John Bright on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British

In 1840 he led a movement against the Rochdale church-rate, speaking from a tombstone in the churchyard, where it looks down on the town in the valley below. A daughter,

In 1840 he led a movement against the Rochdale church-rate, speaking from a tombstone in the churchyard, where it looks down on the town in the valley below. A daughter,

Mr Ewart's motion was defeated, but the movement of which Cobden and Bright were the leaders continued to spread. In the autumn the League resolved to raise £100,000; an appeal was made to the agricultural interest by great meetings in the farming counties, and in November ''

Mr Ewart's motion was defeated, but the movement of which Cobden and Bright were the leaders continued to spread. In the autumn the League resolved to raise £100,000; an appeal was made to the agricultural interest by great meetings in the farming counties, and in November ''

In 1857, Bright's unpopular opposition to the

In 1857, Bright's unpopular opposition to the

"A Working Class Hero"

''Birmingham Post'', p. 18 In 1866 he wrote an essay with the title "Speech on Reform". In this speech he demanded the enfranchisement of the working-class people because of their sheer number, and said that one should rejoice in open demonstrations rather than being confronted with "armed rebellion or secret conspiracy". In 1868, Bright entered the cabinet of Liberal Prime Minister Bright had much literary and social recognition in his later years. In 1880 he was elected Lord Rector of the

Bright had much literary and social recognition in his later years. In 1880 he was elected Lord Rector of the

On 8 April Gladstone introduced the Home Rule Bill into the House of Commons, where it passed the first reading without division. Bright did not enter the debates on the Bill and left London at the end of April to attend the funeral of his brother-in-law. He then returned to his home in Rochdale. On 13 May Gladstone sent him a letter, requesting he visit him in London. This date was also the anniversary of the death of Bright's wife's, so he replied that he felt the need to spend it at home. He further wrote:

On 8 April Gladstone introduced the Home Rule Bill into the House of Commons, where it passed the first reading without division. Bright did not enter the debates on the Bill and left London at the end of April to attend the funeral of his brother-in-law. He then returned to his home in Rochdale. On 13 May Gladstone sent him a letter, requesting he visit him in London. This date was also the anniversary of the death of Bright's wife's, so he replied that he felt the need to spend it at home. He further wrote:

In late 1888, Bright became seriously ill and he realised the end was near. On 27 November his son Albert wrote a letter to Gladstone in which he said his father "wishes me to write to you and tell you that "he could not forget your unvarying kindness to him and the many services you have rendered the country". He was very weak and did not seem able to say any more, and I saw the tears running down his cheeks". Gladstone replied that "I can assure you that he has been little absent of late from mine, that my feelings towards him are entirely unaltered by any of the occurrences of the last three years and that I have never felt separated from him in spirit. I heartily pray that he may enjoy the peace of God on this side the grave and on the other".Trevelyan, p. 463.

Bright received many letters and telegrams of sympathy from the Queen downwards. The Irish Nationalist MP Tim Healy wrote to Bright, wishing him a speedy recovery and "Your great services to our people can never be forgotten, for it was when Ireland had fewest friends that your voice was loudest on her side. I hope you may still be spared to raise it on her behalf according to your conceptions of what is best, for while we go on struggling for our own views, there can be nothing but regrets on our part of the sharpness of division in the past".

Bright died at his home One Ash on 27 March 1889 and was buried in the graveyard of the meeting-house of the

In late 1888, Bright became seriously ill and he realised the end was near. On 27 November his son Albert wrote a letter to Gladstone in which he said his father "wishes me to write to you and tell you that "he could not forget your unvarying kindness to him and the many services you have rendered the country". He was very weak and did not seem able to say any more, and I saw the tears running down his cheeks". Gladstone replied that "I can assure you that he has been little absent of late from mine, that my feelings towards him are entirely unaltered by any of the occurrences of the last three years and that I have never felt separated from him in spirit. I heartily pray that he may enjoy the peace of God on this side the grave and on the other".Trevelyan, p. 463.

Bright received many letters and telegrams of sympathy from the Queen downwards. The Irish Nationalist MP Tim Healy wrote to Bright, wishing him a speedy recovery and "Your great services to our people can never be forgotten, for it was when Ireland had fewest friends that your voice was loudest on her side. I hope you may still be spared to raise it on her behalf according to your conceptions of what is best, for while we go on struggling for our own views, there can be nothing but regrets on our part of the sharpness of division in the past".

Bright died at his home One Ash on 27 March 1889 and was buried in the graveyard of the meeting-house of the

/ref>

In 1868, students of the new

In 1868, students of the new

online

* * John Bright, ''Speeches on Questions of Public Policy'', ed. J.E.T. Rogers, 2 vols. (1869). * John Bright, ''Public Addresses'', ed. by J.E. Thorold Rogers, 8 vols (1879). * John Bright, ''Public Letters of the Right Hon. John Bright, MP.'', ed. by H.J. Leech (1885

online

* John Bright. ''Selected Speeches Of John Bright On Public Questions'' (1914

online

* John Bright, ''The Diaries of John Bright'', ed. R.A.J. Walling (1930

online

* G. B. Smith (eds.), ''The Life and Speeches of the Right Hon. John Bright, M.P.'', 2 vols. 8vo (1881).

''The Life of John Bright''

online

* Baylen, Joseph O. "John Bright as speaker and student of speaking." ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' (1955) 41#2 pp: 159–168. * Briggs, Asa. "Cobden and Bright" ''History Today'' (Aug 1957) 7#8 pp 496–503. * Briggs, Asa. “John Bright and the Creed of Reform," in Briggs, ''Victorian People'' (1955) pp. pp. 197–231

online

* Cash, Bill. ''John Bright: Statesman, Orator, Agitator'' (2011). * Fisher, Walter R. "John Bright: 'Hawker of holy things,'" ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' (1965) 51#2 pp: 157–163. * Gilbert, R. A. "John Bright's contribution to the Anti‐Corn Law League." ''Western Speech'' (1970) 34#1 pp: 16–20. * McCord, Norman. ''The Anti-Corn Law League: 1838–1846'' (Routledge, 2013) * Prentice, Archibald. ''History of the Anti-Corn Law League'' (Routledge, 2013) * ''Punch.'' ''The Rt. Hon. John Bright, M. P.: cartoons from the collection of "Mr. Punch"'' (1898), primary source

