Kalmyk people on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kalmyks ( Kalmyk: Хальмгуд, ''Xaľmgud'', Mongolian: Халимагууд, ''Halimaguud''; russian: Калмыки, translit=Kalmyki, archaically

Together, these nomadic tribes roamed the grassy plains of western Inner Asia, between Lake Balkhash in present-day eastern

Together, these nomadic tribes roamed the grassy plains of western Inner Asia, between Lake Balkhash in present-day eastern

At the beginning of the 17th century, the First Altan Khan drove the

At the beginning of the 17th century, the First Altan Khan drove the  Under the dynamic leadership of Erdeni Batur, the Dzungars stopped the expansion of the first Altan Khan and began planning the resurrection of the Four Oirat under the Dzungar banner. In furtherance of such plans, Erdeni Batur designed and built a capital city called Kubak-sari on the

Under the dynamic leadership of Erdeni Batur, the Dzungars stopped the expansion of the first Altan Khan and began planning the resurrection of the Four Oirat under the Dzungar banner. In furtherance of such plans, Erdeni Batur designed and built a capital city called Kubak-sari on the

Upon arrival to the lower Volga region in 1630, the Oirats encamped on land that was once part of the Astrakhan Khanate, but was now claimed by the

Upon arrival to the lower Volga region in 1630, the Oirats encamped on land that was once part of the Astrakhan Khanate, but was now claimed by the

Historically, Oirat identified themselves by their respective sub-group names. In the 15th century, the three major groups of Oirat formed an alliance, adopting "Dörben Oirat" as their collective name. In the early 17th century, a second great Oirat Confederation emerged, which later became the Dzungar Empire. While the Dzungars (initially Choros, Dörbet and Khoit tribes) were establishing their empire in Central Eurasia, the Khoshuts were establishing the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet, protecting the Gelugpa sect from its enemies, and the Torghuts formed the Kalmyk Khanate in the lower Volga region.

After encamping, the Oirats began to identify themselves as "Kalmyk." This named was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians to describe them. The Oirats used this name in their dealings with outsiders, viz., their Russian and Muslim neighbors. But, they continued to refer to themselves by their tribal, clan, or other internal affiliations.

The name Kalmyk, however, wasn't immediately accepted by all of the Oirat tribes in the lower Volga region. As late as 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars (refugees from the Manchu Empire) referred to themselves and the Torghuts exclusively as Oirats. The Torghuts, by contrast, used the name Kalmyk for themselves as well as the Khoshut and Dzungars. (Khodarkovsky, 1992:8)

Generally, European scholars have identified all western Mongolians collectively as Kalmyks, regardless of their location ( Ramstedt, 1935: v–vi). Such scholars (e.g. Sebastian Muenster) have relied on Muslim sources who traditionally used the word "Kalmyk" to describe western Mongolians in a derogatory manner and the western Mongols of China and Mongolia have regarded that name as a term of abuse (Haslund, 1935:214–215). Instead, they use the name Oirat or they go by their respective tribal names, e.g., Khoshut, Dörbet, Choros, Torghut, Khoit, Bayid, Mingat, etc. (Anuchin, 1914:57).

Over time, the descendants of the Oirat migrants in the lower Volga region embraced the name "Kalmyk" irrespective of their locations, viz., Astrakhan, the Don Cossack region, Orenburg, Stavropol, the Terek and the Ural Mountains. Another generally accepted name is ''Ulan Zalata'' or the "red-buttoned ones" (Adelman, 1960:6).

Historically, Oirat identified themselves by their respective sub-group names. In the 15th century, the three major groups of Oirat formed an alliance, adopting "Dörben Oirat" as their collective name. In the early 17th century, a second great Oirat Confederation emerged, which later became the Dzungar Empire. While the Dzungars (initially Choros, Dörbet and Khoit tribes) were establishing their empire in Central Eurasia, the Khoshuts were establishing the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet, protecting the Gelugpa sect from its enemies, and the Torghuts formed the Kalmyk Khanate in the lower Volga region.

After encamping, the Oirats began to identify themselves as "Kalmyk." This named was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians to describe them. The Oirats used this name in their dealings with outsiders, viz., their Russian and Muslim neighbors. But, they continued to refer to themselves by their tribal, clan, or other internal affiliations.

The name Kalmyk, however, wasn't immediately accepted by all of the Oirat tribes in the lower Volga region. As late as 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars (refugees from the Manchu Empire) referred to themselves and the Torghuts exclusively as Oirats. The Torghuts, by contrast, used the name Kalmyk for themselves as well as the Khoshut and Dzungars. (Khodarkovsky, 1992:8)

Generally, European scholars have identified all western Mongolians collectively as Kalmyks, regardless of their location ( Ramstedt, 1935: v–vi). Such scholars (e.g. Sebastian Muenster) have relied on Muslim sources who traditionally used the word "Kalmyk" to describe western Mongolians in a derogatory manner and the western Mongols of China and Mongolia have regarded that name as a term of abuse (Haslund, 1935:214–215). Instead, they use the name Oirat or they go by their respective tribal names, e.g., Khoshut, Dörbet, Choros, Torghut, Khoit, Bayid, Mingat, etc. (Anuchin, 1914:57).

Over time, the descendants of the Oirat migrants in the lower Volga region embraced the name "Kalmyk" irrespective of their locations, viz., Astrakhan, the Don Cossack region, Orenburg, Stavropol, the Terek and the Ural Mountains. Another generally accepted name is ''Ulan Zalata'' or the "red-buttoned ones" (Adelman, 1960:6).

By the early 18th century, there were approximately 300–350,000 Kalmyks and 15,000,000 Russians. After the death of Ayuka Khan in 1724, the political situation among the Kalmyks became unstable as various factions sought to be recognized as Khan. The Russian Empire also gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies, for instance, encouraged the establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures the Kalmyks used to roam and feed their livestock. In addition, the Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, thereby diluting his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. The

By the early 18th century, there were approximately 300–350,000 Kalmyks and 15,000,000 Russians. After the death of Ayuka Khan in 1724, the political situation among the Kalmyks became unstable as various factions sought to be recognized as Khan. The Russian Empire also gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies, for instance, encouraged the establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures the Kalmyks used to roam and feed their livestock. In addition, the Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, thereby diluting his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. The

(Mongolian) As C.D Barkman notes, "It is quite clear that the Torghuts had not intended to surrender the Chinese, but had hoped to lead an independent existence in Dzungaria." Ubashi sent 30,000 cavalry in the first year of the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) to gain weaponry before the migration. The 8th Dalai Lama was contacted to request his blessing and to set the date of departure. After consulting the astrological chart, he set a return date, but at the moment of departure, the weakening of the ice on the Volga River permitted only those Kalmyks (about 200,000 people) on the eastern bank to leave. Those 100,000–150,000 people on the western bank were forced to stay behind and Approximately five-sixths of the Torghut followed Ubashi Khan. Most of the Khoshut, Choros, and Khoid also accompanied the Torghut on their journey to Dzungaria. The Dörbet Oirat, in contrast, elected not to go at all.

Catherine the Great asked the Russian army, Bashkirs, and Kazakh Khanate to stop all migrants. Beset by Kazakh raids, thirst and starvation, approximately 85,000 Kalmyks died on their way to Dzungaria. After failing to stop the flight, Catherine abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was abolished. The highest native governing office remaining was the Vice-Khan, who also was recognized by the government as the highest ranking Kalmyk prince. By appointing the Vice-Khan, the Russian Empire was now permanently the decisive force in Kalmyk government and affairs.

After seven months of travel, only one-third (66,073) of the original group reached Balkhash Lake, the western border of Qing China. This migration became the topic of ''The Revolt of the Tartars'', by Thomas De Quincey.

