Jefferson Davis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

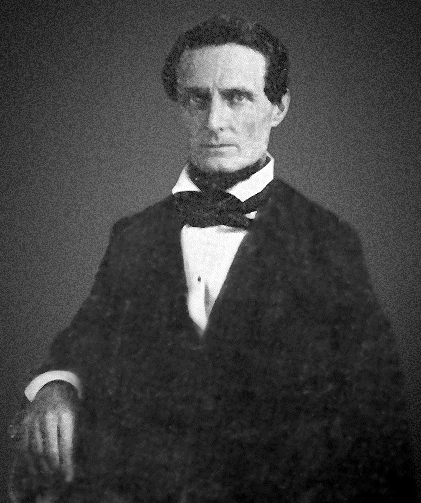

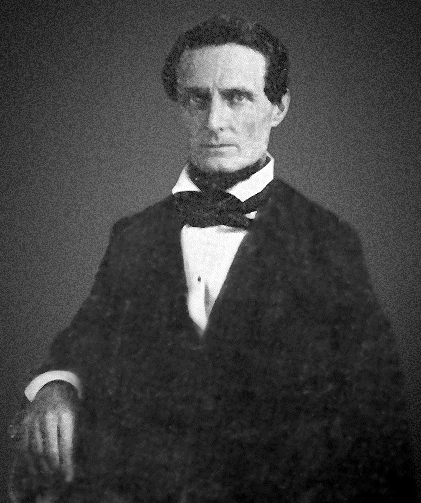

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the

When Davis returned to Mississippi he decided to become a planter. His brother Joseph was successfully converting his large holdings at Davis Bend, about south of

When Davis returned to Mississippi he decided to become a planter. His brother Joseph was successfully converting his large holdings at Davis Bend, about south of

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the

Davis took his seat in December and was appointed as a regent of the

Davis took his seat in December and was appointed as a regent of the

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his Secretary of War. Davis championed a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific, arguing it was needed for national defense, and was entrusted with overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys to determine which of four possible routes was the best. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his Secretary of War. Davis championed a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific, arguing it was needed for national defense, and was entrusted with overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys to determine which of four possible routes was the best. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern

The Senate recessed in March and did not reconvene until November 1857. The session opened with the Senate debating the Lecompton Constitution submitted by a convention in Kansas territory that would allow it to be admitted as a slave state. The issue divided the Democratic Party. Davis supported it, but it was not passed, in part because the leading Democrat in the North, Stephen Douglas, refused to support its passage because he felt it did not represent the true will of the settlers in Kansas. The controversy further undermined the alliance between northern and southern Democrats.

Davis's participation in the Senate was interrupted by a severe illness in early 1858. Davis, who regularly suffered from ill health, had a recurring case of iritis, which threatened the loss of his left eye and left him bedridden for seven weeks. He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. While recovering, he gave speeches in Maine, Boston, and New York, emphasizing the common heritage of all Americans and the importance of the constitution for defining the nation. Because his speeches had angered some states' rights supporters in the South, Davis was required to clarify his comments when he returned to Mississippi. He stated that he felt positively about the benefits of Union, but acknowledged that the Union could be dissolved if states' rights were violated and one section of the country imposed its will on another. Speaking to the Mississippi Legislature on November 16, 1858, Davis stated "if an Abolitionist be chosen President of the United States... I should deem it your duty to provide for your safety outside of a Union with those who have already shown the will...to deprive you of your birthright and to reduce you to worse than the colonial dependence of your fathers."

In February 1860, Davis presented a series of resolutions defining the relationship between the states under the constitution, including the assertion that Americans had a constitutional right to bring slaves into territories. These resolutions were seen as setting the agenda for the Democratic Party nomination, ensuring that Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty, known as the Freeport Doctrine, would be excluded from the party platform. At the Democratic convention, the party split: Douglas was nominated by the Northern half and Vice President John C. Breckinridge was nominated by the Southern half. The Republican Party nominee

The Senate recessed in March and did not reconvene until November 1857. The session opened with the Senate debating the Lecompton Constitution submitted by a convention in Kansas territory that would allow it to be admitted as a slave state. The issue divided the Democratic Party. Davis supported it, but it was not passed, in part because the leading Democrat in the North, Stephen Douglas, refused to support its passage because he felt it did not represent the true will of the settlers in Kansas. The controversy further undermined the alliance between northern and southern Democrats.

Davis's participation in the Senate was interrupted by a severe illness in early 1858. Davis, who regularly suffered from ill health, had a recurring case of iritis, which threatened the loss of his left eye and left him bedridden for seven weeks. He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. While recovering, he gave speeches in Maine, Boston, and New York, emphasizing the common heritage of all Americans and the importance of the constitution for defining the nation. Because his speeches had angered some states' rights supporters in the South, Davis was required to clarify his comments when he returned to Mississippi. He stated that he felt positively about the benefits of Union, but acknowledged that the Union could be dissolved if states' rights were violated and one section of the country imposed its will on another. Speaking to the Mississippi Legislature on November 16, 1858, Davis stated "if an Abolitionist be chosen President of the United States... I should deem it your duty to provide for your safety outside of a Union with those who have already shown the will...to deprive you of your birthright and to reduce you to worse than the colonial dependence of your fathers."

In February 1860, Davis presented a series of resolutions defining the relationship between the states under the constitution, including the assertion that Americans had a constitutional right to bring slaves into territories. These resolutions were seen as setting the agenda for the Democratic Party nomination, ensuring that Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty, known as the Freeport Doctrine, would be excluded from the party platform. At the Democratic convention, the party split: Douglas was nominated by the Northern half and Vice President John C. Breckinridge was nominated by the Southern half. The Republican Party nominee

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Mississippi Governor

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Mississippi Governor

As the Southern states seceded, state authorities had been able to take over most federal facilities without bloodshed. But four forts— Fort Sumter in

As the Southern states seceded, state authorities had been able to take over most federal facilities without bloodshed. But four forts— Fort Sumter in

In addition to being the constitutional commander-in-chief of the Confederacy, Davis was operational leader of the military, as the Confederacy's military departments reported directly to him. Davis had a habit of overworking, particularly in minor military issues that could have been delegated. Some of his colleagues—such as Generals Joseph E. Johnston and his friend from West Point, Major General Leonidas Polk—encouraged him to lead the armies directly, but he let his generals direct the combat.

The major fighting in the East began when a Union army advanced into Northern Virginia in July 1861. It was defeated at Manassas by two Confederate forces commanded by Beauregard and Joseph Johnston. After the battle, Davis had to manage disagreements with the two generals: Beauregard, who was now a full general, was upset because he felt he was not given sufficient credit for his ideas; Joseph Johnston was upset because he felt he was not given the seniority of rank due to him.

In the West, Davis had to address another issue caused by one of his generals.

