Jeremy Bentham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February 1747/8 O.S. N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern

Bentham was born on 4 February 1747/8 O.S. N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.in Houndsditch, London, to attorney Jeremiah Bentham and Alicia Woodward, widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer (occupation), mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover. His wealthy family were supporters of the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study

Bentham was born on 4 February 1747/8 O.S. N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.in Houndsditch, London, to attorney Jeremiah Bentham and Alicia Woodward, widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer (occupation), mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover. His wealthy family were supporters of the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study

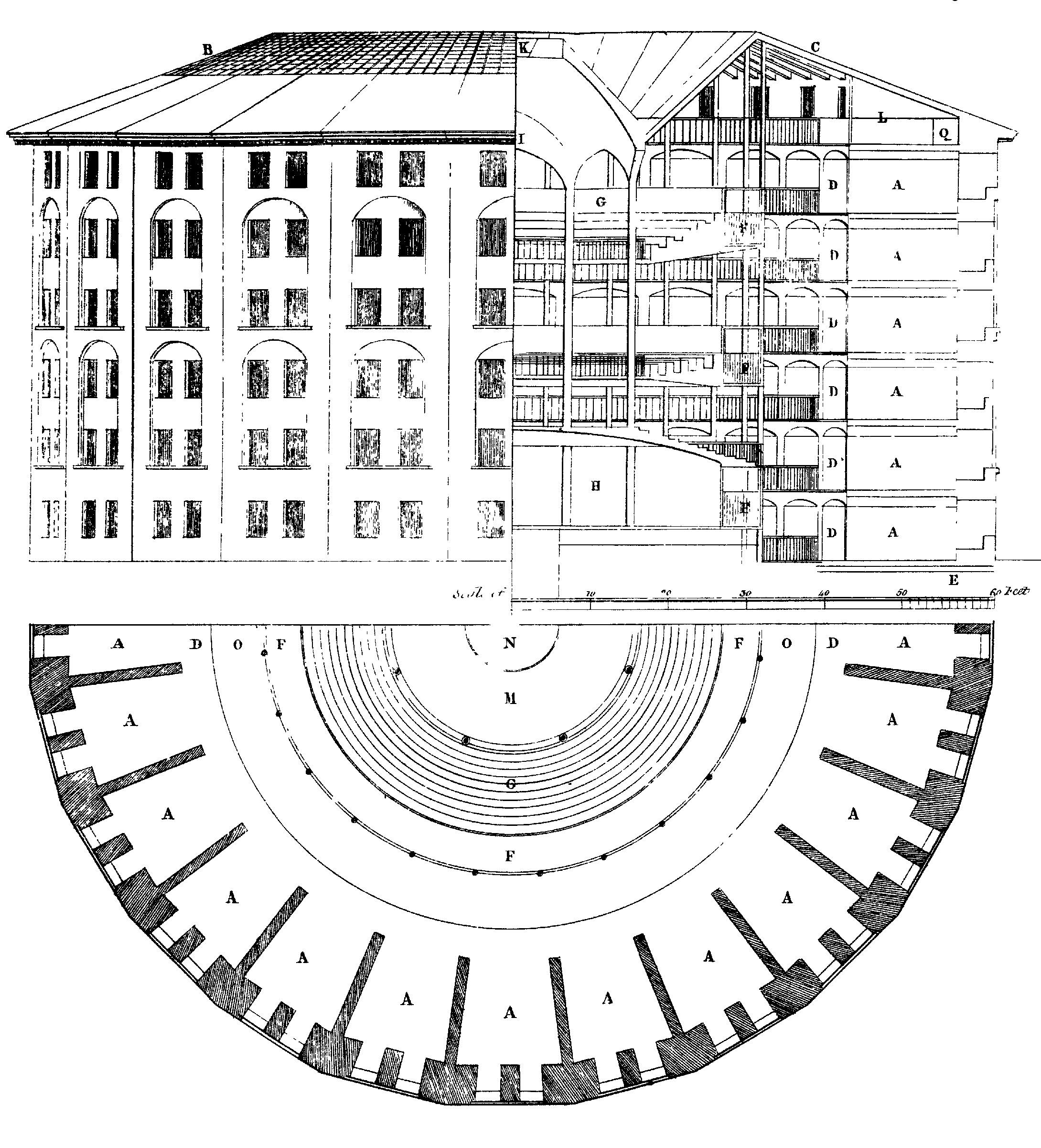

On his return to England from Russia, Bentham had commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley. In 1791, he published the material he had written as a book, although he continued to refine his proposals for many years to come. He had by now decided that he wanted to see the prison built: when finished, it would be managed by himself as contractor-governor, with the assistance of Samuel. After unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and revolutionary France, he started trying to persuade the prime minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a panopticon. He was eventually successful in winning over Pitt and his advisors, and in 1794 was paid £2,000 for preliminary work on the project.

The intended site was one that had been authorised, under the Appropriation Act 1799 ( 39 Geo. 3. c. 114) for the earlier penitentiary, at Battersea Rise; but the new proposals ran into technical legal problems and objections from the local landowner, the Earl Spencer. Other sites were considered, including one at Hanging Wood, near Woolwich, but all proved unsatisfactory. Eventually Bentham turned to a site at Tothill Fields, near

On his return to England from Russia, Bentham had commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley. In 1791, he published the material he had written as a book, although he continued to refine his proposals for many years to come. He had by now decided that he wanted to see the prison built: when finished, it would be managed by himself as contractor-governor, with the assistance of Samuel. After unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and revolutionary France, he started trying to persuade the prime minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a panopticon. He was eventually successful in winning over Pitt and his advisors, and in 1794 was paid £2,000 for preliminary work on the project.

