Jules Ferry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

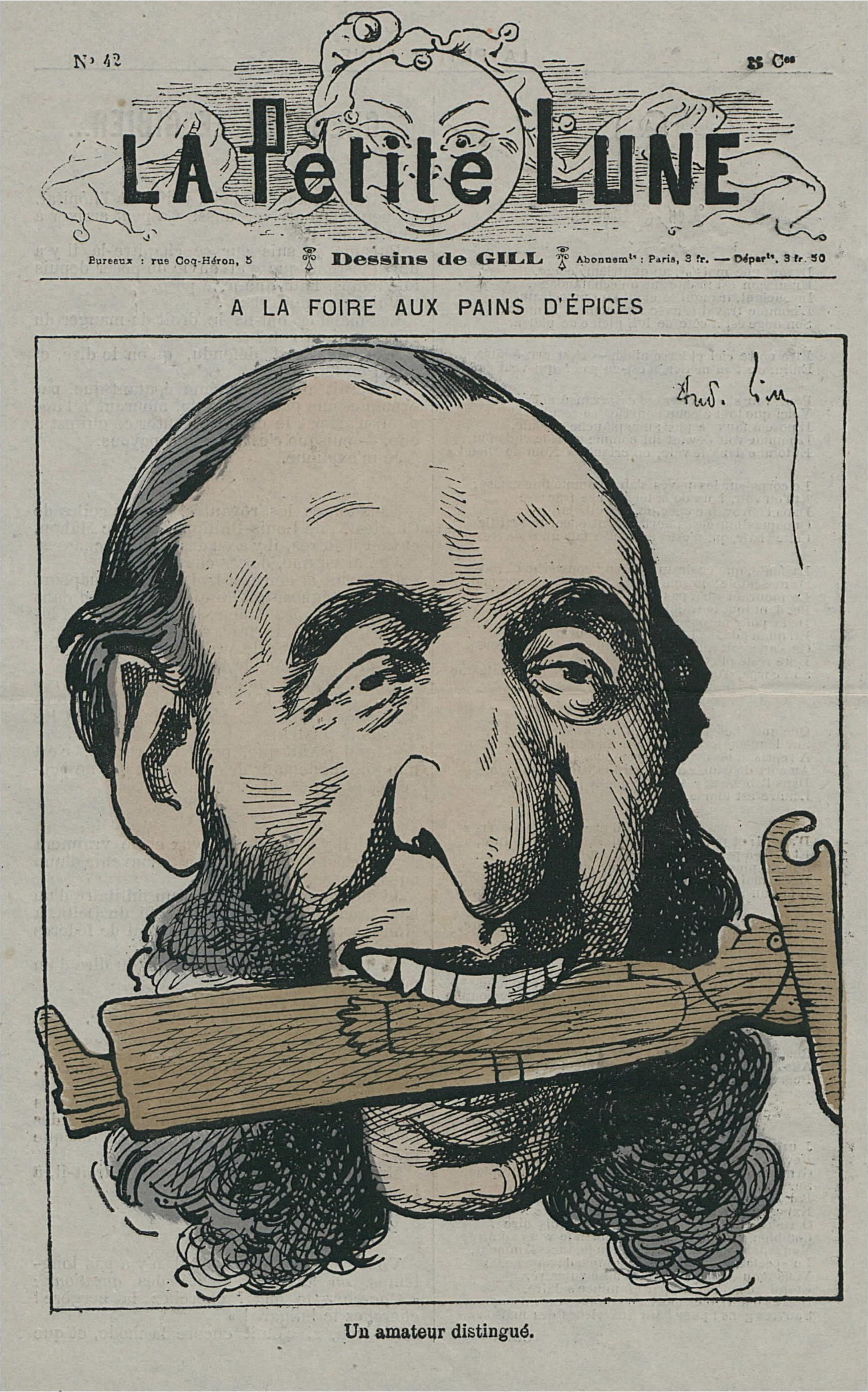

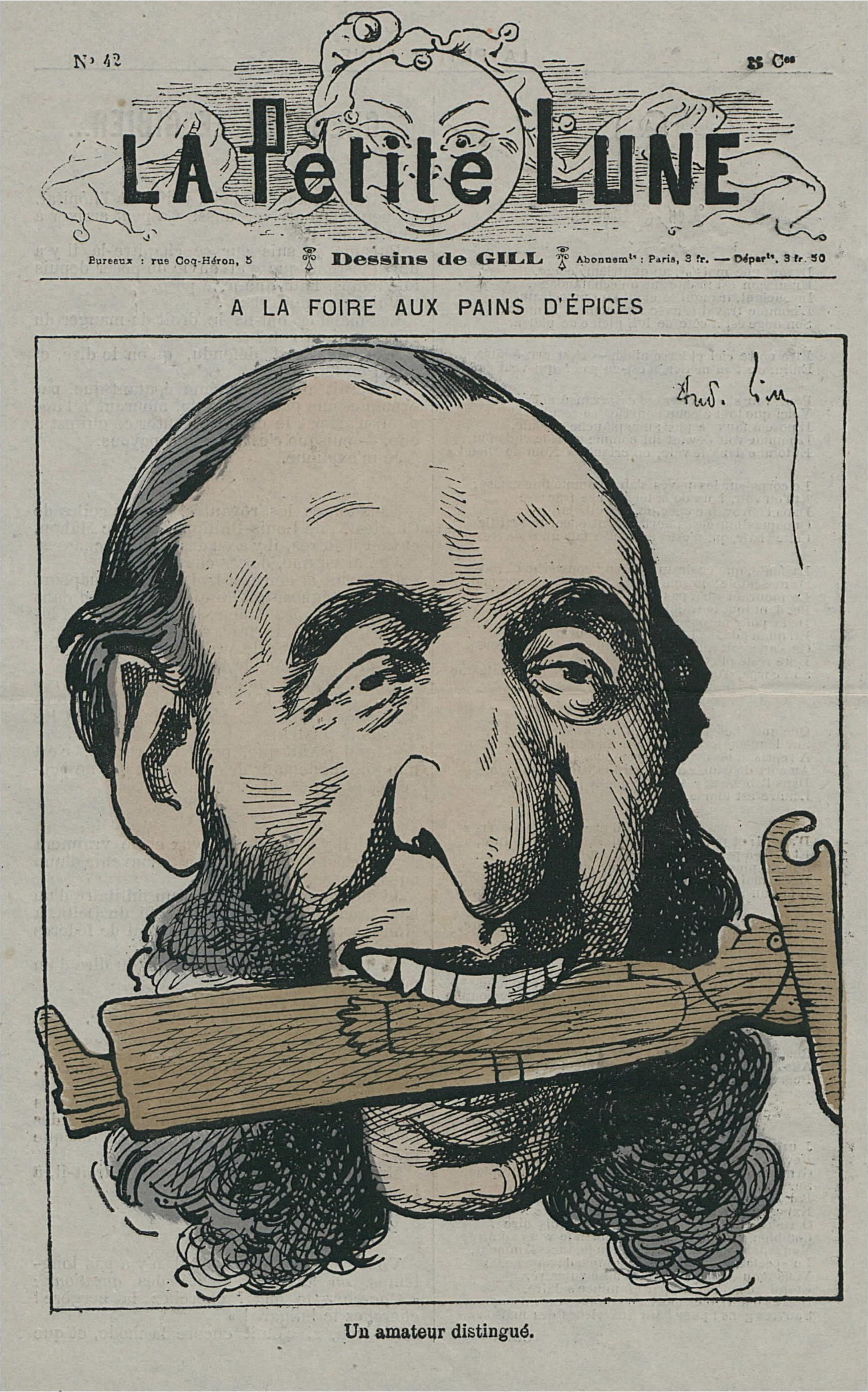

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion. Under the Third Republic, Ferry made primary education free and compulsory through several

After the military defeat of France by Prussia in 1870, Ferry formed the idea of acquiring a great colonial empire, principally for the sake of economic exploitation.

In 1882 Jules Ferry, as Minister of Public Instruction, decided to create a mission to explore the Regency of Tunisia.

The expedition was headed by the botanist Ernest Cosson and included the botanist Napoléon Doumet-Adanson and other naturalists.

In 1884 a geological section under Georges Rolland was added to the Tunisian Scientific Exploration Mission.

Rolland was assisted by Philippe Thomas from 1885 and by Georges Le Mesle in 1887.

In a speech on the colonial empire before the Chamber of Deputies on 28 March 1884, he declared that "it is a right for the superior races, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races." Ferry directed the negotiations which led to the establishment of a French

After the military defeat of France by Prussia in 1870, Ferry formed the idea of acquiring a great colonial empire, principally for the sake of economic exploitation.

In 1882 Jules Ferry, as Minister of Public Instruction, decided to create a mission to explore the Regency of Tunisia.

