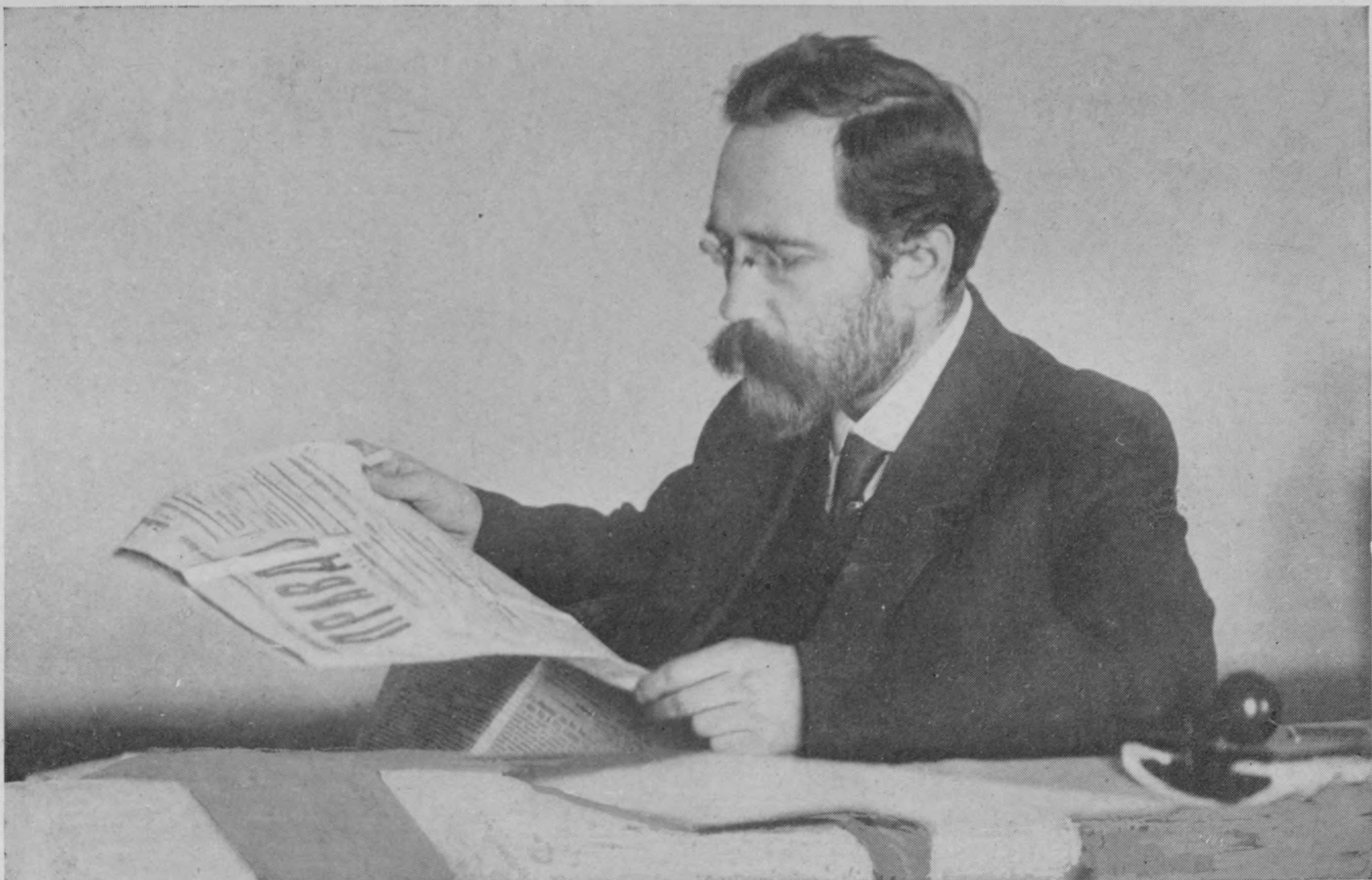

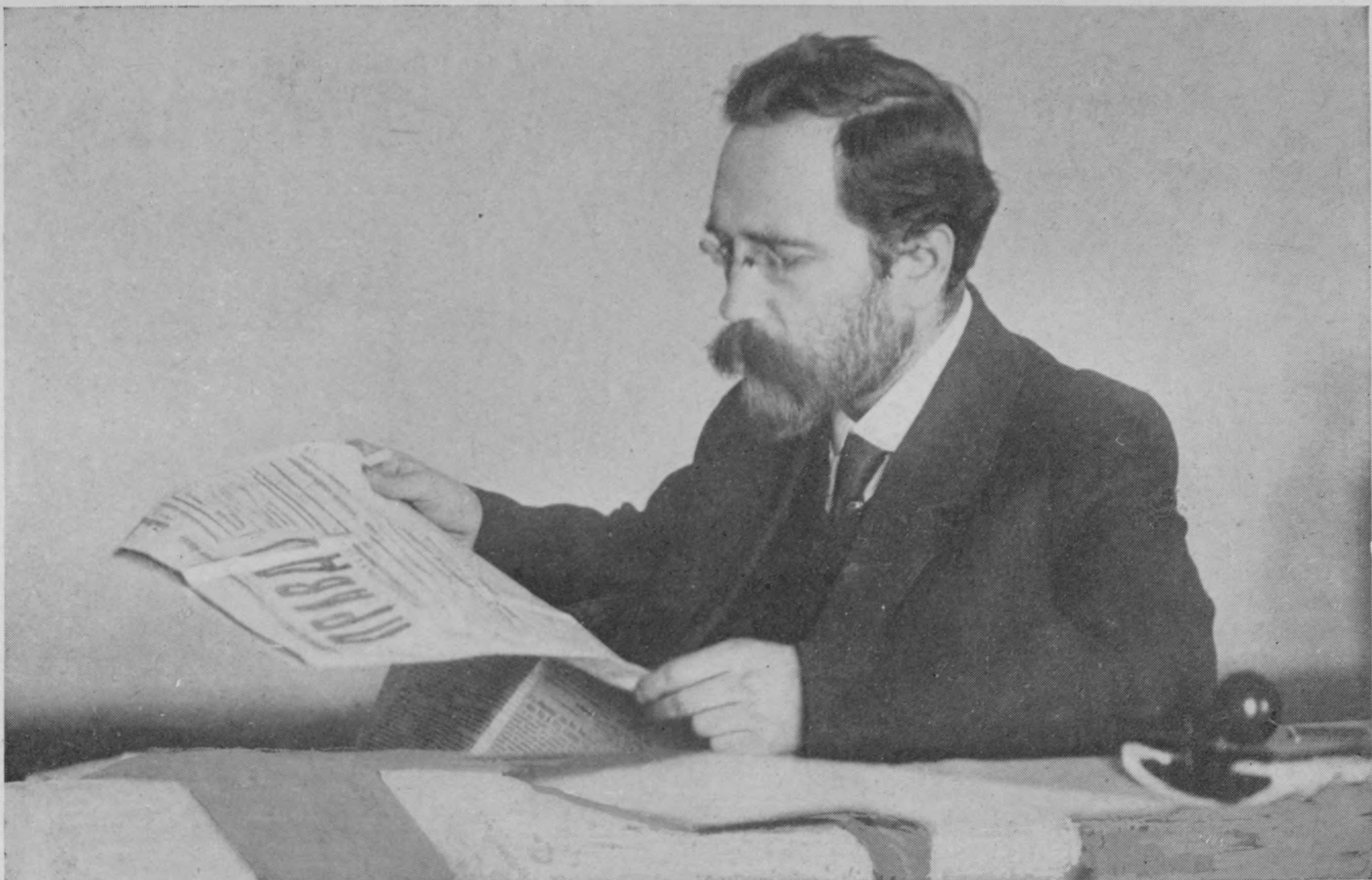

Lev Borisovich Rozenfeld on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent

On 25 March 1917, Kamenev returned from Siberian exile to St. Petersburg (renamed as

On 25 March 1917, Kamenev returned from Siberian exile to St. Petersburg (renamed as

In October 1924, Stalin proposed his new theory of Socialism in One Country in opposition to Trotsky's theory of

In October 1924, Stalin proposed his new theory of Socialism in One Country in opposition to Trotsky's theory of

With Trotsky mainly on the sidelines through a persistent illness, the Zinoviev-Kamenev-Stalin triumvirate collapsed in April 1925, although the political situation was hanging in the balance for the rest of the year. All sides spent most of 1925 lining up support behind the scenes for the December Communist Party Congress. Stalin struck an alliance with

With Trotsky mainly on the sidelines through a persistent illness, the Zinoviev-Kamenev-Stalin triumvirate collapsed in April 1925, although the political situation was hanging in the balance for the rest of the year. All sides spent most of 1925 lining up support behind the scenes for the December Communist Party Congress. Stalin struck an alliance with

During this time Kamenev wrote a letter to Stalin, saying:

During this time Kamenev wrote a letter to Stalin, saying:

online

*

excerpt

* Lih, Lars T. "Fully Armed: Kamenev and Pravda in March 1917." ''The NEP Era: Soviet Russia 1921–1928,'' 8 (2014), 55–68(2014)

online

* Pipes, Richard. ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime'' (2011) * Pogorelskin, Alexis. "Kamenev and the Peasant Question: The Turn to Opposition, 1924–1925." ''Russian History'' 27.4 (2000): 381–395

online

* Rabinowitch, Alexander. '' Prelude to Revolution: The Petrograd Bolsheviks and the July 1917 Uprising'' (1968). * Volkogonov, Dmitri. ''Lenin. A New Biography'' (1994),

at Marxists.org

Examination of Kamenev

during his trial, 20 August 1936.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Kamenev, Lev 1883 births 1936 deaths Revolutionaries of the Russian Revolution Deaths by firearm in the Soviet Union Executed heads of state Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Great Purge victims from Russia Heads of state of the Soviet Union Old Bolsheviks Chairpersons of the Executive Committee of Mossovet Politicians from Moscow Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Revolutionaries of the Russian Revolution of 1905 Deputy heads of government of the Soviet Union Ministers of defence of the Soviet Union Soviet rehabilitations Treaty of Brest-Litovsk negotiators Trial of the Sixteen (Great Purge) Members of the Orgburo of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 9th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Politburo of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 9th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Russian socialists Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Left Opposition Russian Marxists Russian people of Jewish descent Soviet show trials Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Italy People executed by the Soviet Union by firing squad Jewish Soviet politicians

Old Bolshevik

The Old Bolsheviks (), also called the Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, were members of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Many Old Bolsheviks became leading politi ...

, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a deputy premier of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

from 1923 to 1926.

Born in Moscow to a family active in revolutionary politics, Kamenev joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

in 1901 and sided with Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

's Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

faction after the party's 1903 split. He was arrested several times and participated in the failed Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, after which he moved abroad and became one of Lenin's close associates. In 1914, he was arrested upon returning to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

and exiled to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. He returned after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

of 1917, which overthrew the monarchy, and joined Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

in opposing Lenin's "April Theses

The April Theses (, transliteration: ') were a series of ten directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his April 1917 return to Petrograd from his exile in Switzerland via Germany and Finland. The theses were mostly aimed at ...

" and the armed seizure of power known as the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. Nevertheless, he briefly served as the ''de facto'' head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

as chairman of the he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...All-Russian Congress of Soviets

The All-Russian Congress of Soviets evolved from 1917 to become the supreme governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1918 until 1936, effectively. The 1918 Constitution of the Russian SFSR mandated that Congress s ...

and held a number of senior posts, including chairman of the Moscow Soviet and a deputy premier under Lenin. In 1919, Kamenev was elected as a full member of the first Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

.

During Lenin's final illness in 1923–1924, Kamenev formed a leadership troika

Troika or troyka (from Russian тройка, meaning 'a set of three' or the digit '3') may refer to:

* Troika (driving), a traditional Russian harness driving combination, a cultural icon of Russia

Politics

* Triumvirate, a political regime rul ...

with Zinoviev and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

which led to Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

's downfall. Stalin subsequently turned against his former allies and ousted Kamenev from the Soviet leadership, after which Kamenev and Zinoviev aligned with Trotsky in the United Opposition against Stalin. Kamenev was removed from his positions in 1926 and expelled from the party in 1927, before submitting to Stalin's increasing power and rejoining the party the next year. He and Zinoviev were again expelled from the party in 1932, as a result of the Ryutin affair, and were re-admitted in 1933.

In 1934, Kamenev was arrested after the assassination of Sergei Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (born Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Russian and Soviet politician and Bolsheviks, Bolshevik revolutionary. Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and a member of the Bolshevik faction ...

, accused of complicity in his killing, and sentenced to ten years in prison. He was later made a chief defendant in the Trial of the Sixteen

The Trial of the Sixteen () was a staged trial of 16 leaders of the Polish Underground State held by the Soviet authorities in Moscow in 1945. All captives were kidnapped by the NKVD secret service and falsely accused of various forms of 'ille ...

(the show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

at the beginning of Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

), found guilty of treason, and executed in August 1936.

Early life and career

Kamenev was born as Lev Borisovich Rozenfeld in Moscow to aJewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

father and a Russian Orthodox

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

mother. Both his parents were active in radical politics. His father, an engine driver on the Moscow-Kursk railway, had been a fellow student of Ignacy Hryniewiecki, the revolutionary who killed the Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

Alexander II. When Kamenev was a child, his family moved to Vilno

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

, and then in 1896, to Tiflis (known as Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

after 1936), where he first made contact with an illegal Marxist circle. His father used the capital he earned in the construction of the Baku

Baku (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Azerbaijan, largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus region. Baku is below sea level, which makes it the List of capital ci ...

–Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ), historically Batum or Batoum, is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second-largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast ...

railway to pay for Lev's education. Kamenev attended the boys' Gymnasium in Tiflis. In 1900, he enrolled as law student in Imperial Moscow University

Imperial Moscow University () was one of the oldest universities of the Russian Empire, established in 1755. It was the first of the twelve imperial universities of the Russian Empire. Its legacy is continued as Lomonosov Moscow State Universit ...

. He joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

(RSDLP) in 1901, and was arrested in March 1902 for taking part in a student protest, and, after a few months in prison, was sent back to Tiflis under police escort. Later in 1902, he moved to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, where he met Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, whose adherent and close associate he became, other Marxist exiles from the ''Iskra'' group that published the newspaper, and his wife, Olga Bronstein, younger sister of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

. The couple had two sons together.

From that point on, Kamenev worked as a professional revolutionary and was active in the capitals of St. Petersburg, Moscow and Tiflis. In January 1904, he was forced to leave Tiflis, where he had helped organise a strike on the Transcaucasian railway, and moved to Moscow, where he learnt about the split between the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

and Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

factions, and joined the Bolsheviks. Arrested in February 1904, he was held in prison for five months, then deported back to Tiflis, where he joined the local Bolshevik committee, working alongside Georgian Bolsheviks, including Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. After attending the 3rd Congress of the RSDLP in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in March 1905, he returned to Russia to participate in the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

in St. Petersburg in October–December.

He went back to London to attend the 5th RSDLP Party Congress, where he was elected to the party's Central Committee and the Bolshevik Center, in May 1907, but was arrested upon his return to Russia. After Kamenev was released from prison in 1908, he and his family went abroad later in the year to help Lenin edit the Bolshevik magazine ''Proletariy

Proletariy () is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) in Novgorodsky District of Novgorod Oblast, Russia, located at the Nisha River close to its mouth, east of Veliky Novgorod. Municipally, it is incorporated as Proletarskoye Urban Set ...

.'' After Lenin's split with another senior Bolshevik leader, Alexander Bogdanov

Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (; – 7 April 1928), born Alexander Malinovsky, was a Russian and later Soviet physician, philosopher, science fiction writer and Bolshevik revolutionary. He was a polymath who pioneered blood transfusion, a ...

