List of Christians in science and technology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a list of Christians in Science and Technology. People

in this list should have their Christianity as relevant to their notable activities or public life, and who have publicly identified themselves as Christians or as of a Christian denomination.

*

*

Before the 18th century

*

*Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen (german: Hildegard von Bingen; la, Hildegardis Bingensis; 17 September 1179), also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher ...

(1098–1179): also known as Saint Hildegard and Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess. She is considered to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany

*Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste, ', ', or ') or the gallicised Robert Grosstête ( ; la, Robertus Grossetesta or '). Also known as Robert of Lincoln ( la, Robertus Lincolniensis, ', &c.) or Rupert of Lincoln ( la, Rubertus Lincolniensis, &c.). ( ; la, Rob ...

(c.1175–1253): Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

, he was the central character of the English intellectual movement in the first half of the 13th century and is considered the founder of scientific thought in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. He had a great interest in the natural world and wrote texts on the mathematical sciences of optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

and geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

. He affirmed that experiments should be used in order to verify a theory, testing its consequences and added greatly to the development of the scientific method.

*Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop. Later canonised as a Catholic saint, he was known during his li ...

(c.1193–1280): patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of scientists in Catholicism who may have been the first to isolate arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

. He wrote that: "Natural science does not consist in ratifying what others have said, but in seeking the causes of phenomena." Yet he rejected elements of Aristotelianism that conflicted with Catholicism and drew on his faith as well as Neo-Platonic ideas to "balance" "troubling" Aristotelian elements.In 1252 he helped appoint Thomas Aquinas to a Dominican theological chair in Paris to lead the suppression of these dangerous ideas.

*Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the wor ...

(1300–58): French philosopher and priest. One of his most significant contributions to science was the development of the theory of impetus

The theory of impetus was an auxiliary or secondary theory of Aristotelian dynamics, put forth initially to explain projectile motion against gravity. It was introduced by John Philoponus in the 6th century, and elaborated by Nur ad-Din al-Bitru ...

, that explained the movement of projectiles and objects in free-fall

In Newtonian physics, free fall is any motion of a body where gravity is the only force acting upon it. In the context of general relativity, where gravitation is reduced to a space-time curvature, a body in free fall has no force acting on i ...

. This theory gave way to the dynamics of Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He wa ...

and for Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

's famous principle of inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

.

*Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; c. 1320–1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology an ...

(c.1323–1382): Theologian and bishop of Lisieux

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, he was one of the early founders and popularizers of modern sciences. One of his many scientific contributions is the discovery of the curvature of light through atmospheric refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenome ...

.

*Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 11 August 1464), also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus (), was a German Catholic cardinal, philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician, and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Re ...

(1401–1464): Catholic cardinal and theologian who made contributions to the field of mathematics by developing the concepts of the infinitesimal and of relative motion. His philosophical speculations also anticipated Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

' heliocentric world-view.

*Otto Brunfels

Otto Brunfels (also known as Brunsfels or Braunfels) (believed to be born in 1488 – 23 November 1534) was a German theologian and botanist. Carl von Linné listed him among the "Fathers of Botany".

Life

After studying theology and philosophy ...

(1488–1534): A theologian and botanist from Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

, Germany. His ''Catalogi virorum illustrium'' is considered to be the first book on the history of evangelical sects that had broken away from the Catholic Church. In botany his ''Herbarum vivae icones'' helped earn him acclaim as one of the "fathers of botany".

* William Turner (c.1508–1568): sometimes called the "father of English botany" and was also an ornithologist. He was arrested for preaching in favor of the Reformation. He later became a Dean of Wells Cathedral

Wells Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Wells, Somerset, England, dedicated to St Andrew the Apostle. It is the seat of the Bishop of Bath and Wells, whose cathedra it holds as mother church of the Diocese of Bath and Wells. Built as a ...

, but was expelled for nonconformity.

*Ignazio Danti

Ignazio (Egnation or Egnazio) Danti, O.P. (April 1536 – 10 October 1586), born Pellegrino Rainaldi Danti, was an Italian Roman Catholic prelate, mathematician, astronomer, and cosmographer, who served as Bishop of Alatri (1583–1586). ''(in ...

(1536–1586): As bishop of Alatri he convoked a diocesan synod to deal with abuses. He was also a mathematician who wrote on Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

, an astronomer, and a designer of mechanical devices.

*John Napier

John Napier of Merchiston (; 1 February 1550 – 4 April 1617), nicknamed Marvellous Merchiston, was a Scottish landowner known as a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer. He was the 8th Laird of Merchiston. His Latinized name was Ioan ...

(1550–1617): Scottish mathematician, physicist, and astronomer, best known as the discoverer of logarithms and inventor of Napier's bones. He was a fervent Protestant and published ''The Plaine Discovery of the Whole Revelation of St. John'' (1593), which he considered his most important work. The work occupies a prominent place in Scottish ecclesiastical history.

*Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

(1561–1626): Considered among the fathers of empiricism and is credited with establishing the inductive method of experimental science via what is called the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

today.

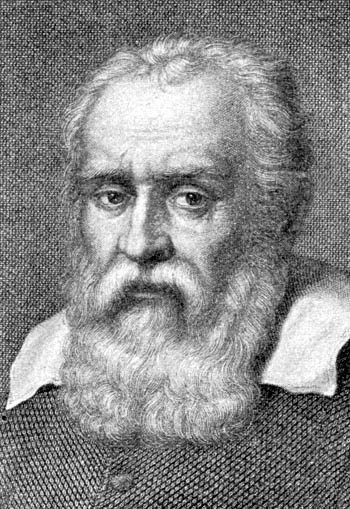

*Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He wa ...

(1564–1642): Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher, and mathematician who played a major role in the scientific revolution during the Renaissance.

* Laurentius Gothus (1565–1646): A professor of astronomy and Archbishop of Uppsala. He wrote on astronomy and theology.

* Johannes Kepler (1571–1630): Prominent astronomer of the Scientific Revolution, discovered Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

*Pierre Gassendi

Pierre Gassendi (; also Pierre Gassend, Petrus Gassendi; 22 January 1592 – 24 October 1655) was a French philosopher, Catholic priest, astronomer, and mathematician. While he held a church position in south-east France, he also spent much t ...

