Kelvin-Planck statement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The second law of thermodynamics is a

The

The

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an engine and its surroundings.

Recognizing the significance of

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an engine and its surroundings.

Recognizing the significance of

Content selected by Frank L. Lambert

In 1865, the German physicist

In 1865, the German physicist

physical law

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow) ...

based on universal experience concerning heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

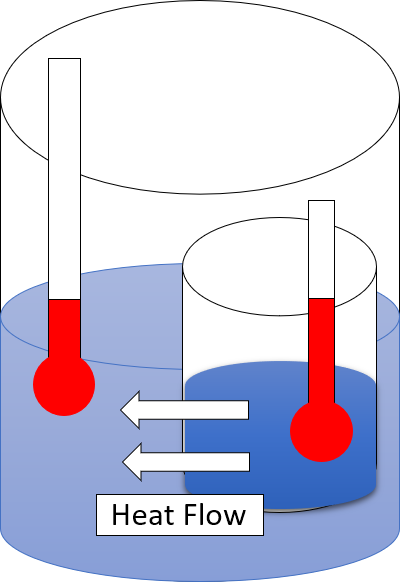

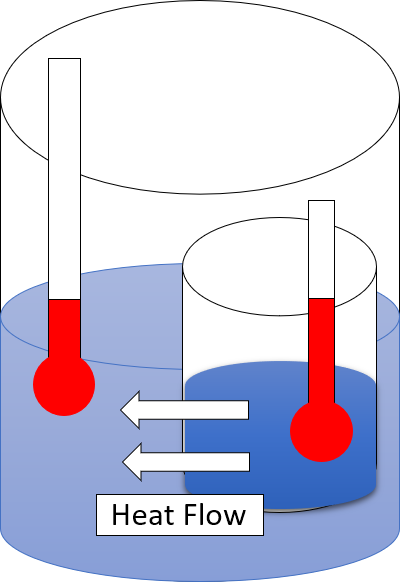

and energy interconversions. One simple statement of the law is that heat always moves from hotter objects to colder objects (or "downhill"), unless energy in some form is supplied to reverse the direction of heat flow

Heat transfer is a discipline of thermal engineering that concerns the generation, use, conversion, and exchange of thermal energy (heat) between physical systems. Heat transfer is classified into various mechanisms, such as thermal conduction, ...

. Another definition is: "Not all heat energy can be converted into work

Work may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

** Manual labour, physical work done by humans

** House work, housework, or homemaking

** Working animal, an animal t ...

in a cyclic process

A thermodynamic cycle consists of a linked sequence of thermodynamic processes that involve transfer of heat and work into and out of the system, while varying pressure, temperature, and other state variables within the system, and that eventual ...

."Young, H. D; Freedman, R. A. (2004). ''University Physics'', 11th edition. Pearson. p. 764.

The second law of thermodynamics in other versions establishes the concept of entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynam ...

as a physical property of a thermodynamic system

A thermodynamic system is a body of matter and/or radiation, confined in space by walls, with defined permeabilities, which separate it from its surroundings. The surroundings may include other thermodynamic systems, or physical systems that are ...

. It can be used to predict whether processes are forbidden despite obeying the requirement of conservation of energy as expressed in the first law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

and provides necessary criteria for spontaneous process In thermodynamics, a spontaneous process is a process which occurs without any external input to the system. A more technical definition is the time-evolution of a system in which it releases free energy and it moves to a lower, more thermodynamic ...

es. The second law may be formulated by the observation that the entropy of isolated systems left to spontaneous evolution cannot decrease, as they always arrive at a state of thermodynamic equilibrium

Thermodynamic equilibrium is an axiomatic concept of thermodynamics. It is an internal state of a single thermodynamic system, or a relation between several thermodynamic systems connected by more or less permeable or impermeable walls. In the ...

where the entropy is highest at the given internal energy. An increase in the combined entropy of system and surroundings accounts for the irreversibility

In science, a process that is not reversible is called irreversible. This concept arises frequently in thermodynamics. All complex natural processes are irreversible, although a phase transition at the coexistence temperature (e.g. melting of i ...

of natural processes, often referred to in the concept of the arrow of time

The arrow of time, also called time's arrow, is the concept positing the "one-way direction" or "asymmetry" of time. It was developed in 1927 by the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington, and is an unsolved general physics question. This ...

.

