José de San Martín on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and central parts of South America's successful struggle for independence from the

San Martín took part in several Spanish campaigns in North Africa, fighting in Melilla and in Oran against the

San Martín took part in several Spanish campaigns in North Africa, fighting in Melilla and in Oran against the

Once again in Buenos Aires, San Martín and his wife attended to the first official performance of the

Once again in Buenos Aires, San Martín and his wife attended to the first official performance of the

The absolutist restoration in Spain and the growing influence of Artigas generated a political crisis in Buenos Aires, forcing Posadas to resign. Alvear became the new Supreme Director, but had to resign after three months. San Martín's plan was complicated as well by the

The absolutist restoration in Spain and the growing influence of Artigas generated a political crisis in Buenos Aires, forcing Posadas to resign. Alvear became the new Supreme Director, but had to resign after three months. San Martín's plan was complicated as well by the

Although the Congress of Tucumán had already formalized the flag of Argentina, the Army of the Andes did not use it, choosing a banner with two columns, light blue and white, and a coat of arms roughly similar to the

Although the Congress of Tucumán had already formalized the flag of Argentina, the Army of the Andes did not use it, choosing a banner with two columns, light blue and white, and a coat of arms roughly similar to the

The columns that crossed the Andes began to take military actions. The column in the north led by Cabot defeated the royalists in Salala, seized Coquimbo and then Copiapó. In the south, Ramón Freire captured

The columns that crossed the Andes began to take military actions. The column in the north led by Cabot defeated the royalists in Salala, seized Coquimbo and then Copiapó. In the south, Ramón Freire captured

Three deputies from Coquimbo, Santiago and Concepción organized a new government, and proposed San Martín as Supreme Director of Chile. He declined the offer and proposed O'Higgins in his stead: he recommended that the Supreme Director should be someone from Chile. San Martín would instead organize the navy to take the fight to Peru. He established a local chapter of the Lodge of Rational Knights, named as Logia Lautaro, in reference to

Three deputies from Coquimbo, Santiago and Concepción organized a new government, and proposed San Martín as Supreme Director of Chile. He declined the offer and proposed O'Higgins in his stead: he recommended that the Supreme Director should be someone from Chile. San Martín would instead organize the navy to take the fight to Peru. He established a local chapter of the Lodge of Rational Knights, named as Logia Lautaro, in reference to

The failure to liberate Talcahuano was followed by naval reinforcements from the North. The viceroy of Peru sent Mariano Osorio in an attempt to reconquer Chile. The royalists would then advance by land from south to north towards Santiago. San Martín thought that it was not possible to defend Concepción, so he ordered O'Higgins to leave the city. 50,000 Chileans took cattle and grain and moved north, burning everything else, so that they did not leave supplies for the royalists. As he had done with the Tucumán Congress, San Martín urged a declaration of independence, to legitimize the government and the military actions. The

The failure to liberate Talcahuano was followed by naval reinforcements from the North. The viceroy of Peru sent Mariano Osorio in an attempt to reconquer Chile. The royalists would then advance by land from south to north towards Santiago. San Martín thought that it was not possible to defend Concepción, so he ordered O'Higgins to leave the city. 50,000 Chileans took cattle and grain and moved north, burning everything else, so that they did not leave supplies for the royalists. As he had done with the Tucumán Congress, San Martín urged a declaration of independence, to legitimize the government and the military actions. The

San Martín made a brief reconnaissance of the royalist army, and noticed several flaws in their organization. Feeling secure of victory, he claimed that "Osorio is clumsier than I thought. Today's triumph is ours. The sun as witness!". The battle began at 11:00 am. The patriot artillery on the right fired on the royalist infantry on the left. Manuel Escalada led mounted grenadiers to capture the royalist artillery, turning them against their owners. Burgos' regiment severely punished the patriot left wing, mainly composed of emancipated slaves, and took 400 lives. San Martín ordered the mounted grenadiers led by Hilarión de la Quintana to charge against the regiment. The firing suddenly ended and royalists began to fight with sword bayonets, under the cries "Long live the king!" and "Long live the homeland!" respectively. Finally, the royalists ended their cries and began to disperse.

When the regiment of Burgos realized that their line was broken, they stopped resisting, and the soldiers began to disperse. The cavalry pursued and killed most of them. At the end of the battle, the royalists had been trapped among the units of Las Heras in the west, Alvarado in the middle, Quintana in the east and the cavalries of Zapiola and Freire. Osorio tried to fall back to the hacienda "Lo Espejo" but could not reach it, so he tried to escape to Talcahuano. Ordóñez made his last stand at that hacienda, where 500 royalists died.

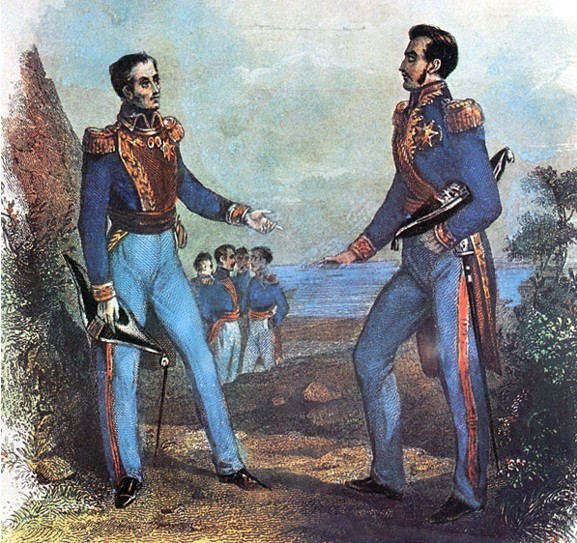

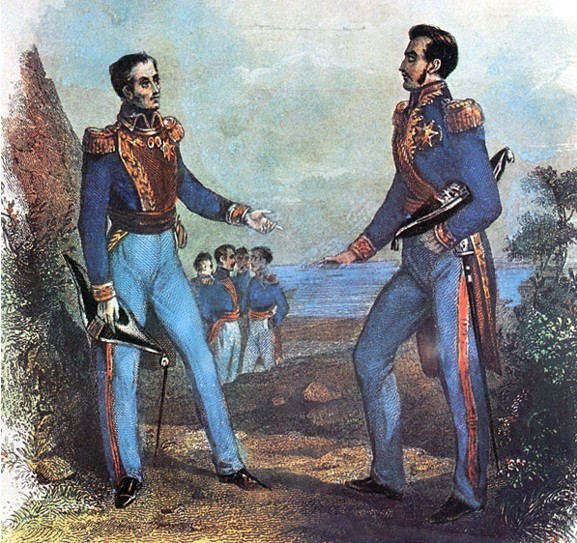

The battle ended in the afternoon. O'Higgins, still injured by the wound received in Cancha Rayada, arrived during the final action at the hacienda. He claimed "Glory to the savior of Chile!", in reference to San Martín, who praised him for going to the battlefield with his unhealed wound. They made an embrace on their horses, now known as the "Embrace of Maipú".

The battle of Maipú secured Chilean independence. Except for Osorio, who escaped with 200 cavalry, all top royalist military leaders were captured. All their armed forces were either killed or captured, and all their artillery, weapons, military hospitals, money and resources were lost. The victory was praised by Güemes, Bolívar and the international press.

San Martín made a brief reconnaissance of the royalist army, and noticed several flaws in their organization. Feeling secure of victory, he claimed that "Osorio is clumsier than I thought. Today's triumph is ours. The sun as witness!". The battle began at 11:00 am. The patriot artillery on the right fired on the royalist infantry on the left. Manuel Escalada led mounted grenadiers to capture the royalist artillery, turning them against their owners. Burgos' regiment severely punished the patriot left wing, mainly composed of emancipated slaves, and took 400 lives. San Martín ordered the mounted grenadiers led by Hilarión de la Quintana to charge against the regiment. The firing suddenly ended and royalists began to fight with sword bayonets, under the cries "Long live the king!" and "Long live the homeland!" respectively. Finally, the royalists ended their cries and began to disperse.