The Qing shifted the Kalmyks to five different areas to prevent their revolt and influential leaders of the Kalmyks soon died. The migrant Kalmyks became known as Torghut in Qing China. The Torghut were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them.

Approximately five-sixths of the Torghut followed Ubashi Khan. Most of the Khoshut, Choros, and Khoid also accompanied the Torghut on their journey to Dzungaria. The Dörbet Oirat, in contrast, elected not to go at all.

Catherine the Great asked the Russian army, Bashkirs, and Kazakh Khanate to stop all migrants. Beset by Kazakh raids, thirst and starvation, approximately 85,000 Kalmyks died on their way to Dzungaria. After failing to stop the flight, Catherine abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was abolished. The highest native governing office remaining was the Vice-Khan, who also was recognized by the government as the highest ranking Kalmyk prince. By appointing the Vice-Khan, the Russian Empire was now permanently the decisive force in Kalmyk government and affairs.

After seven months of travel, only one-third (66,073) of the original group reached Balkhash Lake, the western border of Qing China. This migration became the topic of ''The Revolt of the Tartars'', by Thomas De Quincey.

The Qing shifted the Kalmyks to five different areas to prevent their revolt and influential leaders of the Kalmyks soon died. The migrant Kalmyks became known as Torghut in Qing China. The Torghut were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them.

Despite their great loss in population, the Torghut still remained numerically superior, dominating the Kalmyks. The other Kalmyks in Russia included Dörbet Oirats and Khoshut. Elements of the Choros and Khoit also were present but were too few in number to retain their ''ulus'' (tribal division) as independent administrative units. As a result, they were absorbed by the ulus of the larger tribes.

The factors that caused the 1771 exodus continued to trouble the remaining Kalmyks. In the wake of the exodus, the Torghuts joined the Cossack rebellion of Yemelyan Pugachev in hopes that he would restore the independence of the Kalmyks. After Pugachev's Rebellion was defeated, Catherine the Great transferred the office of the Vice-Khan from the Torghut tribe to the Dörbet, whose princes supposedly remained loyal to the government during the rebellion. Thus the Torghut were removed from their role as the hereditary leaders of the Kalmyk people. The Khoshut could not challenge this political arrangement due to their smaller population size.

The disruptions to Kalmyk society caused by the exodus and the Torghut participation in the Pugachev Rebellion precipitated a major realignment in Kalmyk tribal structure. The government divided the Kalmyks into three administrative units attached, according to their respective locations, to the district governments of Astrakhan, Stavropol and the Don and appointed a special Russian official bearing the title of "Guardian of the Kalmyk People" for purposes of administration. The government also resettled some small groups of Kalmyks along the Ural, Terek and Kuma rivers and in Siberia.

Despite their great loss in population, the Torghut still remained numerically superior, dominating the Kalmyks. The other Kalmyks in Russia included Dörbet Oirats and Khoshut. Elements of the Choros and Khoit also were present but were too few in number to retain their ''ulus'' (tribal division) as independent administrative units. As a result, they were absorbed by the ulus of the larger tribes.

The factors that caused the 1771 exodus continued to trouble the remaining Kalmyks. In the wake of the exodus, the Torghuts joined the Cossack rebellion of Yemelyan Pugachev in hopes that he would restore the independence of the Kalmyks. After Pugachev's Rebellion was defeated, Catherine the Great transferred the office of the Vice-Khan from the Torghut tribe to the Dörbet, whose princes supposedly remained loyal to the government during the rebellion. Thus the Torghut were removed from their role as the hereditary leaders of the Kalmyk people. The Khoshut could not challenge this political arrangement due to their smaller population size.

The disruptions to Kalmyk society caused by the exodus and the Torghut participation in the Pugachev Rebellion precipitated a major realignment in Kalmyk tribal structure. The government divided the Kalmyks into three administrative units attached, according to their respective locations, to the district governments of Astrakhan, Stavropol and the Don and appointed a special Russian official bearing the title of "Guardian of the Kalmyk People" for purposes of administration. The government also resettled some small groups of Kalmyks along the Ural, Terek and Kuma rivers and in Siberia.

The redistricting divided the now dominant Dörbet tribe into three separate administrative units. Those in the western

The redistricting divided the now dominant Dörbet tribe into three separate administrative units. Those in the western

Like most people in Russia, the Kalmyks greeted the

Like most people in Russia, the Kalmyks greeted the

(Mongolian) The Kalmyks revolted against Russia in 1926, 1930 and 1942–1943. In March 1927, Soviet deported 20,000 Kalmyks to Siberia, tundra and

Around half of (97–98,000) Kalmyk people deported to Siberia died before being allowed to return home in 1957. The government of the Soviet Union forbade teaching Kalmyk Oirat during the deportation. The Kalmyks' main purpose was to migrate to Mongolia. Under the Law of the Russian Federation of April 26, 1991, "On Rehabilitation of Exiled Peoples", repressions against Kalmyks and other peoples were qualified as an act of

Around half of (97–98,000) Kalmyk people deported to Siberia died before being allowed to return home in 1957. The government of the Soviet Union forbade teaching Kalmyk Oirat during the deportation. The Kalmyks' main purpose was to migrate to Mongolia. Under the Law of the Russian Federation of April 26, 1991, "On Rehabilitation of Exiled Peoples", repressions against Kalmyks and other peoples were qualified as an act of

Mongolians name Kalmyks as Halimag. It means "the people moving away". The verb "Halih" in Mongolian means leakage, seepage or overpour. So the name "Halimag" is given, because they were the people who leaked from Mongolians and Mongolian land.

The name "Kalmyk" is a word of Turkic origin that means "remnant" or "to remain". Turkic tribes may have used this name as early as the thirteenth century. Arab geographer Ibn al-Wardi is documented as the first person to use the term in referring to the Oirats in the fourteenth century (Khodarkovsky, 1992:5, ''citing'' Bretschneider, 1910:2:167). The

Mongolians name Kalmyks as Halimag. It means "the people moving away". The verb "Halih" in Mongolian means leakage, seepage or overpour. So the name "Halimag" is given, because they were the people who leaked from Mongolians and Mongolian land.

The name "Kalmyk" is a word of Turkic origin that means "remnant" or "to remain". Turkic tribes may have used this name as early as the thirteenth century. Arab geographer Ibn al-Wardi is documented as the first person to use the term in referring to the Oirats in the fourteenth century (Khodarkovsky, 1992:5, ''citing'' Bretschneider, 1910:2:167). The

The Kalmyks are the only inhabitants of

The Kalmyks are the only inhabitants of

''

''

Boris Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Galina Denisova, Sanj Khoyt, Marcin Wozniak, Tomasz Grzybowski and Ilya Zakharov. Y-chromosome diversity in the Kalmyks at the ethnical and tribal levels

* Loewenthal, Rudolf. ''THE KALMUKS AND OF THE KALMUK ASSR: A Case in the Treatment of Minorities in the Soviet Union'', External Research Paper No. 101, Office of Intelligence Research, Department of State, September 5, 1952. * * Pallas, Peter Simon. , 2 vols., St. Petersburg: Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1776. * Pelliot, Paul. ''Notes sur le Turkestan'', T'oung Pao, XXVII, 1930. * Poppe, Nicholas N. ''The Mongolian Language Handbook'', Center for Applied Linguistics, 1970. * Pozdneev, A.M. ''Kalmytskoe Verouchenie'', Entsiklopedicheskii Slovar Brokgauz-Efrona, XIV, St. Petersburg, 1914. * Riasanovsky, V.A. ''Customary Law of the Mongol Tribes (Mongols, Buriats, Kalmucks)'', Harbin, 1929 * Ulanov, Mergen; Badmaev, Valeriy and Holland, Edward. Buddhism and Kalmyk Secular Law in the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries, Inner Asia 19(2), 2017, pp. 297–314. URL: http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/22105018-12340092 * Williamson, ''H.N.H. FAREWELL TO THE DON: The Russian Revolution in the Journals of Brigadier H.N.H. Williamson'', John Harris, Editor, The John Day Company, New York, 1970. * ''Wang Jinglan, Shao Xingzhou, Cui Jing et al.'' Anthropological survey on the Mongolian Tuerhute tribe in He shuo county, Xinjiang Uigur autonomous region // Acta anthropologica sinica. Vol. XII, № 2. May, 1993. pp. 137–146. * * ''Санчиров В. П.'' О Происхождении этнонима торгут и народа, носившего это название // Монголо-бурятские этнонимы: cб. ст. – Улан-Удэ: БНЦ СО РАН, 1996. C. 31–50. * Galushkin S.K., Spitsyn V.A., Crawford M.H

Genetic Structure of Mongolic-speaking Kalmyks

// Human Biology, December 2001, v.73, no. 6, pp. 823–834. * Хойт С.К.

