List Of Atheists In Science And Technology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a list of atheists in science and technology. A statement by a living person that he or she does not believe in God is not a sufficient criterion for inclusion in this

*

*

Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict

at

* Sir Edward Battersby Bailey FRS (1881–1965): British

* Sir Edward Battersby Bailey FRS (1881–1965): British

* Sir Howard Dalton FRS (1944–2008): British microbiologist, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs from March 2002 to September 2007.

* Richard Dawkins (1941–): English people, English

* Sir Howard Dalton FRS (1944–2008): British microbiologist, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs from March 2002 to September 2007.

* Richard Dawkins (1941–): English people, English

* Paul Ehrenfest (1880–1933): Austrian and Dutch people, Dutch

* Paul Ehrenfest (1880–1933): Austrian and Dutch people, Dutch

* George Gamow (1904–1968): Russian-born theoretical physicist and cosmologist. An early advocate and developer of Lemaître's Big Bang theory.

* Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1772–1850): French

* George Gamow (1904–1968): Russian-born theoretical physicist and cosmologist. An early advocate and developer of Lemaître's Big Bang theory.

* Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1772–1850): French

* Jacques Hadamard (1865–1963): France, French mathematician who made major contributions in

* Jacques Hadamard (1865–1963): France, French mathematician who made major contributions in

Joliot-Curie, Irène.

Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 17 Mar. 2012. * Steve Jones (biologist), Steve Jones (1944–): Wales, Welsh

* Daniel Kahneman (1934–): Israeli Americans, Israeli

* Daniel Kahneman (1934–): Israeli Americans, Israeli

* Jacques Lacan (1901–1981): French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who made prominent contributions to psychoanalysis and philosophy, and has been called "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud".

* Joseph Louis Lagrange (1736–1813): Italian mathematician and astronomer that made significant contributions to the fields of mathematical analysis, analysis,

* Jacques Lacan (1901–1981): French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who made prominent contributions to psychoanalysis and philosophy, and has been called "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud".

* Joseph Louis Lagrange (1736–1813): Italian mathematician and astronomer that made significant contributions to the fields of mathematical analysis, analysis,

* Paul MacCready (1925–2007): American aeronautical engineer. He was the founder of AeroVironment and the designer of the human-powered aircraft that won the Kremer prize.

* Ernst Mach (1838–1916): Austrian physicist and philosopher. Known for his contributions to physics such as the Mach number and the study of shock waves.

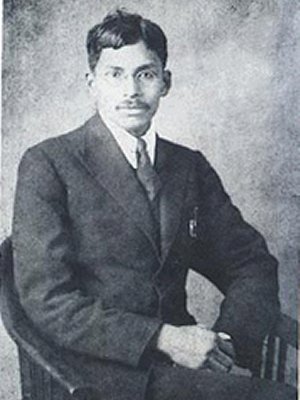

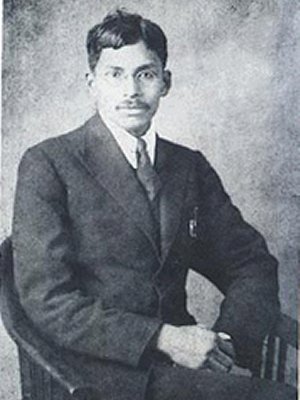

* Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis FRS (1893–1972): Indian scientist and applied statistician. He is best remembered for the Mahalanobis distance, a statistical measure and for being one of the members of the first Planning Commission (India), Planning commission of free india. He made pioneering studies in anthropometry in India and founded the Indian Statistical Institute.

* Paolo Mantegazza (1831–1910): Italian neurologist, physiologist and anthropologist, noted for his experimental investigation of coca leaves into its effects on the human psyche.

* Andrey Markov (1856–1922): Russian mathematician. He is best known for his work on stochastic processes.

*Phil Mason (1972–): British chemist at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences, who is known for his online activities and YouTube career.

* Abraham Maslow (1908–1970): American psychologist. He was a professor of psychology at Brandeis University, Brooklyn College, New School for Social Research and Columbia University who created Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

* Hiram Stevens Maxim (1840–1916): American-born British inventor. He invented the Maxim gun, the first portable, fully automatic machine gun; and other devices, including an elaborate mousetrap.

* Ernst Mayr (1904–2005): Renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, historian of science, and naturalist. He was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists.

* John McCarthy (computer scientist), John McCarthy (1927–2011): American computer scientist and cognitive scientist who received the Turing Award in 1971 for his major contributions to the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI). He was responsible for the coining of the term "Artificial Intelligence" in his 1955 proposal for the 1956 Dartmouth Conference and was the inventor of the Lisp (programming language), Lisp programming language.

* Peter Medawar, Sir Peter Medawar (1915–1987): Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Nobel Prize-winning British scientist best known for his work on how the immune system rejects or accepts tissue transplants.

* Simon van der Meer (1925–2011): Dutch particle accelerator

* Paul MacCready (1925–2007): American aeronautical engineer. He was the founder of AeroVironment and the designer of the human-powered aircraft that won the Kremer prize.

* Ernst Mach (1838–1916): Austrian physicist and philosopher. Known for his contributions to physics such as the Mach number and the study of shock waves.

* Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis FRS (1893–1972): Indian scientist and applied statistician. He is best remembered for the Mahalanobis distance, a statistical measure and for being one of the members of the first Planning Commission (India), Planning commission of free india. He made pioneering studies in anthropometry in India and founded the Indian Statistical Institute.

* Paolo Mantegazza (1831–1910): Italian neurologist, physiologist and anthropologist, noted for his experimental investigation of coca leaves into its effects on the human psyche.

* Andrey Markov (1856–1922): Russian mathematician. He is best known for his work on stochastic processes.

*Phil Mason (1972–): British chemist at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences, who is known for his online activities and YouTube career.

* Abraham Maslow (1908–1970): American psychologist. He was a professor of psychology at Brandeis University, Brooklyn College, New School for Social Research and Columbia University who created Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

* Hiram Stevens Maxim (1840–1916): American-born British inventor. He invented the Maxim gun, the first portable, fully automatic machine gun; and other devices, including an elaborate mousetrap.

* Ernst Mayr (1904–2005): Renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, historian of science, and naturalist. He was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists.

* John McCarthy (computer scientist), John McCarthy (1927–2011): American computer scientist and cognitive scientist who received the Turing Award in 1971 for his major contributions to the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI). He was responsible for the coining of the term "Artificial Intelligence" in his 1955 proposal for the 1956 Dartmouth Conference and was the inventor of the Lisp (programming language), Lisp programming language.