, in mid-1908, Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

became Lenin's main assistants abroad. They helped him expel Bogdanov and his Otzovist In the course of the history of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP between 1898 and 1918), several political factions developed, as well as the major split between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks.

*Bolsheviks, formed in 1903 from ...

( Recallist) followers from the Bolshevik faction of the RSDLP in mid-1909.

In January 1910, Leninists

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the estab ...

, followers of Bogdanov, and various Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

factions held a meeting of the party's Central Committee in Paris and tried to reunite the party. Kamenev and Zinoviev were dubious about the idea but were willing to give it a try under pressure from "conciliator" Bolsheviks like Victor Nogin

Viktor Pavlovich Nogin (; 14 February O.S. 2 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 2 February1878 – 22 May 1924) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet Union, Soviet politician ...

. Lenin was adamantly opposed to re-unification, but was outvoted within the Bolshevik leadership. The meeting reached a tentative agreement. As one of its provisions, Trotsky's Vienna-based ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' was designated as a party-financed 'central organ'. In this process, Kamenev, Trotsky's brother-in-law, was added to Pravda's editorial board as a representative of the Bolsheviks. The unification attempts failed in August 1910, when Kamenev resigned from the board amid mutual recriminations.

After the failure of the reunification attempt, Kamenev continued working for ''Proletariy'' and taught at the Bolshevik party school at Longjumeau near Paris. It had been founded as a Leninist alternative to Bogdanov's Party School

Party school is a term primarily used in the United States to refer to a college or university that has a reputation for alcohol and drug use or a general culture of partying usually at the expense of educational achievement. The Princeton Review ...

based in Capri

Capri ( , ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. A popular resort destination since the time of the Roman Republic, its natural beauty ...

. In January 1912, Kamenev helped Lenin and Zinoviev to convince the Prague Conference of Bolshevik delegates to split from the Mensheviks and Otzovists.

In January 1914, he was sent to St. Petersburg to direct the work of the Bolshevik version of ''Pravda'' and the Bolshevik faction of the Duma

A duma () is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were formed across Russia ...

. He moved to Finland when Pravda was closed, in July 1914, and was there when World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out. He organised a conference in Finland Bolshevik delegates to the Duma and others, but all the participants were arrested in November tried in May 1915. In court, he distanced himself from Lenin's anti-war stance. In early 1915, Kamenev was sentenced to exile in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

; he survived two years there until being freed by the successful February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

of 1917.

Before leaving Siberia, Kamenev proposed sending a telegram thanking the Tsar's brother Mikhail for refusing the throne. He was so embarrassed later by his action that he denied ever having sent it.

On 25 March 1917, Kamenev returned from Siberian exile to St. Petersburg (renamed as

On 25 March 1917, Kamenev returned from Siberian exile to St. Petersburg (renamed as Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

in 1914). Kamenev and Central Committee members Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and Matvei Muranov

Matvei Konstantinovich Muranov (; 11 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/> O.S. 29 November1873 – 9 December 1959) was a Ukrainian Bolshevik">Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 29 November1873 – 9 December 19 ...

took control of the revived Bolshevik ''Pravda'' and moved it to the Right. Kamenev formulated a policy of conditional support of the newly formed Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

and a reconciliation with the Mensheviks. After Lenin's return to Russia on 3 April 1917, Kamenev briefly resisted Lenin's anti-government April Theses

The April Theses (, transliteration: ') were a series of ten directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his April 1917 return to Petrograd from his exile in Switzerland via Germany and Finland. The theses were mostly aimed at ...

but soon fell in line and supported Lenin until September.

Kamenev and Zinoviev had a falling out with Lenin over their opposition to the Soviet seizure of power in October 1917. On 10 October 1917 (Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, they refer to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries betwe ...

), Kamenev and Zinoviev were the only two Central Committee members to vote against an armed revolt. Their publication of an open letter opposed to using force enraged Lenin, who demanded their expulsion from the party. However, when the Bolshevik-led Military Revolutionary Committee

The Military Revolutionary Committee (Milrevcom; , ) was the name for military organs created by the Bolsheviks under the soviets in preparation for the October Revolution (October 1917 – March 1918).

, headed by Adolph Joffe

Adolph Abramovich Joffe (; alternatively transliterated as Adolf Ioffe or Yoffe; 10 October 1883 – 16 November 1927) was a Russian revolutionary, Bolshevik politician and Soviet diplomat of Karaite descent.

Biography Revolutionary career ...

, and the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (, ''Petrogradsky soviet rabochih i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of Petrograd (Saint Petersburg), the capital of Russia at the time. For brevity, it is usually called the Pet ...

, led by Trotsky, staged an uprising, Kamenev and Zinoviev went along. At the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets

The Congress of Soviets was the supreme governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and several other Soviet republics and national autonomies in the Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1936 and a somewhat simil ...

, Kamenev was elected Congress Chairman and chairman of the permanent All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee () was (June – November 1917) a permanent body formed by the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (held from June 16 to July 7, 1917 in Petrograd), then became the ...

. The latter position was equivalent to the head of state under the Soviet system.