Historically, the second law was an empirical finding that was accepted as an axiom of thermodynamic theory. Statistical mechanics provides a microscopic explanation of the law in terms of probability distributions of the states of large assemblies of atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, ...

s or molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

s. The second law has been expressed in many ways. Its first formulation, which preceded the proper definition of entropy and was based on caloric theory, is Carnot's theorem, formulated by the French scientist Sadi Carnot, who in 1824 showed that the efficiency of conversion of heat to work in a heat engine has an upper limit. The first rigorous definition of the second law based on the concept of entropy came from German scientist Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

in the 1850s and included his statement that heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

The second law of thermodynamics allows the definition of the concept of thermodynamic temperature

Thermodynamic temperature is a quantity defined in thermodynamics as distinct from kinetic theory or statistical mechanics.

Historically, thermodynamic temperature was defined by Kelvin in terms of a macroscopic relation between thermodynamic ...

, relying also on the zeroth law of thermodynamics

The zeroth law of thermodynamics is one of the four principal laws of thermodynamics. It provides an independent definition of temperature without reference to entropy, which is defined in the second law. The law was established by Ralph H. Fowl ...

.

Introduction

The

The first law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

provides the definition of the internal energy of a thermodynamic system

A thermodynamic system is a body of matter and/or radiation, confined in space by walls, with defined permeabilities, which separate it from its surroundings. The surroundings may include other thermodynamic systems, or physical systems that are ...

, and expresses its change for a closed system

A closed system is a natural physical system that does not allow transfer of matter in or out of the system, although — in contexts such as physics, chemistry or engineering — the transfer of energy (''e.g.'' as work or heat) is allowed.

In ...

in terms of work

Work may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

** Manual labour, physical work done by humans

** House work, housework, or homemaking

** Working animal, an animal t ...

and heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

. It can be linked to the law of conservation of energy. The second law is concerned with the direction of natural processes. It asserts that a natural process runs only in one sense, and is not reversible. For example, when a path for conduction or radiation is made available, heat always flows spontaneously from a hotter to a colder body. Such phenomena are accounted for in terms of entropy change. If an isolated system containing distinct subsystems is held initially in internal thermodynamic equilibrium by internal partitioning by impermeable walls between the subsystems, and then some operation makes the walls more permeable, then the system spontaneously evolves to reach a final new internal thermodynamic equilibrium, and its total entropy, , increases.

In a reversible or quasi-static, idealized process of transfer of energy as heat to a closed thermodynamic system of interest, (which allows the entry or exit of energy – but not transfer of matter), from an auxiliary thermodynamic system, an infinitesimal increment () in the entropy of the system of interest is defined to result from an infinitesimal transfer of heat () to the system of interest, divided by the common thermodynamic temperature of the system of interest and the auxiliary thermodynamic system:

:

Different notations are used for an infinitesimal amount of heat and infinitesimal change of entropy because entropy is a function of state

In the thermodynamics of equilibrium, a state function, function of state, or point function for a thermodynamic system is a mathematical function relating several state variables or state quantities (that describe equilibrium states of a syste ...

, while heat, like work, is not.

For an actually possible infinitesimal process without exchange of mass with the surroundings, the second law requires that the increment in system entropy fulfills the inequality

Inequality may refer to:

Economics

* Attention inequality, unequal distribution of attention across users, groups of people, issues in etc. in attention economy

* Economic inequality, difference in economic well-being between population groups

* ...

:

This is because a general process for this case (no mass exchange between the system and its surroundings) may include work being done on the system by its surroundings, which can have frictional or viscous effects inside the system, because a chemical reaction may be in progress, or because heat transfer actually occurs only irreversibly, driven by a finite difference between the system temperature () and the temperature of the surroundings ().Adkins, C.J. (1968/1983), p. 75.

Note that the equality still applies for pure heat flow (only heat flow, no change in chemical composition and mass),

:

which is the basis of the accurate determination of the absolute entropy of pure substances from measured heat capacity curves and entropy changes at phase transitions, i.e. by calorimetry.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principles of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. p. 617.

Introducing a set of internal variables to describe the deviation of a thermodynamic system from a chemical equilibrium state in physical equilibrium (with the required well-defined uniform pressure ''P'' and temperature ''T''), one can record the equality

:

The second term represents work of internal variables that can be perturbed by external influences, but the system cannot perform any positive work via internal variables. This statement introduces the impossibility of the reversion of evolution of the thermodynamic system in time and can be considered as a formulation of ''the second principle of thermodynamics'' – the formulation, which is, of course, equivalent to the formulation of the principle in terms of entropy.

The zeroth law of thermodynamics

The zeroth law of thermodynamics is one of the four principal laws of thermodynamics. It provides an independent definition of temperature without reference to entropy, which is defined in the second law. The law was established by Ralph H. Fowl ...

in its usual short statement allows recognition that two bodies in a relation of thermal equilibrium have the same temperature, especially that a test body has the same temperature as a reference thermometric body. For a body in thermal equilibrium with another, there are indefinitely many empirical temperature scales, in general respectively depending on the properties of a particular reference thermometric body. The second law allows a distinguished temperature scale, which defines an absolute, thermodynamic temperature

Thermodynamic temperature is a quantity defined in thermodynamics as distinct from kinetic theory or statistical mechanics.