The intended site was one that had been authorised, under the Appropriation Act 1799 ( 39 Geo. 3. c. 114) for the earlier penitentiary, at Battersea Rise; but the new proposals ran into technical legal problems and objections from the local landowner, the Earl Spencer. Other sites were considered, including one at Hanging Wood, near Woolwich, but all proved unsatisfactory. Eventually Bentham turned to a site at Tothill Fields, near

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the ageing

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the ageing

Of the Limits of the Penal Branch of Jurisprudence

. pp. 307–335 in '' An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation''. London: T. Payne and Sons. In 1780, alluding to the limited degree of legal protection afforded to

Bentham was the first person to be an aggressive advocate for the codification of ''all'' of the

Bentham was the first person to be an aggressive advocate for the codification of ''all'' of the

Bentham influenced economists such as Milton Friedman and Henry Hazlitt.

In their youth,

Bentham influenced economists such as Milton Friedman and Henry Hazlitt.

In their youth,

utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

.

Bentham defined as the "fundamental axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

" of his philosophy the principle that "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong." He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

, freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and (in an unpublished essay) the decriminalizing of homosexual acts. He called for the abolition of slavery, capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, and physical punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or paddling. When ...

, including that of children. He has also become known as an early advocate of animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all Animal consciousness, sentient animals have Moral patienthood, moral worth independent of their Utilitarianism, utility to humans, and that their most basic interests—such as ...

. Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

and natural rights (both of which are considered "divine" or "God-given" in origin), calling them "nonsense upon stilts". However, he viewed the Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

as important, citing it to argue that the treatment of convicts in Australia was unlawful. Bentham was also a sharp critic of legal fiction

A legal fiction is a construct used in the law where a thing is taken to be true, which is not in fact true, in order to achieve an outcome. Legal fictions can be employed by the courts or found in legislation.

Legal fictions are different from ...

s.

Bentham's students included his secretary and collaborator James Mill, the latter's son, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

, the legal philosopher John Austin and American writer and activist John Neal. He "had considerable influence on the reform of prisons, schools, poor laws, law courts, and Parliament itself."

On his death in 1832, Bentham left instructions for his body to be first dissected and then to be permanently preserved as an " auto-icon" (or self-image), which would be his memorial. This was done, and the auto-icon is now on public display in the entrance of the Student Centre at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

(UCL). Because of his arguments in favour of the general availability of education, he has been described as the "spiritual founder" of UCL. However, he played only a limited part in its foundation.

Biography

Early life

Bentham was born on 4 February 1747/8 O.S. N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.in Houndsditch, London, to attorney Jeremiah Bentham and Alicia Woodward, widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer (occupation), mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover. His wealthy family were supporters of the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study

Bentham was born on 4 February 1747/8 O.S. N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.in Houndsditch, London, to attorney Jeremiah Bentham and Alicia Woodward, widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer (occupation), mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover. His wealthy family were supporters of the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

at the age of three. He learnt to play the violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

, and at the age of seven Bentham would perform sonata

In music a sonata (; pl. ''sonate'') literally means a piece ''played'' as opposed to a cantata (Latin and Italian ''cantare'', "to sing"), a piece ''sung''. The term evolved through the history of music, designating a variety of forms until th ...

s by Handel during dinner parties. He had one surviving sibling, Samuel Bentham

Brigadier General Sir Samuel Bentham (11 January 1757 – 31 May 1831) was an England, English mechanical engineering, mechanical engineer and naval architect credited with numerous innovations, particularly related to naval architecture, incl ...

, with whom he was close.

He attended Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

; in 1760, at age 12, his father sent him to The Queen's College, Oxford, where he completed his bachelor's degree in 1764, receiving the title of MA in 1767. He trained as a lawyer and, though he never practised, was called to the bar in 1769. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of English law, which he termed the "Demon of Chicane". When the American colonies published their Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the British government did not issue any official response but instead secretly commissioned London lawyer and pamphleteer John Lind to publish a rebuttal. His 130-page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled "Short Review of the Declaration" written by Bentham, a friend of Lind, which attacked and mocked the Americans' political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

.

Abortive prison project and the Panopticon

In 1786 and 1787, Bentham travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modernBelarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

) to visit his brother, Samuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

, who was engaged in managing various industrial and other projects for Prince Potemkin. It was Samuel (as Jeremy later repeatedly acknowledged) who conceived the basic idea of a circular building at the hub of a larger compound as a means of allowing a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large and unskilled workforce.

Bentham began to develop this model, particularly as applicable to prisons, and outlined his ideas in a series of letters sent home to his father in England. He supplemented the supervisory principle with the idea of ''contract management''; that is, an administration by contract as opposed to trust, where the director would have a pecuniary interest in lowering the average rate of mortality.

The Panopticon

The panopticon is a design of institutional building with an inbuilt system of control, originated by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be ...

was intended to be cheaper than the prisons of his time, as it required fewer staff; "Allow me to construct a prison on this model", Bentham requested to a Committee for the Reform of Criminal Law, "I will be the gaoler. You will see ... that the gaoler will have no salary—will cost nothing to the nation." As the watchmen cannot be seen, they need not be on duty at all times, effectively leaving the watching to the watched. According to Bentham's design, the prisoners would also be used as menial labour, walking on wheels to spin looms or run a water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous b ...

. This would decrease the cost of the prison and give a possible source of income.

