Kutubiyya Mosque on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kutubiyya Mosque ( ;

The city of Marrakesh was founded around 1070 by the

The city of Marrakesh was founded around 1070 by the

Abd al-Mu'min began construction of the first Kutubiyya Mosque in 1147, the same year that he had conquered the city. Adjoined to the walls of the former Almoravid kasbah, the mosque may have also been built on top of some of the former Almoravid palace's annexes and maybe even over a royal cemetery or mausoleum. The date of the first mosque's completion is unconfirmed, but is estimated by historians to have been around 1157, when it is known with some certainty that prayers were conducted in the mosque. It was in 1157 that a celebrated copy of the

Abd al-Mu'min began construction of the first Kutubiyya Mosque in 1147, the same year that he had conquered the city. Adjoined to the walls of the former Almoravid kasbah, the mosque may have also been built on top of some of the former Almoravid palace's annexes and maybe even over a royal cemetery or mausoleum. The date of the first mosque's completion is unconfirmed, but is estimated by historians to have been around 1157, when it is known with some certainty that prayers were conducted in the mosque. It was in 1157 that a celebrated copy of the  The mosque was likely connected to the adjacent royal palace via a passage (''sabat'') which allowed the Almohad

The mosque was likely connected to the adjacent royal palace via a passage (''sabat'') which allowed the Almohad

The construction dates of the second mosque are also not firmly established. One historical chronicle, reported by al-Maqqari, claims that construction began on the second mosque in May 1158 ( Rabi' al-Thani 553 AH) and was completed with the inauguration of the first Friday prayers in September (

The construction dates of the second mosque are also not firmly established. One historical chronicle, reported by al-Maqqari, claims that construction began on the second mosque in May 1158 ( Rabi' al-Thani 553 AH) and was completed with the inauguration of the first Friday prayers in September (

