John Randall (physicist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Turton Randall, (23 March 1905 – 16 June 1984) was an English

When the war began in 1939, Oliphant was approached by the

When the war began in 1939, Oliphant was approached by the

"Historical Notes on the Cavity Magnetron"

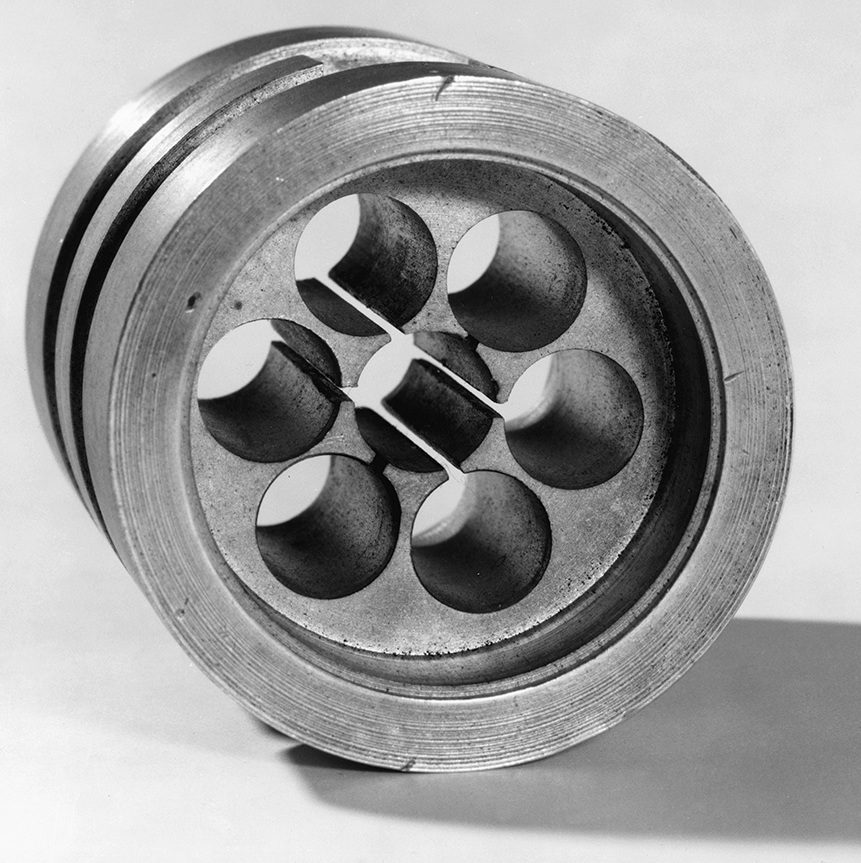

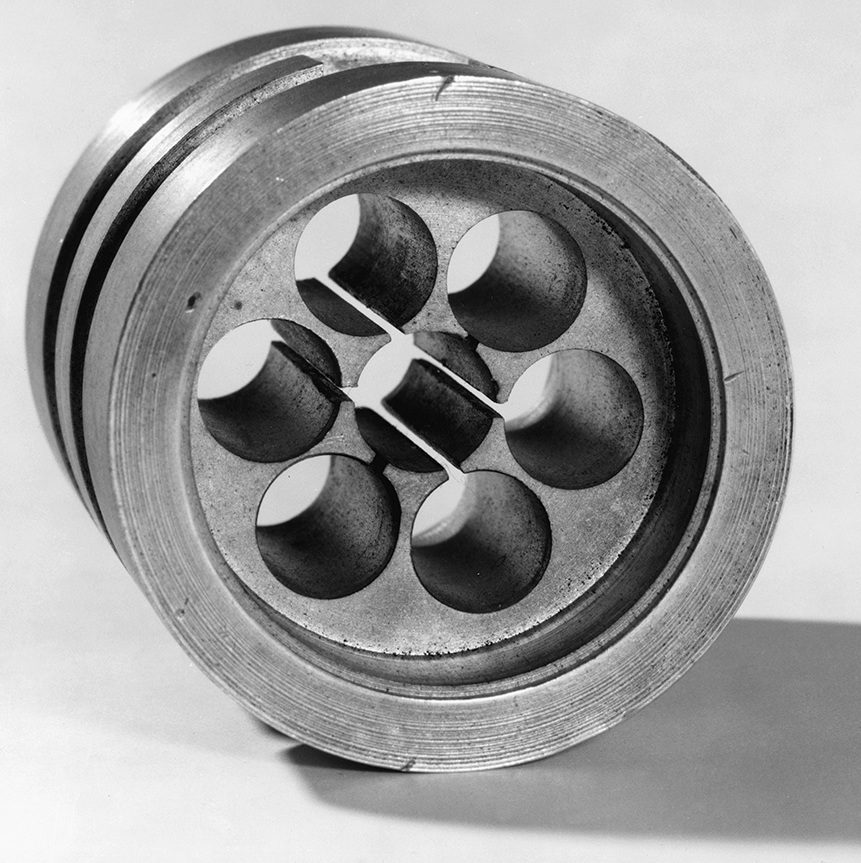

IEEE, July 1976, p. 724. The klystron effort soon plateaued with a device that could generate about 400 watts of microwave power, enough for testing purposes, but far short of the multi-kilowatt systems that would be required for a practical radar system. Randall and Boot, given no other projects to work on, began considering solutions to this problem in November 1939. The only other microwave device known at that time was the split-anode magnetron, a device capable of generating small amounts of power, but with low efficiency and generally lower output than the klystron. However, they noted that it had one enormous advantage over the klystron; the klystron's signal is encoded in a stream of electrons provided by an electron gun, and it was the current capability of the gun that defined how much power the device could ultimately handle. In contrast, the magnetron used a conventional hot filament cathode, a system that was widely used in radio systems producing hundreds of kilowatts. This seemed to offer a much more likely path to higher power. The problem with existing magnetrons was not power, but efficiency. In the klystron, a beam of electrons was passed through a metal disk known as a resonator. The mechanical layout of the copper resonator caused it to influence the electrons, speeding them up and slowing them down, releasing microwaves. This was reasonably efficient, and power was limited by the guns. In the case of the magnetron, the resonator was replaced by two metal plates held at opposite charges to cause the alternating acceleration, and the electrons were forced to travel between them using a magnet. There was no real limit to the number of electrons this could accelerate, but the microwave release process was extremely inefficient. The two then considered what would happen if the two metal plates of the magnetron were replaced by resonators, essentially combining the existing magnetron and klystron concepts. The magnet would cause the electrons to travel in a circle, as in the case of the magnetron, so they would pass by each of the resonators, generating microwaves much more efficiently than the plate concept. Recalling that

letter sent from Randall to Franklin

