James Tod on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod (20 March 1782 – 18 November 1835) was an officer of the

Rather than being situated permanently in one place, the royal court was moved around the kingdom. Tod undertook various topographical and geological studies as it travelled from one area to another, using his training as an engineer and employing other people to do much of the field work. These studies culminated in 1815 with the production of a map which he presented to the

Rather than being situated permanently in one place, the royal court was moved around the kingdom. Tod undertook various topographical and geological studies as it travelled from one area to another, using his training as an engineer and employing other people to do much of the field work. These studies culminated in 1815 with the production of a map which he presented to the

Koditschek says that Tod "developed an interest in triangulating local culture, politics and history alongside his maps", and Metcalf believes that Tod "ordered

Koditschek says that Tod "developed an interest in triangulating local culture, politics and history alongside his maps", and Metcalf believes that Tod "ordered

Criticism of the ''Annals'' came soon after publication. The anonymous author of the introduction to his posthumously published ''Travels'' states that

Further criticism followed. Tod was an officer of the British imperial system, at that time the world's dominant power. Working in India, he attracted the attention of local rulers who were keen to tell their own tales of defiance against the Mughal empire. He heard what they told him but knew little of what they omitted. He was a soldier writing about a caste renowned for its martial abilities, and he was aided in his writings by the very people whom he was documenting. He had been interested in Rajput history prior to coming into contact with them in an official capacity, as administrator of the region in which they lived. These factors, says Freitag, contribute to why the ''Annals'' were "manifestly biased".Freitag (2009), pp. 3–5. Freitag argues that critics of Tod's literary output can be split into two groups: those who concentrate on his errors of fact and those who concentrate on his failures of interpretation.

Tod relied heavily on existing Indian texts for his historical information and most of these are today considered unreliable. Crooke's introduction to Tod's 1920 edition of the ''Annals'' recorded that the old Indian texts recorded "the facts, not as they really occurred, but as the writer and his contemporaries supposed that they occurred." Crooke also says that Tod's "knowledge of ethnology was imperfect, and he was unable to reject the local chronicles of the Rajputs." More recently, Robin Donkin, a historian and geographer, has argued that, with one exception, "there are no native literary works with a developed sense of chronology, or indeed much sense of place, before the thirteenth century", and that researchers must rely on the accounts of travellers from outside the country.

Tod's work relating to the genealogy of the ''Chathis Rajkula'' was criticised as early as 1872, when an anonymous reviewer in the '' Calcutta Review'' said that Other examples of dubious interpretations made by Tod include his assertions regarding the ancestry of the Mohil Rajput clan when, even today, there is insufficient evidence to prove his point. He also mistook

Criticism of the ''Annals'' came soon after publication. The anonymous author of the introduction to his posthumously published ''Travels'' states that

Further criticism followed. Tod was an officer of the British imperial system, at that time the world's dominant power. Working in India, he attracted the attention of local rulers who were keen to tell their own tales of defiance against the Mughal empire. He heard what they told him but knew little of what they omitted. He was a soldier writing about a caste renowned for its martial abilities, and he was aided in his writings by the very people whom he was documenting. He had been interested in Rajput history prior to coming into contact with them in an official capacity, as administrator of the region in which they lived. These factors, says Freitag, contribute to why the ''Annals'' were "manifestly biased".Freitag (2009), pp. 3–5. Freitag argues that critics of Tod's literary output can be split into two groups: those who concentrate on his errors of fact and those who concentrate on his failures of interpretation.

Tod relied heavily on existing Indian texts for his historical information and most of these are today considered unreliable. Crooke's introduction to Tod's 1920 edition of the ''Annals'' recorded that the old Indian texts recorded "the facts, not as they really occurred, but as the writer and his contemporaries supposed that they occurred." Crooke also says that Tod's "knowledge of ethnology was imperfect, and he was unable to reject the local chronicles of the Rajputs." More recently, Robin Donkin, a historian and geographer, has argued that, with one exception, "there are no native literary works with a developed sense of chronology, or indeed much sense of place, before the thirteenth century", and that researchers must rely on the accounts of travellers from outside the country.

Tod's work relating to the genealogy of the ''Chathis Rajkula'' was criticised as early as 1872, when an anonymous reviewer in the '' Calcutta Review'' said that Other examples of dubious interpretations made by Tod include his assertions regarding the ancestry of the Mohil Rajput clan when, even today, there is insufficient evidence to prove his point. He also mistook

UK public library membership

required). * * (Subscription required).

British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

and an Oriental scholar

Oriental studies is the academic field that studies Near Eastern and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and archaeology. In recent years, the subject has often been turned into the newer terms of Middle Eastern studie ...

. He combined his official role and his amateur interests to create a series of works about the history and geography of India, and in particular the area then known as Rajputana

Rājputana, meaning "Land of the Rajputs", was a region in the Indian subcontinent that included mainly the present-day Indian state of Rajasthan, as well as parts of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, and some adjoining areas of Sindh in modern-day ...

that corresponds to the present day state of Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern ...

