Lewis Henry Morgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American

After graduating in 1840, Morgan returned to Aurora to read the law with an established firm. In 1842 he was admitted to the bar in Rochester, where he went into partnership with a Union classmate, George F. Danforth, a future judge. They could find no clients, as the nation was in an economic depression, which had started with the

After graduating in 1840, Morgan returned to Aurora to read the law with an established firm. In 1842 he was admitted to the bar in Rochester, where he went into partnership with a Union classmate, George F. Danforth, a future judge. They could find no clients, as the nation was in an economic depression, which had started with the

Morgan and his colleagues invited Parker to join the New Confederacy. They (chiefly Morgan) paid for the rest of Parker's education at the Cayuga Academy, along with his sister and a friend of hers. Later the Confederacy paid for Parker's studies at

Morgan and his colleagues invited Parker to join the New Confederacy. They (chiefly Morgan) paid for the rest of Parker's education at the Cayuga Academy, along with his sister and a friend of hers. Later the Confederacy paid for Parker's studies at

After Morgan was admitted to the tribe, he lost interest in the New Confederacy. The group retained its secrecy and initiation requirements, but they were being hotly disputed. When internal dissent began to impede the group's efficacy in 1847, Morgan stopped attending. For practical purposes it ceased to exist, but Morgan and Parker continued with a series of "Iroquois Letters" to the '' American Whig Review'', edited by George Colton. The Seneca case dragged on. Finally in 1857 the

After Morgan was admitted to the tribe, he lost interest in the New Confederacy. The group retained its secrecy and initiation requirements, but they were being hotly disputed. When internal dissent began to impede the group's efficacy in 1847, Morgan stopped attending. For practical purposes it ceased to exist, but Morgan and Parker continued with a series of "Iroquois Letters" to the '' American Whig Review'', edited by George Colton. The Seneca case dragged on. Finally in 1857 the

anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

and social theorist who worked as a railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

and social structure, his theories of social evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, and his ethnography

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

. Interested in what holds societies together, he proposed the concept that the earliest human domestic institution was the matrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

, not the patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of authority are primarily held by men. The term ''patriarchy'' is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in fem ...

family.

Also interested in what leads to social change, he was a contemporary of the European social theorists Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Charles Darwin Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, and ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Charles Darwin Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

. Elected as a member of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

, Morgan served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

in 1880.

Morgan was a Republican member of the New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Ass ...

(Monroe Co., 2nd D.) in 1861, and of the New York State Senate

The New York State Senate is the upper house of the New York State Legislature, while the New York State Assembly is its lower house. Established in 1777 by the Constitution of New York, its members are elected to two-year terms with no term l ...

in 1868 and 1869

Events January

* January 3 – Abdur Rahman Khan is defeated at Tinah Khan, and exiled from Afghanistan.

* January 5 – Scotland's second oldest professional football team, Kilmarnock F.C., is founded.

* January 20 – Elizabe ...

.

Biography

The American Morgans

According to Herbert Marshall Lloyd, an attorney and editor of Morgan's works, Lewis was descended from James Morgan, a Welsh pioneer. Various sources record that James and his brothers, Miles and John, the three sons of William Morgan ofLlandaff

Llandaff (; ; from 'church' and ''River Taff, Taf'') is a district, Community (Wales), community and coterminous electoral ward in the north of Cardiff, capital of Wales. It was incorporated into the city in 1922. It is the seat of the Bisho ...

, Glamorganshire, left Wales for Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

in 1636. From there John Morgan went to Virginia, Miles to Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is the most populous city in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States, and its county seat. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ea ...

, and James to New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

. Lloyd writes, "From these two brothers ames and Milesall the Morgans prominent in the annals of New York and New England are believed to be descended." It is these Morgans who played a critical part in the foundation of the colonies. During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, they were Continentals. Immediately after the war, James's line, along with many other land-hungry Yankees, migrated into New York State

New York, also called New York State, is a state in the northeastern United States. Bordered by New England to the east, Canada to the north, and Pennsylvania and New Jersey to the south, its territory extends into both the Atlantic Ocean and ...

. Following the United States' victory against the British, the new government forced the latter's Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

allies to cede most of their traditional lands in New York and Pennsylvania to the US. New York made 5 million acres available for public sale. In addition, the US government granted some plots in western New York to Revolutionary War veterans as compensation for their military service. L. H. Morgan's ancestor James Morgan's brother Miles Morgan was a seventh generation ancestor of J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As the head of the banking firm that ...

.

Early life and education

Lewis' grandfather, Thomas Morgan of Connecticut, had been a Continental soldier in the Revolutionary War. Afterward he and his family migrated west to New York'sFinger Lakes

The Finger Lakes are a group of eleven long, narrow, roughly north–south lakes located directly south of Lake Ontario in an area called the ''Finger Lakes region'' in New York (state), New York, in the United States. This region straddles th ...

region, where he bought land from the Cayuga people

The Cayuga ( Cayuga: Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ, "People of the Great Swamp") are one of the five original constituents of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), a confederacy of Native Americans in New York. The Cayuga homeland lies in the Finger Lakes re ...

and planted a farm on the shores of Lake Cayuga near Aurora

An aurora ( aurorae or auroras),

also commonly known as the northern lights (aurora borealis) or southern lights (aurora australis), is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly observed in high-latitude regions (around the Arc ...

