Kannada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kannada () is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly in the state of

The earliest Kannada inscriptions are from the middle of the 5th century AD, but there are a number of earlier texts that may have been influenced by the ancestor language of Old Kannada.

Iravatam Mahadevan, author of a work on early Tamil epigraphy, argued that oral traditions in Kannada and Telugu existed much before written documents were produced. Although the rock inscriptions of Ashoka were written in Prakrit, the spoken language in those regions was Kannada as the case may be. He can be quoted as follows:

Kannada linguist, historian and researcher B. A. Viveka Rai and Kannada writer, lyricist, and linguist Doddarangegowda assert that due to the extensive trade relations that existed between the ancient Kannada lands ( Kuntalas, Mahishakas, Punnatas, Mahabanas, Asmakas, etc.) and Greece, Egypt, the Hellenistic and Roman empires and others, there was exchange of people, ideas, literature, etc. and a Kannada book existed in the form of a palm-leaf manuscript in the old Alexandria library which was subsequently lost in the fire. They state that this also proves that the Kannada language and literature must have flourished much before the library was established in between c. 285-48 BC. This document played a vital role in getting the classical status to Kannada from the Indian Central Government. The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated to 250 BC) has been suggested to contain words (''Isila'', meaning to throw, viz. an arrow, etc.) in identifiable Kannada.The word ''Isila'' found in the Ashokan inscription (called the Brahmagiri edict from Karnataka) meaning to shoot an arrow, is a Kannada word, indicating that Kannada was a spoken language in the 3rd century BC (D.L. Narasimhachar in Kamath 2001, p5)

In some 3rd–1st century BC Tamil inscriptions, words of Kannada influence such as ''Naliyura'', ''kavuDi'' and ''posil'' were found. In a 3rd-century AD Tamil inscription there is usage of ''oppanappa vIran''. Here the honorific ''appa'' to a person's name is an influence from Kannada. Another word of Kannada origin is ''taayviru'' and is found in a 4th-century AD Tamil inscription. S. Settar studied the ''sittanavAsal'' inscription of first century AD as also the inscriptions at ''tirupparamkunram'', ''adakala'' and ''neDanUpatti''. The later inscriptions were studied in detail by Iravatham Mahadevan also. Mahadevan argues that the words ''erumi'', ''kavuDi'', and ''tAyiyar'' have their origin in Kannada because Tamil cognates are not available. Settar adds the words ''nADu'' and ''iLayar'' to this list. Mahadevan feels that some grammatical categories found in these inscriptions are also unique to Kannada rather than Tamil. Both these scholars attribute these influences to the movements and spread of Jainas in these regions. These inscriptions belong to the period between the first century BC and fourth century AD. These are some examples that are proof of the early usage of a few Kannada origin words in early Tamil inscriptions before the common era and in the early centuries of the common era.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, wrote about pirates between Muziris and Nitrias ( Netravati River), called Nitran by Ptolemy. He also mentions Barace (Barcelore), referring to the modern port city of Mangaluru, upon its mouth. Many of these are Kannada origin names of places and rivers of the Karnataka coast of the 1st century AD.

The Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 AD) mentions places such as Badiamaioi (Badami), Inde (Indi), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudagal), Petrigala (Pattadakal), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Tiripangalida (Gadahinglai), Soubouttou or Sabatha (Savadi), Banaouase (Banavasi), Thogorum (Tagara), Biathana (Paithan), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Aloe (Ellapur) and Pasage (Palasige). He mentions a Satavahana king Sire Polemaios, who is identified with Sri Pulumayi (or Pulumavi), whose name is derived from the Kannada word for ''Puli'', meaning tiger. Some scholars indicate that the name Pulumayi is actually Kannada's ''Puli Maiyi'' or ''One with the body of a tiger'' indicating native Kannada origin for the Satavahanas. Pai identifies all the 10 cities mentioned by Ptolemy (100–170 AD) as lying between the river Benda (or Binda) or Bhima river in the north and Banaouasei ( Banavasi) in the south, viz. Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Inde ( Indi), Tiripangalida ( Gadhinglaj), Hippokoura ( Huvina Hipparagi), Soubouttou ( Savadi), Sirimalaga ( Malkhed), Kalligeris ( Kalkeri), Modogoulla ( Mudgal), and Petirgala ( Pattadakal)—as being located in Northern Karnataka, which explain the existence of Kannada place names (and the language and culture) in the southern Kuntala region during the reign of Vasishtiputra Pulumayi (–125 AD, i.e., late 1st century – early 2nd century AD) who was ruling from Paithan in the north and his son, prince Vilivaya-kura or Pulumayi Kumara was ruling from Huvina Hipparagi in present Karnataka in the south.

An early ancestor of Kannada (or a related language) may have been spoken by Indian traders in Roman-era Egypt and it may account for the Indian-language passages in the ancient Greek play known as the Charition mime.

The earliest Kannada inscriptions are from the middle of the 5th century AD, but there are a number of earlier texts that may have been influenced by the ancestor language of Old Kannada.

Iravatam Mahadevan, author of a work on early Tamil epigraphy, argued that oral traditions in Kannada and Telugu existed much before written documents were produced. Although the rock inscriptions of Ashoka were written in Prakrit, the spoken language in those regions was Kannada as the case may be. He can be quoted as follows:

Kannada linguist, historian and researcher B. A. Viveka Rai and Kannada writer, lyricist, and linguist Doddarangegowda assert that due to the extensive trade relations that existed between the ancient Kannada lands ( Kuntalas, Mahishakas, Punnatas, Mahabanas, Asmakas, etc.) and Greece, Egypt, the Hellenistic and Roman empires and others, there was exchange of people, ideas, literature, etc. and a Kannada book existed in the form of a palm-leaf manuscript in the old Alexandria library which was subsequently lost in the fire. They state that this also proves that the Kannada language and literature must have flourished much before the library was established in between c. 285-48 BC. This document played a vital role in getting the classical status to Kannada from the Indian Central Government. The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated to 250 BC) has been suggested to contain words (''Isila'', meaning to throw, viz. an arrow, etc.) in identifiable Kannada.The word ''Isila'' found in the Ashokan inscription (called the Brahmagiri edict from Karnataka) meaning to shoot an arrow, is a Kannada word, indicating that Kannada was a spoken language in the 3rd century BC (D.L. Narasimhachar in Kamath 2001, p5)

In some 3rd–1st century BC Tamil inscriptions, words of Kannada influence such as ''Naliyura'', ''kavuDi'' and ''posil'' were found. In a 3rd-century AD Tamil inscription there is usage of ''oppanappa vIran''. Here the honorific ''appa'' to a person's name is an influence from Kannada. Another word of Kannada origin is ''taayviru'' and is found in a 4th-century AD Tamil inscription. S. Settar studied the ''sittanavAsal'' inscription of first century AD as also the inscriptions at ''tirupparamkunram'', ''adakala'' and ''neDanUpatti''. The later inscriptions were studied in detail by Iravatham Mahadevan also. Mahadevan argues that the words ''erumi'', ''kavuDi'', and ''tAyiyar'' have their origin in Kannada because Tamil cognates are not available. Settar adds the words ''nADu'' and ''iLayar'' to this list. Mahadevan feels that some grammatical categories found in these inscriptions are also unique to Kannada rather than Tamil. Both these scholars attribute these influences to the movements and spread of Jainas in these regions. These inscriptions belong to the period between the first century BC and fourth century AD. These are some examples that are proof of the early usage of a few Kannada origin words in early Tamil inscriptions before the common era and in the early centuries of the common era.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, wrote about pirates between Muziris and Nitrias ( Netravati River), called Nitran by Ptolemy. He also mentions Barace (Barcelore), referring to the modern port city of Mangaluru, upon its mouth. Many of these are Kannada origin names of places and rivers of the Karnataka coast of the 1st century AD.

The Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 AD) mentions places such as Badiamaioi (Badami), Inde (Indi), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudagal), Petrigala (Pattadakal), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Tiripangalida (Gadahinglai), Soubouttou or Sabatha (Savadi), Banaouase (Banavasi), Thogorum (Tagara), Biathana (Paithan), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Aloe (Ellapur) and Pasage (Palasige). He mentions a Satavahana king Sire Polemaios, who is identified with Sri Pulumayi (or Pulumavi), whose name is derived from the Kannada word for ''Puli'', meaning tiger. Some scholars indicate that the name Pulumayi is actually Kannada's ''Puli Maiyi'' or ''One with the body of a tiger'' indicating native Kannada origin for the Satavahanas. Pai identifies all the 10 cities mentioned by Ptolemy (100–170 AD) as lying between the river Benda (or Binda) or Bhima river in the north and Banaouasei ( Banavasi) in the south, viz. Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Inde ( Indi), Tiripangalida ( Gadhinglaj), Hippokoura ( Huvina Hipparagi), Soubouttou ( Savadi), Sirimalaga ( Malkhed), Kalligeris ( Kalkeri), Modogoulla ( Mudgal), and Petirgala ( Pattadakal)—as being located in Northern Karnataka, which explain the existence of Kannada place names (and the language and culture) in the southern Kuntala region during the reign of Vasishtiputra Pulumayi (–125 AD, i.e., late 1st century – early 2nd century AD) who was ruling from Paithan in the north and his son, prince Vilivaya-kura or Pulumayi Kumara was ruling from Huvina Hipparagi in present Karnataka in the south.

