Kenneth Kaunda on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Dissatisfied with Harry Nkumbula's leadership of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress, he broke away and founded the

In 1949 Kaunda entered politics and became the founding member of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress. On 11 November 1953 he moved to Lusaka to take up the post of Secretary General of the Africa National Congress (ANC), under the presidency of Harry Nkumbula. The combined efforts of Kaunda and Nkumbula failed to mobilise native African peoples against the European-dominated

In 1949 Kaunda entered politics and became the founding member of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress. On 11 November 1953 he moved to Lusaka to take up the post of Secretary General of the Africa National Congress (ANC), under the presidency of Harry Nkumbula. The combined efforts of Kaunda and Nkumbula failed to mobilise native African peoples against the European-dominated

At the time of its independence, Zambia's

At the time of its independence, Zambia's

Kaunda's newly independent government inherited a country with one of the most vibrant economies in sub-Saharan Africa, largely on account of its rich mineral deposits, albeit one that was largely under the control of foreign and multinational interests.

For example, the

Kaunda's newly independent government inherited a country with one of the most vibrant economies in sub-Saharan Africa, largely on account of its rich mineral deposits, albeit one that was largely under the control of foreign and multinational interests.

For example, the

From 1964 onwards, Kaunda's government developed authoritarian characteristics. Becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition, Kaunda banned all parties except UNIP following violence during the 1968 elections. However, in early 1972, he faced a new threat in the form of

From 1964 onwards, Kaunda's government developed authoritarian characteristics. Becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition, Kaunda banned all parties except UNIP following violence during the 1968 elections. However, in early 1972, he faced a new threat in the form of

During his early presidency Kaunda was an outspoken supporter of the anti-apartheid movement and opposed white minority rule in Southern Rhodesia. Although his nationalisation of the copper mining industry in the late 1960s and the volatility of international copper prices contributed to increased economic problems, matters were aggravated by his logistical support for the black nationalist movements in Ian Smith's

During his early presidency Kaunda was an outspoken supporter of the anti-apartheid movement and opposed white minority rule in Southern Rhodesia. Although his nationalisation of the copper mining industry in the late 1960s and the volatility of international copper prices contributed to increased economic problems, matters were aggravated by his logistical support for the black nationalist movements in Ian Smith's  In the first twenty years of Kaunda's presidency, he and his advisors sought numerous times to acquire modern weapons from the United States. In a letter written to US president Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967, Kaunda inquired if the United States would provide him with long-range missile systems; all of his requests for modern weapons were refused by the United States. In 1980, Kaunda purchased sixteen MiG-21 jets from the

In the first twenty years of Kaunda's presidency, he and his advisors sought numerous times to acquire modern weapons from the United States. In a letter written to US president Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967, Kaunda inquired if the United States would provide him with long-range missile systems; all of his requests for modern weapons were refused by the United States. In 1980, Kaunda purchased sixteen MiG-21 jets from the  Meanwhile, the anti-white minority insurgency conflicts of southern Africa continued to place a huge economic burden on Zambia as white minority governments were the country's main trading partners. In response, Kaunda negotiated the TAZARA Railway (

Meanwhile, the anti-white minority insurgency conflicts of southern Africa continued to place a huge economic burden on Zambia as white minority governments were the country's main trading partners. In response, Kaunda negotiated the TAZARA Railway ( Kaunda had frequent but cordial differences with US president Ronald Reagan whom he met 1983 and British prime minister

Kaunda had frequent but cordial differences with US president Ronald Reagan whom he met 1983 and British prime minister

Kaunda married Betty Banda in 1946, with whom he had eight children. She died on 19 September 2012, aged 84, while visiting one of their daughters in

Kaunda married Betty Banda in 1946, with whom he had eight children. She died on 19 September 2012, aged 84, while visiting one of their daughters in

Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the  Supreme Companion of O. R. Tambo (South Africa)—10 December 2002

*

Supreme Companion of O. R. Tambo (South Africa)—10 December 2002

*  Commander of the

Commander of the  Honorary Member of the

Honorary Member of the

"Kaunda, Kenneth"

''

1964: President Kaunda takes power in Zambia

Kaunda on the non-aligned movementKaunda on MugabeKenneth Kaunda, the United States and Southern Africa by Andy deRoche

Faces of Africa

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaunda, Kenneth David 1924 births 2021 deaths African pan-Africanists Bemba Deaths from pneumonia in Zambia Grand Crosses of the Order of Prince Henry Heads of government who were later imprisoned Local government ministers of Zambia Members of the Legislative Council of Northern Rhodesia Members of the National Assembly of Zambia People from Chinsali District Presidents of Zambia Prime Ministers of Zambia Prisoners and detainees of Rhodesia Recipients of the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo Secretaries-General of the Non-Aligned Movement Socialist rulers United National Independence Party politicians Zambian independence activists Zambian people of Malawian descent Zambian politicians convicted of crimes Zambian Presbyterians Zambian prisoners and detainees Chinsali

Zambian African National Congress The Northern Rhodesia Congress was a political party in Zambia.