When the regiment of Burgos realized that their line was broken, they stopped resisting, and the soldiers began to disperse. The cavalry pursued and killed most of them. At the end of the battle, the royalists had been trapped among the units of Las Heras in the west, Alvarado in the middle, Quintana in the east and the cavalries of Zapiola and Freire. Osorio tried to fall back to the hacienda "Lo Espejo" but could not reach it, so he tried to escape to Talcahuano. Ordóñez made his last stand at that hacienda, where 500 royalists died.

The battle ended in the afternoon. O'Higgins, still injured by the wound received in Cancha Rayada, arrived during the final action at the hacienda. He claimed "Glory to the savior of Chile!", in reference to San Martín, who praised him for going to the battlefield with his unhealed wound. They made an embrace on their horses, now known as the "Embrace of Maipú".

The battle of Maipú secured Chilean independence. Except for Osorio, who escaped with 200 cavalry, all top royalist military leaders were captured. All their armed forces were either killed or captured, and all their artillery, weapons, military hospitals, money and resources were lost. The victory was praised by Güemes, Bolívar and the international press.

San Martín made a new request for ships to Bowles, but received no answer. He moved again to Buenos Aires, to make a similar request. He arrived to Mendoza a few days after the execution of the Chileans

San Martín made a new request for ships to Bowles, but received no answer. He moved again to Buenos Aires, to make a similar request. He arrived to Mendoza a few days after the execution of the Chileans

Although Artigas was defeated by the Luso-Brazilian armies, his allies

Although Artigas was defeated by the Luso-Brazilian armies, his allies

As hostilities renewed, San Martín organized several guerrilla groups in the countryside, and laid siege to Lima, but did not force his entry, as he did not want to appear as a conqueror to the local population. However, De la Serna suddenly left the city with his army, for unknown reasons. San Martín called for an open cabildo to discuss the independence of the country, which was agreed. With this approval, the authority in Lima, the support of the northern provinces and the port of El Callao under siege, San Martín declared the independence of Peru on 28 July 1821. The war, however, had not ended yet.

Unlike Chile, Peru had no local politicians of the stature of O'Higgins, so San Martín became the leader of the government, even though he did not want to. He was appointed Protector of Peru. As Peruvian society was highly conservative, San Martín did not take the liberal ideas too far immediately. The provisional statutes contained few changes and ratified several existing laws. All the types of servitude imposed on the natives, such as mita and yanaconazgo, were abolished, and the natives received citizenship. He did not abolish slavery completely, as Peru had 40,000 slaveowners, and declared "

As hostilities renewed, San Martín organized several guerrilla groups in the countryside, and laid siege to Lima, but did not force his entry, as he did not want to appear as a conqueror to the local population. However, De la Serna suddenly left the city with his army, for unknown reasons. San Martín called for an open cabildo to discuss the independence of the country, which was agreed. With this approval, the authority in Lima, the support of the northern provinces and the port of El Callao under siege, San Martín declared the independence of Peru on 28 July 1821. The war, however, had not ended yet.

Unlike Chile, Peru had no local politicians of the stature of O'Higgins, so San Martín became the leader of the government, even though he did not want to. He was appointed Protector of Peru. As Peruvian society was highly conservative, San Martín did not take the liberal ideas too far immediately. The provisional statutes contained few changes and ratified several existing laws. All the types of servitude imposed on the natives, such as mita and yanaconazgo, were abolished, and the natives received citizenship. He did not abolish slavery completely, as Peru had 40,000 slaveowners, and declared "

San Martín thought that if he joined forces with Bolívar he would be able to defeat the remnant royalist forces in Peru. Both liberators would meet in Quito, so San Martín appointed Torre Tagle to manage the government during his absence. Bolívar was unable to meet San Martín at the arranged date, so San Martín returned to Lima, but still left Tagle in government. Bolívar moved from Quito to Guayaquil, which secured its independence. There were discussions on the future of the region: some factions wanted to join Colombia, others to join Peru, and others to become a new nation. Bolívar ended the discussion by annexing Guayaquil into Colombia. There was Peruvian pressure on San Martín to do a similar thing, to annex Guayaquil to Peru.

The

San Martín thought that if he joined forces with Bolívar he would be able to defeat the remnant royalist forces in Peru. Both liberators would meet in Quito, so San Martín appointed Torre Tagle to manage the government during his absence. Bolívar was unable to meet San Martín at the arranged date, so San Martín returned to Lima, but still left Tagle in government. Bolívar moved from Quito to Guayaquil, which secured its independence. There were discussions on the future of the region: some factions wanted to join Colombia, others to join Peru, and others to become a new nation. Bolívar ended the discussion by annexing Guayaquil into Colombia. There was Peruvian pressure on San Martín to do a similar thing, to annex Guayaquil to Peru.

The

After his retirement, San Martín intended to live in Cuyo. Although the war of independence had ended in the region, the Argentine Civil Wars continued. The unitarians wanted to organize the country as a

After his retirement, San Martín intended to live in Cuyo. Although the war of independence had ended in the region, the Argentine Civil Wars continued. The unitarians wanted to organize the country as a

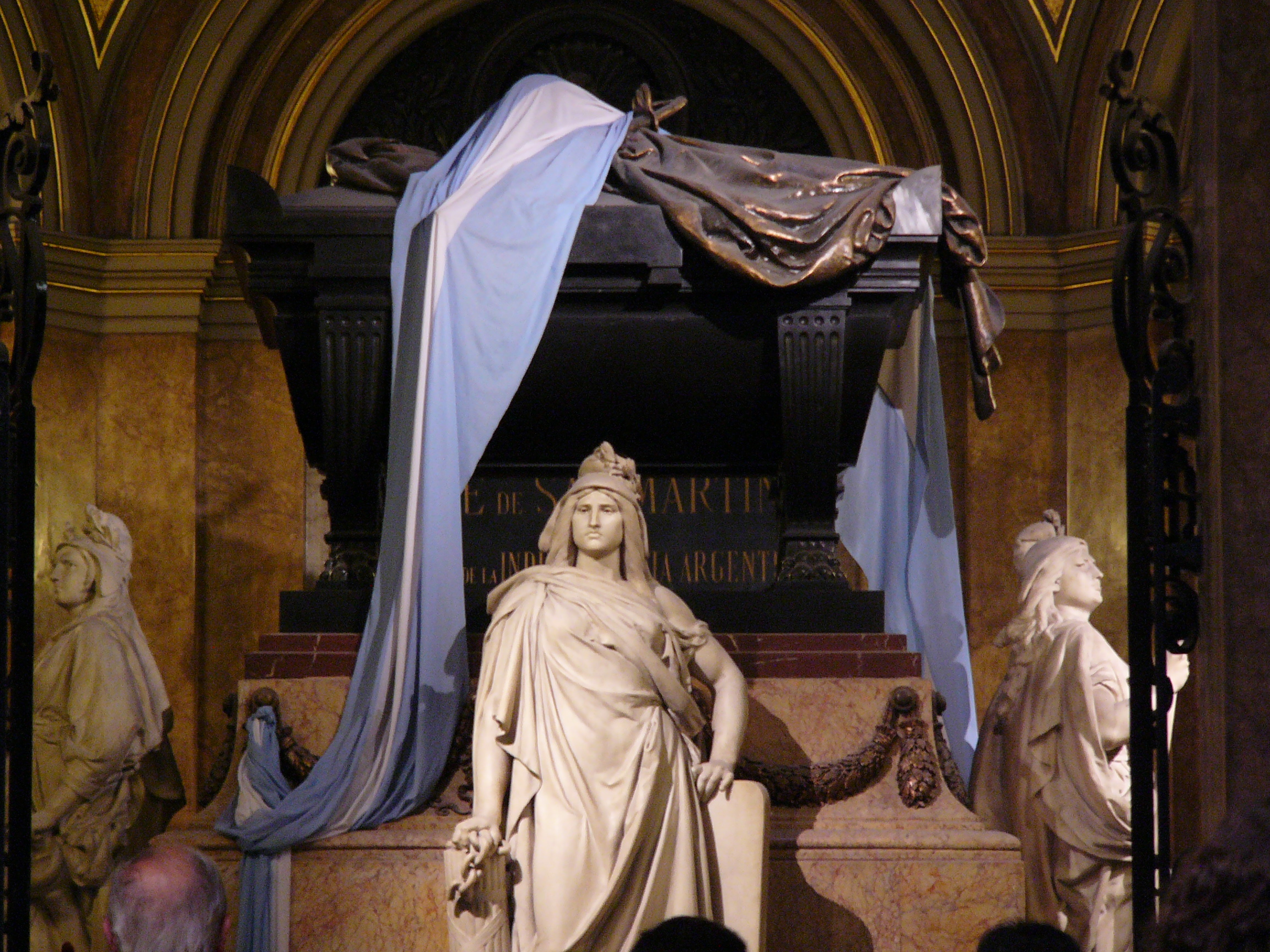

José de San Martín died on 17 August 1850, in his house at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. Between 1850 and 1861, his corpse was buried in the crypt of the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Boulogne. He requested in his will to be taken to the cemetery without any funeral, and to be moved to Buenos Aires thereafter. Balcarce informed Rosas and the foreign minister Felipe Arana of San Martín's death. Balcarce oversaw the

