Little Boy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Little Boy was a type of

Concern that impurities in reactor-bred plutonium would make predetonation more likely meant that much of the gun-design work was focused on the plutonium gun. To achieve high projectile velocities, the plutonium gun was long with a narrow diameter (suggesting its codename as the Thin Man) which created considerable difficulty in its ballistics dropping from aircraft and fitting it into the

Concern that impurities in reactor-bred plutonium would make predetonation more likely meant that much of the gun-design work was focused on the plutonium gun. To achieve high projectile velocities, the plutonium gun was long with a narrow diameter (suggesting its codename as the Thin Man) which created considerable difficulty in its ballistics dropping from aircraft and fitting it into the  In early 1944, Emilio G. Segrè and his P-5 Group at Los Alamos received the first samples of plutonium produced from a nuclear reactor, the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Clinton Engineer Works in

In early 1944, Emilio G. Segrè and his P-5 Group at Los Alamos received the first samples of plutonium produced from a nuclear reactor, the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Clinton Engineer Works in

The Little Boy was in length, in diameter and weighed approximately . The design used the gun method to explosively force a hollow sub-

The Little Boy was in length, in diameter and weighed approximately . The design used the gun method to explosively force a hollow sub-

The fuzing system was designed to trigger at the most destructive altitude, which calculations suggested was . It employed a three-stage interlock system:

* A timer ensured that the bomb would not explode until at least fifteen seconds after release, one-quarter of the predicted fall time, to ensure the safety of the aircraft. The timer was activated when the electrical pull-out plugs connecting it to the airplane pulled loose as the bomb fell, switching it to its internal 24-volt battery and starting the timer. At the end of the 15 seconds, the bomb would be from the aircraft, and the radar altimeters were powered up and responsibility was passed to the barometric stage.

* The purpose of the barometric stage was to delay activating the radar altimeter firing command circuit until near detonation altitude. A thin metallic membrane enclosing a vacuum chamber (a similar design is still used today in old-fashioned wall barometers) gradually deformed as ambient air pressure increased during descent. The barometric fuze was not considered accurate enough to detonate the bomb at the precise ignition height, because air pressure varies with local conditions. When the bomb reached the design height for this stage (reportedly ), the membrane closed a circuit, activating the radar altimeters. The barometric stage was added because of a worry that external radar signals might detonate the bomb too early.

* Two or more redundant

The fuzing system was designed to trigger at the most destructive altitude, which calculations suggested was . It employed a three-stage interlock system:

* A timer ensured that the bomb would not explode until at least fifteen seconds after release, one-quarter of the predicted fall time, to ensure the safety of the aircraft. The timer was activated when the electrical pull-out plugs connecting it to the airplane pulled loose as the bomb fell, switching it to its internal 24-volt battery and starting the timer. At the end of the 15 seconds, the bomb would be from the aircraft, and the radar altimeters were powered up and responsibility was passed to the barometric stage.

* The purpose of the barometric stage was to delay activating the radar altimeter firing command circuit until near detonation altitude. A thin metallic membrane enclosing a vacuum chamber (a similar design is still used today in old-fashioned wall barometers) gradually deformed as ambient air pressure increased during descent. The barometric fuze was not considered accurate enough to detonate the bomb at the precise ignition height, because air pressure varies with local conditions. When the bomb reached the design height for this stage (reportedly ), the membrane closed a circuit, activating the radar altimeters. The barometric stage was added because of a worry that external radar signals might detonate the bomb too early.

* Two or more redundant

The Little Boy pre-assemblies were designated L-1, L-2, L-3, L-4, L-5, L-6, L-7, and L-11. Of these, L-1, L-2, L-5, and L-6 were expended in test drops. The first drop test was conducted with L-1 on 23 July 1945. It was dropped over the sea near Tinian in order to test the radar altimeter by the B-29 later known as '' Big Stink'', piloted by

The Little Boy pre-assemblies were designated L-1, L-2, L-3, L-4, L-5, L-6, L-7, and L-11. Of these, L-1, L-2, L-5, and L-6 were expended in test drops. The first drop test was conducted with L-1 on 23 July 1945. It was dropped over the sea near Tinian in order to test the radar altimeter by the B-29 later known as '' Big Stink'', piloted by

In Hiroshima, almost everything within of the point directly under the explosion was completely destroyed, except for about 50 heavily reinforced, earthquake-resistant concrete buildings, only the shells of which remained standing. Most were completely gutted, with their windows, doors, sashes, and frames ripped out. The perimeter of severe blast damage approximately followed the contour at .

Later test explosions of nuclear weapons with houses and other test structures nearby confirmed the 5 psi overpressure threshold. Ordinary urban buildings experiencing it were crushed, toppled, or gutted by the force of air pressure. The picture at right shows the effects of a nuclear bomb-generated 5 psi pressure wave on a test structure in Nevada in 1953.

A major effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for fires that were started simultaneously throughout the severe destruction region.

In Hiroshima, almost everything within of the point directly under the explosion was completely destroyed, except for about 50 heavily reinforced, earthquake-resistant concrete buildings, only the shells of which remained standing. Most were completely gutted, with their windows, doors, sashes, and frames ripped out. The perimeter of severe blast damage approximately followed the contour at .

Later test explosions of nuclear weapons with houses and other test structures nearby confirmed the 5 psi overpressure threshold. Ordinary urban buildings experiencing it were crushed, toppled, or gutted by the force of air pressure. The picture at right shows the effects of a nuclear bomb-generated 5 psi pressure wave on a test structure in Nevada in 1953.

A major effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for fires that were started simultaneously throughout the severe destruction region.

here

an

here

* * * * * * This report can also be foun

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

at Carey Sublette's NuclearWeaponArchive.org

Definition and explanation of 'Little Boy'

Simulation of "Little Boy"

an interactive simulation of "Little Boy"

Little Boy 3D Model

information about preparation and dropping the Little Boy bomb

Little boy Nuclear Bomb at Imperial War museum London UK (jpg)

{{Authority control History of the Manhattan Project Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Gun-type nuclear bombs World War II weapons of the United States Code names Nuclear bombs of the United States Cold War aerial bombs of the United States Lockheed Corporation Articles containing video clips World War II aerial bombs of the United States Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1945

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

created by the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the Bo ...