On 10 November 1917, three days after the Soviet seizure of power during the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, the executive committee of the national railroad labor union, '' Vikzhel'', threatened a nationwide strike unless the Bolsheviks shared power with other socialist parties and dropped the uprising's leaders, Lenin and Trotsky, from the government. Zinoviev, Kamenev and their allies in the Bolshevik Central Committee argued that the Bolsheviks had no choice but to start negotiations, since a railroad strike would cripple their government's ability to fight the forces that were still loyal to the overthrown Provisional Government. Although Zinoviev and Kamenev briefly had the support of a Central Committee majority and negotiations were started, a quick collapse of the anti-Bolshevik forces outside Petrograd aided Lenin and Trotsky to convince the Central Committee to abandon the negotiating process. In response, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Alexei Rykov

Alexei Ivanovich Rykov (25 February 188115 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician and statesman, most prominent as premier of Russia and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Soviet Union from 1924 to 1929 and 1924 t ...

, Vladimir Milyutin

Vladimir Pavlovich Milyutin (Russian: Влади́мир Па́влович Милю́тин; 5 September 1884 – 30 October 1937) was a Russian Bolshevik leader, Soviet statesman, economist, and statistician who was People's Commissar for Agricu ...

and Victor Nogin

Viktor Pavlovich Nogin (; 14 February O.S. 2 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 2 February1878 – 22 May 1924) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet Union, Soviet politician ...

resigned from the Central Committee on 4 November 1917 (Old Style) and Kamenev resigned from his Central Executive Committee post. The following day, Lenin wrote a proclamation calling Zinoviev and Kamenev "deserters." He never forgot their behavior, eventually making an ambiguous reference to their "October episode" in his Testament

A testament is a document that the author has sworn to be true. In law it usually means last will and testament.

Testament or The Testament can also refer to:

Books

* ''Testament'' (comic book), a 2005 comic book

* ''Testament'', a thriller no ...

.

In late 1917, Kamenev was sent to negotiate with Germany over the potential armistice at Brest-Litovsk

Brest, formerly Brest-Litovsk and Brest-on-the-Bug, is a city in south-western Belarus at the border with Poland opposite the Polish town of Terespol, where the Bug and Mukhavets rivers meet, making it a border town. It serves as the admini ...

, which finally came in the form of Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

. In January 1918, Kamenev was sent to spread the revolution to Britain and France and negotiate with the countries about the potential alliance in case Germany continued its offensive against the Bolshevik regime, but after he had been in London for a week, he was arrested and deported. On his return, via Finland, he was captured by Finnish partisans led by Hjalmar von Bonsdorff opposed to the Bolshevik revolution, and held until August 1918, when he was exchanged for Finnish prisoners held by the Bolsheviks.

Opposition to Trotsky

In 1918, Kamenev became chairman of the Moscow Soviet, and soon after that, Lenin'sDeputy Chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

of the Council of People's Commissars

The Council of People's Commissars (CPC) (), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (), were the highest executive (government), executive authorities of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the Soviet Union (USSR), and the Sovi ...

(government) and the Council of Labour and Defence

The Council of Labor and Defense ()Sovet truda i oborony, Latin acronym: STO), first established as the Council of Workers' and Peasants' Defense in November 1918, was an agency responsible for the central management of the economy and production ...

. In March 1919, Kamenev was elected a full member of the first Politburo. His relationship with his brother-in-law Trotsky, which was good in the aftermath of the 1917 revolution and during the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, lessened after 1920. For the next 15 years, Kamenev was a friend and close ally of Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

, whose ambition exceeded Kamenev's.

During Lenin's illness, Kamenev was appointed as the acting President of the Council of People's Commissars and Politburo chairman. Together with Zinoviev and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, he formed a ruling Triumvirate

A triumvirate () or a triarchy is a political institution ruled or dominated by three individuals, known as triumvirs (). The arrangement can be formal or informal. Though the three leaders in a triumvirate are notionally equal, the actual distr ...

(also known by its Russian name ''Troika

Troika or troyka (from Russian тройка, meaning 'a set of three' or the digit '3') may refer to:

* Troika (driving), a traditional Russian harness driving combination, a cultural icon of Russia

Politics

* Triumvirate, a political regime rul ...

'') in the Communist Party, and played a key role in the marginalization of Trotsky. The triumvirate carefully managed the intra-party debate and delegate selection process in the fall of 1923 during the run-up to the 13th Party Conference, securing a vast majority of the seats. The Conference, held in January 1924, immediately prior to Lenin's death, denounced Trotsky and "Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

."

In the spring of 1924, while the triumvirate was criticizing the policies of Trotsky and the Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

as "anti-Leninist", the tensions between the volatile Zinoviev and his close ally Kamenev on one hand, and the cautious Stalin on the other, became more pronounced and threatened to end their fragile alliance. However, Zinoviev and Kamenev helped Stalin retain his position as General Secretary of the Central Committee at the XIIIth Party Congress in May–June 1924 during the first Lenin's Testament

Lenin's Testament is a document alleged to have been dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923, during and after his suffering of multiple strokes. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bod ...

controversy, ensuring that the triumvirate gained more political advantage at Trotsky's expense.

In October 1924, Stalin proposed his new theory of Socialism in One Country in opposition to Trotsky's theory of

In October 1924, Stalin proposed his new theory of Socialism in One Country in opposition to Trotsky's theory of Permanent revolution

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and ...