José de San Martín died on 17 August 1850, in his house at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. Between 1850 and 1861, his corpse was buried in the crypt of the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Boulogne. He requested in his will to be taken to the cemetery without any funeral, and to be moved to Buenos Aires thereafter. Balcarce informed Rosas and the foreign minister Felipe Arana of San Martín's death. Balcarce oversaw the

San Martín was first acclaimed as a national hero of Argentina by the Federals, both during his life and immediately after his death. The unitarians still resented his refusal to aid the Supreme Directors with the

San Martín was first acclaimed as a national hero of Argentina by the Federals, both during his life and immediately after his death. The unitarians still resented his refusal to aid the Supreme Directors with the  An equestrian statue of the General was erected in Boulogne-sur-Mer; the statue was inaugurated on 24 October 1909, at a ceremony attended by several units from the Argentine military. The statue was erected through purely private initiative, with the support of national government of Argentina, the municipal council of Buenos Aires and a public funding campaign. The statue is 10m high, on a 4m by 6m base; it is well known to locals. Located on the beach, it was virtually untouched by the numerous bombings campaigns during both world wars.

There is a

An equestrian statue of the General was erected in Boulogne-sur-Mer; the statue was inaugurated on 24 October 1909, at a ceremony attended by several units from the Argentine military. The statue was erected through purely private initiative, with the support of national government of Argentina, the municipal council of Buenos Aires and a public funding campaign. The statue is 10m high, on a 4m by 6m base; it is well known to locals. Located on the beach, it was virtually untouched by the numerous bombings campaigns during both world wars.

There is a

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

who served as the Protector of Peru. Born in Yapeyú, Corrientes

Yapeyú is a town in the province of Corrientes, Argentina, in the San Martín Department. It has about 2,000 inhabitants as per the , and it is known throughout the country because it was the birthplace of General José de San Martín (1778&nda ...

, in modern-day Argentina, he left the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata ( es, Virreinato del Río de la Plata or es, Virreinato de las Provincias del Río de la Plata) meaning "River of the Silver", also called " Viceroyalty of the River Plate" in some scholarly writings, i ...

at the early age of seven to study in Málaga, Spain.

In 1808, after taking part in the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

against France, San Martín contacted South American supporters of independence from Spain in London. In 1812, he set sail for Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

and offered his services to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata), earlier known as the United Provinces of South America ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas de Sudamérica), was a name adopted in 1816 by the Co ...

, present-day Argentina. After the Battle of San Lorenzo

The Battle of San Lorenzo was fought on 3 February 1813 in San Lorenzo, Santa Fe, San Lorenzo, Argentina, then part of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. The royalist troops, were composed of militiamen recruited in Montevideo und ...

and time commanding the Army of the North

The Army of the North ( es, link=no, Ejército del Norte), contemporaneously called Army of Peru, was one of the armies deployed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in the Spanish American wars of independence. Its objective was fre ...

during 1814, he organized a plan to defeat the Spanish forces that menaced the United Provinces from the north, using an alternative path to the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed fro ...

. This objective first involved the establishment of a new army, the Army of the Andes

The Army of the Andes ( es, Ejército de los Andes) was a military force created by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Argentina) and mustered by general José de San Martín in his campaign to free Chile from the Spanish Empire. In 181 ...

, in Cuyo Province

The Province of Cuyo was a historical province of Argentina. Created on 14 November 1813 by a decree issued by the Second Triumvirate, it had its capital in Mendoza, and was composed of the territories of the present-day Argentine provinces of ...

, Argentina. From there, he led the Crossing of the Andes

The Crossing of the Andes ( es, Cruce de los Andes) was one of the most important feats in the Argentine and Chilean wars of independence, in which a combined army of Argentine soldiers and Chilean exiles invaded Chile crossing the Andes r ...

to Chile, and triumphed at the Battle of Chacabuco

The Battle of Chacabuco, fought during the Chilean War of Independence, occurred on February 12, 1817. The Army of the Andes of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, led by Captain–General José de San Martín, defeated a Spanish fo ...

and the Battle of Maipú (1818), thus liberating Chile from royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

rule. Then he sailed to attack the Spanish stronghold of Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

, Peru.

On 12 July 1821, after seizing partial control of Lima, San Martín was appointed Protector of Peru, and Peruvian independence was officially declared on 28 July. On 26 July 1822, after a closed-door meeting with fellow ' Simón Bolívar at Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

, Ecuador, Bolívar took over the task of fully liberating Peru. San Martín unexpectedly left the country and resigned the command of his army, excluding himself from politics and the military, and moved to France in 1824. The details of that meeting would be a subject of debate by later historians.

San Martín is regarded as a national hero of Argentina, Chile, and Peru, a great military commander, and one of the Liberators of Spanish South America. The Order of the Liberator General San Martín

The Order of the Liberator General San Martín ( es, Orden del Libertador General San Martín) is the highest decoration in Argentina. It is awarded to foreign politicians or military, deemed worthy of the highest recognition from Argentina. It is ...

('), created in his honor, is the highest decoration conferred by the Argentine government.

Early life

José de San Martín's father, Juan de San Martín, son of Andrés de San Martín and Isidora Gómez, was born in the town of Cervatos de la Cueza, in the currentProvince of Palencia

Palencia is a Provinces of Spain, province of northern Spain, in the northern part of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Castile-Leon, Castile and León in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. It is bordered by the provi ...

(former Kingdom of León, in Spain) and was lieutenant governor of the department. He served as a military man to the Spanish Crown and in 1774 he was appointed Governor of the Yapeyú Department, part of the Government of the Guaraní Missions, created to administer the thirty Guaraní Jesuit missions, after the order was expelled from Hispanic America by Carlos III in 1767. based in Yapeyú reduction, and Gregoria Matorras del Ser. He was born in Yapeyú, Corrientes

Yapeyú is a town in the province of Corrientes, Argentina, in the San Martín Department. It has about 2,000 inhabitants as per the , and it is known throughout the country because it was the birthplace of General José de San Martín (1778&nda ...

, an Indian reduction of Guaraní people

Guarani are a group of culturally-related indigenous peoples of South America. They are distinguished from the related Tupi by their use of the Guarani language. The traditional range of the Guarani people is in present-day Paraguay between the ...

. The exact year of his birth is disputed, as there are no records of his baptism. Later documents formulated during his life, such as passports, military career records and wedding documentation, gave him varying ages. Most of these documents point to his year of birth as either 1777 or 1778. The family moved to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

in 1781, when San Martín was three or four years old.

Juan requested to be transferred to Spain, leaving the Americas in 1783. The family settled in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

, but as Juan was unable to earn a promotion, they moved to Málaga. Once in the city, San Martín enrolled in Málaga's school of temporalities, beginning his studies in 1785. It is unlikely that he finished the six-year-long elementary education, before he enrolled in the Regiment of Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

in 1789, when he reached the required age of 11. He began his military career as a cadet in the Murcian Infantry Unit.