Генетическая структура европейских ойратских групп по локусам ABO, RH, HP, TF, GC, ACP1, PGM1, ESD, GLO1, SOD-A

' // Проблемы этнической истории и культуры тюрко-монгольских народов. Сборник научных трудов. Вып. I. Элиста: КИГИ РАН, 2009. с. 146–183. * Хойт С.К. '' amagmongol.narod.ru/library/khoyt_2008_r.htm Антропологические характеристики калмыков по данным исследователей XVIII–XIX вв.' // Вестник Прикаспия: археология, история, этнография. № 1. Элиста: Изд-во КГУ, 2008. с. 220–243. * Хойт С.К. '' amagmongol.narod.ru/library/khoyt_2012_r.htm Калмыки в работах антропологов первой половины XX вв'. // Вестник Прикаспия: археология, история, этнография. № 3, 2012. с. 215–245. * Хойт С.К.

Этническая история ойратских групп

'. Элиста, 2015. 199 с. (Khoyt S.K. Ethnic history of oyirad groups. Elista, 2015. 199 p). (in Russian) * Хойт С.К.

Данные фольклора для изучения путей этногенеза ойратских групп

' // Международная научная конференция «Сетевое востоковедение: образование, наука, культура», 7-10 декабря 2017 г.: материалы. Элиста: Изд-во Калм. ун-та, 2017. с. 286–289.

The Construction of a Yurt

"Carte de Tartarie," by Guillaume de L'Isle (1675–1726). From the Map Collection of the Library of Congress

* Kalmyk-Oirat: A Language of Russia (Europe)

BBC News Regions and Territories: Kalmykia

* Kalmyk-Oirat: A Language of China * Kalmyk-Oirat: A Language of Mongolia

Prayer Profile: The Kalmyk of Russia

Kalmyk. (2006). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 7, 2006.

* ttp://bumbinorn.ru/2006/02/03/tragedija_velikojj_stepi.html Трагедия Великой Степи (Tragedy of Great Steppe)

Genetic Evidence for the Mongolian Ancestry of Kalmyks, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 126 (2005)

ibid., p7.

* ttps://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9362647?query=hat&ct= Dge-lugs-pa. (2006). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 6, 2006.

Tibetan Buddhism. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05. Retrieved March 6, 2006.

History of Buddhism in West Turkistan

Europe's biggest Buddhist temple opens in Kalmykia

Linguistic Lineage for Kalmyk-Oirat

Kalmyk News Agency

The proof of business life of Kalmykia

Norsk Utenrikspolitisk Institutt (NUPI)'s Centre for Russian Studies Kalmykiya page

Kalmyk Buddhist Temple in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (1929–1944)

US Library of Congress Country Studies: Russia, The North Caucasus

Web-Portal of the Interregional Not-for-Profit Organization "The Leaders of Kalmykia"

Kalmyk Brotherhood Society, Philadelphia, PA

Kalmyk American Society

Kalmuck Mongolian Buddhist Center, Howell, NJ

Kalmyk tales in Kalmyk language

* Kalmyk names {{DEFAULTSORT:Kalmyk People Ethnic groups in Kyrgyzstan Kalmyk people Buddhism in Russia Mongol diaspora in Europe Ethnic groups in Russia

anglicised

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

as ''Calmucks'') are a Mongolic ethnic group living mainly in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, whose ancestors migrated from Dzungaria. They created the Kalmyk Khanate

The Kalmyk Khanate ( xal-RU, Хальмг хана улс, ''Xal'mg xana uls'') was an Oirat khanate on the Eurasian steppe. It extended over modern Kalmykia and surrounding areas in the North Caucasus, including Stavropol and Astrakhan. Duri ...

from 1635 to 1779 in Russia's North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

territory. Today they form a majority in Kalmykia

he official languages of the Republic of Kalmykia are the Kalmyk and Russian languages./ref>

, official_lang_list= Kalmyk

, official_lang_ref=Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia, Article 17: he official languages of the ...

, located in the Kalmyk Steppe

Kalmuk Steppe, or Kalmyk Steppe is a steppe with a land area of approximately 100,000 km², bordering the northwest Caspian Sea, bounded by the Volga on the northeast, the Manych on the southwest, and the territory of the Don Cossacks on the nor ...

, on the western shore of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

.

They are the only traditionally Buddhist people whose homeland is located within Europe. Through emigration, small Kalmyk communities have been established in the United States, France, Germany, and the Czech Republic.

Origins and history

Early history of the Oirats

The Kalmyk are a branch of theOirat Mongols

Oirats ( mn, Ойрад, ''Oirad'', or , Oird; xal-RU, Өөрд; zh, 瓦剌; in the past, also Eleuths) are the westernmost group of the Mongols whose ancestral home is in the Altai region of Siberia, Xinjiang and western Mongolia.

Histor ...

, whose ancient grazing-lands spanned present-day parts of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

. After the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

of China in 1368, the Oirats emerged as a formidable foe against the Khalkha Mongols

The Khalkha ( Mongolian: mn, Халх, Halh, , zh, 喀爾喀) have been the largest subgroup of Mongol people in modern Mongolia since the 15th century. The Khalkha, together with Chahars, Ordos and Tumed, were directly ruled by Borjigin kha ...

, the Chinese Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

(1368–1644) and the Manchus who founded the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in China in 1644. For 400 years, the Oirats conducted a military struggle for domination and control over both Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

and Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gain ...

. The struggle ended in 1757 with the defeat of the Oirats in Dzungaria; they were the last of the Mongol groups to resist vassalage to Qing (Grousset, 1970: 502–541).

At the start of this 400-year era, the Western Mongols designated themselves as the Four Oirat

The Four Oirat ( Mongolian: Дөрвөн Ойрад, ''Dorben Oirad''; ); also Oirads and formerly Eleuths, alternatively known as the Alliance of the Four Oirat Tribes or the Oirat Confederation, was the confederation of the Oirat tribes which ...

. The alliance comprised four major Western Mongol tribes: Khoshut, Choros, Torghut and Dörbet. Collectively, the Four Oirat sought power as an alternative to the Mongols, who were the patrilineal heirs to Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; ; xng, Temüjin, script=Latn; ., name=Temujin – August 25, 1227) was the founder and first Great Khan (Emperor) of the Mongol Empire, which became the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in history a ...

. The Four Oirat incorporated neighboring tribes or splinter groups at times, so there was a great deal of fluctuation in the composition of the alliance, with larger tribes dominating or absorbing the smaller ones. Smaller tribes belonging to the confederation included the Khoits, Zakhchin, Bayids And Khangal.

Together, these nomadic tribes roamed the grassy plains of western Inner Asia, between Lake Balkhash in present-day eastern

Together, these nomadic tribes roamed the grassy plains of western Inner Asia, between Lake Balkhash in present-day eastern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

and Lake Baikal in present-day Russia north of central Mongolia. They pitched their yurts and kept herds of cattle, flocks of sheep, horses, donkeys and camels.