History

The Northern Rhodesia Congress party was formed in 1940, as the Northern Rhodesia Congress (NRC) or Northern Rhodesia African Congress (NRAC). Godwin Lewanika, a Barotseland ...

, later becoming the head of the socialist United National Independence Party

The United National Independence Party (UNIP) is a political party in Zambia. It governed the country from 1964 to 1991 under the socialist presidency of Kenneth Kaunda, and was the sole legal party in the country between 1973 and 1990. On 4 ...

(UNIP).

Kaunda was the first president of independent Zambia. In 1973, following tribal and inter-party violence, all political parties except UNIP were banned through an amendment of the constitution after the signing of the Choma Declaration. At the same time, Kaunda oversaw the acquisition of majority stakes in key foreign-owned companies. The 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had su ...

and a slump in export revenues put Zambia in a state of economic crisis. International pressure forced Kaunda to change the rules that had kept him in power. Multi-party elections took place in 1991, in which Frederick Chiluba, the leader of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy, ousted Kaunda.

He was briefly stripped of Zambian citizenship in 1999, but the decision was overturned the following year.

Early life

Kenneth Kaunda was born on 28 April 1924 at Lubwa Mission inChinsali

Chinsali is a town in Zambia, which is both the district headquarters of Chinsali District and provincial headquarters of Muchinga Province.

Location

It lies just off the road between Mpika and Isoka (Tanzam Highway; Zambia's Great North ...

, then part of Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesi ...

, now Zambia, and was the youngest of eight children. His father, the Reverend David Kaunda, was an ordained Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

missionary and teacher, who had been born in Nyasaland (now Malawi) and had moved to Chinsali, to work at Lubwa Mission. His mother was also a teacher and was the first African woman to teach in colonial Northern Rhodesia. They were both teachers among the Bemba

Bemba may refer to:

* Bemba language (Chibemba), a Bantu language spoken in Zambia

* Bemba people (AbaBemba), an ethnic group of central Africa

* Jean-Pierre Bemba, the former vice-President of the Democratic Republic of Congo

* A Caribbean drum, ...

ethnic group which is located in northern Zambia. His father died when Kenneth was a child. This is where Kenneth Kaunda received his education until the early 1940s. He later on followed in his parents' footsteps and became a teacher; first in Northern Rhodesia but then in the middle of the 1940s he moved to Tanganyika Territory (now part of Tanzania). He also worked in Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing colony, self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The reg ...

. He attended Munali Training Centre in Lusaka

Lusaka (; ) is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was about 3.3 millio ...

between 1941 and 1943. Early in his career, he read the writings of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

that he said: "went straight to my heart."

Kaunda was a teacher at the Upper Primary School and Boarding Master at Lubwa and then Headmaster at Lubwa from 1943 to 1945. For a time, he worked at the Salisbury and Bindura Mine. In early 1948, he became a teacher in Mufulira

Mufulira, is a town in the Copperbelt Province of Zambia. Mufulira means "Place of Abundance and Peace". The town developed around the Mufulira Copper Mine in the 1930s. The town also serves as the administrative capital of Mufulira District. ...

for the United Missions to the Copperbelt (UMCB). He was then assistant at an African Welfare Centre and Boarding Master of a Mine School in Mufulira. In this period, he was leading a Pathfinder Scout Group and was Choirmaster at a Church of Central Africa congregation. He was also Vice-Secretary of the Nchanga Branch of Congress.

Independence struggle and presidency

In 1949 Kaunda entered politics and became the founding member of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress. On 11 November 1953 he moved to Lusaka to take up the post of Secretary General of the Africa National Congress (ANC), under the presidency of Harry Nkumbula. The combined efforts of Kaunda and Nkumbula failed to mobilise native African peoples against the European-dominated

In 1949 Kaunda entered politics and became the founding member of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress. On 11 November 1953 he moved to Lusaka to take up the post of Secretary General of the Africa National Congress (ANC), under the presidency of Harry Nkumbula. The combined efforts of Kaunda and Nkumbula failed to mobilise native African peoples against the European-dominated Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation or CAF, was a colonial federation that consisted of three southern African territories: the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia and the B ...

. In 1955 Kaunda and Nkumbula were imprisoned for two months with hard labour for distributing subversive literature. The two leaders drifted apart as Nkumbula became increasingly influenced by white liberals and failing to defend indigenous Africans, Kuanda led a dissident group to Nkumbula that eventually broke with the ANC and founded his own party, the Zambian African National Congress The Northern Rhodesia Congress was a political party in Zambia.

History

The Northern Rhodesia Congress party was formed in 1940, as the Northern Rhodesia Congress (NRC) or Northern Rhodesia African Congress (NRAC). Godwin Lewanika, a Barotseland ...

(ZANC) in October 1958. ZANC was banned in March 1959 and in Kaunda was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment, which he spent first in Lusaka, then in Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

.