(1592–1655): Catholic priest who tried to reconcile Atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms ...

with Christianity. He also published the first work on the Transit of Mercury

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Mercury across the Sun takes place when the planet Mercury passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet. During a transit, Mercury appears as a tiny black dot moving across the Sun as the planet obs ...

and corrected the geographical coordinates of the Mediterranean Sea.

* Anton Maria of Rheita (1597–1660): Capuchin astronomer. He dedicated one of his astronomy books to Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, a "theo-astronomy" work was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

, and he wondered if beings on other planets were "cursed by original sin like humans are."

* Juan Lobkowitz (1606–1682): Cistercian monk

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

who did work on Combinatorics and published astronomy tables at age 10. He also did works of theology and sermons.

* Seth Ward (1617–1689): Anglican Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset. The see is in the City of Salisbury where the bishop's seat ...

and Savilian Chair of Astronomy from 1649 to 1661. He wrote ''Ismaelis Bullialdi astro-nomiae philolaicae fundamenta inquisitio brevis'' and ''Astronomia geometrica.'' He also had a theological/philosophical dispute with Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

and as a bishop was severe toward nonconformists.

* Blaise Pascal (1623–1662): Jansenist

Jansenism was an early modern theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It was declared a heresy by th ...

thinker;Although Jansenism was a movement within Roman Catholicism, it was generally opposed by the Catholic hierarchy and was eventually condemned as heretical. well known for Pascal's law

Pascal's law (also Pascal's principle or the principle of transmission of fluid-pressure) is a principle in fluid mechanics given by Blaise Pascal that states that a pressure change at any point in a confined incompressible fluid is transmitted ...

(physics), Pascal's theorem

In projective geometry, Pascal's theorem (also known as the ''hexagrammum mysticum theorem'') states that if six arbitrary points are chosen on a conic (which may be an ellipse, parabola or hyperbola in an appropriate affine plane) and joined ...

(math), Pascal's calculator (computing) and Pascal's Wager (theology).

* John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the f ...

, FRS (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

* Francesco Redi (1626–1697): Italian physician and Roman Catholic who is remembered as the "father of modern parasitology".

*Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

(1627–1691): Prominent scientist and theologian who argued that the study of science could improve glorification of God. A strong Christian apologist, he is considered one of the most important figures in the history of Chemistry.

* Isaac Barrow (1630–1677): English theologian, scientist, and mathematician. He wrote ''Expositions of the Creed, The Lord's Prayer, Decalogue, and Sacraments'' and ''Lectiones Opticae et Geometricae.''

*Nicolas Steno

Niels Steensen ( da, Niels Steensen; Latinized to ''Nicolaus Steno'' or ''Nicolaus Stenonius''; 1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686beatification

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their nam ...

in that faith occurred in 1987. As a scientist he is considered a pioneer in both anatomy and geology, but largely abandoned science after his religious conversion.

*Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

(1643–1727): Prominent scientist during the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

. Physicist, discoverer of gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

.

18th century (1701–1800)

* John Ray (1627–1705): English botanist who wrote ''The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation'' (1691) and was among the first to attempt a biological definition for the concept of ''species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

''. The John Ray Initiative of Environment and Christianity is also named for him.

*Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

(1646–1716): He was a philosopher who developed the philosophical theory of the Pre-established harmony; he is also most noted for his optimism, e.g., his conclusion that our Universe is, in a restricted sense, the best possible one that God could have created. He also made major contributions to mathematics, physics, and technology. He created the Stepped Reckoner and his Protogaea

''Protogaea'' is a work by Gottfried Leibniz on geology and natural history. Unpublished in his lifetime, but made known by Johann Georg von Eckhart in 1719, it was conceived as a preface to his incomplete history of the House of Brunswick.

Lif ...

concerns geology and natural history. He was a Lutheran who worked with convert to Catholicism John Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

John Frederick (german: Johann Friedrich; 25 April 1625 in Herzberg am Harz – 18 December 1679 in Augsburg) was duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. He ruled over the Principality of Calenberg, a subdivision of the duchy, from 1665 until his death.

T ...

in hopes of a reunification between Catholicism and Lutheranism.

* Pierre Varignon (1654–1722): French mathematician and Catholic priest known for his contributions to statics and mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to object ...

.

* Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723): Dutch Reformed Calvinist who is remembered as the "father of microbiology".

*Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (17 September 16774 January 1761) was an English clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, pneumatic chemistry and physiology. He was the first person to measure blood pressure. He al ...

(1677–1761): Copley Medal winning scientist significant to the study of plant physiology. As an inventor designed a type of ventilation system, a means to distill sea-water, ways to preserve meat, etc. In religion he was an Anglican curate who worked with the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) is a UK-based Christian charity. Founded in 1698 by Thomas Bray, it has worked for over 300 years to increase awareness of the Christian faith in the UK and across the world.

The SPCK is t ...

and for a group working to convert black slaves in the West Indies.

* Firmin Abauzit (1679–1767): physicist and theologian. He translated the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

into French and corrected an error in Newton's Principia.

*Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had a ...

(1688–1772): He did a great deal of scientific research with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences having commissioned work by him. His religious writing is the basis of Swedenborgianism and several of his theological works contained some science hypotheses, most notably the Nebular hypothesis

The nebular hypothesis is the most widely accepted model in the field of cosmogony to explain the formation and evolution of the Solar System (as well as other planetary systems). It suggests the Solar System is formed from gas and dust orbiting t ...

for the origin of the Solar System.

* Albrecht von Haller (1708–1777): Swiss anatomist, physiologist known as "the father of modern physiology". A Protestant, he was involved in the erection of the Reformed church in Göttingen, and, as a man interested in religious questions, he wrote apologetic letters which were compiled by his daughter under the name ''.''

*Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( , ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries in ma ...

(1707–1783): significant mathematician and physicist, see List of topics named after Leonhard Euler

200px, Leonhard Euler (1707–1783)

In mathematics and physics, many topics are named in honor of Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–1783), who made many important discoveries and innovations. Many of these items named after Euler includ ...

. The son of a pastor, he wrote ''Defense of the Divine Revelation against the Objections of the Freethinkers'' and is also commemorated by the Lutheran Church on their Calendar of Saints on May 24.