* Peter Medawar, Sir Peter Medawar (1915–1987): Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Nobel Prize-winning British scientist best known for his work on how the immune system rejects or accepts tissue transplants.

* Simon van der Meer (1925–2011): Dutch particle accelerator

* John Forbes Nash, Jr. (1928–2015): American mathematician whose works in game theory, differential geometry, and partial differential equations. He shared the 1994 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with game theorists Reinhard Selten and John Harsanyi.

* Yuval Ne'eman (1925–2006): Israeli theoretical physicist, military scientist, and politician. One of his greatest achievements in physics was his 1961 discovery of the classification of hadrons through the SU(3)flavour symmetry, now named the ''Eightfold Way (physics), Eightfold Way'', which was also proposed independently by Murray Gell-Mann.

* Ted Nelson: (1937–): American Innovator, pioneer of information technology, philosopher, and sociologist who coined the terms ''hypertext'' and ''hypermedia'' in 1963 and published them in 1965.

* Alfred Nobel (1833–1896): Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman, and philanthropist who is known for inventing dynamite and holding 355 patents. He was a benefactor of the

* John Forbes Nash, Jr. (1928–2015): American mathematician whose works in game theory, differential geometry, and partial differential equations. He shared the 1994 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with game theorists Reinhard Selten and John Harsanyi.

* Yuval Ne'eman (1925–2006): Israeli theoretical physicist, military scientist, and politician. One of his greatest achievements in physics was his 1961 discovery of the classification of hadrons through the SU(3)flavour symmetry, now named the ''Eightfold Way (physics), Eightfold Way'', which was also proposed independently by Murray Gell-Mann.

* Ted Nelson: (1937–): American Innovator, pioneer of information technology, philosopher, and sociologist who coined the terms ''hypertext'' and ''hypermedia'' in 1963 and published them in 1965.

* Alfred Nobel (1833–1896): Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman, and philanthropist who is known for inventing dynamite and holding 355 patents. He was a benefactor of the

* Mark Oliphant (1901–2000): Australian physicist and humanitarian. He played a fundamental role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and also the development of the

* Mark Oliphant (1901–2000): Australian physicist and humanitarian. He played a fundamental role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and also the development of the

* Linus Pauling (1901–1994): American chemist,

* Linus Pauling (1901–1994): American chemist,

* Isidor Isaac Rabi (1898–1988): American physicist and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Prize–winning scientist who discovered nuclear magnetic resonance in 1944 and was also one of the first scientists in the US to work on the cavity magnetron, which is used in microwave radar and microwave ovens.

* Frank P. Ramsey (1903–1930): British

* Isidor Isaac Rabi (1898–1988): American physicist and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Prize–winning scientist who discovered nuclear magnetic resonance in 1944 and was also one of the first scientists in the US to work on the cavity magnetron, which is used in microwave radar and microwave ovens.