According to Raymond Gosling, the role of John Randall in the pursuit of the double helix cannot be overstated. Gosling felt so strongly on this subject that he wrote to ''The Times'' in 2013 during the sixtieth anniversary celebrations. Randall firmly believed that DNA held the genetic code and assembled a multi-disciplinary team to help prove it. It was Randall who pointed out that since DNA was largely carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, it was just the same as the atoms in the air in the camera. The result was a diffuse back-scattering of X-rays, which fogged the film, and so he instructed Gosling to displace all the air with hydrogen. Maurice Wilkins shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine with

* In 1938 Randall was awarded a

* In 1938 Randall was awarded a

The papers of Sir John Randall

held at th

Churchill Archives Centre

{{DEFAULTSORT:Randall, John Turton 1905 births 1984 deaths Physicists at the University of Cambridge English physicists Radar pioneers Alumni of the University of Manchester Academics of King's College London Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Academics of the University of Birmingham Knights Bachelor Microscopists People from Newton-le-Willows Academics of the University of St Andrews Academics of the University of Edinburgh

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and biophysicist

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. Bi ...

, credited with radical improvement of the cavity magnetron, an essential component of centimetric wavelength radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. It is also the key component of microwave oven

A microwave oven (commonly referred to as a microwave) is an electric oven that heats and cooks food by exposing it to electromagnetic radiation in the microwave frequency range. This induces polar molecules in the food to rotate and produce ...

s.

Randall collaborated with Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biograph ...

, and they produced a valve that could spit out pulses of microwave radio energy on a wavelength of 10 cm. On the significance of their invention, Professor of military history at the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

in British Columbia, David Zimmerman, states: "The magnetron remains the essential radio tube for shortwave radio signals of all types. It not only changed the course of the war by allowing us to develop airborne radar systems, it remains the key piece of technology that lies at the heart of your microwave oven today. The cavity magnetron's invention changed the world."