. He and his wife already had three sons, including Jedediah, the future father of Lewis; and a daughter.

In 1797, Jedediah Morgan (1774–1826) married Amanda Stanton, settling on a 100-acre gift of land from his father. After she had five children and died, Jedediah married Harriet Steele of Hartford, Connecticut. They had eight more children, including Lewis. As an adult, he adopted the middle initial "H." Morgan later decided that this H, if anything, stood for "Henry".

A multi-skilled Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Their various meanings depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, the Northeastern United Stat ...

, Jedediah Morgan invented a plow and formed a business partnership to manufacture parts for it; he built a blast furnace for the factory. He moved to Aurora, leaving the farm to a son. After joining the Masons, he helped to form the first Masonic lodge in Aurora. Elected a state senator, Morgan supported the construction of the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east–west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigability, navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, ...

, which opened in 1825.

At his death in 1826, Jedediah left 500 acres with herds and flocks in trust for the support of his family. This provided for education as well. Morgan studied classical subjects at Cayuga Academy: Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

and mathematics. His father had bequeathed money specifically for his college education, after giving land to the other children for their occupations. Morgan chose Union College

Union College is a Private university, private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York, United States. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the s ...

in Schenectady. Due to his work at Cayuga Academy, Morgan finished college in two years, 1838–1840, graduating at age 22. The curriculum continued study of classics combined with science, especially mechanics and optics. Morgan was strongly interested in the works of the French naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

.

Eliphalet Nott, the president of Union College, was an inventor of stoves and a boiler; he held 31 patents. A Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

minister, he kept the young men under a tight discipline, forbidding alcoholic beverages and requiring students to get permission to go to town. He held up the Bible as the one practical standard for all behavior. His career ended with some notoriety when he was investigated by the state for attempting to raise funds for the college through a lottery. The students evaded his strict regime by founding secret (and forbidden) fraternities

A fraternity (; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men but also women associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity in the Western conce ...

, such as the Kappa Alpha Society

The Kappa Alpha Society () is a North American social college fraternity. Founded in 1825, it was the progenitor of the modern fraternity system in North America. It is considered to be the oldest national, secret, Greek-letter social fraterni ...

. Lewis Morgan joined in 1839.

The New Confederacy of the Iroquois

After graduating in 1840, Morgan returned to Aurora to read the law with an established firm. In 1842 he was admitted to the bar in Rochester, where he went into partnership with a Union classmate, George F. Danforth, a future judge. They could find no clients, as the nation was in an economic depression, which had started with the

After graduating in 1840, Morgan returned to Aurora to read the law with an established firm. In 1842 he was admitted to the bar in Rochester, where he went into partnership with a Union classmate, George F. Danforth, a future judge. They could find no clients, as the nation was in an economic depression, which had started with the Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

. Morgan wrote essays, which he had begun to do while studying law, and published some in '' The Knickerbocker'' under the pen name Aquarius.

On January 1, 1841, Morgan and some friends from Cayuga Academy formed a secret fraternal society which they called the Gordian Knot

The cutting of the Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend associated with Alexander the Great in Gordium in Phrygia, regarding a complex knot that tied an oxcart. Reputedly, whoever could untie it would be destined to rule all of Asia. In 33 ...

. As Morgan's earliest essays from that time had classical themes, the club may have been a kind of literary society, as was common then. In 1841 or 1842 the young men redefined the society, renaming it the Order of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

. Morgan referred to this event as cutting the knot. In 1843 they named it the Grand Order of the Iroquois, followed by the New Confederacy of the Iroquois. They made the group a research organization to collect information on the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

, whose historical territory for centuries had included central and upstate New York west of the Hudson and the Finger Lakes region.

The men intended to resurrect the spirit of the Iroquois. They tried to learn the languages, assumed Iroquois names, and organized the group by the historic pattern of Iroquois tribes. In 1844 they received permission from the former Freemasons of Aurora to use the upper floor of the Masonic temple as a meeting hall. New members underwent a secret rite called ''inindianation'' in which they were transformed spiritually into Iroquois. They met in the summer around campfires and paraded yearly through the town in costume. Morgan seemed infused with the spirit of the Iroquois. He said, "We are now upon the very soil over which they exercised dominion ... Poetry still lingers around the scenery. ... " These new Iroquois retained a literary frame of mind, but they intended to focus on "the writing of a native American epic that would define national identity".

Encounter with the Iroquois

On an 1844 business trip to New York's capital, Albany, Morgan started research on old Cayuga treaties in the state archives. TheSeneca people

The Seneca ( ; ) are a group of Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their nation was the farthest to the west within the Six Nations or Iroquois Leag ...

were also studying old US-Native American treaties to support their land claims.

After the Revolutionary War, the United States had forced the four Iroquois tribes allied with the British to cede their lands and migrate to Canada. By specific treaties, the US set aside small reservations in New York for their own allies, the Onondaga and Seneca. In the 1840s, long after the war, the Ogden Land Company, a real estate venture, laid claim to the Seneca Tonawanda Reservation on the basis of a fraudulent treaty. The Seneca sued and had representatives at the state capital pressing their case when Morgan was there.

