Joseph Smith presidential campaign, 1844 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The campaign of

The campaign of

Smith's platform was published in the pamphlet "Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States", which his electioneers distributed and presented in public and private meetings, and read to congregations of the church and the general public.

In a change from the strongly anti-

Smith's platform was published in the pamphlet "Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States", which his electioneers distributed and presented in public and private meetings, and read to congregations of the church and the general public.

In a change from the strongly anti-' ''American''' is fraught with ''friendship!''" With regard to territories that opted to remain outside the federal union, Smith opined that "wisdom would direct no tangling alliance". Smith suggested as an alternative accepting into the union

Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States

{{1844 United States presidential election Joseph Smith Smith, Joseph 1844 in Christianity Smith, Joseph 1844 presidential campaign

The campaign of

The campaign of Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

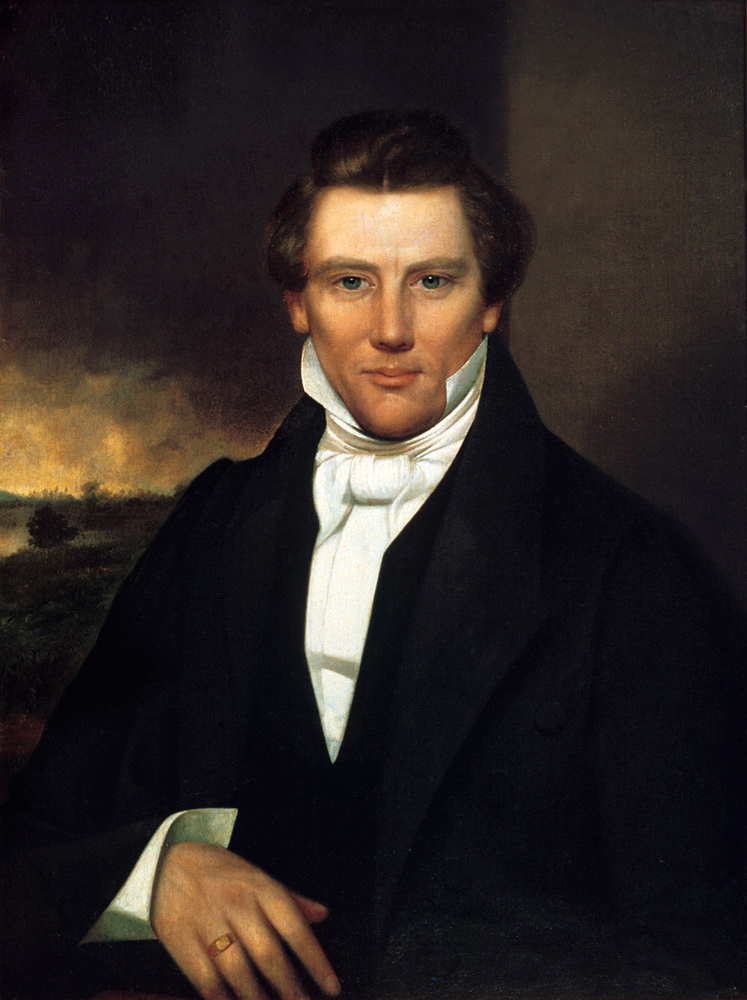

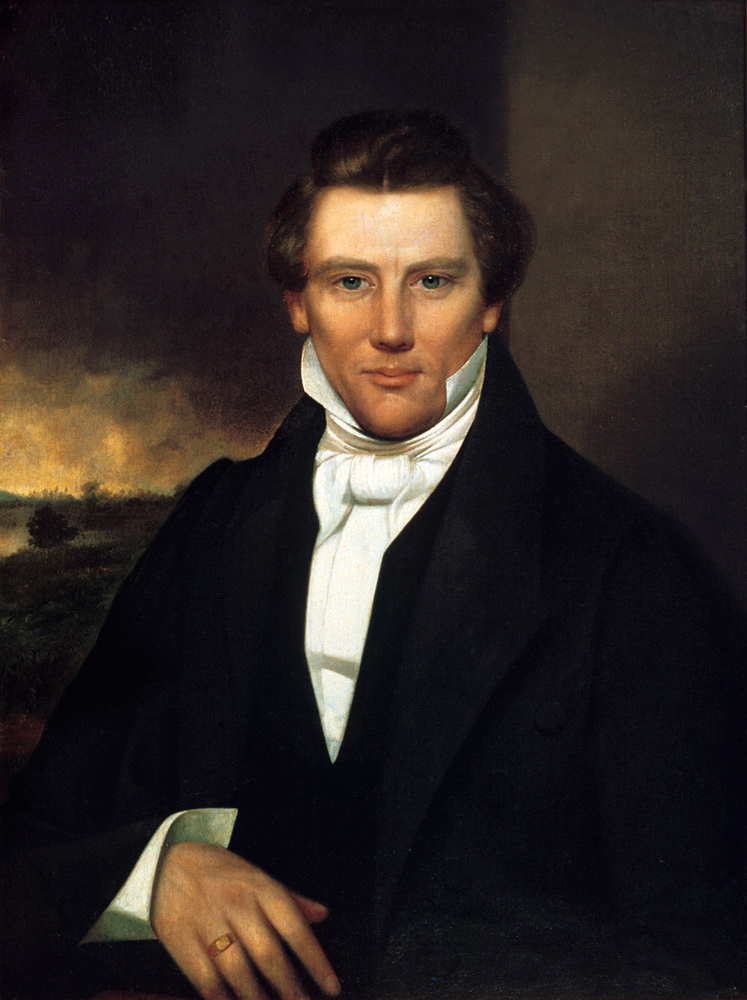

founder Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, h ...

and his vice presidential running mate, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints First Presidency

Among many churches in the Latter Day Saint movement, the First Presidency (also known as the Quorum of the Presidency of the Church) is the highest presiding or governing body. Present-day denominations of the movement led by a First Presidency ...

first counselor Sidney Rigdon

Sidney Rigdon (February 19, 1793 – July 14, 1876) was a leader during the early history of the Latter Day Saint movement.

Biography Early life

Rigdon was born in St. Clair Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, on February 19, 1793. He w ...

, took place in 1844. The United States presidential election

The election of the president and the vice president of the United States is an indirect election in which citizens of the United States who are registered to vote in one of the fifty U.S. states or in Washington, D.C., cast ballots not dir ...

of that year was scheduled for November 1 to December 4, but Smith was killed in Carthage, Illinois

Carthage is a city and the county seat of Hancock County, Illinois, United States. The population was 2,490 as of the 2020 census, Carthage is best known for being the site of the 1844 death of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint mov ...