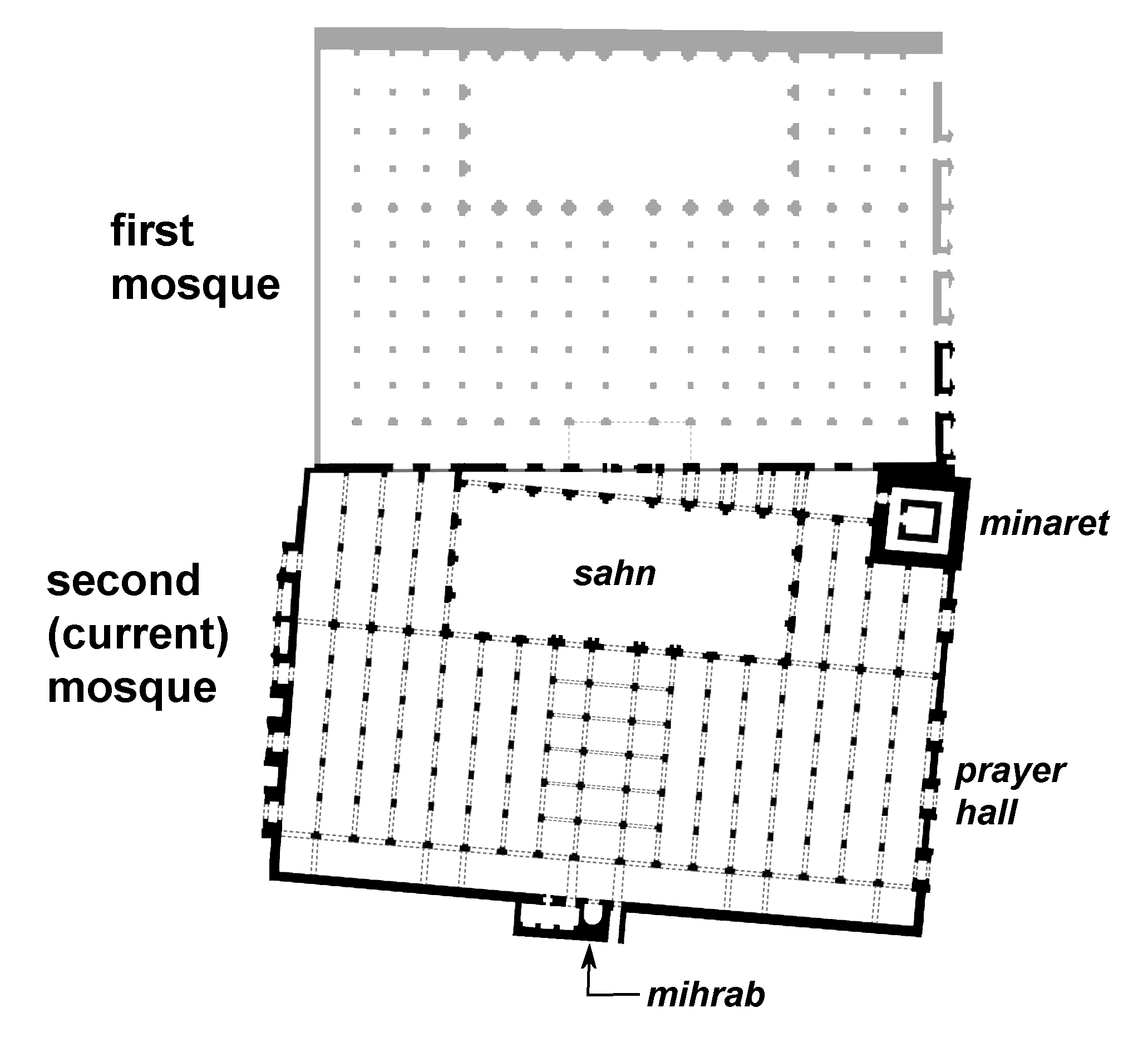

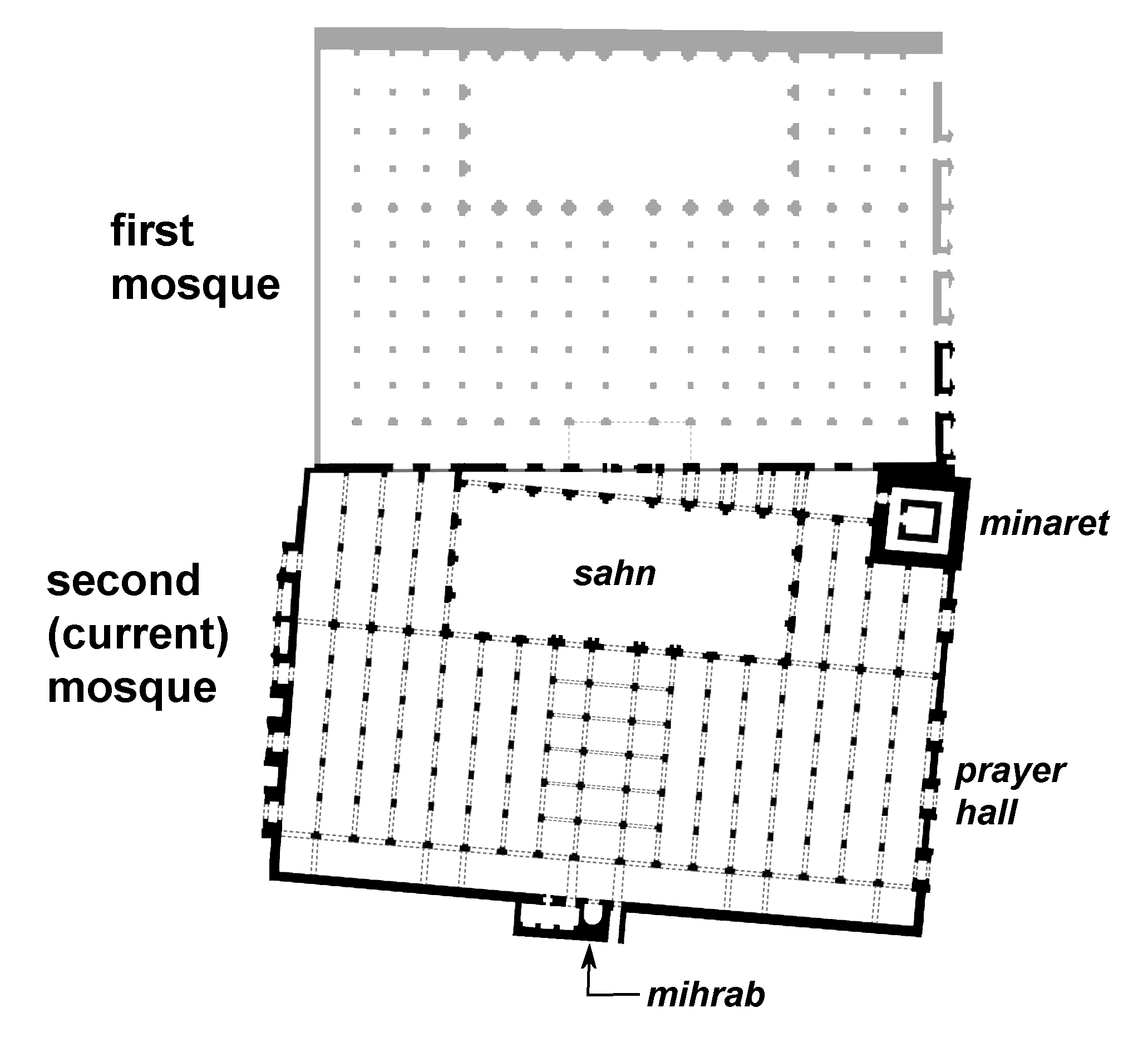

Architectural details of the first mosque and the second mosque are almost identical except for the orientation. Hence, what is true of one holds true for the other, though the first mosque is now only visible as archaeological remains. The mosque is a characteristic Almohad design, and its various elements resemble those of many other mosques from the same period. The mosque's floor plan is a slightly irregular

Architectural details of the first mosque and the second mosque are almost identical except for the orientation. Hence, what is true of one holds true for the other, though the first mosque is now only visible as archaeological remains. The mosque is a characteristic Almohad design, and its various elements resemble those of many other mosques from the same period. The mosque's floor plan is a slightly irregular

The mosque is located in a large plaza with gardens, and is floodlit at night. The wall on the northern side of the first mosque abutted the old Almoravid fortress wall (the ''Ksar el-Hajjar''). There are eight entrances to the mosque: four on the west side and four on the east side. The eastern side faces the street where book shops were located, hence the name "Booksellers' Mosque". There is a private entrance for the

The mosque is located in a large plaza with gardens, and is floodlit at night. The wall on the northern side of the first mosque abutted the old Almoravid fortress wall (the ''Ksar el-Hajjar''). There are eight entrances to the mosque: four on the west side and four on the east side. The eastern side faces the street where book shops were located, hence the name "Booksellers' Mosque". There is a private entrance for the

The interior prayer hall is a

The interior prayer hall is a

The minaret is designed in Almohad style and was constructed in

The minaret is designed in Almohad style and was constructed in

Koutobia Mosque entry at ArchNet

(includes section of images with floor plan of mosque and photographs of its interior)

Kutubiya Mosque page at Discover Islamic Art

(includes picture of the upper chamber inside the minaret)

360-degree view of the area near the mihrab

posted on Google Maps

Manar al-Athar digital image archive

(including a range of exterior photo angles) {{Authority control Mosques in Marrakesh 12th-century mosques Almohad architecture Tourist attractions in Marrakesh Religious buildings and structures completed in 1195

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

: ⵜⵉⵎⵣⴳⵉⴷⴰ ⵏ ⵍⴽⵓⵜⵓⴱⵉⵢⵢⴰ, french: Mosquée Koutoubia) or Koutoubia Mosque is the largest mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

in Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

. The mosque's name is also variably rendered as Jami' al-Kutubiyah, Kutubiya Mosque, Kutubiyyin Mosque, and Mosque of the Booksellers. It is located in the southwest medina quarter of Marrakesh, near the famous public place of Jemaa el-Fna, and is flanked by large gardens.

The mosque was founded in 1147 by the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

right after he conquered Marrakesh from the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

. A second version of the mosque was entirely rebuilt by Abd al-Mu'min around 1158, with Ya'qub al-Mansur possibly finalizing construction of the minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

around 1195. This second mosque is the structure that stands today. It is considered a classic and important example of Almohad architecture and of Moroccan mosque architecture generally. The minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

tower, in height, is decorated with varying geometric arch motifs and topped by a spire and metal orbs. It likely inspired other buildings such as the Giralda

The Giralda ( es, La Giralda ) is the bell tower of Seville Cathedral in Seville, Spain. It was built as the minaret for the Great Mosque of Seville in al-Andalus, Moorish Spain, during the reign of the Almohad dynasty, with a Renaissance-style ...

of Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

and the Hassan Tower of Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populatio ...

