Late Settings on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Ingram Merrill (March 3, 1926 – February 6, 1995) was an American poet. He was awarded the

, ''San Francisco Examiner'', 6 April 2001. Retrieved 16 June 2013. and Charles E. Merrill, Jr. As a boy, Merrill enjoyed a highly privileged upbringing in educational and economic terms. His father's 30-acre estate in

3D aerial view of "The Orchard"

Hill St., Southampton, New York.J. D. McClatchy

''The New Yorker'', 27 March 1995. Merrill's childhood governess taught him French and German, an experience Merrill wrote about in his 1974 poem '' Lost in Translation''. From 1936 to 1938, Merrill attended St. Bernard's, a prestigious New York grammar school. "I found it difficult to ''believe'' in the way my parents lived. They seemed so utterly taken up with engagements, obligations, ceremonies," Merrill would tell an interviewer in 1982.J. D. McClatchy, interviewer

The Art of Poetry No. 31: An Interview with James Merrill

''Paris Review'', Summer 1982. "The excitement, the emotional quickening I felt in those years came usually through animals or nature, or through the servants in the house ... whose lives seemed by contrast to make such perfect ''sense''. The gardeners had their hands in the earth. The cook was dredging things with flour, making pies. My father was merely making money, while my mother wrote names on place-cards, planned menus, and did her needlepoint." Merrill's parents separated when he was eleven, then divorced when he was thirteen. As a teenager, Merrill boarded at the

Merrill's partner of three decades was

Merrill's partner of three decades was

The View From/Stonington; If the Walls Could Talk, It Would Be Poetry

Days of 1973: A Week in Athens

''Notre Dame Review'', Summer/Fall 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2013. Greek themes, locales, and characters occupy a prominent position in Merrill's writing. In 1979, Merrill and Jackson largely abandoned Greece and began spending part of each year at Jackson's home in In his 1993 memoir ''A Different Person'', Merrill revealed that he suffered

In his 1993 memoir ''A Different Person'', Merrill revealed that he suffered

“The Mad Scene”

''The New Yorker'', March 19, 1995. The poem originally appeared in

Poetry Magazine

' in October/November 1962, and in the collection ''Water Street'' (Atheneum).

including the 1977

(With acceptance speech by Merrill and essay by Megan Snyder-Camp from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) and in 1979 for '' Mirabell: Books of Number''."National Book Awards – 1979"

National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-03. He was elected a Fellow of the

The Magician: Collected Poems by James Merrill

''Los Angeles Times'', 4 March 2001. Retrieved 14 June 2013. Already established in the 1970s among the finest poets of his generation, Merrill made a surprising detour when he began incorporating extensive

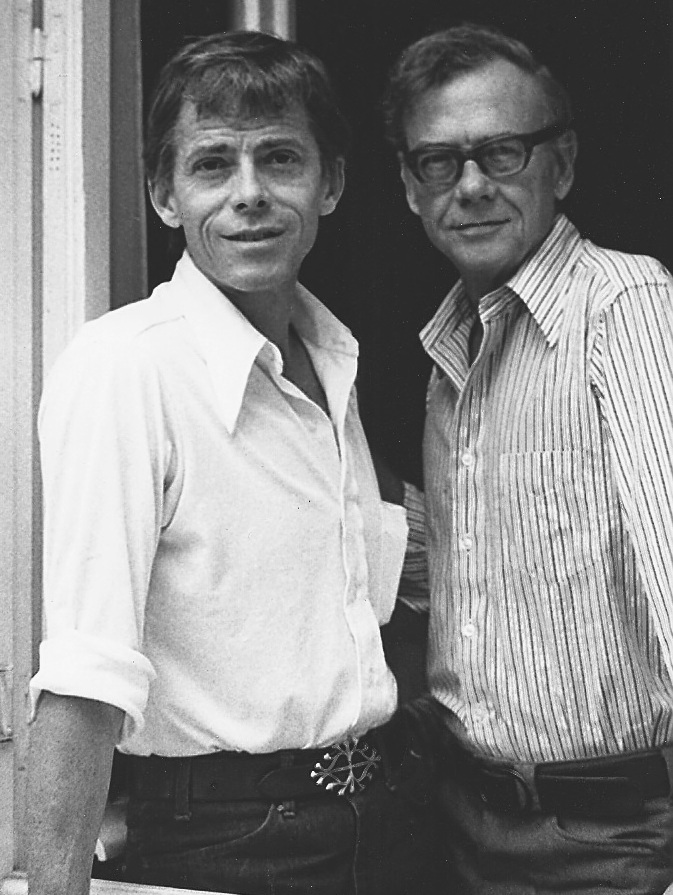

James Merrill in Iowa City, October 1992

. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

File:James Merrill House, Stonington, CT, 2.jpg, James Merrill House, Stonington, Connecticut

File:James Merrill and David Jackson House, Key West, FL.jpg, James Merrill and David Jackson House, Key West, Florida

File:Evergreen Cemetery, Stonington, CT.jpg, Jackson and Merrill graves, Evergreen Cemetery, Stonington, Connecticut