An early ancestor of Kannada (or a related language) may have been spoken by Indian traders in Roman-era Egypt and it may account for the Indian-language passages in the ancient Greek play known as the Charition mime.

There is also a considerable difference between the spoken and written forms of the language. Spoken Kannada tends to vary from region to region. The written form is more or less consistent throughout Karnataka. The Ethnologue reports "about 20 dialects" of Kannada. Among them are Kundagannada (spoken exclusively in Kundapura, Brahmavara, Bynduru and Hebri), Nador-Kannada (spoken by Nadavaru), Havigannada (spoken mainly by Havyaka Brahmins), Are Bhashe (spoken by Gowda community mainly in Madikeri and Sullia region of Dakshina Kannada), Malenadu Kannada (Sakaleshpur, Coorg, Shimoga, Chikmagalur), Sholaga, Gulbarga Kannada, Dharawad Kannada etc. All of these dialects are influenced by their regional and cultural background. The one million Komarpants in and around Goa speak their own dialect of Kannada, known as Halegannada. They are settled throughout Goa state, throughout Uttara Kannada district and Khanapur taluk of Belagavi district, Karnataka. The Halakki Vokkaligas of Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka speak in their own dialect of Kannada called Halakki Kannada or Achchagannada. Their population estimate is about 75,000.

Ethnologue also classifies a group of four languages related to Kannada, which are, besides Kannada proper, Badaga, Holiya, Kurumba and Urali. The Golars or Golkars are a nomadic herdsmen tribe present in Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Seoni and Balaghat districts of Maharashtra and

There is also a considerable difference between the spoken and written forms of the language. Spoken Kannada tends to vary from region to region. The written form is more or less consistent throughout Karnataka. The Ethnologue reports "about 20 dialects" of Kannada. Among them are Kundagannada (spoken exclusively in Kundapura, Brahmavara, Bynduru and Hebri), Nador-Kannada (spoken by Nadavaru), Havigannada (spoken mainly by Havyaka Brahmins), Are Bhashe (spoken by Gowda community mainly in Madikeri and Sullia region of Dakshina Kannada), Malenadu Kannada (Sakaleshpur, Coorg, Shimoga, Chikmagalur), Sholaga, Gulbarga Kannada, Dharawad Kannada etc. All of these dialects are influenced by their regional and cultural background. The one million Komarpants in and around Goa speak their own dialect of Kannada, known as Halegannada. They are settled throughout Goa state, throughout Uttara Kannada district and Khanapur taluk of Belagavi district, Karnataka. The Halakki Vokkaligas of Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka speak in their own dialect of Kannada called Halakki Kannada or Achchagannada. Their population estimate is about 75,000.

Ethnologue also classifies a group of four languages related to Kannada, which are, besides Kannada proper, Badaga, Holiya, Kurumba and Urali. The Golars or Golkars are a nomadic herdsmen tribe present in Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Seoni and Balaghat districts of Maharashtra and

Open Access publication in PDF format

English to Kannada Dictionary, Kannada to English Dictionary PDF

{{Sister bar, Kannada, auto=1, voy=Kannada_phrasebook, wikt=Kannada language, iw=kn Languages attested from the 5th century Classical Language in India Dravidian languages Languages of Andhra Pradesh Languages of Karnataka Languages of Kerala Languages of Tamil Nadu Languages of Telangana Languages written in Brahmic scripts Official languages of India

Karnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

in southwestern India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, and spoken by a minority of the population in all neighbouring states. It has 44 million native speakers, and is additionally a second or third language for 15 million speakers in Karnataka. It is the official and administrative language of Karnataka. It also has scheduled status in India and has been included among the country's designated classical languages.Kuiper (2011), p. 74R Zydenbos in Cushman S, Cavanagh C, Ramazani J, Rouzer P, ''The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition'', p. 767, Princeton University Press, 2012,

Kannada was the court language of a number of dynasties and empires of South India, Central India and the Deccan Plateau, namely the Kadamba dynasty, Western Ganga dynasty, Nolamba dynasty, Chalukya dynasty, Rashtrakutas, Western Chalukya Empire, Seuna dynasty, kingdom of Mysore, Nayakas of Keladi, Hoysala dynasty and the Vijayanagara Empire.

The Kannada language is written using the Kannada script, which evolved from the 5th-century Kadamba script. Kannada is attested epigraphically for about one and a half millennia and literary Old Kannada flourished during the 9th-century Rashtrakuta Empire.Zvelebil (1973), p. 7 (Introductory, chart) Kannada has an unbroken literary history of around 1200 years.Garg (1992), p. 67 Kannada literature has been presented with eight Jnanapith awards, the most for any Dravidian language and the second highest for any Indian language, and one International Booker Prize. In July 2011, a center for the study of classical Kannada was established as part of the Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysore to facilitate research related to the language.

Geographic distribution

Kannada had 43.7 million native speakers in India at the time of the 2011 census. It is the main language of the state ofKarnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

, where it is spoken natively by million people, or about two thirds of the state's population. There are native Kannada speakers in the neighbouring states of Tamil Nadu ( speakers), Maharashtra (), Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (), Kerala

Kerala ( , ) is a States and union territories of India, state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile ...

() and Goa (). It is also spoken as a second and third language by over 12.9 million non-native speakers in Karnataka.

Kannadigas form Tamil Nadu's third biggest linguistic group; their population is roughly 1.23 million, which is 2.2% of Tamil Nadu's total population.

The Malayalam

Malayalam (; , ) is a Dravidian languages, Dravidian language spoken in the Indian state of Kerala and the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry (Mahé district) by the Malayali people. It is one of ...

spoken by people of Lakshadweep has many Kannada words.

In the United States, there were 35,900 speakers in 2006–2008, a number that had risen to 48,600 by the time of the 2015 census. There are speakers in Canada (according to the 2016 census), 9,700 in Australia (2016 census), 22,000 in Singapore (2018 estimate), and 59,000 in Malaysia (2021 estimate).

Development

Kannada, likeMalayalam

Malayalam (; , ) is a Dravidian languages, Dravidian language spoken in the Indian state of Kerala and the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry (Mahé district) by the Malayali people. It is one of ...

and Tamil, is a South Dravidian language and a descendant of Tamil-Kannada, from which it derives its grammar and core vocabulary. Its history can be divided into three stages: Old Kannada, or ''Haḷegannaḍa'' from 450 to 1200 AD, Middle Kannada (''Naḍugannaḍa'') from 1200 to 1700 and Modern Kannada (''Hosagannaḍa'') from 1700 to the present.

Kannada has been considerably influenced by Sanskrit and Prakrit—in morphology, phonetics, vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. The three principal sources of influence on literary Kannada grammar appear to be Pāṇini's grammar, non-Pāṇinian schools of Sanskrit grammar, particularly ''Katantra'' and ''Sakatayana'' schools, and Prakrit grammar. Literary Prakrit seems to have prevailed in Karnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

since ancient times. Speakers of vernacular Prakrit may have come into contact with Kannada speakers, thus influencing their language, even before Kannada was used for administrative or liturgical purposes. The scholar K. V. Narayana claims that many tribal languages now designated as Kannada dialects could be nearer to the earlier form of the language, with lesser influence from other languages.

The work of the scholar Iravatham Mahadevan indicates that Kannada was already a language of rich spoken tradition by the 3rd century BC. Based on native Kannada words in Prakrit inscriptions of that period, Kannada must have been spoken by a broad and stable population.

Kannada includes many loan words from Sanskrit. Some unaltered loan words () include , , , , and . Some examples of naturalised Sanskrit words () in Kannada are , , and from . Some naturalised words of Prakrit origin in Kannada are derived from , from .

History

Early traces

The earliest Kannada inscriptions are from the middle of the 5th century AD, but there are a number of earlier texts that may have been influenced by the ancestor language of Old Kannada.