While Kaunda was in prison, Mainza Chona

Mainza Mathias Chona (21 January 1930 – 11 December 2001) was a Zambian politician and founder of UNIP who served as the third vice-president of Zambia from 1970 to 1973 and Prime Minister on two occasions: from 25 August 1973 to 27 May ...

and other nationalists broke away from the ANC and, in October 1959, Chona became the first president of the United National Independence Party

The United National Independence Party (UNIP) is a political party in Zambia. It governed the country from 1964 to 1991 under the socialist presidency of Kenneth Kaunda, and was the sole legal party in the country between 1973 and 1990. On 4 ...

(UNIP), the successor to ZANC. However, Chona did not see himself as the party's main founder. When Kaunda was released from prison in January 1960 he was elected president of UNIP. In 1960 he visited Martin Luther King Jr. in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

and afterwards, in July 1961, Kaunda organised a civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

campaign in Northern Province, the so-called Cha-cha-cha campaign, which consisted largely of arson and obstructing significant roads. Kaunda subsequently ran as a UNIP candidate during the 1962 elections. This resulted in a UNIP–ANC Coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

, with Kaunda as Minister of Local Government and Social Welfare. In January 1964, UNIP won the next major elections, defeating their ANC rivals and securing Kaunda's position as prime minister. On 24 October 1964 he became the first president of an independent Zambia, appointing Reuben Kamanga as his vice-president.

Educational policies

At the time of its independence, Zambia's

At the time of its independence, Zambia's modernisation

Modernization theory is used to explain the process of modernization within societies. The "classical" theories of modernization of the 1950s and 1960s drew on sociological analyses of Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim and a partial reading of Max Weber, ...

process was far from complete. The nation's educational system was one of the most poorly developed in all of Britain's former colonies, and it had just a hundred university graduates and no more than 6,000 indigenous inhabitants with two years or more of secondary education. Because of this, Zambia had to invest heavily in education at all levels. Kaunda instituted a policy where all children, irrespective of their parents' ability to pay, were given free exercise books, pens, and pencils. The parents' main responsibility was to buy uniforms, pay a token "school fee" and ensure that the children attended school. This approach meant that the best pupils were promoted to achieve their best results, all the way from primary school to university level. Not every child could go to secondary school, for example, but those who did were well educated.

The University of Zambia

The University of Zambia (UNZA) is a public university located in Lusaka, Zambia. It is Zambia's largest and oldest learning institution. The university was established in 1965 and officially opened to the public on 12 July 1966. The language of ...

was opened in Lusaka in 1966, after Zambians all over the country had been encouraged to donate whatever they could afford towards its construction. Kaunda was appointed Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

and officiated at the first graduation ceremony in 1969. The main campus was situated on the Great East Road, while the medical campus was located at Ridgeway near the University Teaching Hospital

The University Teaching Hospital (UTH) formerly Lusaka hospital is the biggest public tertiary hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. It is the largest hospital with 1,655 beds. It is a teaching hospital and, as such, is used to train local medical students, ...

. In 1979 another campus was established at the Zambia Institute of Technology in Kitwe

Kitwe is the third largest city in terms of infrastructure development (after Lusaka and Ndola) and second largest city in terms of size and population (after Lusaka) in Zambia. With a population of 517,543 (''2010 census provisional'') Kitwe is ...

. In 1988 the Kitwe campus was upgraded and renamed the Copperbelt University, offering business studies, industrial studies and environmental studies.

Other tertiary-level institutions established during Kaunda's era were vocationally focused and fell under the aegis of the Department of Technical Education and Vocational Training. They include the Evelyn Hone College The Evelyn Hone College of Applied Arts and Commerce'is the largest of the Technical Education and Vocational Training (TEVET) institutions under the Ministry of Higher Education in Zambi It is a quasi-government college, third-largest in the countr ...

and the Natural Resources Development College (both in Lusaka), the Northern Technical College at Ndola, the Livingstone Trades Training Institute in Livingstone, and teacher-training colleges.

Economic policies

Kaunda's newly independent government inherited a country with one of the most vibrant economies in sub-Saharan Africa, largely on account of its rich mineral deposits, albeit one that was largely under the control of foreign and multinational interests.

For example, the

Kaunda's newly independent government inherited a country with one of the most vibrant economies in sub-Saharan Africa, largely on account of its rich mineral deposits, albeit one that was largely under the control of foreign and multinational interests.

For example, the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

(BSAC, founded by Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Bri ...

) still retained commercial assets and mineral rights that it had acquired from a concession signed with the Litunga of Bulozi in 1890. Only by threatening to expropriate it on the eve of independence did Kaunda manage to get favourable concessions from the BSAC.

His ineptness at economic management blighted his country's development after independence. Despite having some of the finest farming land in Africa, Kaunda adopted the same socialist agricultural policies as Tanzania, with disastrous results.

