James Scullin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

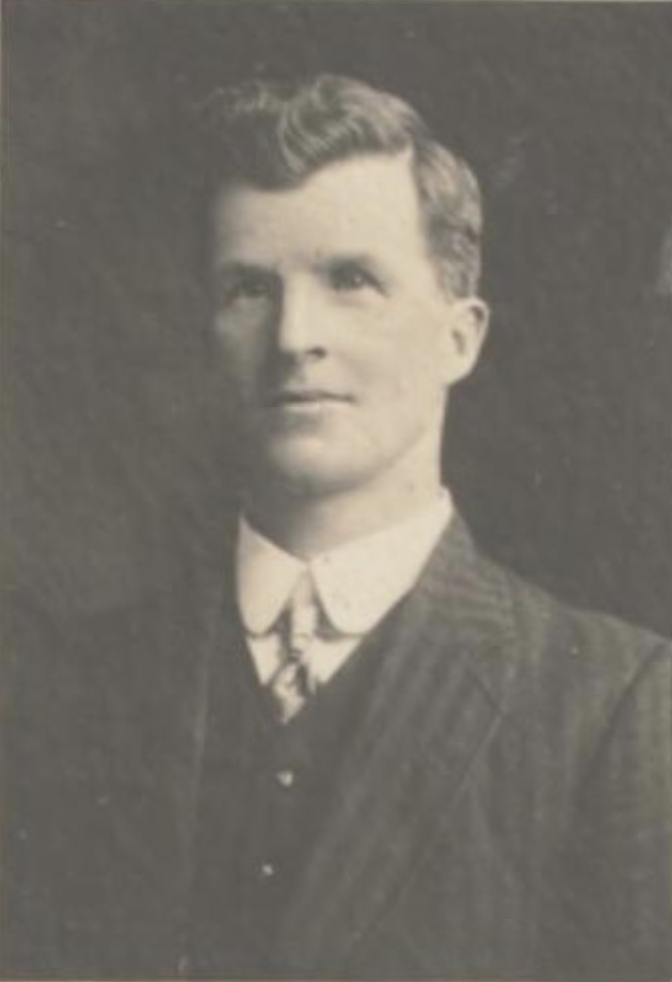

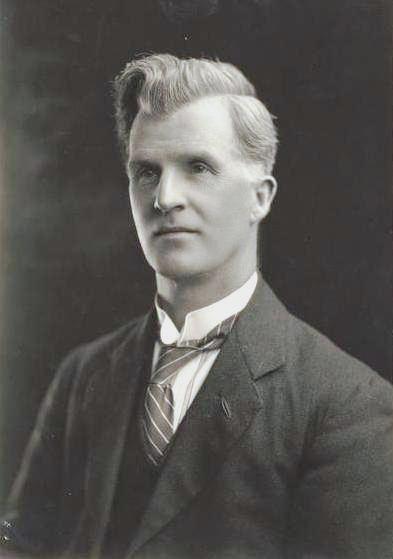

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 β 28 January 1953) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the ninth

Scullin was born in

Scullin was born in

In

In

The death of federal Labor leader Frank Tudor left a vacancy in the very safe urban seat of the Division of Yarra in

The death of federal Labor leader Frank Tudor left a vacancy in the very safe urban seat of the Division of Yarra in

As Deputy Leader, Scullin excelled in taking the case to the government. Throughout 1927 Scullin earned particular acclaim in keeping the ageing Bruce government to account on economic and financial matters. A series of speeches by Scullin that year on the Government's mishandling of the economy, and the generally dangerous trajectory of Commonwealth financial policy, predicted catastrophe. He accused the government of spending too much, borrowing too much from overseas sources, and not rectifying a worrying excess of imports over exports: a three-part recipe for disaster. This alarming analysis of the Australian economy would prove to be correct within three years, however relatively few paid attention to Scullin's warning at the time, nor the prescient 1927 volume ''The Boom of 1890 β And Now'' by E.O.G. Shann, on which Scullin based many of his arguments.

In March 1928, Matthew Charlton resigned as federal Labor leader and was replaced by Scullin in a unanimous motion, although some had their eye on newcomer

As Deputy Leader, Scullin excelled in taking the case to the government. Throughout 1927 Scullin earned particular acclaim in keeping the ageing Bruce government to account on economic and financial matters. A series of speeches by Scullin that year on the Government's mishandling of the economy, and the generally dangerous trajectory of Commonwealth financial policy, predicted catastrophe. He accused the government of spending too much, borrowing too much from overseas sources, and not rectifying a worrying excess of imports over exports: a three-part recipe for disaster. This alarming analysis of the Australian economy would prove to be correct within three years, however relatively few paid attention to Scullin's warning at the time, nor the prescient 1927 volume ''The Boom of 1890 β And Now'' by E.O.G. Shann, on which Scullin based many of his arguments.

In March 1928, Matthew Charlton resigned as federal Labor leader and was replaced by Scullin in a unanimous motion, although some had their eye on newcomer

Scullin came to Canberra amid rapturous applause from his supporters and the largest majority that Labor had ever won at the time. However, the party had many diverse interests and factions within it, ranging from metropolitan socialist radicals to rural professional politicians. The Scullin government immediately rolled back several of the Bruce government's measures deemed to be anti-labor β including changes made to industrial arbitration and competition, and the immediate abolition of

Scullin came to Canberra amid rapturous applause from his supporters and the largest majority that Labor had ever won at the time. However, the party had many diverse interests and factions within it, ranging from metropolitan socialist radicals to rural professional politicians. The Scullin government immediately rolled back several of the Bruce government's measures deemed to be anti-labor β including changes made to industrial arbitration and competition, and the immediate abolition of

Ongoing industrial disputes on the coalfields of the Hunter Valley and

Ongoing industrial disputes on the coalfields of the Hunter Valley and  Tarred with the political scandal, the budget, which raised taxes, cut spending and still did not deliver a surplus, was very unpopular with all sections of the community. What is more, the budget proved overly optimistic as Australian revenues continued to plunge and the deficit rose. By August 1930, crisis meetings were held in which Sir Robert Gibson and Sir Otto Niemeyer were demanding further economies in Commonwealth spending. Niemeyer, a representative of the Bank of England, had arrived in Australia to inspect financial conditions on behalf of creditors and had a grim report β that "Australian credit is at a low ebb...lower than that of any of the other dominions" and that without drastic steps default and financial collapse was assured. Gibson agreed, and as Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank Board had the power to deny the Australian government loans to finance the budget unless more cuts were made by both the national and state governments. After meeting with Scullin and state premiers, the 'Melbourne Agreement' was reluctantly struck in which further major spending cuts were agreed to, although opposed by a significant minority of Scullin's party.