In addition to being the constitutional commander-in-chief of the Confederacy, Davis was operational leader of the military, as the Confederacy's military departments reported directly to him. Davis had a habit of overworking, particularly in minor military issues that could have been delegated. Some of his colleagues—such as Generals Joseph E. Johnston and his friend from West Point, Major General Leonidas Polk—encouraged him to lead the armies directly, but he let his generals direct the combat.

The major fighting in the East began when a Union army advanced into Northern Virginia in July 1861. It was defeated at Manassas by two Confederate forces commanded by Beauregard and Joseph Johnston. After the battle, Davis had to manage disagreements with the two generals: Beauregard, who was now a full general, was upset because he felt he was not given sufficient credit for his ideas; Joseph Johnston was upset because he felt he was not given the seniority of rank due to him.

In the West, Davis had to address another issue caused by one of his generals.

Around the time of the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson, Davis was inaugurated as president on February 22, 1862. In his inaugural speech, he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment. He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with

Around the time of the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson, Davis was inaugurated as president on February 22, 1862. In his inaugural speech, he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment. He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the

At the end of March, the Union army broke through the Confederate trench lines, forcing Lee to withdraw and abandon Richmond. Davis intended to stay as long as possible, but evacuated his family, which included

At the end of March, the Union army broke through the Confederate trench lines, forcing Lee to withdraw and abandon Richmond. Davis intended to stay as long as possible, but evacuated his family, which included

Davis's central concern during the war was to achieve Confederate independence. When Virginia seceded, the state convention offered Richmond as the Confederacy's capital and the provisional Confederate Congress accepted it. Davis favored the move. Richmond was a larger city, had better transportation links than Montgomery, and was home to the

Davis's central concern during the war was to achieve Confederate independence. When Virginia seceded, the state convention offered Richmond as the Confederacy's capital and the provisional Confederate Congress accepted it. Davis favored the move. Richmond was a larger city, had better transportation links than Montgomery, and was home to the