'' Enola Gay'' on 6 August 1945, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare, and the second nuclear explosion in history, after the Trinity nuclear test. It exploded with an energy of approximately and had an explosion radius of approximately which caused widespread death across the city. It was a gun-type fission weapon which used uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

that had been enriched in the isotope uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

to power its explosive reaction.

Little Boy was developed by Lieutenant Commander Francis Birch's group at the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

. It was the successor to a plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

-fueled gun-type fission design, Thin Man, which was abandoned in 1944 after technical difficulties were discovered. Little Boy used a charge of cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in Britain since 1889 to replace black powder as a military firearm propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burni ...

to fire a hollow cylinder (the "bullet") of highly enriched uranium through an artillery gun barrel into a solid cylinder (the "target") of the same material. The design was highly inefficient: the weapon used on Hiroshima contained of uranium, but less than a kilogram underwent nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

. Unlike the implosion design developed for the Trinity test and the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

bomb design that was used against Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

, which required sophisticated coordination of shaped explosive charges, the simpler but inefficient gun-type design was considered almost certain to work, and was never tested prior to its use at Hiroshima.

After the war, numerous components for additional Little Boy bombs were built. By 1950, at least five weapons were completed; all were retired by November 1950.

Naming the bomb

There are two primary accounts of how the first atomic bombs got their names.Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

and Project Alberta physicist Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

stated, many decades after the fact, that he had named the first two atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

designs during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

based on their shapes: Thin Man and Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

. The "Thin Man" was a long, thin device, and its name came from the Dashiell Hammett

Samuel Dashiell Hammett ( ; May 27, 1894 – January 10, 1961) was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the characters he created are Sam Spade ('' The Ma ...

detective novel and series of movies about ''The Thin Man

''The Thin Man'' (1934) is a detective novel by Dashiell Hammett, originally published in a condensed version in the December 1933 issue of '' Redbook''. It appeared in book form the following month. A film series followed, featuring the main ...

''. The "Fat Man" was round and fat so it was named after Kasper Gutman, a rotund character in Hammett's 1930 novel ''The Maltese Falcon'', played by Sydney Greenstreet

Sydney Hughes Greenstreet (December 27, 1879 – January 18, 1954) was a British and American actor. While he did not begin his career in films until the age of 61, he had a run of significant motion pictures in a Hollywood career lasting t ...

in the 1941 film version. Little Boy was named by others as an allusion to Thin Man since it was based on its design. It was also sometimes referred to as the "Mark I" nuclear bomb design, with "Mark II" referring to the abandoned Thin Man, and "Mark III" to the "Fat Man."

In September 1945, another Project Alberta physicist, Norman F. Ramsey, stated in his brief "History of Project A," that the early bomb ballistic test shapes designs were referred to as "Thin Man" and "Fat Man" by (unspecified) "Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

representatives" for "security reasons," so that their communications over telephones sounded "as if they were modifying a plane to carry Roosevelt (the Thin Man) and Churchill (the Fat Man)," as opposed to modifying the B-29

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined Propeller (aeronautics), propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to ...

s to carry the two atomic bomb shapes as part of Project Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces' participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project which enabled a B-29 Superfortress bomber to drop ...

in late 1943.

Another explanation of the names, from a classified United States Air Force history of Project Silverplate from the 1950s, implies a possible reconciliation of the two versions: that the terms "Thin Man" and "Fat Man" were first developed by someone at or from Los Alamos (i.e., Serber), but were consciously adopted by the officers in Silverplate when they were adopting their own codenames for their own project (including "Silverplate"). As Silverplate involved modifying B-29s for a secret purpose, deliberately using codenames that would align with modifying vehicles for Roosevelt and Churchill would serve their needs well.

Development

Early gun-type design work

Because of its perceived simplicity, the gun-type nuclear weapon design was the first approach pursued by the scientists working on bomb design during theManhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

. In 1942, it was not yet known which of the two fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy i ...

s pathways being simultaneously pursued—uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

or plutonium-239

Plutonium-239 ( or Pu-239) is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main iso ...

—would be successful, or if there were significant differences between the two fuels

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chemical energy but ...

that would impact the design work. Coordination with British scientists in May 1942 convinced the American scientists, led by J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World ...

, that the atomic bomb would not be difficult to design and that the difficulty would lie only in the production of fuel. Calculations in mid-1942 by theoretical physicists working on the project reinforced the idea that an ordinary artillery gun barrel would be able to impart sufficient velocity to the fissile material projectile.

Several different weapon designs, including autocatalytic assembly, a nascent version of implosion, and alternative gun designs (e.g., using high explosives as a propellent, or creating a "double gun" with two projectiles) were pursued in the early years of the project, while the facilities to manufacture fissile material were being constructed. The belief that the gun design would be an easy engineering task once fuel was available led to a sense of optimism at Los Alamos, although Oppenheimer established a small research group to study implosion as a fallback in early 1943. A full ordnance program for gun-design development was established by March 1943, with expertise provided by E.L. Rose, an experienced gun designer and engineer. Work was begun to study the properties of barrels, internal and external ballistics

Ballistics is the field of mechanics concerned with the launching, flight behaviour and impact effects of projectiles, especially weapon munitions such as bullets, unguided bombs, rockets and the like; the science or art of designing and acceler ...

, and tampers of gun weapons. Oppenheimer led aspects of the effort, telling Rose that "at the present time ay 1945our estimates are so ill founded that I think it better for me to take responsibility for putting them forward." He soon delegated the work to Naval Captain William Sterling Parsons, who, along with Ed McMillan, Charles Critchfield, and Joseph Hirschfelder would be responsible for rendering the theory into practice.