, and which Tod referred to as ''Rajast'han''.

Tod was born in London and educated in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. He joined the East India Company as a military officer and travelled to India in 1799 as a cadet

A cadet is an officer trainee or candidate. The term is frequently used to refer to those training to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. Its meaning may vary between countries which can include youths in ...

in the Bengal Army

The Bengal Army was the army of the Bengal Presidency, one of the three presidencies of British India within the British Empire.

The presidency armies, like the presidencies themselves, belonged to the East India Company (EIC) until the Gover ...

. He rose quickly in rank, eventually becoming captain of an escort for an envoy

Envoy or Envoys may refer to:

Diplomacy

* Diplomacy, in general

* Envoy (title)

* Special envoy, a type of diplomatic rank

Brands

*Airspeed Envoy, a 1930s British light transport aircraft

*Envoy (automobile), an automobile brand used to sell Br ...

in a Sindian royal court. After the Third Anglo-Maratha War

The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1819) was the final and decisive conflict between the English East India Company and the Maratha Empire in India. The war left the Company in control of most of India. It began with an invasion of Maratha ter ...

, during which Tod was involved in the intelligence department, he was appointed Political Agent for some areas of Rajputana. His task was to help unify the region under the control of the East India Company. During this period Tod conducted most of the research that he would later publish. Tod was initially successful in his official role, but his methods were questioned by other members of the East India Company. Over time, his work was restricted and his areas of oversight were significantly curtailed. In 1823, owing to declining health and reputation, Tod resigned his post as Political Agent and returned to England.

Back home in England, Tod published a number of academic works about Indian history and geography, most notably ''Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han'', based on materials collected during his travels. He retired from the military in 1826, and married Julia Clutterbuck that same year. He died in 1835, aged 53.

Life and career

Tod was born inIslington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

, London, on 20 March 1782.Freitag (2009), p. 33. He was the second son for his parents, James and Mary (née Heatly), both of whom came from families of "high standing", according to his major biographer, the historian Jason Freitag. He was educated in Scotland, whence his ancestors came, although precisely where he was schooled is unknown. Those ancestors included people who had fought with the King of Scots

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have gro ...

, Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

; he took pride in this fact and had an acute sense of what he perceived to be the chivalric values of those times.Freitag (2007), p. 49.

As with many people of Scots descent who sought adventure and success at that time, Tod joined the British East India Company and initially spent some time studying at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich

The Royal Military Academy (RMA) at Woolwich, in south-east London, was a British Army military academy for the training of commissioned officers of the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers. It later also trained officers of the Royal Corps of S ...

. He left England for India in 1799 and in doing so followed in the footsteps of various other members of his family, including his father, although Tod senior had not been in the company but had instead owned an indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', ...

plantation at Mirzapur

Mirzapur () is a city in Uttar Pradesh, India, 827 km from Delhi and 733 km from Kolkata, almost 91 km from Prayagraj (formally known as Allahabad) and 61 km from Varanasi. It is known for its carpets and brassware industries, and the folk ...

. The young Tod journeyed as a cadet in the Bengal Army, appointment to which position was at the time reliant upon patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

. He was appointed lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in May 1800 and in 1805 was able to arrange his posting as a member of the escort to a family friend who had been appointed as Envoy and Resident to a Sindian royal court. By 1813 he had achieved promotion to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

and was commanding the escort.Freitag (2009), pp. 34–36.

Rather than being situated permanently in one place, the royal court was moved around the kingdom. Tod undertook various topographical and geological studies as it travelled from one area to another, using his training as an engineer and employing other people to do much of the field work. These studies culminated in 1815 with the production of a map which he presented to the

Rather than being situated permanently in one place, the royal court was moved around the kingdom. Tod undertook various topographical and geological studies as it travelled from one area to another, using his training as an engineer and employing other people to do much of the field work. These studies culminated in 1815 with the production of a map which he presented to the Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, the Marquis of Hastings

Marquess of Hastings was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 6 December 1816 for Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 2nd Earl of Moira.

History

The Rawdon family descended from Francis Rawdon (d. 1668), of Rawdon, Yorkshire. ...

. This map of "Central India" (his phrase) became of strategic importance to the British as they were soon to fight the Third Anglo-Maratha War. During that war, which ran from 1817 to 1818, Tod acted as a superintendent of the intelligence department and was able to draw on other aspects of regional knowledge which he had acquired while moving around with the court. He also drew up various strategies for the military campaign.