In the heat of this crisis, matters were made worse still by Scullin's decision to travel to London on 25 August 1930 to seek an emergency loan and to attend the

Tarred with the political scandal, the budget, which raised taxes, cut spending and still did not deliver a surplus, was very unpopular with all sections of the community. What is more, the budget proved overly optimistic as Australian revenues continued to plunge and the deficit rose. By August 1930, crisis meetings were held in which Sir Robert Gibson and Sir Otto Niemeyer were demanding further economies in Commonwealth spending. Niemeyer, a representative of the Bank of England, had arrived in Australia to inspect financial conditions on behalf of creditors and had a grim report β that "Australian credit is at a low ebb...lower than that of any of the other dominions" and that without drastic steps default and financial collapse was assured. Gibson agreed, and as Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank Board had the power to deny the Australian government loans to finance the budget unless more cuts were made by both the national and state governments. After meeting with Scullin and state premiers, the 'Melbourne Agreement' was reluctantly struck in which further major spending cuts were agreed to, although opposed by a significant minority of Scullin's party.

In the heat of this crisis, matters were made worse still by Scullin's decision to travel to London on 25 August 1930 to seek an emergency loan and to attend the

Returning to Australia on 6 January 1931, Scullin was faced with a party now deeply divided over how to respond to the Depression. Jack Lang had won election as

Returning to Australia on 6 January 1931, Scullin was faced with a party now deeply divided over how to respond to the Depression. Jack Lang had won election as

Traumatic as it was, the government finally now was implementing an economic plan, and things began to improve. Domestic confidence, and confidence in the British loan market, began to recover and default was averted. Voluntary acceptance of lower bond rates on government debt had been extremely successful in a patriotic campaign, wool and wheat prices finally began to rise, and government finances at both Commonwealth and state level were largely under control by October. But with unemployment still rising (it would not peak until 1932), Scullin still faced disillusionment from many within his party, and further gains in ground by Lang. Lang felt threatened by the apparent success of the Premier's Plan though, and renewed talks of unity between the factions had appeared with the improvement of economic conditions. Lang Labor subsequently forced a showdown with the Scullin government in November. With allegations arising that Theodore had abused his position as treasurer to buy support in New South Wales away from the Lang faction, Beasley and his followers called for a

Traumatic as it was, the government finally now was implementing an economic plan, and things began to improve. Domestic confidence, and confidence in the British loan market, began to recover and default was averted. Voluntary acceptance of lower bond rates on government debt had been extremely successful in a patriotic campaign, wool and wheat prices finally began to rise, and government finances at both Commonwealth and state level were largely under control by October. But with unemployment still rising (it would not peak until 1932), Scullin still faced disillusionment from many within his party, and further gains in ground by Lang. Lang felt threatened by the apparent success of the Premier's Plan though, and renewed talks of unity between the factions had appeared with the improvement of economic conditions. Lang Labor subsequently forced a showdown with the Scullin government in November. With allegations arising that Theodore had abused his position as treasurer to buy support in New South Wales away from the Lang faction, Beasley and his followers called for a

The heavy task of leading the country through the brunt of the depression, beset as he was by many enemies and few friends, left deep marks on Scullin's character. As one Country Party parliamentarian observed, "the great burden that was imposed upon him then almost killed him". Scullin won much praise for his performance as Opposition Leader, as he had before coming prime minister. His grasp of economic and trade matters was still formidable, and on several matters he succeeded in forcing changes to government policy or banding with the Country Party to force amendments to government legislation. However failure to reunite the party and dislodge Lang as the alternative voice of the party failed in the lead-up to the 1934 election left the party at a distinct disadvantage. Ultimately, Scullin and his Commonwealth supporters' implementation of the

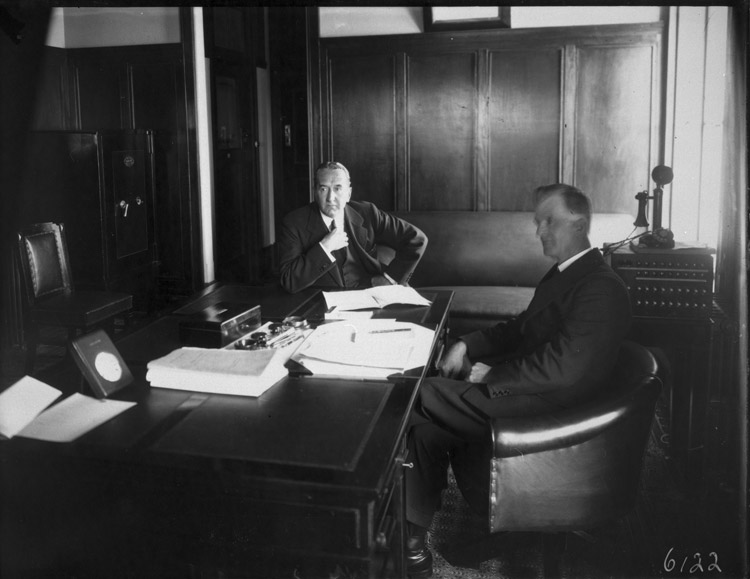

The heavy task of leading the country through the brunt of the depression, beset as he was by many enemies and few friends, left deep marks on Scullin's character. As one Country Party parliamentarian observed, "the great burden that was imposed upon him then almost killed him". Scullin won much praise for his performance as Opposition Leader, as he had before coming prime minister. His grasp of economic and trade matters was still formidable, and on several matters he succeeded in forcing changes to government policy or banding with the Country Party to force amendments to government legislation. However failure to reunite the party and dislodge Lang as the alternative voice of the party failed in the lead-up to the 1934 election left the party at a distinct disadvantage. Ultimately, Scullin and his Commonwealth supporters' implementation of the  Curtin became prime minister in 1941 after two independents joined Labor in voting down the government's budget. Curtin came to rely on Scullin greatly for his counsel. Scullin took no portfolio nor played any part in military strategy or much of the overall war effort, except where finance was concerned. However, he was given the office between Curtin and Treasurer

Curtin became prime minister in 1941 after two independents joined Labor in voting down the government's budget. Curtin came to rely on Scullin greatly for his counsel. Scullin took no portfolio nor played any part in military strategy or much of the overall war effort, except where finance was concerned. However, he was given the office between Curtin and Treasurer

Scullin had defended his record in government throughout his later career, and took pride in having been prime minister in times which might have broken a lesser figure. However he lived long enough to see many of his economic ideas vindicated by history, particularly inflationary financing, which was quite radical by the standards of his times but an accepted pillar of

