Lazzaro Spallanzani on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

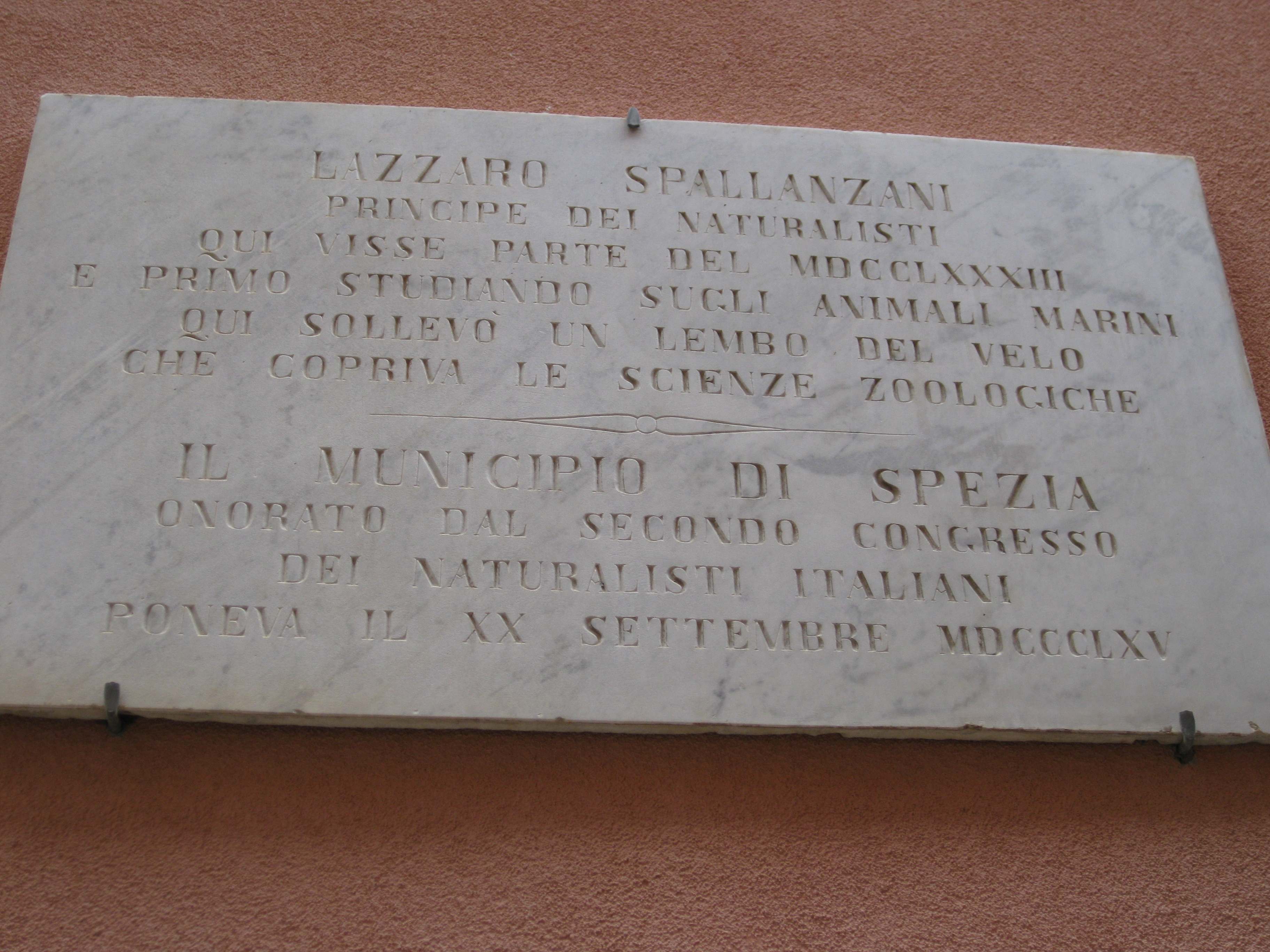

Lazzaro Spallanzani (; 12 January 1729 – 11 February 1799) was an Italian

Spallanzani was born in Scandiano in the modern

Spallanzani was born in Scandiano in the modern

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

priest (for which he was nicknamed Abbé

''Abbé'' (from Latin , in turn from Greek , , from Aramaic ''abba'', a title of honour, literally meaning "the father, my father", emphatic state of ''abh'', "father") is the French word for an abbot. It is also the title used for lower-ranki ...