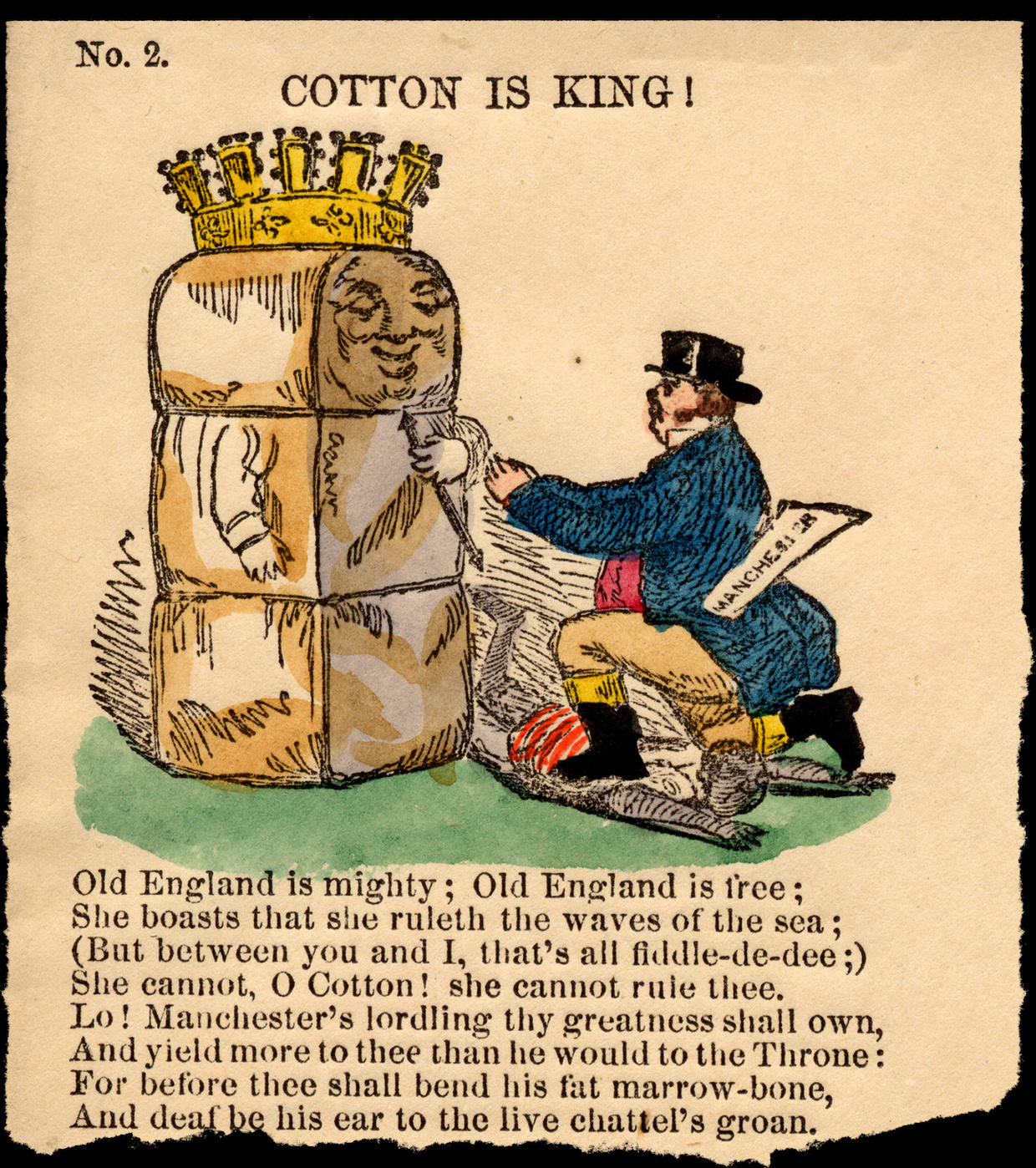

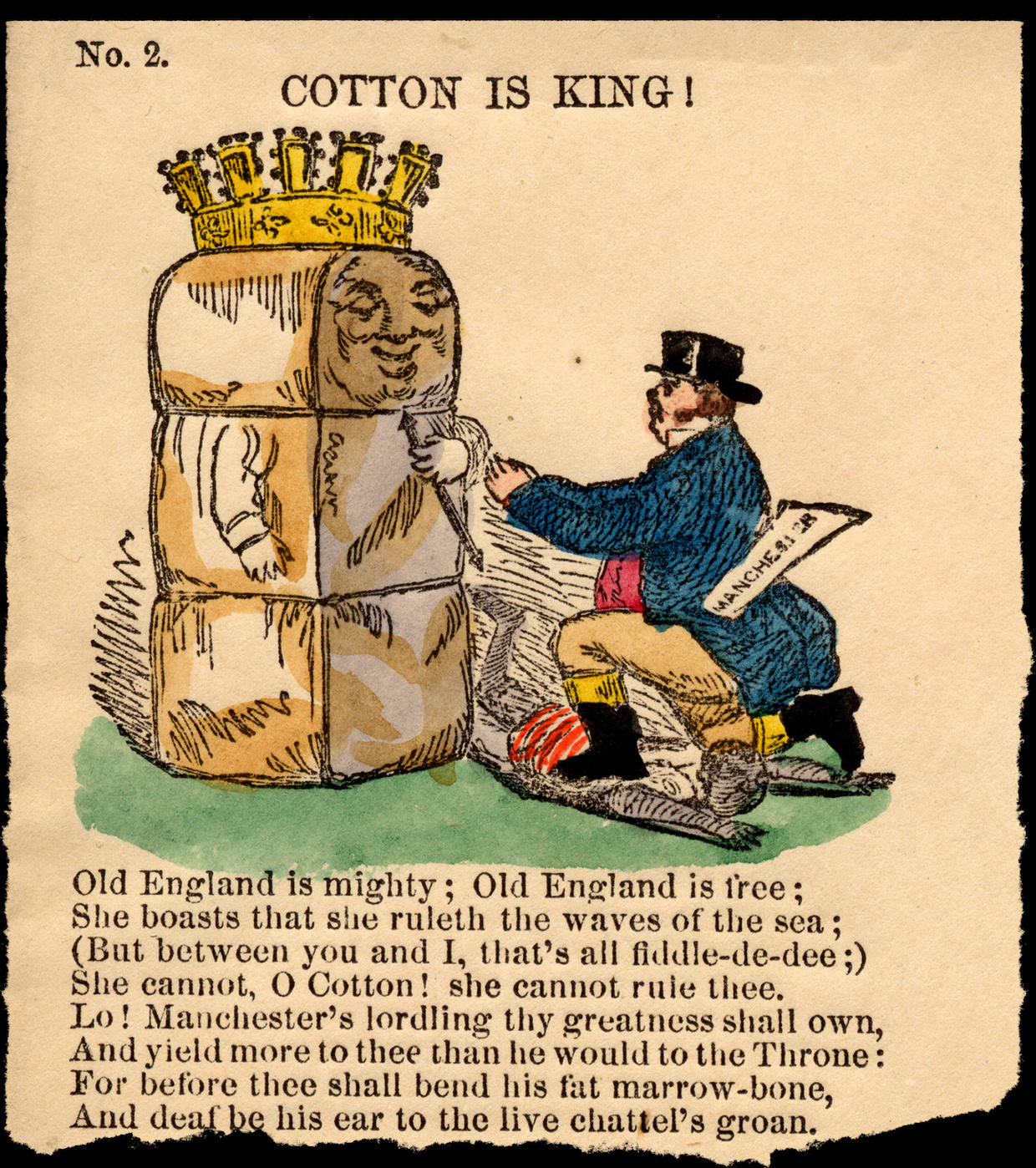

The main objective of Davis's foreign policy was to achieve foreign recognition, which would allow the Confederacy to secure international loans, receive foreign aid to open trade, and provide the possibility of a military alliance. Diplomacy was primarily focused on getting recognition from Britain. Davis was confident that Britain's and most other European nations' economic dependence on cotton from the South would quickly convince them to sign treaties with the Confederacy. Cotton had made up 61% of the value of all U.S. exports. The South filled most of the European cloth industry's need for cheap imported raw cotton: 77% of Britain's, 90% of France's, 60% of the German states', and 92% of Russia's. Around 20% of British workers were employed in the industry and half of British exports were finished cotton goods. Despite Britain's imperative need for cotton, the Confederacy was prepared to downplay the role of slavery as the

The main objective of Davis's foreign policy was to achieve foreign recognition, which would allow the Confederacy to secure international loans, receive foreign aid to open trade, and provide the possibility of a military alliance. Diplomacy was primarily focused on getting recognition from Britain. Davis was confident that Britain's and most other European nations' economic dependence on cotton from the South would quickly convince them to sign treaties with the Confederacy. Cotton had made up 61% of the value of all U.S. exports. The South filled most of the European cloth industry's need for cheap imported raw cotton: 77% of Britain's, 90% of France's, 60% of the German states', and 92% of Russia's. Around 20% of British workers were employed in the industry and half of British exports were finished cotton goods. Despite Britain's imperative need for cotton, the Confederacy was prepared to downplay the role of slavery as the

Although Davis thought the war might be a long one, he did not propose legislation or take executive action to create the needed financial structure for the Confederacy. Davis knew very little about public finance, and tended to let Secretary of the Treasury Memminger run the finances. Memminger's knowledge of economics was limited, and he was ineffective at getting Congress to listen to his suggestions. Until 1863, Davis's reports on the financial state of the Confederacy to Congress tended to be unduly optimistic; for instance, in 1862 he stated that the

Although Davis thought the war might be a long one, he did not propose legislation or take executive action to create the needed financial structure for the Confederacy. Davis knew very little about public finance, and tended to let Secretary of the Treasury Memminger run the finances. Memminger's knowledge of economics was limited, and he was ineffective at getting Congress to listen to his suggestions. Until 1863, Davis's reports on the financial state of the Confederacy to Congress tended to be unduly optimistic; for instance, in 1862 he stated that the

On May 22, Davis was imprisoned in Fort Monroe, Virginia, under the watch of Major General Nelson A. Miles. Initially, he was confined to a

On May 22, Davis was imprisoned in Fort Monroe, Virginia, under the watch of Major General Nelson A. Miles. Initially, he was confined to a  After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released at Richmond on May 13, 1867, on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released at Richmond on May 13, 1867, on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including

Davis went back to England to get his family in late summer of 1870. While there, he learned that his brother Joseph had died. When they returned, they first stayed at the Peabody Hotel, but eventually rented a house. When Robert E. Lee died in 1870, Davis delivered a public eulogy at the Lee Monument Association held in Richmond on November 3, emphasizing Lee's character and avoiding politics. He received other invitations. He declined most, but he gave the commencement speech at the University of the South in 1871 and a speech to the Virginia Historical Society at White Sulphur Springs declaring that the South had been cheated, and would not have surrendered if they had known what to expect from

Davis went back to England to get his family in late summer of 1870. While there, he learned that his brother Joseph had died. When they returned, they first stayed at the Peabody Hotel, but eventually rented a house. When Robert E. Lee died in 1870, Davis delivered a public eulogy at the Lee Monument Association held in Richmond on November 3, emphasizing Lee's character and avoiding politics. He received other invitations. He declined most, but he gave the commencement speech at the University of the South in 1871 and a speech to the Virginia Historical Society at White Sulphur Springs declaring that the South had been cheated, and would not have surrendered if they had known what to expect from

In January 1877, the author

In January 1877, the author

In November 1889, Davis left Beauvoir and embarked on a steamboat in New Orleans in a cold rain to visit his Brierfield plantation. He fell ill during the trip, but refused to send for a doctor. An employee at Brierfield telegrammed Varina, who took a northbound steamer from New Orleans and transferred to his vessel mid-river. He finally got medical care and was diagnosed with acute bronchitis complicated by malaria. When he returned to New Orleans, Davis's doctor Stanford E. Chaille pronounced him too ill to travel and he was taken to the home of

In November 1889, Davis left Beauvoir and embarked on a steamboat in New Orleans in a cold rain to visit his Brierfield plantation. He fell ill during the trip, but refused to send for a doctor. An employee at Brierfield telegrammed Varina, who took a northbound steamer from New Orleans and transferred to his vessel mid-river. He finally got medical care and was diagnosed with acute bronchitis complicated by malaria. When he returned to New Orleans, Davis's doctor Stanford E. Chaille pronounced him too ill to travel and he was taken to the home of

During his years as a senator, Davis was an advocate for the South, states' right and slavery.