Concern that impurities in reactor-bred plutonium would make predetonation more likely meant that much of the gun-design work was focused on the plutonium gun. To achieve high projectile velocities, the plutonium gun was long with a narrow diameter (suggesting its codename as the Thin Man) which created considerable difficulty in its ballistics dropping from aircraft and fitting it into the

Concern that impurities in reactor-bred plutonium would make predetonation more likely meant that much of the gun-design work was focused on the plutonium gun. To achieve high projectile velocities, the plutonium gun was long with a narrow diameter (suggesting its codename as the Thin Man) which created considerable difficulty in its ballistics dropping from aircraft and fitting it into the bomb bay

The bomb bay or weapons bay on some military aircraft is a compartment to carry bombs, usually in the aircraft's fuselage, with "bomb bay doors" which open at the bottom. The bomb bay doors are opened and the bombs are dropped when over the ...

of a B-29.

In early 1944, Emilio G. Segrè and his P-5 Group at Los Alamos received the first samples of plutonium produced from a nuclear reactor, the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Clinton Engineer Works in

In early 1944, Emilio G. Segrè and his P-5 Group at Los Alamos received the first samples of plutonium produced from a nuclear reactor, the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's po ...

. Analyzing it, they discovered that the presence of the isotope plutonium-240

Plutonium-240 ( or Pu-240) is an isotope of plutonium formed when plutonium-239 captures a neutron. The detection of its spontaneous fission led to its discovery in 1944 at Los Alamos and had important consequences for the Manhattan Project.

...

(Pu-240) raised the rate of spontaneous fission

Spontaneous fission (SF) is a form of radioactive decay in which a heavy atomic nucleus splits into two or more lighter nuclei. In contrast to induced fission, there is no inciting particle to trigger the decay; it is a purely probabilistic proc ...

of the plutonium to an unacceptable amount. Previous analyses of plutonium had been made from samples created by cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

s and did not have as much of the contaminating isotope. If reactor-bred plutonium was used in a gun-type design, they concluded, it would predetonate, causing the weapon to destroy itself before achieving the conditions for a large-scale explosion.

From Thin Man to Little Boy

As a consequence of the discovery of the Pu-240 contamination problem, in July 1944 almost all research at Los Alamos was redirected to the implosion-type plutonium weapon, and the laboratory was entirely reorganized around the implosion problem. Work on the gun-type weapon continued under Person's Ordnance (O) Division, for use exclusively with highly enriched uranium as a fuel. All the design, development, and technical work at Los Alamos was consolidated under Lieutenant Commander Francis Birch's group. In contrast to the plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapon and the plutonium gun-type fission weapon, the uranium gun-type weapon was much simpler to design. As a high-velocity gun was no longer required, the overall length of the gun barrel could be dramatically decreased, and this allowed the weapon to fit into a B-29 bomb bay without difficulty. Though not an optimal use of fissile material compared to the implosion design, it was seen as a nearly guaranteed weapon. The design specifications were completed in February 1945, and contracts were let to build the components. Three different plants were used so that no one would have a copy of the complete design. The gun and breech were made by the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, D.C.; the target case and some other components by the Naval Ordnance Plant in Center Line, Michigan; and the tail fairing and mounting brackets by the Expert Tool and Die Company inDetroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

. The bomb, except for the uranium payload, was ready at the beginning of May 1945. Manhattan District Engineer Kenneth Nichols expected on 1 May 1945 to have enriched uranium "for one weapon before August 1 and a second one sometime in December", assuming the second weapon would be a gun type; designing an implosion bomb for enriched uranium was considered, and this would increase the production rate. The enriched uranium projectile was completed on 15 June, and the target was completed on 24 July. The target and bomb pre-assemblies (partly assembled bombs without the fissile components) left Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, California, on 16 July aboard the heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

, arriving on 26 July. The target inserts followed by air on 30 July.

Although all of its components had been individually tested, no full test of a gun-type nuclear weapon occurred before the Little Boy was dropped over Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

. The only test explosion of a nuclear weapon concept had been of an implosion-type device employing plutonium as its fissile material, which took place on 16 July 1945 at the Trinity nuclear test. There were several reasons for not testing a Little Boy type of device. Primarily, there was the issue of fissile material availability. K-25 at Clinton Engineer Works was designed to produce around 30 kilograms of enriched uranium per month, and the Little Boy design used over 60 kilograms per bomb. So testing the weapon would incur a considerable delay in use of the weapon. (By comparison, B Reactor

The B Reactor at the Hanford Site, near Richland, Washington, was the first large-scale nuclear reactor ever built, at 250 MW. It achieved criticality on September 26, 1944. The project was a key part of the Manhattan Project, the United States ...

at the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It has also been known as SiteW and the Hanford Nuclear R ...

was designed to produce around 20 kilograms of plutonium per month, and each Fat Man bomb used around 6 kilograms of material.) Because of the simplicity of the gun-type design, laboratory testing could establish that its parts worked correctly on their own: for example, dummy projectiles could be shot down the gun barrel to make sure they were "seated" correctly onto a dummy target. Absence of a full-scale test in the implosion-type design made it much more difficult to establish whether the necessary simultaneity of compression had been achieved. While there was at least one prominent scientist (Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American accelerator physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation for ...

) who advocated for a full-scale test, by early 1945 Little Boy was regarded as nearly a sure thing and was expected to have a higher yield than the first-generation implosion bombs.

