Joseph Johnson (publisher) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Johnson (15 November 1738 – 20 December 1809) was an influential 18th-century

The second and possibly more consequential friendship was with

The second and possibly more consequential friendship was with

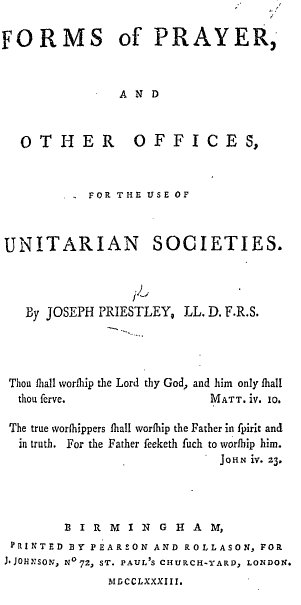

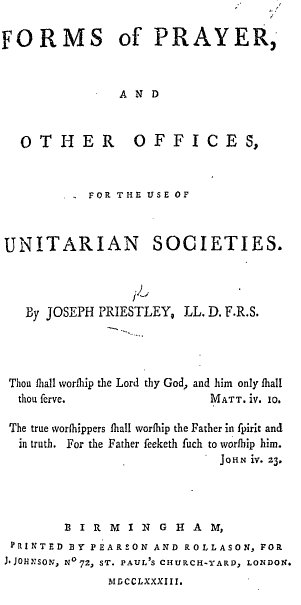

Immediately upon reopening his business, Johnson started publishing theological and political works by Priestley and other

Immediately upon reopening his business, Johnson started publishing theological and political works by Priestley and other

After 1770, Johnson began to publish a wider array of books, particularly scientific and medical texts. One of the most important was John Hunter's ''A Natural History of the Human Teeth, Part I'' (1771), which "elevated dentistry to the level of surgery". Johnson also supported doctors when they questioned the efficacy of cures, such as with John Millar in his ''Observations on Antimony'' (1774), which claimed that Dr James's Fever Powder was ineffective. This was a risky publication for Johnson, because this

After 1770, Johnson began to publish a wider array of books, particularly scientific and medical texts. One of the most important was John Hunter's ''A Natural History of the Human Teeth, Part I'' (1771), which "elevated dentistry to the level of surgery". Johnson also supported doctors when they questioned the efficacy of cures, such as with John Millar in his ''Observations on Antimony'' (1774), which claimed that Dr James's Fever Powder was ineffective. This was a risky publication for Johnson, because this

L'Ami des Enfans

' (1782–83).Tyson, 81–84. In addition to books for children, Johnson published schoolbooks and textbooks for autodidacts, such as John Hewlett's ''Introduction to Spelling and Reading'' (1786), William Nicholson's ''Introduction to Natural Philosophy'' (1782), and his friend John Bonnycastle's ''An Introduction to Mensuration and Practical Mathematics'' (1782). Johnson also published books on education and childrearing, such as Wollstonecraft's first book, ''

During the 1780s, Johnson achieved success: he did well financially and his firm published more books with other firms. Although Johnson had begun his career as a relatively cautious publisher of religious and scientific tracts, he was now able to take more risks and he encouraged friends to recommend works to him, creating a network of informal reviewers. Yet Johnson's business was never large; he usually had only one assistant and never took on an apprentice. Only in the last years of his life did two relatives assist him.

During the 1780s, Johnson achieved success: he did well financially and his firm published more books with other firms. Although Johnson had begun his career as a relatively cautious publisher of religious and scientific tracts, he was now able to take more risks and he encouraged friends to recommend works to him, creating a network of informal reviewers. Yet Johnson's business was never large; he usually had only one assistant and never took on an apprentice. Only in the last years of his life did two relatives assist him.

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

bookseller

Bookselling is the commercial trading of books which is the retail and distribution end of the publishing process. People who engage in bookselling are called booksellers, bookdealers, bookpeople, bookmen, or bookwomen. The founding of libra ...

and publisher

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed works, such as books, newsp ...

. His publications covered a wide variety of genres and a broad spectrum of opinions on important issues. Johnson is best known for publishing the works of radical thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

, William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

, Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

and Joel Barlow, feminist economist Priscilla Wakefield

Priscilla Wakefield, ''nee'' Priscilla Bell (31 January 1751 – 12 September 1832) was an English Quaker philanthropist. Her writings cover feminist economics and scientific subjects and include children's non-fiction.Ann B. Shteir, "Wakefield ...

, as well as religious Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

such as Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

, Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld (, by herself possibly , as in French, Aikin; 20 June 1743 – 9 March 1825) was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and author of children's literature. A " woman of letters" who published in mu ...

, Gilbert Wakefield, and George Walker.

In the 1760s, Johnson established his publishing business, which focused primarily on religious works. He also became friends with Priestley and the artist Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli ( ; German: Johann Heinrich Füssli ; 7 February 1741 – 17 April 1825) was a Swiss painter, draughtsman and writer on art who spent much of his life in Britain. Many of his works, such as ''The Nightmare'', deal with supernatur ...

– two relationships that lasted his entire life and brought him much business. In the 1770s and 1780s, Johnson expanded his business, publishing important works in medicine and children's literature as well as the popular poetry of William Cowper

William Cowper ( ; 26 November 1731 – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and sce ...

and Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

. Throughout his career, Johnson helped shape the thought of his era not only through his publications, but also through his support of innovative writers and thinkers. He fostered the open discussion of new ideas, particularly at his famous weekly dinners, the regular attendees of which became known as the "Johnson Circle".

In the 1790s, Johnson aligned himself with the supporters of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, and published an increasing number of political pamphlets in addition to a prominent journal, the ''Analytical Review

The ''Analytical Review'' was an English periodical that was published from 1788 to 1798, having been established in London by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publica ...

'', which offered British reformers a voice in the public sphere. In 1799, he was indicted on charges of seditious libel

Sedition and seditious libel were criminal offences under English common law, and are still criminal offences in Canada. Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection ...

for publishing a pamphlet by the Unitarian minister Gilbert Wakefield. After spending six months in prison, albeit under relatively comfortable conditions, Johnson published fewer political works. In the last decade of his career, Johnson did not seek out many new writers; however, he remained successful by publishing the collected works of authors such as William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

.

Johnson's friend John Aikin

John Aikin (15 January 1747 – 7 December 1822) was an English medical doctor and surgeon. Later in life he devoted himself wholly to biography and writing in periodicals.

Life

He was born at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, England, son of ...

eulogized him as "the father of the booktrade".Hall (2004). "Joseph Johnson". ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

''. Retrieved on 30 April 2007. He has also been called "the most important publisher in England from 1770 until 1810" for his appreciation and promotion of young writers, his emphasis on publishing inexpensive works directed at a growing middle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

readership, and his cultivation and advocacy of women writers at a time when they were viewed with skepticism.

Early life

Johnson was the second son of John Johnson, aBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

who lived in Everton, Liverpool

Everton is a district in Liverpool, in Merseyside, England, in the Liverpool City Council ward of Everton. It is part of the Liverpool Walton Parliamentary constituency. Historically in Lancashire, at the 2001 Census the population was reco ...

