The surrender of the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

was

announced by

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

on 15 August and formally

signed on 2 September 1945,

bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) had become incapable of conducting major operations and an

Allied invasion of Japan was imminent. Together with the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

called for the

unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

of the Japanese armed forces in the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

on 26 July 1945—the alternative being "prompt and utter destruction". While publicly stating their intent to fight on to the bitter end, Japan's leaders (the

Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, also known as the "Big Six") were privately making entreaties to the publicly neutral

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

to mediate peace on terms more favorable to the Japanese. While maintaining a sufficient level of diplomatic engagement with the Japanese to give them the impression they might be willing to mediate, the Soviets were covertly preparing to attack Japanese forces in

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

and

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

(in addition to

South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

and the

Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese language, Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakh ...

) in fulfillment of promises they had secretly made to the United States and the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

at the

Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

and

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

s.

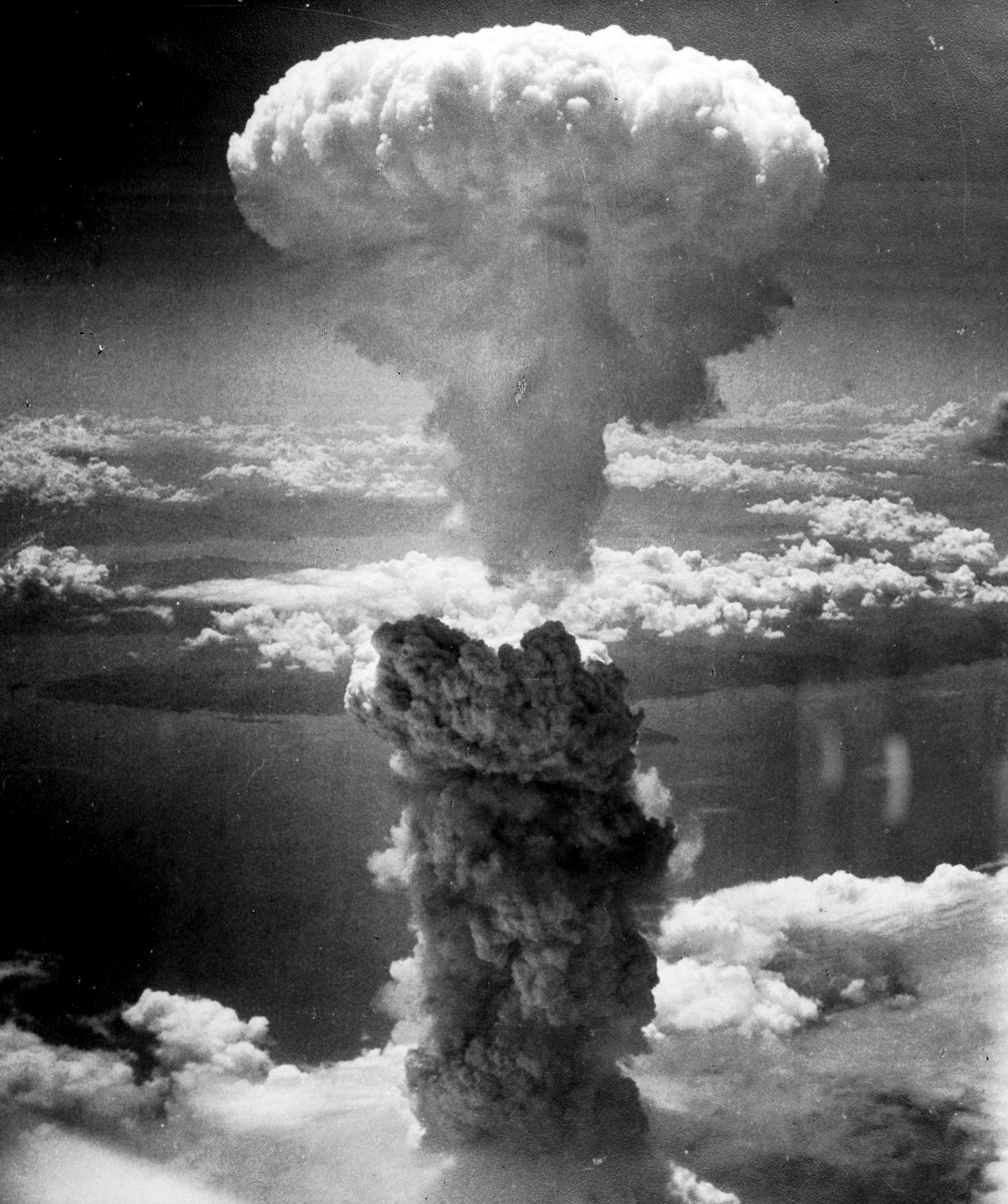

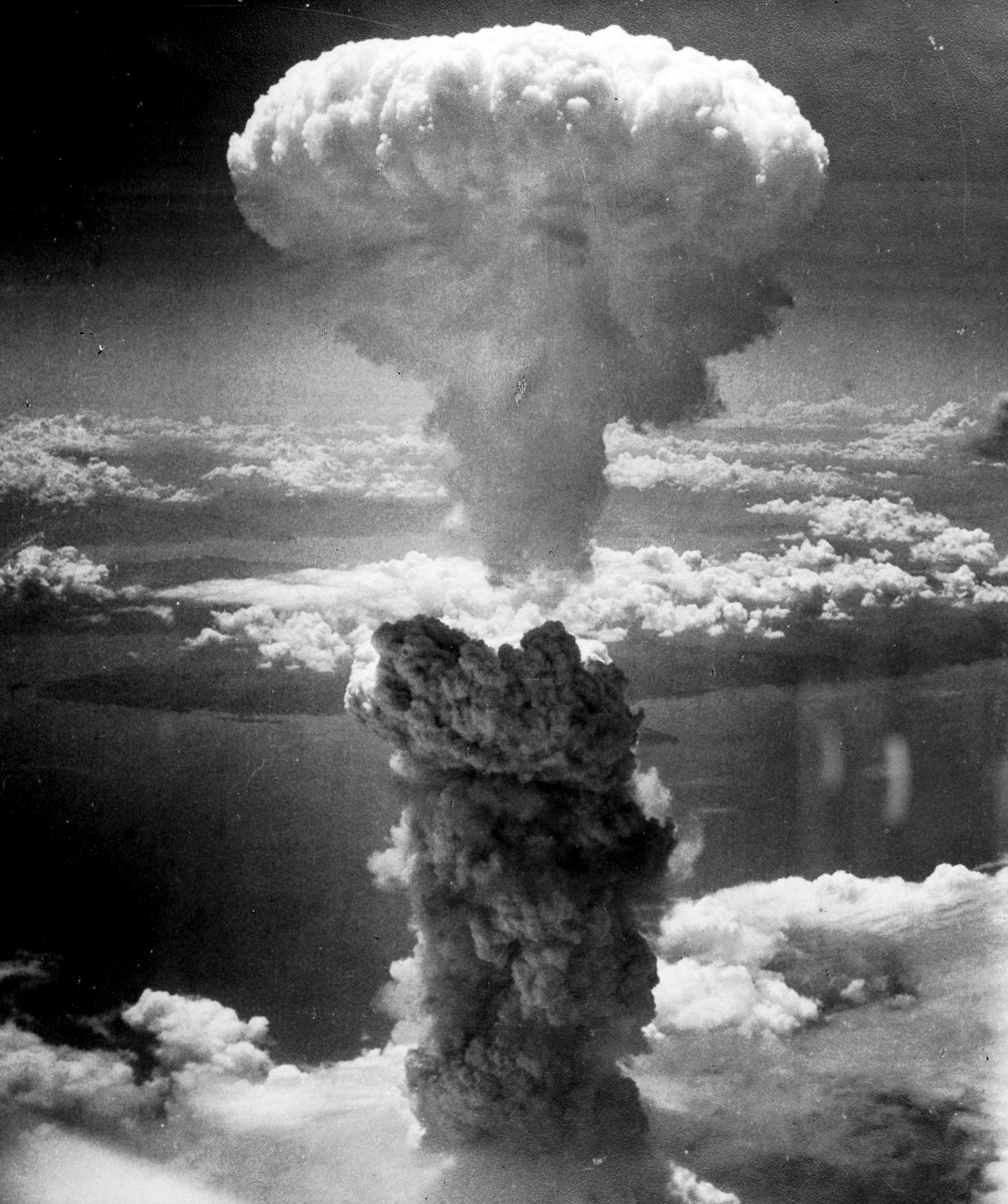

On 6 August 1945, at 8:15 AM local time, the United States

detonated an

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

over the Japanese city of

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

. Sixteen hours later, American President

Harry S. Truman called again for Japan's surrender, warning them to "expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth." Late in the evening of 8 August 1945, in accordance with the Yalta agreements, but in violation of the

Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II ...

, the

Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and soon after midnight on 9 August 1945, the

