John F. Kennedy's tenure as the

35th president of the United States began with

his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with

his assassination on November 22, 1963. Kennedy, a

Democrat from

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, took office following his narrow victory over

Republican incumbent vice president

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

in the

1960 presidential election. He was succeeded by

Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

.

Kennedy's time in office was marked by

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

tensions with the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. In Cuba, a

failed attempt was made in April 1961 at the

Bay of Pigs to overthrow the government of

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

. In October 1962, the Kennedy administration learned that Soviet

ballistic missiles had been deployed in Cuba; the resulting

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

carried a risk of

nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

, but ended in a compromise with the Soviets publicly withdrawing their missiles from Cuba and the U.S. secretly withdrawing some missiles based in Italy and Turkey. To contain Communist expansion in Asia, Kennedy increased the number of American military advisers in

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

by a factor of 18; a further escalation of the American role in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

would take place after Kennedy's death. In

Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

, Kennedy's

Alliance for Progress

The Alliance for Progress () was an initiative launched by U.S. President John F. Kennedy on March 13, 1961, that aimed to establish economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America. Governor Luis Muñoz Marín of Puerto Rico was a close ...

aimed to promote human rights and foster economic development.

In domestic politics, Kennedy had made bold proposals in his

New Frontier

The term ''New Frontier'' was used by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in his acceptance speech, delivered July 15, in the 1960 United States presidential election to the Democratic National Convention at the Los Angeles Memo ...

agenda, but many of his initiatives were blocked by the

conservative coalition

The conservative coalition, founded in 1937, was an unofficial alliance of members of the United States Congress which brought together the conservative wings of the Republican and Democratic parties to oppose President Franklin Delano Rooseve ...

of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats. The failed initiatives include federal aid to education, medical care for the aged, and aid to economically depressed areas. Though initially reluctant to pursue civil rights legislation, in 1963 Kennedy proposed a major civil rights bill that ultimately became the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. The economy experienced steady growth, low inflation and a drop in unemployment rates during Kennedy's tenure. Kennedy adopted

Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomics, macroeconomic theories and Economic model, models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongl ...

and proposed a tax cut bill that was passed into law as the

Revenue Act of 1964. Kennedy also established the

Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an Independent agency of the U.S. government, independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to communities in partner countries around the world. It was established in Marc ...

and promised to land an American on the Moon and return him safely to Earth, thereby intensifying the

Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

with the Soviet Union.

Kennedy was

assassinated on November 22, 1963, while visiting

Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

, Texas. The

Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President of the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the A ...

concluded that

Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at age 12 for truan ...

acted alone in assassinating Kennedy, but the assassination gave rise to

a wide array of conspiracy theories. Kennedy was the first

Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

elected president, as well as the youngest candidate ever to win a U.S. presidential election. Historians and political scientists tend to

rank Kennedy as an above-average president.

1960 election

Kennedy, who represented

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

in the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

from 1953 to 1960, had finished second on the vice presidential ballot of the

1956 Democratic National Convention. After Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower was reelected over Adlai Stevenson in the

1956 presidential election, Kennedy began to prepare a bid for the presidency in the

1960 election. In January 1960, Kennedy formally announced his candidacy in that year's presidential election. Senator

Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota emerged as Kennedy's primary challenger in the

1960 Democratic primaries, but Kennedy's victory in the heavily-

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

state of West Virginia prompted Humphrey's withdrawal from the race.

[ At the 1960 Democratic National Convention, Kennedy fended off challenges from Stevenson and Senator ]Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

of Texas to win the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention. Kennedy chose Johnson to be his vice-presidential running mate, despite opposition from many liberal delegates and Kennedy's own staff, including his brother Robert F. Kennedy. Kennedy believed that Johnson's presence on the ticket would appeal to Southern voters, and he thought that Johnson could serve as a valuable liaison to the Senate.

Incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

easily won the 1960 Republican Party presidential primaries. Nixon chose Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the chief U.S. delegate to the United Nations, as his running mate.[ Major issues in the campaign included the economy, Kennedy's ]Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and whether the Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

space and missile programs had surpassed those of the U.S.

On November 8, 1960, Kennedy defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections in American history. Kennedy won the popular vote by a narrow margin of 120,000 votes out of a record 68.8 million ballots cast.

On November 8, 1960, Kennedy defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections in American history. Kennedy won the popular vote by a narrow margin of 120,000 votes out of a record 68.8 million ballots cast.[ He won the electoral vote by a wider margin, receiving 303 votes to Nixon's 219. 14 ]unpledged elector

In United States presidential elections, an unpledged elector is a person nominated to stand as an elector but who has not pledged to support any particular presidential or vice presidential candidate, and is free to vote for any candidate when el ...

s from two states—Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

—voted for Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, as did one faithless elector

In the United States Electoral College, a faithless elector is an elector who does not vote for the candidates for U.S. President and U.S. Vice President for whom the elector had pledged to vote, and instead votes for another person for one or ...

in Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained wide majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Nevertheless, 29 House Democrats were displaced, each of whom was a Kennedy progressive. According to one study, "For the first time in a century a party taking over the Presidency failed to gain in the Congress." Kennedy was the first person born in the 20th century to be elected president,Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

elected to the presidency.

Transition

Kennedy placed Clark Clifford in charge of his transition effort.

Inauguration

Kennedy was inaugurated as the nation's 35th president on January 20, 1961, on the East Portico of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

. Chief Justice Earl Warren administered the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

. In his inaugural address, Kennedy spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens, famously saying: "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country." He also invited the nations of the world to join to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself."