, and his wife Rebecca Turner. Religious Dissent marked Johnson from the beginning of his life, as two of his mother's relatives were prominent Baptist ministers and his father was a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

. Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, at the time of Johnson's youth, was fast becoming a bustling urban centre and was one of the most important commercial ports in England. These two characteristics of his home – Dissent and commercialism – remained central elements in Johnson's character throughout his life.Tyson, 1–7; Chard (1975), 52–55; Zall, 25; Braithwaite, 1–2.

At the age of fifteen, Johnson was apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

d to George Keith, a London bookseller who specialized in publishing religious tracts such as '' Reflections on the Modern but Unchristian Practice of Innoculation''. As Gerald Tyson, Johnson's major modern biographer, explains, it was unusual for the younger son of a family living in relative obscurity to move to London and to become a bookseller. Scholars have speculated that Johnson was indentured to Keith because the bookseller was associated with Liverpool Baptists. Keith and Johnson published several works together later in their careers, which suggests that the two remained on friendly terms after Johnson started his own business.

1760s: Beginnings in publishing

Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1761, Johnson opened his own business, but he struggled to establish himself, moving his shop several times within one year. Two of his early publications were a kind of day planner: ''The Complete Pocket-Book; Or, Gentleman and Tradesman's Daily Journal for the Year of Our Lord, 1763'' and ''The Ladies New and Polite Pocket Memorandum Book''. Such pocketbooks were popular and Johnson outsold his rivals by publishing his both earlier and cheaper. Johnson continued to sell these profitable books until the end of the 1790s, but as a religiousDissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, ...

, he was primarily interested in publishing books that would improve society. Therefore, religious texts dominated his book list, although he also published works relating to Liverpool (his home town) and medicine. However, as a publisher Johnson attended to more than the selling and distributing of books, as scholar Leslie Chard explains:

As Johnson became successful and his reputation grew, other publishers began including him in congers – syndicates that spread the risk of publishing a costly or inflammatory book among several firms.

Formative friendships

In his late twenties, Johnson formed two friendships that were to shape the rest of his life. The first was with the painter and writerHenry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli ( ; German: Johann Heinrich Füssli ; 7 February 1741 – 17 April 1825) was a Swiss painter, draughtsman and writer on art who spent much of his life in Britain. Many of his works, such as ''The Nightmare'', deal with supernatur ...

, who was described as "quick witted and pugnacious". Fuseli's early 19th-century biographer writes that when Fuseli met Johnson in 1764, Johnson "had already acquired the character which he retained during life, – that of a man of great integrity, and encourager of literary men as far as his means extended, and an excellent judge of their productions". Fuseli became and remained Johnson's closest friend.

The second and possibly more consequential friendship was with

The second and possibly more consequential friendship was with Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

, the renowned natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

and Unitarian theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

. This friendship led Johnson to discard the Baptist faith of his youth and to adopt Unitarianism, as well as to pursue forms of political dissent.Tomalin, 15–16. Johnson's success as a publisher can be explained in large part through his association with Priestley, as Priestley published dozens of books with him and introduced him to many other Dissenting writers. Through Priestley's recommendation, Johnson was able to issue the works of many Dissenters, especially those from Warrington Academy: the poet, essayist, and children's author Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld (, by herself possibly , as in French, Aikin; 20 June 1743 – 9 March 1825) was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and author of children's literature. A " woman of letters" who published in mu ...

; her brother, the physician and writer, John Aikin

John Aikin (15 January 1747 – 7 December 1822) was an English medical doctor and surgeon. Later in life he devoted himself wholly to biography and writing in periodicals.

Life

He was born at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, England, son of ...

; the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster (22 October 1729 – 9 December 1798) was a German Reformed (Calvinist) pastor and naturalist of partially Scottish descent who made contributions to the early ornithology of Europe and North America. He is best known ...

; the Unitarian minister and controversialist

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

Gilbert Wakefield; the moralist William Enfield

William Enfield (29 March 1741 – 3 November 1797) was a British Unitarian minister who published a bestselling book on elocution entitled ''The Speaker'' (1774).

Life

Enfield was born in Sudbury, Suffolk to William and Ann Enfield. In 1758, ...

; and the political economist Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

. Tyson writes that "the relationship between the Academy and the bookseller was mutually very useful. Not only did many of the tutors send occasional manuscripts for publication, but also former pupils often sought him out in later years to issue their works." By printing the works of Priestley and other of the Warrington tutors, Johnson also made himself known to an even larger network of Dissenting intellectuals, including those in the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

, which expanded his business further. Priestley, in turn, trusted Johnson enough to handle the logistics of his induction into the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

Partnerships

In July 1765, Johnson moved his business to the more visible 8Paternoster Row

Paternoster Row was a street in the City of London that was a centre of the London publishing trade, with booksellers operating from the street. Paternoster Row was described as "almost synonymous" with the book trade. It was part of an area ca ...

and formed a partnership with B. Davenport, of whom little is known aside from his association with Johnson. Chard postulates that they were attracted by mutual beliefs because the firm of Johnson and Davenport published even more religious works, including many that were "rigidly Calvinistic". However, in the summer of 1767, Davenport and Johnson parted ways; scholars have speculated that this rupture occurred because Johnson's religious views were becoming more unorthodox.

Newly independent, with a solid reputation, Johnson did not need to struggle to establish himself as he had early in his career. Within a year, he published nine first editions himself as well as thirty-two works in partnership with other booksellers. He was also a part of "the select circle of bookmen that gathered at the Chapter Coffee House

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-caf ...

", which was the centre of social and commercial life for publishers and booksellers in 18th-century London. Major publishing ventures had started at the Chapter and important writers "clubbed

''Clubbed'' is a 2008 British drama film about a 1980s factory worker who takes up a job as a club doorman, written by Geoff Thompson and directed by Neil Thompson.

Plot

In 1984, Danny - a lonely factory worker intimidated by life - is batter ...

" there.

In 1768 Johnson went into partnership with John Payne (Johnson was probably the senior partner); the following year they published 50 titles. Under Johnson and Payne, the firm published a wider array of works than under Johnson and Davenport. Although Johnson looked to his business interests, he did not publish works only to enrich himself. Projects that encouraged free discussion appealed to Johnson; for example, he helped Priestley publish the ''Theological Repository

The ''Theological Repository'' was a periodical founded and edited from 1769 to 1771 by the eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley. Although ostensibly committed to the open and rational inquiry of theological questions, the journ ...

'', a financial failure that nevertheless fostered open debate of theological questions. Although the journal lost Johnson money in the 1770s, he was willing to begin publishing it again in 1785 because he endorsed its values.

The late 1760s was a time of growing radicalism in Britain, and although Johnson did not participate actively in the events, he facilitated the speech of those who did, e.g., by publishing works on the disputed election of John Wilkes and the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. Despite his growing interest in politics, Johnson (with Payne) still published primarily religious works and the occasional travel narrative

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern pe ...