, which were built shortly after in the same era.Hattstein, Markus and Delius, Peter (eds.) ''Islam: Art and Architecture''. h.f.ullmann. The minaret is also considered an important landmark and symbol of Marrakesh.

Geography

The mosque is located about west of the city's the Jemaa El Fna souq, a prominent market place which has existed since the city's establishment. It is situated on the Avenue Mohammed V, opposite Place de Foucauld. DuringFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

occupation, the network of roads was developed with the mosque as the central landmark, in the ''ville nouvelle''. To the west and south of the mosque is a notable rose garden, and across Avenue Houmman-el-Fetouaki is the small mausoleum of the Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century tha ...

emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

Yusuf ibn Tashfin

Yusuf ibn Tashfin, also Tashafin, Teshufin, ( ar, يوسف بن تاشفين ناصر الدين بن تالاكاكين الصنهاجي , Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn Naṣr al-Dīn ibn Tālākakīn al-Ṣanhājī ; reigned c. 1061 – 1106) was l ...

, one of the great builders of Marrakesh, consisting of a simple crenelated structure.

In the mosque's esplanade, which backs onto Jemaa el Fna, the ruins of the first Kutubiyya Mosque can be seen. A part of the perimeter of the Ksar al-Hajjar, the original stone fortress built in 1070 by Abu Bakr ibn Umar

Abu Bakr ibn Umar ibn Ibrahim ibn Turgut, sometimes suffixed al-Sanhaji or al-Lamtuni (died 1087; ar, أبو بكر بن عمر) was a chieftain of the Lamtuna Berber Tribe and Amir of the Almoravids from 1056 until his death. He is credited ...

, the Almoravid founder of the city, was also uncovered on the northern side of the original mosque. Also visible today at the northeast corner of these ruins is a part of ''Bab 'Ali'', the monumental stone gate of Ali ibn Yusuf

Ali ibn Yusuf (also known as "Ali Ben Youssef") () (born 1084 died 26 January 1143) was the 5th Almoravid emir. He reigned from 1106–1143.

Biography

Ali ibn Yusuf was born in 1084 in Ceuta. He was the son of Yusuf ibn T ...

's former palace which was completed in 1126 next to the fortress before being demolished by the Almohads to make way for their new mosque. Directly east of the current mosque is a 19th-century walled residence known as Dar Moulay Ali, which now serves as the French consulate.

Also on the same esplanade is a small white domed building, the Koubba (or Qubba) of Lalla Zohra. This is the tomb of Fatima Zohra bint al-Kush (also called Lalla Zohra), a female mystic who died in the early 17th century and was buried here near the mosque.

Origin of name

All the names and spellings of Kutubiyya Mosque, including Jami' al-Kutubiyah, Kotoubia, Kutubiya, and Kutubiyyin, are based on theArabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

word ''kutubiyyin'' (), which means "booksellers". The Koutoubia Mosque, or Bookseller's Mosque, reflects the honorable bookselling

Bookselling is the commercial trading of books which is the retail and distribution end of the publishing process. People who engage in bookselling are called booksellers, bookdealers, bookpeople, bookmen, or bookwomen. The founding of librar ...

trade practiced in the nearby souk. At one time as many as 100 book vendors worked in the streets at the base of the mosque.

History

Almohad conquest and reform of Marrakesh

The city of Marrakesh was founded around 1070 by the

The city of Marrakesh was founded around 1070 by the Almoravid dynasty

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century tha ...

to be their capital, but was captured in 1147 by the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire ...

under their leader Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

. While the Almohads decided to make Marrakesh their capital too, they did not want any trace of religious monuments built by the Almoravids, their staunch enemies, as they considered them heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

s. They reportedly demolished all the mosques in the city, including the main mosque, the Ben Youssef Mosque

The Ben Youssef Mosque (also known by its English spelling as the "Ibn Yusuf Mosque"), is a mosque in the Medina quarter of Marrakesh, Morocco, named after the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf. It is arguably the oldest and most important mosque in ...

, arguing that the Almoravid mosques were not aligned with the proper ''qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

'' (direction of prayer).

Since the former Almoravid grand mosque (i.e. the original Ben Youssef Mosque) was already closely integrated into the surrounding urban fabric, it was not practical for the Almohads to rebuild an entirely new mosque with a significantly different orientation on the same site. It's possible that they did not even demolish the mosque but merely left it derelict. The Almohads may have also wished to have the city's main mosque located closer to the kasbah

A kasbah (, also ; ar, قَـصَـبَـة, qaṣaba, lit=fortress, , Maghrebi Arabic: ), also spelled qasba, qasaba, or casbah, is a fortress, most commonly the citadel or fortified quarter of a city. It is also equivalent to the term ''alca ...

and royal palaces, as was common in other Islamic cities. As a result, Abd al-Mu'min decided to build the new mosque right next to the former Almoravid kasbah, the Ksar el-Hajjar, which became the site of the new Almohad royal palace, located west of the city's main square (what is today the Jemaa el-Fnaa).

Almohad versus Almoravid ''qibla'' alignment

The issue of theqibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

alignment of the Kutubiyya and other Almohad mosques (and even of medieval Islamic mosques generally) is a complex one which is often misunderstood. The justification given by the Almohads for the destruction of existing Almoravid mosques was that their qibla was aligned too far to the east, which the Almohads judged to be incorrect as they preferred a tradition that existed in the western Islamic world (the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

and al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

) according to which the qibla should be oriented toward the south instead. This alignment was actually further away from the "true" qibla which points directly toward Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

and which is used in modern mosques everywhere today. Qibla orientations varied throughout the medieval period of Morocco but the Almohads generally followed an orientation between 154° and 159° (numbers expressed as the azimuth

An azimuth (; from ar, اَلسُّمُوت, as-sumūt, the directions) is an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. More specifically, it is the horizontal angle from a cardinal direction, most commonly north.

Mathematical ...

from the true north

True north (also called geodetic north or geographic north) is the direction along Earth's surface towards the geographic North Pole or True North Pole.

Geodetic north differs from ''magnetic'' north (the direction a compass points toward t ...

), whereas the "true" qibla (i.e. the exact direction of Mecca) in Marrakesh is 91° (nearly due east). This true qibla was eventually adopted in modern times and is evident in more recent mosques including the current Ben Youssef Mosque which was rebuilt in 1819 with a qibla of 88° (slightly too far north but very close).