Administration

Kennedy spent the eight weeks following his election choosing his cabinet, staff and top officials. He retained J. Edgar Hoover as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a United States federal law enforcement agency, and is responsible for its day-to-day operations. The FBI director is appointed for a ...

and Allen Dulles as Director of Central Intelligence. C. Douglas Dillon, a business-oriented Republican who had served as Eisenhower's Undersecretary of State

Undersecretary (or under secretary) is a title for a person who works for and has a lower rank than a secretary (person in charge). It is used in the executive branch of government, with different meanings in different political systems, and is a ...

, was selected as Secretary of the Treasury. Kennedy balanced the appointment of the relatively conservative Dillon by selecting liberal Democrats to hold two other important economic advisory posts; David E. Bell became the Director of the Bureau of the Budget, while Walter Heller served as the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers

The Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) is a United States agency within the Executive Office of the President established in 1946, which advises the president of the United States on economic policy. The CEA provides much of the empirical resea ...

.

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

, who was well known as one of Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

's " Whiz Kids", was appointed Secretary of Defense. Rejecting liberal pressure to choose Stevenson as Secretary of State, Kennedy instead turned to Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States secretary of state from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving secretary of state after Cordell Hull from the ...

, a restrained former Truman official, to lead the Department of State. Stevenson accepted a non-policy role as the ambassador to the United Nations. In spite of concerns over nepotism

Nepotism is the act of granting an In-group favoritism, advantage, privilege, or position to Kinship, relatives in an occupation or field. These fields can include business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, religion or health care. In ...

, Kennedy's father insisted that Robert F. Kennedy become Attorney General, and the younger Kennedy became the "assistant president" who advised on all major issues. Kennedy scrapped the decision-making structure of Eisenhower, preferring an organizational structure of a wheel with all the spokes leading to the president; he was ready and willing to make the increased number of quick decisions required in such an environment. Though the cabinet remained an important body, Kennedy generally relied more on his staffers within the

Kennedy scrapped the decision-making structure of Eisenhower, preferring an organizational structure of a wheel with all the spokes leading to the president; he was ready and willing to make the increased number of quick decisions required in such an environment. Though the cabinet remained an important body, Kennedy generally relied more on his staffers within the Executive Office of the President

The Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. The office consists o ...

. Unlike Eisenhower, Kennedy did not have a chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supportin ...

, but instead relied on a small number of senior aides, including appointments secretary Kenneth O'Donnell. National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy

McGeorge "Mac" Bundy (March 30, 1919 – September 16, 1996) was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Fou ...

was the most important adviser on foreign policy, eclipsing Secretary of State Rusk. Ted Sorensen was a key advisor on domestic issues who also wrote many of Kennedy's speeches. Other important advisers and staffers included Larry O'Brien, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., press secretary Pierre Salinger, General Maxwell D. Taylor

Maxwell Davenport Taylor (26 August 1901 – 19 April 1987) was a senior United States Army Officer (armed forces), officer and diplomat during the Cold War. He served with distinction in World War II, most notably as commander of the 101st Air ...

, and W. Averell Harriman. Kennedy maintained cordial relations with Vice President Johnson, who was involved in issues like civil rights and space policy, but Johnson did not emerge as an especially influential vice president.

William Willard Wirtz Jr. was the last surviving member of Kennedy's cabinet, and died on April 24, 2010.

Judicial appointments

Kennedy made two appointments to the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

. After the resignation of Charles Evans Whittaker in early 1962, President Kennedy assigned Attorney General Kennedy to conduct a search of potential successors, and the attorney general compiled a list consisting of Deputy Attorney General Byron White

Byron Raymond "Whizzer" White (June 8, 1917 – April 15, 2002) was an American lawyer, jurist, and professional American football, football player who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, associate justice of the Supreme ...

, Secretary of Labor Arthur Goldberg, federal appellate judge William H. Hastie, legal professor Paul A. Freund, and two state supreme court justices. Kennedy narrowed his choice down to Goldberg and White, and he ultimately chose the latter, who was quickly confirmed by the Senate. A second vacancy arose later in 1962 due to the retirement of Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

. Kennedy quickly appointed Goldberg, who easily won confirmation by the Senate. Goldberg resigned from the court in 1965 to accept appointment as ambassador to the United Nations, but White remained on the court until 1993, often serving as a key swing vote between liberal and conservative justices.

The president handled Supreme Court appointments. Other judges were selected by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Including new federal judgeships created in 1961, 130 individuals were appointed to the federal courts. Among them was Thurgood Marshall

Thoroughgood "Thurgood" Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme C ...

, who later joined the Supreme Court. Ivy League undergraduate colleges were attended by 9% of the appointees; 19% attended Ivy League law schools. In terms of religion, 61% were Catholics, 38% were Protestant, and 11% were Jewish. Almost all (91%) were Democrats, but few had extensive experience in electoral politics.