Iravatam Mahadevan, author of a work on early Tamil epigraphy, argued that oral traditions in Kannada and Telugu existed much before written documents were produced. Although the rock inscriptions of Ashoka were written in Prakrit, the spoken language in those regions was Kannada as the case may be. He can be quoted as follows:

Kannada linguist, historian and researcher B. A. Viveka Rai and Kannada writer, lyricist, and linguist Doddarangegowda assert that due to the extensive trade relations that existed between the ancient Kannada lands ( Kuntalas, Mahishakas, Punnatas, Mahabanas, Asmakas, etc.) and Greece, Egypt, the Hellenistic and Roman empires and others, there was exchange of people, ideas, literature, etc. and a Kannada book existed in the form of a palm-leaf manuscript in the old Alexandria library which was subsequently lost in the fire. They state that this also proves that the Kannada language and literature must have flourished much before the library was established in between c. 285-48 BC. This document played a vital role in getting the classical status to Kannada from the Indian Central Government. The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated to 250 BC) has been suggested to contain words (''Isila'', meaning to throw, viz. an arrow, etc.) in identifiable Kannada.The word ''Isila'' found in the Ashokan inscription (called the Brahmagiri edict from Karnataka) meaning to shoot an arrow, is a Kannada word, indicating that Kannada was a spoken language in the 3rd century BC (D.L. Narasimhachar in Kamath 2001, p5)

In some 3rd–1st century BC Tamil inscriptions, words of Kannada influence such as ''Naliyura'', ''kavuDi'' and ''posil'' were found. In a 3rd-century AD Tamil inscription there is usage of ''oppanappa vIran''. Here the honorific ''appa'' to a person's name is an influence from Kannada. Another word of Kannada origin is ''taayviru'' and is found in a 4th-century AD Tamil inscription. S. Settar studied the ''sittanavAsal'' inscription of first century AD as also the inscriptions at ''tirupparamkunram'', ''adakala'' and ''neDanUpatti''. The later inscriptions were studied in detail by Iravatham Mahadevan also. Mahadevan argues that the words ''erumi'', ''kavuDi'', and ''tAyiyar'' have their origin in Kannada because Tamil cognates are not available. Settar adds the words ''nADu'' and ''iLayar'' to this list. Mahadevan feels that some grammatical categories found in these inscriptions are also unique to Kannada rather than Tamil. Both these scholars attribute these influences to the movements and spread of Jainas in these regions. These inscriptions belong to the period between the first century BC and fourth century AD. These are some examples that are proof of the early usage of a few Kannada origin words in early Tamil inscriptions before the common era and in the early centuries of the common era.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, wrote about pirates between Muziris and Nitrias ( Netravati River), called Nitran by Ptolemy. He also mentions Barace (Barcelore), referring to the modern port city of Mangaluru, upon its mouth. Many of these are Kannada origin names of places and rivers of the Karnataka coast of the 1st century AD.

The Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 AD) mentions places such as Badiamaioi (Badami), Inde (Indi), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudagal), Petrigala (Pattadakal), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Tiripangalida (Gadahinglai), Soubouttou or Sabatha (Savadi), Banaouase (Banavasi), Thogorum (Tagara), Biathana (Paithan), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Aloe (Ellapur) and Pasage (Palasige). He mentions a Satavahana king Sire Polemaios, who is identified with Sri Pulumayi (or Pulumavi), whose name is derived from the Kannada word for ''Puli'', meaning tiger. Some scholars indicate that the name Pulumayi is actually Kannada's ''Puli Maiyi'' or ''One with the body of a tiger'' indicating native Kannada origin for the Satavahanas. Pai identifies all the 10 cities mentioned by Ptolemy (100–170 AD) as lying between the river Benda (or Binda) or Bhima river in the north and Banaouasei ( Banavasi) in the south, viz. Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Inde ( Indi), Tiripangalida ( Gadhinglaj), Hippokoura ( Huvina Hipparagi), Soubouttou ( Savadi), Sirimalaga ( Malkhed), Kalligeris ( Kalkeri), Modogoulla ( Mudgal), and Petirgala ( Pattadakal)—as being located in Northern Karnataka, which explain the existence of Kannada place names (and the language and culture) in the southern Kuntala region during the reign of Vasishtiputra Pulumayi (–125 AD, i.e., late 1st century – early 2nd century AD) who was ruling from Paithan in the north and his son, prince Vilivaya-kura or Pulumayi Kumara was ruling from Huvina Hipparagi in present Karnataka in the south.

An early ancestor of Kannada (or a related language) may have been spoken by Indian traders in Roman-era Egypt and it may account for the Indian-language passages in the ancient Greek play known as the Charition mime.

The earliest Kannada inscriptions are from the middle of the 5th century AD, but there are a number of earlier texts that may have been influenced by the ancestor language of Old Kannada.

Iravatam Mahadevan, author of a work on early Tamil epigraphy, argued that oral traditions in Kannada and Telugu existed much before written documents were produced. Although the rock inscriptions of Ashoka were written in Prakrit, the spoken language in those regions was Kannada as the case may be. He can be quoted as follows:

Kannada linguist, historian and researcher B. A. Viveka Rai and Kannada writer, lyricist, and linguist Doddarangegowda assert that due to the extensive trade relations that existed between the ancient Kannada lands ( Kuntalas, Mahishakas, Punnatas, Mahabanas, Asmakas, etc.) and Greece, Egypt, the Hellenistic and Roman empires and others, there was exchange of people, ideas, literature, etc. and a Kannada book existed in the form of a palm-leaf manuscript in the old Alexandria library which was subsequently lost in the fire. They state that this also proves that the Kannada language and literature must have flourished much before the library was established in between c. 285-48 BC. This document played a vital role in getting the classical status to Kannada from the Indian Central Government. The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated to 250 BC) has been suggested to contain words (''Isila'', meaning to throw, viz. an arrow, etc.) in identifiable Kannada.The word ''Isila'' found in the Ashokan inscription (called the Brahmagiri edict from Karnataka) meaning to shoot an arrow, is a Kannada word, indicating that Kannada was a spoken language in the 3rd century BC (D.L. Narasimhachar in Kamath 2001, p5)

In some 3rd–1st century BC Tamil inscriptions, words of Kannada influence such as ''Naliyura'', ''kavuDi'' and ''posil'' were found. In a 3rd-century AD Tamil inscription there is usage of ''oppanappa vIran''. Here the honorific ''appa'' to a person's name is an influence from Kannada. Another word of Kannada origin is ''taayviru'' and is found in a 4th-century AD Tamil inscription. S. Settar studied the ''sittanavAsal'' inscription of first century AD as also the inscriptions at ''tirupparamkunram'', ''adakala'' and ''neDanUpatti''. The later inscriptions were studied in detail by Iravatham Mahadevan also. Mahadevan argues that the words ''erumi'', ''kavuDi'', and ''tAyiyar'' have their origin in Kannada because Tamil cognates are not available. Settar adds the words ''nADu'' and ''iLayar'' to this list. Mahadevan feels that some grammatical categories found in these inscriptions are also unique to Kannada rather than Tamil. Both these scholars attribute these influences to the movements and spread of Jainas in these regions. These inscriptions belong to the period between the first century BC and fourth century AD. These are some examples that are proof of the early usage of a few Kannada origin words in early Tamil inscriptions before the common era and in the early centuries of the common era.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, wrote about pirates between Muziris and Nitrias ( Netravati River), called Nitran by Ptolemy. He also mentions Barace (Barcelore), referring to the modern port city of Mangaluru, upon its mouth. Many of these are Kannada origin names of places and rivers of the Karnataka coast of the 1st century AD.

The Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 AD) mentions places such as Badiamaioi (Badami), Inde (Indi), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudagal), Petrigala (Pattadakal), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Tiripangalida (Gadahinglai), Soubouttou or Sabatha (Savadi), Banaouase (Banavasi), Thogorum (Tagara), Biathana (Paithan), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Aloe (Ellapur) and Pasage (Palasige). He mentions a Satavahana king Sire Polemaios, who is identified with Sri Pulumayi (or Pulumavi), whose name is derived from the Kannada word for ''Puli'', meaning tiger. Some scholars indicate that the name Pulumayi is actually Kannada's ''Puli Maiyi'' or ''One with the body of a tiger'' indicating native Kannada origin for the Satavahanas. Pai identifies all the 10 cities mentioned by Ptolemy (100–170 AD) as lying between the river Benda (or Binda) or Bhima river in the north and Banaouasei ( Banavasi) in the south, viz. Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Inde ( Indi), Tiripangalida ( Gadhinglaj), Hippokoura ( Huvina Hipparagi), Soubouttou ( Savadi), Sirimalaga ( Malkhed), Kalligeris ( Kalkeri), Modogoulla ( Mudgal), and Petirgala ( Pattadakal)—as being located in Northern Karnataka, which explain the existence of Kannada place names (and the language and culture) in the southern Kuntala region during the reign of Vasishtiputra Pulumayi (–125 AD, i.e., late 1st century – early 2nd century AD) who was ruling from Paithan in the north and his son, prince Vilivaya-kura or Pulumayi Kumara was ruling from Huvina Hipparagi in present Karnataka in the south.