Paul Pelliot translated the name "Torghut" as ''garde de jour''. He wrote that the Torghuts owed their name either to the memory of the guard of Genghis Khan or, as descendants of the Keraites

The Keraites (also ''Kerait, Kereit, Khereid''; ; ) were one of the five dominant Mongol or Turkic tribal confederations ( khanates) in the Altai-Sayan region during the 12th century. They had converted to the Church of the East ( Nestorianism) ...

, to the old ''garde de jour''. This was documented among the Keraites in '' The Secret History of the Mongols'' before Genghis Khan took over the region (Pelliot, 1930:30).

Period of open conflict

The ''Four Oirat'' was a political entity formed by the four major Oirat tribes. During the 15–17th centuries, they established under the name "10 tumen Mongols", a cavalry unit of 10,000 horsemen, including four Oirat tumen and six tumen composed of other Mongols. They reestablished their traditional pastoral nomadic lifestyle during the end of the Yuan dynasty. The Oirats formed this alliance to defend themselves against the Khalkha Mongols and to pursue the greater objective of reunifying Mongolia. Until the mid-17th century, when bestowal of the title of Khan was transferred to theDalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current D ...

, all Mongol tribes recognized this claim and the political prestige attached to it. Although the Oirats could not assert this claim prior to the mid-17th century, they did in fact have a close connection to Genghis Khan by virtue of the fact that Genghis Khan's brother, Qasar, was in command of the Khoshut tribe.

In response to the Western Mongols' self-designation as the Four Oirat, the Eastern Mongols began to refer to themselves as the "Forty Mongols", or the "Forty and Four". This means that the Khalkha Mongols claimed to have forty tümen to the four tümen maintained by the Four Oirat.

The Oirat alliance was decentralized, informal and unstable. For instance, the Four Oirat did not have a central location from which it was governed, and it was not governed by a central figure for most of its existence. The four Oirats did not establish a single military or a unified monastic system. Lastly, it was not until 1640 that the Four Oirat adopted uniform customary laws.

As pastoralist nomads, the Oirats were organized at the tribal level, where each tribe was ruled by a ''noyon'' or prince who also functioned as the chief ''taishi'' "chieftain". The chief taishi governed with the support of lesser noyons, who were also called taishi. These minor noyons controlled divisions of the tribe (''ulus'') and were politically and economically independent of the chief tayishi. Chief taishis sought to influence and dominate the chief taishis of the other tribes, causing intertribal rivalry, dissension and periodic skirmishes.

Under the leadership of Esen, Chief Taishi of the Choros, the Four Oirat unified Mongolia for a short period. After Esen's death in 1455, the political union of the Dörben Oirat dissolved quickly, resulting in two decades of Oirat-Eastern Mongol conflict. The deadlock ended during the reign of Batmunkh Dayan Khan, a five-year-old boy in whose name the loyal Eastern Mongol forces rallied. Mandukhai Khatun and Dayan Khan took advantage of Oirat disunity and weakness and brought Oirats back under Mongolian rule. In doing so, he regained control of the Mongol homeland and restored the hegemony of the Eastern Mongols.

After the death of Dayan in 1543, the Oirats and the Khalkhas resumed their conflict. The Oirat forces thrust eastward, but Dayan's youngest son, Geresenz, was given command of the Khalkha forces and drove the Oirats to Uvs Lake

Uvs Lake ( mn, Увс нуур, Uws nuur, ; russian: Озеро Убсу-Нур, Ozero Ubsu-Nur; zh, 乌布苏湖, wū bù sū hú, pinyin: ''Wū Bù Sū hú'') is a highly saline lake in an endorheic basin— Uvs Nuur Basin in Mongolia with a ...

in northwest Mongolia. In 1552, after the Oirats once again challenged the Khalkha, Altan Khan swept up from Inner Mongolia with Tümed and Ordos cavalry units, pushing elements of various Oirat tribes from Karakorum

Karakorum ( Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian Script:, ''Qaraqorum''; ) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in t ...

to the Khovd region in northwest Mongolia, reuniting most of Mongolia in the process (Grousset, 1970:510).

The Oirats would later regroup south of the Altai Mountains in Dzungaria. But Geresenz's grandson, Sholoi Ubashi Khuntaiji, pushed the Oirats further northwest, along the steppes of the Ob and Irtysh Rivers. Afterwards, he established a Khalkha Khanate under the name, Altan Khan, in the Oirat heartland of Dzungaria.

In spite of the setbacks, the Oirats would continue their campaigns against the Altan Khanate, trying to unseat Sholoi Ubashi Khuntaiji from Dzungaria. The continuous, back-and-forth nature of the struggle, which defined this period, is captured in the Oirat epic song "The Rout of Mongolian Sholoi Ubashi Khuntaiji", recounting the Oirat victory over the Altan Khan of the Khalkha

The Altan Khans (lit. Golden Khan) ruled north-western Mongolia from about 1609 to 1691 at the latest. Altan Khan of Khalkha also known as Altan Khan of Khotogoid ruled over the Khotogoids in northwestern Mongolia and belonged to the Left Wing of ...

in 1587.

Resurgence of Oirat power

At the beginning of the 17th century, the First Altan Khan drove the

At the beginning of the 17th century, the First Altan Khan drove the Oirats

Oirats ( mn, Ойрад, ''Oirad'', or , Oird; xal-RU, Өөрд; zh, 瓦剌; in the past, also Eleuths) are the westernmost group of the Mongols whose ancestral home is in the Altai region of Siberia, Xinjiang and western Mongolia.

Histor ...

westward to present-day eastern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

. The Torghuts became the westernmost Oirat tribe, encamped in the Tarbagatai Mountains region and along the northern stretches of the Irtysh, Ishim and Tobol Rivers.

Further west, the Kazakhs

The Kazakhs (also spelled Qazaqs; Kazakh: , , , , , ; the English name is transliterated from Russian; russian: казахи) are a Turkic-speaking ethnic group native to northern parts of Central Asia, chiefly Kazakhstan, but also part ...

– a Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Turco-Mongol people – prevented the Torghuts from sending its trading caravans to the Muslim towns and villages located along the Syr Darya

The Syr Darya (, ),, , ; rus, Сырдарья́, Syrdarjja, p=sɨrdɐˈrʲja; fa, سيردريا, Sirdaryâ; tg, Сирдарё, Sirdaryo; tr, Seyhun, Siri Derya; ar, سيحون, Seyḥūn; uz, Sirdaryo, script-Latn/. historically known ...

river. As a result, the Torghuts established a trading relationship with the newly established outposts of the Tsarist government whose expansion into and exploration of Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

was motivated mostly by the desire to profit from trade with Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

.

The Khoshut, by contrast, were the easternmost Oirat, encamped near the Lake Zaysan area and the Semey

Semey ( kk, Семей, Semei, سەمەي; cyrl, Семей ), until 2007 known as Semipalatinsk (russian: Семипала́тинск) and in 1917–1920 as Alash-kala ( kk, Алаш-қала, ''Alaş-qala''), is a city in eastern Kazakhs ...

region along the lower portions of the Irtysh River, where they built several steppe monasteries. The Khoshut were adjacent to the Khalkha khanates of Altan Khan and Dzasagtu Khan. Both khanates prevented the Khoshut and the other Oirat from trading with Chinese border towns. The Khoshut were ruled by Baibagas Khan and then Güshi Khan, who were the first Oirat leaders to convert to the Gelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).">Bodh_Gaya.html" ;"title="Kalachakra ceremony, Bodh Gaya">Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuou ...

school of Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

.