The expedition was headed by the botanist Ernest Cosson and included the botanist Napoléon Doumet-Adanson and other naturalists.

In 1884 a geological section under Georges Rolland was added to the Tunisian Scientific Exploration Mission.

Rolland was assisted by Philippe Thomas from 1885 and by Georges Le Mesle in 1887.

In a speech on the colonial empire before the Chamber of Deputies on 28 March 1884, he declared that "it is a right for the superior races, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races." Ferry directed the negotiations which led to the establishment of a French

new laws

The New Laws ( Spanish: ''Leyes Nuevas''), also known as the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians ( Spanish: ''Leyes y ordenanzas nuevamente hechas por su Majestad para la gobernación de las Indias y buen ...

. However, he was forced to resign following the Sino-French War

The Sino-French War (, french: Guerre franco-chinoise, vi, Chiến tranh Pháp-Thanh), also known as the Tonkin War and Tonquin War, was a limited conflict fought from August 1884 to April 1885. There was no declaration of war. The Chinese arm ...

in 1885 due to his unpopularity and public opinion against the war.

Biography

Early life and family

Ferry was born Saint-Dié, in the Vosges department, to Charles-Édouard Ferry, alawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicit ...

from a family that had established itself in Saint-Dié as bellmakers, and Adélaïde Jamelet. His paternal grandfather, François-Joseph Ferry, was mayor of Saint-Dié through the Consulate

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of diplomatic mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth co ...

and the First Empire First Empire may refer to:

*First British Empire, sometimes used to describe the British Empire between 1583 and 1783

*First Bulgarian Empire (680–1018)

*First French Empire (1804–1814/1815)

* First German Empire or "First Reich", sometimes use ...

. He studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to various newspapers, particularly to ''Le Temps

''Le Temps'' ( literally "The Time") is a Swiss French-language daily newspaper published in Berliner format in Geneva by Le Temps SA. It is the sole nationwide French-language non-specialised daily newspaper of Switzerland. Since 2021, it has ...

''. He attacked the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930s ...

with great violence, directing his opposition especially against Baron Haussmann, prefect of the Seine department

Seine was the former department of France encompassing Paris and its immediate suburbs. It is the only enclaved department of France at that time. Its prefecture was Paris and its INSEE number was 75. The Seine department was disbanded in 1968 ...

. A series of his articles in ''Le Temps'' was later republished as ''The Fantastic Tales of Haussmann'' (1868).

Political rise

Elected republican deputy for Paris in 1869, he protested against the declaration of war with Germany, and on 6 September 1870 was appointed prefect of the Seine by the Government of National Defense. In this position, he had the difficult task of administering Paris during the siege, and after theParis Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defende ...

was obliged to resign (5 June 1871). From 1872 to 1873 he was sent by Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

as minister to Athens, but returned to the chamber as deputy for the Vosges, and became one of the leaders of the Opportunist Republicans

The Moderates or Moderate Republicans (french: Républicains modérés), pejoratively labeled Opportunist Republicans (), was a French political group active in the late 19th century during the Third French Republic. The leaders of the group inc ...

. When the first republican ministry was formed under W. H. Waddington on 4 February 1879, he was one of its members, and continued in the ministry until 30 March 1885, except for two short interruptions (from 10 November 1881 to 30 January 1882, and from 29 July 1882 to 21 February 1883), first as minister of education and then as minister of foreign affairs. A leader of the Opportunist Republicans

The Moderates or Moderate Republicans (french: Républicains modérés), pejoratively labeled Opportunist Republicans (), was a French political group active in the late 19th century during the Third French Republic. The leaders of the group inc ...

faction, he was twice premier (1880–1881 and 1883–1885). He was an active Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

initiated on 8 July 1875, in "La Clémante amitiée" lodge in Paris the same day as Émile Littré

Émile Maximilien Paul Littré (; 1 February 18012 June 1881) was a French lexicographer, freemason and philosopher, best known for his ''Dictionnaire de la langue française'', commonly called .

Biography

Littré was born in Paris. His father, ...

. He became a member of the "Alsace-Lorraine" Lodge founded in Paris in 1782.

