Kingdom Of Pamplona on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kingdom of Navarre (; , , , ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona (), was a Basque kingdom that occupied lands on both sides of the western

Navarra

in the Auñamendi Entziklopedia (click on "NAVARRA – NAFARROA (NOMBRE Y EMBLEMAS)") of Latin appears in

The kingdom originated in the southern side of the western Pyrenees, in the flatlands around the city of

The kingdom originated in the southern side of the western Pyrenees, in the flatlands around the city of  The Franks renewed their attempts to control the region and in 806 took Navarre under their protection. Following a truce between the Frankish kingdom and Córdoba, in 812

The Franks renewed their attempts to control the region and in 806 took Navarre under their protection. Following a truce between the Frankish kingdom and Córdoba, in 812

After taking the political power from Fortún Garcés, Sancho Garcés (905–925), son of Dadilde, sister of Raymond I, Count of Pallars and Ribagorza, proclaimed himself king, terminating the alliance with the Emirate of Córdoba and expanding its domains through the course of the River Ega all the way south to the

After taking the political power from Fortún Garcés, Sancho Garcés (905–925), son of Dadilde, sister of Raymond I, Count of Pallars and Ribagorza, proclaimed himself king, terminating the alliance with the Emirate of Córdoba and expanding its domains through the course of the River Ega all the way south to the  In the year 1011 Sancho III married

In the year 1011 Sancho III married

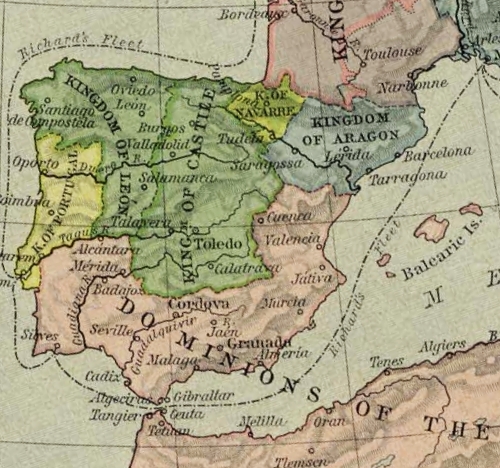

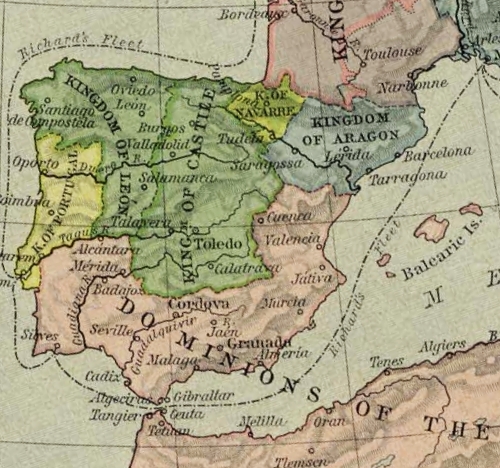

At its greatest extent the Kingdom of Navarre included all the modern Spanish province; the northern slope of the western Pyrenees the Spaniards called the ''ultra puertos'' ("country beyond the mountain passes") or French Navarre; the Basque provinces of Spain and France; the Bureba, the valley between the Basque mountains and the Montes de Oca to the north of

At its greatest extent the Kingdom of Navarre included all the modern Spanish province; the northern slope of the western Pyrenees the Spaniards called the ''ultra puertos'' ("country beyond the mountain passes") or French Navarre; the Basque provinces of Spain and France; the Bureba, the valley between the Basque mountains and the Montes de Oca to the north of

García Sánchez III (1035–1054) soon found himself struggling for supremacy against his ambitious brothers, especially Ferdinand. García had supported the armed conflict between Ferdinand and his brother-in-law

García Sánchez III (1035–1054) soon found himself struggling for supremacy against his ambitious brothers, especially Ferdinand. García had supported the armed conflict between Ferdinand and his brother-in-law

''The Restorer'' and

''The Restorer'' and  In 1199 Alfonso VIII of Castile, son of Sancho III of Castile and Blanche of Navarre, was determined to take over coastal Navarre, a strategic region that would allow Castile much easier access to European wool markets and would isolate Navarre as well. He launched a massive expedition against Navarre. Sancho the Strong was abroad in

In 1199 Alfonso VIII of Castile, son of Sancho III of Castile and Blanche of Navarre, was determined to take over coastal Navarre, a strategic region that would allow Castile much easier access to European wool markets and would isolate Navarre as well. He launched a massive expedition against Navarre. Sancho the Strong was abroad in

In spite of the treaties, Ferdinand the Catholic did not relinquish his long-cherished designs on Navarre. In 1506, the 53-year-old widower remarried, to

In spite of the treaties, Ferdinand the Catholic did not relinquish his long-cherished designs on Navarre. In 1506, the 53-year-old widower remarried, to

There were two more attempts at liberation in 1516 and 1521, both supported by popular rebellion, especially the second one. It was in 1521 that the Navarrese came closest to regaining their independence. As a liberation army commanded by General Asparros approached Pamplona, the citizens rose in revolt and besieged the military governor, Iñigo de Loyola, in his newly built castle. Tudela and other cities also declared their loyalty to the House of Albret. While at first distracted due to only recently overcoming the Revolt of the Comuneros, the Navarrese-Béarnese army managed to liberate all the Kingdom, but shortly thereafter Asparros faced a large Castilian army at the

There were two more attempts at liberation in 1516 and 1521, both supported by popular rebellion, especially the second one. It was in 1521 that the Navarrese came closest to regaining their independence. As a liberation army commanded by General Asparros approached Pamplona, the citizens rose in revolt and besieged the military governor, Iñigo de Loyola, in his newly built castle. Tudela and other cities also declared their loyalty to the House of Albret. While at first distracted due to only recently overcoming the Revolt of the Comuneros, the Navarrese-Béarnese army managed to liberate all the Kingdom, but shortly thereafter Asparros faced a large Castilian army at the

As the Kingdom of Navarre was originally organized, it was divided into ''

As the Kingdom of Navarre was originally organized, it was divided into ''