Spallanzani), biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

and physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out chemical and ...

who made important contributions to the experimental study of bodily functions, animal reproduction, and animal echolocation

Echolocation, also called bio sonar, is a biological active sonar used by several animal groups, both in the air and underwater. Echolocating animals emit calls and listen to the Echo (phenomenon) , echoes of those calls that return from various ...

. His research on biogenesis

Spontaneous generation is a Superseded scientific theories, superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from abiotic component, non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was Hypoth ...

paved the way for the downfall of the theory of spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

, a prevailing idea at the time that organisms develop from inanimate matters, though the final death blow to the idea was dealt by French scientist Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

a century later.

His most important works were summed up in his book ''Expériences pour servir a l'histoire de la génération des animaux et des plantes'' (''Experiences to Serve to the History of the Generation of Animals and Plants''), published in 1785. Among his contributions were experimental demonstrations of fertilisation

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a zygote and initiate its development into a new individual organism or of ...

between ova and spermatozoa, and ''in vitro'' fertilisation''.''

Biography

province of Reggio Emilia

The province of Reggio Emilia (; Emilian: ''pruvînsa ed Rèz'') is a province in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. The capital city, which is the most densely populated ''comune'' (municipality) in the province, is Reggio Emilia.

It has an ...

to Gianniccolo Spallanzani and Lucia Zigliani. His father, a lawyer by profession, was not impressed with young Spallanzani who spent more time with small animals than studies. With financial support from the Vallisnieri Foundation, his father enrolled him in the Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

Seminary at age 15. When he was asked to join the order, he declined. Persuaded by his father and with the help of Monsignor Castelvetro, the Bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

of Reggio, he studied law at the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

, which he gave up soon and turned to science. Here, his famous kinswoman, Laura Bassi

Laura Maria Caterina Bassi Veratti (29 October 1711 – 20 February 1778) was an Italian physicist and academic. Recognized and depicted as "Minerva" (goddess of wisdom), she was the first woman to have a doctorate in science, and List of women ...

, was a professor of physics and it is to her influence that his scientific impulse has been usually attributed. With her, he studied natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

and mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, and gave also great attention to languages, both ancient and modern, but soon abandoned them. It took him a good friend Antonio Vallisnieri Jr. to convince his father to drop law as a career and take up academics instead.

In 1754, at the age of 25, soon after he was ordained he became professor of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

in the University of Reggio. In 1763, he was moved to the University of Modena

The University of Modena and Reggio Emilia (), located in Modena and Reggio Emilia, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, is one of the oldest universities in Europe, founded in 1175, with a population of 20,000 students.

The medieval university disappeared b ...

, where he continued to teach with great assiduity and success, but devoted his whole leisure to natural science. There he also served as a priest of the Congregation Beata Vergine and S. Carlo. He declined many offers from other Italian universities and from St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

until 1768, when he accepted the invitation of Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa (Maria Theresia Walburga Amalia Christina; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was the ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position suo jure, in her own right. She was the ...

to the chair of natural history in the University of Pavia

The University of Pavia (, UNIPV or ''Università di Pavia''; ) is a university located in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. There was evidence of teaching as early as 1361, making it one of the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest un ...

, which was then being reorganized. He also became director of the museum, which he greatly enriched by the collections of his many journeys along the shores of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. In June 1768 Spallanzani was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

and in 1775 was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

.

In 1785 he was invited to University of Padua

The University of Padua (, UNIPD) is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza; thus, it is the second-oldest ...

, but to retain his services his sovereign doubled his salary and allowed him leave of absence for a visit to Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, where he remained nearly a year and made many observations, among which may be noted those of a copper mine in Chalki and of an iron mine at Principi. His return home was almost a triumphal progress: at Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

he was cordially received by Joseph II and on reaching Pavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

he was met with acclamations outside the city gates by the students of the university. During the following year, his students exceeded five hundred. While he was travelling in the Balkans and to Constantinople, his integrity in the management of the museum was called in question (he was accused of the theft of specimens from the university's collection to add to his own cabinet of curiosities), with letters written across Europe to damage Spallanzani's reputation. A judicial investigation speedily cleared his honour to the satisfaction of some of his accusers. But Spallanzani got his revenge on his principal accuser, Giovanni Antonio Scopoli

Giovanni Antonio Scopoli (sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Johannes Antonius Scopolius) (3 June 1723 – 8 May 1788) was an Italians, Italian physician and natural history, naturalist. His biographer Otto Guglia named him the "first ...

, by preparing a fake specimen of a new "species". When Scopoli published the remarkable specimen, Spallanzani revealed the joke, resulting in wide ridicule and humiliation.