Soviet Union invaded the Imperial Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Hours later, the United States

dropped a second atomic bomb, this time on the Japanese city of

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

. Following these events,

Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

intervened and ordered the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War to accept the terms the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

had set down in the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

for ending the war. After several more days of behind-the-scenes negotiations and

a failed ''coup d'état'', Emperor Hirohito gave a recorded

radio address across the Empire on 15 August announcing the surrender of Japan to the Allies.

On 28 August, the

occupation of Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the victorious Allies of World War II from the 1945 surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of the war until the

Treaty of San Francisco took effect in 1952. The occupation, led by the United States ...

led by the

Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milit ...

began. The surrender ceremony was held on 2 September, aboard the United States Navy battleship , at which officials from the

Japanese government

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, ...

signed the

Japanese Instrument of Surrender

The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that formalized the surrender of the Empire of Japan, marking the end of hostilities in World War II. It was signed by representatives from the Empire of Japan and from the Allied ...

, thereby ending the hostilities. Allied

civilian

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not " combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant ...

s and

military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank ( officer, non-commissioned office ...

alike celebrated

V-J Day, the end of the war; however, isolated soldiers and personnel from Japan's far-flung forces throughout

Asia and the Pacific refused to surrender for months and years afterwards, some even refusing into the 1970s. The role of the atomic bombings in Japan's unconditional surrender, and

the ethics of the two attacks, is

still debated. The state of war formally ended when the

Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

came into force on 28 April 1952. Four more years passed before Japan and the Soviet Union signed the

Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956, which formally brought an end to their state of war.