'James Merrill House and Its Disembodied Transmissions'

in ''Cordite Poetry Review''

The James Merrill Digital Archive: Materials for ''The Book of Ephraim''

* * James Merrill Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. * Stephen Yenser Papers Relating to James Merrill. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

James Merrill House Museum & Writer-in-Residence ProgramStuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

James Ingram Merrill collection, 1923-2000

*Materials related to James Merrill in th

Robert A. Wilson collection

held b

Special Collections, University of DelawareJames I. Merrill (AC 1947) and William S. Burford (AC 1949) Correspondence

at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Merrill-Magowan Family Papers

at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Jack W.C. Hagstrom (AC 1955) James I. Merrill Bibliography Papers

at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections {{DEFAULTSORT:Merrill, James 1926 births 1995 deaths 20th-century American poets AIDS-related deaths in Arizona 20th-century American memoirists United States Army personnel of World War II Amherst College alumni Bollingen Prize recipients Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Formalist poets American gay writers Glascock Prize winners Lawrenceville School alumni American LGBTQ poets LGBTQ people from New York (state) National Book Award winners Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winners United States Army soldiers Poets from New York City American male poets 20th-century American male writers American male non-fiction writers Merrill family Military personnel from New York City Gay poets

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

for poetry in 1977 for ''Divine Comedies

{{italic title

''Divine Comedies'' is the seventh book of poetry by James Merrill (1926–1995). Published in 1976 (see 1976 in poetry), the volume includes " Lost in Translation" and all of ''The Book of Ephraim''. ''The Book of Ephraim'' is ...

.'' His poetry falls into two distinct bodies of work: the polished and formalist lyric poetry of his early career, and the epic narrative of occult communication with spirits and angels, titled ''The Changing Light at Sandover

''The Changing Light at Sandover'' is a 560-page epic poem by James Merrill (1926–1995). Sometimes described as a postmodern apocalyptic epic, the poem was published in three volumes from 1976 to 1980, and as one volume "with a new coda" ...

'' (published in three volumes from 1976 to 1980), which dominated his later career. Although most of his published work was poetry, he also wrote essays, fiction, and plays.

Early life

James Ingram Merrill was born in New York City, toCharles E. Merrill

Charles Edward Merrill (October 19, 1885 – October 6, 1956) was an American philanthropist, stockbroker, and co-founder, with Edmund C. Lynch, of Merrill Lynch (previously called Charles E. Merrill & Co.).

Early years

Charles E. Merrill, th ...

(1885–1956), the founding partner of the Merrill Lynch

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated, doing business as Merrill, and previously branded Merrill Lynch, is an American investment management and wealth management division of Bank of America. Along with BofA Securities, the investm ...

investment firm, and Hellen Ingram Merrill (1898–2000), a society reporter and publisher from Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

. He was born at a residence which would become the site of the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion

The Greenwich Village townhouse explosion occurred on March 6, 1970, in New York City, United States. Members of the Weather Underground (Weathermen), an American leftist militant group, were making bombs in the basement of 18 West 11th Street ...

, which Merrill would lament in the poem "18 West 11th Street

Eighteen or 18 may refer to:

* 18 (number)

* One of the years 18 BC, AD 18, 1918, 2018

Film, television and entertainment

* ''18'' (film), a 1993 Taiwanese experimental film based on the short story ''God's Dice''

* ''Eighteen'' (film), a 20 ...

" (1972).

Merrill's parents married in 1925, the year before he was born; he would grow up with two older half siblings from his father's first marriage, Doris Merrill MagowanPhilanthropist Doris Magowan dies at 87, ''San Francisco Examiner'', 6 April 2001. Retrieved 16 June 2013. and Charles E. Merrill, Jr. As a boy, Merrill enjoyed a highly privileged upbringing in educational and economic terms. His father's 30-acre estate in

Southampton, New York

Southampton, officially the Town of Southampton, is a town in southeastern Suffolk County, New York, partly on the South Fork of Long Island. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the town had a population of 69,036. Southampton is included in the stre ...

, for example, known as " The Orchard," had been designed by Stanford White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect and a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms at the turn of the 20th century. White designed many houses ...

with landscaping by Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, Social criticism, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the U ...

. (The property was developed in 1980 with 29 luxury condominiums flanking the central gardens, while the home's vast ballroom and first-floor public reception areas were preserved.)Bing.com3D aerial view of "The Orchard"

Hill St., Southampton, New York.J. D. McClatchy

''The New Yorker'', 27 March 1995. Merrill's childhood governess taught him French and German, an experience Merrill wrote about in his 1974 poem '' Lost in Translation''. From 1936 to 1938, Merrill attended St. Bernard's, a prestigious New York grammar school. "I found it difficult to ''believe'' in the way my parents lived. They seemed so utterly taken up with engagements, obligations, ceremonies," Merrill would tell an interviewer in 1982.J. D. McClatchy, interviewer

The Art of Poetry No. 31: An Interview with James Merrill

''Paris Review'', Summer 1982. "The excitement, the emotional quickening I felt in those years came usually through animals or nature, or through the servants in the house ... whose lives seemed by contrast to make such perfect ''sense''. The gardeners had their hands in the earth. The cook was dredging things with flour, making pies. My father was merely making money, while my mother wrote names on place-cards, planned menus, and did her needlepoint." Merrill's parents separated when he was eleven, then divorced when he was thirteen. As a teenager, Merrill boarded at the

Lawrenceville School

The Lawrenceville School is a Private school, private, coeducational College-preparatory school, preparatory school for boarding and day students located in the Local government in New Jersey, unincorporated community of Lawrenceville, New Jers ...