Deciding on a planned economy, Zambia instituted a programme of national development, under the direction of the National Commission for Development Planning, which instituted a "Transitional Development Plan" and the "First National Development Plan". The two operations brought major investment in the infrastructure and manufacturing sectors. In April 1968, Kaunda initiated the Mulungushi Reforms, which sought to bring Zambia's foreign-owned corporations under national control under the Industrial Development Corporation. Over the subsequent years, a number of mining corporations were nationalised, although the country's banks, such as Barclays

Barclays () is a British multinational universal bank, headquartered in London, England. Barclays operates as two divisions, Barclays UK and Barclays International, supported by a service company, Barclays Execution Services.

Barclays traces ...

and Standard Chartered

Standard Chartered plc is a multinational bank with operations in consumer, corporate and institutional banking, and treasury services. Despite being headquartered in the United Kingdom, it does not conduct retail banking in the UK, and around 9 ...

, remained foreign-owned. The Zambian economy suffered a setback from 1973, when rising oil prices and falling copper prices combined to reduce the state's income from the nationalised mines. The country fell into debt with the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glo ...

(IMF), and the Third National Development Plan had to be abandoned as crisis management replaced long-term planning. His weak attempts at economic reforms in the 1980s hastened Zambia's decline. A number of negotiations with the IMF followed, and by 1990 Kaunda was forced into partial privatisation of the state-owned corporations. The country's economic woes ultimately contributed to his fall from power.

One-party state and "African socialism"

In 1964, shortly before independence, violence broke out between supporters of theLumpa Church The Lumpa Church, an independent Christian church, was established in 1953 by "Alice" Lenshina Mulenga in the village of Kasama, Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent countr ...

, led by Alice Lenshina

Alice Lenshina (1920–1978) was a Zambian woman, prisoner of conscience and self-appointed " prophetess" who is noted for her part in the " Lumpa Uprising", which claimed 700 lives.

Lenshina founded and led the Lumpa Church, a religious sect t ...

. Kaunda temporarily banned the church and ordered Lumpa's arrest.

From 1964 onwards, Kaunda's government developed authoritarian characteristics. Becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition, Kaunda banned all parties except UNIP following violence during the 1968 elections. However, in early 1972, he faced a new threat in the form of

From 1964 onwards, Kaunda's government developed authoritarian characteristics. Becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition, Kaunda banned all parties except UNIP following violence during the 1968 elections. However, in early 1972, he faced a new threat in the form of Simon Kapwepwe

Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe (April 12, 1922 – January 26, 1980) was a Zambian politician, anti-colonialist and author who served as the second vice-president of Zambia from 1967 to 1970.

Early life

Simon Kapwepwe was born on 12 April 1922 in the ...

's decision to leave UNIP and found a rival party, the United Progressive Party, which Kaunda immediately attempted to suppress. Next, he appointed the Chona Commission, which was set up under the chairmanship of Mainza Chona in February 1972. Chona's task was to make recommendations for a new Zambian constitution which would effectively reduce the nation to a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other partie ...

. The commission's terms of reference did not permit it to discuss the possible faults of Kaunda's decision, but instead to concentrate on the practical details of the move to a one-party state. Finally, Kaunda neutralised Nkumbula by getting him to join UNIP and accept the Choma Declaration on 27 June 1973. The new constitution was formally promulgated on 25 August of that year. At the first elections under the new system held that December, Kaunda was the sole candidate.

With all opposition having been eliminated, Kaunda allowed the creation of a personality cult. He developed a left nationalist-socialist ideology, called Zambian Humanism. This was based on a combination of mid-20th-century ideas of central planning/state control and what he considered basic African values: mutual aid, trust, and loyalty to the community. Similar forms of African socialism

African socialism or Afrosocialism is a belief in sharing economic resources in a traditional African way, as distinct from classical socialism. Many African politicians of the 1950s and 1960s professed their support for African socialism, althou ...

were introduced inter alia in Ghana by Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An ...

("Consciencism") and Tanzania by Julius Nyerere (" Ujamaa"). To elaborate on his ideology, Kaunda published several books: ''Humanism in Zambia and a Guide to its Implementation, Parts 1, 2 and 3''. Other publications on Zambian Humanism are: ''Fundamentals of Zambian Humanism'', by Timothy Kandeke; ''Zambian Humanism, religion and social morality'', by Rev. Fr. Cleve Dillion-Malone, S.J., and ''Zambian Humanism: some major spiritual and economic challenges'', by Justin B. Zulu. ''Kaunda on Violence'' (US title, ''The Riddle of Violence'') was published in 1980.

As president of UNIP, and under the country's one-party state system, Kaunda was the only candidate for president of the republic in the general elections of 1978

Events January

* January 1 – Air India Flight 855, a Boeing 747 passenger jet, crashes off the coast of Bombay, killing 213.

* January 5 – Bülent Ecevit, of CHP, forms the new government of Turkey (42nd government).

* January 6 ...