* Mikhail Lomonosov (1711–1765): Russian Orthodox Christian who discovered the atmosphere of Venus and formulated the law of conservation of mass in chemical reactions.

*Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

At The Deathbed of Darwinism

' (1904). * George Washington Carver (1864–1943): American

at UNC. * Jennifer Sinclair Curtis (born 1960): American engineer and the Dean of the University of California, Davis' College of Engineering from 2013 until 2020. She is credited with models of particulate flow that have been adopted extensively in commercial and open-source computational fluid dynamics software code. *John Dabiri (born 1980): Nigerian-American bioengineer and the Centennial Chair Professor at the California Institute of Technology, with appointments in the Graduate Aerospace Laboratories (GALCIT) and Mechanical Engineering. He is a MacArthur Fellow and one of Popular Science magazine's "Brilliant 10" scientists in 2008. * Steve Furber (born 1953): British computer scientist, mathematician and hardware engineer, currently the ICL Professor of Computer Engineering in the Department of Computer Science at the

Christians in Science website

Cambridge Christians in Science (CiS) group

Ian Ramsey Centre, Oxford

The Society of Ordained Scientists

Mostly

American Scientific Affiliation (ASA)

Canadian Scientific and Christian Affiliation (CSCA)

The Institute for the Study of Christianity in an Age of Science and Technology (ISCAST)

– Australia

The International Society for Science & Religion's founding members.(Of various faiths including Christianity)

Association of Christians in the Mathematical Sciences

Secular Humanism.org article on Science and Religion

{{DEFAULTSORT:List Of Christian Thinkers In Science Lists of Christian scientists, Christianity and science

CNRS (

conservation of mass

In physics and chemistry, the law of conservation of mass or principle of mass conservation states that for any system closed to all transfers of matter and energy, the mass of the system must remain constant over time, as the system's mass can ...

. He was a Catholic and defender of scripture.

*Herman Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave (, 31 December 1668 – 23 September 1738Underwood, E. Ashworth. "Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years." ''The British Medical Journal'' 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20395297.) was a Dutch botanist, ...

(1668–1789): remarkable Dutch physician and botanist known as the founder of clinical teaching. A collection of his religious thoughts on medicine, translated from Latin into English, has been compiled under the name ''Boerhaaveìs Orations''.

*John Michell

John Michell (; 25 December 1724 – 21 April 1793) was an English natural philosopher and clergyman who provided pioneering insights into a wide range of scientific fields including astronomy, geology, optics, and gravitation. Considered "o ...

(1724–1793): English clergyman who provided pioneering insights in a wide range of scientific fields, including astronomy, geology, optics, and gravitation.

*Maria Gaetana Agnesi

Maria Gaetana Agnesi ( , , ; 16 May 1718 – 9 January 1799) was an Italian mathematician, philosopher, theologian, and humanitarian. She was the first woman to write a mathematics handbook and the first woman appointed as a mathematics profe ...

(1718–1799): mathematician appointed to a position by Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758. Pope Be ...

. After her father died she devoted her life to religious studies, charity, and ultimately became a nun.

*Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

(1707–1778): Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, "father of modern taxonomy".

*Thomas Bayes

Thomas Bayes ( ; 1701 7 April 1761) was an English statistician, philosopher and Presbyterian minister who is known for formulating a specific case of the theorem that bears his name: Bayes' theorem. Bayes never published what would become his ...

(1701—1761): British statistician. Known for Baye's Theorem.

19th century (1801–1900)

*Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

(1733–1804): Nontrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essenc ...

clergyman who wrote the controversial work ''History of the Corruptions of Christianity.'' He is credited with discovering oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

.Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hyd ...

discovered oxygen earlier but published his findings after Priestley.

*John Playfair

John Playfair FRSE, FRS (10 March 1748 – 20 July 1819) was a Church of Scotland minister, remembered as a scientist and mathematician, and a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. He is best known for his book ''Illu ...

(1748–1819): Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

minister, scientist, mathematician, professor of natural philosophy. He was a co-founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and served as General Secretary to the society.

* Alessandro Volta (1745–1827): Italian physicist who invented the first electric battery. The unit Volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the unit of electric potential, electric potential difference (voltage), and electromotive force in the International System of Units (SI). It is named after the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745–1827).

Defin ...

was named after him.

* Samuel Vince (1749–1821): Cambridge astronomer and clergyman. He wrote ''Observations on the Theory of the Motion and Resistance of Fluids'' and ''The credibility of Christianity vindicated, in answer to Mr. Hume's objections.'' He won the Copley Medal in 1780, before the period dealt with here ended.

*Isaac Milner

Isaac Milner (11 January 1750 – 1 April 1820) was a mathematician, an inventor, the President of Queens' College, Cambridge and Lucasian Professor of Mathematics.

He was instrumental in the 1785 religious conversion of William Wilberforce a ...

(1750–1820): Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge University's Member of Pa ...

known for work on an important process to fabricate Nitrous acid

Nitrous acid (molecular formula ) is a weak and monoprotic acid known only in solution, in the gas phase and in the form of nitrite () salts. Nitrous acid is used to make diazonium salts from amines. The resulting diazonium salts are reagent ...

. He was also an evangelical Anglican who co-wrote ''Ecclesiastical History of the Church of Christ'' with his brother and played a role in the religious awakening of William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

. He also led to William Frend being expelled from Cambridge for a purported attack by Frend on the liturgy of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

.

* William Kirby (1759–1850): Parson-naturalist

A parson-naturalist was a cleric (a "parson", strictly defined as a country priest who held the living of a parish, but the term is generally extended to other clergy), who often saw the study of natural science as an extension of his religious wo ...

who wrote ''On the Power Wisdom and Goodness of God. As Manifested in the Creation of Animals and in Their History, Habits and Instincts'' and was a founding figure in British entomology. was an English chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, and meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists in research, while t ...

. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter ...

into chemistry. He was a Quaker Christian.

* John Dalton (1766–1844): an English chemist, physicist, and meteorologist. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory into chemistry, and for his research into colour blindness, sometimes referred to as Daltonism in his honour.

* Georges Cuvier (1769–1832): French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "father of paleontology".