Background

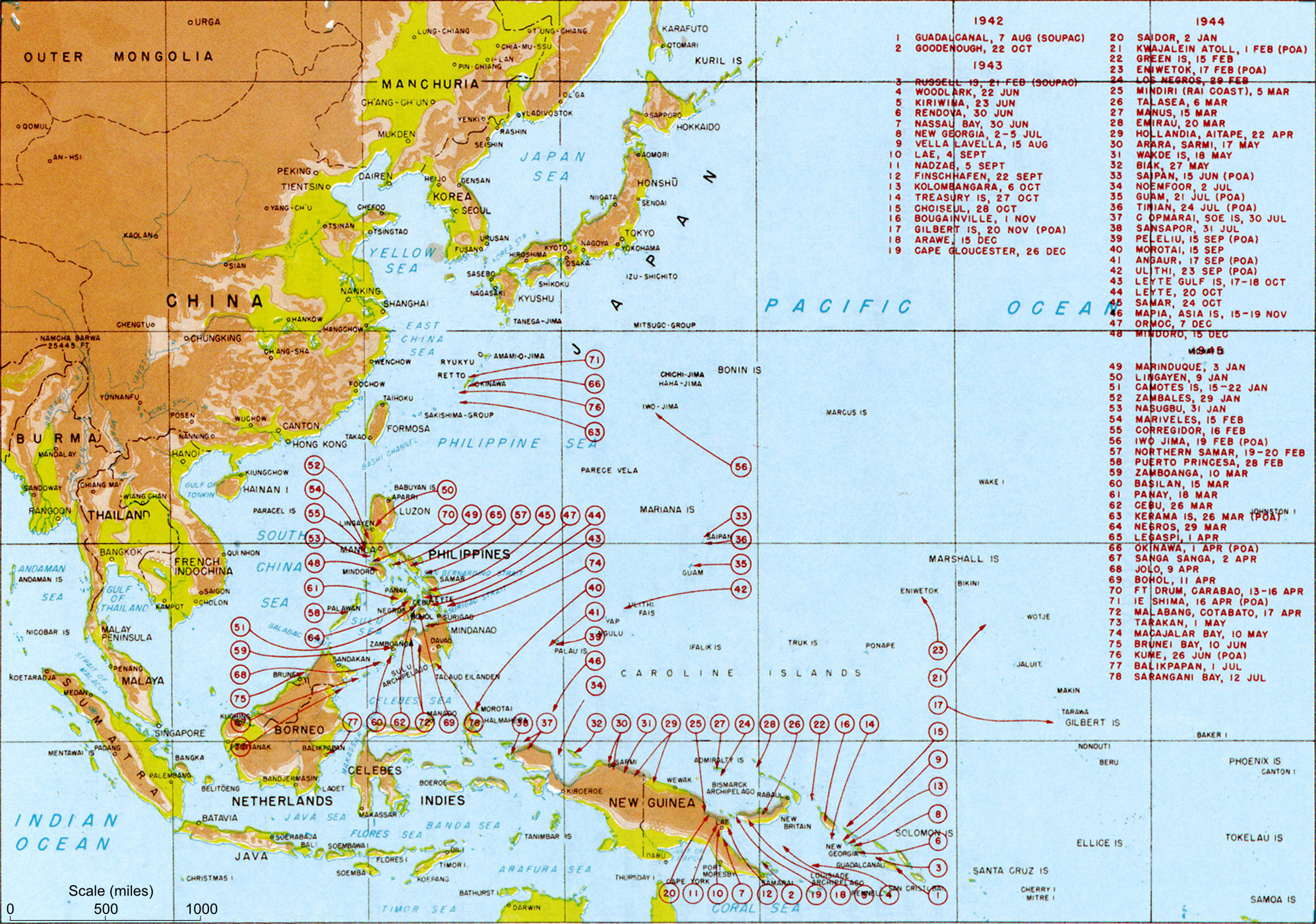

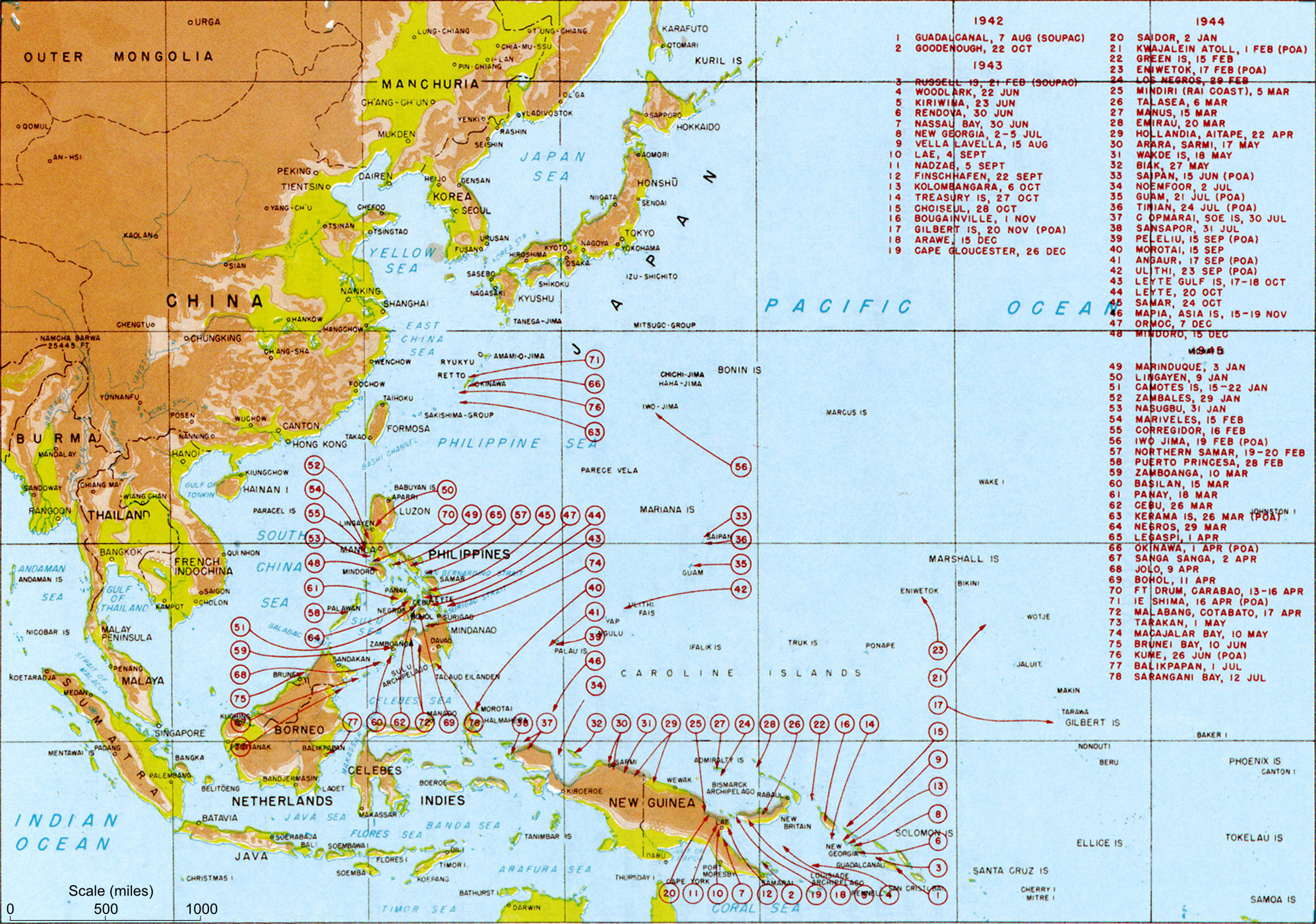

By 1945, the Japanese had suffered a string of defeats for nearly two years in the

South West Pacific

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million as of ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, the

Marianas campaign

The Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, also known as Operation Forager, was an offensive launched by United States forces against Imperial Japanese forces in the Mariana Islands and Palau in the Pacific Ocean between June and November 1944 d ...

, and the

Philippines campaign. In July 1944, following the

loss of Saipan, General

Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assista ...

was replaced as

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

by General

Kuniaki Koiso

was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army, Governor-General of Korea and Prime Minister of Japan from 1944 to 1945.