, on June 27. Smith was the first Latter Day Saint to seek the presidency, and the first American presidential candidate to be assassinated.

In 1844, Smith was the mayor of Nauvoo, Illinois

Nauvoo ( ; from the ) is a small city in Hancock County, Illinois, United States, on the Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa. The population of Nauvoo was 950 at the 2020 census. Nauvoo attracts visitors for its historic importance and it ...

, which was the second most populous city in Illinois with 12,000 residents. Latter Day Saint leaders requested that adherents vote in a bloc behind candidates endorsed by church leaders. As a result, the city's Latter Day Saint residents held the balance of power between the Democrats and Whigs in state elections. Smith also commanded a quasi-public military force, the Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Saint ...

, that with 2,500 men was almost one-third the size of the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

. Wicks and Foister argue in ''Junius and Joseph'' that political operatives with ties to Smith's Whig opponent Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

were present at events surrounding the raid on the jail where Smith was awaiting trial for treason, among other charges.

In his campaign platform, Smith proposed to gradually end slavery, to reduce the size of Congress, to re-establish a national bank, to annex Texas, California, and Oregon, to reform prisons, and to authorize the federal government to protect the liberties of Latter Day Saints and other minorities.

Motivations, prospects, and effects

Motivations that have been cited for Smith's candidacy include wanting to give the Saints a candidate they could support in good conscience; avoiding a political party fiasco between the Whigs and Democrats in Illinois; publicizing the Latter Day Saint cause to help obtain redress for Church members' lost property in Missouri; and bringing the tenets of the church and the political ideas of its prophet to the attention of the nation. Another effect of the campaign was to protect theTwelve Apostles

In Christian theology and ecclesiology, the apostles, particularly the Twelve Apostles (also known as the Twelve Disciples or simply the Twelve), were the primary disciples of Jesus according to the New Testament. During the life and minist ...

, including Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his death in 1877. During his time as chu ...