Scullin had defended his record in government throughout his later career, and took pride in having been prime minister in times which might have broken a lesser figure. However he lived long enough to see many of his economic ideas vindicated by history, particularly inflationary financing, which was quite radical by the standards of his times but an accepted pillar of

in JSTOR

* Head, Brian. "Economic crisis and political legitimacy: the 1931 federal election." ''Journal of Australian Studies'' (1978) 2#3 pp: 14β29

online

* Richardson, Nick. "The 1931 Australian Federal Election β Radio Makes History." ''Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television'' (2010) 30#3 pp: 377β389. * Roberts, Stephen H. "The Crisis in Australia: September, 1930βJanuary, 1932." ''Pacific Affairs'' (1932) 5#4 pp: 319β332

in JSTOR

* Robinson, Geoff. "The Australian class structure and Australian politics 1931β40." APSA 2008: Australasian Political Science Association 2008 Conference. Australasian Political Science Association, 2008

online

* Robertson, J. R. "Scullin as Prime Minister: seven critical decisions." ''Labour History'' (1969): 27β36

in JSTOR

* Unpublished * Online * * * *

James Scullin

at the

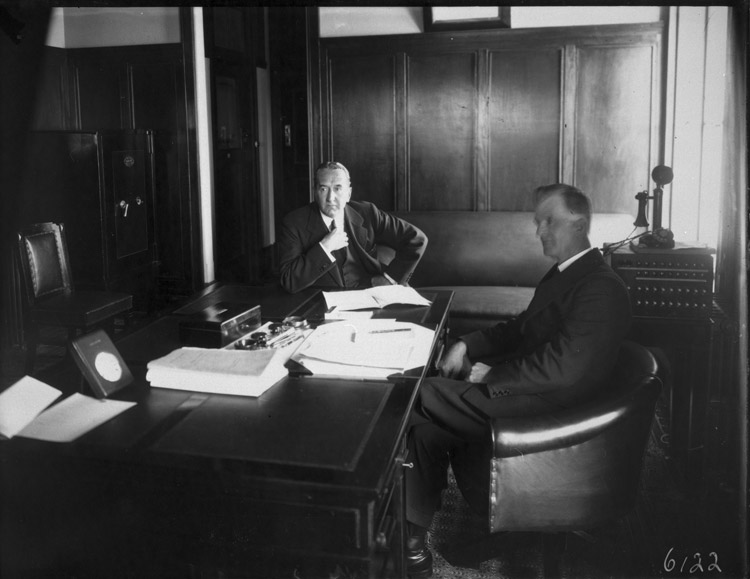

Photos of James Scullin

from the Mildenhall Collection at the National Archives of Australia.

James Scullin

at the

James Scullin Fact Sheet

at the

Scullin's Campaign Speeches of 1929

an

1931

at the Museum of Australian Democracy

Resources on James Scullin

by ''Trove'' at the

Essay on James Scullin as Treasurer

from the Australian Treasury. {{DEFAULTSORT:Scullin, James 1876 births 1953 deaths Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Leaders of the opposition (Australia) Ministers for foreign affairs of Australia Australian people of Irish descent Australian Roman Catholics Treasurers of Australia Members of the Cabinet of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Corangamite Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Yarra People from Ballarat Prime ministers of Australia 20th-century prime ministers of Australia Leaders of the Australian Labor Party Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Respiratory disease deaths in Victoria (state) Deaths from pulmonary edema Burials at Melbourne General Cemetery Australian MPs 1910β1913 Australian MPs 1922β1925 Australian MPs 1925β1928 Australian MPs 1928β1929 Australian MPs 1929β1931 Australian MPs 1931β1934 Australian MPs 1934β1937 Australian MPs 1937β1940 Australian MPs 1940β1943 Australian MPs 1943β1946 Australian MPs 1946β1949 Australian MPs 1919β1922

prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

from 1929 to 1932. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

(ALP), having briefly served as treasurer of Australia

The Treasurer of Australia, also known as the Federal Treasurer or more simply the Treasurer, is the Federal Executive Council (Australia), minister of state of the Australia, Commonwealth of Australia charged with overseeing government revenu ...

during his time in office from 1930 to 1931. His time in office was primarily categorised by the Wall Street crash of 1929 which transpired just two days after his swearing in, thus heralding the beginning of the Great Depression in Australia

Australia was affected badly during the period of the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Depression began with the Wall Street crash of 1929 and rapidly spread worldwide. As in other nations, Australia had years of high unemployment, poverty, ...

. Scullin remained a leading figure in the Labor movement throughout his lifetime, and was an '' Γ©minence grise'' in various capacities for the party until his retirement from federal parliament in 1949. He was the first Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

to serve as prime minister.

The son of working-class Irish-immigrants, Scullin spent much of his early life as a laborer and grocer in Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

. An autodidact

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning, self-study and self-teaching) is the practice of education without the guidance of schoolmasters (i.e., teachers, professors, institutions).

Overview

Autodi ...

and passionate debater, Scullin made the most of Ballarat's facilities β the public library and South Street Debating Society. He joined the Australian Labor Party in 1903, beginning a career spanning five decades. He was a political organizer and newspaper editor for the party, and was elected to the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Australian Senate, Senate. Its composition and powers are set out in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

...

first in 1910 and then again in 1922 until 1949. Scullin quickly established himself as a leading voice in parliament, rapidly rising to become deputy leader of the party in 1927 and then Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

in 1928.

After Scullin won a landslide election in 1929, events took a dramatic change with the crisis on Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

and the rapid onset of the Great Depression around the world, which hit heavily indebted Australia hard. Scullin and his Treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

Ted Theodore

Edward Granville Theodore (29 December 1884 β 9 February 1950) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1919 to 1925, as leader of the Australian Labor Party (Queensland Branch), state Labor Party. He later entere ...

responded by developing several plans during 1930 and 1931 to repay foreign debt, provide relief to farmers and create economic stimulus to curb unemployment based on deficit spending

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit, the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budg ...

and expansionary monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to affect monetary and other financial conditions to accomplish broader objectives like high employment and price stability (normally interpreted as a low and stable ra ...

. Although the Keynesian Revolution would see these ideas adopted by most Western nations by the end of the decade, in 1931 such ideas were considered radical and the plans were bitterly opposed by many who feared hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real versus nominal value (economics), real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimiz ...

and economic ruin. The still opposition-dominated Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives.

The powers, role and composition of the Senate are set out in Chap ...

, and the conservative-dominated boards of the Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), also known as Commonwealth Bank or simply CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of fi ...

and Loan Council, repeatedly blocked the plans.

With the prospect of bankruptcy facing the government, Scullin backed down and instead advanced the Premiers' Plan

The Premiers' Plan was a deflationary economic policy agreed by a meeting of the Premiers of the Australian states in June 1931 to combat the Great Depression in Australia that sparked the 1931 Labor split.

Background

The Great Depress ...

, a far more conservative measure that met the crisis with severe cutbacks in government spending. Pensioners and other core Labor constituencies were severely affected by the cuts, leading to a widespread revolt and multiple defections in parliament. After several months of infighting the government collapsed, and was resoundingly defeated by the newly formed United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four Elections in Australia, federal elections in that time, usually governing Coalition (Australia), in coalition ...

at the subsequent 1931 election.

Scullin would remain party leader for four more years, losing the 1934 election but the party split would not be healed until after Scullin's return to the backbench

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of t ...

es in 1935. Scullin became a respected elder voice within the party and leading authority on taxation and government finance, and would eventually play a significant role in reforming both when Labor returned to government in 1941. Although disappointed with his own term of office, he nonetheless lived long enough to see many of his government's ideas implemented by subsequent governments before his death in 1953.

Early life

Scullin was born in

Scullin was born in Trawalla, Victoria

Trawalla is a town in central Western Victoria, Australia, Victoria, Australia, located on the Western Highway, Victoria, Western Highway, west of Ballarat, Victoria, Ballarat and west of Melbourne, in the Shire of Pyrenees. At the , Trawalla a ...

on 18 September 1876. His parents, John and Ann (nΓ©e Logan) Scullin, were both Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

s from County Londonderry

County Londonderry (Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry (), is one of the six Counties of Northern Ireland, counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty-two Counties of Ireland, count ...