online

* Quinault, Roland. "John Bright and Joseph Chamberlain." ''Historical Journal'' (1985) 28#3 pp: 623–646. * Read, Donald. ''Cobden and Bright: A Victorian Political Partnership'' (1967); argues that Cobden was more influential * Robbins, Keith. ''John Bright'' (1979). * Smith, George Barnett. ''The Life and Speeches of the Right Honourable John Bright, MP'' (1881

online

* * Sturgis, James L. ''John Bright and the Empire'' (1969), focus on Bright's policy toward India & his attacks on the East India Compan

online

* Taylor, Miles. ''The Decline of British Radicalism, 1847–1860'' (1995). * Taylor, Miles. "Bright, John (1811–1889)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (2004); online edn, Sept 201

accessed 31 Aug 2014

* Westwood, Shannon Rebecca. "John Bright, Lancashire and the American Civil War". (Diss. Sheffield Hallam University, 2018

online

* * * *

Manchester Art Gallery Decoding Art, John Bright

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bright, John British classical liberals Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies UK MPs 1841–1847 UK MPs 1847–1852 UK MPs 1852–1857 UK MPs 1857–1859 UK MPs 1859–1865 UK MPs 1865–1868 UK MPs 1868–1874 UK MPs 1874–1880 UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 English Quakers People educated at Ackworth School People educated at Bootham School People from Rochdale Rectors of the University of Glasgow 1811 births 1889 deaths Liberal Unionist Party MPs for English constituencies Presidents of the Board of Trade Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Manchester Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for City of Durham Members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly

Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

* Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe an ...

and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

policies.

A Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn Laws. In partnership with Richard Cobden, he founded the Anti-Corn Law League

The Anti-Corn Law League was a successful political movement in Great Britain aimed at the abolition of the unpopular Corn Laws, which protected landowners’ interests by levying taxes on imported wheat, thus raising the price of bread at a tim ...

, aimed at abolishing the Corn Laws, which raised food prices

Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale. Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing ...

and protected landowners' interests by levying taxes on imported wheat. The Corn Laws were repealed in 1846. Bright also worked with Cobden in another free trade initiative, the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty of 1860, promoting closer interdependence between Great Britain and the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930s ...

. This campaign was conducted in collaboration with French economist Michel Chevalier

Michel Chevalier (; 13 January 1806 – 18 November 1879) was a French engineer, statesman, economist and free market liberal.

Biography

Born in Limoges, Haute-Vienne, Chevalier studied at the '' École Polytechnique'', obtaining an engineering ...

, and succeeded despite Parliament's endemic mistrust of the French.

Bright sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

from 1843 to 1889, promoting free trade, electoral reform and religious freedom. He was almost a lone voice in opposing the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

; he also opposed William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

's proposed Home Rule for Ireland

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

. He saw himself as a spokesman for the middle class and strongly opposed the privileges of the landed aristocracy. In terms of Ireland, he sought to end the political privileges of Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia ...

, disestablished the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

, and began land reform that would turn land over to the Catholic peasants. He coined the phrase " The mother of parliaments."

Early life

Bright was born at Greenbank,Rochdale

Rochdale ( ) is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, at the foothills of the South Pennines in the dale on the River Roch, northwest of Oldham and northeast of Manchester. It is the administrative centre of the Metropolitan Bor ...

, in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

, England—one of the early centres of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. His father, Jacob Bright, was a much-respected Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

, who had started a cotton mill

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Although some were driven b ...

at Rochdale in 1809. Jacob's father, Abraham, was a Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

, who, early in the 18th century, moved to Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, where his descendants remained. Jacob Bright was educated at the Ackworth School

Ackworth School is an independent day and boarding school located in the village of High Ackworth, near Pontefract, West Yorkshire, England. It is one of seven Quaker schools in England. The school (or more accurately its Head) is a member ...

of the Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

, and apprenticed to a fustian

Fustian is a variety of heavy cloth woven from cotton, chiefly prepared for menswear. It is also used figuratively to refer to pompous, inflated or pretentious writing or speech, from at least the time of Shakespeare. This literary use is b ...

manufacturer at New Mills

New Mills is a town in the Borough of High Peak, Derbyshire, England, south-east of Stockport and from Manchester at the confluence of the River Goyt and Sett. It is close to the border with Cheshire and above the Torrs, a deep gorge cut t ...

, Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

. John Bright was his son by his second wife, Martha Wood, daughter of a Quaker shopkeeper of Bolton-le-Moors

Bolton le Moors (also known as Bolton le Moors St Peter) was a large civil parish and ecclesiastical parish in hundred of Salford in the historic county of Lancashire, England. It was administered from St Peter's Church, Bolton in the township ...

. Educated at Ackworth School, she was a woman of great strength of character and refined taste. There were eleven children of this marriage, of whom John was the eldest surviving son. His younger brother was Jacob Bright

The Rt Hon. Jacob Bright (26 May 1821 – 7 November 1899) was a British Liberal politician serving as Mayor of Rochdale and later Member of Parliament for Manchester.

Background

Bright was born at Green Bank near Rochdale, Lancashire. He wa ...

, an MP and mayor. His sisters included Priscilla Bright McLaren

Priscilla Bright McLaren (8 September 1815 – 5 November 1906) was a British activist who served and linked the anti-slavery movement with the women's suffrage movement in the nineteenth century. She was a member of the Edinburgh Ladies' Emancip ...

(whose husband was Duncan McLaren

Duncan McLaren (12 January 1800 – 26 April 1886) was a Scottish Liberal Party politician and political writer. He served as a member of the burgh council of Edinburgh, then as Lord Provost, then as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Edinbu ...

MP) and Margaret Bright Lucas. John was a delicate child, and was sent as a day pupil to a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of " room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now exte ...

near his home, kept by William Littlewood. A year at the Ackworth School

Ackworth School is an independent day and boarding school located in the village of High Ackworth, near Pontefract, West Yorkshire, England. It is one of seven Quaker schools in England. The school (or more accurately its Head) is a member ...

, two years at Bootham School, York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, and a year and a half at Newton, near Clitheroe, completed his education. He learned, he himself said, but little Latin and Greek, but acquired a great love of English literature, which his mother fostered, and a love of outdoor pursuits. In his sixteenth year, he entered his father's mill, and in due time became a partner in the business.