Historically, thermodynamic temperature was defined by Kelvin in terms of a macroscopic relation between thermodynamic ...

, independent of the properties of any particular reference thermometric body.

Various statements of the law

The second law of thermodynamics may be expressed in many specific ways, the most prominent classical statements being the statement byRudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

(1854), the statement by Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

(1851), and the statement in axiomatic thermodynamics by Constantin Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Καραθεοδωρή, Konstantinos Karatheodori; 13 September 1873 – 2 February 1950) was a Greek mathematician who spent most of his professional career in Germany. He made significant ...

(1909). These statements cast the law in general physical terms citing the impossibility of certain processes. The Clausius and the Kelvin statements have been shown to be equivalent.

Carnot's principle

The historical origin of the second law of thermodynamics was in Sadi Carnot's theoretical analysis of the flow of heat in steam engines (1824). The centerpiece of that analysis, now known as a Carnot engine, is an idealheat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state ...

fictively operated in the limiting mode of extreme slowness known as quasi-static, so that the heat and work transfers are between subsystems that are always in their own internal states of thermodynamic equilibrium. It represents the theoretical maximum efficiency of a heat engine operating between any two given thermal or heat reservoirs at different temperatures. Carnot's principle was recognized by Carnot at a time when the caloric theory represented the dominant understanding of the nature of heat, before the recognition of the first law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

, and before the mathematical expression of the concept of entropy. Interpreted in the light of the first law, Carnot's analysis is physically equivalent to the second law of thermodynamics, and remains valid today. Some samples from his book are:

::...''wherever there exists a difference of temperature, motive power can be produced.''

::The production of motive power is then due in steam engines not to an actual consumption of caloric, but ''to its transportation from a warm body to a cold body ...''

::''The motive power of heat is independent of the agents employed to realize it; its quantity is fixed solely by the temperatures of the bodies between which is effected, finally, the transfer of caloric.''

In modern terms, Carnot's principle may be stated more precisely:

::The efficiency of a quasi-static or reversible Carnot cycle depends only on the temperatures of the two heat reservoirs, and is the same, whatever the working substance. A Carnot engine operated in this way is the most efficient possible heat engine using those two temperatures.

Clausius statement

The German scientistRudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

laid the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics in 1850 by examining the relation between heat transfer and work. His formulation of the second law, which was published in German in 1854, is known as the ''Clausius statement'':

Heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.The statement by Clausius uses the concept of 'passage of heat'. As is usual in thermodynamic discussions, this means 'net transfer of energy as heat', and does not refer to contributory transfers one way and the other. Heat cannot spontaneously flow from cold regions to hot regions without external work being performed on the system, which is evident from ordinary experience of

refrigeration

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

, for example. In a refrigerator, heat is transferred from cold to hot, but only when forced by an external agent, the refrigeration system.

Kelvin statements

Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

expressed the second law in several wordings.

::It is impossible for a self-acting machine, unaided by any external agency, to convey heat from one body to another at a higher temperature.

::It is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects.

Equivalence of the Clausius and the Kelvin statements

Suppose there is an engine violating the Kelvin statement: i.e., one that drains heat and converts it completely into work (The drained heat is fully converted to work.) in a cyclic fashion without any other result. Now pair it with a reversed Carnot engine as shown by the right figure. The efficiency of a normal heat engine is ''η'' and so the efficiency of the reversed heat engine is 1/''η''. The net and sole effect of the combined pair of engines is to transfer heat from the cooler reservoir to the hotter one, which violates the Clausius statement. This is a consequence of thefirst law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

, as for the total system's energy to remain the same; , so therefore , where (1) the sign convention of heat is used in which heat entering into (leaving from) an engine is positive (negative) and (2) is obtained by the definition of efficiency of the engine when the engine operation is not reversed. Thus a violation of the Kelvin statement implies a violation of the Clausius statement, i.e. the Clausius statement implies the Kelvin statement. We can prove in a similar manner that the Kelvin statement implies the Clausius statement, and hence the two are equivalent.

Planck's proposition

Planck offered the following proposition as derived directly from experience. This is sometimes regarded as his statement of the second law, but he regarded it as a starting point for the derivation of the second law. ::It is impossible to construct an engine which will work in a complete cycle, and produce no effect except the raising of a weight and cooling of a heat reservoir.Relation between Kelvin's statement and Planck's proposition

It is almost customary in textbooks to speak of the "Kelvin–Planck statement" of the law, as for example in the text by ter Haar and Wergeland. This version, also known as the heat engine statement, of the second law states that ::It is impossible to devise a cyclically operating device, the sole effect of which is to absorb energy in the form of heat from a single thermal reservoir and to deliver an equivalent amount ofwork

Work may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

** Manual labour, physical work done by humans

** House work, housework, or homemaking

** Working animal, an animal t ...

.

