Jubal Early on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

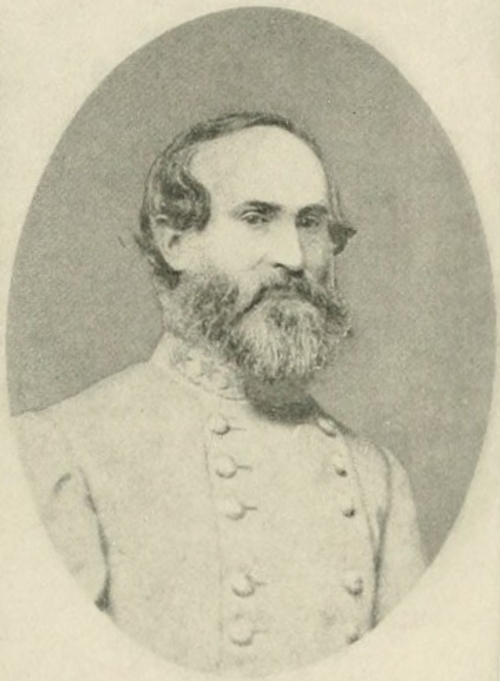

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate general during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Trained at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, Early resigned his U.S. Army commission after the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans and Black Indians. It was part of a ser ...

and his Virginia military commission after the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, in both cases to practice law and participate in politics. Accepting a Virginia and later Confederate military commission as the American Civil War began, Early fought in the Eastern Theater throughout the conflict. He commanded a division under Generals Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

and Richard Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell (February 8, 1817 – January 25, 1872) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Le ...

, and later commanded a corps. A key Confederate defender of the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

, during the Valley Campaigns of 1864, Early made daring raids to the outskirts of Washington, D.C., and as far as York, Pennsylvania

York (Pennsylvania Dutch: ''Yarrick''), known as the White Rose City (after the symbol of the House of York), is the county seat of York County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located in the south-central region of the state. The populatio ...

, but was crushed by Union forces under General Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

, losing over half his forces and leading to the destruction of much of the South's food supply. After the war, Early fled to Mexico, then Cuba and Canada, and upon returning to the United States took pride as an "unrepentant rebel."

Particularly after the death of Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

in 1870, Early delivered speeches establishing the Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

position. Early helped found the Southern Historical Society

The Southern Historical Society was an American organization founded to preserve archival materials related to the government of the Confederate States of America and to document the history of the Civil War.

Early was born on November 3, 1816 in the Red Valley section of

During the Gettysburg Campaign of mid-1863, Early continued to command a division in the Second Corps under Lt. Gen. Ewell. His troops were instrumental in overcoming Union defenders at the

During the Gettysburg Campaign of mid-1863, Early continued to command a division in the Second Corps under Lt. Gen. Ewell. His troops were instrumental in overcoming Union defenders at the

When the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865 Early escaped to Texas on horseback, hoping to find a Confederate force that had not surrendered. He proceeded to

When the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865 Early escaped to Texas on horseback, hoping to find a Confederate force that had not surrendered. He proceeded to  In his final years, Early became an outspoken proponent of

In his final years, Early became an outspoken proponent of

* The last ferry operating on the

* The last ferry operating on the

''The Campaigns of Gen. Robert E. Lee: An Address by Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early before Washington & Lee University, January 19, 1872''.

Baltimore: John Murphy & Co., 1872 . * Early, Jubal A., and Ruth H. Early

''Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early, C.S.A.: Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States''

Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1912. . * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Freeman, Douglas S.br>''R. E. Lee, A Biography''

4 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934–35. . * Gallagher, Gary W. ''Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy (Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 4)''. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1995. . * Gallagher, Gary W., ed. ''Struggle for the Shenandoah: Essays on the 1864 Valley Campaign''. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991. . * Gallagher, Gary W., and Alan T. Nolan, eds. ''The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000. . * Gordon, John B.br>''Reminiscences of the Civil War''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1904. * Leepson, Marc. ''Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington D.C., and Changed American History''. New York: Thomas Dunne Books (St. Martin's Press), 2005. .* Lewis, Thomas A., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''The Shenandoah in Flames: The Valley Campaign of 1864''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1987. . * Sifakis, Stewart. ''Who Was Who in the Civil War''. New York: Facts On File, 1988. . * Tagg, Larry

''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Ulbrich, David. "Lost Cause." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * U.S. War Department

''The War of the Rebellion''

''a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies''. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. .

Franklin County, Virginia

Franklin County is located in the Blue Ridge foothills of the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 54,477. Its county seat is Rocky Mount. Franklin County is part of the Roanoke Metropolitan Statistical Area ...

, third of ten children of Ruth (née Hairston) (1794–1832) and Joab Early (1791–1870). The Early family was well-established and well-connected in the area, either one of the First Families of Virginia

First Families of Virginia (FFV) were those families in Colonial Virginia who were socially prominent and wealthy, but not necessarily the earliest settlers. They descended from English colonists who primarily settled at Jamestown, Williamsbur ...

, or linked to them by marriage as they moved westward toward the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virg ...

from Virginia's Eastern Shore. His great grandfather, Col. Jeremiah Early (1730–1779) of Bedford County, Virginia

Bedford County is a United States county located in the Piedmont region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Its county seat is the town of Bedford, which was an independent city from 1968 until rejoining the county in 2013.