In 1818 he was appointed Political Agent for various states of western Rajputana, in the northwest of India, where the British East India Company had come to amicable arrangements with the Rajput

Rajput (from Sanskrit ''raja-putra'' 'son of a king') is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating from the Indian subcontinent. The term Ra ...

rulers in order to exert indirect control over the area. The anonymous author of the introduction to Tod's posthumously published book, ''Travels in Western India'', says that

Tod continued his surveying work in this physically challenging, arid and mountainous area. His responsibilities were extended quickly: initially involving himself with the regions of Mewar

Mewar or Mewad is a region in the south-central part of Rajasthan state of India. It includes the present-day districts of Bhilwara, Chittorgarh, Pratapgarh, Rajsamand, Udaipur, Pirawa Tehsil of Jhalawar District of Rajasthan, Neemuch and ...

, Kota, Sirohi

Sirohi is a city, located in Sirohi district in southern Rajasthan state in western India. It is the administrative headquarters of Sirohi District and was formerly the capital of the princely state of Sirohi ruled by Deora Chauhan Rajput rul ...

and Bundi

Bundi is a city in the Hadoti region of Rajasthan state in northwest India and capital of the former princely state of Rajputana agency. District of Bundi is named after the former princely state.

Demographics

According to the 2011 Indian cens ...

, he soon added Marwar

Marwar (also called Jodhpur region) is a region of western Rajasthan state in North Western India. It lies partly in the Thar Desert. The word 'maru' is Sanskrit for desert. In Rajasthani languages, "wad" means a particular area. English tra ...

to his portfolio and in 1821 was also given responsibility for Jaisalmer

Jaisalmer , nicknamed "The Golden city", is a city in the Indian state of Rajasthan, located west of the state capital Jaipur. The town stands on a ridge of yellowish sandstone and is crowned by the ancient Jaisalmer Fort. This fort contains a ...

.Freitag (2009), pp. 37–40. These areas were considered a strategic buffer zone against Russian advances from the north which, it was feared, might result in a move into India via the Khyber Pass

The Khyber Pass (خیبر درہ) is a mountain pass in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, on the border with the Nangarhar Province of Afghanistan. It connects the town of Landi Kotal to the Valley of Peshawar at Jamrud by traversing p ...

. Tod believed that to achieve cohesion it was necessary that the Rajput states should contain only Rajput people, with all others being expelled. This would assist in achieving stability in the areas, thus limiting the likelihood of the inhabitants being influenced by outside forces. Charanas were called upon to create a master list of the 'Thirty Six Royal Races of Rajasthan' with Tod's guru Yati Gyanchandra presiding the panel. According to Ramya Sreenivasan, a researcher of religion and caste in early modern Rajasthan and of colonialism, Tod's "transfers of territory between various chiefs and princes helped to create territorially consolidated states and 'routinised' political hierarchies." His successes were plentiful and the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' notes that Tod was

Tod was not, however, universally respected in the East India Company. His immediate superior, David Ochterlony, was unsettled by Tod's rapid rise and frequent failure to consult with him. One Rajput prince objected to Tod's close involvement in the affairs of his state and succeeded in persuading the authorities to remove Marwar from Tod's area of influence. In 1821 his favouritism towards one party in a princely dispute, contrary to the orders given to him, gave rise to a severe reprimand and a formal restriction of his ability to operate without consulting Ochterlony, as well as the removal of Kota from his charge. Jaisalmer was then taken out of his sphere of influence in 1822, as official concerns grew regarding his sympathy for the Rajput princes. This and other losses of status, such as the reduction in the size of his escort, caused him to believe that his personal reputation and ability to work successfully in Mewar, by now the one area still left to him, was too diminished to be acceptable. He resigned his role as Political Agent in Mewar later that year, citing ill health. Reginald Heber

Reginald Heber (21 April 1783 – 3 April 1826) was an English Anglican bishop, man of letters and hymn-writer. After 16 years as a country parson, he served as Bishop of Calcutta until his death at the age of 42. The son of a rich lando ...

, the Bishop of Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

, commented that

In February 1823, Tod left India for England, having first travelled to Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

by a circuitous route for his own pleasure.Freitag (2009), p. 40.

During the last years of his life Tod talked about India at functions in Paris and elsewhere across Europe. He also became a member of the newly established Royal Asiatic Society

The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, commonly known as the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS), was established, according to its royal charter of 11 August 1824, to further "the investigation of subjects connected with and for the en ...

in London, for whom he acted for some time as librarian. He suffered an apoplectic fit

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

in 1825 as a consequence of overwork, and retired from his military career in the following year, soon after he had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colo ...

. His marriage to Julia Clutterbuck (daughter of Henry Clutterbuck

Henry Clutterbuck M.D. (1767–1856) was an English medical writer.

Life

Clutterbuck was the fifth child of Thomas Clutterbuck, attorney, who died at Marazion in Cornwall 6 November 1781, by his wife, Mary, a daughter of Christopher Masterman ...

) in 1826 produced three children – Grant Heatly Tod-Heatly, Edward H. M. Tod and Mary Augusta Tod – but his health, which had been poor for much of his life, was declining. Having lived at Birdhurst, Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an exten ...