After Japan's defeat in World War II, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early l ...

, who declared that the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

would be the site of the decisive battle.

After the Japanese loss of the Philippines, Koiso in turn was replaced by Admiral

Kantarō Suzuki. The Allies captured the nearby islands of

Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima (, also ), known in Japan as , is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands and lies south of the Bonin Islands. Together with other islands, they form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The highest point of Iwo Jima is Mount Suribachi at high.

...

and

Okinawa

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 Square kilometre, km2 (880 sq mi).

...

in the first half of 1945. Okinawa was to be a

staging area for

Operation Downfall

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

, the Allied invasion of the Japanese

Home Islands. Following

Germany's defeat, the Soviet Union began quietly redeploying its battle-hardened forces from the European theatre to the Far East, in addition to about forty divisions that had been stationed there

since 1941, as a counterbalance to the million-strong

Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

.

The

Allied submarine campaign and the

mining of Japanese coastal waters had largely destroyed the Japanese merchant fleet. With few natural resources, Japan was dependent on raw materials, particularly oil, imported from Manchuria and other parts of the East Asian mainland, and from the conquered territory in the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

. The destruction of the Japanese merchant fleet, combined with the

strategic bombing of Japanese industry, had wrecked Japan's war economy. Production of coal, iron, steel, rubber, and other vital supplies was only a fraction of that before the war.

As a result of the losses it had suffered, the

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) had ceased to be an effective fighting force. Following

a series of raids on the

Japanese shipyard at Kure, the only major warships in somewhat fighting order were six aircraft carriers, four cruisers, and one battleship, of which many were heavily damaged and none could be fueled adequately. Although 19 destroyers and 38 submarines were still operational, their use was also limited by the lack of fuel.

[.]

Defense preparations

Faced with the prospect of an invasion of the Home Islands, starting with

Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

, and the prospect of a Soviet invasion of Manchuria—Japan's last source of natural resources—the War Journal of the Imperial Headquarters concluded in 1944:

As a final attempt to stop the Allied advances, the Japanese Imperial High Command planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū codenamed

Operation Ketsugō

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

. This was to be a radical departure from the

defense in depth

Defence in depth (also known as deep defence or elastic defence) is a military strategy that seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating ...

plans used in the invasions of

Peleliu

Peleliu (or Beliliou) is an island in the island nation of Palau. Peleliu, along with two small islands to its northeast, forms one of the sixteen states of Palau. The island is notable as the location of the Battle of Peleliu in World War II.

H ...

,

Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima (, also ), known in Japan as , is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands and lies south of the Bonin Islands. Together with other islands, they form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The highest point of Iwo Jima is Mount Suribachi at high.

...

, and

Okinawa

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 Square kilometre, km2 (880 sq mi).

...

. Instead, everything was staked on the beachhead; more than 3,000

kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending ...

s would be sent to attack the amphibious transports before troops and cargo were disembarked on the beach.

If this did not drive the Allies away, they planned to send another 3,500 kamikazes along with 5,000

''Shin'yō'' suicide motorboats and the remaining destroyers and submarines—"the last of the Navy's operating fleet"—to the beach. If the Allies had fought through this and successfully landed on Kyūshū, 3,000 planes would have been left to defend the remaining islands, although Kyūshū would be "defended to the last" regardless.

The strategy of making a last stand at Kyūshū was based on the assumption of continued Soviet neutrality.

Supreme Council for the Direction of the War

Japanese policy-making centered on the

Supreme Council for the Direction of the War (created in 1944 by earlier Prime Minister

Kuniaki Koiso

was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army, Governor-General of Korea and Prime Minister of Japan from 1944 to 1945.

After Japan's defeat in World War II, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early l ...

), the so-called "Big Six"—the

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

,

Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

,

Minister of the Army,

Minister of the Navy Minister of the Navy may refer to:

* Minister of the Navy (France)

* Minister of the Navy (Italy)

* Minister of the Navy (Japan)

* Minister of the Navy (Netherlands)

* Minister of the Navy (Spain)

* Minister of the Navy (Turkey)

* Minister of ...

, Chief of the

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

General Staff, and Chief of the

Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

General Staff. At the formation of the Suzuki government in April 1945, the council's membership consisted of:

* Prime Minister: Admiral

Kantarō Suzuki

* Minister of Foreign Affairs:

Shigenori Tōgō

* Minister of the Army: General

Korechika Anami

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II who was War Minister during the surrender of Japan.

Early life and career

Anami was born in Taketa city in Ōita Prefecture, where his father was a senior bureaucrat in the Home M ...

* Minister of the Navy: Admiral

Mitsumasa Yonai

was a Japanese general and politician. He served as admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Minister of the Navy, and Prime Minister of Japan in 1940.

Early life and career

Yonai was born on 2 March 1880, in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, the firs ...

* Chief of the Army General Staff: General

Yoshijirō Umezu

* Chief of the Navy General Staff: Admiral

Koshirō Oikawa

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy and Naval Minister during World War II.

Biography

Oikawa was born into a wealthy family in rural Koshi County, Niigata Prefecture, but was raised in Morioka city, Iwate prefecture in northern Ja ...

(later replaced by Admiral

Soemu Toyoda)

All of these positions were nominally appointed by the Emperor and their holders were answerable directly to him. Nevertheless, Japanese civil law from 1936 required that the Army and Navy ministers had to be active duty flag officers from those respective services while Japanese military law from long before that time prohibited serving officers from accepting political offices without first obtaining permission from their respective service headquarters which, if and when granted, could be rescinded at any time. Thus, the Japanese Army and Navy effectively held a legal right to nominate (or refuse to nominate) their respective ministers, in addition to the effective right to order their respective ministers to resign their posts.

Strict constitutional convention dictated (as it technically still does today) that a prospective Prime Minister could not assume the premiership, nor could an incumbent Prime Minister remain in office, if he could not fill all of the cabinet posts. Thus, the Army and Navy could prevent the formation of undesirable governments, or by resignation bring about the collapse of an existing government.