Bedford County was ...

bought an iron furnace in Rocky Mount (in what became Franklin County) with his son-in-law Col. James Calloway, but soon died. He willed it to his sons Joseph, John, and Jubal Early (grandfather of the present Jubal A. Early, named for his grandfather). Of those men, only John Early (1773–1833) would live long and prosper—he sold his interest in the furnace and bought a plantation from his father-in-law in Albemarle County

Albemarle County is a county located in the Piedmont region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Its county seat is Charlottesville, which is an independent city and enclave entirely surrounded by the county. Albemarle County is part of the Char ...

. Earlysville, Virginia, was named after him. Jubal Early (for whom the baby Jubal was named) only lived a couple of years after his marriage. His young sons Joab (this Early's father) and Henry became wards of Col. Samuel Hairston (1788–1875), a major landowner in southwest Virginia, and in 1851 reputedly the richest man in the South, worth $5 million in land and enslaved people.

Joab Early married his mentor's daughter, as well as like him (and his own son, this Jubal Early), served in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

part-time (1824–1826), and become the county sheriff and led its militia, all while managing his extensive tobacco plantation of more than 4,000 acres using enslaved labor. His eldest son Samuel Henry Early (1813–1874) became a prominent manufacturer of salt using enslaved labor in the Kanawha Valley

The Kanawha River ( ) is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi (156 km) long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, its valley has been a significant industrial region of the st ...

(of what became West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

during the American Civil War), and was a Confederate officer. Samuel H. Early married Henrian Cabell (1822–1890); their daughter, Ruth Hairston Early (1849–1928), became a prominent writer, member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

, and preservationist in Lynchburg, which became her family's home before the American Civil War and this Jubal Early's base during his final decades. His slightly younger brother Robert Hairston Early (1818–1882) also served as a Confederate officer during the Civil War but moved to Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

.

Jubal Early had the wherewithal to attend local private schools in Franklin County, as well as more advanced private academies in Lynchburg and Danville. He was deeply affected by his mother's death in 1832. The following year, his father and Congressman Nathaniel Claiborne

Nathaniel Herbert Claiborne (November 14, 1777 – August 15, 1859) was a nineteenth-century Virginia lawyer and planter, as well as an American politician who served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly and in the United States H ...

secured a place in the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

for young Early, citing his particular aptitude for science and mathematics. He passed probation and became the first boy from Franklin County to enter the Military Academy. Early graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1837, ranked 18th of 50 graduating cadets and sixth among its engineering graduates. During his tenure at the Academy, fellow cadet Lewis Addison Armistead

Lewis Addison Armistead (February 18, 1817 – July 5, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. On July 3, 1863, as part of Pickett's Charge during ...

broke a mess plate over Early's head, which prompted Armistead's departure from the Academy, although he, too, became an important Confederate officer. Other future generals in that 1837 class were Union generals Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

(with whom Early would have a verbal mess hall altercation over slavery), John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick (September 13, 1813 – May 9, 1864) was a military officer and Union Army general during the American Civil War.

He was wounded three times at the Battle of Antietam while leading his division in an unsuccessful assault against Co ...

and William H. French

William Henry French (January 13, 1815 – May 20, 1881) was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army General in the American Civil War. He rose to temporarily command a corps within the Army of the Potomac, but was relieved of active ...

, as well as future Confederate generals Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Wester ...

, John C. Pemberton

John Clifford Pemberton (August 10, 1814 – July 13, 1881) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole Wars and with distinction during the Mexican–American War. He resigned his commission to serve as a Confederate ...

, Arnold Elzey

Arnold Elzey Jones Jr. (December 18, 1816 – February 21, 1871), known for much of his life simply as Arnold Elzey, was a soldier in both the United States Army and the Confederate Army, serving as a major general in the American Civil War. At ...

and William H. T. Walker

William Henry Talbot Walker (November 26, 1816 – July 22, 1864) was an American soldier. He was a career United States Army officer who fought with distinction during the Mexican-American War, and also served as a Confederate general ...

. Other future generals whose time at West Point also overlapped with Early's included P.G.T. Beauregard, Richard Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell (February 8, 1817 – January 25, 1872) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Le ...

, Edward "Allegheny" Johnson, Irwin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

and George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

.

Early military, legal and political careers

Upon graduating from West Point, Early received a commission as asecond lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

in the 3rd U.S. Artillery regiment. Assigned to fight against the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

in Florida, he was disappointed that he never even saw a Seminole and merely heard "some bullets whistling among the trees" not close to his position. His elder brother Samuel counseled him to finish his statutory one-year obligation, then return to civilian life. Thus Early resigned from the Army for the first time in 1838, later commenting that if notice of a promotion that reached him in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

during his return to Virginia had come earlier, he might have withheld that letter of resignation.

Early studied law with local attorney Norborne M. Taliaferro and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1840. Franklin County voters the next year elected Early as one of their delegates in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

(a part-time position); he was a Whig and served one term alongside Henry L. Muse from 1841 to 1842. After redistricting reduced Franklin County's representation, his mentor (but Democrat) Norborne M. Taliaferro was elected to succeed him (and was re-elected many times until 1854, as well as become a local judge). Meanwhile, voters elected Early Talliaferro's successor as Commonwealth's attorney (prosecutor) for both Franklin and Floyd Counties; he was re-elected and served until 1852, apart from leading other Virginia volunteers during the Mexican–American War as noted below.