In his 1848 speech on the Oregon Bill, Davis argued for a strict constructionist understanding of the Constitution. He insisted that the states are sovereign, all powers of the federal government are granted by those states, the Constitution recognized the right of states to allow citizens to have slaves as property, and the federal government was obligated to defend encroachments upon this right. In his February 13–14, 1850 speech on slavery in the territories, Davis stated that slaveholders must be allowed to bring their slaves into the territories, arguing that this does not increase slavery but diffuses it. He further stated that slavery does not need to be justified: it was sanctioned by religion and history, blacks were destined for bondage, their enslavement was a civilizing blessing to them that brought economic and social good to everyone. He described the growth of abolitionism in the north as a symptom of a growing desire to destroy the South and the foundations of the country: "fanaticism and ignorance–political rivalry–sectional hate–strife for sectional dominion, have accumulated into a mighty flood, and pour their turgid waters through the broken Constitution". On February 2, 1860, Davis presented a set of resolutions to the Senate that not only reaffirmed the constitutional rights of slave owners, but also declared that the federal government would be responsible for protecting slave owners and their slaves in the territories.

After secession and during the Civil War, Davis's speeches acknowledged the relationship between the Confederacy and slavery. In his February 1861 inaugural speech as provisional president of the Confederacy, Davis described the Confederate Constitution, which explicitly prevented Congress from passing any law affecting African American slavery and mandated the recognition and protection of that slavery in all Confederate territorial holdings, as a return to the intent of the original founders,} and his in April speech to Congress on the ratification of the Constitution, he described the cause of the war as being due to Northerners who wished to abolish slavery and destroy property worth thousands of millions of dollars. In his 1863 address to the Confederate Congress, Davis denounced the Emancipation Proclamation as evidence of the North's long-standing intention to destroy slavery and dooming African Americans, who he described as belonging to an inferior race, to extermination. In early 1864, Major General

During his years as a senator, Davis was an advocate for the South, states' right and slavery.

In his 1848 speech on the Oregon Bill, Davis argued for a strict constructionist understanding of the Constitution. He insisted that the states are sovereign, all powers of the federal government are granted by those states, the Constitution recognized the right of states to allow citizens to have slaves as property, and the federal government was obligated to defend encroachments upon this right. In his February 13–14, 1850 speech on slavery in the territories, Davis stated that slaveholders must be allowed to bring their slaves into the territories, arguing that this does not increase slavery but diffuses it. He further stated that slavery does not need to be justified: it was sanctioned by religion and history, blacks were destined for bondage, their enslavement was a civilizing blessing to them that brought economic and social good to everyone. He described the growth of abolitionism in the north as a symptom of a growing desire to destroy the South and the foundations of the country: "fanaticism and ignorance–political rivalry–sectional hate–strife for sectional dominion, have accumulated into a mighty flood, and pour their turgid waters through the broken Constitution". On February 2, 1860, Davis presented a set of resolutions to the Senate that not only reaffirmed the constitutional rights of slave owners, but also declared that the federal government would be responsible for protecting slave owners and their slaves in the territories.

After secession and during the Civil War, Davis's speeches acknowledged the relationship between the Confederacy and slavery. In his February 1861 inaugural speech as provisional president of the Confederacy, Davis described the Confederate Constitution, which explicitly prevented Congress from passing any law affecting African American slavery and mandated the recognition and protection of that slavery in all Confederate territorial holdings, as a return to the intent of the original founders,} and his in April speech to Congress on the ratification of the Constitution, he described the cause of the war as being due to Northerners who wished to abolish slavery and destroy property worth thousands of millions of dollars. In his 1863 address to the Confederate Congress, Davis denounced the Emancipation Proclamation as evidence of the North's long-standing intention to destroy slavery and dooming African Americans, who he described as belonging to an inferior race, to extermination. In early 1864, Major General

Although Davis served the United States as a soldier and a war hero, a respected politician who sat in both houses of Congress, and an effective cabinet officer, his legacy is mainly defined by role as president of the Confederacy. After the Civil War, journalist

Although Davis served the United States as a soldier and a war hero, a respected politician who sat in both houses of Congress, and an effective cabinet officer, his legacy is mainly defined by role as president of the Confederacy. After the Civil War, journalist

Vol I. (1824–1850)Vol. II (1850–1856)Vol. III (1856–1856)Vol. IV (1856–January, 1861)Vol. V (January, 1861 – August 1863)Vol. VI (August 1863 – May 1865)Vol. VII (May 1865–1877)Vol. VIII (1877–1881)Vol. IX (1881–1887)Vol. X (1887– 1891 ''includes letters to Varina about Davis''

* (14 Volumes) :* A selection of documents from ''The Papers of Jefferson Davis'' is available online: :* Volume 1 is available online:

Jefferson Davis Presidential Library and Museum

The Jefferson Davis Estate Papers

at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The Papers of Jefferson Davis

at

Jefferson Davis

at the Digital Library of Georgia

Jefferson Davis

at ''Encyclopedia Virginia'' (encyclopediavirginia.org) *

Works by Jefferson Davis

at

president of the Confederate States

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Conf ...

from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

and the House of Representatives as a member of the Democratic Party before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He had previously served as the United States Secretary of War from 1853 to 1857 under President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

.

Davis, the youngest of ten children, was born in Fairview, Kentucky. He grew up in Wilkinson County, Mississippi, and also lived in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

. His eldest brother Joseph Emory Davis

Joseph Emory Davis (10 December 1784 – 18 September 1870) was an American lawyer who became one of the wealthiest planters in Mississippi in the antebellum era; he owned thousands of acres of land and was among the nine men in Mississippi who o ...

secured the younger Davis's appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

. After graduating, Jefferson Davis served six years as a lieutenant in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

. He fought in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

(1846–1848) as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. Before the American Civil War, he operated in Mississippi a large cotton plantation which his brother Joseph had given him, and owned as many as 113 slaves. Although Davis argued against secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

in 1858, he believed the states had an unquestionable right to leave the Union.