Emperor

Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

and

Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Kōichi Kido also were present at some meetings, following the Emperor's wishes. As

Iris Chang

Iris Shun-Ru Chang (March 28, 1968November 9, 2004) was a Chinese American journalist, author of historical books and political activist. She is best known for her best-selling 1997 account of the Nanking Massacre, '' The Rape of Nanking'', and ...

reports, "... the Japanese deliberately destroyed, hid or falsified most of their secret wartime documents before General MacArthur arrived."

Japanese leadership divisions

For the most part, Suzuki's military-dominated cabinet favored continuing the war. For the Japanese, surrender was unthinkable—Japan had never been successfully invaded or lost a war in its history. Only Mitsumasa Yonai, the Navy minister, was known to desire an early end to the war. According to historian

Richard B. Frank:

After the war, Suzuki and others from his government and their apologists claimed they were secretly working towards peace, and could not publicly advocate it. They cite the Japanese concept of ''

haragei''—"the art of hidden and invisible technique"—to justify the dissonance between their public actions and alleged behind-the-scenes work. However, many historians reject this.

Robert J. C. Butow wrote:

Japanese leaders had always envisioned a negotiated settlement to the war. Their prewar planning expected a rapid expansion and consolidation, an eventual conflict with the United States, and finally a settlement in which they would be able to retain at least some new territory they had conquered. By 1945, Japan's leaders were in agreement that the war was going badly, but they disagreed over the best means to negotiate its end. There were two camps: the so-called "peace" camp favored a diplomatic initiative to persuade

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, the leader of the Soviet Union, to mediate a settlement between the Allies and Japan; and the hardliners who favored fighting one last "decisive" battle that would inflict so many casualties on the Allies that they would be willing to offer more lenient terms.

Both approaches were based on Japan's experience in the

Russo–Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, forty years earlier, which consisted of a series of costly but largely indecisive battles, followed by the decisive naval

Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (Japanese:対馬沖海戦, Tsushimaoki''-Kaisen'', russian: Цусимское сражение, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known as the Battle of Tsushima Strait and the Naval Battle of Sea of Japan (Japanese: 日 ...

.

In February 1945, Prince

Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

gave Emperor Hirohito a memorandum analyzing the situation, and told him that if the war continued, the

imperial family might be in greater danger from an internal revolution than from defeat. According to the diary of

Grand Chamberlain

A chamberlain (Medieval Latin: ''cambellanus'' or ''cambrerius'', with charge of treasury ''camerarius'') is a senior royal official in charge of managing a royal household. Historically, the chamberlain superintends the arrangement of domestic ...

Hisanori Fujita

was a Japanese admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, court official and Shinto priest. After retiring from active service, he served as Chief Priest of Meiji Shrine and the Grand Chamberlain to Emperor Shōwa during World War II.

Biography

...

, the Emperor, looking for a decisive battle (), replied that it was premature to seek peace "unless we make one more military gain". Also in February, Japan's treaty division wrote about Allied policies towards Japan regarding "unconditional surrender, occupation, disarmament, elimination of militarism, democratic reforms, punishment of war criminals, and the status of the emperor." Allied-imposed disarmament, Allied punishment of Japanese war criminals, and especially occupation and removal of the Emperor, were not acceptable to the Japanese leadership.

On 5 April, the Soviet Union gave the required 12 months' notice that it would not renew the five-year

Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II ...

[Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact](_blank)

13 April 1941. (Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

)

Declaration Regarding Mongolia

13 April 1941. (Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

) (which had been signed in 1941 following the

Nomonhan Incident

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, Jap ...

).

Soviet Denunciation of the Pact with Japan

'. Avalon Project, Yale Law School. Text from United States Department of State Bulletin Vol. XII, No. 305, 29 April 1945. Retrieved 22 February 2009. Unknown to the Japanese, at the

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

in November–December 1943, it had been agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once Germany was defeated. At the

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

in February 1945, the United States had made substantial concessions to the Soviets to secure a promise that they would declare war on Japan within three months of the surrender of Germany. Although the five-year Neutrality Pact did not expire until 5 April 1946, the announcement caused the Japanese great concern, because Japan had amassed its forces in the South to repel the inevitable US attack, thus leaving its Northern islands vulnerable to Soviet invasion.

["Molotov's note was neither a declaration of war nor, necessarily, of intent to go to war. Legally, the treaty still had a year to run after the notice of cancellation. But the Foreign Commissar's tone suggested that this technicality might be brushed aside at Russia's convenience."]

So Sorry, Mr. Sato

. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'', 16 April 1945. Soviet Foreign Minister

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

, in Moscow, and

Yakov Malik

Yakov Alexandrovich Malik (russian: Яков Александрович Малик) (11 February 1980) was a Soviet diplomat.

Biography

Born in Ostroverkhovka village, Kharkov Governorate, Malik was educated at Kharkiv Institute of National ...

, Soviet ambassador in Tokyo, went to great lengths to assure the Japanese that "the period of the Pact's validity has not ended".

At a series of high-level meetings in May, the Big Six first seriously discussed ending the war, but none of them on terms that would have been acceptable to the Allies. Because anyone openly supporting Japanese surrender risked assassination by zealous army officers, the meetings were closed to anyone except the Big Six, the Emperor, and the Privy Seal. No second or third-echelon officers could attend. At these meetings, despite the dispatches from Japanese ambassador

Satō

is the most common Japanese surname, often romanized as Sato, Satoh or Satou. A less common variant is . Notable people with the surname include:

*, Japanese actress and voice actress

*, Japanese actress

*, Japanese judoka

*, Japanese writer

* ...

in Moscow, only Foreign Minister Tōgō realized that Roosevelt and Churchill might have already made concessions to Stalin to bring the Soviets into the war against Japan. Tōgō had been outspoken about ending the war quickly. As a result of these meetings, he was authorized to approach the Soviet Union, seeking to maintain its neutrality, or (despite the very remote probability) to form an alliance.

