hemel Hempstead

Hemel Hempstead () is a town in the Dacorum district in Hertfordshire, England, northwest of London, which is part of the Greater London Urban Area. The population at the 2011 census was 97,500.

Developed after the Second World War as a new ...

and elsewhere.

The resulting depopulation accelerated after the Second World War and has only recently begun to reverse, though the Bangladeshi community, now the largest in Tower Hamlets and established East Enders, are beginning to migrate to the eastern suburbs. This reflects improved economic circumstances and in this, the latest group of migrants are following a pattern established for over more than three centuries.

These population figures reflect the area that now forms the London Borough of Tower Hamlets only:

By comparison, in 1801 the population of England and Wales was 9 million; by 1851 it had more than doubled to 18 million, and by the end of the century had reached 40 million.[

]

Culture and community

Cockney identity

Despite a negative image among outsiders, the people of the area take pride in the East End and in their Cockney