, from October 1828, Tod and his family moved to London three years later. He spent much of the last year of his life abroad in an attempt to cure a chest complaint and died on 18 November 1835 soon after his return to England from Italy. The cause of death was an apoplectic fit sustained on the day of his wedding anniversary, although he survived for a further 27 hours. He had moved into a house in Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies of high ground in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the Borough of Camden (and historically betwee ...

earlier in that year.

Worldview

Historian Lynn Zastoupil has noted that Tod's personal papers have never been found and "his voluminous publications and official writings contain only scattered clues regarding the nature of his personal relationships with Rajputs". This has not discouraged assessments being made of both him and his worldview. According to Theodore Koditschek, whose fields of study includehistoriography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians h ...

and British imperial history, Tod saw the Rajputs as "natural allies of the British in their struggles against the Mughal and Maratha

The Marathi people ( Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed a ...

states".Koditschek (2011), p. 68. Norbert Peabody, an anthropologist and historian, has gone further, arguing that "maintaining the active support of groups, like the Rajputs for example, was not only important in meeting the threat of indigenous rivals but also in countering the imperial aspirations of other European powers." He stated that some of Tod's thoughts were "implicated in ritishcolonial policy toward western India for over a century."

Tod favoured the then-fashionable concept of Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

. Influenced by this, he thought that each princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

should be inhabited by only one community and his policies were designed to expel Marathas, Pindaris and other groups from Rajput territories. It also influenced his instigation of treaties that were intended to redraw the territorial boundaries of the various states. The geographical and political boundaries before his time had in some cases been blurred, primarily due to local arrangements based on common kinship, and he wanted a more evident delineation of the entities, He was successful in both of these endeavours.

Tod was unsuccessful in implementing another of his ideas, which was also based on the ideology of Romantic nationalism. He believed that the replacement of Maratha rule with that of the British had resulted in the Rajputs merely swapping the onerous overlordship of one government for that of another. Although he was one of the architects of indirect rule, in which the princes looked after domestic affairs but paid tribute to the British for protection in foreign affairs, he was also a critic of it. He saw the system as one that prevented achievement of true nationhood, and therefore, as Peabody describes, "utterly subversive to the stated goal of preserving them as viable entities."Peabody (1996), pp. 206–207. Tod wrote in 1829 that the system of indirect rule had a tendency to "national degradation" of the Rajput territories and that this undermined them because

There was a political aspect to his views: if the British recast themselves as overseers seeking to re-establish lost Rajput nations, then this would at once smooth the relationship between those two parties and distinguish the threatening, denationalising Marathas from the paternal, nation-creating British. It was an argument that had been deployed by others in the European arena, including in relation to the way in which Britain portrayed the imperialism of Napoleonic France as denationalising those countries which it conquered, whereas (it was claimed) British imperialism freed people; William Bentinck, a soldier and statesmen who later in life served as Governor-General of India, noted in 1811 that "Bonaparte made kings; England makes nations". However, his arguments in favour of granting sovereignty to the Rajputs failed to achieve that end, although the frontispiece to volume one of his ''Annals'' did contain a plea to the then English King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

to reinstate the "former independence" of the Rajputs.Peabody (1996), p. 217.

While he viewed the Muslim Mughals as despotic and the Marathas as predatory, Tod saw the Rajput social systems as being similar to the feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

of medieval Europe, and their traditions of recounting history through the generations as similar to the clan poets of the Scottish Highlanders

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sc ...

. There was, he felt, a system of checks and balances between the ruling princes and their vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

lords, a tendency for feuds and other rivalries, and often a serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

-like peasantry.Metcalf (1997), pp. 73–74. The Rajputs were, in his opinion, on the same developmental trajectory that nations such as Britain had followed. His ingenious use of these viewpoints later enabled him to promote in his books the notion that there was a shared experience between the people of Britain and this community in a distant, relatively unexplored area of the empire. He speculated that there was a common ancestor shared by the Rajputs and Europeans somewhere deep in prehistory and that this might be proven by comparison of the commonality in their history of ideas, such as myth and legend. In this he shared a contemporary aspiration to prove that all communities across the world had a common origin.Sreenivasan (2007), pp. 130–132. There was another appeal inherent in a feudal system, and it was not unique to Tod: the historian Thomas R. Metcalf has said that Above all, the chivalric ideal viewed character as more worthy of admiration than wealth or intellect, and this appealed to the old landed classes at home as well as to many who worked for the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million p ...

.

In the 1880s, Alfred Comyn Lyall

Sir Alfred Comyn Lyall (4 January 1835 – 10 April 1911) was a British civil servant, literary historian and poet.

Early life

He was born at Coulsdon in Surrey, the second son of Alfred Lyall and Mary Drummond Broadwood, daughter of James S ...

