Kansas–Nebraska Act on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial

The topic of a

The topic of a

The debate in the Senate concluded on March 4, 1854, when Douglas, beginning near midnight on March 3, made a five-and-a-half-hour speech. The final vote in favor of passage was 37 to 14. Free-state senators voted 14 to 12 in favor, and slave-state senators supported the bill 23 to 2.

The debate in the Senate concluded on March 4, 1854, when Douglas, beginning near midnight on March 3, made a five-and-a-half-hour speech. The final vote in favor of passage was 37 to 14. Free-state senators voted 14 to 12 in favor, and slave-state senators supported the bill 23 to 2.

Immediate responses to the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act fell into two classes. The less common response was held by Douglas's supporters, who believed that the bill would withdraw "the question of slavery from the halls of Congress and the political arena, committing it to the arbitration of those who were immediately interested in, and alone responsible for, its consequences". In other words, they believed that the Act would leave decisions about whether slavery would be permitted in the hands of the people rather than the Federal government. The far more common response was one of outrage, interpreting Douglas's actions as, in their words, "part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region emigrant from the Old World, and free laborers from our States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves". Especially in the eyes of northerners, the Kansas–Nebraska Act was aggression and an attack on the power and beliefs of free states. The response led to calls for public action against the South, as seen in broadsides that advertised gatherings in northern states to discuss publicly what to do about the presumption of the Act.

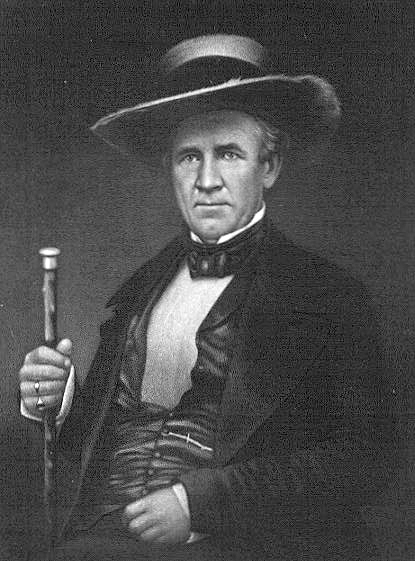

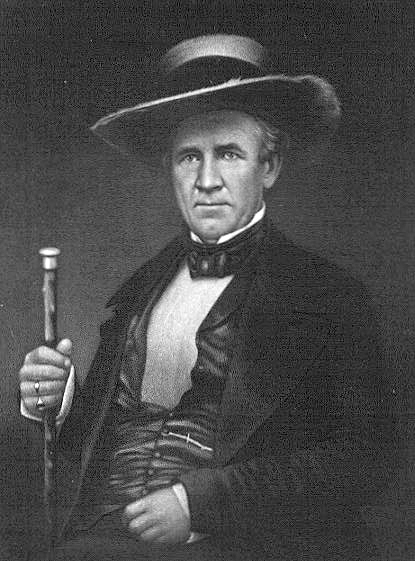

Douglas and former Illinois Representative

Immediate responses to the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act fell into two classes. The less common response was held by Douglas's supporters, who believed that the bill would withdraw "the question of slavery from the halls of Congress and the political arena, committing it to the arbitration of those who were immediately interested in, and alone responsible for, its consequences". In other words, they believed that the Act would leave decisions about whether slavery would be permitted in the hands of the people rather than the Federal government. The far more common response was one of outrage, interpreting Douglas's actions as, in their words, "part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region emigrant from the Old World, and free laborers from our States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves". Especially in the eyes of northerners, the Kansas–Nebraska Act was aggression and an attack on the power and beliefs of free states. The response led to calls for public action against the South, as seen in broadsides that advertised gatherings in northern states to discuss publicly what to do about the presumption of the Act.

Douglas and former Illinois Representative

"Civil War Chronicles: Abolitionist John Doy", ''American Heritage'', Spring 2009. Congressional Democrats suffered huge losses in the mid-term elections of 1854, as voters provided support to a wide array of new parties that opposed the Democrats and the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Pierce deplored the new Republican Party, because of its perceived anti-Southern, anti-slavery stance. To Northerners, the President's perceived Southern bias did anything but de-escalate public mood and helped inflame abolitionist anger.Holt (2010), pp. 91–94, 99, 106–109 Partly due to the unpopularity of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Pierce lost his bid for re-nomination at the 1856 Democratic National Convention to

excerpt and text search

* Burns, Louis F. ''A History of the Osage People'' (2004) * Chambers, William Nisbet. ''Old Bullion Benton: Senator From the New West'' (1956) * Childers, Christopher. "Interpreting Popular Sovereignty: A Historiographical Essay", ''Civil War History'' Volume 57, Number 1, March 2011 pp. 48–7