In Rochdale, Jacob Bright was a leader of the opposition to a local church-rate. Rochdale was also prominent in the movement for parliamentary reform, by which the town successfully claimed to have a member allotted to it under the Reform Bill. John Bright took part in both campaigns. He was an ardent Nonconformist, proud to number among his ancestors John Gratton

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, a friend of George Fox

George Fox (July 1624 – 13 January 1691) was an English Dissenter, who was a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends. The son of a Leicestershire weaver, he lived in times of social upheaval and ...

, and one of the persecuted and imprisoned preachers of the Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

. His political interest was probably first kindled by the Preston

Preston is a place name, surname and given name that may refer to:

Places

England

*Preston, Lancashire, an urban settlement

**The City of Preston, Lancashire, a borough and non-metropolitan district which contains the settlement

**County Boro ...

election in 1830, in which Edward Stanley, after a long struggle, was defeated by Henry "Orator" Hunt.

But it was as a member of the Rochdale Juvenile Temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

Band that Bright first learned public speaking. These young men went out into the villages, borrowed a chair of a cottager, and spoke from it at open-air meetings. John Bright's first extempore speech was at a temperance meeting. Bright got his notes muddled, and broke down. The chairman gave out a temperance song, and during the singing told Bright to put his notes aside and say what came into his mind. Bright obeyed, began with much hesitancy, but found his tongue and made an excellent address, although sometimes he spoke with a confused syntax. Tales of these early years circulated through Britain and the United States late into his career, to the extent that students at institutions such as the young Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

regarded him as an exemplar for activities such as the Irving Literary Society.

On some early occasions, however, he committed his speech to memory. In 1832 he called on the Rev. John Aldis, an eminent Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

minister, to accompany him to a local Bible meeting. Mr Aldis described him as a slender, modest young gentleman, who surprised him by his intelligence and thoughtfulness, but who seemed nervous as they walked to the meeting together. At the meeting he made a stimulating speech, and on the way home asked for advice. Mr Aldis counselled him not to learn his speeches, but to write out and commit to memory certain passages and the peroration

Dispositio is the system used for the organization of arguments in the context of Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "organization" or "arrangement".

It is the second of five canons of classical rhetoric (the ...

. This "first lesson in public speaking", as Bright called it, was given in his twenty-first year, but he had not then contemplated a public career. He was a fairly prosperous man of business, very happy in his home, always ready to take part in the social, educational and political life of his native town. A founder of the Rochdale Literary and Philosophical Society, he took a leading part in its debates, and on returning from a holiday journey in the east, gave the society a lecture on his travels.

Cobden and the Corn Laws

He first met Richard Cobden in 1836 or 1837. Cobden was an alderman of the newly formedManchester Corporation

Manchester City Council is the local authority for Manchester, a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. Manchester is the sixth largest city in England by population. Its city council is composed of 96 councillors, three f ...

, and Bright went to ask him to speak at an education meeting in Rochdale. Cobden consented, and at the meeting was much struck by Bright's short speech, and urged him to speak against the Corn Laws. His first speech on the Corn Laws was made at Rochdale in 1838, and in the same year he joined the Manchester provisional committee which in 1839 founded the Anti-Corn Law League. He was still only the local public man, taking part in all public movements, especially in opposition to John Fielden

John Fielden (17 January 1784 – 29 May 1849) was a British industrialist and Radical Member of Parliament for Oldham (1832–1847).

He entered Parliament to support William Cobbett, whose election as fellow-MP for Oldham he helped to bring ...

's proposed factory legislation, and to the Rochdale church-rate. In 1839 he built the house which he called "One Ash", and married Elizabeth, daughter of Jonathan Priestman of Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

.

In November of the same year there was a dinner in Bolton

Bolton (, locally ) is a large town in Greater Manchester in North West England, formerly a part of Lancashire. A former mill town, Bolton has been a production centre for textiles since Flemish weavers settled in the area in the 14th ...

in honour of Abraham Paulton, who had just returned from an Anti-Corn Law tour in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. Among the speakers were Cobden and Bright, and the dinner is memorable as the first occasion on which the two future leaders appeared together on a Free Trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

platform. Bright is described by the historian of the League as "a young man then appearing for the first time in any meeting out of his own town, and giving evidence, by his energy and by his grasp of the subject, of his capacity soon to take a leading part in the great agitation."

In 1840 he led a movement against the Rochdale church-rate, speaking from a tombstone in the churchyard, where it looks down on the town in the valley below. A daughter,

In 1840 he led a movement against the Rochdale church-rate, speaking from a tombstone in the churchyard, where it looks down on the town in the valley below. A daughter, Helen

Helen may refer to:

People

* Helen of Troy, in Greek mythology, the most beautiful woman in the world

* Helen (actress) (born 1938), Indian actress

* Helen (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Helen, ...

, was born to him; but his young wife, after a long illness, died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

in September 1841. Three days after her death at Leamington, Cobden called to see him. "I was in the depths of grief", said Bright, when unveiling the statue of his friend at Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

in 1877, "I might almost say of despair, for the life and sunshine of my house had been extinguished." Cobden spoke some words of condolence, but "after a time he looked up and said, 'There are thousands of homes in England at this moment where wives, mothers and children are dying of hunger. Now, when the first paroxysm of your grief is past, I would advise you to come with me, and we will never rest till the Corn Laws are repealed.' I accepted his invitation", added Bright, "and from that time we never ceased to labour hard on behalf of the resolution which we had made."

Into Parliament: the Member for Durham

At thegeneral election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

in 1841 Cobden was returned for Stockport

Stockport is a town and borough in Greater Manchester, England, south-east of Manchester, south-west of Ashton-under-Lyne and north of Macclesfield. The River Goyt and Tame merge to create the River Mersey here.

Most of the town is withi ...

, Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

, and in 1843 Bright was the Free Trade candidate at a by-election at Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

. He was defeated, but his successful competitor was unseated on petition, and at the second contest Bright was returned. He was already known as Cobden's chief ally, and was received in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

with suspicion and hostility. In the Anti-Corn Law movement the two speakers complemented each other. Cobden had the calmness and confidence of the political philosopher, Bright had the passion and the fervour of the popular orator. Cobden did the reasoning, Bright supplied the declamation, but mingled argument with appeal. No orator of modern times rose more rapidly. He was not known beyond his own borough when Cobden called him to his side in 1841, and he entered parliament towards the end of the session of 1843 with a formidable reputation. He had been all over England and Scotland addressing vast meetings and, as a rule, carrying them with him; he had taken a leading part in a conference held by the Anti-Corn Law League in London had led deputations to the Duke of Sussex, to Sir James Graham, then home secretary, and to Lord Ripon

George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon, (24 October 1827 – 9 July 1909), styled Viscount Goderich from 1833 to 1859 and known as the Earl of Ripon in 1859 and as the Earl de Grey and Ripon from 1859 to 1871, was a British p ...

and Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-cons ...