Foreign affairs

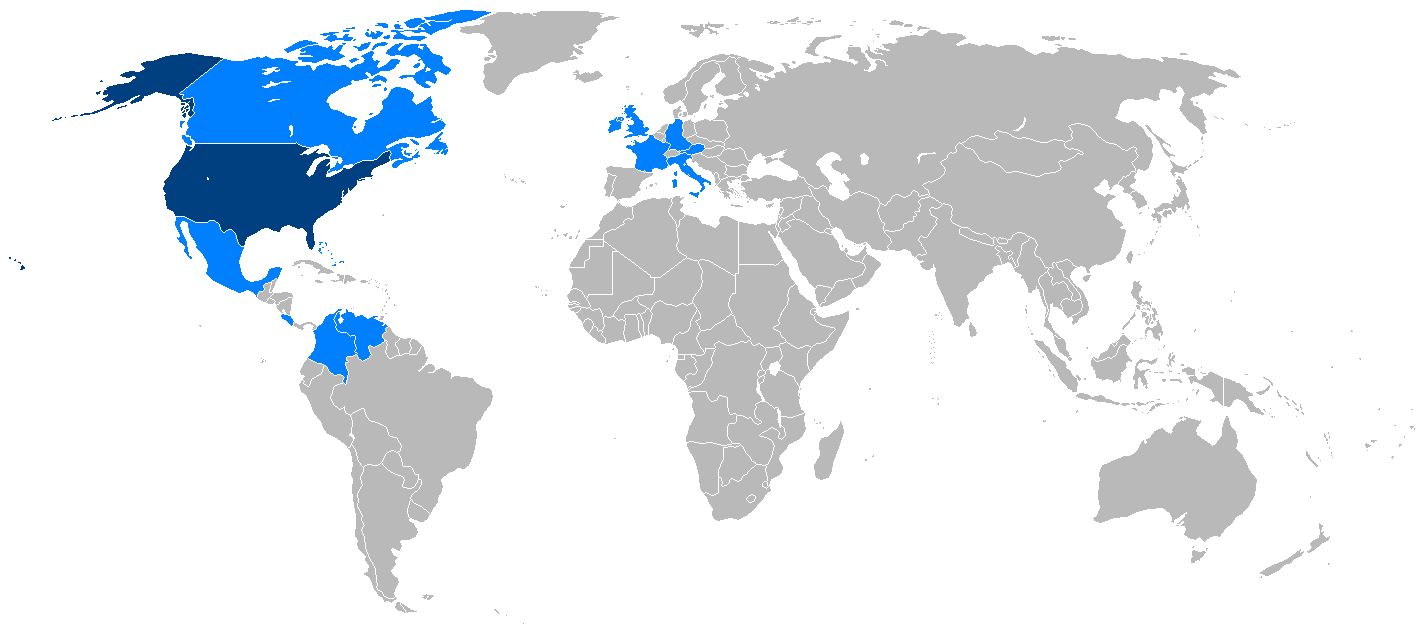

Peace Corps

An agency to enable Americans to volunteer in developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed Secondary sector of the economy, industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. ...

appealed to Kennedy because it fit in with his campaign themes of self-sacrifice and volunteerism, while also providing a way to redefine American relations with the Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

. His use of war rhetoric for peaceful ends made his appeal for the new idea compelling to public opinion.

On March 1, 1961, Kennedy signed Executive Order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

10924 that officially started the Peace Corps. He appointed his brother-in-law, Sargent Shriver, to serve the agency's first director. Due in large part to Shriver's effective lobbying efforts, Congress approved the permanent establishment of the Peace Corps program on September 22, 1961. Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

) and Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

were the first countries to participate in the program. Kennedy took great pride in the Peace Corps, and he ensured that it remained free of CIA influence, but he largely left its administration to Shriver. Kennedy also saw the program as a means of countering the stereotype of the " Ugly American" and " Yankee imperialism," especially in the emerging nations of post-colonial Africa and Asia. In the first twenty-five years, more than 100,000 Americans served in 44 countries as part of the program. Most Peace Corps volunteers taught English in schools, but many became involved in activities like construction and food delivery.

The Cold War and flexible response

Kennedy's foreign policy was dominated by American confrontations with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, manifested by proxy contests in the global state of tension known as the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Like his predecessors, Kennedy adopted the policy of containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

, which sought to stop the spread of communism. President Eisenhower's New Look policy had emphasized the use of nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

to deter the threat of Soviet aggression. By 1960, however, public opinion was turning against New Look because it was not effective in stemming communist-inspired Third World revolutions. Fearful of the possibility of a global nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

, Kennedy implemented a new strategy known as flexible response. This strategy relied on conventional arms to achieve limited goals. As part of this policy, Kennedy expanded the United States special operations forces, elite military units that could fight unconventionally in various conflicts. Kennedy hoped that the flexible response strategy would allow the U.S. to counter Soviet influence without resorting to war. At the same time, he ordered a massive build-up of the nuclear arsenal to establish superiority over the Soviet Union.

In pursuing this military build-up, Kennedy shifted away from Eisenhower's deep concern for budget deficits caused by military spending. In contrast to Eisenhower's warning about the perils of the military-industrial complex, Kennedy focused on rearmament. From 1961 to 1964 the number of nuclear weapons increased by 50 percent, as did the number of B-52 bombers to deliver them. The new ICBM force grew from 63 intercontinental ballistic missiles to 424. He authorized 23 new Polaris submarines, each of which carried 16 nuclear missiles. Meanwhile, he called on cities to prepare fallout shelters

A fallout shelter is an enclosed space specially designated to protect occupants from radioactive debris or nuclear fallout, fallout resulting from a nuclear explosion. Many such shelters were constructed as civil defense measures during the ...

for nuclear war.

In January 1961, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

declared his support for wars of national liberation

Wars of national liberation, also called wars of independence or wars of liberation, are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) ...

. Kennedy interpreted this step as a direct threat to the "free world."

Decolonization and developing countries

Between 1960 and 1963, twenty-four countries

A country is a distinct part of the Earth, world, such as a state (polity), state, nation, or other polity, political entity. When referring to a specific polity, the term "country" may refer to a sovereign state, List of states with limited r ...

gained independence as the process of decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

continued. Many of these nations sought to avoid close alignment with either the United States or the Soviet Union, and in 1961, the leaders of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, and Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

created the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

. Kennedy set out to woo the leaders and people of the Third World, expanding economic aid and appointing knowledgeable ambassadors. His administration established the Food for Peace program and the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an Independent agency of the U.S. government, independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to communities in partner countries around the world. It was established in Marc ...

to provide aid to developing countries in various ways. The Food for Peace program became a central element in American foreign policy, and eventually helped many countries to develop their economies and become commercial import customers.