The ultimately abortive proposal for a panopticon prison to be built in England was one among his many proposals for legal and social reform. But Bentham spent some sixteen years of his life developing and refining his ideas for the building and hoped that the government would adopt the plan for a National Penitentiary appointing him as contractor-governor. Although the prison was never built, the concept had an important influence on later generations of thinkers. Twentieth-century French philosopher Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault ( , ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French History of ideas, historian of ideas and Philosophy, philosopher who was also an author, Literary criticism, literary critic, Activism, political activist, and teacher. Fo ...

argued that the panopticon was paradigmatic of several 19th-century " disciplinary" institutions. Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the King and an aristocratic elite. Philip Schofield argues that it was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of "sinister interest"—that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest—which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.

Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. Although this was common land, with no landowner, there were a number of parties with interests in it, including Earl Grosvenor, who owned a house on an adjacent site and objected to the idea of a prison overlooking it. Again, therefore, the scheme ground to a halt At this point, however, it became clear that a nearby site at Millbank, adjoining the Thames, was available for sale, and this time things ran more smoothly. Using government money, Bentham bought the land on behalf of the Crown for £12,000 in November 1799.

From his point of view, the site was far from ideal, being marshy, unhealthy, and too small. When he asked the government for more land and more money, however, the response was that he should build only a small-scale experimental prison—which he interpreted as meaning that there was little real commitment to the concept of the panopticon as a cornerstone of penal reform. Negotiations continued, but in 1801 Pitt resigned from office, and in 1803 the new Addington administration decided not to proceed with the project. Bentham was devastated: "They have murdered my best days."

Nevertheless, a few years later the government revived the idea of a National Penitentiary, and in 1811 and 1812 returned specifically to the idea of a panopticon. Bentham, now aged 63, was still willing to be governor. However, as it became clear that there was still no real commitment to the proposal, he abandoned hope, and instead turned his attentions to extracting financial compensation for his years of fruitless effort. His initial claim was for the enormous sum of nearly £700,000, but he eventually settled for the more modest (but still considerable) sum of £23,000. The Penitentiary House, etc. Act 1812 ( 52 Geo. 3. c. 44) transferred his title in the site to the Crown.

More successful was his cooperation with Patrick Colquhoun in tackling the corruption in the Pool of London. This resulted in the Depredations on the Thames Act 1800 ( 39 & 40 Geo. 3. c. 87). The Act created the Thames River Police, which was the first preventive police force in the country and was a precedent for Robert Peel's reforms 30 years later.Everett, Charles Warren. 1969. ''Jeremy Bentham''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. . .

Correspondence and contemporary influences

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the ageing

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the ageing Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, in an unsuccessful attempt to convince Smith that interest rates should be allowed to freely float. As a result of his correspondence with Mirabeau and other leaders of the French Revolution, Bentham was declared an honorary citizen of France. He was an outspoken critic of the revolutionary discourse of natural rights and of the violence that arose after the Jacobins took power (1792). Between 1808 and 1810, he held a personal friendship with Latin American

Latin Americans (; ) are the citizenship, citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America).

Latin American countries and their Latin American diaspora, diasporas are Metroethnicity, ...

revolutionary Francisco de Miranda and paid visits to Miranda's Grafton Way house in London. He also developed links with José Cecilio del Valle.

In 1821, John Cartwright proposed to Bentham that they serve as "Guardians of Constitutional Reform", seven "wise men" whose reports and observations would "concern the entire Democracy or Commons of the United Kingdom". Describing himself, among the names mentioned which also included Sir Francis Burdett, George Ensor, and Sir Matthew Wood, and as a "nonentity", Bentham declined the offer.

South Australian colony proposal

On 3 August 1831 the Committee of the National Colonization Society approved the printing of its proposal to establish a free colony on the south coast of Australia, funded by the sale of appropriated colonial lands, overseen by a joint-stock company, and which would be granted powers of self-government as soon as was practicable. Contrary to assumptions, Bentham had no hand in the preparation of the 'Proposal to His Majesty's Government for founding a colony on the Southern Coast of Australia, which was prepared under the auspices of Robert Gouger, Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, and Anthony Bacon. Bentham did, however, in August 1831, draft an unpublished work entitled 'Colonization Company Proposal', which constitutes his commentary upon the National Colonization Society's 'Proposal'.Westminster Review

In 1823, he co-founded '' The Westminster Review'' with James Mill as a journal for the " Philosophical Radicals"—a group of younger disciples through whom Bentham exerted considerable influence in British public life. One was John Bowring, to whom Bentham became devoted, describing their relationship as "son and father": he appointed Bowring political editor of ''The Westminster Review'' and eventually his literary executor. Another was Edwin Chadwick, who wrote on hygiene, sanitation, and policing and was a major contributor to the Poor Law Amendment Act: Bentham employed Chadwick as a secretary and bequeathed him a large legacy.Personal life

Bentham lived a highly structured and disciplined life, but he also exhibited eccentric behavior. He referred to his walking stick as "Dapple" and his cat as "The Reverend Sir John Langbourne." He had several infatuations with women, and wrote on sex. But he never married. Bentham's daily pattern was to rise at 6 am, walk for 2 hours or more, and then work until 4 pm. An insight into his character is given in Michael St. John Packe's ''The Life of John Stuart Mill'': A psychobiographical study by Philip Lucas and Anne Sheeran argues that he may have had Asperger's syndrome.Work

Animal rights

Bentham is widely regarded as one of the earliest proponents ofanimal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all Animal consciousness, sentient animals have Moral patienthood, moral worth independent of their Utilitarianism, utility to humans, and that their most basic interests—such as ...

. He argued and believed that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, should be the benchmark, or what he called the "insuperable line". If reason alone were the criterion by which we judge who ought to have rights, human infants and adults with certain forms of disability might fall short, too.Bentham, Jeremy. 1780.Of the Limits of the Penal Branch of Jurisprudence

. pp. 307–335 in '' An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation''. London: T. Payne and Sons. In 1780, alluding to the limited degree of legal protection afforded to

slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

s in the French West Indies by the Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by King Louis XIV, Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of Slavery in France, slavery in the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies ...