* Etcheson, Nicole. ''Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era'' (2006) * Foner, Eric. ''Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War'' (1970) . * Freehling, William W. ''The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay 1776–1854'' (1990) . * Holt, Michael. ''The Political Crisis of the 1850s'' (1978) * * Huston, James L. ''Stephen A. Douglas and the dilemmas of democratic equality'' (2007) * Johannsen. Robert W. ''Stephen A. Douglas'' (1973) * * * Manypenny, George W. ''Our Indian Wards'' (1880) * Morrison, Michael. ''Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War'' (1997

online edition

* Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing 1852–1857'' (1947) * Nichols, Roy F. "The Kansas–Nebraska Act: A Century of Historiography". ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 43 (September 1956): 187–212

Online at JSTOR

* Potter, David M. ''The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861'' (1976),

online

* * Stewart, Matthew G. ''The Burden of Western History: Kansas, Collective Memory, and the Reunification of the American Empire, 1854–1913'' (2014) * Wolff, Gerald W., ''The Kansas–Nebraska Bill: Party, Section, and the Coming of the Civil War'', (Revisionist Press, 1977), 385 pp. * Wunder, John R. and Joann M. Ross, eds. ''The Nebraska-Kansas Act of 1854'' (2008), essays by scholars.

Kansas–Nebraska Act

as enacted

10 Stat. 277

in the US Statutes at Large

H.R. 236

on

An annotated bibliography

Millard Fillmore on the Fugitive Slave and Kansas–Nebraska Acts: Original Letter

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854: Popular Sovereignty and the Political Polarization over Slavery

* ttps://archive.today/20130415221319/http://www.shapell.org/manuscript.aspx?171290 President Pierce's Private Correspondence on the Kansas–Nebraska ActShapell Manuscript Foundation

Transcript

available via the National Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Kansas-Nebraska Act 1854 in American law 1854 in American politics 1854 in Kansas Territory 1854 in Nebraska Territory African-American history of Nebraska Bleeding Kansas History of United States expansionism Legal history of Kansas Popular sovereignty Pre-statehood history of Nebraska United States federal territory and statehood legislation May 1854 Expansion of slavery in the United States Origins of the American Civil War Franklin Pierce administration controversies

organic act

In United States law, an organic act is an act of the United States Congress that establishes an administrative agency or local government, for example, the laws that established territory of the United States and specified how they are to ...

that created the territories of Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

. Douglas introduced the bill intending to open up new lands to develop and facilitate the construction of a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous rail transport, railroad trackage that crosses a continent, continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks may be via the Ra ...

. However, the Kansas–Nebraska Act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

, stoking national tensions over slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and contributing to a series of armed conflicts known as "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

".

The United States had acquired vast amounts of land in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

, and since the 1840s, Douglas had sought to establish a territorial government in a portion of the Louisiana Purchase that was still unorganized. Douglas's efforts were stymied by Senator David Rice Atchison of Missouri and other Southern leaders who refused to allow the creation of territories that banned slavery; slavery would have been banned because the Missouri Compromise outlawed slavery in the territory north of latitude 36° 30′ north (except for Missouri). To win the support of Southerners like Atchison, Pierce and Douglas agreed to back the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, with the status of slavery instead decided based on "popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

". Under popular sovereignty, the citizens of each territory, rather than Congress, would determine whether slavery would be allowed.

Douglas's bill to repeal the Missouri Compromise and organize Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory won approval by a wide margin in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, but faced stronger opposition in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

. Though Northern Whigs strongly opposed the bill, it passed the House with the support of almost all Southerners and some Northern Democrats. After the passage of the act, pro- and anti-slavery elements flooded into Kansas to establish a population that would vote for or against slavery, resulting in a series of armed conflicts known as "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

". Douglas and Pierce hoped that popular sovereignty would help bring an end to the national debate over slavery, but the Kansas–Nebraska Act outraged Northerners. The division between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces caused by the Act was the death knell for the ailing Whig Party, which broke apart after the Act. Its Northern remnants would give rise to the anti-slavery Republican Party. The Act, and the tensions over slavery it inflamed, were key events leading to the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

Background

In his 1853 inaugural address, PresidentFranklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

expressed hope that the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

had settled the debate over the issue of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

in the territories. For the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th st ...

and New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomi ...

, lands acquired in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, the Compromise left the issue of slavery to be decided by popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

. The Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

, which banned slavery in territories north of the 36°30′ parallel, remained in place for the other U.S. territories acquired in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

, including a vast unorganized territory often referred to as "Nebraska". As settlers poured into the unorganized territory, and commercial and political interests called for a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous rail transport, railroad trackage that crosses a continent, continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks may be via the Ra ...

through the region, pressure mounted for the organization of the eastern parts of the unorganized territory. Though the organization of the territory was required to develop the region, an organization bill threatened to re-open the contentious debates over slavery in the territories that had taken place during and after the Mexican–American War.

The topic of a

The topic of a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous rail transport, railroad trackage that crosses a continent, continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks may be via the Ra ...

had been discussed since the 1840s. While there were debates over the specifics, especially the route to be taken, there was a public consensus that such a railroad should be built by private interests, and financed by public land grants. In 1845, Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

, then serving in his first term in the U.S. House of Representatives, had submitted an unsuccessful plan to organize the Nebraska Territory formally, as the first step in building a railroad with its eastern terminus in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. Railroad proposals were debated in all subsequent sessions of Congress with cities such as Chicago, St. Louis, Quincy, Memphis, and New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

competing to be the jumping-off point for the construction.