, while Trotsky published " Lessons of October," an extensive summary of the events of 1917. In the article, Trotsky described Zinoviev and Kamenev's opposition to the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917, which the two would have preferred to be left unmentioned. This started a new round of intra-party struggle, with Zinoviev and Kamenev again allied with Stalin against Trotsky. They and their supporters accused Trotsky of various mistakes and worse during the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. Trotsky was ill and unable to respond much to the criticism, and the triumvirate damaged Trotsky's military reputation so much that he was forced out of his ministerial post as People's Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English language, English transliteration of the Russian language, Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the pol ...

of Army and Fleet Affairs and Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council

The Revolutionary Military Council (), sometimes called the Revolutionary War Council Brian PearceIntroductionto Fyodor Raskolnikov s "Tales of Sub-lieutenant Ilyin." or ''Revvoyensoviet'' (), was the supreme military authority of Soviet Rus ...

in January 1925. Zinoviev demanded Trotsky's expulsion from the Communist Party, but Stalin refused to go along with this and skillfully played the role of a moderate.

At the 14th Conference of the Communist Party in April 1925, Zinoviev and Kamenev found themselves in a minority when their motion to specify that socialism could only be achieved internationally was rejected, resulting in the triumvirate of recent years breaking up. At this time, Stalin was moving more and more into a political alliance with Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

and the Right Opposition

The Right Opposition () or Right Tendency () in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a label formulated by Joseph Stalin in Autumn of 1928 for the opposition against certain measures included within the first five-year plan, an oppos ...

, with Bukharin having elaborated on Stalin's ''Socialism in One Country'' policy, giving it a theoretical justification.

One of Kamenev's last public acts while he was still a major figure in the soviet leadership was to read the story '' The Heart of a Dog'', by Mikhail Bulgakov

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov ( ; rus, links=no, Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ɐfɐˈnasʲjɪvʲɪdʑ bʊlˈɡakəf; – 10 March 1940) was a Russian and Soviet novelist and playwright. His novel ''The M ...

. He denounced it, saying "It's an acerbic broadside about the present age, and there can be absolutely no question of publishing it." The story was banned in the Soviet Union until 1987.

According to Polish historian, Marian Kamil Dziewanowski, Kamenev was denied the position of Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union

The Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union was the Premier of the Soviet Union, head of government of the Soviet Union during the existence of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union from 1923 to 1946.

...

on Stalin's suggestion due to his Jewish origins. Stalin favoured Alexei Rykov

Alexei Ivanovich Rykov (25 February 188115 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician and statesman, most prominent as premier of Russia and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Soviet Union from 1924 to 1929 and 1924 t ...

and placed him in the position due to his Russian, peasant background. Conversely, Russian historian Roy Medvedev

Roy Aleksandrovich Medvedev (; born 14 November 1925) is a Russian politician and writer. He is the author of the dissident history of Stalinism, ''Let History Judge'' (), first published in English in 1972.

Biography

Medvedev was born to ...

stated that Trotsky "undoubtedly would have been first among Lenin's deputies" given his authority

Authority is commonly understood as the legitimate power of a person or group of other people.

In a civil state, ''authority'' may be practiced by legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government,''The New Fontana Dictionary of M ...

in 1922 and noted that Kamenev lacked any personal desire to become Chairman upon Lenin's death.

Break with Stalin (1925)

With Trotsky mainly on the sidelines through a persistent illness, the Zinoviev-Kamenev-Stalin triumvirate collapsed in April 1925, although the political situation was hanging in the balance for the rest of the year. All sides spent most of 1925 lining up support behind the scenes for the December Communist Party Congress. Stalin struck an alliance with

With Trotsky mainly on the sidelines through a persistent illness, the Zinoviev-Kamenev-Stalin triumvirate collapsed in April 1925, although the political situation was hanging in the balance for the rest of the year. All sides spent most of 1925 lining up support behind the scenes for the December Communist Party Congress. Stalin struck an alliance with Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

, a Communist Party theoretician and ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' editor, and the Soviet prime minister Alexei Rykov

Alexei Ivanovich Rykov (25 February 188115 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician and statesman, most prominent as premier of Russia and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Soviet Union from 1924 to 1929 and 1924 t ...

. Zinoviev and Kamenev strengthened their alliance with Lenin's widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya ( rus, links=no, Надежда Константиновна Крупская, p=nɐˈdʲeʐdə kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvnə ˈkrupskəjə; – 27 February 1939) was a Russian revolutionary, politician and politic ...

. Also, they aligned with Grigori Sokolnikov

Grigori Yakovlevich Sokolnikov (born Hirsch Yankelevich Brilliant; 15 August 1888 – 21 May 1939) was a Russian revolutionary, economist, and Soviet politician.

Born to a Jewish family in Romny (now in Ukraine), Sokolnikov joined the Russian S ...

, the People's Commissar for Finance

The Ministry of Finance of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (), formed on 15 March 1946, was one of the most important government offices in the Soviet Union. Until 1946 it was known as the People's Commissariat for Finance ( – ''N ...

and a candidate Politburo member. Their alliance became known as the New Opposition.

The struggle became more open at the September 1925 meeting of the Central Committee, and came to a head at the XIVth Party Congress in December 1925, when Kamenev publicly demanded the removal of Stalin from the position of the General Secretary. With only the Leningrad delegation (controlled by Zinoviev) behind them, Zinoviev and Kamenev found themselves in a tiny minority and were soundly defeated. Trotsky remained silent during the Congress. Zinoviev was re-elected to the Politburo, but Kamenev was demoted from a full member to a non-voting member, and Sokolnikov was dropped altogether. Stalin succeeded in having more of his allies elected to the Politburo.

