John W. N. Watkins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John William Nevill Watkins (31 July 1924 – 26 July 1999) was an English philosopher, a professor at the

John William Nevill Watkins (31 July 1924 – 26 July 1999) was an English philosopher, a professor at the

26

His most important work was ''Science and Scepticism'', published in 1984. In it he tried "to succeed where Descartes failed", and show how science could survive in the face of scepticism. In his book ''Human Freedom after Darwin,'' posthumously published in 1999, he returned to a problem that had long occupied him. Besides those about the influence of metaphysics on science, Watkins wrote classic and much-anthologised papers about

Preface

Contents.

Princeton 1984 (Princeton University Press). * ''Human Freedom after Darwin: A Critical Rationalist View.'' London 1999 (Open Court),

645

85. * "The Unity of Popper's Thought". In Paul A. Schilpp (ed.): ''The Philosophy of Karl Popper'', vol. I. La Salle, Illinois 1974 (Open Court), , pp. 371–412.

Catalogue of the Watkins papers held at LSE Archives

John William Nevill Watkins (31 July 1924 – 26 July 1999) was an English philosopher, a professor at the

John William Nevill Watkins (31 July 1924 – 26 July 1999) was an English philosopher, a professor at the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 milli ...

from 1966 until his retirement in 1989 and a prominent proponent of critical rationalism

Critical rationalism is an epistemological philosophy advanced by Karl Popper on the basis that, if a statement cannot be logically deduced (from what is known), it might nevertheless be possible to logically falsify it. Following Hume, Popper ...

.

Life

In 1952, Watkins married Micky Roe (one son, three daughters).Military service

In 1941, aged 17, Watkins passed out in the First Division from the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth and went straight into the wartimeNavy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

. He served in destroyers, escorting Russian convoys and the battleship carrying Churchill back from Marrakech

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

.

In 1944 he was decorated with the DSC for torpedoing a German destroyer off the French coast, part of an action which defeated the only remaining surface force that might have interfered with the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

.

Academic career

ReadingFriedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

's ''The Road to Serfdom

''The Road to Serfdom'' (German: ''Der Weg zur Knechtschaft'') is a book written between 1940 and 1943 by Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Since its publication in 1944, ''The Road to Serfdom'' has been popular among ...

'' (1944) on his destroyer aroused his interest in attending the LSE LSE may refer to:

Computing

* LSE (programming language), a computer programming language

* LSE, Latent sector error, a media assessment measure related to the hard disk drive storage technology

* Language-Sensitive Editor, a text editor used ...

where Hayek taught. A First in Political Science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and ...

and a prize-winning essay won him a Henry Ford Fellowship to Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, where he graduated MA in 1950. Then he returned to the LSE as assistant lecturer

Lecturer is an academic rank within many universities, though the meaning of the term varies somewhat from country to country. It generally denotes an academic expert who is hired to teach on a full- or part-time basis. They may also conduct re ...

in political science.

Watkins had attended Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the ...

's lectures at the LSE in logic and scientific method "and had fallen under his spell". 1958 he shifted from the Government Department to Popper's, being appointed Reader in Philosophy. Imre Lakatos

Imre Lakatos (, ; hu, Lakatos Imre ; 9 November 1922 – 2 February 1974) was a Hungarian philosopher of mathematics and science, known for his thesis of the fallibility of mathematics and its "methodology of proofs and refutations" in its pr ...

joined them in 1960. Watkins and Lakatos edited the ''British Journal for the Philosophy of Science

''British Journal for the Philosophy of Science'' (''BJPS'') is a peer-reviewed, academic journal of philosophy, owned by the British Society for the Philosophy of Science (BSPS) and published by University of Chicago Press. The journal publishes ...

'', and Watkins was President of the British Society for the Philosophy of Science from 1972 until 1975. When Popper retired in 1970, Watkins took over his chair.

After his retirement in 1989, Watkins played a leading role in establishing the Lakatos Award

The Lakatos Award is given annually for an outstanding contribution to the philosophy of science, widely interpreted. The contribution must be in the form of a monograph, co-authored or single-authored, and published in English during the prev ...

in the Philosophy of Science as the pre-eminent scholarly distinction in the field, honouring his former colleague Imre Lakatos who had died, aged only 51, in 1974.

On 26 July 1999, eleven weeks after completing his book ''Human Freedom after Darwin'', Watkins died of a heart attack while sailing his boat, ''Xantippe'', on the Salcombe estuary, South Devon, England.

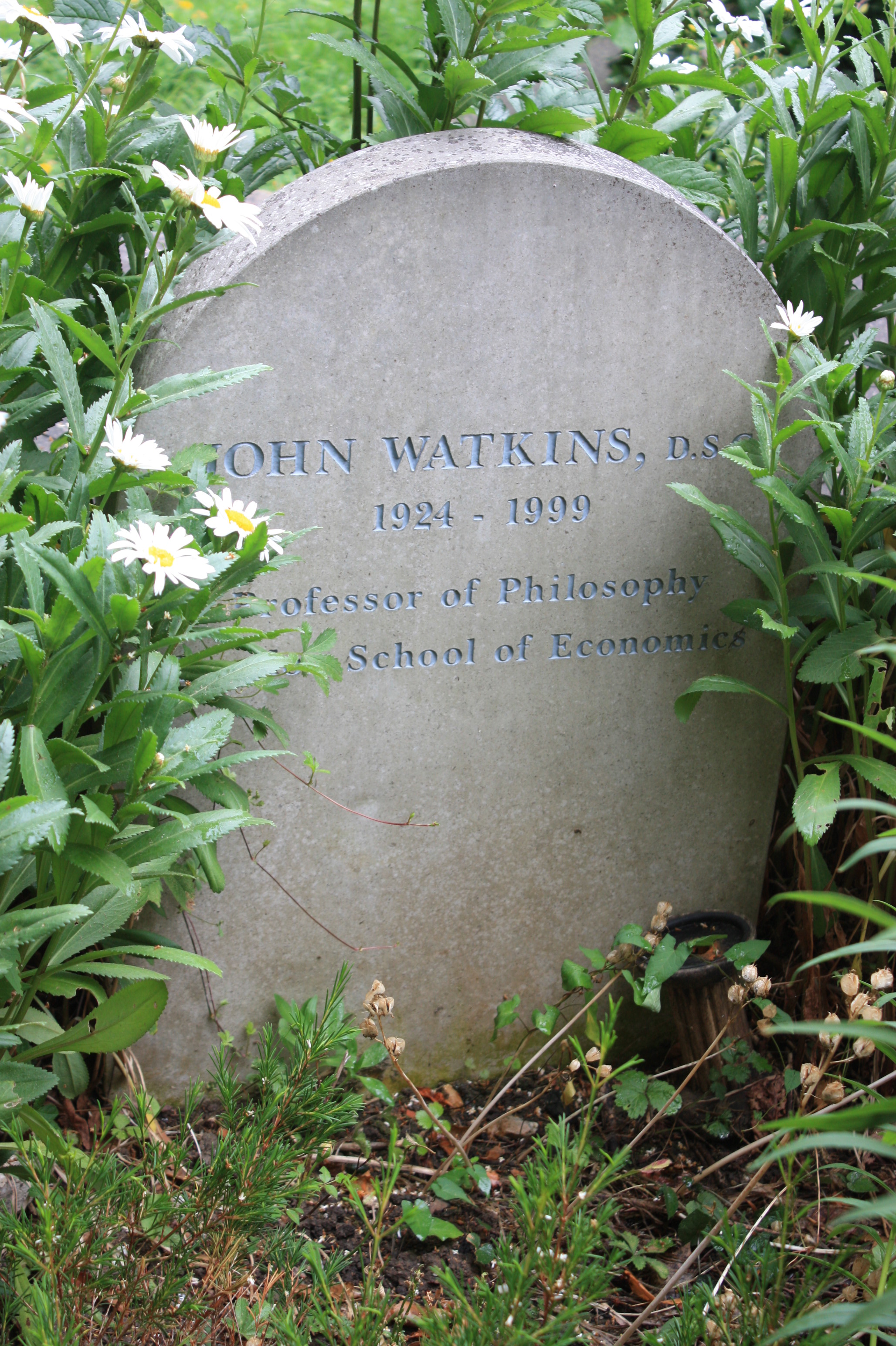

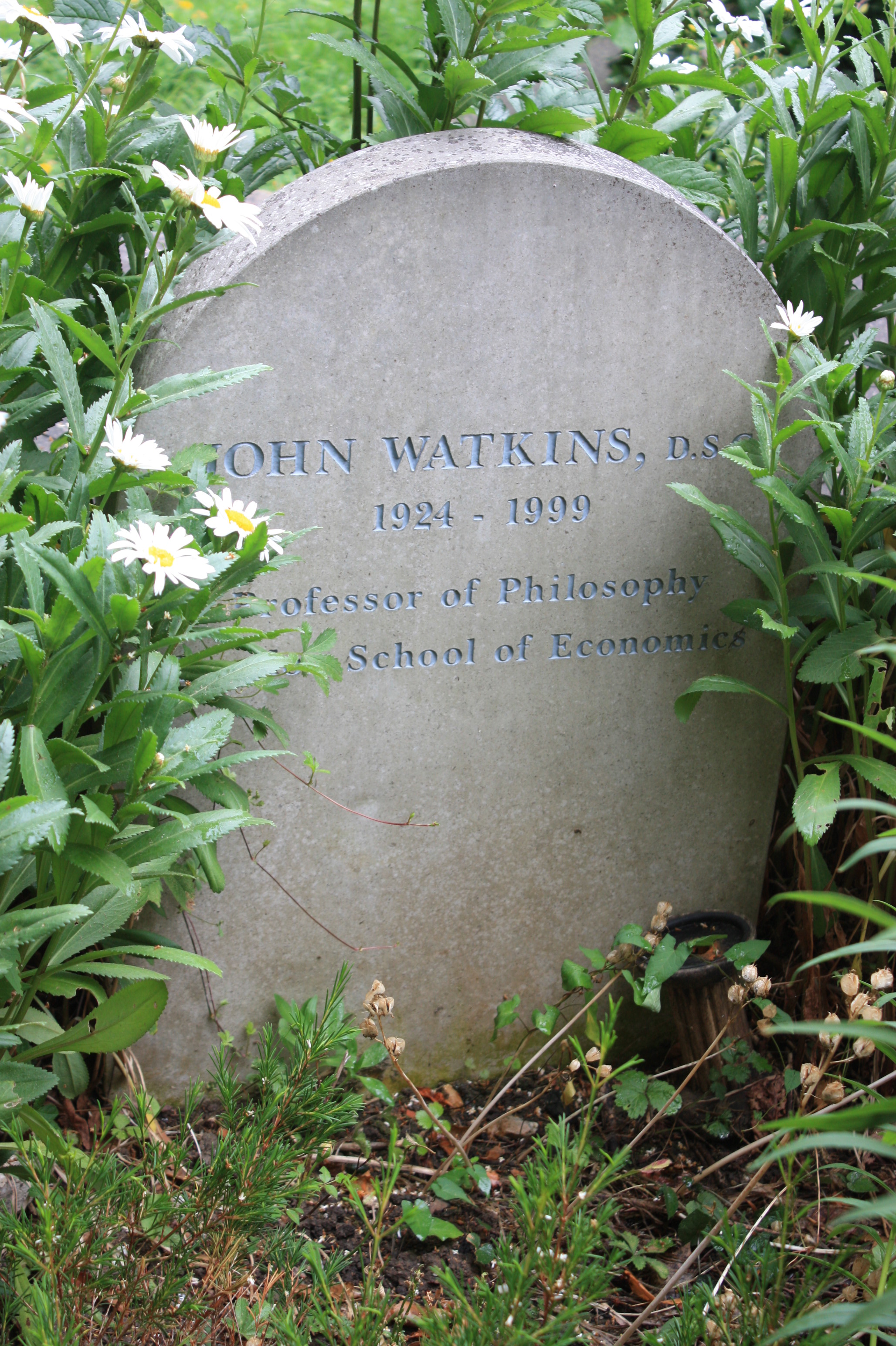

He is buried in the eastern section of Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in north London, England. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East Cemeteries. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for some of the people buried there as ...

not far from the main entrance on the northern path.

Philosophical work

Thatmetaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

propositions can influence scientific theorizing is indeed, arguably, Watkins' most lasting contribution to philosophy. He introduced a distinction between confirmable and influential metaphysics. According to Fred D'Agostino,

In 1965 Watkins published ''Hobbes's System of Ideas'', in which he argued that Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

's political theory follows from his philosophical ideas.

At an international symposium on ''Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge'' held in London in 1965, Watkins replied to a paper in which Thomas S. Kuhn had compared his own theory of scientific revolutions with Popper's falsificationism. He saw a clash between

:" uhn's view of the scientific communityas an essentially closed society, intermittently shaken by collective nervous breakdowns followed by restored mental unison, and Popper's view that the scientific community ought to be, and to a considerable degree actually is, an open society in which no theory, however dominant and successful, no 'paradigm', to use Kuhn's term, is ever sacred."Lakatos, Imre; Musgrave, Alan, eds. (1970). p26

His most important work was ''Science and Scepticism'', published in 1984. In it he tried "to succeed where Descartes failed", and show how science could survive in the face of scepticism. In his book ''Human Freedom after Darwin,'' posthumously published in 1999, he returned to a problem that had long occupied him. Besides those about the influence of metaphysics on science, Watkins wrote classic and much-anthologised papers about

methodological individualism

In the social sciences, methodological individualism is the principle that subjective individual motivation explains social phenomena, rather than class or group dynamics which are illusory or artificial and therefore cannot truly explain marke ...

, and about historical explanation.

Selected bibliography

Books

* ''Hobbes's System of Ideas: A Study in the Political Significance of Philosophical Theories.'' London 1965 (Hutchinson); ''LSE LSE may refer to:

Computing

* LSE (programming language), a computer programming language

* LSE, Latent sector error, a media assessment measure related to the hard disk drive storage technology

* Language-Sensitive Editor, a text editor used ...

reprint'' 1989.

* ''Science and Scepticism.'Preface

Contents.

Princeton 1984 (Princeton University Press). * ''Human Freedom after Darwin: A Critical Rationalist View.'' London 1999 (Open Court),

Essays

* * "Ideal Types and Historical Explanation". In Alan Ryan (ed.): ''The Philosophy of Social Explanation'', London 1973 (Oxford University Press), , pp. 82–104. * "Karl Raimund Popper, 1902-1994," ''Proceedings of the British Academy'', 1996, 94, pp645

85. * "The Unity of Popper's Thought". In Paul A. Schilpp (ed.): ''The Philosophy of Karl Popper'', vol. I. La Salle, Illinois 1974 (Open Court), , pp. 371–412.

Archives

Catalogue of the Watkins papers held at LSE Archives

See also

* *Rational fideism

Rational fideism is the philosophical view that considers faith to be precursor for any reliable knowledge. Every paradigmatic system, whether one considers rationalism or empiricism, is based on axioms that are neither self-founding nor self-evid ...

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Watkins, John W. N. 1924 births 1999 deaths Burials at Highgate Cemetery 20th-century English philosophers Academics of the London School of Economics Critical rationalists Philosophers of science Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Yale University alumni