, where he befriended future novelist Frederick Buechner

Carl Frederick Buechner ( ; July 11, 1926 – August 15, 2022) was an American author, Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies ...

, began writing poetry, and undertook early literary collaborations. When Merrill was 16 years old, his father collected his short stories and poems and published them as a surprise under the name ''Jim's Book.'' Initially pleased, Merrill would later regard the precocious book as an embarrassment. Today, copies are considered literary treasures worth thousands of dollars.

''The Black Swan''

Merrill was drafted in 1944 into theUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and served for eight months. His studies interrupted by war and military service, Merrill returned to Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zepha ...

in 1945 and graduated ''summa cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sout ...

'' and Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

in 1947. Merrill's senior thesis on French novelist Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust ( ; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the novel (in French – translated in English as ''Remembrance of Things Past'' and more r ...

heralded his literary talent, and his English professor upon reading it declared to the Amherst graduating class that Jim (as he was known there) was "destined for some sort of greatness." ''The Black Swan'', a collection of poems Merrill's Amherst professor (and lover) Kimon Friar

Kimon Friar (April 8, 1911 – May 25, 1993) was a Greek-American poet and translator of Greek poetry.

Youth and education

Friar was born in 1911 in İmralı, Ottoman Empire (now modern day Turkey), to a Greek father and a Greek mother. In 1915 ...

published privately in Athens, Greece, in 1946, was printed in just one hundred copies when Merrill was 20 years old. Merrill's first mature work, ''The Black Swan'' is among Merrill's scarcest titles. Merrill's first commercially published volume was ''First Poems'', issued in 990 numbered copies by Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

in 1951.

''A Different Person''

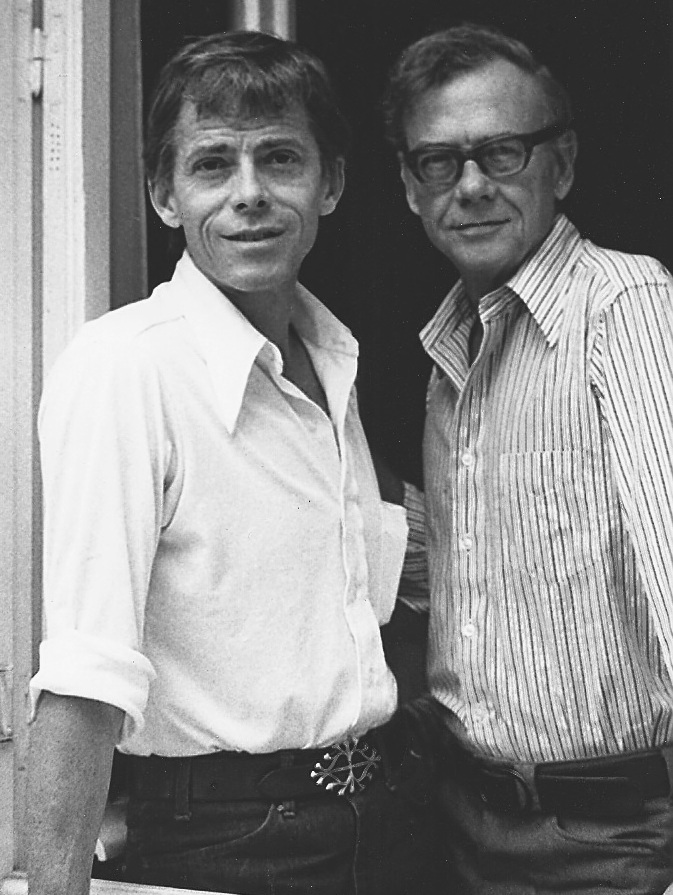

Merrill's partner of three decades was

Merrill's partner of three decades was David Jackson David Jackson or Dave Jackson may refer to:

Academics

*David Jackson (art historian) (born 1958), British professor of Russian and Scandinavian art histories

* David J. Jackson, American political scientist

* David M. Jackson, Canadian mathematics ...