Locked in between both tribes were the Choros, Dörbet Oirat

The Dörbet ( xal-RU, Дөрвд, ''Dörwyd''; mn, Дөрвөд, ''Dörvöd'', lit. ''"the Fours"''; ; also known in English as the ''Derbet'') is the second largest subgroup of Mongol people in modern Mongolia and was formerly one of the major t ...

and Khoid

The Khoid, also Khoyd or Khoit (; "Northern ones/people") people are an Oirat subgroup of the Choros Choros may refer to:

* Choros (Oirats), a Mongolic people and historical clan

* Chôros, a series of compositions by Heitor Villa-Lobos

* Choros ...

, collectively known as the " Dzungar people", who were slowly rebuilding the base of power they enjoyed under the Four Oirat. The Choros were the dominant Oirat tribe of that era. Their leader, Erdeni Batur, attempted to follow Esen Khan in unifying the Oirats to challenge the Khalkha.

Under the dynamic leadership of Erdeni Batur, the Dzungars stopped the expansion of the first Altan Khan and began planning the resurrection of the Four Oirat under the Dzungar banner. In furtherance of such plans, Erdeni Batur designed and built a capital city called Kubak-sari on the

Under the dynamic leadership of Erdeni Batur, the Dzungars stopped the expansion of the first Altan Khan and began planning the resurrection of the Four Oirat under the Dzungar banner. In furtherance of such plans, Erdeni Batur designed and built a capital city called Kubak-sari on the Emil River

The Emil ( kz, Еміл, ''Emıl''; russian: Эмель ''Emel'') or Emin (), also spelled Emel, Imil, etc., is a river in China and Kazakhstan. It flows through Tacheng (Tarbagatay) Prefecture of China's Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region and the ...

near the modern city of Tacheng

TachengThe official spelling according to (), as the official romanized name, also transliterated from Mongolian as Qoqak, is a county-level city (1994 est. pop. 56,400) and the administrative seat of Tacheng Prefecture, in northern Ili Kazakh A ...

. During his attempt to build a nation, Erdeni Batur encouraged diplomacy, commerce and farming. He also sought to acquire modern weaponry and build small industry, such as metal works, to supply his military.weapons.

The attempted unification of the Oirat caused dissension among the tribes and their Chief Tayishis who were independent minded but also highly regarded leaders themselves. This dissension reputedly caused Kho Orluk to move the Torghut tribe and elements of the Dörbet tribe westward to the Volga region where his descendants formed the Kalmyk Khanate. In the east, Güshi Khan took part of the Khoshut to the Tsaidam and Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

regions in the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

, where he formed the Khoshut Khanate to protect Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

and the Gelug from both internal and external enemies. Erdeni Batur and his descendants, by contrast, formed the Dzungar Khanate and came to dominate Central Eurasia.

Torghut migration

In 1618, the Torghut and a small contingent of Dörbet Oirats (200,000–250,000 people) chose to migrate from the upper Irtysh River region to the grazing pastures of the lower Volga region south ofSaratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901, ...

and north of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

on both banks of the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

. The Torghut were led by their taishi, Kho Orluk

Kho Orluk ( mn, Хо Өрлөг; died 1644) was an Oirat prince and Taish of the Torghut- Oirat tribe. Around 1616, Kho Orluk persuaded the other Torghut princes and lesser nobility to move their tribe en masse westward through southern Siberia a ...

. They were the largest Oirat tribe to migrate, bringing along nearly the entire tribe. The second-largest group was the Dörbet Oirats under their taishi, Dalai Batur. Together they moved west through southern Siberia and the southern Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

, avoiding the more direct route that would have taken them through the heart of the territory of their enemy, the Kazakhs. En route, they raided Russian settlements and Kazakh and Bashkir encampments.

Many theories have been advanced to explain the reasons for the migration. One generally accepted theory is that there may have been discontent among the Oirat tribes, which arose from the attempt by Kharkhul, taishi of the Dzungars, to centralize political and military control over the tribes under his leadership. Some scholars, however, believe that the Torghuts sought uncontested pastures as their territory was being encroached upon by the Russians from the north, the Kazakhs from the south and the Dzungars from the east. The encroachments resulted in overcrowding of people and livestock, thereby diminishing the food supply. Lastly, a third theory suggests that the Torghuts grew weary of the militant struggle between the Oirats and the Altan Khanate.

Kalmyk Khanate

Period of self rule, 1630–1724

Upon arrival to the lower Volga region in 1630, the Oirats encamped on land that was once part of the Astrakhan Khanate, but was now claimed by the

Upon arrival to the lower Volga region in 1630, the Oirats encamped on land that was once part of the Astrakhan Khanate, but was now claimed by the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I ...

. The region was lightly populated, from south of Saratov to the Russian garrison at Astrakhan and on both the east and the west banks of the Volga River. The Tsardom of Russia was not ready to colonize the area and was in no position to prevent the Oirats from encamping in the region, but it had a direct political interest in ensuring that the Oirats would not become allied with its Turkic-speaking neighbors. The Kalmyks became Russian allies and a treaty to protect the southern Russian border was signed between the Kalmyk Khanate and Russia.

The Oirats quickly consolidated their position by expelling the majority of the native inhabitants, the Nogai Horde. Large groups of Nogais fled southeast to the northern Caucasian plain and west to the Black Sea steppe, lands claimed by the Crimean Khanate, itself a vassal or ally of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. Smaller groups of Nogais sought the protection of the Russian garrison at Astrakhan. The remaining nomadic tribes became vassals of the Oirats.

The Kalmyks battled the Karakalpaks. The Mangyshlak Peninsula was overtaken in 1639 by Kalmyks.

At first, an uneasy relationship existed between the Russians and the Oirats. Mutual raiding by the Oirats of Russian settlements and by the Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

and the Bashkirs, Muslim vassals of the Russians, of Oirat encampments was commonplace. Numerous oaths and treaties were signed to ensure Oirat loyalty and military assistance. Although the Oirats became subjects of the Tsar, such allegiance by the Oirats was deemed to be nominal.

In reality, the Oirats governed themselves pursuant to a document known as the "Great Code of the Nomads" (''Iki Tsaadzhin Bichig''). The Code was promulgated in 1640 by them, their brethren in Dzungaria and some of the Khalkha who all gathered near the Tarbagatai Mountains in Dzungaria to resolve their differences and to unite under the banner of the Gelug school. Although the goal of unification was not met, the summit leaders did ratify the Code, which regulated all aspects of nomadic life.

In securing their position, the Oirats became a borderland power, often allying themselves with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

against the neighboring Muslim population. During the era of Ayuka Khan, the Oirats rose to political and military prominence as the Russian Empire sought the increased use of Oirat cavalry in support of its military campaigns against the Muslim powers in the south, such as Safavid Iran

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

, the Ottoman Empire, the Nogais, the Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Turki ...

of Kuban and the Crimean Khanate. Ayuka Khan also waged wars against the Kazakhs, subjugated the in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Turki ...

Turkmens

Turkmens ( tk, , , , ; historically "the Turkmen"), sometimes referred to as Turkmen Turks ( tk, , ), are a Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, living mainly in Turkmenistan, northern and northeastern regions of Iran and north-weste ...

of the Mangyshlak Peninsula, and made multiple expeditions against the highlanders of the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

. These campaigns highlighted the strategic importance of the Kalmyk Khanate which functioned as a buffer zone, separating Russia and the Muslim world, as Russia fought wars in Europe to establish itself as a European power.

To encourage the release of Oirat cavalrymen in support of its military campaigns, the Russian Empire increasingly relied on the provision of monetary payments and dry goods to the Oirat Khan and the Oirat nobility. In that respect, the Russian Empire treated the Oirats as it did the Cossacks. The provision of monetary payments and dry goods, however, did not stop the mutual raiding, and, in some instances, both sides failed to fulfill its promises (Halkovic, 1985:41–54).