Randall also led the King's College, London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King G ...

team which worked on the structure of DNA. Randall's deputy, Professor Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding ...

, shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick a ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical stru ...

of the Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

for the determination of the structure of DNA. His other staff included Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, ...

, Raymond Gosling, Alex Stokes

Alexander Rawson Stokes (27 June 1919 – 6 February 2003) was a British physicist at Royal Holloway College, London and later at King's College London. He was most recognised as a co-author of the second of the three papers published sequent ...

and Herbert Wilson

Herbert Rees Wilson FRSE (20 March 1929 – 22 May 2008) was a physicist, who was one of the team who worked on the structure of DNA at King's College London, under the direction of Sir John Randall.

Biography Early life

He was born the son ...

, all involved in research on DNA.

Education and early life

John Randall was born on 23 March 1905 atNewton-le-Willows

Newton-le-Willows is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens, Merseyside, England. The population at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census was 22,114. Newton-le-Willows is on the eastern edge of St Helens, south of Wigan an ...

, Lancashire, the only son and the first of the three children of Sidney Randall, nurseryman and seedsman, and his wife, Hannah Cawley, daughter of John Turton, colliery manager in the area. He was educated at the grammar school at Ashton-in-Makerfield and at the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The university owns and operates majo ...

, where he was awarded a first-class honours degree in physics and a graduate prize in 1925, and a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast t ...

degree in 1926.

In 1928 he married Doris Duckworth.

Career and research

From 1926 to 1937 Randall was employed on research by theGeneral Electric Company

The General Electric Company (GEC) was a major British industrial conglomerate involved in consumer and defence electronics, communications, and engineering. The company was founded in 1886, was Britain's largest private employer with over 250 ...

at its Wembley

Wembley () is a large suburbIn British English, "suburb" often refers to the secondary urban centres of a city. Wembley is not a suburb in the American sense, i.e. a single-family residential area outside of the city itself. in north-west Londo ...

laboratories, where he took a leading part in developing luminescent powders for use in discharge lamps. He also took an active interest in the mechanisms of such luminescence

Luminescence is spontaneous emission of light by a substance not resulting from heat; or "cold light".

It is thus a form of cold-body radiation. It can be caused by chemical reactions, electrical energy, subatomic motions or stress on a crys ...

.

By 1937 he was recognised as the leading British worker in his field, and was awarded a Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

fellowship at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

, where he worked on the electron trap theory of phosphorescence

Phosphorescence is a type of photoluminescence related to fluorescence. When exposed to light (radiation) of a shorter wavelength, a phosphorescent substance will glow, absorbing the light and reemitting it at a longer wavelength. Unlike fluo ...

in Mark Oliphant's physics faculty with Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding ...

.

The Magnetron

When the war began in 1939, Oliphant was approached by the

When the war began in 1939, Oliphant was approached by the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

about the possibility of building a radio source that operated at microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

frequencies. Such a system would allow a radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

using it to see small objects like the periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

s of submerged U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s. The Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

radar researchers at Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor stands at a prominent position at the mouth of the River Deben close to the village of Bawdsey in Suffolk, England, about northeast of London.

Built in 1886, it was enlarged in 1895 as the principal residence of Sir William C ...

on the Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

coast had also expressed an interest in a 10 cm system, as this would greatly reduce the size of the transmission antennas, making them much easier to fit in the nose of aircraft, as opposed to being mounted on the wings and fuselage as in their current systems.

Oliphant began research using the klystron, a device introduced by Russell and Sigurd Varian between 1937 and 1939, and the only system known to efficiently generate microwaves. Klystrons of the era were very low-power devices, and Oliphant's efforts were primarily directed to greatly increasing their output. If this were successful, it created a secondary problem; the klystron was an amplifier only, so a low-power source signal was needed for it to amplify. Oliphant put Randall and Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biograph ...

on this issue of producing a microwave oscillator, asking them to explore miniature Barkhausen–Kurz tube

The Barkhausen–Kurz tube, also called the retarding-field tube, reflex triode, B–K oscillator, and Barkhausen oscillator was a high frequency vacuum tube electronic oscillator invented in 1920 by German physicists Heinrich Georg Barkhau ...

s for this role, a design already used for UHF

Ultra high frequency (UHF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies in the range between 300 megahertz (MHz) and 3 gigahertz (GHz), also known as the decimetre band as the wavelengths range from one meter to one tenth of a meter (on ...