. As Tyson writes, "in the first decade of his career Johnson's significance as a bookseller derived from a desire to provide dissent (religious and political) a forum".

Fire

Johnson was on the verge of real success when his shop was ravaged by fire on 9 January 1770. As one London newspaper reported it: At the time Fuseli had been living with Johnson and he also lost all of his possessions, including the first printing of his ''Remarks on the Writings and Conduct of J. J. Rousseau''. Johnson and Payne subsequently dissolved their partnership. It was an amicable separation, and Johnson even published some of Payne's works in later years.1770s: Establishment

By August 1770, just seven months after fire had destroyed his shop and goods, Johnson had re-established himself at 72 St. Paul's Churchyard – the largest shop on a street of booksellers – where he was to remain for the rest of his life. How Johnson managed this feat is unclear; he later cryptically told a friend that "his friends came about him, and set him up again". An early 19th-century biography states that "Mr. Johnson was now so well known, and had been so highly respected, that on this unfortunate occasion, his friends with one accord met, and contributed to enable him to begin business again". Chard speculates that Priestley assisted him since they were such close friends.Chard (1975), 59.Religious publications and advocacy of Unitarianism

Immediately upon reopening his business, Johnson started publishing theological and political works by Priestley and other

Immediately upon reopening his business, Johnson started publishing theological and political works by Priestley and other Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

. Starting in the 1770s, Johnson published more specifically Unitarian works, as well as texts advocating religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

; he also became personally involved in the Unitarian cause. He served as a conduit for information between Dissenters across the country and supplied provincial publishers with religious publications, thereby enabling Dissenters to spread their beliefs easily. Johnson participated in efforts to repeal the Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

and Corporation Acts, which restricted the civil rights of Dissenters. In one six-year period of the 1770s, Johnson was responsible for publishing nearly one-third of the Unitarian works on the issue. He continued his support in 1787, 1789, and 1790, when Dissenters introduced repeal bills in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, and he published much of the pro-repeal literature written by Priestley and others.Chard (2002), 95–101.

Johnson was also instrumental in Theophilus Lindsey's founding of the first Unitarian chapel in London. With some difficulty, as Unitarians were feared at that time and their beliefs held illegal until the Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813

The Act 53 Geo 3 c 160, sometimes called the Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813, the Trinitarian Act 1812, the Unitarian Relief Act, the Trinity Act, the Unitarian Toleration Bill, or Mr William Smith's Bill (after Whig politician William Smith), ...

, Johnson obtained the building for Essex Street Chapel and, with the help of barrister John Lee, who later became Attorney-General, its licence. To capitalize on the opening of the new chapel in addition to helping out his friends, Johnson published Lindsey's inaugural sermon, which sold out in four days. Johnson continued to attend and participate actively in this congregation throughout his life. Lindsey and the church's other minister, John Disney, became two of Johnson's most active writers. In the 1780s, Johnson continued to advocate Unitarianism and published a series of controversial writings by Priestley arguing for its legitimacy. These writings did not make Johnson much money, but they agreed with his philosophy of open debate and religious toleration. Johnson also became the publisher for the Society for Promoting the Knowledge of the Scriptures, a Unitarian group determined to release new worship materials and commentaries on the Bible.Chard (2002), 95–101. (See British and Foreign Unitarian Association#Publishing.)

Although Johnson is known for publishing Unitarian works, particularly those of Priestley, he also published the works of other Dissenters, Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

s, and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s. The common thread uniting his disparate religious publications was religious toleration. For example, he published the Reverend George Gregory's 1787 English translation of Bishop Robert Lowth's seminal book on Hebrew poetry Hebrew poetry is poetry written in the Hebrew language. It encompasses such things as:

* Biblical poetry, the poetry found in the poetic books of the Hebrew Bible

* Piyyut, religious Jewish liturgical poetry in Hebrew or Aramaic

* Medieval Hebre ...

, ''De Sacra Poesi Hebraeorum''. Gregory published several other works with Johnson, such as ''Essays Historical and Moral'' (1785) and ''Sermons with Thoughts on the Composition and Delivery of a Sermon'' (1787). Gregory exemplified the type of author that Johnson preferred to work with: industrious and liberal-minded, but not bent on self-glorification. Yet, as Helen Braithwaite writes in her study of Johnson, his "enlightened pluralistic approach was also seen by its opponents as inherently permissive, opening the door to all forms of unhealthy questioning and scepticism, and at odds with the stable virtues of established religion and authority".

American Revolution

Partially as a result of his association with British Dissenters, Johnson became involved in publishing tracts and sermons in defence of theAmerican revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

aries. He began with Priestley's ''Address to Protestant Dissenters of All Denominations, on the Approaching Election of Members of Parliament'' (1774), which urged Dissenters to vote for candidates that guaranteed the American colonists their freedom. Johnson continued his series of anti-government, pro-American pamphlets by publishing Fast Day sermons by Joshua Toulmin

Joshua Toulmin ( – 23 July 1815) of Taunton, England was a noted theologian and a serial Dissenting minister of Presbyterian (1761–1764), Baptist (1765–1803), and then Unitarian (1804–1815) congregations. Toulmin's sympathy for b ...

, George Walker, Ebenezer Radcliff, and Newcome Cappe. Braithwaite describes these as "well-articulated critiques of government" that "were not only unusual but potentially subversive and disruptive", and she concludes that Johnson's decision to publish so much of this material indicates that he supported the political position it espoused.Braithwaite, 47–48. Moreover, Johnson published what Braithwaite calls "probably the most influential English defence of the colonists", Richard Price's '' Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty'' (1776). Over 60,000 copies were sold in a year. In 1780 Johnson also issued the first collected political works of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

in England, a political risk as the American colonies were in rebellion by that time. Johnson did not usually reprint colonial texts – his ties to the revolution were primarily through Dissenters. Thus, the works published by Johnson emphasized both colonial independence and the rights for which Dissenters were fighting – "the right to petition for redress of grievance, the maintenance and protection of equal civil rights, and the inalienable right to liberty of conscience".

Informative texts

After 1770, Johnson began to publish a wider array of books, particularly scientific and medical texts. One of the most important was John Hunter's ''A Natural History of the Human Teeth, Part I'' (1771), which "elevated dentistry to the level of surgery". Johnson also supported doctors when they questioned the efficacy of cures, such as with John Millar in his ''Observations on Antimony'' (1774), which claimed that Dr James's Fever Powder was ineffective. This was a risky publication for Johnson, because this

After 1770, Johnson began to publish a wider array of books, particularly scientific and medical texts. One of the most important was John Hunter's ''A Natural History of the Human Teeth, Part I'' (1771), which "elevated dentistry to the level of surgery". Johnson also supported doctors when they questioned the efficacy of cures, such as with John Millar in his ''Observations on Antimony'' (1774), which claimed that Dr James's Fever Powder was ineffective. This was a risky publication for Johnson, because this patent medicine

A patent medicine, sometimes called a proprietary medicine, is an over-the-counter (nonprescription) medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name (and sometimes a patent) and claimed ...

was quite popular and his fellow bookseller John Newbery had made his fortune from selling it.