An early ancestor of Kannada (or a related language) may have been spoken by Indian traders in Roman-era Egypt and it may account for the Indian-language passages in the ancient Greek play known as the Charition mime.

Epigraphy

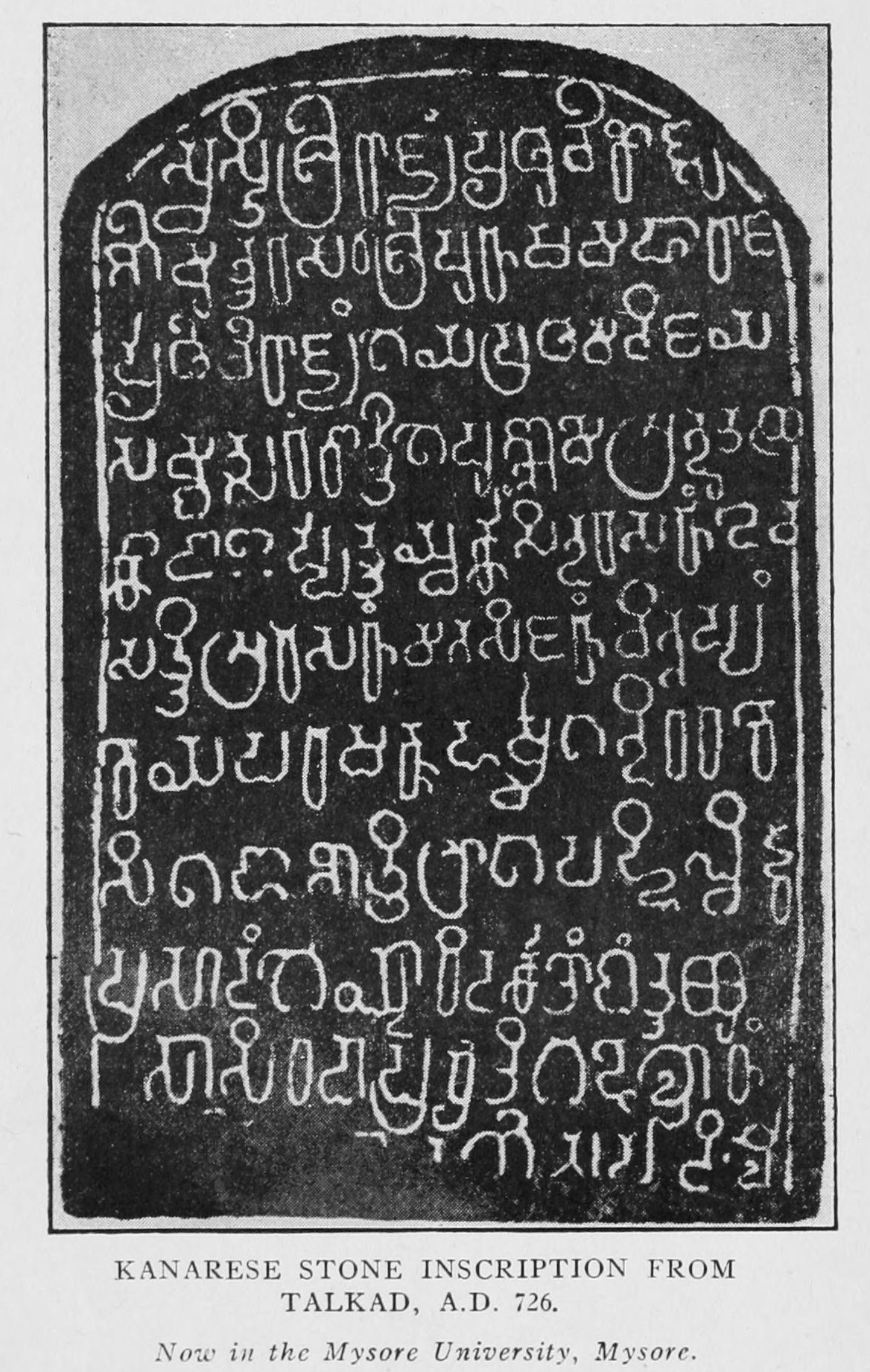

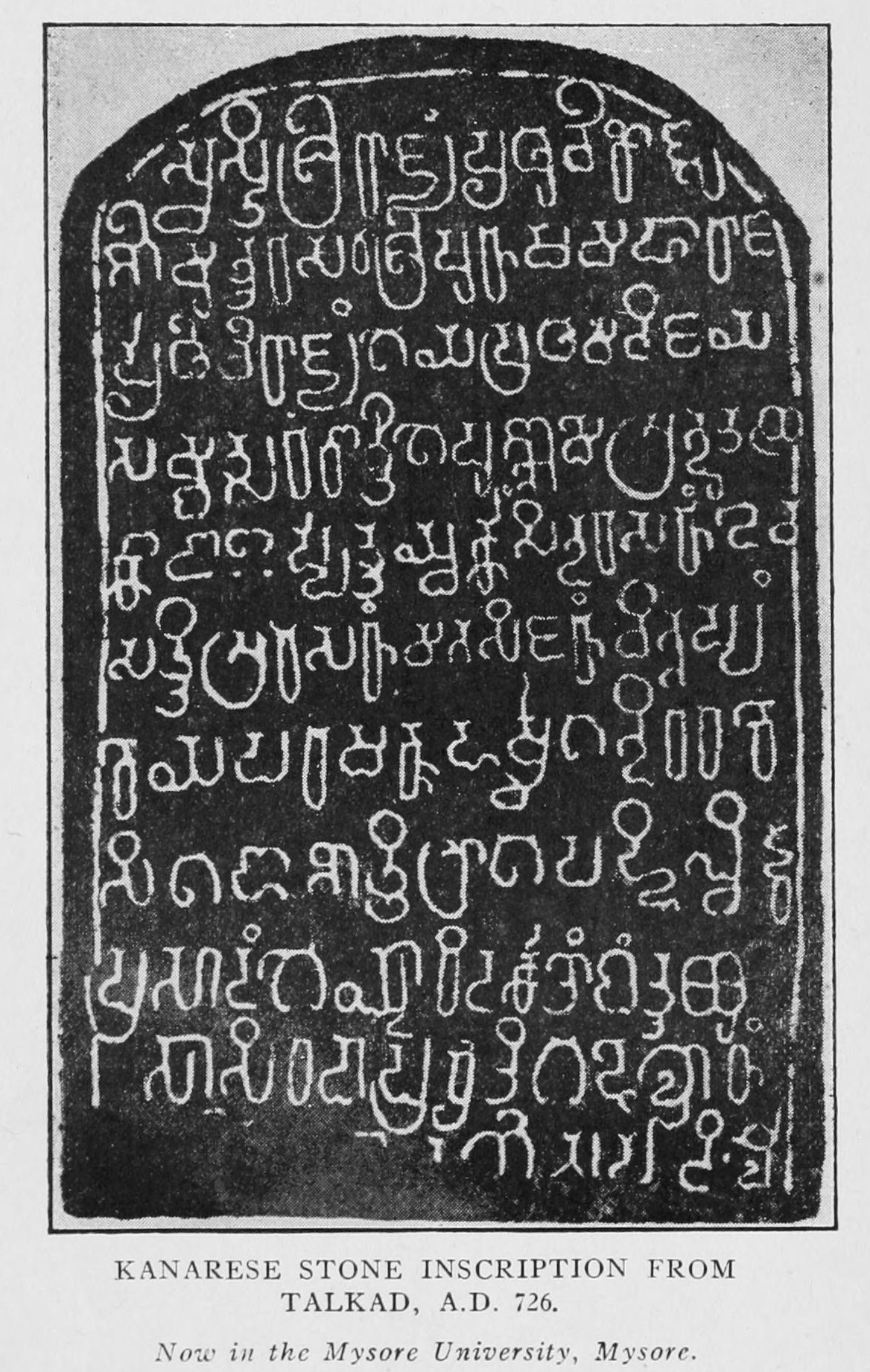

The earliest examples of a full-length Kannada language stone inscription (''śilāśāsana'') containing Brahmi characters with characteristics attributed to those of proto-Kannada in ''Haḷe Kannaḍa'' (''lit'' Old Kannada) script can be found in the Halmidi inscription, usually dated , indicating that Kannada had become an administrative language at that time. The Halmidi inscription provides invaluable information about the history and culture of Karnataka.K. V. Ramesh (1984), p. 10, 55Encyclopaedia of Indian literature vol. 2, Sahitya Akademi (1988), pp. 1717, 1474A report on Halmidi inscription, Kamath (2001), p. 10 A set of five copper plate inscriptions discovered in Mudiyanur, though in the Sanskrit language, is in the Pre- Old Kannada script older than the Halmidi edict date of 450 AD, as per palaeographers. Followed by B. L. Rice, leading epigrapher and historian, K. R. Narasimhan following a detailed study and comparison, declared that the plates belong to the 4th century, i.e., 338 AD. The Kannada Lion balustrade inscription excavated at the Pranaveshwara temple complex at Talagunda near Shiralakoppa of Shivamogga district, dated to 370 AD is now considered the earliest Kannada inscriptions replacing the Halmidi inscription of 450 AD. The 5th century poetic Tamatekallu inscription of Chitradurga and the Siragunda inscription from Chikkamagaluru Taluk of 500 AD are further examples.R. Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 6Rice E. P. (1921), p. 13 Govinda Pai in Bhat (1993), p. 102 Recent reports indicate that the Old Kannada ''Gunabhushitana'' ''Nishadi'' inscription discovered on the Chandragiri hill, Shravanabelagola, is older than Halmidi inscription by about fifty to hundred years and may belong to the period AD 350–400. The noted archaeologist and art historian S. Shettar is of the opinion that an inscription of the Western Ganga King Kongunivarma Madhava (–370) found at Tagarthi (Tyagarthi) in Shikaripura taluk of Shimoga district is of 350 AD and is also older than the Halmidi inscription. Current estimates of the total number of existing epigraphs written in Kannada range from 30,000 by the scholar Sheldon Pollock to over 35,000 by Amaresh Datta of the Sahitya Akademi.Datta, Amaresh; ''Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol. 2'', p. 1717, 1988, Sahitya Akademi, Sheldon Pollock in Dehejia, Vidya; ''The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art'', p.5, chapter:''The body as Leitmotif'', 2013, Columbia University Press, Prior to the Halmidi inscription, there is an abundance of inscriptions containing Kannada words, phrases and sentences, proving its antiquity. The 543 AD Badami cliff inscription of Pulakesi I is an example of a Sanskrit inscription in old Kannada script.Kamath (2001), p58 Kannada inscriptions are discovered in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu,Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (; ; ) is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal and the largest city is Indore, Indore. Other major cities includes Gwalior, Jabalpur, and Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, Sagar. Madhya Pradesh is the List of states and union te ...

and Gujarat in addition to Karnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

. This indicates the spread of the influence of the language over the ages, especially during the rule of large Kannada empires.Kamath (2001), p83

The earliest copper plates inscribed in Old Kannada script and language, dated to the early 8th century AD, are associated with Alupa King Aluvarasa II from Belmannu (the Dakshina Kannada district), and display the double crested fish, his royal emblem.Gururaj Bhat in Kamath (2001), p97 The oldest well-preserved palm leaf manuscript in ''Old Kannada'' is that of ''Dhavala''. It dates to around the 9th century and is preserved in the Jain Bhandar, Mudbidri, Dakshina Kannada district. The manuscript contains 1478 leaves written using ink.

Coins

Some early Kadamba Dynasty coins bearing the Kannada inscription ''Vira'' and ''Skandha'' were found in Satara collectorate.The coins are preserved at the Archaeological Section, Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, Mumbai – Kundangar and Moraes in Moraes (1931), p382 A gold coin bearing three inscriptions of ''Sri'' and an abbreviated inscription of king Bhagiratha's name called ''bhagi'' (c. 390–420 AD) in old Kannada exists.The coin is preserved at the Indian Historical Research Institute, St. Xavier's College, Mumbai – Kundangar and Moraes in Moraes (1938), p 382 A Kadamba copper coin dated to the 5th century AD with the inscription ''Srimanaragi'' in Kannada script was discovered in Banavasi, Uttara Kannada district. Coins with Kannada legends have been discovered spanning the rule of the Western Ganga Dynasty, the Badami Chalukyas, the Alupas, the Western Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas, the Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar Empire, the Kadamba Dynasty of Banavasi, the Keladi Nayakas and the Mysore kingdom, the Badami Chalukya coins being a recent discovery.Kamath (2001), p12, p57 The coins of the Kadambas of Goa are unique in that they have alternate inscription of the king's name in Kannada and Devanagari in triplicate,This shows that the native vernacular of the Goa Kadambas was Kannada – Moraes (1931), p384 a few coins of the Kadambas of Hangal are also available.Two coins of the Hangal Kadambas are preserved at the Royal Asiatic Society, Mumbai, one with the Kannada inscription ''Saarvadhari'' and other with ''Nakara''. Moraes (1931), p385Literature