, a writer and artist. Merrill and Jackson met in New York City after a performance of Merrill's play ''The Bait'' at the Comedy Club in 1953. (Poet Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer, whose works include the poems " Do not go gentle into that good night" and " And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Un ...

and playwright Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are '' All My Sons'' (1947), '' Death of a Salesman'' (1 ...

walked out of the performance.) Together, Jackson and Merrill moved to Stonington, Connecticut

Stonington is a town located on Long Island Sound in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The municipal limits of the town include the borough of Stonington (borough), Connecticut, Stonington, the villages of Pawcatuck, Connecticut, Pa ...

in 1955, purchasing a property at 107 Water Street (now the site of writer-in-residency program, the James Merrill House

The James Merrill House is a 19th-century late-Victorian style house at 107 Water Street in Stonington (borough), Connecticut, Stonington Borough in southeastern Connecticut, formerly owned by poet James Merrill. Upon his death in 1995, the hou ...

, which until 2024 was sponsored by the Stonington Village Improvement Association in Stonington Borough, and is now part of the James Merrill House Foundation).Swansburg, JohnThe View From/Stonington; If the Walls Could Talk, It Would Be Poetry

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

, 28 January 2001. " the 1950s he established the Ingram Merrill Foundation, which until it ceased to exist in 1996, gave grants to writers, artists and other foundations. By the mid-90s, Merrill was donating around $300,000 a year through the foundation." Retrieved 24 April 2013. For most of two decades, the couple spent winters in Athens at their home at 44 Athinaion Efivon.Moffett, JudithDays of 1973: A Week in Athens

''Notre Dame Review'', Summer/Fall 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2013. Greek themes, locales, and characters occupy a prominent position in Merrill's writing. In 1979, Merrill and Jackson largely abandoned Greece and began spending part of each year at Jackson's home in

Key West, Florida

Key West is an island in the Straits of Florida, at the southern end of the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Islan ...

.

In his 1993 memoir ''A Different Person'', Merrill revealed that he suffered

In his 1993 memoir ''A Different Person'', Merrill revealed that he suffered writer's block

Writer's block is a non-medical condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown.

Writer's block has various degrees of severity, from difficulty in coming ...

early in his career and sought psychiatric help to overcome its effects (undergoing analysis with Thomas Detre

Thomas P. Detre, M.D. (17 May 1924 – 9 October 2010) was a psychiatrist, academic, and senior administrator at the University of Pittsburgh, eulogized as the "visionary" leader most responsible for the transformation the university's teaching ho ...

in Rome). "Freedom to be oneself is all very well," he would write. "The greater freedom is not to be oneself.""It ended badly—with Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized f ...

(a student none of us knew, invited for his looks) pistol-whipping our poor drunken Somerset Maugham

William Somerset Maugham ( ; 25 January 1874 – 16 December 1965) was an English writer, known for his plays, novels and short stories. Born in Paris, where he spent his first ten years, Maugham was schooled in England and went to a German un ...

under a blossoming tree—but what was an ointment without flies? In memory the party shimmers and resounds like a Fête by Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

. Freedom to be oneself is all very well; the greater freedom is not to be oneself." James Merrill, ''A Different Person'', Knopf 1993, p. 129. Merrill painted a candid portrait in his memoir of gay life in the early 1950s, describing friendships and relationships with several men including Dutch poet Hans Lodeizen

Hans Lodeizen (20 July 1924 – 26 July 1950), born Johannes August Frederik Lodeizen, was a Dutch poet. He was the author of one book of poems (''The Wallpaper Within'', 1949) and a quantity of miscellaneous work. Despite his short life and mod ...

, Italian journalist Umberto Morra, U.S. writer Claude Fredericks

Claude Fredericks (October 14, 1923 – January 11, 2013) was an American poet, playwright, printer, writer, and teacher. He was a professor of literature at Bennington College in Vermont for more than 30 years, from 1961 to 1992.

In the la ...

, art dealer Robert Isaacson

Robert Isaacson (1 September 1927, St. Louis, Missouri – 5 November 1998, New York City) was a collector, scholar, and art dealer eulogized upon his death as "the Berenson of nineteenth century academic studies."Draper, James David (biograp ...

, David Jackson, and his partner from 1983 onward, actor Peter Hooten

John Peter Hooten (born November 29, 1950) is an American actor. He is best known for playing the title character in the television film '' Dr. Strange'' (1978).

Career

Hooten started acting in 1968 at the age of 17. He appeared as an uncredite ...

.

The Ingram Merrill Foundation

A prodigious correspondent and the keeper of many confidences, Merrill's "chief pleasure was friendship".White, Edmund, editor. ''Loss Within Loss: Artists in the Age of AIDS.'' Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2001, p. 282. Introducing Merrill at a December 13, 1993 New York poetry reading at the YMHA, novelistAllan Gurganus

Allan Gurganus is an American novelist, short story writer, and essayist whose work, which includes ''Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All'' and '' Local Souls'', is often influenced by and set in his native North Carolina.