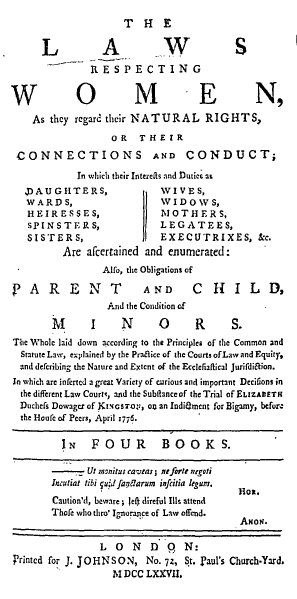

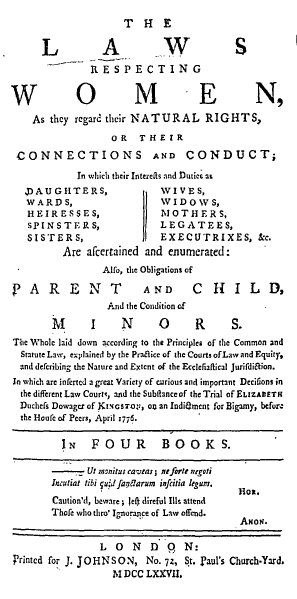

In 1777 Johnson published the remarkable ''Laws Respecting Women, as they Regard Their Natural Rights'', which is an explication, for the layperson, of exactly what its title suggests. As Tyson comments, "the ultimate value of this book lies in its arming women with the knowledge of their legal rights in situations where they had traditionally been vulnerable because of ignorance". Johnson published ''Laws Respecting Women'' anonymously, but it is sometimes credited to Elizabeth Chudleigh Bristol, known for her bigamous marriage to the 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull after having previously privately married Augustus John Hervey, afterwards 3rd Earl of Bristol. This publication foreshadowed Johnson's efforts to promote works about women's issues – such as ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

'' (1792) – and his support of women writers.

Revolution in children's literature

Johnson also contributed significantly tochildren's literature

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

. His publication of Barbauld's ''Lessons for Children

''Lessons for Children'' is a series of four age-adapted reading primers written by the prominent 18th-century British poet and essayist Anna Laetitia Barbauld. Published in 1778 and 1779, the books initiated a revolution in children's literat ...

'' (1778–79) spawned a revolution in the newly emerging genre. Its plain style, mother-child dialogues, and conversational tone inspired a generation of authors, such as Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer (''née'' Kirby; 6 January 1741 – 15 December 1810) was a writer and critic of 18th-century British children's literature, as well as an educational reformer. Her periodical, ''The Guardian of Education'', helped to define the e ...

.Mandell, 108–13. Johnson encouraged other women to write in this genre, such as Charlotte Smith, but his recommendation always came with a caveat of how difficult it was to write well for children. For example, he wrote to Smith, "perhaps you cannot employ your time and extraordinary talents more usefully for the public & your self , than in composing books for children and young people, but I am very sensible it is extreamly difficult to acquire that simplicity of style which is their great recommendation". He also advised William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

and his second wife, Mary Jane Clairmont, on the publication of their Juvenile Library (started in 1805). Not only did Johnson encourage the writing of British children's literature, but he also helped sponsor the translation and publication of popular French works such as Arnaud Berquin's L'Ami des Enfans

' (1782–83).Tyson, 81–84. In addition to books for children, Johnson published schoolbooks and textbooks for autodidacts, such as John Hewlett's ''Introduction to Spelling and Reading'' (1786), William Nicholson's ''Introduction to Natural Philosophy'' (1782), and his friend John Bonnycastle's ''An Introduction to Mensuration and Practical Mathematics'' (1782). Johnson also published books on education and childrearing, such as Wollstonecraft's first book, ''

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

''Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life'' is the first published work of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Published in 1787 by her friend Joseph Johnson, ''Tho ...

'' (1787).

By the end of the 1770s, Johnson had become an established publisher. Writers – particularly Dissenters – sought him out, and his home started to become the centre of a radical and stimulating intellectual milieu. Because he was willing to publish multiple opinions on issues, he was respected as a publisher by writers from across the political spectrum. Johnson published many Unitarian works, but he also issued works criticizing them; although he was an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, he also published works arguing in favour of the slave trade; he supported inoculation, but he also published works critical of the practice.Chard (1977), 140.

1780s: Success

During the 1780s, Johnson achieved success: he did well financially and his firm published more books with other firms. Although Johnson had begun his career as a relatively cautious publisher of religious and scientific tracts, he was now able to take more risks and he encouraged friends to recommend works to him, creating a network of informal reviewers. Yet Johnson's business was never large; he usually had only one assistant and never took on an apprentice. Only in the last years of his life did two relatives assist him.

During the 1780s, Johnson achieved success: he did well financially and his firm published more books with other firms. Although Johnson had begun his career as a relatively cautious publisher of religious and scientific tracts, he was now able to take more risks and he encouraged friends to recommend works to him, creating a network of informal reviewers. Yet Johnson's business was never large; he usually had only one assistant and never took on an apprentice. Only in the last years of his life did two relatives assist him.

Literature

Once Johnson's financial situation had become secure, he began to publish literary authors, most famously the poetWilliam Cowper

William Cowper ( ; 26 November 1731 – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and sce ...

. Johnson issued Cowper's ''Poems'' (1782) and '' The Task'' (1784) at his own expense (a generous action at a time when authors were often forced to take on the risk of publication), and was rewarded with handsome sales of both volumes. Johnson published many of Cowper's works, including the anonymous satire ''Anti-thelyphora'' (1780), which mocked the work of Cowper's own cousin, the Rev. Martin Madan, who had advocated polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marr ...

as a solution for prostitution. Johnson even edited and critiqued Cowper's poetry in manuscript, "much to the advantage of the poems" according to Cowper. In 1791, Johnson published Cowper's translations of the Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

ic epics (extensively edited and corrected by Fuseli) and three years after Cowper's death in 1800, Johnson published a biography of the poet by William Hayley

William Hayley (9 November 174512 November 1820) was an English writer, best known as the biographer of his friend William Cowper.

Biography

Born at Chichester, he was sent to Eton in 1757, and to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, in 1762; his conne ...

.

Johnson never published much "creative literature"; Chard attributes this to "a lingering Calvinistic hostility to 'imaginative' literature".Chard (1975), 61. Most of the literary works Johnson published were religious or didactic

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need t ...

. Some of his most popular productions in this vein were anthologies; the most famous is probably William Enfield's ''The Speaker'' (1774), which went through multiple editions and spawned many imitations, such as Wollstonecraft's ''The Female Speaker''.