In keeping with the custom of a new government declaring its purposes, following the May meetings the Army staff produced a document, "The Fundamental Policy to Be Followed Henceforth in the Conduct of the War," which stated that the Japanese people would fight to extinction rather than surrender. This policy was adopted by the Big Six on 6 June. (Tōgō opposed it, while the other five supported it.) Documents submitted by Suzuki at the same meeting suggested that, in the diplomatic overtures to the USSR, Japan adopt the following approach:

On 9 June, the Emperor's confidant Marquis

Kōichi Kido wrote a "Draft Plan for Controlling the Crisis Situation," warning that by the end of the year Japan's ability to wage modern war would be extinguished and the government would be unable to contain civil unrest. "... We cannot be sure we will not share the fate of Germany and be reduced to adverse circumstances under which we will not attain even our supreme object of safeguarding the Imperial Household and preserving the national polity." Kido proposed that the Emperor take action, by offering to end the war on "very generous terms." Kido proposed that Japan withdraw from the formerly European colonies it had occupied provided they were granted independence and also proposed that Japan recognize the independence of the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, which Japan had already mostly lost control of and to which it was well known that the U.S. had long been planning to grant independence. Finally, Kido proposed that Japan disarm provided this not occur under Allied supervision and that Japan for a time be "content with minimum defense." Kido's proposal did not contemplate Allied occupation of Japan, prosecution of war criminals or substantial change in Japan's system of government, nor did Kido suggest that Japan might be willing to consider relinquishing territories acquired prior to 1937 including

Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is an island country located in East Asia. The main island of Taiwan, formerly known in the Western political circles, press and literature as Formosa, makes up 99% of the land area of the territori ...

,

Karafuto

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

,

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

, the formerly

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

islands in the Pacific and even

Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

. With the Emperor's authorization, Kido approached several members of the

Supreme Council, the "Big Six." Tōgō was very supportive. Suzuki and Admiral

Mitsumasa Yonai

was a Japanese general and politician. He served as admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Minister of the Navy, and Prime Minister of Japan in 1940.

Early life and career

Yonai was born on 2 March 1880, in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, the firs ...

, the

Navy minister, were both cautiously supportive; each wondered what the other thought. General

Korechika Anami

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II who was War Minister during the surrender of Japan.

Early life and career

Anami was born in Taketa city in Ōita Prefecture, where his father was a senior bureaucrat in the Home M ...

, the

Army minister, was ambivalent, insisting that diplomacy must wait until "after the United States has sustained heavy losses" in

Operation Ketsugō

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

.

In June, the Emperor lost confidence in the chances of achieving a military victory. The

Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

was lost, and he learned of the weakness of the Japanese army in China, of the

Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

in Manchuria, of the navy, and of the army defending the Home Islands. The Emperor received a report by

Prince Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince Hi ...

from which he concluded that "it was not just the coast defense; the divisions reserved to engage in the decisive battle also did not have sufficient numbers of weapons."

According to the Emperor:

On 22 June, the Emperor summoned the Big Six to a meeting. Unusually, he spoke first: "I desire that concrete plans to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and that efforts made to implement them." It was agreed to solicit Soviet aid in ending the war. Other neutral nations, such as

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

,

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

, and the

Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

, were known to be willing to play a role in making peace, but they were so small they were believed unable to do more than deliver the Allies' terms of surrender and Japan's acceptance or rejection. The Japanese hoped that the Soviet Union could be persuaded to act as an agent for Japan in negotiations with the United States and Britain.

Manhattan Project

After several years of preliminary research, President

Franklin D. Roosevelt had authorized the initiation of a massive, top-secret project to build

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s in 1942. The

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, under the authority of Major General

Leslie R. Groves Jr. employed hundreds of thousands of American workers at dozens of secret facilities across the United States, and on 16 July 1945, the first prototype weapon was detonated during the

Trinity nuclear test.

As the project neared its conclusion, American planners began to consider the use of the bomb. In keeping with the Allies' overall strategy of securing final victory in Europe first, it had initially been assumed that the first atomic weapons would be allocated for use against Germany. However, by this time it was increasingly obvious that Germany would be defeated before any bombs would be ready for use. Groves formed a committee that met in April and May 1945 to draw up a list of targets. One of the primary criteria was that the target cities must not have been damaged by conventional bombing. This would allow for an accurate assessment of the damage done by the atomic bomb.

The targeting committee's list included 18 Japanese cities. At the top of the list were

Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the c ...

,

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

,

Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

,

Kokura, and

Niigata. Ultimately, Kyoto was removed from the list at the insistence of

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, who had visited the city on his honeymoon and knew of its cultural and historical significance.

Although the previous

Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

,

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

, had been involved in the Manhattan Project since the beginning, his successor,

Harry S. Truman, was not briefed on the project by Stimson until 23 April 1945, eleven days after he became president on Roosevelt's death on 12 April 1945. On 2 May 1945, Truman approved the formation of the

Interim Committee

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on m ...

, an advisory group that would report on the atomic bomb. It consisted of Stimson,

James F. Byrnes,

George L. Harrison

George Leslie Harrison (January 26, 1887 – March 5, 1958) was an American banker, insurance executive and advisor to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson during World War II.

Early life and education

Harrison was born in San Francisco, California ...

,

Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

,

James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916 ...

,

Karl Taylor Compton

Karl Taylor Compton (September 14, 1887 – June 22, 1954) was a prominent American physicist and president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from 1930 to 1948.

The early years (1887–1912)

Karl Taylor Compton was born in ...

,

William L. Clayton, and

Ralph Austin Bard, advised by a Scientific Panel composed of

Robert Oppenheimer,

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

,

Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

, and

Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

. In a 1 June report, the Committee concluded that the bomb should be used as soon as possible against a war plant surrounded by workers' homes and that no warning or demonstration should be given.

The committee's mandate did not include the use of the bomb—its use upon completion was presumed. Following a protest by scientists involved in the project, in the form of the

Franck Report

The Franck Report of June 1945 was a document signed by several prominent nuclear physicists recommending that the United States not use the atomic bomb as a weapon to prompt the surrender of Japan in World War II.

The report was named for James ...

, the Committee re-examined the use of the bomb, posing the question to the Scientific Panel of whether a "demonstration" of the bomb should be used before actual battlefield deployment. In a 21 June meeting, the Scientific Panel affirmed that there was no alternative.

Truman played very little role in these discussions. At Potsdam, he was enthralled by the successful report of the Trinity test, and those around him noticed a positive change in his attitude, believing the bomb gave him leverage with both Japan and the Soviet Union. Other than backing Stimson's play to remove Kyoto from the target list (as the military continued to push for it as a target), he was otherwise not involved in any decision-making regarding the bomb, contrary to later retellings of the story (including Truman's own embellishments).