Military career in Europe

San Martín took part in several Spanish campaigns in North Africa, fighting in Melilla and in Oran against the

San Martín took part in several Spanish campaigns in North Africa, fighting in Melilla and in Oran against the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

in 1791, among others. His rank was raised to Sub-Lieutenant in 1793, at the age of 15. He began a naval career during the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

, when Spain was allied with France against Great Britain, during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

. His ship ''Santa Dorotea'' was captured by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, who kept him as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

for some time. Soon afterward, he continued to fight in southern Spain, mainly in Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

with the rank of Second Captain of light infantry. He continued to fight Portugal on the side of Spain in the War of the Oranges

The War of the Oranges ( pt, Guerra das Laranjas; french: Guerre des Oranges; es, Guerra de las Naranjas) was a brief conflict in 1801 in which Spanish forces, instigated by the government of France, and ultimately supported by the French mil ...

in 1801. He was promoted to captain in 1804. During his stay in Cádiz he was influenced by the ideas of the Spanish Enlightenment.

At the outbreak of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

in 1808, San Martín was named adjutant of Francisco María Solano Ortiz de Rosas. Rosas, suspected of being an ''afrancesado

''Afrancesado'' (, ; " Francophile" or "turned-French", lit. "Frenchified" or "French-alike") refers to the Spanish and Portuguese partisan of Enlightenment ideas, Liberalism or the French Revolution.

In principle, ''afrancesados'' were upper- ...

'', was killed by a popular uprising which overran the barracks and dragged his corpse in the streets. San Martín was appointed to the armies of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The t ...

, and led a battalion of volunteers. In June 1808 his unit became incorporated into a guerrilla force led by Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón. He was nearly killed during the battle of Arjonilla, but was saved by Sergeant Juan de Dios. On 19 July 1808, Spanish and French forces engaged in the battle of Bailén

The Battle of Bailén was fought in 1808 between the Spanish Army of Andalusia, led by Generals Francisco Castaños and Theodor von Reding, and the Imperial French Army's II corps d'observation de la Gironde under General Pierre Dupont de l ...

, a Spanish victory that allowed the Army of Andalusia to attack and seize Madrid. For his actions during this battle, San Martín was awarded a gold medal, and his rank raised to lieutenant colonel. On 16 May 1811, he fought in the battle of Albuera

The Battle of Albuera (16 May 1811) was a battle during the Peninsular War. A mixed British, Spanish and Portuguese corps engaged elements of the French Armée du Midi (Army of the South) at the small Spanish village of Albuera, about south ...

under the command of general William Carr Beresford. By this time, the French armies held most of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

under their control, except for Cádiz.

San Martín resigned from the Spanish army, for controversial reasons, and moved to South America, where he joined the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

. Historians propose several explanations for this action: the common ones are that he missed his native land, that he was in the employ of the British and the congruence of the goals of both wars. The first explanation suggests that when the wars of independence began San Martín thought that his duty was to return to his country and serve in the military conflict. The second explanation suggests that Britain, which would benefit from the independence of the South American countries, sent San Martín to achieve it. The third suggests that both wars were caused by the conflicts between Enlightenment ideas and absolutism, so San Martín still waged the same war; the wars in the Americas only developed separatist goals after the Spanish Absolutist Restoration.

San Martín was initiated in the Lodge of Rational Knights in 1811. They met at the house of Carlos María de Alvear

Carlos María de Alvear (October 25, 1789 in Santo Ángel, Rio Grande do Sul – November 3, 1852 in New York), was an Argentine soldier and statesman, Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in 1815.

Early life

H ...

, other members were José Miguel Carrera

José Miguel Carrera Verdugo (; October 15, 1785 – September 4, 1821) was a Chilean general, formerly Spanish military, member of the prominent Carrera family, and considered one of the founders of independent Chile. Carrera was the most impo ...

, Aldao, Blanco Encalada and other ''criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

'', American-born Spaniards. They agreed to return to their home lands and join the local revolutionary movements. San Martín asked for his retirement from the military, and moved to Britain. He stayed in the country for a short time, and met many other South Americans at a lodge held at the house of Venezuelan general Francisco de Miranda at 27 Grafton Street (now 58 Grafton Way), Bloomsbury, London (the house now has a blue plaque with Miranda's name). Then he sailed to Buenos Aires aboard the British ship ''George Canning'', along with the South Americans Alvear, Francisco José de Vera and Matías Zapiola, and the Spaniards Francisco Chilavert and Eduardo Kailitz. They arrived on 9 March 1812, to serve under the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many ve ...

.

South America

Argentina

A few days after his arrival in Buenos Aires in the United Provinces (formally named the Argentine Republic in 1826), San Martín was interviewed by the First Triumvirate. They appointed him a lieutenant colonel of cavalry, and asked him to create a cavalry unit, as Buenos Aires did not have good cavalry. He began to organize theRegiment of Mounted Grenadiers

The Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers ( es, Regimiento de Granaderos a Caballo) is the name of two Argentine Army regiments of two different time periods: a historic regiment that operated from 1812 to 1826, and a modern cavalry unit that was organiz ...

with Alvear and Zapiola. As Buenos Aires lacked professional military leaders, San Martín was entrusted with the protection of the whole city, but kept focused in the task of building the military unit.

San Martín, Alvear and Zapiola established a local branch of the Lodge of Rational Knights, along with morenists, the former supporters of the late Mariano Moreno. This lodge sought to promote liberal ideas; its secrecy hides whether it was a real Masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

, or a lodge with political goals. It had no ties to the Premier Grand Lodge of England. In September 1812, San Martín married María de los Remedios de Escalada, a 14-year-old girl from one of the local wealthy families.

The lodge organized the Revolution of 8 October 1812 when the terms of office of the triumvirs Manuel de Sarratea

Manuel de Sarratea, (Buenos Aires, 11 August 1774 – Limoges, France, 21 September 1849), was an Argentine diplomat, politician and soldier. He was the son of Martin de Sarratea (1743–1813), of the richest merchant of Buenos-Aires and Tom ...

and Feliciano Chiclana

Feliciano Antonio Chiclana (June 9, 1761 in Buenos Aires – September 17, 1826 in Buenos Aires) was an Argentine lawyer, soldier, and judge.

Biography

Feliciano Chiclana studied at the Colegio de San Carlos and in 1783 he finished with a law ...

ended. Juan Martín de Pueyrredón

Juan Martín de Pueyrredón y O'Dogan (December 18, 1777 – March 13, 1850) was an Argentine general and politician of the early 19th century. He was appointed Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata after the Argentine ...

promoted antimorenist new members, Manuel Obligado and Pedro Medrano, by preventing the vote of three deputies and thus achieving a majority. As this caused a commotion, San Martín and Alvear intervened with their military force, and the Buenos Aires Cabildo

The Cabildo of Buenos Aires ( es, Cabildo de Buenos Aires) is the public building in Buenos Aires that was used as seat of the town council during the colonial era and the government house of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Today the bu ...

disestablished the triumvirate. It was replaced by the Second Triumvirate of Juan José Paso, Nicolás Rodríguez Peña

Nicolás Rodriguez Peña (1775, in Buenos Aires – 1853, in Santiago de Chile) was an Argentine politician. Born in Buenos Aires in April 1775, he worked in commerce which allowed him to amass a considerable fortune. Among his several successfu ...

and Antonio Álvarez Jonte

Antonio Álvarez Jonte (Madrid, 1784 – Pisco, Perú, October 18, 1820) was an Argentine politician. He was born in Madrid in 1784 and moved with parents to Córdoba when young. He studied law at Córdoba University and obtained his doctorat ...

. The new triumvirate called the Assembly of the Year XIII and promoted San Martín to colonel.

San Lorenzo

Montevideo, on the other shore of theRío de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

, was still a royalist stronghold. Argentine general José Rondeau

José Casimiro Rondeau Pereyra (March 4, 1773 – November 18, 1844) was a general and politician in Argentina and Uruguay in the early 19th century.

Life and Politics

He was born in Buenos Aires but soon after his birth, the family moved t ...

laid siege to it, but the Montevidean navy eluded it by pillaging nearby cities. San Martín was sent with the new Regiment to watch the activities in the Paraná River shore.

The Regiment followed the navy from a distance, avoiding detection. They hid in the San Carlos Convent, in San Lorenzo, Santa Fe

San Lorenzo () is a city in the south of the Province of Santa Fe, Argentina, located 23 km north of Rosario, on the western shore of the Paraná River, and forming one end of the Greater Rosario metropolitan area. It is the head town of the ...