, he wrote:Earlier in the paragraph, Bentham makes clear that he accepted that animals could be killed for food, or in defence of human life, provided that the animal was not made to suffer unnecessarily. Bentham did not object to medical experiments on animals, providing that the experiments had in mind a particular goal of benefit to humanity, and had a reasonable chance of achieving that goal. He wrote that otherwise he had a "decided and insuperable objection" to causing pain to animals, in part because of the harmful effects such practices might have on human beings. In a letter to the editor of the '' Morning Chronicle'' in March 1825, he wrote:

Economics

Bentham's opinions aboutmonetary economics

Monetary economics is the branch of economics that studies the different theories of money: it provides a framework for analyzing money and considers its functions (as medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account), and it considers how m ...

were completely different from those of David Ricardo; however, they had some similarities to those of Henry Thornton. He focused on monetary expansion as a means of helping to create full employment. He was also aware of the relevance of forced saving, propensity to consume, the saving-investment relationship, and other matters that form the content of modern income and employment analysis. His monetary view was close to the fundamental concepts employed in his model of utilitarian decision making. His work is considered to be an early precursor of modern welfare economics

Welfare economics is a field of economics that applies microeconomic techniques to evaluate the overall well-being (welfare) of a society.

The principles of welfare economics are often used to inform public economics, which focuses on the ...

.

Bentham stated that pleasures and pains can be ranked according to their value or "dimension" such as intensity, duration, certainty of a pleasure or a pain. He was concerned with maxima and minima of pleasures and pains; and they set a precedent for the future employment of the maximisation principle in the economics of the consumer, the firm and the search for an optimum in welfare economics.

Bentham advocated "Pauper Management" which involved the creation of a chain of large workhouses.

Lawless writes that Bentham's "theoretical contributions to the political, economic, legal and psychological structures of English capitalism were enormous. Even Marx moved through a world that had been well-described by the arch-Philistine's voice. In his unique way, Bentham defined and analyzed the England of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, creating not only a comprehensive social theory but, with the help of James Mill and others, a political movement to go with it ."

Gender and sexuality

Bentham said that it was the placing of women in a legally inferior position that made him choose in 1759, at the age of eleven, the career of a reformist, though American critic John Neal claimed to have convinced him to take up women's rights issues during their association between 1825 and 1827. Bentham spoke for a complete equality between the sexes, arguing in favour ofwomen's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

, a woman's right to obtain a divorce, and a woman's right to hold political office.

The essay "Paederasty (Offences Against One's Self)" argued for the liberalisation of laws prohibiting homosexual sex. The essay remained unpublished during his lifetime for fear of offending public morality. Some of Bentham's writings on "sexual non-conformity" were published for the first time in 1931, but ''Paederasty'' was not published until 1978. Bentham does not believe homosexual acts to be unnatural, describing them merely as "irregularities of the venereal appetite". The essay chastises the society of the time for making a disproportionate response to what Bentham appears to consider a largely private offence—public displays or forced acts being dealt with rightly by other laws. When the essay was published in the ''Journal of Homosexuality'' in 1978, the abstract stated that Bentham's essay was the "first known argument for homosexual law reform in England".

Imperialism

Bentham's writings in the early 1790s onwards expressed an opposition toimperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

. His 1793 pamphlet ''Emancipate Your Colonies!'' critiqued French colonialism. In the early 1820s, he argued that the liberal government in Spain should emancipate its New World colonies. In the essay ''Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace'', Bentham argued that Britain should emancipate its New World colonies and abandon its colonial ambitions. He argued that empire was bad for the greatest number in the metropole and the colonies. According to Bentham, empire was financially unsound, entailed taxation on the poor in the metropole, caused unnecessary expansion in the military apparatus, undermined the security of the metropole, and were ultimately motivated by misguided ideas of honour and glory.

Law reform

Bentham was the first person to be an aggressive advocate for the codification of ''all'' of the

Bentham was the first person to be an aggressive advocate for the codification of ''all'' of the common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

into a coherent set of statutes; he was actually the person who coined the verb "to codify" to refer to the process of drafting a legal code. He lobbied hard for the formation of codification commissions in both England and the United States, and went so far as to write to President James Madison in 1811 to volunteer to write a complete legal code for the young country. After he learned more about American law and realised that most of it was state-based, he promptly wrote to the governors of every single state with the same offer.

During his lifetime, Bentham's codification efforts were completely unsuccessful. Even today, they have been completely rejected by almost every common law jurisdiction, including England. However, his writings on the subject laid the foundation for the moderately successful codification work of David Dudley Field II in the United States a generation later.

Privacy

For Bentham, transparency had moral value. For example, journalism puts power-holders under moral scrutiny. However, Bentham wanted such transparency to apply to everyone influential. This he describes by picturing the world as a gymnasium in which each "gesture, every turn of limb or feature, in those whose motions have a visible impact on the general happiness, will be noticed and marked down". He considered both surveillance and transparency to be useful ways of generating understanding and improvements for people's lives.Racial views

Bentham believed each race to be different, independent of climate or place of birth. He wrote in '' An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation'':Theory of Fictions

Bentham’s Theory of Fictions explored how language shapes thought, particularly in legal and political discourse. He distinguished between "fabulous entities", which are purely imaginary (e.g., literary or mythological figures likePrince Hamlet

Prince Hamlet is the title character and protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Hamlet'' (1599–1601). He is the Prince of Denmark, nephew of the usurping King Claudius, Claudius, and son of King Hamlet, the previous King of Denmark. At ...

or a centaur), and "fictitious entities", which have no physical existence but are essential for reasoning (e.g., laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a Socia ...