, the secretary and under secretary of the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

; and he was universally recognised as the chief orator of the Free Trade movement. Wherever "John Bright of Rochdale" was announced to speak, vast crowds assembled. He had been so announced, for the last time, at the first great meeting in Drury Lane Theatre

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

on 15 March 1843; henceforth his name was enough. He took his seat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

as one of the members for Durham on 28 July 1843, and on 7 August delivered his maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

in support of a motion by Mr Ewart for reduction of import duties. He was there, he said, "not only as one of the representatives of the city of Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

, but also as one of the representatives of that benevolent organisation, the Anti-Corn Law League." A member who heard the speech described Bright as "about the middle size, rather firmly and squarely built, with a fair, clear complexion and an intelligent and pleasing expression of countenance. His voice is good, his enunciation distinct, and his delivery free from any unpleasant peculiarity or mannerism." He wore the usual Friend's coat, and was regarded with much interest and hostile curiosity on both sides of the House.

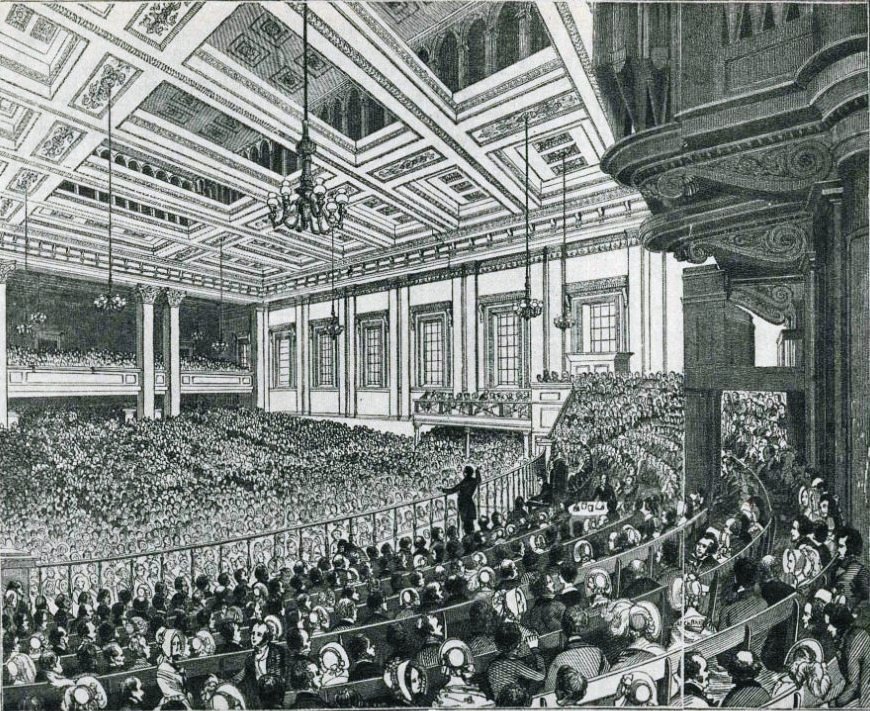

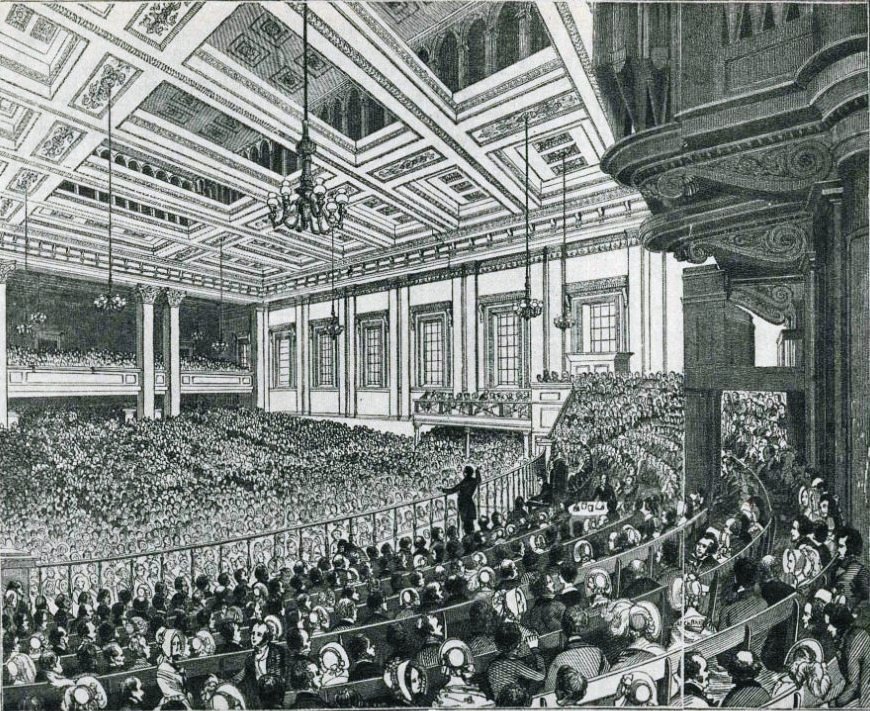

Mr Ewart's motion was defeated, but the movement of which Cobden and Bright were the leaders continued to spread. In the autumn the League resolved to raise £100,000; an appeal was made to the agricultural interest by great meetings in the farming counties, and in November ''

Mr Ewart's motion was defeated, but the movement of which Cobden and Bright were the leaders continued to spread. In the autumn the League resolved to raise £100,000; an appeal was made to the agricultural interest by great meetings in the farming counties, and in November ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' startled the country by declaring, in a leading article, "The League is a great fact. It would be foolish, nay, rash, to deny its importance." In London great meetings were held in Covent Garden Theatre

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Ope ...

, at which William Johnson Fox

William Johnson Fox (1 March 1786 – 3 June 1864) was an English Unitarian minister, politician, and political orator.