, an administrator of the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

who also studied history, revisited Tod's classification and asserted that the Rajput society was in fact tribal, based on kinship rather than feudal vassalage. He had previously generally agreed with Tod, who acknowledged claims that blood-ties played some sort of role in the relationship between princes and vassals in many states. In shifting the emphasis from a feudal to a tribal basis, Lyall was able to deny the possibility that the Rajput kingdoms might gain sovereignty. If Rajput society was not feudal, then it was not on the same trajectory that European nations had followed, thereby forestalling any need to consider that they might evolve into sovereign states. There was thus no need for Britain to consider itself to be illegitimately governing them.

Tod's enthusiasm for bardic poetry reflected the works of Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

on Scottish subjects, which had a considerable influence both on British literary society and, bearing in mind Tod's Scottish ancestry, on Tod himself. Tod reconstructed Rajput history on the basis of the ancient texts and folklore of the Rajputs, although not everyone – for example, the polymath James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of Briti ...

– accepted the historical validity of the native works. Tod also used philological techniques to reconstruct areas of Rajput history that were not even known to the Rajputs themselves, by drawing on works such as the religious texts known as ''Purana

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

s''.

Publications

Koditschek says that Tod "developed an interest in triangulating local culture, politics and history alongside his maps", and Metcalf believes that Tod "ordered

Koditschek says that Tod "developed an interest in triangulating local culture, politics and history alongside his maps", and Metcalf believes that Tod "ordered he Rajputs'

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

past as well as their present" while working in India.Metcalf (1997), p. 73. During his time in Rajputana, Tod was able to collect materials for his ''Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han'', which detailed the contemporary geography and history of Rajputana and Central India along with the history of the Rajput clans who ruled most of the area at that time. Described by historian Crispin Bates as "a romantic historical and anecdotal account" and by David Arnold, another historian, as a "travel narrative" by "one of India's most influential Romantic writers", the work was published in two volumes, in 1829 and 1832, and included illustrations and engravings by notable artists such as the Storers, Louis Haghe

Louis Haghe (17 March 1806 – 9 March 1885) was a Belgian lithographer and watercolourist.

His father and grandfather had practised as architects. Training in his teens in watercolour painting, he found work in the relatively new art of lithog ...

and either Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

or William Finden

William Finden (178720 September 1852) was an English engraver.

Life

He served his apprenticeship to James Mitan, but appears to have owed far more to the influence of James Heath, whose works he privately and earnestly studied. His first empl ...

. He had to finance publication himself: sales of works on history had been moribund for some time and his name was not particularly familiar either at home or abroad. Original copies are now scarce, but they have been reprinted in many editions. The version published in 1920, which was edited by the orientalist and folklorist

Folklore studies, less often known as folkloristics, and occasionally tradition studies or folk life studies in the United Kingdom, is the branch of anthropology devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currenc ...

William Crooke, is significantly editorialised.

Freitag has argued that the ''Annals'' "is first and foremost a story of the heroes of Rajasthan ... plotted in a certain way – there are villains, glorious acts of bravery, and a chivalric code to uphold". So dominant did Tod's work become in the popular and academic mind that they largely replaced the older accounts like '' Nainsi ri Khyat'' and even '' Prithvirãj Rãso.'' Tod had even used the ''Raso'' for his content. Kumar Singh, of the Anthropological Survey of India, has explained that the ''Annals'' were primarily based on "bardic accounts and personal encounters" and that they "glorified and romanticised the Rajput rulers and their country" but ignored other communities.