Though Little Boy incorporated various safety mechanisms, an accidental detonation of a fully-assembled weapon was very possible. Should the bomber carrying the device crash, the hollow "bullet" could be driven into the "target" cylinder, possibly detonating the bomb from gravity alone (though tests suggested this was unlikely), but easily creating a critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

that would release dangerous amounts of radiation. A crash of the B-29 and subsequent fire could trigger the explosives, causing the weapon to detonate. If immersed in water, the uranium components were subject to a neutron moderator

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, ideally without capturing any, leaving them as thermal neutrons with only minimal (thermal) kinetic energy. These thermal neutrons are immensely ...

effect, which would not cause an explosion but would release radioactive contamination

Radioactive contamination, also called radiological pollution, is the deposition of, or presence of Radioactive decay, radioactive substances on surfaces or within solids, liquids, or gases (including the human body), where their presence is uni ...

. For this reason, pilots were advised to crash on land rather than at sea. Ultimately, Parsons opted to keep the explosives out of the Little Boy bomb until after the B-29 had taken off, to avoid the risk of a crash that could destroy or damage the military base from which the weapon was launched.

Design

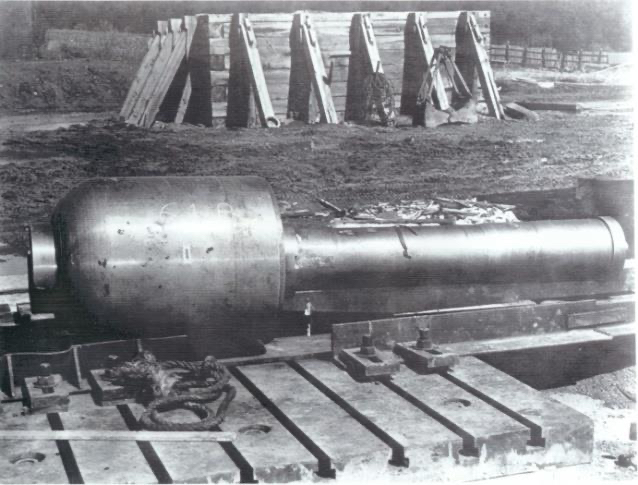

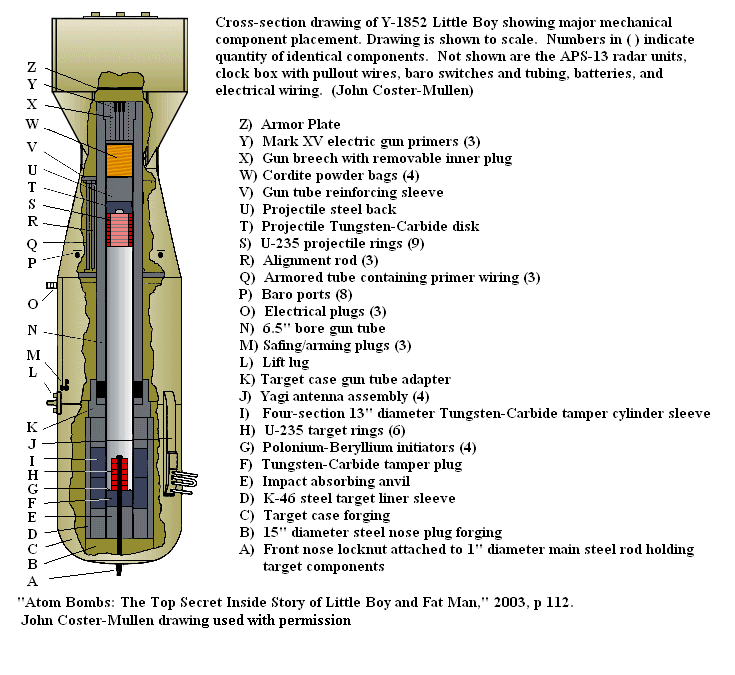

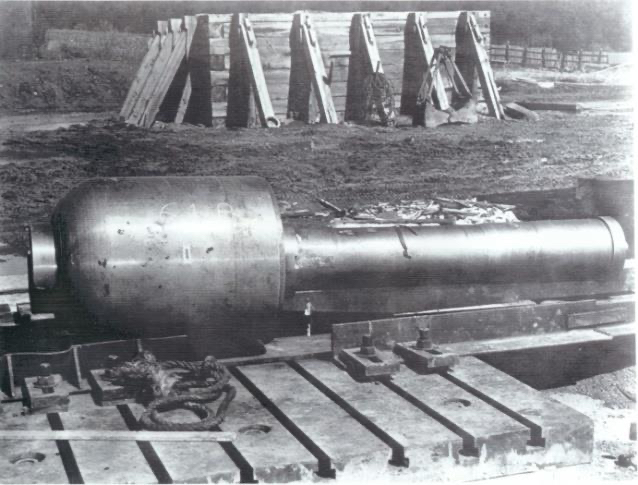

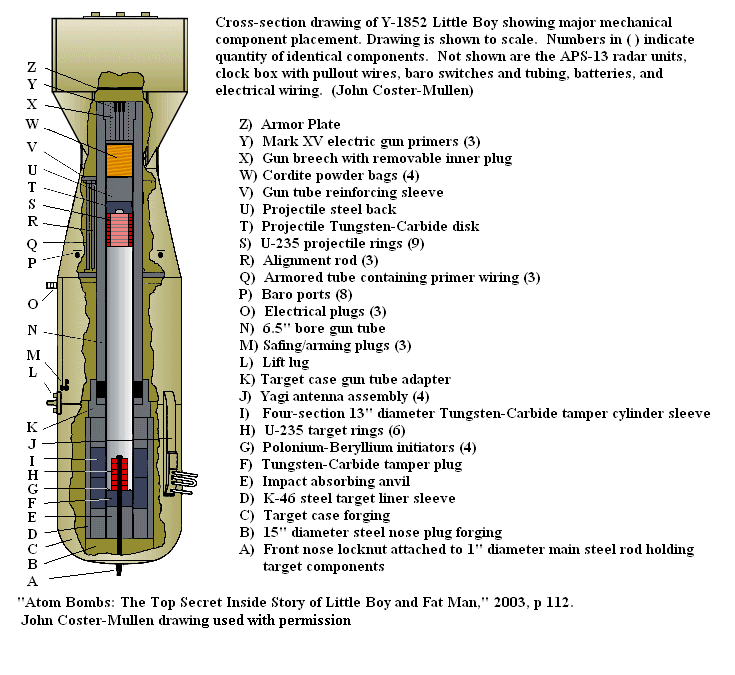

The Little Boy was in length, in diameter and weighed approximately . The design used the gun method to explosively force a hollow sub-