During his presidency, Kennedy sought closer relations with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

through increased economic and a tilt away from Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

, but made little progress in bringing India closer to the United States. Kennedy hoped to minimize Soviet influence in Egypt through good relations with President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

, but Nasser's hostility

Hostility is seen as a form of emotionally charged aggressive behavior. In everyday speech, it is more commonly used as a synonym for anger and aggression.

It appears in several psychological theories. For instance it is a Facet (psychology), f ...

towards Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

and Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

closed off the possibility of closer relations. In Southeast Asia, Kennedy helped mediate the West New Guinea dispute

The West New Guinea dispute (1950–1962), also known as the West Irian dispute, was a diplomatic and political conflict between the Netherlands and Indonesia over the territory of Dutch New Guinea. While the Netherlands had ceded sovereignty o ...

, convincing Indonesia and the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

to agree to a plebiscite to determine the status of Dutch New Guinea.

Congo Crisis

Having chaired a subcommittee on Africa of the U.S. Senate's Foreign Relations Committee, Kennedy had developed a special interest in Africa. During the election campaign, Kennedy managed to mention Africa nearly 500 times, often attacking the Eisenhower administration for losing ground on that continent, and stressed that the U.S. should be on the side of anti-colonialism and self-determination.Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis () was a period of Crisis, political upheaval and war, conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost ...

to be one of the most important foreign policy issues facing his presidency. The Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

was given its independence from Belgian colonial rule on June 30, 1960, and was almost immediately torn apart by what President Kennedy described as "civil strife, political unrest and public disorder."Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba ( ; born Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa; 2 July 192517 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic o ...

had been murdered early in 1961 despite the presence of a United Nations peacekeeping force (supported by Kennedy); Moïse Tshombe

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe (sometimes written Tshombé; 10 November 1919 – 29 June 1969) was a List of people from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of ...

, leader of State of Katanga

The State of Katanga (; ), also known as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Republic of Congo (Léopoldville), Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moïse Tshombe, leader of the local CO ...

, declared its independence from the Congo and the Soviet Union responded by sending weapons and technicians to underwrite their struggle. The crisis, exacerbated by Cold War tensions, continued well into the 1960s.

Cuba and the Soviet Union

Bay of Pigs Invasion

Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (born Rubén Zaldívar; January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who played a dominant role in Cuban politics from his initial rise to power as part of the 1933 Revolt of t ...

, a Cuban dictator friendly towards the United States, had been forced out office in 1959 by the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

. Many in the United States, including Kennedy himself, had initially hoped that Batista's successor, Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

would preside over democratic reforms. Dashing those hopes, by the end of 1960 Castro had embraced Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, confiscated American property, and accepted Soviet aid. The Eisenhower administration had created a plan to overthrow Castro's regime though an invasion of Cuba by a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of U.S.-trained, anti-Castro Cuban exiles led by CIA paramilitary officers. Kennedy had campaigned on a hardline stance against Castro, and when presented with the plan that had been developed under the Eisenhower administration, he enthusiastically adopted it regardless of the risk of inflaming tensions with the Soviet Union.Chester Bowles

Chester Bliss Bowles (April 5, 1901 – May 25, 1986) was an American diplomat and ambassador, List of governors of Connecticut, governor of Connecticut, congressman and co-founder of a major advertising agency, Benton & Bowles, now part of Publi ...

, and former Secretary of State Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

, opposed the operation, but Bundy and McNamara both favored it, as did the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

, despite serious reservations. Kennedy approved the final invasion plan on April 4, 1961.

On April 15, 1961, eight CIA-supplied B-26 bombers left Nicaragua to bomb Cuban airfields. The bombers missed many of their targets and left most of Castro's air force intact. On April 17, the 1,500 U.S.-trained Cuban exile invasion force, known as Brigade 2506

Brigade 2506 (Brigada Asalto 2506) was a CIA-sponsored group of Cuban exiles formed in 1960 to attempt the military overthrow of the Cuban government headed by Fidel Castro. It carried out the abortive Bay of Pigs Invasion landings in Cuba

...

, landed on the beach at Playa Girón in the Bay of Pigs and immediately came under heavy fire. The goal was to spark a widespread popular uprising against Castro, but no such uprising occurred. Although the Eisenhower administration plan had called for an American airstrike to hold back the Cuban counterattack until the invaders were established, Kennedy rejected the strike because it would emphasize the American sponsorship of the invasion. CIA director Allen Dulles later stated that they thought the president would authorize any action required for success once the troops were on the ground. The invading force was defeated within two days by the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces

The Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (; FAR) are the military forces of Cuba. They include Cuban Revolutionary Army, Revolutionary Army, Cuban Revolutionary Navy, Revolutionary Navy, Cuban Revolutionary Air and Air Defense Force, Revolutionary A ...

; 114 were killed and over 1,100 were taken prisoner. Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release of the 1,189 survivors. After twenty months, Cuba released the captured exiles in exchange for a ransom of $53 million worth of food and medicine.

Despite the lack of direct U.S. military involvement, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and the international community all recognized that the U.S. had backed the invasion. Kennedy focused primarily on the political repercussions of the plan rather than military considerations. In the aftermath, he took full responsibility for the failure, saying: "We got a big kick in the leg and we deserved it. But maybe we'll learn something from it." Kennedy's approval ratings climbed afterwards, helped in part by the vocal support given to him by Nixon and Eisenhower. Outside the United States, however, the operation undermined Kennedy's reputation as a world leader, and raised tensions with the Soviet Union. A secret review conducted by Lyman Kirkpatrick of the CIA concluded that the failure of the invasion resulted less from a decision against airstrikes and had more to do with the fact that Cuba had a much larger defending force and that the operation suffered from "poor planning, organization, staffing and management". The Kennedy administration banned all Cuban imports and convinced the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS or OEA; ; ; ) is an international organization founded on 30 April 1948 to promote cooperation among its member states within the Americas.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, the OAS is ...

to expel Cuba. Kennedy dismissed Dulles as director of the CIA and increasingly relied on close advisers like Sorensen, Bundy, and Robert Kennedy as opposed to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the CIA, and the State Department.