Old Kannada

The oldest known existing record of Kannada poetry in ''Tripadi'' metre is the Kappe Arabhatta record of the 7th century AD.Kamath (2001), p. 67 '' Kavirajamarga'' by King Nripatunga Amoghavarsha I (850 AD) is the earliest existing literary work in Kannada. It is a writing on literary criticism and poetics meant to standardise various written Kannada dialects used in literature in previous centuries. The book makes reference to Kannada works by early writers such as King Durvinita of the 6th century and Ravikirti, the author of the Aihole record of 636 AD.Sastri (1955), p355 Since the earliest available Kannada work is one on grammar and a guide of sorts to unify existing variants of Kannada grammar and literary styles, it can be safely assumed that literature in Kannada must have started several centuries earlier. An early extant prose work, the ''Vaḍḍārādhane'' (ವಡ್ಡಾರಾಧನೆ) by Shivakotiacharya of 900 AD provides an elaborate description of the life of Bhadrabahu of Shravanabelagola.Sastri (1955), p356 Some early writers of prose and verse mentioned in the ''Kavirajamarga,'' numbering 8–10, stating these are but a few of many, but whose works are lost, are Vimala or Vimalachandra (c. 777), Udaya, Nagarjuna, Jayabandhu, Durvinita (6th century), and poets including Kaviswara, Srivijaya, Pandita, Chandra, Ravi Kirti (c. 634) and Lokapala.R. Narasimhacharya (1934), pp. 2, 4–5, 12–18, 29Warder (1988), pp. 240–241 For fragmentary information on these writers, we can refer the work ''Karnataka Kavi Charite''. Ancient indigenous Kannada literary compositions of (folk) poetry like the ''Chattana'' and ''Bedande'', which preferred to use the ''Desi'' metre, are said to have survived at least until the date of the Kavirajamarga in 850 AD and had their roots in the early Kannada folk literature. These Kannada verse-compositions might have been representative of folk songs containing influence of Sanskrit and Prakrit metrical patterns to some extent. "Kavirajamarga" also discusses earlier composition forms peculiar to Kannada, the "gadyakatha", a mixture of prose and poetry, the "''chattana''" and the "''bedande''", poems of several stanzas that were meant to be sung with the optional use of a musical instrument. Amoghavarsha Nripatunga compares the ''puratana-kavigal'' (old Kannada poets) who wrote the great ''Chattana'' poems in Kannada to the likes of the great Sanskrit poets like Gunasuri, Narayana, Bharavi, Kalidasa, Magha, etc. This Old Kannada work, ''Kavirajamarga'', itself in turn refers to a ''Palagannada'' (Old Kannada) of much ancient times, which is nothing but the Pre-Old Kannada and also warns aspiring Kannada writers to avoid its archaisms, as per R. S. Hukkerikar. Regarding earlier poems in Kannada, the author of "''Kavirajamarga''" states that old Kannada is appropriate in ancient poems but insipid in contemporaneous works as per R. Narasimhacharya. Gunanandi (900 AD), quoted by the grammarian Bhattakalanka and always addressed as ''Bhagawan'' (the adorable), was the author of a logic, grammar and ''sahitya''. Durvinita (529–579 AD), the Ganga king, was the pupil of the author of Sabdavatara, i.e., Devanandi Pujyapada. Durvinita is said to have written a commentary on the difficult 15th ''sarga'' of Bharavi's ''Kiratarjuniya'' in Kannada. Early Kannada writers regularly mention three poets as of especial eminence among their predecessors – Samanta-bhadra, Kavi Parameshthi and Pujyapada. Since later Kannada poets so uniformly name these three as eminent poets, it is probable that they wrote in Kannada also. Samantabhadra is placed in the 2nd century AD by Jain tradition. Old Kannada commentaries on some of his works exist. He was said to have been born in Utkalikagrama and while performing penance in Manuvakahalli, he was attacked by a disease called ''Bhasmaka''. Pujyapada also called Devanandi, was the preceptor of Ganga king Durvinita and belonged to the late 5th to early 6th century AD. Kaviparameshthi probably lived in the 4th century AD. He may possibly be the same as the ''Kaviswara'' referred to in the Kavirajamarga, and the ''Kaviparameswara'' praised by Chavunda Raya (978 AD) and his spiritual teacher, Nemichandra (10th century AD), all the names possibly being only epithets. Kannada works from earlier centuries mentioned in the Kavirajamarga are not yet traced. Some ancient Kannada texts now considered extinct but referenced in later centuries are ''Prabhrita'' (650 AD) by Syamakundacharya, ''Chudamani'' (Crest Jewel—650 AD or earlier) by Srivaradhadeva, also known as Tumbuluracharya, which is a work of 96,000 verse-measures and a commentary on logic (''Tatwartha-mahashastra'').The seventeenth-century Kannada grammarian Bhattakalanka wrote about the ''Chudamani'' as a milestone in the literature of the Kannada language (Sastri (1955), p355)Narasimhacharya (1988), pp 4–5 Other sources date ''Chudamani'' to the 6th century or earlier.6th century Sanskrit poet Dandin praised Srivaradhadeva's writing as "having produced Saraswati from the tip of his tongue, just as Shiva produced the Ganges from the tip of his top knot" (Rice E.P., 1921, pp.25–28)Rice, B.L. (1897), pp. 496–497 An inscription of 1128 AD quotes a couplet by the famous Sanskrit poet Dandin (active 680–720 AD), highly praising Srivaradhadeva, for his Kannada work Chudamani, as having "produced Saraswati (i.e., learning and eloquence) from the tip of his tongue, as Siva produced the Ganges from the tip of his top-knot." Bhattakalanka (1604 CE), the great Kannada grammarian, refers to Srivaradhadeva's Chudamani as the greatest work in Kannada, and as incontestable proof of the scholarly character and value of Kannada literature. This makes Srivaradhadeva's time earlier than the 6th–7th century AD. Other writers, whose works are not extant now but titles of which are known from independent references such as Indranandi's "Srutavatara", Devachandra's "Rajavalikathe", Bhattakalanka's "Sabdanusasana" of 1604, writings of JayakirthiChidananda Murthy in Kamath (1980), p. 50, 67 are Syamakundacharya (650), who authored the "Prabhrita", and Srivaradhadeva (also called Tumubuluracharya, 650 or earlier), who wrote the "Chudamani" ("Crest Jewel"), a 96,000-verse commentary on logic. The ''Karnateshwara Katha'', a eulogy for King Pulakesi II, is said to have belonged to the 7th century; the ''Gajastaka'', a lost "ashtaka" (eight line verse) composition and a work on elephant management by King Shivamara II, belonged to the 8th century,Kamath (2001), p50, p67 this served as the basis for 2 popular folk songs ''Ovanige'' and ''Onakevadu,'' which were sung either while pounding corn or to entice wild elephants