Planck's statement

Planck stated the second law as follows. ::Every process occurring in nature proceeds in the sense in which the sum of the entropies of all bodies taking part in the process is increased. In the limit, i.e. for reversible processes, the sum of the entropies remains unchanged. Planck, M. (1897/1903), p. 100. Planck, M. (1926), p. 463, translation by Uffink, J. (2003), p. 131.Roberts, J.K., Miller, A.R. (1928/1960), p. 382. This source is partly verbatim from Planck's statement, but does not cite Planck. This source calls the statement the principle of the increase of entropy. Rather like Planck's statement is that of Uhlenbeck and Ford for ''irreversible phenomena''. ::... in an irreversible or spontaneous change from one equilibrium state to another (as for example the equalization of temperature of two bodies A and B, when brought in contact) the entropy always increases.Principle of Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Καραθεοδωρή, Konstantinos Karatheodori; 13 September 1873 – 2 February 1950) was a Greek mathematician who spent most of his professional career in Germany. He made significant ...

formulated thermodynamics on a purely mathematical axiomatic foundation. His statement of the second law is known as the Principle of Carathéodory, which may be formulated as follows:

In every neighborhood of any state S of an adiabatically enclosed system there are states inaccessible from S.With this formulation, he described the concept of adiabatic accessibility for the first time and provided the foundation for a new subfield of classical thermodynamics, often called geometrical thermodynamics. It follows from Carathéodory's principle that quantity of energy quasi-statically transferred as heat is a holonomic process function, in other words, . Though it is almost customary in textbooks to say that Carathéodory's principle expresses the second law and to treat it as equivalent to the Clausius or to the Kelvin-Planck statements, such is not the case. To get all the content of the second law, Carathéodory's principle needs to be supplemented by Planck's principle, that isochoric work always increases the internal energy of a closed system that was initially in its own internal thermodynamic equilibrium.Münster, A. (1970), p. 45. Planck, M. (1926).

Planck's principle

In 1926,Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (, ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial contributions to theoretical p ...

wrote an important paper on the basics of thermodynamics. He indicated the principle

::The internal energy of a closed system is increased by an adiabatic process, throughout the duration of which, the volume of the system remains constant.

This formulation does not mention heat and does not mention temperature, nor even entropy, and does not necessarily implicitly rely on those concepts, but it implies the content of the second law. A closely related statement is that "Frictional pressure never does positive work." Planck wrote: "The production of heat by friction is irreversible."

Not mentioning entropy, this principle of Planck is stated in physical terms. It is very closely related to the Kelvin statement given just above. It is relevant that for a system at constant volume and mole numbers, the entropy is a monotonic function of the internal energy. Nevertheless, this principle of Planck is not actually Planck's preferred statement of the second law, which is quoted above, in a previous sub-section of the present section of this present article, and relies on the concept of entropy.

A statement that in a sense is complementary to Planck's principle is made by Borgnakke and Sonntag. They do not offer it as a full statement of the second law:

::... there is only one way in which the entropy of a losedsystem can be decreased, and that is to transfer heat from the system.

Differing from Planck's just foregoing principle, this one is explicitly in terms of entropy change. Removal of matter from a system can also decrease its entropy.

Statement for a system that has a known expression of its internal energy as a function of its extensive state variables

The second law has been shown to be equivalent to the internal energy ''U'' being a weakly convex function, when written as a function of extensive properties (mass, volume, entropy, ...).Corollaries

Perpetual motion of the second kind

Before the establishment of the second law, many people who were interested in inventing a perpetual motion machine had tried to circumvent the restrictions offirst law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

by extracting the massive internal energy of the environment as the power of the machine. Such a machine is called a "perpetual motion machine of the second kind". The second law declared the impossibility of such machines.

Carnot theorem

Carnot's theorem (1824) is a principle that limits the maximum efficiency for any possible engine. The efficiency solely depends on the temperature difference between the hot and cold thermal reservoirs. Carnot's theorem states: *All irreversible heat engines between two heat reservoirs are less efficient than a Carnot engine operating between the same reservoirs. *All reversible heat engines between two heat reservoirs are equally efficient with a Carnot engine operating between the same reservoirs. In his ideal model, the heat of caloric converted into work could be reinstated by reversing the motion of the cycle, a concept subsequently known asthermodynamic reversibility

In thermodynamics, a reversible process is a process, involving a system and its surroundings, whose direction can be reversed by infinitesimal changes in some properties of the surroundings, such as pressure or temperature.