systems. Their work quickly demonstrated that these offered no improvement in the microwave range.Randal and Boot"Historical Notes on the Cavity Magnetron"

IEEE, July 1976, p. 724. The klystron effort soon plateaued with a device that could generate about 400 watts of microwave power, enough for testing purposes, but far short of the multi-kilowatt systems that would be required for a practical radar system. Randall and Boot, given no other projects to work on, began considering solutions to this problem in November 1939. The only other microwave device known at that time was the split-anode magnetron, a device capable of generating small amounts of power, but with low efficiency and generally lower output than the klystron. However, they noted that it had one enormous advantage over the klystron; the klystron's signal is encoded in a stream of electrons provided by an electron gun, and it was the current capability of the gun that defined how much power the device could ultimately handle. In contrast, the magnetron used a conventional hot filament cathode, a system that was widely used in radio systems producing hundreds of kilowatts. This seemed to offer a much more likely path to higher power. The problem with existing magnetrons was not power, but efficiency. In the klystron, a beam of electrons was passed through a metal disk known as a resonator. The mechanical layout of the copper resonator caused it to influence the electrons, speeding them up and slowing them down, releasing microwaves. This was reasonably efficient, and power was limited by the guns. In the case of the magnetron, the resonator was replaced by two metal plates held at opposite charges to cause the alternating acceleration, and the electrons were forced to travel between them using a magnet. There was no real limit to the number of electrons this could accelerate, but the microwave release process was extremely inefficient. The two then considered what would happen if the two metal plates of the magnetron were replaced by resonators, essentially combining the existing magnetron and klystron concepts. The magnet would cause the electrons to travel in a circle, as in the case of the magnetron, so they would pass by each of the resonators, generating microwaves much more efficiently than the plate concept. Recalling that

Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz ( ; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. The uni ...

had used loops of wire as resonators, as opposed to the disk-shaped cavities of the klystron, it seemed possible that multiple resonators could be placed around the centre of the magnetron. More importantly, there was no real limit to the number or size of these loops. One could greatly improve the power of the system by extending the loops into cylinders, the power handling then being defined by the length of the tube. Efficiency could be improved by increasing the number of resonators, as each electron could thus interact with more resonators during its orbits. The only practical limits were based on the required frequency and desired physical size of the tube.

Developed using common lab equipment, the first magnetron consisted of a copper block with six holes drilled through it to produce the resonant loops, which was then placed in a bell jar

A bell jar is a glass jar, similar in shape to a bell (i.e. in its best-known form it is open at the bottom, while its top and sides together are a single piece), and can be manufactured from a variety of materials (ranging from glass to differe ...

and vacuum pumped, which was itself placed between the poles of the largest horseshoe magnet they could find. A test of their new cavity magnetron design in February 1940 produced 400 watts, and within a week it had been pushed over 1.000 watts. The design was then demonstrated to engineers from GEC, who were asked to try to improve it. GEC introduced a number of new industrial methods to better seal the tube and improve vacuum, and added a new oxide-coated cathode that allowed for much greater currents to be run through it. These boosted the power to 10 kW, about the same power as the conventional tube systems used in existing radar sets. The success of the magnetron revolutionised the development of radar, and almost all new radar sets from 1942 on used one.

In 1943 Randall left Oliphant's physical laboratory in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

to teach for a year in the Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

at Cambridge. In 1944 Randall was appointed professor of natural philosophy at University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

and began planning research in biophysics (with Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding ...

) on a small Admiralty grant.

King's College, London

In 1946, Randall was appointed Head of Physics Department at King's College in London. He then moved to the Wheatstone chair of physics atKing's College, London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King G ...

, where the Medical Research Council set up the Biophysics Research Unit with Randall as the director (now known as Randall Centre for Cell and Molecular Biophysics) at King's College. During his term as Director the experimental work leading to the discovery of the structure of DNA was made there by Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, ...