. San Martín watched the enemy ships from the top of the convent during the night. The royalists disembarked at dawn, ready to pillage and the regiment charged into battle. San Martín employed a pincer movement

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver holds an important foothold throughout the history of warfare.

The pin ...

to trap the royalists. He led one column and Justo Bermúdez the other.

San Martín's horse was killed during the battle, and his leg was trapped under the corpse of the animal after the fall. A royalist, probably Zabala himself, attempted to kill San Martín while he was trapped under his dead horse where he suffered a saber injury to his face, and a bullet wound to his arm. Juan Bautista Cabral and Juan Bautista Baigorria of San Martín's regiment intervened and saved his life; Cabral was mortally wounded, and died shortly afterwards.

The battle did not have a notable influence on the war and did not prevent further pillage. Montevideo was finally subdued by Admiral William Brown during the Second Banda Oriental campaign. Antonio Zabala, the leader of the Montevidean army, served under San Martín during the crossing of the Andes years later.

Army of the North

Once again in Buenos Aires, San Martín and his wife attended to the first official performance of the

Once again in Buenos Aires, San Martín and his wife attended to the first official performance of the Argentine National Anthem

The "Argentine National Anthem" ( es, Himno Nacional Argentino) is the national anthem of Argentina. Its lyrics were written by the Buenos Aires-born politician Vicente López y Planes and the music was composed by the Spanish musician Blas P ...

, on 28 May 1813 at the Coliseo Theater. Oral tradition has it that the premiere took place on 14 May 1813 at the home of aristocrat Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson, with San Martín also attending, but there is no documentary evidence of that. The lyrics of the new anthem included several references to the secessionist will of the time.

Although they were still allies, San Martín began to distance himself from Alvear, who controlled the Assembly and the lodge. Alvear opposed the merchants and the Uruguayan caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; osp, cabdillo, from Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise definition of ''caudillo'', which is often used interchangeably with " ...

José Gervasio Artigas

José Gervasio Artigas Arnal (; June 19, 1764 – September 23, 1850) was a political leader, military general, statesman and national hero of Uruguay and the broader Río de la Plata region.

He fought in the Latin American wars of in ...

, San Martín thought that it was risky to open such conflicts when the royalists were still a threat. The Army of the North

The Army of the North ( es, link=no, Ejército del Norte), contemporaneously called Army of Peru, was one of the armies deployed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in the Spanish American wars of independence. Its objective was fre ...

, which was operating at the Upper Peru

Upper Peru (; ) is a name for the land that was governed by the Real Audiencia of Charcas. The name originated in Buenos Aires towards the end of the 18th century after the Audiencia of Charcas was transferred from the Viceroyalty of Peru to t ...

, was defeated at the battles of Vilcapugio and Ayohuma, so the triumvirate appointed San Martín to head it, replacing Manuel Belgrano

Manuel José Joaquín del Corazón de Jesús Belgrano y González (3 June 1770 – 20 June 1820), usually referred to as Manuel Belgrano (), was an Argentine public servant, economist, lawyer, politician, journalist, and military leader. He ...

.

San Martín and Belgrano met at the Yatasto relay. The army was in poor condition, and San Martín initially refused to remove Belgrano from the army, as it would hurt the soldiers' morale. However, the supreme director Gervasio Posadas

Gervasio Antonio de Posadas y Dávila (18 June 1757, in Buenos Aires – 2 July 1833, in Buenos Aires) was a member of Argentina's Second Triumvirate from 19 August 1813 to 31 January 1814, after which he served as Supreme Director until 9 Janua ...

(who replaced the triumvirate in government) insisted, and San Martín acted as instructed. San Martín stayed only a few weeks in Tucumán, reorganizing the army and studying the terrain. He also had a positive impression of the guerrilla war waged by Martín Miguel de Güemes

Martín Miguel de Güemes (8 February 1785 – 17 June 1821) was a military leader and popular caudillo who defended northwestern Argentina from the Spain, Spanish royalist army during the Argentine War of Independence.

Biography

Güemes was bor ...

against the royalists, similar to the Peninsular War. It was a defensive war, and San Martín trusted that they could prevent a royalist advance in Jujuy

San Salvador de Jujuy (), commonly known as Jujuy and locally often referred to as San Salvador, is the capital and largest city of Jujuy Province in northwest Argentina. Also, it is the seat of the Doctor Manuel Belgrano Department. It lies near ...

.

San Martín had health problems in April 1814, probably caused by hematemesis

Hematemesis is the vomiting of blood. It is always an important sign. It can be confused with hemoptysis (coughing up blood) or epistaxis (nosebleed), which are more common. The source is generally the upper gastrointestinal tract, typically abo ...

. He temporarily delegated the command of the Army to colonel Francisco Fernández de la Cruz and requested leave to recover. He moved to Santiago del Estero, and then to Córdoba where he slowly recovered. During this time King Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

returned to the throne, began the absolutist restoration and began to organize an attack on the rogue colonies. After an interview with Tomás Guido, San Martín came up with a plan: organize an army in Mendoza, cross the Andes to Chile, and move to Peru by sea; all while Güemes defended the north frontier. This would place him in Peru without crossing the harsh terrain of Upper Peru, where two campaigns had already been defeated. To advance this plan, he requested the governorship of the Cuyo province, which was accepted. He took office on 6 September.

Governor of Cuyo

The absolutist restoration in Spain and the growing influence of Artigas generated a political crisis in Buenos Aires, forcing Posadas to resign. Alvear became the new Supreme Director, but had to resign after three months. San Martín's plan was complicated as well by the

The absolutist restoration in Spain and the growing influence of Artigas generated a political crisis in Buenos Aires, forcing Posadas to resign. Alvear became the new Supreme Director, but had to resign after three months. San Martín's plan was complicated as well by the Disaster of Rancagua

The Battle of Rancagua, also known in Chile as the Disaster of Rancagua, occurred on October 1, 1814, to October 2, 1814, when the Spanish Army under the command of Mariano Osorio defeated the rebel Chilean forces led by Bernardo O’Higgins ...

, a royalist victory that restored absolutism in Chile, ending the '' Patria Vieja'' period. San Martín initially proposed a regular-sized army, simply to reinforce Chile, but changed to propose a larger one, to liberate the country from the occupation. Chileans Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme (; August 20, 1778 – October 24, 1842) was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. He was a wealthy landowner of Basque-Spanish and Irish ancestry. Alth ...

, José Miguel Carrera

José Miguel Carrera Verdugo (; October 15, 1785 – September 4, 1821) was a Chilean general, formerly Spanish military, member of the prominent Carrera family, and considered one of the founders of independent Chile. Carrera was the most impo ...

, Luis Carrera and Manuel Rodríguez, the leaders of the deposed Chilean rule, sought refugee in Cuyo, along with their armies. O'Higgins and Rodríguez were well received, but the Carrera brothers intended to act as a government in exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile ...

. They ignored the local laws of Cuyo, and their soldiers committed acts of vandalism. San Martín imprisoned them and sent them to Buenos Aires. They proposed a plan to liberate Chile, different to the one outlined by San Martín, who rejected it as impractical. This initiated a rivalry between the Carreras and San Martín.

San Martín immediately began to organize the Army of the Andes. He drafted all the citizens who could bear arms and all the slaves from ages 16 to 30, requested reinforcements to Buenos Aires, and reorganized the economy for war production. He took another leave to restore his health four months after taking power, so Alvear appointed Gregorio Perdriel. This appointment was resisted by the Mendoza Cabildo, which ratified San Martín.

The government of San Martín repeated some of the ideas outlined in the ''Operations plan

''Operations plan'' (in Spanish, "Plan de Operaciones") is a secret document attributed to Mariano Moreno, that set harsh ways for the Primera Junta, the first ''de facto'' independent government of Argentina in the 19th century, to achieve its g ...

'', drafted by Mariano Moreno at the beginning of the war. A combination of incentives, confiscations and planned economy allowed the country to provision the army: gunpowder, pieces of artillery, mules and horses, food, military clothing, etc. Mining increased, with increased extraction of lead, copper, saltpeter, sulfur and borax, which had several uses and improved local finances. Hundreds of women wove clothing used by the soldiers. Father José Luis Beltrán headed a military factory of 700 men, which produced rifles and horseshoes. San Martín stayed on good terms with both the government of Buenos Aires and the provincial ''caudillos'', without fully allying with either one. He was able to receive provisions from both. He considered that the war of independence took priority over the civil wars

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

.