Throughout an ent ...

. Carnot, however, further postulated that some caloric is lost, not being converted to mechanical work. Hence, no real heat engine could realize the Carnot cycle

A Carnot cycle is an ideal thermodynamic cycle proposed by French physicist Sadi Carnot in 1824 and expanded upon by others in the 1830s and 1840s. By Carnot's theorem, it provides an upper limit on the efficiency of any classical thermodynam ...

's reversibility and was condemned to be less efficient.

Though formulated in terms of caloric (see the obsolete caloric theory), rather than entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynam ...

, this was an early insight into the second law.

Clausius inequality

TheClausius theorem

The Clausius theorem (1855), also known as the ''Clausius inequality'', states that for a thermodynamic system (e.g. heat engine or heat pump) exchanging heat with external thermal reservoirs and undergoing a thermodynamic cycle,

:-\oint dS_\te ...

(1854) states that in a cyclic process

:

The equality holds in the reversible case and the strict inequality holds in the irreversible case, with ''T''surr as the temperature of the heat bath (surroundings) here. The reversible case is used to introduce the state function entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynam ...

. This is because in cyclic processes the variation of a state function is zero from state functionality.

Thermodynamic temperature

For an arbitrary heat engine, the efficiency is: where ''W''n is the net work done by the engine per cycle, ''q''''H'' > 0 is the heat added to the engine from a hot reservoir, and ''q''''C'' = - , ''q''''C'', < 0. is waste heat given off to a cold reservoir from the engine. Thus the efficiency depends only on the ratio , ''q''''C'', / , ''q''''H'', . Carnot's theorem states that all reversible engines operating between the same heat reservoirs are equally efficient. Thus, any reversible heat engine operating between temperatures ''T''H and ''T''C must have the same efficiency, that is to say, the efficiency is a function of temperatures only: In addition, a reversible heat engine operating between temperatures ''T''1 and ''T''3 must have the same efficiency as one consisting of two cycles, one between ''T''1 and another (intermediate) temperature ''T''2, and the second between ''T''2 and ''T''3, where ''T1'' > ''T2'' > ''T3''. This is because, if a part of the two cycle engine is hidden such that it is recognized as an engine between the reservoirs at the temperatures ''T''1 and ''T''3, then the efficiency of this engine must be same to the other engine at the same reservoirs. If we choose engines such that work done by the one cycle engine and the two cycle engine are same, then the efficiency of each heat engine is written as the below. : , : , : . Here, the engine 1 is the one cycle engine, and the engines 2 and 3 make the two cycle engine where there is the intermediate reservoir at ''T''2. We also have used the fact that the heat passes through the intermediate thermal reservoir at without losing its energy. (I.e., is not lost during its passage through the reservoir at .) This fact can be proved by the following. : In order to have the consistency in the last equation, the heat flown from the engine 2 to the intermediate reservoir must be equal to the heat flown out from the reservoir to the engine 3. Then : Now consider the case where is a fixed reference temperature: the temperature of thetriple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.. It is that temperature and pressure at which the sub ...

of water as 273.16 Kelvin; . Then for any ''T''2 and ''T''3,

:

Therefore, if thermodynamic temperature ''T''* is defined by

:

then the function ''f'', viewed as a function of thermodynamic temperatures, is simply

:

and the reference temperature ''T''1* = 273.16 K × ''f''(''T''1,''T''1) = 273.16 K. (Any reference temperature and any positive numerical value could be usedthe choice here corresponds to the Kelvin

The kelvin, symbol K, is the primary unit of temperature in the International System of Units (SI), used alongside its prefixed forms and the degree Celsius. It is named after the Belfast-born and University of Glasgow-based engineer and phy ...

scale.)

Entropy

According to the Clausius equality, for a ''reversible process'' : That means the line integral is path independent for reversible processes. So we can define a state function S called entropy, which for a reversible process or for pure heat transfer satisfies : With this we can only obtain the difference of entropy by integrating the above formula. To obtain the absolute value, we need thethird law of thermodynamics

The third law of thermodynamics states, regarding the properties of closed systems in thermodynamic equilibrium: This constant value cannot depend on any other parameters characterizing the closed system, such as pressure or applied magnetic fiel ...

, which states that ''S'' = 0 at absolute zero for perfect crystals.

For any irreversible process, since entropy is a state function, we can always connect the initial and terminal states with an imaginary reversible process and integrating on that path to calculate the difference in entropy.

Now reverse the reversible process and combine it with the said irreversible process. Applying the Clausius inequality on this loop, with ''T''surr as the temperature of the surroundings,

:

Thus,

:

where the equality holds if the transformation is reversible.