, from mob violence, since in the faraway places such as Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

where they were traveling, they were out of reach of the Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

mob. John Taylor and Willard Richards

Willard Richards (June 24, 1804 – March 11, 1854) was a physician and midwife/nurse trainer and an early leader in the Latter Day Saint movement. He served as second counselor to church president Brigham Young in the First Presidency of th ...

were the only two apostles left behind in Nauvoo. On the other hand, George R. Gayler notes that the absence of Mormon leaders such as Young, Heber C. Kimball

Heber Chase Kimball (June 14, 1801 – June 22, 1868) was a leader in the early Latter Day Saint movement. He served as one of the original twelve apostles in the early Church of the Latter Day Saints, and as first counselor to Brigham Young ...

, Orson and Parley P. Pratt

Parley Parker Pratt Sr. (April 12, 1807 – May 13, 1857) was an early leader of the Latter Day Saint movement whose writings became a significant early nineteenth-century exposition of the Latter Day Saint faith. Named in 1835 as one of the first ...

, Orson Hyde

Orson Hyde (January 8, 1805 – November 28, 1878) was a leader in the early Latter Day Saint movement and a member of the first Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He was the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus ...

, and John D. Lee, was a great disadvantage to Smith when he was arrested and imprisoned at Carthage, and that these missing apostles were then hurriedly recalled, but arrived at Nauvoo too late. He also notes that Mormon political conventions in Boston and Dresden, Tennessee

Dresden is a town in and the county seat of Weakley County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 3,005 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Dresden is located at (36.283805, -88.698296).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the tow ...

, ended in riots, and that judging "from the troubles in Illinois, Massachusetts and Tennessee due largely to the announcement of his candidacy, the United States may have been saved from the bloodiest election in its history by the death of the Prophet."

Scholars have debated what Smith thought his chances of winning were. At the same time that Smith was running for president, he was also making plans to move the Saints from Nauvoo to Texas or Oregon, for the safety of them and their property. Historian Richard Bushman

Richard Lyman Bushman (June 20, 1931) is an American historian and Gouverneur Morris Professor Emeritus of History at Columbia University, having previously taught at Brigham Young University, Harvard University, Boston University, and the Univ ...

argues that Smith started out as a protest candidate

A protest vote (also called a blank, null, spoiled, or "none of the above" vote) is a vote cast in an election to demonstrate dissatisfaction with the choice of candidates or the current political system. Protest voting takes a variety of forms a ...

but then began to suspect that victory might be attainable. Smith wrote in his journal, "There is oratory enough in the church to carry me into the presidential chair on the first slide" and "When I look into the Eastern papers and see how popular I am, I am afraid I shall be president."

Events

Illinois, where the Latter Day Saint population was in a position to play a pivotal role in presidential politics, had been a battleground state in the1840 United States presidential election

The 1840 United States presidential election was the 14th quadrennial presidential election, held from Friday, October 30 to Wednesday, December 2, 1840. Economic recovery from the Panic of 1837 was incomplete, and Whig nominee William Henry Har ...

, and Latter Day Saints anticipated it might be again in 1844.

In 1843, Smith sent letters to John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

, Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

, Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth vice president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren ...

, Henry Clay, and Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, the five leading contenders for the presidency, inquiring about their plans for ending the persecution that the Mormons were suffering in Missouri. Only Calhoun, Cass, and Clay responded to Joseph Smith's letters, and they did not commit to helping the Latter Day Saints. Smith wrote scathing replies to these letters, denouncing the subterfuges of politicians.

On January 29, 1844, Smith held a meeting in the mayor's office at Nauvoo with the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and others. It was unanimously decided that Smith would run for president on an independent platform. Smith remarked, "I would not have suffered my name to have been used by my friends on any wise as President of the United States, or candidate for that office, if I and my friends could have had the privilege of enjoying our religious and civil rights as American citizens, even those rights which the Constitution guarantees unto all her citizens alike." On March 11, 1844, Smith organized the Council of Fifty

"The Council of Fifty" (also known as "the Living Constitution", "the Kingdom of God", or its name by revelation, "The Kingdom of God and His Laws with the Keys and Power thereof, and Judgment in the Hands of His Servants, Ahman Christ") was a Lat ...

, a deliberative political body to promote Smith's candidacy.