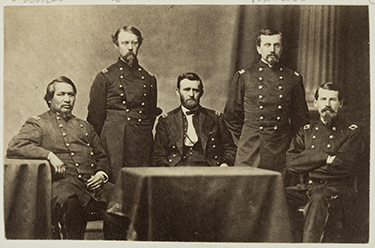

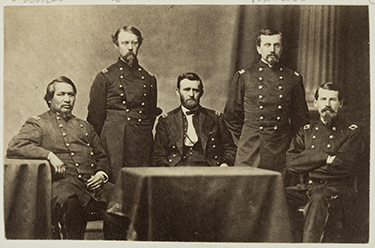

The delegation, led by Jimmy Johnson, its chief officer (and son of chief Red Jacket), were essentially former officers of what was left of the Iroquois Confederacy. Johnson's 16-year-old grandson ''Ha-sa-ne-an-da'' ( Ely Parker) accompanied them as their interpreter, as he had attended a mission school and was bilingual. By chance Morgan and the young Parker encountered each other in an Albany book store. Soon intrigued by Morgan's talk of the New Confederacy, Parker invited the older man to interview Johnson and meet the delegation. Morgan took pages of organizational notes, which he used to remodel the New Confederacy. Beyond such details of scholarship, Morgan and the Seneca men formed deep attachments of friendship.

Morgan and his colleagues invited Parker to join the New Confederacy. They (chiefly Morgan) paid for the rest of Parker's education at the Cayuga Academy, along with his sister and a friend of hers. Later the Confederacy paid for Parker's studies at

Morgan and his colleagues invited Parker to join the New Confederacy. They (chiefly Morgan) paid for the rest of Parker's education at the Cayuga Academy, along with his sister and a friend of hers. Later the Confederacy paid for Parker's studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (; RPI) is a private university, private research university in Troy, New York, United States. It is the oldest technological university in the English-speaking world and the Western Hemisphere. It was establishe ...

in Troy, New York

Troy is a city in and the county seat of Rensselaer County, New York, United States. It is located on the western edge of the county, on the eastern bank of the Hudson River just northeast of the capital city of Albany, New York, Albany. At the ...

, where he graduated in civil engineering

Civil engineering is a regulation and licensure in engineering, professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads ...

. After military service in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, from which Parker retired at the rank of brigadier general, he entered the upper ranks of civil service in the presidency of his former commander, Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

.

The Ogden Land Company affair

Meanwhile, the organization had had activist goals from the beginning. In his initial New Gordius address Morgan had said:... when the last tribe shall slumber in the grass, it is to be feared that the stain of blood will be found on the escutcheon of the American republic. This nation must shield their declining day ...In 1838 the Ogden Land Company began a campaign to defraud the remaining Iroquois in New York of their lands. By Iroquois law, only a unanimous vote of all the chiefs sitting in council could effect binding decisions relating to the tribe. The OLC set about to purchase the votes of as many chiefs as it could, plying some with alcohol. The chiefs in many cases complied, believing any resolutions to sell the land would be defeated in council. Obtaining a majority vote for sale at one council called for the purpose, the OLC took their treaty to the Congress of the United States, which knew nothing of Iroquois law. President

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

advised Congress that the treaty was fraudulent but on June 11, 1838, Congress adopted it as a resolution. After being compensated for their land by $1.67 per acre (Morgan said it was worth $16 per acre), the Seneca were to be evicted forthwith.

The great majority of the tribe were against the sale of the land. When they discovered they had been defrauded, they were galvanized to action. The New Confederacy stepped into the case on the side of the Seneca, conducting a major publicity campaign. They held mass meetings, circulated a general petition, and spoke to congressmen in Washington. The US Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the U.S. government.

Agents established in Nonintercourse Act of 1793

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the Un ...

and ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft and other influential men became honorary members. In 1846 a general convention of the population of Genesee County, New York

Genesee County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 58,388. Its county seat is Batavia. Its name is from the Seneca word Gen-nis'-hee-yo, meaning "the Beautiful Valley".THE AMERICAN REVIEW; ...

sent Morgan to Congress with a counter-offer. The Seneca were allowed to buy back some land at $20 per acre, at which time the Tonawanda Reservation was created. The previous treaty was thrown out. Returning home, Morgan was adopted into the Hawk Clan, Seneca Tribe, as the son of Jimmy Johnson on October 31, 1847, in part to honor his work with the Seneca on the reservation issues. They named him ''Tayadaowuhkuh'', meaning "bridging the gap" (between the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

and the European Americans).