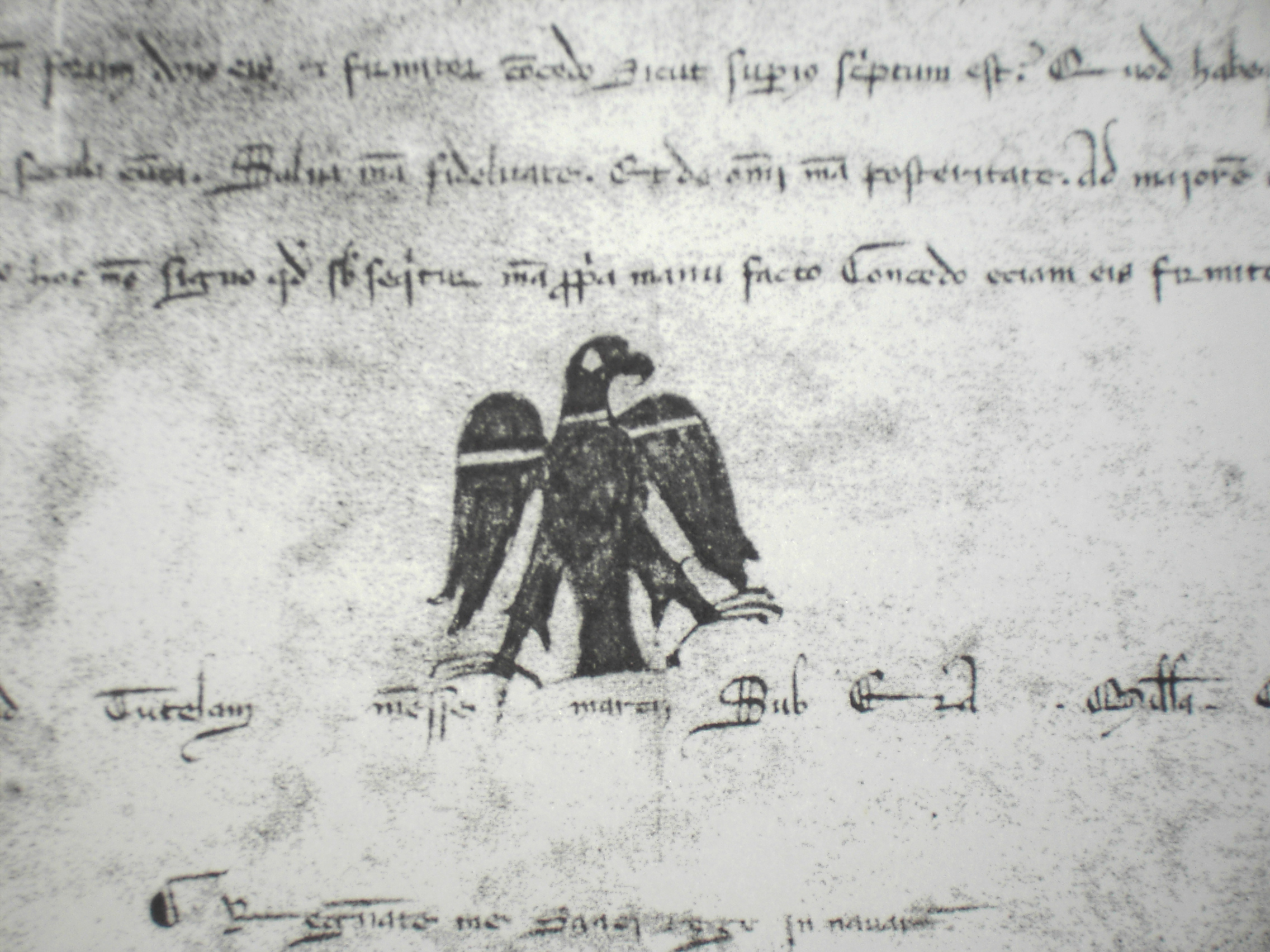

File:COA Navarre escarbuncles.svg, Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Navarre during the reign of Sancho VI

File:Sign of Sancho VII of Navarre.svg, Sign of Sancho VII

File:Seal of Sancho VII of Navarre.svg, Seal of Sancho VII

(reverse) File:Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Navarre.svg, Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Navarre, 1234–1580 File:Former Royal Badge of Navarre.svg, Royal Badge of the Medieval Monarchs of Navarre File:EstandNavarra.png, Standard of the Medieval Monarchs of Navarre since 1212

Medieval History of Navarre

Genealogy {{Authority control Basque history

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

, alongside the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

between present-day Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

The medieval state took form around the city of Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

during the first centuries of the Iberian Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

. The kingdom has its origins in the conflict in the buffer region between the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the L ...

and the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba that controlled most of the Iberian Peninsula. The city of Pamplona (; ), had been the main city of the indigenous Vasconic

The Vasconic languages (from Latin 'Basque') are a putative family of languages that includes Basque and the extinct Aquitanian language. The extinct Iberian language is sometimes putatively included.

The concept of the Vasconic languages is o ...

population and was located amid a predominantly Basque-speaking area. In an event traditionally dated to 824, Íñigo Arista

Íñigo Arista ( eu, Eneko, ar, ونّقه, ''Wannaqo'', c. 790 – 851 or 852) was a Basque leader, considered the first king of Pamplona. He is thought to have risen to prominence after the defeat of local Frankish partisans at the Battle of ...

was elected or declared ruler of the area around Pamplona in opposition to Frankish expansion into the region, originally as vassal to the Córdoba Emirate. This polity evolved into the Kingdom of Pamplona. In the first quarter of the 10th century, the Kingdom was able to briefly break its vassalage under Córdoba and expand militarily, but again found itself dominated by Córdoba until the early 11th century. A series of partitions and dynastic changes led to a diminution of its territory and to periods of rule by the kings of Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

(1054–1134) and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

(1285–1328).

In the 15th century, another dynastic dispute over control by the king of Aragon led to internal divisions and the eventual conquest of the southern part of the kingdom by Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia fro ...

in 1512 (permanently annexed in 1524). It was annexed by the Courts of Castile to the Crown of Castile in 1515. The remaining northern part of the kingdom was once again joined with France by personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

in 1589 when King Henry III of Navarre inherited the French throne as Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monar ...

, and in 1620 it was merged into the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

. The monarchs of this unified state took the title "King of France and Navarre" until its fall in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, and again during the Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* Ab ...

from 1814 until 1830 (with a brief interregnum in 1815).

Today, the ancient Kingdom of Navarre comprise the Spanish autonomous communities

eu, autonomia erkidegoa

ca, comunitat autònoma

gl, comunidade autónoma

oc, comunautat autonòma

an, comunidat autonoma

ast, comunidá autónoma

, alt_name =

, map =

, category = Autonomous administra ...

of Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

, and and the French community of .

Etymology

There are similar earlier toponyms but the first documentation Bernardo Estornés Lasa's Spanish article oNavarra

in the Auñamendi Entziklopedia (click on "NAVARRA – NAFARROA (NOMBRE Y EMBLEMAS)") of Latin appears in

Eginhard

Einhard (also Eginhard or Einhart; la, E(g)inhardus; 775 – 14 March 840) was a Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the ''Vita ...

's chronicle of the feats of Charles the Great.

Other Royal Frankish Annals

The ''Royal Frankish Annals'' (Latin: ''Annales regni Francorum''), also called the ''Annales Laurissenses maiores'' ('Greater Lorsch Annals'), are a series of annals composed in Latin in the Carolingian Francia, recording year-by-year the state ...

give ''nabarros''.

There are two proposed etymologies for the name of //:

* Basque (declined absolutive singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular homology

* SINGULAR, an open source Computer Algebra System (CAS)

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar ...

): "brownish", "multicolor", which would be a contrast with the green mountain lands north of the original County of Navarre.

* Basque , Castilian ("valley", "plain", present across Spain) + Basque ("people", "land").

The linguist Joan Coromines considers ''naba'' as not clearly Basque in origin but as part of a wider pre-Roman substrate.