, Raymond Gosling, Maurice Wilkins, Alex Stokes and Herbert R. Wilson. He assigned Raymond Gosling as a PhD student to Franklin to work on DNA structure by X-ray diffraction.See thletter sent from Randall to Franklin

According to Raymond Gosling, the role of John Randall in the pursuit of the double helix cannot be overstated. Gosling felt so strongly on this subject that he wrote to ''The Times'' in 2013 during the sixtieth anniversary celebrations. Randall firmly believed that DNA held the genetic code and assembled a multi-disciplinary team to help prove it. It was Randall who pointed out that since DNA was largely carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, it was just the same as the atoms in the air in the camera. The result was a diffuse back-scattering of X-rays, which fogged the film, and so he instructed Gosling to displace all the air with hydrogen. Maurice Wilkins shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine with

James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick a ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical stru ...

; Rosalind Franklin had already died from cancer in 1958.

In addition to the X-Ray diffraction work the unit conducted a wide-ranging programme of research by physicists, biochemists, and biologists. The use of new types of light microscopes led to the important proposal in 1954 of the sliding filament mechanism for muscle contraction. Randall was also successful in integrating the teaching of biosciences at King's College.

In 1951 he set up a large multidisciplinary group working under his personal direction to study the structure and growth of the connective tissue protein collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whol ...

. Their contribution helped to elucidate the three-chain structure of the collagen molecule. Randall himself specialised in using the electron microscope

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

, first studying the fine structure of spermatozoa

A spermatozoon (; also spelled spermatozoön; ; ) is a motile sperm cell, or moving form of the haploid cell that is the male gamete. A spermatozoon joins an ovum to form a zygote. (A zygote is a single cell, with a complete set of chromos ...

and then concentrating on collagen. In 1958 he published a study of the structure of protozoa. He set up a new group to use the cilia of protozoa as a model system for the analysis of morphogenesis by correlating the structural and biochemical differences in mutants.

Personal life and later years

Randall married Doris, daughter of Josiah John Duckworth, a colliery surveyor, in 1928. They had one son, Christopher, born in 1935. In 1970 he moved to theUniversity of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

, where he formed a group which applied a range of new biophysical methods, such as coherent neutron diffraction studies of protein crystals in ionic solutions in heavy water, to study by neutron diffraction and scattering various biomolecular problems, such as the proton exchange of protein residues by deuterons.

Honours and awards

* In 1938 Randall was awarded a

* In 1938 Randall was awarded a Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

by the University of Manchester.

* In 1943 he was awarded (with Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biograph ...

) the Thomas Gray memorial prize of the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

for the invention of the cavity magnetron.

* In 1945 he was awarded the Duddell Medal and Prize

The Dennis Gabor Medal and Prize (previously the Duddell Medal and Prize until 2008) is a prize awarded biannually by the Institute of Physics for distinguished contributions to the application of physics in an industrial, commercial or busines ...

by the Physical Society of London and shared a payment from the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors for the magnetron invention.

* In 1946 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

(FRS) and was awarded their Hughes medal

The Hughes Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of London "in recognition of an original discovery in the physical sciences, particularly electricity and magnetism or their applications". Named after David E. Hughes, the medal is awarded wit ...

in the same year

* Further awards (with Boot) for the magnetron work were, in 1958, the John Price Wetherill Medal

The John Price Wetherill Medal was an award of the Franklin Institute. It was established with a bequest given by the family of John Price Wetherill (1844–1906) on April 3, 1917. On June 10, 1925, the Board of Managers voted to create a silve ...

of the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

of the state of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and, in 1959, the John Scott Medal award of the city of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

.

* In 1962 he was knighted, and in 1972 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE)

References

Further reading

*Chomet, S. (Ed.), ''D.N.A. Genesis of a Discovery'', 1994, Newman- Hemisphere Press, London. *Wilkins, Maurice, ''The Third Man of the Double Helix: The Autobiography of Maurice Wilkins.'' . *Ridley, Matt; "Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code (Eminent Lives)" first published in July 2006 in the US and then in the UK. September 2006, by HarperCollins Publishers . *Tait, Sylvia & James "A Quartet of Unlikely Discoveries" (Athena Press 2004) *Watson, James D., The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA, Atheneum, 1980, (first published in 1968).External links

The papers of Sir John Randall

held at th

Churchill Archives Centre

{{DEFAULTSORT:Randall, John Turton 1905 births 1984 deaths Physicists at the University of Cambridge English physicists Radar pioneers Alumni of the University of Manchester Academics of King's College London Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Academics of the University of Birmingham Knights Bachelor Microscopists People from Newton-le-Willows Academics of the University of St Andrews Academics of the University of Edinburgh