into a pit ("''Ovam''"). The ''Chandraprabha-purana'' by Sri Vijaya, a court poet of emperor Amoghavarsha I, is ascribed to the early 9th century. His writing has been mentioned by Vijayanagara poets Mangarasa III and Doddiah (also spelt Doddayya, c. 1550 AD) and praised by Durgasimha (c. 1025 AD).The author and his work were praised by the latter-day poet Durgasimha of AD 1025 (R. Narasimhacharya 1988, p18.) During the 9th century period, the Digambara Jain poet Asaga (or Asoka) authored, among other writings, "Karnata Kumarasambhava Kavya" and "Varadamana Charitra". His works have been praised by later poets, although none of his works are available today. "Gunagankiyam", the earliest known prosody in Kannada, was referenced in a Tamil work dated to the 10th century or earlier ("Yapparungalakkarigai" by Amritasagara). Gunanandi, an expert in logic, Kannada grammar and prose, flourished in the 9th century AD. Around 900 AD, Gunavarma I wrote "Sudraka" and "Harivamsa" (also known as "Neminatha Purana"). In "Sudraka" he compared his patron, Ganga king Ereganga Neetimarga II (c. 907–921 AD), to a noted king called Sudraka. Jinachandra, who is referred to by Sri Ponna (c. 950 AD) as the author of "Pujyapada Charita", had earned the honorific "modern Samantha Bhadra". Tamil Buddhist commentators of the 10th century AD (in the commentary on ''Neminatham'', a Tamil grammatical work) make references that show that Kannada literature must have flourished as early as the BC 4th century. Around the beginning of the 9th century, Old Kannada was spoken from Kaveri to Godavari. The Kannada spoken between the rivers Varada and Malaprabha was the pure well of Kannada undefiled. The late classical period gave birth to several genres of Kannada literature, with new forms of composition coming into use, including ''Ragale'' (a form of blank verse) and meters like ''Sangatya'' and ''Shatpadi''. The works of this period are based on Jain and Hindu principles. Two of the early writers of this period are Harihara and Raghavanka, trailblazers in their own right. Harihara established the ''Ragale'' form of composition while Raghavanka popularised the ''Shatpadi'' (six-lined stanza) meter.Sastri (1955), pp 361–2 A famous Jaina writer of the same period is Janna, who expressed Jain religious teachings through his works.Narasimhacharya (1988), p20 The Vachana Sahitya tradition of the 12th century is purely native and unique in world literature, and the sum of contributions by all sections of society. Vachanas were pithy poems on that period's social, religious and economic conditions. More importantly, they held a mirror to the seed of social revolution, which caused a radical re-examination of the ideas of caste, creed and religion. Some of the important writers of Vachana literature include Basavanna, Allama Prabhu and Akka Mahadevi.Sastri (1955), p361 Emperor Nripatunga Amoghavarsha I of 850 AD recognised that the Sanskrit style of Kannada literature was ''Margi'' (formal or written form of language) and ''Desi'' (folk or spoken form of language) style was popular and made his people aware of the strength and beauty of their native language Kannada. In 1112 AD, Jain poet Nayasena of Mulugunda, Dharwad district, in his Champu work ''Dharmamrita'' (ಧರ್ಮಾಮೃತ), a book on morals, warns writers from mixing Kannada with Sanskrit by comparing it with mixing of clarified butter and oil. He has written it using very limited Sanskrit words that fit with idiomatic Kannada. In 1235 AD, Jain poet Andayya, wrote ''Kabbigara Kava''- ಕಬ್ಬಿಗರ ಕಾವ (Poet's Defender), also called ''Sobagina Suggi'' (Harvest of Beauty) or ''Madana-Vijaya and'' ''Kavana-Gella'' (Cupid's Conquest)'','' a ''Champu'' work in pure Kannada using only indigenous (''desya'') Kannada words and the derived form of Sanskrit words – ''tadbhavas'', without the admixture of Sanskrit words. He succeeded in his challenge and proved wrong those who had advocated that it was impossible to write a work in Kannada without using Sanskrit words. Andayya may be considered as a protector of Kannada poets who were ridiculed by Sanskrit advocates. Thus Kannada is the only Dravidian language that is not only capable of using only native Kannada words and grammar in its literature (like Tamil), but also use Sanskrit grammar and vocabulary (like Telugu, Malayalam, Tulu, etc.) The Champu style of literature of mixing poetry with prose owes its origins to the Kannada language and was later incorporated by poets into Sanskrit and other Indian languages.Rice, Edward. P (1921), "A History of Kannada Literature", Oxford University Press, 1921: 14–15Middle Kannada

During the period between the 15th and 18th centuries, Hinduism had a great influence on Middle Kannada (''Naḍugannaḍa''- ನಡುಗನ್ನಡ) language and literature. Kumara Vyasa, who wrote the ''Karṇāṭa Bhārata Kathāman̄jari'' (ಕರ್ಣಾಟ ಭಾರತ ಕಥಾಮಂಜರಿ), was arguably the most influential Kannada writer of this period. His work, entirely composed in the native ''Bhamini Shatpadi'' (hexa-meter), is a sublime adaptation of the first ten books of the Mahabharata.Sastri (1955), p364 During this period, the Sanskritic influence is present in most abstract, religious, scientific and rhetorical terms."Literature in all Dravidian languages owes a great deal to Sanskrit, the magic wand whose touch raised each of the languages from a level of patois to that of a literary idiom". (Sastri 1955, p309)Takahashi, Takanobu. 1995. Tamil love poetry and poetics. Brill's Indological library, v. 9. Leiden: E.J. Brill, p16,18"The author endeavours to demonstrate that the entire Sangam poetic corpus follows the "Kavya" form of Sanskrit poetry"-Tieken, Herman Joseph Hugo. 2001. Kāvya in South India: old Tamil Caṅkam poetry. Groningen: Egbert Forsten During this period, several Hindi and Marathi words came into Kannada, chiefly relating to feudalism and militia. Hindu saints of the Vaishnava sect such as Kanakadasa, Purandaradasa, Naraharitirtha, Vyasatirtha, Sripadaraya, Vadirajatirtha, Vijaya Dasa, Gopala Dasa, Jagannatha Dasa, Prasanna Venkatadasa produced devotional poems in this period.Sastri (1955), pp 364–365 Kanakadasa's ''Rāmadhānya Charite'' (ರಾಮಧಾನ್ಯ ಚರಿತೆ) is a rare work, concerning with the issue of class struggle.The writing exalts the grain Ragi above all other grains that form the staple foods of much of modern Karnataka (Sastri 1955, p365) This period saw the advent of '' Haridasa Sahitya'' (''lit'' Dasa literature), which made rich contributions to '' Bhakti'' literature and sowed the seeds of Carnatic music. Purandara Dasa is widely considered the ''Father of Carnatic music''.Iyer (2006), p93Sastri (1955), p365Modern Kannada