* Frank P. Ramsey (1903–1930): British

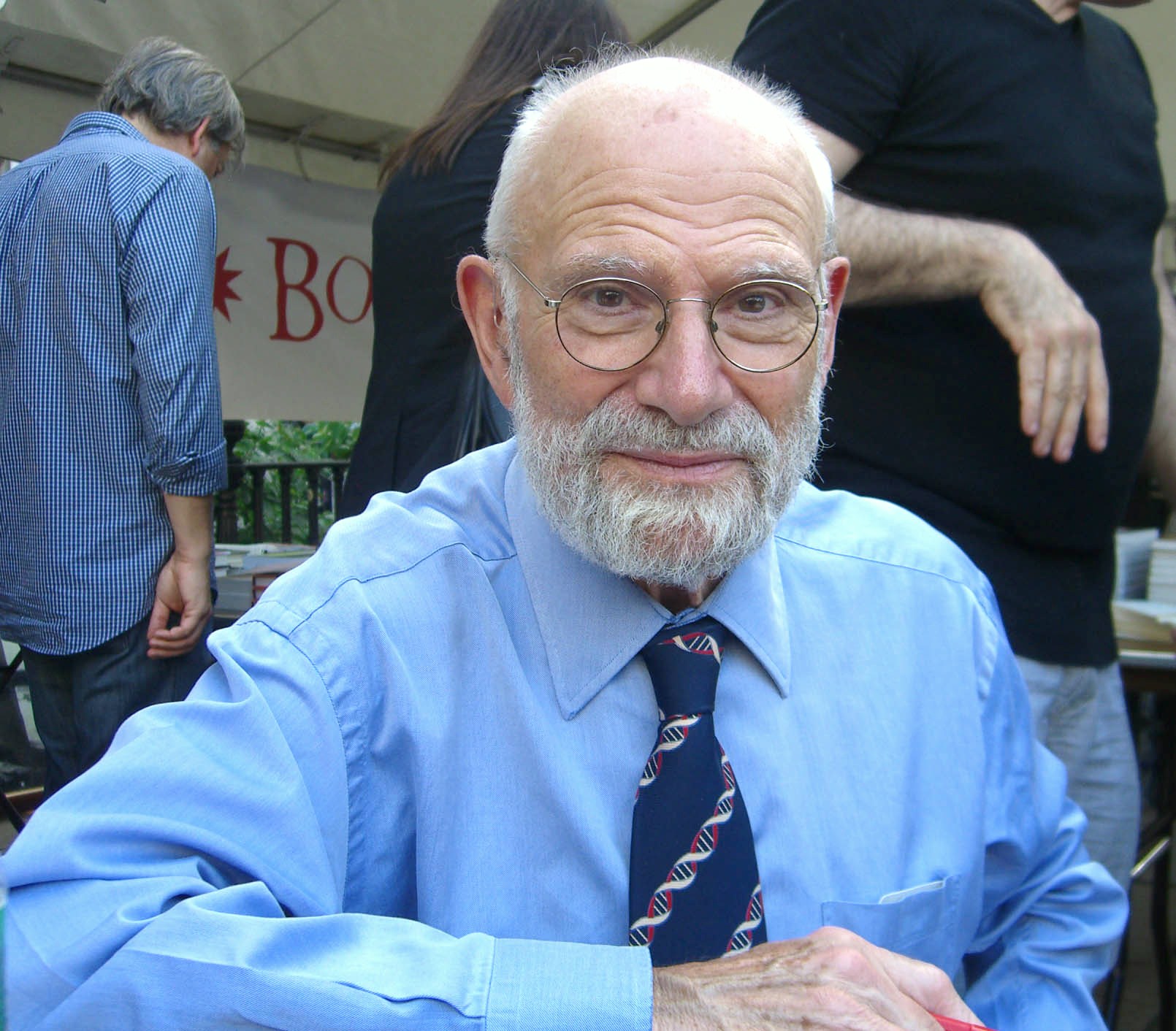

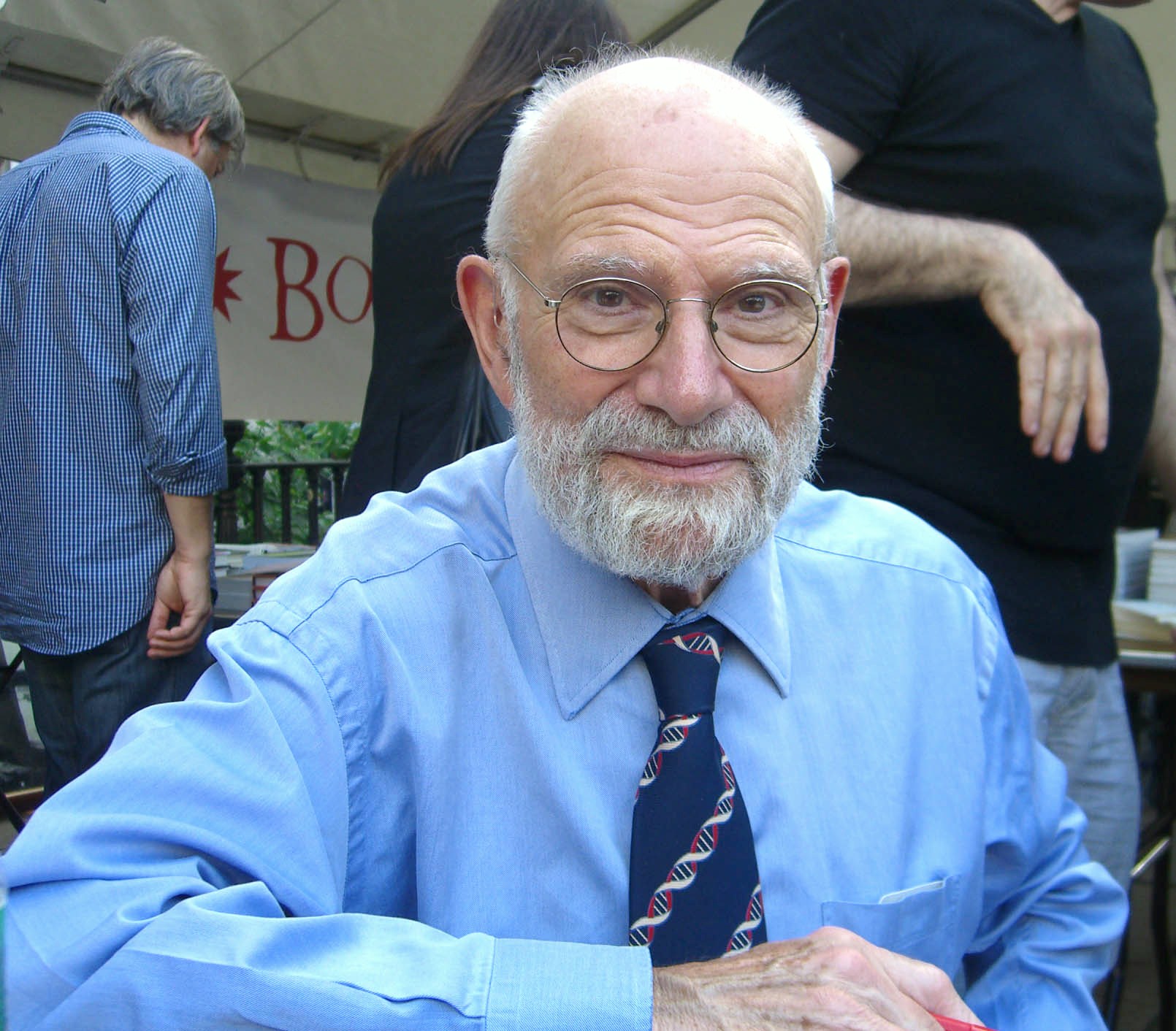

* Oliver Sacks (1933–2015): United States-based British neurologist, who has written popular books about his patients, the most famous of which is ''Awakenings (book), Awakenings''.

* Carl Sagan (1934–1996): American astronomer and astrochemist, a highly successful popularizer of astronomy, astrophysics, and other natural sciences, and pioneer of Astrobiology, exobiology and promoter of the SETI. Although Sagan has been identified as an atheist according to some definitions,

he rejected the label, stating "An atheist has to know a lot more than I know." He was an agnostic who, while maintaining that the idea of a creator of the universe was difficult to disprove, nevertheless disbelieved in God's existence, pending sufficient evidence.

*Meghnad Saha (1893–1956): Indian astrophysicist noted for his development in 1920 of the Thermal ionization, thermal ionization equation, which has remained fundamental in all work on stellar atmospheres. This equation has been widely applied to the interpretation of Astronomical spectroscopy, stellar spectra, which are characteristic of the chemical composition of the light source. The Saha equation links the composition and appearance of the spectrum with the temperature of the light source and can thus be used to determine either the temperature of the star or the Natural abundance, relative abundance of the chemical elements investigated.

*Andrei Sakharov (1921–1989):

* Oliver Sacks (1933–2015): United States-based British neurologist, who has written popular books about his patients, the most famous of which is ''Awakenings (book), Awakenings''.

* Carl Sagan (1934–1996): American astronomer and astrochemist, a highly successful popularizer of astronomy, astrophysics, and other natural sciences, and pioneer of Astrobiology, exobiology and promoter of the SETI. Although Sagan has been identified as an atheist according to some definitions,

he rejected the label, stating "An atheist has to know a lot more than I know." He was an agnostic who, while maintaining that the idea of a creator of the universe was difficult to disprove, nevertheless disbelieved in God's existence, pending sufficient evidence.

*Meghnad Saha (1893–1956): Indian astrophysicist noted for his development in 1920 of the Thermal ionization, thermal ionization equation, which has remained fundamental in all work on stellar atmospheres. This equation has been widely applied to the interpretation of Astronomical spectroscopy, stellar spectra, which are characteristic of the chemical composition of the light source. The Saha equation links the composition and appearance of the spectrum with the temperature of the light source and can thus be used to determine either the temperature of the star or the Natural abundance, relative abundance of the chemical elements investigated.

*Andrei Sakharov (1921–1989):

* Igor Tamm (1895–1971): Soviet physicist who received the 1958

* Igor Tamm (1895–1971): Soviet physicist who received the 1958

* Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943): Russian and Soviet botanist and geneticist best known for having identified the centres of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, corn, and other cereal crops that sustain the global population.

* J. Craig Venter (1946–): American biologist and entrepreneur, one of the first researchers to sequence the human genome, and in 2010 the first to create a cell with a synthetic genome.

* Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945): Russian and Soviet mineralogist and geochemist who is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and of radiogeology. His ideas of noosphere were an important contribution to Russian cosmism.

* Carl Vogt (1817–1895): German scientist, philosopher and politician who emigrated to Switzerland. Vogt published a number of notable works on zoology, geology and physiology.

* Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943): Russian and Soviet botanist and geneticist best known for having identified the centres of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, corn, and other cereal crops that sustain the global population.

* J. Craig Venter (1946–): American biologist and entrepreneur, one of the first researchers to sequence the human genome, and in 2010 the first to create a cell with a synthetic genome.

* Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945): Russian and Soviet mineralogist and geochemist who is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and of radiogeology. His ideas of noosphere were an important contribution to Russian cosmism.

* Carl Vogt (1817–1895): German scientist, philosopher and politician who emigrated to Switzerland. Vogt published a number of notable works on zoology, geology and physiology.

* William Grey Walter, W. Grey Walter (1910–1977): American neurophysiologist famous for his work on Neural oscillation, brain waves, and robotician.

* James D. Watson (1928–): Molecular biologist, physiologist, zoologist,

* William Grey Walter, W. Grey Walter (1910–1977): American neurophysiologist famous for his work on Neural oscillation, brain waves, and robotician.

* James D. Watson (1928–): Molecular biologist, physiologist, zoologist,

* Oscar Zariski (1899–1986): American mathematician and one of the most influential algebraic geometers of the 20th century.

* Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich (1914–1987):

* Oscar Zariski (1899–1986): American mathematician and one of the most influential algebraic geometers of the 20th century.

* Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich (1914–1987):

Twentieth Century Atheists

on

list

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

. Persons in this list are people (living or not) who both have publicly identified themselves as atheists and whose atheism is relevant to their notable activities or public life.

A

*

* Scott Aaronson

Scott Joel Aaronson (born May 21, 1981) is an American theoretical computer scientist and David J. Bruton Jr. Centennial Professor of Computer Science at the University of Texas at Austin. His primary areas of research are quantum computing ...

(1981–): American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

theoretical computer scientist and faculty member in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) is an academic program at many universities which comprises scientific and engineering aspects of computing. CSE is also a term often used in Europe to translate the name of engineering informatics academi ...

department at MIT. His primary area of research is quantum computing

Quantum computing is a type of computation whose operations can harness the phenomena of quantum mechanics, such as superposition, interference, and entanglement. Devices that perform quantum computations are known as quantum computers. Though ...

and computational complexity theory

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, computational complexity theory focuses on classifying computational problems according to their resource usage, and relating these classes to each other. A computational problem is a task solved ...

.

* Ernst Abbe

Ernst Karl Abbe HonFRMS (23 January 1840 – 14 January 1905) was a German physicist, optical scientist, entrepreneur, and social reformer. Together with Otto Schott and Carl Zeiss, he developed numerous optical instruments. He was also a c ...

(1840–1905): German physicist, optometrist, entrepreneur, and social reformer. Together with Otto Schott

Friedrich Otto Schott (1851–1935) was a German chemist, glass technologist, and the inventor of borosilicate glass. Schott systematically investigated the relationship between the chemical composition of the glass and its properties. In this wa ...

and Carl Zeiss

Carl Zeiss (; 11 September 1816 – 3 December 1888) was a German scientific instrument maker, optician and businessman. In 1846 he founded his workshop, which is still in business as Carl Zeiss AG. Zeiss gathered a group of gifted practica ...

, he laid the foundation of modern optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

. Abbe developed numerous optical instruments. He was a co-owner of Carl Zeiss AG

Carl Zeiss AG (), branded as ZEISS, is a German manufacturer of optical systems and optoelectronics, founded in Jena, Germany in 1846 by optician Carl Zeiss. Together with Ernst Abbe (joined 1866) and Otto Schott (joined 1884) he laid th ...

, a German manufacturer of research microscopes, astronomical telescopes, planetariums and other optical systems.

* Fay Ajzenberg-Selove

Fay Ajzenberg-Selove (February 13, 1926August 8, 2012) was an American nuclear physicist. She was known for her experimental work in nuclear spectroscopy of light elements, and for her annual reviews of the energy levels of light atomic nuclei. ...

(1926–2012): American nuclear physicist who was known for her experimental work in nuclear spectroscopy Nuclear spectroscopy is a superordinate concept of methods that uses properties of a nucleus to probe material properties. By emission or absorption of radiation from the nucleus information of the local structure is obtained, as an interaction of ...

of light elements, and for her annual reviews of the energy levels of light atomic nuclei. She was a recipient of the 2007 National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

.

* Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert (; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the '' Encyclopéd ...

(1717–1783): French mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, mechanician

A mechanician is an engineer or a scientist working in the field of mechanics, or in a related or sub-field: engineering or computational mechanics, applied mechanics, geomechanics, biomechanics, and mechanics of materials. Names other than mecha ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, and music theorist

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the " rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation ( ...

. He was also co-editor with Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

of the ''Encyclopédie

''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

''.

* Zhores Alferov

Zhores Ivanovich Alferov (russian: link=no, Жоре́с Ива́нович Алфёров, ; be, Жарэс Іва́навіч Алфёраў; 15 March 19301 March 2019) was a Soviet and Russian physicist and academic who contributed signific ...

(1930–2019): Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

ian, Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, and Russian physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who contributed substantially to the creation of modern heterostructure physics and electronics. He is an inventor of the heterotransistor and co-winner (with Herbert Kroemer and Jack Kilby

Jack St. Clair Kilby (November 8, 1923 – June 20, 2005) was an American electrical engineer who took part (along with Robert Noyce of Fairchild) in the realization of the first integrated circuit while working at Texas Instruments (TI) in 1 ...

) of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

.

* Hannes Alfvén

Hannes Olof Gösta Alfvén (; 30 May 1908 – 2 April 1995) was a Swedish electrical engineer, plasma physicist and winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). He described the class of MHD waves now ...

(1908–1995): Swedish electrical engineer and plasma physicist. He received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for his work on magnetohydrodynamics

Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD; also called magneto-fluid dynamics or hydromagnetics) is the study of the magnetic properties and behaviour of electrically conducting fluids. Examples of such magnetofluids include plasmas, liquid metals, ...

(MHD). He is best known for describing the class of MHD waves now known as Alfvén waves Alfvén may refer to:

People

* Hannes Alfvén (1908–1995), Swedish plasma physicist and Nobel Prize in Physics laureate

* Hugo Alfvén (1872–1960), Swedish composer, conductor, violinist, and painter

* Marie Triepcke Krøyer Alfvén (1867–19 ...