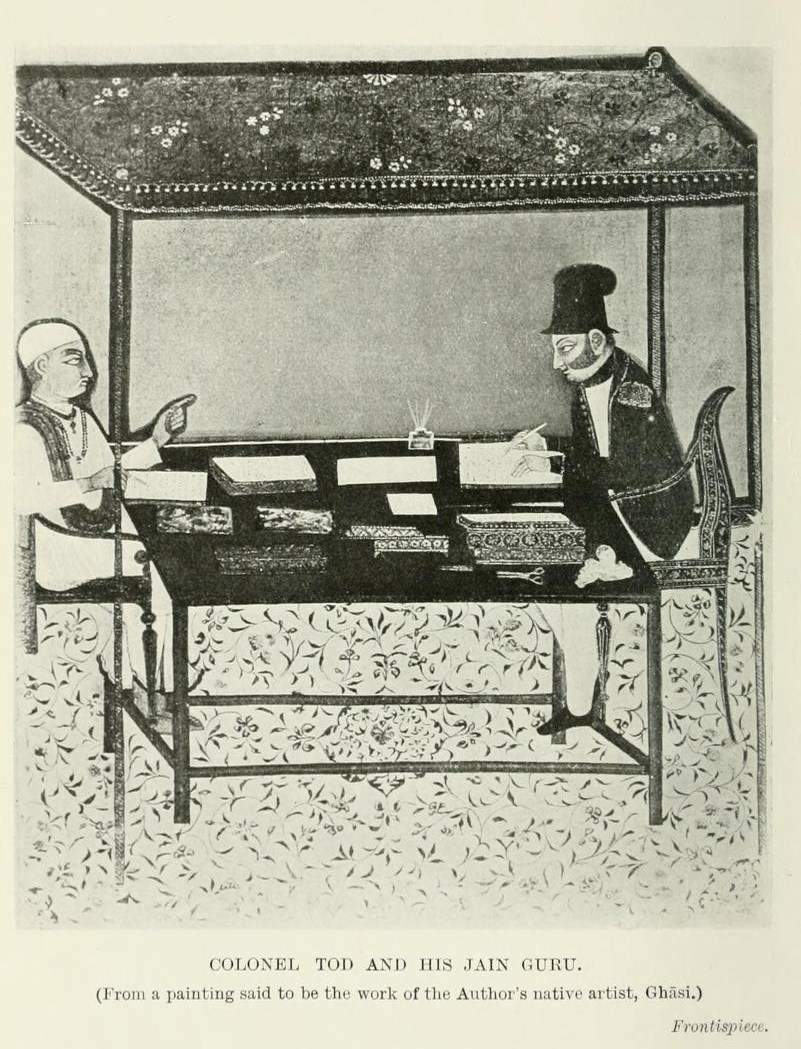

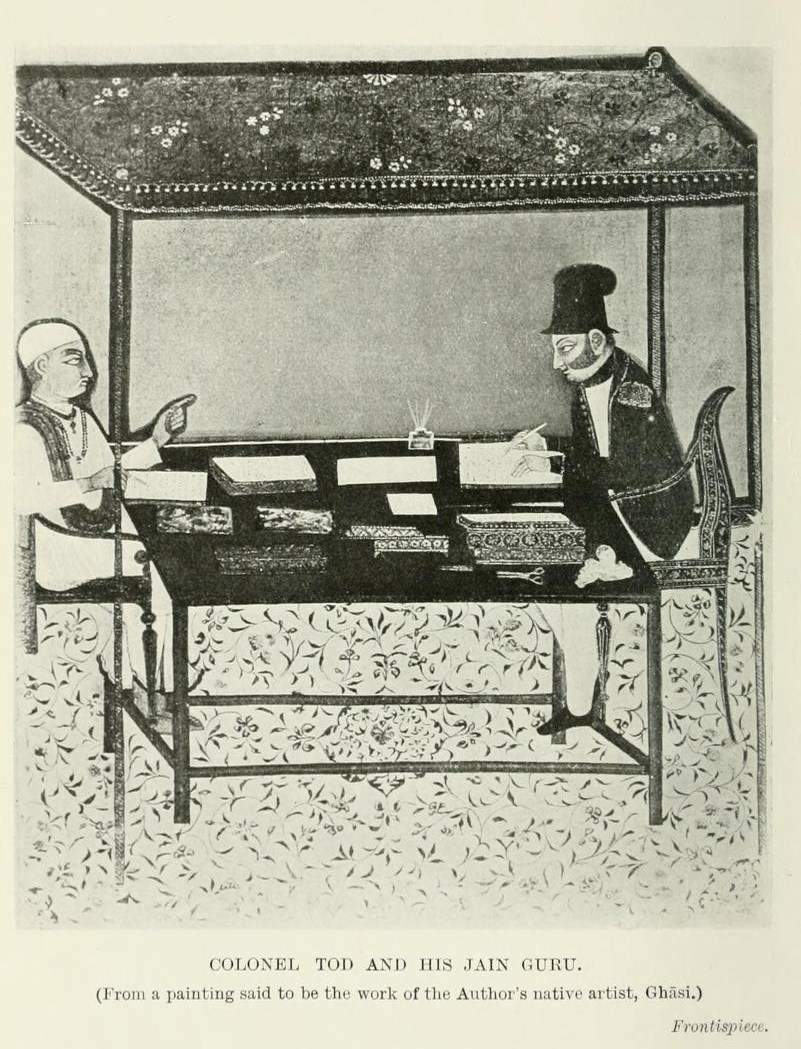

One aspect of history that Tod studied in his ''Annals'' was the genealogy of the ''Chathis Rajkula'' ( 36 royal races), for the purpose of which he took advice on linguistic issues from a panel of ''pandit

A Pandit ( sa, पण्डित, paṇḍit; hi, पंडित; also spelled Pundit, pronounced ; abbreviated Pt.) is a man with specialised knowledge or a teacher of any field of knowledge whether it is shashtra (Holy Books) or shastra (Wea ...

s'', including a Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

guru called Yati

Yati, historically was the general term for a monk or pontiff in Hinduism and Jainism.

Jainism

In the late medieval period, yati came to represent a stationary monk, who lived in one place rather than wandering as required for a Jain monk. Th ...