In 1796, Spallanzani received an offer for professor at the National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History ( ; abbr. MNHN) is the national natural history museum of France and a of higher education part of Sorbonne University. The main museum, with four galleries, is located in Paris, France, within the ...

in Paris, but declined due to his age. He died from bladder cancer on 12 February 1799, in Pavia. After his death, his bladder was removed for study by his colleagues, after which it was placed on public display in a museum in Pavia, where it remains to this day.

His indefatigable exertions as a traveller, his skill and good fortune as a collector, his brilliance as a teacher and expositor, and his keenness as a controversialist no doubt aid largely in accounting for Spallanzani's exceptional fame among his contemporaries; his letters account for his close relationships with many famed scholars and philosophers, like Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, and cosmology, cosmologist. He held the position of ''intendant'' (director) at the ''Jardin du Roi'', now ca ...

, Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

Spallanzani collection

Musei Civici of Reggio Emilia

Page describing, with pictures, some of Lazzaro Spallanzani's memories

Official site of "Centro Studi Lazzaro Spallanzani" (Scandiano)

Zoologica

Göttingen State and University Library Digitised ''Viaggi alle due Sicilie e in alcune parti dell'Appennino''

Guide to the Lazzaro Spallanzani Papers 1768-1793

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spallanzani, Lazzaro 1729 births 1799 deaths People from Scandiano 18th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Catholic clergy scientists Italian entomologists Deaths from cancer in Lombardy Deaths from bladder cancer Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Italian physiologists

CNRS (

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

. Yet greater qualities were by no means lacking. His life was one of incessant eager questioning of nature on all sides, and his many and varied works all bear the stamp of a fresh and original genius, capable of stating and solving problems in all departments of science—at one time finding the true explanation of stone skipping

Stone skipping and stone skimming are the arts of throwing a flat Rock (geology), stone across water in such a way (usually Sidearm (baseball), sidearm) that it bounces off the surface. "Skipping" counts the number of bounces; "skimming" measur ...

(formerly attributed to the elasticity of water) and at another helping to lay the foundations of our modern volcanology

Volcanology (also spelled vulcanology) is the study of volcanoes, lava, magma and related geology, geological, geophysical and geochemistry, geochemical phenomena (volcanism). The term ''volcanology'' is derived from the Latin language, Latin ...

and meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

.

Scientific contributions

Spontaneous generation

Spallanzani's first scientific work was in 1765 ''Saggio di osservazioni microscopiche concernenti il sistema della generazione de' signori di Needham, e Buffon'' (''Essay on microscopic observations regarding the generation system of Messrs. Needham and Buffon'') which was the first systematic rebuttal of the theory of thespontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

. At the time, the microscope was already available to researchers, and using it, the proponents of the theory, Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (; ; 1698 – 27 July 1759) was a French mathematician, philosopher and man of letters. He became the director of the Académie des Sciences and the first president of the Prussian Academy of Science, at the i ...

, Buffon and John Needham, came to the conclusion that there is a life-generating force inherent to certain kinds of inorganic matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

that causes living microbes to create themselves if given sufficient time. Spallanzani's experiment showed that it is not an inherent feature of matter and that it can be destroyed by an hour of boiling. As the microbes did not re-appear as long as the material was hermetically sealed, he proposed that microbes move through the air and that they could be killed through boiling. Needham argued that experiments destroyed the "vegetative force" that was required for spontaneous generation to occur. Spallanzani paved the way for research by Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

, who defeated the theory of spontaneous generation almost a century later.

Digestion

In his work ''Dissertationi di fisica animale e vegetale'' (''Dissertation on the physiology of animals and vegetables'', in 2 volumes, 1780), Spallanzani was the first to explain the process of digestion in animals. Here he first interpreted the process ofdigestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

, which he proved to be no mere mechanical process of trituration – that is, of grinding up the food – but one of actual chemical solution, taking place primarily in the stomach, by the action of the gastric juice

Gastric glands are glands in the lining of the stomach that play an essential role in the digestion, process of digestion. Their secretions make up the gastric acid, digestive gastric juice. The gastric glands open into gastric pits in the gastri ...

.

Reproduction

Spallanzani described animal (mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

) reproduction in his ''Experiencias Para Servir a La Historia de La Generación De Animales y Plantas'' (1786). He was the first to show that fertilisation requires both spermatozoa

A spermatozoon (; also spelled spermatozoön; : spermatozoa; ) is a motile sperm cell (biology), cell produced by male animals relying on internal fertilization. A spermatozoon is a moving form of the ploidy, haploid cell (biology), cell that is ...

and an ovum

The egg cell or ovum (: ova) is the female reproductive cell, or gamete, in most anisogamous organisms (organisms that reproduce sexually with a larger, female gamete and a smaller, male one). The term is used when the female gamete is not capa ...