Biography

Gurgan ...

said: "His genius for friendship is, if possible, his single greatest genius. He has, almost secretly, created a foundation dedicated to encouraging gifted young painters and writers. The foundation makes raids of vigilante kindness. It had helped those young artists who are healthy and those who discover they are dying just as they've begun." Answering to "Jim" in his youth and to "James" in published adulthood (and to "JM" in letters from readers), he was called "Jimmy", a childhood nickname, by friends and family until the end of his life. Despite great personal wealth derived from an unbreakable trust made early in his childhood, Merrill lived modestly.Merrill, James. ''A Different Person: A Memoir'', New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993, Chapter I. "As it happened, my father had taken a much earlier step to ensure his children's independence, by creating an unbreakable trust in each of our names. Thus at five years old I was rich, and would hold my own pursestrings when I came of age, whether I liked it or not. I wasn't sure I did like it. The best-intentioned people, knowing whose son I was and powerless against their own snobbery, could set me writhing under attentions I had done nothing to merit." Reprinted in ''Collected Prose'', Knopf, 2004, p. 461. (Before his father's death, Merrill and his two siblings renounced any further inheritance from their father's estate in exchange for $100 "as full quittance";Merrill, James. ''A Different Person: A Memoir''. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993, Chapter XVI; reprinted in ''Collected Prose'', Knopf, 2004, pp. 619-620. as a result, most of Charles Merrill's estate was donated to charity, including "The Orchard.")

A philanthropist in his own right, Merrill created the Ingram Merrill Foundation The Ingram Merrill Foundation was a private foundation established in the mid-1950s by poet James Merrill (1926-1995), using funds from his substantial family inheritance.J. D. McClatchyBraving the Elements ''The New Yorker'', 27 March 1995. Retriev ...

in the 1950s, the name of which united his divorced parents. The private foundation operated throughout the poet's lifetime and subsidized literature, the arts, and public television, with grants directed particularly to writers and artists showing early promise. Merrill met filmmaker Maya Deren

Maya Deren (; born Eleonora Derenkovskaya; ; Elizabeth Bishop

Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911 – October 6, 1979) was an American poet and short-story writer. She was Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1949 to 1950, the Pulitzer Prize winner for Poetry in 1956, the National Book Awar ...

a few years later, giving critical financial assistance to both and providing funds to hundreds of other writers, often anonymously.Merrill, James. ''A Different Person'', Knopf, 1993, Chapter II. Mustered out of the army in early 1945, Merrill returned to Amherst and civilian life, and soon began attending Kimon Friar's weekly lectures and workshops at the New York YMHA. Friar introduced Merrill to city friends including Anaïs Nin

Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell ( ; ; February 21, 1903 – January 14, 1977) was a French-born American diarist, essayist, novelist, and writer of short stories and erotica. Born to Cuban parents in France, Nin was the d ...

, W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, ...

, and Deren.

Merrill served as a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets

The Academy of American Poets is a national, member-supported organization that promotes poets and the art of poetry. The nonprofit organization was incorporated in the state of New York in 1934. It fosters the readership of poetry through outrea ...

from 1979 until his death. While wintering in Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

, he died on February 6, 1995, from a heart attack related to HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

. His ashes and the remains of David Jackson are buried side by side at Evergreen Cemetery, Stonington. Jackson's former wife and Merrill's friend, Doris Sewell Jackson is buried behind them.

In tribute to Merrill, ''The New Yorker'' republished his 1962 poem, "The Mad Scene", in its March 19, 1995 edition.James Merrill“The Mad Scene”

''The New Yorker'', March 19, 1995. The poem originally appeared in

Poetry Magazine

' in October/November 1962, and in the collection ''Water Street'' (Atheneum).

Awards

Beginning with the prestigiousGlascock Prize

The Glascock Poetry Prize is awarded to the winner of the annual Kathryn Irene Glascock Intercollegiate Poetry Contest at Mount Holyoke College. The "invitation-only competition is sponsored by the English department at Mount Holyoke and counts man ...

, awarded for ''The Black Swan'' when he was an undergraduate, Merrill would go on to receive every major poetry award in the United Stateincluding the 1977

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

for Poetry for ''Divine Comedies

{{italic title

''Divine Comedies'' is the seventh book of poetry by James Merrill (1926–1995). Published in 1976 (see 1976 in poetry), the volume includes " Lost in Translation" and all of ''The Book of Ephraim''. ''The Book of Ephraim'' is ...

''. Merrill was honored in mid-career with the Bollingen Prize

The Bollingen Prize for Poetry is a literary honor bestowed on an American poet. Every two years, the award recognizes a poet for best new volume of work or lifetime achievement. It is awarded without nominations or submissions by the Beinecke R ...

in 1973.

Merrill received the National Book Critics Circle Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".The Changing Light at Sandover

''The Changing Light at Sandover'' is a 560-page epic poem by James Merrill (1926–1995). Sometimes described as a postmodern apocalyptic epic, the poem was published in three volumes from 1976 to 1980, and as one volume "with a new coda" ...

'' (composed partly of supposedly supernatural

Supernatural phenomena or entities are those beyond the Scientific law, laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin 'above, beyond, outside of' + 'nature'. Although the corollary term "nature" has had multiple meanin ...

messages received via the use of a Ouija board

The Ouija ( , ), also known as a Ouija board, spirit board, talking board, or witch board, is a flat board marked with the letters of the Latin alphabet, the numbers 0–9, the words "yes", "no", and occasionally "hello" and "goodbye", along ...