The Almohad qibla was similar to the qibla orientation of the Great Mosque of Cordoba and the Qarawiyyin Mosque of Fes, both founded at an early period in the late 8th to 9th centuries. This traditional qibla was based on a saying (''hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

'') of the Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

which stated that "What is between the east and west is a qibla" (most likely in reference to his time in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, north of Mecca), which thus legitimized southern alignments. This practice may also have sought to emulate the orientation of the walls of the rectangular ''Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

'' building inside the Great Mosque of Mecca

, native_name_lang = ar

, religious_affiliation = Islam

, image = Al-Haram mosque - Flickr - Al Jazeera English.jpg

, image_upright = 1.25

, caption = Aerial view of the Great Mosque of Mecca

, map ...

, based on another tradition which considered the different sides of the Kaaba as being associated with different parts of the Muslim world. In this tradition the northwest face of the Kaaba was associated with al-Andalus and, accordingly, the Great Mosque of Cordoba was oriented toward the southeast as if facing the Kaaba's northwestern façade, with its main axis parallel to the main axis of the Kaaba structure (which was oriented from southeast to northwest). This architectural alignment was typically achieved by using astronomical alignments to reproduce the appropriate orientation of the Kaaba itself, whose minor axis is aligned with the direction of sunrise at the summer solstice

The summer solstice, also called the estival solstice or midsummer, occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere (Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the summer ...

.

That being said, medieval Muslims did in fact possess sufficient mathematical knowledge to calculate a reasonably accurate "true" qibla pointing directly toward Mecca. A more easterly qibla orientation (which points approximately toward Mecca) was already evident in the royal mosque of Madinat al-Zahra

Madinat al-Zahra or Medina Azahara ( ar, مدينة الزهراء, translit=Madīnat az-Zahrā, lit=the radiant city) was a fortified palace-city on the western outskirts of Córdoba in present-day Spain. Its remains are a major archaeological ...

(just outside Cordoba) built later in the 10th century, as well as in the orientation of the original Almoravid Ben Youssef Mosque

The Ben Youssef Mosque (also known by its English spelling as the "Ibn Yusuf Mosque"), is a mosque in the Medina quarter of Marrakesh, Morocco, named after the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf. It is arguably the oldest and most important mosque in ...

(founded in 1126), estimated to be 103°. The Almohads, who rose to power after these periods, apparently chose a qibla orientation which they saw as more ancient or traditional, or as emulating the prestigious Great Mosque of Cordoba. Whether their interpretation of the qibla was a true and rigorously followed directive or a mostly symbolic argument to differentiate themselves from the Almoravids is still questioned by scholars.

The first Kutubiyya Mosque

Abd al-Mu'min began construction of the first Kutubiyya Mosque in 1147, the same year that he had conquered the city. Adjoined to the walls of the former Almoravid kasbah, the mosque may have also been built on top of some of the former Almoravid palace's annexes and maybe even over a royal cemetery or mausoleum. The date of the first mosque's completion is unconfirmed, but is estimated by historians to have been around 1157, when it is known with some certainty that prayers were conducted in the mosque. It was in 1157 that a celebrated copy of the

Abd al-Mu'min began construction of the first Kutubiyya Mosque in 1147, the same year that he had conquered the city. Adjoined to the walls of the former Almoravid kasbah, the mosque may have also been built on top of some of the former Almoravid palace's annexes and maybe even over a royal cemetery or mausoleum. The date of the first mosque's completion is unconfirmed, but is estimated by historians to have been around 1157, when it is known with some certainty that prayers were conducted in the mosque. It was in 1157 that a celebrated copy of the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

attributed to the hand of Caliph Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

, previously kept in the Great Mosque of Cordoba, was transferred to the mosque. Abd al-Mu'min also transferred to his mosque the famous Almoravid minbar of the Ben Youssef Mosque, originally commissioned by Ali ibn Yusuf from a workshop in Cordoba.

The mosque was likely connected to the adjacent royal palace via a passage (''sabat'') which allowed the Almohad

The mosque was likely connected to the adjacent royal palace via a passage (''sabat'') which allowed the Almohad caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

to enter it directly from his palace without having to pass through the public entrances (not unlike a similar passage which existed between the caliph's palace and the Great Mosque of Cordoba). This passage likely passed through the imam's chamber behind the southeastern qibla wall and therefore may have disappeared when the second mosque was built over this area. Modern archeological excavations have also confirmed the existence in the first Kutubiyya Mosque of a near-legendary mechanism which allowed the wooden ''maqsura

''Maqsurah'' ( ar, مقصورة, literally "closed-off space") is an enclosure, box, or wooden screen near the ''mihrab'' or the center of the '' qibla'' wall in a mosque. It was typically reserved for a Muslim ruler and his entourage, and was ...

'' (a screen separating the caliph and his entourage from the rest of the crowd during prayers) to rise from a trench in the ground seemingly by itself, and then retract in the same manner when the caliph left. Another semi-automated mechanism also allowed the minbar to emerge and move forward from its storage chamber (next to the ''mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla ...

'') seemingly by itself. The exact functioning of the mechanism is unknown, but may have relied on a hidden system of counterweights.

The new Almohad mosque was thus imbued with great political and religious symbolism, being closely associated with the ruling dynasty, and made subtle references to the ancient Umayyad caliphate in Cordoba, whose great mosque was a model for much of subsequent Moroccan and Moorish architecture

Moorish architecture is a style within Islamic architecture which developed in the western Islamic world, including al-Andalus (on the Iberian Peninsula, Iberian peninsula) and what is now Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia (part of the Maghreb). The ...

. It is unknown if the first Kutubiyya Mosque had a minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

, though some historians have suggested that a former bastion of the Almoravid kasbah (Ksar el-Hajjar) on the mosque's northeastern corner may have been converted into the mosque's first minaret, whose remains might have been visible even as late as the beginning of the 19th century.

It is unclear when exactly the first Kutubiyya Mosque disappeared, but its layout is well-known thanks to modern excavations starting in 1923. The excavated foundations of the mosque, as well as the outline of its mihrab and qibla wall, are still visible today on the second mosque's northwestern side. Also visible today nearby are the uncovered vestiges of the Ksar el-Hajjar to which the mosque was adjoined.

