Kenneth Clark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television, presenting a succession of programmes on the arts during the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in the ''

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television, presenting a succession of programmes on the arts during the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in the ''

Clark was born at 32

Clark was born at 32

"Clark, Kenneth Mackenzie, Baron Clark (1903–1983)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, retrieved 14 June 2017 The Clarks were a Scottish family who had grown rich in the textile trade. Clark's great-great-grandfather invented the cotton spool, and the Clark Thread Company of Paisley had grown into a substantial business. Kenneth Clark senior worked briefly as a director of the firm and retired in his mid-twenties as a member of the "idle rich", as Clark junior later put it: although "many people were richer, there can have been few who were idler".Clark (1974), p. 1 The Clarks maintained country homes at Sudbourne Hall, Suffolk, and at Clark was educated at Wixenford School and, from 1917 to 1922,

Clark was educated at Wixenford School and, from 1917 to 1922,

"Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation, review"

, ''The Telegraph'', 19 May 2014 Clark attracted the attention of Charles F. Bell (1871–1966), Keeper of the Fine Art Department of the

In 1929, as a result of his work with Berenson, Clark was asked to catalogue the extensive collection of

In 1929, as a result of his work with Berenson, Clark was asked to catalogue the extensive collection of "Clark,_Sir_Kenneth_MacKenzie"_[sic

/nowiki>.html" ;"title="ic">"Clark, Sir Kenneth MacKenzie" [sic

/nowiki>">ic">"Clark, Sir Kenneth MacKenzie" [sic

/nowiki> Dictionary of Art Historians, retrieved 18 June 2017 The exhibition covered Italian art "from Cimabue to Giovanni Segantini, Segantini" – from the mid-thirteenth to the late-nineteenth century. It was greeted with public and critical acclaim, and raised Clark's profile, but he came to regret the propaganda value derived from the exhibition by the Italian dictator

At about the same time as accepting MacDonald's offer of the directorship, Clark had declined one from

At about the same time as accepting MacDonald's offer of the directorship, Clark had declined one from

, ''The Burlington Magazine'', Vol. 115, No. 844 (July 1973), pp. 415–416 He had rooms re-hung and frames improved; by 1935 he had achieved the installation of a laboratory and introduced electric lighting, which made evening opening possible for the first time. A programme of cleaning was begun, despite sporadic sniping from those opposed in principle to cleaning old pictures; experimentally, the glass was removed from some pictures. In several years he had the gallery opened two hours earlier than usual on the day of the

"Clark, Kenneth"

Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 18 June 2017 Another 1935 publication by Clark offended some in the avant-garde: an essay, published in '' The Listener'', "The Future of Painting", in which he rebuked surrealists on the one hand and abstract artists on the other for claiming to represent the future of art. He judged both as too elitist and too specialised – "the end of a period of self-consciousness, inbreeding and exhaustion". He maintained that good art must be accessible to everyone and must be rooted in the observable world. During the 1930s Clark was in demand as a lecturer, and he frequently used his research for his talks as the basis of his books. In 1936 he gave the Ryerson Lectures at ''The Burlington Magazine'', looking back at Clark's time at the gallery, singled out among the works acquired under his leadership the seven panels forming

''The Burlington Magazine'', looking back at Clark's time at the gallery, singled out among the works acquired under his leadership the seven panels forming

, National Gallery, retrieved 18 June 2017 He saw them in 1937 in the possession of a dealer in Vienna, and against the united advice of his professional staff he persuaded the trustees to buy them. He believed them to be by

, The National Gallery, retrieved 18 June 2017 A disused slate mine near With an empty gallery to preside over, Clark contemplated volunteering for the

With an empty gallery to preside over, Clark contemplated volunteering for the

In July 1946 Clark was appointed Slade Professor of Fine Art at

In July 1946 Clark was appointed Slade Professor of Fine Art at

. Many of those opposed to the new broadcaster feared vulgarisation on the lines of American television, and although Clark’s appointment reassured some, others thought his acceptance of the post a betrayal of artistic and intellectual standards.

Clark was no stranger to broadcasting. He had appeared on air frequently from 1936, when he gave a radio talk on an exhibition of Chinese Art at

, BBC Genome, retrieved 18 June 2017 During the war he appeared regularly on BBC radio's ''

Clark's first series for ATV, ''Is Art Necessary?'', began in 1958. Both he and television were finding their way, and programmes in the series ranged from the stiff and studio-bound to a film in which Clark and Henry Moore toured the British Museum at night, flashing their torches at the exhibits. When the series came to an end in 1959, Clark and the production team reviewed and refined their techniques for the next series, ''Five Revolutionary Painters'', which attracted a considerable audience.Stourton, pp. 284–285 The

Clark's first series for ATV, ''Is Art Necessary?'', began in 1958. Both he and television were finding their way, and programmes in the series ranged from the stiff and studio-bound to a film in which Clark and Henry Moore toured the British Museum at night, flashing their torches at the exhibits. When the series came to an end in 1959, Clark and the production team reviewed and refined their techniques for the next series, ''Five Revolutionary Painters'', which attracted a considerable audience.Stourton, pp. 284–285 The

"Kenneth Clark by James Stourton: review"

, ''The Guardian'', 1 October 2016 and he described himself on screen as a hero-worshipper and a stick-in-the-mud.Clark, 1969, pp. 346–347 He commented that his outlook was "nothing striking, nothing original, nothing that could not have been written by an ordinary harmless bourgeois of the later nineteenth century": The broadcaster Huw Wheldon believed that ''Civilisation'' was "a truly great series, a major work ... the first magnum opus attempted and realised in terms of TV." There was a widespread view among critics, including some unsympathetic to Clark's selections, that the filming set new standards. ''Civilisation'' attracted unprecedented viewing figures for a high art series: 2.5 million viewers in Britain and 5 million in the US. Clark's accompanying book has never been out of print, and the BBC continued to sell thousands of copies of the DVD set of ''Civilisation'' every year. In 2016, ''The New Yorker'' echoed the words of