The Little Boy was in length, in diameter and weighed approximately . The design used the gun method to explosively force a hollow sub-critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

of enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

and a solid target cylinder together into a super-critical mass, initiating a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

. This was accomplished by shooting one piece of the uranium onto the other by means of four cylindrical silk bags of cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in Britain since 1889 to replace black powder as a military firearm propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burni ...

powder. This was a widely used smokeless propellant consisting of a mixture of 65 percent nitrocellulose

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

, 30 percent nitroglycerine

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

, 3 percent petroleum jelly

Petroleum jelly, petrolatum (), white petrolatum, soft paraffin, or multi-hydrocarbon, CAS number 8009-03-8, is a semi-solid mixture of hydrocarbons (with carbon numbers mainly higher than 25), originally promoted as a topical ointment for i ...

, and 2 percent carbamite that was extruded into tubular granules. This gave it a high surface area and a rapid burning area, and could attain pressures of up to . Cordite for the wartime Little Boy was sourced from Canada; propellant for post-war Little Boys was obtained from the Picatinny Arsenal

The Picatinny Arsenal ( or ) is an American military research and manufacturing facility located on of land in Jefferson and Rockaway Townships in Morris County, New Jersey, United States, encompassing Picatinny Lake and Lake Denmark. The ...

. The bomb contained of enriched uranium. Most was enriched to 89% but some was only 50% uranium-235, for an average enrichment of 80%. Less than a kilogram of uranium underwent nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

, and of this mass only represents the mass-energy equivalence of the 15 kiloton yield. This was transformed into several forms of energy, mostly kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the form of energy that it possesses due to its motion.

In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass ''m'' traveling at a speed ''v'' is \fracmv^2.Resnick, Rober ...

, but also heat and radiation.

Assembly details

Inside the weapon, the uranium-235 material was divided into two parts, following the gun principle: the "projectile" and the "target". The projectile was a hollow cylinder with 60% of the total mass (). It consisted of a stack of nine uranium rings, each in diameter with a bore in the center, and a total length of , pressed together into the front end of a thin-walled projectile long. Filling in the remainder of the space behind these rings in the projectile was atungsten carbide

Tungsten carbide (chemical formula: ) is a carbide containing equal parts of tungsten and carbon atoms. In its most basic form, tungsten carbide is a fine gray powder, but it can be pressed and formed into shapes through sintering for use in in ...

disc with a steel back. At ignition, the projectile slug was pushed along the , smooth-bore gun barrel. The slug "insert" was a 4-inch cylinder, 7 inches in length with a axial hole. The slug comprised 40% of the total fissile mass (). The insert was a stack of six washer-like uranium discs somewhat thicker than the projectile rings that were slid over a 1-inch rod. This rod then extended forward through the tungsten carbide plug, impact-absorbing anvil, and nose plug backstop, eventually protruding out of the front of the bomb casing. This entire target assembly was secured at both ends with locknuts.

When the hollow-front projectile reached the target and slid over the target insert, the assembled super-critical mass of uranium would be completely surrounded by a tamper and neutron reflector of tungsten carbide and steel, both materials having a combined mass of . Neutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

s inside the assembly were activated by the impact of the projectile into the target.

Counter-intuitive design

The material was split almost in half, with at one end a group of rings of highly enriched uranium with 40% of the supercritical mass, and at the other end another group of slightly larger rings with 60% of the supercritical mass, which was fired onto the smaller group, with four polonium-berylliumneutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

s to make the supercritical mass explode.

A hole in the center of the larger piece dispersed the mass and increased the surface area, allowing more fission neutrons to escape, thus preventing a premature chain reaction. But, for this larger, hollow piece to have minimal contact with the tungsten carbide tamper, it must be the projectile, since only the projectile's back end was in contact with the tamper prior to detonation. The rest of the tungsten carbide tamper surrounded the sub-critical mass target cylinder (called the "insert" by the designers) with air space between it and the insert. This arrangement packs the maximum amount of fissile material into a gun-assembly design.

For the first fifty years after 1945, every published description and drawing of the Little Boy mechanism assumed that a small, solid projectile was fired into the center of a larger, stationary target. However, critical mass considerations dictated that in Little Boy the more extensive, hollow piece would be the projectile. Hollow cylinders have higher critical masses than solid pieces of fissile material, because any neutrons encountered by or generated by the material are more likely to get scattered in the air than to continue a chain reaction. The larger piece would also avoid the effects of neutron reflection from the tungsten carbide tamper until it was fully joined with the rest of the fuel. Once joined and with its neutrons reflected, the assembled fissile core would comprise more than two critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

es of uranium-235. In 2004, John Coster-Mullen, a truck driver and model maker from Illinois who had studied every photograph and document on the Hiroshima bomb to make an accurate model, corrected earlier published accounts.

Fuze system

radar altimeter

A radar altimeter (RA), also called a radio altimeter (RALT), electronic altimeter, reflection altimeter, or low-range radio altimeter (LRRA), measures altitude above the terrain presently beneath an aircraft or spacecraft by timing how long it t ...

s were used to reliably detect final altitude. When the altimeters sensed the correct height, the firing switch closed, igniting the three BuOrd Mk15, Mod 1 Navy gun primers in the breech plug, which set off the charge consisting of four silk powder bags each containing of WM slotted-tube cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in Britain since 1889 to replace black powder as a military firearm propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burni ...