The second (current) Kutubiyya Mosque

At some point, Abd al-Mu'min decided to build a second mosque directly adjoined to the southeastern (qibla) side of the first mosque. The reasons for this unusual decision are still not fully understood. The most popular historical narrative asserts that Abd al-Mu'min discovered, possibly during its construction, that the initial mosque was misaligned with the qibla (presumably according to Almohad criteria). The second mosque is indeed aligned slightly further to the south, at an azimuth of 159° or 161° from the true north, compared to the 154° alignment of the first mosque, which actually makes the second mosque 5 to 7 degrees further out of alignment with respect to the "true" or modern qibla. Why this slightly different alignment was preferred is unclear; it may be that the first mosque was aligned with the walls of the Ksar el-Hajjar and that this was judged sufficient at the time, but that the alignment of the second mosque more closely matched that of the Tinmal Mosque (an important Almohad religious site) which had been built in the meantime. Other possible motivations for the construction of the second mosque may have been to accommodate a growing population, to double the building's size to make it more impressive, or even as an excuse to make one of the mosques exclusive to the ruling elites while the other was used by the general population. The construction dates of the second mosque are also not firmly established. One historical chronicle, reported by al-Maqqari, claims that construction began on the second mosque in May 1158 ( Rabi' al-Thani 553 AH) and was completed with the inauguration of the first Friday prayers in September (

The construction dates of the second mosque are also not firmly established. One historical chronicle, reported by al-Maqqari, claims that construction began on the second mosque in May 1158 ( Rabi' al-Thani 553 AH) and was completed with the inauguration of the first Friday prayers in September (Sha'ban

Shaʽban ( ar, شَعْبَان, ') is the eighth month of the Islamic calendar. It is called as the month of "separation", as the word means "to disperse" or "to separate" because the pagan Arabs used to disperse in search of water.

The fiftee ...

) of the same year. However, this construction period seems implausibly short and it is likely that construction either began before May 1158 or (perhaps more likely) continued after September 1158. The famous minaret of the mosque, which is visible today, is also not conclusively dated. Some historical sources attribute it to Abd al-Mu'min (who reigned up until 1163) while others attribute it to Ya'qub al-Mansur (who reigned between 1184 and 1199). According to some historians (including Deverdun), the most likely scenario is that the minaret was begun before 1158 and largely built by Abd al-Mu'min, or at the very least designed on his commission. It is plausible, however, that Ya'qub al-Mansur either finished the work in his time, or that he added the small secondary "lantern"-tower at its summit in 1195.

The second Kutubiyya Mosque was built almost identical to the first except for its adjusted orientation. The layout, architectural designs, dimensions and materials used for construction were almost all the same. The only architectural differences are in a few details and in the fact that the second mosque was slightly wider than the first. The mosque's floor plan is also slightly irregular due to the fact that its northern wall is still the old southern wall of the first mosque, which is at a slightly different angle from the second mosque (due to the different qibla orientation, as explained above).

As mentioned, it is not known when the first mosque was actually deserted, or even whether it was abandoned and allowed to deteriorate or if it was consciously demolished at some point. Scholars believe that the two mosques most likely coexisted for a time as one large mosque. For example, they believe the old qibla (southern) wall of the first mosque, which became the northern wall of the second mosque, was opened up in many places to allow easy circulation between the old and the new buildings, and was only later sealed up as it is today. Additionally, the mosque's current minaret appears to have been integrated into the fabric of both mosques, as evidenced by the remains of an arcade belonging to the first mosque and yet still integrated into the base of the minaret today. Gaston Deverdun, in his heavily cited 1959 book on the history of Marrakesh, suggested the possibility that the first mosque was only abandoned after Ya'qub al-Mansur built a new royal citadel (the current Kasbah

A kasbah (, also ; ar, قَـصَـبَـة, qaṣaba, lit=fortress, , Maghrebi Arabic: ), also spelled qasba, qasaba, or casbah, is a fortress, most commonly the citadel or fortified quarter of a city. It is also equivalent to the term ''alca ...

district) further south. As part of this citadel, al-Mansur had raised the new Kasbah Mosque, completed in 1190, which subsequently served as the main mosque of the caliph and the ruling elites. This would have thus made the old Kutubiyya less useful, particularly the first mosque which was attached to the former, now abandoned, royal palace. It is even possible that the first Kutubiyya was dismantled in order to reuse its materials in the construction of the new kasbah and its mosque.

The mosque, and more specifically its minaret, was the forerunner of two other structures built on the same pattern, the " Tour Hassan" in Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populatio ...

(a monumental mosque begun by Ya'qub al-Mansur but never finished) and the Great Mosque of Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

, Spain, whose minaret is preserved as the Giralda

The Giralda ( es, La Giralda ) is the bell tower of Seville Cathedral in Seville, Spain. It was built as the minaret for the Great Mosque of Seville in al-Andalus, Moorish Spain, during the reign of the Almohad dynasty, with a Renaissance-style ...

. This structure thus became one of the models for subsequent Moroccan-Andalusian architecture.

Recent history and present day

The mosque's minaret is featured in '' Tower of the Koutoubia Mosque'', a painting byWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

made after the 1943 Casablanca Conference

The Casablanca Conference (codenamed SYMBOL) or Anfa Conference was held at the Anfa Hotel in Casablanca, French Morocco, from January 14 to 24, 1943, to plan the Allied European strategy for the next phase of World War II. In attendance were ...

. The mosque and its minaret were restored at the end of the 1990s. In 2016 the mosque was fitted with solar panels, solar water heaters, and energy-efficient LED lights as part of an effort to make state-run mosques more dependent on renewable green energy.

Today, the mosque is still active and non-Muslims are not allowed inside. However, it is possible to visit the Tinmal Mosque, built along the same lines, which is inactive but preserved as a historic site south of Marrakesh.

Architecture

Architectural details of the first mosque and the second mosque are almost identical except for the orientation. Hence, what is true of one holds true for the other, though the first mosque is now only visible as archaeological remains. The mosque is a characteristic Almohad design, and its various elements resemble those of many other mosques from the same period. The mosque's floor plan is a slightly irregular

Architectural details of the first mosque and the second mosque are almost identical except for the orientation. Hence, what is true of one holds true for the other, though the first mosque is now only visible as archaeological remains. The mosque is a characteristic Almohad design, and its various elements resemble those of many other mosques from the same period. The mosque's floor plan is a slightly irregular quadrilateral

In geometry a quadrilateral is a four-sided polygon, having four edges (sides) and four corners (vertices). The word is derived from the Latin words ''quadri'', a variant of four, and ''latus'', meaning "side". It is also called a tetragon, ...

due to the fact that its northern wall corresponds to the former southern wall of the first mosque and its different orientation. The current mosque is roughly wide, long on its west side, and long on its east side. Aside from the minaret, the mosque is generally built in brick, although sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

masonry is also used for parts of the outer walls. The same materials and construction methods are also evident in the first mosque.