Proposed invasion

On 18 June 1945, Truman met with the Chief of Army Staff General

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

, Air Force General

Henry Arnold, Chief of Staff Admiral

William Leahy and Admiral

Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the U ...

, Navy Secretary

James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-class Irish Catholic fami ...

, Secretary for War Henry Stimson and Assistant Secretary for War

John McCloy to discuss

Operation Olympic

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

, part of a plan to invade the Japanese home islands. General Marshall supported the entry of the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, believing that doing so would cause Japan to capitulate. McCloy had told Stimson that there were no more Japanese cities to be bombed and wanted to explore other options of bringing about a surrender. He suggested a political solution and asked about warning the Japanese of the atomic bomb. James Byrnes, who would become the new Secretary of State on 3 July, wanted to use it as quickly as possible without warning and without letting the Soviets know beforehand.

Soviet Union negotiation attempts

On 30 June, Tōgō told

Naotake Satō

was a Japanese diplomat and politician. He was born in Osaka, graduated from the Tokyo Higher Commercial School (東京高等商業学校, ''Tōkyō Kōtō Shōgyō Gakkō'', now Hitotsubashi University) in 1904, attended the consul course of ...

, Japan's ambassador in Moscow, to try to establish "firm and lasting relations of friendship." Satō was to discuss the status of Manchuria and "any matter the Russians would like to bring up." Well aware of the overall situation and cognizant of their promises to the Allies, the Soviets responded with delaying tactics to encourage the Japanese without promising anything. Satō finally met with Soviet Foreign Minister

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

on 11 July, but without result. On 12 July, Tōgō directed Satō to tell the Soviets that:

The Emperor proposed sending Prince Konoe as a special envoy, although he would be unable to reach Moscow before the

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

.

Satō advised Tōgō that in reality, "unconditional surrender or terms closely equivalent thereto" was all that Japan could expect. Moreover, in response to Molotov's requests for specific proposals, Satō suggested that Tōgō's messages were not "clear about the views of the Government and the Military with regard to the termination of the war," thus questioning whether Tōgō's initiative was supported by the key elements of Japan's power structure.

On 17 July, Tōgō responded:

In reply, Satō clarified:

On 21 July, speaking in the name of the cabinet, Tōgō repeated:

American cryptographers

had broken most of Japan's codes, including the

Purple code used by the Japanese Foreign Office to encode high-level diplomatic correspondence. As a result, messages between

Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

and Japan's embassies were provided to Allied policy-makers nearly as quickly as to the intended recipients. Fearing heavy casualties, the Allies wished for Soviet entry in the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

at the earliest possible date. Roosevelt had secured Stalin's promise at

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, which was re-affirmed at

Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

. That outcome was greatly feared in Japan.

Soviet intentions

Security concerns dominated Soviet decisions concerning the Far East. Chief among these was gaining unrestricted access to the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

. The year-round ice-free areas of the Soviet Pacific coastline—

Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, ...

in particular—could be blockaded by air and sea from

Sakhalin island

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh ...

and the

Kurile Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

. Acquiring these territories, thus guaranteeing free access to the

Soya Strait

Soya may refer to:

Food

* Soya bean, or soybean, a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean

* Soya sauce, see soy sauce, a fermented sauce made from soybeans, roasted grain, water and salt

Places

* Sōya District, ...

, was their primary objective. Secondary objectives were leases for the

Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

,

Southern Manchuria Railway

The South Manchuria Railway ( ja, 南満州鉄道, translit=Minamimanshū Tetsudō; ), officially , Mantetsu ( ja, 満鉄, translit=Mantetsu) or Mantie () for short, was a large of the Empire of Japan whose primary function was the operatio ...

,

Dairen

Dalian () is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China. Located on the ...

, and

Port Arthur.

To this end, Stalin and Molotov strung out the negotiations with the Japanese, giving them false hope of a Soviet-mediated peace. At the same time, in their dealings with the United States and Britain, the Soviets insisted on strict adherence to the Cairo Declaration, re-affirmed at the Yalta Conference, that the Allies would not accept separate or conditional peace with Japan. The Japanese would have to surrender unconditionally to all the Allies. To prolong the war, the Soviets opposed any attempt to weaken this requirement. This would give the Soviets time to complete the transfer of their troops from the Western Front to the Far East, and conquer

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

,

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, northern

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

,

South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

, the

Kuriles

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in th ...

, and possibly

Hokkaidō

is Japan, Japan's Japanese archipelago, second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost Prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own List of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; th ...

(starting with a landing at

Rumoi

is a city located in Rumoi Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is the capital of Rumoi Subprefecture.

As of September 2016, the city has an estimated population of 22,242 and the density of 75 persons per km2. The total area is 297.44 ...

).

Events at Potsdam

The leaders of the major Allied powers met at the

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

from 16 July to 2 August 1945. The participants were the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, represented by Stalin,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

(later

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

), and Truman respectively.

Negotiations

Although the Potsdam Conference was mainly concerned with European affairs, the war against Japan was also discussed in detail. Truman learned of the successful Trinity test early in the conference and shared this information with the British delegation. The successful test caused the American delegation to reconsider the necessity and wisdom of Soviet participation, for which the U.S. had lobbied hard at the

Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

and

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

s. High on the United States' list of priorities was shortening the war and reducing American casualties—Soviet intervention seemed likely to do both, but at the cost of possibly allowing the Soviets to capture territory beyond that which had been promised to them at Tehran and Yalta, and causing a postwar division of Japan similar to that which had

occurred in Germany.

In dealing with Stalin, Truman decided to give the Soviet leader vague hints about the existence of a powerful new weapon without going into details. However, the other Allies were unaware that Soviet intelligence had penetrated the Manhattan Project in its early stages, so Stalin already knew of the existence of the atomic bomb but did not appear impressed by its potential.

The Potsdam Declaration

It was decided to issue a statement, the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

, defining "Unconditional Surrender" and clarifying what it meant for the position of the emperor and for Hirohito personally. The American and British governments strongly disagreed on this point—the United States wanted to abolish the position and possibly try him as a war criminal, while the British wanted to retain the position, perhaps with Hirohito still reigning. Furthermore, although it would not initially be a party to the declaration, the Soviet government also had to be consulted since it would be expected to endorse it upon entering the war. Assuring the retention of the emperor would change the Allied policy of unconditional surrender and necessitated consent from Stalin. The American Secretary of State James Byrnes, however, wanted to keep the Soviets out of the Pacific war as much as possible and persuaded Truman to delete any such assurances. The Potsdam Declaration went through many drafts until a version acceptable to all was found.