The army was not ready as of the summer of 1815, delaying the crossing. Given the harsh conditions on the mountains, the crossing could only be done in the summer season, when there is less snow. Buenos Aires did not send more provisions after the ousting of Alvear. San Martín proposed to resign and serve under Balcarce, if they would support the campaign. San Martín and Guido wrote a report in the autumn of 1816, detailing to the Supreme Director Antonio González de Balcarce the full military plan of operations.

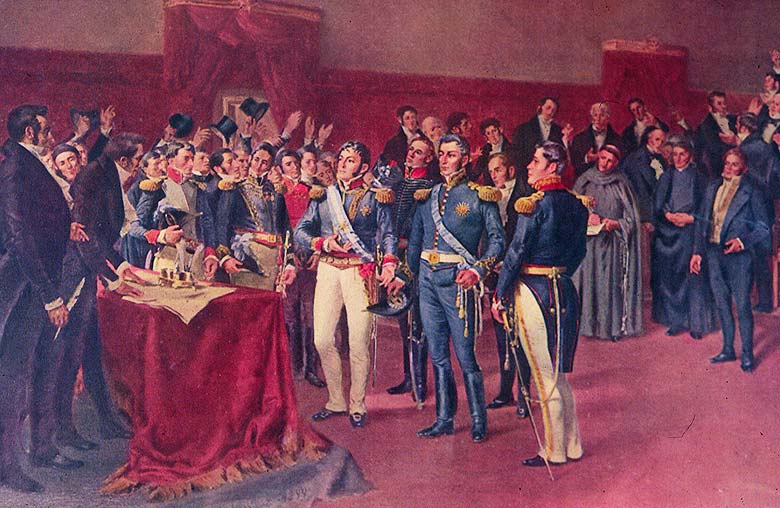

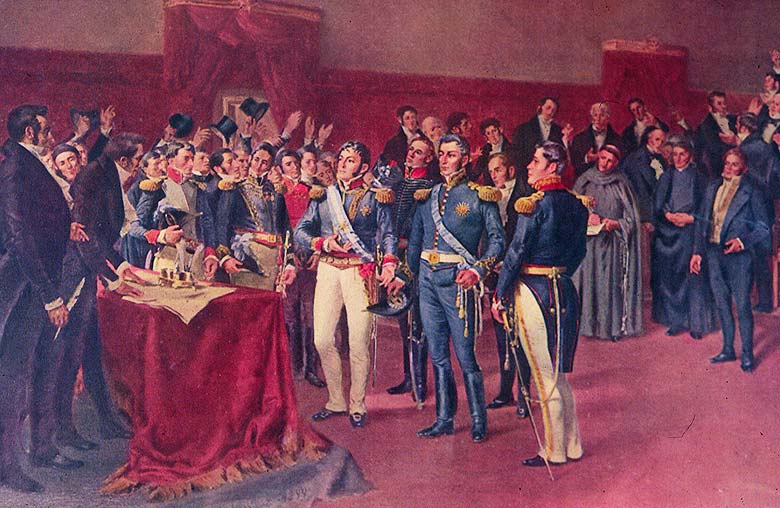

San Martín proposed that the country declare independence immediately, before the crossing. That way, they would be acting as a sovereign nation, and not as a mere rebellion. He had great influence over the Congress of Tucumán

The Congress of Tucumán was the representative assembly, initially meeting in San Miguel de Tucumán, that declared the independence of the United Provinces of South America (modern-day Argentina, Uruguay, part of Bolivia) on July 9, 1816, fro ...

, a Congress with deputies from the provinces, which was established in March 1816. He opposed the appointment of José Moldes, a soldier from Salta who was against the policies of Buenos Aires, as he feared Moldes would break national unity. He rejected proposals to be appointed Supreme Director himself. He supported his friend and lodge member Juan Martín de Pueyrredón

Juan Martín de Pueyrredón y O'Dogan (December 18, 1777 – March 13, 1850) was an Argentine general and politician of the early 19th century. He was appointed Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata after the Argentine ...

for the office. Pueyrredón resumed the military aid to Cuyo. The Congress of Tucumán declared independence on 9 July 1816. Congress discussed the type of government of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata), earlier known as the United Provinces of South America ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas de Sudamérica), was a name adopted in 1816 by the Co ...

(modern Argentina). General Manuel Belgrano, who had made a diplomatic mission to Europe, informed them that independence would be more easily acknowledged by the European powers if the country established a monarchy. For this purpose, Belgrano proposed a plan

A plan is typically any diagram or list of steps with details of timing and resources, used to achieve an objective to do something. It is commonly understood as a temporal set of intended actions through which one expects to achieve a goal.

...

to crown a noble of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

as king (the Sapa Inca dynasty had been dethroned in the 16th century). San Martín supported this proposal, as well as Güemes and most deputies, except for those from Buenos Aires, who undermined the project and prevented its approval.

Needing even more soldiers, San Martín extended the emancipation of slaves to the ages from 14 to 55, and even allowed them to be promoted to higher military ranks. He proposed a similar measure at the national level, but Pueyrredón encountered severe resistance. He included as well the Chileans who escaped Chile after the disaster of Rancagua, and organized them in four units, each one of infantry, cavalry, artillery and dragoons. At the end of 1816, the Army of the Andes had 5,000 men, 10,000 mules and 1,500 horses. San Martin organized military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

, propaganda and disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the L ...

to confuse the royalist armies (such as the specific routes taken in the Andes), boost the national fervor of his army and promote desertion among the royalists.

Crossing of the Andes

Although the Congress of Tucumán had already formalized the flag of Argentina, the Army of the Andes did not use it, choosing a banner with two columns, light blue and white, and a coat of arms roughly similar to the

Although the Congress of Tucumán had already formalized the flag of Argentina, the Army of the Andes did not use it, choosing a banner with two columns, light blue and white, and a coat of arms roughly similar to the Coat of arms of Argentina

The coat of arms of the Argentine Republic or Argentine shield ( es, Escudo de la República Argentina) was established in its current form in 1944, but has its origins in the seal of the General Constituent Assembly of 1813. It is supposed tha ...

. The army did not use the flag of Argentina because it was not exclusively an Argentine army.

Contrary to the common understanding, the crossing of the Andes was not the first time that a military expedition crossed the mountain range. The difference from previous operations was the size of the army, and that it had to be ready for combat right after the crossing. The army was divided in six columns

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression membe ...

, each taking a different path. Colonel Francisco Zelada in La Rioja

La Rioja () is an autonomous community and province in Spain, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, an ...

took the Come-Caballos pass towards Copiapó

Copiapó () is a city and commune in northern Chile, located about 65 kilometers east of the coastal town of Caldera. Founded on December 8, 1744, it is the capital of Copiapó Province and Atacama Region.

Copiapó lies about 800 km nort ...

. Juan Manuel Cabot, in San Juan, moved to Coquimbo

Coquimbo is a port city, commune and capital of the Elqui Province, located on the Pan-American Highway, in the Coquimbo Region of Chile. Coquimbo is situated in a valley south of La Serena, with which it forms Greater La Serena with more than ...

. Ramón Freire and José León Lemos led two columns in the south. The bulk of the armies left from Mendoza. San Martín, O'Higgins and Soler led a column across the Los Patos pass, and Juan Gregorio de Las Heras another one across the Uspallata Pass

The Uspallata Pass, Bermejo Pass or Cumbre Pass, is an Andean pass which provides a route between the wine-growing region around the Argentine city of Mendoza, the Chilean city Los Andes and Santiago, the Chilean capital situated in the central ...

.

The whole operation took nearly a month. The armies took dried food for the soldiers and fodder for the horses, because of the inhospitable conditions. They also consumed garlics and onions, to prevent altitude sickness

Altitude sickness, the mildest form being acute mountain sickness (AMS), is the harmful effect of high altitude, caused by rapid exposure to low amounts of oxygen at high elevation. People can respond to high altitude in different ways. Sympt ...