Operation Mongoose

In late-1961, the White House formed the Special Group (Augmented), headed by Robert Kennedy and including Edward Lansdale, Secretary Robert McNamara, and others. The group's objective—to overthrow Castro via espionage, sabotage, and other covert tactics—was never pursued. In November 1961, he authorized Operation Mongoose (also known as the Cuban Project).false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misrep ...

attacks against American military and civilian targets,

Vienna Summit

In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy announced that he would meet with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

at the June 1961 Vienna summit. The summit would cover several topics, but both leaders knew that the most contentious issue would be that of Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, which had been divided into two cities with the start of the Cold War. The enclave of West Berlin

West Berlin ( or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin from 1948 until 1990, during the Cold War. Although West Berlin lacked any sovereignty and was under military occupation until German reunification in 1 ...

lay within Soviet-allied East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

, but was supported by the U.S. and other Western powers. The Soviets wanted to reunify Berlin under the control of East Germany, partly due to the large number of East Germans who had fled to West Berlin. Khrushchev had clashed with Eisenhower over the issue but had tabled it after the 1960 U-2 incident

On 1 May 1960, a United States Lockheed U-2, U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, spy plane was shot down by the Soviet Air Defence Forces while conducting photographic aerial reconnaissance inside Soviet Union, Soviet territory. Flown by American pil ...

; with the inauguration of a new U.S. president, Khrushchev was once again determined to bring the status of West Berlin to the fore. Kennedy's handling of the Bay of Pigs crisis convinced him that Kennedy would wither under pressure. Kennedy, meanwhile, wanted to meet with Khrushchev as soon as possible in order to reduce tensions and minimize the risk of nuclear war. Prior to the summit, Harriman advised Kennedy, " hrushchev'sstyle will be to attack you and see if he can get away with it. Laugh about it, don't get into a fight. Rise above it. Have some fun."

On the way to the summit, Kennedy stopped in Paris to meet French President Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

, who advised him to ignore Khrushchev's abrasive style. The French president feared the United States' presumed influence in Europe. Nevertheless, de Gaulle was quite impressed with the young president and his family. Kennedy picked up on this in his speech in Paris, saying that he would be remembered as "the man who accompanied Jackie Kennedy to Paris."

On June 4, 1961, the president met with Khrushchev in Vienna, where he made it clear that any treaty between East Berlin

East Berlin (; ) was the partially recognised capital city, capital of East Germany (GDR) from 1949 to 1990. From 1945, it was the Allied occupation zones in Germany, Soviet occupation sector of Berlin. The American, British, and French se ...

and the Soviet Union that interfered with U.S. access rights in West Berlin would be regarded as an act of war. The two leaders also discussed the situation in Laos, the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis () was a period of Crisis, political upheaval and war, conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost ...

, China's fledgling nuclear program, a potential nuclear test ban treaty, and other issues. Shortly after Kennedy returned home, the Soviet Union announced its intention to sign a treaty with East Berlin that would threaten Western access to West Berlin. Kennedy, depressed and angry, assumed that his only option was to prepare the country for nuclear war, which he personally thought had a one-in-five chance of occurring.

Berlin

President Kennedy called Berlin "the great testing place of Western courage and will."Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (, ) was a guarded concrete Separation barrier, barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and the East Germany, German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germany). Construction of the B ...

. Kennedy acquiesced to the wall, though he sent Vice President Johnson to West Berlin to reaffirm U.S. commitment to the enclave's defense. In the following months, in a sign of rising Cold War tensions, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union ended a moratorium on nuclear weapon testing. A brief stand-off between U.S. and Soviet tanks occurred at Checkpoint Charlie

Checkpoint Charlie (or "Checkpoint C") was the Western Bloc, Western Bloc's name for the best-known Berlin Wall crossing point between East Berlin and West Berlin during the Cold War (1947–1991), becoming a symbol of the Cold War, representin ...

in October following a dispute over free movement of Allied personnel. The crisis was defused largely through a backchannel communication the Kennedy administration had set up with Soviet spy Georgi Bolshakov.

In 1963, French President Charles de Gaulle was trying to build a Franco-West German counterweight to the American and Soviet spheres of influence. To Kennedy's eyes, this Franco-German cooperation seemed directed against NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

's influence in Europe. To reinforce the U.S. alliance with West Germany, Kennedy travelled to West Germany in June 1963. On June 26, Kennedy toured West Berlin, culminating in his famous " Ich bin ein Berliner" ("I am a Berliner") speech in front of hundreds of thousands of enthusiastic Berliners. Kennedy used the construction of the Berlin Wall as an example of the failures of communism: "Freedom has many difficulties, and democracy is not perfect. But we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in, to prevent them from leaving us." In remarks to his aides on the Berlin Wall, Kennedy noted that "it's not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war."

Cuban Missile Crisis

In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuban and Soviet leaders feared that the United States was planning another invasion of Cuba, and Khrushchev increased economic and military assistance to the island. The Soviet Union planned to allocate in Cuba 49

In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuban and Soviet leaders feared that the United States was planning another invasion of Cuba, and Khrushchev increased economic and military assistance to the island. The Soviet Union planned to allocate in Cuba 49 medium-range ballistic missile

A medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) is a type of ballistic missile with medium range (aeronautics), range, this last classification depending on the standards of certain organizations. Within the United States Department of Defense, U.S. D ...

s, 32 intermediate-range ballistic missile

An intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range between (), categorized between a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) and an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Classifying ball ...

s, 49 light Il-28 bombers and about 100 tactical nuclear weapons. The Kennedy administration viewed the growing Cuba-Soviet alliance with alarm, fearing that it could eventually pose a threat to the United States. Kennedy did not believe that the Soviet Union would risk placing nuclear weapons in Cuba, but he dispatched CIA U-2 spy planes to determine the extent of the Soviet military build-up. On October 14, 1962, the spy planes took photographs of intermediate-range ballistic missile sites being built in Cuba by the Soviets. The photos were shown to Kennedy on October 16, and a consensus was reached that the missiles were offensive in nature.