After Morgan was admitted to the tribe, he lost interest in the New Confederacy. The group retained its secrecy and initiation requirements, but they were being hotly disputed. When internal dissent began to impede the group's efficacy in 1847, Morgan stopped attending. For practical purposes it ceased to exist, but Morgan and Parker continued with a series of "Iroquois Letters" to the '' American Whig Review'', edited by George Colton. The Seneca case dragged on. Finally in 1857 the

After Morgan was admitted to the tribe, he lost interest in the New Confederacy. The group retained its secrecy and initiation requirements, but they were being hotly disputed. When internal dissent began to impede the group's efficacy in 1847, Morgan stopped attending. For practical purposes it ceased to exist, but Morgan and Parker continued with a series of "Iroquois Letters" to the '' American Whig Review'', edited by George Colton. The Seneca case dragged on. Finally in 1857 the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

affirmed that only the federal government could evict the Seneca from their land. As it declined to do that, the case was over. The Ogden Land Company collapsed.

Marriage and family

In 1851 Morgan summarized his investigation of Iroquois customs in his first book of note, '' League of the Iroquois'', one of the founding works of ethnology. In it he compares systems ofkinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

. In that year also he married his cross-cousin, Mary Elizabeth Steele, his companion and partner for the rest of his life. She had intended to become a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

. On their wedding day he presented to her an ornate copy of his new book. It was dedicated to his collaborator, Ely Parker.

In 1853 Mary's father died, leaving her a large inheritance. The Morgans bought a brownstone

Brownstone is a brown Triassic–Jurassic sandstone that was historically a popular building material. The term is also used in the United States and Canada to refer to a townhouse clad in this or any other aesthetically similar material.

Ty ...

in a wealthy suburb of Rochester. In that year they had a son, Lemuel, who "turned out to be mentally handicapped". Morgan's rising fame had brought him public attention, and Lemuel's condition (on no specific evidence) was universally attributed to the first-cousin marriage. The Morgans had to endure perpetual criticism, which they accepted as true, Lewis going so far as to take a stand against cousin marriage in his book ''Ancient Society''. The Morgan marriage nevertheless remained a close and affectionate one. In 1856, Mary Elisabeth was born and in 1860 Helen King.

Morgan and his wife were active in the First Presbyterian Church of Rochester, although it was mainly of interest to Mary. Lewis refused to make "the public profession of Christ that was necessary for full membership". They both sponsored and contributed to charitable works.

Supporting education

For several years "his ethnical interests lay dormant", but not his scholarship and writing. In 1852 Morgan and eight other "Rochester intellectuals" instituted ThePundit

A pundit is a person who offers opinion in an authoritative manner on a particular subject area (typically politics, the social sciences, technology or sport), usually through the mass media. The term pundit describes both women and men, altho ...

Club, shortened later to just The club, a scientific and literary society before which the members read papers they had researched for the occasion. Morgan read papers to The Club every year for the rest of his life. He also joined the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

.

Morgan and other leading men of Rochester decided to found a university, the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

. It did not support the matriculation of women. The group resolved to found a college for women, the Barleywood Female University, which was advertised but apparently never started. In the same year of its foundation, 1852, the donor of the land on which it was to be located gave it to the University of Rochester instead. Morgan was gravely disappointed. He believed that equality of the sexes is a mark of advanced civilization. For the present, he lacked the wealth and connections to prevent the collapse of Barleywood. Later he would serve as a founding trustee of the board of Wells College in Aurora. In addition, he and Mary would leave their estate to the University of Rochester for the foundation of a women's college.

Success at last

In 1855 Morgan and other Rochester businessmen invested in the expanding metals industry of theUpper Peninsula

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan—also known as Upper Michigan or colloquially the U.P. or Yoop—is the northern and more elevated of the two major landmasses that make up the U.S. state of Michigan; it is separated from the Lower Peninsula b ...

of Michigan. After a brief sojourn on the 5-man board of the Iron Mountain Railroad, Morgan joined them in creating the Bay de Noquet and Marquette Railroad Company, connecting the entire Upper Peninsula by a single, ore-bearing line. He became its attorney and director. At that time the U.S. government was selling lands previously confiscated from the natives in cases where the sale benefited the public good. Although the Upper Peninsula was known for its great natural beauty, the discovery of iron persuaded Morgan and others to develop wide-scale mining and industrialization of the peninsula. He spent the next few years between Washington, lobbying for the sale of the land to his company, and in large cities such as Detroit and Chicago, where he fought lawsuits to prevent competitors from taking it. Morgan vigorously defended American capitalism to protect his own interests. After the stockholders refused to pay him for some of his legal work, he all but withdrew from business in favor of field work in anthropology.

In 1861 in the middle of his field work, Morgan was elected as Member of the New York State Assembly on the Republican ticket. The Morgans traditionally had belonged to the Whigs, which dissolved in 1856; most Whigs joined the Republicans, created in 1854. Morgan did not run with any agenda except his own as it pertained to the Iroquois. He was seeking appointment by the President of the United States as Commissioner of the new Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

(BIA). Morgan anticipated that William H. Seward would be elected president, and outlined to him plans to employ the natives in the manufacture and sale of Indian goods.

At the last moment Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

displaced Seward as the Republican candidate. The new president was deluged by letters from Morgan's associates asking that Morgan be appointed commissioner. Lincoln explained that the post had already been exchanged by his campaign manager for political support. With the chance for appointment lost, Morgan, who had made no pretense of interest in New York state's government, returned to field study of the natives.