*Thomas Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book '' An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Ma ...

(1766–1834): English cleric and scholar whose views on population caps were an influence on pioneers of evolutionary biology, including Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

and Alfred Russel Wallace.

* Andre Marie Ampere (1775–1836): one of the founders of classical electromagnetism

Classical electromagnetism or classical electrodynamics is a branch of theoretical physics that studies the interactions between electric charges and currents using an extension of the classical Newtonian model; It is, therefore, a classical fie ...

. The unit for electric current, Ampere, is named after him.

*Olinthus Gregory

Olinthus Gilbert Gregory (29 January 17742 February 1841) was an English mathematician, author, and editor.

Biography

He was born on 29 January 1774 at Yaxley in Huntingdonshire, the son of Robert, a shoemaker, and Ann, who also had three you ...

(1774–1841): wrote ''Lessons Astronomical and Philosophical'' in 1793 and became mathematical master at the Royal Military Academy in 1802. An abridgment of his 1815 ''Letters on the Evidences of Christianity'' was done by the Religious Tract Society

The Religious Tract Society was a British evangelical Christian organization founded in 1799 and known for publishing a variety of popular religious and quasi-religious texts in the 19th century. The society engaged in charity as well as commerci ...

.

* John Abercrombie (1780–1844): Scottish physician and Christian philosopher who created the a textbook about neuropathology

Neuropathology is the study of disease of nervous system tissue, usually in the form of either small surgical biopsies or whole-body autopsies. Neuropathologists usually work in a department of anatomic pathology, but work closely with the clini ...

.

* Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789–1857): French mathematician, engineer, and physicist who made pioneering contributions to several branches of mathematics, including mathematical analysis and continuum mechanics. He was a committed Catholic and member of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul

The Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP or SVdP or SSVP) is an international voluntary organization in the Catholic Church, founded in 1833 for the sanctification of its members by personal service of the poor.

Innumerable Catholic parishes have ...

. Cauchy lent his prestige and knowledge to the École Normale Écclésiastique, a school in Paris run by Jesuits, for training teachers for their colleges. He also took part in the founding of the Institut Catholique de Paris

The Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP), known in English as the Catholic University of Paris (and in Latin as ''Universitas catholica Parisiensis''), is a private university located in Paris, France.

History: 1875–present

The Institut Catholiq ...

. Cauchy had links to the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

and defended them at the academy when it was politically unwise to do so.

*William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

(1784–1856): Anglican priest/geologist who wrote ''Vindiciae Geologiae; or the Connexion of Geology with Religion explained.'' He was born in 1784, but his scientific life did not begin before the period discussed herein.

*Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for the discoveries she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel ...

(1799–1847): paleontologist who became known for discoveries of certain fossils in Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the Heri ...

, Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

. Anning was devoutly religious, and attended a Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

, then Anglican church.

* Marshall Hall (1790–1857): notable English physiologist who contributed with anatomical understanding and proposed a number of techniques in medical science. A Christian, his religious thoughts were collected in the biographical book ''Memoirs of Marshall Hall, by his widow'' (1861). He was also an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

who opposed slavery on religious grounds. He believed the institution of slavery was a sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

against God and denial of the Christian faith.

*John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow (6 February 1796 – 16 May 1861) was a British priest, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to his pupil Charles Darwin.

Early life

Henslow was born at Rochester, Kent, the son of a solicit ...

(1796–1861): British priest, botanist and geologist who was Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's tutor and enabled him to get a place on .

* Lars Levi Læstadius (1800–1861): botanist who started a revival movement within Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

called Laestadianism

Laestadianism, also known as Laestadian Lutheranism and Apostolic Lutheranism, is a pietistic Lutheran revival movement started in Sápmi in the middle of the 19th century. Named after Swedish Lutheran state church administrator and temperance ...

. This movement is among the strictest forms of Lutheranism. As a botanist he has the author citation ''Laest'' and discovered four species.

* Edward Hitchcock (1793–1864): geologist, paleontologist, and Congregationalist pastor. He worked on Natural theology and wrote on fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ized tracks.

*Benjamin Silliman

Benjamin Silliman (August 8, 1779 – November 24, 1864) was an early American chemist and science educator. He was one of the first American professors of science, at Yale College, the first person to use the process of fractional distillation ...

(1779–1864): chemist and science educator at Yale; the first person to distill petroleum, and a founder of the '' American Journal of Science'', the oldest scientific journal in the United States. An outspoken Christian, he was an old-earth creationist who openly rejected materialism.

* Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866): son of a pastor,As was Euler. Like Gauss, the Bernoullis would convince both sets of fathers and sons to study mathematics. he entered the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

at the age of 19, originally to study philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

and theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

in order to become a pastor and help with his family's finances. Upon the suggestion of Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gauß ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

, he switched to mathematics. He made lasting contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, and differential geometry, some of them enabling the later development of general relativity.

*William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved ...

(1794–1866): professor of mineralogy and moral philosophy. He wrote ''An Elementary Treatise on Mechanics'' in 1819 and ''Astronomy and General Physics considered with reference to Natural Theology'' in 1833. He is the wordsmith who coined the terms "scientist", "physicist", "anode", "cathode" and many other commonly used scientific words.

*Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

(1791–1867): Glasite

The Glasites or Glassites were a small Christian church founded in about 1730 in Scotland by John Glas.John Glas preached supremacy of God's word (Bible) over allegiance to Church and state to his congregation in Tealing near Dundee in July 172 ...

church elder for a time, he discussed the relationship of science to religion in a lecture opposing Spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (w ...

. He is known for his contributions in establishing electromagnetic theory and his work in chemistry such as establishing electrolysis.

* James David Forbes (1809–1868): physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and glaciologist

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or more generally ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, clima ...

who worked extensively on the conduction of heat and seismology

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

. He was a Christian as can be seen in the work ''"Life and Letters of James David Forbes"'' (1873).

* Charles Babbage (1791–1871): mathematician and analytical philosopher known as the first computer scientist who originated the idea of a programmable computer. He wrote the '' Ninth Bridgewater Treatise'', and the ''Passages from the Life of a Philosopher'' (1864) where he raised arguments to rationally defend the belief in miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

s.