The broadcaster Huw Wheldon believed that ''Civilisation'' was "a truly great series, a major work ... the first magnum opus attempted and realised in terms of TV." There was a widespread view among critics, including some unsympathetic to Clark's selections, that the filming set new standards. ''Civilisation'' attracted unprecedented viewing figures for a high art series: 2.5 million viewers in Britain and 5 million in the US. Clark's accompanying book has never been out of print, and the BBC continued to sell thousands of copies of the DVD set of ''Civilisation'' every year. In 2016, ''The New Yorker'' echoed the words of

"The Seductive Enthusiasm of Kenneth Clark’s ''Civilisation''"

, ''The New Yorker'', 21 December 2016 The British Film Institute notes how ''Civilisation'' changed the shape of cultural television, setting the standard for later documentary series, from

During the war the Clarks lived at Capo Di Monte, a cottage in

During the war the Clarks lived at Capo Di Monte, a cottage in

''Who Was Who'', online edition, Oxford University Press, 2014, retrieved 14 June 2017 Clark was elected a member or honorary member of the Conseil Artistique des Musées Nationaux of France; the

, The Tate, retrieved 27 June 2917 The BBC called him "arguably the most influential figure in 20th century British art". Clark knew that his broadly traditional view of art would be anathema to the

"Kenneth Clark: arrogant snob or saviour of art?"

, ''The Guardian'', 16 May 2014

The Sir Kenneth Mackenzie Clark Collection at the Victoria University Library at the University of Toronto

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Clark, Kenneth 1903 births 1983 deaths 20th-century English historians Alumni of Trinity College, Oxford Chancellors of the University of York Converts to Roman Catholicism Directors of the National Gallery, London English art critics English art historians English curators English people of Scottish descent English Roman Catholics English television presenters Fellows of the British Academy Jacob's Award winners Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Life peers Life peers created by Elizabeth II Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour People educated at Winchester College People educated at Wixenford School Recipients of the Grand Decoration with Sash for Services to the Republic of Austria Rembrandt scholars Slade Professors of Fine Art (University of Oxford) Surveyors of the Queen's Pictures Writers from London

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television, presenting a succession of programmes on the arts during the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in the ''

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television, presenting a succession of programmes on the arts during the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in the ''Civilisation

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Civ ...

'' series in 1969.

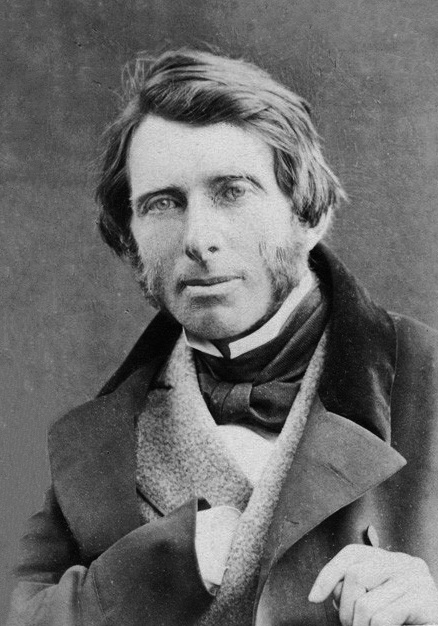

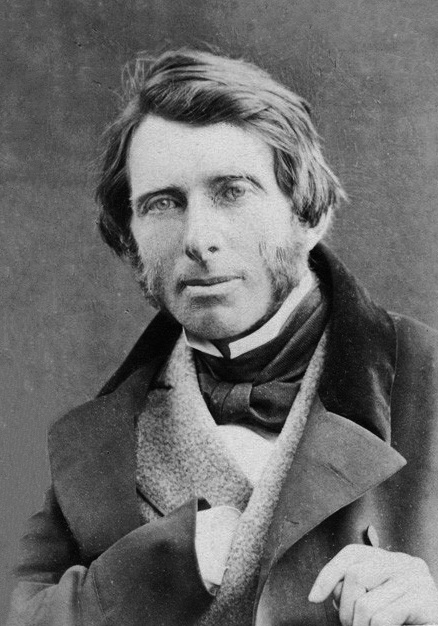

The son of rich parents, Clark was introduced to the arts at an early age. Among his early influences were the writings of John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

, which instilled in him the belief that everyone should have access to great art. After coming under the influence of the connoisseur and dealer Bernard Berenson

Bernard Berenson (June 26, 1865 – October 6, 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. His book ''The Drawings of the Florentine Painters'' was an international success. His wife Mary is thought to have had a large ...

, Clark was appointed director of the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University o ...

in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

aged twenty-seven, and three years later he was put in charge of Britain's National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

. His twelve years there saw the gallery transformed to make it accessible and inviting to a wider public. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, when the collection was moved from London for safe keeping, Clark made the building available for a series of daily concerts which proved a celebrated morale booster during the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

.

After the war, and three years as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Clark surprised many by accepting the chairmanship of the UK's first commercial television network. Once the service had been successfully launched he agreed to write and present programmes about the arts. These established him as a household name in Britain, and he was asked to create the first colour series about the arts, ''Civilisation'', first broadcast in 1969 in Britain and in many other countries soon afterwards.

Among many honours, Clark was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

at the unusually young age of thirty-five, and three decades later was made a life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. In modern times, life peerages, always created at the rank of baron, are created under the Life Peerages ...

shortly before the first transmission of ''Civilisation''. Three decades after his death, Clark was celebrated in an exhibition at Tate Britain

Tate Britain, known from 1897 to 1932 as the National Gallery of British Art and from 1932 to 2000 as the Tate Gallery, is an art museum on Millbank in the City of Westminster in London, England. It is part of the Tate network of galleries in ...

in London, prompting a reappraisal of his career by a new generation of critics and historians. Opinions varied about his aesthetic judgment, particularly in attributing paintings to old masters, but his skill as a writer and his enthusiasm for popularising the arts were widely recognised. Both the BBC and the Tate described him in retrospect as one of the most influential figures in British art of the twentieth century.Life and career

Early years

Clark was born at 32

Clark was born at 32 Grosvenor Square

Grosvenor Square is a large garden square in the Mayfair district of London. It is the centrepiece of the Mayfair property of the Duke of Westminster, and takes its name from the duke's surname "Grosvenor". It was developed for fashionable ...