Davis married Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of general and future President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, in 1835, when he was 27 years old. They were both soon stricken with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, and Sarah died after three months of marriage. Davis recovered slowly and suffered from recurring bouts of illness throughout his life. At the age of 36, Davis married again, to 18-year-old Varina Howell

Varina Anne Banks Howell Davis (May 7, 1826 – October 16, 1906) was the only First Lady of the Confederate States of America, and the longtime second wife of President Jefferson Davis. She moved to a house in Richmond, Virginia, in mid-1861, ...

, a native of Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the county seat of and only city in Adams County, Mississippi, United States. Natchez has a total population of 14,520 (as of the 2020 census). Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, ...

. They had six children.

During the American Civil War, Davis guided Confederate policy and served as its commander in chief. When the Confederacy was defeated in 1865, Davis was captured, accused of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, and imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. He was never tried and was released after two years. Davis's legacy is intertwined with his role as President of the Confederacy. Immediately after the war, he was often blamed for the Confederacy's loss. After he was released, he was seen as a man who suffered unjustly for his commitment to the South, becoming a hero of the pseudohistorical Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Fir ...

during the post-Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, his legacy as Confederate leader was celebrated and memorialized in the South. In the twenty-first century, he is frequently criticized as supporter of slavery and racism, and a number of the memorials created in his honor throughout the country have been removed.

Early life

Birth and family background

Jefferson F. Davis was born at the family homestead in Fairview, Kentucky, on June 3, 1808. Davis, who was named after then-incumbent PresidentThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, was the youngest of ten children born to Jane ( Cook) and Samuel Emory Davis. Samuel Davis's father, Evan, who had a Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

background, came to the colony of Georgia from Philadelphia. Samuel served in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, and for his service received a land grant near what would become Washington, Georgia. He married Jane Cook in 1783, a woman of Scots-Irish descent whom he had met in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

during his military service. Around 1793, Samuel and Jane moved to Kentucky. When Jefferson was born, the family was living in Davisburg, a village Samuel had established that later became Fairview.

Early education

In 1810, the Davis family moved to Bayou Teche. Less than a year later, they moved to a farm near Woodville, Mississippi, where Samuel began cultivating cotton and gradually increased the number of slaves he owned from six in 1810 to twelve. He worked in the fields with his slaves, and eventually built a house, which Jane called Rosemont. During theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, three of Davis's brothers served in the military. When Davis was around five, he received a rudimentary education at a small schoolhouse near Woodville. When he was about eight, his father sent him with a party consisting of Major Thomas Hinds

Thomas Hinds (January 9, 1780August 23, 1840) was an American soldier and politician from the state of Mississippi, who served in the United States Congress from 1828 to 1831.

A hero of the War of 1812, Hinds is best known today as the namesake ...

and his relatives to attend Saint Thomas College

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ortho ...

, a Catholic preparatory school run by Dominicans near Springfield, Kentucky

Springfield is a List of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in and county seat of Washington County, Kentucky, Washington County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,846 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census.

History

Spring ...

. In 1818, Davis returned to Mississippi, where he briefly studied at Jefferson College in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. He then attended the Wilkinson County Academy near Woodville for five years. In 1823, Davis attended Transylvania University in Lexington

Lexington may refer to:

Places England

* Laxton, Nottinghamshire, formerly Lexington

Canada

* Lexington, a district in Waterloo, Ontario

United States

* Lexington, Kentucky, the largest city with this name

* Lexington, Massachusetts, the oldes ...

. While he was still in college in 1824, he learned that his father Samuel had died. Before his death, Samuel had been in debt and had sold Rosemont and his slaves to his eldest son Joseph Emory Davis

Joseph Emory Davis (10 December 1784 – 18 September 1870) was an American lawyer who became one of the wealthiest planters in Mississippi in the antebellum era; he owned thousands of acres of land and was among the nine men in Mississippi who o ...

, who already owned a large plantation along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

in Davis Bend, Mississippi

Davis Bend, Mississippi (now known as Davis Island), was a peninsula named after planter Joseph Emory Davis, who owned most of the property. There he established the 5,000-acre Hurricane Plantation as a model slave community. Davis Bend was abou ...

.

West Point and early military career

Davis's oldest brother Joseph, who was 23 years older than him, took on the role of being his surrogate father. Joseph got Davis appointed to theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point in 1824. He became friends with classmates Albert Sidney Johnson

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

and Leonidas Polk. During his time there, he frequently challenged the academy's discipline. In his first year, he was court-martialed for drinking at a nearby tavern; he was found guilty but was pardoned. In the following year, Davis was placed under house arrest for his role in the Eggnog Riot during Christmas 1826, in which students defied the discipline of superintendent Sylvanus Thayer by getting drunk and disorderly, but was not dismissed. He graduated 23rd in a class of 33.

Following his graduation, Second Lieutenant Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment. In spring 1829, he was stationed at Forts Crawford and Winnebago in Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan. Detroit ...

under the command of Colonel Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, who would later become president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

. While serving in the military, Davis brought James Pemberton, an enslaved African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

that he an inherited from his father, with him as his personal servant. The northern winters were unkind to Davis's health, and one winter he developed a bad case of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

. After his bout with this lung infection, he was vulnerable to catching colds and bronchitis. Davis went to Mississippi on furlough in March 1832, missing the outbreak of the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", cross ...

. Davis returned after the capture of Black Hawk Black Hawk and Blackhawk may refer to:

Animals

* Black Hawk (horse), a Morgan horse that lived from 1833 to 1856

* Common black hawk, ''Buteogallus anthracinus''

* Cuban black hawk, ''Buteogallus gundlachii''

* Great black hawk, ''Buteogallus urub ...

and escorted him for detention in St. Louis. In his autobiography, Black Hawk stated that Jefferson treated him with kindness.

After his return to Fort Crawford in January 1833, he and Taylor's daughter, Sarah, had become romantically involved. Davis asked Taylor if he could marry Sarah, but Taylor refused. In spring, Taylor had him assigned to the United States Regiment of Dragoons under Colonel Henry Dodge

Moses Henry Dodge (October 12, 1782 – June 19, 1867) was a Democratic member to the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate, Territorial Governor of Wisconsin and a veteran of the Black Hawk War. His son, Augustus C. Dodge, served as ...

. Davis was promoted to first lieutenant and deployed at Fort Gibson, Arkansas Territory. In February 1835, he was court-martialed

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

for insubordination. Davis was acquitted, but in the meantime he had requested a furlough. Immediately after his furlough, he tendered his resignation, which was effective on June 30. He was twenty-six years old.

Planting career and first marriage

When Davis returned to Mississippi he decided to become a planter. His brother Joseph was successfully converting his large holdings at Davis Bend, about south of

When Davis returned to Mississippi he decided to become a planter. His brother Joseph was successfully converting his large holdings at Davis Bend, about south of Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat, and the population at the 2010 census was 23,856.

Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vi ...