). In 1990, he received the first Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry

The Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry is awarded biennially by the Library of Congress on behalf of the nation in recognition for the most distinguished book of poetry written by an American and published during the preceding two y ...

awarded by the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

for ''The Inner Room''. He garnered the National Book Award for Poetry

The National Book Award for Poetry is one of five annual National Book Awards, which are given by the National Book Foundation to recognize outstanding literary work by US citizens. They are awards "by writers to writers".

twice, in 1967 for ''Nights and Days''"National Book Awards – 1967"National Book Foundation

The National Book Foundation (NBF) is an American nonprofit organization established with the goal "to raise the cultural appreciation of great writing in America." Established in 1989 by National Book Awards, Inc.,Edwin McDowell. "Book Notes: ...

. Retrieved 2012-03-03. (With acceptance speech by Merrill and essay by Megan Snyder-Camp from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) and in 1979 for '' Mirabell: Books of Number''."National Book Awards – 1979"

National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-03. He was elected a Fellow of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1978. In 1991, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a nonprofit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest-achieving people in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet one ano ...

.

Style

A writer of elegance and wit, highly adept at wordplay and puns, Merrill was a master of traditionalpoetic meter

In poetry, metre ( Commonwealth spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse metre, or a certain set of ...

and form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form may also refer to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter dat ...

who also wrote a good deal of free

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, the ability to act or change without constraint or restriction

* Emancipate, attaining civil and political rights or equality

* Free (''gratis''), free of charge

* Gratis versus libre, the difference betw ...

and blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metre (poetry), metrical but rhyme, unrhymed lines, usually in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th cen ...

. (Asked once if he would prefer a more popular readership, Merrill replied "Think what one has to ''do'' to get a mass audience. I'd rather have one perfect reader. Why dynamite the pond in order to catch that single silver carp?"Merrill, James. "On 'Yánnina': An Interview with David Kalstone", ''Saturday Review'', December 1972; reprinted in ''Collected Prose'', New York: Knopf, 2004, p. 83.) Though not generally considered a Confessionalist poet, James Merrill made frequent use of personal relationships to fuel his "chronicles of love & loss" (as the speaker in '' Mirabell'' called his work). The divorce of Merrill's parents — the sense of disruption, followed by a sense of seeing the world "doubled" or in two ways at once — figures prominently in the poet's verse. Merrill did not hesitate to alter small autobiographical details to improve a poem's logic, or to serve an environmental, aesthetic, or spiritual theme.

As Merrill matured, the polished and taut brilliance of his early work yielded to a more informal, relaxed, and conversational tone.Fraser, CarolineThe Magician: Collected Poems by James Merrill

''Los Angeles Times'', 4 March 2001. Retrieved 14 June 2013. Already established in the 1970s among the finest poets of his generation, Merrill made a surprising detour when he began incorporating extensive

occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

messages into his work (although a poem from the 1950s, " Voices from the Other World," foreshadows the practice).Bornhauser, Fred. Interview with James Merrill in ''Contemporary Authors'', New Revision Series, vol. 10 (Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1983). Quoted in ''Collected Prose'', Knopf, 2004, pp. 135-136. The result, a 560-page apocalyptic epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

published as ''The Changing Light at Sandover

''The Changing Light at Sandover'' is a 560-page epic poem by James Merrill (1926–1995). Sometimes described as a postmodern apocalyptic epic, the poem was published in three volumes from 1976 to 1980, and as one volume "with a new coda" ...

'' (1982), documents two decades of messages dictated from otherworldly spirits during Ouija

The Ouija ( , ), also known as a Ouija board, spirit board, talking board, or witch board, is a flat board marked with the letters of the Latin alphabet, the numbers 0–9, the words "yes", "no", and occasionally "hello" and "goodbye", along ...

séance

A séance or seance (; ) is an attempt to communicate with spirits. The word ''séance'' comes from the French language, French word for "session", from the Old French , "to sit". In French, the word's meaning is quite general and mundane: one ma ...

s hosted by Merrill and his partner David Jackson. ''The Changing Light at Sandover'' is one of the longest epics

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

in any language, and features the voices of recently deceased poet W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, ...

, Merrill's late friends Maya Deren

Maya Deren (; born Eleonora Derenkovskaya; ; Maria Mitsotáki

Maria Mitsotáki (; 1907–1974) was an Athens socialite, born to a prominent Greek political family. She allegedly appeared in Ouija board séances to her friends James Merrill (1926–1995) and David Jackson David Jackson or Dave Jackson may refe ...

, as well as heavenly beings including the Archangel Michael

Michael, also called Saint Michael the Archangel, Archangel Michael and Saint Michael the Taxiarch is an archangel and the warrior of God in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. The earliest surviving mentions of his name are in third- and second ...