.

* Jim Al-Khalili

Jameel Sadik "Jim" Al-Khalili ( ar, جميل صادق الخليلي; born 20 September 1962) is an Iraqi-British theoretical physicist, author and broadcaster. He is professor of theoretical physics and chair in the public engagement in scie ...

OBE (1962–): Iraqi-born British quantum physicist, author and science communicator. He is professor of Theoretical Physics

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experim ...

and Chair in the Public Engagement in Science at the University of Surrey

The University of Surrey is a public research university in Guildford, Surrey, England. The university received its royal charter in 1966, along with a number of other institutions following recommendations in the Robbins Report. The institu ...

* Philip W. Anderson (1923–2020): American physicist. He was one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1977. Anderson has made contributions to the theories of localization, antiferromagnetism

In materials that exhibit antiferromagnetism, the magnetic moments of atoms or molecules, usually related to the spins of electrons, align in a regular pattern with neighboring spins (on different sublattices) pointing in opposite directions. ...

and high-temperature superconductivity

High-temperature superconductors (abbreviated high-c or HTS) are defined as materials that behave as superconductors at temperatures above , the boiling point of liquid nitrogen. The adjective "high temperature" is only in respect to previou ...

.

* Jacob Appelbaum

Jacob Appelbaum (born 1 April 1983) is an American independent journalist, computer security researcher, artist, and hacker. He studied at the Eindhoven University of Technology and was a core member of the Tor project, a free software networ ...

(1983–): American computer security

Computer security, cybersecurity (cyber security), or information technology security (IT security) is the protection of computer systems and networks from attack by malicious actors that may result in unauthorized information disclosure, t ...

researcher and hacker

A hacker is a person skilled in information technology who uses their technical knowledge to achieve a goal or overcome an obstacle, within a computerized system by non-standard means. Though the term ''hacker'' has become associated in popu ...

. He is a core member of the Tor project

Tor, short for The Onion Router, is free and open-source software for enabling anonymous communication. It directs Internet traffic through a free, worldwide, volunteer overlay network, consisting of more than seven thousand relays, to conc ...

.

* François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of t ...

(1786–1853): French mathematician, physicist, astronomer and politician.

* Svante Arrhenius

Svante August Arrhenius ( , ; 19 February 1859 – 2 October 1927) was a Swedish scientist. Originally a physicist, but often referred to as a chemist, Arrhenius was one of the founders of the science of physical chemistry. He received the Nob ...

(1859–1927): Swedish scientist and the first Swedish Nobel Prize winner.

* Abhay Ashtekar

Abhay Vasant Ashtekar (born 5 July 1949) is an Indian theoretical physicist. He is the Eberly Professor of Physics and the Director of the Institute for Gravitational Physics and Geometry at Pennsylvania State University. As the creator of Ash ...

(1949–): Indian theoretical physicist. As the creator of Ashtekar variables

In the ADM formulation of general relativity, spacetime is split into spatial slices and a time axis. The basic variables are taken to be the induced metric q_ (x) on the spatial slice and the metric's conjugate momentum K^ (x), which is relate ...

, he is one of the founders of loop quantum gravity

Loop quantum gravity (LQG) is a theory of quantum gravity, which aims to merge quantum mechanics and general relativity, incorporating matter of the Standard Model into the framework established for the pure quantum gravity case. It is an attem ...

and its subfield loop quantum cosmology

Loop quantum cosmology (LQC) is a finite, symmetry-reduced model of loop quantum gravity ( LQG) that predicts a "quantum bridge" between contracting and expanding cosmological branches.

The distinguishing feature of LQC is the prominent role play ...

.

* Larned B. Asprey (1919–2005): American chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

noted for his work on actinide

The actinide () or actinoid () series encompasses the 15 metallic chemical elements with atomic numbers from 89 to 103, actinium through lawrencium. The actinide series derives its name from the first element in the series, actinium. The info ...

, lanthanide

The lanthanide () or lanthanoid () series of chemical elements comprises the 15 metallic chemical elements with atomic numbers 57–71, from lanthanum through lutetium. These elements, along with the chemically similar elements scandium and yt ...

, rare earth, and fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element with the symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at standard conditions as a highly toxic, pale yellow diatomic gas. As the most electronegative reactive element, it is extremely reactiv ...

chemistry, and for his contributions to nuclear chemistry on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

and later at the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

.

* Peter Atkins

Peter William Atkins (born 10 August 1940) is an English chemist and a Fellow of Lincoln College at the University of Oxford. He retired in 2007. He is a prolific writer of popular chemistry textbooks, including ''Physical Chemistry'', ''I ...

(1940–): English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

quantum chemist and professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professo ...

of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

at Lincoln College, Oxford

Lincoln College (formally, The College of the Blessed Mary and All Saints, Lincoln) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford, situated on Turl Street in central Oxford. Lincoln was founded in 1427 by Richard Fleming, th ...

, in England.

* Scott Atran (1952–): American-French cultural anthropologist

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The portman ...

who is Emeritus Director of Research in Anthropology at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique

The French National Centre for Scientific Research (french: link=no, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, CNRS) is the French state research organisation and is the largest fundamental science agency in Europe.

In 2016, it employed 31,63 ...

in Paris, Research Professor at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

, and cofounder of ARTIS International and of thCentre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict

at

Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

.

* Julius Axelrod (1912–2004): American Nobel Prize–winning biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of "biological ch ...

, noted for his work on the release and reuptake of catecholamine

A catecholamine (; abbreviated CA) is a monoamine neurotransmitter, an organic compound that has a catechol (benzene with two hydroxyl side groups next to each other) and a side-chain amine.

Catechol can be either a free molecule or a su ...

neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, any main body part or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neu ...

s and major contributions to the understanding of the pineal gland

The pineal gland, conarium, or epiphysis cerebri, is a small endocrine gland in the brain of most vertebrates. The pineal gland produces melatonin, a serotonin-derived hormone which modulates sleep patterns in both circadian and seasonal cy ...

and how it is regulated during the sleep-wake cycle.

B

* Sir Edward Battersby Bailey FRS (1881–1965): British

* Sir Edward Battersby Bailey FRS (1881–1965): British geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

, director of the British Geological Survey.

* Gregory Bateson

Gregory Bateson (9 May 1904 – 4 July 1980) was an English anthropologist, social scientist, linguist, visual anthropologist, semiotician, and cyberneticist whose work intersected that of many other fields. His writings include ''Steps to ...

(1904–1980): English anthropologist, social scientist, linguist, visual anthropologist, semiotician and cyberneticist whose work intersected that of many other fields.