. He was the first to perform in vitro fertilization

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a process of fertilisation in which an egg is combined with sperm in vitro ("in glass"). The process involves monitoring and stimulating the ovulatory process, then removing an ovum or ova (egg or eggs) from ...

, with frogs, and an artificial insemination

Artificial insemination is the deliberate introduction of sperm into a female's cervix or uterine cavity for the purpose of achieving a pregnancy through in vivo fertilization by means other than sexual intercourse. It is a fertility treatment ...

, using a dog. Spallanzani showed that some animals, especially newts

A newt is a salamander in the subfamily Pleurodelinae. The terrestrial juvenile phase is called an eft. Unlike other members of the family Salamandridae, newts are semiaquatic, alternating between aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Not all aqua ...

, can regenerate some parts of their body if injured or surgically removed.

In spite of his scientific background, Spallanzani endorsed preformationism

In the history of biology, preformationism (or preformism) is a formerly popular theory that organisms develop from miniature versions of themselves. Instead of assembly from parts, preformationists believed that the form of living things exis ...

, an idea that organisms develop from their own miniature selves; e.g. animals from minute animals, animalcules

Animalcule (; ) is an archaic term for microscopic organisms that included bacteria, protozoans, and very small animals. The word was invented by 17th-century Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek to refer to the microorganisms he observed i ...

. In 1784, he performed a filtration experiment in which he successfully separated the seminal fluid of frogs – a liquid portion and a gelatinous animalcule (spermatozoa) portion. But then he assumed that it was the liquid part which could induce fertilisation. A staunch ovist, he believed that animal form was already developed in the eggs and fertilisation by semen was only an activation for growth.

Echolocation

Spallanzani is also famous for extensive experiments in 1793 on how bats could fly at night to detect objects (including prey) and avoid obstacles, where he concluded that bats do not use their eyes for navigation, but some other sense. He was originally inspired by his observation that tamedbarn owl

The barn owls, owls in the genus '' Tyto'', are the most widely distributed genus of owls in the world. They are medium-sized owls with large heads and characteristic heart-shaped faces. They have long, strong legs with powerful talons. The ter ...

flew properly at night under a dim-lit candle, but struck against the wall when the candle was put out. He managed to capture three wild bats in Scandiano, and performed a similar experiment, on which he wrote (on 20 August 1793):

A few days later he took two bats and covered their eyes with an opaque disc made of birdlime

Birdlime or bird lime is an adhesive substance used in Animal trapping, trapping birds. It is spread on a branch or twig, upon which a bird may land and be caught. Its use is illegal in many jurisdictions.

Manufacture

Historically, the substanc ...

. To his astonishment, both bats flew completely normally. He went further by surgically removing the eyeballs of one bat, which he observed as:

He concluded that bats do not need vision for navigation; although he failed to find the reason. At the time other scientists were sceptical and ridiculed his findings. A contemporary of Spallanzani, the Swiss physician and naturalist Louis Jurine, learned of Spallanzani's experiments, investigated the possible mechanism of bat navigation. He discovered that bat flight was disoriented when their ears were plugged. But Spallanzani did not believe that it was about hearing since bats flew very silently. He repeated his experiments by using improved ear plugs using turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthine, terebenthene, terebinthine and, colloquially, turps) is a fluid obtainable by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Principall ...

, wax, pomatum or tinder

Tinder is easily Combustibility and flammability, combustible material used to Firemaking, start a fire. Tinder is a finely divided, open material which will begin to glow under a shower of sparks. Air is gently wafted over the glowing tinder unt ...

mixed with water, to find that blinded bats could not navigate without hearing. He was still suspicious that deafness alone was the cause of disoriented flight and that hearing was vital that he conducted some rather painful experiments such as burning and removing the external ear, and piercing through the inner ear. After these operations, he became convinced that hearing was fundamental to normal bat flight, upon which he noted:

By then he was too convinced that he suggested the ear was an organ of navigation, writing:

His pupil, Paolo Spadoni (1764-1826), also published observations on the topic.

The exact scientific principle was discovered only in 1938 by two American biologists Donald Griffin

Donald Redfield Griffin (August 3, 1915 – November 7, 2003) was an American professor of zoology at various universities who conducted seminal research in animal behavior, animal navigation, acoustic orientation and sensory biophysics. In 1938 ...

and Robert Galambos.