. His father was a railway labourer, who emigrated to Australia in his 20s. His mother joined her husband in Australia later. James was the fourth of eight children, and grew up in a tight-knit and devoutly Catholic home. James attended the Trawalla State School from 1881 to 1887 and earned an early reputation as an active and quick-witted boy, though never physically robust. These characteristics would remain with him for life.

The family moved to Mount Rowan, Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

, in 1887, and the young James attended school at Mount Rowan State School until 12. Thereafter he held various manual odd-jobs in the Ballarat district until about 1900, and for ten years from 1900 he ran a grocer's shop in Ballarat. In his mid-20s he attended night school, was a voracious reader and became somewhat of an autodidact

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning, self-study and self-teaching) is the practice of education without the guidance of schoolmasters (i.e., teachers, professors, institutions).

Overview

Autodi ...

. He joined a number of societies and was active in the Australian Natives' Association

The Australian Natives' Association (ANA) was a mutual society founded in Melbourne, Australia in April 1871. It was founded by and for the benefit of White native-born Australians, and membership was restricted to that group.

The Association's ...

and the Catholic Young Men's Society, eventually becoming president of the latter. He was also a skilled debater, participating in local competitions and having an association with the Ballarat South Street debating society for nearly 30 years, which would prove formative to his interest and talent in politics. Scullin was a devout Roman Catholic, a non-drinker and a non-smoker all his life.

Scullin became active in politics during his years in Ballarat, being influenced by the ideas of Tom Mann and the growing labour movement in Victoria, as were many of his later ministerial colleagues such as Frank Anstey, John Curtin and Frank Brennan. He became a foundation member of his local Political Labor Council in 1903 and was active in local politics thereafter. He was a campaigner and political organizer for the Australian Workers' Union

The Australian Workers' Union (AWU) is one of Australia's largest and oldest trade unions. It traces its origins to unions founded in the pastoralism, pastoral and mining industries in the late 1880s and it currently has approximately 80,000 ...

, the union movement with which he would remain most closely associated throughout his career. He spoke often around Ballarat on political issues and helped with Labor campaigns at state and federal level. At the 1906 federal election he was selected as the Labor candidate for the Division of Ballaarat against then Prime Minister Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 β 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1903 to 1904, 1905 to 1908, and 1909 to 1910. He held office as the leader of th ...

. Although a race in which Labor had virtually no chance of winning, Scullin ran a spirited campaign and impressed those within the movement for his efforts.

On 11 November 1907 he married Sarah Maria McNamara, a dressmaker from Ballarat. The marriage was childless. Due to Scullin's frequent and often serious bouts of illness over his long career, Sarah served the role as her husband's protector and was a crucial source of support and care for her husband, particularly in his final years. She was frequently called to assist or stand in for her husband at social occasions when her husband's illness prevented him from attending personally. She was an active member of the Labor Party herself, and would remain well-informed on politics. Very unusually among Australian political spouses (and even more so during the period of her husband's career), Sarah would often attend parliamentary sessions, and would even be present during the debate and vote that brought her husband's government down.

Political career

In

In 1910

Events

January

* January 6 β AbΓ© people in the French West Africa colony of CΓ΄te d'Ivoire rise against the colonial administration; the rebellion is brutally suppressed by the military.

* January 8 β By the Treaty of Punakha, t ...

Scullin won his first election as the Labor candidate in Corangamite, in a year when Labor's Andrew Fisher surged in the polls and formed Australia's first majority government. Scullin had done much to personally build the grass-roots organisation of the Labor movement in this seat in the years prior to the election, although its rural character meant it was not considered a seat naturally sympathetic to Labor. His campaign focused on increasing the powers of the Federal parliament and issues such as defending a white Australia, higher import duties and the introduction of a land tax. In federal parliament, Scullin quickly earned a reputation as an impressive and formidable parliamentary debater. He spoke on a wide range of issues over the three years of his term, but concentrated especially on matters relating to taxation and the powers of the Commonwealth, both of which would become signature issues for Scullin throughout his career. By the end of his first year in parliament he had a reputation as "one of the most ardent land-taxers in the Labor party" and had spoken frequently on breaking up "the land monopoly which has for so many years retarded the growth of this young country." Scullin enthusiastically supported Fisher's referendum questions in expand Commonwealth power over in 1911

Events January

* January 1 – A decade after federation, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory are added to the Commonwealth of Australia.

* January 3

** 1911 Kebin earthquake: An earthquake of 7.7 m ...

and again in 1913

Events January

* January – Joseph Stalin travels to Vienna to research his ''Marxism and the National Question''. This means that, during this month, Stalin, Hitler, Trotsky and Tito are all living in the city.

* January 3 &ndash ...

, though in both cases all amendment proposals were rejected by comfortable majorities. Although he was well regarded in his district and hard-working and ardent, it was not enough to shield him from Joseph Cook's resurgent and now united Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

in the election of 1913, and Scullin suffered the fate of many Labor members in rural districts at that year's election. He tried and failed to reacquire the seat at the 1918 Corangamite by-election.

After defeat Scullin was appointed as editor of the ''Evening Echo'', a daily newspaper owned by the Australian Workers Union in Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

. He would hold this position for the next nine years, which solidified his position within the Victorian Labor movement and made him an influential voice within its ranks, being elected president of the Victorian state branch of Labor in 1918. He and his paper became leading voices against conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

in Victoria during World War I, and a forceful intellectual contributor to the party during the Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 β 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics s ...

years. At the special Labor conference on conscription in 1916, Scullin moved for the expulsion of the conscriptionists, including Prime Minister Hughes and former prime minister Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia from April to August 1904. He held office as the inaugural federal leader of the Au ...

. During these years Scullin earned a reputation as a socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

on the left-wing of the party and had radicalised in some of his opinions, particularly his sentiments against imperial domination from London. Scullin was fiercely patriotic and critical of the war, particularly Britain's leadership of the dominions within it. In the early 1920s Scullin was prominent in the push for the party to adopt economic socialisation policies as part of its platform.

The death of federal Labor leader Frank Tudor left a vacancy in the very safe urban seat of the Division of Yarra in

The death of federal Labor leader Frank Tudor left a vacancy in the very safe urban seat of the Division of Yarra in Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

. Scullin handily won Labor preselection over several other candidates, and in February 1922 he took the seat at the ensuing 1922 Yarra by-election with more than three-quarters of the vote. With his win, he and his family relocated to Richmond, away from his long-time home of Ballarat, and to an electorate completely different in character to his earlier seat of Corangamite. However his new proximity to the Federal parliament (still located in Melbourne) and representation of a safe seat afforded many more political opportunities and freedoms, and soon Scullin was a prominent figure on the Labor campaign trail and appearing at events around the country. In these years Scullin's renown increased considerably within the party and the nation at large. He became one of the leading lights of the parliamentary opposition, and was quickly elevated to the Australian Labor Party National Executive

The Australian Labor Party National Executive, often referred to as the National Executive, is the executive governing body of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), charged with directly overseeing the general organisation and strategy of the party ...

in February 1923.