Another significant incentive the Russian Empire provided to the Oirats was tariff-free access to the markets of Russian border towns, where the Oirats were permitted to barter their herds and the items they obtained from Asia and their Muslim neighbors in exchange for Russian goods. Trade also occurred with neighboring Turkic tribes under Russian control, such as the Tatars and the Bashkirs. Intermarriage became common with such tribes. This trading arrangement provided substantial benefits, monetary and otherwise, to the Oirat tayishis, noyons and zaisangs.

Fred Adelman described this era as the "Frontier Period", lasting from the advent of the Torghut under Kho Orluk in 1630 to the end of the great khanate of Kho Orluk's descendant, Ayuka Khan, in 1724, a phase accompanied by little discernible acculturative change:

During the era of Ayuka Khan, the Kalmyk Khanate reached its peak of military and political power. The Khanate experienced economic prosperity from free trade with Russian border towns, China, Tibet and with their Muslim neighbors. During this era, Ayuka Khan also kept close contacts with his Oirat kinsmen in Dzungaria, as well as the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

From Oirat to Kalmyk

Historically, Oirat identified themselves by their respective sub-group names. In the 15th century, the three major groups of Oirat formed an alliance, adopting "Dörben Oirat" as their collective name. In the early 17th century, a second great Oirat Confederation emerged, which later became the Dzungar Empire. While the Dzungars (initially Choros, Dörbet and Khoit tribes) were establishing their empire in Central Eurasia, the Khoshuts were establishing the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet, protecting the Gelugpa sect from its enemies, and the Torghuts formed the Kalmyk Khanate in the lower Volga region.

After encamping, the Oirats began to identify themselves as "Kalmyk." This named was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians to describe them. The Oirats used this name in their dealings with outsiders, viz., their Russian and Muslim neighbors. But, they continued to refer to themselves by their tribal, clan, or other internal affiliations.

The name Kalmyk, however, wasn't immediately accepted by all of the Oirat tribes in the lower Volga region. As late as 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars (refugees from the Manchu Empire) referred to themselves and the Torghuts exclusively as Oirats. The Torghuts, by contrast, used the name Kalmyk for themselves as well as the Khoshut and Dzungars. (Khodarkovsky, 1992:8)

Generally, European scholars have identified all western Mongolians collectively as Kalmyks, regardless of their location ( Ramstedt, 1935: v–vi). Such scholars (e.g. Sebastian Muenster) have relied on Muslim sources who traditionally used the word "Kalmyk" to describe western Mongolians in a derogatory manner and the western Mongols of China and Mongolia have regarded that name as a term of abuse (Haslund, 1935:214–215). Instead, they use the name Oirat or they go by their respective tribal names, e.g., Khoshut, Dörbet, Choros, Torghut, Khoit, Bayid, Mingat, etc. (Anuchin, 1914:57).

Over time, the descendants of the Oirat migrants in the lower Volga region embraced the name "Kalmyk" irrespective of their locations, viz., Astrakhan, the Don Cossack region, Orenburg, Stavropol, the Terek and the Ural Mountains. Another generally accepted name is ''Ulan Zalata'' or the "red-buttoned ones" (Adelman, 1960:6).

Historically, Oirat identified themselves by their respective sub-group names. In the 15th century, the three major groups of Oirat formed an alliance, adopting "Dörben Oirat" as their collective name. In the early 17th century, a second great Oirat Confederation emerged, which later became the Dzungar Empire. While the Dzungars (initially Choros, Dörbet and Khoit tribes) were establishing their empire in Central Eurasia, the Khoshuts were establishing the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet, protecting the Gelugpa sect from its enemies, and the Torghuts formed the Kalmyk Khanate in the lower Volga region.

After encamping, the Oirats began to identify themselves as "Kalmyk." This named was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians to describe them. The Oirats used this name in their dealings with outsiders, viz., their Russian and Muslim neighbors. But, they continued to refer to themselves by their tribal, clan, or other internal affiliations.

The name Kalmyk, however, wasn't immediately accepted by all of the Oirat tribes in the lower Volga region. As late as 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars (refugees from the Manchu Empire) referred to themselves and the Torghuts exclusively as Oirats. The Torghuts, by contrast, used the name Kalmyk for themselves as well as the Khoshut and Dzungars. (Khodarkovsky, 1992:8)

Generally, European scholars have identified all western Mongolians collectively as Kalmyks, regardless of their location ( Ramstedt, 1935: v–vi). Such scholars (e.g. Sebastian Muenster) have relied on Muslim sources who traditionally used the word "Kalmyk" to describe western Mongolians in a derogatory manner and the western Mongols of China and Mongolia have regarded that name as a term of abuse (Haslund, 1935:214–215). Instead, they use the name Oirat or they go by their respective tribal names, e.g., Khoshut, Dörbet, Choros, Torghut, Khoit, Bayid, Mingat, etc. (Anuchin, 1914:57).

Over time, the descendants of the Oirat migrants in the lower Volga region embraced the name "Kalmyk" irrespective of their locations, viz., Astrakhan, the Don Cossack region, Orenburg, Stavropol, the Terek and the Ural Mountains. Another generally accepted name is ''Ulan Zalata'' or the "red-buttoned ones" (Adelman, 1960:6).

Reduction in autonomy, 1724–1771

Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

, by contrast, pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Eastern Orthodoxy. By the mid-18th century, Kalmyks were increasingly disillusioned with settler encroachment and interference in its internal affairs.

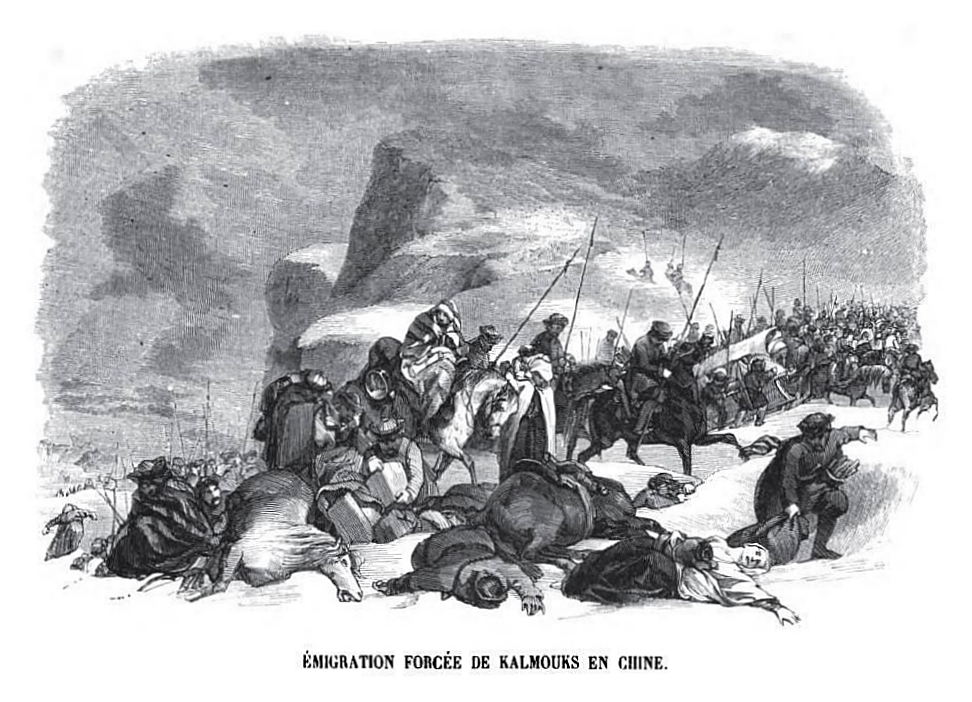

In January 1771 the oppression of Tsarist administration forced the larger part of Kalmyks (33 thousand households, or approximately 170,000–200,000 people) to migrate to Dzungaria.