Early historic background

Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

. According to Roman geographers such as Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

and Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, these regions were inhabited by the Vascones

The Vascones were a pre-Roman tribe who, on the arrival of the Romans in the 1st century, inhabited a territory that spanned between the upper course of the Ebro river and the southern basin of the western Pyrenees, a region that coincides wi ...

and other related Vasconic-Aquitani

The Aquitani were a tribe that lived in the region between the Pyrenees, the Atlantic ocean, and the Garonne, in present-day southwestern France in the 1st century BCE. The Romans dubbed this region '' Gallia Aquitania''. Classical authors such ...

an tribes, a pre-Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

group of peoples who inhabited the southern slopes of the western Pyrenees and part of the shore of the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

. These tribes spoke an archaic version of the Basque language, usually known by linguistics as Proto-Basque

Proto-Basque ( eu, aitzineuskara; es, protoeuskera, protovasco; french: proto-basque), or Pre-Basque, is the reconstructed predecessor of the Basque language before the Roman conquests in the Western Pyrenees.

Background

The first linguist w ...

, as well as some other related languages, such as the Aquitanian language

The Aquitanian language was the language of the ancient Aquitani, spoken on both sides of the western Pyrenees in ancient Aquitaine (approximately between the Pyrenees and the Garonne, in the region later known as Gascony) and in the areas sout ...

. The Romans took full control of the area by 74 BC, but unlike their northern neighbors, the Aquitanians, and other tribes from the Iberian Peninsula, the Vascones negotiated their status within the Roman Empire. The region first was part of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

, then of the Hispania Tarraconensis

Hispania Tarraconensis was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania. It encompassed much of the northern, eastern and central territories of modern Spain along with modern northern Portugal. Southern Spain, the region now called Andalusia was the ...

. It would be under the jurisdiction of the of Caesaraugusta (modern Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

).

The Roman empire influenced the area in urbanization, language, infrastructure, commerce, and industry. During the Sertorian War

The Sertorian War was a civil war fought from 80 to 72 BC between a faction of Roman rebels ( Sertorians) and the government in Rome (Sullans). The war was fought on the Iberian Peninsula (called ''Hispania'' by the Romans) and was one of the ...

, Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

would command the foundation of a city in Vasconic territory, giving origin to ''Pompaelo'', modern-day Pamplona, founded on a previously existent Vasconic town. Romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

of the Vascones led to their eventual adoption of forms of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

that would evolve into the Navarro-Aragonese

Navarro-Aragonese is a Romance language once spoken in a large part of the Ebro River basin, south of the middle Pyrenees, although it is only currently spoken in a small portion of its original territory. The areas where it was spoken might have ...

language, though the Basque language would remain widely spoken, especially in rural and mountainous areas.

After the decline of the Western Roman Empire, the Vascones were slow to be incorporated into the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

, which was in a civil war that provided the opportunity for the Umayyad conquest of Hispania

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania, also known as the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, was the initial expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate over Hispania (in the Iberian Peninsula) from 711 to 718. The conquest resulted in the decline of t ...

. The Basque leadership probably joined in the appeal that, in the hope of stability, brought the Muslim conquerors. By 718, Pamplona had formed a pact that allowed a wide degree of autonomy in exchange for military and political subjugation, along with the payment of tribute to Córdoba. Burial ornamentation shows strong contacts with the Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gaul ...

France and the Gascons of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Janu ...

, but also items with Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

ic inscriptions, while a Muslim cemetery in Pamplona, the use of which spanned several generations, suggests the presence of a Muslim garrison in the decades following the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

invasion.

The origin and foundation of the Kingdom of Pamplona is intrinsically related to the southern expansion of the Frankish kingdom under the Merovingians

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

and their successors, the Carolingians

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippi ...

. About 601, the Duchy of Vasconia () was established by the Merovingians, based around Roman Novempopulania

Novempopulania (Latin for "country of the nine peoples") was one of the provinces created by Diocletian (Roman emperor from 284 to 305) out of Gallia Aquitania, which was also called ''Aquitania Tertia''.

Early Roman period

The area of Novemp ...

and extending from the southern branch of the river Garonne

The Garonne (, also , ; Occitan, Catalan, Basque, and es, Garona, ; la, Garumna

or ) is a river of southwest France and northern Spain. It flows from the central Spanish Pyrenees to the Gironde estuary at the French port of Bordeaux – ...

to the northern side of the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

. The first documented Duke of Vasconia was Genial

Genial (Latin ''Genialis'' or ''Genealis'') was the Duke of Gascony ('' Vasconia'') in the early seventh century. He is mentioned in the ''Chronicle of Fredegar''.

Genial was probably a Frank or a Gallo-Roman when Theuderic II and Theudebert II ...

, who would hold that position until 627.

The Duchy of Vasconia then became a frontier territory with varying levels of autonomy granted by the Merovingian monarchs. The suppression of the Duchy of Vasconia as well as the Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine ( oc, Ducat d'Aquitània, ; french: Duché d'Aquitaine, ) was a historical fiefdom in western, central, and southern areas of present-day France to the south of the river Loire, although its extent, as well as its name, flu ...

by the Carolingians would lead to a rebellion, led by Lupo II of Gascony. Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

launched a punitive War in Aquitaine (760–768) that put down the uprising and resulted in the division of the Duchy into several counties, ruled from Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and fr ...

. Similarly, across the eastern Pyrenees the Marca Hispánica was established next to the Marca Gothica, a Frankish attempt at creating buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between t ...

s between the Carolingian empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the L ...

and the Emirate of Córdoba

The Emirate of Córdoba ( ar, إمارة قرطبة, ) was a medieval Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula. Its founding in the mid-eighth century would mark the beginning of seven hundred years of Muslim rule in what is now Spain and Po ...

.

The Franks under Charlemagne extended their influence and control southward, occupying several regions of the north and east of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

. It is unclear how solidly the Franks exercised control over Pamplona. In 778, Charlemagne was invited by rebellious Muslim lords on the Upper March

The Upper March (in ar, الثغر الأعلى, ''aṯ-Tagr al-A'la''; in Spanish: ''Marca Superior'') was an administrative and military division in northeast Al-Andalus, roughly corresponding to the Ebro valley and adjacent Mediterranean coa ...

of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

to lead an expedition south with the intention of taking the city of Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

from the Emirate of Córdoba. However, the expedition was a failure, and the Frankish army was forced to withdraw. During their retreat, they destroyed the city walls of Pamplona to weaken the city and avoid a possible rebellion, reminiscent of the approach the Carolingians had used elsewhere against Christian cities that seemed content to live under Córdoban control.

However, while moving through the Pyrenees on 15 August 778, the rearguard of the Frankish army, led by Roland

Roland (; frk, *Hrōþiland; lat-med, Hruodlandus or ''Rotholandus''; it, Orlando or ''Rolando''; died 15 August 778) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the ...

was attacked by the Basque tribes in a confrontation that came to be known as the Battle of Roncevaux Pass

The Battle of Roncevaux Pass ( French and English spelling, ''Roncesvalles'' in Spanish, ''Orreaga'' in Basque) in 778 saw a large force of Basques ambush a part of Charlemagne's army in Roncevaux Pass, a high mountain pass in the Pyrenees on ...