During his years as an opposition backbencher

In Westminster system, Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no Minister (government), governmental office and is not a Frontbencher, frontbench spokesperson ...

, Scullin spoke frequently and passionately. He was an able debater and parliamentary performer, but also carved out a niche as a leading voice on several issues, particularly taxation and economic policy. Some of Scullin's charges on land-tax avoidance by wealthy pastoralists

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anima ...

were so damning that the Bruce government called a Royal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

specifically to investigate his claims. Scullin's competence on financial matters proved useful to the government as well, and several of his suggestions from the opposition bench made their way into government legislation. In March 1927 Scullin became the parliamentary ALP's deputy leader.

Leader of the Opposition

As Deputy Leader, Scullin excelled in taking the case to the government. Throughout 1927 Scullin earned particular acclaim in keeping the ageing Bruce government to account on economic and financial matters. A series of speeches by Scullin that year on the Government's mishandling of the economy, and the generally dangerous trajectory of Commonwealth financial policy, predicted catastrophe. He accused the government of spending too much, borrowing too much from overseas sources, and not rectifying a worrying excess of imports over exports: a three-part recipe for disaster. This alarming analysis of the Australian economy would prove to be correct within three years, however relatively few paid attention to Scullin's warning at the time, nor the prescient 1927 volume ''The Boom of 1890 β And Now'' by E.O.G. Shann, on which Scullin based many of his arguments.

In March 1928, Matthew Charlton resigned as federal Labor leader and was replaced by Scullin in a unanimous motion, although some had their eye on newcomer

As Deputy Leader, Scullin excelled in taking the case to the government. Throughout 1927 Scullin earned particular acclaim in keeping the ageing Bruce government to account on economic and financial matters. A series of speeches by Scullin that year on the Government's mishandling of the economy, and the generally dangerous trajectory of Commonwealth financial policy, predicted catastrophe. He accused the government of spending too much, borrowing too much from overseas sources, and not rectifying a worrying excess of imports over exports: a three-part recipe for disaster. This alarming analysis of the Australian economy would prove to be correct within three years, however relatively few paid attention to Scullin's warning at the time, nor the prescient 1927 volume ''The Boom of 1890 β And Now'' by E.O.G. Shann, on which Scullin based many of his arguments.

In March 1928, Matthew Charlton resigned as federal Labor leader and was replaced by Scullin in a unanimous motion, although some had their eye on newcomer Ted Theodore

Edward Granville Theodore (29 December 1884 β 9 February 1950) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1919 to 1925, as leader of the Australian Labor Party (Queensland Branch), state Labor Party. He later entere ...

as a more promising replacement. The ensuing contest over the position of Deputy Leader saw Theodore denied once again in a close vote, foreshadowing some of the future controversy he would stir up within the party under Scullin.

Scullin led Labor at the 1928 election. He visited widely around the country, and made especial focus on Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

, Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

and Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

β states where the Labor party's fortunes had greatly declined in previous years. Scullin was well received and made ground in these areas, as well as in rural districts to counteract the increasingly urban nature of Labor. Labor managed to take eight seats, significantly reducing the Coalition's previously large majority. This was due to a swing against the government rather than a swing towards Labor, but was still enough to put Labor within striking distance of winning the next election. Although Labor came up well short of forming government, the campaign was viewed as a success and Scullin's reputation remained intact as leader.

1929 was dogged by industrial disputes, the worst of which occurred within the waterfront, timber and coalmining sectors. The Bruce government struggled to manage these episodes β its proposal by referendum for greater Commonwealth industrial powers had been rejected in 1926. After months of deadlock and protests over decisions of the Federal Arbitration Court, Bruce reversed course entirely by proposing that the Commonwealth dismantle federal arbitration and hand industrial matters back entirely to the states. The proposal was a radical departure from one of the pillars of the so-called " Australian settlement", and several MPs, led by former PM Billy Hughes, ultimately voted against the government and forced Bruce to seek an additional mandate from the people, at the 1929 election. Crucially, it would be a House-only election as the 1925 Senate term had not expired. Just 9 months after the previous campaign, Australia was in campaign mode once more. Amidst a background of industrial strife and heavy handed government proposals to deal with it, Scullin, who preached conciliation and negotiation between the parties, seemed the moderate choice, despite the more radical stances otherwise held by Labor. Fighting on their home territory and in favour of what was a still popular status-quo in industrial relations law, Scullin and Labor romped home in the polls, winning 46 seats in the 75 seat chamber, the most they had ever won at the time. Labor even managed to oust Bruce in his own seat. The party was jubilant and Scullin enthusiastically accepted commission to become prime minister. He was to be Australia's first Catholic prime minister.

Prime minister

Scullin came to Canberra amid rapturous applause from his supporters and the largest majority that Labor had ever won at the time. However, the party had many diverse interests and factions within it, ranging from metropolitan socialist radicals to rural professional politicians. The Scullin government immediately rolled back several of the Bruce government's measures deemed to be anti-labor β including changes made to industrial arbitration and competition, and the immediate abolition of

Scullin came to Canberra amid rapturous applause from his supporters and the largest majority that Labor had ever won at the time. However, the party had many diverse interests and factions within it, ranging from metropolitan socialist radicals to rural professional politicians. The Scullin government immediately rolled back several of the Bruce government's measures deemed to be anti-labor β including changes made to industrial arbitration and competition, and the immediate abolition of compulsory military training

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

. Scullin also chose not to take residence in The Lodge, which had only been completed two years prior, citing its unnecessary extravagance and cost to the taxpayer. In 1929, the Scullin government established the Canberra University College.

But the government's attention would soon shift to the economy. On the very day Scullin arrived in Canberra after the 1929 election, The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuous ...

announced large losses on Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

. On 24 October, two days after Scullin's cabinet was sworn in, news of Black Thursday

Black Thursday is a term used to refer to typically negative, notable events that have occurred on a Thursday. It has been used in the following cases:

*6 February 1851 β devastating day of bushfires in Victoria, Australia

*21 June 1877 execut ...

reached Australia and the government. The effect these developments would have on the Australian economy were not yet known, as economic conditions were already agreed to be poor, but the portents of future disaster were there. Three of the last four Commonwealth budgets had been in substantial arrears funded by overseas borrowing, and the value of Australian debt had been steadily declining in foreign markets. Sluggish years for the agricultural and manufacturing sectors were compounding the problem, but the most worrying statistic was unemployment, which was just over 13% at the end of 1929. A further problem was the decline in Australian trade. Price for wool and wheat β Australia's two principal exports β had fallen by almost a third during 1929. With debts rising and the ability to repay diminishing, Australia was faced with a seriously troubled financial outlook when Scullin took office.

Scullin's government faced significant limitations on its power to implement its response to the economic crisis. There had been no half-Senate election in 1929, meaning that the Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

majority elected at the 1928 election was still in place. The conservative Senate proved hostile to much of Labor's economic program. Scullin also had to contend with a financial establishment in Australia (most notably Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), also known as Commonwealth Bank or simply CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of fi ...