Opposition to Stalin (1926–1927)

In early 1926, Zinoviev, Kamenev and their supporters gravitated closer to Trotsky's supporters, with the two groups allying, which became known as the United Opposition. During a new period of intra-party fighting between the July 1926 meeting of the Central Committee and the XVth Party Conference in October 1926, the United Opposition was defeated, and Kamenev lost his Politburo seat at the Conference. Kamenev continued to oppose Stalin throughout 1926 and 1927, resulting in his expulsion from the Central Committee in October 1927. After the expulsion of Zinoviev and Trotsky from the Communist Party on 12 November 1927, Kamenev was the United Opposition's chief spokesman within the Party, representing its position at the XVth Party Congress in December 1927. Kamenev used the occasion to appeal for reconciliation among the groups. His speech was interrupted 24 times by his opponents – Bukharin, Ryutin, and Kaganovich, making it clear that Kamenev's attempts were futile.Lewis H. Siegelbaum, ''Soviet State and Society Between Revolutions, 1918–1929'',Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, 1992, p.189–190. The Congress declared United Opposition views incompatible with Communist Party membership; it expelled Kamenev and dozens of leading Oppositionists from the Party. This paved the way for mass expulsions in 1928 of rank-and-file Oppositionists, as well as sending prominent Left Oppositionists into internal exile.

Kamenev's first marriage, which had begun to disintegrate in 1920, as a result of his reputed affair with the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

Clare Sheridan

Clare Consuelo Sheridan (née Frewen; 9 September 1885 – 31 May 1970) was an English sculptor, journalist and writer, known primarily for creating busts for famous sitters and keeping travel diaries. She was a cousin of Sir Winston Churchill ...

, ended in divorce in 1928 when he left Olga Kameneva

Olga Davidovna Kameneva (, ; – 11 September 1941) (née Bronstein — Бронште́йн) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician. She was the sister of Leon Trotsky and the wife of Lev Kamenev.

Childhood and revolutio ...

and married Tatiana Glebova. They had a son together, Vladimir Glebov (1929–1994).See Michael Parrish. ''The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939–1953'', Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1996, p. 69.

Submission to Stalin and execution

While Trotsky remained firm in his opposition to Stalin after his expulsion from the Party and subsequent exile, Zinoviev and Kamenev capitulated almost immediately and called on their supporters to follow suit. They wrote open letters acknowledging their mistakes and were readmitted to the Communist Party after a six-month cooling-off period. They never regained their Central Committee seats but were given mid-level positions within theSoviet bureaucracy The Soviet bureaucracy played a crucial role in the governance and administration of the USSR. A class of high-ranking party bureaucrats, known as the ''nomenklatura'', formed a ''de facto'' elite, wielding immense power over public life.

History ...

. Kamenev and, indirectly, Zinoviev, were courted by Bukharin, then at the beginning of his short and ill-fated struggle with Stalin, in the summer of 1928. This activity was soon reported to Joseph Stalin and used against Bukharin as proof of his factionalism.

Zinoviev and Kamenev remained politically inactive until October 1932, when they were expelled from the Communist Party, after receiving an oppositionist group's appeal but not informing the party of their activities during the Ryutin Affair. After again admitting their alleged errors, they were readmitted in December 1933. They were forced to make self-flagellating speeches at the 17th Party Congress in January 1934, where Stalin paraded his erstwhile political opponents, showing them to be defeated and outwardly contrite.

The murder of Sergei Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (born Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Russian and Soviet politician and Bolsheviks, Bolshevik revolutionary. Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and a member of the Bolshevik faction ...

on 1 December 1934 was a catalyst for what are called Stalin's Great Purges

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the assassination of Sergei Kirov by Leonid Nikolaev ...

, as he initiated show trials and executions of opponents. Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

, Kamenev and their closest associates were again expelled from the Communist Party and arrested.

During this time Kamenev wrote a letter to Stalin, saying:

During this time Kamenev wrote a letter to Stalin, saying:

At a time when my soul is filled with nothing but love for the party and its leadership, when, having lived through hesitations and doubts, I can boldly say that I learned to highly trust the Central Committee's every step and every decision you, Comrade Stalin, make. I have been arrested for my ties to people who are strange and disgusting to me.The men were tried in January 1935 and were forced to admit "moral complicity" in Kirov's assassination. Zinoviev was sentenced to ten years in prison and Kamenev to five. After the sentence the writer

Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (; ), was a Russian and Soviet writer and proponent of socialism. He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Before his success as an aut ...

pleaded with Stalin for Kamenev's release, but was ignored. Kamenev was charged separately in early 1935 in connection with the Kremlin Affair, in which his nephew Nikolai Rosenfeld, a Moscow thermal power engineer, was involved as a major participant. Although he refused to confess, he was sentenced to ten years in prison. In August 1936, after months of rehearsal in Soviet secret police prisons, Zinoviev, Kamenev and 14 others, mostly Old Bolshevik

The Old Bolsheviks (), also called the Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, were members of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Many Old Bolsheviks became leading politi ...

s, were put on trial again. This time, the charges included forming a terrorist organization that killed Kirov and tried to kill Stalin and other leaders of the Soviet government. This Trial of the Sixteen

The Trial of the Sixteen () was a staged trial of 16 leaders of the Polish Underground State held by the Soviet authorities in Moscow in 1945. All captives were kidnapped by the NKVD secret service and falsely accused of various forms of 'ille ...

was one of the Moscow Show Trials and set the stage for subsequent show trials. Old Bolsheviks were forced to confess increasingly elaborate and monstrous crimes, including espionage, poisoning and sabotage. Like the other defendants, Kamenev was found guilty and executed by firing squad on 25 August 1936. The fate of his body is unknown. In 1988, during perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

, Kamenev, Zinoviev and his co-defendants were formally rehabilitated by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union

The Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union () was created in 1924 by the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union as a court for the higher military and political personnel of the Red Army and Fleet. In addition it was an immedia ...