* Sir Patrick Bateson

Sir Paul Patrick Gordon Bateson, (31 March 1938 – 1 August 2017) was an English biologist with interests in ethology and phenotypic plasticity. Bateson was a professor at the University of Cambridge and served as president of the Zoologic ...

FRS (1938–2017): English biologist and science writer, Emeritus Professor of ethology at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

and president of the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained the London Zoo, and since 1931 Whipsnade Park.

History

On 29 ...

.

* William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

(1861–1926): English geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

, a Fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corporation established by a charter dated 9 April 1511. The ...

, where he eventually became Master. He was the first person to use the term "genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

" to describe the study of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

and biological inheritance

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

following their rediscovery.

* George Beadle (1903–1989): American scientist in the field of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

, and Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accordi ...

laureate who, with Edward Tatum, discovered the role of genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

in regulating biochemical events within cells in 1958.

* John Stewart Bell

John Stewart Bell FRS (28 July 1928 – 1 October 1990) was a physicist from Northern Ireland and the originator of Bell's theorem, an important theorem in quantum physics regarding hidden-variable theories.

In 2022, the Nobel Prize in Phy ...

FRS (1928–1990): Irish physicist. Best known for his discovery of Bell's theorem.

* Richard E. Bellman

Richard Ernest Bellman (August 26, 1920 – March 19, 1984) was an American applied mathematician, who introduced dynamic programming in 1953, and made important contributions in other fields of mathematics, such as biomathematics. He founde ...

(1920–1984): American applied mathematician, best known for his invention of dynamic programming

Dynamic programming is both a mathematical optimization method and a computer programming method. The method was developed by Richard Bellman in the 1950s and has found applications in numerous fields, from aerospace engineering to economics.

...

in 1953, along with other important contributions in other fields of mathematics.

* Charles H. Bennett (1943–): American physicist, information theorist and IBM Fellow at IBM Research

IBM Research is the research and development division for IBM, an American multinational information technology company headquartered in Armonk, New York, with operations in over 170 countries. IBM Research is the largest industrial research or ...

. He is best known for his work in quantum cryptography

Quantum cryptography is the science of exploiting quantum mechanical properties to perform cryptographic tasks. The best known example of quantum cryptography is quantum key distribution which offers an information-theoretically secure solution ...

, quantum teleportation and is one of the founding fathers of modern quantum information theory

Quantum information is the information of the quantum state, state of a quantum system. It is the basic entity of study in quantum information theory, and can be manipulated using quantum information processing techniques. Quantum information re ...

.

*John Desmond Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

(1901–1971): British biophysicist. Best known for pioneering X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

in molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and phys ...

.

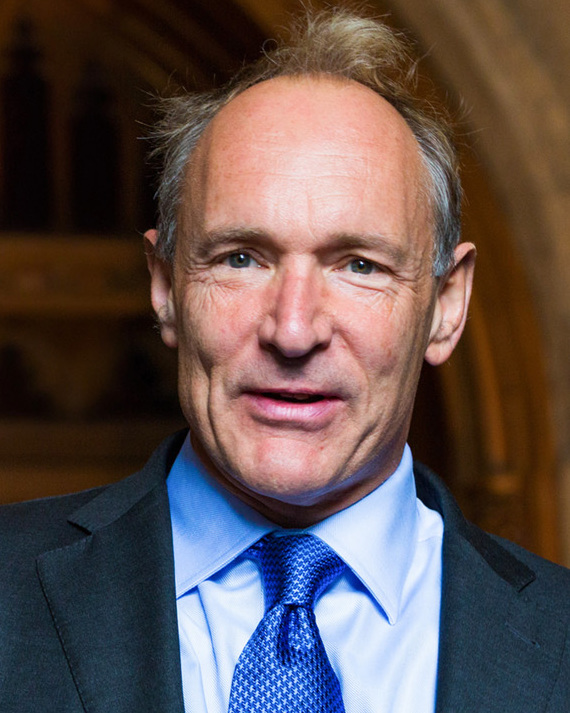

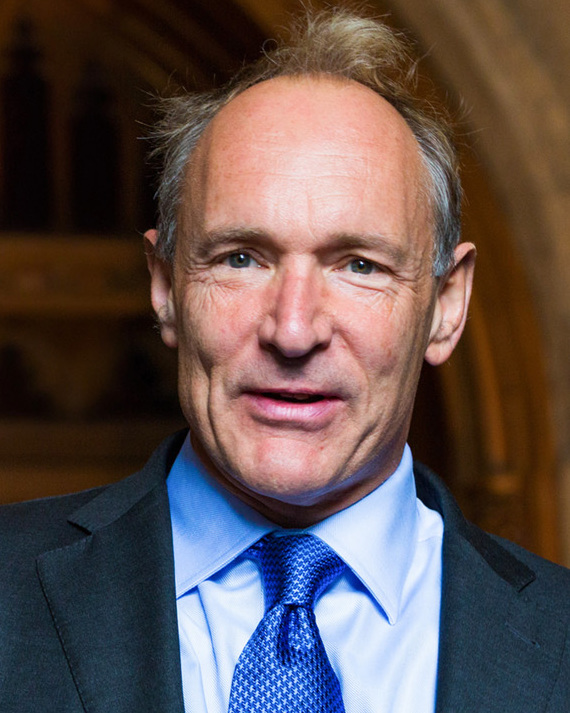

*Tim Berners-Lee

Sir Timothy John Berners-Lee (born 8 June 1955), also known as TimBL, is an English computer scientist best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web. He is a Professorial Fellow of Computer Science at the University of Oxford and a profes ...

(1955–): English computer scientist, best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web

The World Wide Web (WWW), commonly known as the Web, is an information system enabling documents and other web resources to be accessed over the Internet.

Documents and downloadable media are made available to the network through web ...

.

* Marcellin Berthelot

Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot (; 25 October 1827 – 18 March 1907) was a French chemist and Republican politician noted for the ThomsenBerthelot principle of thermochemistry. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substa ...

(1827–1907): French chemist and politician noted for the Thomsen-Berthelot principle of thermochemistry

Thermochemistry is the study of the heat energy which is associated with chemical reactions and/or phase changes such as melting and boiling. A reaction may release or absorb energy, and a phase change may do the same. Thermochemistry focuses on ...

. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substances and disproved the theory of vitalism.

* Claude Louis Berthollet

Claude Louis Berthollet (, 9 December 1748 – 6 November 1822) was a Savoyard-French chemist who became vice president of the French Senate in 1804. He is known for his scientific contributions to theory of chemical equilibria via the mecha ...