Gyanchandra. He said that he was "desirous of epitomising the chronicles of the martial races of Central and Western India" and that this necessitated study of their genealogy. The sources for this were ''Puranas'' held by the Rana

Rana may refer to:

Astronomy

* Rana (crater), a crater on Mars

* Delta Eridani or Rana, a star

People, groups and titles

* Rana (name), a given name and surname (including a list of people and characters with the name)

* Rana (title), a historica ...

of Udaipur

Udaipur () ( ISO 15919: ''Udayapura''), historically named as Udayapura, is a city and municipal corporation in Udaipur district of the state of Rajasthan, India. It is the administrative headquarter of Udaipur district. It is the historic ...

.

Tod also submitted archæological papers to the Royal Asiatic Society's ''Transactions'' series. He was interested in numismatics

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, medals and related objects.

Specialists, known as numismatists, are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, but the discipline also inc ...

as well, and he discovered the first specimens of Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, sou ...

n and Indo-Greek

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent ( ...

coins from the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

period following the conquests of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, which were described in his books. These ancient kingdoms had been largely forgotten or considered semi-legendary, but Tod's findings confirmed the long-term Greek presence in Afghanistan and Punjab. Similar coins have been found in large quantities since his death.The Gentleman's Magazine (February 1836), ''Obituary'', pp. 203–204.

In addition to these writings, he produced a paper on the politics of Western India that was appended to the report of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

committee on Indian affairs, 1833. He had also taken notes on his journey to Bombay and collated them for another book, ''Travels in Western India''. That book was published posthumously in 1839.

Reception

Criticism of the ''Annals'' came soon after publication. The anonymous author of the introduction to his posthumously published ''Travels'' states that

Further criticism followed. Tod was an officer of the British imperial system, at that time the world's dominant power. Working in India, he attracted the attention of local rulers who were keen to tell their own tales of defiance against the Mughal empire. He heard what they told him but knew little of what they omitted. He was a soldier writing about a caste renowned for its martial abilities, and he was aided in his writings by the very people whom he was documenting. He had been interested in Rajput history prior to coming into contact with them in an official capacity, as administrator of the region in which they lived. These factors, says Freitag, contribute to why the ''Annals'' were "manifestly biased".Freitag (2009), pp. 3–5. Freitag argues that critics of Tod's literary output can be split into two groups: those who concentrate on his errors of fact and those who concentrate on his failures of interpretation.

Tod relied heavily on existing Indian texts for his historical information and most of these are today considered unreliable. Crooke's introduction to Tod's 1920 edition of the ''Annals'' recorded that the old Indian texts recorded "the facts, not as they really occurred, but as the writer and his contemporaries supposed that they occurred." Crooke also says that Tod's "knowledge of ethnology was imperfect, and he was unable to reject the local chronicles of the Rajputs." More recently, Robin Donkin, a historian and geographer, has argued that, with one exception, "there are no native literary works with a developed sense of chronology, or indeed much sense of place, before the thirteenth century", and that researchers must rely on the accounts of travellers from outside the country.

Tod's work relating to the genealogy of the ''Chathis Rajkula'' was criticised as early as 1872, when an anonymous reviewer in the '' Calcutta Review'' said that Other examples of dubious interpretations made by Tod include his assertions regarding the ancestry of the Mohil Rajput clan when, even today, there is insufficient evidence to prove his point. He also mistook

Criticism of the ''Annals'' came soon after publication. The anonymous author of the introduction to his posthumously published ''Travels'' states that

Further criticism followed. Tod was an officer of the British imperial system, at that time the world's dominant power. Working in India, he attracted the attention of local rulers who were keen to tell their own tales of defiance against the Mughal empire. He heard what they told him but knew little of what they omitted. He was a soldier writing about a caste renowned for its martial abilities, and he was aided in his writings by the very people whom he was documenting. He had been interested in Rajput history prior to coming into contact with them in an official capacity, as administrator of the region in which they lived. These factors, says Freitag, contribute to why the ''Annals'' were "manifestly biased".Freitag (2009), pp. 3–5. Freitag argues that critics of Tod's literary output can be split into two groups: those who concentrate on his errors of fact and those who concentrate on his failures of interpretation.

Tod relied heavily on existing Indian texts for his historical information and most of these are today considered unreliable. Crooke's introduction to Tod's 1920 edition of the ''Annals'' recorded that the old Indian texts recorded "the facts, not as they really occurred, but as the writer and his contemporaries supposed that they occurred." Crooke also says that Tod's "knowledge of ethnology was imperfect, and he was unable to reject the local chronicles of the Rajputs." More recently, Robin Donkin, a historian and geographer, has argued that, with one exception, "there are no native literary works with a developed sense of chronology, or indeed much sense of place, before the thirteenth century", and that researchers must rely on the accounts of travellers from outside the country.