.

Fate of the family

After Kamenev's execution, his relatives suffered similar fates. Kamenev's second son, Yu. L. Kamenev was executed on 30 January 1938, at the age of 17. His eldest son,Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

officer A.L. Kamenev, was executed on 15 July 1939 at 33. His first wife, Olga

Olga may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Olga (name), a given name, including a list of people and fictional characters named Olga or Olha

* Michael Algar (born 1962), English singer also known as "Olga"

Places

Russia

* Olga, Russia ...

, was executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

on 11 September 1941, in the Medvedev forest outside Oryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, , ɐˈrʲɵl, a=ru-Орёл.ogg, links=y, ), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a Classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, situated on the Oka Rive ...

, together with Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgiyevich Rakovsky ( – September 11, 1941), Bulgarian name Krastyo Georgiev Rakovski, born Krastyo Georgiev Stanchov, was a Bulgarian-born socialist Professional revolutionaries, revolutionary, a Bolshevik politician and Soviet Un ...

, Maria Spiridonova

Maria Alexandrovna Spiridonova (; 16 October 1884 – 11 September 1941) was a Narodnik-inspired Russian revolutionary. In 1906, as a novice member of a local combat group of the Tambov Socialists-Revolutionaries (SRs), she assassinated a securi ...

, and 160 other prominent political prisoners. Only his youngest son, Vladimir Glebov, survived Stalin's prisons and labor camps

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

, living until 1994.Geert Mak, ''In Europa,'' 2009. Episode "1933, Russia"

Notes

References

Further reading

* Corney, Frederick C., ed. ''Trotsky's Challenge: The "Literary Discussion" of 1924 and the Fight for the Bolshevik Revolution.'' (Chicago:Haymarket Books

Haymarket Books is an American non-profit, independent book publisher based in Chicago and emphasizing works on left-wing politics.

History

Haymarket Books was founded in 2001 by Anthony Arnove, Ahmed Shawki and Julie Fain, all of whom had ...

, 2017).

* Debo, Richard Kent. "Litvinov and Kamenev—Ambassadors Extraordinary: The Problem of Soviet Representation Abroad." ''Slavic Review'' 34.3 (1975): 463–482.online

*

Isaac Deutscher

Isaac Deutscher (; 3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of World War II. He is best known as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph S ...

. ''Stalin: a Political Biography'' (1949)

* Isaac Deutscher

Isaac Deutscher (; 3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of World War II. He is best known as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph S ...

. ''The Prophet Armed: Trotsky, 1879–1921'' (1954)

* Isaac Deutscher

Isaac Deutscher (; 3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of World War II. He is best known as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph S ...

. ''The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky, 1921–1929'' (1959)

* Haupt, Georges, and Jean-Jacques Marie. ''Makers of the Russian Revolution: Biographies'' (Routledge, 2017).

* Kotkin, Stephen. ''Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928'' (2015excerpt

* Lih, Lars T. "Fully Armed: Kamenev and Pravda in March 1917." ''The NEP Era: Soviet Russia 1921–1928,'' 8 (2014), 55–68(2014)

online

* Pipes, Richard. ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime'' (2011) * Pogorelskin, Alexis. "Kamenev and the Peasant Question: The Turn to Opposition, 1924–1925." ''Russian History'' 27.4 (2000): 381–395

online

* Rabinowitch, Alexander. '' Prelude to Revolution: The Petrograd Bolsheviks and the July 1917 Uprising'' (1968). * Volkogonov, Dmitri. ''Lenin. A New Biography'' (1994),

Other languages

* Ulrich, Jürg: ''Kamenew: Der gemäßigte Bolschewik. Das kollektive Denken im Umfeld Lenins.'' VSA Verlag, Hamburg 2006, . * ''"Unpersonen": Wer waren sie wirklich? Bucharin, Rykow, Trotzki, Sinowjew, Kamenew.'' Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1990, .External links

at Marxists.org

Examination of Kamenev

during his trial, 20 August 1936.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Kamenev, Lev 1883 births 1936 deaths Revolutionaries of the Russian Revolution Deaths by firearm in the Soviet Union Executed heads of state Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Great Purge victims from Russia Heads of state of the Soviet Union Old Bolsheviks Chairpersons of the Executive Committee of Mossovet Politicians from Moscow Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Revolutionaries of the Russian Revolution of 1905 Deputy heads of government of the Soviet Union Ministers of defence of the Soviet Union Soviet rehabilitations Treaty of Brest-Litovsk negotiators Trial of the Sixteen (Great Purge) Members of the Orgburo of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 9th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Politburo of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 9th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Russian socialists Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Left Opposition Russian Marxists Russian people of Jewish descent Soviet show trials Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Italy People executed by the Soviet Union by firing squad Jewish Soviet politicians