School reforms

Two important works are associated with his administration: the non-clerical organization of public education, and the major colonial expansion of France. Ferry believed the path to a modernized and prosperous France lay in the triumph of reason over religion. School reforms were a key part of his plan. Following the republican program, he proposed to destroy the influence of the clergy in universities and found his own system of republican schooling. He reorganized the committee of public education (law of 27 February 1880) and proposed a regulation for the conferring of university degrees, which, though rejected, aroused violent polemics because the 7th article took away from the unauthorized religious orders the right to teach. He finally succeeded in passing his eponymous laws of 16 June 1881 and 28 March 1882, which made primary education in France free, non-clerical ( laïque) and mandatory. In higher education, the number of professors called the "Republic's black hussars" (french: hussards noirs de la République, links=no) because of their Republican support, doubled under his ministry.Colonial expansion

After the military defeat of France by Prussia in 1870, Ferry formed the idea of acquiring a great colonial empire, principally for the sake of economic exploitation.

In 1882 Jules Ferry, as Minister of Public Instruction, decided to create a mission to explore the Regency of Tunisia.

The expedition was headed by the botanist Ernest Cosson and included the botanist Napoléon Doumet-Adanson and other naturalists.

In 1884 a geological section under Georges Rolland was added to the Tunisian Scientific Exploration Mission.

Rolland was assisted by Philippe Thomas from 1885 and by Georges Le Mesle in 1887.

In a speech on the colonial empire before the Chamber of Deputies on 28 March 1884, he declared that "it is a right for the superior races, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races." Ferry directed the negotiations which led to the establishment of a French

After the military defeat of France by Prussia in 1870, Ferry formed the idea of acquiring a great colonial empire, principally for the sake of economic exploitation.

In 1882 Jules Ferry, as Minister of Public Instruction, decided to create a mission to explore the Regency of Tunisia.

The expedition was headed by the botanist Ernest Cosson and included the botanist Napoléon Doumet-Adanson and other naturalists.

In 1884 a geological section under Georges Rolland was added to the Tunisian Scientific Exploration Mission.

Rolland was assisted by Philippe Thomas from 1885 and by Georges Le Mesle in 1887.

In a speech on the colonial empire before the Chamber of Deputies on 28 March 1884, he declared that "it is a right for the superior races, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races." Ferry directed the negotiations which led to the establishment of a French protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

in Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

(1881), prepared the treaty of 17 December 1885 for the occupation of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

; directed the exploration of the Congo and of the Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesAnnam and

The key to understanding Ferry's unique position in Third Republic history is that until his political critic,

The key to understanding Ferry's unique position in Third Republic history is that until his political critic,

BibNum

(for English version, click 'Télécharger') * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ferry, Jules 1832 births 1893 deaths People from Saint-Dié-des-Vosges Politicians from Grand Est Opportunist Republicans Prime Ministers of France French Foreign Ministers Members of the 4th Corps législatif of the Second French Empire Members of the National Assembly (1871) Members of the 1st Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 3rd Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 4th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic French Senators of the Third Republic Senators of Vosges (department) Presidents of the Senate (France) Ambassadors of France to Greece 19th-century French diplomats Mayors of Paris French Freemasons University of Paris alumni French people of the Franco-Prussian War People of the Sino-French War People of the Tonkin campaign

Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includ ...

in what became Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

.

The last endeavor led to a war with Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

China, which had a claim of suzerainty over the two provinces. The excitement caused in Paris by the sudden retreat of the French troops from Lạng Sơn during this war led to the Tonkin Affair: his violent denunciation by Clemenceau and other radicals, and his downfall on 30 March 1885. Although the treaty of peace with the Chinese Empire (9 June 1885), in which the Qing dynasty ceded suzerainty of Annam and Tonkin to France, was the work of his ministry, he would never again serve as premier.

The desire for a monarchy was strong in France in the early years of the Third Republic – Henri, Count of Chambord having made a bid early in its history. A committed republican, Ferry proceeded to a wide-scale "purge" by dismissing many known monarchists from top positions in the magistrature

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a ''magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

, army, and civil and diplomatic service.

In the 1890s he visited Algeria and provided a critical report. He predicted that Algeria could not escape a conflict between Indigènes and Europeans:

* He was interested in providing education to the Indigènes, while the settlers

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

were skeptical about this topic.

* He was given a poor image of the settlers because they did not want to pay taxes.

* He also noted that the Indigène was contributing to the ''Communes de plein exercice'' without profiting of it.

* He considered the settlers were poorly chosen, and that they were too numerous

* He was in favor of the self-government of Algeria but considered the settler were not enough educated to do so

* He considered that the Muslims did not want French citizenship, Military service, French mandatory schools, civil French law.

* He considered that the Muslims wanted fewer taxes, taxes more used for their needs, the authority of the ''cadis'', Muslim city councilors involvement in Mayor election

* He also considered that the Land laws were a failure.