Notice that if the process is an adiabatic process

In thermodynamics, an adiabatic process (Greek: ''adiábatos'', "impassable") is a type of thermodynamic process that occurs without transferring heat or mass between the thermodynamic system and its environment. Unlike an isothermal proces ...

, then , so .

Energy, available useful work

An important and revealing idealized special case is to consider applying the second law to the scenario of an isolated system (called the total system or universe), made up of two parts: a sub-system of interest, and the sub-system's surroundings. These surroundings are imagined to be so large that they can be considered as an ''unlimited'' heat reservoir at temperature ''TR'' and pressure ''PR'' so that no matter how much heat is transferred to (or from) the sub-system, the temperature of the surroundings will remain ''TR''; and no matter how much the volume of the sub-system expands (or contracts), the pressure of the surroundings will remain ''PR''. Whatever changes to ''dS'' and ''dSR'' occur in the entropies of the sub-system and the surroundings individually, the entropy ''S''tot of the isolated total system must not decrease according to the second law of thermodynamics: : According to thefirst law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

, the change ''dU'' in the internal energy of the sub-system is the sum of the heat ''δq'' added to the sub-system, ''less'' any work ''δw'' done ''by'' the sub-system, ''plus'' any net chemical energy entering the sub-system ''d'' Σ''μiRNi'', so that:

:

where ''μ''''iR'' are the chemical potential

In thermodynamics, the chemical potential of a species is the energy that can be absorbed or released due to a change of the particle number of the given species, e.g. in a chemical reaction or phase transition. The chemical potential of a species ...

s of chemical species in the external surroundings.

Now the heat leaving the reservoir and entering the sub-system is

:

where we have first used the definition of entropy in classical thermodynamics (alternatively, in statistical thermodynamics, the relation between entropy change, temperature and absorbed heat can be derived); and then the Second Law inequality from above.

It therefore follows that any net work ''δw'' done by the sub-system must obey

:

It is useful to separate the work ''δw'' done by the subsystem into the ''useful'' work ''δwu'' that can be done ''by'' the sub-system, over and beyond the work ''pR dV'' done merely by the sub-system expanding against the surrounding external pressure, giving the following relation for the useful work (exergy) that can be done:

:

It is convenient to define the right-hand-side as the exact derivative of a thermodynamic potential, called the ''availability'' or ''exergy

In thermodynamics, the exergy of a system is the maximum useful work possible during a process that brings the system into equilibrium with a heat reservoir, reaching maximum entropy. When the surroundings are the reservoir, exergy is the pot ...

'' ''E'' of the subsystem,

:

The Second Law therefore implies that for any process which can be considered as divided simply into a subsystem, and an unlimited temperature and pressure reservoir with which it is in contact,

:

i.e. the change in the subsystem's exergy plus the useful work done ''by'' the subsystem (or, the change in the subsystem's exergy less any work, additional to that done by the pressure reservoir, done ''on'' the system) must be less than or equal to zero.

In sum, if a proper ''infinite-reservoir-like'' reference state is chosen as the system surroundings in the real world, then the second law predicts a decrease in ''E'' for an irreversible process and no change for a reversible process.

: is equivalent to

This expression together with the associated reference state permits a design engineer

A design engineer is an engineer focused on the engineering design process in any of the various engineering disciplines (including civil, mechanical, electrical, chemical, textiles, aerospace, nuclear, manufacturing, systems, and structural ...

working at the macroscopic scale (above the thermodynamic limit

In statistical mechanics, the thermodynamic limit or macroscopic limit, of a system is the limit for a large number of particles (e.g., atoms or molecules) where the volume is taken to grow in proportion with the number of particles.S.J. Blundel ...

) to utilize the second law without directly measuring or considering entropy change in a total isolated system. (''Also, see process engineer

Process engineering is the understanding and application of the fundamental principles and laws of nature that allow humans to transform raw material and energy into products that are useful to society, at an industrial level. By taking advantage ...

''). Those changes have already been considered by the assumption that the system under consideration can reach equilibrium with the reference state without altering the reference state. An efficiency for a process or collection of processes that compares it to the reversible ideal may also be found (''See second law efficiency''.)

This approach to the second law is widely utilized in engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

practice, environmental accounting Environmental accounting is a subset of accounting proper, its target being to incorporate both economic and environmental information. It can be conducted at the corporate level or at the level of a national economy through the System of Integrated ...

, systems ecology, and other disciplines.