. This launched the uranium projectile towards the opposite end of the gun barrel at an eventual muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

of . Approximately 10 milliseconds later the chain reaction occurred, lasting less than 1 microsecond. The radar altimeters used were modified U.S. Army Air Corps APS-13 tail warning radars, nicknamed "Archie", normally used to warn a fighter pilot of another plane approaching from behind.

Rehearsals

The Little Boy pre-assemblies were designated L-1, L-2, L-3, L-4, L-5, L-6, L-7, and L-11. Of these, L-1, L-2, L-5, and L-6 were expended in test drops. The first drop test was conducted with L-1 on 23 July 1945. It was dropped over the sea near Tinian in order to test the radar altimeter by the B-29 later known as '' Big Stink'', piloted by

The Little Boy pre-assemblies were designated L-1, L-2, L-3, L-4, L-5, L-6, L-7, and L-11. Of these, L-1, L-2, L-5, and L-6 were expended in test drops. The first drop test was conducted with L-1 on 23 July 1945. It was dropped over the sea near Tinian in order to test the radar altimeter by the B-29 later known as '' Big Stink'', piloted by Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Paul W. Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the ''Enola Gay'' (named after his mothe ...

, the commander of the 509th Composite Group. Two more drop tests over the sea were made on 24 and 25 July, using the L-2 and L-5 units in order to test all components. Tibbets was the pilot for both missions, but this time the bomber used was the one subsequently known as '' Jabit''. L-6 was used as a dress rehearsal on 29 July. The B-29 '' Next Objective'', piloted by Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Charles W. Sweeney, flew to Iwo Jima

is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands, which lie south of the Bonin Islands and together with them make up the Ogasawara Subprefecture, Ogasawara Archipelago. Together with the Izu Islands, they make up Japan's Nanpō Islands. Although sout ...

, where emergency procedures for loading the bomb onto a standby aircraft were practiced. This rehearsal was repeated on 31 July, but this time L-6 was reloaded onto a different B-29, '' Enola Gay'', piloted by Tibbets, and the bomb was test dropped near Tinian. L-11 was the assembly used for the Hiroshima bomb, and was fully assembled with its nuclear fuel by 31 July.

Bombing of Hiroshima

Parsons, the ''Enola Gay''s weaponeer, was concerned about the possibility of an accidental detonation if the plane crashed on takeoff, so he decided not to load the four cordite powder bags into the gun breech until the aircraft was in flight. After takeoff, Parsons and his assistant, Second Lieutenant Morris R. Jeppson, made their way into the bomb bay along the narrow catwalk on the port side. Jeppson held a flashlight while Parsons disconnected the primer wires, removed the breech plug, inserted the powder bags, replaced the breech plug, and reconnected the wires. Before climbing to altitude on approach to the target, Jeppson switched the three safety plugs between the electrical connectors of the internal battery and the firing mechanism from green to red. The bomb was then fully armed. Jeppson monitored the bomb's circuits. The bomb was dropped at approximately 08:15 (JST) on 6 August 1945. After falling for 44.4 seconds, the time and barometric triggers started the firing mechanism. The detonation happened at an altitude of . It was less powerful than theFat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

, which was dropped on Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

, but the damage and the number of victims at Hiroshima were much higher, as Hiroshima was on flat terrain, while the hypocenter

A hypocenter or hypocentre (), also called ground zero or surface zero, is the point on the Earth's surface directly below a nuclear explosion, meteor air burst, or other mid-air explosion. In seismology, the hypocenter of an earthquake is its ...

of Nagasaki lay in a small valley. According to figures published in 1945, 66,000 people were killed as a direct result of the Hiroshima blast, and 69,000 were injured to varying degrees. Later estimates put the deaths as high as 140,000 people. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) was a written report created by a board of experts assembled to produce an impartial assessment of the effects of the Anglo-American strategic bombing of Nazi Germany during the European theatre ...

estimated that out of 24,158 Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

soldiers in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing, 6,789 were killed or missing as a result of the bombing.

The exact measurement of the explosive yield of the bomb was problematic since the weapon had never been tested. President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

officially announced that the yield was . This was based on Parsons's visual assessment that the blast was greater than what he had seen at the Trinity nuclear test. Since that had been estimated at , speech writers rounded up to 20 kilotons. Further discussion was then suppressed, for fear of lessening the impact of the bomb on the Japanese. Data had been collected by Luis Alvarez, Harold Agnew, and Lawrence H. Johnston on the instrument plane, '' The Great Artiste'', but this was not used to calculate the yield at the time. More rigorous estimates of the bomb yield and conventional bomb equivalent were made when more data was acquired following the end of the war. A 1985 study estimated the bomb's yield was around .

Physical effects

After being selected in April 1945, Hiroshima was spared conventional bombing to serve as a pristine target, where the effects of a nuclear bomb on an undamaged city could be observed. While damage could be studied later, the energy yield of the untested Little Boy design could be determined only at the moment of detonation, using instruments dropped by parachute from a plane flying in formation with the one that dropped the bomb. Radio-transmitted data from these instruments indicated a yield of about 15 kilotons. Comparing this yield to the observed damage produced a rule of thumb called the lethal area rule. Approximately all the people inside the area where the shock wave carried such an overpressure or greater would be killed. At Hiroshima, that area was in diameter. The damage came from three main effects: blast, fire, and radiation.Blast

The blast from a nuclear bomb is the result ofX-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

-heated air (the fireball) sending a shock wave or pressure wave in all directions, initially at a velocity greater than the speed of sound, analogous to thunder generated by lightning. Knowledge about urban blast destruction is based largely on studies of Little Boy at Hiroshima. Nagasaki buildings suffered similar damage at similar distances, but the Nagasaki bomb detonated from the city center over hilly terrain that was partially bare of buildings.

In Hiroshima, almost everything within of the point directly under the explosion was completely destroyed, except for about 50 heavily reinforced, earthquake-resistant concrete buildings, only the shells of which remained standing. Most were completely gutted, with their windows, doors, sashes, and frames ripped out. The perimeter of severe blast damage approximately followed the contour at .