Early life

Fox was born at Uggeshall Farm, Wrentham, near Southwold, Suffolk on 1 March 1786. His parents were strict C ...

was the chief orator, but Bright and Cobden were the leaders of the movement. Bright publicly deprecated the popular tendency to regard Cobden and himself as the chief movers in the agitation, and Cobden told a Rochdale audience that he always stipulated that he should speak first, and Bright should follow. His "more stately genius", as John Morley

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, (24 December 1838 – 23 September 1923) was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

Initially, a journalist in the North of England and then editor of the newly Liberal-leani ...

calls it, was already making him the undisputed master of the feelings of his audiences. In the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

his progress was slower. Cobden's argumentative speeches were regarded more sympathetically than Bright's more rhetorical appeals, and in a debate on George Villiers's annual motion against the Corn Laws, Bright was heard with so much impatience that he was obliged to sit down.

In the next session (1845) he moved for an inquiry into the operation of the Game Laws. At a meeting of county members earlier in the day Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Excheque ...

, then Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, had advised them not to be led into discussion by a violent speech from the member for Durham, but to let the committee be granted without debate. Bright was not violent, and Cobden said that he did his work admirably, and won golden opinions from all men. The speech established his position in the House of Commons. In this session Bright and Cobden came into opposition, Cobden voting for the Maynooth

Maynooth (; ga, Maigh Nuad) is a university town in north County Kildare, Ireland. It is home to Maynooth University (part of the National University of Ireland and also known as the National University of Ireland, Maynooth) and St Patrick's ...

Grant and Bright against it. On only one other occasion—a vote for South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

—did they go into opposite lobbies, during twenty-five years of parliamentary life.

In the autumn of 1845 Bright retained Cobden in the public career to which Cobden had invited him four years before; Bright was in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

when a letter came from Cobden announcing his determination, forced on him by business difficulties, to retire from public work. Bright replied that if Cobden retired the mainspring of the League was gone. "I can in no degree take your place", he wrote. "As a second I can fight, but there are incapacities about me, of which I am fully conscious, which prevent my being more than second in such a work as we have laboured in." A few days later he set off for Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

, posting in that wettest of autumns through "the rain that rained away the Corn Laws", and on his arrival got his friends together, and raised the money which tided Cobden over the emergency. The crisis of the struggle had come. Peel's budget in 1845 was a first step towards Free Trade. The bad harvest and the potato blight drove him to the repeal of the Corn Laws, and at a meeting in Manchester on 2 July 1846 Cobden moved and Bright seconded a motion dissolving the league. A library of twelve hundred volumes was presented to Bright as a memorial of the struggle.

"Flog a dead horse"

According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a c ...

'', the first recorded use of the expression in its modern sense was by Bright in reference to the Reform Act of 1867, which called for more democratic representation in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. Trying to rouse Parliament from its apathy on the issue, he said in a speech, would be like trying to "flog a dead horse" to make it pull a load.

However, an earlier instance is attributed to Bright some thirteen years prior: speaking in the Commons on 28 March 1859 on a similar issue of parliamentary reform, Lord Elcho remarked that Bright had not been "satisfied with the results of his winter campaign" and that "a saying was attributed to him right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

that he adfound he was 'flogging a dead horse.'"

"England is the Mother of Parliaments"

Bright coined this famous phrase on 18 January 1865 in a speech atBirmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

supporting an expansion of the franchise. It has often been misquoted as a reference to the UK Parliament.

Marriage and Manchester

Bright married firstly, on 27 November 1839, Elizabeth Priestman of Newcastle, daughter of Jonathan Priestman and Rachel Bragg. They had one daughter, Helen Priestman Bright (b. 1840) but Elizabeth died on 10 September 1841. Helen Priestman Bright later married William Stephens Clark (1839–1925) ofStreet

A street is a public thoroughfare in a built environment. It is a public parcel of land adjoining buildings in an urban context, on which people may freely assemble, interact, and move about. A street can be as simple as a level patch of di ...

in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

.

Bright married secondly, in June 1847, Margaret Elizabeth Leatham, sister of Edward Aldam Leatham of Wakefield

Wakefield is a cathedral city in West Yorkshire, England located on the River Calder. The city had a population of 99,251 in the 2011 census.https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/ks101ew Census 2011 table KS101EW Usual resident population, ...

, by whom he had seven children including John Albert Bright

John Albert Bright (1848 – 11 November 1924) was an English industrialist and Liberal Unionist and Liberal politician.

Family and education

J A Bright was the eldest son of the Liberal reformer, orator and statesman, John Bright. His f ...

and William Leatham Bright

William Leatham Bright (12 August 1851 – 23 September 1910) was an English Liberal politician.

Bright was the son of John Bright, M.P., of One Ash, Rochdale and his wife Margaret Elizabeth Leatham. They employed Lydia Rous to teach their child ...

. Bright employed Lydia Rous in 1868 to teach his children. He compared her abilities as second only to the Queen.

In July 1847, Bright was elected uncontested for Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

, with Milner Gibson

Thomas Milner Gibson PC (3 September 1806 – 25 February 1884) was a British politician.

Background and education

Thomas Milner Gibson came of a Suffolk family, but was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, where his father, Thomas Milner Gibs ...

. In the new parliament, he opposed legislation restricting the hours of labour, and, as a Nonconformist, spoke against clerical control of national education. In 1848 he voted for Hume's household suffrage motion, and introduced a bill for the repeal of the Game Laws. When Lord John Russell brought forward his Ecclesiastical Titles Bill, Bright opposed it as "a little, paltry, miserable measure", and foretold its failure. In this parliament he spoke much on Irish questions. In a speech in favour of the government bill for a rate in aid (a tax on the prosperous parts of Ireland that would have paid for famine relief in the rest of that island) in 1849, he won loud cheers from both sides, and was complimented by Disraeli for having sustained the reputation of that assembly. From this time forward he had the ear of the House, and took effective part in the debates. He spoke against capital punishment, against church-rates, against flogging in the army, and against the Irish Established Church. He supported Cobden's motion for the reduction of public expenditure, and in and out of parliament pleaded for peace.