Field anthropologist

After attending the 1856 meeting of theAmerican Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

, Morgan decided on an ethnology study to compare kinship systems. He conducted a field research program funded by himself and the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

, 1859–1862. He made four expeditions, two to the Plains tribes of Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

, and two more up the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

past Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

. This was before the development of any inland transportation system. Passengers on riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury ...

s could shoot Bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

and other game for food along the upper Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

. He collected data on 51 kinship systems. Tribes included the Winnebago, Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly, a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not linked scientifically to any certain trait but is rathe ...

, Yankton, Kaw, Blackfeet

The Blackfeet Nation (, ), officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Montana. Tribal members primarily belong ...

, Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

and others.

At the height of Morgan's anthropological field work, death struck his family. In May and June, 1862, their two daughters, ages 6 and 2, died as a result of scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'', a Group A streptococcus (GAS). It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age. The signs and symptoms include a sore ...

while Morgan was traveling in the West. In Sioux City, Iowa

Sioux City () is a city in Woodbury County, Iowa, Woodbury and Plymouth County, Iowa, Plymouth counties in the U.S. state of Iowa. The population was 85,797 in the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Iowa, fo ...

, Morgan received the news from his wife. He wrote in his journal:

Two of three of my children are taken. Our family is destroyed. The intelligence has simply petrified me. I have not shed a tear. It is too profound for tears. Thus ends my last expedition. I go home to my stricken and mourning wife, a miserable and destroyed man.

The Civil War

During this time, neither Morgan nor Mary showed any interest inabolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

, nor did they participate in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. They differed markedly from their friend Ely Parker. The latter attempted to raise an Iroquois regiment but was denied, on the grounds that he was not a US citizen, and denied service on the same ground. He entered the army finally by the intervention of his friend, Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, serving on Grant's staff. Parker was present at the surrender of General Lee; to Lee's remark that Parker was the "true American" (as an American Indian), he responded, "We are all Americans here, sir."

Morgan held no consistent views on the war. He could easily have joined the anti-slavery cause if he had wished to do so. Rochester, as the last station before Canada on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

, was a center of abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

published the '' North Star'' in Rochester. Like Morgan, Douglass supported the equality of women, yet they never made connection.

Morgan was anti-slavery but opposed abolitionism on the grounds that slavery was protected by law. Before the war he assented to the possible division of the nation on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences", that is, slavery, between regions. Morgan began to change his mind when some of his friends who had gone out to watch the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run, called the Battle of First Manassas

. by Confederate States ...

were captured and imprisoned by the Confederates for the duration. By the end of the war, he was insisting along with most others that . by Confederate States ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

be hanged as a traitor. In 1866 he formed the Rochester Committee for the Relief of Southern Starvation.

Morgan did participate indirectly in the war through his company. Recovering from the deaths of his daughters and having resolved to end the expeditions that had taken him away from home, he gave his life totally over to business. In 1863 he and Samuel Ely formed a partnership creating the Morgan Iron Company in northern Michigan. The war had created such a high demand for metals that within the first year of business, the company paid off its founding debt and offered 100% dividends on its stock. The demand went on until 1868, enabling the company to construct a blast furnace. Morgan became independently wealthy and could retire from the practice of law.

The Erie Railroad affair

Morgan took uptrout

Trout (: trout) is a generic common name for numerous species of carnivorous freshwater ray-finned fishes belonging to the genera '' Oncorhynchus'', ''Salmo'' and ''Salvelinus'', all of which are members of the subfamily Salmoninae in the ...

fishing during his Michigan period. He fished in the wilds of Michigan during the summers, sometimes with Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

guides. During this recreational activity, he became interested in beavers

Beavers (genus ''Castor'') are large, semiaquatic rodents of the Northern Hemisphere. There are two existing species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers are the second-large ...

, which had greatly modified the lowlands. After several summers of tracking and observing beavers in the field, in 1868 he published a work describing in detail the biology and habits of this animal, which shaped the environment through its construction of dams.

In that year also, his wealth secure and free of business, Morgan entered the state government again as a senator, 1868–1869, still seeking appointment as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

. He was ridiculed by the ''Union Advertiser'' as being a "hobby candidate". The Republicans that year were running on a platform of moral probity. They argued that as a superior class, they could and should serve as guardians of the public morals. Morgan passed muster on the heredity because of his descent and Mary's descent from William Bradford, of Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English sailing ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, reac ...

note. Morgan soon was immersed in such issues as whether beer drinking on Sunday should be allowed (a veiled hit at the new German immigrants).

As member of the Standing Committee on Railroads, Morgan became embroiled in a major issue of the day and one closer to his interests: monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic Competition (economics), competition to produce ...

. The New York Central Railroad

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected New York metropolitan area, gr ...

, under Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

, had attempted a hostile takeover of the Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Northeastern United States, originally connecting Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey, with Lake Erie at Dunkirk, New York. The railroad expanded west to Chicago following its 1865 ...

under Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

by buying up its stock. The two railroads competed for the Rochester market. Daniel Drew

Daniel Drew (July 29, 1797 – September 18, 1879) was an American businessman, steamship and railroad developer, and financier, one of the " robber barons" of the Gilded Age. Summarizing his life, Henry Clews wrote: "Of all the great oper ...