Later test explosions of nuclear weapons with houses and other test structures nearby confirmed the 5 psi overpressure threshold. Ordinary urban buildings experiencing it were crushed, toppled, or gutted by the force of air pressure. The picture at right shows the effects of a nuclear bomb-generated 5 psi pressure wave on a test structure in Nevada in 1953.

A major effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for fires that were started simultaneously throughout the severe destruction region.

In Hiroshima, almost everything within of the point directly under the explosion was completely destroyed, except for about 50 heavily reinforced, earthquake-resistant concrete buildings, only the shells of which remained standing. Most were completely gutted, with their windows, doors, sashes, and frames ripped out. The perimeter of severe blast damage approximately followed the contour at .

Later test explosions of nuclear weapons with houses and other test structures nearby confirmed the 5 psi overpressure threshold. Ordinary urban buildings experiencing it were crushed, toppled, or gutted by the force of air pressure. The picture at right shows the effects of a nuclear bomb-generated 5 psi pressure wave on a test structure in Nevada in 1953.

A major effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for fires that were started simultaneously throughout the severe destruction region.

Fire

The first effect of the explosion was blinding light, accompanied by radiant heat from the fireball. The Hiroshima fireball was in diameter, with a surface temperature of , about the same temperature as at the surface of the sun. Near ground zero, everything flammable burst into flame. One famous, anonymous Hiroshima victim, sitting on stone steps from the hypocenter, left a permanent shadow, having absorbed the fireball heat that permanently bleached the surrounding stone. Simultaneous fires were started throughout the blast-damaged area by fireball heat and by overturned stoves and furnaces, electrical shorts, etc. Twenty minutes after the detonation, these fires had merged into afirestorm

A firestorm is a conflagration which attains such intensity that it creates and sustains its own wind system. It is most commonly a natural phenomenon, created during some of the largest bushfires and wildfires. Although the term has been used ...

, pulling in surface air from all directions to feed an inferno which consumed everything flammable.

The Hiroshima firestorm was roughly in diameter, corresponding closely to the severe blast-damage zone. (See the USSBS map, right.) Blast-damaged buildings provided fuel for the fire. Structural lumber and furniture were splintered and scattered about. Debris-choked roads obstructed firefighters. Broken gas pipes fueled the fire, and broken water pipes rendered hydrants useless. At Nagasaki, the fires failed to merge into a single firestorm, and the fire-damaged area was only one-quarter as great as at Hiroshima, due in part to a southwest wind that pushed the fires away from the city.

As the map shows, the Hiroshima firestorm jumped natural firebreaks (river channels), as well as prepared firebreaks. The spread of fire stopped only when it reached the edge of the blast-damaged area, encountering less available fuel. The Manhattan Project report on Hiroshima estimated that 60% of immediate deaths were caused by fire, but with the caveat that "many persons near the center of explosion suffered fatal injuries from more than one of the bomb effects."

Radiation

Local fallout is dust and ash from a bomb crater, contaminated with radioactive fission products. It falls to earth downwind of the crater and can produce, with radiation alone, a lethal area much larger than that from blast and fire. With anair burst

An air burst or airburst is the detonation of an explosive device such as an anti-personnel artillery shell or a nuclear weapon in the air instead of on contact with the ground or target. The principal military advantage of an air burst over ...

, the fission products rise into the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second-lowest layer of the atmosphere of Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is composed of stratified temperature zones, with the warmer layers of air located higher ...

, where they dissipate and become part of the global environment. Because Little Boy was an air burst above the ground, there was no bomb crater and no local radioactive fallout.

However, a burst of intense neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

and gamma radiation

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from high energy interactions like the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei or astronomical events like solar flares. It consists o ...

came directly from the fission of the uranium. Its lethal radius was approximately , covering about half of the firestorm area. An estimated 30% of immediate fatalities were people who received lethal doses of this direct radiation, but died in the firestorm before their radiation injuries would have become apparent. Over 6,000 people survived the blast and fire, but died of radiation injuries. Among injured survivors, 30% had radiation injuries from which they recovered, but with a lifelong increase in cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

risk. To date, no radiation-related evidence of heritable diseases has been observed among the survivors' children.

After the surrender of Japan was finalized, Manhattan Project scientists began to immediately survey the city of Hiroshima to better understand the damage, and to communicate with Japanese physicians about radiation effects in particular. The collaboration became the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) ( Japanese:原爆傷害調査委員会, ''Genbakushōgaichōsaiinkai'') was a commission established in 1946 in accordance with a presidential directive from Harry S. Truman to the National Academy of S ...

in 1946, a joint U.S.–Japanese project to track radiation injuries among survivors. In 1975 its work was superseded by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation.

In 1962, scientists at Los Alamos created a mockup of Little Boy known as "Project Ichiban" in order to answer some of the unanswered questions about the exact radiation output of the bomb, which would be useful for setting benchmarks for interpreting the relationship between radiation exposure and later health outcomes. But it failed to clear up all the issues. In 1982, Los Alamos created a replica Little Boy from the original drawings and specifications. This was then tested with enriched uranium but in a safe configuration that would not cause a nuclear explosion. A hydraulic lift was used to move the projectile, and experiments were run to assess neutron emission.

Conventional weapon equivalent

After hostilities ended, a survey team from the Manhattan Project that included William Penney, Robert Serber, and George T. Reynolds was sent to Hiroshima to evaluate the effects of the blast. From evaluating the effects on objects and structures, Penney concluded that the yield was 12 ± 1 kilotons. Later calculations based on charring pointed to a yield of 13 to 14 kilotons. In 1953,Frederick Reines

Frederick Reines ( ; March 16, 1918 – August 26, 1998) was an American physicist. He was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics for his co-detection of the neutrino with Clyde Cowan in the neutrino experiment. He may be the only scientist in ...

calculated the yield as . Based on the Project Ichiban data, and the pressure-wave data from ''The Great Artiste'', the yield was estimated in the 1960s at 16.6 ± 0.3 kilotons. A review conducted by a scientist at Los Alamos in 1985 concluded, on the basis of existing blast, thermal, and radiological data, and then-current models of weapons effects, that the best estimate of the yield was with an uncertainty of 20% (±3 kt). By comparison, the best value for the Nagasaki bomb was evaluated as with an uncertainty of 10% (±2 kt), the difference in uncertainty owing to having better data on the latter.