, rights

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

, and obligations). Similar to Kant's categories, such as nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

, custom, or the social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

, these fictitious entities help structure human understanding but do not exist independently.

While Bentham acknowledged the necessity of "fictitious entities" for communication, he warned that they could obscure truth and be manipulated for deception, especially in law. He viewed legal fictions—such as the notion of corporate personhood or sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

—as tools that could be either useful or misleading, depending on their application. His analysis influenced later thinkers in legal theory, philosophy of language, and utilitarian ethics, advocating for clarity and empirical reasoning in public affairs.

Utilitarianism

Bentham today is considered as the "Father of Utilitarianism". His ambition in life was to create a "Pannomion", a complete utilitarian code of law. He not only proposed many legal and social reforms, but also expounded an underlying moral principle on which they should be based. This philosophy ofutilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

took for its "fundamental axiom" to be the notion that ''it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong''. Bentham claimed to have borrowed this concept from the writings of Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, although the closest that Priestley in fact came to expressing it was in the form "the good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of any state, is the great standard by which relating to that state must finally be determined."

Bentham was a rare major figure in the history of philosophy to endorse psychological egoism. He was also a determined opponent of religion, as Crimmins observes: "Between 1809 and 1823 Jeremy Bentham carried out an exhaustive examination of religion with the declared aim of extirpating religious beliefs, even the idea of religion itself, from the minds of men."

Bentham also suggested a procedure for estimating the moral status of any action, which he called the hedonistic or felicific calculus.

Principle of utility

The principle of utility, or " greatest happiness principle", forms the cornerstone of all Bentham's thought. By "happiness", he understood a predominance of "pleasure" over "pain". He wrote in '' An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation'':

Bentham's ''Principles of Morals and Legislation'' focuses on the principle of utility and how this view of morality ties into legislative practices. His principle of utility regards ''good'' as that which produces the greatest amount of pleasure and the minimum amount of pain and ''evil'' as that which produces the most pain without the pleasure. This concept of pleasure and pain is defined by Bentham as physical as well as spiritual. Bentham writes about this principle as it manifests itself within the legislation of a society.

In order to measure the extent of pain or pleasure that a certain decision will create, he lays down a set of criteria divided into the categories of intensity, duration, certainty, proximity, productiveness, purity, and extent. Using these measurements, he reviews the concept of punishment and when it should be used as far as whether a punishment will create more pleasure or more pain for a society.

He calls for legislators to determine whether punishment creates an even more evil offence. Instead of suppressing the evil acts, Bentham argues that certain unnecessary laws and punishments could ultimately lead to new and more dangerous vices than those being punished to begin with, and calls upon legislators to measure the pleasures and pains associated with any legislation and to form laws in order to create the greatest good for the greatest number. He argues that the concept of the individual pursuing his or her own happiness cannot be necessarily declared "right", because often these individual pursuits can lead to greater pain and less pleasure for a society as a whole. Therefore, the legislation of a society is vital to maintain the maximum pleasure and the minimum degree of pain for the greatest number of people.

Hedonistic/felicific calculus

In his exposition of the felicific calculus, Bentham proposed a classification of 12 pains and 14 pleasures, by which we might test the "happiness factor" of any action. For Bentham, according to P. J. Kelly, the law "provides the basic framework of social interaction by delimiting spheres of personal inviolability within which individuals can form and pursue their own conceptions of well-being". It provides security, a precondition for the formation of expectations. As the hedonic calculus shows "expectation utilities" to be much higher than natural ones, it follows that Bentham does not favour the sacrifice of a few to the benefit of the many. Law professor Alan Dershowitz has quoted Bentham to argue that torture should sometimes be permitted.Criticisms

Utilitarianism was revised and expanded by Bentham's studentJohn Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

, who sharply criticised Bentham's view of human nature, which failed to recognise conscience as a human motive. Mill considered Bentham's view "to have done and to be doing very serious evil." In Mill's hands, "Benthamism" became a major element in the liberal conception of state policy objectives.

Bentham's critics have claimed that he undermined the foundation of a free society by rejecting natural rights. Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote "The principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number was as inimical to the idea of liberty as to the idea of rights."

Bentham's "hedonistic" theory (a term from J. J. C. Smart) is often criticised for lacking a principle of fairness embodied in a conception of justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

. In ''Bentham and the Common Law Tradition'', Gerald J. Postema states: "No moral concept suffers more at Bentham's hand than the concept of justice. There is no sustained, mature analysis of the notion." Thus, some critics object, it would be acceptable to torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

one person if this would produce an amount of happiness in other people outweighing the unhappiness of the tortured individual. However, as P. J. Kelly argued in ''Utilitarianism and Distributive Justice: Jeremy Bentham and the Civil Law'', Bentham had a theory of justice that prevented such consequences.

Legacy

Bentham influenced economists such as Milton Friedman and Henry Hazlitt.

In their youth,

Bentham influenced economists such as Milton Friedman and Henry Hazlitt.

In their youth, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. and viewed Bentham's views as too English and ''

Bentham is widely associated with the foundation in 1826 of London University (the institution that, in 1836, became

Bentham is widely associated with the foundation in 1826 of London University (the institution that, in 1836, became

A Table of the Springs of Action

'. London: sold by R. Hunter. * 1817. "Swear Not At All" * 1817. '' Plan of Parliamentary Reform, in the form of Catechism with Reasons for Each Article, with An Introduction shewing the Necessity and the Inadequacy of Moderate Reform''. London: R. Hunter. * 1818. Church-of-Englandism and its Catechism Examined. London:

The Elements of the Art of Packing, as applied to special juries particularly in cases of libel law

'. London: Effingham Wilson. * 1821. * 1822. ''The Influence of Natural Religion upon the Temporal Happiness of Mankind'', written with George Grote ** Published under the

A Treatise on Judicial Evidence Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq

' (1st ed.), edited by M. Dumont. London: Baldwin, Cradock, & Joy. * 1827.