During the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

(despite the opposition of prominent Whig Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

to that war), Early volunteered and received a commission as a Major with the 1st Virginia Volunteers. During Early's time at West Point, he had considered resigning in order to fight for Texas' independence, but had been dissuaded by his father and elder brother. He served from 1847 to 1848, although his Virginians arrived too late to see battlefield combat. Major Early was assigned to logistics, as inspector general on the brigade's staff under West Pointers Col. John F. Hamtramck and Lt. Col. Thomas B. Randolph, and later helped govern the town of Monterrey

Monterrey ( , ) is the capital and largest city of the northeastern state of Nuevo León, Mexico, and the third largest city in Mexico behind Guadalajara and Mexico City. Located at the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental, the city is ancho ...

, bragging that the good conduct of his men won universal praise and produced better order in Monterrey than ever before, as well as that by the time they were mustered out of service at Fort Monroe, many of his men conceded that they had misjudged him at the beginning. While in Mexico, Early met Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

, who commanded the first Mississippi Volunteers, and they exchanged compliments. During the winter in damp northern Mexico, Early experienced the first attacks of the rheumatoid arthritis plagued him the rest of his life, and he was even sent home for three months to recover.

However, his legal career was not particularly remunerative when he returned although Early won an inheritance case in Lowndes County, Mississippi

Lowndes County is a county on the eastern border of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 59,779. Its county seat is Columbus. The county is named for U.S. Congressman and slave owner William Jo ...

. He handled many cases involving slaves as well as divorces, but owned only one slave during his life. In the 1850 census, Early owned no real estate and lived in a tavern, as did several other lawyers; likewise, in the 1860 census, he owned neither real nor personal property (such as slaves) and lived in a hotel, as did several other lawyers and merchants. During this time, Early lived with Julia McNealey, who bore him four children whom Early acknowledged as his (including Jubal L. Early). She married another man in 1871. A biographer characterized Early as both unconventional and contrarian, "yet wedded to stability and conservatism".

Although Early failed to win election as Franklin County's delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850 was an assembly of elected delegates chosen by the voters to write the fundamental law of Virginia. It is known as the Reform Convention because it liberalized Virginia political institutions.

Backgro ...

, Franklin County voters elected Early and Peter Saunders (who lived in the same boardinghouse, although the son of prominent local landowner Samuel Sanders) to represent them at the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861

The Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 was called in Richmond to determine whether Virginia would secede from the United States, to govern the state during a state of emergency, and to write a new Constitution for Virginia, which was subsequent ...

. A staunch Unionist, Early argued that the rights of Southerners without slaves were worth protection as much as those who owned slaves and that secession would precipitate war. Despite being mocked as "the Terrapin from Franklin," Early strongly opposed secession during both votes (Saunders left before the second vote, which approved secession).

American Civil War

However, whenPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, Early fumed. After Virginia voters ratified secession, like many of his cousins, he accepted a commission to serve against the U.S. Army. Initially, Early became a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

in the Virginia Militia and was sent to Lynchburg, where he raised three regiments and then commanded one of them. On June 19, 1861, Early formally became a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

in the Confederate army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

, commanding the 24th Virginia Infantry

The 24th Virginia Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment raised in southwestern Virginia for service in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. It fought throughout the conflict, mostly with the Army of Northern Virginia ...

, including his young cousin (previously expelled from Virginia Military Institute

la, Consilio et Animis (on seal)

, mottoeng = "In peace a glorious asset, In war a tower of strength""By courage and wisdom" (on seal)

, established =

, type = Public senior military college

, accreditation = SACS

, endowment = $696.8 mill ...

(VMI) for attending a tea party), Jack Hairston.

After the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

(also called the First Battle of Manassas') in July 1861, Early was promoted to brigadier general, because his valor at Blackburn's Ford impressed General P.G.T. Beauregard, and his troops' charge along Chinn Ridge helped rout the Union forces (although his cousin Cpt. Charles F. Fisher of the 6th North Carolina died supporting the assault). As general, Early led Confederate troops in most of the major battles in the Eastern Theater, including the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

, the Second of Bull Run, the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

, the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Bur ...

, the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

, the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

, and numerous battles in the Shenandoah Valley.

General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

, affectionately called Early his "Bad Old Man" because of his short temper, insubordination, and use of profanity. However, Lee also appreciated Early's aggressive fighting and ability to command units independently. Most of Early's soldiers (except during the war's last days) referred to him as "Old Jube" or "Old Jubilee" with enthusiasm and affection. (The "old" referred to a stoop because of the rheumatism incurred in Mexico.) However, his subordinate officers often experienced Early's inveterate complaints about minor faults and biting criticism at the least opportunity. Generally blind to his own mistakes, Early reacted fiercely to criticism or suggestions from below.

Serving under Stonewall Jackson

As the Union Peninsular Campaign began in May 1862, Early without adequate reconnaissance led a futile charge through a swamp and wheat field against two Union artillery redoubts at what became known as theBattle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first p ...

, His 22 year old cousin Jack Hairston was killed. The 24th Virginia suffered 180 killed, wounded or missing in the battle; Early himself received a shoulder wound and convalesced near home in Rocky Mount, Virginia

Rocky Mount is a town in and the county seat of Franklin County, Virginia, United States. The town is part of the Roanoke Metropolitan Statistical Area, and had a population of 4,903 as of the 2020 census. It is located in the Roanoke Region o ...