Medical and scientific publications

Johnson continued his interest in publishing practical medical texts in the 1780s and 1790s; during the 1780s, he brought out some of his most significant works in this area. According to Johnson's friend, the physicianJohn Aikin

John Aikin (15 January 1747 – 7 December 1822) was an English medical doctor and surgeon. Later in life he devoted himself wholly to biography and writing in periodicals.

Life

He was born at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, England, son of ...

, he intentionally established one of his first shops on "the track of the Medical Students resorting to the Hospitals in the Borough", where they would be sure to see his wares, which helped to establish him in medical publishing. Johnson published the works of the scientist-Dissenters he met through Priestley and Barbauld, such as Thomas Beddoes and Thomas Young. He issued the children's book on birds produced by the industrialist Samuel Galton and the Lunar Society's translation of Linnaeus's ''System of Vegetables'' (1783). He also published works by James Edward Smith, "the botanist who brought the Linnaean system

Linnaean taxonomy can mean either of two related concepts:

# The particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his ''Systema Naturae'' (1735) and subsequent works. In the taxonomy of Linnaeus t ...

to England".

In 1784, Johnson issued John Haygarth's ''An Inquiry How to Prevent Small-Pox'', which furthered the understanding and treatment of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. Johnson published several subsequent works by Haygarth that promoted inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microorganism. It may refer to methods of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases, or it may be used to describe the spreading of disease, as in "self-inoculati ...

(and later vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulat ...

) for the healthy, as well as quarantining for the sick. He also published the work of James Earle

Sir James Earle (1755–1817) was a celebrated British surgeon, renowned for his skill in lithotomy.

Earle was born in London. After studying medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital, he became the institution's assistant surgeon in 1770. Due to ...

, a prominent surgeon, whose significant book on lithotomy

Lithotomy from Greek for "lithos" (stone) and "tomos" ( cut), is a surgical method for removal of calculi, stones formed inside certain organs, such as the urinary tract (kidney stones), bladder ( bladder stones), and gallbladder (gallstones), ...

was illustrated by William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of t ...

, and Matthew Baillie's ''Morbid Anatomy'' (1793), "the first text of pathology devoted to that science exclusively by systematic arrangement and design".

Not only did Johnson publish the majority of Priestley's theological works, but he also published his scientific works, such as ''Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

''Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air'' (1774–86) is a six-volume work published by 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley which reports a series of his experiments on "airs" or gases, most notably his discovery of ...

'' (1774–77) in which Priestley announced his discovery of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

. Johnson also published the works of Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hydr ...

and Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

new chemistry" that he had developed (which included today's modern notions of element and compound), Johnson had these translated and printed immediately, despite his association with Priestley who argued strenuously against Lavoisier's new system. Johnson was the first to publish an English edition of Lavoisier's early writings on chemistry and he kept up with the ongoing debate. These works did well for Johnson and increased his visibility among men of science.

As Tyson notes, although "Johnson's circle" is usually used in the singular, there were at least two such "circles". The first was made up of a group of London associates: Fuseli, Gregory, Bonnycastle, and Geddes. The second consisted of Johnson's writers from farther afield, such as Priestley, Thomas Henry,

As Tyson notes, although "Johnson's circle" is usually used in the singular, there were at least two such "circles". The first was made up of a group of London associates: Fuseli, Gregory, Bonnycastle, and Geddes. The second consisted of Johnson's writers from farther afield, such as Priestley, Thomas Henry,

As radicalism took hold in Britain in the 1790s, Johnson became increasingly involved in its causes: he was a member of the Society for Constitutional Information, which was attempting to reform Parliament; he published works defending

As radicalism took hold in Britain in the 1790s, Johnson became increasingly involved in its causes: he was a member of the Society for Constitutional Information, which was attempting to reform Parliament; he published works defending

The most notable of all of these responses was Thomas Paine's '' Rights of Man''. Johnson originally agreed to publish the controversial work, but he backed out later for unknown reasons and J. S. Jordan distributed it (and was subsequently tried and imprisoned for its publication). Braithwaite speculates that Johnson did not agree with Paine's radical republican statements and was more interested in promoting the rights of Dissenters outlined in the other works he published. After the initial risk was taken by Jordan, however, Johnson published Paine's work in an expensive edition, which was unlikely to be challenged at law. Yet, when Paine was himself later arrested, Johnson helped raise funds to bail him out and hid him from the authorities. A contemporary

The most notable of all of these responses was Thomas Paine's '' Rights of Man''. Johnson originally agreed to publish the controversial work, but he backed out later for unknown reasons and J. S. Jordan distributed it (and was subsequently tried and imprisoned for its publication). Braithwaite speculates that Johnson did not agree with Paine's radical republican statements and was more interested in promoting the rights of Dissenters outlined in the other works he published. After the initial risk was taken by Jordan, however, Johnson published Paine's work in an expensive edition, which was unlikely to be challenged at law. Yet, when Paine was himself later arrested, Johnson helped raise funds to bail him out and hid him from the authorities. A contemporary

Johnson continued to publish the poetic works of Aikin and Barbauld as well as those of George Dyer,

Johnson continued to publish the poetic works of Aikin and Barbauld as well as those of George Dyer,

In 1788, Johnson and Thomas Christie, a Unitarian, liberal, and classicist, founded the ''

In 1788, Johnson and Thomas Christie, a Unitarian, liberal, and classicist, founded the ''

Braithwaite explains, "an English jury, in effect, was being asked to consider whether Joseph Johnson's intentions as a bookseller were really as dangerous and radical as those of Thomas Paine". An issue of the ''

Braithwaite explains, "an English jury, in effect, was being asked to consider whether Joseph Johnson's intentions as a bookseller were really as dangerous and radical as those of Thomas Paine". An issue of the ''

Johnson was remarkably adept at recognizing new writing talent and making innovative works appealing to the public. More importantly, he functioned as a catalyst for experimentation by bringing disparate authors together. While Johnson promoted his authors, he retreated into the background himself. His friend

Johnson was remarkably adept at recognizing new writing talent and making innovative works appealing to the public. More importantly, he functioned as a catalyst for experimentation by bringing disparate authors together. While Johnson promoted his authors, he retreated into the background himself. His friend

here

* Smyser, Jane Worthington. "The trial and imprisonment of Joseph Johnson, bookseller". ''Bulletin of the New York Public Library'' 77 (1974): 418–435. * Tomalin, Claire. "Publisher in prison: Joseph Johnson and the book trade". ''Times Literary Supplement'' (2 December 1994): 15–16. * Tyson, Gerald P. ''Joseph Johnson: A Liberal Publisher''. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1979. .* * Uglow, Jenny. "The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World." Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2002. * Zall, P. M. "The cool world of Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Joseph Johnson, or, The perils of publishing". ''Wordsworth Circle'' 3 (1972): 25–30. {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Joseph 1738 births 1809 deaths British magazine publishers (people) English prisoners and detainees English booksellers English Dissenters English Unitarians Male feminists Publishers (people) from London Respiratory disease deaths in England