, into Hurricane Plantation

Hurricane Plantation located near Vicksburg, Mississippi, was the home of Joseph Emory Davis (1784–1870), the oldest brother of Jefferson Davis. Located on a peninsula of the Mississippi River in Warren County, Mississippi, called Davis Bend af ...

, which would eventually have of cultivated fields and over 300 slaves. He gave Davis of his land to start a plantation at Davis Bend, though Joseph retained the title to the property. He also loaned Davis the money to buy ten slaves to clear and cultivate the land, which Jefferson would name Brierfield Plantation

Brierfield Plantation was a large forced-labor cotton farm built in 1847 in Davis Bend, Mississippi, south of Vicksburg and the home of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

History

The use of the plantation, with more than 1,000 acres, w ...

.

Davis had continued his correspondence with Sarah. They agreed to marry, and Taylor gave his implicit assent. Sarah went to Louisville where she had relatives, and Davis traveled on his own to meet her there. They married at Beechland on June 17, 1835. In August, Davis and Sarah traveled south to Locust Grove Plantation, his sister Anna Smith's home in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana

West Feliciana Parish (French: ''Paroisse de Feliciana Ouest''; Spanish: ''Parroquia de West Feliciana'') is a civil parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2010 census, the population was 15,625, and 15,310 at the 2020 census. ...

. Within days, both became severely ill with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

. Sarah died at the age of 21 on September 15, 1835 after only three months of marriage. Davis gradually improved, and briefly traveled to Havana, Cuba

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, to restore his health and returned home via New York and Washington, D.C., where he visited his old schoolmate from Transylvania College, George Wallace Jones.

For several years following Sarah's death, Davis spent much of his time at Brierfield supervising the enslaved workers and developing his plantation. By 1836, he possessed 23 slaves; by 1840, he possessed 40; and by 1860, 113. He made his first slave, James Pemberton, its overseer, a position he held until his death around 1850. Meanwhile, Davis also developed intellectually. Joseph maintained a large library on Hurricane Plantation, allowing Davis to read up on politics, the law, and economics. Joseph, who became particularly concerned with national attempts to limit slavery in new territories during this time, often served as Davis's advisor and facilitator as they increasingly became involved in politics, and Jefferson was the beneficiary of his brother's political influence.

Early political career and second marriage

Davis first became directly involved in politics in 1840 when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg and served as a delegate to the party's state convention in Jackson; he served again in 1842. In November 1843, he was chosen to be the Democratic candidate for the state House of Representatives for Warren County less than one week before the election after the original candidate withdrew his nomination; Davis lost the election. In early 1844, Davis was chosen to serve as a delegate to the state convention again. On his way to Jackson, Davis met Varina Banks Howell, then 18 years old, when he delivered an invitation from Joseph for her to stay at the Hurricane Plantation for the Christmas season. She was a granddaughter of New Jersey GovernorRichard Howell

Richard Howell (October 25, 1754April 28, 1802) was the third governor of New Jersey from 1794 to 1801.

Early life and military career

Howell was born in Newark in the Colony of Delaware. He was a lawyer and soldier of the early United States ...

; her mother's family was from the South. At the convention, Davis was selected as one of Mississippi's six presidential electors for the 1844 presidential election.

Within a month of their meeting, the 35-year-old Davis and Varina became engaged despite her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics. For the remainder of the year, Davis campaigned for the Democratic party, advocating for the nomination of John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

over Martin Van Buren who was the party's original choice. Davis preferred Calhoun because he advocated for southern interests including the annexation of Texas, reduction of tariffs, and building naval defenses in southern ports, but he actively campaigned for James K. Polk when the party chose him as their presidential candidate.

Davis and Varina married on February 26, 1845, after the campaign ended. They had six children: Samuel Emory, born in 1852, who died of an undiagnosed disease two years later; Margaret Howell, born in 1855, who married, raised a family and lived to be 54 years old; Jefferson Davis, Jr., born in 1857, who died of yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

at age 21; Joseph Evan, born 1859, who died from an accidental fall at age five; William Howell, born 1864, who died of diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

at age 10; and Varina Anne, born 1872, who remained single and lived to be 34.

In July 1845, Davis became a candidate for the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. He ran on a platform that emphasized a strict constructionist view of the constitution, states' rights, a reduction of tariffs, and opposition to the creation of a national bank. He won the election and entered the 29th Congress. He argued for the American right to annex Oregon but to do so by peaceful compromise with Great Britain. Davis spoke against the use of federal monies for internal improvements that he believed would undermine the autonomy of the states, and on May 11, 1846, he voted for war with Mexico.

Mexican–American War

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, Mississippi raised a volunteer unit, the First Mississippi Regiment, for the U.S. Army. Davis expressed his interest in joining the regiment if elected its colonel, and in the second round of elections in June 1846 he was chosen and accepted the position; he did not resign his position as a U.S. Representative, but left a letter of resignation with his brother Joseph to submit when he thought it was appropriate.

Davis was able to get his entire regiment armed with new percussion rifles instead of the conventional smoothbore muskets used by other regiments. President Polk had given his approval for their purchase as a political favor in return for Davis marshalling enough votes to pass the Walker Tariff

The Walker Tariff was a set of tariff rates adopted by the United States in 1846. Enacted by the Democrats, it made substantial cuts in the high rates of the "Black Tariff" of 1842, enacted by the Whigs. It was based on a report by Secretary of ...

. Davis was able to arm his entire regiment with the rifles despite the objections of the commanding general of the U.S. Forces, Winfield Scott, who felt that the guns had not been sufficiently tested and deplored the fact that they could not be fitted with bayonets. Because of its association with the regiment, the rifle became known as the " Mississippi rifle", and Davis's regiment became known as the " Mississippi Rifles".

Davis's regiment was assigned to the army of his former father-in-law, Zachary Taylor, in northeastern Mexico. Davis distinguished himself at the Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers and ...

in September by leading a charge that took the fort of La Teneria. He then went on a two-month leave and returned to Mississippi, where he learned that Joseph had submitted his resignation from the House of Representatives in October. Davis returned to Mexico and fought in the Battle of Buena Vista on February 22, 1847. His tactics stopped a flanking attack by the Mexican forces that threatened to collapse the American line, although he was wounded in the heel during the fighting. In May, Polk offered Davis a federal commission as a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

. Davis declined the appointment, arguing he could not directly command militia units because the U.S. Constitution gives the power of appointing militia officers to the states, not the federal government. Instead, Davis accepted an appointment by Mississippi governor Albert G. Brown

Albert Gallatin Brown (May 31, 1813June 12, 1880) was Governor of Mississippi from 1844 to 1848 and a Democratic United States Senator from Mississippi from 1854 to 1861, when he withdrew during secession.

Early life

He was born to Joseph and ...

to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate, which had been vacated by the death of Senator Jesse Speight

Jesse Speight (September 22, 1795May 1, 1847) was a North Carolina and Mississippi politician in the nineteenth century.