Board chairman Sir Robert Gibson) and in the United Kingdom (such as Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

representative Sir Otto Niemeyer) that was firmly opposed to any deviation from orthodox economics in responding to the Great Depression. On the contrary, there was much disagreement with Scullin's parliamentary party as to how to respond to the crisis, and a great many were sympathetic to the then radical ideas of inflationary finance and other proto-Keynesian approaches. Furthermore, Scullin and his Treasurer Ted Theodore were vehemently opposed to suggestions from the Opposition and Commonwealth Bank to reduce the deficit by cutting Federal welfare emoluments. Thus began two-years of clashes between the government and its opponents, which would prove to be some of the most turbulent in Australian political history.

Crisis and deadlock

Ongoing industrial disputes on the coalfields of the Hunter Valley and

Ongoing industrial disputes on the coalfields of the Hunter Valley and Newcastle

Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England, United Kingdom

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England, United Kingdom

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area ...

dragged on throughout Scullin's government, the Commonwealth lacking the power to coerce a solution and numerous negotiations between owners and workers collapsed. As a Labor Prime Minister, expectations ran high that Scullin would force the mine owners to submit to worker demands. Scullin was sympathetic, but refused to go beyond negotiations and inducements to end the disputes. Many within the New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

Labor branch were infuriated and felt they had been betrayed, catalysing a beginning of a separation between the state branch (led by fiery demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

Jack Lang) and the federal party led by Scullin.

Heavily indebted and with conditions worsening, Scullin and Theodore took many novel steps in an attempt to turn the economy around. Appeals were made, both to the Australian public and on overseas markets, to bolster confidence and boost government bond subscriptions. A "Grow More Wheat" campaign was launched in 1930 to encourage farmers to plant a record crop and attempt to improve Australia's serious trade deficit, although ultimately Scullin was unsuccessful in convincing the Senate or the Commonwealth Bank to support this program through price guarantees. At the same time unemployment had hit a record high of 14.6% in the March quarter of 1930. Scullin's election promise of unemployment insurance was discussed in this period, but with dire predictions for government finance the promise was continually stalled. Scullin made major proposals to change the constitutional amendment process; expand Commonwealth powers over commerce, trade and industry; and to break apart the Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), also known as Commonwealth Bank or simply CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of fi ...

to separate out its reserve bank and trading bank functions. The Senate blocked them all, or made amendments which rendered them unrecognisable. A double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissolutio ...

was threatened, though for various reasons both practical and political, Scullin never took this step. In June 1930 the government suffered a heavy loss when Theodore was forced to resign after he was criticised by a Royal Commission enquiring into a scandal known as the Mungana affair, claims of corrupt deals dating back to Theodore's time as Premier of Queensland. Scullin took over the Treasury portfolio in the interim while Theodore went to Queensland to face charges, and was compelled to bring down the 1930 budget personally.

Tarred with the political scandal, the budget, which raised taxes, cut spending and still did not deliver a surplus, was very unpopular with all sections of the community. What is more, the budget proved overly optimistic as Australian revenues continued to plunge and the deficit rose. By August 1930, crisis meetings were held in which Sir Robert Gibson and Sir Otto Niemeyer were demanding further economies in Commonwealth spending. Niemeyer, a representative of the Bank of England, had arrived in Australia to inspect financial conditions on behalf of creditors and had a grim report β that "Australian credit is at a low ebb...lower than that of any of the other dominions" and that without drastic steps default and financial collapse was assured. Gibson agreed, and as Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank Board had the power to deny the Australian government loans to finance the budget unless more cuts were made by both the national and state governments. After meeting with Scullin and state premiers, the 'Melbourne Agreement' was reluctantly struck in which further major spending cuts were agreed to, although opposed by a significant minority of Scullin's party.

In the heat of this crisis, matters were made worse still by Scullin's decision to travel to London on 25 August 1930 to seek an emergency loan and to attend the

Tarred with the political scandal, the budget, which raised taxes, cut spending and still did not deliver a surplus, was very unpopular with all sections of the community. What is more, the budget proved overly optimistic as Australian revenues continued to plunge and the deficit rose. By August 1930, crisis meetings were held in which Sir Robert Gibson and Sir Otto Niemeyer were demanding further economies in Commonwealth spending. Niemeyer, a representative of the Bank of England, had arrived in Australia to inspect financial conditions on behalf of creditors and had a grim report β that "Australian credit is at a low ebb...lower than that of any of the other dominions" and that without drastic steps default and financial collapse was assured. Gibson agreed, and as Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank Board had the power to deny the Australian government loans to finance the budget unless more cuts were made by both the national and state governments. After meeting with Scullin and state premiers, the 'Melbourne Agreement' was reluctantly struck in which further major spending cuts were agreed to, although opposed by a significant minority of Scullin's party.

In the heat of this crisis, matters were made worse still by Scullin's decision to travel to London on 25 August 1930 to seek an emergency loan and to attend the Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

. While in London, Scullin succeeded in gaining loans for Australia at reduced interest. He also succeeded in having King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 β 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

appoint Sir Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs, (6 August 1855 β 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of Au ...

as the first Australian-born Governor-General of Australia, despite the King's personal opposition and the strong objections of both the British establishment and the conservative opposition in Australia, who attacked the appointment as tantamount to republicanism. However a leadership vacuum was left behind, with Scullin out of the country for the whole second half of 1930, James Fenton (as acting prime minister) and Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 β 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Australia, from 1932 until his death in 1939. He held office as the inaugural leader of the United Australia Par ...

(as acting Treasurer) were left in charge. They insisted on pursuing deflationary policies and orthodox solutions to degrading Commonwealth budgetary position, arousing great opposition in the Labor caucus. In regular contact with Fenton and Lyons in London through the awkward means of cables, Scullin felt he had no choice but to agree to the recommendations of economic advisers, supported by Lyons and Fenton, that government spending be heavily cut, despite the suffering this caused and the disillusionment of the Labor party's base, whom were most affected by these cuts. Party unity began to crumble, and the gulf between the moderate and radical wings of the party began to grow.

Internal divisions and the Theodore Plan

Returning to Australia on 6 January 1931, Scullin was faced with a party now deeply divided over how to respond to the Depression. Jack Lang had won election as

Returning to Australia on 6 January 1931, Scullin was faced with a party now deeply divided over how to respond to the Depression. Jack Lang had won election as Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster system, Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales actin ...

and had become a leading alternative voice within Labor, advocating radical measures including repudiation of interest on debts to Britain and printing money to pay for public works programs to relieve unemployment and inflate the currency. The NSW contingent in Federal parliament was sympathetic to Lang's views and had become disillusioned with Scullin's leadership and his compromises with conservative interests. At the first meeting of cabinet upon his return, Scullin made things worse by reappointing Theodore as treasurer, despite his name not having been yet cleared over the Mungana Affair. Although arguably Theodore was the most competent man available to implement Scullin's economic program, Lyons and Fenton (as well as several others) were strongly opposed and resigned from the cabinet in protest. Making matters worse, Theodore had become a fierce personal rival of Lang within the New South Wales branch, and his return as treasurer further isolated radical elements of the party. At the same time, the economy had continued to decline and unemployment had soared, with most of the government measures designed to combat the crisis still in limbo due to opposition either from the Senate or refusal of funding by the Commonwealth Bank.