Direction of spontaneous processes

The second law determines whether a proposed physical or chemical process is forbidden or may occur spontaneously. For isolated systems, no energy is provided by the surroundings and the second law requires that the entropy of the system alone must increase: Δ''S'' > 0. Examples of spontaneous physical processes in isolated systems include the following: * 1) Heat can be transferred from a region of higher temperature to a lower temperature (but not the reverse). * 2) Mechanical energy can be converted to thermal energy (but not the reverse). * 3) A solute can move from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration (but not the reverse). However, for some non-isolated systems which can exchange energy with their surroundings, the surroundings exchange enough heat with the system, or do sufficient work on the system, so that the processes occur in the opposite direction. This is possible provided the total entropy change of the system plus the surroundings is positive as required by the second law: Δ''S''tot = Δ''S'' + Δ''S''R > 0. For the three examples given above: * 1) Heat can be transferred from a region of lower temperature to a higher temperature in a refrigerator or in aheat pump

A heat pump is a device that can heat a building (or part of a building) by transferring thermal energy from the outside using a refrigeration cycle. Many heat pumps can also operate in the opposite direction, cooling the building by removing ...

. These machines must provide sufficient work to the system.

* 2) Thermal energy can be converted to mechanical work in a heat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state ...

, if sufficient heat is also expelled to the surroundings.

* 3) A solute can move from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration in the biochemical process of active transport

In cellular biology, ''active transport'' is the movement of molecules or ions across a cell membrane from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration—against the concentration gradient. Active transport requires cellul ...

, if sufficient work is provided by a concentration gradient of a chemical such as ATP or by an electrochemical gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and ...

.

The second law in chemical thermodynamics

For a spontaneous chemical process in a closed system at constant temperature and pressure without non-''PV'' work, the Clausius inequality Δ''S'' > ''Q/T''surr transforms into a condition for the change inGibbs free energy

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy (or Gibbs energy; symbol G) is a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum amount of work that may be performed by a thermodynamically closed system at constant temperature and ...

:

or d''G'' < 0. For a similar process at constant temperature and volume, the change in Helmholtz free energy

In thermodynamics, the Helmholtz free energy (or Helmholtz energy) is a thermodynamic potential that measures the useful work obtainable from a closed thermodynamic system at a constant temperature (isothermal). The change in the Helmholtz ener ...

must be negative, . Thus, a negative value of the change in free energy (''G'' or ''A'') is a necessary condition for a process to be spontaneous. This is the most useful form of the second law of thermodynamics in chemistry, where free-energy changes can be calculated from tabulated enthalpies of formation and standard molar entropies of reactants and products. The chemical equilibrium condition at constant ''T'' and ''p'' without electrical work is d''G'' = 0.

History

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an engine and its surroundings.

Recognizing the significance of

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an engine and its surroundings.

Recognizing the significance of James Prescott Joule

James Prescott Joule (; 24 December 1818 11 October 1889) was an English physicist, mathematician and brewer, born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work (see energy). ...

's work on the conservation of energy, Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

was the first to formulate the second law during 1850, in this form: heat does not flow ''spontaneously'' from cold to hot bodies. While common knowledge now, this was contrary to the caloric theory of heat popular at the time, which considered heat as a fluid. From there he was able to infer the principle of Sadi Carnot and the definition of entropy (1865).

Established during the 19th century, the Kelvin-Planck statement of the Second Law says, "It is impossible for any device that operates on a cycle to receive heat from a single reservoir

A reservoir (; from French ''réservoir'' ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam. Such a dam may be either artificial, built to store fresh water or it may be a natural formation.

Reservoirs can be created in a number of ways, including contro ...

and produce a net amount of work." This was shown to be equivalent to the statement of Clausius.

The ergodic hypothesis is also important for the Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics, and the statistical explanation of the second law of thermodyn ...

approach. It says that, over long periods of time, the time spent in some region of the phase space of microstates with the same energy is proportional to the volume of this region, i.e. that all accessible microstates are equally probable over a long period of time. Equivalently, it says that time average and average over the statistical ensemble are the same.

There is a traditional doctrine, starting with Clausius, that entropy can be understood in terms of molecular 'disorder' within a macroscopic system. This doctrine is obsolescent.Entropy Sites — A GuideContent selected by Frank L. Lambert

Account given by Clausius

In 1865, the German physicist

In 1865, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

stated what he called the "second fundamental theorem in the mechanical theory of heat

The history of thermodynamics is a fundamental strand in the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the history of science in general. Owing to the relevance of thermodynamics in much of science and technology, its history is finely w ...

" in the following form:

:

where ''Q'' is heat, ''T'' is temperature and ''N'' is the "equivalence-value" of all uncompensated transformations involved in a cyclical process. Later, in 1865, Clausius would come to define "equivalence-value" as entropy. On the heels of this definition, that same year, the most famous version of the second law was read in a presentation at the Philosophical Society of Zurich on April 24, in which, in the end of his presentation, Clausius concludes:

The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.This statement is the best-known phrasing of the second law. Because of the looseness of its language, e.g.

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. ...