Born in Greene County, North Carolina, Speight attended country schools as a child. He was a member of the North Carolina H ...

.

Senator and Secretary of War

Senator

Davis took his seat in December and was appointed as a regent of the

Davis took his seat in December and was appointed as a regent of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

. The Mississippi legislature confirmed his appointment in January 1848. He quickly established himself as an advocate of the South and its expansion into the territories of the West. He was against the Wilmot Proviso, which was intended to assure that any territory acquired by Mexico would be free of slavery. He asserted that only states had sovereignty, and that territories did not. According to Davis, territories were the common property of the United States and Americans who owned slaves had as much right to move into the new territories with their slaves as other Americans. Davis tried to amend the Oregon Bill that established Oregon as a territory to allow settlers to bring their slaves. Davis did not want to accept the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican–American War claiming that Nicholas Trist, who negotiated the treaty, had done so as a private citizen and not a government representative; he argued to have the treaty to cede additional land to the United States.

During the 1848 presidential election, Davis did very little campaigning because he did not want to campaign against his former father-in-law and commanding officer, Zachary Taylor, who was the Whig candidate. The Senate session following Taylor's inauguration in 1849 was a brief one that only lasted until March 1849. Davis was able to return to Brierfield for seven months. He was reelected by the state legislature for another six-year term in the Senate, and during this time, he was approached by the Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López to lead a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

expedition to liberate Cuba from Spain. Davis turned down the offer, saying it was inconsistent with his duty as a senator.

After the death of Calhoun in the spring of 1850, Davis became the senatorial spokesperson for the South. During 1850, Congress debated the resolutions of Henry Clay. These resolutions aimed to address the sectional and territorial problems of the nation and would form the basis for the Compromise of 1850. Davis was against the resolutions, as he felt they would put the South at a political disadvantage. For example, one of the first issues for discussion in early 1850 was the admission of California as a free state without its first becoming a territory. Davis countered that Congress should establish a territorial government for California, which would give Southerners the right to colonize the territory with their slaves as well. He suggested that extending the Missouri Compromise Line

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas to th ...

, which defined which territories were open to slavery, to the Pacific was acceptable, arguing that the region south of the line was favorable for the expansion of slavery. He stated that not allowing slavery into the new territories would deny the political equality of Southerners, and that it would destroy the balance of power between Northern and Southern states in the Senate.

Davis continued to oppose the Compromise of 1850 after it passed. In the autumn of 1851, he was nominated to run for governor of Mississippi on a states' rights platform against Henry Stuart Foote

Henry Stuart Foote (February 28, 1804May 19, 1880) was a United States Senator from Mississippi and the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations from 1847 to 1852. He was a Unionist Governor of Mississippi from 1852 to ...

, who had favored the compromise. Davis accepted the nomination and resigned from the Senate. Foote won the election by a slim margin. Davis, who no longer held a political office, turned down reappointment to his seat by outgoing Governor James Whitfield. He would spend much of the next fifteen months at Brierfield. He remained politically active, attending the Democratic convention in January 1852 and campaigning for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

and William R. King during the presidential election of 1852.

Secretary of War

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his Secretary of War. Davis championed a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific, arguing it was needed for national defense, and was entrusted with overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys to determine which of four possible routes was the best. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his Secretary of War. Davis championed a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific, arguing it was needed for national defense, and was entrusted with overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys to determine which of four possible routes was the best. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

from Mexico, partly because he preferred a southern route for the new railroad; the Pierce administration agreed and the land was purchased in December 1853. Davis presented the surveys' findings in 1855, but they failed to clarify which route was best, and sectional problems arising with any attempt to choose one made constructing the railroad impossible at the time. Davis also advocated for the acquisition of Cuba from Spain, seeing it as an opportunity to add the island, a strategic military location, as another slave state to the Union. He felt the size of the regular army was insufficient to fulfill its mission and that salaries would have to be increased, something which had not occurred for 25 years. Congress agreed, adding four regiments, which increased the army's size from about 11,000 to about 15,000 soldiers, and raising its pay scale. He ended the manufacture of smoothbore muskets for the military and shifted production to rifles, and worked to develop the tactics that would go with them. He oversaw the building of public works in Washington D.C., including federal buildings and the initial construction of the Washington Aqueduct.

Davis helped get the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854 by allowing President Pierce to endorse it before it came up for a vote. This bill, which created Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

territories, explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

's limits on slavery and left the decision about a territory's slaveholding status to popular sovereignty, which allowed the territory's residents to decide. The passage of this bill led to the demise of the Whig party, the rise of the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

and civil violence in the Kansas Territory. The Democratic nomination for the 1856 presidential election went to James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

. Knowing his term was over when the Pierce administration ended in 1857, Davis ran for Senate once more, was elected, and re-entered it on March 4, 1857. In the same month, the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

decided the Dred Scott case

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; t ...

, which ruled that slavery could not be barred from any territory.

Return to Senate

The Senate recessed in March and did not reconvene until November 1857. The session opened with the Senate debating the Lecompton Constitution submitted by a convention in Kansas territory that would allow it to be admitted as a slave state. The issue divided the Democratic Party. Davis supported it, but it was not passed, in part because the leading Democrat in the North, Stephen Douglas, refused to support its passage because he felt it did not represent the true will of the settlers in Kansas. The controversy further undermined the alliance between northern and southern Democrats.

Davis's participation in the Senate was interrupted by a severe illness in early 1858. Davis, who regularly suffered from ill health, had a recurring case of iritis, which threatened the loss of his left eye and left him bedridden for seven weeks. He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. While recovering, he gave speeches in Maine, Boston, and New York, emphasizing the common heritage of all Americans and the importance of the constitution for defining the nation. Because his speeches had angered some states' rights supporters in the South, Davis was required to clarify his comments when he returned to Mississippi. He stated that he felt positively about the benefits of Union, but acknowledged that the Union could be dissolved if states' rights were violated and one section of the country imposed its will on another. Speaking to the Mississippi Legislature on November 16, 1858, Davis stated "if an Abolitionist be chosen President of the United States... I should deem it your duty to provide for your safety outside of a Union with those who have already shown the will...to deprive you of your birthright and to reduce you to worse than the colonial dependence of your fathers."

In February 1860, Davis presented a series of resolutions defining the relationship between the states under the constitution, including the assertion that Americans had a constitutional right to bring slaves into territories. These resolutions were seen as setting the agenda for the Democratic Party nomination, ensuring that Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty, known as the Freeport Doctrine, would be excluded from the party platform. At the Democratic convention, the party split: Douglas was nominated by the Northern half and Vice President John C. Breckinridge was nominated by the Southern half. The Republican Party nominee

The Senate recessed in March and did not reconvene until November 1857. The session opened with the Senate debating the Lecompton Constitution submitted by a convention in Kansas territory that would allow it to be admitted as a slave state. The issue divided the Democratic Party. Davis supported it, but it was not passed, in part because the leading Democrat in the North, Stephen Douglas, refused to support its passage because he felt it did not represent the true will of the settlers in Kansas. The controversy further undermined the alliance between northern and southern Democrats.