, Erie's treasurer, defended successfully by creating new stock, which he had his friends sold short, dropping the value of the stock. Vanderbilt dumped the stock, barely covering the losses. Ordinarily such stock manipulations were illegal. The Railroad Act of 1850, however, allowed railroads to borrow money in exchange for bonds convertible to stocks. Given essentially free stocks, friends of the Erie Railroad grew rich; that is, Drew had found a way to transfer Vanderbilt's wealth to his own friends. Vanderbilt just escaped ruin. He immediately appealed to the state government.

The Railroad Committee investigated the affair. Gould purchased inaction among the senators, a practice Morgan had seen in the Ogden Land Company Affair. This time he worked to protect his friends from investigation. No action was taken. The Erie Railroad affair tapped Morgan's deepest ideological beliefs. To him the role of capitalism in creating mobile wealth was essential to the advancement of civilization. A monopoly such as Vanderbilt had been trying to build would choke off the downward flow of wealth. His report of the Railroad Committee attacked both Vanderbilt and Gould. It argued that the system in its "tendency to combination" was broken. He asserted that the people had to use government action to rein in the power of large corporations. For the time being the Erie Railroad was supported, but Morgan noted that its victory was just as dangerous to society as its defeat would have been.

The Grant-Parker policy on Native Americans

Despite his new interest in government, which was to come to be expressed in his subsequent works on social systems, Morgan persisted in his major goal in running for office, to be appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs. The choice was now up to President Grant. Together in ''The League'', Parker and Morgan had determined the policy Grant was to adopt. They thought that, much as Parker had assimilated, American Indians should assimilate into American society; they were not yet considered US citizens. Of the two men responsible for his policy, Grant chose his former adjutant. Terribly disappointed, Morgan never applied for the post again. The two collaborators did not speak to each other during Parker's tenure, but Morgan stayed on intimate terms with Parker's family. The implementation of assimilation policy was more difficult than either man had anticipated. Parker controlled none of the variables. The American Indians were to be moved into reservations, assisted with supplies and food so they could start subsistence farming, and educated at mission schools to be converted to Christianity and American values, until they adopted European-American ways. In theory they would then be able to enter American society at large. The system of appointed Indian agents and traders had long been corrupt; in addition, unscrupulous land agents took the best land and moved American Indians into the desert lands, which did not support small-scale household farms and did not have sufficient game for hunting. Thieves among the agents replaced food and goods intended for the Indians with inedible or no foodstuffs. Faced with these realities, the American Indians refused the reservations or abandoned them, and attempted to return to ancestral lands, now occupied by white settlers. In other cases, they raided white settlements for food or attacked them seeking to repel the invaders. Grant resorted to military solutions and used U.S. soldiers to repress the tribes. This warfare exacerbated the failure of the army to protect the American Indians against depredations and encroachment by white settlers. In 1871 Congress took action to halt the suppression of the Natives. It created a Board of Indian Commissioners and relieved Parker of his main responsibilities. Parker resigned in protest. After suffering years of poverty and attempt to suppress their cultures, American Indians were admitted to citizenship in 1924. The government continued to send their children to Indian boarding schools, started in the late 1870s, where Indian languages and cultures were prohibited. Policies of diversity and limited sovereignty were adopted. The Grant administration is universally regarded as inept in Indian affairs as well as have been rife with corruption. Although Morgan contributed to the ideology of assimilation, he escaped accountability for the results.Later career

Having failed to becomeCommissioner of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

, Morgan applied for various ambassadorships under the Grant administration, including to China and Peru. Grant's administration rejected all the applications, after which Morgan resolved to visit Europe on his own with a professional as well as a personal agenda.

For one year, 1870–71, the three Morgans went on a grand tour of Europe. During his European travels, Morgan met Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

and the great British anthropologists

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

of the age. He visited Sir John Lubbock, who had coined the words "Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

" and "Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

", and used the terms "barbarians" and "savages" in his own studies of the three-age system

The three-age system is the periodization of human prehistory (with some overlap into the history, historical periods in a few regions) into three time-periods: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age, although the concept may also re ...

. Morgan adopted these terms, but with an altered sense, in ''Ancient Society''. Lubbock was using modern ethnology as he knew it to reconstruct the ways of human ancestors. Lubbock's main works had already been published by the time of Morgan's visit. Morgan recorded his European travel and contacts in a journal of several volumes. Extracts were published in 1937 by Leslie White.

He continued with his independent scholarship, never becoming affiliated with any university, although he associated with university presidents and the leading ethnologists looked up to him as a founder of the field. He was an intellectual mentor to those who followed, including John Wesley Powell, who became head of the Bureau of Ethnology in 1879 at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

. Morgan was consulted by the highest levels of government on appointments and other ethnological matters. In 1878 he conducted one final field trip, leading a small party in search of native ruins in the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

. They were the first to describe the so-called Aztec ruins (actually built by the Ancestral Puebloans

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as Ancestral Pueblo peoples or the Basketmaker-Pueblo culture, were an ancient Native American culture of Pueblo peoples spanning the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southe ...