The Kannada works produced from the 19th century make a gradual transition and are classified as ''Hosagannaḍa'' or Modern Kannada. Most notable among the modernists was the poet Nandalike Muddana whose writing may be described as the "Dawn of Modern Kannada", though generally, linguists treat ''Indira Bai'' or ''Saddharma Vijayavu'' by Gulvadi Venkata Raya as the first literary works in Modern Kannada. The first modernmovable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable Sort (typesetting), components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric charac ...

printing of "Canarese" appears to be the ''Canarese Grammar'' of Carey printed at Serampore in 1817, and the " Bible in Canarese" of John Hands in 1820. The first novel printed was John Bunyan's '' Pilgrim's Progress'', along with other texts including ''Canarese Proverbs'', ''The History of Little Henry and his Bearer'' by Mary Martha Sherwood, Christian Gottlob Barth's ''Bible Stories'' and "a Canarese hymn book."

Modern Kannada in the 20th century has been influenced by many movements, notably ''Navodaya'', ''Navya'', ''Navyottara'', ''Dalita'' and ''Bandaya''. Contemporary Kannada literature has been highly successful in reaching people of all classes in society. Further, Kannada has produced a number of prolific and renowned poets and writers such as Kuvempu, Bendre, and V K Gokak. Works of Kannada literature have received eight Jnanpith awards, the highest number awarded to any Indian language.

Dictionaries

Kannada–Kannada dictionary has existed in Kannada along with ancient works of Kannada grammar. The oldest available Kannada dictionary was composed by the poet 'Ranna' called 'Ranna Kanda' (ರನ್ನ ಕಂದ) in 996 AD. Other dictionaries are ' Abhidhana Vastukosha' (ಅಭಿದಾನ ವಾಸ್ತುಕೋಶ) by Nagavarma (1045 AD), 'Amarakoshada Teeku' (ಅಮರಕೋಶದ ತೀಕು) by Vittala (1300), 'Abhinavaabhidaana' (ಅಭಿನವಾಭಿದಾನ) by Abhinava Mangaraja (1398 AD) and many more. A Kannada–English dictionary consisting of more than 70,000 words was composed by Ferdinand Kittel. G. Venkatasubbaiah edited the first modern Kannada–Kannada dictionary, a 9,000-page, 8-volume series published by the Kannada Sahitya Parishat. He also wrote a Kannada–English dictionary and a ''kliṣtapadakōśa'' (ಕ್ಲಿಷ್ಟಪಾದಕೋಶ), a dictionary of difficult words.Dialects

There is also a considerable difference between the spoken and written forms of the language. Spoken Kannada tends to vary from region to region. The written form is more or less consistent throughout Karnataka. The Ethnologue reports "about 20 dialects" of Kannada. Among them are Kundagannada (spoken exclusively in Kundapura, Brahmavara, Bynduru and Hebri), Nador-Kannada (spoken by Nadavaru), Havigannada (spoken mainly by Havyaka Brahmins), Are Bhashe (spoken by Gowda community mainly in Madikeri and Sullia region of Dakshina Kannada), Malenadu Kannada (Sakaleshpur, Coorg, Shimoga, Chikmagalur), Sholaga, Gulbarga Kannada, Dharawad Kannada etc. All of these dialects are influenced by their regional and cultural background. The one million Komarpants in and around Goa speak their own dialect of Kannada, known as Halegannada. They are settled throughout Goa state, throughout Uttara Kannada district and Khanapur taluk of Belagavi district, Karnataka. The Halakki Vokkaligas of Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka speak in their own dialect of Kannada called Halakki Kannada or Achchagannada. Their population estimate is about 75,000.

Ethnologue also classifies a group of four languages related to Kannada, which are, besides Kannada proper, Badaga, Holiya, Kurumba and Urali. The Golars or Golkars are a nomadic herdsmen tribe present in Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Seoni and Balaghat districts of Maharashtra and

There is also a considerable difference between the spoken and written forms of the language. Spoken Kannada tends to vary from region to region. The written form is more or less consistent throughout Karnataka. The Ethnologue reports "about 20 dialects" of Kannada. Among them are Kundagannada (spoken exclusively in Kundapura, Brahmavara, Bynduru and Hebri), Nador-Kannada (spoken by Nadavaru), Havigannada (spoken mainly by Havyaka Brahmins), Are Bhashe (spoken by Gowda community mainly in Madikeri and Sullia region of Dakshina Kannada), Malenadu Kannada (Sakaleshpur, Coorg, Shimoga, Chikmagalur), Sholaga, Gulbarga Kannada, Dharawad Kannada etc. All of these dialects are influenced by their regional and cultural background. The one million Komarpants in and around Goa speak their own dialect of Kannada, known as Halegannada. They are settled throughout Goa state, throughout Uttara Kannada district and Khanapur taluk of Belagavi district, Karnataka. The Halakki Vokkaligas of Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka speak in their own dialect of Kannada called Halakki Kannada or Achchagannada. Their population estimate is about 75,000.

Ethnologue also classifies a group of four languages related to Kannada, which are, besides Kannada proper, Badaga, Holiya, Kurumba and Urali. The Golars or Golkars are a nomadic herdsmen tribe present in Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Seoni and Balaghat districts of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (; ; ) is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal and the largest city is Indore, Indore. Other major cities includes Gwalior, Jabalpur, and Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, Sagar. Madhya Pradesh is the List of states and union te ...

speak the Golari dialect of Kannada, which is identical to the Holiya dialect spoken by their tribal offshoot Holiyas present in Seoni, Nagpur and Bhandara of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. There were around 3,600 speakers of this dialect as per the 1901 census. Matthew A. Sherring describes the Golars and Holars as a pastoral tribe from the Godavari banks established in the districts around Nagpur, in the stony tracts of Ambagarh, forests around Ramplee and Sahangadhee. Along the banks of the Wainganga, they dwell in the Chakurhaitee and Keenee subdivisions. The Kurumvars of Chanda district of Maharashtra, a wild pastoral tribe, 2,200 in number as per the 1901 census, spoke a Kannada dialect called Kurumvari. The Kurumbas or Kurubas, a nomadic shepherd tribe were spread across the Nilgiris, Coimbatore, Salem, North and South Arcots, Trichinopoly, Tanjore

Thanjavur (), also known as Thanjai, previously known as Tanjore,#Pletcher, Pletcher 2010, p. 195 is a city in the India, Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the 12th biggest city in Tamil Nadu. Thanjavur is an important center of South Indian c ...

and Pudukottai of Tamil Nadu, Cuddapah and Anantapur

Anantapur, officially Anantapuramu, is a city in Anantapur district of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It is the mandal headquarters of Anantapuru Tehsil, mandal and also the divisional headquarters of Anantapur revenue division. The city ...

of Andhra Pradesh, Malabar and Cochin of Kerala

Kerala ( , ) is a States and union territories of India, state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile ...

and South Canara and Coorg of Karnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

and spoke the Kurumba Kannada dialect. The Kurumba and Kurumvari dialect (both closely related with each other) speakers were estimated to be around 11,400 in total as per the 1901 census. There were about 34,250 Badaga speakers as per the 1901 census.

Nasik district of Maharashtra has a distinct tribe called 'Hatkar Kaanadi' people who speak a Kannada (Kaanadi) dialect with lot of old Kannada words. Per Chidananda Murthy, they are the native people of Nasik from ancient times, which shows that North Maharashtra's Nasik area had Kannada population 1000 years ago. Kannada speakers formed 0.12% of Nasik district's population as per 1961 census.