Several proposals in late 1852 and early 1853 had strong support, but they failed because of disputes over whether the railroad would follow a northern or a southern route. In early 1853, the House of Representatives passed a bill 107 to 49 to organize the Nebraska Territory in the land west of Iowa and Missouri. In March, the bill moved to the Senate Committee on Territories, which was headed by Douglas. Missouri Senator David Atchison announced that he would support the Nebraska proposal only if slavery were to be permitted. While the bill was silent on this issue, slavery would have been prohibited under the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

in the territory north of 36°30' latitude and west of the Mississippi River. Other Southern senators were as inflexible as Atchison. By a vote of 23 to 17, the Senate voted to table

Table may refer to:

* Table (database), how the table data arrangement is used within the databases

* Table (furniture), a piece of furniture with a flat surface and one or more legs

* Table (information), a data arrangement with rows and column ...

the motion, with every senator from the states south of Missouri voting to the table.

During the Senate adjournment, the issues of the railroad and the repeal of the Missouri Compromise became entangled in Missouri politics, as Atchison campaigned for re-election against the forces of Thomas Hart Benton. Atchison was maneuvered into choosing between antagonizing the state's railroad interests or its slaveholders. Finally, he took the position that he would rather see Nebraska "sink in hell" before he would allow it to be overrun by free soilers.

Representatives then generally found lodging in boarding houses when they were in the nation's capital to perform their legislative duties. Atchison shared lodgings in an F Street house shared by the leading Southerners in Congress. He was the Senate's President pro tempore. His housemates included Robert T. Hunter (from Virginia, chairman of the Finance Committee), James Mason (from Virginia, chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee) and Andrew P. Butler (from South Carolina, chairman of the Judiciary Committee). When Congress reconvened on December 5, 1853, the group, termed the F Street Mess, along with Virginian William O. Goode, formed the nucleus that would insist on slaveholder equality in Nebraska. Douglas was aware of the group's opinions and power and knew that he needed to address its concerns. Douglas was also a fervent believer in popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

—the policy of letting the voters, almost exclusively white males, of a territory decide whether or not slavery should exist in it.

Iowa Senator Augustus C. Dodge immediately reintroduced the same legislation to organize Nebraska that had stalled in the previous session; it was referred to Douglas's committee on December 14. Douglas, hoping to achieve the support of the Southerners, publicly announced that the same principle that had been established in the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

should apply in Nebraska.

In the Compromise of 1850, Utah and New Mexico Territories had been organized without any restrictions on slavery, and many supporters of Douglas argued that the compromise had already superseded the Missouri Compromise. The territories were, however, given the authority to decide for themselves whether they would apply for statehood as either free or slaves states whenever they chose to apply. The two territories, however, unlike Nebraska, had not been part of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

and had arguably never been subject to the Missouri Compromise.

Congressional action

Introduction of Nebraska bill

The bill was reported to the main body of the Senate on January 4, 1854. It had been modified by Douglas, who had also authored theNew Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomi ...

and Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th st ...

Acts, to mirror the language from the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

. In the bill, a vast new Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

was created to extend from Kansas north to the 49th parallel, the US–Canada border. A large portion of Nebraska Territory would soon be split off into Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

(1861), and smaller portions transferred to Colorado Territory

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861, until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the 38th State of Colorado.

The territory was organized ...

(1861) and Idaho Territory (1863) before the balance of the land became the State of Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

in 1867.

Furthermore, any decisions on slavery in the new lands were to be made "when admitted as a state or states, the said territory, or any portion of the same, shall be received into the Union, with or without slavery, as their constitution may prescribe at the time of their admission." In a report accompanying the bill, Douglas's committee wrote that the Utah and New Mexico Acts:

The report compared the situation in New Mexico and Utah with the situation in Nebraska. In the first instance, many had argued that slavery had previously been prohibited under Mexican law, just as it was prohibited in Nebraska under the Missouri Compromise. Just as the creation of New Mexico and Utah territories had not ruled on the validity of Mexican law on the acquired territory, the Nebraska bill was neither "affirming nor repealing ... the Missouri act". In other words, popular sovereignty was being established by ignoring, rather than addressing, the problem presented by the Missouri Compromise.

Douglas's attempt to finesse his way around the Missouri Compromise did not work. Kentucky Whig Archibald Dixon believed that unless the Missouri Compromise was explicitly repealed, slaveholders would be reluctant to move to the new territory until slavery was approved by the settlers, who would most likely oppose slavery. On January 16 Dixon surprised Douglas by introducing an amendment that would repeal the section of the Missouri Compromise that prohibited slavery north of the 36°30' parallel. Douglas met privately with Dixon and in the end, despite his misgivings on Northern reaction, agreed to accept Dixon's arguments.

A similar amendment was offered in the House by Philip Phillips of Alabama. With the encouragement of the "F Street Mess", Douglas met with them and Phillips to ensure that the momentum for passing the bill remained with the Democratic Party. They arranged to meet with President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

to ensure that the issue would be declared a test of party loyalty within the Democratic Party.