On 26 July, the United States, Britain and China released the Potsdam Declaration announcing the terms for Japan's surrender, with the warning, "We will not deviate from them. There are no alternatives. We shall brook no delay." For Japan, the terms of the declaration specified:

* the elimination "for all time

fthe authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest"

* the occupation of "points in Japanese territory to be designated by the Allies"

* that the "Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of

Honshū

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island sepa ...

,

Hokkaidō

is Japan, Japan's Japanese archipelago, second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost Prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own List of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; th ...

,

Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

,

Shikoku

is the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. It is long and between wide. It has a population of 3.8 million (, 3.1%). It is south of Honshu and northeast of Kyushu. Shikoku's ancient names include ''Iyo-no-futana-shima'' (), '' ...

and such minor islands as we determine." As had been announced in the

Cairo Declaration in 1943, Japan was to be reduced to her pre-1894 territory and stripped of her pre-war empire including

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

and

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

, as well as all her recent conquests.

* that "

e Japanese

military forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinc ...

, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted to return to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives."

* that "

do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation, but stern justice shall be meted out to all

war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners."

On the other hand, the declaration stated that:

* "The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people.

Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

,

of religion, and

of thought, as well as respect for the

fundamental human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

shall be established."

* "Japan shall be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind, but not those which would enable her to rearm for war. To this end, access to, as distinguished from control of, raw materials shall be permitted. Eventual Japanese participation in world trade relations shall be permitted."

* "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established, in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people, a peacefully inclined and responsible government."

The only use of the term "

unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

" came at the end of the declaration:

* "We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction."

Contrary to what had been intended at its conception, the Declaration made no mention of the Emperor at all. Secretary of State

Joseph Grew

Joseph Clark Grew (May 27, 1880 – May 25, 1965) was an American career diplomat and Foreign Service officer. He is best known as the ambassador to Japan from 1932 to 1941 and as a high official in the State Department in Washington from 1944 to ...

had advocated for retaining the emperor as a constitutional monarch. He hoped that preserving Hirohito's central role could facilitate an orderly capitulation of all Japanese troops in the Pacific theatre. Without it, securing a surrender could be difficult. Navy Secretary

James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-class Irish Catholic fami ...

and other officials shared the view. Allied intentions on issues of utmost importance to the Japanese, including whether Hirohito was to be regarded as one of those who had "misled the people of Japan" or even a war criminal, or alternatively, whether the Emperor might become part of a "peacefully inclined and responsible government" were thus left unstated.

The "prompt and utter destruction" clause has been interpreted as a veiled warning about American possession of the atomic bomb (which had been tested successfully on the first day of the conference). On the other hand, the declaration also made specific references to the devastation that had been wrought upon Germany in the closing stages of the European war. To contemporary readers on both sides who were not yet aware of the atomic bomb's existence, it was easy to interpret the conclusion of the declaration simply as a threat to bring similar destruction upon Japan using conventional weapons.

Japanese reaction

On 27 July, the Japanese government considered how to respond to the Declaration. The four military members of the Big Six wanted to reject it, but Tōgō, acting under the mistaken impression that the Soviet government had no prior knowledge of its contents, persuaded the cabinet not to do so until he could get a reaction from Moscow. The cabinet decided to publish the declaration without comment for the time being. In a telegram,

Shun'ichi Kase

was a Japanese diplomat both during and after World War II.

Shun'ichi Kase was a secretary to Japanese Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka in 1941. Then he was chargé d’affaires in Italy, as of 1943. Subsequently, he served as Japanese Amba ...

, Japan's ambassador to Switzerland, observed that "unconditional surrender" applied only to the military and not to the government or the people, and he pleaded that it should be understood that the careful language of Potsdam appeared "to have occasioned a great deal of thought" on the part of the signatory governments—"they seem to have taken pains to

save face for us on various points." The next day, Japanese newspapers reported that the Declaration, the text of which had been broadcast and dropped by

leaflet into Japan, had been rejected. In an attempt to manage public perception, Prime Minister Suzuki met with the press, and stated:

Chief Cabinet Secretary

Hisatsune Sakomizu

was a Japanese government official and politician before, during and after World War II. He is well known for serving as the chief secretary to Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki's Cabinet (April–August 1945).

He was ordered by Suzuki to inves ...

had advised Suzuki to use the expression . Its meaning is ambiguous and can range from "refusing to comment on" to "ignoring (by keeping silence)".

[Kenkyusha. 2004. ]Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary

First published in 1918, has long been the largest and most authoritative Japanese-English dictionary. Translators, scholars, and specialists who use the Japanese language affectionately refer to this dictionary as the ''Green Goddess'' or ('' ...

5th ed. What was intended by Suzuki has been the subject of debate.

Tōgō later said that the making of such a statement violated the cabinet's decision to withhold comment.

On 30 July, Ambassador Satō wrote that Stalin was probably talking to Roosevelt and Churchill about his dealings with Japan, and he wrote: "There is no alternative but immediate unconditional surrender if we are to prevent Russia's participation in the war." On 2 August, Tōgō wrote to Satō: "it should not be difficult for you to realize that ... our time to proceed with arrangements of ending the war before the enemy lands on the Japanese mainland is limited, on the other hand it is difficult to decide on concrete peace conditions here at home all at once."

Hiroshima, Manchuria, and Nagasaki

6 August: Hiroshima

On 6 August at 8:15 AM local time, the ''

Enola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, piloted by Tibbets and Robert A. Lewis during the final stages of World War II, it ...

'', a

Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

piloted by Colonel

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the ''Enola Gay'' (named after his moth ...

,

dropped an atomic bomb (code-named

Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

by the U.S.) on the city of

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

in southwest Honshū. Throughout the day, confused reports reached Tokyo that Hiroshima had been the target of an air raid, which had leveled the city with a "blinding flash and violent blast". Later that day, they received U.S. President

Truman's broadcast announcing the first use of an

atomic bomb