. Roland

Roland (; frk, *Hrōþiland; lat-med, Hruodlandus or ''Rotholandus''; it, Orlando or ''Rolando''; died 15 August 778) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the ...

was killed and the rearguard scattered. As a response to the attempted Frankish seizure of Zaragoza, the Córdoban emir retook the city of Pamplona and its surrounding lands. In 781 two local Basque lords, ''Ibn Balask'' ("son of Velasco"), and ''Mothmin al-Akra'' ("Jimeno ''the Strong''") were defeated and forced to submit. The next mention of Pamplona is in 799, when Mutarrif ibn Musa, thought to have been a governor of the city and a member of the muwallad Banu Qasi

The Banu Qasi, Banu Kasi, Beni Casi ( ar, بني قسي or بنو قسي, meaning "sons" or "heirs of Cassius"), Banu Musa, or al-Qasawi were a Muladí (local convert) dynasty that in the 9th century ruled the Upper March, a frontier te ...

family, was killed there by a pro-Frankish faction.

During this period, Basque territory extended on the west to somewhere around the headwaters of the Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

river. Equally Einhart's ''Vita Karoli Magni'' pinpoints the source of the Ebro in the land of the Navarrese. However, this western region fell under the influence of the Kingdom of Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of ...

.

Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqu ...

went to Pamplona, likely to establish there a county that would prove short-lived. However, continued rebellion in Gascony rendered Frankish control south of the Pyrenees tenuous, and the Emirate was able to reclaim the region following victory in the 816 Battle of Pancorbo, in which they defeated and killed the "enemy of Allah", ''Balask al-Yalaski'' (Velasco the Gascon), along with the uncle of Alfonso II of Asturias

Alfonso II of Asturias (842), nicknamed the Chaste ( es, el Casto), was the king of Asturias during two different periods: first in the year 783 and later from 791 until his death in 842. Upon his death, Nepotian, a family member of undeter ...

, Garcia ibn Lubb ('son of Lupus'), Sancho, the 'premier knight of Pamplona', and the pagan warrior ''Ṣaltān''. North of the Pyrenees in the same year, Louis the Pious removed Seguin as Duke of Vasconia, which initiated a rebellion,

led by Garcia Jiménez, who was killed in 818. Louis's son Pepin, then King of Aquitaine, stamped out the Vasconic revolt in Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

then hunted the chieftains who had taken refuge in southern Vasconia, i.e., Pamplona and Navarre, no longer controlled by the Franks. He sent an army led by the counts Aeblus Aeblus, Ebalus, or Ebles was a Frankish count in Gascony early in the ninth century.

With Aznar Sánchez, he led a large expedition across the Pyrenees to re-establish control over Navarre. After accomplishing their goals and entering Pamplona w ...

and Aznar Sanchez (the latter being appointed lord, but not duke, of Vasconia by Pepin after suppressing the uprising in the Duchy), accomplishing their goals with no resistance in Pamplona (which still lacked walls after the 778 destruction). On the way back, however, they were ambushed and defeated in Roncevaux by a force probably composed both of Basques and the Córdoba-allied muwallad Banu Qasi

The Banu Qasi, Banu Kasi, Beni Casi ( ar, بني قسي or بنو قسي, meaning "sons" or "heirs of Cassius"), Banu Musa, or al-Qasawi were a Muladí (local convert) dynasty that in the 9th century ruled the Upper March, a frontier te ...

.

Nascent state and kingdom

Establishment by Iñigo Arista

Out of the pattern of competing Frankish and Córdoban interests, the Basque chieftainÍñigo Arista

Íñigo Arista ( eu, Eneko, ar, ونّقه, ''Wannaqo'', c. 790 – 851 or 852) was a Basque leader, considered the first king of Pamplona. He is thought to have risen to prominence after the defeat of local Frankish partisans at the Battle of ...

took power. Tradition tells he was elected as king of Pamplona in 824, giving rise to a dynasty of kings in Pamplona that would last for eighty years. However, the region around Pamplona continued to fall within the sphere of influence of Córdoba, presumably as part of its broader frontier region, the Upper March

The Upper March (in ar, الثغر الأعلى, ''aṯ-Tagr al-A'la''; in Spanish: ''Marca Superior'') was an administrative and military division in northeast Al-Andalus, roughly corresponding to the Ebro valley and adjacent Mediterranean coa ...

, ruled by Íñigo's half-brother, Musa ibn Musa al-Qasawi. The city was allowed to remain Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

and have its own administration but had to pay the traditional taxes to the Emirate, including the ''jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

'' assessed on non-Muslims living under their control. Íñigo Arista is mentioned in Arab records as ''sâhib'' (lord) or ''amîr'' of the Vascones (''bashkunish'') and not as ''malik'' (king) or ''tâgiya'' (tyrant) used for the kings of Asturias and France, indicating the lower status of these ''ulûj'' (barbarians, not accepting Islam) within the Córdoba sphere. In 841, in concert with Musa ibn Musa, Íñigo rebelled. Although Musa was eventually forced to submit, Íñigo was still in rebellion at the time of his death in 851/2.

Pamplona and Navarre are distinguished in Carolingian chronicles. Pamplona is cited in 778 as a Navarrese stronghold, which may be due to their lack of information about the Basque territory. The chronicles did distinguish between Navarre and its main town in 806 (''"In Hispania, vero Navarrensis et Pampelonensis"''), while the ''Chronicle of Fontenelle'' refers to "''Induonis et Mitionis, ducum Navarrorum''" (Induo �ñigo Aristaand Mitio erhaps Jimeno dukes of the Navarrese). However, Arab chroniclers make no such distinctions, and just refer to the ''Baskunisi'', a transliteration of ''Vascones

The Vascones were a pre-Roman tribe who, on the arrival of the Romans in the 1st century, inhabited a territory that spanned between the upper course of the Ebro river and the southern basin of the western Pyrenees, a region that coincides wi ...

'', since a big majority of the population was Basque. The primitive Navarre may have comprised the valleys of Goñi, Gesalaz, Lana, Allin, Deierri, Berrueza and Mañeru, which later formed the ''merindad'' of Estella.

The role of Pamplona as a focus coordinating both rebellion against and accommodation with Córdoba seen under Íñigo would continue under his son, García Íñiguez (851/2–882), who formed alliances with Asturias, Gascons, Aragonese and with families in Zaragoza opposed to Musa ibn Musa. This established a pattern of raids and counter-raids, capturing slaves and treasure, as well as full military campaigns that would restore full Córdoban control with renewed oaths of fidelity. His son Fortún Garcés (882-905) spent two decades in Córdoban captivity before succeeding in Pamplona as vassal of the Emirate. Neither of these kings would make significant territorial expansion. This period of a fractious, but in the end subservient, Navarre came to an end amidst a period when generalized rebellion within the Emirate prevented them from being able to suppress the inertial forces in the western Pyrenees. The ineffectual Fortún was forced to abdicate in favor of a new dynasty from the vehemently anti-Muslim east of Navarre, the founders of which took a less accommodationist view. With this change, al-Andalus sources shift to calling the Pamplona rulers 'tyrants', as with the independent kings of Asturias: Pamplona had passed out of the Córdoban sphere.