Johnson Circle and dinners

With time, Johnson's home became a nexus for radical thinkers, who appreciated his open-mindedness, generous spirit, and humanitarianism. Although usually separated by geography, such thinkers would meet and debate with one another at Johnson's house in London, often over dinner. This network not only brought authors into contact with each other, it also brought new writers to Johnson's business. For example, Priestley introducedJohn Newton

John Newton (; – 21 December 1807) was an English evangelical Anglican cleric and slavery abolitionist. He had previously been a captain of slave ships and an investor in the slave trade. He served as a sailor in the Royal Navy (after forc ...

to Johnson, Newton brought John Hewlett, and Hewlett invited Mary Wollstonecraft, who in turn attracted Mary Hays who brought William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

. With this broad network of acquaintances and reputation for free-thinking publications, Johnson became the favourite publisher of a generation of writers and thinkers. By bringing inventive, thoughtful people together, he "stood at the very heart of British intellectual life" for over twenty years. Importantly, Johnson's circle was not made up entirely of either liberals or radicals. Chard emphasizes that it "was held together less by political liberalism than by a common interest in ideas, free enquiry, and creative expression in various fields".

As Tyson notes, although "Johnson's circle" is usually used in the singular, there were at least two such "circles". The first was made up of a group of London associates: Fuseli, Gregory, Bonnycastle, and Geddes. The second consisted of Johnson's writers from farther afield, such as Priestley, Thomas Henry,

As Tyson notes, although "Johnson's circle" is usually used in the singular, there were at least two such "circles". The first was made up of a group of London associates: Fuseli, Gregory, Bonnycastle, and Geddes. The second consisted of Johnson's writers from farther afield, such as Priestley, Thomas Henry, Thomas Percival

Thomas Percival (29 September 1740 – 30 August 1804) was an English physician, health reformer, ethicist and author who wrote an early code of medical ethics. He drew up a pamphlet with the code in 1794 and wrote an expanded version in 18 ...

, Barbauld, Aikin, and Enfield. Later, more radicals would join, including Wollstonecraft, Wakefield, John Horne Tooke, and Thomas Christie.

Johnson's dinners became legendary and it appears, from evidence collected from diaries, that a large number of people attended each one. Although there were few regulars, except perhaps for Johnson's close London friends (Fuseli, Bonnycastle and, later, Godwin), the large number of high-profile guests, including Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

, attests to the reputation of these dinners. The enjoyment and intellectual stimulation that these dinners provided is evidenced by the numerous references to them in diaries and letters. Barbauld wrote to her brother in 1784 that "our evenings, particularly at Johnson's, were so truly social and lively, that we protracted them sometimes till – but I am not telling tales." At one dinner in 1791, Godwin records that the conversation focused on "monarch, Tooke, amuelJohnson, Voltaire, ''pursuits'', and religion" mphasis Godwin's Although the conversation was stimulating, Johnson apparently only served his guests simple meals, such as boiled cod, veal, vegetables, and rice pudding

Rice pudding is a dish made from rice mixed with water or milk and other ingredients such as cinnamon, vanilla and raisins.

Variants are used for either desserts or dinners. When used as a dessert, it is commonly combined with a sweetener such ...

. Many of the people that met at these dinners became fast friends, as did Fuseli and Bonnycastle; Godwin and Wollstonecraft eventually married.