) on the Animas River but missed discovering Mesa Verde.

Death and legacy

In 1879 Morgan completed two construction projects. One was his library, an addition to the house he had purchased with Mary many years before and where he died in December 1881. He combined the opening of the library with a celebration of the 25th anniversary of The club. It included a dinner for 40 persons, who were by that time the leading lights of Rochester. The library acquired some fame as a local monument. Pictures were taken and published. The Club only met there one other time, however, at Morgan's funeral in 1881. The second building project was a mausoleum for his daughters in Mount Hope Cemetery. It became the resting place of the entire remainder of the family, starting with Lewis. His wife survived him by two years. They both left wills. A nephew of Lewis moved to Rochester with his family and took up residence in the house to care for Lewis' and Mary's son. On the son's death 20 years later, the entire estate reverted to the University of Rochester, which by the terms of the wills was to use the funds for the endowment of a college for women, dedicated as a memorial to the Morgan daughters. The nephew attempted to break the wills on his behalf but lost the case in the state supreme court. The house with the library survived into mid-20th-century, when it was demolished to make way for a highway bypass system. Materials relating to Morgan's writings are held in a special collection at theUniversity of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

library.

Lewis Henry Morgan Lecture

The Lewis Henry Morgan Lecture is a distinguished lecture held annually by the Department of Anthropology at theUniversity of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

. Begun in 1963, the lectures honor the career and seminal research of American anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan. Many of the lectures have been published, including the inaugural one by South African anthropologist Meyer Fortes

Meyer Fortes FBA FRAI (25 April 1906 – 27 January 1983) was a South African-born anthropologist, best known for his work among the Tallensi and Ashanti in Ghana.

Originally trained in psychology, Fortes employed the notion of the "perso ...

.

Professional associations

Morgan was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1865. He was elected president of theAmerican Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

in 1879. Morgan was also a member of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

.

Thought

Work in ethnology

In the 1840s, Morgan had befriended the young Ely S. Parker of theSeneca tribe

The Seneca ( ; ) are a group of indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their nation was the farthe ...

and the Tonawanda Reservation. With a classical missionary education, Parker went on to study law. With his help, Morgan studied the culture and the structure of Iroquois society. Morgan had noticed they used different terms than Europeans to designate individuals by their relationships within the extended family. He had the creative insight to recognize this was meaningful in terms of their social organization. He defined European terms as "descriptive" and Iroquois (and Native American) terms as " classificatory", terms that continue to be used as major divisions by anthropologists and ethnographers.

Based on his research enabled by Parker, Morgan and Parker wrote and published ''The League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee or Iroquois'' (1851). Morgan dedicated the book to Parker (who was then 23) and "our joint researches". In subsequent publications of the book Parker's name was omitted. This work presented the complexity of Iroquois society in a path-breaking ethnography that was a model for future anthropologists, as Morgan presented the kinship system of the Iroquois with unprecedented nuance.

Morgan expanded his research far beyond the Iroquois. Although Benjamin Barton had posited Asian origins for Native Americans as early as 1797, in the mid-nineteenth century, other American and European scholars still supported widely varying ideas, including a theory they were one of the lost tribes of Israel, because of the strong influence of biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

and classical conceptions of history. Morgan had begun to theorize the Native Americans originated in Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

. He thought he could prove it by a broad study of kinship terms used by people in Asia as well as tribes in North America.

He wanted to provide evidence for monogenesis, the theory that all human beings descend from a common source (as opposed to polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that humans are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views find little merit ...

).

In the late 1850s and 1860s, Morgan collected kinship data from a variety of Native American tribes. In his quest to do comparative kinship studies, Morgan also corresponded with scholars

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a terminal ...

, missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

, US Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the U.S. government.

Agents established in Nonintercourse Act of 1793

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the Un ...

s, colonial agents, and military officers around the world. He created a questionnaire which others could complete so he could collect data in a standardized way. Over several years, he made months-long trips across the Old West to further his research.

With the help of local contacts and, after intensive correspondence over the course of years, Morgan analyzed his data and wrote his seminal '' Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family'' (1871), which was printed by the Smithsonian Press. It "created at a stroke what without exaggeration might be called the seminal concern of contemporary anthropology, the study of kinship ..." In this work, Morgan set forth his argument for the unity of humankind. At the same time, he presented a sophisticated schema of social evolution based upon the relationship terms, the categories of kinship, used by peoples around the world. Through his analysis of kinship terms, Morgan discerned that the structure of the family and social institutions develop and change according to a specific sequence.

Theory of social evolution

This original theory became less relevant because of theDarwinian

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sele ...

revolution, which demonstrated how change happens over time. In addition, Morgan became increasingly interested in the comparative study of kinship (family) relations as a window into understanding larger social dynamics. He saw kinship relations as the basic part of society.

In the years that followed, Morgan developed his theories. Combined with an exhaustive study of classic Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Roman sources, he crowned his work with his ''magnum opus'' '' Ancient Society'' (1877). Morgan elaborated upon his theory of social evolution. He introduced a critical link between social progress and technological progress. He emphasized the centrality of family and property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, re ...

relations. He traced the interplay between the evolution of technology, of family relations, of property relations, of the larger social structures and systems of governance, and intellectual development.