Jiménez rule

Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

and taking the regions of Nájera and Calahorra, which caused the decline of the Banu Qasi

The Banu Qasi, Banu Kasi, Beni Casi ( ar, بني قسي or بنو قسي, meaning "sons" or "heirs of Cassius"), Banu Musa, or al-Qasawi were a Muladí (local convert) dynasty that in the 9th century ruled the Upper March, a frontier te ...

family, who ruled these lands. As a response, Abd-ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 9 ...

undertook two expeditions to these lands, earning a victory at the Battle of Valdejunquera, after which the Emirate retook the lands south of the river Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

, and by 924 attacked Pamplona. The daughter of Sancho Garcés, Sancha, was married to the King of Leon Ordoño II, establishing an alliance with the Leonese kingdom and ensuring the Calahorra region. The valleys of the river Aragón and river Gállego all the way down to Sobrarbe

Sobrarbe is one of the comarcas of Aragon, Spain. It is located in the northern part of the province of Huesca, part of the autonomous community of Aragon in Spain. Many of its people speak the Aragonese language locally known as ''fabla''.

T ...

also ended up under control of Pamplona, and to the west the lands of the kingdom reached the counties of Álava and Castile, which were under control of the Kingdom of Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of ...

. The kingdom had at this time an extent of about 15,000 km. The Chronicle of Albelda

The ''Codex Vigilanus'' or ''Codex Albeldensis'' (Spanish: ''Códice Vigilano'' or ''Albeldense'') is an illuminated compilation of various historical documents accounting for a period extending from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania. ...

(last updated in 976) outlines the extent in 905 of the Kingdom of Pamplona for the first time. It extended to Nájera and ''Arba'' (arguably Araba). Some historians believe that this suggests that it included the Western Basque Country as well:

After the death of Sancho Garcés, the crown passed to his brother, Jimeno Garcés Jimeno (also Gimeno, Ximeno, Chemene, Exemeno) is a given name derived from ''Ximen'',OMAECHEVARRIA, Ignacio, "Nombres propios y apellidos en el País Vasco y sus contornos". ''Homenaje a D. Julio de Urquijo'', volume II, pages 153-175. a variant of ...

(925–931), joined by Sancho's underage son, García Sánchez (931–970), in his last year. García continued to rule under the tutelage of his mother, Sancho's widow Toda Aznarez, who also engineered several political marriages with the other Christian kingdoms and counties of northern Iberia. Oneca was married to Alfonso IV of León

Alfonso IV (s933), called the Monk ( es, el Monje), was King of León from 925 (or 926) and King of Galicia from 929, until he abdicated in 931.

When Ordoño II died in 924 it was not one of his sons who ascended to the throne of León but ra ...

and her sister Urraca Urraca (also spelled ''Hurraca'', ''Urracha'' and ''Hurracka'' in medieval Latin) is a female first name. In Spanish, the name means magpie, derived perhaps from Latin ''furax'', meaning "thievish", in reference to the magpie's tendency to collec ...

to Ramiro II of León

Ramiro II (c. 900 – 1 January 951), son of Ordoño II and Elvira Menendez, was a King of León from 931 until his death. Initially titular king only of a lesser part of the kingdom, he gained the crown of León (and with it, Galicia) after su ...

, while other daughters of Sancho were married to counts of Castile, Álava

Álava ( in Spanish) or Araba (), officially Araba/Álava, is a Provinces of Spain, province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Country, heir of the ancient Basque señoríos#Lords of Álav ...

and Bigorre

Bigorre ({{IPA-fr, biɡɔʁ; Gascon: ''Bigòrra'') is a region in southwest France, historically an independent county and later a French province, located in the upper watershed of the Adour, on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees, part of th ...

. The marriage of the Pamplonese king García Sánchez with Andregoto Galíndez, daughter of Galindo Aznárez II, Count of Aragon

The County of Aragon ( an, Condato d'Aragón) or County of Jaca ( an, Condato de Chaca, link=no) was a small Frankish marcher county in the central Pyrenean valley of the Aragon river, comprising Ansó, Echo, and Canfranc and centered on the sm ...

linked the eastern county to the Kingdom. In 934, he invited Abd-ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 9 ...

to intervene in the kingdom in order to emancipate himself from his mother, and this began a period of tributary status by Pamplona and frequent punitive campaigns from Córdoba.

García Sánchez's heir, Sancho II (970–994), set up his half brother, Ramiro Garcés of Viguera, to rule in the short-lived Kingdom of Viguera. The ''Historia General de Navarra'' by Jaime del Burgo says that on the occasion of the donation of the villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became ...

of Alastue by the king of Pamplona to the monastery of San Juan de la Peña in 987, he styled himself "King of Navarre", the first time that title had been used. In many places he appears as the first King of Navarre and in others the third; however, he was at least the seventh king of Pamplona

The Kingdom of Navarre (; , , , ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona (), was a Basque kingdom that occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, alongside the Atlantic Ocean between present-day Spain and France.

The medieval state to ...

.

During the late 10th century, Almanzor

Abu ʿĀmir Muḥammad ibn ʿAbdullāh ibn Abi ʿĀmir al-Maʿafiri ( ar, أبو عامر محمد بن عبد الله بن أبي عامر المعافري), nicknamed al-Manṣūr ( ar, المنصور, "the Victorious"), which is often Latiniz ...

, the ruler of Al Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mu ...

, frequently led raids against the Christian kingdoms, and attacked the Pamplonese lands on at least nine occasions. In 966, clashes between the Islamic factions and the Kingdom resulted in the loss of Calahorra and the valley of the river Cidacos. Sancho II, while allied with Castilian militias, suffered a grave defeat in the Battle of Torrevicente. Sancho II was forced to hand over one of his daughters and one of his sons as tokens of peace. After the death of Sancho II and during the reign of García Sánchez II, Pamplona was attacked by the Caliphate on several occasions, being completely destroyed in 999, the King himself killed during a raid in the year 1000.

After the death of García Sánchez II, the crown passed to Sancho III, just eight years old at the time, and probably completely controlled by the Caliphate. During the first years of his reign the Kingdom was ruled by his cousins Sancho and García of Viguera until the year 1004, when Sancho III would become ruling king, mentored by his mother Jimena Fernández. The links with Castile became stronger through marriages. The death of Almanzor in 1002 and his successor Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam ( ar, عبد الملك ابن مروان ابن الحكم, ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam; July/August 644 or June/July 647 – 9 October 705) was the fifth Umayyad caliph, ruling from April 685 ...

in 1008 caused the decline of the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خلافة قرطبة; transliterated ''Khilāfat Qurṭuba''), also known as the Cordoban Caliphate was an Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and part ...

and the progress of the County of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th cen ...

south, while Pamplona, led by Sancho Garcés III, strengthen the position of his kingdom on the borderlands of the Taifa of Zaragoza

The taifa of Zaragoza () was an independent Arab Muslim state in the east of Al-Andalus (present day Spain), which was established in 1018 as one of the taifa kingdoms, with its capital in Saraqusta (Zaragoza) city. Zaragoza's taifa emerged in ...

, controlling the territories of Loarre

Loarre is a municipality in the province of Huesca, Spain. As of 2010, it had a population of 371 inhabitants.

See also

* Loarre Castle

The Castle of Loarre is a Romanesque Castle and Abbey located near the town of the same name, Huesca P ...

, Funes, Sos

is a Morse code distress signal (), used internationally, that was originally established for maritime use. In formal notation is written with an overscore line, to indicate that the Morse code equivalents for the individual letters of "SOS" ...