. Only 4,300 mules and 511 horses survived, less than half the original complement.

Manuel Rodríguez had returned to Chile before the crossing, and began a guerrilla war in Santiago de Chile

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

against the royalists, in support of the upcoming army. He was supported in the south of the city and the countryside. The strategy was to occupy nearby villages, seize the royalists' weapons and flee. The attacks on Melipilla and San Fernando, and a failed one at Curicó, demoralized the royalists.

Chile

Battle of Chacabuco

The columns that crossed the Andes began to take military actions. The column in the north led by Cabot defeated the royalists in Salala, seized Coquimbo and then Copiapó. In the south, Ramón Freire captured

The columns that crossed the Andes began to take military actions. The column in the north led by Cabot defeated the royalists in Salala, seized Coquimbo and then Copiapó. In the south, Ramón Freire captured Talca

Talca () is a city and commune in Chile located about south of Santiago, and is the capital of both Talca Province and Maule Region (7th Region of Chile). As of the 2012 census, the city had a population of 201,142.

The city is an importan ...

. Las Heras routed royalist outposts in Juncalito and Potrerillos. Bernardo O'Higgins, who came from Los Patos pass, defeated the royalists at Las Coimas. This allowed the main columns to gather at Aconcagua valley, meeting at the slopes of Chacabuco. Royalist commander Rafael Maroto

Rafael Maroto Yserns (October 15, 1783 – August 25, 1853) was a Spanish general, known both for his involvement on the Spanish side in the wars of independence in South America and on the Carlist side in the First Carlist War.

Childhood a ...

converged his armies on that location as well. Maroto had 2,450 men and 5 pieces of artillery, San Martín had 3,600 men and 9 pieces of artillery. The misdirection that concealed the path of the bulk of the Army allowed San Martín this advantage, as other royalist forces were scattered in other regions of Chile.

The battle began on 12 February. San Martín organized a pincer movement, with Soler leading the west column and O'Higgins the east one. O'Higgins, eager to avenge the defeat at Rancagua, rushed to the attack, instead of coordinating with Soler. This gave the royalists a brief advantage. San Martín instructed Soler to rush the attack as well. The combined attack was successful and San Martín's column secured the final victory. The battle ended with 600 royalists dead and 500 prisoners, with only 12 deaths and 120 injuries in the Army of the Andes.

The army triumphantly entered Santiago de Chile

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

the following day. Governor Francisco Marcó del Pont

Francisco Casimiro Marcó del Pont y Ángel (; June 25, 1770 – May 19, 1819) was a Spanish soldier and the last Governor of Chile. He was one of the main figures of the Chilean independence process, being the final Spaniard to rule as Royal G ...

attempted to escape to Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

and sail to Peru, but he was captured on 22 February and returned to Santiago. Several other officials were captured as well and sent as prisoners to San Luis, Argentina. San Martín sent Marcó del Pont prisoner to Mendoza.

Patria Nueva

Three deputies from Coquimbo, Santiago and Concepción organized a new government, and proposed San Martín as Supreme Director of Chile. He declined the offer and proposed O'Higgins in his stead: he recommended that the Supreme Director should be someone from Chile. San Martín would instead organize the navy to take the fight to Peru. He established a local chapter of the Lodge of Rational Knights, named as Logia Lautaro, in reference to

Three deputies from Coquimbo, Santiago and Concepción organized a new government, and proposed San Martín as Supreme Director of Chile. He declined the offer and proposed O'Higgins in his stead: he recommended that the Supreme Director should be someone from Chile. San Martín would instead organize the navy to take the fight to Peru. He established a local chapter of the Lodge of Rational Knights, named as Logia Lautaro, in reference to Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who s ...

leader Lautaro

Lautaro (Anglicized as 'Levtaru') ( arn, Lef-Traru " swift hawk") (; 1534? – April 29, 1557) was a young Mapuche toqui known for leading the indigenous resistance against Spanish conquest in Chile and developing the tactics that would conti ...

.

The victory in Chacabuco did not liberate all Chile. Royalist forces still resisted in southern Chile, allied with local Mapuche chiefs. Las Heras occupied Concepción, but failed to occupy Talcahuano

Talcahuano () (From Mapudungun ''Tralkawenu'', "Thundering Sky") is a port city and commune in the Biobío Region of Chile. It is part of the Greater Concepción conurbation. Talcahuano is located in the south of the Central Zone of Chile.

Geo ...

. The royalist resistance lasted for several months, and Talcahuano was only captured when most of the continent was already free.

San Martín left O'Higgins in charge of the Army, and returned to Buenos Aires to request resources for the campaign to Peru. He did not have a good reception this time. Pueyrredón thought that Chile should compensate Buenos Aires for the money invested in their liberation, as the support to San Martín reduced the support to Belgrano, and the Portuguese-Brazilian invasion of the Eastern Bank menaced Buenos Aires. Incapable of financial support, Buenos Aires sent lawyer Manuel Aguirre to the United States, to request aid and acknowledge the declaration of independence. However, the mission failed, as the United States stayed neutral in the conflict because they negotiated the purchase of Florida with Spain. The Chilean José Miguel Carrera

José Miguel Carrera Verdugo (; October 15, 1785 – September 4, 1821) was a Chilean general, formerly Spanish military, member of the prominent Carrera family, and considered one of the founders of independent Chile. Carrera was the most impo ...

had obtained ships on his own after the disaster of Rancagua, which he intended to use to liberate Chile; but as San Martín had already done that, he refused to place his fleet under the Army of the Andes. Carrera was an enemy of O'Higgins and sought to navigate to Chile and depose him, so Pueyrredón imprisoned him, and confiscated his ships.

San Martín requested help from British Admiral William Bowles. He wrote from Chile and expected to find him in Buenos Aires, but Bowles had embarked for Río de Janeiro. Bowles considered that San Martín was more trustworthy than Alvear, and praised his support for monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

. San Martín did not obtain the ships and interrupted the correspondence with Bowles for some months. He returned to Chile; his wife Remedios stayed in Buenos Aires with her daughter Mercedes because of her health problems. Unable to get help from either Buenos Aires or foreign powers, San Martín promoted a more decisive commitment from Chile to finance the navy.

Battle of Cancha Rayada

The failure to liberate Talcahuano was followed by naval reinforcements from the North. The viceroy of Peru sent Mariano Osorio in an attempt to reconquer Chile. The royalists would then advance by land from south to north towards Santiago. San Martín thought that it was not possible to defend Concepción, so he ordered O'Higgins to leave the city. 50,000 Chileans took cattle and grain and moved north, burning everything else, so that they did not leave supplies for the royalists. As he had done with the Tucumán Congress, San Martín urged a declaration of independence, to legitimize the government and the military actions. The

The failure to liberate Talcahuano was followed by naval reinforcements from the North. The viceroy of Peru sent Mariano Osorio in an attempt to reconquer Chile. The royalists would then advance by land from south to north towards Santiago. San Martín thought that it was not possible to defend Concepción, so he ordered O'Higgins to leave the city. 50,000 Chileans took cattle and grain and moved north, burning everything else, so that they did not leave supplies for the royalists. As he had done with the Tucumán Congress, San Martín urged a declaration of independence, to legitimize the government and the military actions. The Chilean Declaration of Independence

The Chilean Declaration of Independence is a document declaring the independence of Chile from the Spanish Empire. It was drafted in January 1818 and approved by Supreme Director Bernardo O'Higgins on 12 February 1818 at Talca, despite being ...

was issued on 18 February 1818, one year after the battle of Chacabuco.

San Martín, Las Heras and Balcarce met in Curicó

Curicó (), meaning "Black Waters" in Mapudungun (originally meaning "Land of Black Water"), is the capital city of the Curicó Province, part of the Maule Region in Chile's central valley.

The province lies between the provinces of Colchagu ...

, and the royalists in Talca

Talca () is a city and commune in Chile located about south of Santiago, and is the capital of both Talca Province and Maule Region (7th Region of Chile). As of the 2012 census, the city had a population of 201,142.

The city is an importan ...

