John Wilkinson (industrialist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John "Iron-Mad" Wilkinson (1728 – 14 July 1808) was an English

Bersham became well known for high-quality casting and a producer of guns and

Bersham became well known for high-quality casting and a producer of guns and

Wrexham County Borough Council

In 1775 John Wilkinson was the prime mover initiating the building of

In 1775 John Wilkinson was the prime mover initiating the building of

John Wilkinson made his fortune selling high quality goods made of iron and reached his limit of investment expansion. His expertise proved useful when he invested in many copper interests. In 1761 the Royal Navy clad the hull of the frigate with copper sheet to reduce the growth of marine biofouling and prevent attack by the Teredo shipworm. The drag from the hull growth cut the speed and the shipworm caused severe hull damage, especially in tropical waters. After the success of this work the Navy decreed that all ships should be clad and this created a large demand for copper that Wilkinson noted during his visits to shipyards. He bought shares in eight Cornish copper mines and met Thomas Williams, the 'Copper King' of the

John Wilkinson made his fortune selling high quality goods made of iron and reached his limit of investment expansion. His expertise proved useful when he invested in many copper interests. In 1761 the Royal Navy clad the hull of the frigate with copper sheet to reduce the growth of marine biofouling and prevent attack by the Teredo shipworm. The drag from the hull growth cut the speed and the shipworm caused severe hull damage, especially in tropical waters. After the success of this work the Navy decreed that all ships should be clad and this created a large demand for copper that Wilkinson noted during his visits to shipyards. He bought shares in eight Cornish copper mines and met Thomas Williams, the 'Copper King' of the

Wilkinson had a good reputation as an employer. Wherever new works were established, cottages were built to accommodate employees and their families. He gave significant financial support to his brother-in-law, the famous chemist Dr

Wilkinson had a good reputation as an employer. Wherever new works were established, cottages were built to accommodate employees and their families. He gave significant financial support to his brother-in-law, the famous chemist Dr

John married Ann Maudsley in 1759. Her family was wealthy and her

John married Ann Maudsley in 1759. Her family was wealthy and her

Wilkinson, John (1728–1808)

'. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011. * Newman, J. and

John Wilkinson Heritage

John Wilkinson — Encyclopædia Britannica

BBC — History — John Wilkinson (1728–1808)

Cumbria Directory entry

John Wilkinson (industrialist) Summary — BookRags

The Brymbo Heritage Groupbrymboheritage.co.uk

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wilkinson, John 1728 births 1808 deaths Foundrymen British ironmasters English inventors Machine tool builders People from Workington People of the Industrial Revolution Burials in Cumbria Deaths from diabetes High Sheriffs of Denbighshire 18th-century British engineers 18th-century English businesspeople

industrialist

A business magnate, also known as a tycoon, is a person who has achieved immense wealth through the ownership of multiple lines of enterprise. The term characteristically refers to a powerful entrepreneur or investor who controls, through per ...

who pioneered the manufacture of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

and the use of cast-iron goods during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. He was the inventor of a precision boring machine that could bore cast iron cylinders, such as cannon barrels and piston cylinders used in the steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

s of James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

. His boring machine has been called the first machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. Al ...

. He also developed a blowing device for blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheri ...

s that allowed higher temperatures, increasing their efficiency, and helped sponsor the first iron bridge in Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

This is where iron ore was first ...

. He is notable for his method of cannon boring, his techniques at casting iron and his work with the government of France to establish a cannon foundry.

Biography

Early life

John Wilkinson was born inLittle Clifton

Little Clifton is a village and civil parish in the district of Allerdale located on the edge of the Lake District in the county of Cumbria, England. In 2001, it had a population of 391 and contained 170 households; increasing to a population ...

, Bridgefoot

Bridgefoot is a village in Cumbria, historically part of Cumberland, near the Lake District National Park in England. It is situated at the confluence of the River Marron and Lostrigg Beck, approximately 1 mile south of the River Derwent. To t ...

, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

(now part of Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. ...