* Adam Sedgwick (1785–1873): Anglican priest and geologist whose ''A Discourse on the Studies of the University'' discusses the relationship of God and man. In science he won both the Copley Medal and the Wollaston Medal

The Wollaston Medal is a scientific award for geology, the highest award granted by the Geological Society of London.

The medal is named after William Hyde Wollaston, and was first awarded in 1831. It was originally made of gold (1831–1845), ...

. His students included Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

.

*John Bachman

John Bachman (February 4, 1790 – February 24, 1874) was an American Lutheran minister, social activist and naturalist who collaborated with John James Audubon to produce ''Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America'' and whose writings, particul ...

(1790–1874): wrote numerous scientific articles and named several species of animals. He also was a founder of the Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary and wrote works on Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

.

*Temple Chevallier

Temple Chevallier FRAS (19 October 1794 in Badingham, Suffolk – 4 November 1873 in Harrow Weald) was a British clergyman, astronomer, and mathematician. Between 1847 and 1849, he made important observations regarding sunspots. Chevall ...

(1794–1873): priest and astronomer who did ''Of the proofs of the divine power and wisdom derived from the study of astronomy''. He also founded the Durham University Observatory

The Durham University Observatory is a weather observatory owned and operated by the University of Durham. It is a Grade II listed building located at Potters Bank, Durham and was founded in 1839 initially as an astronomical and meteorological ...

, hence the Durham Shield is pictured.

* Robert Main (1808–1878): Anglican priest who won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awar ...

in 1858. Robert Main also preached at the British Association of Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

.

*James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

(1831–1879): Although Clerk as a boy was taken to Presbyterian services by his father and to Anglican services by his aunt, while still a young student at Cambridge he underwent an Evangelical conversion that he described as having given him a new perception of the Love of God.In the biography by Cambell (p. 170) Maxwell's conversion is described: "He referred to it long afterwards as having given him a new perception of the Love of God. One of his strongest convictions thenceforward was that 'Love abideth, though Knowledge vanish away.'" Maxwell's evangelicalism "committed him to an anti- positivist position." He is known for his contributions in establishing electromagnetic theory (Maxwell's Equations) and work on the chemical kinetic theory of gases.

*James Bovell

James Bovell (1817–1880) was a prominent Canadian physician, microscopist, educator, theologian and minister.

In his youth, he traveled to London to study medicine at Guy's Hospital. There, he was related to Sir Astley Cooper and had Richar ...

(1817–1880): Canadian physician and microscopist who was member of Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

. He was the mentor of William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of phys ...

, as well as an Anglican minister and religious author who wrote about natural theology.

* Andrew Pritchard (1804–1882): English naturalist and natural history dealer who made significant improvements to microscopy and wrote the standard work on aquatic micro-organisms. He devoted much energy to the chapel he attended, Newington Green Unitarian Church

Newington Green Unitarian Church (NGUC) in north London is one of England's oldest Unitarian churches. It has had strong ties to political radicalism for over 300 years, and is London's oldest Nonconformist place of worship still in use. It wa ...

.

*Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

(1822–1884): Augustinian Abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

who was the "father of modern genetics" for his study of the inheritance of traits in pea plants. He preached sermons at Church, one of which deals with how Easter represents Christ's victory over death.

*Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequ ...

(1832–1898): eal name: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson English writer, mathematician, and Anglican deacon. Robbins' and Rumsey's investigation of Dodgson's method

Dodgson's method is an electoral system proposed by the author, mathematician and logician Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis ...

, a method of evaluating determinants, led them to the Alternating Sign Matrix conjecture, now a theorem.

*Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz ( ; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. The unit ...

(1857–1894): German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves.

*Philip Henry Gosse

Philip Henry Gosse FRS (; 6 April 1810 – 23 August 1888), known to his friends as Henry, was an English naturalist and populariser of natural science, an early improver of the seawater aquarium, and a painstaking innovator in the study of ma ...

(1810–1888): marine biologist who wrote ''Aquarium'' (1854), and ''A Manual of Marine Zoology'' (1855–56). He is more notable as a Christian Fundamentalist who coined the idea of Omphalos (theology).

* Asa Gray (1810–1888): His ''Gray's Manual'' remains a pivotal work in botany. His ''Darwiniana

''Darwiniana: Essays and Reviews Pertaining to Darwinism'' is a collection of essays by botanist Asa Gray, first published in 1876. These widely read essays both defended the theory of evolution from the standpoint of botany and sought reconciliat ...

'' has sections titled "Natural selection not inconsistent with Natural theology", "Evolution and theology", and "Evolutionary teleology." The preface indicates his adherence to the Nicene Creed in concerning these religious issues.

*Julian Tenison Woods

Julian Edmund Tenison-Woods (15 November 18327 October 1889), commonly referred to as Father Woods, was an English Catholic priest and geologist who served in Australia.D. H. BorchardtTenison-Woods, Julian Edmund (1832–1889) '' Australian Di ...

(1832–1889): co-founder of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart

The Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, often called the Josephites or Brown Joeys, are a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Mary MacKillop (1842–1909). Members of the congregation use the postnominal initials RSJ (Religious Siste ...

who won a Clarke Medal

The Clarke Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of New South Wales, the oldest learned society in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere, for distinguished work in the Natural sciences.

The medal is named in honour of the Reverend William Branw ...

shortly before death. A picture from Waverley Cemetery

The Waverley Cemetery is a heritage-listed cemetery on top of the cliffs at Bronte in the eastern suburbs of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Opened in 1877 and built by R. Watkins (cemetery lodge, 1878) and P. Beddie (cemetery office, 1915), ...

, where he's buried, is shown.

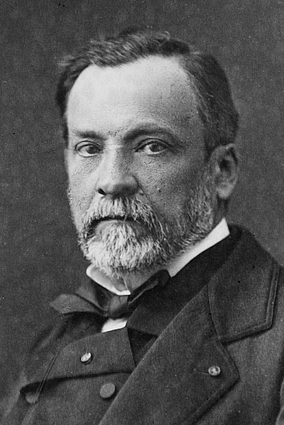

* Louis Pasteur (1822–1895): French biologist, microbiologist and chemist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization.