, in a plain known as "Cancha rayada". As the patriots had a numeric advantage, 7,000 against 4,600, Osorio tried to avoid open battle, and tried instead a stealth operation. A spy informed San Martín that Osorio would make a surprise attack in the night, but the army could not be prepared in time. 1,000 soldiers fled, 120 died, and San Martín's assistant was killed. O'Higgins tried to resist with his unit, but retired when he was shot in the arm. Las Heras managed to retire his army in order, saving his 3,500 men. The patriots escaped to Santiago.

Despite the defeat, the soldiers were received as heroes in Santiago. Thanks to Las Heras, a potential disaster for the patriot armies turned into a minor setback. The army was reorganized again, but the deaths, injuries and desertions caused by the defeat at Cancha Rayada reduced its size to 5,000 soldiers, which was closer to the royalist forces. They took position next to the Maipo River, near Santiago.

Battle of Maipú

San Martín made a brief reconnaissance of the royalist army, and noticed several flaws in their organization. Feeling secure of victory, he claimed that "Osorio is clumsier than I thought. Today's triumph is ours. The sun as witness!". The battle began at 11:00 am. The patriot artillery on the right fired on the royalist infantry on the left. Manuel Escalada led mounted grenadiers to capture the royalist artillery, turning them against their owners. Burgos' regiment severely punished the patriot left wing, mainly composed of emancipated slaves, and took 400 lives. San Martín ordered the mounted grenadiers led by Hilarión de la Quintana to charge against the regiment. The firing suddenly ended and royalists began to fight with sword bayonets, under the cries "Long live the king!" and "Long live the homeland!" respectively. Finally, the royalists ended their cries and began to disperse.

When the regiment of Burgos realized that their line was broken, they stopped resisting, and the soldiers began to disperse. The cavalry pursued and killed most of them. At the end of the battle, the royalists had been trapped among the units of Las Heras in the west, Alvarado in the middle, Quintana in the east and the cavalries of Zapiola and Freire. Osorio tried to fall back to the hacienda "Lo Espejo" but could not reach it, so he tried to escape to Talcahuano. Ordóñez made his last stand at that hacienda, where 500 royalists died.

The battle ended in the afternoon. O'Higgins, still injured by the wound received in Cancha Rayada, arrived during the final action at the hacienda. He claimed "Glory to the savior of Chile!", in reference to San Martín, who praised him for going to the battlefield with his unhealed wound. They made an embrace on their horses, now known as the "Embrace of Maipú".

The battle of Maipú secured Chilean independence. Except for Osorio, who escaped with 200 cavalry, all top royalist military leaders were captured. All their armed forces were either killed or captured, and all their artillery, weapons, military hospitals, money and resources were lost. The victory was praised by Güemes, Bolívar and the international press.

San Martín made a brief reconnaissance of the royalist army, and noticed several flaws in their organization. Feeling secure of victory, he claimed that "Osorio is clumsier than I thought. Today's triumph is ours. The sun as witness!". The battle began at 11:00 am. The patriot artillery on the right fired on the royalist infantry on the left. Manuel Escalada led mounted grenadiers to capture the royalist artillery, turning them against their owners. Burgos' regiment severely punished the patriot left wing, mainly composed of emancipated slaves, and took 400 lives. San Martín ordered the mounted grenadiers led by Hilarión de la Quintana to charge against the regiment. The firing suddenly ended and royalists began to fight with sword bayonets, under the cries "Long live the king!" and "Long live the homeland!" respectively. Finally, the royalists ended their cries and began to disperse.

When the regiment of Burgos realized that their line was broken, they stopped resisting, and the soldiers began to disperse. The cavalry pursued and killed most of them. At the end of the battle, the royalists had been trapped among the units of Las Heras in the west, Alvarado in the middle, Quintana in the east and the cavalries of Zapiola and Freire. Osorio tried to fall back to the hacienda "Lo Espejo" but could not reach it, so he tried to escape to Talcahuano. Ordóñez made his last stand at that hacienda, where 500 royalists died.

The battle ended in the afternoon. O'Higgins, still injured by the wound received in Cancha Rayada, arrived during the final action at the hacienda. He claimed "Glory to the savior of Chile!", in reference to San Martín, who praised him for going to the battlefield with his unhealed wound. They made an embrace on their horses, now known as the "Embrace of Maipú".

The battle of Maipú secured Chilean independence. Except for Osorio, who escaped with 200 cavalry, all top royalist military leaders were captured. All their armed forces were either killed or captured, and all their artillery, weapons, military hospitals, money and resources were lost. The victory was praised by Güemes, Bolívar and the international press.

Fleet of the Pacific

San Martín made a new request for ships to Bowles, but received no answer. He moved again to Buenos Aires, to make a similar request. He arrived to Mendoza a few days after the execution of the Chileans

San Martín made a new request for ships to Bowles, but received no answer. He moved again to Buenos Aires, to make a similar request. He arrived to Mendoza a few days after the execution of the Chileans Luis

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archai ...

and Juan José Carrera, brothers of José Miguel Carrera. The specific initiative of those executions is controversial. Chilean historian Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna indicts San Martín, while J. C. Raffo de la Reta blames O'Higgins instead. Manuel Rodríguez was also imprisoned and then killed in prison; this death may have been decided by the Lautaro lodge. San Martín could not have taken part in it, as he was already on the way to Buenos Aires.

San Martín was not well received in Buenos Aires. Pueyrredón initially declined to give further help, citing the conflicts with the federal caudillos and the organization of a huge royalist army in Cádiz that would try to reconquer the La Plata basin. He thought that Chile should organize the navy against Peru, not Buenos Aires. San Martín discussed with him and finally got financing of 500,000 pesos. He returned to Mendoza with his wife and daughter and received a letter from Pueyrredón, who said that Buenos Aires could only deliver one-third of the promised funds. This complicated the project, as neither Santiago de Chile nor Mendoza had the resources needed. San Martín resigned from the Army, but it is unclear whether his decision to resign was sincere or was to apply pressure to his backers. The government of Buenos Aires still considered San Martín vital to the national defense, so Pueyrredón agreed to pay the 500,000 pesos requested, and encouraged San Martín to withdraw his resignation.

San Martín proposed to mediate between Buenos Aires and the Liga Federal

Liga or LIGA may refer to:

People

* Līga (name), a Latvian female given name

* Luciano Ligabue, more commonly known as Ligabue or ''Liga'', Italian rock singer-songwriter

Sports

* Liga ACB, men's professional basketball league in Spain

* Liga ...

led by Artigas. He thought that the civil war was counter-productive to national unity, and that an end to hostilities would free resources needed for the navy. He calculated that Artigas might condition the peace on a joint declaration of war to colonial Brazil; so San Martín proposed to defeat the royalists first and then demand the return of the Eastern Bank

Eastern Bank is a bank based in Boston, Massachusetts. Before de-mutualizing in 2020, it was the oldest and largest mutual bank in the United States and the largest community bank in Massachusetts. With 95 branches, Eastern had a 3.2% market sh ...

to the United Provinces. O'Higgins recommended caution, fearing that San Martín might be captured. Pueyrredón rejected the mediation, as he did not recognize Artigas as an equal to negotiate with him.

Act of Rancagua

Estanislao López

Estanislao López (26 November 1786 – 15 June 1838) was a ''caudillo'' and governor of the , between 1818 and 1838, one of the foremost proponents of provincial federalism, and an associate of Juan Manuel de Rosas during the Argentine Civ ...

and Francisco Ramírez continued hostilities against Buenos Aires for its inactivity against the invasion. Pueyrredón called the Army of the Andes and the Army of the North

The Army of the North ( es, link=no, Ejército del Norte), contemporaneously called Army of Peru, was one of the armies deployed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in the Spanish American wars of independence. Its objective was fre ...

(led by Belgrano) to aid Buenos Aires in the conflict. Guido noted to San Martín that if both armies did that, the north of Argentina and Chile would be easily reconquered by the royalists. San Martín also knew that most of the soldiers of the Army of the Andes would not be willing to aid Buenos Aires in the civil war, as most were from other provinces or from Chile. San Martín had doubts as well about the projected arrival of a large military expedition from Spain, as the absolutist restoration of Ferdinand VII had met severe resistance in Spain. San Martín finally kept the Army in Chile when Belgrano's lieutenant Viamonte signed an armistice with López; he thought that the conflict had ended.