In the election of 1852 Bright was again returned for Manchester on the principles of free trade, electoral reform and religious freedom. But war was in the air, and the most impassioned speeches he ever delivered were addressed to this parliament in fruitless opposition to the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

. Neither the House nor the country would listen. "I went to the House on Monday", wrote Macaulay in March 1854, "and heard Bright say everything I thought." His most memorable speech, the greatest he ever made, was delivered on 23 February 1855. "The angel of death has been abroad throughout the land. You may almost hear the beating of his wings", he said, and concluded with an appeal that moved the House as it had never been moved within living memory.

In 1860, Bright won another victory with Cobden in a new Free Trade initiative, the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty, promoting closer interdependence between Britain and France. This campaign was conducted in collaboration with French economist Michel Chevalier

Michel Chevalier (; 13 January 1806 – 18 November 1879) was a French engineer, statesman, economist and free market liberal.

Biography

Born in Limoges, Haute-Vienne, Chevalier studied at the '' École Polytechnique'', obtaining an engineering ...

, and succeeded despite Parliament's endemic mistrust of the French.

MP for Birmingham: 1858–89

In 1857, Bright's unpopular opposition to the

In 1857, Bright's unpopular opposition to the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

led to his losing his seat as member for Manchester. Within a few months, he was elected unopposed as one of the two MPs for Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

in 1858. He would hold this position for over thirty years though he would later leave the Liberal Party on the issue of Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

in 1886.

On 27 October 1858, he launched his campaign for parliamentary reform at Birmingham Town Hall

Birmingham Town Hall is a concert hall and venue for popular assemblies opened in 1834 and situated in Victoria Square, Birmingham, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

The hall underwent a major renovation between 2002 and 2007. It no ...

.Bill Cash MP (27 October 2008"A Working Class Hero"

''Birmingham Post'', p. 18 In 1866 he wrote an essay with the title "Speech on Reform". In this speech he demanded the enfranchisement of the working-class people because of their sheer number, and said that one should rejoice in open demonstrations rather than being confronted with "armed rebellion or secret conspiracy". In 1868, Bright entered the cabinet of Liberal Prime Minister

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

as President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th century, that evolved gradually into a government ...

, but resigned in 1870 due to ill health. He served twice again in Gladstone cabinets as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1873–74, 1880–82). In 1882, Gladstone ordered the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

to bombard Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

to recover the debts owed by the Egyptians to British investors. Bright scornfully dismissed it as "a jobbers' war" on behalf of a privileged class of capitalists, and resigned from the Gladstone cabinet."

For deeply personal reasons, Bright was closely associated with the North Wales

North Wales ( cy, Gogledd Cymru) is a regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders Mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, ...

tourist resort of Llandudno

Llandudno (, ) is a seaside resort, town and community in Conwy County Borough, Wales, located on the Creuddyn peninsula, which protrudes into the Irish Sea. In the 2011 UK census, the community – which includes Gogarth, Penrhyn Bay, Craig ...

. In 1864, he holidayed there with his wife and five-year-old son. As they passed through the graveyard, the boy said, "Mamma, when I am dead, I want to be buried here." A week later, he had died of scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by '' Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects chi ...

, and his wish was granted. Bright returned to Llandudno at least once a year until his own death. He is still commemorated in Llandudno where the principal secondary school was named after him, and a new school, Ysgol John Bright was built in 2004.

Bright had much literary and social recognition in his later years. In 1880 he was elected Lord Rector of the

Bright had much literary and social recognition in his later years. In 1880 he was elected Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, although R. W. Dale wrote of his rectorial address: "It was not the old Bright." He was given an honorary degree of the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

in 1886. He delivered the opening address for the Birmingham Central Library in 1882, and in 1888 the city erected a statue of him. The marble statue, by Albert Joy, was in store until it was recently restored to a prominent position in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Both John Bright Street, close to the Alexandra Theatre in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, and Morse's Creek in Australia, now known as Bright, Victoria, were renamed in his honour.

Opposition to Home Rule

When in the wake of theGreat Irish Famine

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a h ...

, an all-Ireland Tenant Right League was formed, Bright expressed sympathy and support for reform of Irish land tenure. In 1850 he advised the House of Common to "resolutely legislate" on the question. Key for Bright was that "Instead of the enant-rightagitation being confined, as heretofore to the Roman Catholics and their clergy, Protestant and Dissenting clergymen seem to be amalgamated with Roman Catholics at present; indeed, there seems an amalgamation of all sects on this question." But once the sectarian division over Ireland's future within the United Kingdom reasserted itself, Bright's position hardened. Supporting Protestant Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

, he would have no truck with what he described as the "disloyal Ireland".

In 1886 when Gladstone proposed Home Rule for Ireland and another Irish Land Act, Bright opposed it, along with Joseph Chamberlain and Lord Hartington. He regarded Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of t ...

's Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nation ...

as "the rebel party". Bright was repeatedly contacted by Gladstone, Chamberlain and Hartington to solicit his support. He was widely regarded as a force to be reckoned with and his political influence was considerably out of proportion to his activity. In March 1886 Bright went to London, and on 10 March met Hartington, having an hour's talk with him on Ireland. On 12 March Bright met Gladstone for dinner, writing that Gladstone's "chief object is to settle the Land question which I rather think ought ''now'' ought be considered as settled. On the question of a Parliament in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, he wishes to get rid of Irish representation at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, in which I entirely agree with him if it be possible". On 17 March he met Chamberlain and thought "his view is in the main correct and that it is not wise in him to support the intended measures". On 20 March he had a two-hour-long meeting with Gladstone:

He gave me a long memorandum, historical in character, on the past Irish story, which seemed to be somewhat one-sided, leaving out of view the important minority and the views and feelings of the Protestant and loyal portion of the people. He explained much of his policy as to a Dublin Parliament, and as to Land purchase. I objected to the Land policy as unnecessary—the Act of 1881 had done all that was reasonable for the tenants—why adopt the policy of the rebel party, and get rid of landholders, and thus evict the English garrison as the rebels call them? I denied the value of the security for repayment. Mr G. argued that his finance arrangements would be better than present system of purchase, and that we were bound in honour to succour the landlords, which I contested. Why not go to the help of other interests in Belfast and Dublin? As to Dublin Parliament, I argued that he was making a surrender all along the line—a Dublin Parliament would work with constant friction, and would press against any barrier he might create to keep up the unity of the three Kingdoms. What of a volunteer force, and what of import duties and protection as against British goods? ... I thought he placed far too much confidence in the leaders of the rebel party. I could place none in them, and the general feeling was and is that any terms made with them would not be kept, and that through them I could not hope for reconciliation with discontented and disloyal Ireland.Trevelyan, pp. 447–448.