, 1983, and 1988, each time with official results showing over 80 per cent of voters approving his candidacy. Parliamentary elections were also controlled by Kaunda. In the 1978 UNIP elections, Kaunda amended the party's constitution to bring in rules that invalidated the challengers' nominations: Kapwepwe was told he could not stand because only people who had been members for five years could be nominated to the presidency (he had only rejoined UNIP three years before); Nkumbula and a third contender, businessman Robert Chiluwe, were outmanoeuvred by introducing a new rule that said each candidate needed the signatures of 200 delegates from ''each'' province to back their candidacy.

Foreign policy

During his early presidency Kaunda was an outspoken supporter of the anti-apartheid movement and opposed white minority rule in Southern Rhodesia. Although his nationalisation of the copper mining industry in the late 1960s and the volatility of international copper prices contributed to increased economic problems, matters were aggravated by his logistical support for the black nationalist movements in Ian Smith's

During his early presidency Kaunda was an outspoken supporter of the anti-apartheid movement and opposed white minority rule in Southern Rhodesia. Although his nationalisation of the copper mining industry in the late 1960s and the volatility of international copper prices contributed to increased economic problems, matters were aggravated by his logistical support for the black nationalist movements in Ian Smith's Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

, South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

, Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, and Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

. Kaunda's administration later attempted to serve the role of a mediator between the entrenched white minority and colonial governments and the various guerrilla movements which were aimed at overthrowing these respective administrations. Beginning in the early 1970s, he began permitting the most prominent guerrilla organisations, such as the Rhodesian ZANU and the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

, to use Zambia as a base for their operations. Former ANC president Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and revolutionary who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography

Higher education

Oliv ...

even spent a significant proportion of his 30-year exile living and working in Zambia. Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

, leader of ZAPU, also erected military encampments there, as did SWAPO

The South West Africa People's Organisation (, SWAPO; af, Suidwes-Afrikaanse Volks Organisasie, SWAVO; german: Südwestafrikanische Volksorganisation, SWAVO), officially known as the SWAPO Party of Namibia, is a political party and former ind ...

and its military wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia. In the first twenty years of Kaunda's presidency, he and his advisors sought numerous times to acquire modern weapons from the United States. In a letter written to US president Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967, Kaunda inquired if the United States would provide him with long-range missile systems; all of his requests for modern weapons were refused by the United States. In 1980, Kaunda purchased sixteen MiG-21 jets from the

In the first twenty years of Kaunda's presidency, he and his advisors sought numerous times to acquire modern weapons from the United States. In a letter written to US president Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967, Kaunda inquired if the United States would provide him with long-range missile systems; all of his requests for modern weapons were refused by the United States. In 1980, Kaunda purchased sixteen MiG-21 jets from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, which ultimately provoked a reaction from the United States. Kaunda responded to the United States, stating that after numerous failed attempts to purchase weapons, buying from the Soviets was justified in his duty to protect his citizens and Zambian national security. His attempted purchase of American weapons may have been a political tactic to use fear to establish his one-party rule over Zambia.

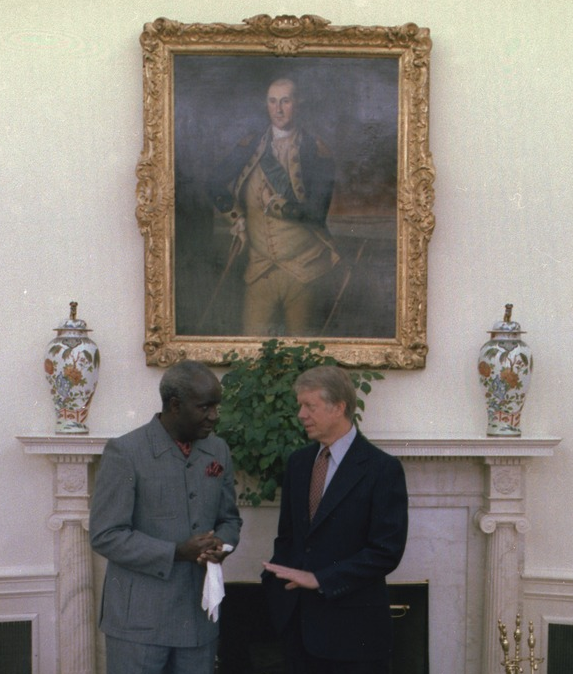

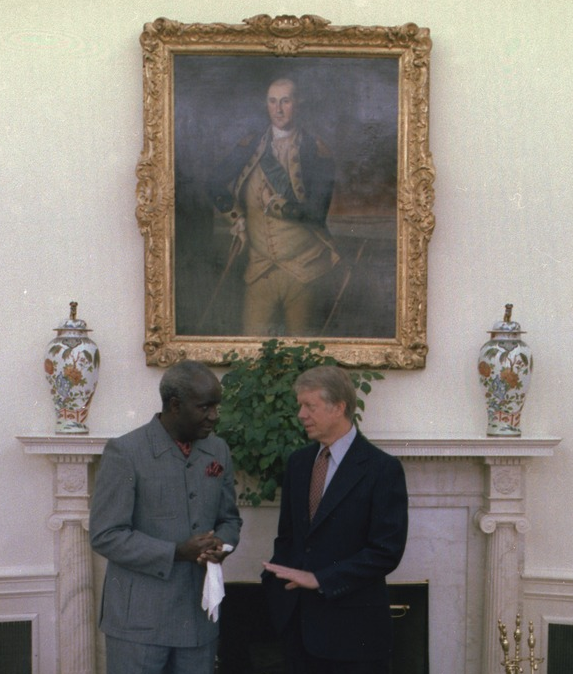

From April 1975, when he visited US president Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