, Uncastillo

Uncastillo ( Aragonese: Uncastiello) is a municipality in the province of Zaragoza, Aragon, eastern Spain. At the 2010 census,Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain) it had a population of 781.

Along with Sos d'o Rei Catolico, Exeya d'os C ...

, Arlas, Caparroso

Caparroso is a town and municipality located in the province and autonomous community of Navarre, in the north of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_mo ...

and Boltaña

Boltaña (in Aragonese: ''Boltanya'') is a municipality located in the province of Huesca, Aragon, Spain. According to the 2004 census ( INE), the municipality has a population of 870 inhabitants.

Boltaña is the economic development capital of ...

.

Muniadona of Castile

Muniadona of Castile (1066), also called Mayor or Munia, was Queen of Pamplona (10111035) by her marriage with King Sancho Garcés III, who later added to his domains the Counties of Ribagorza (1017) and Castile (1028) using her dynastic rights t ...

, daughter of the Count of Castile

This is a list of counts of Castile.

The County of Castile had its origin in a fortified march on the eastern frontier of the Kingdom of Asturias. The earliest counts were not hereditary, being appointed as representatives of the Asturian king. Fr ...

Sancho García. In 1016 the County of Castile and the Kingdom of Navarre made a pact on their future expansion: Pamplona would expand towards the south and east, the eastern region of Soria

Soria () is a municipality and a Spanish city, located on the Douro river in the east of the autonomous community of Castile and León and capital of the province of Soria. Its population is 38,881 ( INE, 2017), 43.7% of the provincial populati ...

and the Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

valley, including territories that were at the time part of Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

. Thus, the Kingdom of Pamplona comprised a territory of 15,000 km2 between Pamplona, Nájera and Aragón with vassals of Pamplonese and Aragonese origin.

The assassination of Count García Sánchez of Castile in 1028 allowed Sancho to appoint his younger son Ferdinand as count. He also exerted a protectorate over the Duchy of Gascony

The Duchy of Gascony or Duchy of Vasconia ( eu, Baskoniako dukerria; oc, ducat de Gasconha; french: duché de Gascogne, duché de Vasconie) was a duchy located in present-day southwestern France and northeastern Spain, an area encompassing the m ...

. He seized the country of the Pisuerga and the Cea, which belonged to the Kingdom of León

The Kingdom of León; es, Reino de León; gl, Reino de León; pt, Reino de Leão; la, Regnum Legionense; mwl, Reino de Lhion was an independent kingdom situated in the northwest region of the Iberian Peninsula. It was founded in 910 when t ...

, and marched armies to the heart of that kingdom, forcing king Bermudo III of León

Bermudo III or Vermudo III (c. 1015– 4 September 1037) was the king of León from 1028 until his death. He was a son of Alfonso V of León by his first wife Elvira Menéndez, and was the last scion of Peter of Cantabria to rule in the Leones ...

to flee to a Galician refuge. Sancho thereby effectively ruled the north of Iberia from the boundaries of Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

to those of the count of Barcelona.

By the time of the death of Sancho III in 1035, the Kingdom had reached its greatest historical extent. Sancho III wrote a problematic will, in which he divided his territory into three kingdoms.

Ecclesiastical affairs

In this period of independence, the ecclesiastical affairs of the country reached a high state of development. Sancho the Great was brought up at Leyre, which was also for a short time the capital of the Diocese of Pamplona. Beside this see, there existed the Bishopric of Oca, which was united in 1079 to the Diocese of Burgos. In 1035 Sancho III re-established the See of Palencia, which had been laid waste at the time of the Moorish invasion. When, in 1045, the city of Calahorra was wrested from the Moors, under whose dominion it had been for more than three hundred years, a see was also founded there, which in the same year absorbed the Diocese of Najera and, in 1088, the Diocese of Alava, the jurisdiction of which covered about the same ground as that of the present Diocese of Vitoria. The See of Pamplona owed its re-establishment to Sancho III, who for this purpose convened a synod at Leyre in 1022 and one at Pamplona in 1023. These synods likewise instituted a reform of ecclesiastical life, with the above-named convent as a centre.Dismemberment

Division of Sancho's domains

At its greatest extent the Kingdom of Navarre included all the modern Spanish province; the northern slope of the western Pyrenees the Spaniards called the ''ultra puertos'' ("country beyond the mountain passes") or French Navarre; the Basque provinces of Spain and France; the Bureba, the valley between the Basque mountains and the Montes de Oca to the north of

At its greatest extent the Kingdom of Navarre included all the modern Spanish province; the northern slope of the western Pyrenees the Spaniards called the ''ultra puertos'' ("country beyond the mountain passes") or French Navarre; the Basque provinces of Spain and France; the Bureba, the valley between the Basque mountains and the Montes de Oca to the north of Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

; and the Rioja and Tarazona in the upper valley of the Ebro. On his death, Sancho divided his possessions among his four sons. Sancho the Great's realm was never again united (until Ferdinand the Catholic

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

): Castile was permanently joined to Leon, whereas Aragon enlarged its territory, joining Catalonia through a marriage.

Following the traditional succession customs, the first-born son of Sancho III, García Sánchez III, received the title and lands of the Kingdom of Pamplona, which included the territory of Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

, Nájera and parts of Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

. The rest of the territory was given to his widow Muniadona to split among all the legitimate sons: thus García Sánchez III also received the territory to the northeast from the County of Castile (La Bureba

La Bureba is a ''comarca'' located in the northeast of the Province of Burgos in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is bounded on the north by Las Merindades, east by the Comarca del Ebro, south-east by the Montes de Oca and ...

, Montes de Oca) and the County of Álava. Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

received the rest of the County of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th cen ...

and the lands between the Pisuerga and the Cea. Another son of Sancho, Gonzalo, received the counties of Sobrarbe

Sobrarbe is one of the comarcas of Aragon, Spain. It is located in the northern part of the province of Huesca, part of the autonomous community of Aragon in Spain. Many of its people speak the Aragonese language locally known as ''fabla''.

T ...

and Ribargoza as vassal of his eldest brother, García. Lands in Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

were allotted to Sancho's bastard son Ramiro.

Partition and union with Aragon

Bermudo III of León

Bermudo III or Vermudo III (c. 1015– 4 September 1037) was the king of León from 1028 until his death. He was a son of Alfonso V of León by his first wife Elvira Menéndez, and was the last scion of Peter of Cantabria to rule in the Leones ...

, who was ultimately killed in the Battle of Tamarón

The Battle of Tamarón took place on 4 September 1037 between Ferdinand, Count of Castile, and Vermudo III, King of León. Ferdinand, who had married Vermudo's sister Sancha, defeated and killed his brother-in-law near Tamarón, Spain, after ...

(1037). This allowed Ferdinand to unite his Castilian county with the new-won crown of León as king Ferdinand I. For several years a mutual collaboration between the two kingdoms took place. The relationship between García and his step-brother Ramiro was better. The latter had acquired all of Aragon, Ribagorza and Sobrarbe on the sudden death of his brother Gonzalo, forming what would become the Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon ( an, Reino d'Aragón, ca, Regne d'Aragó, la, Regnum Aragoniae, es, Reino de Aragón) was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon ...