Following the Vienna Summit, Khrushchev came to believe that Kennedy would not respond effectively to provocations. He saw the deployment of the missiles in Cuba as a way to close the " missile gap" and provide for the defense of Cuba. By late 1962, both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

s (ICBMs) capable of delivering nuclear payloads, but the U.S. maintained well over 100 ICBMs, as well as over 100 submarine-launched ballistic missile

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from Ballistic missile submarine, submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which ...

(SLBMs). By contrast, the Soviet Union did not possess SLBMs, and had less than 25 ICBMs. The placement of missiles in Cuba thus threatened to significantly enhance the Soviet Union's first strike capability and even the nuclear imbalance. Kennedy himself did not believe that the deployment of missiles to Cuba fundamentally altered the strategic balance of the nuclear forces; more significant for him was the political and psychological implications of allowing the Soviet Union to maintain nuclear weapons in Cuba.

Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R., but if the U.S. did nothing, it would be faced with the increased threat from close-range nuclear weapons (positioned approximately 90 mi (140 km) away from the Florida coast). The U.S. would also appear to the world as less committed to the defense of the Western Hemisphere. On a personal level, Kennedy needed to show resolve in reaction to Khrushchev, especially after the Vienna summit. To deal with the crisis, he formed an ad hoc body of key advisers, later known as

Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R., but if the U.S. did nothing, it would be faced with the increased threat from close-range nuclear weapons (positioned approximately 90 mi (140 km) away from the Florida coast). The U.S. would also appear to the world as less committed to the defense of the Western Hemisphere. On a personal level, Kennedy needed to show resolve in reaction to Khrushchev, especially after the Vienna summit. To deal with the crisis, he formed an ad hoc body of key advisers, later known as EXCOMM

The Executive Committee of the National Security Council (commonly referred to as simply the Executive Committee or ExComm) was a body of United States government officials that convened to advise President John F. Kennedy during the Cuban Miss ...

, that met secretly between October 16 and 28. The members of EXCOMM agreed that the missiles must be removed from Cuba, but differed as to the best method. Some favored an airstrike, possibly followed by an invasion of Cuba, but Robert Kennedy and others argued that a surprise airstrike would be immoral and would invite Soviet reprisals. The other major option that emerged was a naval blockade, designed to prevent further arms shipments to Cuba. Though he had initially favored an immediate air strike, the president quickly came to favor the naval blockade the first method of response, while retaining the option of an airstrike at a later date. EXCOMM voted 11-to-6 in favor of the naval blockade, which was also supported by British ambassador David Ormsby-Gore and Eisenhower, both of whom were consulted privately. On October 22, after privately informing the cabinet and leading members of Congress about the situation, Kennedy announced on national television that the U.S. had discovered evidence of the Soviet deployment of missiles to Cuba. He called for the immediate withdrawal of the missiles, as well as the convening of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

and the Organization of American States (OAS). Finally, he announced that the U.S. would begin a naval blockade of Cuba in order to intercept arms shipments.

On October 23, in a unanimous vote, the OAS approved a resolution that endorsed the blockade and called for the removal of the Soviet nuclear weapons from Cuba. That same day, Adlai Stevenson presented the U.S. case to the UN Security Council, though the Soviet Union's veto power precluded the possibility of passing a Security Council resolution. On the morning of October 24, over 150 U.S. ships were deployed to enforce the blockade against Cuba. Several Soviet ships approached the blockade line, but they stopped or reversed course to avoid the blockade. On October 25, Khrushchev offered to remove the missiles if the U.S. promised not to invade Cuba. The next day, he sent a second message in which he also demanded the removal of PGM-19 Jupiter missiles from Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. EXCOMM settled on what has been termed the " Trollope ploy;" the U.S. would respond to the Khrushchev's first message and ignore the second. Kennedy managed to preserve restraint when a Soviet missile unauthorizedly downed a U.S. Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft over Cuba, killing the pilot Rudolf Anderson. On October 27, Kennedy sent a letter to Khrushchev calling for the removal of the Cuban missiles in return for an end to the blockade and an American promise to refrain from invading Cuba. At the president's direction, Robert Kennedy privately informed Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin

Anatoly Fyodorovich Dobrynin (, 16 November 1919 – 6 April 2010) was a Soviet Union, Soviet politician, statesman, diplomat, and politician. He was the Ambassador of Russia to the United States, Soviet ambassador to the United States for more ...

that the U.S. would remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey "within a short time after this crisis was over." Few members of EXCOMM expected Khrushchev to agree to the offer, but on October 28 Khrushchev publicly announced that he would withdraw the missiles from Cuba. Negotiations over the details of the withdrawal continued, but the U.S. ended the naval blockade on November 20, and most Soviet soldiers left Cuba by early 1963.