in Washington, D.C., and delivered a powerful speech calling for the United States to play a more active and constructive role in southern Africa. Until approximately 1984, Kaunda was arguably the key African leader involved in international diplomacy regarding the conflicts in Angola, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and Namibia. He hosted Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

's 1976 trip to Zambia, got along very well with Jimmy Carter, and worked closely with President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

's assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Chester Crocker

Chester Arthur Crocker (born October 29, 1941) is an American diplomat and scholar who served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs from June 9, 1981, to April 21, 1989, in the Reagan administration. Crocker, architect of the U.S. ...

. While there were disagreements between Kaunda and US leaders (such as when Zambia purchased Soviet MiG fighters or when he accused two American diplomats of being spies), Kaunda generally enjoyed a positive relationship with the United States during these years.

On 26 August 1975, Kaunda acted as mediator along with the Prime Minister of South Africa

The prime minister of South Africa ( af, Eerste Minister van Suid-Afrika) was the head of government in South Africa between 1910 and 1984.

History of the office

The position of Prime Minister was established in 1910, when the Union of Sout ...

, B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

, at the Victoria Falls Conference to discuss possibilities for an internal settlement in Southern Rhodesia with Ian Smith and the black nationalists. After the Lancaster House Agreement, Kaunda attempted to seek similar majority rule in South West Africa. He met with P. W. Botha in Botswana in 1982 to debate this proposal, but apparently failed to make a serious impression.

Meanwhile, the anti-white minority insurgency conflicts of southern Africa continued to place a huge economic burden on Zambia as white minority governments were the country's main trading partners. In response, Kaunda negotiated the TAZARA Railway (

Meanwhile, the anti-white minority insurgency conflicts of southern Africa continued to place a huge economic burden on Zambia as white minority governments were the country's main trading partners. In response, Kaunda negotiated the TAZARA Railway (Tanzam

The Tazara Railway, also called the Uhuru Railway or the Tanzam Railway, is a railway in East Africa linking the port of Dar es Salaam in east Tanzania with the town of Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia's Central Province. The single-track railway is ...

) linking Kapiri Mposhi in the Zambian Copperbelt with Tanzania's port of Dar-es-Salaam on the Indian Ocean. Completed in 1975, this was the only route for bulk trade which did not have to transit white-dominated territories. This precarious situation lasted more than 20 years, until the abolition of apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

in South Africa.

For much of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, Kaunda was a strong supporter of the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

. He hosted a NAM summit in Lusaka in 1970 and served as the movement's chairman from 1970 to 1973. He maintained a close friendship with Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

's long-time leader Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

; he was remembered by many Yugoslav officials for weeping openly over Tito's casket in 1980. He also visited and welcomed Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

's president, Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( , ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician and dictator. He was the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and the second and last Communist leader of Romania. He ...

, in the 1970s. In 1986, the University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia, awarded him an honorary doctorate. Kaunda had frequent but cordial differences with US president Ronald Reagan whom he met 1983 and British prime minister

Kaunda had frequent but cordial differences with US president Ronald Reagan whom he met 1983 and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

mainly over what he saw as a blind eye being turned towards South African apartheid. He always maintained warm relations with the People's Republic of China who had provided assistance on many projects in Zambia, including the Tazara Railway.

Prior to the first Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

, Kaunda cultivated a friendship with Iraqi president Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

, whom he claimed to have attempted to dissuade from invading Kuwait. A street in Lusaka was named in Saddam's honour, although the name was later changed when both leaders had left power.

In August 1989, Farzad Bazoft

Farzad Bazoft ( fa, فرزاد بازفت; 22 May 1958 – 15 March 1990) was an Iranian journalist who settled in the United Kingdom in the mid-1970s. He worked as a freelance reporter for ''The Observer''. He was arrested by Iraqi authoritie ...

was detained in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

for alleged espionage. He was accompanied by a British nurse, Daphne Parish, who was also arrested. Bazoft was an Iranian-born freelance journalist attempting to expose Saddam's mass murder of Iraqi Kurds

Iraqi Kurds ( ar, العراقيين الكرد, ku, کوردەکانی عێراق) are people born in or residing in Iraq who are of Kurdish origin. The Kurds are the largest ethnic minority in Iraq, comprising between 15% and 20% of the count ...

. Bazoft was later tried, convicted, and executed, but Kaunda managed to negotiate for his female companion's release.