. On June 26, the first day of the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

, Early reported himself ready for duty. However, the brigade he had commanded at Williamsburg no longer existed, having suffered severe casualties in that assault, and an army reorganization assigned the remaining men whose enlistments continued to other units. General Lee informed Early that he could not be assigned a new command in the middle of the current heated action and recommended for Early to wait until an opening came up somewhere. On July 1, just in time for the Battle of Malvern Hill

The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, was fought on July 1, 1862, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. M ...

(the last engagement in the Seven Days Battles), Early (though still unable to mount a horse without assistance) received command of Brig. Gen. Arnold Elzey's brigade because Elzey had been wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill and the ranking colonel, James Walker, seemed too inexperienced for brigade command. However, that brigade was not engaged in the battle.

For the rest of 1862, General Early commanded troops within the Second Corps under General Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

. During the Northern Virginia Campaign, Early's immediate superior was Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell (February 8, 1817 – January 25, 1872) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Le ...

. Early received accolades for his performance at the Battle of Cedar Mountain

The Battle of Cedar Mountain, also known as Slaughter's Mountain or Cedar Run, took place on August 9, 1862, in Culpeper County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks attacked Confede ...

. Furthermore, his troops arrived in the nick of time to reinforce Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill on Jackson's left on Stony Ridge during the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

(a/k/a Second Manassas).

At the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

, Early ascended to division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

command when his commander, Alexander Lawton

Alexander Robert Lawton (November 4, 1818 – July 2, 1896) was a lawyer, politician, diplomat, and brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Lawton was born in the Beaufort District of South ...

, was wounded on September 17, 1862, after Lawton had assumed that division command while Maj. Gen. Ewell recovered after a wound received at Second Manassas caused amputation of his leg. At Fredericksburg, Early and his troops saved the day by counterattacking the division of Maj. Gen. George Meade, which penetrated a gap in Jackson's lines. Impressed by Early's performance, Gen. Lee retained him as commander of what had been Ewell's division; Early formally received a promotion to major general on January 17, 1863.

During the Chancellorsville campaign, which began on May 1, 1863, Lee gave Early 9,000 men to defend Fredericksburg at Marye's Heights against superior forces (4 divisions) under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick (September 13, 1813 – May 9, 1864) was a military officer and Union Army general during the American Civil War.

He was wounded three times at the Battle of Antietam while leading his division in an unsuccessful assault against Co ...

. Early was able to delay the Union forces and pin down Sedgwick while Lee and Jackson attacked the rest of the Union troops to the west. Sedgwick's eventual attack on Early up Marye's Heights on May 3, 1863 is sometimes known as the Second Battle of Fredericksburg

The Second Battle of Fredericksburg, also known as the Second Battle of Marye's Heights, took place on May 3, 1863, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, as part of the Chancellorsville Campaign of the American Civil War.

Background

Confederate Gen. Rob ...

. However, after the battle, Early engaged in a newspaper war with Brig. Gen. William Barksdale of Mississippi (a former newspaperman and congressman), who had commanded a division under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws ( ; January 15, 1821 – July 24, 1897) was a United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He served at Antietam and Fredericksburg, where Robert E. Lee praised his defense of Marye's Heights, ...

in the First Corps, until Gen. Lee told the two officers to stop their public feud. Furthermore, General Stonewall Jackson died on May 10, 1863 of a wound received from his own sentry on the night of May 2, 1863, and the recovered Lt. Gen.

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Richard S. Ewell assumed command of the Second Corps.

Gettysburg and Overland Campaign

During the Gettysburg Campaign of mid-1863, Early continued to command a division in the Second Corps under Lt. Gen. Ewell. His troops were instrumental in overcoming Union defenders at the

During the Gettysburg Campaign of mid-1863, Early continued to command a division in the Second Corps under Lt. Gen. Ewell. His troops were instrumental in overcoming Union defenders at the Second Battle of Winchester

The Second Battle of Winchester was fought between June 13 and June 15, 1863 in Frederick County and Winchester, Virginia as part of the Gettysburg Campaign during the American Civil War. As Confederate Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell move ...

on June 13–15. They captured many prisoners, and opened up the Shenandoah Valley for Lee's oncoming forces. Early's division, augmented with cavalry, eventually marched eastward across the South Mountain South Mountain or South Mountains may refer to:

Canada

* South Mountain, a village in North Dundas, Ontario

* South Mountain (Nova Scotia), a mountain range

* South Mountain (band), a Canadian country music group

United States

Landforms

* Sout ...

into Pennsylvania, seizing vital supplies and horses along the way. Early captured Gettysburg on June 26 and demanded a ransom, which was never paid. He threatened to burn down any home which harbored a fugitive slave. Two days later, he entered York County and seized York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. Here, his ransom demands were partially met, including $28,000 in cash. York thus became the largest Northern town to fall to the Rebels during the war. He also burned an iron foundry near Caledonia

Caledonia (; ) was the Latin name used by the Roman Empire to refer to the part of Great Britain () that lies north of the River Forth, which includes most of the land area of Scotland. Today, it is used as a romantic or poetic name for all ...

owned by abolitionist U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

. Elements of Early's command on June 28 reached the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

, the farthest east in Pennsylvania that any organized Confederate force could penetrate. On June 30, Early was recalled to join the main force as Lee concentrated his army to meet the oncoming Federals. Troops under Early's command were also responsible for capturing escaped slaves to send them back to the south, which resulted in the seizure of free Blacks who were unable to evade the invading army. Over 500 Black people were abducted from southern Pennsylvania.