The U.S. publicly promised never to invade Cuba and privately agreed to remove its missiles in Italy and Turkey; the missiles were by then obsolete and had been supplanted by submarines equipped with UGM-27 Polaris

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy was involved in the Jupiter missi ...

missiles. In the aftermath of the crisis, a Moscow–Washington hotline

The Moscow–Washington hotline (formally known in the United States as the Washington–Moscow Direct Communications Link; ) is a system that allows direct communication between the leaders of the United States and the Russia, Russian Federation ...

was established to ensure clear communications between the leaders of the two countries. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before or since. In the end, "the humanity" of the two men prevailed. The crisis improved the image of American willpower and the president's credibility. Kennedy's approval rating increased from 66% to 77% immediately thereafter. Kennedy's handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis has received wide praise from many scholars, although some critics fault the Kennedy administration for precipitating the crisis with its efforts to remove Castro. Khrushchev, meanwhile, was widely mocked for his performance, and was removed from power in October 1964. According to Anatoly Dobrynin, the top Soviet leadership took the Cuban outcome as "a blow to its prestige bordering on humiliation."

Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

Troubled by the long-term dangers of radioactive contamination

Radioactive contamination, also called radiological pollution, is the deposition of, or presence of Radioactive decay, radioactive substances on surfaces or within solids, liquids, or gases (including the human body), where their presence is uni ...

and nuclear weapons proliferation, Kennedy and Khrushchev agreed to negotiate a nuclear test ban treaty, originally conceived in Adlai Stevenson's 1956 presidential campaign. In their Vienna summit meeting in June 1961, Khrushchev and Kennedy had reached an informal understanding against nuclear testing, but further negotiations were derailed by the resumption of nuclear testing. In his address to the United Nations on September 25, 1961, Kennedy challenged the Soviet Union "not to an arms race, but to a peace race." Unsuccessful in his efforts to reach a diplomatic agreement, Kennedy reluctantly announced the resumption of atmospheric testing on April 25, 1962.[ ] Soviet-American relations improved after the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the powers resumed negotiations over a test ban treaty. Negotiations were facilitated by the Vatican and by the shuttle diplomacy of editor Norman Cousins.

On June 10, 1963, Kennedy delivered a commencement address at the American University

The American University (AU or American) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Its main campus spans 90-acres (36 ha) on Ward Circle, in the Spri ...

in Washington, D.C. Also known as "A Strategy of Peace", not only did Kennedy outline a plan to curb nuclear arms, but he also "laid out a hopeful, yet realistic route for world peace at a time when the U.S. and Soviet Union faced the potential for an escalating nuclear arms race." Kennedy also made two announcements: 1.) that the Soviets had expressed a desire to negotiate a nuclear test ban treaty, and 2.) that the U.S. had postponed planned atmospheric tests. "If we cannot end our differences," he said, "at least we can help make the world a safe place for diversity." The Soviet government broadcast a translation of the entire speech and allowed it to be reprinted in the controlled Soviet press.Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel ( ; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), known as Lord Dunglass from 1918 to 1951 and the Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

. The U.S. Senate approved the treaty on September 23, 1963, by an 80–19 margin. Kennedy signed the ratified treaty on October 7, 1963.

Southeast Asia

Laos

When briefing Kennedy, Eisenhower emphasized that the communist threat in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

required priority. Eisenhower considered Laos

Laos, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR), is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Thailand to the west and ...

to be "the cork in the bottle;" if it fell to communism, Eisenhower believed other Southeast Asian countries would as well. The Joint Chiefs proposed sending 60,000 American soldiers to uphold the friendly government, but Kennedy rejected this strategy in the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. He instead sought a negotiated solution between the government and the left-wing insurgents, who were backed by North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

and the Soviet Union. Kennedy was unwilling to send more than a token force to neighboring Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, a key American ally. By the end of the year, Harriman had helped arrange the International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos, which temporarily brought an end to the crisis, but the Laotian Civil War

The Laotian Civil War was waged between the Communist Pathet Lao and the Royal Lao Government from 23 May 1959 to 2 December 1975. The Kingdom of Laos was a covert Theatre (warfare), theater during the Vietnam War with both sides receiving heavy ...

continued. Though he was unwilling to commit U.S. forces to a major military intervention in Laos, Kennedy did approve CIA activities in Laos designed to defeat communist insurgents through bombing raids and the recruitment of the Hmong people

The Hmong people ( RPA: , CHV: ''Hmôngz'', Nyiakeng Puachue: , Pahawh Hmong: , , zh, c=苗族蒙人) are an indigenous group in East Asia and Southeast Asia. In China, the Hmong people are classified as a sub-group of the Miao people. Th ...

.

Vietnam

As a U.S. congressman in 1951, Kennedy became fascinated with Vietnam after visiting the area as part of a fact-finding mission to Asia and the Middle East, even stressing in a subsequent radio address that he strongly favored "check ngthe southern drive of communism." As a U.S. senator in 1956, Kennedy publicly advocated for greater U.S. involvement in Vietnam. During his presidency, Kennedy continued policies that provided political, economic, and military support to the South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

ese government.

The

The Viet Cong

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, and ...

began assuming a predominant presence in late 1961, initially seizing the provincial capital of Phuoc Vinh. After a mission to Vietnam in October, presidential adviser General Maxwell D. Taylor

Maxwell Davenport Taylor (26 August 1901 – 19 April 1987) was a senior United States Army Officer (armed forces), officer and diplomat during the Cold War. He served with distinction in World War II, most notably as commander of the 101st Air ...

and Deputy National Security Adviser Walt Rostow

Walt Whitman Rostow (; October 7, 1916 – February 13, 2003) was an American economist, professor and political theorist who served as national security advisor to president of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1969.

Rostow wor ...

recommended the deployment of 6,000 to 8,000 U.S. combat troops to Vietnam. Kennedy increased the number of military advisers and special forces

Special forces or special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equip ...

in the area, from 11,000 in 1962 to 16,000 by late 1963, but he was reluctant to order a full-scale deployment of troops. However, Kennedy, who was wary about the region's successful war of independence against France, was also eager to not give the impression to the Vietnamese people that the United States was acting as the region's new colonizer, even stating in his journal at one point that the United States was "more and more becoming colonists in the minds of the people."