Looking across an expanded span of human existence, Morgan presented three major stages: savagery, barbarism, and civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

. He divided and defined the stages by technological inventions, such as use of fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

, bow, pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

in the savage era; domestication of animals

The domestication of vertebrates is the mutual relationship between vertebrate animals, including birds and mammals, and the humans who influence their care and reproduction.

Charles Darwin recognized a small number of traits that made domestica ...

, agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, and metalworking

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals in order to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term, it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on e ...

in the barbarian era; and development of the alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

and writing

Writing is the act of creating a persistent representation of language. A writing system includes a particular set of symbols called a ''script'', as well as the rules by which they encode a particular spoken language. Every written language ...

in the civilization era. In part, this was an effort to create a structure for North American history that was comparable to the three-age system

The three-age system is the periodization of human prehistory (with some overlap into the history, historical periods in a few regions) into three time-periods: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age, although the concept may also re ...

of European pre-history, which had been developed as an evidence-based system by the Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen in the 1830s; his work (Guideline to Scandinavian Antiquity) was published in English in 1848. The concept of evidence-based chronological dating received wider notice in English-speaking nations as developed by J. J. A. Worsaae, whose ''The Primeval Antiquities of Denmark'' was published in English in 1849.

Initially Morgan's work was accepted as integral to American history, but later it was treated as a separate category of anthropology. Henry Adams wrote of ''Ancient Society'' that it "must become the foundation of all future work in American historical science." The historian Francis Parkman also was a fan, but later nineteenth-century historians pushed Native American history to the side of the American story.

Morgan's final work, ''Houses and House-life of the American Aborigines'' (1881), was an elaboration on what he had originally planned as an additional part of ''Ancient Society''. In it, Morgan presented evidence, mostly from North and South America, that the development of house architecture and house culture reflected the development of kinship and property relations.

Although many specific aspects of Morgan's evolutionary position have been rejected by later anthropologists, his real achievements remain impressive. He founded the sub-discipline of kinship studies. Anthropologists remain interested in the connections which Morgan outlined between material culture and social structure. His impact has been felt far beyond the Ivory Tower.

Influence on Marxism

In 1881,Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

started reading Morgan's ''Ancient Society'', thus beginning Morgan's posthumous influence among European thinkers. Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. and near non-existent rates of crime.

In JSTOR

* *

1963 reissue of ''Ancient Society''

with introductions by Eleanor Leacock * * * Knight, C. 2008

Early Human Kinship was Matrilineal.

In N. J. Allen, H. Callan, R. Dunbar and W. James (eds), ''Early Human Kinship.'' London: Royal Anthropological Institute, pp. 61–82. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, Lewis H 1818 births 1881 deaths People from Aurora, Cayuga County, New York American people of Welsh descent Republican Party members of the New York State Assembly New York (state) state senators American anthropologists American feminists Economic anthropologists Activists for Native American rights Union College (New York) alumni Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery (Rochester) University of Rochester 19th-century members of the New York State Legislature

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. and near non-existent rates of crime.

Eponymous honors

* Annual lecture in Morgan's name at the Anthropology Department of theUniversity of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

.

* Rochester Public School #37 in the 19th Ward named "Lewis H. Morgan #37 School"

* Lewis Henry Morgan Institute (a research organization), State University of New York Institute of Technology, SUNYIT, Utica, New York

* Lewis H. Morgan Rochester Regional Chapter of the New York State Archeological Association

List of Morgan's writings

Lewis Morgan wrote continuously, whether letters, papers to be read, or published articles and books. A list of his major works follows. Some of the letters and papers have been omitted. A complete list, as far as was known, is given by Lloyd in the 1922 revised edition (posthumous) of ''The League ... ''. Specifically omitted are 14 "Letters on the Iroquois" read before the New Confederacy, 1844–1846, and published in ''The American Review: A Whig Journal, The American Review'' in 1847 under another pen name, Skenandoah; 31 papers read before The club, 1854–1880; and various book reviews published in ''The Nation''.See also

* Cultural evolution * Sociocultural evolution * Ethnology * Unilineal evolution * Origins of society * List of important publications in anthropologyReferences

Bibliography

* * * . * . * * * * Stern, Bernhard J. "Lewis Henry Morgan Today; An Appraisal of His Scientific Contributions," ''Science & Society,'' vol. 10, no. 2 (Spring 1946), pp. 172–176In JSTOR

* *

External links

* * * *1963 reissue of ''Ancient Society''

with introductions by Eleanor Leacock * * * Knight, C. 2008

Early Human Kinship was Matrilineal.

In N. J. Allen, H. Callan, R. Dunbar and W. James (eds), ''Early Human Kinship.'' London: Royal Anthropological Institute, pp. 61–82. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, Lewis H 1818 births 1881 deaths People from Aurora, Cayuga County, New York American people of Welsh descent Republican Party members of the New York State Assembly New York (state) state senators American anthropologists American feminists Economic anthropologists Activists for Native American rights Union College (New York) alumni Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery (Rochester) University of Rochester 19th-century members of the New York State Legislature