. Channeling voices through a Ouija board "made me think twice about the imagination," Merrill later explained. "If the ''spirits'' aren't external, how astonishing the ''mediums'' become! Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

said of his voices that they were like his own mental powers multiplied by five."

In Langdon Hammer's ''James Merrill: Life and Art'', Hammer quoted Alison Lurie

Alison Stewart Lurie (September 3, 1926December 3, 2020) was an American novelist and academic. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for her 1984 novel ''Foreign Affairs''. Although better known as a novelist, she wrote many non-fiction books ...

's writing of her experience with the Ouija board in ''Familiar Spirits: A Memoir of James Merrill and David Jackson'' as:

Lurie's response after reading Merrill and Jackson's collaborative effort in ''The Changing Light at Sandover'': ''"I sometimes had the feeling that my friend's mind was intermittently being taken over by a stupid and possibly even evil intelligence"''. According to Stoker Hunt, author of ''Ouija: The Most Dangerous Game'', before his death Merrill warned against the use of the Ouija board.

Following the publication of ''The Changing Light at Sandover'', Merrill returned to writing shorter poetry which could be both whimsical and nostalgic: "Self-Portrait in TYVEK Windbreaker" (for example) is a conceit

An extended metaphor, also known as a conceit or sustained metaphor, is the use of a single metaphor or analogy at length in a work of literature. It differs from a mere metaphor in its length, and in having more than one single point of contact be ...

inspired by a windbreaker jacket Merrill purchased from "one of those vaguely imbecile / Emporia catering to the collective unconscious / Of our time and place." The Tyvek

Tyvek () is a brand of synthetic flashspun high-density polyethylene fibers. The name ''Tyvek'' is a registered trademark of the American multinational chemical company DuPont, which discovered and commercialized Tyvek in the late 1950s and e ...

windbreaker — "DuPont contributed the seeming-frail, / Unrippable stuff first used for Priority Mail" — is "white with a world map." "A zipper's hiss, and the Atlantic Ocean closes / Over my blood-red T-shirt from the Gap."Marshall, Kathe BonannJames Merrill in Iowa City, October 1992

. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

Works by Merrill

Since his death, Merrill's work has been anthologized in three divisions: ''Collected Poems'', ''Collected Prose'', and ''Collected Novels and Plays''. Accordingly, his work below is divided upon those same lines.Poetry collections

*''The Black Swan'' (1946) *''First Poems'' (1951) *''The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace'' (1959) *''Water Street'' (1962) *''Nights and Days'' (1966) *''The Fire Screen'' (1969) *''Braving the Elements'' (1972) *''The Yellow Pages'' (1974) *''Divine Comedies

{{italic title

''Divine Comedies'' is the seventh book of poetry by James Merrill (1926–1995). Published in 1976 (see 1976 in poetry), the volume includes " Lost in Translation" and all of ''The Book of Ephraim''. ''The Book of Ephraim'' is ...

'' (1976), with " Lost in Translation" and ''The Book of Ephraim''

*'' Mirabell: Books of Number'' (1978)

*''Scripts for the Pageant'' (1980)

*''The Changing Light at Sandover

''The Changing Light at Sandover'' is a 560-page epic poem by James Merrill (1926–1995). Sometimes described as a postmodern apocalyptic epic, the poem was published in three volumes from 1976 to 1980, and as one volume "with a new coda" ...

'' (1982)

::composed of ''The Book of Ephraim'' (1976), ''Mirabell: Books of Number'' (1978), and ''Scripts for the Pageant'' (1980), with an added coda, "The Higher Keys"

*'' Late Settings'' (1985)

*''The Inner Room'' (1988)

*''A Scattering of Salts'' (1995)

Poetry selections

*''Selected Poems'' (London: Chatto & Windus, 1961) *''Two Poems: "From the Cupola" and "The Summer People"'' (London: Chatto & Windus, 1972) *''Samos'' (1980), published bySylvester & Orphanos Sylvester & Orphanos was a publishing house originally founded in Los Angeles by Ralph Sylvester, Stathis Orphanos and George Fisher in 1972. When Fisher moved to New York City, ''Sylvester & Orphanos'' specialized in limited-signed press books.

Or ...

*''From the First Nine: Poems 1946–1976'' (1982)

*''Selected Poems 1946–1985'' (1992)

Prose

*''Recitative'' (1986) - essays *''A Different Person'' (1993) - memoirNovels

*''The Seraglio'' (1957) *''The (Diblos) Notebook'' (1965)Drama

*''The Birthday'' (1947) *''The Bait'' (1953; revised 1988) *''The Immortal Husband'' (1955) *''The Image Maker'' (Sea Cliff Press, 1986) *''Voices from Sandover'' (1989; videotaped for commercial release in 1990)Posthumous editions

*''Collected Poems'' (2001) *''Collected Novels and Plays'' (2002) *''Collected Prose'' (2004) *''The Changing Light at Sandover'' (with the stage adaptation "Voices from Sandover") (2006) *''Selected Poems'' (2008) * * *Contributions

*''Notes on Corot'' (1960) - Essay in an exhibition catalog from the Art Institute of Chicago: ''COROT 1796-1875, An Exhibition of His Paintings and Graphic Works, October 6 through November 13, 1960''Recordings

* ''Reflected Houses'' (cassette audio recording, 1986) * ''The Voice of the Poet: James Merrill'' (cassette audio book, 1999)Works about Merrill

* *Harold Bloom

Harold Bloom (July 11, 1930 – October 14, 2019) was an American literary critic and the Sterling Professor of humanities at Yale University. In 2017, Bloom was called "probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world". Af ...