, as well as lack of specific conditions, e.g. open, closed, or isolated, many people take this simple statement to mean that the second law of thermodynamics applies virtually to every subject imaginable. This is not true; this statement is only a simplified version of a more extended and precise description.

In terms of time variation, the mathematical statement of the second law for an isolated system undergoing an arbitrary transformation is:

:

where

: ''S'' is the entropy of the system and

: ''t'' is time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

.

The equality sign applies after equilibration. An alternative way of formulating of the second law for isolated systems is:

: with

with the sum of the rate of entropy production

Entropy production (or generation) is the amount of entropy which is produced in any irreversible processes such as heat and mass transfer processes including motion of bodies, heat exchange, fluid flow, substances expanding or mixing, anelastic d ...

by all processes inside the system. The advantage of this formulation is that it shows the effect of the entropy production. The rate of entropy production is a very important concept since it determines (limits) the efficiency of thermal machines. Multiplied with ambient temperature it gives the so-called dissipated energy .

The expression of the second law for closed systems (so, allowing heat exchange and moving boundaries, but not exchange of matter) is:

: with

Here

: is the heat flow into the system

: is the temperature at the point where the heat enters the system.

The equality sign holds in the case that only reversible processes take place inside the system. If irreversible processes take place (which is the case in real systems in operation) the >-sign holds. If heat is supplied to the system at several places we have to take the algebraic sum of the corresponding terms.

For open systems (also allowing exchange of matter):

: with

Here is the flow of entropy into the system associated with the flow of matter entering the system. It should not be confused with the time derivative of the entropy. If matter is supplied at several places we have to take the algebraic sum of these contributions.

Statistical mechanics

Statistical mechanics gives an explanation for the second law by postulating that a material is composed of atoms and molecules which are in constant motion. A particular set of positions and velocities for each particle in the system is called a microstate of the system and because of the constant motion, the system is constantly changing its microstate. Statistical mechanics postulates that, in equilibrium, each microstate that the system might be in is equally likely to occur, and when this assumption is made, it leads directly to the conclusion that the second law must hold in a statistical sense. That is, the second law will hold on average, with a statistical variation on the order of 1/ where ''N'' is the number of particles in the system. For everyday (macroscopic) situations, the probability that the second law will be violated is practically zero. However, for systems with a small number of particles, thermodynamic parameters, including the entropy, may show significant statistical deviations from that predicted by the second law. Classical thermodynamic theory does not deal with these statistical variations.Derivation from statistical mechanics

The first mechanical argument of the Kinetic theory of gases that molecular collisions entail an equalization of temperatures and hence a tendency towards equilibrium was due toJames Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

in 1860; Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics, and the statistical explanation of the second law of ther ...

with his H-theorem

In classical statistical mechanics, the ''H''-theorem, introduced by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1872, describes the tendency to decrease in the quantity ''H'' (defined below) in a nearly-ideal gas of molecules.

L. Boltzmann,Weitere Studien über das Wä ...

of 1872 also argued that due to collisions gases should over time tend toward the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution

In physics (in particular in statistical mechanics), the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, or Maxwell(ian) distribution, is a particular probability distribution named after James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann.

It was first defined and use ...

.

Due to Loschmidt's paradox

Loschmidt's paradox, also known as the reversibility paradox, irreversibility paradox or ', is the objection that it should not be possible to deduce an irreversible process from time-symmetric dynamics. This puts the time reversal symmetry of (al ...

, derivations of the Second Law have to make an assumption regarding the past, namely that the system is uncorrelated

In probability theory and statistics, two real-valued random variables, X, Y, are said to be uncorrelated if their covariance, \operatorname ,Y= \operatorname Y- \operatorname \operatorname /math>, is zero. If two variables are uncorrelated, ther ...

at some time in the past; this allows for simple probabilistic treatment. This assumption is usually thought as a boundary condition

In mathematics, in the field of differential equations, a boundary value problem is a differential equation together with a set of additional constraints, called the boundary conditions. A solution to a boundary value problem is a solution to th ...

, and thus the second Law is ultimately a consequence of the initial conditions somewhere in the past, probably at the beginning of the universe (the Big Bang), though other scenarios have also been suggested.

Given these assumptions, in statistical mechanics, the Second Law is not a postulate, rather it is a consequence of the fundamental postulate, also known as the equal prior probability postulate, so long as one is clear that simple probability arguments are applied only to the future, while for the past there are auxiliary sources of information which tell us that it was low entropy. The first part of the second law, which states that the entropy of a thermally isolated system can only increase, is a trivial consequence of the equal prior probability postulate, if we restrict the notion of the entropy to systems in thermal equilibrium. The entropy of an isolated system in thermal equilibrium containing an amount of energy of is:

: