John Rawls on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Bordley Rawls (; February 21, 1921 – November 24, 2002) was an American

Rawls graduated in Baltimore before enrolling in the Kent School, an

Rawls graduated in Baltimore before enrolling in the Kent School, an

Thinker at War: Rawls

published in Military History Monthly, 13 June 2014, accessed 20 November 2014. But he became disillusioned with the military when he saw the aftermath of the atomic blast in

In '' Political Liberalism'' (1993), Rawls turned towards the question of political legitimacy in the context of intractable philosophical, religious, and moral disagreement amongst citizens regarding the human good. Such disagreement, he insisted, was reasonable—the result of the free exercise of human rationality under the conditions of open enquiry and free conscience that the liberal state is designed to safeguard. The question of legitimacy in the face of reasonable disagreement was urgent for Rawls because his own justification of Justice as Fairness relied upon a Kantian conception of the human good that can be reasonably rejected. If the political conception offered in ''A Theory of Justice'' can only be shown to be good by invoking a controversial conception of human flourishing, it is unclear how a liberal state ordered according to it could possibly be legitimate.

The intuition animating this seemingly new concern is actually no different from the guiding idea of ''A Theory of Justice'', namely that the fundamental charter of a society must rely only on principles, arguments and reasons that cannot be reasonably rejected by the citizens whose lives will be limited by its social, legal, and political circumscriptions. In other words, the legitimacy of a law is contingent upon its justification being impossible to reasonably reject. This old insight took on a new shape, however, when Rawls realized that its application must extend to the deep justification of Justice as Fairness itself, which he had presented in terms of a reasonably rejectable (Kantian) conception of human flourishing as the free development of autonomous moral agency.

The core of Political Liberalism, accordingly, is its insistence that, in order to retain its legitimacy, the liberal state must commit itself to the "ideal of

In '' Political Liberalism'' (1993), Rawls turned towards the question of political legitimacy in the context of intractable philosophical, religious, and moral disagreement amongst citizens regarding the human good. Such disagreement, he insisted, was reasonable—the result of the free exercise of human rationality under the conditions of open enquiry and free conscience that the liberal state is designed to safeguard. The question of legitimacy in the face of reasonable disagreement was urgent for Rawls because his own justification of Justice as Fairness relied upon a Kantian conception of the human good that can be reasonably rejected. If the political conception offered in ''A Theory of Justice'' can only be shown to be good by invoking a controversial conception of human flourishing, it is unclear how a liberal state ordered according to it could possibly be legitimate.

The intuition animating this seemingly new concern is actually no different from the guiding idea of ''A Theory of Justice'', namely that the fundamental charter of a society must rely only on principles, arguments and reasons that cannot be reasonably rejected by the citizens whose lives will be limited by its social, legal, and political circumscriptions. In other words, the legitimacy of a law is contingent upon its justification being impossible to reasonably reject. This old insight took on a new shape, however, when Rawls realized that its application must extend to the deep justification of Justice as Fairness itself, which he had presented in terms of a reasonably rejectable (Kantian) conception of human flourishing as the free development of autonomous moral agency.

The core of Political Liberalism, accordingly, is its insistence that, in order to retain its legitimacy, the liberal state must commit itself to the "ideal of

''Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy.''

Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2000. This collection of lectures was edited by Barbara Herman. It has an introduction on modern moral philosophy from 1600 to 1800 and then lectures on Hume, Leibniz, Kant and Hegel. * '' Justice as Fairness: A Restatement.'' Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2001. This shorter summary of the main arguments of Rawls's political philosophy was edited by Erin Kelly. Many versions of this were circulated in typescript and much of the material was delivered by Rawls in lectures when he taught courses covering his own work at Harvard University.

''Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy.''

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007. Collection of lectures on

Original Position

* * Rawls, J. (1993/1996/2005) '' Political Liberalism'' (Columbia University Press, New York) * * * Rogers, B. (27.09.02) "Obituary: John Rawls

Obituary: John Rawls

* Tampio, N. (2011) "A Defense of Political Constructivism" (Contemporary Political Theory

* Wenar, Leif (2008) "John Rawls" (The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

John Rawls

*

* ttps://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-rawls-lexicon/56E9EFE4800DFA831929F3F563A9C016 Cambridge Rawls Lexicon

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on John Rawls by Henry S. Richardson

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Political Constructivisim by Michael Buckley

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on John Rawls by Leif Wenar

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Original Position by Fred D'Agostino

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Reflective Equilibrium by Norman Daniels

John Rawls

on

moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

, legal

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. ...

and political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studi ...

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

in the liberal tradition. Rawls received both the Schock Prize for Logic and Philosophy and the National Humanities Medal

The National Humanities Medal is an American award that annually recognizes several individuals, groups, or institutions for work that has "deepened the nation's understanding of the humanities, broadened our citizens' engagement with the huma ...

in 1999, the latter presented by President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

, in recognition of how Rawls's work "revived the disciplines of political and ethical philosophy with his argument that a society in which the most fortunate help the least fortunate is not only a moral society but a logical one".

In 1990, Will Kymlicka wrote in his introduction to the field that "it is generally accepted that the recent rebirth of normative political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

began with the publication of John Rawls's ''A Theory of Justice

''A Theory of Justice'' is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distrib ...

'' in 1971". Rawls has often been described as one of the most influential political philosophers of the 20th century. He has the unusual distinction among contemporary political philosophers of being frequently cited by the courts of law in the United States and Canada and referred to by practising politicians in the United States and the United Kingdom. In a 2008 national survey of political theorists, based on 1,086 responses from professors at accredited, four-year colleges and universities in the United States, Rawls was voted first on the list of "Scholars Who Have Had the Greatest Impact on Political Theory in the Past 20 Years".

Rawls's theory of "justice as fairness" recommends equal basic liberties, equality of opportunity, and facilitating the maximum benefit to the least advantaged members of society in any case where inequalities may occur. Rawls's argument for these principles of social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals ...

uses a thought experiment

A thought experiment is a hypothetical situation in which a hypothesis, theory, or principle is laid out for the purpose of thinking through its consequences.

History

The ancient Greek ''deiknymi'' (), or thought experiment, "was the most anc ...

called the " original position", in which people deliberately select what kind of society they would choose to live in if they did not know which social position they would personally occupy. In his later work '' Political Liberalism'' (1993), Rawls turned to the question of how political power could be made legitimate given reasonable disagreement about the nature of the good life.

Biography

Early life

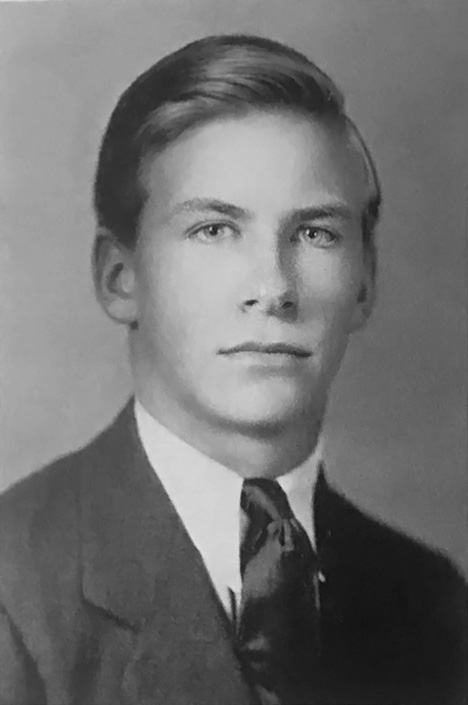

Rawls was born on February 21, 1921 inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

. He was the second of five sons born to William Lee Rawls, a prominent Baltimore attorney, and Anna Abell Stump Rawls.Freeman, 2010:xix Tragedy struck Rawls at a young age:

Two of his brothers died in childhood because they had contracted fatal illnesses from him. ... In 1928, the seven-year-old Rawls contractedRawls's biographerdiphtheria Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s .... His brother Bobby, younger by 20 months, visited him in his room and was fatally infected. The next winter, Rawls contractedpneumonia Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit .... Another younger brother, Tommy, caught the illness from him and died. Gordon, David (2008-07-28

Going Off the Rawls

, ''The American Conservative ''The American Conservative'' (''TAC'') is a magazine published by the American Ideas Institute which was founded in 2002. Originally published twice a month, it was reduced to monthly publication in August 2009, and since February 2013, it has ...''

Thomas Pogge

Thomas Winfried Menko Pogge (; born 13 August 1953) is a German philosopher and is the Director of the Global Justice Program and Leitner Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs at Yale University. In addition to his Yale appointment, ...

calls the loss of the brothers the "most important events in John's childhood."

Rawls graduated in Baltimore before enrolling in the Kent School, an

Rawls graduated in Baltimore before enrolling in the Kent School, an Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

preparatory school in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

. Upon graduation in 1939, Rawls attended Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, where he was accepted into The Ivy Club and the American Whig-Cliosophic Society

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

. At Princeton, Rawls was influenced by Norman Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian- British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is consi ...

's student. During his last two years at Princeton, he "became deeply concerned with theology and its doctrines." He considered attending a seminary to study for the Episcopal priesthood and wrote an "intensely religious senior thesis (''BI)''." In his 181-page long thesis titled "Meaning of Sin and Faith," Rawls attacked Pelagianism because it "would render the Cross of Christ to no effect." His argument was partly drawn from Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

's article '' On the Jewish Question'', which criticized the idea that natural inequality in ability could be a just determiner of the distribution of wealth in society. Even after Rawls became an atheist, many of the anti-Pelagian arguments he used were repeated in ''A Theory of Justice

''A Theory of Justice'' is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distrib ...

''. Rawls graduated from Princeton in 1943 with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

''summa cum laude''.

Military service, 1943–46

Rawls enlisted in the U.S. Army in February 1943. DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Rawls served as an infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

man in the Pacific, where he served a tour of duty in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

and was awarded a Bronze Star

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

W ...

; and the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, where he endured intensive trench warfare and witnessed traumatizing scenes of violence and bloodshed. It was there that he lost his Christian faith and became an atheist.

Following the surrender of Japan, Rawls became part of General MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

's occupying army and was promoted to sergeant.From article by Iain King, titleThinker at War: Rawls

published in Military History Monthly, 13 June 2014, accessed 20 November 2014. But he became disillusioned with the military when he saw the aftermath of the atomic blast in

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

. Rawls then disobeyed an order to discipline a fellow soldier, "believing no punishment was justified," and was "demoted back to a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

." Disenchanted, he left the military in January 1946.

Academic career

In early 1946, Rawls returned to Princeton to pursue a doctorate in moral philosophy. He married Margaret Warfield Fox, aBrown University

Brown University is a private research university in Providence, Rhode Island. Brown is the seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, founded in 1764 as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providenc ...

graduate, in 1949. They had four children, Anne Warfield, Robert Lee, Alexander Emory, and Elizabeth Fox.

Rawls received his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1950 after completing a doctoral dissertation titled ''A Study in the Grounds of Ethical Knowledge: Considered with Reference to Judgments on the Moral Worth of Character''. Rawls taught there until 1952 when he received a Fulbright Fellowship

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people ...

to Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

( Christ Church), where he was influenced by the liberal political theorist and historian Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

and the legal theorist H. L. A. Hart. After returning to the United States he served first as an assistant and then associate professor at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

. In 1962, he became a full professor of philosophy at Cornell, and soon achieved a tenured position at MIT. That same year, he moved to Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, where he taught for almost forty years and where he trained some of the leading contemporary figures in moral and political philosophy, including Sibyl A. Schwarzenbach, Thomas Nagel

Thomas Nagel (; born July 4, 1937) is an American philosopher. He is the University Professor of Philosophy and Law Emeritus at New York University, where he taught from 1980 to 2016. His main areas of philosophical interest are legal philosophy, ...

, Allan Gibbard, Onora O'Neill, Adrian Piper

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper (born September 20, 1948) is an American conceptual artist and Kantian philosopher. Her work addresses how and why those involved in more than one discipline may experience professional ostracism, otherness, racia ...

, Arnold Davidson

Arnold Ira Davidson (born 1955) is an American philosopher and academic, and the Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor in Philosophy, Comparative Literature, History of Science, and Philosophy of Religion at the University of ...

, Elizabeth S. Anderson

Elizabeth Secor Anderson (born December 5, 1959) is an American philosopher. She is Arthur F. Thurnau Professor and John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan and specializes in ...

, Christine Korsgaard

Christine Marion Korsgaard, (; born April 9, 1952) is an American philosopher who is the Arthur Kingsley Porter Professor of Philosophy Emerita at Harvard University. Her main scholarly interests are in moral philosophy and its history; the relat ...

, Susan Neiman, Claudia Card, Rainer Forst, Thomas Pogge

Thomas Winfried Menko Pogge (; born 13 August 1953) is a German philosopher and is the Director of the Global Justice Program and Leitner Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs at Yale University. In addition to his Yale appointment, ...

, T. M. Scanlon

Thomas Michael "Tim" Scanlon (; born 1940), usually cited as T. M. Scanlon, is an American philosopher. At the time of his retirement in 2016, he was the Alford Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy, and Civil Polity"The Alford Professo ...

, Barbara Herman, Joshua Cohen, Thomas E. Hill Jr., Gurcharan Das

Gurcharan Das (born 3 October 1943) is an Indian author, who wrote a trilogy based on the classical Indian goals of the ideal life.

''India Unbound'' was the first volume (2002), on artha, 'material well-being', which narrated the story of I ...

, Andreas Teuber, Samuel Freeman and Paul Weithman. He held the James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916 ...

University Professorship at Harvard.

Later life

Rawls rarely gave interviews and, having both a stutter (partially caused by the deaths of two of his brothers, who died through infections contracted from Rawls) and a "bat-like horror of the limelight,"Rogers, 27.09.02 did not become a public intellectual despite his fame. He instead remained committed mainly to his academic and family life. In 1995, he suffered the first of several strokes, severely impeding his ability to continue to work. He was nevertheless able to complete '' The Law of Peoples'', the most complete statement of his views on international justice, and published in 2001 shortly before his death '' Justice as Fairness: A Restatement'', a response to criticisms of ''A Theory of Justice

''A Theory of Justice'' is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distrib ...

''. Rawls died on November 24, 2002, at age 81, and was buried at the Mount Auburn Cemetery

Mount Auburn Cemetery is the first rural, or garden, cemetery in the United States, located on the line between Cambridge and Watertown in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, west of Boston. It is the burial site of many prominent Boston Brah ...

in Massachusetts. He was survived by his wife, Mard Rawls, and their four children, and four grandchildren.

Philosophical thought

Rawls published three main books. The first, ''A Theory of Justice'', focused on distributive justice and attempted to reconcile the competing claims of the values of freedom and equality. The second, ''Political Liberalism'', addressed the question of how citizens divided by intractable religious and philosophical disagreements could come to endorse a constitutional democratic regime. The third, ''The Law of Peoples'', focused on the issue of global justice.''A Theory of Justice''

''A Theory of Justice'', published in 1971, aimed to resolve the seemingly competing claims of freedom and equality. The shape Rawls's resolution took, however, was not that of a balancing act that compromised or weakened the moral claim of one value compared with the other. Rather, his intent was to show that notions of freedom and equality could be integrated into a seamless unity he called ''justice as fairness''. By attempting to enhance the perspective which his readers should take when thinking about justice, Rawls hoped to show the supposed conflict between freedom and equality to be illusory. Rawls's ''A Theory of Justice'' (1971) includes a thought experiment he called the " original position." The intuition motivating its employment is this: the enterprise of political philosophy will be greatly benefited by a specification of the correct standpoint a person should take in his or her thinking about justice. When we think about what it would mean for a just state of affairs to obtain between persons, we eliminate certain features (such as hair or eye color, height, race, etc.) and fixate upon others. Rawls's original position is meant to encode all of our intuitions about which features are relevant, and which irrelevant, for the purposes of deliberating well about justice. The original position is Rawls'shypothetical

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obser ...

scenario in which a group of persons is set the task of reaching an agreement about the kind of political and economic structure they want for a society, which they will then occupy. Each individual, however, deliberates behind a " veil of ignorance": each lacks knowledge, for example, of his or her gender, race, age, intelligence, wealth, skills, education and religion. The only thing that a given member knows about themselves is that they are in possession of the basic capacities necessary to fully and wilfully participate in an enduring system of mutual cooperation; each knows they can be a member of the society.

Rawls posits two basic capacities that the individuals would know themselves to possess. First, individuals know that they have the capacity to form, pursue and revise a conception of the good, or life plan. Exactly what sort of conception of the good this is, however, the individual does not yet know. It may be, for example, religious or secular, but at the start, the individual in the original position does not know which. Second, each individual understands him or herself to have the capacity to develop a sense of justice and a generally effective desire to abide by it. Knowing only these two features of themselves, the group will deliberate in order to design a social structure, during which each person will seek his or her maximal advantage. The idea is that proposals that we would ordinarily think of as unjust—such as that black people or women should not be allowed to hold public office—will not be proposed, in this, Rawls's original position, because it would be ''irrational'' to propose them. The reason is simple: one does not know whether he himself would be a woman or a black person. This position is expressed in the difference principle, according to which, in a system of ignorance about one's status, one would strive to improve the position of the worst off, because he might find himself in that position.

Rawls develops his original position by modelling it, in certain respects at least, after the "initial situations" of various social contract thinkers who came before him, including Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

and Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

. Each social contractarian constructs his/her initial situation somewhat differently, having in mind a unique political morality s/he intends the thought experiment to generate. Iain King has suggested the original position draws on Rawls's experiences in post-war Japan, where the US Army was challenged with designing new social and political authorities for the country, while "imagining away all that had gone before."

In social justice processes, each person early on makes decisions about which features of persons to consider and which to ignore. Rawls's aspiration is to have created a thought experiment whereby a version of that process is carried to its completion, illuminating the correct standpoint a person should take in his or her thinking about justice. If he has succeeded, then the original position thought experiment may function as a full specification of the moral standpoint we should attempt to achieve when deliberating about social justice.

In setting out his theory, Rawls described his method as one of " reflective equilibrium," a concept which has since been used in other areas of philosophy. Reflective equilibrium is achieved by mutually adjusting one's general principles and one's considered judgements on particular cases, to bring the two into line with one another.

Principles of justice

Rawls derives two principles of justice from the original position. The first of these is the Liberty Principle, which establishes equal basic liberties for all citizens. 'Basic' liberty entails the (familiar in the liberal tradition) freedoms of conscience, association and expression as well as democratic rights; Rawls also includes a ''personal property'' right, but this is defended in terms of moral capacities and self-respect, rather than an appeal to a natural right of self-ownership (this distinguishes Rawls's account from theclassical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, e ...

of John Locke and the libertarianism

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

of Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick (; November 16, 1938 – January 23, 2002) was an American philosopher. He held the Joseph Pellegrino University Professorship at Harvard University,

).

Rawls argues that a second principle of equality would be agreed upon to guarantee liberties that represent meaningful options for all in society and ensure distributive justice. For example, formal guarantees of political voice and freedom of assembly are of little real worth to the desperately poor and marginalized in society. Demanding that everyone have exactly the same effective opportunities in life would almost certainly offend the very liberties that are supposedly being equalized. Nonetheless, we would want to ensure at least the "fair worth" of our liberties: wherever one ends up in society, one wants life to be worth living, with enough effective freedom to pursue personal goals. Thus participants would be moved to affirm a two-part second principle comprising Fair Equality of Opportunity and the famous (and controversial) difference principle. This second principle ensures that those with comparable talents and motivation face roughly similar life chances and that inequalities in society work to the benefit of the least advantaged.

Rawls held that these principles of justice apply to the "basic structure" of fundamental social institutions (such as the judiciary, the economic structure and the political constitution), a qualification that has been the source of some controversy and constructive debate (see the work of Gerald Cohen). Rawls's theory of justice stakes out the task of equalizing the distribution of primary social goods to those least advantaged in society and thus may be seen as a largely political answer to the question of justice, with matters of morality somewhat conflated into a political account of justice and just institutions. Relational approaches to the question of justice, by contrast, seek to examine the connections between individuals and focuses on their relations in societies, with respect to how these relationships are established and configured.

Rawls further argued that these principles were to be 'lexically ordered' to award priority to basic liberties over the more equality-oriented demands of the second principle. This has also been a topic of much debate among moral and political philosophers.

Finally, Rawls took his approach as applying in the first instance to what he called a "well-ordered society ... designed to advance the good of its members and effectively regulated by a public conception of justice." In this respect, he understood justice as fairness as a contribution to "ideal theory," the determination of "principles that characterize a well-ordered society under favorable circumstances." Much recent work in political philosophy has asked what justice as fairness might dictate (or indeed, whether it is very useful at all) for problems of "partial compliance" under "nonideal theory."

''Political Liberalism''

In '' Political Liberalism'' (1993), Rawls turned towards the question of political legitimacy in the context of intractable philosophical, religious, and moral disagreement amongst citizens regarding the human good. Such disagreement, he insisted, was reasonable—the result of the free exercise of human rationality under the conditions of open enquiry and free conscience that the liberal state is designed to safeguard. The question of legitimacy in the face of reasonable disagreement was urgent for Rawls because his own justification of Justice as Fairness relied upon a Kantian conception of the human good that can be reasonably rejected. If the political conception offered in ''A Theory of Justice'' can only be shown to be good by invoking a controversial conception of human flourishing, it is unclear how a liberal state ordered according to it could possibly be legitimate.

The intuition animating this seemingly new concern is actually no different from the guiding idea of ''A Theory of Justice'', namely that the fundamental charter of a society must rely only on principles, arguments and reasons that cannot be reasonably rejected by the citizens whose lives will be limited by its social, legal, and political circumscriptions. In other words, the legitimacy of a law is contingent upon its justification being impossible to reasonably reject. This old insight took on a new shape, however, when Rawls realized that its application must extend to the deep justification of Justice as Fairness itself, which he had presented in terms of a reasonably rejectable (Kantian) conception of human flourishing as the free development of autonomous moral agency.

The core of Political Liberalism, accordingly, is its insistence that, in order to retain its legitimacy, the liberal state must commit itself to the "ideal of

In '' Political Liberalism'' (1993), Rawls turned towards the question of political legitimacy in the context of intractable philosophical, religious, and moral disagreement amongst citizens regarding the human good. Such disagreement, he insisted, was reasonable—the result of the free exercise of human rationality under the conditions of open enquiry and free conscience that the liberal state is designed to safeguard. The question of legitimacy in the face of reasonable disagreement was urgent for Rawls because his own justification of Justice as Fairness relied upon a Kantian conception of the human good that can be reasonably rejected. If the political conception offered in ''A Theory of Justice'' can only be shown to be good by invoking a controversial conception of human flourishing, it is unclear how a liberal state ordered according to it could possibly be legitimate.

The intuition animating this seemingly new concern is actually no different from the guiding idea of ''A Theory of Justice'', namely that the fundamental charter of a society must rely only on principles, arguments and reasons that cannot be reasonably rejected by the citizens whose lives will be limited by its social, legal, and political circumscriptions. In other words, the legitimacy of a law is contingent upon its justification being impossible to reasonably reject. This old insight took on a new shape, however, when Rawls realized that its application must extend to the deep justification of Justice as Fairness itself, which he had presented in terms of a reasonably rejectable (Kantian) conception of human flourishing as the free development of autonomous moral agency.

The core of Political Liberalism, accordingly, is its insistence that, in order to retain its legitimacy, the liberal state must commit itself to the "ideal of public reason Public reason requires that the moral or political rules that regulate our common life be, in some sense, justifiable or acceptable to all those persons over whom the rules purport to have authority. It is an idea with roots in the work of Thomas Ho ...

." This roughly means that citizens in their public capacity must engage one another only in terms of reasons whose status ''as'' reasons is shared between them. Political reasoning, then, is to proceed purely in terms of "public reasons." For example: a Supreme Court justice deliberating on whether or not the denial to homosexuals of the ability to marry constitutes a violation of the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause may not advert to his religious convictions on the matter, but he may take into account the argument that a same-sex household provides sub-optimal conditions for a child's development. This is because reasons based upon the interpretation of sacred text are non-public (their force as reasons relies upon faith commitments that can be reasonably rejected), whereas reasons that rely upon the value of providing children with environments in which they may develop optimally are public reasons—their status as reasons draws upon no deep, controversial conception of human flourishing.

Rawls held that the duty of civility—the duty of citizens to offer one another reasons that are mutually understood as reasons—applies within what he called the "public political forum." This forum extends from the upper reaches of government—for example the supreme legislative and judicial bodies of the society—all the way down to the deliberations of a citizen deciding for whom to vote in state legislatures or how to vote in public referendums. Campaigning politicians should also, he believed, refrain from pandering to the non-public religious or moral convictions of their constituencies.

The ideal of public reason secures the dominance of the public political values—freedom, equality, and fairness—that serve as the foundation of the liberal state. But what about the justification of these values? Since any such justification would necessarily draw upon deep (religious or moral) metaphysical commitments which would be reasonably rejectable, Rawls held that the public political values may only be justified privately by individual citizens. The public liberal political conception and its attendant values may and will be affirmed publicly (in judicial opinions and presidential addresses, for example) but its deep justifications will not. The task of justification falls to what Rawls called the "reasonable comprehensive doctrines" and the citizens who subscribe to them. A reasonable Catholic will justify the liberal values one way, a reasonable Muslim another, and a reasonable secular citizen yet another way. One may illustrate Rawls's idea using a Venn diagram: the public political values will be the shared space upon which overlap numerous reasonable comprehensive doctrines. Rawls's account of stability presented in ''A Theory of Justice'' is a detailed portrait of the compatibility of one—Kantian—comprehensive doctrine with justice as fairness. His hope is that similar accounts may be presented for many other comprehensive doctrines. This is Rawls's famous notion of an "overlapping consensus

''Overlapping consensus'' is a term coined by John Rawls in ''A Theory of Justice'' and developed in ''Political Liberalism''. The term ''overlapping consensus'' refers to how supporters of different comprehensive normative doctrines—that entail ...

."

Such a consensus would necessarily exclude some doctrines, namely, those that are "unreasonable", and so one may wonder what Rawls has to say about such doctrines. An unreasonable comprehensive doctrine is unreasonable in the sense that it is incompatible with the duty of civility. This is simply another way of saying that an unreasonable doctrine is incompatible with the fundamental political values a liberal theory of justice is designed to safeguard—freedom, equality and fairness. So one answer to the question of what Rawls has to say about such doctrines is—nothing. For one thing, the liberal state cannot justify itself to individuals (such as religious fundamentalists) who hold to such doctrines, because any such justification would—as has been noted—proceed in terms of controversial moral or religious commitments that are excluded from the public political forum. But, more importantly, the goal of the Rawlsian project is primarily to determine whether or not the liberal conception of political legitimacy is internally coherent, and this project is carried out by the specification of what sorts of reasons persons committed to liberal values are permitted to use in their dialogue, deliberations and arguments with one another about political matters. The Rawlsian project has this goal to the exclusion of concern with justifying liberal values to those not already committed—or at least open—to them. Rawls's concern is with whether or not the idea of political legitimacy fleshed out in terms of the duty of civility and mutual justification can serve as a viable form of public discourse in the face of the religious and moral pluralism of modern democratic society, not with justifying this conception of political legitimacy in the first place.

Rawls also modified the principles of justice as follows (with the first principle having priority over the second, and the first half of the second having priority over the latter half):

# Each person has an equal claim to a fully adequate scheme of basic rights and liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme for all; and in this scheme the equal political liberties, and only those liberties, are to be guaranteed their fair value.

# Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions: first, they are to be attached to positions and offices open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity; and second, they are to be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society.

These principles are subtly modified from the principles in ''Theory''. The first principle now reads "equal claim" instead of "equal right", and he also replaces the phrase "system of basic liberties" with "a fully adequate scheme of equal basic rights and liberties". The two parts of the second principle are also switched, so that the difference principle becomes the latter of the three.

''The Law of Peoples''

Although there were passing comments on international affairs in ''A Theory of Justice'', it was not until late in his career that Rawls formulated a comprehensive theory of international politics with the publication of ''The Law of Peoples''. He claimed there that "well-ordered" peoples could be either "liberal" or "decent". Rawls's basic distinction in international politics is that his preferred emphasis on a society of peoples is separate from the more conventional and historical discussion of international politics as based on relationships between states. Rawls argued that the legitimacy of a liberal international order is contingent on tolerating ''decent peoples'', which differ from ''liberal peoples'', among other ways, in that they might have state religions and deny adherents of minorityfaith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

s the right to hold positions of power within the state, and might organize political participation via consultation hierarchies rather than elections. However, no well-ordered peoples may violate human rights or behave in an externally aggressive manner. Peoples that fail to meet the criteria of "liberal" or "decent" peoples are referred to as 'outlaw states', 'societies burdened by unfavourable conditions' or 'benevolent absolutisms', depending on their particular failings. Such peoples do not have the right to mutual respect and toleration possessed by liberal and decent peoples.

Rawls's views on global distributive justice as they were expressed in this work surprised many of his fellow egalitarian liberals. For example, Charles Beitz

Charles R. Beitz (born 1949) is an American political theorist. He is Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton University, where he has been director of the University Center for Human Values and director of the Program in Political ...

had previously written a study that argued for the application of Rawls's Difference Principles globally. Rawls denied that his principles should be so applied, partly on the grounds that a world state does not exist and would not be stable. This notion has been challenged, as a comprehensive system of global governance has arisen, amongst others in the form of the Bretton Woods system

The Bretton Woods system of monetary management established the rules for commercial and financial relations among the United States, Canada, Western European countries, Australia, and Japan after the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement. The Bretto ...

, that serves to distribute primary social goods between human beings. It has thus been argued that a cosmopolitan application of the theory of justice as fairness is the more reasonable alternative to the application of The Law of Peoples, as it would be more legitimate towards all persons over whom political coercive power is exercised.

According to Rawls however, nation states, unlike citizens, were self-sufficient in the cooperative enterprises that constitute domestic societies. Although Rawls recognized that aid should be given to governments which are unable to protect human rights for economic reasons, he claimed that the purpose for this aid is not to achieve an eventual state of global equality, but rather only to ensure that these societies could maintain liberal or decent political institutions. He argued, among other things, that continuing to give aid indefinitely would see nations with industrious populations subsidize those with idle populations and would create a moral hazard

In economics, a moral hazard is a situation where an economic actor has an incentive to increase its exposure to risk because it does not bear the full costs of that risk. For example, when a corporation is insured, it may take on higher risk ...

problem where governments could spend irresponsibly in the knowledge that they will be bailed out by those nations who had spent responsibly.

Rawls's discussion of "non-ideal" theory, on the other hand, included a condemnation of bombing civilians and of the American bombing of German and Japanese cities in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, as well as discussions of immigration and nuclear proliferation. He also detailed here the ideal of the statesman, a political leader who looks to the next generation and promotes international harmony, even in the face of significant domestic pressure to act otherwise. Rawls also controversially claimed that violations of human rights can legitimize military intervention in the violating states, though he also expressed the hope that such societies could be induced to reform peacefully by the good example of liberal and decent peoples.

Influence and reception

Despite the exacting, academic tone of Rawls's writing and his reclusive personality, his philosophical work has exerted an enormous impact on not only contemporary moral and political philosophy but also public political discourse. During the student protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989, copies of "A Theory of Justice" were brandished by protesters in the face of government officials. Despite being approximately 600 pages long, over 300,000 copies of that book have been sold, stimulating critical responses fromutilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

, feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

, Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, communitarian

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

, Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

and Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by a combin ...

scholars, which Rawls welcomed.

Although having a profound influence on theories of distributive justice both in theory and in practice, the generally anti-meritocratic

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and ac ...

sentiment of Rawls's thinking has not been widely accepted by the political left. He consistently held the view that naturally developed skills and endowments could not be neatly distinguished from inherited ones, and that neither could be used to justify moral desert. Instead, he held the view that individuals could "legitimately expect" entitlements to the earning of income or development of abilities based on institutional arrangements. This aspect of Rawls's work has been instrumental in the development of such ideas as luck egalitarianism

Luck egalitarianism is a view about distributive justice espoused by a variety of egalitarian and other political philosophers. According to this view, justice demands that variations in how well-off people are should be wholly determined by the ...

and unconditional basic income, which have themselves been criticized. The strictly egalitarian quality of Rawls's second principle of justice has called into question the type of equality that fair societies ought to embody.

In a 2008 national survey of political theorists, based on 1,086 responses from professors at accredited, four-year colleges and universities in the United States, Rawls was voted first on the list of "Scholars Who Have Had the Greatest Impact on Political Theory in the Past 20 Years".

The Communitarian Critique

Charles Taylor,Alasdair Macintyre

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre (; born 12 January 1929) is a Scottish-American philosopher who has contributed to moral and political philosophy as well as history of philosophy and theology. MacIntyre's '' After Virtue'' (1981) is one of the mos ...

, Michael Sandel, and Michael Walzer

Michael Laban Walzer (born 1935) is an American political theorist and public intellectual. A professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, he is editor emeritus of '' Dissent'', an intellectual magazin ...

produced a range of critical responses contesting the universalist basis of Rawls' original position. While these criticisms, which emphasise the cultural and social roots of normative political principles, are typically described as communitarian

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

critiques of Rawlsian liberalism, none of their authors identified with philosophical communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

. In his later works, Rawls attempted to reconcile his theory of justice with the possibility that its normative foundations may not be universally applicable.

The September Group

The late philosopherG. A. Cohen

Gerald Allan Cohen, ( ; 14 April 1941 – 5 August 2009) was a Canadian political philosopher who held the positions of Quain Professor of Jurisprudence, University College London and Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory, All So ...

, along with political scientist Jon Elster

Jon Elster (; born 22 February 1940, Oslo) is a Norwegian philosopher and political theorist who holds the Robert K. Merton professorship of Social Science at Columbia University.

He received his PhD in social science from the École Norma ...

, and John Roemer, used Rawls's writings extensively to inaugurate the Analytical Marxism movement in the 1980s.

The Frankfurt School

In the later part of Rawl's career, he engaged with the scholarly work ofJürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas (, ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt School, Habermas's wo ...

(see Habermas-Rawls debate). Habermas's reading of Rawls led to an appreciation of Rawls's work and other analytical philosophers by the Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School (german: Frankfurter Schule) is a school of social theory and critical philosophy associated with the Institute for Social Research, at Goethe University Frankfurt in 1929. Founded in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), dur ...

of critical theory

A critical theory is any approach to social philosophy that focuses on society and culture to reveal, critique and challenge power structures. With roots in sociology and literary criticism, it argues that social problems stem more from s ...

, and many of Habermas's own students and associates were expected to be familiar with Rawls by the late 1980s. Rainer Forst, who was described in 2012 as the "most important political philosopher of his generation" was advised both by Rawls and Habermas in completing his PhD. Axel Honneth

Axel Honneth (; ; born 18 July 1949) is a German philosopher who is the Professor for Social Philosophy at Goethe University Frankfurt and the Jack B. Weinstein Professor of the Humanities in the department of philosophy at Columbia University ...

, Fabian Freyenhagen, and James Gordon Finlayson have also drawn on Rawls's work in comparison to Habermas.

Feminist political philosophy

PhilosopherEva Kittay

Eva Feder Kittay is an American philosopher. She is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy ( Emerita) at Stony Brook University. Her primary interests include feminist philosophy, ethics, social and political theory, metaphor, and the application ...

has extended the work of John Rawls to address the concerns of women and the cognitively disabled.

Awards and honors

*Bronze Star

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

W ...

for radio work behind enemy lines in World War II.

* Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

(1966)

* Ralph Waldo Emerson Award The Ralph Waldo Emerson Award is a non-fiction literary award given by the Phi Beta Kappa society, the oldest academic society of the United States, for books that have made the most significant contributions to the humanities. Albert William Levi ...

(1972)

* Elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

(1974)

* Member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters

The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters ( no, Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi, DNVA) is a learned society based in Oslo, Norway. Its purpose is to support the advancement of science and scholarship in Norway.

History

The Royal Frederick Unive ...

(1992)

* Schock Prize for Logic and Philosophy (1999)

* National Humanities Medal

The National Humanities Medal is an American award that annually recognizes several individuals, groups, or institutions for work that has "deepened the nation's understanding of the humanities, broadened our citizens' engagement with the huma ...

(1999)

* Asteroid 16561 Rawls is named in his honor.

Musical

John Rawls is featured as the protagonist of '' A Theory of Justice: The Musical!'', an award-nominated musical comedy, which premiered at Oxford in 2013 and was revived for the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.Publications

Bibliography

* ''A Study in the Grounds of Ethical Knowledge: Considered with Reference to Judgments on the Moral Worth of Character''.Ph.D. dissertation

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, Princeton University, 1950.

* ''A Theory of Justice

''A Theory of Justice'' is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distrib ...

.'' Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971. The revised edition of 1999 incorporates changes that Rawls made for translated editions of ''A Theory of Justice.'' Some Rawls scholars use the abbreviation TJ to refer to this work.

* '' Political Liberalism. The John Dewey Essays in Philosophy, 4.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. The hardback edition published in 1993 is not identical. The paperback adds a valuable new introduction and an essay titled "Reply to Habermas." Some Rawls scholars use the abbreviation PL to refer to this work.

* '' The Law of Peoples: with "The Idea of Public Reason Revisited."'' Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999. This slim book includes two works; a further development of his essay entitled "The Law of Peoples" and another entitled "Public Reason Revisited," both published earlier in his career.

* ''Collected Papers.'' Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999. This collection of shorter papers was edited by Samuel Freeman.

''Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy.''

Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2000. This collection of lectures was edited by Barbara Herman. It has an introduction on modern moral philosophy from 1600 to 1800 and then lectures on Hume, Leibniz, Kant and Hegel. * '' Justice as Fairness: A Restatement.'' Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2001. This shorter summary of the main arguments of Rawls's political philosophy was edited by Erin Kelly. Many versions of this were circulated in typescript and much of the material was delivered by Rawls in lectures when he taught courses covering his own work at Harvard University.

''Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy.''

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007. Collection of lectures on

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

, Joseph Butler, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, edited by Samuel Freeman.

* ''A Brief Inquiry into the Meaning of Sin and Faith.'' Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2010. With introduction and commentary by Thomas Nagel, Joshua Cohen and Robert Merrihew Adams. Senior thesis, Princeton, 1942. This volume includes a brief late essay by Rawls entitled ''On My Religion''.

Articles

* "Outline of a Decision Procedure for Ethics." ''Philosophical Review'' (April 1951), 60 (2): 177–197. * "Two Concepts of Rules." ''Philosophical Review'' (January 1955), 64 (1):3–32. * "Justice as Fairness." ''Journal of Philosophy'' (October 24, 1957), 54 (22): 653–362. * "Justice as Fairness." ''Philosophical Review'' (April 1958), 67 (2): 164–194. * "The Sense of Justice." ''Philosophical Review'' (July 1963), 72 (3): 281–305. * "Constitutional Liberty and the Concept of Justice" ''Nomos VI'' (1963) * "Distributive Justice: Some Addenda." Natural Law Forum (1968), 13: 51–71. * "Reply to Lyons and Teitelman." ''Journal of Philosophy'' (October 5, 1972), 69 (18): 556–557. * "Reply to Alexander and Musgrave." ''Quarterly Journal of Economics'' (November 1974), 88 (4): 633–655. * "Some Reasons for the Maximin Criterion." ''American Economic Review'' (May 1974), 64 (2): 141–146. * "Fairness to Goodness." ''Philosophical Review'' (October 1975), 84 (4): 536–554. * "The Independence of Moral Theory." ''Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association'' (November 1975), 48: 5–22. * "A Kantian Conception of Equality." ''Cambridge Review'' (February 1975), 96 (2225): 94–99. * "The Basic Structure as Subject." ''American Philosophical Quarterly'' (April 1977), 14 (2): 159–165. * "Kantian Constructivism in Moral Theory." ''Journal of Philosophy'' (September 1980), 77 (9): 515–572. * "Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical." ''Philosophy & Public Affairs'' (Summer 1985), 14 (3): 223–251. * "The Idea of an Overlapping Consensus." ''Oxford Journal for Legal Studies'' (Spring 1987), 7 (1): 1–25. * "The Priority of Right and Ideas of the Good." ''Philosophy & Public Affairs'' (Fall 1988), 17 (4): 251–276. * "The Domain of the Political and Overlapping Consensus." ''New York University Law Review'' (May 1989), 64 (2): 233–255. * "Roderick Firth: His Life and Work." ''Philosophy and Phenomenological Research'' (March 1991), 51 (1): 109–118. * "The Law of Peoples." ''Critical Inquiry'' (Fall 1993), 20 (1): 36–68. * "Political Liberalism: Reply to Habermas." ''Journal of Philosophy'' (March 1995), 92 (3):132–180. * "The Idea of Public Reason Revisited." ''Chicago Law Review'' (1997), 64 (3): 765–807. RRBook chapters

* "Constitutional Liberty and the Concept of Justice." In Carl J. Friedrich and John W. Chapman, eds., ''Nomos, VI: Justice,'' pp. 98–125. Yearbook of the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy. New York: Atherton Press, 1963. * "Legal Obligation and the Duty of Fair Play." In Sidney Hook, ed., ''Law and Philosophy: A Symposium'', pp. 3–18. New York: New York University Press, 1964. Proceedings of the 6th Annual New York University Institute of Philosophy. * "Distributive Justice." In Peter Laslett andW. G. Runciman

Walter Garrison Runciman, 3rd Viscount Runciman of Doxford, (10 November 193410 December 2020), usually known informally as Garry Runciman, was a British historical sociologist. A senior research fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge Runciman ...

, eds., ''Philosophy, Politics, and Society''. Third Series, pp. 58–82. London: Blackwell; New York: Barnes & Noble, 1967.

* "The Justification of Civil Disobedience." In Hugo Adam Bedau, ed., ''Civil Disobedience: Theory and Practice'', pp. 240–255. New York: Pegasus Books, 1969.