Approaching the Gettysburg battlefield from the northeast on July 1, 1863, Early's division was on the leftmost flank of the Confederate line. He soundly defeated Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow's division (part of the Union XI Corps 11 Corps, 11th Corps, Eleventh Corps, or XI Corps may refer to:

* 11th Army Corps (France)

* XI Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XI Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* XI ...

), inflicting three times the casualties to the defenders as he suffered, and drove the Union troops back through the streets of the town, capturing many of them. However, this later became another controversy, as Lt. Gen. Ewell denied Early permission to assault East Cemetery Hill to which Union troops had retreated. When the assault was allowed the following day as part of Ewell's efforts on the Union right flank, it failed with many casualties. The delay allowed Union reinforcements to arrive, which repulsed Early's two brigades. On the third day of battle, Early detached one brigade to assist Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division in an unsuccessful assault on Culp's Hill

Culp's Hill,. The modern U.S. Geographic Names System refers to "Culps Hill". which is about south of the center of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, played a prominent role in the Battle of Gettysburg. It consists of two rounded peaks, separated by a ...

. Elements of Early's division covered the rear of Lee's army during its retreat from Gettysburg on July 4 and July 5.

Early's forces wintered in the Shenandoah Valley in 1863–64. During this period, he occasionally filled in as corps commander when Ewell's illness forced absences. On May 31, 1864, Lee expressed his confidence in Early's initiative and abilities at higher command levels. With Confederate President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

now being authorized to make temporary promotions; on Lee's request Early was promoted to the temporary rank of lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

.

Early fought well during the inconclusive Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Ar ...

(during which a cousin died), and assumed command of the ailing A.P. Hill's Third Corps during the march to intercept Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

at Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 186 ...

. At Spotsylvania, Early occupied the relatively quiet right flank of the Mule Shoe. After Hill had recovered and resumed command, Lee, dissatisfied with Ewell's performance at Spotsylvania, assigned him to defend Richmond and gave Early command of the Second Corps. Thus, Early commanded that corps in the Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses ...

.

However, Union Gen. David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

had burned the VMI in Lexington

Lexington may refer to:

Places England

* Laxton, Nottinghamshire, formerly Lexington

Canada

* Lexington, a district in Waterloo, Ontario

United States

* Lexington, Kentucky, the largest city with this name

* Lexington, Massachusetts, the oldes ...

on June 11, and was raiding through the Shenandoah Valley Confederate breadbasket, so Lee sent Early and 8,000 men to defend Lynchburg, an important railroad hub (with links to Richmond, the Valley and points southwest) as well as many hospitals for recovering Confederate wounded. John C. Breckinridge, Arnold Elzey and other convalescing Confederates and the remains of VMI's cadet corps assisted Early and his troops, as did many townspeople, including Narcissa Chisholm Owen

Narcissa Chisholm Owen (October 3, 1831 – July 11, 1911) was a Native American educator, memoirist, and artist of the late 19th and early 20th century. She was the daughter of Old Settler Cherokee Chief Thomas Chisholm, wife of Virginia state s ...

, wife of the president of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Using a ruse involving multiple trains entering town to exaggerate his strength, Early convinced Hunter to retreat back toward West Virginia on June 18, in what became known as the Battle of Lynchburg

The Battle of Lynchburg was fought on June 17–18, 1864, two miles outside Lynchburg, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. The Union Army of West Virginia, under Maj. Gen. David Hunter, attempted to capture the city but was repulsed ...

, although the pursuing Confederate cavalry were soon outrun.

Shenandoah Valley, 1864–1865

During the Valley Campaigns of 1864, Early received a temporary promotion to lieutenant general and command of the "Army of the Valley" (the nucleus of which was the former Second Corps). Thus Early commanded the Confederacy's last invasion of the North, secured much-needed funds and supplies for the Confederacy and drawing off Union troops from thesiege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

. Since Union armies under Grant and Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

were rapidly capturing formerly Confederate territory, Lee sent Early's corps to sweep Union forces from the Shenandoah Valley, as well as to menace Washington, D.C. He hoped to secure supplies as well as compel Grant to dilute his forces against Lee around the Confederate capital at Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

and its supply hub at Petersburg.

Early delayed his march for several days in a futile attempt to capture a small force under Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil ...

at Maryland Heights

Maryland Heights is a second-ring north suburb of St. Louis, located in St. Louis County, Missouri, United States. The population was 27,472 at the 2010 census. The city was incorporated in 1985. Edwin L. Dirck was appointed the city's first m ...

near Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

. His men then rested and ate captured Union supplies from July 4 through July 6. Although elements of his army reached the outskirts of Washington at a time when it was largely undefended, his delay at Maryland Heights and from extorting Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in and the county seat of Frederick County, Maryland. It is part of the Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area. Frederick has long been an important crossroads, located at the intersection of a major north–south Native ...

, prevented him from being able to attack the federal capital. Residents of Frederick paid $200,000 ($ in dollars) on July 9 and avoided being sacked, supposedly because some women had booed Stonewall Jackson's troops on their trip through town the previous year (the city had divided loyalties and later erected a Confederate Army monument). Later in the month, Early attempted to extort funds from Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

and Hancock, Maryland

Hancock is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. The population was 1,546 at the 2010 census. The Western Maryland community is notable for being located at the narrowest part of the state. The north-south distance from the Penns ...

, and his cavalry commanders burned Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley, and north of Maryland and the ...