Meeting with Pierce

Pierce was not enthusiastic about the implications of repealing the Missouri Compromise and had barely referred to Nebraska in hisState of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a Joint session of the United States Congress, joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning ...

message delivered December 5, 1853, just a month before. Close advisors Senator Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

of Michigan, a proponent of popular sovereignty as far back as 1848 as an alternative to the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, and Secretary of State William L. Marcy both told Pierce that repeal would create serious political problems. The full cabinet met and only Secretary of War Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

and Secretary of Navy James C. Dobbin supported repeal. Instead, the president and cabinet submitted to Douglas an alternative plan that would have sought out a judicial ruling on the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. Both Pierce and Attorney General Caleb Cushing believed that the Supreme Court would find it unconstitutional.

Douglas's committee met later that night. Douglas was agreeable to the proposal, but the Atchison group was not. Determined to offer the repeal to Congress on January 23 but reluctant to act without Pierce's commitment, Douglas arranged through Davis to meet with Pierce on January 22 even though it was a Sunday when Pierce generally refrained from conducting any business. Douglas was accompanied at the meeting by Atchison, Hunter, Phillips, and John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.

Douglas and Atchison first met alone with Pierce before the whole group convened. Pierce was persuaded to support repeal, and at Douglas' insistence, Pierce provided a written draft, asserting that the Missouri Compromise had been made inoperative by the principles of the Compromise of 1850. Pierce later informed his cabinet, which concurred with the change of direction. The ''Washington Union'', the communications organ for the administration, wrote on January 24 that support for the bill would be "a test of Democratic orthodoxy".

Debate in Senate

On January 23, a revised bill was introduced in the Senate that repealed the Missouri Compromise and split the unorganized land into two new territories: Kansas and Nebraska. The division was the result of concerns expressed by settlers already in Nebraska as well as the senators from Iowa, who were concerned with the location of the territory's seat of government if such a large territory were created. Existing language to affirm the application of all other laws of the United States in the new territory was supplemented by the language agreed on with Pierce: "except the eighth section of the act preparatory to the admission of Missouri into the Union, approved March 6, 1820 [theMissouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

], which was superseded by the legislation of 1850, commonly called the compromise measures [the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

], and is declared inoperative." Identical legislation was soon introduced in the House.

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that the country then became convulsed with two interconnected battles over slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. A political battle was being fought in Congress over the question of slavery in the new states that were coming. At the same time, there was a moral debate. Southerners claimed that slavery was beneficent, endorsed by the Bible, and generally good policy, whose expansion must be supported. The publications and speeches of abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

, some of them former slaves themselves, were telling Northerners that the supposed beneficence of slavery was a Southern lie, and that enslaving another person was un-Christian, a horrible sin that must be fought. Both battles were "fought with a pertinacity, bitterness, and rancor unknown even in Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

days". The freesoilers were at a distinct disadvantage in Congress. The Democrats held large majorities in each house, and Douglas, "a ferocious fighter, the fiercest, most ruthless, and most unscrupulous that Congress had perhaps ever known", led a tightly disciplined party. In the nation at large, the opponents of Nebraska hoped to achieve a moral victory. The ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', which had earlier supported Pierce, predicted that this would be the last straw for Northern supporters of the slavery forces and would "create a deep-seated, intense, and ineradicable hatred of the institution which will crush its political power, at all hazards, and at any cost".

The day after the bill was reintroduced, two Ohioans, Representative Joshua Giddings and Senator Salmon P. Chase, published a free-soil response, "Appeal of the Independent Democrats The Appeal of the Independent Democrats (the full title was "Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States") was a manifesto issued in January 1854, in response to the introduction into the United States Senate o ...

in Congress to the People of the United States":

Douglas took the appeal personally and responded in Congress, when the debate was opened on January 30 before a full House and packed gallery. Douglas biographer Robert W. Johanssen described part of the speech:

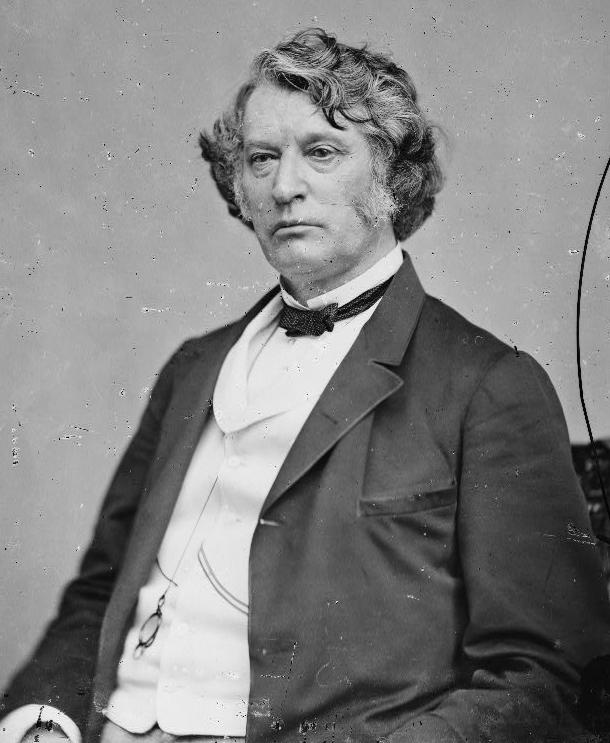

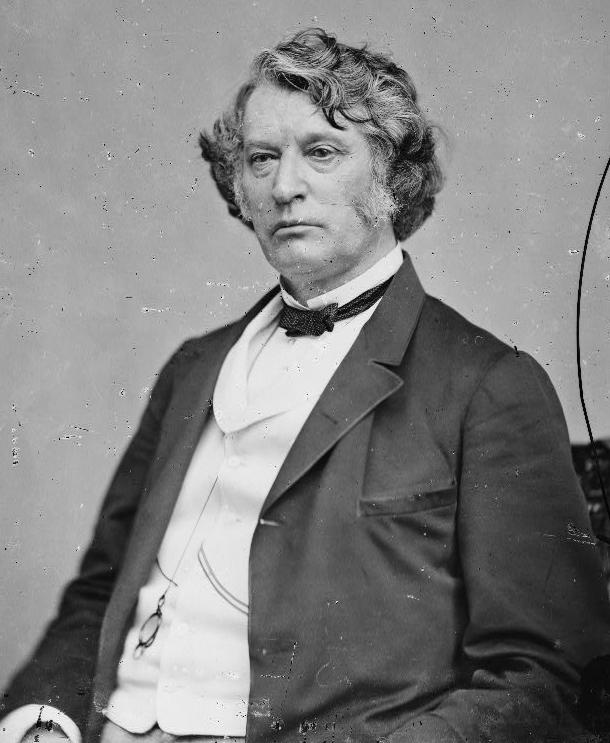

The debate would continue for four months, as many Anti-Nebraska political rallies were held across the north. Douglas remained the main advocate for the bill while Chase, William Seward, of New York, and Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

, of Massachusetts, led the opposition. The ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' (from 1914: ''New York Tribune'') was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s ...

'' wrote on March 2:

The debate in the Senate concluded on March 4, 1854, when Douglas, beginning near midnight on March 3, made a five-and-a-half-hour speech. The final vote in favor of passage was 37 to 14. Free-state senators voted 14 to 12 in favor, and slave-state senators supported the bill 23 to 2.

The debate in the Senate concluded on March 4, 1854, when Douglas, beginning near midnight on March 3, made a five-and-a-half-hour speech. The final vote in favor of passage was 37 to 14. Free-state senators voted 14 to 12 in favor, and slave-state senators supported the bill 23 to 2.

Debate in House of Representatives

On March 21, 1854, as a delaying tactic in the House of Representatives, the legislation was referred by a vote of 110 to 95 to theCommittee of the Whole

A committee of the whole is a meeting of a legislative or deliberative assembly using procedural rules that are based on those of a committee, except that in this case the committee includes all members of the assembly. As with other (standing) ...

, where it was the last item on the calendar. Realizing from the vote to stall that the act faced an uphill struggle, the Pierce administration made it clear to all Democrats that passage of the bill was essential to the party and would dictate how federal patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

would be handled. Davis and Cushing, from Massachusetts, along with Douglas, spearheaded the partisan efforts. By the end of April, Douglas believed that there were enough votes to pass the bill. The House leadership then began a series of roll call votes in which legislation ahead of the Kansas–Nebraska Act was called to the floor and tabled without debate.

Thomas Hart Benton was among those speaking forcefully against the measure. On April 25, in a House speech that biographer William Nisbet Chambers called "long, passionate, historical, ndpolemical", Benton attacked the repeal of the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

, which he "had stood upon ... above thirty years, and intended to stand upon it to the end—solitary and alone, if need be; but preferring company". The speech was distributed afterward as a pamphlet when opposition to the action moved outside the walls of Congress.

It was not until May 8 that the debate began in the House. The debate was even more intense than in the Senate. While it seemed to be a foregone conclusion that the bill would pass, the opponents went all out to fight it. Historian Michael Morrison wrote:

The floor debate was handled by Alexander Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the first and only vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 unti ...

, of Georgia, who insisted that the Missouri Compromise had never been a true compromise but had been imposed on the South. He argued that the issue was whether republican principles, "that the citizens of every distinct community or State should have the right to govern themselves in their domestic matters as they please", would be honored.

The final House vote in favor of the bill was 113 to 100. Northern Democrats supported the bill 44 to 42, but all 45 northern Whigs opposed it. Southern Democrats voted in favor by 57 to 2, and Southern Whigs supported it by 12 to 7.

Enactment

PresidentFranklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

signed the Kansas–Nebraska Act into law on May 30, 1854. This act repealed the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

, "substituting for the ban on slavery what Douglas called 'popular sovereignty' ... arous nga storm of protest throughout the North".