, London, the only child of Kenneth Mackenzie Clark (1868–1932) and his wife, (Margaret) Alice, daughter of James McArthur of Manchester.Piper, David"Clark, Kenneth Mackenzie, Baron Clark (1903–1983)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, retrieved 14 June 2017 The Clarks were a Scottish family who had grown rich in the textile trade. Clark's great-great-grandfather invented the cotton spool, and the Clark Thread Company of Paisley had grown into a substantial business. Kenneth Clark senior worked briefly as a director of the firm and retired in his mid-twenties as a member of the "idle rich", as Clark junior later put it: although "many people were richer, there can have been few who were idler".Clark (1974), p. 1 The Clarks maintained country homes at Sudbourne Hall, Suffolk, and at

Ardnamurchan

Ardnamurchan (, gd, Àird nam Murchan: headland of the great seas) is a peninsula in the ward management area of Lochaber, Highland, Scotland, noted for being very unspoiled and undisturbed. Its remoteness is accentuated by the main access ...

, Argyll, and wintered on the French Riviera. Kenneth senior was a sportsman, a gambler, an eccentric and a heavy drinker. Clark had little in common with his father, though he always remained fond of him. Alice Clark was shy and distant, but her son received affection from a devoted nanny. An only child not especially close to his parents, the young Clark had a boyhood that was often solitary, but he was generally happy. He later recalled that he used to take long walks, talking to himself, a habit he believed stood him in good stead as a broadcaster: "Television is a form of soliloquy".Coleman, Terry. "Lord Clark", ''The Guardian'', 26 November 1977, p. 9 On a modest scale Clark senior collected pictures, and the young Kenneth was allowed to rearrange the collection. He developed a competent talent for drawing, for which he later won several prizes as a schoolboy."Obituary: Lord Clark", ''The Times'', 23 May 1983, p. 16 When he was seven he was taken to an exhibition of Japanese art in London, which was a formative influence on his artistic tastes; he recalled, "dumb with delight, I felt that I had entered a new world".

Clark was educated at Wixenford School and, from 1917 to 1922,

Clark was educated at Wixenford School and, from 1917 to 1922, Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

. The latter was known for its intellectual rigour and – to Clark's dismay – enthusiasm for sports, but it also encouraged its pupils to develop interests in the arts. The headmaster, Montague Rendall, was a devotee of Italian painting and sculpture, and inspired Clark, among many others, to appreciate the works of Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto ( , ) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic/ Proto-Renaissance period. G ...

, Botticelli

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi ( – May 17, 1510), known as Sandro Botticelli (, ), was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli's posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century, when he was rediscovered ...

, Bellini and their compatriots. The school library contained the collected writings of John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

, which Clark read avidly, and which influenced him for the rest of his life, not only in their artistic judgments but in their progressive political and social beliefs.

From Winchester, Clark won a scholarship to Trinity College, Oxford

(That which you wish to be secret, tell to nobody)

, named_for = The Holy Trinity

, established =

, sister_college = Churchill College, Cambridge

, president = Dame Hilary Boulding

, location = Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3BH

, coordinates ...

, where he studied modern history. He graduated in 1925 with a second-class honours degree. In the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Sir David Piper comments that Clark had been expected to gain a first-class degree, but had not applied himself single-mindedly to his historical studies: "his interests had already turned conclusively to the study of art".

While at Oxford, Clark was greatly impressed by the lectures of Roger Fry, the influential art critic who staged the first Post-Impressionism

Post-Impressionism (also spelled Postimpressionism) was a predominantly French art movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905, from the last Impressionist exhibition to the birth of Fauvism. Post-Impressionism emerged as a reaction ...

exhibitions in Britain. Under Fry's influence he developed an understanding of modern French painting, particularly the work of Cézanne.Dorment, Richard"Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation, review"

, ''The Telegraph'', 19 May 2014 Clark attracted the attention of Charles F. Bell (1871–1966), Keeper of the Fine Art Department of the

Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University o ...

. Bell became a mentor to him and suggested that for his B Litt thesis Clark should write about the Gothic revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

in architecture. At that time it was a deeply unfashionable subject; no serious study had been published since the nineteenth century. Although Clark's main area of study was the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, his admiration for Ruskin, the most prominent defender of the neo-Gothic style, drew him to the topic. He did not complete the thesis, but later turned his researches into his first full-length book, ''The Gothic Revival'' (1928). In 1925, Bell introduced Clark to Bernard Berenson

Bernard Berenson (June 26, 1865 – October 6, 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. His book ''The Drawings of the Florentine Painters'' was an international success. His wife Mary is thought to have had a large ...

, an influential scholar of the Italian Renaissance and consultant to major museums and collectors. Berenson was working on a revision of his book ''Drawings of the Florentine Painters'', and invited Clark to help. The project took two years, overlapping with Clark's studies at Oxford.

Early career

In 1929, as a result of his work with Berenson, Clark was asked to catalogue the extensive collection of

In 1929, as a result of his work with Berenson, Clark was asked to catalogue the extensive collection of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

drawings at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

. That year he was the joint organiser of an exhibition of Italian painting which opened at the Royal Academy on 1 January 1930. He and his co-organiser Lord Balniel

Robert Alexander Lindsay, 29th Earl of Crawford and 12th Earl of Balcarres, (born 5 March 1927), styled Lord Balniel between 1940 and 1975, is a Scottish hereditary peer and Conservative politician who was a Member of Parliament from 1955 to ...

secured masterpieces never seen before outside Italy, many of them from private collections._/nowiki>.html" ;"title="ic">

/nowiki>">ic">

/nowiki> Dictionary of Art Historians, retrieved 18 June 2017

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

who had been instrumental in making so many sought-after paintings available. Several senior figures in the British art world disapproved of the exhibition; Bell was among them, but nevertheless he continued to regard Clark as his favoured successor at the Ashmolean.

Clark was not convinced that his future lay in administration; he enjoyed writing, and would have preferred to be a scholar rather than a museum director. Nonetheless, when Bell retired in 1931 Clark agreed to succeed him at the Ashmolean. Over the next two years Clark oversaw the building of an extension to the museum to provide a better space for his department. The development was made possible by an anonymous benefactor, subsequently revealed as Clark himself. A later curator of the museum wrote that Clark would be remembered for his time there, "when, with his characteristic mixture of arrogance and energy, he transformed both the collections and their display."