In late 1961, Kennedy sent Roger Hilsman, then director of the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), to assess the situation in Vietnam. There, Hilsman met Sir Robert Grainger Ker Thompson, head of the British Advisory Mission to South Vietnam, and the Strategic Hamlet Program was formed. It was approved by Kennedy and South Vietnam President Ngo Dinh Diem

Ngô Đình Diệm ( , or ; ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician who was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955) and later the first president of South Vietnam (Republic of V ...

. It was implemented in early 1962 and involved some forced relocation, village internment, and segregation of rural South Vietnamese into new communities where the peasantry would be isolated from communist insurgents. It was hoped that these new communities would provide security for the peasants and strengthen the tie between them and the central government. By November 1963, the program waned and officially ended in 1964.

On January 18, 1962, Kennedy formally authorized escalated involvement when he signed the National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) – "Subversive Insurgency (War of Liberation)". " Operation Ranch Hand", a large-scale aerial defoliation effort, began on the roadsides of South Vietnam initiating the use of the herbicide Agent Orange

Agent Orange is a chemical herbicide and defoliant, one of the tactical uses of Rainbow Herbicides. It was used by the U.S. military as part of its herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1962 to 1971. T ...

on foliage and to combat guerrilla defendants. Initially under consideration as to whether or not the use of the chemical would violate the Geneva Convention, Secretary of State Dean Rusk argued to Kennedy that " e use of defoliant does not violate any rule of international law concerning the conduct of chemical warfare and is an accepted tactic of war. Precedent has been established by the British during the emergency in Malaya in their use of aircraft for destroying crops by chemical spraying."

In August 1963, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. replaced Frederick Nolting as the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. Days after Lodge's arrival in South Vietnam, Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu ordered South Vietnam forces, funded and trained by the CIA, to quell Buddhist demonstrations. The crackdowns heightened expectations of a coup d'état to remove Diem with (or perhaps by) his brother, Nhu. Lodge was instructed to try getting Diem and Nhu to step down and leave the country. Diem would not listen to Lodge. Cable 243 (DEPTEL 243) followed, dated August 24, declaring that Washington would no longer tolerate Nhu's actions, and Lodge was ordered to pressure Diem to remove Nhu. Lodge concluded that the only option was to get the South Vietnamese generals to overthrow Diem and Nhu. At week's end, orders were sent to Saigon and throughout Washington to "destroy all coup cables". At the same time, the first formal anti-Vietnam war sentiment was expressed by U.S. clergy from the Ministers' Vietnam Committee.

A White House meeting in September was indicative of the different ongoing appraisals; Kennedy received updated assessments after personal inspections on the ground by the Departments of Defense (General Victor Krulak) and State ( Joseph Mendenhall). Krulak said that the military fight against the communists was progressing and being won, while Mendenhall stated that the country was civilly being lost to any U.S. influence. Kennedy reacted, asking, "Did you two gentlemen visit the same country?" Kennedy was unaware that both men were so much at odds that they did not speak to each other on the return flight.

In October 1963, Kennedy appointed Defense Secretary McNamara and General Maxwell D. Taylor to a Vietnamese mission in another effort to synchronize the information and formulation of policy. The objective of the McNamara–Taylor mission "emphasized the importance of getting to the bottom of the differences in reporting from U.S. representatives in Vietnam." In meetings with McNamara, Taylor, and Lodge, Diem again refused to agree to governing measures, helping to dispel McNamara's previous optimism about Diem. Taylor and McNamara were enlightened by Vietnam's vice president, Nguyen Ngoc Tho (choice of many to succeed Diem), who in detailed terms obliterated Taylor's information that the military was succeeding in the countryside. At Kennedy's insistence, the mission report contained a recommended schedule for troop withdrawals: 1,000 by year's end and complete withdrawal in 1965, something the NSC considered to be a "strategic fantasy." In late-October, intelligence wires again reported that a coup against the Diem government was afoot. The source, Vietnamese General Duong Van Minh (also known as "Big Minh"), wanted to know the U.S. position. Kennedy instructed Lodge to offer covert assistance to the coup, excluding assassination. On November 1, 1963, South Vietnamese generals, led by "Big Minh", overthrew the Diem government, arresting and then killing Diem and Nhu. Kennedy was shocked by the deaths.

Historians disagree on whether the

In October 1963, Kennedy appointed Defense Secretary McNamara and General Maxwell D. Taylor to a Vietnamese mission in another effort to synchronize the information and formulation of policy. The objective of the McNamara–Taylor mission "emphasized the importance of getting to the bottom of the differences in reporting from U.S. representatives in Vietnam." In meetings with McNamara, Taylor, and Lodge, Diem again refused to agree to governing measures, helping to dispel McNamara's previous optimism about Diem. Taylor and McNamara were enlightened by Vietnam's vice president, Nguyen Ngoc Tho (choice of many to succeed Diem), who in detailed terms obliterated Taylor's information that the military was succeeding in the countryside. At Kennedy's insistence, the mission report contained a recommended schedule for troop withdrawals: 1,000 by year's end and complete withdrawal in 1965, something the NSC considered to be a "strategic fantasy." In late-October, intelligence wires again reported that a coup against the Diem government was afoot. The source, Vietnamese General Duong Van Minh (also known as "Big Minh"), wanted to know the U.S. position. Kennedy instructed Lodge to offer covert assistance to the coup, excluding assassination. On November 1, 1963, South Vietnamese generals, led by "Big Minh", overthrew the Diem government, arresting and then killing Diem and Nhu. Kennedy was shocked by the deaths.

Historians disagree on whether the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...