On 8 April Gladstone introduced the Home Rule Bill into the House of Commons, where it passed the first reading without division. Bright did not enter the debates on the Bill and left London at the end of April to attend the funeral of his brother-in-law. He then returned to his home in Rochdale. On 13 May Gladstone sent him a letter, requesting he visit him in London. This date was also the anniversary of the death of Bright's wife's, so he replied that he felt the need to spend it at home. He further wrote:

On 8 April Gladstone introduced the Home Rule Bill into the House of Commons, where it passed the first reading without division. Bright did not enter the debates on the Bill and left London at the end of April to attend the funeral of his brother-in-law. He then returned to his home in Rochdale. On 13 May Gladstone sent him a letter, requesting he visit him in London. This date was also the anniversary of the death of Bright's wife's, so he replied that he felt the need to spend it at home. He further wrote:

I cannot consent to a measure which is so offensive to the whole Protestant population of Ireland, and to the whole sentiment of the province of Ulster so far as its loyal and Protestant people are concerned. I cannot agree to exclude them from the protection of the Imperial Parliament. I would do much to clear the rebel party from Westminster, and do not sympathise with those who wish to retain them—but admit there is much force in the arguments on this point which are opposed to my views upon it. ... As to the Land Bill, if it comes to a second reading, I fear I must vote against it. It may be that my hostility to the rebel party, looking at their conduct since your Government was formed six years ago, disables me from taking an impartial view of this great question. If I could believe them honorable and truthful men, I could yield much—but I suspect that your policy of surrender to them will only place more power in their hands to war with greater effect against the unity of the 3 Kingdoms with no increase of good to the Irish people. ... Parliament is not ready for it, and the intelligence of the country is not ready for it. If it be possible, I should wish that no Division should be taken upon the Bill.On 14 May Bright came to London and wrote to the Liberal MP Samuel Whitbread that Gladstone should withdraw the Home Rule Bill and that he should not dissolve Parliament if the Bill were put forward for a second reading and were defeated in a vote: "... it would only make the Liberal split the more serious, and make it beyond the power of healing. He would be responsible for the greatest wound the Party has received since it was a Party ... If the Bill were now withdrawn, the whole present difficulty in our Party would be gone". He also predicted the Conservatives would gain in strength if an election were called. At the famous meeting at the Committee Room 15, Liberal MPs who were not outright opponents of the idea of Irish self-government but who disapproved of the Bill, met to decide upon a course of action. Among the attendees were Chamberlain, and Bright wrote to on 31 May:

My present intention is to vote against the Second Reading, not having spoken in the debate. I am not willing to have my view of the bill or Bills in doubt. But I am not willing to take the responsibility of advising others as to their course. If they can content themselves with abstaining from the division, I shall be glad. they will render a greater service by preventing the threatened dissolution than by compelling it ... a small majority for the Bill may be almost as good as its defeat and may save the country from the heavy sacrifice of a general election. I wish I could join you, but I cannot now change the path I have taken from the beginning of this unhappy discussion ...''P.S.''—If you think it of any use you may read this note to your friends.Chamberlain read aloud this letter to the meeting and he later wrote that Bright's "announcement that he intended to vote against the Second Reading undoubtedly affected the decision" and that the meeting ended by unanimously agreeing to vote against the Bill. Bright wrote to Chamberlain on 1 June that he was surprised at the meeting's decision because his letter "was intended to make it more easy for and your friends to abstain from voting in the coming division". On 7 June the Home Rule Bill was defeated by 341 votes to 311, Bright voting against it. Gladstone dissolved Parliament. During the subsequent

general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

campaign, Bright delivered only one speech, to his constituents on 1 July, in which he opposed Irish Home Rule. He exhorted his countrymen to put the Union above the Liberal Party. This speech was generally viewed by the Gladstonian Liberals as having a decisive effect on their defeat. John Morley wrote that "The heaviest and most telling attack came from Mr. Bright, who had up to now in public been studiously silent. Every word, as they said of Daniel Webster, seemed to weigh a pound. His arguments were mainly those of his letter already given, but they were delivered with a gravity and force that told powerfully upon the large phalanx of doubters all over the kingdom". The chairman of the National Liberal Federation, Sir B. Walter Foster, complained that Bright "probably did more harm in this election to his own party than any other single individual". The Liberal journalist P. W. Clayden was a candidate for Islington North and when canvassing leading dissident Liberals, he would take with him a copy of the Home Rule Bill:

Going through the Bill with some of them clause by clause, I was able to answer all their objections, and in many cases to get their promise of support. Mr Bright's speech, however, at once undid all my work. In the whole country it probably kept many thousands of Liberal voters from going to the polls, and did more than all the other influences put together to produce the Liberal abstention which gave the Coalition its decisive victory.Bright was re-elected by his Birmingham constituents and it turned out to be his last Parliament. He sat as a

Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a politic ...

allied to the Conservative Party who had formed a government after the election. Bright participated little in this Parliament, however his actions could still decide events. Lord George Hamilton recorded that when the government introduced the Criminal Law Amendment (Ireland) Bill in March 1887, which increased the authorities' coercive powers, the Liberal Party opposed it. Bright did not speak in the debate but Hamilton notes that great importance was attached to how Bright would vote: "If he abstained from voting or voted against the Government, the Unionist coalition would have been practically broken up. On the other hand if he, in order to avert Home Rule, voted for a procedure which was so contrary to his previous professions, the Coalition would receive a fresh source of strength and cohesion. When the Division Bell rang, Mr. Bright, who was sitting close by Gladstone, without a moment's hesitation walked straight into the Government's lobby".

From this point until his death, Bright did not meet Gladstone, despite their long political relationship together.

MLA for Kennedy, Queensland: 1869–70

The Colony ofQueensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

achieved separation from New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

in 1859 with Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

in the south-east corner chosen as its capital. By the 1860s, the perceived dominance of southern Queensland created a strong separatist movement in Central Queensland and North Queensland

North Queensland or the Northern Region is the northern part of the Australian state of Queensland that lies just south of Far North Queensland. Queensland is a massive state, larger than many countries, and its tropical northern part has been ...

, seeking to establish yet another independent colony. In the 1867 Queensland colonial election

Elections were held in the Australian state of Queensland between 18 June 1867 and 19 July 1867 to elect the members of the state's Legislative Assembly.