*James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcanic activity, and the origin and structure of continent ...

(1813–1895): geologist, mineralogist, and zoologist. He received the Copley Medal, Wollaston Medal

The Wollaston Medal is a scientific award for geology, the highest award granted by the Geological Society of London.

The medal is named after William Hyde Wollaston, and was first awarded in 1831. It was originally made of gold (1831–1845), ...

, and the Clarke Medal

The Clarke Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of New South Wales, the oldest learned society in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere, for distinguished work in the Natural sciences.

The medal is named in honour of the Reverend William Branw ...

. He also wrote a book titled ''Science and the Bible'' and his faith has been described as "both orthodox and intense".

*James Prescott Joule

James Prescott Joule (; 24 December 1818 11 October 1889) was an English physicist, mathematician and brewer, born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work (see energy). ...

(1818–1889): studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work. This led to the law of conservation of energy, which led to the development of the first law of thermodynamics. The SI derived unit of energy, the joule, is named after James Joule.

*John William Dawson

Sir John William Dawson (1820–1899) was a Canadian geologist and university administrator.

Life and work

John William Dawson was born on 13 October 1820 in Pictou, Nova Scotia, where he attended and graduated from Pictou Academy. Of Scotti ...

(1820–1899): Canadian geologist who was the first president of the Royal Society of Canada and served as president of both the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. A presbyterian, he spoke against Darwin's theory and came to write ''The Origin of the World, According to Revelation and Science'' (1877) where he put together his theological and scientific views.

* Armand David (1826–1900): Catholic missionary to China and member of the Lazarists

, logo =

, image = Vincentians.png

, abbreviation = CM

, nickname = Vincentians, Paules, Lazarites, Lazarists, Lazarians

, established =

, founder = Vincent de Paul

, fou ...

who considered his religious duties to be his principal concern. He was also a botanist with the author abbreviation ''David'' and as a zoologist he described several species new to the West.

* Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

(1827–1912): British surgeon and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery. He raised as a Quaker, he subsequently left the Quakers, joined the Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

.

20th century (1901–2000)

According to ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' a review ofNobel prizes

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfre ...

award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

in its various forms as their religious preference.Baruch A. Shalev, ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' (2003), Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, p.57:

between 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religion Most (65.4%) have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference. Overall, 72.5% of all the Nobel Prizes in Chemistry,Shalev, Baruch (2005). 100 Years of Nobel Prizes. p. 59 65.3% in Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, 62% in Medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, 54% in Economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes ...

were either Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

or had a Christian background.

*John Hall Gladstone

John Hall Gladstone FRS (7 March 1827 – 6 October 1902) was a British chemist.* He served as President of the Physical Society between 1874 and 1876 and during 1877–1879 was President of the Chemical Society. Apart from chemistry, where ...

(1827–1902): served as president of the Physical Society between 1874 and 1876 and during 1877–1879 was president of the Chemical Society

The Chemical Society was a scientific society formed in 1841 (then named the Chemical Society of London) by 77 scientists as a result of increased interest in scientific matters. Chemist Robert Warington was the driving force behind its creation.

...

. He also belonged to the Christian Evidence Society.

* George Stokes (1819–1903): minister's son, he wrote a book on Natural Theology. He was also one of the Presidents of the Royal Society

The president of the Royal Society (PRS) is the elected Head of the Royal Society of London who presides over meetings of the society's council.

After informal meetings at Gresham College, the Royal Society was officially founded on 28 November ...

and made contributions to Fluid dynamics.

*Henry Baker Tristram

Henry Baker Tristram FRS (11 May 1822 – 8 March 1906) was an English clergyman, Bible scholar, traveller and ornithologist. As a parson-naturalist he was an early supporter of Darwinism, attempting to reconcile evolution and creation.

Biogra ...

(1822–1906): founding member of the British Ornithologists' Union. His publications included ''The Natural History of the Bible'' (1867) and ''The Fauna and Flora of Palestine'' (1884).

* Enoch Fitch Burr (1818–1907): astronomer and Congregational Church pastor who lectured extensively on the relationship between science and religion. He also wrote ''Ecce Coelum: or Parish Astronomy'' in 1867. He once stated that "an undevout astronomer is mad" and held a strong belief in extraterrestrial life.

*Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

(1824–1907): At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws of th ...

. He gave a famous address to the Christian Evidence Society. In science he won the Copley Medal and the Royal Medal.

* William Dallinger (1839–1909): British minister in the Wesleyan Methodist Church and an accomplished scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosoph ...

who studied the complete lifecycle of unicellular organism

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms a ...

s under the microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

.

*Emil Theodor Kocher

Emil Theodor Kocher (25 August 1841 – 27 July 1917) was a Swiss physician and medical researcher who received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid. Among his many a ...

(1841–1917): Swiss physician and medical researcher who received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

for his work in the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid

The thyroid, or thyroid gland, is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans it is in the neck and consists of two connected lobes. The lower two thirds of the lobes are connected by a thin band of tissue called the thyroid isthmus. The thy ...

. Kocher was a deeply religious man and also part of the Moravian Church

, image = AgnusDeiWindow.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, caption = Church emblem featuring the Agnus Dei.Stained glass at the Rights Chapel of Trinity Moravian Church, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States

, main_classification = Proto-Prot ...

, Kocher attributed all his successes and failures to God.

*John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, (; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919) was an English mathematician and physicist who made extensive contributions to science. He spent all of his academic career at the University of Cambridge. Amo ...

(1842-1919): English mathematician and physicist, author of several theories and discoveries in the fields of electrodynamics, fluid dynamics and optics, including Rayleigh scattering

Rayleigh scattering ( ), named after the 19th-century British physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt), is the predominantly elastic scattering of light or other electromagnetic radiation by particles much smaller than the wavelength of th ...

which explains why sky is blue. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library syst ...

. He belonged to Anglican denomination.

*Georg Cantor

Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor ( , ; – January 6, 1918) was a German mathematician. He played a pivotal role in the creation of set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor established the importance of ...