Agreements with Germany

The key to understanding Ferry's unique position in Third Republic history is that until his political critic,

The key to understanding Ferry's unique position in Third Republic history is that until his political critic, Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

became Prime Minister twice in the 20th century, Ferry had the longest tenure as Prime Minister under that regime. He also played with political dynamite that eventually destroyed his success. Ferry (like his 20th-century equivalent Joseph Caillaux) believed in not confronting Wilhelmine Germany by threats of a future war of revenge. Most French politicians in the middle and right saw it as a sacred duty to one day lead France again against Germany to reclaim Alsace-Lorraine, and avenge the awful defeat of 1870. But Ferry realized that Germany was too powerful, and it made more sense to cooperate with Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

and avoid trouble. A sensible policy – but hardly popular.

Bismarck was constantly nervous about the situation with France. Although he had despised the ineptness of the French under Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

and the government of Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

and Jules Favre, he had not planned for all the demands he presented the French in 1870. He only wished to temporarily cripple France by the billion franc reparation, but suddenly he was confronted by the demands of Marshals Albrecht von Roon and Helmut von Moltke Helmut is a German name. Variants include Hellmut, Helmuth, and Hellmuth.

From old German, the first element deriving from either ''heil'' ("healthy") or ''hiltja'' ("battle"), and the second from ''muot'' ("spirit, mind, mood").

Helmut may refer ...

(backed by Emperor Wilhelm I) to annex the two French provinces as further payment. Bismarck, for all his abilities regarding manipulating events, could not afford to anger the Prussian military. He got the two provinces, but he realized it would eventually have severe future repercussions.

Bismarck was able to ignore the French for most of the 1870s and early 1880s, but as he found problems with his three erstwhile allies (Austria, Russia, and Italy), he realized France might one day take advantage of this (as it did with Russia in 1894). When Ferry came up with a radically different approach to the situation and offered an olive branch, Bismarck reciprocated. A Franco-German friendship would alleviate problems of siding with either Austria or Russia, or Austria and Italy. Bismarck approved of the colonial expansion that France pursued under Ferry. He only had some problems with local German imperialists who were critical that Germany lacked colonies, so he found a few in the 1880s, making certain he did not confront French interests. But he also suggested Franco-German cooperation on the imperial front against the British Empire, thus hoping to create a wedge between the two Western European great powers. It did, as a result, leading to a major race for influence across Africa that nearly culminated in war in the next decade, at Fashoda in the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

in 1898. But by then both Bismarck and Ferry were dead, and the rapprochement policy died when Ferry lost office. As for Fashoda, while it was a confrontation, it led to Britain and France eventually discussing their rival colonial goals, and agreeing to support each other's sphere of influence – the first step to the Entente Cordiale between the countries in 1904.

Later life

Ferry remained an influential member of the moderate republican party, and directed the opposition toGeneral Boulanger

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Repub ...

. After the resignation of Jules Grévy (2 December 1887), he was a candidate for the presidency of the republic, but the radicals refused to support him, and he withdrew in favor of Sadi Carnot.

On 10 December 1887, a man named Aubertin attempted to assassinate Jules Ferry, who would later die on 17 March 1893 from complications attributed to this wound. The Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

gave him a state funeral.

Ferry's 1st Ministry, 23 September 1880 – 14 November 1881

* Jules Ferry – President of the Council and Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts *Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire

Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire (19 August 1805 – 24 November 1895) was a French philosopher, journalist, statesman, and possible illegitimate son of Napoleon I of France.

Biography

Jules was born in Paris. Marie Belloc Lowndes, in th ...

– Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

* Jean Joseph Farre – Minister of War

* Ernest Constans

Jean Antoine Ernest Constans (3 May 1833 – 7 April 1913) was a French politician and colonial administrator.

Biography

Born in Béziers, Hérault, he began his career as professor of law. In 1876 he was elected deputy for Toulouse to the F ...

– Minister of the Interior and Worship

* Pierre Magnin – Minister of Finance

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic policy and financial regulation.

A finance minister's portfolio has a large variety of names around the world, such as "treasury", ...

* Jules Cazot

Jules-Théodore-Joseph Cazot (11 February 1821 – 27 November 1912) was a French politician of the French Third Republic. He was a member of the National Assembly of 1871. He was a senator for life from 1875 until his death. He was minister of j ...

– Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

* Georges Charles Cloué – Minister of Marine and Colonies

* Sadi Carnot – Minister of Public Works

* Adolphe Cochery – Minister of Posts and Telegraphs

* Pierre Tirard

Pierre Emmanuel Tirard (; 27 September 1827 – 4 November 1893) was a French politician.

Biography

He was born to French parents in Geneva, Switzerland. After studying in his native town, Tirard became a civil engineer. After five years of gov ...

– Minister of Agriculture and Commerce

Ferry's 2nd Ministry, 21 February 1883 – 6 April 1885

* Jules Ferry – President of the Council and Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts * Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour – Minister of Foreign Affairs *Jean Thibaudin

Jean Thibaudin (November 1822 – 1905) was a French general and politician of the French Third Republic. He was educated at the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr in Brittany. He was involved in the colonization of Madagascar.

He was min ...

– Minister of War

* Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau – Minister of the Interior

* Pierre Tirard

Pierre Emmanuel Tirard (; 27 September 1827 – 4 November 1893) was a French politician.

Biography

He was born to French parents in Geneva, Switzerland. After studying in his native town, Tirard became a civil engineer. After five years of gov ...

– Minister of Finance

* Félix Martin-Feuillée – Minister of Justice and Worship

* Charles Brun – Minister of Marine and Colonies

* Jules Méline

Félix Jules Méline (; 20 May 183821 December 1925) was a French statesman, Prime Minister of France from 1896 to 1898.

Biography

Méline was born at Remiremont. Having taken up law as his profession, he was chosen a deputy in 1872, and in 18 ...

– Minister of Agriculture

* David Raynal – Minister of Public Works

* Adolphe Cochery – Minister of Posts and Telegraphs

* Anne Charles Hérisson

Charles Hérisson (12 October 1831 – 23 November 1893) was a French lawyer and politician of the French Third Republic. He was a member of the National Assembly of 1871, where he joined the Opportunist Republican parliamentary group, ''Gauche r ...

– Minister of Commerce

Changes

* 9 August 1883 – Alexandre Louis François Peyron succeeds Charles Brun as Minister of Marine and Colonies

* 9 October 1883 – Jean-Baptiste Campenon

General Jean Baptiste Marie Edouard Campenon (5 May 1819 in Tonnerre – 16 March 1891 in Neuilly-sur-Seine) was a French general and politician.

Life

He studied at the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr, graduating on 1 October 1840 as ...

succeeds Thibaudin as Minister of War.

* 20 November 1883 – Jules Ferry succeeds Challemel-Lacour as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Armand Fallières succeeds Ferry as Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts.

* 14 October 1884 – Maurice Rouvier succeeds Hérisson as Minister of Commerce

* 3 January 1885 – Jules Louis Lewal

Jules Louis Lewal (13 December 1823 – 22 January 1908) was a French general, who also wrote scripts like Stratégie de combat (translation: Combat strategy).

Biography

He was born in Paris; entered the army in 1846; served in the Italian camp ...

succeeds Campenon as Minister of War.

See also

* Jules Ferry laws *Opportunist Republicans

The Moderates or Moderate Republicans (french: Républicains modérés), pejoratively labeled Opportunist Republicans (), was a French political group active in the late 19th century during the Third French Republic. The leaders of the group inc ...

* Vergonha

In Occitan, ''vergonha'' (, meaning "shame") refers to the effects of various language discriminatory policies of the government of France on its minorities whose native language was deemed a ''patois'', where a Romance language spoken in the co ...

* Nursery Schools of France

Notes

References

* * * * Taylor, A. J. P. ''Germany's First Bid For Colonies, 1884–1885: A Move in Bismarck's European Policy'' (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc. – the Norton Library, 1970), pp. 17–31: Chapter 1. Bismarck's Approach to France, December 1883 – April 1884.External links

* ''Lettre aux Instituteurs'', Jules Ferry, November 1883, online and analyzed oBibNum

(for English version, click 'Télécharger') * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ferry, Jules 1832 births 1893 deaths People from Saint-Dié-des-Vosges Politicians from Grand Est Opportunist Republicans Prime Ministers of France French Foreign Ministers Members of the 4th Corps législatif of the Second French Empire Members of the National Assembly (1871) Members of the 1st Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 3rd Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 4th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic French Senators of the Third Republic Senators of Vosges (department) Presidents of the Senate (France) Ambassadors of France to Greece 19th-century French diplomats Mayors of Paris French Freemasons University of Paris alumni French people of the Franco-Prussian War People of the Sino-French War People of the Tonkin campaign