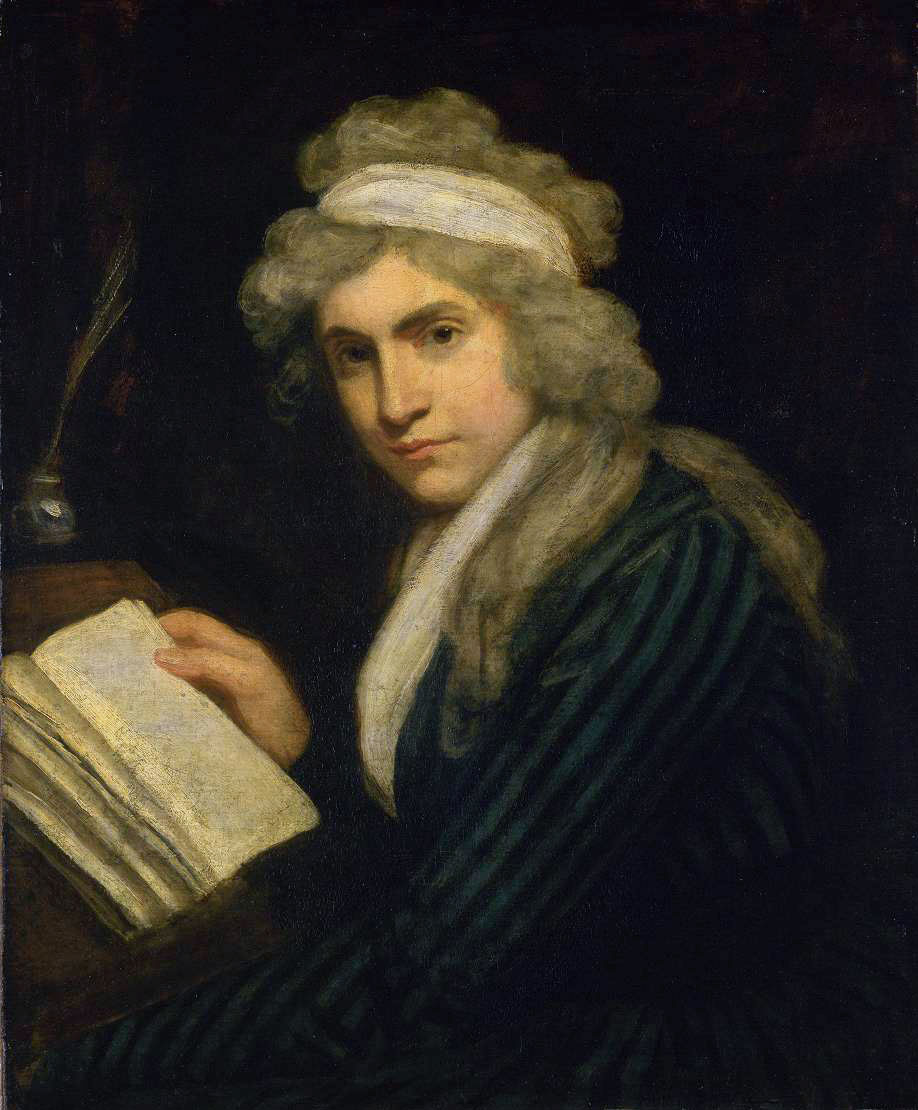

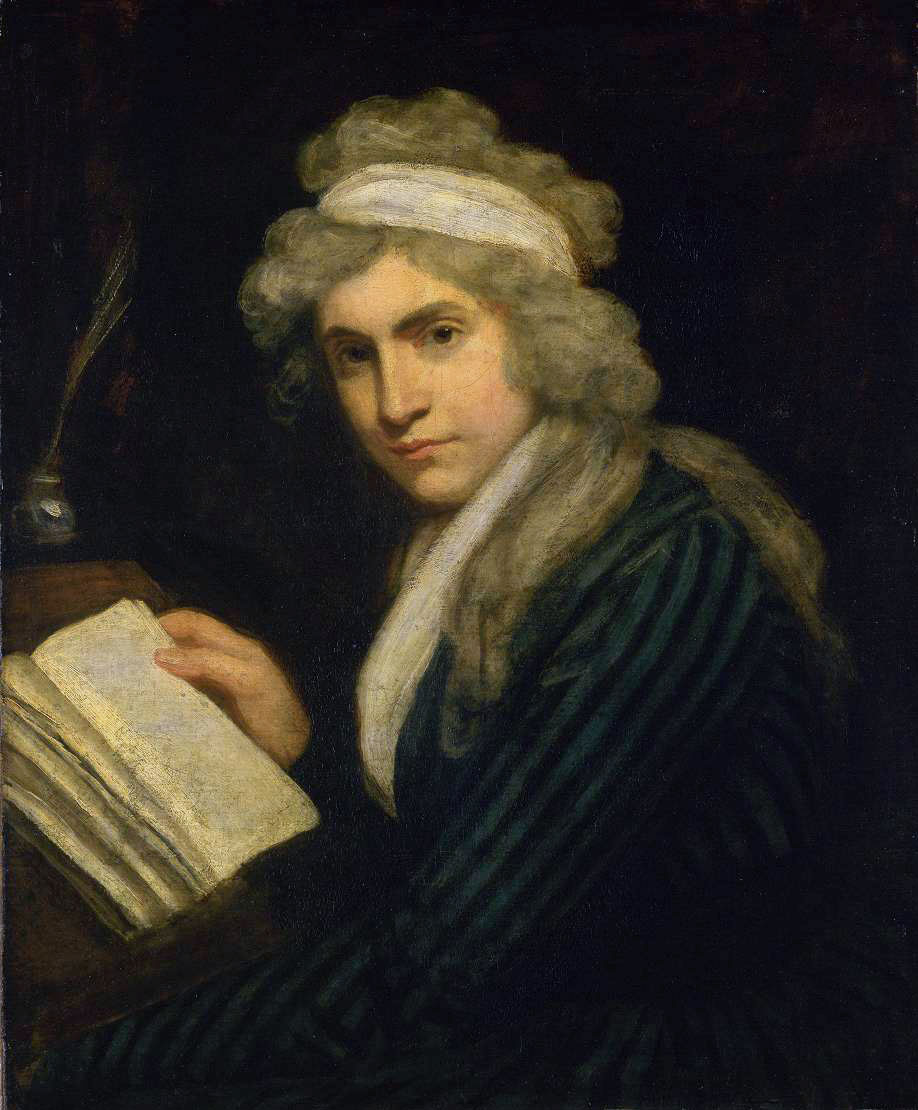

Friendship with Mary Wollstonecraft

The friendship between Johnson and Mary Wollstonecraft was pivotal in both of their lives, and illustrates the active role that Johnson played in developing writing talent. In 1787, Wollstonecraft was in financial straits: she had just been dismissed from agoverness

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, ...

position in Ireland and had moved back to London. She had resolved to be an author in an era that afforded few professional opportunities to women. After Unitarian schoolteacher John Hewlett suggested to Wollstonecraft that she submit her writings to Johnson, an enduring and mutually supportive relationship blossomed between Johnson and Wollstonecraft. He dealt with her creditors, secured lodgings for her, and advanced payment on her first book, ''Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

''Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life'' is the first published work of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Published in 1787 by her friend Joseph Johnson, ''Tho ...

'' (1787), and her first novel, '' Mary: A Fiction'' (1788). Johnson included Wollstonecraft in the exalted company of his weekly ''soirées'', where she met famous personages, such as Thomas Paine and her future husband, William Godwin. Wollstonecraft, who is believed to have written some 200 articles for his periodical, the ''Analytical Review

The ''Analytical Review'' was an English periodical that was published from 1788 to 1798, having been established in London by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publica ...

'', regarded Johnson as a true friend. After a disagreement, she sent him the following note the next morning:

You made me very low-spirited last night, by your manner of talking – You are my only friend – the only person I am intimate with. – I never had a father, or a brother – you have been both to me, ever since I knew you – yet I have sometimes been very petulant. – I have been thinking of those instances of ill-humour and quickness, and they appeared like crimes. Yours sincerely, Mary.Johnson offered Wollstonecraft work as a translator, prompting her to learn French and German. More importantly, Johnson provided encouragement at crucial moments during the writing of her seminal political treatises ''

A Vindication of the Rights of Men

''A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France'' (1790) is a political pamphlet, written by the 18th-century British writer and women's right ...

'' (1790) and ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

'' (1792).

1790s: Years of radicalism

As radicalism took hold in Britain in the 1790s, Johnson became increasingly involved in its causes: he was a member of the Society for Constitutional Information, which was attempting to reform Parliament; he published works defending

As radicalism took hold in Britain in the 1790s, Johnson became increasingly involved in its causes: he was a member of the Society for Constitutional Information, which was attempting to reform Parliament; he published works defending Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

after the religiously motivated Birmingham Riots in 1791; and he testified on behalf of those arrested during the 1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke an ...

. Johnson published works championing the rights of slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, women, prisoners, Dissenters, chimney sweeps, abused animals, university students forbidden from marrying, victims of press gangs

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

, and those unjustly accused of violating the game law

Game laws are statutes which regulate the right to pursue and take or kill certain kinds of fish and wild animal (game). Their scope can include the following: restricting the days to harvest fish or game, restricting the number of animals per per ...

s.

Political literature became Johnson's mainstay in the 1790s: he published 118 works, which amounted to 57% of his total political output. As Chard notes, "hardly a year went by without at least one anti-war and one anti-slave trade publication from Johnson". In particular, Johnson published abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

works, such as minister and former slave-ship captain John Newton's ''Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade'' (1788), Barbauld's ''Epistle to William Wilberforce'' (1791), and Captain John Gabriel Stedman's ''Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam'' (1796) (with illustrations by Blake). Most importantly he helped organize the publication of ''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African'', first published in 1789 in London,

'' (1789), the autobiography of former slave Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist from, according to his memoir, the Eboe (Igbo) region of the Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria). Enslaved a ...

.

Later in the decade, Johnson focused on works about the French revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, concentrating on those from France itself, but he also published commentary from America by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. Johnson's determination to publish political and revolutionary works, however, fractured his Circles: Dissenters were alienated from Anglicans during efforts to repeal the Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

and Corporation Acts and moderates split from radicals during the French revolution. Johnson lost customers, friends, and writers, including the children's author Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer (''née'' Kirby; 6 January 1741 – 15 December 1810) was a writer and critic of 18th-century British children's literature, as well as an educational reformer. Her periodical, ''The Guardian of Education'', helped to define the e ...