, when that city could not pay sufficient ransom.http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-202

Meanwhile, Grant sent two VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army du ...

divisions from the Army of the Potomac to reinforce Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

defending the railroad to Washington, D.C. With 5,800 men, Wallace delayed Early for an entire day at the Battle of Monocacy Junction outside Frederick, which allowed additional Union troops to reach Washington and strengthen its defenses. Early's invasion caused considerable panic in both Washington and Baltimore, and his forces reached Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially unincorporated, in practice it is an edge city, with a population of 81,015 at the 2020 ce ...

, and the outskirts of the District of Columbia. He also sent some cavalry under Brig. Gen. John McCausland to Washington's western side.

Knowing that he lacked sufficient strength to capture the federal capital, Early led skirmishes at Fort Stevens and Fort DeRussy. Opposing artillery batteries also traded fire on July 11 and July 12. On both days, President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

watched the fighting from the parapet at Fort Stevens, his lanky frame a clear target for hostile military fire. After Early withdrew, he said to one of his officers, "Major, we haven't taken Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell."

Early retreated with his men and captured loot across the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

to Leesburg, Virginia

Leesburg is a town in the state of Virginia, and the county seat of Loudoun County. Settlement in the area began around 1740, which is named for the Lee family, early leaders of the town and ancestors of Robert E. Lee. Located in the far northeas ...

, on July 13, then headed west toward the Shenandoah Valley. At the Second Battle of Kernstown

The Second Battle of Kernstown was fought on July 24, 1864, at Kernstown, Virginia, outside Winchester, Virginia, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 in the American Civil War. The Confederate Army of the Valley under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Ear ...

on July 24, 1864, Early's forces defeated a Union army under Brig. Gen. George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nanta ...

. Through early August, Early's cavalry and guerrilla forces also attacked the B&O Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

in various places, seeking to disrupt Union supply lines, as well as secure supplies for their own use.

As July ended, Early ordered cavalry under Generals McCausland and Bradley Tyler Johnson

Bradley Tyler Johnson (September 29, 1829 – October 5, 1903) was an American lawyer, soldier, and writer. Although his home state of Maryland remained in the Union during the American Civil War, Johnson owned and traded slaves, and accordi ...

to raid across the Potomac River. On July 30, they burned more than 500 buildings in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, nominally in retaliation for Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

's burning VMI in June and the homes of three prominent Southern sympathizers in Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County is located in the Shenandoah Valley in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. It is the easternmost county of the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 57,701. Its county seat is Charles Tow ...

earlier that month, as well as the Pennsylvania town's failure to heed his ransom demands (town leaders collecting door to door could only raise about $28,000 of the $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in greenbacks demanded, the local bank having sent its reserves out of town in anticipation). Early's forces also burned the region's only bridge across the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

, impeding commerce as well as Union troop movements. Union cavalry commander Brig. Gen. William W. Averell

William Woods Averell (November 5, 1832 – February 3, 1900) was a career United States Army officer and a cavalry general in the American Civil War. He was the only Union general to achieve a major victory against the Confederates in the V ...

had thought the attackers would raid toward Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

, and so arrived too late to save Chambersburg. However, a rift developed between Early's two cavalry commanders because Marylander Johnson was loath to raze Cumberland and Hancock for likewise failing to meet ransom demands, because he saw McCausland's brigade commit war crimes while looting Chambersburg ("every crime ... of infamy.. except murder and rape"). Averill's Union cavalry, although half the size of the Confederate cavalry, chased them back across the Potomac River, and they skirmished three times, the Confederate cavalry losing most severely at the Battle of Moorefield in Hardy County, West Virginia

Hardy County is a county in the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,299. Its county seat is Moorefield. The county was created from Hampshire County in 1786 and named for Samuel Hardy, a distinguished V ...

on August 7.

Realizing Early could still easily attack Washington, Grant in mid-August sent Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

and additional troops to subdue Early's forces, as well as local guerilla forces led by Col. John S. Mosby. At times outnumbering the Confederates three to one, Sheridan defeated Early in three battles. Sheridan's troops also laid waste to much of what had been the Confederacy's breadbasket, in order to deny rations and other supplies to Lee's army. On September 19, 1864, Early's troops lost the Third Battle of Winchester

The Third Battle of Winchester, also known as the Battle of Opequon or Battle of Opequon Creek, was an American Civil War battle fought near Winchester, Virginia, on September 19, 1864. Union Army Major General Philip Sheridan defeated Confederate ...

after raiding the B&O depot at Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

. Key subordinates (General Robert Rodes and A.C. Godwin) were killed, General Fitz Lee wounded and General John C. Breckinridge was ordered back to Southwest Virginia—so Early had lost about 40% of his troop strength since the campaign began, despite distracting thousands of Union troops. The Confederates never again captured Winchester or the northern Valley. On September 21–22, Early's troops lost Strasburg after Sheridan's much larger force (35,000 Union troops vs. 9500 Confederates ) won the Battle of Fisher's Hill

The Battle of Fisher's Hill was fought September 21–22, 1864, near Strasburg, Virginia, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 during the American Civil War. Despite its strong defensive position, the Confederate army of Lt. Gen. Jub ...

, capturing much of Early's artillery and 1,000 men, as well as inflicting about 1,235 casualties including the popular Sandie Pendleton

Alexander Swift "Sandie" Pendleton (September 28, 1840 – September 23, 1864) was an officer on the staff of Confederate Generals Thomas J. Jackson, Richard S. Ewell and Jubal A. Early during the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Sand ...