. García and Ramiro's alliance with Ramon Berenguer, the Count of Barcelona

The Count of Barcelona ( ca, Comte de Barcelona, es, Conde de Barcelona, french: Comte de Barcelone, ) was the ruler of the County of Barcelona and also, by extension and according with the Usages of Barcelona, usages and Catalan constitutions, of ...

, was effective to keep the Muslim Taifa of Zaragoza

The taifa of Zaragoza () was an independent Arab Muslim state in the east of Al-Andalus (present day Spain), which was established in 1018 as one of the taifa kingdoms, with its capital in Saraqusta (Zaragoza) city. Zaragoza's taifa emerged in ...

at bay. After the capture of Calahorra in 1044, a period peace followed on the southern border and trade was established with Zaragoza.

The relationship between García and Ferdinand deteriorated with time, the two disputing the lands on the Pamplonese-Castilian border, and ended violently in September 1054 at the Battle of Atapuerca

The Battle of Atapuerca was fought on 1 September 1054 at the site of Piedrahita ("standing stone") in the valley of Atapuerca between two brothers, King García Sánchez III of Navarre and King Ferdinand I of Castile.

The Castilians won and Ki ...

, in which García was killed, and Ferdinand took from Pamplona the lands in La Bureba

La Bureba is a ''comarca'' located in the northeast of the Province of Burgos in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is bounded on the north by Las Merindades, east by the Comarca del Ebro, south-east by the Montes de Oca and ...

and the Tirón River.

García was succeeded by Sancho IV (1054–1076) ''of Peñalén'', whom Ferdinand had recognised as king of Pamplona immediately after the death of his father. He was fourteen years old at the time, and under the regency of his mother Estefanía and his uncles Ferdinand and Ramiro. After the death of his mother in 1058, Sancho IV lost the support of the local nobility, and the relations between them worsened after he became allied with Ahmad al-Muqtadir

Ahmad ibn Sulayman al-Muqtadir (or just Moctadir; ar, أبو جعفر أحمد "المقتدر بالله" بن سليمان, ''Abu Ja'far Ahmad al-Muqtadir bi-Llah ibn Sulayman'') was a member of the Banu Hud family who ruled the Islamic taifa ...

, ruler of Zaragoza. On 4 June 1076, a conspiracy involving Sancho IV's brother Ramón and sister Ermesinda ended with the murder of the king. The neighboring kingdoms and the nobility probably had a part in the plot.

The dynastic crisis resulting from Sancho's assassination worked to the benefit of the Castilian and Aragonese monarchs. Alfonso VI of León and Castile took control of La Rioja

La Rioja () is an autonomous community and province in Spain, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, an ...

, the Lordship of Biscay

The Lordship of Biscay ( es, Señorío de Vizcaya, Basque: ''Bizkaiko jaurerria'') was a region under feudal rule in the region of Biscay in the Iberian Peninsula between 1040 and 1876, ruled by a political figure known as the Lord of Biscay. On ...

, the County of Álava, the County of Durango and part of Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa (, , ; es, Guipúzcoa ; french: Guipuscoa) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French de ...

. Sancho Ramírez, successor to his father, Ramiro of Aragon, took control of the rest of the territory and was recognised as king by the Pamplonese nobility. The land around the city of Pamplona, the core of the original kingdom, became known as the County of Navarre, and was recognised by Alfonso VI as a vassal state of the kingdom of León and Castile. Sancho Ramírez began in 1084 a renewed military expansion of the southern lands controlled by Muslim forces. That year, the city of Arguedas, from which the Bardenas region could be controlled, was taken. After the death of Sancho Ramírez in 1094, he was succeeded by Peter I Peter I may refer to:

Religious hierarchs

* Saint Peter (c. 1 AD – c. 64–88 AD), a.k.a. Simon Peter, Simeon, or Simon, apostle of Jesus

* Pope Peter I of Alexandria (died 311), revered as a saint

* Peter I of Armenia (died 1058), Catholicos ...

, who resumed the expansion of the territory, taking the cities of Sádaba in 1096 and Milagro in 1098, while threatening Tudela Tudela may refer to:

*Tudela, Navarre, a town and municipality in northern Spain

** Benjamin of Tudela Medieval Jewish traveller

** William of Tudela, Medieval troubadour who wrote the first part of the ''Song of the Albigensian Crusade''

** Ba ...

.

Alfonso the Battler

Alfonso I (''c''. 1073/10747 September 1134), called the Battler or the Warrior ( es, el Batallador), was King of Aragon and Navarre from 1104 until his death in 1134. He was the second son of King Sancho Ramírez and successor of his brother P ...

(1104–1134), brother of Peter I, secured for the country its greatest territorial expansion. He wrested Tudela Tudela may refer to:

*Tudela, Navarre, a town and municipality in northern Spain

** Benjamin of Tudela Medieval Jewish traveller

** William of Tudela, Medieval troubadour who wrote the first part of the ''Song of the Albigensian Crusade''

** Ba ...

from the Moors (1114), re-conquered the entire country of Bureba, which Navarre had lost in 1042, and advanced into the current Province of Burgos

The Province of Burgos is a province of northern Spain, in the northeastern part of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is bordered by the provinces of Palencia, Cantabria, Vizcaya, Álava, La Rioja, Soria, Segovia, and Valladoli ...

. He also annexed Labourd

Labourd ( eu, Lapurdi; la, Lapurdum; Gascon: ''Labord'') is a former French province and part of the present-day Pyrénées Atlantiques ''département''. It is one of the traditional Basque provinces, and identified as one of the territorial c ...

, with its strategic port of Bayonne

Bayonne (; eu, Baiona ; oc, label= Gascon, Baiona ; es, Bayona) is a city in Southwestern France near the Spanish border. It is a commune and one of two subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine r ...

, but lost its coastal half to the English soon after. The remainder has been part of Navarre since then and eventually came to be known as Lower Navarre

Lower Navarre ( eu, Nafarroa Beherea/Baxenabarre; Gascon/Bearnese: ''Navarra Baisha''; french: Basse-Navarre ; es, Baja Navarra) is a traditional region of the present-day French ''département'' of Pyrénées-Atlantiques. It corresponds to the ...

. Toward the south, he moved the Islamic border to the Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

river, with Rioja, Nájera, Logroño

Logroño () is the capital of the province of La Rioja, situated in northern Spain. Traversed in its northern part by the Ebro River, Logroño has historically been a place of passage, such as the Camino de Santiago. Its borders were disputed b ...

, Calahorra, and Alfaro added to his domain.

In 1118, the city of Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

was taken by the Aragonese forces, and on 25 February 1119 the city of Tudela was taken and incorporated into Pamplona.

The 1127 Peace of Támara delimited the territorial domains of the Castilian and Aragonese realms, the latter including Pamplona. The lands of Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao. ...

, Álava

Álava ( in Spanish) or Araba (), officially Araba/Álava, is a Provinces of Spain, province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Country, heir of the ancient Basque señoríos#Lords of Álav ...

, Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa (, , ; es, Guipúzcoa ; french: Guipuscoa) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French de ...