Rationale of Judicial Evidence, specially applied to English Practice, Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq. I

' (1st ed.). London: Hunt & Clarke. * 1830. * 1834.

"Critique of the Doctrine of Inalienable, Natural Rights"

in '' Anarchical Fallacies'', vol. 2 of Bowring (ed.), ''Works'', 1843. * Jeremy Bentham

"Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty"

c. 1785, free audiobook from LibriVox.

Transcribe Bentham

initiative run by the Bentham Project that has its own website with useful links.

The curious case of Jeremy Bentham

a

Random-Times.com

Jeremy Bentham

categorised links

has an extensive biographical reference of Bentham.

"Jeremy Bentham at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2007"

A play-reading of the life and legacy of Jeremy Bentham.

Jeremy Bentham

biographical profile, including quotes and further resources, a

Utilitarianism.net

Bentham Book Collection

at

Bentham Papers

at

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. and viewed Bentham's views as too English and ''

petite bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi- autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as s ...

'', saying "With the dullest naïveté he takes the modern petty-bourgeois philistine, especially the English philistine, as the normal man. Whatever is useful to this queer variety of normal man, and to his world, is useful in and for itself. This yardstick, then, he applies to past, present and future."

The Faculty of Laws at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

occupies Bentham House, next to the main UCL campus.

Bentham's name was adopted by the Australian litigation funder IMF Limited to become Bentham IMF Limited on 28 November 2013, in recognition of Bentham being "among the first to support the utility of litigation funding".

Death and the auto-icon

Bentham died on 6 June 1832, aged 84, at his residence in Queen Square Place inWestminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, London. He had continued to write up to a month before his death, and had made careful preparations for the dissection of his body after death and its preservation as an auto-icon. As early as 1769, when Bentham was 21 years old, he made a will leaving his body for dissection to a family friend, the physician and chemist George Fordyce, whose daughter, Maria Sophia (1765–1858), married Jeremy's brother Samuel Bentham

Brigadier General Sir Samuel Bentham (11 January 1757 – 31 May 1831) was an England, English mechanical engineering, mechanical engineer and naval architect credited with numerous innovations, particularly related to naval architecture, incl ...

. A paper written in 1830, instructing Thomas Southwood Smith to create the auto-icon, was attached to his last will, dated 30 May 1832. It stated:

Bentham's wish to preserve his dead body was consistent with his philosophy of utilitarianism. In his essay ''Auto-Icon, or Farther Uses of the Dead to the Living'', Bentham wrote, "If a country gentleman has rows of trees leading to his dwelling, the auto-icons of his family might alternate with the trees; copal varnish would protect the face from the effects of rain." On 8 June 1832, two days after his death, invitations were distributed to a select group of friends, and on the following day at 3 p.m., Southwood Smith delivered a lengthy oration over Bentham's remains in the Webb Street School of Anatomy & Medicine in Southwark, London. The printed oration contains a frontispiece with an engraving of Bentham's body partly covered by a sheet.

Afterward, the skeleton and head were preserved and stored in a wooden cabinet called the "auto-icon", with the skeleton padded out with hay and dressed in Bentham's clothes. From 1833, it stood in Southwood Smith's Finsbury Square

Finsbury Square is a square in Finsbury in central London which includes a six-rink grass bowling green. It was developed in 1777 on the site of a previous area of green space to the north of the City of London known as Finsbury Fields, in the p ...

consulting rooms until he abandoned private practice in the winter of 1849–50, when it was moved to 36 Percy Street, the studio of his unofficial partner, painter Margaret Gillies, who made studies of it. In March 1850, Southwood Smith offered the auto-icon to Henry Brougham, who readily accepted it for UCL.

It is currently kept on public display at the main entrance of the UCL Student Centre. It was previously displayed at the end of the South Cloisters in the main building of the college until it was moved in 2020. Upon the retirement of Sir Malcolm Grant as provost of the college in 2013, however, the body was present at Grant's final council meeting. As of 2013, this was the only time that the body of Bentham has been taken to a UCL council meeting. (There is a persistent myth that the body of Bentham is present at all council meetings noted as "Present-but not voting".)

Bentham had intended the auto-icon to incorporate his actual head, mummified to resemble its appearance in life. Southwood Smith's experimental efforts at mummification – based on the preservation practices of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

's indigenous Māori – involved placing the head under an air pump over sulphuric acid and drawing off the fluids. Although technically successful, they left the head looking distastefully macabre, with dried and darkened skin stretched tautly over the skull.

The auto-icon was therefore given a wax head, fitted with some of Bentham's own hair. The real head was displayed in the same case as the auto-icon for many years, but became the target of repeated student pranks. It was later locked away.

In 2020, the auto-icon was put into a new glass display case and moved to the entrance of UCL's new Student Centre on Gordon Square

Gordon Square is a public park square in Bloomsbury, London, England. It is part of the Bedford Estate and was designed as one of a pair with the nearby Tavistock Square. It is owned by the University of London.

History and buildings

The sq ...

.

University College London

University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

), though he was 78 years old when the university opened and played only an indirect role in its establishment. His direct involvement was limited to his buying a single £100 share in the new university, making him just one of over a thousand shareholders.