(1748–1822): French chemist."Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

replies: "How comes it, then, that Laplace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

was an atheist? At the Institute neither he nor Monge

Gaspard Monge, Comte de Péluse (9 May 1746 – 28 July 1818) was a French mathematician, commonly presented as the inventor of descriptive geometry, (the mathematical basis of) technical drawing, and the father of differential geometry. During ...

, nor Berthollet, nor Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (born Giuseppe Luigi LagrangiaGaspard Gourgaud

Gaspard, Baron Gourgaud (September 14, 1783 – July 25, 1852), also known simply as Gaspard Gourgaud, was a French soldier, prominent in the Napoleonic wars.

Biography

He was born at Versailles; his father was a musician of the royal chapel. At s ...

, ''Talks of Napoleon at St. Helena with General Baron Gourgaud'' (1904), page 274.

* Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

(1906–2005): German-American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

, and Nobel laureate in physics for his work on the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis

Stellar nucleosynthesis is the creation (nucleosynthesis) of chemical elements by nuclear fusion reactions within stars. Stellar nucleosynthesis has occurred since the original creation of hydrogen, helium and lithium during the Big Bang. A ...

. A versatile theoretical physicist, Bethe also made important contributions to quantum electrodynamics

In particle physics, quantum electrodynamics (QED) is the relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics. In essence, it describes how light and matter interact and is the first theory where full agreement between quantum mechanics and spec ...

, nuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies t ...

, solid-state physics

Solid-state physics is the study of rigid matter, or solids, through methods such as quantum mechanics, crystallography, electromagnetism, and metallurgy. It is the largest branch of condensed matter physics. Solid-state physics studies how th ...

and astrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline said, Astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the nature of the h ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, he was head of the Theoretical Division at the secret Los Alamos laboratory which developed the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s. There he played a key role in calculating the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

of the weapons, and did theoretical work on the implosion method used in both the Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

and the "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

" weapon dropped on Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, Japan.

* Norman Bethune (1890–1939): Canadian physician and medical innovator.

* Patrick Blackett

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett (18 November 1897 – 13 July 1974) was a British experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism, winning the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1948. ...

OM, CH, FRS (1897–1974): Nobel Prize-winning English experimental

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs when a ...

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

known for his work on cloud chamber

A cloud chamber, also known as a Wilson cloud chamber, is a particle detector used for visualizing the passage of ionizing radiation.

A cloud chamber consists of a sealed environment containing a supersaturated vapour of water or alcohol. An ...

s, cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

s, and paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism (or palaeomagnetismsee ), is the study of magnetic fields recorded in rocks, sediment, or archeological materials. Geophysicists who specialize in paleomagnetism are called ''paleomagnetists.''

Certain magnetic minerals in roc ...

.

* Colin Blakemore

Sir Colin Blakemore, , Hon (1 June 1944 – 27 June 2022) was a British neurobiologist, specialising in vision and the development of the brain. He was Yeung Kin Man Professor of Neuroscience and senior fellow of the Hong Kong Institute for Ad ...

(1944–2022): British neurobiologist

A neuroscientist (or neurobiologist) is a scientist who has specialised knowledge in neuroscience, a branch of biology that deals with the physiology, biochemistry, psychology, anatomy and molecular biology of neurons, neural circuits, and glial c ...

, specialising in vision

Vision, Visions, or The Vision may refer to:

Perception Optical perception

* Visual perception, the sense of sight

* Visual system, the physical mechanism of eyesight

* Computer vision, a field dealing with how computers can be made to gain und ...

and the development of the brain, who is Professor of Neuroscience and Philosophy in the School of Advanced Study

The School of Advanced Study (SAS), a postgraduate institution of the University of London, is the UK's national centre for the promotion and facilitation of research in the humanities and social sciences. It was established in 1994 and is ba ...

, University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degr ...

and Emeritus Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

.

* Christian Bohr

Christian Harald Lauritz Peter Emil Bohr (1855–1911) was a Danish physician, father of the physicist and Nobel laureate Niels Bohr, as well as the mathematician and football player Harald Bohr and grandfather of another physicist and Nobel lau ...

(1855–1911): Danish physician; father of physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make o ...

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

, and of mathematician Harald Bohr

Harald August Bohr (22 April 1887 – 22 January 1951) was a Danish mathematician and footballer. After receiving his doctorate in 1910, Bohr became an eminent mathematician, founding the field of almost periodic functions. His brother was the ...

; grandfather of physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and Nobel laureate Aage Bohr

Aage Niels Bohr (; 19 June 1922 – 8 September 2009) was a Danish nuclear physicist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1975 with Ben Roy Mottelson and James Rainwater "for the discovery of the connection between collective motion and pa ...

. Christian Bohr is known for having characterized respiratory dead space

''Dead Space'' is a science fiction/ horror media franchise created by Glen Schofield and Michael Condrey, developed by Visceral Games, and published and owned by Electronic Arts. The franchise's chronology is not presented in a linear format; e ...

and described the Bohr effect

The Bohr effect is a phenomenon first described in 1904 by the Danish physiologist Christian Bohr. Hemoglobin's oxygen binding affinity (see oxygen–haemoglobin dissociation curve) is inversely related both to acidity and to the concentration o ...

.

* Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

(1885–1962): Danish physicist. Best known for his foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1922.

* Sir Hermann Bondi KCB, FRS (1919–2005): Anglo-Austrian mathematician and cosmologist

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

, best known for co-developing the steady-state theory of the universe and important contributions to the theory of general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

.

* Paul D. Boyer

Paul Delos Boyer (July 31, 1918 – June 2, 2018) was an American biochemist, analytical chemist, and a professor of chemistry at University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). He shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for research on the "enzy ...

(1918–2018): American biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of "biological ch ...

and Nobel Laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make o ...

in Chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

in 1997.

* Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner (13 January 1927 – 5 April 2019) was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to work ...

(1927–2019): South African molecular biologist

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physic ...

and a 2002 Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accordi ...

laureate, shared with Bob Horvitz and John Sulston

Sir John Edward Sulston (27 March 1942 – 6 March 2018) was a British biologist and academic who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the cell lineage and genome of the worm ''Caenorhabditis elegans'' in 2002 with ...

. Brenner made significant contributions to work on the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

, and other areas of molecular biology while working in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology

The Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) is a research institute in Cambridge, England, involved in the revolution in molecular biology which occurred in the 1950–60s. Since then it has remained a major medical r ...

in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

.

* Calvin Bridges

Calvin Blackman Bridges (January 11, 1889 – December 27, 1938) was an American scientist known for his contributions to the field of genetics. Along with Alfred Sturtevant and H.J. Muller, Bridges was part of Thomas Hunt Morgan's famous "Fl ...