National Gallery

In 1933 the director of theNational Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

in London, Sir Augustus Daniel, was aged sixty-seven, and due to retire at the end of the year. His assistant director, W. G. Constable, who had been in line to succeed him, had moved to the new Courtauld Institute of Art

The Courtauld Institute of Art (), commonly referred to as The Courtauld, is a self-governing college of the University of London specialising in the study of the history of art and conservation. It is among the most prestigious specialist coll ...

as its director in 1932. The historian Peter Stansky

Peter David Lyman Stansky (born January 18, 1932) is an American historian specializing in modern British history

The British Isles have witnessed intermittent periods of competition and cooperation between the people that occupy the ...

writes that behind the scenes the National Gallery "was in considerable turmoil; the staff and the trustees were in a state of continual warfare with each other." The chairman of the trustees, Lord Lee, convinced the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

, that Clark would be the best appointment, acceptable to the professional staff and the trustees, and able to restore harmony. When he received MacDonald's offer of the post, Clark was not enthusiastic. He thought himself too young, aged 30, and once again felt torn between a scholarly and an administrative career. He accepted the directorship, although, as he wrote to Berenson, "in between being the manager of a large department store I shall have to be a professional entertainer to the landed and official classes". At about the same time as accepting MacDonald's offer of the directorship, Clark had declined one from

At about the same time as accepting MacDonald's offer of the directorship, Clark had declined one from King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

's officials to succeed C. H. Collins Baker as Surveyor of the King's Pictures

The office of the Surveyor of the King's/Queen's Pictures, in the Royal Collection Department of the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, is responsible for the care and maintenance of the royal collection of pictures owned by ...

. He felt that he could not do justice to the post in tandem with his new duties at the gallery. The king, determined to succeed where his staff had failed, went with Queen Mary to the National Gallery and persuaded Clark to change his mind. The appointment was announced in ''The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'' is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices are ...

'' in July 1934; Clark held the post for the next ten years.

Clark believed in making fine art accessible to everyone, and while at the National Gallery he devised many initiatives with this aim in mind. In an editorial, ''The Burlington Magazine

''The Burlington Magazine'' is a monthly publication that covers the fine and decorative arts of all periods. Established in 1903, it is the longest running art journal in the English language. It has been published by a charitable organisation si ...

'' said, "Clark put all his insight and imagination into making the National Gallery a more sympathetic place in which the visitor could enjoy a great collection of European paintings"."Kenneth Clark at 70", ''The Burlington Magazine'', Vol. 115, No. 844 (July 1973), pp. 415–416 He had rooms re-hung and frames improved; by 1935 he had achieved the installation of a laboratory and introduced electric lighting, which made evening opening possible for the first time. A programme of cleaning was begun, despite sporadic sniping from those opposed in principle to cleaning old pictures; experimentally, the glass was removed from some pictures. In several years he had the gallery opened two hours earlier than usual on the day of the

FA Cup Final

The FA Cup Final, commonly referred to in England as just the Cup Final, is the last match in the Football Association Challenge Cup. It has regularly been one of the most attended domestic football events in the world, with an official atten ...

, for the benefit of people coming to London for the match.

Clark wrote and lectured during the decade. The annotated catalogue of the royal collection of Leonardo da Vinci's drawings, on which he had begun work in 1929, was published in 1935, to highly favourable reviews; eighty years later Oxford Art Online

Oxford Art Online is an Oxford University Press online gateway into art research, which was launched in 2008. It provides access to several online art reference works, including Grove Art Online (originally published in 1996 in a print version, ''T ...

called it "a work of firm scholarship, the conclusions of which have stood the test of time".Cast, David"Clark, Kenneth"

Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 18 June 2017 Another 1935 publication by Clark offended some in the avant-garde: an essay, published in '' The Listener'', "The Future of Painting", in which he rebuked surrealists on the one hand and abstract artists on the other for claiming to represent the future of art. He judged both as too elitist and too specialised – "the end of a period of self-consciousness, inbreeding and exhaustion". He maintained that good art must be accessible to everyone and must be rooted in the observable world. During the 1930s Clark was in demand as a lecturer, and he frequently used his research for his talks as the basis of his books. In 1936 he gave the Ryerson Lectures at

Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

; from these came his study of Leonardo, published three years later; it too, attracted much praise, at the time and subsequently.

''The Burlington Magazine'', looking back at Clark's time at the gallery, singled out among the works acquired under his leadership the seven panels forming

''The Burlington Magazine'', looking back at Clark's time at the gallery, singled out among the works acquired under his leadership the seven panels forming Sassetta

''For the village near Livorno, see Sassetta, Tuscany''

Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo, known as il Sassetta (ca.1392–1450 or 1451) was an Tuscan painter of the Renaissance, and a significant figure of the Sienese School.Judy Metro, ''Italia ...

's San Sepolcro Altarpiece from the fifteenth century, four works by Giovanni di Paolo from the same period, Niccolò dell'Abate's ''The Death of Eurydice'' from the sixteenth century and Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres ( , ; 29 August 1780 – 14 January 1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. Ingres was profoundly influenced by past artistic traditions and aspired to become the guardian of academic orthodoxy against the a ...

' '' Madame Moitessier'' from the nineteenth. Other important acquisitions, listed by Piper, were Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (; ; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish artist and diplomat from the Duchy of Brabant in the Southern Netherlands (modern-day Belgium). He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque traditio ...

's ''Watering Place'', Constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

's ''Hadleigh Castle'', Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally cons ...

's ''Saskia as Flora'', and Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (, , ; June 1594 – 19 November 1665) was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. Most of his works were on religious and mythological subjects painted for ...

's '' The Adoration of the Golden Calf''.

One of Clark's least successful acts as director was buying four early-sixteenth century paintings now known as '' Scenes from Tebaldeo's Eclogues''."Scenes from Tebaldeo's Eclogues", National Gallery, retrieved 18 June 2017 He saw them in 1937 in the possession of a dealer in Vienna, and against the united advice of his professional staff he persuaded the trustees to buy them. He believed them to be by

Giorgione

Giorgione (, , ; born Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco; 1477–78 or 1473–74 – 17 September 1510) was an Italian painter of the Venetian school during the High Renaissance, who died in his thirties. He is known for the elusive poetic quali ...