Writing system

The language uses forty-nine phonemic letters, divided into three groups: ''swaragalu'' (vowels – thirteen letters); ''vyanjanagalu'' (consonants – thirty-four letters); and ''yogavaahakagalu'' (neither vowel nor consonant – two letters: '' anusvara'' and '' visarga'' ). The character set is almost identical to that of other Indian languages. The Kannada script is almost entirely phonetic, but for the sound of a "half n" (which becomes a half m). The number of written symbols, however, is far more than the forty-nine characters in the alphabet, because different characters can be combined to form ''compound'' characters ''(ottakshara)''. Each written symbol in the Kannada script corresponds with one syllable, as opposed to one phoneme in languages like English—the Kannada script is syllabic.Phonology

Consonants

* Most consonants can be geminated. * Aspirated consonants very rarely occur in native vocabulary only in a few numerals like the number 9 and 80, which can be written with a /bʱ/, as in "ಒಂಭತ್ತು", ''ಎಂಭತ್ತು''. However, it is usually written with a /b/, as in "ಒಂಬತ್ತು", ''ಎಂಬತ್ತು''. * The aspiration of consonants depends entirely on the speaker and many do not do it in non-formal situations. * The alveolar trill /r/ may be pronounced as an alveolar tap � * The voiceless retroflex sibilant /ʂ/ is commonly pronounced as a /ʃ/ except in consonant clusters with retroflex consonants. * There are also the consonants /f, z/ which occur in recent English and Perso-Arabic loans but they may be replaced by the consonants /pʰ, dʒ/ respectively by speakers. Additionally, Kannada included the following phonemes, which dropped out of common usage in the 12th and 18th century respectively: * // ಱ (ṟ), the alveolar trill. * // ೞ (ḻ), the retroflex central approximant. Old Kannada had an archaic phoneme /ɻ/ under retroflexes in early inscriptions that merged with /ɭ/ and it maintained the contrast between /r/ (< PD ∗ṯ) and /ɾ/ from (< PD ∗r). Both merged in Medieval Kannada. In old Kannada at around 10th-14th century, most of the initial /p/ debuccalised into a /h/ e.g. OlKn. pattu, MdKn. hattu "ten". Historically, the Tamil-Malayalam languages and, independently, Telugu, phonemically palatalised /k/ before a front vowel; Kannada never developed such phonemic palatalisation (cf. Kn. ಕಿವಿ , Ta. செவி , Te. చెవి "ear"); however, ''phonetically'', Kannada speakers frequently palatalise velar consonants before front vowels, for example, realising ಕಿವಿ "ear" as and ಗಿಳಿ "parrot" as .Vowels

* and are phonetically central . may be as open as () or higher . * The vowels /i iː e eː/ may be preceded by /j/ and the vowels /u uː o oː/ may be preceded by /ʋ/ when they are in an initial position. * The short vowels /a i u e o/, when in an initial or a medial position tend to be pronounced as � ɪ ʊ ɛ ɔ In a final position, this phenomenon occurs less frequently. * /æː/ occurs in English loans but can be switched with /aː/ or /ja:/. At around the 8th century, Kannada raised the vowels e, o to i, u when before a short consonant and a high vowel, before written literature emerged in the language, e.g. Kn. kivi, Ta. cevi, Te. cevi "ear".Colloquial speech

Sources: * Initial i/e have a y- onset and w- for u/o. * In many dialects, e/o gets lowered to �, ɔwhen followed by non high vowels. Some dialects have /a/ as �when a high vowel comes after it and elsewhere. * Final -e's become i's, in the south its mostly with verbs but in the north it happens everywhere, eg. bere > bære > bæri. This along with the previous change can create some surface minimal pairs, eg. æ:ɖə"don't" vs e:ɖə"ask!" (conj of /be:ɖu/).Grammar

The canonical word order of Kannada is SOV (subject–object–verb), typical of Indian languages. Kannada is a highly inflected language with three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter or common) and two numbers (singular and plural). It is inflected for gender, number and tense, among other things. The first available Kannada book, a treatise on poetics, rhetoric and basic grammar is the '' Kavirajamarga'' from 850 AD. The most influential account of Kannada grammar is Keshiraja's '' Shabdamanidarpana'' (c. 1260 AD).''Studies in Indian History, Epigraphy, and Culture'' – By Govind Swamirao Gai, pp. 315''A Grammar of the Kannada Language''. F. Kittel (1993), p. 3. The earlier grammatical works include portions of '' Kavirajamarga'' (a treatise on ''alańkāra'') of the 9th century, and ''Kavyavalokana'' and ''Karnatakabhashabhushana'' (both authored by Nagavarma II in the first half of the 12th century).Compound bases

Compound bases, called ''samāsa'' in Kannada, are a set of two or more words compounded together. There are several types of compound bases, based on the rules followed for compounding. The types of compound bases or samāsas: tatpurusha, karmadhāraya, dvigu, bahuvreehi, anshi, dvandva, kriya and gamaka samāsa. Examples: ''taṅgāḷi'', ''hemmara'', ''kannusanne''.Pronouns

In many ways the third-person pronouns are more like demonstratives than like the other pronouns. They are pluralised like nouns and the first- and second-person pronouns have different ways to distinguish number.Significance to Modern Linguistics

While an early account of Kannada's grammar is available in '' Shabdamanidarpana,'' it has played a central role in the modern linguistics thanks to its unique semantic and syntactic properties that have been significant to studies of language acquisition and innateness. Jeff Lidz is a significant Western linguist to have studied Kannada. His investigations found at least two properties of Kannada to be very impactful in developing contemporary understandings of language acquisition. The first observation was that Kannada has a causative morpheme (like -''ify'' for English, in ''personify'' or ''deify''), which appears whenever a verb with causative meaning is expressed. This was significant, because it allowed him to test whether an observation of English-learning infants, that they worked out novel verb meanings based on the number of overt NPs they took, applied cross-linguistically. Given that the presence of the aforementioned causative morpheme would be a more obvious and reliable indicator for differentiating meanings, Kannada was a perfect language to test this observation; Lidz et al. (2003) found that Kannada-learning infants relied ''more heavily'' on the number of overt NPs than the presence of the causative morpheme. This has been used by generativists and UG nativists to argue that verb meaning acquisition based on syntactic bootstrapping is language universal and innate. The second property of major significance to develops in modern linguistic understandings lies in the fact that in Kannada negation comes at the end of the sentence and the quantified object linearly precedes it. This means there is no capacity for confounding linear order and hierarchical relations, as there is in English. This can be used to test whether the observation for English-speaking infants of considering hierarchical organisation more than linear order when deciding scope ambiguity is cross-linguistic, or just a product of English's confounded linear order. Specifically, analysing the sentence "I didn't read two books" (in Kannada), if what matters is linear order, Kannada speaking children's preferred interpretation would be one where 'two books' has wider scope than negation (i.e., there are two books I did not read), and if what matters is hierarchical organisation, their preferred interpretation would be the opposite (i.e., that it is not the case that I read two books). Lidz and Musolino (2002) found that they prefer the second, hierarchical interpretation, just like English-speaking children. This has been used to argue that infants universally represent sentences not as mere strings of adjacent words, but as hierarchical objects, a regular talking point among Chomskyans and nativists.Sample text

The given sample text is Article 1 from the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.English

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.Kannada

Romanisation (ISO 15919)

Ellā mānavaru svatantrarāgiyē huṭṭiddāre hāgu ghanate mattu adhikāragaḷalli samānarāgiddāre. Tiḷivu mattu antaḥsākṣīyannu paḍedavarāddarinda avaru obbarigobbaru sahōdara bhāvadinda naḍedukoḷḷabēku.IPA

See also

* Bangalore Kannada * Gokak agitation * Hermann Mögling * Kannada cinema * Kannada dialects * Kannada flag * Kannada in computing * Kuvempu * List of Kannada-language radio stations * List of Karnataka literature * List of languages by number of native speakers in India * Siribhoovalaya * Timeline of Karnataka * YakshaganaReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * George M. Moraes (1931), The Kadamba Kula, A History of Ancient and Medieval Karnataka, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras, 1990 * * Robert Zydenbos (2020): ''A Manual of Modern Kannada.'' Heidelberg: XAsia BooksOpen Access publication in PDF format

External links

*English to Kannada Dictionary, Kannada to English Dictionary PDF

{{Sister bar, Kannada, auto=1, voy=Kannada_phrasebook, wikt=Kannada language, iw=kn Languages attested from the 5th century Classical Language in India Dravidian languages Languages of Andhra Pradesh Languages of Karnataka Languages of Kerala Languages of Tamil Nadu Languages of Telangana Languages written in Brahmic scripts Official languages of India