Tod's work relating to the genealogy of the ''Chathis Rajkula'' was criticised as early as 1872, when an anonymous reviewer in the '' Calcutta Review'' said that Other examples of dubious interpretations made by Tod include his assertions regarding the ancestry of the Mohil Rajput clan when, even today, there is insufficient evidence to prove his point. He also mistook Rana Kumbha

Kumbhakarna Singh (r. 1433–1468 CE), popularly known as Maharana Kumbha, was the Maharana of Mewar kingdom in India. He belonged to the Sisodia clan of Rajputs. Rana Kumbha is known for his illustrious military career against various sultana ...

, a ruler of Mewar in the fifteenth century, as being the husband of the princess-saint Mira Bai and misrepresented the story of the queen Padmini. The founder of the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexand ...

, Alexander Cunningham

Major General Sir Alexander Cunningham (23 January 1814 – 28 November 1893) was a British Army engineer with the Bengal Engineer Group who later took an interest in the history and archaeology of India. In 1861, he was appointed to the newl ...

, writing in 1885, noted that Tod had made "a whole bundle of mistakes" in relation to the dating of the Battle of Khanwa

The Battle of Khanwa was fought at Khanwa on March 16, 1527. It was fought between the invading Timurid forces of Babur and the Rajput confederacy led by Rana Sanga for suprermacy of Northern India. The battle was a major event in Medieval ...

, and Crooke notes in his introduction to the 1920 edition that Tod's "excursions into philology are the diversions of a clever man, not of a trained scholar, but interested in the subject as an amateur." Michael Meister

Michael Meister (born 9 June 1961) is a German mathematician and politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who has been serving as a member of the Bundestag from the state Hesse since 1994. From 2018 until 2021 he also served as Parli ...

, an architectural historian and professor of South Asia Studies, has commented that Tod had a "general reputation for inaccuracy ... among Indologists by late in the nineteenth century", although the opinion of those Indologists sometimes prevented them from appreciating some of the useful aspects in his work. That reputation persists, with one modern writer, V. S. Srivastava of Rajasthan's Department of Archaeology and Museums, commenting that his works "are erroneous and misleading at places and they are to be used with caution as a part of sober history".

In its time, Tod's work was influential even among officials of the government, although it was never formally recognised as authoritative. Andrea Major, who is a cultural and colonial historian, has commented on a specific example, that of the tradition of sati (ritual immolation of a widow):

The romantic nationalism that Tod espoused was used by Indian nationalist writers, especially those from the 1850s, as they sought to resist British control of the country. Works such as Jyotirindranath Tagore's ''Sarojini ba Chittor Akrama'' and Girishchandra Ghosh's ''Ananda Raho'' retold Tod's vision of the Rajputs in a manner to further their cause. Other works which drew their story from Tod's works include ''Padmini Upakhyan'' (1858) by Rangalal Banerjee and ''Krishna Kumari'' (1861) by Michael Madhusudan Dutt

Michael Madhusudan Dutt ((Bengali: মাইকেল মধুসূদন দত্ত); (25 January 1824 – 29 June 1873) was a Bengali poet and playwright. He is considered one of the pioneers of Bengali literature.

Early life

Dutt ...

.

In modern-day India, he is still revered by those whose ancestors he documented in good light. In 1997, the Maharana Mewar Charitable Foundation instituted an award named after Tod and intended it to be given to modern non-Indian writers who exemplified Tod's understanding of the area and its people. In other recognition of his work in Mewar Province, a village has been named ''Todgarh'', and it has been claimed that Tod was in fact a Rajput as an outcome of the process of karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively ...

and rebirth. Freitag describes the opinion of the Rajput people

Furthermore, Freitag points out that "the information age has also anointed Tod as the spokesman for Rajasthan, and the glories of India in general, as attested by the prominent quotations from him that appear in tourism related websites."

Works

Published works by James Tod include: * * * * * * * * * *Later editions

* * * The Royal Asiatic Society is preparing a new edition of the ''Annals'' in celebration of the Society's bicentenary in 2023. A team of scholars are producing the original text of the first edition, together with a new introduction and annotations, and also a companion work that "will provide critical interpretive apparatus and contextual frames to aid in reading this iconic text." Containing "additional visual and archival material from the Society’s collections and beyond", it is to be co-published by the Society andYale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Univers ...

in 2021.Charley (2018).

See also

* History of RajasthanReferences

Notes Citations Bibliography * * * (Subscription required). * * * * * * (Subscription required). * * * * * * * * * * (Subscription required). * * * * * (Subscription required). * * * * * * * * * * * (Subscription oUK public library membership

required). * * (Subscription required).

Further reading

* * * * * – A partial review of ''Travels'', concluded in the subsequent issue. * * – an example of a treaty in which Tod was involved. *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Tod, James 1782 births 1835 deaths British cartographers British East India Company Army officers British historians British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Maratha War British numismatists English people of Scottish descent Historians of India History of Rajasthan People from the London Borough of Islington British male writers