Ubashi Khan, the great-grandson of Ayuka Khan and the last Kalmyk Khan, decided to return his people to their ancestral homeland, Dzungaria, and restore the Dzungar Khanate and Mongolian independence.ТИВ ДАМНАСАН НҮҮДЭЛ(Mongolian) As C.D Barkman notes, "It is quite clear that the Torghuts had not intended to surrender the Chinese, but had hoped to lead an independent existence in Dzungaria." Ubashi sent 30,000 cavalry in the first year of the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) to gain weaponry before the migration. The 8th Dalai Lama was contacted to request his blessing and to set the date of departure. After consulting the astrological chart, he set a return date, but at the moment of departure, the weakening of the ice on the Volga River permitted only those Kalmyks (about 200,000 people) on the eastern bank to leave. Those 100,000–150,000 people on the western bank were forced to stay behind and

Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

executed influential nobles from among them.

Approximately five-sixths of the Torghut followed Ubashi Khan. Most of the Khoshut, Choros, and Khoid also accompanied the Torghut on their journey to Dzungaria. The Dörbet Oirat, in contrast, elected not to go at all.

Catherine the Great asked the Russian army, Bashkirs, and Kazakh Khanate to stop all migrants. Beset by Kazakh raids, thirst and starvation, approximately 85,000 Kalmyks died on their way to Dzungaria. After failing to stop the flight, Catherine abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was abolished. The highest native governing office remaining was the Vice-Khan, who also was recognized by the government as the highest ranking Kalmyk prince. By appointing the Vice-Khan, the Russian Empire was now permanently the decisive force in Kalmyk government and affairs.

After seven months of travel, only one-third (66,073) of the original group reached Balkhash Lake, the western border of Qing China. This migration became the topic of ''The Revolt of the Tartars'', by Thomas De Quincey.

The Qing shifted the Kalmyks to five different areas to prevent their revolt and influential leaders of the Kalmyks soon died. The migrant Kalmyks became known as Torghut in Qing China. The Torghut were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them.

Approximately five-sixths of the Torghut followed Ubashi Khan. Most of the Khoshut, Choros, and Khoid also accompanied the Torghut on their journey to Dzungaria. The Dörbet Oirat, in contrast, elected not to go at all.

Catherine the Great asked the Russian army, Bashkirs, and Kazakh Khanate to stop all migrants. Beset by Kazakh raids, thirst and starvation, approximately 85,000 Kalmyks died on their way to Dzungaria. After failing to stop the flight, Catherine abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was abolished. The highest native governing office remaining was the Vice-Khan, who also was recognized by the government as the highest ranking Kalmyk prince. By appointing the Vice-Khan, the Russian Empire was now permanently the decisive force in Kalmyk government and affairs.

After seven months of travel, only one-third (66,073) of the original group reached Balkhash Lake, the western border of Qing China. This migration became the topic of ''The Revolt of the Tartars'', by Thomas De Quincey.

The Qing shifted the Kalmyks to five different areas to prevent their revolt and influential leaders of the Kalmyks soon died. The migrant Kalmyks became known as Torghut in Qing China. The Torghut were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them.

Life in the Russian Empire

After the 1771 exodus, the Kalmyks that remained part of the Russian Empire continued their nomadic pastoral lifestyle, ranging the pastures between the Don and the Volga Rivers, wintering in the lowlands along the shores of the Caspian Sea as far asSarpa Lake

Sarpa Lake (russian: Сарпа́) is a lake of Kalmykia

he official languages of the Republic of Kalmykia are the Kalmyk and Russian languages./ref>

, official_lang_list= Kalmyk

, official_lang_ref=Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic o ...

to the northwest and Lake Manych-Gudilo to the west. In the spring, they moved along the Don River and the Sarpa lake system, attaining the higher grounds along the Don in the summer, passing the autumn in the Sarpa and Volga lowlands. In October and November they returned to their winter camps and pastures (Krader, 1963:121 ''citing'' Pallas, vol. 1, 1776:122–123).

Despite their great loss in population, the Torghut still remained numerically superior, dominating the Kalmyks. The other Kalmyks in Russia included Dörbet Oirats and Khoshut. Elements of the Choros and Khoit also were present but were too few in number to retain their ''ulus'' (tribal division) as independent administrative units. As a result, they were absorbed by the ulus of the larger tribes.

The factors that caused the 1771 exodus continued to trouble the remaining Kalmyks. In the wake of the exodus, the Torghuts joined the Cossack rebellion of Yemelyan Pugachev in hopes that he would restore the independence of the Kalmyks. After Pugachev's Rebellion was defeated, Catherine the Great transferred the office of the Vice-Khan from the Torghut tribe to the Dörbet, whose princes supposedly remained loyal to the government during the rebellion. Thus the Torghut were removed from their role as the hereditary leaders of the Kalmyk people. The Khoshut could not challenge this political arrangement due to their smaller population size.

The disruptions to Kalmyk society caused by the exodus and the Torghut participation in the Pugachev Rebellion precipitated a major realignment in Kalmyk tribal structure. The government divided the Kalmyks into three administrative units attached, according to their respective locations, to the district governments of Astrakhan, Stavropol and the Don and appointed a special Russian official bearing the title of "Guardian of the Kalmyk People" for purposes of administration. The government also resettled some small groups of Kalmyks along the Ural, Terek and Kuma rivers and in Siberia.

Despite their great loss in population, the Torghut still remained numerically superior, dominating the Kalmyks. The other Kalmyks in Russia included Dörbet Oirats and Khoshut. Elements of the Choros and Khoit also were present but were too few in number to retain their ''ulus'' (tribal division) as independent administrative units. As a result, they were absorbed by the ulus of the larger tribes.

The factors that caused the 1771 exodus continued to trouble the remaining Kalmyks. In the wake of the exodus, the Torghuts joined the Cossack rebellion of Yemelyan Pugachev in hopes that he would restore the independence of the Kalmyks. After Pugachev's Rebellion was defeated, Catherine the Great transferred the office of the Vice-Khan from the Torghut tribe to the Dörbet, whose princes supposedly remained loyal to the government during the rebellion. Thus the Torghut were removed from their role as the hereditary leaders of the Kalmyk people. The Khoshut could not challenge this political arrangement due to their smaller population size.

The disruptions to Kalmyk society caused by the exodus and the Torghut participation in the Pugachev Rebellion precipitated a major realignment in Kalmyk tribal structure. The government divided the Kalmyks into three administrative units attached, according to their respective locations, to the district governments of Astrakhan, Stavropol and the Don and appointed a special Russian official bearing the title of "Guardian of the Kalmyk People" for purposes of administration. The government also resettled some small groups of Kalmyks along the Ural, Terek and Kuma rivers and in Siberia.

The redistricting divided the now dominant Dörbet tribe into three separate administrative units. Those in the western

The redistricting divided the now dominant Dörbet tribe into three separate administrative units. Those in the western Kalmyk Steppe

Kalmuk Steppe, or Kalmyk Steppe is a steppe with a land area of approximately 100,000 km², bordering the northwest Caspian Sea, bounded by the Volga on the northeast, the Manych on the southwest, and the territory of the Don Cossacks on the nor ...

were attached to the Astrakhan district government. They were called Baga (Lesser) Dörbet. By contrast, the Dörbets who moved to the northern part of the Stavropol province were called Ike (Greater) Dörbet even though their population was smaller. Finally, the Kalmyks of the Don became known as Buzava. Although they were composed of elements of all the Kalmyk tribes, the Buzava claimed descent from the Torghut tribe. Their name is derived from two tributaries of the Don River: Busgai and Busuluk. In 1798, Tsar Paul I recognized the Don Kalmyks as Don Cossacks. As such, they received the same rights and benefits as their Russian counterparts in exchange for providing national military services (Bajanowa, 1976:68–71). At the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, Kalmyk cavalry units in Russian service entered Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

.