Due to the requirement in the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Twelfth Amendment (Amendment XII) to the United States Constitution provides the procedure for electing the president and vice president. It replaced the procedure provided in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3, by which the Electoral Colleg ...

that each elector cast at least one of his votes (for president and vice president) for a candidate who is not an inhabitant of the same state as himself, Smith wanted to choose a running mate who was not a resident of Illinois. New York educator James Arlington Bennet

James Arlington Bennet (17881863) was an attorney, newspaper publisher, educator and author.

Born in New York, Bennet was the proprietor of Arlington House, a Long Island educational institution. Bennet was appointed inspector-general of the Na ...

was invited to be Smith's running mate, but the invitation was withdrawn due to a misunderstanding regarding Bennet's supposed birth in Ireland, which would have made him ineligible for the presidency under the Constitution's natural-born-citizen clause

A natural-born-citizen clause, if present in the constitution of a country, requires that its president or vice president be a natural born citizen. The constitutions of a number of countries contain such a clause, but there is no universally ac ...

. Colonel Solomon Copeland

Solomon Copeland (1799-184?) was a Tennessee farmer and business investor. He was elected surveyor of Henry County, Tennessee, in 1831 and 1839 and also served as Henry County estate administrator and court commissioner. Henry County voters elect ...

, a state legislator and wealthy and prominent resident of Paris, Tennessee

Paris is a city in and the county seat of Henry County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,316.

A replica of the Eiffel Tower stands in the southern part of Paris.

History

The present site of Pari ...

, was then offered the position, but he declined. Rigdon, a Pennsylvanian, then became Smith's running mate.

At the April 9, 1844 church general conference, a call was made for volunteers to electioneer for Joseph Smith to be the next president. Hundreds of elders volunteered, and the Quorum of the Twelve scheduled public political conferences in each state. Electioneers included Wilford Woodruff

Wilford Woodruff Sr. (March 1, 1807September 2, 1898) was an American religious leader who served as the fourth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1889 until his death. He ended the public practice of ...

, Franklin D. Richards, Heber C. Kimball

Heber Chase Kimball (June 14, 1801 – June 22, 1868) was a leader in the early Latter Day Saint movement. He served as one of the original twelve apostles in the early Church of the Latter Day Saints, and as first counselor to Brigham Young ...

, Moses Tracy

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

and his wife Nancy, John D. Lee, Ezra T. Benson

Ezra Taft Benson (February 22, 1811 – September 3, 1869) (commonly referred to as Ezra T. Benson to distinguish him from his great-grandson of the same name) was an apostle and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church o ...

, Norton Jacob Norton may refer to:

Places

Norton, meaning 'north settlement' in Old English, is a common place name. Places named Norton include: Canada

* Rural Municipality of Norton No. 69, Saskatchewan

*Norton Parish, New Brunswick

**Norton, New Brunswick, a ...

, James Burgess, Edson Barney Edson may refer to:

Places Canada

* Edson, Alberta

United States

* Edson, Kansas, an unincorporated community

* Edson, South Dakota, a ghost town

* Edson, Wisconsin, a town

** Edson (community), Wisconsin, an unincorporated community

People ...

, George Miller, Joseph Holbrook

Joseph Holbrook (January 16, 1806 – November 14, 1885) was a Mormon pioneer in the U.S. territory of Utah. He was also a county judge and member of the Utah Territorial Legislature.

Holbrook was born in what was then Florence, New York. Wh ...

, and David Pettegrew

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, among others. Smith enlisted the entire manpower of the church in the campaign. Smith presidential electors were appointed and D. S. Hollister D. or d. may refer to, usually as an abbreviation:

* Don (honorific), a form of address in Spain, Portugal, Italy, and their former overseas empires, usually given to nobles or other individuals of high social rank.

* Date of death, as an abbrevia ...

was sent to Baltimore to observe and possibly lobby for the Smith candidacy at the Whig and Democratic national convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

s.

The Latter Day Saints formed a new political party, the Reform Party, that held a nomination convention on 17 May which was attended by delegates from all 26 states and ten Illinois counties. The nomination of Smith and Rigdon was uncontested, and a platform was adopted stating that the party would support Smith for the presidency, "the better to carry out the principles of liberty and equal rights, Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, whic ...

, free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

, and sailors' rights, and the protection of person and property." Arrangements were entered into to hold a national convention in New York on 13 July.

Many of the electioneers used the campaign as a proselytizing opportunity as well as a political mission, and therefore continued on their mission of preaching, baptizing, visiting church branches, and curbing apostasies after Smith's death ended the campaign. They began referring to Smith as a martyr.