. In a surprise attack the following month, on October 19, 1864, Early's Confederates initially routed two thirds of the Union army at the Battle of Cedar Creek

The Battle of Cedar Creek, or Battle of Belle Grove, was fought on October 19, 1864, during the American Civil War. The fighting took place in the Shenandoah Valley of Northern Virginia, near Cedar Creek, Middletown, and the Valley Pike. D ...

. In his post-battle dispatch to Lee, Early noted that his troops were hungry and exhausted and claimed they broke ranks to pillage the Union camp, which allowed Sheridan critical time to rally his demoralized troops and turn their morning defeat into an afternoon victory. However, he privately conceded he had hesitated rather than pursue the advantage, and another key subordinate, Dodson Ramseur, was wounded, captured and died the next day despite the best efforts of Union and Confederate surgeons. Furthermore, one of Early's key subordinates, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, in his memoirs written in 1908 (after the irascible Early's death), also blamed Early's indecision rather than the troops for the afternoon rout.

Although distracting thousands of Union troops from the action around Petersburg and Richmond for months, Early had also lost the confidence of former Virginia governor Extra Billy Smith, who told Lee that troops no longer considered Early "a safe commander." Lee ordered most of the remaining Second Corps to rejoin the Army of Northern Virginia defending Petersburg by late November, leaving Early to defend the entire Valley with a brigade of infantry and some cavalry under Lunsford L. Lomax. When Sheridan's troops nearly destroyed the Confederates at Waynesboro on March 2, 1865, Early could not evacuate his men (many of whom were captured), nor artillery and supplies. He barely escaped capture with his cousin Peter Hairston and a few members of his staff, returning almost alone to Petersburg. Hairston returned to one of his plantations near Danville, Virginia

Danville is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, located in the Southside Virginia region and on the fall line of the Dan River. It was a center of tobacco production and was an area of Confederate activit ...

, where Confederate President Jefferson Davis fled to stay with slave trader and financier William Sutherlin.

Lee, however, would not put Early back in command of the Second Corps there because his former subordinate Gordon was handling matters satisfactorily, and the press and other commanders suggested the recent disasters made Early unacceptable to the troops. Lee told Early to go home and wait, then relieved Early of his command on March 30, writing:

Thus ended Early's Confederate career.

Postbellum career

When the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865 Early escaped to Texas on horseback, hoping to find a Confederate force that had not surrendered. He proceeded to

When the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865 Early escaped to Texas on horseback, hoping to find a Confederate force that had not surrendered. He proceeded to Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, and from there sailed to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and finally reached (the then Province of) Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Despite his former Unionist stance, Early declared himself unable to live under the same government as the Yankee. While living in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

with some financial support from his father and elder brother, Early wrote ''A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, in the Confederate States of America'' (1866), which focused on his Valley Campaign. The book became the first published by a major general about the war. Early spent the rest of his life defending his actions during the war and became among the most vocal in justifying the Confederate cause, fostering what became known as the Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

movement.

President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

pardoned Early and many other prominent Confederates in 1869, but Early took pride in remaining an "unreconstructed rebel", and thereafter wore only suits of "Confederate gray" cloth. He returned to Lynchburg, Virginia, and resumed his legal practice about a year before the 1870 death of General Robert E. Lee. However, Early's father died in 1870, and the mother of his four children (whom he had never married) married another man in 1871. Early spent the rest of his life in "illness and squalor so severe that it reduced him to continual begging from family and friends." In an 1872 speech on the anniversary of General Lee's death, Early claimed inspiration from two letters Lee had sent him in 1865. In Lee's published farewell order to the Army of Northern Virginia, the general had noted the "overwhelming resources and numbers" that the Confederate army had fought against. In one letter to Early, Lee requested information about enemy strengths from May 1864 to April 1865, the war's last year, in which his army fought against Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

and the Siege of Petersburg). Lee wrote, "My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity, and do justice to our brave Soldiers."Gallagher & Nolan, p. 12. Lee also wrote, "I have not thought proper to notice, or even to correct misrepresentations of my words & acts. We shall have to be patient, & suffer for awhile at least. ... At present the public mind is not prepared to receive the truth."

In his final years, Early became an outspoken proponent of

In his final years, Early became an outspoken proponent of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

, which he believed to justified by his religion; he despised abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. In the preface to his memoirs, Early characterized former slaves as "barbarous natives of Africa" and considered them "in a civilized and Christianized condition" as a result of their enslavement. He continued:

Despite Lee's avowed desire for reconciliation with his former West Point colleagues who remained with the Union and with Northerners more generally, Early became an outspoken and vehement critic of Lieutenat General James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his ...

and particularly criticized his actions at the Battle of Gettysburg and also took issue with him and other former Confederates who after the war worked with Republicans and African Americans. Early also often criticized former Union General (later President) Ulysses S. Grant as a "butcher."

In 1873, Early was elected president of the Southern Historical Society

The Southern Historical Society was an American organization founded to preserve archival materials related to the government of the Confederate States of America and to document the history of the Civil War.J. William Jones

J. William Jones (25 September 1836 – 17 March 1909) was an American Southern Baptist preacher and writer who became known for his evangelism and devotion to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. During the American Civil War of 1861–1 ...