, whose work was inadequately represented in the gallery at the time. The trustees authorised the expenditure of £14,000 of public funds and the paintings went on display in the gallery with considerable fanfare. His staff did not accept the attribution to Giorgione, and within a year scholarly research established the paintings as the work of Andrea Previtali

Andrea Previtali (c. 1480 –1528) was an Italian painter of the Renaissance period, active mainly in Bergamo. He was also called Andrea Cordelliaghi.

Biography

Previtali was a pupil of the painter Giovanni Bellini. In Bergamo, he painted ...

, one of Giorgione's minor contemporaries. The British press protested at the waste of taxpayers' money, Clark's reputation suffered a considerable blow, and his relations with his professional team, already uneasy, were further strained.

Wartime

The approach of war with Germany in 1939 obliged Clark and his colleagues to consider how to protect the National Gallery's collection from bombing raids. It was agreed that all the works of art must be moved out of central London, where they were acutely vulnerable. One suggestion was to send them to Canada for safekeeping, but by this time the war had started and Clark was worried about the possibility of submarine attacks on the ships taking the collection across the Atlantic; he was not displeased when the prime minister,Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, vetoed the idea: "Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island.""The Gallery in wartime", The National Gallery, retrieved 18 June 2017 A disused slate mine near

Blaenau Ffestiniog

Blaenau Ffestiniog is a town in Gwynedd, Wales. Once a slate mining centre in historic Merionethshire, it now relies much on tourists, drawn for instance to the Ffestiniog Railway and Llechwedd Slate Caverns. It reached a population of 12,000 ...

in north Wales was chosen as the store. To protect the paintings special storage compartments were constructed, and from careful monitoring of the collection discoveries were made about control of temperature and humidity that benefited its care and display when back in London after the war.

With an empty gallery to preside over, Clark contemplated volunteering for the

With an empty gallery to preside over, Clark contemplated volunteering for the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a c ...

, but was recruited, at Lord Lee's instigation, into the newly-formed Ministry of Information, where he was put in charge of the film division, and was later promoted to be controller of home publicity. He set up the War Artists' Advisory Committee The War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC), was a British government agency established within the Ministry of Information at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 and headed by Sir Kenneth Clark. Its aim was to compile a comprehensive artist ...

, and persuaded the government to employ official war artists in considerable numbers. There were up to two hundred engaged under Clark's initiative. Those designated "official war artists" included Edward Ardizzone

Edward Jeffrey Irving Ardizzone, (16 October 1900 – 8 November 1979), who sometimes signed his work "DIZ", was an English painter, print-maker and war artist, and the author and illustrator of books, many of them for children. For ''Tim All ...

, Paul and John Nash, Mervyn Peake

Mervyn Laurence Peake (9 July 1911 – 17 November 1968) was an English writer, artist, poet, and illustrator. He is best known for what are usually referred to as the '' Gormenghast'' books. The four works were part of what Peake conceived ...

, John Piper and Graham Sutherland. Artists employed on short-term contracts included Jacob Epstein

Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 21 August 1959) was an American-British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a British subject in 1911.

He often produce ...

, Laura Knight

Dame Laura Knight ( Johnson; 4 August 1877 – 7 July 1970) was an English artist who worked in oils, watercolours, etching, engraving and drypoint. Knight was a painter in the figurative, realist tradition, who embraced English Impressi ...

, L. S. Lowry, Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi-abstract art, abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Mo ...

and Stanley Spencer

Sir Stanley Spencer, CBE RA (30 June 1891 – 14 December 1959) was an English painter. Shortly after leaving the Slade School of Art, Spencer became well known for his paintings depicting Biblical scenes occurring as if in Cookham, the sma ...

.

Although the pictures were in storage, Clark kept the National Gallery open to the public during the war, hosting a celebrated series of lunchtime and early evening concerts. They were the inspiration of the pianist Myra Hess, whose idea Clark greeted with delight, as a suitable way for the building to be "used again for its true purposes, the enjoyment of beauty." There was no advance booking, and audience members were free to eat their sandwiches and walk in or out during breaks in the performance. The concerts were an immediate and enormous success. ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainzer ...

'' commented, "Countless Londoners and visitors to London, civilian and service alike, came to look on the concerts as a haven of sanity in a distraught world." 1,698 concerts were given to an aggregate audience of more than 750,000 people. Clark instituted an additional public attraction of a monthly featured picture brought from storage and exhibited along with explanatory material. The institution of a "picture of the month" was retained after the war, and, at 2022, continues to the present day.

In 1945, after overseeing the return of the collections to the National Gallery, Clark resigned as director, intending to devote himself to writing. During the war years he had published little. For the gallery he wrote a slim volume about Constable's '' The Hay Wain'' (1944); from a lecture he gave in 1944 he published a short treatise on Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer; he epitomised the nature of those identified now as polymaths. H ...

's ''On Painting'' (1944). The following year he contributed an introduction and notes to a volume on Florentine paintings in a series of art books published by Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel ...

. The three publications totalled fewer than eighty pages between them.

Postwar

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

for a three-year term. The post required him to give eight public lectures each year on the "History, Theory, and Practice of the Fine Arts". The first holder of the professorship had been Ruskin; Clark took as his first subject Ruskin's tenure of the post. James Stourton, Clark's authorised biographer, judges the appointment to be the most rewarding his subject ever held, and notes how, during this period, Clark established himself as Britain's most sought-after lecturer, and wrote two of his finest books, ''Landscape into Art'' (1947) and ''Piero della Francesca'' (1951).Stourton, pp. 224–225 By this time Clark no longer hankered after a career in pure scholarship, but saw his role as sharing his knowledge and experience with the wide public.

Clark served on numerous official committees during this period, and helped to stage a ground-breaking exhibition in Paris of works by his friend and protégé Henry Moore. He was more in sympathy with modern painting and sculpture than with much of modern architecture. He admired Giles Gilbert Scott

Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (9 November 1880 – 8 February 1960) was a British architect known for his work on the New Bodleian Library, Cambridge University Library, Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, Battersea Power Station, Liverpool Cathedral, and ...