, Belorado

Belorado is a village and municipality in Spain, belonging to the Province of Burgos, in the autonomous community of Castile-Leon. It has a population of approximately 2,100 inhabitants. It is also known for being a city in the Way of Saint J ...

, Soria

Soria () is a municipality and a Spanish city, located on the Douro river in the east of the autonomous community of Castile and León and capital of the province of Soria. Its population is 38,881 ( INE, 2017), 43.7% of the provincial populati ...

and San Esteban de Gormaz

San Esteban de Gormaz is a municipality in the province of Soria in the autonomous community of Castile-Leon, Spain. Its population is approximately 3,500. The town is located in the Wool Route and the Way of the Cid, the route of the exile of ...

went back to the Pamplonese kingdom.

Restoration and the loss of western Navarre

The status quo between Aragon and Castile stood until the 1134 death of Alfonso. Being childless, he willed his realm to the military orders, particularly theTemplars

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

. This decision was rejected by the courts (parliaments) of both Aragon and Navarre, which then chose separate kings.

García Ramírez, known as ''the Restorer'', is the first King of Navarre to use such a title. He was Lord of Monzón, a grandson of Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, El Cid

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (c. 1043 – 10 July 1099) was a Castilian knight and warlord in medieval Spain. Fighting with both Christian and Muslim armies during his lifetime, he earned the Arabic honorific ''al-sīd'', which would evolve into El C ...

, and a descendant by illegitimate line of king García Sánchez III. Sancho Garcia, known as Sancho VI "the Wise" (1150–1194), a patron of learning, as well as an accomplished statesman, fortified Navarre within and without, granted charters (fueros) to a number of towns, and was never defeated in battle. He was the first king to issue royal documents entitling him ''rex Navarrae'' or ''rex Navarrorum'', appealing to a wider power base, defined as politico-juridical by Urzainqui (a "populus"), beyond Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

and the customary ''rex Pampilonensium''. As attested in the charters of San Sebastián and Vitoria-Gasteiz (1181), the natives are called ''Navarri'', as well as in another contemporary document at least, where those living to the north of Peralta are defined as Navarrese.

''The Restorer'' and

''The Restorer'' and Sancho the Wise

Sancho Garcés VI ( eu, Antso VI.a; 21 April 1132 - 27 June 1194), called the Wise ( eu, Jakituna, es, el Sabio) was King of Navarre from 1150 until his death in 1194. He was the first monarch to officially drop the title of ''King of Pamplona'' ...

were faced with an ever-increasing intervention of Castile in Navarre. In 1170, Alfonso VIII of Castile

Alfonso VIII (11 November 11555 October 1214), called the Noble (''El Noble'') or the one of Las Navas (''el de las Navas''), was King of Castile from 1158 to his death and King of Toledo. After having suffered a great defeat with his own army a ...

and Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was intro ...

, daughter of Henry II Plantagenet, married, with the Castilian king claiming Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

as part of the dowry. It turned out a much needed pretext for the invasion of Navarre during the following years (1173–1176), with a special focus on Navarre's coastal districts, coveted by Castile in order to become a maritime power. In 1177, the dispute was submitted to arbitration by Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin kin ...

. The Navarrese made their point on a number of claims, namely "the proven will of the locals" (''fide naturalium hominum suorum exhibita''), the assassination of the King Sancho Garces IV of Navarre by the Castilians (''per violentiam fuit expulsus'', 1076), as well as law and custom, while the Castilians made their case by citing the Castilian takeover following the death of Sancho Garces IV, the dynastic links of Alfonso with Navarre, and the conquest of Toledo. Henry did not dare issue a verdict based entirely on the legal grounds as presented by both sides, instead deciding to refer them back to the boundaries held by both kingdoms at the start of their reigns in 1158, besides agreeing to a truce of seven years. It thus confirmed the permanent loss of the Bureba and Rioja areas for the Navarrese. However, soon, Castile breached the compromise, starting a renewed effort to harass Navarre both in the diplomatic and military arenas.

The rich dowry of Berengaria, daughter of Sancho VI the Wise and Blanche of Castile, made her a desirable catch for Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and Duchy of Gascony, Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Co ...

. His mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of Henry II of England, King Henry I ...

, crossed the Pyrenean passes to escort Berengaria to Sicily, eventually to wed Richard in Cyprus, on 12 May 1191. She remains the only Queen of England who never set foot in England during her reign. The reign of Sancho the Wise's successor, the last king of the male line of Sancho the Great and the kings of Pamplona, Sancho VII the Strong (''Sancho el Fuerte'') (1194–1234), was more troubled. He appropriated the revenues of churches and convents, granting them instead important privileges; in 1198 he presented to the See of Pamplona his palaces and possessions there; this gift was confirmed by Pope Innocent III on 29 January 1199.

Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ar, تلمسان, translit=Tilimsān) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran, and capital of the Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the p ...

(modern Algeria) seeking support to counter the Castilian push, by opening a second front. Pope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III ( la, Caelestinus III; c. 1106 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, ...

intervened to frustrate the alliance.

The towns of Vitoria and Treviño

Treviño (in Basque: Trebiñu) is the capital of the municipality Condado de Treviño, province of Burgos, in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. The Condado de Treviño and the geographically smaller La Puebla de Arganzón ma ...

resisted the Castilian assault but the Bishop of Pamplona was sent to inform them that no reinforcements would arrive. After nine months of siege, Vitoria surrendered, but Treviño did not, having to be conquered by force of arms. By 1200 the conquest of western Navarre was complete. Castile allowed these territories (with the exceptions of Treviño and Oñati

Oñati ( eu, Oñati, es, Oñate) is a town located in the province of Gipuzkoa, in the autonomous community of the Basque Country, in the north of Spain. It has a population of approximately 10,500 and lies in a valley in the center of the Basqu ...

, which were directly ruled from Castile) the right to keep their traditional customs and laws (''viz.'', Navarrese law), which came to be known as fueros. Alava was made a county, Biscay a lordship and Gipuzkoa just a province. In 1207, an arrangement in Guadalajara between both kings sealed a 5-year truce over the occupied territories; still Castile kept a ''fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engl ...

'' policy.

Sancho the Strong would join in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, known in Islamic history as the Battle of Al-Uqab ( ar, معركة العقاب), took place on 16 July 1212 and was an important turning point in the ''Reconquista'' and the medieval history of Spain. The Chris ...

(1212), where he added his small force to the Christian alliance that was victorious over the Caliph Muhammand An-Nasir. He suffered from a varicose ulcer in his leg that led him to retire to Tudela, where he died in 1234. His elder sister Berengaria, Queen of England, had died childless some years earlier. His deceased younger sister Blanca, countess of Champagne, had left a son, Theobald IV of Champagne. Thus the Kingdom of Navarre, though the crown was still claimed by the kings of Aragon, passed by marriage to the House of Champagne, firstly to the heirs of Blanca, who were simultaneously counts of Champagne and Brie, with the support of the Navarrese Parliament (''Cortes'').

Navarre in the Late Middle Ages

Rule by Champagne and France

Theobald I made of his court a centre where the poetry of the troubadours that had developed at the court of the counts of Champagne was welcomed and fostered; his reign was peaceful. His son, King Theobald II (1253–70), married Isabella, daughter of KingLouis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...