Aftermath

Immediate responses to the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act fell into two classes. The less common response was held by Douglas's supporters, who believed that the bill would withdraw "the question of slavery from the halls of Congress and the political arena, committing it to the arbitration of those who were immediately interested in, and alone responsible for, its consequences". In other words, they believed that the Act would leave decisions about whether slavery would be permitted in the hands of the people rather than the Federal government. The far more common response was one of outrage, interpreting Douglas's actions as, in their words, "part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region emigrant from the Old World, and free laborers from our States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves". Especially in the eyes of northerners, the Kansas–Nebraska Act was aggression and an attack on the power and beliefs of free states. The response led to calls for public action against the South, as seen in broadsides that advertised gatherings in northern states to discuss publicly what to do about the presumption of the Act.

Douglas and former Illinois Representative

Immediate responses to the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act fell into two classes. The less common response was held by Douglas's supporters, who believed that the bill would withdraw "the question of slavery from the halls of Congress and the political arena, committing it to the arbitration of those who were immediately interested in, and alone responsible for, its consequences". In other words, they believed that the Act would leave decisions about whether slavery would be permitted in the hands of the people rather than the Federal government. The far more common response was one of outrage, interpreting Douglas's actions as, in their words, "part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region emigrant from the Old World, and free laborers from our States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves". Especially in the eyes of northerners, the Kansas–Nebraska Act was aggression and an attack on the power and beliefs of free states. The response led to calls for public action against the South, as seen in broadsides that advertised gatherings in northern states to discuss publicly what to do about the presumption of the Act.

Douglas and former Illinois Representative Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

aired their disagreement over the Kansas–Nebraska Act in seven public speeches during September and October 1854. Lincoln gave his most comprehensive argument against slavery and the provisions of the act in Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is a city in Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. Located on the Illinois River, the city had a population of 113,150 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Ill ...

, on October 16, in the Peoria Speech. He and Douglas both spoke to the large audience, Douglas first and Lincoln in response, two hours later. Lincoln's three-hour speech presented thorough moral, legal, and economic arguments against slavery and raised Lincoln's political profile for the first time. The speeches set the stage for the Lincoln-Douglas debates four years later, when Lincoln sought Douglas's Senate seat.

Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent political confrontations in theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

between 1854 and 1861 involving anti-slavery " Free-Staters" and pro-slavery "Border Ruffian

Border ruffians were Proslavery thought, proslavery raiders who crossed into the Kansas Territory from Missouri during the mid-19th century to help ensure the territory entered the United States as a Slave states and free states, slave state. ...

", or "Southern" elements in Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

. At the heart of the conflict was the question of whether Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

would allow or outlaw slavery, and thus enter the Union as a slave state or a free state.

Pro-slavery settlers came to Kansas mainly from neighboring Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, successfully vote stacking to form a temporary pro-slavery government prior to statehood. Their influence in territorial elections was often bolstered by resident Missourians who crossed into Kansas solely for voting in such ballots. They formed groups such as the Blue Lodges and were dubbed '' border ruffians'', a term coined by the opponent and abolitionist Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

. Abolitionist settlers, known as " jayhawkers", moved from the East expressly to make Kansas a free state. A clash between the opposing sides was inevitable.

Successive territorial governors, usually sympathetic to slavery, attempted to maintain the peace. The territorial capital of Lecompton, the target of much agitation, became such a hostile environment for Free-Staters that they set up their own, unofficial legislature at Topeka.

John Brown and his sons gained notoriety in the fight against slavery by murdering five pro-slavery farmers with a broadsword in the Pottawatomie massacre. Brown also helped defend a few dozen Free-State supporters from several hundred angry pro-slavery supporters at Osawatomie.

Effect on Native American tribes

Before the organization of the Kansas–Nebraska territory in 1854, the Kansas and Nebraska Territories were consolidated as part of theIndian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

. Throughout the 1830s, large-scale relocations of Native American tribes to the Indian Territory took place, with many Southeastern nations removed to present-day Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, a process ordered by the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

of 1830 and known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

, and many Midwestern nations removed by way of the treaty to present-day Kansas. Among the latter were the Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

, Kickapoo, Kaskaskia and Peoria, Ioway, and Miami

Miami is a East Coast of the United States, coastal city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County in South Florida. It is the core of the Miami metropolitan area, which, with a populat ...

. The passing of the Kansas–Nebraska Act came into direct conflict with the relocations. White American settlers from both the free-soil North and pro-slavery South flooded the Northern Indian Territory, hoping to influence the vote on slavery that would come following the admittance of Kansas and, to a lesser extent, Nebraska to the United States.

To avoid and/or alleviate the reservation-settlement problem, further treaty negotiations were attempted with the tribes of Kansas and Nebraska. In 1854 alone, the U.S. agreed to acquire lands in Kansas or Nebraska from several tribes including the Kickapoo, Delaware, Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, Shawnee, Otoe

The Otoe ( Chiwere: Jiwére) are a Native American people of the Midwestern United States. The Otoe language, Chiwere, is part of the Siouan family and closely related to that of the related Iowa, Missouria, and Ho-Chunk tribes.