Over time, the Kalmyks gradually created fixed settlements with houses and temples, in place of transportable round felt yurts. In 1865, Elista

Elista (russian: Элиста́, (common during the Soviet era) or (most common pronunciation used after 1992 and in Kalmykia itself);"Большой энциклопедический словарь", под ред. А. М. Прохорова. ...

, the future capital of the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

The Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (russian: Калмыцкая Автономная Советская Социалистическая Республика; xal-RU, Хальмг Автономн Советск Социалисти� ...

was founded. This process lasted until well after the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

of 1917.

Russian Revolution and Civil War

Like most people in Russia, the Kalmyks greeted the

Like most people in Russia, the Kalmyks greeted the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

with enthusiasm. Kalmyk leaders believed that the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

, which replaced the Tsarist government, would allow greater autonomy and freedom with respect to their culture, religion and economy. This enthusiasm, however, would soon dissolve after the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

took control of the national government during the second revolution in November 1917.

After the Bolsheviks took control, various political and ethnic groups opposed to Communism organized in a loose political and military coalition known as the White movement. A volunteer "White Army" was raised to fight the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, the military arm of the Bolshevik government. Initially, this army was composed primarily of volunteers and Tsarist supporters but were later joined by the Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

, including Don Kalmyks, many of whom resisted the Bolshevik policy of decossackization.

The second revolution split the Kalmyk people into opposing camps. Many were dissatisfied with the Tsarist government for its historic role in promoting the colonization of the Kalmyk steppe and in encouraging the russification of the Kalmyk people. But others also felt hostility towards Bolshevism for two reasons: (1) the loyalty of the Kalmyk people to their traditional leaders (i.e., nobility and clergy) – sources of anti-Communism – was deeply ingrained; and (2) the Bolshevik exploitation of the conflict between the Kalmyks and the local Russian peasants who seized Kalmyk land and livestock (Loewenthal, 1952:4).

The Astrakhan Kalmyk nobility, led by Prince Danzan Tundutov of the Baga Dörbets and Prince Sereb-Djab Tiumen of the Khoshuts, expressed their anti-Bolshevik sentiments by seeking to integrate the Astrakhan Kalmyks into the military units of the Astrakhan Cossacks. But before a general mobilization of Kalmyk horsemen could occur, the Red Army seized power in Astrakhan and in the Kalmyk steppe thereby preventing the mobilization from occurring.

After the capture of Astrakhan, the Bolsheviks engaged in savage reprisals against the Kalmyk people, especially against Buddhist temples and the Buddhist clergy (Arbakov, 1958:30–36). Eventually the Bolsheviks would draft as many as 18,000 Kalmyk horsemen in the Red Army to prevent them from joining the White Army (Borisov, 1926:84). This objective, however, failed to prevent many Red Army Kalmyk horsemen from defecting to the White side.

The majority of the Don Kalmyks also sided with the White Movement to preserve their Cossack lifestyle and proud traditions. As Don Cossacks, the Don Kalmyks first fought under White army General Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

and then under his successor, General Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel

Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel (russian: Пётр Никола́евич барон Вра́нгель, translit=Pëtr Nikoláevič Vrángel', p=ˈvranɡʲɪlʲ, german: Freiherr Peter Nikolaus von Wrangel; April 25, 1928), also known by his ni ...

. Because the Don Cossack Host to which they belonged was the main center of the White Movement and of Cossack resistance, the battles were fought on Cossack lands and were disastrous for the Don Cossacks as villages and entire regions changed hands repeatedly in a fratricidal conflict in which both sides committed terrible atrocities. The Don Cossacks, including the Don Kalmyks, experienced heavy military and civilian losses, either from the fighting itself or from starvation and disease induced by the war. Some argue that the Bolsheviks were guilty of the mass extermination of the Don Cossack people, killing an estimated 70 percent (or 700,000 persons) of the Don Cossack population (Heller and Nekrich, 1988:87).

By October 1920 the Red Army smashed General Wrangel's resistance in the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, forcing the evacuation of some 150,000 White army soldiers and their families to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Turkey. A small group of Don Kalmyks managed to escape on the British and French vessels. The chaos at the Russian port city of Novorossiysk was described by Major H.N.H. Williamson of the British Military Mission to the Don Cossacks as follows:

From there, this group resettled in Europe, primarily in Belgrade (where they established the fourth Buddhist temple in Europe), Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and France where its leaders remained active in the White movement. In 1922, several hundred Don Kalmyks returned home under a general amnesty. Some returnees, including Prince Dmitri Tundutov, were imprisoned and then executed soon after their return.

Formation of the Kalmyk Soviet Republic

The Soviet government established the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast in November 1920. It was formed by merging the Stavropol Kalmyk settlements with a majority of the Astrakhan Kalmyks. A small number of Don Kalmyks (Buzava) from the Don Host migrated to this Oblast. The administrative center was Elista, a small village in the western part of the Oblast that was expanded in the 1920s to reflect its status as the capital of the Oblast. In October 1935, the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast was reorganized into the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The chief occupations of the Republic were cattle breeding, agriculture, including the growing of cotton and fishing. There was no industry.Collectivization and revolts

On 22 January 1922Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

proposed to migrate the Kalmyks during famine in Kalmykia but Russia refused. 71–72,000 Kalmyks died during the famine.XX зууны 20, 30-аад онд халимагуудын 98 хувь аймшигт өлсгөлөнд автсан(Mongolian) The Kalmyks revolted against Russia in 1926, 1930 and 1942–1943. In March 1927, Soviet deported 20,000 Kalmyks to Siberia, tundra and

Karelia

Karelia ( Karelian and fi, Karjala, ; rus, Каре́лия, links=y, r=Karélija, p=kɐˈrʲelʲɪjə, historically ''Korjela''; sv, Karelen), the land of the Karelian people, is an area in Northern Europe of historical significance fo ...

. Soviet scientists attempted to convince the Kalmyks and Buryats

The Buryats ( bua, Буряад, Buryaad; mn, Буриад, Buriad) are a Mongolic ethnic group native to southeastern Siberia who speak the Buryat language. They are one of the two largest indigenous groups in Siberia, the other being the ...

that they were not Mongols during the 20th century under the demongolization policy.

In 1929, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

ordered the forced collectivization of agriculture, forcing the Astrakhan Kalmyks to abandon their traditional nomadic pastoralist lifestyle and to settle in villages. All Kalmyk herdsmen owning more than 500 sheep were deported to labor camps in Siberia.

World War II and exile

In June 1941 the German army invaded the Soviet Union, ultimately taking (some) control of the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In December 1942, however, the Red Army in their turn re-invaded the Republic. On 28 December 1943, the Soviet government accused the Kalmyks of collaborating with the Germans and deported the entire population, including Kalmyk Red Army soldiers, to various locations in Central Asia and Siberia. Within 24 hours the population transfer occurred at night during winter without notice in unheated cattle cars. According to N. F. Bugai, the leading Russian expert on deportations, 4.9% of the Kalmyk population died during the first three months of 1944; 1.5% in the first three months of 1945; and 0.7% in the same period of 1946. From 1945 to 1950, 15,206 Kalmyks died and 7843 were born. The Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was quickly dissolved. Its territory was divided and transferred to the adjacent regions, viz., the Astrakhan and Stalingrad Oblasts and Stavropol Krai. Since no Kalmyks lived there any longer the Soviet authorities changed the names of towns and villages from Kalmyk names to Russian names. For example, Elista became Stepnoi.Return from Siberian exile

Around half of (97–98,000) Kalmyk people deported to Siberia died before being allowed to return home in 1957. The government of the Soviet Union forbade teaching Kalmyk Oirat during the deportation. The Kalmyks' main purpose was to migrate to Mongolia. Under the Law of the Russian Federation of April 26, 1991, "On Rehabilitation of Exiled Peoples", repressions against Kalmyks and other peoples were qualified as an act of