(1889–1938): American geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

, known especially for his work on fruit fly genetics.

* Percy Williams Bridgman

Percy Williams Bridgman (April 21, 1882 – August 20, 1961) was an American physicist who received the 1946 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the physics of high pressures. He also wrote extensively on the scientific method and on other as ...

(1882–1961): American physicist who won the 1946 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for his work on the physics of high pressures.

* Louis de Broglie

Louis Victor Pierre Raymond, 7th Duc de Broglie (, also , or ; 15 August 1892 – 19 March 1987) was a French physicist and aristocrat who made groundbreaking contributions to Old quantum theory, quantum theory. In his 1924 PhD thesis, he pos ...

(1892–1987): French physicist who made groundbreaking contributions to quantum theory and won the Nobel Prize for Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1929.

* Ruth Mack Brunswick Ruth Jane Mack Brunswick (February 17, 1897 – January 24, 1946), born Ruth Jane Mack, was an American psychiatrist. Mack was initially a student and later a close confidant of and collaborator with Sigmund Freud and was responsible for much of the ...

(1897–1946): American psychologist, a close confidant of and collaborator with Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

.

* Mario Bunge

Mario Augusto Bunge (; ; September 21, 1919 – February 24, 2020) was an Argentine-Canadian philosopher and physicist. His philosophical writings combined scientific realism, systemism, materialism, emergentism, and other principles.

He was ...

(1919–2020): Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, ...

-Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

and physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

. His philosophical writings combined scientific realism

Scientific realism is the view that the universe described by science is real regardless of how it may be interpreted.

Within philosophy of science, this view is often an answer to the question "how is the success of science to be explained?" T ...

, systemism, materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

, emergentism

In philosophy, emergentism is the belief in emergence, particularly as it involves consciousness and the philosophy of mind. A property of a system is said to be emergent if it is a new outcome of some other properties of the system and their in ...

, and other principles.

* Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, (3 September 1899 – 31 August 1985), usually known as Macfarlane or Mac Burnet, was an Australian virologist known for his contributions to immunology. He won a Nobel Prize in 1960 for predicting acquired immune ...

FRS FAA FRSNZ (1899–1985): Australian virologist best known for his contributions to immunology. He won the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1960 for predicting acquired immune tolerance and was best known for developing the theory of clonal selection

In immunology, clonal selection theory explains the functions of cells of the immune system (lymphocytes) in response to specific antigens invading the body. The concept was introduced by Australian doctor Frank Macfarlane Burnet in 1957, in an ...

.

* Geoffrey Burnstock

Geoffrey Burnstock (10 May 1929 – 2 June 2020) was a neurobiologist and President of the Autonomic Neuroscience Centre of the UCL Medical School. He is best known for coining the term purinergic signalling, which he discovered in the 19 ...

(1929–2020): Australian neurobiologist

A neuroscientist (or neurobiologist) is a scientist who has specialised knowledge in neuroscience, a branch of biology that deals with the physiology, biochemistry, psychology, anatomy and molecular biology of neurons, neural circuits, and glial c ...

and President of the Autonomic Neuroscience Centre of the UCL Medical School

UCL Medical School is the medical school of University College London (UCL) and is located in London, United Kingdom. The School provides a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate medical education programmes and also has a medical educatio ...

. He is best known for coining the term purinergic signaling

Purinergic signalling (or signaling: see American and British English differences) is a form of extracellular signalling mediated by purine nucleotides and nucleosides such as adenosine and ATP. It involves the activation of purinergic receptor ...

, which he discovered in the 1970s. He played a key role in the discovery of ATP as neurotransmitter.

C

* Robert Cailliau (1947–): Belgian informatics engineer and computer scientist who, together with Sir Tim Berners-Lee, developed theWorld Wide Web

The World Wide Web (WWW), commonly known as the Web, is an information system enabling documents and other web resources to be accessed over the Internet.

Documents and downloadable media are made available to the network through web ...

.

* Sir Paul Callaghan (1947–2012): New Zealand physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who, as the founding director of the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology

The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology (often simply called the MacDiarmid Institute) is a New Zealand Centre of Research Excellence (CoRE) specialising in materials science and nanotechnology. It is hosted by Victo ...

at Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington ( mi, Te Herenga Waka) is a university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of Parliament, and was a constituent college of the University of New Zealand.

The university is well kn ...

, held the position of Alan MacDiarmid Professor of Physical Sciences and was President of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance.

* Sean B. Carroll

Sean B. Carroll (born September 17, 1960) is an American Evolutionary developmental biology, evolutionary developmental biologist, author, educator and executive producer. He is a distinguished university professor at the University of Marylan ...

(1960–): American evolutionary developmental biologist, author, educator and executive producer. He is the Allan Wilson Professor of Molecular Biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and phys ...

and Genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

.

* Sean M. Carroll

Sean Michael Carroll (born October 5, 1966) is an American theoretical physicist and philosopher who specializes in quantum mechanics, gravity, and cosmology. He is (formerly) a research professor in the Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical ...

(1966–): American cosmologist

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

and theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experime ...

specializing in dark energy and general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

.

* Raymond Cattell

Raymond Bernard Cattell (20 March 1905 – 2 February 1998) was a British-American psychologist, known for his psychometric research into intrapersonal psychological structure.Gillis, J. (2014). ''Psychology's Secret Genius: The Lives and Works ...

(1905–1998): British and American psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the pre ...

, known for his psychometric research into intrapersonal psychological structure and his exploration of many areas within empirical psychology. Cattell authored, co-authored, or edited almost 60 scholarly books, more than 500 research articles, and over 30 standardized psychometric tests, questionnaires, and rating scales and was among the most productive, but controversial psychologists of the 20th century.

* James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

(1891–1974): English physicist. He won the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for his discovery of the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the atomic nucleus, nuclei of atoms. Since protons and ...

.

* Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (; ) (19 October 1910 – 21 August 1995) was an Indian-American theoretical physicist who spent his professional life in the United States. He shared the 1983 Nobel Prize for Physics with William A. Fowler for " ...

(1910–1995): Indian-American

Indian Americans or Indo-Americans are citizens of the United States with ancestry from India. The United States Census Bureau uses the term Asian Indian to avoid confusion with Native Americans, who have also historically been referred t ...

astrophysicist known for his theoretical work on the structure and evolution of stars. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1983.

* Georges Charpak (1924–2010): French physicist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1992.

* Boris Chertok

Boris Yevseyevich Chertok (russian: link=no, Бори́с Евсе́евич Черто́к; – 14 December 2011) was a Russian electrical engineer and the control systems designer in the Soviet Union's space program, and later found employm ...

(1912–2011): Prominent Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

n rocket