Bentham and his ideas can nonetheless be seen as having inspired several of the actual founders of the university. He strongly believed that education should be more widely available, particularly to those who were not wealthy or who did not belong to the established church; in Bentham's time, membership of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

and the capacity to bear considerable expenses were required of students entering the Universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. As the University of London was the first in England to admit all, regardless of race, creed or political belief, it was largely consistent with Bentham's vision. There is some evidence that, from the sidelines, he played a "more than passive part" in the planning discussions for the new institution, although it is also apparent that "his interest was greater than his influence". He failed in his efforts to see his disciple John Bowring appointed professor of English or History, but he did oversee the appointment of another pupil, John Austin, as the first professor of Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

in 1829.

The more direct associations between Bentham and UCL—the college's custody of his Auto-icon (see above) and of the majority of his surviving papers—postdate his death by some years: the papers were donated in 1849, and the Auto-icon in 1850. A large painting by Henry Tonks

Henry Tonks, Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, FRCS (9 April 1862 – 8 January 1937) was a British surgeon and later draughtsman and painter of figure subjects, chiefly interiors, and a Caricature, caricaturist. He became an influentia ...

hanging in UCL's Flaxman Gallery depicts Bentham approving the plans of the new university, but it was executed in 1922 and the scene is entirely imaginary. Since 1959 (when the Bentham Committee was first established), UCL has hosted the Bentham Project, which is progressively publishing a definitive edition of Bentham's writings.

UCL now endeavours to acknowledge Bentham's influence on its foundation, while avoiding any suggestion of direct involvement, by describing him as its "spiritual founder".

Bibliography

Bentham was an obsessive writer and reviser, but was only able on rare occasions of bringing his work to completion and publication. Most of what appeared in print in his lifetime was prepared for publication by others. Several of his works first appeared in French translation, prepared for the press by Étienne Dumont, for example, ''Theory of Legislation'', Volume 2 (''Principles of the Penal Code'') 1840, Weeks, Jordan, & Company. Boston. Some made their first appearance in English in the 1820s as a result of back-translation from Dumont's 1802 collection (and redaction) of Bentham's writing on civil and penal legislation.Publications

* 1776. ** This was an unsparing criticism of some introductory passages relating to political theory in William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. The book, published anonymously, was well received and credited to some of the greatest minds of the time. Bentham disagreed with Blackstone's defence of judge-made law, his defence of legal fictions, his theological formulation of the doctrine of mixed government, his appeal to asocial contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

and his use of the vocabulary of natural law. Bentham's "Fragment" was only a small part of a Commentary on the Commentaries, which remained unpublished until the twentieth century.

* 1776.

** An attack on the United States Declaration of Independence.

* 1780. '' An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation''. London: T. Payne and Sons.

* 1785 (publ. 1978). "Offences Against One's Self", edited by L. Crompton. '' Journal of Homosexuality'' 3(4)389–405. Continued in vol. 4(1). . . .

* 1787.

* 1787. ''Defence of Usury''.

** A series of thirteen "Letters" addressed to Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

.

* 1791. "Essay on Political Tactics" (1st ed.). London: T. Payne.

* 1796. ''Anarchical Fallacies; Being an examination of the Declaration of Rights issued during the French Revolution''.

** An attack on the Declaration of the Rights of Man decreed by the French Revolution, and critique of the natural rights philosophy underlying it.

* 1802. ''Traités de législation civile et pénale'', 3 vols, edited by Étienne Dumont.

* 1811. ''Punishments and Rewards''.

* 1812. ''Panopticon versus New South Wales: or, the Panopticon Penitentiary System, Compared''. Includes:

*# Two Letters to Lord Pelham, Secretary of State, Comparing the two Systems on the Ground of Expediency.

*# "Plea for the Constitution: Representing the Illegalities involved in the Penal Colonization System (1803, first publ. 1812)

* 1816. ''Defence of Usury; shewing the impolicy of the present legal restraints on the terms of pecuniary bargains in a letters to a friend to which is added a letter to Adam Smith, Esq. LL.D. on the discouragement opposed by the above restraints to the progress of inventive industry'' (3rd ed.). London: Payne & Foss.

** Bentham wrote a series of thirteen "Letters" addressed to Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, published in 1787 as ''Defence of Usury''. Bentham's main argument against the restriction is that "projectors" generate positive externalities. G. K. Chesterton identified Bentham's essay on usury as the very beginning of the "modern world". Bentham's arguments were very influential. "Writers of eminence" moved to abolish the restriction, and repeal was achieved in stages and fully achieved in England in 1854. There is little evidence as to Smith's reaction. He did not revise the offending passages in ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', usually referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is a book by the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosophy, moral philosopher Adam Smith; ...

'' (1776), but Smith made little or no substantial revisions after the third edition of 1784.

* 1817. A Table of the Springs of Action

'. London: sold by R. Hunter. * 1817. "Swear Not At All" * 1817. '' Plan of Parliamentary Reform, in the form of Catechism with Reasons for Each Article, with An Introduction shewing the Necessity and the Inadequacy of Moderate Reform''. London: R. Hunter. * 1818. Church-of-Englandism and its Catechism Examined. London:

Effingham Wilson

Effingham William Wilson (28 September 1785 – 9 June 1868) was a 19th-century English political radicalism, radical publisher and bookseller. His main interests were in economics and politics, but he also published poetry.

Early life

Wil ...

.

* 1821. The Elements of the Art of Packing, as applied to special juries particularly in cases of libel law

'. London: Effingham Wilson. * 1821. * 1822. ''The Influence of Natural Religion upon the Temporal Happiness of Mankind'', written with George Grote ** Published under the

pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true meaning ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individual's o ...