, ed. ''James Merrill'' (1985)

* Piotr Gwiazda, ''James Merrill and W.H. Auden: Homosexuality and Poetic Influence'' (2007)

* Nick Halpern, ''Everyday and Prophetic: The Poetry of Lowell, Ammons, Merrill and Rich'' (2003)

* Langdon Hammer, ''James Merrill: Life and Art'' (2015) eview in: The New Yorker, April 13, 2015: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/04/13/out-of-this-world-books-dan-chiasson">The New Yorker">eview in: The New Yorker, April 13, 2015: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/04/13/out-of-this-world-books-dan-chiasson/small>

* David Kalstone, ''Five Temperaments'' (1977)

* Ross Labrie, ''James Merrill'' (1982)

* David Lehman and Charles Berger (academic), Charles Berger, ''James Merrill: Essays in Criticism'' (1983)

* Christopher Lu, ''Nothing to Admire: The Politics of Poetic Satire from Dryden to Merrill'' (2003)

* Alison Lurie

Alison Stewart Lurie (September 3, 1926December 3, 2020) was an American novelist and academic. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for her 1984 novel ''Foreign Affairs''. Although better known as a novelist, she wrote many non-fiction books ...

, ''Familiar Spirits: A Memoir of James Merrill and David Jackson'' (2000)

* Tim Materer, ''James Merrill's Apocalypse'' (2000)

* Brian McHale, ''The Obligation Toward the Difficult Whole: Postmodern Long Poems'' (2004)

* Judith Moffett

Judith Moffett (born 1942) is an American author and academic. She has published poetry, non-fiction, science fiction, and translations of Swedish literature. She has been awarded grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts an ...

, ''James Merrill: An Introduction to the Poetry'' (1984)

* Judith Moffett

Judith Moffett (born 1942) is an American author and academic. She has published poetry, non-fiction, science fiction, and translations of Swedish literature. She has been awarded grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts an ...

, ''Unlikely Friends - James Merrill and Judith Moffett: A Memoir'' (2019)

* Peter Nickowitz, ''Rhetoric and Sexuality: The Poetry of Hart Crane, Elizabeth Bishop, and James Merrill'' (2006)

* Robert Polito

Robert Polito is a poet, biographer, essayist, critic, educator, curator, and arts administrator. He received the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography in 1995 for ''Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson.'' The founding director of th ...

, ''A Reader's Guide to James Merrill's "The Changing Light at Sandover"'' (1984)

* Guy Rotella, ed. ''Critical Essays on James Merrill'' (1996)

* Reena Sastri, ''James Merrill: Knowing Innocence'' (2007)

*

* Helen Vendler

Helen Vendler (née Hennessy; April 30, 1933 – April 23, 2024) was an American academic, writer and literary critic. She was a professor of English language and history at Boston University, Cornell, Harvard, and other universities.

Her aca ...

, ''Last Looks, Last Books: Stevens, Plath, Lowell, Bishop, Merrill'' (2010)

* Helen Vendler, ''The Music of What Happens: Poems, Critics, Writers'' (1988)

* Helen Vendler, ''Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets'' (1980)

* Helen Vendler, ''Soul Says: Recent Poetry'' (1995)

* Stephen Yenser, ''The Consuming Myth: The Work of James Merrill'' (1987)

*

Gallery

References

Further reading

*External links

'James Merrill House and Its Disembodied Transmissions'

in ''Cordite Poetry Review''

The James Merrill Digital Archive: Materials for ''The Book of Ephraim''

* * James Merrill Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. * Stephen Yenser Papers Relating to James Merrill. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

James Merrill House Museum & Writer-in-Residence Program

Emory University

James Ingram Merrill collection, 1923-2000

*Materials related to James Merrill in th

Robert A. Wilson collection

held b

Special Collections, University of Delaware

at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Merrill-Magowan Family Papers

at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Jack W.C. Hagstrom (AC 1955) James I. Merrill Bibliography Papers

at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections {{DEFAULTSORT:Merrill, James 1926 births 1995 deaths 20th-century American poets AIDS-related deaths in Arizona 20th-century American memoirists United States Army personnel of World War II Amherst College alumni Bollingen Prize recipients Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Formalist poets American gay writers Glascock Prize winners Lawrenceville School alumni American LGBTQ poets LGBTQ people from New York (state) National Book Award winners Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winners United States Army soldiers Poets from New York City American male poets 20th-century American male writers American male non-fiction writers Merrill family Military personnel from New York City Gay poets