. Braithwaite speculates that Johnson also lost business due to his willingness to put out works that promoted the "challenging new historicist versions of the scriptures", such as those by Alexander Geddes

Alexander Geddes (14 September 1737 – 26 February 1802) was a Scottish theologian and scholar. He translated a major part of the Old Testament of the Catholic Bible into English.

Translations and commentaries

Geddes was born at Rathven, ...

.

Johnson refused to publish Paine's '' Rights of Man'' and William Blake's '' The French Revolution'', for example. It is almost impossible to determine Johnson's own personal political beliefs from the historical record. Marilyn Gaull argues that "if Johnson were radical, indeed if he had any political affiliation ... it was accidental".Gaull, 267–68. Gaull describes Johnson's "liberalism" as that "of generous, open, fair-minded, unbiased defender of causes lost and won". His real contribution, she contends, was "as a disseminator of contemporary knowledge, especially science, medicine, and pedagogical practice" and as an advocate for a popular style. He encouraged all of his writers to use "plain syntax and colloquial diction" so that "self-educated readers" could understand his publications. Johnson's association with writers such as Godwin has previously been used to emphasize his radicalism, but Braithwaite points out that Godwin only became a part of Johnson's Circle late in the 1790s; Johnson's closest friends – Priestley, Fuseli, and Bonnycastle – were much more politically moderate. Johnson was not a populist or democratic bookseller: he catered to the self-educating middle class.

Revolution controversy

In 1790, with the publication of his '' Reflections on the Revolution in France'', philosopher and statesmanEdmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

launched the first volley of a vicious pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

war in what became known as the Revolution Controversy. Because he had supported the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, friends and enemies alike expected him to support the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. His book, which decries the French Revolution, therefore came as a shock to nearly everyone. Priced at an expensive five shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

s, it still sold over 10,000 copies in a few weeks. Reformers, particularly Dissenters, felt compelled to reply. Johnson's periodical, the ''Analytical Review

The ''Analytical Review'' was an English periodical that was published from 1788 to 1798, having been established in London by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publica ...

'', published a summary and review of Burke's work within a couple of weeks of its publication. Two weeks later, Wollstonecraft responded to Burke with her ''Vindication of the Rights of Men

''A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France'' (1790) is a political pamphlet, written by the 18th-century British writer and women's rights ...

''. In issuing one of the first and cheapest replies to Burke (''Vindication'' cost only one shilling), Johnson put himself at some risk. Thomas Cooper, who had also written a response to Burke, was later informed by the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

that "although there was no exception to be taken to his pamphlet when in the hands of the upper classes, yet the government would not allow it to appear at a price which would insure its circulation among the people". Many others soon joined in the fray and Johnson remained at the centre of the maelstrom. By Braithwaite's count, Johnson published or sold roughly a quarter of the works responding to Burke within the following year.

The most notable of all of these responses was Thomas Paine's '' Rights of Man''. Johnson originally agreed to publish the controversial work, but he backed out later for unknown reasons and J. S. Jordan distributed it (and was subsequently tried and imprisoned for its publication). Braithwaite speculates that Johnson did not agree with Paine's radical republican statements and was more interested in promoting the rights of Dissenters outlined in the other works he published. After the initial risk was taken by Jordan, however, Johnson published Paine's work in an expensive edition, which was unlikely to be challenged at law. Yet, when Paine was himself later arrested, Johnson helped raise funds to bail him out and hid him from the authorities. A contemporary

The most notable of all of these responses was Thomas Paine's '' Rights of Man''. Johnson originally agreed to publish the controversial work, but he backed out later for unknown reasons and J. S. Jordan distributed it (and was subsequently tried and imprisoned for its publication). Braithwaite speculates that Johnson did not agree with Paine's radical republican statements and was more interested in promoting the rights of Dissenters outlined in the other works he published. After the initial risk was taken by Jordan, however, Johnson published Paine's work in an expensive edition, which was unlikely to be challenged at law. Yet, when Paine was himself later arrested, Johnson helped raise funds to bail him out and hid him from the authorities. A contemporary satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming o ...

suggested that Johnson saved Paine from imprisonment:

Alarmed at the popular appeal of Paine's ''Rights of Man'', the king issued a proclamation against seditious writings in May 1792. Booksellers and printers bore the brunt of this law, the effects of which came to a head in the 1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke an ...

. Johnson testified, publicly distancing himself from Paine and Barlow, despite the fact that the defendants were received sympathetically by the juries.

Poetry

During the 1790s alone, Johnson published 103 volumes of poetry – 37% of his entire output in the genre. The bestselling poetical works of Cowper andErasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

enriched Johnson's firm. Darwin's innovative ''The Botanic Garden

''The Botanic Garden'' (1791) is a set of two poems, ''The Economy of Vegetation'' and ''The Loves of the Plants'', by the British poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin. ''The Economy of Vegetation'' celebrates technological innovation and scien ...

'' (1791) was particularly successful: Johnson paid him 1,000 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

before it was ever released and bought the copyright from him for £800, a staggeringly large sum.Chard (1977), 142–44. The poem contains three "interludes" in the form of dialogues between a poet and his bookseller. The bookseller asks the poet what Tyson calls "leading question

In common law systems that rely on testimony by witnesses, a leading question is a question that suggests a particular answer and contains information the examiner is looking to have confirmed. The use of leading questions in court to elicit tes ...

s" in order to elucidate the poet's theory of poetry. Tyson comments "that although the flat questions of the practical-minded bookseller may be meant to parody Johnson's manner, most likely Darwin did not have him or any other particular bookseller in mind". After the success of ''The Botanic Garden'', Johnson published Darwin's work on evolution, ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794-96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology. Th ...

'' (1794–96); his treatise ''A Plan on the Conduct of Female Education'' (1797); ''Phytologia; or, the Philosophy of Agriculture and Gardening'' (1800); and his poem '' The Temple of Nature'' (1803). According to Braithwaite, ''The Temple of Nature'' was ''Zoonomia'' in verse and "horrified reviewers with its warring, factious, overly materialistic view of the universe".

Johnson continued to publish the poetic works of Aikin and Barbauld as well as those of George Dyer,

Johnson continued to publish the poetic works of Aikin and Barbauld as well as those of George Dyer, Joseph Fawcett

Joseph Fawcett (c. 1758 – 24 January 1804) was an 18th-century English Presbyterian minister and poet.

Fawcett began his education at Reverend French's school in Ware, Hertfordshire and in 1774 entered the dissenting academy at Daventry. At t ...

, James Hurdis, Joel Barlow, Ann Batten Cristall and Edward Williams. Most of the poets that Johnson promoted and published are not remembered today. However, in 1793, Johnson published William Wordsworth's ''An Evening Walk'' and ''Descriptive Sketches''; he remained Wordsworth's publisher until a disagreement separated them in 1799. Johnson also put out Samuel Taylor Coleridge's ''Fears of Solitude'' (1798). They were apparently close enough friends for Coleridge to leave his books at Johnson's shop when he toured Europe.

Johnson had a working relationship with illustrator William Blake