(1845–1918): German mathematician who created the theory of transfinite numbers

In mathematics, transfinite numbers are numbers that are "infinite" in the sense that they are larger than all finite numbers, yet not necessarily absolutely infinite. These include the transfinite cardinals, which are cardinal numbers used to qu ...

and set theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematical logic that studies sets, which can be informally described as collections of objects. Although objects of any kind can be collected into a set, set theory, as a branch of mathematics, is mostly conce ...

, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. He was a devout Lutheran whose explicit Christian beliefs shaped his philosophy of science. Joseph Dauben

Joseph Warren Dauben (born 29 December 1944, Santa Monica) is a Herbert H. Lehman Distinguished Professor of History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He obtained his PhD from Harvard University.

His fields of expertise ...

has traced the impact Cantor's Christian convictions had on the development of transfinite set theory.

*J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be discovered.

In 1897, Thomson showed that ...

(1856–1940): English physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery and identification of the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

; and with the discovery of the first subatomic particle. He was an Anglican.

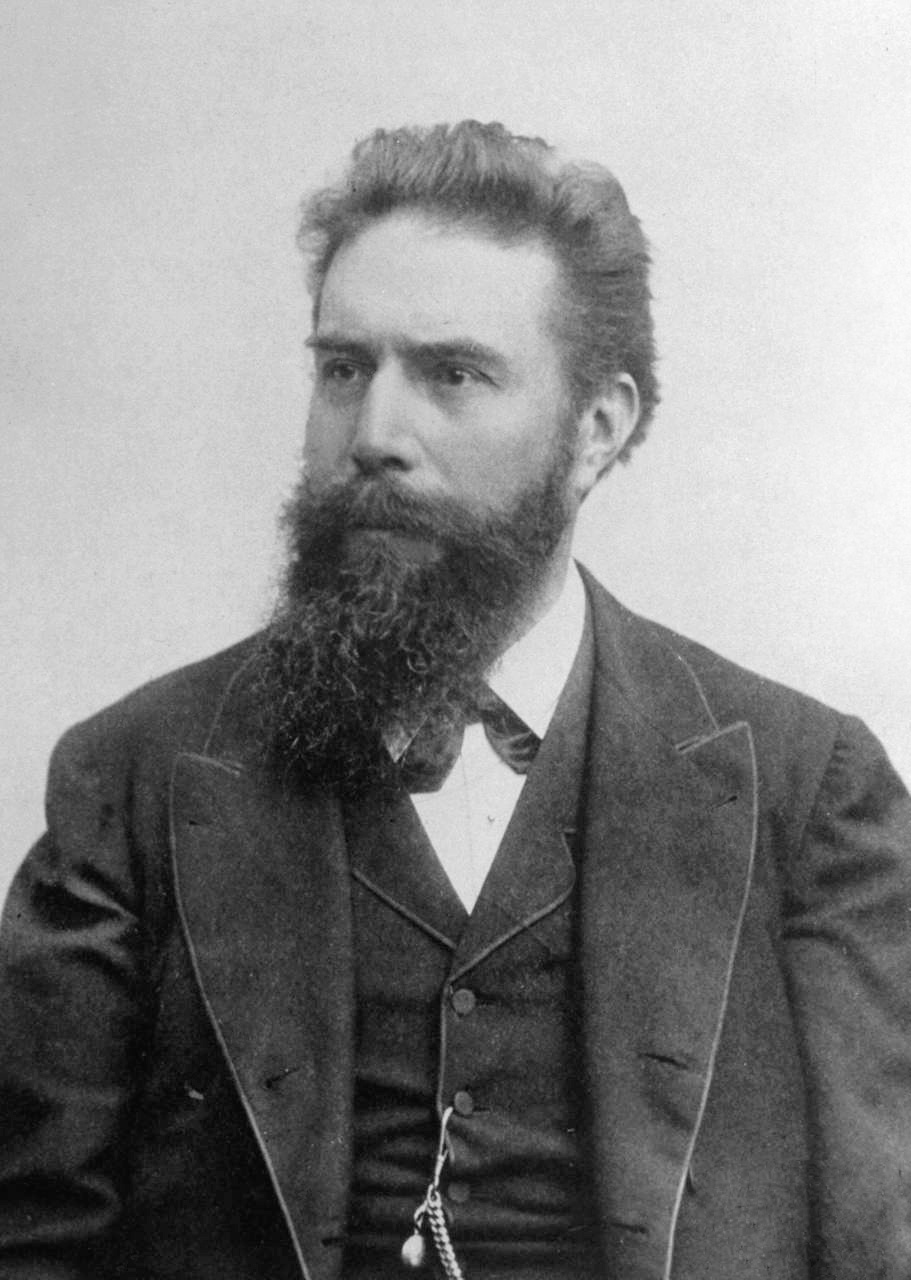

*Wilhelm Röntgen

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (; ; 27 March 184510 February 1923) was a German mechanical engineer and physicist, who, on 8 November 1895, produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays or Röntgen rays, an achie ...

(1845–1923): German engineer and physicist, who, on 8 November 1895, produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays or Röntgen rays, an achievement that earned him the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901

*Giuseppe Mercalli

Giuseppe Mercalli (21 May 1850 – 19 March 1914) was an Italian volcanologist and Catholic priest. He is known best for the Mercalli intensity scale for measuring earthquake intensity.

Biography

Born in Milan, Mercalli was ordained a Roman C ...

(1850–1914): Italian volcanologist and Catholic priest. He is best remembered for the Mercalli intensity scale for measuring earthquakes.