Exterior

The mosque is located in a large plaza with gardens, and is floodlit at night. The wall on the northern side of the first mosque abutted the old Almoravid fortress wall (the ''Ksar el-Hajjar''). There are eight entrances to the mosque: four on the west side and four on the east side. The eastern side faces the street where book shops were located, hence the name "Booksellers' Mosque". There is a private entrance for the

The mosque is located in a large plaza with gardens, and is floodlit at night. The wall on the northern side of the first mosque abutted the old Almoravid fortress wall (the ''Ksar el-Hajjar''). There are eight entrances to the mosque: four on the west side and four on the east side. The eastern side faces the street where book shops were located, hence the name "Booksellers' Mosque". There is a private entrance for the imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

on the south side of the mosque, leading to a door on the left side of the mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla ...

. Historically, the first Kutubiyya Mosque also had a private entrance next to the mihrab which was used by the ruler to enter directly into the maqsura

''Maqsurah'' ( ar, مقصورة, literally "closed-off space") is an enclosure, box, or wooden screen near the ''mihrab'' or the center of the '' qibla'' wall in a mosque. It was typically reserved for a Muslim ruler and his entourage, and was ...

.

Interior

Courtyard (''sahn'')

The rectangular ''sahn

A ''sahn'' ( ar, صَحْن, '), is a courtyard in Islamic architecture, especially the formal courtyard of a mosque. Most traditional mosques have a large central ''sahn'', which is surrounded by a '' riwaq'' or arcade on all sides. In traditi ...

'' or courtyard is in the northern part of the mosque. It is wide, the same width as the nine central naves, and long or deep. There is an ablution fountain at the center of the courtyard. Nowadays trees are also planted in a grid pattern throughout the courtyard. The decoration is otherwise limited to the arches running along the edges of the courtyard, with some of the arches are highlighted with a polylobed molding carved around them.

Prayer hall

The interior prayer hall is a

The interior prayer hall is a hypostyle

In architecture, a hypostyle () hall has a roof which is supported by columns.

Etymology

The term ''hypostyle'' comes from the ancient Greek ὑπόστυλος ''hypóstȳlos'' meaning "under columns" (where ὑπό ''hypó'' means below or un ...

hall with more than 100 pillars which support rows of horseshoe arch

The horseshoe arch (; Spanish: "arco de herradura"), also called the Moorish arch and the keyhole arch, is an emblematic arch of Islamic architecture, especially Moorish architecture. Horseshoe arches can take rounded, pointed or lobed form.

Hi ...

es that divide the hall into 17 parallel naves or aisles which run perpendicular to the southern wall, or roughly north to south. The pillars and arches are made of brick covered in white plaster. The nine naves in the middle correspond to the width of the courtyard to the north and run the length of six arches, while the four outermost naves run continuously along the east and west sides of the courtyard (corresponding to the length of four extra arches), thus extending the prayer hall around either side of the courtyard. The naves are all covered by ''berchla'' or Moroccan wood-frame ceilings on the inside and sloped green-tiled roofs on the outside.

The ''mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla ...

'', a niche symbolizing the ''qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

'' (direction of prayer), is set in the middle of the qibla wall (the southern wall) of the prayer hall and is a central focus of its layout. The prayer hall has a "T"-plan, in that the central nave aligned with the mihrab and another transverse (i.e. perpendicular) aisle running along the qibla wall are wider than other aisles and intersect each other (thus forming a "T" within the floor plan of the mosque). This layout is found in other Almohad mosques and in all major mosques of the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

for much of the Islamic period; a clear T-plan is present in the 9th-century Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, for example, and in later Moroccan mosques. In addition to their greater width, the central nave and the southern transverse aisle are architecturally highlighted in other ways. unlike the other naves, The central nave is covered by a series of cupola ceilings instead of a long sloped roof. The central nave, as well as the adjacent nave on either side, is split into bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

by five transverse arches (i.e. arches perpendicular to the other arches). The transverse arch right in front of the mihrab, as well as the two parallel arches on either side of the mihrab, have a lambrequin profile instead of a horseshoe profile and their intrados are carved with ''muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

'' sculpting. Finally, the southern (or qibla) transverse aisle of the mosque is bordered on its north side by an additional row of transverse arches with a polylobed profile, setting it apart from the rest of the mosque. Elsewhere, transverse polylobed or lambrequin arches are also used to demarcate the extensions of the prayer hall on either side of the courtyard from the rest of the mosque.

The southern qibla aisle is further decorated with five elaborate muqarnas cupolas: one in front of the mihrab, one at both southern corners of the prayer hall, and two more in between these (or, specifically, at the southern end of the outermost naves that intersect with the courtyard). Muqarnas consists of honeycomb or stalactite-like sculpting made up of hundreds of small niches arranged in a three-dimensional geometric composition. Although made with the same technique, the exact geometric composition of each muqarnas cupola in the mosque is slightly different. Most of the constituent niches are smooth, but eight-pointed stars are carved in the upper parts of the geometric alcoves.

The mihrab has a form which derives from the style established by the Great Mosque of Cordoba, although with some changes in the decorative elements. It consists of a horseshoe arch opening leading to a miniature chamber covered by an octagonal muqarnas dome. Carved decoration covers the wall surfaces around the mihrab arch. The arch is bordered with a scalloped or polylobed molding inside a rectangular ''alfiz The alfiz (, from Andalusi Arabic ''alḥíz'', from Standard Arabic ''alḥáyyiz'', meaning 'the container';Al ...

'' frame, with rosettes in the upper corners. Above this are five false windows forming a blind arcade

A blind arcade or blank arcade is an arcade (a series of arches) that has no actual openings and that is applied to the surface of a wall as a decorative element: i.e., the arches are not windows or openings but are part of the masonry face. It is ...