Philip Beauchamp.

* 1823. Not Paul But Jesus

** Published under the pseudonym Gamaliel Smith.

* 1824. '' The Book of Fallacies from Unfinished Papers of Jeremy Bentham'' (1st ed.). London: John and H. L. Hunt.

* 1825. A Treatise on Judicial Evidence Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq

' (1st ed.), edited by M. Dumont. London: Baldwin, Cradock, & Joy. * 1827.

Rationale of Judicial Evidence, specially applied to English Practice, Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq. I

' (1st ed.). London: Hunt & Clarke. * 1830. * 1834.

Posthumous publications

On his death, Bentham left manuscripts amounting to an estimated 30 million words, which are now largely held by University College London's Special Collections (manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

folio

The term "folio" () has three interconnected but distinct meanings in the world of books and printing: first, it is a term for a common method of arranging Paper size, sheets of paper into book form, folding the sheet only once, and a term for ...

s) and the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. Based in London, it is one of the largest libraries in the world, with an estimated collection of between 170 and 200 million items from multiple countries. As a legal deposit li ...

( folios). University College London also holds a collection of c.500 books either by, about, or owned by Jeremy Bentham.

Bowring (1838–1843)

John Bowring, the young radical writer who had been Bentham's intimate friend and disciple, was appointed his literary executor and charged with the task of preparing a collected edition of his works. This appeared in 11 volumes in 1838–1843. Bowring based much of his edition on previously published texts (including those of Dumont) rather than Bentham's own manuscripts, and elected not to publish Bentham's works on religion at all. The edition was described by the '' Edinburgh Review'' on first publication as "incomplete, incorrect and ill-arranged", and has since been repeatedly criticised both for its omissions and for errors of detail; while Bowring's memoir of Bentham's life included in volumes 10 and 11 was described by Sir Leslie Stephen as "one of the worst biographies in the language". Nevertheless, Bowring's remained the standard edition of most of Bentham's writings for over a century, and is still only partially superseded: it includes such interesting writings on international relations as Bentham's A Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace written 1786–89, which forms part IV of the Principles of International Law.Stark (1952–1954)

In 1952–1954, Werner Stark published a three-volume set, ''Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings'', in which he attempted to bring together all of Bentham's writings on economic matters, including both published and unpublished material. Although a significant achievement, the work is considered by scholars to be flawed in many points of detail, and a new edition of the economic writings (retitled ''Writings on Political Economy'') is currently in course of publication by the Bentham Project.Bentham Project (1968–present)

In 1959, the Bentham Committee was established under the auspices of University College London with the aim of producing a definitive edition of Bentham's writings. It set up the Bentham Project to undertake the task, and the first volume in '' The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham'' was published in 1968. The ''Collected Works'' are providing many unpublished works, as well as much-improved texts of works already published. To date, 38 volumes have appeared; the complete edition is projected to total 80. The volume ''Of Laws in General'' (1970) was found to contain many errors and has been replaced by ''Of the Limits of the Penal Branch of Jurisprudence'' (2010) In 2017, Volumes 1–5 were re-published in open access by UCL Press. To assist in this task, the Bentham papers at UCL are being digitised by crowdsourcing their transcription. Transcribe Bentham is a crowdsourced manuscript transcription project, run byUniversity College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

's Bentham Project, in partnership with UCL's UCL Centre for Digital Humanities, UCL Library Services, UCL Learning and Media Services, the University of London Computer Centre, and the online community. The project was launched in September 2010 and is making freely available, via a specially designed transcription interface, digital images of UCL's vast Bentham Papers collection—which runs to some 60,000 manuscript folios—to engage the public and recruit volunteers to help transcribe the material. Volunteer-produced transcripts will contribute to the Bentham Project's production of the new edition of ''The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham'', and will be uploaded to UCL's digital Bentham Papers repository, widening access to the collection for all and ensuring its long-term preservation. Manuscripts can be viewed and transcribed by signing-up for a transcriber account at the Transcription Desk, via the Transcribe Bentham website.

Free, flexible textual search of the full collection of Bentham Papers is now possible through an experimental handwritten text image indexing and search system, developed by the PRHLT research center in the framework of the READ project.

See also

* List of animal rights advocates * List of civil rights leaders * List of liberal theorists * * *References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * Jeremy Bentham"Critique of the Doctrine of Inalienable, Natural Rights"

in '' Anarchical Fallacies'', vol. 2 of Bowring (ed.), ''Works'', 1843. * Jeremy Bentham

"Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty"

c. 1785, free audiobook from LibriVox.

External links

* * * *Transcribe Bentham

initiative run by the Bentham Project that has its own website with useful links.

The curious case of Jeremy Bentham

a

Random-Times.com

Jeremy Bentham

categorised links

has an extensive biographical reference of Bentham.

"Jeremy Bentham at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2007"

A play-reading of the life and legacy of Jeremy Bentham.

Jeremy Bentham

biographical profile, including quotes and further resources, a

Utilitarianism.net

Bentham Book Collection

at

University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

Bentham Papers

at

University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bentham, Jeremy

1748 births

1832 deaths

18th century in LGBTQ history

18th-century atheists

19th-century atheists

18th-century British philosophers

19th-century British philosophers

18th-century English writers

18th-century male writers

19th-century English writers

Animal rights scholars

Atheist philosophers

British ethicists

British reformers

British social liberals

Consequentialists

English atheists

English human rights activists

English male non-fiction writers

English philosophers

English political philosophers

Jeremy Bentham

LGBTQ history in the United Kingdom

Mummies

People associated with University College London

People educated at Westminster School, London

People from the City of London

Philosophers of law

Social philosophers

University College London

Utilitarians