Davis's participation in the Senate was interrupted by a severe illness in early 1858. Davis, who regularly suffered from ill health, had a recurring case of iritis, which threatened the loss of his left eye and left him bedridden for seven weeks. He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. While recovering, he gave speeches in Maine, Boston, and New York, emphasizing the common heritage of all Americans and the importance of the constitution for defining the nation. Because his speeches had angered some states' rights supporters in the South, Davis was required to clarify his comments when he returned to Mississippi. He stated that he felt positively about the benefits of Union, but acknowledged that the Union could be dissolved if states' rights were violated and one section of the country imposed its will on another. Speaking to the Mississippi Legislature on November 16, 1858, Davis stated "if an Abolitionist be chosen President of the United States... I should deem it your duty to provide for your safety outside of a Union with those who have already shown the will...to deprive you of your birthright and to reduce you to worse than the colonial dependence of your fathers."

In February 1860, Davis presented a series of resolutions defining the relationship between the states under the constitution, including the assertion that Americans had a constitutional right to bring slaves into territories. These resolutions were seen as setting the agenda for the Democratic Party nomination, ensuring that Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty, known as the Freeport Doctrine, would be excluded from the party platform. At the Democratic convention, the party split: Douglas was nominated by the Northern half and Vice President John C. Breckinridge was nominated by the Southern half. The Republican Party nominee Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

won the 1860 election.

Davis counselled moderation, but South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860, and Mississippi did so on January 9, 1861. Davis had expected this but waited until he received official notification. Calling January 21 "the saddest day of my life", Davis delivered a farewell address to the United States Senate, resigned, and returned to Mississippi.

President of the Confederate States

Inauguration

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Mississippi Governor

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus

John Jones Pettus (October 9, 1813January 25, 1867) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the 23rd Governor of Mississippi, from 1859 to 1863. Before being elected in his own right to full gubernatorial terms in 1859 and 1861, he ...

informing him that he was available to serve the state. On January 27, 1861, Pettus appointed him a major general of Mississippi's army. On February 10, Davis learned that he had been unanimously elected to the provisional presidency of the Confederacy by a constitutional convention in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County, Alabama, Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the Gulf Coastal Plain, coas ...

, which consisted of delegates from the six states that had seceded: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

, Georgia, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

. Davis was chosen because of his political prominence, his military reputation, and his moderate approach to secession, which could bring Unionists and undecided voters over to his side. Davis had been hoping for a military command, but he accepted and committed himself fully to his new role. Davis and Vice President Alexander H. Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death in ...

were inaugurated on February 18. The procession for the inauguration started at Montgomery's Exchange Hotel, the location of the Confederate administration and Davis's residence.

Davis then formed his cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

, choosing one member from each of the states of the Confederacy, including Texas which had recently seceded: Robert Toombs of Georgia for Secretary of State, Christopher Memminger

Christopher Gustavus Memminger (german: link=no, Christoph Gustav Memminger, translit=Christopher Gustavus Memminger; January 9, 1803 – March 7, 1888) was a German-born American politician and a secessionist who participated in the format ...

of South Carolina for Secretary of the Treasury, LeRoy Walker of Alabama for Secretary of War, John Reagan of Texas for Postmaster General, Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana for Attorney General, and Stephen Mallory of Florida for Secretary of the Navy. Davis stood in for Mississippi. The Confederate Congress quickly confirmed Davis's choices. During his time as president, Davis's cabinet often changed; there were fourteen different appointees for the positions, including six secretaries of war.

Civil War

As the Southern states seceded, state authorities had been able to take over most federal facilities without bloodshed. But four forts— Fort Sumter in

As the Southern states seceded, state authorities had been able to take over most federal facilities without bloodshed. But four forts— Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal c ...

, and two in the Florida Keys—had not surrendered. Davis preferred to avoid a crisis as he realized the Confederacy was still weak and needed time to organize its resources. In February, the Confederate Congress advised Davis to send a commission to Washington to negotiate the settlement of all disagreements with the United States, including the evacuation of the Federal forts. Davis did so and was willing to consider compensation, but President of the United States Lincoln refused to meet with the commissioners. Instead, they informally negotiated with Secretary of State William Seward through an intermediary, Supreme Court Justice John A. Campbell. Seward hinted that Fort Sumter would be evacuated, but gave no assurance.

In the meantime, Davis appointed Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard to command all Confederate troops in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina, to ensure that no assault was launched without his direct orders. After being informed by Lincoln that he intended to resupply Fort Sumter with provisions, Davis convened with the Confederate Congress on April 8 and then gave orders to Beauregard to demand the immediate surrender of the fort or to reduce it. The commander of the fort, Major Robert Anderson, refused to surrender, and Beauregard began the attack on Fort Sumter in the early dawn of April 12. After over thirty hours of bombardment, the fort surrendered. The Confederates occupied it on April 14. When Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, four more states–Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

—joined the Confederacy. The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

had begun.

1861

In addition to being the constitutional commander-in-chief of the Confederacy, Davis was operational leader of the military, as the Confederacy's military departments reported directly to him. Davis had a habit of overworking, particularly in minor military issues that could have been delegated. Some of his colleagues—such as Generals Joseph E. Johnston and his friend from West Point, Major General Leonidas Polk—encouraged him to lead the armies directly, but he let his generals direct the combat.

The major fighting in the East began when a Union army advanced into Northern Virginia in July 1861. It was defeated at Manassas by two Confederate forces commanded by Beauregard and Joseph Johnston. After the battle, Davis had to manage disagreements with the two generals: Beauregard, who was now a full general, was upset because he felt he was not given sufficient credit for his ideas; Joseph Johnston was upset because he felt he was not given the seniority of rank due to him.

In the West, Davis had to address another issue caused by one of his generals.

In addition to being the constitutional commander-in-chief of the Confederacy, Davis was operational leader of the military, as the Confederacy's military departments reported directly to him. Davis had a habit of overworking, particularly in minor military issues that could have been delegated. Some of his colleagues—such as Generals Joseph E. Johnston and his friend from West Point, Major General Leonidas Polk—encouraged him to lead the armies directly, but he let his generals direct the combat.

The major fighting in the East began when a Union army advanced into Northern Virginia in July 1861. It was defeated at Manassas by two Confederate forces commanded by Beauregard and Joseph Johnston. After the battle, Davis had to manage disagreements with the two generals: Beauregard, who was now a full general, was upset because he felt he was not given sufficient credit for his ideas; Joseph Johnston was upset because he felt he was not given the seniority of rank due to him.

In the West, Davis had to address another issue caused by one of his generals. Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...