, with two of the windows filled with carved arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

s. All of this is surrounded in turn by a frieze of geometric decoration. The sides of mihrab's opening are decorated with six engaged

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

marble columns (three on either side) whose ornately carved capitals

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

are spolia

''Spolia'' (Latin: 'spoils') is repurposed building stone for new construction or decorative sculpture reused in new monuments. It is the result of an ancient and widespread practice whereby stone that has been quarried, cut and used in a built ...

originating from Cordoba in al-Andalus, brought to Marrakesh either by the Almohads or by the Almoravids before them. Two doors also flank the mihrab on either side: the one on the right is for the storage room of the minbar, while the one on the left was used by the imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

to enter the mosque. Both doors are also flanked with engaged columns with more spolia capitals from Al-Andalus.

All of these decorative and architectural elements – the muqarnas cupolas, the mihrab decoration, and the hierarchical arrangement of arches – are found in similar form and placement in the Tinmal Mosque, which was built in the same period as the Kutubiyya, and in many later mosques such as the 16th-century Saadian

The Saadi Sultanate (also rendered in English as Sa'di, Sa'did, Sa'dian, or Saadian; ar, السعديون, translit=as-saʿdiyyūn) was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of West Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was l ...

mosques of Bab Doukkala

Bab Doukkala () is the main northwestern gate of the medina (historic walled city) of Marrakesh, Morocco.

Description

The gate dates back to around 1126 CE when the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf built the first walls of the city. Doukkala, w ...

and Mouassine.

Minaret

The minaret is designed in Almohad style and was constructed in

The minaret is designed in Almohad style and was constructed in rubble masonry

Rubble stone is rough, uneven building stone not laid in regular courses. It may fill the core of a wall which is faced with unit masonry such as brick or ashlar. Analogously, some medieval cathedral walls are outer shells of ashlar with an inn ...

using sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

. It was historically covered with Marrakshi pink plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

, but in the 1990s, experts opted to expose the original stone work and removed the plaster. The minaret tower is in height, including the spire, itself tall. Each side of the square base is in length. The minaret is visible from a distance of . Its prominence makes it a landmark structure of Marrakesh, which is maintained by an ordinance prohibiting any high rise buildings (above the height of a palm tree) to be built around it. The mu'azzin

The muezzin ( ar, مُؤَذِّن) is the person who proclaims the call to the daily prayer ( ṣalāt) five times a day (Fajr prayer, Zuhr prayer, Asr prayer, Maghrib prayer and Isha prayer) at a mosque. The muezzin plays an important role i ...

gives the ''adhan

Adhan ( ar, أَذَان ; also variously transliterated as athan, adhane (in French), azan/azaan (in South Asia), adzan (in Southeast Asia), and ezan (in Turkish), among other languages) is the Islamic call to public prayer ( salah) in a mo ...

'' from the four cardinal directions at the top of the minaret, calling the faithful to prayer.

Its design includes a high square shaft (which takes up about four fifths of its height) and another smaller square shaft standing on top of it, capped by a dome. Many features of the minaret are also found in other religious buildings in the country, such as a wide band of ceramic tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or ...

s near the top and the alternation between different but related motifs on each façade of the minaret, including Moorish-style polylobed arch patterns. The latter motifs form prominent compositions within rectangular frames carved into the stone around the windows. These carved compositions also originally featured polychrome

Polychrome is the "practice of decorating architectural elements, sculpture, etc., in a variety of colors." The term is used to refer to certain styles of architecture, pottery or sculpture in multiple colors.

Ancient Egypt

Colossal statu ...

painted decoration of geometric and plant motifs, of which only traces remain today. The white and green mosaic tilework near the top of the minaret is cited by Jonathan Bloom as the earliest reliably-dated example of ''zellij

''Zellij'' ( ar, الزليج, translit=zillīj; also spelled zillij or zellige) is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces. The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form various pa ...

'' in Morocco. Above this, the top edge of the minaret's main shaft is crowned by stepped merlon

A merlon is the solid upright section of a battlement (a crenellated parapet) in medieval architecture or fortifications.Friar, Stephen (2003). ''The Sutton Companion to Castles'', Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2003, p. 202. Merlons are sometimes ...

s. At this level there is an outdoor platform which can reached from inside the tower, and on which the smaller second shaft of the minaret stands. Inside the main shaft are six rooms in succession, one above the other, and the whole tower could be ascended via a wide interior ramp that allowed the ''mu'azzin

The muezzin ( ar, مُؤَذِّن) is the person who proclaims the call to the daily prayer ( ṣalāt) five times a day (Fajr prayer, Zuhr prayer, Asr prayer, Maghrib prayer and Isha prayer) at a mosque. The muezzin plays an important role i ...

'' to ride a horse to the top. The different arrangements on the exterior façade of the minaret correspond to the positions of the window openings situated at different points along the ascending ramp inside. The chambers inside are also enlivened with varying degrees of decoration, with the topmost (sixth) chamber being especially notable for its ornamental ribbed dome ceiling (similar to the domes of the Great Mosque of Cordoba) with ''muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

'' squinch

In architecture, a squinch is a triangular corner that supports the base of a dome. Its visual purpose is to translate a rectangle into an octagon. See also: pendentive.

Construction

A squinch is typically formed by a masonry arch that spans ...

es and geometric patterns.

The minaret is topped by a spire or finial

A finial (from '' la, finis'', end) or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the apex of a dome, spire, towe ...

(''jamur''). The finial includes gilded copper balls, decreasing in size towards the top, a traditional style of Morocco. A popular legend about the orbs, of which there are variations, claims that they are made of pure gold. The legend was originally associated with the minaret of the Kasbah Mosque further south (which has a similar finial), but is nowadays often associated with the Kutubiyya instead. One version of the legend claims that there were at one time only three of them and that the fourth was donated by the wife of Yaqub al-Mansur as penance for breaking her fast for three hours one day during Ramadan

, type = islam

, longtype = Religious

, image = Ramadan montage.jpg

, caption=From top, left to right: A crescent moon over Sarıçam, Turkey, marking the beginning of the Islamic month of Ramadan. Ramadan Quran reading in Bandar Torkaman, Iran. ...

. She had her golden jewelry melted down to form the fourth globe. Another version of the legend is that the balls were originally made entirely of gold fashioned from the jewellery of the wife of Saadian

The Saadi Sultanate (also rendered in English as Sa'di, Sa'did, Sa'dian, or Saadian; ar, السعديون, translit=as-saʿdiyyūn) was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of West Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was l ...

Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur. There is a flag pole next to the copper balls forming the spire, which is used for hoisting the religious green flag of the Prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

, which the mu'azzin does every Friday and on religious occasions.

Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque

History

The Kutubiyya Mosque's original ''minbar

A minbar (; sometimes romanized as ''mimber'') is a pulpit in a mosque where the imam (leader of prayers) stands to deliver sermons (, '' khutbah''). It is also used in other similar contexts, such as in a Hussainiya where the speaker sits a ...

'' (pulpit) was commissioned by Ali ibn Yusuf

Ali ibn Yusuf (also known as "Ali Ben Youssef") () (born 1084 died 26 January 1143) was the 5th Almoravid emir. He reigned from 1106–1143.

Biography

Ali ibn Yusuf was born in 1084 in Ceuta. He was the son of Yusuf ibn T ...

, one of the last Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century tha ...

rulers, and created by a workshop in Cordoba, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

(al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

). Its production started in 1137 and is estimated to have taken seven years. It is regarded as “one of the unsurpassed creations of Islamic art”. Its artistic style and quality was hugely influential and set a standard which was repeatedly imitated, but never surpassed, in subsequent minbars across Morocco and parts of Algeria. It is believed that the minbar was originally placed in the first Ben Youssef Mosque (named after Ali ibn Yusuf, but entirely rebuilt in later centuries). It was then transferred by the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

ruler Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

to the first Kutubiyya Mosque and was later moved to the second incarnation of that mosque. It remained there until 1962, when it was moved to the El Badi Palace

El Badi Palace ( ar, قصر البديع, lit=Palace of Wonder/Brilliance, also frequently translated as the "Incomparable Palace") or Badi' Palace is a ruined palace located in Marrakesh, Morocco. It was commissioned by the sultan Ahmad al-Man ...

where it is now on display for visitors.

Description

The minbar is an essentially triangular structure with thehypotenuse

In geometry, a hypotenuse is the longest side of a right-angled triangle, the side opposite the right angle. The length of the hypotenuse can be found using the Pythagorean theorem, which states that the square of the length of the hypotenuse e ...

side occupied by a staircase with nine steps. It is long, wide, and tall. The main structure is made in North African cedar wood, although the steps were made of walnut tree wood and the minbar's base was made with fir tree

Firs (''Abies'') are a genus of 48–56 species of evergreen coniferous trees in the family Pinaceae. They are found on mountains throughout much of North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa. The genus is most closely re ...

wood. The surfaces are decorated through a mix of marquetry

Marquetry (also spelled as marqueterie; from the French ''marqueter'', to variegate) is the art and craft of applying pieces of veneer to a structure to form decorative patterns, designs or pictures. The technique may be applied to case fur ...

and inlaid sculpted pieces. The large triangular faces of the minbar on either side are covered in an elaborate and creative motif centered around eight-pointed stars, from which decorative bands with ivory inlay then interweave and repeat the same pattern across the rest of the surface. The spaces between these bands form other geometric shapes which are filled with panels of deeply-carved arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

s, made from different coloured woods (boxwood

''Buxus'' is a genus of about seventy species in the family Buxaceae. Common names include box or boxwood.

The boxes are native to western and southern Europe, southwest, southern and eastern Asia, Africa, Madagascar, northernmost South ...

, jujube

Jujube (), sometimes jujuba, known by the scientific name ''Ziziphus jujuba'' and also called red date, Chinese date, and Chinese jujube, is a species in the genus '' Ziziphus'' in the buckthorn family Rhamnaceae.

Description

It is a smal ...

, and blackwood). There is a wide band of Quranic inscriptions in Kufic

Kufic script () is a style of Arabic script that gained prominence early on as a preferred script for Quran transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a reference and an archetype for a number of other Arabic scripts. It ...

script on blackwood and bone running along the top edge of the balustrades. The other surfaces of the minbar feature a variety of other motifs. Notably, the steps of the minbar are decorated with images of an arcade of Moorish (horseshoe) arches inside which are curving plant motifs, all made entirely in marquetry with different colored woods.

Mechanism moving the ''minbar'' and the ''maqsura''

Historical accounts describe a mysterious semi-automated mechanism in the Kutubiyya Mosque by which the minbar would emerge, seemingly on its own, from its storage chamber next to the mihrab and move forward into position for theimam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

's sermon. Likewise, the ''maqsura'' of the mosque (a wooden screen that separated the caliph and his entourage from the general public during prayers) was also retractable in the same manner and would emerge from the ground when the caliph attended prayers at the mosque, and then retract once he left. This mechanism, which elicited great curiosity and wonder from contemporary observers, was designed by an engineer from Malaga named Hajj al-Ya'ish, who also completed other projects for the caliph. Modern archaeological excavations carried out on the first Kutubiyya Mosque have found evidence confirming the existence of such a mechanism, though its exact workings are not fully established. One theory, which appears plausible from the physical evidence, is that it was powered by a hidden system of pulleys and counterweights.

See also

*Lists of mosques

Lists of mosques cover mosques, places of worship for Muslims. The lists include the most famous, largest and oldest mosques, and mosques mentioned in the Quran, as well as lists of mosques in each region and country of the world. The major region ...

* List of mosques in Africa

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

* List of mosques in Morocco

* Mohammed VI Mosque

*History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

The early domes of the Middle Ages, particularly in those areas recently under Byzantine control, were an extension of earlier Roman architecture. The domed church architecture of Italy from the sixth to the eighth centuries followed that of the ...

*Moorish Mosque, Kapurthala

The Moorish Mosque, Kapurthala situated in Kapurthala in the Indian State of Punjab is patterned on the lines of the Grand Mosque of Marrakesh, Morocco. It was commissioned by Maharajah Jagatjit Singh, the last ruler of Kapurthala. Kapurthala c ...

References

External links

Koutobia Mosque entry at ArchNet

(includes section of images with floor plan of mosque and photographs of its interior)

Kutubiya Mosque page at Discover Islamic Art

(includes picture of the upper chamber inside the minaret)

360-degree view of the area near the mihrab

posted on Google Maps

Manar al-Athar digital image archive

(including a range of exterior photo angles) {{Authority control Mosques in Marrakesh 12th-century mosques Almohad architecture Tourist attractions in Marrakesh Religious buildings and structures completed in 1195