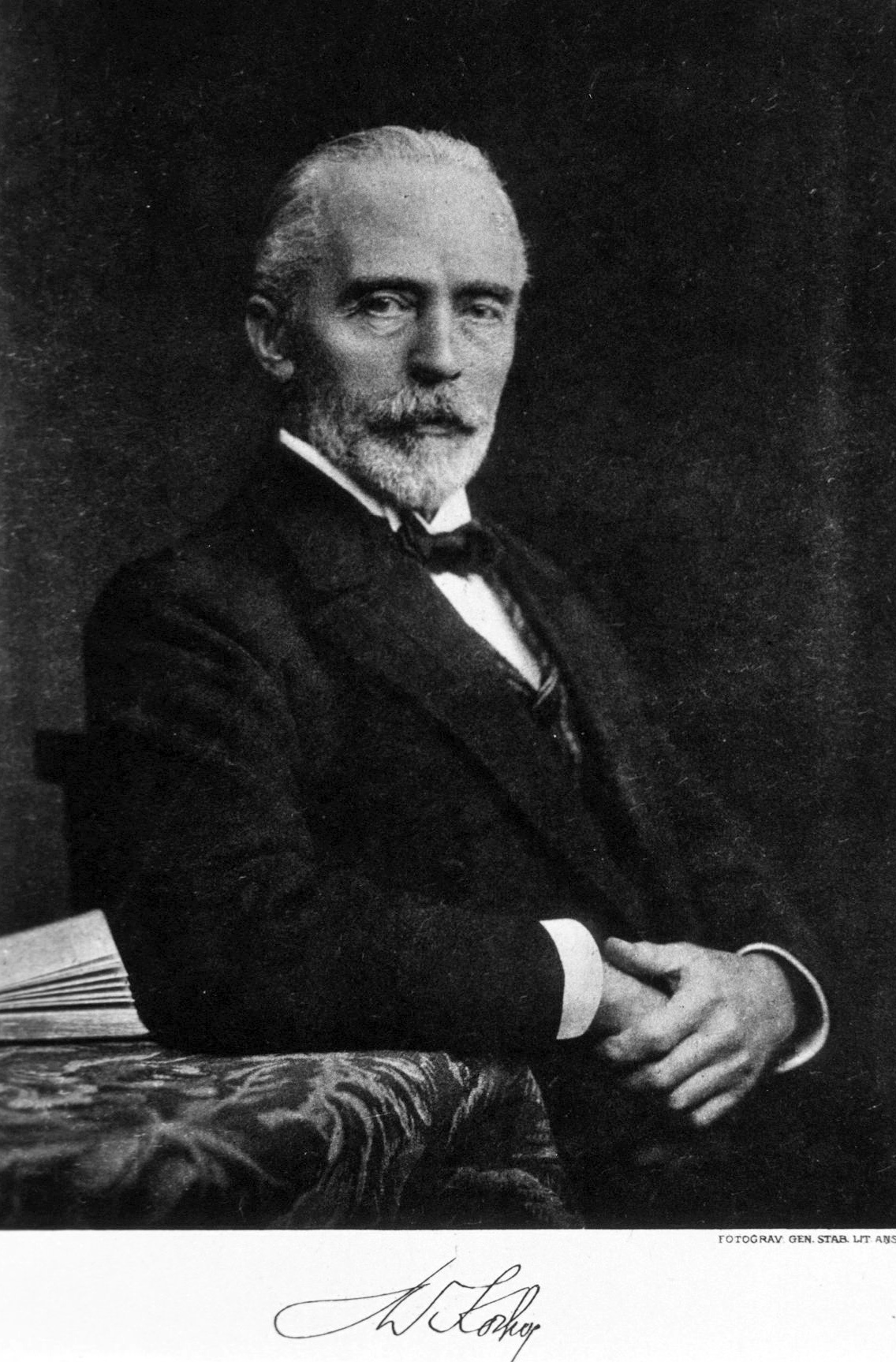

*Pierre Duhem

Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem (; 9 June 1861 – 14 September 1916) was a French theoretical physicist who worked on thermodynamics, hydrodynamics, and the theory of elasticity. Duhem was also a historian of science, noted for his work on the Eu ...

(1861–1916): worked on Thermodynamic potentials

A thermodynamic potential (or more accurately, a thermodynamic potential energy)ISO/IEC 80000-5, Quantities an units, Part 5 - Thermodynamics, item 5-20.4 Helmholtz energy, Helmholtz functionISO/IEC 80000-5, Quantities an units, Part 5 - Thermod ...

and wrote histories advocating that the Roman Catholic Church helped advance science.

*James Britten

James Britten (3 May 1846 – 8 October 1924) was an English botanist.

Biography

Born in Chelsea, London, he moved to High Wycombe in 1865 to begin a medical career. However he became increasingly interested in botany, and began writing papers ...

(1846–1924): botanist who was heavily involved in the Catholic Truth Society

Catholic Truth Society (CTS) is a body that prints and publishes Catholic literature, including apologetics, prayerbooks, spiritual reading, and lives of saints. It is based in London, the United Kingdom.

The CTS had been founded in 1868 by ...

.

*Charles Doolittle Walcott

Charles Doolittle Walcott (March 31, 1850February 9, 1927) was an American paleontologist, administrator of the Smithsonian Institution from 1907 to 1927, and director of the United States Geological Survey. Wonderful Life (book) by Stephen Jay G ...

(1850–1927): paleontologist, most notable for his discovery of the Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fo ...

of British Columbia. Stephen Jay Gould said that Walcott, "discoverer of the Burgess Shale fossils, was a convinced Darwinian and an equally firm Christian, who believed that God had ordained natural selection to construct a history of life according to His plans and purposes."

*Johannes Reinke

Johannes Reinke (February 3, 1849 – February 25, 1931) was a German botanist and philosopher who was a native of Ziethen, Lauenburg. He is remembered for his research of benthic marine algae.

Academic background

Reinke studied botany with h ...

(1849–1931): German phycologist and naturalist who founded the ''German Botanical Society''. An opposer of Darwinism and the secularization of science, he wrote ''Kritik der Abstammungslehre'' (Critique of the theory of evolution), (1920), and ''Naturwissenschaft, Weltanschauung, Religion'', (Science, philosophy, religion), (1923). He was a Lutheran.

* Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937): Italian inventor and electrical engineer known for his pioneering work on long-distance radio transmission and for his development of Marconi's law and a radio telegraph system. He shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics.

* Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and phil ...

(1881–1955): French Jesuit paleontologist, co-discoverer of the Peking Man

Peking Man (''Homo erectus pekinensis'') is a subspecies of '' H. erectus'' which inhabited the Zhoukoudian Cave of northern China during the Middle Pleistocene. The first fossil, a tooth, was discovered in 1921, and the Zhoukoudian Cave has s ...

, noted for his work on evolutionary theory and Christianity. He postulated the Omega Point as the end-goal of Evolution and he is widely regarded as one of the most important Catholic theologians of the 20th century.

*William Williams Keen