. With the support of former Confederate General William N. Pendleton, who like Jones ministered in Lexington, Virginia, after the war, Early also became the first president of the Lee Monument Association, and of the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia. Beginning around 1877, Early and former Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard supported themselves in part as officials of the (reputedly then corrupt) Louisiana Lottery. Early also corresponded with and visited former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who retired to Mississippi's Gulf Coast near to write his own memoirs. Former Confederate First Lady Varina Davis

Varina Anne Banks Howell Davis (May 7, 1826 – October 16, 1906) was the only First Lady of the Confederate States of America, and the longtime second wife of President Jefferson Davis. She moved to a house in Richmond, Virginia, in mid- ...

, while also furthering the Lost Cause and corresponding with Early, characterized Early as a "crabby bachelor with a squeaky, high-pitched voice".

Death and legacy

Early tripped and fell down granite stairs at theLynchburg, Virginia

Lynchburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. First settled in 1757 by ferry owner John Lynch, the city's population was 79,009 at the 2020 census. Located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mounta ...

, post office on February 15, 1894. A medical examination found no broken nor fractured bones, but noted Early suffered from back pain and mental confusion. He failed to recover during the next few weeks and died quietly at home on March 2, holding the hand of U.S. Sen. John Warwick Daniel

John Warwick Daniel (September 5, 1842June 29, 1910) was an American lawyer, author, and Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia who promoted the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. Daniel served in both houses of the Virginia General Assemb ...

. Local obituaries speculated a net worth at $200,000 to $300,000. His doctor did not specify an exact cause on the death certificate. Virginia's flag flew at half-staff over the Capitol the afternoon of the funeral, and cannons boomed 36 times at five minute intervals. A procession of VMI cadets, 300 Confederate veterans and local militia accompanied the flag-draped casket and riderless horse with reversed stirrups to St. Paul's Church. During the brief service, Rev. T. M. Carson, a veteran of Early's Valley Campaign, testified as to "the almost countless forces of the enemy."Cooling p. 143 Another, simple service, taps and a farewell kiss by one of Early's "noblest and bravest followers" concluded with Early's burial at Spring Hill Cemetery in Lynchburg. Nearby lay (distant) family members Captain Robert D. Early (killed in the Battle of the Wilderness, May 5, 1864) and his brother William (killed at the Battle of Five Forks

The Battle of Five Forks was fought on April 1, 1865, southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, around the road junction of Five Forks, Dinwiddie County, at the end of the Siege of Petersburg, near the conclusion of the American Civil War.

The Union ...

, April 1, 1865) and their parents, as well as Confederate generals Thomas T. Munford

Thomas Taylor Munford (March 29, 1831 – February 27, 1918) was an American farmer, iron, steel and mining company executive and Confederate colonel and acting brigadier general during the American Civil War.

Biography

Munford was born in ...

and James Dearing

James Dearing (April 25, 1840 – April 22, 1865) was a Confederate States Army officer during the American Civil War who served in the artillery and cavalry. Dearing entered West Point in 1858 and resigned on April 22, 1861, when Virginia se ...

.

The Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

has some of his papers. The Virginia Historical Society

The Virginia Museum of History and Culture founded in 1831 as the Virginia Historical and Philosophical Society and headquartered in Richmond, Virginia, is a major repository, research, and teaching center for Virginia history. It is a private, n ...

holds some of his papers, along with other members of the Early family. The Library of Virginia and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have Hairston family papers, but they barely mention activities during the American Civil War, other than selling provisions to the Confederacy.

The Lost Cause that Early promoted and espoused was continued by memorial associations such as the United Confederate Veterans (founded 1889) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

(founded 1894), as well as by his niece Ruth Hairston Early. Jubal Early's book, ''Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War between the States'', was published posthumously in 1912. Jubal Early's book, ''The Heritage of the South: a history of the introduction of slavery; its establishment from colonial times and final effect upon the politics of the United States'', was published posthumously in 1915. Historians, including Douglas Southall Freeman

Douglas Southall Freeman (May 16, 1886 – June 13, 1953) was an American historian, biographer, newspaper editor, radio commentator, and author. He is best known for his multi-volume biographies of Robert E. Lee and George Washington, for both ...

(who grew up in Lynchburg near the former Early home and remembered relatives' pointing out the stooped and grumbling Early as a bogeyman-type warning), espoused the Lost Cause to greater or lesser degrees until the 1960s, arguing the concept helped Southerners to cope with the dramatic social, political, and economic changes in the postbellum era, including Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

.Ulbrich, p. 1222. Early's biographer, Gary Gallagher, noted that Early understood the struggle to control public memory of the war, and that he "worked hard to help shape that memory, and ultimately enjoyed more success than he probably imagined possible." Other modern historians such as sociologist James Loewen

James William Loewen (February 6, 1942August 19, 2021) was an American sociologist, historian, and author. He was best known for his 1995 book, '' Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong''.

Early life

Loewen ...

, author of ''The Truth About Columbus'', believed Early's views fomented racial hatred.

Honors

Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

was named ''General Jubal A. Early.'' Early's name was removed in 2020, and it is now called Historic White's Ferry.

* A major thoroughfare in Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is the most north western independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Frederick County, although the two are separate jurisdictions. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Winchester wit ...

, is named "Jubal Early Drive" in his honor.

* Virginia Route 116 from Roanoke City to Virginia Route 122 in Franklin County is named after him, the "Jubal Early Highway," and passes his birthplace, as identified by a historical highway marker. In Roanoke County, it is referred to as "JAE Valley Road," incorporating Jubal Anderson Early's initials.

* His childhood home, the Jubal A. Early House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

in 1997 and maintained in part by a private foundation

* Fort Early and Jubal Early Monument can be found in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Streets named after him