Kaunda served as chairman of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) from 1970 to 1971 and again from 1987 to 1988.

Fall from power

Matters quickly came to a head in 1990. In July, amid three days of rioting in the capital, Kaunda announced a referendum on whether to legalise other parties would be held that October. However, he argued for maintaining UNIP's monopoly, claiming that a multiparty system would lead to chaos. The announcement almost came too late; hours later, a disgruntled officer went on the radio to announce Kaunda had been overthrown. The coup attempt was broken three to four hours later, but it was clear Kaunda and the UNIP were reeling. Kaunda tried to mollify the opposition by moving the referendum to August 1991; the opposition claimed the original date did not allow enough time for voter registration. While expressing willingness to have the Zambian people vote on a multiparty system, Kaunda maintained that only a one-party state could prevent tribalism and violence from engulfing the country. By September, however, opposition demands forced Kaunda to reverse course. He cancelled the referendum, and instead recommended constitutional amendments that would dismantle UNIP's monopoly on power. He also announced a snap general election for the following year, two years before it was due. He signed the necessary amendments into law in December. At these elections, the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), helmed by trade union leader Frederick Chiluba, swept UNIP from power in a landslide. In the presidential election, Kaunda was roundly defeated, taking only 24 per cent of the vote to Chiluba's 75 per cent. UNIP was cut down to only 25 seats in theNational Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

. One of the issues in the campaign was a plan by Kaunda to turn over one-quarter of the nation's land to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (born Mahesh Prasad Varma, 12 January 1918

, an Indian guru who promised that he would use it for a network of utopian agricultural enclaves that proponents said would create "Heaven on Earth". Kaunda was forced in a television interview to deny practising Transcendental Meditation

Transcendental Meditation (TM) is a form of silent mantra meditation advocated by the Transcendental Meditation movement. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi created the technique in India in the mid-1950s. Advocates of TM claim that the technique promotes ...

. When Kaunda handed power to Chiluba on 2 November 1991, he became the second mainland African head of state to allow free multiparty elections and to relinquish power peacefully after he had lost. The first, Mathieu Kérékou of Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

, had done so in March of that year.

Post-presidency

After leaving office, Kaunda clashed frequently with Chiluba's government and the MMD. Chiluba later attempted to deport Kaunda on the grounds that he was a Malawian. The MMD-dominated government under the leadership of Chiluba had the constitution amended, barring citizens with foreign parentage from standing for the presidency, to prevent Kaunda from contesting the next elections in 1996, in which he planned to participate. After the 1997 coup attempt, onBoxing Day

Boxing Day is a holiday celebrated after Christmas Day, occurring on the second day of Christmastide (26 December). Though it originated as a holiday to give gifts to the poor, today Boxing Day is primarily known as a shopping holiday. It ...

in 1997 he was arrested by paramilitary policemen. However, many officials in the region appealed against this; on New Year's Eve of the same year, he was placed under house arrest until his court date. In 1999 Kaunda was declared stateless by the Ndola High Court in a judgment delivered by Justice Chalendo Sakala. Kaunda however successfully challenged this decision in the Supreme Court of Zambia, which declared him to be a Zambian citizen in the '' Lewanika and Others vs. Chiluba'' ruling.

On 4 June 1998, Kaunda announced that he was resigning as United National Independence Party leader and retiring from politics. After retiring in 2000, he was involved in various charitable organisations. His most notable contribution was his zeal in the fight against the spread of HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ...

. One of Kaunda's children was claimed by the pandemic in the 1980s. From 2002 to 2004, he was an ''African President-in-Residence'' at the African Presidential Archives and Research Center at Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with its original cam ...

.

In September 2019, Kaunda said that it was regrettable that the late president Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the ...

was maligned and subjected to mudslinging by some sections of the world, who were against his crusade of bringing social justice and equity to Zimbabwe.

Personal life and death

Kaunda married Betty Banda in 1946, with whom he had eight children. She died on 19 September 2012, aged 84, while visiting one of their daughters in

Kaunda married Betty Banda in 1946, with whom he had eight children. She died on 19 September 2012, aged 84, while visiting one of their daughters in Harare

Harare (; formerly Salisbury ) is the capital and most populous city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of 940 km2 (371 mi2) and a population of 2.12 million in the 2012 census and an estimated 3.12 million in its metropolitan ...

, Zimbabwe. Since Kenneth Kaunda was known to wear a safari suit ( safari jacket paired with trousers) constantly, the safari suit is still commonly referred to as a "Kaunda suit" throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

He also wrote music about the independence he hoped to achieve, although only one song has been known to many Zambians ("Tiyende pamodzi ndi mtima umo" literally meaning "Let's walk together with one heart").

On 14 June 2021, Kaunda was admitted to Maina Soko Military Hospital in Lusaka to be treated for an undisclosed medical condition. The Zambian government said medics were doing everything they could to make him recover, though it was not clear what his health condition was. On 15 June 2021, it was revealed that he was being treated for pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

, which according to his doctor, had been a recurring problem in his health. On 17 June 2021 it was confirmed that he died at the age of 97 after a short illness at Maina Soko Military Hospital. He was survived by 30 grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren.

President Edgar Lungu announced on his Facebook page that Zambia will observe 21 days of national mourning

A national day of mourning is a day or days marked by mourning and memorial activities observed among the majority of a country's populace. They are designated by the national government. Such days include those marking the death or funeral of ...

. On 21 June, Vice-President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

Inonge Wina announced that Kaunda's remains would be taken on a funeral procession around the country's provinces, with church services in each provincial capital, prior to a state funeral at National Heroes Stadium

Heroes National Stadium is a multi-purpose stadium in Lusaka, Lusaka Province, Zambia. It is currently used mostly for football matches and hosts the home matches of the Zambia national football team. The stadium holds 60,000 spectators. It open ...

in Lusaka on 2 July and interment at the Presidential Burial Site on 7 July.

Several other nations also announced periods of state mourning. Zimbabwe declared fourteen days of mourning; South Africa declared ten days of mourning; Botswana, Malawi, Namibia and Tanzania all declared seven days of mourning; Mozambique declared six days of mourning; South Sudan declared three days of mourning; Cuba declared one day of mourning. President of Singapore

The president of Singapore is the head of state of the Republic of Singapore. The role of the president is to safeguard the reserves and the integrity of the public service. The presidency is largely ceremonial, with the Cabinet led by the prime ...

Halimah Yacob offered her condolences to the politicians and people of Zambia for Kaunda's death.

Awards and honours

Foreign honours * Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Henry

The Order of Prince Henry ( pt, Ordem do Infante Dom Henrique) is a Portuguese order of knighthood created on 2 June 1960, to commemorate the quincentenary of the death of the Portuguese prince Henry the Navigator, one of the main initiators of ...

(Portugal)—28 May 1975

*  Supreme Companion of O. R. Tambo (South Africa)—10 December 2002

*

Supreme Companion of O. R. Tambo (South Africa)—10 December 2002

*  Commander of the

Commander of the Most Courteous Order of Lesotho

The Most Courteous Order of Lesotho is the highest national order in the honours system of Lesotho. It was founded by King Moshoeshoe II of Lesotho in 1972, in three grades.

Insignia

The original ribbon for the order was predominantly dark blue, ...

(Lesotho)—4 October 2007

*  Honorary Member of the

Honorary Member of the Order of Jamaica

The Order of Jamaica is the fifth of the six orders in the Jamaican honours system. The Order was established in 1969, and it is considered the equivalent of a knighthood in the British honours system.

Membership in the Order can be conferred upon ...

Awards

* On 21 May 1963, he received an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from Fordham University

Fordham University () is a private Jesuit research university in New York City. Established in 1841 and named after the Fordham neighborhood of the Bronx in which its original campus is located, Fordham is the oldest Catholic and Jesuit un ...

.

* On 19 October 2007 Kaunda was the recipient of the 2007 Ubuntu Award.

Publications

* * * * * * * *See also

* Michael Sata * Harry Nkumbula *Simon Kapwepwe

Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe (April 12, 1922 – January 26, 1980) was a Zambian politician, anti-colonialist and author who served as the second vice-president of Zambia from 1967 to 1970.

Early life

Simon Kapwepwe was born on 12 April 1922 in the ...

*History of Christianity in Zambia

Christianity has been very much at the heart of religion in Zambia since the European colonial explorations into the interior of Africa in the mid 19th century. The area features heavily in the accounts of David Livingstone's journeys in Central ...

References

Bibliography

* DeRoche, Andy. ''Kenneth Kaunda, the United States and Southern Africa'' (London: Bloomsbury, 2016)"Kaunda, Kenneth"

''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

''. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

* Hall, Richard. ''The High Price of Principles: Kaunda and the White South'' (1969)

* Ipenburg, At. ''All Good Men: The Development of Lubwa Mission, Chinsali, Zambia, 1905–1967'' (1992)

* Macpherson, Fergus. ''Kenneth Kaunda: The Times and the Man'' (1974)

* Mulford, David C. ''Zambia: The Politics of Independence, 1957–1964'' (1967)

External links

1964: President Kaunda takes power in Zambia

Kaunda on the non-aligned movement

Faces of Africa

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaunda, Kenneth David 1924 births 2021 deaths African pan-Africanists Bemba Deaths from pneumonia in Zambia Grand Crosses of the Order of Prince Henry Heads of government who were later imprisoned Local government ministers of Zambia Members of the Legislative Council of Northern Rhodesia Members of the National Assembly of Zambia People from Chinsali District Presidents of Zambia Prime Ministers of Zambia Prisoners and detainees of Rhodesia Recipients of the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo Secretaries-General of the Non-Aligned Movement Socialist rulers United National Independence Party politicians Zambian independence activists Zambian people of Malawian descent Zambian politicians convicted of crimes Zambian Presbyterians Zambian prisoners and detainees Chinsali