Histori ...

and Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, Miami, and Kaskaskia and Peoria. In exchange for their land cessions, the tribes largely received small reservations in the Indian Territory of Oklahoma or Kansas in some cases.

For the nations that remained in Kansas beyond 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act introduced a host of other problems. In 1855, white "squatters

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building (usually residential) that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there wer ...

" built the city of Leavenworth on the Delaware reservation without the consent of either Delaware or the US government. When Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny ordered military support in removing the squatters, both the military and the squatters refused to comply, undermining both Federal authority and the treaties in place with Delaware. In addition to the violations of treaty agreements, other promises made were not being kept. Construction and infrastructure improvement projects dedicated to nearly every treaty, for example, took a great deal longer than expected. Beyond that, however, the most damaging violation by white American settlers was the mistreatment of Native Americans and their properties. Personal maltreatment, stolen property, and deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

have all been cited. Furthermore, the squatters' premature and illegal settlement of the Kansas Territory jeopardized the value of the land, and with it the future of the Indian tribes living on them. Because treaties were land cessions and purchases, the value of the land handed over to the Federal government was critical to the payment received by a given Native nation. Deforestation, destruction of property, and other general injuries to the land lowered the value of the territories that were ceded by the Kansas Territory tribes.

Manypenny's 1856 "Report on Indian Affairs" explained the devastating effect on Indian populations of diseases that white settlers brought to Kansas. Without providing statistics, Indian Affairs Superintendent to the area Colonel Alfred Cumming reported at least more deaths than births in most tribes in the area. While noting intemperance, or alcoholism

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World He ...

, as a leading cause of death, Cumming specifically cited cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, and measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, none of which the Native Americans were able to treat. The disastrous epidemics exemplified the Osage people, who lost an estimated 1300 lives to scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, measles, smallpox, and scrofula between 1852 and 1856,Louis F. Burns, ''A History of the Osage People'' (2004) 239 contributing, in part, to the massive decline in population, from 8000 in 1850 to just 3500 in 1860.Louis F. Burns, ''A History of the Osage People'' (2004) 243 The Osage had already encountered epidemics associated with relocation and white settlement. The initial removal acts in the 1830s brought both White American settlers and foreign Native American tribes to the Great Plains and into contact with the Osage people. Between 1829 and 1843, influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

, cholera, and smallpox killed an estimated 1242 Osage Indians, resulting in a population recession of roughly 20 percent between 1830 and 1850.

Destruction of the Whig party

From a political standpoint, the Whig Party had been in decline in the South because of the effectiveness with which it had been hammered by the Democratic Party over slavery. The Southern Whigs hoped that by seizing the initiative on this issue, they would be identified as strong defenders of slavery. Many Northern Whigs broke with them in the Act. The American party system had been dominated by Whigs and Democrats for decades leading up to the Civil War. But the Whig party's increasing internal divisions had made it a party of strange bedfellows by the 1850s. An ascendant anti-slavery wing clashed with a traditionalist and increasingly pro-slavery Southern wing. These divisions came to a head in the 1852 election, where Whig candidateWinfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

was trounced by Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

. Southern Whigs, who had supported the prior Whig president Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

, had been burned by Taylor and were unwilling to support another Whig. Taylor, who despite being a slave owner, had proved notably anti-slave despite campaigning neutrally on the issue. With the loss of Southern Whig support and the loss of votes in the North to the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party or the Free Democracy, was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party. The party was focused o ...

, Whigs seemed doomed. So they were, as they would never again contest a presidential election.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act was the final nail in the Whig coffin. It was also the spark that began the Republican Party, which would take in both Whigs and Free Soilers (as well as sympathetic northern Democrats like Frémont) to fill the anti-slavery void that the Whig Party had never seemed willing to fill. The changes in the act were viewed by anti-slavery Northerners as an aggressive, expansionist maneuver by the slave-owning South. Opponents of the Act were intensely motivated and began forming a new party. The party began as a coalition of anti-slavery Conscience Whigs such as Zachariah Chandler and Free Soilers such as Salmon P. Chase.Eric Foner, ''Free soil, free labor, free men: the ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War'' (1970).

The first anti-Nebraska local meeting where "Republican" was suggested as a name for a new anti-slavery party was held in a Ripon, Wisconsin

Ripon () is a city in Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 7,863 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The city is surrounded by the Ripon (town), Wisconsin, Town of Ripon.

Ripon is home to the Little White S ...

schoolhouse on March 20, 1854. The first statewide convention that formed a platform and nominated candidates under the Republican name was held near Jackson, Michigan

Jackson is a city in Jackson County, Michigan, United States, and its county seat. The population was 31,309 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located along Interstate 94 in Michigan, Interstate 94 and U.S. Route 127 in Michigan, U.S ...

, on July 6, 1854. At that convention, the party opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories and selected a statewide slate of candidates. The Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

took the lead in forming state Republican Party tickets; apart from St. Louis and a few areas adjacent to free states, there were no efforts to organize the Party in the Southern states. So was born the Republican Party—campaigning on the popular, emotional issue of "free soil" in the frontier—which would capture the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

just six years later.