, Maxwell Fry

Edwin Maxwell Fry, CBE, RA, FRIBA, FRTPI, known as Maxwell Fry (2 August 1899 – 3 September 1987), was an English modernist architect, writer and painter.

Originally trained in the neo-classical style of architecture, Fry grew to favour th ...

, Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key role in the architectural movements o ...

, Alvar Aalto

Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto (; 3 February 1898 – 11 May 1976) was a Finnish architect and designer. His work includes architecture, furniture, textiles and glassware, as well as sculptures and paintings. He never regarded himself as an artist, s ...

and others, but found many contemporary buildings mediocre. Clark had been among the first to conclude that private patronage could no longer support the arts; during the war he had been a prominent member of the state-funded Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. When it was reconstituted as the Arts Council of Great Britain

The Arts Council of Great Britain was a non-departmental public body dedicated to the promotion of the fine arts in Great Britain. It was divided in 1994 to form the Arts Council of England (now Arts Council England), the Scottish Arts Council ( ...

in 1945 he was invited to serve as a member of its executive committee, and as chairman of the council's arts panel.

In 1953 Clark became the Arts Council's chairman. He held the post until 1960, but it was a frustrating experience for him; he found himself chiefly a figurehead. Moreover, he was concerned that the way the council went about funding the arts was in danger of damaging the individualism of the artists whom it supported.

Broadcasting: administrator, 1954–1957

The year after becoming chairman of the Arts Council, Clark surprised many and shocked some by accepting the chairmanship of the new Independent Television Authority (ITA). It had been set up by the Conservative government to introduce ITV, commercial television, funded by advertising, as a rival to theBritish Broadcasting Corporation #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Burlington House

Burlington House is a building on Piccadilly in Mayfair, London. It was originally a private Neo-Palladian mansion owned by the Earls of Burlington and was expanded in the mid-19th century after being purchased by the British government. To ...

; the following year he made his television debut, presenting Florentine paintings from the National Gallery."Kenneth Clark", BBC Genome, retrieved 18 June 2017 During the war he appeared regularly on BBC radio's ''

The Brains Trust

''The Brains Trust'' was an informational BBC radio and later television programme popular in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 1950s, on which a panel of experts tried to answer questions sent in by the audience.

History

The series was ...

''. While presiding over the new ITA he generally kept off the air, and concentrated on keeping the new network going during its difficult early years. By the end of his three-year term as chairman, Clark was hailed as a success, but privately considered that there were too few high-quality programmes on the network. Lew Grade

Lew Grade, Baron Grade, (born Lev Winogradsky; 25 December 1906 – 13 December 1998) was a British media proprietor and impresario. Originally a dancer, and later a talent agent, Grade's interest in television production began in 19 ...

, who as chairman of Associated Television

Associated Television was the original name of the British broadcaster ATV, part of the Independent Television (ITV) network. It provided a service to London at weekends from 1955 to 1968, to the Midlands on weekdays from 1956 to 1968, and ...

(ATV) held one of the ITV franchises, felt strongly that Clark should make arts programmes of his own, and as soon as Clark stood down as chairman in 1957, he accepted Grade's invitation. Stourton comments, "this was the true beginning of arguably his most successful career – as a presenter of the arts on television".

Broadcasting: ITV, 1957–1966

Clark's first series for ATV, ''Is Art Necessary?'', began in 1958. Both he and television were finding their way, and programmes in the series ranged from the stiff and studio-bound to a film in which Clark and Henry Moore toured the British Museum at night, flashing their torches at the exhibits. When the series came to an end in 1959, Clark and the production team reviewed and refined their techniques for the next series, ''Five Revolutionary Painters'', which attracted a considerable audience.Stourton, pp. 284–285 The

Clark's first series for ATV, ''Is Art Necessary?'', began in 1958. Both he and television were finding their way, and programmes in the series ranged from the stiff and studio-bound to a film in which Clark and Henry Moore toured the British Museum at night, flashing their torches at the exhibits. When the series came to an end in 1959, Clark and the production team reviewed and refined their techniques for the next series, ''Five Revolutionary Painters'', which attracted a considerable audience.Stourton, pp. 284–285 The British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

observes:

By the time in 1960 when he presented a programme about Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

, Clark had further honed his presentational skills and came across as relaxed as well as authoritative. Two series on architecture followed, culminating in a programme called ''The Royal Palaces of Britain'' in 1966, a joint venture by ITV and the BBC, described as "by far the most important heritage programme shown on British television to date". ''The Guardian'' described Clark as "the ideal man for the job – scholarly, courtly and gently ironical". ''The Royal Palaces'', unlike its predecessors, was shot on 35mm colour film, but transmission was still in black and white, at which Clark chafed. The BBC was by this time planning to broadcast in colour, and his renewed contact with the corporation for this film paved the way for his eventual return to its schedules.Stourton, pp. 288–289 In the interim he remained with ITV for a 1966 series, ''Three Faces of France'', featuring the works of Courbet, Manet

A wireless ad hoc network (WANET) or mobile ad hoc network (MANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network. The network is ad hoc because it does not rely on a pre-existing infrastructure, such as routers in wired networks or access points ...

and Degas

Edgar Degas (, ; born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, ; 19 July 183427 September 1917) was a French Impressionist artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings.

Degas also produced bronze sculptures, prints and drawings. Degas is espec ...

.

''Civilisation'', 1966–1969

David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural histo ...

, the controller of the BBC's new second television channel, BBC2

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It covers a wide range of subject matter, with a remit "to broadcast programmes of depth and substance" in contrast to the more mainstream a ...

, was in charge of introducing colour broadcasting to the UK. He conceived the idea of a series about great paintings as the standard-bearer for colour television, and had no doubt that Clark would be much the best presenter for it. Clark was attracted by the suggestion, but at first declined to commit himself. He later recalled that what convinced him that he should take part was Attenborough’s use of the word "civilisation" to sum up what the series would be about.