In February Scullin and Theodore presented a comprehensive plan at a conference of the state premiers that attempted to straddle both orthodox and radical approaches. While maintaining heavy budgetary cuts, it also planned to provide economic stimulus to help the unemployed and farmers, as well as repaying short-term debts and overdrafts held by British banks. This would require substantial further funds to be advanced by the Commonwealth Bank, however Gibson soon made it clear he would not do so unless significant cuts to social spending (particularly pensions) was also implemented. Scullin refused, instead planning to pay for the plan through the expanding the note issue. This 'Theodore Plan' was approved by narrow majorities of the state premiers and then the parliamentary party. However, Jack Lang rejected the plan, stating instead that Australia should default on its British debts until more equitable repayment terms were agreed to. Lyons and the conservatives within the party were horrified, as were the Opposition, seeing note issue as a sure path to hyperinflation and complete economic ruin.

In March matters came to a head. The 1931 East Sydney by-election saw Eddie Ward elected on a specifically pro-Lang platform, and the bitter campaign within the seat saw federal Labor and NSW Labor mutually expel each other from the party. Scullin and the Federal party refused to admit Ward to the caucus, and subsequently Jack Beasley led five others out of the party room to sit on the cross-benches as "Lang Labor". With chaos in Labor ranks and parliament facing a highly controversial plan for economic rehabilitation, the Opposition presented a motion of no confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fi ...

. Lyons, Fenton and four others on the conservative wing resigned from Labor and crossed over to the opposition benches. Scullin was reduced to a minority government of just 35 members, depending on the Lang faction to stay in power. Having built a large and popular following among the public, Lyons and his ex-Labor followers joined the Nationalists and the erstwhile followers of Hughes in United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four Elections in Australia, federal elections in that time, usually governing Coalition (Australia), in coalition ...

, with Lyons becoming the new Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

. With a possible default by the Commonwealth looming in June, Scullin's minority government attempted to push through the Theodore Plan. Although under pressure given the prospect of bankruptcy, the Senate and Gibson did not relent, and nearly all the bills needed to implement the Theodore Plan were rejected. Nationwide opinion was divided on the government plan, however many were extremely concerned about the prospect of excessive inflation should the government start printing money to pay its bills.

Premiers' Plan and downfall

Now May, with unemployment at 27.6% widespread suffering across much of the population, Scullin called another conference of the state premiers to try and forge a new deal, now resigned to the fact that compromise with the Opposition was inevitable if any plan could be implemented. A new orthodox plan calling for 20% reductions in spending across the board for all governments was struck, and such cuts to also apply to social welfare spending. Combined with a mass loan conversion that would reduce the interest rates paid ongovernment bond

A government bond or sovereign bond is a form of Bond (finance), bond issued by a government to support government spending, public spending. It generally includes a commitment to pay periodic interest, called Coupon (finance), coupon payments' ...

s by 22.5%, Australia now had a consensus as to how to reduce the annual deficit from some Β£41.08m to Β£14.65m. Although he had finally secured parliamentary and state approval for a plan, Scullin now faced a revolt from his own party. Cuts to pensions and the poor were particularly hard for Scullin, and many core Labor supporters felt deeply betrayed by this compromise of society's most vulnerable groups. Scullin ardently defend the program, but Lang's influence as an alternative opinion leader of Labor was growing, now with state branches in Victoria and South Australia rebelling against the Premiers' Plan

The Premiers' Plan was a deflationary economic policy agreed by a meeting of the Premiers of the Australian states in June 1931 to combat the Great Depression in Australia that sparked the 1931 Labor split.

Background

The Great Depress ...

.

Traumatic as it was, the government finally now was implementing an economic plan, and things began to improve. Domestic confidence, and confidence in the British loan market, began to recover and default was averted. Voluntary acceptance of lower bond rates on government debt had been extremely successful in a patriotic campaign, wool and wheat prices finally began to rise, and government finances at both Commonwealth and state level were largely under control by October. But with unemployment still rising (it would not peak until 1932), Scullin still faced disillusionment from many within his party, and further gains in ground by Lang. Lang felt threatened by the apparent success of the Premier's Plan though, and renewed talks of unity between the factions had appeared with the improvement of economic conditions. Lang Labor subsequently forced a showdown with the Scullin government in November. With allegations arising that Theodore had abused his position as treasurer to buy support in New South Wales away from the Lang faction, Beasley and his followers called for a

Traumatic as it was, the government finally now was implementing an economic plan, and things began to improve. Domestic confidence, and confidence in the British loan market, began to recover and default was averted. Voluntary acceptance of lower bond rates on government debt had been extremely successful in a patriotic campaign, wool and wheat prices finally began to rise, and government finances at both Commonwealth and state level were largely under control by October. But with unemployment still rising (it would not peak until 1932), Scullin still faced disillusionment from many within his party, and further gains in ground by Lang. Lang felt threatened by the apparent success of the Premier's Plan though, and renewed talks of unity between the factions had appeared with the improvement of economic conditions. Lang Labor subsequently forced a showdown with the Scullin government in November. With allegations arising that Theodore had abused his position as treasurer to buy support in New South Wales away from the Lang faction, Beasley and his followers called for a royal commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

into the charges. Scullin refused. To the surprise of many observers, the Beasley group crossed the floor to join the Opposition, thereby defeating the government. A snap poll, the 1931 election, was called. Scullin for the first time in Australian politics made heavy use of the radio to reach voters. The campaign was one of the shortest in history, but with open warfare between pro-Lang and pro-Scullin forces in Victoria and New South Wales, and much of the country still facing hardship and grievances against the government, a Labor defeat was virtually assured. Labor was defeated in a massive landslide. The official Labor Party was reduced to a mere 14 seats (Lang Labor won another 4), and Lyons became prime minister. However, Scullin was not held responsible for the debacle and stayed on as Labor leader. To date, it is the last time that a sitting Australian government has been defeated after a single term.

Later career

The heavy task of leading the country through the brunt of the depression, beset as he was by many enemies and few friends, left deep marks on Scullin's character. As one Country Party parliamentarian observed, "the great burden that was imposed upon him then almost killed him". Scullin won much praise for his performance as Opposition Leader, as he had before coming prime minister. His grasp of economic and trade matters was still formidable, and on several matters he succeeded in forcing changes to government policy or banding with the Country Party to force amendments to government legislation. However failure to reunite the party and dislodge Lang as the alternative voice of the party failed in the lead-up to the 1934 election left the party at a distinct disadvantage. Ultimately, Scullin and his Commonwealth supporters' implementation of the

The heavy task of leading the country through the brunt of the depression, beset as he was by many enemies and few friends, left deep marks on Scullin's character. As one Country Party parliamentarian observed, "the great burden that was imposed upon him then almost killed him". Scullin won much praise for his performance as Opposition Leader, as he had before coming prime minister. His grasp of economic and trade matters was still formidable, and on several matters he succeeded in forcing changes to government policy or banding with the Country Party to force amendments to government legislation. However failure to reunite the party and dislodge Lang as the alternative voice of the party failed in the lead-up to the 1934 election left the party at a distinct disadvantage. Ultimately, Scullin and his Commonwealth supporters' implementation of the Premiers' Plan

The Premiers' Plan was a deflationary economic policy agreed by a meeting of the Premiers of the Australian states in June 1931 to combat the Great Depression in Australia that sparked the 1931 Labor split.