To put these numerical differences into context, it is necessary to know that the acute effects of nuclear detonations, especially the blast and thermal effects, do not scale linearly, but generally as a cubic root. Specifically, the distance of these effects scale as a function of the yield raised to an exponential power of . So the range of the overpressure damage expected from a detonated 12 kiloton weapon with a height of burst at would be expected to be , whereas a 20 kiloton weapon would have the same range extend to , a difference of only . The areas affected for each would be and , respectively. As such, the practical differences in effects at these yield ranges are smaller than may at first appear, if one assumes that there is a linear relationship between yield and damage.These calculated numbers come from the NUKEMAP website, which uses the data and calculations from .

Although Little Boy exploded with the energy equivalent of around 15 kilotons of TNT, in 1946 the Strategic Bombing Survey estimated that the same blast and fire effect could have been caused by 2.1 kilotons of conventional bombs distributed evenly over the same target area: "220 B-29s carrying 1.2 kilotons of incendiary bombs, 400 tons of high-explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

bombs, and 500 tons of anti-personnel

An anti-personnel weapon is a weapon primarily used to maim or kill infantry and other personnel not behind armor, as opposed to attacking structures or vehicles, or hunting game. The development of defensive fortification and combat vehicles gav ...

fragmentation bombs." Since the target was spread across a two-dimensional plane, the vertical component of a single spherical nuclear explosion was largely wasted. A cluster bomb

A cluster munition is a form of air-dropped or ground-launched explosive weapon that releases or ejects smaller submunitions. Commonly, this is a cluster bomb that ejects explosive bomblets that are designed to kill personnel and destroy vehi ...

pattern of smaller explosions would have been a more energy-efficient match to the target.

Post-WWII

When the war ended, it was not expected that the inefficient Little Boy design would ever again be required, and many plans and diagrams were destroyed. However, by mid-1946 the Hanford Site reactors were suffering badly from the Wigner effect. Faced with the prospect of no more plutonium for new cores and no morepolonium

Polonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Po and atomic number 84. A rare and highly radioactive metal (although sometimes classified as a metalloid) with no stable isotopes, polonium is a chalcogen and chemically similar to selenium and tel ...

for the initiators for the cores that had already been produced, the Director of the Manhattan Project, Major General Leslie R. Groves, ordered that some Little Boys be prepared as an interim measure until a solution could be found. No Little Boy assemblies were available, and no comprehensive set of diagrams of the Little Boy could be found, although there were drawings of the various components, and stocks of spare parts.

At Sandia Base

Sandia Base was the principal nuclear weapons installation of the United States Department of Defense from 1946 to 1971. It was located on the southeastern edge of Albuquerque, New Mexico. For 25 years, the top-secret Sandia Base and its subsidiar ...

, three Army officers, Captains Albert Bethel, Richard Meyer, and Bobbie Griffin attempted to re-create the Little Boy. They were supervised by Harlow W. Russ, an expert on Little Boy who served with Project Alberta on Tinian, and was now leader of the Z-11 Group of the Los Alamos Laboratory's Z Division at Sandia. Gradually, they managed to locate the correct drawings and parts, and figured out how they went together. Eventually, they built six Little Boy assemblies. Although the casings, barrels, and components were tested, no enriched uranium was supplied for the bombs. By early 1947, the problem caused by the Wigner effect was on its way to solution, and the three officers were reassigned.

The Navy Bureau of Ordnance

The Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) was a United States Navy organization, which was responsible for the procurement, storage, and deployment of all naval weapons, between the years 1862 and 1959.

History

The Bureau of Ordnance was established as part ...

began in 1947 to produce 25 "revised" Little Boy mechanical assemblies for use by the nuclear-capable Lockheed P2V Neptune aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

aircraft (which could be launched from, but not land on, the ''Midway''-class aircraft carriers). Components were produced by the Naval Ordnance Plants in Pocatello, Idaho

Pocatello () is the county seat of and the largest city in Bannock County, Idaho, Bannock County, with a small portion on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in neighboring Power County, Idaho, Power County, containing the city's airport. It is t ...

, and Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

. Enough fissionable material was available by 1948 to build ten projectiles and targets, although there were only enough initiators for six. However, no actual fissionable components were produced by the end of 1948, and only two outer casings were available. By the end of 1950, only five complete Little Boy assemblies had been built. All were retired by November 1950.

The Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

displayed a Little Boy (complete, except for enriched uranium), until 1986. The Department of Energy took the weapon from the museum to remove its inner components, so the bomb could not be stolen and detonated with fissile material. The government returned the emptied casing to the Smithsonian in 1993. Three other disarmed bombs are on display in the United States; another is at the Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum (IWM), currently branded "Imperial War Museums", is a British national museum. It is headquartered in London, with five branches in England. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, it was intended to record the civ ...

in London.

Notes

References

* * This report can also be founhere

an

here

* * * * * * This report can also be foun

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

at Carey Sublette's NuclearWeaponArchive.org

Definition and explanation of 'Little Boy'

Simulation of "Little Boy"

an interactive simulation of "Little Boy"

Little Boy 3D Model

information about preparation and dropping the Little Boy bomb

Little boy Nuclear Bomb at Imperial War museum London UK (jpg)

{{Authority control History of the Manhattan Project Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Gun-type nuclear bombs World War II weapons of the United States Code names Nuclear bombs of the United States Cold War aerial bombs of the United States Lockheed Corporation Articles containing video clips World War II aerial bombs of the United States Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1945