Platform

Smith's platform was published in the pamphlet "Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States", which his electioneers distributed and presented in public and private meetings, and read to congregations of the church and the general public.

In a change from the strongly anti-

Smith's platform was published in the pamphlet "Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States", which his electioneers distributed and presented in public and private meetings, and read to congregations of the church and the general public.

In a change from the strongly anti-abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

stance that he had previously adopted, Smith proposed the abolition of slavery by the year 1850 through compensated emancipation

Compensated emancipation was a method of ending slavery, under which the enslaved person's owner received compensation from the government in exchange for manumitting the slave. This could be monetary, and it could allow the owner to retain the s ...

funded with revenue from the sale of public lands, and with the savings from cutting the salaries of members of the United States Congress from $8/day to $2/day. Smith explained, "The Southern people are hospitable and noble. They will help to rid so free a country of every vestige of slavery, whenever they are assured of an equivalent for their property." Smith's compensated emancipation proposal was reportedly well received in Kentucky.

Although Smith warned, "Speculators will urge a national bank as a savior of credit and comfort," he also put forward his own proposal for a national bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

, which would operate on a principle of full-reserve banking

Full-reserve banking (also known as 100% reserve banking, narrow banking, or sovereign money system) is a system of banking where banks do not lend demand deposits and instead, only lend from time deposits. It differs from fractional-reserve bank ...

. The mother bank's capital stock

A corporation's share capital, commonly referred to as capital stock in the United States, is the portion of a corporation's equity that has been derived by the issue of shares in the corporation to a shareholder, usually for cash. "Share capi ...

would be owned by the federal government, and the bank's branches would be owned by their respective states. The officers and directors would be elected annually by the people. Smith proposed the adoption of a "judicious tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

" to protect agriculture, manufactures, navigation, and commerce.

Smith also called for a reduction in the size of the United States House of Representatives to two members per million of population, believing that a smaller body would "do more business than the army that now occupy the halls of the national legislature." More generally, he warned, "No honest man can doubt for a moment but the glory of American liberty is on the wane" and exhorted the people, "Curtail the officers of government in pay, number, and power". He argued, "More economy in the national and state governments would make less taxes among the people". Praising the vision of the "respected and venerable Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

", he remarked, "what a beautiful prospect an innocent, virtuous nation presents to the sage's eye where there is space for enterprise, hands for industry, heads for heroes, and hearts for moral greatness."

Smith advocated reforming the penal system by mostly abolishing prisons, including debtor's prisons

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Historic ...

, and using the buildings for "seminaries of learning" so that intelligence would banish barbarism. Smith suggested reforming criminals through "reason and friendship" and wrote, "Petition your State legislatures to pardon every convict in their several penitentiaries, blessing them as they go, and saying to them, in the name of the Lord, '' Go thy way, and sin no more''. Advise your legislators, when they make laws for larceny, burglary, or any felony, to make the penalty applicable to work upon roads, public works, or any place where the culprit can be taught more wisdom and more virtue, and become more enlightened." Smith advocated elimination of courts martial, proposing that deserters instead be given their pay and dishonorably discharged

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

, never again to merit the nation's trust.

Smith called for a day when "the neighbor from any State or from any country, of whatever color, clime, or tongue, could rejoice when he put his foot on the sacred soil of freedom, and exclaim, The very name of Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, as well as other countries, with the consent of the peoples concerned, including any Indians inhabiting the land. He remarked:

Smith advocated granting of power to the president to suppress mobs without waiting for a request from state governors (as required by Article Four of the Constitution), on the principle that "The governor himself may be a mobber; and instead of being punished, as he should be, for murder or treason, he may destroy the very lives, rights, and property he should protect." Smith favored a constitutional amendment providing for capital punishment of public officials who refused to assist those denied their constitutional rights. He wrote, "The state rights doctrines are what feed mobs."

Further reading

*McBride, Spencer W. (2020). "'Many Think This Is a Hoax': The Newspaper Response to Joseph Smith's 1844 Presidential Campaign", in Spencer W. McBride, Brent M. Rogers, and Keith A. Erekson, ''Contingent Citizens: Shifting Perceptions of Latter-day Saints in American Political Culture''. Cornell University Press . *References

External links

Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States

{{1844 United States presidential election Joseph Smith Smith, Joseph 1844 in Christianity Smith, Joseph 1844 presidential campaign