), the eldest son of Isaac Wilkinson and Mary Johnson. Isaac was then the potfounder at the blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheri ...

there, one of the first to use coke instead of charcoal, which was pioneered by Abraham Darby Abraham Darby may refer to:

People

*Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) the first of several men of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution. He developed a new method of producing pig iron with ...

.

John and his half-brother William, who was 17 years younger, were raised in a non-conformist Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

family and he was educated at a dissenting academy at Kendal, run by Dr Caleb Rotherham.Harris J R His sister Mary married another non-conformist, Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

in 1762. Priestley also played a role in educating John's younger brother, William.

In 1745, when John was 17, he was apprenticed to a Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

merchant for five years and then entered into partnership with his father.

When his father moved to Bersham furnace near Wrexham

Wrexham ( ; cy, Wrecsam; ) is a city and the administrative centre of Wrexham County Borough in Wales. It is located between the Welsh mountains and the lower Dee Valley, near the border with Cheshire in England. Historically in the count ...

in 1753 John remained at Kirkby Lonsdale

Kirkby Lonsdale () is a town and civil parish in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England, on the River Lune. Historically in Westmorland, it lies south-east of Kendal on the A65. The parish recorded a population of 1,771 in the 2001 ...

in Westmorland

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt ''Westmoreland'';R. Wilkinson The British Isles, Sheet The British IslesVision of Britain/ref> is a historic county in North West England spanning the southern Lake District and the northern Dales. It had an ...

where he married Ann Maudesley on 12 June 1755.

Iron master

After working with his father in his foundry, from 1755 John Wilkinson became a partner in the Bersham concern and in 1757 with partners, he erected a blast furnace at Willey, nearBroseley

Broseley is a market town in Shropshire, England, with a population of 4,929 at the 2011 Census and an estimate of 5,022 in 2019. The River Severn flows to its north and east. The first The Iron Bridge, iron bridge in the world was built in 17 ...

in Shropshire. Later he built another furnace and works at New Willey. He made his home in Broseley in a house called 'The Lawns' which became his headquarters for many years. He had houses either side of 'The Lawns' which served for administration, one being named 'The Mint' used for distribution of the thousands of tokens, each valued equivalent to a halfpenny. In East Shropshire he also developed iron works at Snedshill, Hollinswood, Hadley and Hampton Loade

Hampton Loade is a hamlet in Shropshire, England along the Severn Valley. It is situated on the east bank of the River Severn at , some five miles south of Bridgnorth, and is notable for the unusual current-operated Hampton Loade Ferry, a react ...

. He and Edward Blakeway also leased land to build another at Bradley

Bradley is an English surname derived from a place name meaning "broad wood" or "broad meadow" in Old English.

Like many English surnames Bradley can also be used as a given name and as such has become popular.

It is also an Anglicisation of t ...

works in Bilston

Bilston is a market town, ward, and civil parish located in Wolverhampton, West Midlands, England. It is close to the borders of Sandwell and Walsall. The nearest towns are Darlaston, Wednesbury, and Willenhall. Historically in Staffordshi ...

parish, near Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

. He became known as the Father of the extensive South Staffordshire iron industry with Bilston as the start of the Black Country

The Black Country is an area of the West Midlands county, England covering most of the Metropolitan Boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell and Walsall. Dudley and Tipton are generally considered to be the centre. It became industrialised during its ...

. In 1761, he took over Bersham Ironworks as well. Bradley became his largest and most successful enterprise, and was the site of extensive experiments in getting raw coal to substitute for coke in the production of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

. At its peak, it included a number of blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheri ...

s, a brick works, potteries, glass works, and rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

s. The Birmingham Canal

The BCN Main Line, or Birmingham Canal Navigations Main Line is the evolving route of the Birmingham Canal between Birmingham and Wolverhampton in England.

The name ''Main Line'' was used to distinguish the main Birmingham to Wolverhampton rout ...

was subsequently built near the Bradley works.

Inventions

Wilkinson was a prolific inventor of new products and processes, and especially anything connected with novel uses ofcast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

and wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

. His development of a machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. Al ...

for boring cast iron cannons presaged the accurate boring of cylinders for the first Watt steam engines. He also improved the air supply for the blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheri ...

using a new design of bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

, and was the first to use wrought iron in canal barges. He supported the construction of the first important cast iron bridge at Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

This is where iron ore was first ...

.

Cannon boring machine

cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

. Historically, cannons had been cast with a core and then bored to remove imperfections, but in 1774 Wilkinson patented a technique for boring iron guns from a solid piece, rotating the gun barrel rather than the boring-bar. This technique made the guns more accurate since the bore was uniform in diameter, and less likely to explode. While bronze cannons were already being bored from the solid, the boring of large iron naval cannon

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firing weapons and exclude ...

was novel. The patent was quashed in 1779 (the navy saw it as a monopoly and sought to overthrow it) but Wilkinson still remained a major manufacturer.

In 1792 Wilkinson bought the Brymbo Hall

Brymbo Hall, one of Britain's lost houses, was a manor house located near Brymbo outside the town of Wrexham, North Wales. The house, reputed to have been partly built to the designs of Inigo Jones,''Encyclopædia Britannica'', vol 24, 1911, p.8 ...

estate in Denbighshire

Denbighshire ( ; cy, Sir Ddinbych; ) is a county in the north-east of Wales. Its borders differ from the historic county of the same name. This part of Wales contains the country's oldest known evidence of habitation – Pontnewydd (Bontnewy ...

, not far from Bersham, where furnaces and other plant were installed. After his death and the decline of his industrial empire, the ironworks lay idle for some years until in 1842. It became once again an important works and eventually became Brymbo Steelworks

The Brymbo Steel Works was a former large steelworks in the village of Brymbo near Wrexham, Wales. In operation between 1796 and 1990, it was significant on account of its founder, one of whose original blast furnace stacks remains on the site ...

, which continued to operate until 1990.Brymbo Steelworks – The last tapWrexham County Borough Council

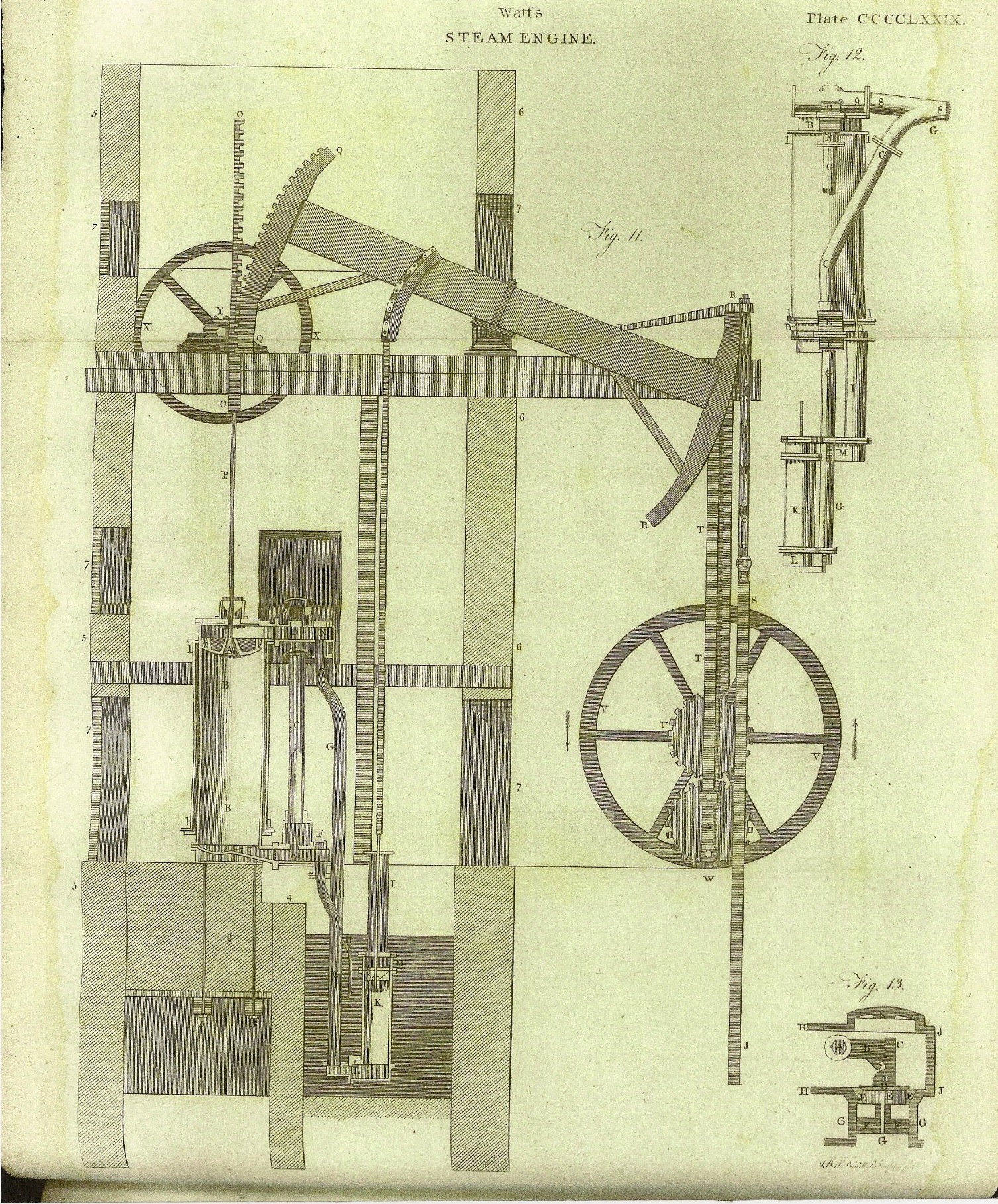

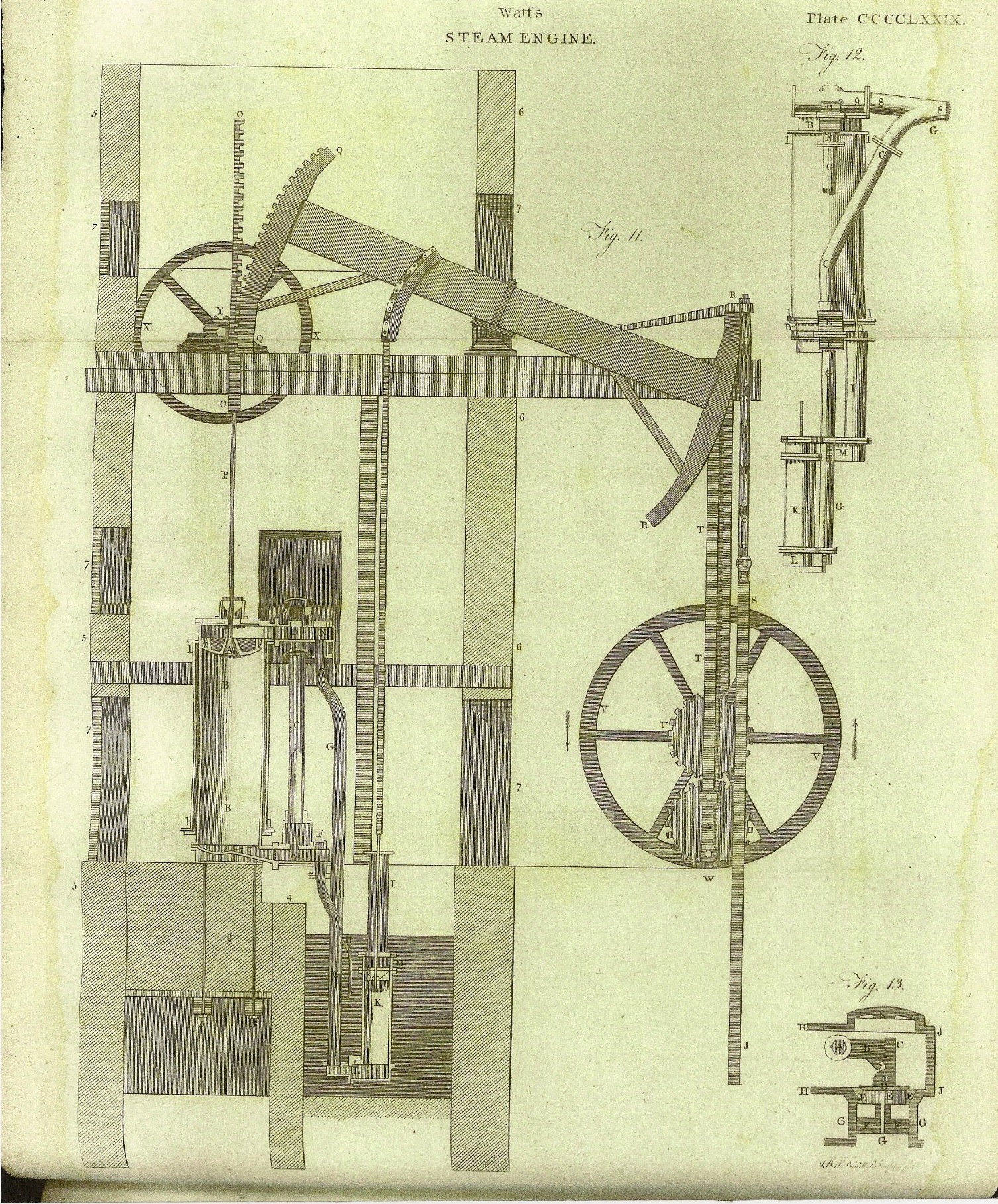

Boring machine for steam engines

James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

had tried unsuccessfully for several years to obtain accurately bored cylinders for his steam engines, and was forced to use hammered iron, which was out of round and caused leakage past the piston. In 1774 John Wilkinson invented a boring machine in which the shaft that held the cutting tool extended through the cylinder and was supported on both ends, unlike the cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is supported at only one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a cant ...

ed borers then in use. With this machine he was able to bore the cylinder for Boulton & Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Eng ...

's first commercial engine, and was given an exclusive contract for the provision of cylinders owing to the lower tolerance between the piston and cylinder and the resulting improvement in efficiency by lowering steam losses through the gap. Until this era, advancements in drilling and boring practice had lain only within the application field of gun barrels for firearms and cannon; Wilkinson's achievement was a milestone in the gradual development of boring technology, as its fields of application broadened into engines, pumps, and other industrial uses.

While the main market for steam engines had been for pumping water out of mines, he saw much more use for them in the driving of machinery in ironworks such as blowing engines, forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to th ...

hammer

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nails into wood, to shape metal (as wi ...

s and rolling mills, the first rotary engine

The rotary engine is an early type of internal combustion engine, usually designed with an odd number of cylinders per row in a radial configuration. The engine's crankshaft remained stationary in operation, while the entire crankcase and its ...

being installed at Bradley in 1783. Among his many inventions was a reversing rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

with two steam cylinders that made the process much more economical.

John Wilkinson took a key interest in obtaining orders for these more efficient steam engines and other uses for cast iron from the owners of Cornish copper mines. As part of this interest, he bought shares in eight of the mines to help provide capital.

Hydraulic blowing engine

In 1757 Wilkinson patented a hydraulic powered blowing engine to increase the air blast through thetuyeres

A tuyere or tuyère (; ) is a tube, nozzle or pipe through which air is blown into a furnace or hearth.W. K. V. Gale, The iron and Steel industry: a dictionary of terms (David and Charles, Newton Abbot 1972), 216–217.

Air or oxygen is inj ...

for blast furnaces, so improving the rate of production of cast iron. The historian Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, i ...

likened Wilkinson's design to the one described in 1313 by the Chinese Imperial Government metallurgist Wang Zhen in his ''Treatise on Agriculture''.

Iron Bridge

the Iron Bridge

The Iron Bridge is a cast iron arch bridge that crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Opened in 1781, it was the first major bridge in the world to be made of cast iron. Its success inspired the widespread use of cast iron as a st ...

connecting the then-important industrial town of Broseley with the other side of the River Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

. His friend Thomas Farnolls Pritchard

Thomas Farnolls Pritchard (also known as Farnolls Pritchard; baptised 11 May 1723 – died 23 December 1777) was an English architect and interior decorator who is best remembered for his design of the first cast-iron bridge in the world.

Biogra ...

had written to him with plans for the bridge. A committee of subscribers was formed, mostly including Broseley businessmen, to agree to the use of iron rather than wood or stone and obtain price quotations and an authorising act of Parliament.

Wilkinson's persuasion and drive held together the group's support through several problems during the parliamentary process. Had Wilkinson not succeeded in this and also drawn support from influential parliamentarians, the bridge might not have been built or might have been made of other materials. Consequently, the name 'Ironbridge' would not have been coined for the district in Madeley; the area would not have attained the status of a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

. Abraham Darby III

Abraham Darby III (24 April 1750 – 1789) was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Life

Abraham Darby ...

was chosen as the preferred builder after quoting to build the bridge for £3,150/-/-. When construction started, Wilkinson sold his shares to Abraham Darby III in 1777, leaving the latter to steer the project to its successful conclusion in 1779 and be opened in 1781.

In 1787 he launched the first barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels. ...

made of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

, constructed in Broseley

Broseley is a market town in Shropshire, England, with a population of 4,929 at the 2011 Census and an estimate of 5,022 in 2019. The River Severn flows to its north and east. The first The Iron Bridge, iron bridge in the world was built in 17 ...

. It was a development which would become common over the years ahead and in large ships in the following century. He patented several other inventions.

Copper interests

John Wilkinson made his fortune selling high quality goods made of iron and reached his limit of investment expansion. His expertise proved useful when he invested in many copper interests. In 1761 the Royal Navy clad the hull of the frigate with copper sheet to reduce the growth of marine biofouling and prevent attack by the Teredo shipworm. The drag from the hull growth cut the speed and the shipworm caused severe hull damage, especially in tropical waters. After the success of this work the Navy decreed that all ships should be clad and this created a large demand for copper that Wilkinson noted during his visits to shipyards. He bought shares in eight Cornish copper mines and met Thomas Williams, the 'Copper King' of the

John Wilkinson made his fortune selling high quality goods made of iron and reached his limit of investment expansion. His expertise proved useful when he invested in many copper interests. In 1761 the Royal Navy clad the hull of the frigate with copper sheet to reduce the growth of marine biofouling and prevent attack by the Teredo shipworm. The drag from the hull growth cut the speed and the shipworm caused severe hull damage, especially in tropical waters. After the success of this work the Navy decreed that all ships should be clad and this created a large demand for copper that Wilkinson noted during his visits to shipyards. He bought shares in eight Cornish copper mines and met Thomas Williams, the 'Copper King' of the Parys Mountain

Parys Mountain ( cy, Mynydd Parys) is located south of the town of Amlwch in north east Anglesey, Wales. It is the site of a large copper mine that was extensively exploited in the late 18th century. Parys Mountain is a mountain in name only, be ...

mines in Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

. Besides supplying Williams with large quantities of plate and equipment, Wilkinson also supplied scrap for the process of recovery of copper from solution by cementation. Wilkinson bought a 1/16th share in the Mona Mine at Parys Mountain and shares in Williams industries at Holywell, Flintshire

Holywell ( '','' cy, Treffynnon) is a market town and community in Flintshire, Wales. It lies to the west of the estuary of the River Dee. The community includes Greenfield.

Etymology

The name Holywell is literally ' + ' in reference to St W ...

, St Helens, near Liverpool and Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the C ...

, South Wales. Wilkinson and Williams worked together on several projects. They were amongst the first to issue trade tokens ('Willys' and 'Druids') to alleviate the shortage of small coins. Jointly they set up the Cornish Metal Company in 1785 as a marketing company for copper. Its aim was to ensure both a good return for the Cornish miners and a stable price for the users of copper. Warehouses were set up in Birmingham, London, Bristol and Liverpool.

To help his business interests and to service his trade tokens, Wilkinson bought into partnerships with banks in Birmingham, Bilston, Bradley, Brymbo and Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

.

Lead mines and works

Wilkinson bought lead mines at Minera in Wrexham, five miles from Bersham, Llyn Pandy at Soughton (now Sychdyn) and Mold, also in Flintshire. He installed steam pumping engines to make them viable again. His lead was exported through the port ofChester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

. To use some of the lead produced, Wilkinson had a lead pipe works at Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe () is a district of south-east London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, as well as the Isle of D ...

, London. This factory lasted for many years eventually making the solder filler alloys used in the car factory at Dagenham

Dagenham () is a town in East London, England, within the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Dagenham is centred east of Charing Cross.

It was historically a rural parish in the Becontree Hundred of Essex, stretching from Hainault Fore ...

.

Philanthropy

Wilkinson had a good reputation as an employer. Wherever new works were established, cottages were built to accommodate employees and their families. He gave significant financial support to his brother-in-law, the famous chemist Dr

Wilkinson had a good reputation as an employer. Wherever new works were established, cottages were built to accommodate employees and their families. He gave significant financial support to his brother-in-law, the famous chemist Dr Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

. He became a church warden in Broseley and was later elected High Sheriff of Denbighshire. In schools that had no slates he was able to provide iron troughs to hold sand for the practice of writing and arithmetic. He provided a cast-iron pulpit for the church at Bilston.

Family life, and death

John married Ann Maudsley in 1759. Her family was wealthy and her

John married Ann Maudsley in 1759. Her family was wealthy and her dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

helped to pay for a share in the New Willey Company. After the death of Ann, his second marriage, when he was 35, was to Mary Lee, whose money helped him to buy out his partners. When he was in his seventies, his mistress Mary Ann Lewis, a maid at his estate in Brymbo Hall, gave birth to his only children, a boy and two girls.

By 1796, when he was 68, he was producing about one-eighth of Britain's cast iron. He became "a titan" – very wealthy, and somewhat eccentric. His "iron madness" reached a peak in the 1790s, when he had almost everything around him made of iron, even several coffin

A coffin is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, either for burial or cremation.

Sometimes referred to as a casket, any box in which the dead are buried is a coffin, and while a casket was originally regarded as a box for j ...

s and a massive obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

to mark his grave, which still stands in the village of Lindale-in-Cartmel, now in Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. ...

. He was appointed Sheriff of Denbighshire for 1799.

He died on 14 July 1808 at his works in Bradley

Bradley is an English surname derived from a place name meaning "broad wood" or "broad meadow" in Old English.

Like many English surnames Bradley can also be used as a given name and as such has become popular.

It is also an Anglicisation of t ...

, probably from diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

. He was originally buried at his Castlehead estate at Grange-over-Sands, raised above the adjoining moss lands which he drained and improved from 1778 onwards.

He left a very large estate in his will (more than £130,000 - equivalent to £ in ), to which he intended to make his three children the principal heirs, with executors to manage the estate for them. However his nephew Thomas Jones contested the will in the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equ ...

. By 1828, the estate had largely been dissipated by lawsuits and poor management. His corpse, in its distinctive iron coffin, was moved several times over the next decades, but is now lost.Soldon, pp 347–348

References

Bibliography

* Braid, Douglas. ''Wilkinson Studies'' Vol II (1992) . * Chaloner, W.H. "Builders of Industry: John Wilkinson, Ironmaster." ''History Today'' (1951) 1#5 pp 63–69. * J. R. Harris,Wilkinson, John (1728–1808)

'. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011. * Newman, J. and

Pevsner, N.

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British history of art, art historian and history of architecture, architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county ...

''Pevsner Architectural Guides: The Buildings of Shropshire'', Yale University Press (2006). .

* Soldon, Norbert C. ''John Wilkinson (1728–1808): English Ironmaster and Inventor''. Studies in British History, Edwin Mellen Press, (1998) .

External links

John Wilkinson Heritage

John Wilkinson — Encyclopædia Britannica

BBC — History — John Wilkinson (1728–1808)

Cumbria Directory entry

John Wilkinson (industrialist) Summary — BookRags

The Brymbo Heritage Group

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wilkinson, John 1728 births 1808 deaths Foundrymen British ironmasters English inventors Machine tool builders People from Workington People of the Industrial Revolution Burials in Cumbria Deaths from diabetes High Sheriffs of Denbighshire 18th-century British engineers 18th-century English businesspeople