Fossils

Spallanzani studied the formation and origin of marine fossils found in distant regions of the sea and over the ridge mountains in some regions of Europe, which resulted in the publication in 1755 of a small dissertation, "''Dissertazione sopra i corpi marino-montani then presented at the meeting the Accademia degli Ipocondriaci di Reggio Emilia''". Although aligned to one of the trends of his time, which attributed the occurrence of marine fossils on mountains to the natural movement of the sea, not the universal flood, Spallanzani developed his own hypothesis, based on the dynamics of the forces that changed the state of the Earth after God's creation. A few years later, Spallanzani published reports about trips he made to Portovenere, Cerigo Island, and Two Sicilies, addressing important issues such as the discovery of fossil shells within volcanic rocks, human fossils, and the existence of fossils of extinct species. His concern with fossils witnesses how, in the style of the eighteenth century, Spallanzani integrated studies of the three kingdoms of nature.Other works

Spallanzani studied and made important descriptions on blood circulation and respiration. In 1777, he gave the nameTardigrada

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged Segmentation (biology), segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who calle ...

(from Latin meaning "slow-moving") to the phylum of minute extremophile animals also called water bears.

In 1788 he visited Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ) is a Somma volcano, somma–stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuv ...

and the volcanoes of the Lipari Islands

Lipari (; ) is a ''comune'' including six of seven islands of the Aeolian Islands (Lipari, Vulcano, Panarea, Stromboli, Filicudi and Alicudi) and it is located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, Southern Italy; it is admin ...

and Mount Etna in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. He visited the latter along with Carlo Gemmellaro. He embodied the results of his research in a large work (''Viaggi alle due Sicilie ed in alcune parti dell'Appennino''), published four years later.

Much of his collections, which he kept at the end of his life in his house in Scandiano, were purchased by the city of Reggio Emilia

Reggio nell'Emilia (; ), usually referred to as Reggio Emilia, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, and known until Unification of Italy, 1861 as Reggio di Lombardia, is a city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has about 172,51 ...

in 1799. They are now on display inside the Palazzo dei Musei in two rooms denominated the ''Museo Spallanzani''.Musei Civici of Reggio Emilia

Publications

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Honours

Spallanzani was elected Fellow of theRoyal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

. He was member of Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences () was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin Academy" may also refer. In the 18th century, when Frenc ...

, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

, and Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities

The Göttingen Academy of Sciences (name since 2023 : )Note that the German ''Wissenschaft'' has a wider meaning than the English "Science", and includes Social sciences and Humanities. is the oldest continuously existing institution among the eig ...

.

See also

* List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics * Charles JurineReferences

Bibliography

General

*Paul de Kruif

Paul Henry de Kruif (, rhyming with "life") (March 2, 1890 – February 28, 1971) was an American microbiologist and writer. Publishing as Paul de Kruif, he is known for his 1926 book, ''Microbe Hunters''. This book was not only a bestseller for a ...

, ''Microbe Hunters'' (2002 reprint) ;

*Nordenskiöld, E. P. 1935 pallanzani, L.''Hist. of Biol''. 247–248

*Rostand, J. 1997, ''Lazzaro Spallanzani e le origini della biologia sperimentale'', Torino, Einaudi.

*

Work on insects

* *Gibelli, V. 1971 ''L. Spallanzani''. Pavia. *Lhoste, J. 1987 ''Les entomologistes français. 1750–1950''. INRA (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique), Paris. *Osborn, H. 1946 ''Fragments of Entomological History Including Some Personal Recollections of Men and Events''. Columbus, Ohio, Published by the Author. *Osborn, H. 1952 ''A Brief History of Entomology Including Time of Demosthenes and Aristotle to Modern Times with over Five Hundred Portraits''.Columbus, Ohio, The Spahr & Glenn Company.External links

*Page describing, with pictures, some of Lazzaro Spallanzani's memories

Official site of "Centro Studi Lazzaro Spallanzani" (Scandiano)

Zoologica

Göttingen State and University Library Digitised ''Viaggi alle due Sicilie e in alcune parti dell'Appennino''

Guide to the Lazzaro Spallanzani Papers 1768-1793

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spallanzani, Lazzaro 1729 births 1799 deaths People from Scandiano 18th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Catholic clergy scientists Italian entomologists Deaths from cancer in Lombardy Deaths from bladder cancer Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Italian physiologists