Key dates

Due to problems of distance and communications, it was not possible to hold the ...

, some separatists decided to nominate John Bright as the candidate for the electoral district of Rockhampton in Central Queensland, arguing that representation in the Queensland Parliament had been ineffective, so they would seek a representative within the British Parliament. However, he polled only 10 votes and was not elected.

Subsequently, on 11 June 1869, Thomas Henry Fitzgerald, member for the electoral district of Kennedy in North Queensland, resigned, triggering a by-election. John Bright was again nominated as part of the separatist protest and on this occasion won the resulting by-election on 10 July 1869. When nominating him, one separatist declared:

Let us elect a man of some weight at home, who will take our case before the Queen and try for redress. There is no man more eminently qualified for this purpose than the Honourable John Bright—a favourite with the Queen, a favourite with the nation—the representative of trade, commerce, and manufactures in the Government and the champion of liberty, and yet a loyal subject. If we can enlist his sympathies, we are right. I believe he is the man who will break the iron rod of the South and set us free; for he has already fought for the liberty of the subject, and I cannot believe he will turn a deaf ear to our manifold sorrows.In January 1870, the separatists sent a petition to

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

requesting that North Queensland be made a separate colony to be called "Albertsland" (after the Queen's late husband Albert, Prince Consort

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel; 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the consort of Queen Victoria from their marriage on 10 February 1840 until his death in 1861.

Albert was born in the Saxon du ...

). As Bright never visited Queensland or took his seat in the Queensland Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland established under the Constitution of Queensland. Elections are held every four years and are done by full preferential voting. The Assembly h ...

, his failure to attend parliament eventually resulted in his seat being declared vacant on 8 July 1870. North Queensland did not achieve separation and remained part of the Colony of Queensland (now the State of Queensland).

It is not known what role John Bright had in these Queensland political activities, or indeed if he was even aware of them. However, it was claimed in 1867 that Bright was an "intimate personal friend" of the then Governor of Queensland

The governor of Queensland is the representative in the state of Queensland of the monarch of Australia. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governor performs constitutional and ceremonial func ...

George Bowen

Sir George Ferguson Bowen (; 2 November 1821 – 21 February 1899), was an Irish author and colonial administrator whose appointments included postings to the Ionian Islands, Queensland, New Zealand, Victoria, Mauritius and Hong Kong.R. B. ...

.

Death

In late 1888, Bright became seriously ill and he realised the end was near. On 27 November his son Albert wrote a letter to Gladstone in which he said his father "wishes me to write to you and tell you that "he could not forget your unvarying kindness to him and the many services you have rendered the country". He was very weak and did not seem able to say any more, and I saw the tears running down his cheeks". Gladstone replied that "I can assure you that he has been little absent of late from mine, that my feelings towards him are entirely unaltered by any of the occurrences of the last three years and that I have never felt separated from him in spirit. I heartily pray that he may enjoy the peace of God on this side the grave and on the other".Trevelyan, p. 463.

Bright received many letters and telegrams of sympathy from the Queen downwards. The Irish Nationalist MP Tim Healy wrote to Bright, wishing him a speedy recovery and "Your great services to our people can never be forgotten, for it was when Ireland had fewest friends that your voice was loudest on her side. I hope you may still be spared to raise it on her behalf according to your conceptions of what is best, for while we go on struggling for our own views, there can be nothing but regrets on our part of the sharpness of division in the past".

Bright died at his home One Ash on 27 March 1889 and was buried in the graveyard of the meeting-house of the

In late 1888, Bright became seriously ill and he realised the end was near. On 27 November his son Albert wrote a letter to Gladstone in which he said his father "wishes me to write to you and tell you that "he could not forget your unvarying kindness to him and the many services you have rendered the country". He was very weak and did not seem able to say any more, and I saw the tears running down his cheeks". Gladstone replied that "I can assure you that he has been little absent of late from mine, that my feelings towards him are entirely unaltered by any of the occurrences of the last three years and that I have never felt separated from him in spirit. I heartily pray that he may enjoy the peace of God on this side the grave and on the other".Trevelyan, p. 463.

Bright received many letters and telegrams of sympathy from the Queen downwards. The Irish Nationalist MP Tim Healy wrote to Bright, wishing him a speedy recovery and "Your great services to our people can never be forgotten, for it was when Ireland had fewest friends that your voice was loudest on her side. I hope you may still be spared to raise it on her behalf according to your conceptions of what is best, for while we go on struggling for our own views, there can be nothing but regrets on our part of the sharpness of division in the past".

Bright died at his home One Ash on 27 March 1889 and was buried in the graveyard of the meeting-house of the Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

in Rochdale.

The Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury paid tribute to him in the House of Lords the day after his death, and it sums up his character as a public man:The Late Duke of Buckingham and Chandos – The Late Mr. John Bright – Observations. HL Deb 28 March 1889 vol 334 cc993-7/ref>

In the first place, he was the greatest master of English oratory that this generation has produced, or I may perhaps say several generations back. I have met men who have heard Pitt and Fox, and in whose judgment their eloquence at its best was inferior to the finest efforts of John Bright. At a time when much speaking has depressed and almost exterminated eloquence, he maintained robust and intact that powerful and vigorous style of English which gave fitting expression to the burning and noble thoughts he desired to express. Another characteristic for which I think he will be famous is the singular rectitude of his motives, the singular straightness of his career. He was a keen disputant, a keen combatant; like many eager men, he had little tolerance of opposition. But his action was never guided for a single moment by any consideration of personal or party selfishness. He was inspired by nothing but the purest patriotism and benevolence from the first beginning of his public career to the hour of its close.

Memorials

In 1868, students of the new

In 1868, students of the new Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

debated whether to call its first literary society, "The John Bright Brotherhood" or the " Irving Literary Society". New York State's recently deceased native son received the honours, but not before Bright was inducted as its first honorary member.

The library at Bootham School is named in his honour.

In 1928, the Brooks-Bryce Foundation donated significant funds to the Princeton University Library

Princeton University Library is the main library system of Princeton University. With holdings of more than 7 million books, 6 million microforms, and 48,000 linear feet of manuscripts, it is among the largest libraries in the world by number of ...

for a collection of materials on the life and times of John Bright, in honour of the statesman. The Foundation also donated funds for an outdoor pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, acces ...