* "Justice as Reciprocity." In Samuel Gorovitz, ed., ''Utilitarianism: John Stuart Mill: With Critical Essays'', pp. 242–268. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971.

* "Author's Note." In Thomas Schwartz, ed., ''Freedom and Authority: An Introduction to Social and Political Philosophy'', p. 260. Encino & Belmont, California: Dickenson, 1973.

* "Distributive Justice." In Edmund S. Phelps, ed., ''Economic Justice: Selected Readings'', pp. 319–362. Penguin Modern Economics Readings. Harmondsworth & Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973.

* "Personal Communication, January 31, 1976." In Thomas Nagel's "The Justification of Equality." Critica (April 1978), 10 (28): 9n4.

* "The Basic Liberties and Their Priority." In Sterling M. McMurrin, ed., '' The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, III'' (1982), pp. 1–87. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

, 1982.

* "Social unity and primary goods" in

* "Themes in Kant's Moral Philosophy." In Eckhart Forster, ed., ''Kant's Transcendental Deductions: The Three Critiques and the Opus postumum'', pp. 81–113, 253–256. Stanford Series in Philosophy. Studies in Kant and German Idealism. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1989.

Reviews

* Review ofAxel Hägerström

Axel Anders Theodor Hägerström (6 September 1868, Vireda – 7 July 1939, Uppsala) was a Swedish philosopher.

Born in Vireda, Jönköping County, Sweden, he was the son of a Church of Sweden pastor. As student at Uppsala University, he gave ...

's ''Inquiries into the Nature of Law and Morals'' (C.D. Broad, tr.). ''Mind'' (July 1955), 64 (255):421–422.

* Review of Stephen Toulmin

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (; 25 March 1922 – 4 December 2009) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Toulmin devoted his works to the analysis of moral reasoning. Throughout his writings, he sought ...

's ''An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics'' (1950). ''Philosophical Review'' (October 1951), 60 (4): 572–580.

* Review of A. Vilhelm Lundstedt

Anders Vilhelm Lundstedt (11 September 1882 – 20 August 1955) was a Swedish jurist and legislator, particularly known as a proponent of Scandinavian Legal Realism, having been strongly influenced by his compatriot, the charismatic philosopher ...

's ''Legal Thinking Revised''. ''Cornell Law Quarterly'' (1959), 44: 169.

* Review of Raymond Klibansky

Raymond Klibansky, (October 15, 1905 – August 5, 2005) was a German-Canadian historian of philosophy and art.

Biography

Born in Paris, to Rosa Scheidt and Hermann Klibansky, he was educated at the University of Kiel, University of Hamburg ...

, ed., ''Philosophy in Mid-Century: A Survey''. ''Philosophical Review'' (January 1961), 70 (1): 131–132.

* Review of Richard B. Brandt, ed., ''Social Justice'' (1962). ''Philosophical Review'' (July 1965), 74(3): 406–409.

See also

*List of American philosophers

This is a list of American philosophers; of philosophers who are either from, or spent many productive years of their lives in the United States.

{, border="0" style="margin:auto;" class="toccolours"

, -

! {{MediaWiki:Toc

, -

, style="text-al ...

* List of liberal theorists

Individual contributors to classical liberalism and political liberalism are associated with philosophers of the Enlightenment. Liberalism as a specifically named ideology begins in the late 18th century as a movement towards self-government an ...

* Philosophy of economics

Philosophy and economics studies topics such as public economics, behavioural economics, rationality, justice, history of economic thought, rational choice, the appraisal of economic outcomes, institutions and processes, the status of highly i ...

* '' A Theory of Justice: The Musical!''

Notes

References

* Freeman, S. (2007) ''Rawls'' (Routledge, Abingdon) * Freeman, Samuel (2009) "Original Position" (The Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyOriginal Position

* * Rawls, J. (1993/1996/2005) '' Political Liberalism'' (Columbia University Press, New York) * * * Rogers, B. (27.09.02) "Obituary: John Rawls

Obituary: John Rawls

* Tampio, N. (2011) "A Defense of Political Constructivism" (Contemporary Political Theory

* Wenar, Leif (2008) "John Rawls" (The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

John Rawls

*

External links

* ttps://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-rawls-lexicon/56E9EFE4800DFA831929F3F563A9C016 Cambridge Rawls Lexicon

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on John Rawls by Henry S. Richardson

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Political Constructivisim by Michael Buckley

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on John Rawls by Leif Wenar

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Original Position by Fred D'Agostino

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Reflective Equilibrium by Norman Daniels

John Rawls

on

Google Scholar

Google Scholar is a freely accessible web search engine that indexes the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across an array of publishing formats and disciplines. Released in beta in November 2004, the Google Scholar index includes ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rawls, John

1921 births

2002 deaths

20th-century American male writers

20th-century American philosophers

20th-century atheists

20th-century essayists

21st-century American male writers

21st-century American philosophers

21st-century atheists

21st-century essayists

American atheists

American cultural critics

American ethicists

American logicians

American male essayists

American male non-fiction writers

American philosophy academics

American political philosophers

American social commentators

Analytic philosophers

Atheist philosophers

Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

Burials in Massachusetts

Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences fellows

Cornell University faculty

Corresponding Fellows of the British Academy

Cultural critics

Deontological ethics

Epistemologists

Former Anglicans

Harvard University faculty

Kantian philosophers

Kent School alumni

Massachusetts Institute of Technology faculty

Members of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters

Metaphysicians

Moral philosophers

National Humanities Medal recipients

Ontologists

Philosophers of culture

Philosophers of economics

Philosophers of education

Philosophers of ethics and morality

Philosophers of history

Philosophers of law

Philosophers of logic

Philosophers of mind

Philosophers of religion

Philosophers of social science

Philosophers of war

Philosophy academics

Philosophy writers

Political philosophers

Prejudice and discrimination

Princeton University alumni

Princeton University faculty

Progressivism in the United States

Rolf Schock Prize laureates

Social critics

Social justice

Social philosophers

Theorists on Western civilization

Writers about activism and social change

Writers from Baltimore

Writers from Boston

United States Army personnel of World War II

United States Army soldiers

Members of the American Philosophical Society

Fulbright alumni