The series consisted of thirteen programmes, each fifty minutes long, written and presented by Clark, covering western European civilisation from the end of the Dark Ages to the early twentieth century. As the civilisation under consideration excluded Graeco-Roman, Asian and other historically important cultures, a title was chosen that disclaimed comprehensiveness: ''Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clark''. Although it focused chiefly on the visual arts and architecture, there were substantial sections about drama, literature, philosophy and socio-political movements. Clark wanted to include more about law and philosophy, but "I could not think of any way of making them visually interesting."Hearn, p. 16

After initial mutual antipathy, Clark and his principal director, Michael Gill, established a congenial working relationship. They and their production team spent three years from 1966 filming in a hundred and seventeen locations in thirteen countries. The filming was to the highest technical standards of the day, and quickly went over budget; it cost £500,000 by the time it was complete. Attenborough rejigged his broadcasting schedules to spread the cost.

There were complaints, then and later, that by focusing on a traditional choice of the great artists over the centuries – all men – Clark had neglected women, and presented "a saga of noble names and sublime objects with little regard for the shaping forces of economics or practical politics". His ''modus operandi'' was dubbed "the great man approach", Beard, Mary"Kenneth Clark by James Stourton: review"

, ''The Guardian'', 1 October 2016 and he described himself on screen as a hero-worshipper and a stick-in-the-mud.Clark, 1969, pp. 346–347 He commented that his outlook was "nothing striking, nothing original, nothing that could not have been written by an ordinary harmless bourgeois of the later nineteenth century":

The broadcaster Huw Wheldon believed that ''Civilisation'' was "a truly great series, a major work ... the first magnum opus attempted and realised in terms of TV." There was a widespread view among critics, including some unsympathetic to Clark's selections, that the filming set new standards. ''Civilisation'' attracted unprecedented viewing figures for a high art series: 2.5 million viewers in Britain and 5 million in the US. Clark's accompanying book has never been out of print, and the BBC continued to sell thousands of copies of the DVD set of ''Civilisation'' every year. In 2016, ''The New Yorker'' echoed the words of

The broadcaster Huw Wheldon believed that ''Civilisation'' was "a truly great series, a major work ... the first magnum opus attempted and realised in terms of TV." There was a widespread view among critics, including some unsympathetic to Clark's selections, that the filming set new standards. ''Civilisation'' attracted unprecedented viewing figures for a high art series: 2.5 million viewers in Britain and 5 million in the US. Clark's accompanying book has never been out of print, and the BBC continued to sell thousands of copies of the DVD set of ''Civilisation'' every year. In 2016, ''The New Yorker'' echoed the words of John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture ...

, describing Clark as "the man who made the best telly you’ve ever seen".Meis, Morgan"The Seductive Enthusiasm of Kenneth Clark’s ''Civilisation''"

, ''The New Yorker'', 21 December 2016 The British Film Institute notes how ''Civilisation'' changed the shape of cultural television, setting the standard for later documentary series, from

Alastair Cooke

Alistair Cooke (born Alfred Cooke; 20 November 1908 – 30 March 2004) was a British-American writer whose work as a journalist, television personality and radio broadcaster was done primarily in the United States.America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

'' (1972) and Jacob Bronowski

Jacob Bronowski (18 January 1908 – 22 August 1974) was a Polish-British mathematician and philosopher. He was known to friends and professional colleagues alike by the nickname Bruno. He is best known for developing a humanistic approach to sc ...

's '' The Ascent of Man'' (1973) to the present day.

Later years: 1970–1983

Clark made a series of six programmes for ITV. They were collectively titled ''Pioneers of Modern Painting'', directed by his son Colin. They were screened in November and December 1971, with a programme on each ofManet

A wireless ad hoc network (WANET) or mobile ad hoc network (MANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network. The network is ad hoc because it does not rely on a pre-existing infrastructure, such as routers in wired networks or access points ...

, Cezanne, Monet, Seurat, Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, and Munch. Although they were shown on commercial television, there were no advertising breaks during each programme. With the aid of a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) is an independent federal agency of the U.S. government, established by thNational Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965(), dedicated to supporting research, education, preserv ...

, the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art, and its attached Sculpture Garden, is a national art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of ch ...

in Washington DC acquired copies of the series and distributed them to colleges and universities throughout the US.

Five years later, Clark returned to the BBC, presenting five programmes about Rembrandt. The series, directed by Colin Clark, considered various aspects of the painter's work, from his self-portraits to his biblical scenes. The National Gallery observes about this series, "These art history lectures are an authoritative study of Rembrandt and feature examples of his work from over fifty museums".

Clark was chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the University of York

The University of York (abbreviated as or ''York'' for post-nominals) is a collegiate research university, located in the city of York, England. Established in 1963, the university has expanded to more than thirty departments and centres, co ...

from 1967 to 1978 and a trustee of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. During his last ten years he wrote thirteen books. As well as some drawn from his researches for his lectures and television series, there were two volumes of memoirs, ''Another Part of the Wood'' (1974) and ''The Other Half'' (1977). He was known throughout his life for his impenetrable façade and enigmatic character, which were reflected in the two autobiographical books: Piper describes them as "elegantly and subtly polished, at times very moving, often very funny utsomewhat distanced, as if about someone else."

In his last years Clark suffered from arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis is the thickening, hardening, and loss of elasticity of the walls of arteries. This process gradually restricts the blood flow to one's organs and tissues and can lead to severe health risks brought on by atherosclerosis, which ...

. He died at the age of seventy-nine in a nursing home in Hythe

Hythe, from Anglo-Saxon ''hȳð'', may refer to a landing-place, port or haven, either as an element in a toponym, such as Rotherhithe in London, or to:

Places Australia

* Hythe, Tasmania

Canada

*Hythe, Alberta, a village in Canada

England

* ...

, Kent, after a fall.Stourton, p. 398

Family and personal life

In 1927 Clark married a fellow student, Elizabeth Winifred Martin, known as "Jane" (1902–1976), the daughter of Robert Macgregor Martin, a Dublin businessman, and his wife, Emily Winifred Dickson. The couple had three children:Alan

Alan may refer to:

People

*Alan (surname), an English and Turkish surname

* Alan (given name), an English given name

**List of people with given name Alan

''Following are people commonly referred to solely by "Alan" or by a homonymous name.''

* ...

, in 1928, and twins, Colette (known as Celly, pronounced "Kelly") and Colin, in 1932.