Later developments

The Kansas–Nebraska Act divided the nation and pointed it toward civil war.Tom Huntington"Civil War Chronicles: Abolitionist John Doy", ''American Heritage'', Spring 2009. Congressional Democrats suffered huge losses in the mid-term elections of 1854, as voters provided support to a wide array of new parties that opposed the Democrats and the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Pierce deplored the new Republican Party, because of its perceived anti-Southern, anti-slavery stance. To Northerners, the President's perceived Southern bias did anything but de-escalate public mood and helped inflame abolitionist anger.Holt (2010), pp. 91–94, 99, 106–109 Partly due to the unpopularity of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Pierce lost his bid for re-nomination at the 1856 Democratic National Convention to

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

. Pierce was the first elected president who actively sought reelection but was denied his party's nomination for a second term. Republicans nominated John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

in the 1856 presidential election and campaigned on "Bleeding Kansas" and the unpopularity of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Buchanan won the election, but Frémont carried a majority of the free states. Two days after Buchanan's inauguration, Chief Justice Roger Taney delivered the ''Dred Scott'' decision, which asserted that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories. Douglas continued to support the doctrine of popular sovereignty, but Buchanan insisted that Democrats respect the ''Dred Scott'' decision and its repudiation of federal interference with slavery in the territories.

Guerrilla warfare in Kansas continued throughout Buchanan's presidency and extended into the 1860s, continuing until the American Civil War ended in 1865, with many unjust killings and lootings performed by partisans on either side of the border. Buchanan attempted to admit Kansas as a state under the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, but Kansas voters rejected that constitution in an August 1858 referendum. Anti-slavery delegates won a majority of the elections to the 1859 Kansas constitutional convention, and Kansas won admission as a free state under the anti-slavery Wyandotte Constitution

The Wyandotte Constitution is the constitution of the U.S. state of Kansas. Amended many times (including a universal suffrage amendment in 1912), the Wyandotte Constitution is still the constitution of Kansas.

Background

The Kansas Territory wa ...

in the final months of Buchanan's presidency.

See also

* History of slavery in Nebraska * History of slavery in KansasReferences

Citations

Sources

*excerpt and text search

* Burns, Louis F. ''A History of the Osage People'' (2004) * Chambers, William Nisbet. ''Old Bullion Benton: Senator From the New West'' (1956) * Childers, Christopher. "Interpreting Popular Sovereignty: A Historiographical Essay", ''Civil War History'' Volume 57, Number 1, March 2011 pp. 48–7

* Etcheson, Nicole. ''Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era'' (2006) * Foner, Eric. ''Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War'' (1970) . * Freehling, William W. ''The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay 1776–1854'' (1990) . * Holt, Michael. ''The Political Crisis of the 1850s'' (1978) * * Huston, James L. ''Stephen A. Douglas and the dilemmas of democratic equality'' (2007) * Johannsen. Robert W. ''Stephen A. Douglas'' (1973) * * * Manypenny, George W. ''Our Indian Wards'' (1880) * Morrison, Michael. ''Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War'' (1997

online edition

* Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing 1852–1857'' (1947) * Nichols, Roy F. "The Kansas–Nebraska Act: A Century of Historiography". ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 43 (September 1956): 187–212

Online at JSTOR

* Potter, David M. ''The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861'' (1976),

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

-winning scholarly history.

* SenGupta, Gunja. "Bleeding Kansas: A Review Essay". ''Kansas History'' 24 (Winter 2001/2002): 318–341online

* * Stewart, Matthew G. ''The Burden of Western History: Kansas, Collective Memory, and the Reunification of the American Empire, 1854–1913'' (2014) * Wolff, Gerald W., ''The Kansas–Nebraska Bill: Party, Section, and the Coming of the Civil War'', (Revisionist Press, 1977), 385 pp. * Wunder, John R. and Joann M. Ross, eds. ''The Nebraska-Kansas Act of 1854'' (2008), essays by scholars.

External links

*Kansas–Nebraska Act

as enacted

10 Stat. 277

in the US Statutes at Large

H.R. 236

on

Congress.gov

Congress.gov is the online database of United States Congress legislative information. Congress.gov is a joint project of the Library of Congress, the House, the Senate and the Government Publishing Office.

Congress.gov was in beta in 2012, and ...

An annotated bibliography

Millard Fillmore on the Fugitive Slave and Kansas–Nebraska Acts: Original Letter

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854: Popular Sovereignty and the Political Polarization over Slavery

* ttps://archive.today/20130415221319/http://www.shapell.org/manuscript.aspx?171290 President Pierce's Private Correspondence on the Kansas–Nebraska ActShapell Manuscript Foundation

Transcript

available via the National Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Kansas-Nebraska Act 1854 in American law 1854 in American politics 1854 in Kansas Territory 1854 in Nebraska Territory African-American history of Nebraska Bleeding Kansas History of United States expansionism Legal history of Kansas Popular sovereignty Pre-statehood history of Nebraska United States federal territory and statehood legislation May 1854 Expansion of slavery in the United States Origins of the American Civil War Franklin Pierce administration controversies