Background

The Great Depress ...

was too much of a betrayal for many to accept, and opposing Lang and Scullin Labor factions continued to plague NSW and Victorian state politics for years. The election proved to be a dispiriting defeat for Scullin. Despite an admirable and vigorous term as opposition leader, Scullin's Labor gained just four seats and actually suffered a small swing against it, with Labor and the UAP losing ground to Lang Labor, which gained 5 seats on a swing of almost 4%.

Scullin markedly declined in vigor for his role as Opposition Leader after he was reconfirmed in it after the 1934 election. Tired of the infighting, he took little part in the renewed conciliation talks between the opposition party wings, which in the event failed to resolve the now entrenched divide between Lang and anti-Lang forces. Scullin at many points had stated his resolve to remain leader until such time that he could be sure he would not be succeeded by Lang forces at the federal level, but fate intervened and Scullin's health, always middling, declined significantly in 1935. Bedridden several times, Scullin tendered his resignation on 23 September 1935, citing a physical inability to continue as leader. By the time of Scullin's resignation Australia's economy had recovered significantly and business confidence had returned to a large extent. The belligerent actions of Japan in China, and then Germany in Europe, began to overtake the economy as the predominant concern of Australian politics. James Scullin was succeeded by John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 β 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), having been most ...

, who proved a necessary salve to Labor wounds. Under Curtin's leadership, most of the Lang Labor faction returned to the mainline Labor fold, though Lang and some supporters remained obdurate. During these years Scullin was far quieter in the backbenches, only occasionally taking an active role in parliament, though still an active local member in his seat of Yarra. He was a passionate advocate for Australian arts, and with the Fellowship of Australian Writers, was responsible for a dramatic boost to the Commonwealth Literary Fund

The Commonwealth Literary Fund (CLF) was an Australian Government initiative founded in 1908 to assist needy Australian writers and their families. It was Federal Australia's first systematic support for the arts. Its scope was later broadened to e ...

's budget in 1939.

Curtin became prime minister in 1941 after two independents joined Labor in voting down the government's budget. Curtin came to rely on Scullin greatly for his counsel. Scullin took no portfolio nor played any part in military strategy or much of the overall war effort, except where finance was concerned. However, he was given the office between Curtin and Treasurer

Curtin became prime minister in 1941 after two independents joined Labor in voting down the government's budget. Curtin came to rely on Scullin greatly for his counsel. Scullin took no portfolio nor played any part in military strategy or much of the overall war effort, except where finance was concerned. However, he was given the office between Curtin and Treasurer Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 β 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician and train driver who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), and was n ...

's, and his advice would have significant bearing upon the policy and political tactics of the Curtin government. Scullin was a leading voice in caucus in support of the new PM, urging it to give Curtin the powers to run his own government without the caucus interference Scullin himself had so frequently fallen afoul of a decade earlier. To Scullin's delight, rafts of social and economic policies, so long out of reach for Labor governments, finally became law during the wartime government. Scullin continued to be a leading voice in the movement in favour of further social welfare

Welfare may refer to:

Philosophy

*Well-being (happiness, prosperity, or flourishing) of a person or group

* Utility in utilitarianism

* Value in value theory

Economics

* Utility, a general term for individual well-being in economics and decision ...

plans and was influential within the party in the nature and direction these took. Another of Scullin's long held ambitions β eradication of the Federal structure in favour of a unified state β was advanced when he was appointed as one of three on a committee to recommend means of implementing uniform taxation. That committee soon proposed eliminating state governments' ability to levy income tax, a proposal which Curtin accepted and greatly weakened the Federal system by making states fiscally dependent on the Commonwealth. Scullin's committee work shone out again in 1944, where he led the charge to change the tax code to operate on a pay-as-you-go basis, which was accepted and implemented by the Curtin government.

Ill-health continued to return in bouts, but Scullin remained active if subdued in parliament after Curtin's death and Chifley's succession in 1945. He continued to be influential in fiscal and taxation matters, and the impact of his experience was still occasionally felt in Chifley-era legislation. However his health declined significantly in 1947, and he did not appear in parliament again after June of that year, announcing he would retire at the 1949 election.

Death and funeral

Scullin was frequently bedridden in these last 18 months, and unable to attend many gatherings. His condition deteriorated further after retirement, suffering cardio-renal failure

Kidney failure, also known as renal failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney fa ...

in 1951 and becoming almost permanently bedridden and under the care of his wife.

Scullin died in his sleep on 28 January 1953 in Hawthorn, Melbourne from complications arising from pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema (British English: oedema), also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive fluid accumulation in the tissue or air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. This leads to impaired gas exchange, most often leading to shortness ...

. He was accorded a state funeral in St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne with a Requiem Mass presided over by Archbishop Daniel Mannix. He was buried in the Catholic section of Melbourne General Cemetery

The Melbourne General Cemetery is a large (43 hectare) necropolis located north of the city of Melbourne in the suburb of Carlton North.

The cemetery is notably the resting place of five Prime Ministers of Australia, more than any other ...

. Over his grave the federal Labor executive and the ACTU

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), originally the Australasian Council of Trade Unions, is the largest peak body representing workers in Australia. It is a national trade union centre of 46 affiliated trade union, unions and eight t ...

erected a monument on behalf of the Labor movement of Australia. The inscription reads: "Justice and humanity demand interference whenever the weak are being crushed by the strong." Scullin's wife, Sarah

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch, prophet, and major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pious woma ...

, was interred with him in 1962. Labor stalwarts Arthur Calwell, Esmond Kiernan, Herbert Cremean and Edward Grayndler are all buried adjacent to the Scullin plot.

Legacy

Scullin had defended his record in government throughout his later career, and took pride in having been prime minister in times which might have broken a lesser figure. However he lived long enough to see many of his economic ideas vindicated by history, particularly inflationary financing, which was quite radical by the standards of his times but an accepted pillar of

Scullin had defended his record in government throughout his later career, and took pride in having been prime minister in times which might have broken a lesser figure. However he lived long enough to see many of his economic ideas vindicated by history, particularly inflationary financing, which was quite radical by the standards of his times but an accepted pillar of Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomics, macroeconomic theories and Economic model, models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongl ...

adopted by Australia and most other Western governments in the late 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 β 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

himself would state of Scullin's Premier's Plan which caused him so much woe and electoral unpopularity that it "saved the economic structure of Australia". ''The Economist'' admitted after the 1931 election that Scullin "had already done much to place Australia on the high road to recovery".