Away from his official duties, Clark enjoyed what he described as "the Great Clark Boom" in the 1930s. He and his wife lived and entertained in considerable style in a large house in Portland Place

Portland Place is a street in the Marylebone district of central London. Named after the Third Duke of Portland, the unusually wide street is home to BBC Broadcasting House, the Chinese and Polish embassies, the Royal Institute of British ...

. In Piper's words, "the Clarks in joint alliance became stars of London high society, intelligentsia, and fashion, from Mayfair to Windsor".

The Clarks' marriage was devoted but stormy. Clark was a womaniser, and although Jane had love affairs, notably with the composer William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

, she took some of her husband's extramarital relationships badly. She suffered severe mood swings and later alcoholism and a stroke. Clark remained firmly supportive of his wife during her decline. The Clarks' relations with their three children were sometimes difficult, particularly with their elder son, Alan. He was regarded by his father as a fascist by conviction though also as the ablest member of the Clark family "parents included"; he became a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

member of parliament and junior minister, and a celebrated diarist. The younger son, Colin, became a film-maker, who among other work directed his father in television series in the 1970s. The twin daughter, Colette, became an official and board member of the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal ...

; she outlived her parents and brothers, and was the key source for James Stourton's authorised biography of her father, published in 2016.

Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the London Borough o ...

, before moving to the much larger Upper Terrace House nearby. They moved in 1953 when Clark bought the Norman castle of Saltwood in Kent, which became the family home. In his later years he passed the castle to his elder son, moving to a purpose-built house in the grounds.

Jane Clark died in 1976. Her death was expected, but left Clark devastated. Several of his female friends hoped that he would marry them. His closest female friend, across thirty years, was the photographer Janet Woods, wife of the engraver Reynolds Stone

Alan Reynolds Stone, CBE, RDI (13 March 1909 – 23 June 1979) was an English wood engraver, engraver, designer, typographer and painter.

Biography

Stone was born on 13 March 1909 at Eton College, where both his grandfather, E. D. Stone, and fa ...

; in common with Clark's daughter and sons, she was dismayed when he announced his intention to marry Nolwen de Janzé-Rice (1924–1989), daughter of Frederic and Alice de Janzé

Alice de Janzé (née Silverthorne; 28 September 1899 – 30 September 1941),Reed, Frank Fremont (1982). ''History of the Silverthorn Family, Vol. 4'', p. 550. Chicago: DuBane's Print Shop. Her birth and death date can also be found at http://www ...

.Stourton, pp. 388–390 The family felt that Clark was acting precipitately in marrying someone he had not known well for very long, but the wedding took place in November 1977. Clark and his second wife remained together until his death.

Beliefs

Clark's parents were Liberal in outlook, and Ruskin's social and political views influenced the young Clark. Mary Beard wrote in a ''Guardian

Guardian usually refers to:

* Legal guardian, a person with the authority and duty to care for the interests of another

* ''The Guardian'', a British daily newspaper

(The) Guardian(s) may also refer to:

Places

* Guardian, West Virginia, Unit ...

'' article that Clark was a lifelong Labour voter. His religious outlook was unconventional, but he believed in the divine, rejected atheism, and found the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

too secular in its outlook. Shortly before his death he was received into the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

Honours and legacy

Awards and memorials

State and other honours received by Clark includedKnight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

in 1938; Fellow of the British Academy

Fellowship of the British Academy (FBA) is an award granted by the British Academy to leading academics for their distinction in the humanities and social sciences. The categories are:

# Fellows – scholars resident in the United Kingdom

# ...

, 1949, Companion of Honour

The Order of the Companions of Honour is an order of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded on 4 June 1917 by King George V as a reward for outstanding achievements. Founded on the same date as the Order of the British Empire, it is sometimes ...

, 1959; life peerage

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. In modern times, life peerages, always created at the rank of baron, are created under the Life Peerages A ...

, 1969; Companion of Literature

The title ''‘Companion of Literature’'' is the highest award bestowed by the Royal Society of Literature. The title was inaugurated in 1961, and is held by up to twelve living writers at any one time.

Recipients

Those who have been awarded t ...

, 1974; and the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by ...

1976. Overseas honours included Commander of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleo ...

, France; Commander of the Order of the Lion of Finland

The Order of the Lion of Finland ( fi, Suomen Leijonan ritarikunta; sv, Finlands Lejons orden) is one of three official orders in Finland, along with the Order of the Cross of Liberty and the Order of the White Rose of Finland. The President ...

and the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by ...

, Austria."Clark, Baron"''Who Was Who'', online edition, Oxford University Press, 2014, retrieved 14 June 2017 Clark was elected a member or honorary member of the Conseil Artistique des Musées Nationaux of France; the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

; the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to s ...

. the Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy ( sv, Svenska Akademien), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is bes ...

; the Spanish Academy; the Florentine Academy

The Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze ("academy of fine arts of Florence") is an instructional art academy in Florence, in Tuscany, in central Italy.

It was founded by Cosimo I de' Medici in 1563, under the influence of Giorgio Vasari. ...

; the Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

; and the Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institut ...

. He was awarded honorary degrees by the universities of Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire ...

, Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

, York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, and in the US Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region i ...

and Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model ...

universities. He was an honorary fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

and the Royal College of Art

The Royal College of Art (RCA) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom, with campuses in South Kensington, Battersea and White City. It is the only entirely postgraduate art and design university in the United Kingdom. It ...

. Other honours and awards included Serena Medal of the British Academy

The British Academy is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the same year. It is now a fellowship of more than 1,000 leading scholars s ...

(for Italian Studies); the Gold Medal and Citation of Honour of New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

; and the US National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art, and its attached Sculpture Garden, is a national art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of ch ...

Medal.

Clark's old school, Winchester College, holds an annual art history speaking competition for the Kenneth Clark Prize. The winner of the competition is awarded a golden Lord Clark Medal sculpted by a fellow Old Wykehamist, Anthony Smith. At the Courtauld Institute

The Courtauld Institute of Art (), commonly referred to as The Courtauld, is a self-governing college of the University of London specialising in the study of the history of art and conservation. It is among the most prestigious specialist c ...

in London, the lecture theatre is named in Clark's honour.

Reputation

In 2014The Tate